Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Imaginary City - Leo Hollis - Medium

Uploaded by

ylanda illOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Imaginary City - Leo Hollis - Medium

Uploaded by

ylanda illCopyright:

Available Formats

Imaginary City

Leo Hollis Follow

Jul 19, 2016 · 9 min read

Urbanism does not need architecture. Nicholas Barbon. London.

Financialisation. Housing.

Or, as Dr Nicholas Barbon framed the argument in his ‘An Apology for

the Builder’, in 1685:

‘To write of Architecture and its several parts, of Situation, Platforms of

Building, and the quality of Materials, with their Dimensions and

Ornaments: To discourse of the several Orders of Columns, of the Tuscan,

Dorick, Ionick, Corinthian, and composit, with the proper inrichments of

their Capitals, Freete and Cornish, were to transcribe a Folio from

Vitruvius and others; and but mispend the Readers and Writers time.

Little has changed. In the current debate over the share of buildings

devised by architects, few are be bold enough to suggest that more than

10% of the city. As the American architectural theorist Keller Easterling

has pointed out, the cities of the future are more likely to be the result

of architectonic operating systems regurgitating replicable forms across

the urban plain, not individually designed dwellings in an organised

landscape.

‘It was not worth his while to deal little; that a bricklayer could do’, Barbon

claimed. How many of London’s city builders agree with him? Today

we live in Barbon’s city; when we look at the London skyline, why do

we continue to consider this scene the creation of staritects such as

Vinoly, Foster, Koolhaas and Rogers when the actual architects of the

city are Land Securities, Berkeley, large tech companies, universities,

government initiatives and enterprise zones founded on complicated

nancial instruments.

This is how the work of city-making is occurring — for better or worse.

The cult of the architect is a distraction, an parlour game played in

front of the top 1% of the 1%, while the real business of transforming

our urban environment goes on elsewhere.

But if you were to look for Dr. Barbon himself within the fabric of the

current city, you will nd little trace of him. The search will only turn

up a Barbon Alley, near Devonshire Square, and a Barbon Close by

Great Ormond’s Hospital. A couple of his houses can be found standing

on Bedford Row, but few of his original plans remain. The streetscape

that he developed on Essex Street, by the Temple, and Newburgh

Street, the main thoroughfare in Chinatown, follow the same lines

Barbon devised, but most of the houses themselves have been replaced.

Nonetheless, you see his legacy wherever you go in London. His

in uence seeps into DNA of the city, even if his name has been

forgotten.

Barbon was a child of the the civil war of the 1640s. He was born in

London, the son of a rebrand Baptist preacher, Praise-God Barbon,

who, in 1653, was one of Oliver Cromwell’s most puritanical

supporters at the head of a brief, Godly revolution that attempted to

establish a republic following the execution of Charles I. In the puritan

tradition, the young boy was given a horatory name, and the future

speculator was burdened with the moniker ‘If Jesus Had Not Died For

Thee Thou Wouldst Be Damned’ Barbon. When the Restoration came in

1660,and Charles II returned to England to reclaim the crown as the

republican experiments collapsed at the death of Cromwell, the father

was arrested as a traitor and the son escaped to Holland. When he

returned, having changed his name to ordinary Nicholas, it is

suggested that he may have been a doctor during the plague of 1665,

one of the few physicians who stayed to help the desperate of the city.

Yet it was not until after the Great Fire of 1666, that he turned his hand

to projectioning.

When he was at his pomp, the leading builder-speculator of 1680s

London, Barbon was described by the lawyer Roger North as living in

grandeur in the family Crane Court, rebuilt after the Great Fire. North

reports that Barbon would keep his creditors waiting in the drawing

room, then arrive, wrapped in brocade. Having bamboozled his guest,

he always found a way to rush them out of the house, unpaid, but with

promises of future fortunes. To aid this nancial chicanery, he kept an

o ce of ‘clerks, attorneys, scriveners and lawyers’ on hand to keep him

out of trouble. He operated beyond the reach of the legal courts,

keeping one step in front of the ‘police architectonic’, in particular the

Surveyor of the King’s Works Sir Christopher Wren, who History

records as the architect who made modern London.

