Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Pyelitis Emfisematus

Uploaded by

taufikolingOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Pyelitis Emfisematus

Uploaded by

taufikolingCopyright:

Available Formats

Open Access Case

Report DOI: 10.7759/cureus.1612

Foley Follies: Emphysematous Pyelitis from

Instrumentation in Obstructive Uropathy

Shimshon Wiesel 1 , Anna Gutman 1 , Jonah E. Abraham 2 , Militza Kiroycheva 3

1. Internal Medicine, Staten Island University Hospital, Northwell Health 2. Department of

Anesthesiology, University of Pittsburg Medical Center 3. Department of Nephrology, Staten Island

University Hospital, Northwell Health

Corresponding author: Shimshon Wiesel, shimshon.wiesel@gmail.com

Disclosures can be found in Additional Information at the end of the article

Abstract

Emphysematous pyelitis (EP) is a subclass of a life-threatening necrotizing infection of the

urinary system called emphysematous pyelonephritis (EPN). We report a case of an 81-year-old

man with emphysematous pyelitis, which occurred after urinary tract instrumentation and

resolved with conservative medical management. This case highlights the potential

complications of urinary tract manipulation and the importance of a prompt diagnosis.

Categories: Urology, Nephrology, Quality Improvement

Keywords: urinary tract infection, acute kidney injury, emphysematous pyelitis, foley catheter,

iatrogenic injuries, hydronephrosis

Introduction

Emphysematous pyelitis (EP) is a subclass of a necrotizing infection of the urinary system

called emphysematous pyelonephritis (EPN). EPN is a life-threatening medical

emergency occurring mostly in women with diabetes mellitus (DM). We report a case of an 81-

year-old nondiabetic man who developed EP after urinary tract manipulation.

Case Presentation

An 81-year-old man presented to our hospital for infected lower extremity ulcers and

worsening kidney function. His past medical history was significant for benign prostatic

hyperplasia, chronic kidney disease stage IIIb, hypertension, and peripheral artery disease. On

physical examination, he had a temperature of 98.7F, heart rate of 85 beats per minute,

respiratory rate of 16 breaths per minute, blood pressure of 138/72 mm Hg, and oxygen

saturation of 98% when breathing ambient air. The patient had a 1+ pitting edema in both

Received 07/27/2017 lower extremities and infected ulcers on the right hallux and the right calf. The rest of his

Review began 08/17/2017

physical examination was normal.

Review ended 08/22/2017

Published 08/26/2017

The patient's serum creatinine (sCr) was 3.12 milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL), which

© Copyright 2017

Wiesel et al. This is an open access was elevated from his outpatient baseline of 1.69 mg/dL, and urea nitrogen was 32 mg/dL. His

article distributed under the terms of urinalysis showed small blood, large leukocytes, and 30 mg/dL of protein on urine dipstick, 20

the Creative Commons Attribution to 30 white blood cells per high power field (p/hpf), three to six red blood cells p/hpf, few

License CC-BY 3.0., which permits

hyaline casts p/hpf, and occasional mucous threads on microscopic examination. His serum

unrestricted use, distribution, and

total protein, albumin, complement, low-density lipoprotein, and high-density lipoprotein

reproduction in any medium,

provided the original author and levels were normal. Antiproteinase 3 antibodies, anti-myeloperoxidase antibodies, and

source are credited. antinuclear antibodies were negative. A renal ultrasound showed bilateral

hydroureteronephrosis and a postvoid residual urine volume of 350 milliliters.

How to cite this article

Wiesel S, Gutman A, Abraham J E, et al. (August 26, 2017) Foley Follies: Emphysematous Pyelitis from

Instrumentation in Obstructive Uropathy. Cureus 9(8): e1612. DOI 10.7759/cureus.1612

An indwelling urinary catheter was placed, and intravenous fluids were administered. The

patient’s sCr level improved 24 hours after introducing the urinary catheter. A repeat

ultrasound was done 48 hours after the urinary catheter placement, which showed bilateral

renal collecting shadowing echogenic foci, consistent with possible EP. A computed

tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis without contrast showed mild bilateral

hydronephrosis with air seen throughout the collecting systems and ureters (Figure 1). The

urine gram stain and culture were negative and the patient’s antibiotic regimen was changed

from ampicillin-sulbactam to vancomycin and ertapenem empirically due to a recent

hospitalization and antibiotics use.

