Professional Documents

Culture Documents

In Search of Intimate Streets

Uploaded by

Erwin Sukamto100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

104 views14 pagesJakarta is becoming the beacon of the whole of mankind. The problems of Jakarta are well engraved in its history that they have become a fateful persona of the city and of the citizens. In the new bus, air-conditioned passengers enjoy the tour along the 'front facade' of the city, where we can see the glitz and glam of malls.

Original Description:

Original Title

In search of intimate streets

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentJakarta is becoming the beacon of the whole of mankind. The problems of Jakarta are well engraved in its history that they have become a fateful persona of the city and of the citizens. In the new bus, air-conditioned passengers enjoy the tour along the 'front facade' of the city, where we can see the glitz and glam of malls.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

104 views14 pagesIn Search of Intimate Streets

Uploaded by

Erwin SukamtoJakarta is becoming the beacon of the whole of mankind. The problems of Jakarta are well engraved in its history that they have become a fateful persona of the city and of the citizens. In the new bus, air-conditioned passengers enjoy the tour along the 'front facade' of the city, where we can see the glitz and glam of malls.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 14

Comrades from Jakarta, let us build a Jakarta into the greatest city possible.

Great not just from a material

point of view; great, not just because of its skyscrapers; great not just because it has boulevards and beautiful

streets; great not just because it has beautiful monuments; great in every respect, even in the little houses of the

workers of Jakarta there must be a sense of greatness… Give Jakarta an extraordinary place in the minds of the

Indonesian people, because Jakarta belongs to the people of Jakarta. Jakarta belongs to the whole Indonesian

people. More than that, Jakarta is becoming the beacon of the whole of mankind. Yes, the beacon of the New

Emerging Forces.

-President Sukarno, Cited in Abeyasekere p.168

The voice of Indonesia’s first President, Soekarno, of walking. Through violent historical events and corruptive

slowly fades out, overwhelmed by honking cars and rumbling fundamentals, the city had been severely traumatized during its

engines. I kept walking on the elevated pedestrian way, sensing premature stage in the dawn of the nation’s independence and

the remnants of Soekarno’s ambition that have become vast, thus grew into a vast, dismal megalopolis stretched apart by

desolate spaces. A group of office workers got out of the bus, the horde of private cars. The problems of Jakarta are very well

and continued onto the platform. As they were heavily climbing engraved in her history that they have become a fateful persona

the stairs, their eyes looked tired, expressing dullness and of the city and of the citizens.

disappointment. At the background, an unfinished skyscraper I most vividly remember my experiences exploring

stood out, haunting the street view with its bare concrete the city out of curiosity, especially those when I took public

columns, recalling the past economic downfall. I looked down transport. Before Transjakarta Bus was popularized in

to the 10-lanes wide street below me. The streams of cars and 2004, getting around the major parts of the city would be an

motorbikes kept going and rushing, swallowing any other impossibly exhaustive experience. In the older vehicle, the lack

voices. The inhabitants, including myself, are awake from the of air-conditioning amplified the jumble of activities inside into

dream of a “greatest city possible”, only to face the ordeal of a nerve-wracking crowd. The “street parade” was happening

reality. inside the bus: a vendor offering peanuts and cigarettes; heat

The capital of Indonesia, Jakarta, has lured me into her and moist coming in and out of my lungs, often trying to

cataclysmic modernity. The idea of opening up opportunities of choke me; motorbikes honking their way through the traffic

sustainable utopia in Jakarta is discouraged upon witnessing jam outside precariously; street ‘musician’ shouting songs like

that the city is deemed as “a locus of crisis, a labyrinth in protests; and “bule”, the local term for foreign tourists, holding

which anyone who heroically attempts to alleviate a mess will on to an enormous backpack possibly containing one month

inevitably end up in a bigger one” (Agung Hujatnikajennong, supply of food, considering the city is a sublime, wild nature.

