Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sts

Uploaded by

Maria ClaraOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Sts

Uploaded by

Maria ClaraCopyright:

Available Formats

Is the Assyrian Nimrud lens the oldest telescope

in the world?

The Nimrud lens is a 3,000-year-old piece of rock crystal, which was

unearthed by Sir John Layard in 1850 at the Assyrian palace of Nimrud, in

modern-day Iraq. The Nimrud lens (also called the Layard lens) is made

from natural rock crystal and is a slightly oval in shape. It was roughly

ground, perhaps on a lapidary wheel. It has a focal point about 11

centimetres from the flat side, and a focal length of about 12 cm. This

would make it equivalent to a 3× magnifying glass (combined with

another lens, it could achieve much greater magnification). The surface of

the lens has twelve cavities that were opened during grinding, which

would have contained naptha or some other fluid trapped in the raw

crystal.

The ancient invention of the steam engine by

the Hero of Alexandria

Heron Alexandrinus, otherwise known as the Hero of Alexandria, was a 1 st

century Greek mathematician and engineer who is known as the first inventor of the

steam engine. His steam powered device was called the aeolipile, named after

Aiolos, God of the winds. The aeolipile consisted of a sphere positioned in such a way

that it could rotate around its axis. Nozzles opposite each other would expel steam

and both of the nozzles would generate a combined thrust resulting in torque,

causing the sphere to spin around its axis. The rotation force sped up the sphere up

to the point where the resistance from traction and air brought it to a stable rotation

speed. The steam was created by boiling water under the sphere – the boiler was

connected to the rotating sphere through a pair of pipes that at the same time

served as pivots for the sphere. The replica of Heron’s machine could rotate at 1,500

rounds per minute with a very low pressure of 1.8 pounds per square inch. The

remarkable device was forgotten and never used properly until 1577, when the

steam engine was ‘re-invented’ by the philosopher, astronomer and engineer, Taqu

al-Din.

The Oldest Calendar in Scotland

Research carried out last year on an ancient site excavated by the National

Trust for Scotland in 2004 revealed that it contained a sophisticated calendar system

that is approximately 10,000 years old, making it the oldest calendar ever

discovered in the world. The site – at Warren Field, Crathes, Aberdeenshire –

contains a 50 metre long row of twelve pits which were created by Stone Age Britons

and which were in use from around 8000 BC (the early Mesolithic period) to around

4,000 BC (the early Neolithic). The pits represent the months of the year as well as

the lunar phases of the moon. They were formed in a complex arc design in which

each lunar month was divided into three roughly ten day weeks – representing the

waxing moon, the full moon and the waning moon. It also allowed the observation of

the mid-winter sunrise so that the lunar calendar could be recalibrated each year to

bring it back in line with the solar year. The entire arc represents a whole year and

may also reflect the movements of the moon across the sky.

1,600-year-old goblet shows that the Romans used

nanotechnology

The Lycurgus Cup, as it is known due to its depiction of a scene involving King

Lycurgus of Thrace, is a 1,600-year-old jade green Roman chalice that changes

colour depending on the direction of the light upon it. It baffled scientists ever since

the glass chalice was acquired by the British Museum in the 1950s. They could not

work out why the cup appeared jade green when lit from the front but blood red

when lit from behind. The mystery was solved in 1990, when researchers in England

scrutinized broken fragments under a microscope and discovered that the Roman

artisans were nanotechnology pioneers: they had impregnated the glass with

particles of silver and gold, ground down until they were as small as 50 nanometres

in diameter, less than one-thousandth the size of a grain of table salt. The work was

so precise that there is no way that the resulting effect was an accident. In fact, the

exact mixture of the metals suggests that the Romans had perfected the use of

nanoparticles. When hit with light, electrons belonging to the metal flecks vibrate in

ways that alter the colour depending on the observer’s position.

Mythical sunstone used as ancient navigational

device

An ancient Norse myth described a magical gem used to navigate the seas, which could

reveal the position of the sun when hidden behind clouds or even before dawn or after sunset. Now

it appears the myth is in fact true. In March 2013, a team of scientists announced that a unique

calcite crystal, which was found in the wreck of an Elizabethan ship sunk off the Channel Islands,

contains properties consistent with the legendary Viking sunstone and that shards of the crystal

can indeed act as a remarkably precise navigational aid. According to the researchers, the

principle behind the sunstone relies on its unusual property of creating a double refraction of

sunlight, even when it is obscured by cloud or fog. By turning the crystal in front of the human eye

until the darkness of the two shadows are equal, the sun's position can be pinpointed with

remarkable accuracy.

The Baghdad Battery

The Baghdad Battery, sometimes referred to as the Parthian Battery, is a clay

pot which encapsulates a copper cylinder. Suspended in the centre of this cylinder—

but not touching it—is an iron rod. Both the copper cylinder and the iron rod are held

in place with an asphalt plug. These artifacts (more than one was found) were

discovered during the 1936 excavations of the old village Khujut Rabu, near

Baghdad. The village is considered to be about 2000 years old, and was built during

the Parthian period (250BC to 224 AD). Although it is not known exactly what the use

of such a device would have been, the name ‘Baghdad Battery’, comes from one of

the prevailing theories established in 1938 when Wilhelm Konig, the German

archaeologist who performed the excavations, examined the battery and concluded

that this device was an ancient electric battery. After the Second World War, Willard

Gray, an American working at the General Electric High Voltage Laboratory in

Pittsfield, built replicas and, filling them with an electrolyte, found that the devices

could produce 2 volts of electricity. The question remains, if it really was a battery,

what was it used to power?

