Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Jenkinsetal - TobaccoUseInVietnam

Uploaded by

NKDOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Jenkinsetal - TobaccoUseInVietnam

Uploaded by

NKDCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/14048625

Tobacco use in Vietnam. Prevalence, predictors, and the role of the

transnational tobacco corporations

Article in JAMA The Journal of the American Medical Association · July 1997

DOI: 10.1001/jama.277.21.1726 · Source: PubMed

CITATIONS READS

78 459

8 authors, including:

Sarah Bales Susan L Stewart

National University of Singapore University of California, Davis

14 PUBLICATIONS 341 CITATIONS 217 PUBLICATIONS 6,709 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Medi-Cal Incentives to Quit Smoking View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Susan L Stewart on 10 July 2014.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Tobacco Use in Vietnam

Prevalence, Predictors, and the Role of the Transnational

Tobacco Corporations

Christopher N. H. Jenkins, MA, MPH; Pham Xuan Dai; Do Hong Ngoc, MD; Hoang Van Kinh; Truong Trong Hoang, MD;

Sarah Bales, MA; Susan Stewart, PhD; Stephen J. McPhee, MD

Objective.\p=m-\To describe tobacco use in Vietnam and the WORLDWIDE, cigarette smoking causes 3 million deaths

impact of transnational tobacco corporations there. annually, with two thirds of these deaths occurring in the

Desig.\p=m-\In

cities, a multistage cluster design; in com- developed world.1 Cigarette smoking is an important risk

munes, a systematic sample design, using face-to-face factor in the development of cancer, lung disease, coronary

interviews in all sites. heart disease, stroke, and birth defects and by the year 2020

Set ing.\p=m-\Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City, and 2 rural communes is expected to kill more people than any single disease.2"4 As

in Vietnam. smoking declines in the West, per capita cigarette consump¬

Particpants.\p=m-\Random samples totaling 2004 men and tion rates are growing in the developing world.5 Unless steps

women aged 18 years or older. are taken to reduce smoking rates, it is anticipated that in the

Main Outcome Measures.\p=m-\Prevalenc and correlates of year 2025 the worldwide death toll due to smoking will climb

tobacco smoking, amount and duration of smoking, age at ini- to 10 million per year, with 7 million of those deaths occurring

tiation, quitting behavior, knowledge of health hazards of and in the developing world.1

attitudes toward smoking, and cigarette brand smoked, pre- In the Asian countries of the Pacific Rim, the prevalence

ferred, and recognized as most widely advertised. of cigarette smoking is uniformly high among men. Among

Results.\p=m-\Smoking prevalence among men (n=970) was women, smoking rates are low. In China, for example, 61% of

72.8% and 4.3% among women (n=1031). Male smokers men and 7% of women smoke; in Indonesia, 53% of men and

had smoked a mean of 15.5 years; the median age at initia- 4% of women smoke.5·6 In comparison, in the United States

tion was 19.5 years. Among male smokers, 16% smoked 26% of men and 24% of women smoke.7 With declining ciga¬

non-Vietnamese cigarettes. More than twice as many (38%), rette consumption in their domestic markets, transnational

however, said that they would prefer to smoke a non- tobacco corporations (primarily Philip Morris Companies and

Vietnamese brand if they could afford the cost. Among those RJR Nabisco Holdings Corporation in the United States and

who recalled any cigarette advertising (38%), 71% recalled a B.A.T. Industries PLC [British-American Tobacco] in the

non-Vietnamese brand as the most commonly advertised. United Kingdom) are seeking new markets overseas through

Male smokers who were significantly more likely to smoke exports, acquisitions, and joint ventures.8 In recent years, the

non-Vietnamese brands lived in the south, were engaged in US Trade Representative has forced open Asian markets to

blue collar or business/service occupations, earned higher sales of US cigarettes with the threat of retaliatory trade

incomes, and lived in urban areas. sanctions.8,9 Tobacco corporation revenues from international

Conclusions.\p=m-\Vietnam has the highest reported male tobacco operations regularly outpace those from domestic

smoking prevalence rate in the world. Unless forceful steps sales.1012 In the United States, cigarette exports have grown

are taken to reduce smoking among men and prevent the 260% in the 10 years from 1986 to 1996, and 40% of US tobacco

uptake of smoking by youth and women, Vietnam will face a exports are sold in Asia.13

tremendous health and economic burden in the near future. Reliable data for cigarette smoking prevalence in Vietnam

Implementation of a comprehensive national tobacco control are not available. Vietnam, a country with a population of 72.5

campaign together with international regulation will be the million, ranks as one of the poorest countries in the world with

keys to the eradication of the tobacco epidemic in Vietnam an annual per capita income of $200.14 However, recent market-

and throughout the developing world. oriented economic reforms have stimulated annual growth

JAMA. 1997:277:1726-1731 rates of 8% or more.15 The tobacco industry has proven to be

From Suc Khoe La Vang! (Health Is Gold!), Vietnamese Community Health Pro-

profitable for the Vietnamese government: in 1994, corporate

motion Project, Division of General Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine, Uni- and excise taxes on tobacco accounted for 3.2% ($110 million)

versity of California, San Francisco (Mr Jenkins and Dr McPhee); National Center for of the national budget.16 Tobacco provides employment for