in Helmond p.11). A Jakartan could survive either on the But in the new bus, air-conditioned passengers enjoy the tour

possession of a private car or determination to bear the along the ‘front façade’ of the streets, where we can see the

scorching sun heat, the polluted air, the risk of being assaulted, glitz and glam of malls and bars, the somber and authoritative

and the seemingly infinite distance unreachable by means municipal buildings, and the limp and abandoned parts of the

old city. While it runs on its own lane, traffic free sometimes,

the bus pierces through the street scenes outside: hours

long traffic congestions of cars, taxis, trucks, minibuses, and

vendors and snarls of motorbikes weaving through the small

openings, creating physical chaos. The bus ride clearly briefs

the characters of Jakarta: its highly opulent and ephemeral

imitations of Western extravagance, and in contrast, the

stretch of barren areas behind walls and below highways where

dubious street-dwellers lurk. It was a much more animated

experience compared to taking a taxi or driving a car, where

shut car windows mutes the streets, deafening our ears,

pampering us with the luxury of privacy. The people who take

public transports are those obligated due to their low income

and the need to commute from rural areas or the city’s vicinity

to center. Those who can afford greater luxury won’t take the

chance and rely instead on private vehicles. This is still the case

even in the newer bus system that transports group of people

with the same low income, but cleaner and more orderly. While

they share the same street, there is a clear separation between

public and private vehicles, between the bus driver and the

chauffeur, between the chaos and the silence.

The sheer social imbalance between the high-class

society to lower class people is not only reflected in the two

separate transportation group, the privatized cars for the

rich, and motorbikes and minibuses for the poor, but also

illuminated in an inevitable cycle that empowers the social gap.

The more people use private cars, the worse the conditions of title, “The Year of Living Dangerously” by Christopher Koch,

the streets as traffic jams intervals increase. The built highways portray the tumult and violence during the oppression of the

to temporarily relieve the congestion destroy pedestrian New Order regime by injecting the image of fear of the streets

accessibilities and the value of the area, hindering people to to the viewers and readers. The space of the street as the

walk on the streets and encouraging dissident dwellings among locus of Sukarno’s revolution “has been turned into the site of

the barren infrastructure, under the highways and behind “disturbance”. It became a “dangerous” place, which, in the

the wall gates. The owners of private cars have taken “refuge name of national security, demanded constant anticipation

in vehicles” to protect themselves from the discomfort and from the government. With the end of populist politics,

danger of the streets outside. The city is transformed into a “big Sukarno’s revolutionary subject was decapitated and the street,

wild-animal reservations of Africa, where tourists are warned where they used to parade, was criminalized” (Kusno. p.104).

to leave their cars under no circumstances until they reach a Now, as the streets are no longer used for parades or leisure

lodge” (Jacobs, p. 46). In fact, most of my acquaintances have they need to become longer and wider to accommodate large

never taken a public transport even once after living in the city streams of traffic and to connect people and transport goods

for 18-20 years because there is a good amount of justifiable between gated suburbs, where wealthy community takes

reason that goes along with their contemplation. The image of shelter, without a sense of guilt since the streets had been

the streets as being dangerous, dirty, and unpleasant has been cursed with political violence. Smaller streets grow larger, and

embedded in the mind of most Jakartans like an inerasable big streets never transform to intimate streets.

trauma. Of course there are areas specifically designated for

During “the year of living dangerously”, a period of pedestrians. Ironically however, visitors must drive and park

time during the transition of power when Suharto took the their car on a nearby parking lot to reach these places. Within

leadership over Sukarno by eradicating the Communist Party the center of the city, most of the streets are not pedestrian

and any of his supporters in 1966, violent acts of massacre friendly. One time I tried to prove myself that the city’s streets

of over half a million Indonesians on the streets had greatly are not dangerous but I couldn’t. The scenes of the streets

affected on how Jakarta’s streets function and what activities kept alienating me, giving a sense that I don’t belong here or