You might also like

- NCLEX Questions Therapeutic CommunicationDocument11 pagesNCLEX Questions Therapeutic CommunicationMaria ClaraNo ratings yet

- NSTP ModuleDocument8 pagesNSTP ModuleMaria ClaraNo ratings yet

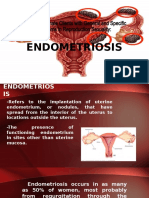

- ENDOMETRIOSISDocument29 pagesENDOMETRIOSISMaria ClaraNo ratings yet

- BREAKTHESILENCEDocument10 pagesBREAKTHESILENCEMaria ClaraNo ratings yet

- Bomb ThreatDocument2 pagesBomb ThreatMaria ClaraNo ratings yet

- Stress: What Is It?Document7 pagesStress: What Is It?Maria ClaraNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5796)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (589)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Ansi Ies RP-8-21Document547 pagesAnsi Ies RP-8-21cristianbaileyeNo ratings yet

- FORM 5 VariationDocument35 pagesFORM 5 VariationAMOS YAP WEI KANG MoeNo ratings yet

- Traffic Engineering Third Edition by Roess & Prasas 2004 PDFDocument802 pagesTraffic Engineering Third Edition by Roess & Prasas 2004 PDFdanielNo ratings yet

- Sensory Aspects of Retailing: Theoretical and Practical ImplicationsDocument5 pagesSensory Aspects of Retailing: Theoretical and Practical ImplicationsΑγγελικήΝιρούNo ratings yet

- Isotermas de Sorcion ManzanaDocument12 pagesIsotermas de Sorcion ManzanaFELIPEGORE ArbeláezNo ratings yet

- Angkur BetonDocument36 pagesAngkur BetonmhadihsNo ratings yet

- Mobile Management SystemDocument9 pagesMobile Management SystemNaga Sai Anitha NidumoluNo ratings yet

- In Praise of LongchenpaDocument3 pagesIn Praise of LongchenpaJigdrel77No ratings yet

- TEGOPAC Bond251 012016Document2 pagesTEGOPAC Bond251 012016Pranshu JainNo ratings yet

- ILSAS DistributionDocument15 pagesILSAS DistributionFaizal FezalNo ratings yet

- Persuasive Speech OutlineDocument4 pagesPersuasive Speech Outlineapi-311196068No ratings yet

- TraderJoes CookbookDocument150 pagesTraderJoes Cookbookjennifer.farris12No ratings yet

- Atmel 11121 32 Bit Cortex A5 Microcontroller SAMA5D3 DatasheetDocument1,710 pagesAtmel 11121 32 Bit Cortex A5 Microcontroller SAMA5D3 DatasheetCan CerberusNo ratings yet

- Final Thesis RandaDocument175 pagesFinal Thesis RandaAhmi KhanNo ratings yet

- Mock 1 QP (PQ, Kine, Dyna)Document28 pagesMock 1 QP (PQ, Kine, Dyna)Tahmedul Hasan TanvirNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of PV-Wind Hybrid Energy System For A Small IslandDocument3 pagesEvaluation of PV-Wind Hybrid Energy System For A Small Islandhamza malikNo ratings yet

- Basic - Digital - Circuits v7Document64 pagesBasic - Digital - Circuits v7Marco LopezNo ratings yet

- Beacon Atlantic Short Spec R1 141118 NBDocument4 pagesBeacon Atlantic Short Spec R1 141118 NBRayodcNo ratings yet

- CHARLOTTEDocument18 pagesCHARLOTTEravenNo ratings yet

- ECOS Data Report 3063Document13 pagesECOS Data Report 3063Sarra Chouchene0% (1)

- K3M 2008 - Form 6Document15 pagesK3M 2008 - Form 6SeanNo ratings yet

- ERAS DR - TESAR SP - AnDocument26 pagesERAS DR - TESAR SP - AnAhmad Rifai R ANo ratings yet

- Templar BuildsDocument18 pagesTemplar Buildsel_beardfaceNo ratings yet

- Vanishing TieDocument14 pagesVanishing TieIchwalsyah SyNo ratings yet

- Gandolfi - L'Eclissi e L'orbe Magno Del LeoneDocument24 pagesGandolfi - L'Eclissi e L'orbe Magno Del LeoneberixNo ratings yet

- Recipe For BPP Ncii UaqteaDocument11 pagesRecipe For BPP Ncii UaqteaPJ ProcoratoNo ratings yet

- MST WRN Overview UsDocument4 pagesMST WRN Overview UsedgarNo ratings yet

- 2 Calculating Fabric-VivasDocument9 pages2 Calculating Fabric-VivasLara Jane DogoyNo ratings yet

- N61PC-M2S & N68SB-M2S - 100504Document45 pagesN61PC-M2S & N68SB-M2S - 100504cdstaussNo ratings yet

- Owner'S Manual: Operation Maintenance Parts ListDocument130 pagesOwner'S Manual: Operation Maintenance Parts ListDmitryNo ratings yet