Human and Social Sciences, Institute of Sociology, Hanoi, Vietnam (Mr Pham);

Health Information and Education Center, Ho Chi Minh City Department of Health, almost 15 000 workers in cigarette production and more than

Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam (Drs Do and Truong); Hanoi Trade College (Mr Hoang); 100000 farmers in tobacco cultivation, accounting for less

Department of Economics, University of California, Berkeley (Ms Bales); Northern than half of 1% of both the industrial and agricultural labor

California Cancer Center, Union City (Dr Stewart); and the Institute for Health Policy

Studies, University of California, San Francisco (Dr McPhee). forces. Although import of non-Vietnamese cigarettes has

Presented in part at the fifth conference of the Asian Pacific Association for the

Control of Tobacco, Chiang Mai, Thailand, November 23, 1995. been banned since 1990, illegal imports are estimated to fill

Corresponding author: Christopher N. H. Jenkins, MA, MPH, Suc Khoe La Vang! 10% of the domestic demand. In addition, Vietnam relies on

(Health Is Gold!), Vietnamese Community Health Promotion Project, Division of Gen- legally imported tobacco leaf to fulfill 25% to 30% of its ciga¬

eral Internal Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, 44 Montgomery, Suite

850, San Francisco, CA 94104 (e-mail: chrisj@itsa.ucsf.edu). rette production needs.17 In an attempt to stem the flow of

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ by a University of California - Davis User on 07/10/2014

illegal imports and increase tobacco tax revenues, in 1994 pilot tested and modified to accommodate differences in re¬

(shortly after the United States lifted its trade embargo gional dialects.

against Vietnam) the Ministry of Trade issued licenses to 3 Subjects were asked if they had ever smoked tobacco; if,

transnational tobacco corporations (Rothman's of Pall Mall, during the prior week, they had smoked tobacco; and if, even

Philip Morris, and B.A.T.) to produce non-Vietnamese-brand though they had not smoked in the last week, they sometimes

cigarettes in Vietnam in joint ventures with the Vietnam smoked tobacco in social situations. Respondents were clas¬

National Tobacco Corporation, a state-managed tobacco en¬ sified as current smokers if they responded yes to the first

terprise.18·19 and second questions or to the first and third questions, as

In this article, we present the results of a survey that former smokers if they responded yes to the first and no to

describes tobacco use in Vietnam, knowledge of its hazards the second and third questions, and as never smokers if they

and attitudes about .its use, and the impact transnational responded no to the first question. The age at which smokers

tobacco corporations are having on tobacco use in Vietnam. started to smoke was calculated by subtracting number of

years smoked from age. We assumed that 4 water-pipe wads

METHODS were equivalent to 1 cigarette. Per capita income was cal¬

We conducted face-to-face interviews with men and women culated by dividing household income by household size. Viet¬

aged 18 years or older in 2 cities, Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, namese dong were converted to US dollars at the rate of

and 2 rural communes, Phu Linh in the north and Phuoc Vinh 11000 dong per dollar.

An in the south, each approximately 50 km distant from their Data analysis was performed with SUDAAN, a statistical

respective urban centers. The survey sites were chosen be¬ program for the analysis of complex survey data.20 After

cause they are broadly representative of the country (Viet¬ pooling data from the 4 sites, data were weighted to national

nam's 2 largest cities, 1 in the north and 1 in the south, and population distributions by age, sex, and urban or rural sta¬

2 typical wet-rice agricultural communities). During the fall tus14 and to account for unequal selection probabilities owing

of 1995, a total of 2004 interviews were conducted, approxi¬ to differences in household size. In preliminary analyses of

mately 500 in each of the 4 sites. In cities, respondents were sociodemographic characteristics and smoking behaviors, we

selected using a multistage cluster sampling design. Both used t tests to test the significance of differences in means and

cities are administratively divided into wards, which are fur¬ 2 tests to test the significance of differences in proportions.

ther subdivided into blocks. In each city, 25 wards were We then performed multiple logistic regression analyses to

selected in a manner which ensured that the probability of a control simultaneously for any differences in sociodemographic

ward being selected was proportional to its size. Using a factors that might have accounted for differences in smoking

computer-generated random number, we chose 1 block in behaviors. The regressions were performed to identify vari¬

each selected ward. For each selected block, sampling frames ables among men significantly associated with current smok¬

were formed by obtaining lists from block captains of all ing, smoking non-Vietnamese-brand cigarettes, and prefer¬

households living in the block. Since each block had approxi¬ ring non-Vietnamese-brand cigarettes.

mately 100 households, we used a sampling interval of 5 to RESULTS

select a systematic sample of 20 households in each block.