can and cannot happen. A novel and a movie with the same that I’ve trespassed someone’s territory. One minute I was

walking in front of a glitzy mall complex, complete with signs

of clothing lines like Louis Vuitton, Salvatore Ferragamo, and

Debenhams, labeling the building like nametags. Due to past

events of terrorist bombing in public places such as this mall,

security guards were scattered along the entrances, checking

each person’s purse and bag with a metal detector. Another

minute, only a few steps from the dazzling mall, I arrived

at a slum dwelling complex. My surroundings were filthy. A

row of three-story slum houses was on my left side, and dark

black open sewage, bordered by rigid concrete wall was on my

right side. Behind the wall is a vast, green range, reserved for

playing golf. The stench of rotten garbage and wastewater was

haunting my nose. Some eyes were peering from the balcony

of the slum houses; dogs and chickens were scavenging the

trash pile. I continued walking for about three hours, among

gated neighborhood and highways, only to realize that none of

the streets were expecting pedestrians. I didn’t see any people

walking beside some street dwellers and street urchins, aimless

and desolated, lurking in the shadows, hoping that their

presence went unnoticed.

When I tried to ‘solve’ the problems of Jakarta, I

was discouraged and frustrated by the limitless issue that

permeates throughout the entire city. Just like the “city

dweller is frustrated when he cannot find human order in his

environment” (Maki p.29). I realized then that the problems

of Jakarta are also triggered by the need of escape from the

problems as quickly as possible. The businesses here welcome INTIMATE STREETS

any global prospective investors who are offered greater luxury

In one sense, Jakarta is a city that doesn’t function properly.

that costs much less compared to many other mega cities in

There are more separations and restricting political forces

the world. Globalization and foreign exchange become the

than linkages. These moments of separations alienate city-

powerhouse of the city’s development. There is a need to

dwellers and “when he sees only the results of mechanical and

transform the look of Jakarta by mending and patching certain

economic processes controlling the form and feel of his place,

areas, removing unwanted parts, like plastic surgery. New

he must feel estranged, and outside” (Maki p.29). When the

suburban developments thrived, and modern skyscrapers and

city’s streets cannot function to link different things together,

apartments were placed along the arterial roads, squashing

when walls and mega structures block the streets’ potentials,

any low income houses before them. However, what they

the city also stop operating to bring people together. After all,

(major developers) fail to observe is that “there is nothing less

the formal quality of a city is “the agglomerate of decisions (and

urbane, nothing less productive of cosmopolitan mixture, than

abnegations from decisions) in the past concerning the way in

raw renewal, which displaces, destroys, and replaces, in that

which things fit together, or are linked” (Maki p.29). The same

mechanistic order” (Maki p.34). The fear of the streets has

way that Jakarta’s streets become separators that encourage

propelled exclusive communities to isolate themselves from the

traffic jams, pollution, social discrepancy, political turmoil,

the streets by creating formal separations, and thus creating

and the fear of the streets, they could also become links that

disconnections in the city’s environment itself. A renowned

are adhesive. Any parts of the city could become a link, but the

poet, Goenawan Mohamad, also stated the capital’s cruelty:

streets, especially in Jakarta, are the main “glue of the city” that

“unite all the layers of activity and resulting physical form in

Jakarta does not seem to offer any meaningful sense of

connection; there is nothing that must be retained and the city” (Maki p.35).

must not be lost… The city is alienating and it cannot

In search of intimate streets, I enjoyed the experience

stand alone, it is neither controlled by the ‘Dutch-

style fortress’ nor by the spirit of the ancient Javanese walking along some of Jakarta’s alleys that develop into

‘Mataram Kingdom’, but by something else, something a line of market stalls and small restaurants. An alley in

stronger – the economic and political forces around it,

that made us all foreigners here. Glodok area in Jakarta for instance, although still displayed

a slum-like quality, was bustling with traders, children, and

(Cited in Kusno p.162)

possibly maids, who was told to buy ingredients for dinner. traditional Chinese lanterns above, acting as a visual roof. The