So, in one instance, at Essex House by the Strand, a street that ran

along the north bank of the Thames between The City of London and

Westminster, Barbon was able to purchase the land against the King’s

wishes. Here stood a series of old aristocratic palaces that had fallen

out of fashion and was ripe for re-development. Without delay Barbon

knocked down the old buildings, and meanwhile silenced the

neighbours with o ers of new works. he skilfully neutralising the local

opposition by setting tenants against each other, e ecting a policy of

‘divide and rule’. After that, he set out and developed a whole new

street of ‘houses and tenements for taverns, alehouses, cookshoppes

and vaulting schools’, a garden and a wharf. He operated so swiftly that

when he was inevitably taken to court, he was able to complete the

whole scheme before the judge ruled that he had been in breach of the

agreement and ned. In a last gesture of chutzpah, Barbon passed the

court’s ne to the new owner of the lease and went on his way.

One can admire this rascally behaviour at three hundred years remove,

but it is not so amusing when it happens today. But perhaps we have

got this wrong. To criticise developers for searching for the shortest

route between investment and pro t is as ridiculous as punishing a dog

from sni ng another dog’s arse. It’s what they do; and they always

have. We are making a mistake by thinking that

Is there a di erence between how Barbon went about turning a pro t

at Essex House and how the latest Nine Elms development in Vauxhall,

currently emerging out of the ground in South London?. Initially the

developers estimated the value of the new Vauxhall Sky Garden, a new

development of 239 ats, at £612 per sq ft. The council’s assessors

suggested that this was too low by at least £10 per sq ft. Also there were

other sources of revenue for the developer that had not been added

into the gures. However, following talks it was agreed that only 17%

of the units should be reserved for a ordable rents.

Nevertheless, while negotiations were underway, the developer’s

agents started to sell o the units o -plan. The rst phase was

launched from the Four Seasons Hotel in Canary Wharf; there were

two further o ces opened in Hong Kong. The nal sum that all the

ats were sold for — £126 million — was £10 million than the original

estimates 10 months before. Nonetheless, in the end only 18 ats were

reserved for social housing: less than 13% of the total.

Barbon’s ‘Apology for the Builder’ was a plea to be left alone and

allowed to get onto it. The state should not get in the way of building

and pro t. Construction made the city safer and richer. By the 1680s,

however, there were few restrictions on what a builder could do. In

1685, the only planning laws that stood in the speculator’s way were

local parish conventions and the 1667 Rebuilding Act. This document,

the rst of its kind in history, set out the basis for what to build and

how, in the hope that the city never fall victim to re again.

For Barbon, this document o ered a template for his designs, yet he

exploited every loophole and gap he could nd in the regulations for

his own ends. The rebuilding e ort after the re changed everything:

what was built; how it was built, and where; who built it and who lived

there; how it was nanced. It was in these circumstances that the

developer as an urban player arrived in the scene.

The desperate need to rebuild after the re ripped up all standing

labour rules about working inside the City. Anyone who was willing,

not just those within the guilds, was enticed to come to London and

make a play for the exploding construction economy. There was a

fortune to be made out of the catastrophe. For a wily employer like

Barbon, however, it means that he could strip down practises and

regulations. Labourers were to be paid by the hour not the skill. This

reduce labour costs, but also encouraged new forms of production.

The new houses themselves were to be standardised, some of the main

parts put together in a workshop and then tted on site. The

appropriately called ‘carcass’ of the house was left bare for the new

owner, who bought the barebones of the house and then adapted to t

their own tastes. This become the mis en scene for bourgeois living, a

black canvas upon which the geegaws and accoutrements of tasteful

living was added. This policy of anti-ornamentation began its life as a

pragmatic choice, a means to turn a quick pro t, rather than an

aesthetic one. Nonetheless it has echoed powerfully down the

centuries, ending up as the grammar at the heart of Modernism.

This ‘Billy bookcase’ of a house was the archetypal Georgian terrace.