In rural communes, households were randomly selected Of the 2226 persons selected for interview, 214 were con¬

from the complete list of households living in the commune sidered ineligible due to illness (33), persistent absence (167),

provided by the commune People's Committee. The total or having moved away (14). Of the remaining 2012 persons,

number of households in each commune was divided by 500 2004 agreed to be interviewed, yielding a response rate of

in order to obtain a sampling interval, which was then used 99.6%. In the following analyses, 3 cases were dipped be¬

to select a systematic sample of households for interview. In cause of missing age data.

both urban and rural sites, after enumerating all eligible Reflecting national distributions for age, sex, and urban or

adults in the household, we selected the respondent using a rural residence, the mean age of the participants was 38.3

random-numbers table and conducted the interview. If the years (range, 18-92 years), women made up 51.5% of the

selected respondent was not available after at least 3 sample, and 78.1% of participants lived in rural areas. A

attempts within 3 days, we interviewed the next oldest quarter of the participants were single, while the rest were

household member. University students and community married or formerly married. Reported occupations were

health workers, trained by the investigators, served as classified as peasant (41.9%), blue collar (17.2%), business/

interviewers. service (7.5%), white collar (7.9%), or not in the labor force

Survey items included sociodemographic information (age, (25.5%). Participants reported means of 8.0 years of education

sex, occupation, years of education, marital status, income), (SE, 0.1) and per capita income per month of $18.32 (SE,

smoking behavior (smoking status, number of years smoked, $0.60).

type and amount of tobacco smoked per day, brand of ciga¬ More than a third of the respondents reported that they

rette), expenditures on tobacco, quitting behavior and atti¬ were current smokers (Table 1). Smoking prevalence was

tudes toward quitting, and knowledge of the health hazards much higher among men than among women. Among men,

associated with smoking. Since it is expected that men should smoking was related to age (P<.001), peaking in the age

smoke or be offered cigarettes in many social situations, we group of 35 to 44 years (84.1%) with younger men and older

asked if respondents agreed with these social norms. Ciga¬ men smoking at lower rates. Men belonging to each of the

rette smokers were asked what brand of cigarette they would following categories were more likely to smoke: peasant class,

prefer to smoke if they had more money. Among those who living in a rural site, having fewer years of education, being

recalled any cigarette advertising, we asked what brand they married, or having lower incomes. None of these associations

recalled being most advertised. The survey instrument was were statistically significant, however. Among women, there

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ by a University of California - Davis User on 07/10/2014

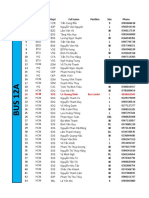

Table 1.—Smoking Prevalence for the Total Population and by Sex, All Forms Table 2.—Cigarette Brand Consumption, Preference, Recognition, and Cost*

of Tobacco, Among All Survey Respondents, Vietnam

Brand Now Brand Prefer Brand Most

Total, % (95% CI)* Men, Smoking, % to Smoke, % Advertised,% Price per

% (95% CI) Women, % (95% CI)

Smoking Status (N=2001)_(n=970)_(n=1031) Brand_(n=664) (n=619)_(n=742) Pack, US $

Current smoker 36.0(33.1-38.9) 72.8(68.5-77.1) 4.3(2.6-5.9) Du Lieh_509_309_5_7_0.18

Former smoker 5.2 (3.2-7.2)_9.9(7.5-12.2)_1.2(0.3-2.1) Vinataba_104_14J_137_0.55

Never smoker 58.8 (55.9-61.7) 17.3 (13.3-21.3) 94.5 (92.7-96.4) Jet_103_21J3_3J3_0.50

*CI indicates confidence interval.

555_2$_104_18 _1.05

Dunhill_1J_22_35_1_0.98

Marlboro_OÍS_22_9 _1.02

was arelationship between smoking and age (P=.002). Smok¬ Other

ing was rare among women younger than age 45 years, but non-Vietnamese 1.0 1.4 4.9

Other

smoking prevalence rates increased moderately among older Vietnamese 23.0 16.9 10.0

women, peaking in the group aged 65 years or older at 17.9%.

Women who were significantly more likely to be smokers *Brand now smoked and preferred brand are reported for all cigarette smokers,

men and women. Brand most widely advertised Is reported for all respondents who

were not in the labor force (P=.01), had fewer than 6 years recalled any cigarette advertising, regardless of smoking status. Jet, 555, Dunhill, and

of education (P<.001), and were widowed (P<.001); there Marlboro are non-Vietnamese brands produced domestically. Prices for packs of 20

cigarettes were determined by calculating the average of prices obtained after sam¬

was no significant association, however, between smoking pling at 3 different vendors in Hanoi at the time of the survey. Ellipses indicate data

not applicable.

and urban or rural site of residence or household income.

Except where indicated, the following results presented are

for men, who accounted for 95% of the current smokers. were significantly more likely than men to acknowledge that

Most smokers smoked manufactured cigarettes (64.7%). both smoking (P=.004) and environmental tobacco smoke

Another 8.9% smoked loose tobacco rolled into a cigarette, (P=.008) harm health. For all 3 questions, nonsmokers were

14.9% smoked loose tobacco in a water pipe, and 11.4% more likely than smokers to acknowledge the health hazards

reported smoking both manufactured cigarettes and water of smoking (P<.001).