FIGURE 1: Coronal CT abdomen and pelvis

A coronal view illustrating air in the bilateral renal pelvises with extension into the ureters

(arrows) without parenchymal renal involvement. The fat-stranding of the bilateral kidneys is

illustrated (asterisks). There is also air at the left ureterovesicular junction (arrowhead).

CT = computed tomography

Throughout his hospitalization, the patient denied abdominal pain, flank pain, suprapubic

pain, dysuria, or urinary urgency, and he remained afebrile, with stable vital signs. His renal

function improved to its pre-admission baseline, so a percutaneous catheter drainage (PCD) of

the renal pelvises was not performed. The patient was sent home with the urinary catheter in

place on an antibiotics regimen of vancomycin and ertapenem for a total of 14 days. He was

instructed to have a close follow-up with his primary care physician, urologist, and

nephrologist. Follow-up details were obtained from the patient’s primary care physician, who

informed us that a subsequent CT of the patient’s abdomen and pelvis demonstrated complete

resolution of his EP.

2017 Wiesel et al. Cureus 9(8): e1612. DOI 10.7759/cureus.1612 2 of 5

Discussion

EPN is a rare, but life-threatening, acute necrotizing infection of the kidney, first clinically

described by Kelly and MacCallum in 1898. EPN is defined as gas within the renal parenchyma,

collecting system, or perinephric tissues [1]. EP is a subclass of EPN, in which gas is confined to

the renal collecting system.

EPN is a disease more commonly seen in women than in men, with a female-to-male ratio of 3

to 1, presumably because of women's increased susceptibility to urinary tract infections

[1]. Over 90% of patients with EPN have diabetes mellitus (DM) [2], whereas EP is usually

associated with urinary tract obstruction [3]. Only 50% of patients with EP have DM, compared

to the > 90% of patients with EPN class II or higher. The most common cause of urinary tract

obstruction that leads to EP is renal calculi [4].

Urinary tract obstruction causes EPN by impairing the transportation of formed gas, which

increases local pressure in the tissue and impairs circulation. Impaired circulation leads to

infarction, which provides a culture medium for gas-forming pathogens, thereby creating a

vicious cycle [3]. Gas appearing in the urinary system may also be caused by fistulae originating

in the gastrointestinal tract, gas reflux from the urinary bladder, trauma, and urinary system

interventional procedures [4].

EPN is caused by organisms that ferment glucose and lactate into carbon dioxide and hydrogen

gas. The organisms involved are usually enteric facultative anaerobic bacteria, such as

Escherichia coli, Proteus mirabilis, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterococcus species, and

Pseudomonas aeruginosa; occasionally, gram positive bacteria, such as Streptococci

species; and fungi such as Candida albicans [1]. Patients with DM provide a favorable

environment for gas-forming microbes because of the high levels of glucose in their tissues and

urine, which is used as a substrate for fermentation.

The common clinical features of EPN include fever, chills, costovertebral angle tenderness,

vomiting, dysuria, and, rarely, crepitus in the lumbar region [1]. The risk factors associated with

high mortality rates from EPN are thrombocytopenia, altered mental status, severe proteinuria,

shock, extension of the infection to the perinephric space, renal replacement therapy

dependence, hypoalbuminemia, and polymicrobial infections [1,5-6].

The diagnosis of EPN is established by demonstrating gas in the urinary system, renal

parenchyma, or perinephric tissue by a plain abdominal radiograph or a renal ultrasound. A CT

scan of the abdomen and pelvis can confirm the diagnosis and show the extent of the disease,

thus being the ideal test for the diagnosis of EPN [5]. A poor response to antibiotic therapy in a

patient with DM, with a seemingly uncomplicated pyelonephritis, should raise suspicion of EPN

and warrant a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis to rule out this life-threatening condition [1].