Yet even this new urban form was governed by the developer’s desire to

improve their margins. According to leasehold regulations, the

speculator was encouraged to pack as many houses as possible along a

street front, so as to collect as much ground rent as possible. This

forced the average house to have a thin frontage, to extend backwards

as far as the lease allowed, and to be tall. This calculation was the

algorithm in the architectural operating system that ran from the

1670s, all the way to within living memory. It in uenced the English

ideal of what a home is, a prototype that can be seen from the noble

houses of Bloomsbury, the silk merchants homes on Fournier Street,

Spital elds, and the townhouses of Kensington, to the Victorian

terraces of inner suburbs.

And what about how the city is nanced? Recently, Peter Wynne Rees,

the former head planner of the City of London, noted that we were

currently living through a second Great Fire moment. The fabric of the

city was changing at a rate that had not been seen since the 1670–90s

when ⅓ of teh city was burned down and rebuilt within a generation.

He is probably right but Wynne Rees was not just concerned about the

speed of change but what shape the new city was taking. Instead of the

historic fabric, he observed, London is becoming overrun with what he

terms ‘safe deposit’ towers: ‘many of dubious architectural quality, are

sold o -plan to the world’s “uber-rich”, as a repository for their spare

and suspect capital’.

Wynne Rees’ remarks recombine the ‘what’ and the ‘how’ of urban

development: the architectural form is indistinguishable from its

nancing. But where that money comes from has changed since the

1690s. Barbon gained his money from local merchants and friends. He

was also able to persuade the builders to invest in their own projects,

rather than o er up his own cash as collateral.

He was a man who understood money. He set up the very rst re

insurance o ce, the Phenix. He also came very close to setting up a

nation land bank that would have acted as the Bank of England itself,

gaining royal assent before collapsing. The scheme failed when Barbon

was asked to raise £2.5 million for the government, and could only

muster £2,100. Perhaps more signi cantly, in 1695, he got into an

argument with the philosopher John Locke on the nature of money.

Locke proposed that money’s intrinsic value was in its coinage; the

silver determined the coin’s worth. Barbon pushed this aside, claiming

that money was anything that the law said it was: ‘it is not absolutely

necessary money should be made of gold or silver; for having its sole

value from the law, it is not material upon what metal the stamp be set.’

Looking once again at the skyline of the neoliberal city, perhaps this is

Barbon’s greatest legacy. Long after he died, on the verge of

bankruptcy, refusing to pay any debts but the cost of his wife’s funeral,

this is what he really left the city. The idea that the city can rise on

nothing but imaginary money.

Returning to the Nine Elms development, we see Barbon’s legacy. Most

of the ats within the development were sold before completion, often

with foreign buyers putting down a deposit, and paying the rest of the

price on receipt for the front door keys. However, over summer 2015,

the real estate website Rightmove was doing a steady business on these

imaginary residences. As one estate agent, interviewed by the Financial

Times noted: ‘A lot of these buyers are e ectively taking a nancial

position rather than buying a property.’ It is not Barbon the developer

that we should be most fearful of, it is Barbon the nancier.

[this article rst appeared in the rst edition of REAL review. To nd

out more and subscribe — check here: http://real.foundation/]

You might also like

- Stalking DetroitDocument118 pagesStalking Detroitylanda ill100% (4)

- Robert O. Bucholz, Joseph P. Ward - London - A Social and Cultural History, 1550-1750-Cambridge University Press (2012) PDFDocument479 pagesRobert O. Bucholz, Joseph P. Ward - London - A Social and Cultural History, 1550-1750-Cambridge University Press (2012) PDFNicolRamosMella100% (1)

- Ossulston Street Early LCC Experiments in High Rise Housing 1925 29Document21 pagesOssulston Street Early LCC Experiments in High Rise Housing 1925 29Gillian WardellNo ratings yet

- KCA Book All Low ResDocument30 pagesKCA Book All Low Resylanda illNo ratings yet

- The Compilation and Reliability of London Directories, 1989Document15 pagesThe Compilation and Reliability of London Directories, 1989Peter J. AtkinsNo ratings yet

- A New London Housing VernacularDocument12 pagesA New London Housing VernacularPaul ReynoldsNo ratings yet

- Patrick Abercrombie Final (2003)Document54 pagesPatrick Abercrombie Final (2003)Saajan Sharma89% (18)