Glodok is known as the ‘Chinatown’ of Jakarta, yet overtime, location of the street and how it connects one spot to another

there seems to be a mix of business between the local native are integral factors to popularize the street. The same method

Indonesians and the local Chinese-Indonesians regardless of was encouraged in one of the streets in my hometown, but due

the past tension between the two groups. The need of variety to the location of the street in the old city neighborhood, the

and mutual trading in this area has slowly diminished racial street failed to revive itself over a stigma of the area being old

segregation, that wasn’t caused by differences in skin color and scummy.

or physical features, but political upheavals of the past and The Istiklal Avenue in Istanbul is a prime example of a

social contrasts. In this street, where people tend to look successful pedestrian street. Nearly three million visitors fill

inward and have the same average income, a community is the entire street in a single day over the course of weekends.

formed out of local needs. Most of the small streets in Jakarta Bars, restaurants, galleries, boutiques, cinemas, bookstores,

however, are filled with slums without proper light, water, music stores, night clubs, cafes, and hostels occupy not

and sanitation, especially in the city center. There is no clarity only both sides of the street but also every single alleys

between private and public spaces and everything just clutters branching out from Istiklal Avenue. Although the crowd seems

into a discomfort. There is no mix of activities nor mutual insurmountable, I felt constant safety walking among these

relationship between each person and the alleys don’t welcome unknown people. People perform music, watch independent

strangers. Trapped between tall skyscrapers and arterial roads, film projected on a large canvas, and dance with strangers.

the condition worsens overtime as they could only sulk and Certain times during the day, a parade marches through the

tuck away the slums deeper into the crevices. street to celebrate. In any other times, the pack of visitors,

Another example of an intimate street is the vibrant orderly bustling in different directions, transform the street

display of gluttony on Smith Street, Singapore. During the into a festival, as if they celebrate to the city itself. It happened

day, the street functions normally to allow cars and public that the street also connects two busy tram stations on

transports passing through. But at night, the street is closed both ends of the street, and two monuments: a historically

off by rows of seatings filled with hungry locals and tourists. important tower, and a politically important Monument of

Small shops and restaurants on both sides of the street are Independence. The street ends to a large city square, where

actively serving customers while illuminated by hanging bus stations, tram stations, streets and parks interact with each

other. Only when a street is linking different things and “once energy to retain the dwellers. Most of the dissident dwellings

a street is well equipped to handle strangers, once it had both a in Jakarta consist of “people with the least choice, forced by

good, effective demarcation between private and public spaces poverty or discrimination to overcrowd, who come into an

and has a basic supply of activity and eyes, the more strangers unpopular area” (Jacobs p.276). However, people who move to

the merrier.” (Jacobs p.40) an overcrowded area cannot expect to stay there for a long time

A similar example is the Dotonbori street in Osaka, and “those who overcome the economic necessity to overcrowd

which runs along the Dotonbori canal and between two get out, instead of improving their lot within the neighborhood.

bridges. As a principal tourist destination and main They are quickly replaced by others who currently have little

entertainment district, it also displays a festive quality. The economic choice” (p.276). Due to the obligation to move into

backstreets of Dotonbori are always cleaned and illuminated, the slum areas, people wouldn’t give up another day to stay in

and even though they are only about eight feet wide, the their crummy houses once they have the chance to get out. At

walking experience was pleasant and comfortable. All the the same time, when too many people move out of slums too

streets I’ve mentioned above have a strong bonding capability. fast, “they leave a community in a perpetually embryonic stage,

Some of them might be wider, and some of them narrower, or perpetually regressing to helpless infancy” (Jacobs p.277).

but they all link the surrounding environment and encourage This isn’t the case on Glodok streets as people could actually

mutual activities in the community. I imagined that the alleys stay within the area while their small businesses thrive.