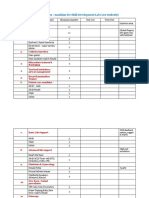

EPN is divided into four classes [5], which are determined according to the extent of the gas

expansion (Table 1). The gas may be limited to the collecting system or expand through the

renal parenchyma and retroperitoneal space. Miller et al. described a severe case of EPN, in

which gas extended through the retroperitoneal space and invaded the inferior vena cava [2].

The treatment of EPN remains controversial. Early nephrectomy was the treatment of choice in

the 1980s, with a general consensus that medical therapy without surgical intervention has

higher rates of mortality [7]. Studies in the 1990s proposed antibiotic therapy combined with

CT-guided percutaneous drainage (PCD) as an acceptable alternative to nephrectomy [8], which

lowered mortality rates by as much as 21% [6]. Further studies in the last two decades

continue to demonstrate a significantly lower mortality rate with PCD alongside medical

2017 Wiesel et al. Cureus 9(8): e1612. DOI 10.7759/cureus.1612 3 of 5

management compared to early nephrectomy in most classes of EPN [6,8].

Empiric antimicrobials should primarily target gram-negative bacteria. Third-generation

cephalosporins are recommended as the initial treatment of EPN. Carbapenems, frequently

used in combination with vancomycin, are the empiric antibiotic of choice for patients with

prior hospitalization and antibiotics use within the last year, patients requiring hemodialysis,

and patients who develop disseminated intravascular coagulation. PCD and the placement of

double-J catheters are often performed in conjunction with medical treatment to maximize

nephron sparing, which significantly lowers the rate of mortality. Salvage nephrectomy or open

drainage is usually performed when PCD or conservative treatments fail or have a high

probability of failing [5,9]. A 25% mortality rate has been observed in patients undergoing an

emergency nephrectomy, 50% with medical management, and only 13% with medical

management and PCD [10].

Huang and Tseng proposed common guidelines for the treatment of EPN (Table 1). Most classes

of EPN require antibiotics and PCD. Nephrectomy is currently reserved patients with class III

EPN with multiple risk factors and class IV if antibiotics and PCD fail.

Class Gas Location Management*

I** collecting system antibiotics and PCD

II renal parenchyma antibiotics and PCD

extension to the space between the fibrous renal capsule < 2 risk factors***, PCD and antibiotics; 2 or

IIIA

and the renal fascia (perinephric space) more risk factors, early nephrectomy

extension to the space beyond the renal fascia and/or < 2 risk factors***, PCD and antibiotics; 2 or

IIIB

extension to adjacent tissues (pararenal space) more risk factors, early nephrectomy

trial of antibiotics and PCD; nephrectomy if

IV bilateral kidneys or a solitary functioning kidney

antibiotics and PCD fail

TABLE 1: EPN classification and management

*For all classes: relief of any existing urinary tract obstruction

** Emphysematous pyelitis

***That is, thrombocytopenia, acute kidney injury, altered mental status, shock

PCD = Percutaneous drainage

Conclusions

Our patient had a negative urine culture, however, his concomitant antibiotic coverage for a

coexisting infection may have altered the validity of the urine cultures. Nevertheless, the

differential diagnosis of air in the collecting ducts of the urinary system is not confined to

infectious causes and the placement of a urinary catheter in the setting of a postrenal

obstruction may have caused an iatrogenic EP. Individual analyses of the risks and benefits of

2017 Wiesel et al. Cureus 9(8): e1612. DOI 10.7759/cureus.1612 4 of 5

choosing surgical intervention in addition to medical management should be evaluated on a

case-by-case basis.

Additional Information

Disclosures

Human subjects: Consent was obtained by all participants in this study. Conflicts of interest:

In compliance with the ICMJE uniform disclosure form, all authors declare the following:

Payment/services info: All authors have declared that no financial support was received from

any organization for the submitted work. Financial relationships: All authors have declared

that they have no financial relationships at present or within the previous three years with any

organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work. Other relationships: All

authors have declared that there are no other relationships or activities that could appear to

have influenced the submitted work.

References

1. Misgar RA, Mubarik I, Wani AI, Bashir MI, Ramzan M, Laway BA: Emphysematous

pyelonephritis: a 10-year experience with 26 cases. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2016, 20:475–

480. 10.4103/2230-8210.183475

2. Miller AC, Scheer D, Silverberg M: Emphysematous pyelonephritis and pneumo-vena cava .

West J Emerg Med. 2010, 11:518–519.