- Peabody Design GuideDocument109 pagesPeabody Design Guideylanda illNo ratings yet

- Asaf Touchmair - Bio & Portfolio Presentation - אסף טוכמאייר - מצגת ביוגרפיה ופורטפוליוDocument33 pagesAsaf Touchmair - Bio & Portfolio Presentation - אסף טוכמאייר - מצגת ביוגרפיה ופורטפוליואסי טוכמאייר - Asaf TuchmairNo ratings yet

- Ironton Spina Hotel Reuse Study (2001)Document60 pagesIronton Spina Hotel Reuse Study (2001)cuyunaNo ratings yet

- Going South: The New San Antonio Main LibraryDocument3 pagesGoing South: The New San Antonio Main LibraryTexas Public RadioNo ratings yet

- Barbican A Unique Walled City Within TheDocument79 pagesBarbican A Unique Walled City Within Thezagarin_madalina2685No ratings yet

- Great Estates of LondonDocument56 pagesGreat Estates of LondonantonyNo ratings yet

- Parnell House Information Sheet 2024Document2 pagesParnell House Information Sheet 2024Julia da Costa AguiarNo ratings yet

- RESEARCHDocument10 pagesRESEARCHJesus RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Stepney and The Politics of High Rise Housing Limehouse Fields To John Scurr House 1925 1937Document23 pagesStepney and The Politics of High Rise Housing Limehouse Fields To John Scurr House 1925 1937Gillian WardellNo ratings yet

- Sharp LesDocument5 pagesSharp LesconsulusNo ratings yet

- The Shape of Britain To Come As Designed by Prince CharlesDocument6 pagesThe Shape of Britain To Come As Designed by Prince CharlesBesim HakimNo ratings yet

- Milne, Erber, UH 2021Document26 pagesMilne, Erber, UH 2021volpedoNo ratings yet

- London's Sinful Secret: The Bawdy History and Very Public Passions of London's Georgian AgeFrom EverandLondon's Sinful Secret: The Bawdy History and Very Public Passions of London's Georgian AgeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (7)

- Urban Renewal DefinitionDocument11 pagesUrban Renewal DefinitionJose SibiNo ratings yet

- The English Home from Charles I. to George IV: Its Architecture, Decoration and Garden DesignFrom EverandThe English Home from Charles I. to George IV: Its Architecture, Decoration and Garden DesignNo ratings yet

- Berlin and London Two CulturesDocument12 pagesBerlin and London Two CulturesHasanain KarbolNo ratings yet

- A Critical Evaluation of Public SpaceDocument19 pagesA Critical Evaluation of Public SpaceindianteenvNo ratings yet

- London and Its Environs Described Vol. 4 of 6Document191 pagesLondon and Its Environs Described Vol. 4 of 6J GroningerNo ratings yet

- Mmep Lecture Note - Planning HistoryDocument5 pagesMmep Lecture Note - Planning HistoryMel FNo ratings yet

- Lancashire Brief Historical and Descriptive NotesFrom EverandLancashire Brief Historical and Descriptive NotesNo ratings yet

- The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction Volume 19, No. 529, January 14, 1832From EverandThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction Volume 19, No. 529, January 14, 1832No ratings yet

- The Speculative Builders and Developers of Victorian LondonDocument51 pagesThe Speculative Builders and Developers of Victorian LondonGergő HegedüsNo ratings yet

- The Swearer’s Bank by Jonathan Swift - Delphi Classics (Illustrated)From EverandThe Swearer’s Bank by Jonathan Swift - Delphi Classics (Illustrated)No ratings yet

- Myth, Folklore, Legend and Literature)Document12 pagesMyth, Folklore, Legend and Literature)Hustiuc RomeoNo ratings yet

- Byker StateDocument10 pagesByker StateTOPAtankNo ratings yet

- The History of London: A Very Historic CityDocument5 pagesThe History of London: A Very Historic CityKesetovic MeldinNo ratings yet

- Lippincott's Magazine of Popular Literature and Science, Volume 22. October, 1878.From EverandLippincott's Magazine of Popular Literature and Science, Volume 22. October, 1878.No ratings yet