in Jakarta’s slums could potentially transform into one of Jacobs also mentioned that “the foundation for unslumming

the interactive market streets, like Glodok, but instead they is a slum lively enough to be able to enjoy city public life and

become dark pits that isolate people. The alleys of Jakarta sidewalk safety” (p.279). It is clearly reflected on how the

don’t provide link within the environment. Strangers and streets in Glodok welcome visitors while the slum alleys reject.

public interventions become interrupting forces and the slum These ideas are very relatable to many cities in the world

dwellers, having seen as an outcast from the society, are further and opportunistic due to the logic of economy. The idea of

alienated by major streets and highways. liberating the slum dwellers from slums could be realized by

To comprehend how slums could possibly transform to preserving the shared reliance within the community and to

a street in Glodok, I took Jane Jacobs’ argument that there is imbue them with as much linkage as possible. Often times a

an ‘unslumming’ process that happens when there is enough link couldn’t happen naturally and there is a need to radically

change the form of Jakarta by redesigning the streets, the meets another arterial road and thus becoming physical link

facade, the accessibility, and, indirectly, the mentality of the that mediates the two roads. However, in order to encourage

inhabitants. pedestrian accessibility, the clearing wouldn’t allow cars or

any other vehicles to pass through. Not only that the new

HORIZONTAL LINK street connects two major roads, but on each end, a bus

The general form of contrast in Jakarta is a long arterial road station allows visitors to reach the place easily. Secondly,

where apartments, offices and malls are placed along the on both sides of the new pedestrian street, local businesses

street, creating an illusion of a modern metropolis. Behind would be encouraged to start and thus economically support

these buildings are sprawls of low-income housings; some are the area with new job opportunities. These businesses would

informal, connected by countless networks of alleyways and vary in price and functions. Small businesses like souvenirs,

in between spaces. The large arterial roads don’t reduce in electronics, household appliances, fabric, drink, food, etc.

size gradually, but simply cutting a network of small streets, would fulfill the necessity to maintain the crowd and customers

creating jalan tikus (rats streets) which drivers coined when during night and day, and thus preventing the area from

taking these small alleys as shortcuts if they’re trapped becoming dead, dull, and dubious when less shops are open.

in a traffic jam. There is a complete disjunction, literally The idea here is also to attract different kinds of customers

demarcated by perimeter walls between the vertical buildings and mutual relationships between each local stores. When a

and the horizontal slum dwellings. There is a formal separation dependency towards high-class customers started to occur,

and a social separation that limits accessibility. The office tower there is a tendency that the businesses would amplify the social

users could not care less about their filthy surroundings and gap and the place could potentially be akin to red light district.

the slum dwellers have nothing to do with the apartments next Every so often, the street would open up to a public square,

to them. where local facilities are located, such as schools, mosques,

First of all, there is a need to relieve the slums from administrations, and small fields for ceremonies and bazaars

the curtain of skyscrapers and high-rise buildings. By clearing to happen. Just like the olden days, goods are transported

a way through the building and the slums behind it, there manually by carts, while pedestrians and bikers voluntarily

is a porosity that finally reveals and links the slums to the share the same street.

arterial road. This clearing would ideally continue until it

VERTICAL LINK

(social link, jobs, flow of money, tree + mushroom, housing for

the poor, housing for the rich, )

CARS”Garage or station of rapid transit system as stop, is a

link between the highway (or train) and pedestrian movement”

(p.33) (includes bus station, car station)

ATTRITION OF CARS (explain traffic jams, and then how?)

SEQUENTIAL PATH (from bedroom, to work, to parks, to

shopping, back to bedroom)

DESIGNING DECAY (old and new buildings integrated, old

and new city integrated)

ANIMATED CITY (filled with movements, and grows and

dies over time)

“Small shops, stores and restaurants - mostly one or two

stories high - occasionally mingled with small factories,

make continuous linear development along with the streets

where street cars (artery) and bus system run. Attached small

residences behind commercial structures are occupied in

general by those who own the shops or who are in low income

groups. These areas are subject to becoming slum areas.”