pipes. The vast majority of water-pipe smokers (92.6%) were Among all respondents, most agreed that cigarettes should

found in the rural survey site in the northern part of the not be smoked during public meetings (80.9%). However,

country. slightly more than half felt that cigarettes should be smoked

Those who smoked cigarettes (manufactured or rolled, at weddings or funerals (51.81%), guests in the home should

n=526) smoked of 9.6 cigarettes per day (SE, 0.4);

a mean be invited to smoke (54.9%), and when meeting friends, one

6.7% reported smoking less than 1 cigarette per day and may should offer cigarettes (51.6%). In all situations, however,

be considered occasional smokers. Although it might be ex¬ men were significantly more likely than women to feel that

pected that consumption would increase with income, there cigarettes should be smoked or offered (P<.001). Two thirds

was no relationship between number of cigarettes smoked of smokers, male and female (66.6%), agreed that their smok¬

per day and income. Among those who smoked water pipes ing bothered others; 62.1% of all respondents said they were

exclusively, the mean number of tobacco wads smoked per bothered when others smoked.

day was 17.8 (SE, 1.3), the equivalent of about 4.5 cigarettes. Most (62.3%) did not recall seeing or reading any cigarette

Current smokers (all forms of tobacco) reported smoking advertising (reflecting, perhaps, the fact that nearly all direct

a mean of 15.5 years (SE, 0.7). The median age at smoking cigarette advertising is banned in Vietnam). Among the 835

initiation was 19.5 years. Younger age cohorts generally respondents who did, men (41.2%) were more likely to recall

started smoking at younger ages: among those aged 25 to 34 advertising than women (22.7%), current smokers (40.3%)

years at the time of the survey, 78% had started smoking by recalled more than nonsmokers (26.1%), and those living in

the time they reached age 24 years. However, among those cities (65.0%) recalled more than those living in rural areas

aged 35 to 44 years, only 65% had started smoking by age 24 (21.6%). Rates of recall of cigarette advertising declined with

years. In the group aged 45 to 54 years, the proportion fell to increasing age (P=.005), but rose with increasing income

44%, but rose somewhat among those aged 55 years or older level (P<.001) and years of education (P<.001). Among oc¬

to 51%. cupational groups, recall rates were highest among those in

Among current smokers, 60.6% reported wanting to quit, white collar (51.0%) or business and service occupations

but 50.7% said they thought it would be difficult to do so. (50.6%); only 21.8% of peasants recalled advertising. Those

Fewer than half of current smokers (43.7%) reported ever not yet married were more likely to recall advertising than

trying to quit. Their mean number of attempts to quit was 2.1 those who had ever been married (P<.001).

(SE, 0.1). There were 121 former smokers who had quit The cigarette brands most commonly smoked and most

successfully (11.9% of ever smokers). Former smokers' most preferred were domestic brands (Table 2). Non-Vietnamese

frequently offered reasons for quitting were for their own brands (Jet, 555, Dunhill, Marlboro, and other brands) ac¬

health (75.8%) or the health of their family (5.2%). Another counted for only 16% of brands currently smoked. More than

7.4% reported quitting for economic reasons; only 0.8% said twice as many (38%) said that they would prefer to smoke a

they quit because of government restrictions on smoking. non-Vietnamese brand if they could afford the cost. Among

Among all respondents, levels of knowledge about the harm¬ those who recalled cigarette advertising, non-Vietnamese

ful effects of smoking on health were high. Nearly all agreed brands were recalled by a wide majority (71%) as the most

that smoking harmed health (87.2%), smokers died at a younger commonly advertised. The brand which captured the great¬

age than nonsmokers (80.6%), and environmental tobacco est percentage of the market (50.9%), domestically produced

smoke harmed health (78.9%). Although men and women did Du Lieh (Tourist), was only recognized by 5.7% as the most

not differ in their response to the second question, women widely advertised brand.

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ by a University of California - Davis User on 07/10/2014

Table 3.—Multiple Logistic Regression Analysis of Predictors of Current Smoking (All Forms of Tobacco), Smoking Non-Vietnamese-Brand Cigarettes, and Pre¬

ferring Non-Vietnamese-Brand Cigarettes, Vietnam, Men*

Current Smoker, Smokes Non-Vietnamese Brand, Prefers Non-Vietnamese Brand,

OR (95% CI)* (n=970) OR (95% CI) (n=533) OR (95% CI) (n=533)

ge, y

18-24 1.6(0.6-4.5) 7.0(1.0-50.4) 14.9(4.1-53.9)

25-34 3.8(1.5-9.3) 5.0 (0.8-30.0) 14.2(4.0-50.1)

35-44 4.9(2.0-12.0) 1.7(0.3-10.5) 7.5(2.1-26.2)

45-54 3.1 (1.3-7.6) 4.2 (0.5-32.6) 6.3(1.8-21.7)

55-64 2.4(1.0-5.7) 0.8(0.1-5.4) 2.1 (0.5-9.9)

ï65 Referent Referent Referent

Occupation

Not in labor force 0.7(0.3-1.5) 3.9 (0.6-25.8) 2.3 (0.8-6.5)

Blue collar 0.8(0.4-1.6) 10.0(2.5-40.5) 1.8(0.8-4.0)

Business/service 0.9 (0.3-2.3) 23.2(3.3-164.1) 2.2 (0.7-7.5)

White collar 0.4 (0.2-0.9) 3.9 (0.5-29.7) 1.2(0.4-3.1)

Peasant Referent Referent Referent

Residence

Urban 1.1 (0.6-1.8) 1(3.6-21.9) 3.1 (1.5-6.6)