3. Grupper M, Kravtsov A, Potasman I: Emphysematous cystitis: illustrative case report and

review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2007, 86:47–53.

10.1097/MD.0b013e3180307c3a

4. Kua C, Abdul Aziz Y: Air in the kidney: between emphysematous pyelitis and pyelonephritis .

Biomed Imaging Interv J. 2008, 4:24.

5. Huang JJ, Tseng CC: Emphysematous pyelonephritis: clinicoradiological classification,

management, prognosis, and pathogenesis. Arch Intern Med. 2000, 160:797–805.

10.1001/archinte.160.6.797

6. Aboumarzouk OM, Hughes O, Narahari K, et al.: Emphysematous pyelonephritis: time for a

management plan with an evidence-based approach. Arab J Urol. 2014, 12:106–115.

10.1016/j.aju.2013.09.005

7. Cook DJ, Achong MR, Dobranowski J: Emphysematous pyelonephritis. Complicated urinary

tract infection in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1989, 12:229–232. 10.2337/diacare.12.3.229

8. Chen MT, Huang CN, Chou YH, Huang CH, Chiang CP, Liu GC: Percutaneous drainage in the

treatment of emphysematous pyelonephritis: 10-year experience. J Urol. 1997, 157:1569–

1573. 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)64797-9

9. Lu YC, Hong JH, Chiang BJ, Pong YH, Hsueh P-R; Huang C-Y, Pu Y-S: Recommended initial

antimicrobial therapy for emphysematous pyelonephritis: 51 cases and 14-year experience of

a tertiary referral center. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016, 95:3573.

10.1097/MD.0000000000003573

10. Tienza A, Hevia M, Merino I, et al.: Case of emphysematous pyelonephritis in kidney allograft:

conservative treatment. Can Urol Assoc J. 2014, 8:256–259. 10.5489/cuaj.1555

2017 Wiesel et al. Cureus 9(8): e1612. DOI 10.7759/cureus.1612 5 of 5

You might also like

- The Psychiatric Interview - Daniel CarlatDocument473 pagesThe Psychiatric Interview - Daniel CarlatAntonio L Yang96% (26)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Republic of The Philippines Province of Surigao Del Sur Municipality of HinatuanDocument13 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Province of Surigao Del Sur Municipality of HinatuanGLORIFE RIVERALNo ratings yet

- VSP - Vision 01Document1 pageVSP - Vision 01api-252555369No ratings yet

- Sports Injuries - Prevention, Diagnosis, Treatment and Rehabilitation (PDFDrive) PDFDocument3,295 pagesSports Injuries - Prevention, Diagnosis, Treatment and Rehabilitation (PDFDrive) PDFRadu Urcan100% (2)

- Hospitals' EmailsDocument8 pagesHospitals' EmailsAkil eswarNo ratings yet

- NEW BUSINESS LIST OF ACCREDITED MEDICAL PROVIDERSDocument45 pagesNEW BUSINESS LIST OF ACCREDITED MEDICAL PROVIDERSEL0% (1)

- 1.8 Annex 4 - BOPIS DCF FORM 2-BDocument2 pages1.8 Annex 4 - BOPIS DCF FORM 2-Bgulp_burp75% (4)

- 2014 Article 85Document7 pages2014 Article 85taufikolingNo ratings yet

- 05-Vascular Complications Following Renal TransplantationGang-2009Document11 pages05-Vascular Complications Following Renal TransplantationGang-2009taufikolingNo ratings yet

- Tuberculosis Arthritis Epidemiology Diagnosis Treatment 2329 910X 2 131 PDFDocument7 pagesTuberculosis Arthritis Epidemiology Diagnosis Treatment 2329 910X 2 131 PDFtaufikolingNo ratings yet

- 2021 06 30 Coronavirus Covid 19 Vaccination in PregnancyDocument19 pages2021 06 30 Coronavirus Covid 19 Vaccination in PregnancyRahmayantiYuliaNo ratings yet

- CMR in Assessment of Cardiac Masses: Primary Benign TumorsDocument4 pagesCMR in Assessment of Cardiac Masses: Primary Benign TumorstaufikolingNo ratings yet