(Maki p.60-61)

BIBILIOGRAPHY

Abeyasekere, Susan. 1987. Jakarta: A History. Singapore:

Oxford U P.

Cortes, Jose Miguel. Dissident Cartographies. Pap/Cdr ed.

New York: Seacex, 2008. Print.

Helmond, Arjan van and Stani Michiel. Jakarta Megalopolis:

Horizontal and Vertical Observations. Amsterdam: Valiz Publishing,

2007.

Jacobs, Jane. Death and Life of Great American Cities. New

York: Random House, 1961.

Knapp, Ronald G. Asia’s Old Dwellings: Tradition,

Resilience, and Change. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Kurokawa, Kisho. Metabolism in Architecture. Oxford:

Westview Press, 1977. Print.

Kusno, Abidin. Behind the Postcolonial: Architecture, urban

space and political culture. London: Routledge, 2000.

Maki, Fumihiko. Investigations in Collective Form. St. Louis:

Washington University, 1964.

You might also like

- JAKARTA - by by ANDRE VLTCHEK PDFDocument23 pagesJAKARTA - by by ANDRE VLTCHEK PDFRany FuadNo ratings yet

- Equality and the City: Urban Innovations for All CitizensFrom EverandEquality and the City: Urban Innovations for All CitizensNo ratings yet

- The Streets of Europe: The Sights, Sounds & Smells That Shaped Its Great CitiesFrom EverandThe Streets of Europe: The Sights, Sounds & Smells That Shaped Its Great CitiesNo ratings yet

- City EverywhereDocument27 pagesCity EverywheresheuthiNo ratings yet

- Pacific Automobilism: Adventure, Status and the Carnival of Mobility, 1970–2015From EverandPacific Automobilism: Adventure, Status and the Carnival of Mobility, 1970–2015No ratings yet

- Sidewalk EssayDocument5 pagesSidewalk EssayZerg ProtossNo ratings yet

- City Lights and Urban Delights: Exploring Metropolitan WondersFrom EverandCity Lights and Urban Delights: Exploring Metropolitan WondersNo ratings yet

- The Art of Aoto-Mobility, Vehicular Art and The Space of Resistance in CalcuttaDocument34 pagesThe Art of Aoto-Mobility, Vehicular Art and The Space of Resistance in CalcuttaLīga GoldbergaNo ratings yet

- City of Men: Masculinities and Everyday Morality on Public TransportFrom EverandCity of Men: Masculinities and Everyday Morality on Public TransportNo ratings yet

- The Walker: On Finding and Losing Yourself in the Modern CityFrom EverandThe Walker: On Finding and Losing Yourself in the Modern CityNo ratings yet

- HUM S5 - Class 3Document6 pagesHUM S5 - Class 3The rock newNo ratings yet

- A Result of Socialism: How Seventy Years of Socialism Has Ruined UkraineFrom EverandA Result of Socialism: How Seventy Years of Socialism Has Ruined UkraineNo ratings yet

- Imagining Urban Futures: Cities in Science Fiction and What We Might Learn from ThemFrom EverandImagining Urban Futures: Cities in Science Fiction and What We Might Learn from ThemNo ratings yet

- City Planning PrinciplesDocument53 pagesCity Planning PrinciplesAyşe Nur TürkerNo ratings yet

- The Blinded City: Ten Years In Inner-City JohannesburgFrom EverandThe Blinded City: Ten Years In Inner-City JohannesburgNo ratings yet

- The Voice of the Machines: An Introduction to the Twentieth CenturyFrom EverandThe Voice of the Machines: An Introduction to the Twentieth CenturyNo ratings yet

- A Country of Cities: A Manifesto for an Urban AmericaFrom EverandA Country of Cities: A Manifesto for an Urban AmericaRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (4)