- How Many Times Should We Say ItDocument4 pagesHow Many Times Should We Say ItHiren DesaiNo ratings yet

- Constitutions York 926Document55 pagesConstitutions York 926pedrazas100% (1)

- Hiller2019 Chapter Period2LondonInTheEnlightenmenDocument50 pagesHiller2019 Chapter Period2LondonInTheEnlightenmenFermilyn AdaisNo ratings yet

- Kobelco Hydraulic Excavator Sk130lc 11 Shop Manual S5lp0011e02Document22 pagesKobelco Hydraulic Excavator Sk130lc 11 Shop Manual S5lp0011e02maryolson060292tok100% (128)

- William The Conquerors Writ For The City of LondoDocument14 pagesWilliam The Conquerors Writ For The City of LondoWilliam LaingNo ratings yet

- The Vertical Urban Environment of Hong KongDocument5 pagesThe Vertical Urban Environment of Hong KongclaudiocacciottiNo ratings yet

- The Book of HousesDocument150 pagesThe Book of Housesaioria10No ratings yet

- The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction Volume 17, No. 490, May 21, 1831From EverandThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction Volume 17, No. 490, May 21, 1831No ratings yet

- Bloomberg - How Leeds Kept The Back-to-Back House Alive by Robert BevanDocument12 pagesBloomberg - How Leeds Kept The Back-to-Back House Alive by Robert BevanrpmbevanNo ratings yet

- Rarebooksoffreem 00 VibeDocument52 pagesRarebooksoffreem 00 Vibedeezerm31No ratings yet

- Organic Architecture - Maggie Toy - 1993 - London - Academy Editions New York - Distributed in The U.S. - 9781854902375 - Anna's ArchiveDocument124 pagesOrganic Architecture - Maggie Toy - 1993 - London - Academy Editions New York - Distributed in The U.S. - 9781854902375 - Anna's Archivehawikassahun816No ratings yet

- The Great Plague and The Great Fire-12ADocument3 pagesThe Great Plague and The Great Fire-12AAdrianaNo ratings yet

- Dublin Docs V04Document620 pagesDublin Docs V04Geordie Winkle100% (1)

- The Collector Essays on Books, Newspapers, Pictures, Inns, Authors, Doctors, Holidays, Actors, PreachersFrom EverandThe Collector Essays on Books, Newspapers, Pictures, Inns, Authors, Doctors, Holidays, Actors, PreachersNo ratings yet

- Transactions of The Town Planning ConferenceDocument898 pagesTransactions of The Town Planning ConferenceFernando Mazo100% (1)

- Welcome to New London: Journeys and encounters in the post-Olympic cityFrom EverandWelcome to New London: Journeys and encounters in the post-Olympic cityNo ratings yet

- The Art of Architecture A Poem In Imitation of Horace's Art of PoetryFrom EverandThe Art of Architecture A Poem In Imitation of Horace's Art of PoetryNo ratings yet

- The Straight and The Curved:Design Alternatives: Leon Battista AlbertiDocument4 pagesThe Straight and The Curved:Design Alternatives: Leon Battista AlbertiMushfiq HumamNo ratings yet

- Catalogue of WorksDocument36 pagesCatalogue of Workstwinkle4545No ratings yet

- 2519 8409 1 PBDocument15 pages2519 8409 1 PBylanda illNo ratings yet

- TilesDocument1 pageTilesylanda illNo ratings yet

- Defensible SpaceDocument51 pagesDefensible Spaceylanda illNo ratings yet

- Becher Bernd and Hilla Gas TanksDocument126 pagesBecher Bernd and Hilla Gas Tanksylanda illNo ratings yet

- A Architecture 03Document21 pagesA Architecture 03ylanda illNo ratings yet

- Interview With Anne Lacaton Lacaton andDocument16 pagesInterview With Anne Lacaton Lacaton andsaba azaNo ratings yet

- Tall Buildings: Tallest Buildings in The WorldDocument7 pagesTall Buildings: Tallest Buildings in The Worldgatekeep02100% (1)

- Imaginary City - Leo Hollis - MediumDocument4 pagesImaginary City - Leo Hollis - Mediumylanda illNo ratings yet