- Arthritis: Septic Arthritis and Tuberculosis ArthritisDocument10 pagesArthritis: Septic Arthritis and Tuberculosis Arthritistaufikoling100% (1)

- 11 FullDocument7 pages11 FulltaufikolingNo ratings yet

- 586 2012 Article 2331Document11 pages586 2012 Article 2331taufikolingNo ratings yet

- SJMCR 33194 197Document4 pagesSJMCR 33194 197taufikolingNo ratings yet

- Role of Diffusion-Weighted MRI in AcuteDocument7 pagesRole of Diffusion-Weighted MRI in AcutetaufikolingNo ratings yet

- Detection and Prediction of Osteoarthritis in KneeDocument32 pagesDetection and Prediction of Osteoarthritis in KneetaufikolingNo ratings yet

- Tuberculosis of The Knee: Licensee Pagepress, Italy Orthopedic Reviews 2009 1:E24 Doi:10.4081/Or.2009.E24Document3 pagesTuberculosis of The Knee: Licensee Pagepress, Italy Orthopedic Reviews 2009 1:E24 Doi:10.4081/Or.2009.E24RosaliaNo ratings yet

- A Rare Case of Pneumoureter Emphysematous Pyelitis Versus Emphysematous PyelonephritisDocument3 pagesA Rare Case of Pneumoureter Emphysematous Pyelitis Versus Emphysematous PyelonephritistaufikolingNo ratings yet

- 10 1055 S 0037 1605591 PDFDocument4 pages10 1055 S 0037 1605591 PDFtaufikolingNo ratings yet

- Rheumatoid Arthritis and Tuberculous Arthritis: Differentiating MRI FeaturesDocument7 pagesRheumatoid Arthritis and Tuberculous Arthritis: Differentiating MRI FeaturestaufikolingNo ratings yet

- Ubee Et al-2011-BJU InternationalDocument5 pagesUbee Et al-2011-BJU InternationaltaufikolingNo ratings yet

- A Rare Localization of Tuberculosis of The Wrist: The Scapholunate JointDocument4 pagesA Rare Localization of Tuberculosis of The Wrist: The Scapholunate JointtaufikolingNo ratings yet

- Skeletal TB. March 2016Document6 pagesSkeletal TB. March 2016taufikolingNo ratings yet

- GGGDocument10 pagesGGGtaufikolingNo ratings yet

- Case Report of Emphysematous PyelonephritisDocument4 pagesCase Report of Emphysematous PyelonephritistaufikolingNo ratings yet

- Sonographic Diagnosis of EmphysematousDocument1 pageSonographic Diagnosis of EmphysematoustaufikolingNo ratings yet

- Surface Aneurysmal Bone Cyst: Arn Van Royen, Filip Vanhoenacker and Jeoffrey de RoeckDocument3 pagesSurface Aneurysmal Bone Cyst: Arn Van Royen, Filip Vanhoenacker and Jeoffrey de RoecktaufikolingNo ratings yet

- Pyelitis EmfisematusDocument5 pagesPyelitis EmfisematustaufikolingNo ratings yet

- Fibrous Dysplasia Vs Adamantinoma of The TibiaDocument7 pagesFibrous Dysplasia Vs Adamantinoma of The TibiataufikolingNo ratings yet

- DWI's Role in Characterizing Bone TumorsDocument9 pagesDWI's Role in Characterizing Bone TumorstaufikolingNo ratings yet

- Advances in Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Musculoskeletal TumoursDocument9 pagesAdvances in Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Musculoskeletal TumourstaufikolingNo ratings yet

- DOI: 10.1515/jbcr-2015-0170: Case ReportDocument4 pagesDOI: 10.1515/jbcr-2015-0170: Case ReporttaufikolingNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Pathology: Adamantinoma: A Clinicopathological Review and UpdateDocument11 pagesDiagnostic Pathology: Adamantinoma: A Clinicopathological Review and UpdateEta Calvin ObenNo ratings yet

- DWI's Role in Characterizing Bone TumorsDocument9 pagesDWI's Role in Characterizing Bone TumorstaufikolingNo ratings yet