Rural Referent Referent Referent

Region

South 0.7(0.4-1.3) 256.8(40.4-1633.1) 6.3(2.9-13.5)

North Referent Referent Referent

Education, y

0-5 3.4(1.2-9.4) 0.1 (0.0-1.2) 0.1 (0.0-0.3)

6-8 2.3(1.0-5.3) 0.3 (0.0-2.3) 0.2(0.1-0.7)

9-11 2.5(1.1-5.9) 0.3(0.1-2.3) 0.3(0.1-1.1)

12-15 2.5(1.1-5.4) 0.4(0.1-2.1) 0.3(0.1-1.1)

:16 Referent Referent Referent

Per capita monthly income, dongt

Refused to answer 1.2(0.6-2.5) 0.3(0.1-1.2) 1.7(0.7-4.2)

8000-112 000 1.0(0.5-2.1) 0.1 (0.0-0.8) 1.1 (0.4-3.0)

113000-179000 0.6(0.4-1.2) 0.1 (0.0-0.5) 0.9 (0.4-2.2)

£180 000 Referent Referent Referent

Marital status

Married 1.2(0.6-2.2) 0.5(0.2-1.2) 0.6(0.3-1.2)

Not married Referent Referent Referent

*The analysis of the current-smoker category Is based on all men and includes all forms of tobacco; analyses of the "smokes non-Vietnamese brand" and "prefers

non-Vietnamese brand" categories are based on all male cigarette smokers of manufactured and rolled cigarettes. OR indicates odds ratio; and CI, confidence interval.

tTo convert dong to US dollars, divide by 11 000.

Domestic cigarette brands ranged in price from $0.14 to business/service or blue collar occupations and living in the

$0.55 per pack. Non-Vietnamese brands were considerably urban survey sites. Those with lower incomes were less likely

more expensive, ranging in price from $0.55 to $1.05 per pack. to smoke non-Vietnamese brands. In the final regression, the

Loose tobacco for water pipes cost less than manufactured strongest predictor of preferring to smoke non-Vietnamese

cigarettes. A 5-g packet, enough for 20 water-pipe wads, cost brands was younger age. The OR of preferring non-Viet¬

only $0.05. Loose tobacco and the use of a communal water namese brands was 14.9 (95% CI, 4.1-53.9) for those aged 18

pipe are commonly offered free of charge to patrons of res¬ to 24 years and 14.2 (95% CI, 4.0-50.1) for those aged 25 to 34

taurants, noodle stands, and coffee shops in the north. years. Other predictors included being aged 35 to 44 years or

On average, cigarette smokers spent $49.05 on cigarettes aged 45 to 54 years and being from an urban or southern

each year. This amount was lVà times their annual per capita survey site. Those who were less educated, with fewer than

household expense for education ($30.82), 5 times their annual 9 years of education, were less likely to prefer non-Vietnam¬

per capita household expense for health care ($9.65), and about ese brands.

a third of their annual per capita household expense for food

COMMENT

($143.27). As might be expected, the amount of money spent

on cigarettes rose significantly with a rise in income (P<.001) Compared with smoking prevalence rates reported by the

and with the number of cigarettes smoked per day (P<.001). World Health Organization (WHO) for 87 countries for which

In the multiple logistic regression analyses (Table 3), we national data are available,5 Vietnam has the highest smoking

found among men, those more likely to smoke were aged from prevalence rate for men in the world. Smoking rates among

25 to 54 years (age groups 25-34, 35-44, and 45-54 years) and Vietnamese women, on the other hand, are among the world's

had less than a college education. White collar workers were lowest. We should caution that more reliable national smok¬

less likely to smoke. In the second regression, living in the ing prevalence data might have been obtained from a national

southern survey sites was overwhelmingly associated with probability sample. However, as noted above, survey sites

smoking non-Vietnamese-brand cigarettes (odds ratio [OR], were chosen because they are broadly representative of the

256.8; 95% confidence interval [CI], 40.4-1633.1). Other pre¬ country, and the data were weighted to reflect national popu¬

dictors of smoking non-Vietnamese brands were working in lation distributions.

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ by a University of California - Davis User on 07/10/2014

Based on the smoking prevalence rates reported here and reported for smoking in other social situations is testimony

Vietnamese population data for 1994, there are approximately to the widespread social acceptability of smoking and its

15.5 million smokers in Vietnam. Reports from developed coun¬ integral role in the social culture of Vietnam.

tries indicate that about half of all lifetime smokers will die from Without prior smoking data, it is not possible to know the

tobacco-related diseases; half of these deaths will be prema¬ direction of trends in Vietnam. Others have demonstrated

ture, occurring between the ages of 35 and 69 years.1 Using this that tobacco consumption in the less-developed countries is

evidence, we can project that approximately 7 325 000 Viet¬ significantly related to prosperity.22 It can be expected that

namese (about 10% of the population) will die from tobacco use as disposable income increases in Vietnam, smoking will in¬

and that about 3 660 000 of these persons will die prematurely. crease. Our own data show a trend toward younger age at

Furthermore, if children start to smoke at the rates their par¬ initiation. If this trend continues, rates among youth will

ents smoke, more than 5 million of those younger than 15 years increase in the future.