- Bloomberg HQ Case StudyDocument5 pagesBloomberg HQ Case StudyMoheb RagaïNo ratings yet

- Project Report On: "Design of A Residential Building"Document25 pagesProject Report On: "Design of A Residential Building"swatantra boseNo ratings yet

- Stepwise Construction Procedure of Buildings - Roll No. 181001Document15 pagesStepwise Construction Procedure of Buildings - Roll No. 181001Prafful BahiramNo ratings yet

- Koolhaas The Frontier in The SkyDocument14 pagesKoolhaas The Frontier in The SkyNadezda SassinaNo ratings yet

- Burj KhalifaDocument6 pagesBurj KhalifaAlzio Rajendra AidiantraNo ratings yet

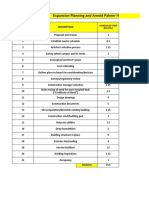

- Expansion Planning and Arnold Palmer Hospital Construction Activities and TimesDocument18 pagesExpansion Planning and Arnold Palmer Hospital Construction Activities and TimesRobin LusabioNo ratings yet

- Sr. No. BIM Companies Name Revenue Top 140 Bim Architecture FirmsDocument7 pagesSr. No. BIM Companies Name Revenue Top 140 Bim Architecture FirmsChirag MehtaNo ratings yet

- David Reiza Mae C. Midterm Plate 1Document8 pagesDavid Reiza Mae C. Midterm Plate 1agustingiovanni218No ratings yet

- Reflected Ceiling GFDocument1 pageReflected Ceiling GFjerico darlucioNo ratings yet

- 1 Unified Application For BLDG Permit Front DPWHDocument1 page1 Unified Application For BLDG Permit Front DPWHMirzi Olga Breech SilangNo ratings yet

- Burj KhalifaDocument5 pagesBurj KhalifaSara MursiNo ratings yet

- Architectural Firm Details: S. No Address Place Name of The OrganisationDocument5 pagesArchitectural Firm Details: S. No Address Place Name of The OrganisationAr Sonali HadkeNo ratings yet

- Casa Uluwatu - Detail StorageDocument12 pagesCasa Uluwatu - Detail StorageAyu SawitriNo ratings yet

- QUESTIONS of AREA 1Document20 pagesQUESTIONS of AREA 1JHONA THE IGUANANo ratings yet

- Bulider List 13JDocument104 pagesBulider List 13JABHISHEK SHARMANo ratings yet

- The Competition For Brasilia's Pilot Plan: Territory and InfrastructureDocument6 pagesThe Competition For Brasilia's Pilot Plan: Territory and Infrastructurealejandro ramirezNo ratings yet

- Technical Plans-T&B1Document1 pageTechnical Plans-T&B1Gabby GallardoNo ratings yet

- A+t DBOOK Digital Files IndexDocument1 pageA+t DBOOK Digital Files Indexlilz90No ratings yet

- 16 Sec - 44 Typical Floor Working PlanDocument1 page16 Sec - 44 Typical Floor Working PlanManoj KumarNo ratings yet

- Footing and Column LayoutDocument1 pageFooting and Column LayoutJennifer Dumagpi DemapitanNo ratings yet

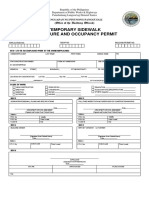

- Temporary Sidewalk Enclosure and Occupancy Permit (Front)Document1 pageTemporary Sidewalk Enclosure and Occupancy Permit (Front)The MatrixNo ratings yet

- Gene Summers (Architect) - Wikipedia PDFDocument5 pagesGene Summers (Architect) - Wikipedia PDFChillyNo ratings yet

- الإسكان الجماعي وإعادة الاستخدام التكيفي المفاهيم الحديثة مقابل المعاصرة للجماعةDocument8 pagesالإسكان الجماعي وإعادة الاستخدام التكيفي المفاهيم الحديثة مقابل المعاصرة للجماعةzainab abbasNo ratings yet

- Be Circular Safety of DemolitionDocument11 pagesBe Circular Safety of DemolitionLim Kang HaiNo ratings yet