- Craniopharyngioma Full LectureDocument10 pagesCraniopharyngioma Full LecturetaufikolingNo ratings yet

- Childhood Cognitive Development StagesDocument5 pagesChildhood Cognitive Development Stagesjohn mwambuNo ratings yet

- NHS FPX 6008 Assessment 4 Lobbying for ChangeDocument6 pagesNHS FPX 6008 Assessment 4 Lobbying for Changejoohnsmith070No ratings yet

- Institutional Minimum Req Off-Street DavidDocument2 pagesInstitutional Minimum Req Off-Street DavidMikealla DavidNo ratings yet

- Donning and Doffing PPEDocument4 pagesDonning and Doffing PPEShang DimolNo ratings yet

- Quitor, Marjorie M. Team Sports BSHM 2C: This Signals The Start of The Game by Putting The Ball in PlayDocument4 pagesQuitor, Marjorie M. Team Sports BSHM 2C: This Signals The Start of The Game by Putting The Ball in PlayMath TangikNo ratings yet

- De HSG Tinh 2021Document17 pagesDe HSG Tinh 2021Phuong NguyenNo ratings yet

- Summary, Conclusion, Implications and RecommendationDocument6 pagesSummary, Conclusion, Implications and RecommendationJubert IlosoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 11 Hormonal Coordination: 165 MinutesDocument60 pagesChapter 11 Hormonal Coordination: 165 MinutesAviBreezeNo ratings yet

- 21st Century Communication - Vocabulary List - Unit 5Document1 page21st Century Communication - Vocabulary List - Unit 5蔡青紘No ratings yet

- Geriatric PsychiatryDocument91 pagesGeriatric PsychiatryVipindeep SandhuNo ratings yet

- Rape in Romance FictionDocument14 pagesRape in Romance Fictioncnkwanga_jollyNo ratings yet

- Tle 18 Module 8Document12 pagesTle 18 Module 8Justine Lyn FernandezNo ratings yet

- Vocabulary UNIT - 3 - : - Free Times - GRAMMAR: - Can/Can T For Ability, Like + Verb/nounDocument4 pagesVocabulary UNIT - 3 - : - Free Times - GRAMMAR: - Can/Can T For Ability, Like + Verb/nounRicardo JimenezNo ratings yet

- Manikins Proposed List For Skill LabDocument3 pagesManikins Proposed List For Skill LabNaren KNo ratings yet

- Outcome Predictors in Acute Surgical Admissions For Lower Gastrointestinal BleedingDocument1 pageOutcome Predictors in Acute Surgical Admissions For Lower Gastrointestinal BleedingEd FitzgeraldNo ratings yet

- Why Texting Is Better Than TalkingDocument4 pagesWhy Texting Is Better Than TalkingjhgfhjgkgkNo ratings yet

- List of Fellows (Name-Wise) Upto 2016Document165 pagesList of Fellows (Name-Wise) Upto 2016Rakesh VermaNo ratings yet

- De Thi Tuyen Sinh Lop 10 THPT 20162017Document5 pagesDe Thi Tuyen Sinh Lop 10 THPT 20162017Huy HaNo ratings yet

- 6 Min English Bucket ListsDocument5 pages6 Min English Bucket ListssNo ratings yet

- Certification Exam Candidate Handbook PDFDocument46 pagesCertification Exam Candidate Handbook PDFvetrijNo ratings yet

- MARIELLE CHUA - (Template) SOAPIE CaseletDocument9 pagesMARIELLE CHUA - (Template) SOAPIE CaseletMarielle Chua100% (1)

- Full Download Test Bank For Statistics For Managers Using Microsoft Excel 7 e 7th Edition 0133130800 PDF Full ChapterDocument36 pagesFull Download Test Bank For Statistics For Managers Using Microsoft Excel 7 e 7th Edition 0133130800 PDF Full Chapterostosiscordelle.eps0z7100% (18)

- (Journal of Neurosurgery - Spine) Radiographic and Clinical Evaluation of Free-Hand Placement of C-2 Pedicle ScrewsDocument8 pages(Journal of Neurosurgery - Spine) Radiographic and Clinical Evaluation of Free-Hand Placement of C-2 Pedicle ScrewsVeronica Mtz ZNo ratings yet