in 1995 will die prematurely from smoking-related diseases. Experience in other Asian countries has demonstrated that

Vietnamese male smokers smoked fewer cigarettes (9.6 the entry of transnational tobacco corporations and their

per day) than the mean number reported worldwide for both aggressive marketing increase tobacco consumption.23-25 In

more developed countries (22 per day) and less developed the data we report, the rate of smoking non-Vietnamese-

countries (14 per day).5 In addition, they started smoking brand cigarettes in Vietnam was relatively low. However,

when they were somewhat older than their counterparts in future trends may be discerned in the higher rate of smokers

other parts of the world, where the median age at initiation expressing a desire to smoke these brands if they could afford

is often younger than 15 years.5 An older age at initiation them and the overwhelming recognition commanded by non-

combined with a life expectancy of only 60 years for men14 Vietnamese brands in the advertising market. Non-Viet¬

means Vietnamese smokers are exposed to fewer years of namese-brand cigarettes have established their largest mar¬

smoking than smokers in more developed countries where life ket niche in the urban south, perhaps a legacy of taste

expectancy is longer. These factors may mean that the tobacco- preferences established during the US presence there before

related mortality estimates for Vietnam above are overstated. 1975. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that it was the younger

Even if we reduce these estimates by half, however, they still urban men who were more likely to notice tobacco advertis¬

portend an ominous future of tobacco-related death, disabil¬ ing and want to smoke non-Vietnamese brands if they could

ity, and associated lost productivity and health care costs. afford them. It is these segments of the population that have

Furthermore, if age at smoking initiation decreases and life been most successfully targeted by the transnational tobacco

expectancy increases, we can expect that the toll on human corporations to date.

life taken by tobacco will be greater in the future. Currently, social norms preclude younger women from

Contributing to the public health toll on cigarette smokers smoking. In younger cohorts, smoking is widely considered

and their families is the proportion of a smoker's income that unfeminine, unattractive to the opposite sex, and a sign of

is spent on cigarettes. Money spent on cigarettes is money not loose morals.26 Among older women, these taboos fall away.

spent to meet vital, life-sustaining needs. The mean expen¬ Although the female smoking rate is now low, especially

diture for cigarettes could have bought 136 kg of rice at 1995 among younger women, this rate may rise as women enter

prices ($0.36/kg), nearly enough to feed 1 person for 1 year. the industrial workforce, as their incomes rise, and, espe¬

Although state subsidies for food, health care, and education cially, if transnational tobacco corporation advertising tar¬

were common before 1989, the policy Dot Mot (Renovation) gets women more successfully.

and the ending of financial support from the former Soviet Although cigarette advertising has been banned in the

Union have led to severe cutbacks in recent years.15 By 1995, print, electronic, and outdoor media in Vietnam, the trans¬

for example, consumers paid for more than 80% of their own national tobacco corporations promote their products aggres¬

health care expenses.21 sively through point-of-purchase advertising, sponsorship of

Water-pipe smoking is a popular custom among rural men, sports and cultural events, and the provision of logo-bearing

especially in the north. The relative health effects of water- baseball caps, T-shirts, umbrellas, and other merchandise in

pipe smoking, compared with cigarette smoking, are unknown. exchange for empty cigarette packs. Young women are hired

In cigarette equivalents, the quantity of tobacco smoked per to distribute free samples in restaurants, hotels, karaoke

day by water-pipe smokers is less than half that smoked by bars, and sports arenas. The manufacturers of Dunhill ciga¬

cigarette smokers. This fact alone may mean that water-pipe rettes provide $470000 in aid annually to develop profes¬

smoking is less hazardous to health, but this issue bears sional soccer in Vietnam.27 In addition, Dunhill sponsors tele¬

further research. vision broadcasts of Saturday night soccer, slipping through

In recent years, smoking cigarettes has been an integral an advertising ban by showing only its logo with the slogan

part of government meetings and commercial negotiations at "The Best Taste in the World," without showing the actual

all levels. Cigarette packs or cartons are often offered as cigarette itself.

"gifts" to higher authorities in exchange for favors. Accord¬ Typically, as non-Vietnamese cigarettes garner more of

ing to a popular maxim about gaining approval from a gov¬ the market share in developing countries, domestic tobacco

ernment official, "If you offer a cheap, domestic brand you will companies intensify their marketing to remain competitive.9,25

be greeted with silence; if you offer 555 brand, you will get Entry of the transnationals into the Vietnamese tobacco mar¬

whatever you want." The large number of respondents who ket, for example, has prompted domestic manufacturers to

agreed that cigarettes should not be smoked during meetings develop new copycat brands. One state-owned tobacco fac¬

were likely reflecting government regulations issued in 1995 tory has come out with 333 brand cigarettes with gold foil

banning such activity. It remains to be seen to what degree packaging, which carefully imitates British-American Tobac¬

these regulations will be enforced. The great level of support co's 555; another new domestic brand, Boy Boy Boy, features

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ by a University of California - Davis User on 07/10/2014

packaging with images of a Vietnamese Marlboro man, com¬ hensive national tobacco control campaign together with in¬

plete with cowboy hat. ternational regulation as outlined by WHO will be the keys