- Lewis Mumford On SuburbsDocument2 pagesLewis Mumford On SuburbsasmireinfinityNo ratings yet

- The Interior Circuit: A Mexico City ChronicleFrom EverandThe Interior Circuit: A Mexico City ChronicleRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (4)

- Folklore of The Freeway - Eric AvilaDocument256 pagesFolklore of The Freeway - Eric AvilaJuno IantoNo ratings yet

- The road: An ethnography of (im)mobility, space, and cross-border infrastructures in the BalkansFrom EverandThe road: An ethnography of (im)mobility, space, and cross-border infrastructures in the BalkansNo ratings yet

- Creative Urbanity: An Italian Middle Class in the Shade of RevitalizationFrom EverandCreative Urbanity: An Italian Middle Class in the Shade of RevitalizationNo ratings yet

- Brooklyn Is: Southeast of the Island: Travel NotesFrom EverandBrooklyn Is: Southeast of the Island: Travel NotesRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (5)

- ECOTOPIA Julien ROUSSILLE 205Document3 pagesECOTOPIA Julien ROUSSILLE 205,hdNo ratings yet

- Cultures and Settlements. Advances in Art and Urban Futures, Volume 3From EverandCultures and Settlements. Advances in Art and Urban Futures, Volume 3No ratings yet

- Supreme City: How Jazz Age Manhattan Gave Birth to Modern AmericaFrom EverandSupreme City: How Jazz Age Manhattan Gave Birth to Modern AmericaRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- The Way of Coyote: Shared Journeys in the Urban WildsFrom EverandThe Way of Coyote: Shared Journeys in the Urban WildsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Evolution of Automobiles and Trolleybuses Throughout HistoryDocument3 pagesEvolution of Automobiles and Trolleybuses Throughout Historyolarte.tomas.kevinsaulNo ratings yet

- Download Subway John E Morris E Morris full chapter pdf scribdDocument67 pagesDownload Subway John E Morris E Morris full chapter pdf scribdsally.molina377100% (4)

- Suburban Urbanities: Suburbs and the Life of the High StreetFrom EverandSuburban Urbanities: Suburbs and the Life of the High StreetRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- ED LIII 43 271018 Do Railway Tracks Serve The Public GoodDocument1 pageED LIII 43 271018 Do Railway Tracks Serve The Public GoodRaghubalan DurairajuNo ratings yet

- The Architecture of Supervised Freedom: Public SpacesDocument5 pagesThe Architecture of Supervised Freedom: Public Spacesp_nisha14No ratings yet

- Manhattan's Grid: An Experiment in Urban DevelopmentDocument4 pagesManhattan's Grid: An Experiment in Urban DevelopmentLivia PleșcaNo ratings yet

- Visible and Invisible Cities of Sophronia and AtlantaDocument4 pagesVisible and Invisible Cities of Sophronia and AtlantaRichard DagenhartNo ratings yet

- Daniel S. Lev (Editor)_ Ruth T. McVey (Editor) - Making Indonesia-Cornell University Press (2018)Document206 pagesDaniel S. Lev (Editor)_ Ruth T. McVey (Editor) - Making Indonesia-Cornell University Press (2018)Aritonang Toba MuaraNo ratings yet

- Peace Corps Indonesia Welcome Book FY13Document73 pagesPeace Corps Indonesia Welcome Book FY13Accessible Journal Media: Peace Corps Documents100% (1)

- Listening Script PAG Buku Bahasa Inggris 1 Kelas XDocument20 pagesListening Script PAG Buku Bahasa Inggris 1 Kelas XVitalis TesNo ratings yet

- Uas Genap Sejarah Indonesia Kelas X (TKJ - TKR) SMK Muhammadiyah Watukumpul T.P 2019 - 2020 (1-64)Document44 pagesUas Genap Sejarah Indonesia Kelas X (TKJ - TKR) SMK Muhammadiyah Watukumpul T.P 2019 - 2020 (1-64)teguhNo ratings yet