Special attention should be focused on the transnational to the eradication of the tobacco epidemic in Vietnam and

tobacco corporations in order to monitor and control their throughout the developing world.

activities. Exporting countries, which have made admirable This research was supported by the University of California Pacific Rim

progress in recent years in controlling tobacco at home, should Research Program.

take steps to ensure that they do not permit the export of the We would like to thank Judith Mackay, FRCP, Asian Consultancy on To¬

bacco Control, Hong Kong, for her helpful review of the manuscript.

tobacco epidemic to countries such as Vietnam or the rest of

the developing world. In the exporting countries, a combi¬ 1. Peto R, Lopez AD, Boreham J, Thun M, Health C Jr. Mortality from Smoking in

Developed Countries, 1950-2000: Indirect Estimates From National Vitality Statis-

nation of legislative initiatives and consumer action is needed. tics. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 1994.

2. US Dept of Health and Human Services. Reducing the Health Consequences of

In the United States, for example, Congress can restrict the

Smoking: 25 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC:

activities of the US trade representative in promoting US US Dept of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease

tobacco interests overseas, place a surtax on corporate prof¬ Control, Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office of

Smoking and Health; 1989. DHHS publication CDC 89-8411.

its derived from international tobacco sales, revoke corporate 3. Wald NJ, Hackshaw AK. Cigarette smoking: an epidemiological overview. Br Med

Bull. 1996;52:3-11.

tax exemptions for cigarette advertising expenses of over¬ 4. Murray CLJ, Lopez AD, eds. The Global Burden of Disease: A Comprehensive

seas operations, and force tobacco corporations to observe Assessment of Mortality and Disability From Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors

in 1990 and Projected to 2020. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard School of Public Health,

abroad the more restrictive sales, advertising, and promotion World Health Organization, and World Bank; 1996.

controls which apply in their domestic markets. Consumers 5. WHO (World Health Organization) Programme on Tobacco or Health. Tobacco

consumption. Tobacco Alert [serial online]. World No Tobaco Day (May 31), 1996:7\x=req-\

can organize boycotts of tobacco conglomerates, refusing to 12. Available at: http://www.who.ch/programmes/psa/toh/Alert/apr96/index.html.

Accessed April 24, 1997.

buy nontobacco products controlled by the parent corpora¬ 6. Gong YL, Koplan JP, Feng W, Chen CHC, Zheng P, Harris JR. Cigarette smok-

tion. Stockholders, particularly institutional stockholders such ing in China: prevalence, characteristics, and attitudes in Minhang District. JAMA.

as university endowments or retirement plans, can divest

1995;274:1232-1234.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette smoking among adults\p=m-\

their portfolios of tobacco stock holdings. In the past, boy¬ United States, 1994. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ. 1996;45:588-590.

8. Frankel G. Big tobacco's global reach: US-aided cigarette firms in conquests

cotts and divestment have been used effectively to stop the across Asia. Washington Post. November 19, 1996:A1.

9. Chen TTL, Winder AE. The opium wars revisited as US forces tobacco exports

marketing of infant formula in the developing world and to in Asia. Am J Public Health. 1990;80:659-662.

weaken the apartheid regime in South Africa. 10. Collins G. RJR Nabisco holdings posts gain in 4th quarter earnings. New York

Times. January 29, 1997:D4.

On an international level, exporting countries can initiate 11. Collins G. Strong international profits lift Philip Morris in quarter. New York

the development of an international convention for compre¬ Times. January 30, 1997:D2.

12. Parker-Pope T. At B. A. T., woes of US tobacco count for little. Wall Street

hensive, global tobacco control, with set timetables for imple¬ Journal. April 1, 1996:B1.

mentation of plans to control international sales, advertising, 13. US Dept of Agriculture. Tobacco: Situation and Outlook. Washington, DC:

Commercial Agriculture Division, Economic Research Service, US Dept of Agricul-

and smuggling of cigarettes. Without such an international ture; 1996. Publication TBS-235.

14. Bannister J. Vietnam Population Dynamics and Prospects. Berkeley: Institute

agreement, it is unlikely that any single exporting nation will of East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley; 1993.

take regulatory actions that put their own tobacco corpora¬ 15. Fforde A, de Vylder S. From Plan to Market: The Economic Transition in

Vietnam. Boulder, Colo: Westview Press Inc; 1996.

tions at a competitive disadvantage in the international mar¬ 16. Statistical Yearbook 1994. Hanoi, Vietnam: Statistical Publishing House; 1994.

ket. Such a convention was called for in 1996 by the World 17. Tinh hinh san xuat thuoc la hien nay va su can thiet dau tu phat trien san xuat

[The current tobacco production situation and investment needs for production de-

Health Assembly, WHO's governing body.28 velopment]. Hanoi, Vietnam: Ministry of Light Industry; 1992. Internal document.

In Vietnam, health education efforts appear to have suc¬ 18. Associated Press. Philip Morris licensed to make Marlboro cigarets in Vietnam.

ceeded in conveying the message that smoking and even Philippine Star. November 28, 1994:Business 31.