- Buried Histories-0Document7 pagesBuried Histories-0Wahdini PurbaNo ratings yet

- UM B ING MA 2021 (Wajib)Document10 pagesUM B ING MA 2021 (Wajib)Sosial100% (1)

- (Institute of Social Studies, The Hague) Saskia Wieringa (Auth.) - Sexual Politics in Indonesia-Palgrave Macmillan UK (2002)Document409 pages(Institute of Social Studies, The Hague) Saskia Wieringa (Auth.) - Sexual Politics in Indonesia-Palgrave Macmillan UK (2002)boomboomboomasdf2342100% (1)

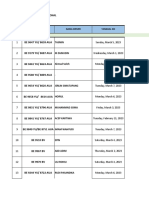

- Update Report GPS MPX99 Maret 2023Document107 pagesUpdate Report GPS MPX99 Maret 2023RezaNovandriNo ratings yet

- G30spki EnglishDocument15 pagesG30spki Englishai1510No ratings yet

- KD 3.4 Recount Text: A. Write The PAST FORM of The Following Verbs!Document2 pagesKD 3.4 Recount Text: A. Write The PAST FORM of The Following Verbs!ailinNo ratings yet

- Kartu Soal Usbn Bhs Inggris MGMP GowaDocument55 pagesKartu Soal Usbn Bhs Inggris MGMP Gowasahrul said75% (4)

- The Myth of Lazy Native PDFDocument23 pagesThe Myth of Lazy Native PDFShahAbbas1571No ratings yet

- RA Kartini's Impact as a Feminist PioneerDocument22 pagesRA Kartini's Impact as a Feminist PioneerSelfa YunitaNo ratings yet

- Saleskit Ibt JiexpoDocument12 pagesSaleskit Ibt JiexpoASkin Aesthetic ClinicNo ratings yet

- A C A Dake The Sukarno File 1965 1967 PDFDocument518 pagesA C A Dake The Sukarno File 1965 1967 PDFramzi100% (1)

- Rise of Nationalism in Southeast AsiaDocument2 pagesRise of Nationalism in Southeast AsiaHo LingNo ratings yet

- Indonesia - WikipediaDocument39 pagesIndonesia - WikipediaNashrllahNo ratings yet

- Ulangan Akhir SemesterDocument8 pagesUlangan Akhir SemesterAri WidiyantoNo ratings yet

- Biografi IrDocument2 pagesBiografi IrDua CahayaNo ratings yet

- Teks Recount Beserta StrukturnyaDocument2 pagesTeks Recount Beserta StrukturnyaEko ScholesNo ratings yet

- Index Indonesia 1Document35 pagesIndex Indonesia 1HafizZakariyaNo ratings yet

- Leadership of General SudirmanDocument12 pagesLeadership of General SudirmanAme FaizalNo ratings yet

- Indonesia - WikipediaDocument3 pagesIndonesia - WikipediaLai Yi QuanNo ratings yet

- Naskah Soal Sumatif Utama Bahasa Inggris 2023 KirimDocument14 pagesNaskah Soal Sumatif Utama Bahasa Inggris 2023 KirimSiti HoliaNo ratings yet

- Islamic SocialismDocument34 pagesIslamic Socialismikonoclast13456No ratings yet

- A Muslim ArchipelagoDocument296 pagesA Muslim ArchipelagoCorey Wayne Lande100% (2)

- Third Worldism and Global Fascism, Raj PatelDocument25 pagesThird Worldism and Global Fascism, Raj PatelkellycigmanNo ratings yet

- Preliminary Analysis of The October 1, 1965 Coup in IndonesiaDocument151 pagesPreliminary Analysis of The October 1, 1965 Coup in Indonesiafedi100% (2)

- Short TalkDocument3 pagesShort TalkGhalib IlhamNo ratings yet

- A Method To His MadnessDocument8 pagesA Method To His MadnessDrekorioNo ratings yet