19. Flint A. In Vietnam, a new Western invasion. Boston Globe. June 9, 1996:B30.

secondhand smoking are hazardous to health. This knowl¬ 20. Shah BV, Barnwell BG, Bieler GS. SUDAAN User's Manual: Software for

Analysis of Correlated Data, Release 6.40. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research

edge, however, has not resulted in substantial numbers of Triangle Institute; 1995.

21. Craig D. Household health in Vietnam: a small reform. Asian Stud Rev. 1996;20:

smokers quitting. Unless forceful steps are taken to reduce 53-68.

smoking among men and prevent the uptake of smoking by 22. Nellen MEAH, Chapman S, Adriaanse H. Economic and social prosperity as a

predictor of national tobacco consumption. In: Slama K, ed. Tobacco and Health. New

youth and women, Vietnam will face a tremendous health and York, NY: Plenum Press; 1995:323-328.

economic burden in the near future. Health education and 23. Barry M. The influence of the US tobacco industry on the health, economy, and

environment of developing countries. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:917-920.

information campaigns should be tailored for rural commu¬ 24. Mackay JL. The fight against tobacco in developing countries. Tuber Lung Dis.

1994;75:8-24.

nities, where most of the population—and most smokers— 25.Chaloupka FJ, Laixuthai A. US Trade Policy and Cigarette Smoking in Asia.

live. Smoking bans, already in place, need to be more strictly Cambridge, Mass: National Bureau of Economic Research Inc; 1996. Working paper

5543.

enforced. Advertising bans should be modified to include 26. Do NH, Truong HT, Tran TH, Nguyen DXT. Smoking in women: a survey in Ho

point-of-purchase advertising, the offer of free samples, and Chi Minh City. In: Vietnam: A Tobacco Epidemic in the Making. Hanoi, Vietnam: Na-

tional Center for Human and Social Sciences, Institute of Sociology, Hanoi, the Health

sponsorship of sporting and cultural events. Prominent health Information and Education Center, Ho Chi Minh City Departartment of Health, the

warnings should be required on all cigarette packs. To dis¬ Hanoi Trade College, the University of California, San Francisco; 1995:89-91.

27. Reuters. Cigarette Firm Financing Soccer in Vietnam. December 19, 1994.

courage the initiation of smoking, especially by youth, taxes 28. WHO (World Health Organization) Programme on Tobacco or Health. An inter-

national framework convention for tobacco control. Tobacco Alert. July 1996:11-12.

on cigarettes should be raised and sales of cigarettes to mi¬

Available online at: http:///www.who.ch/programmes/psa/toh/Alert/jul96/E/index/html.

nors should be banned. Implementation of such a compre- Accessed April 24, 1997.

DownloadedViewFrom:

publicationhttp://jama.jamanetwork.com/

stats by a University of California - Davis User on 07/10/2014

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (589)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (842)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5806)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Thayer Consultancy Monthly Report April 2023Document29 pagesThayer Consultancy Monthly Report April 2023Carlyle Alan ThayerNo ratings yet

- Paradise Kitchen Sample Marketing PlanDocument17 pagesParadise Kitchen Sample Marketing PlanNKD100% (1)

- HảicmxDocument7 pagesHảicmxrose6xinhNo ratings yet

- Value Proposition Design - Thiết Kế Giải Pháp Giá TrịDocument314 pagesValue Proposition Design - Thiết Kế Giải Pháp Giá Trịlamthanh09012018No ratings yet

- Pepsi Next Case Study: Presented by - Surbhi Biyani Harsha Dhoot Prachi SopariwalaDocument26 pagesPepsi Next Case Study: Presented by - Surbhi Biyani Harsha Dhoot Prachi SopariwalaNKDNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Legalize Prostitution 1Document7 pagesRunning Head: Legalize Prostitution 1NKDNo ratings yet

- KoikatsuDocument4 pagesKoikatsuNKDNo ratings yet

- Bài tập PowerWorldDocument3 pagesBài tập PowerWorldNguyen Ngoc SangNo ratings yet

- IdeaDocument7 pagesIdea8hyrtsfhnjNo ratings yet

- Vietnam My Next Tourist DestintionDocument2 pagesVietnam My Next Tourist DestintionChinmaya ShankarNo ratings yet

- De KT Tieng Anh 7 Global Unit 5Document8 pagesDe KT Tieng Anh 7 Global Unit 5Huyền DiệuNo ratings yet

- Đề thi Lam Sơn - Thanh Hoá - 13 - 3Document5 pagesĐề thi Lam Sơn - Thanh Hoá - 13 - 3Đỗ LinhNo ratings yet

- Bat 21 and The Vietnam WarDocument2 pagesBat 21 and The Vietnam WardarsairaNo ratings yet

- Traditional Wedding of Vietnam: Welcome To Presentation of Group 2Document32 pagesTraditional Wedding of Vietnam: Welcome To Presentation of Group 2Nguyễn DươngNo ratings yet

- 3218 Uyen Nguyen My 10210652 ULC A1.1 14923 1514468528Document33 pages3218 Uyen Nguyen My 10210652 ULC A1.1 14923 1514468528Uyên Nguyễn MỹNo ratings yet

- Bai Tap Tieng Anh Lop 4 Theo Tung Unit 2019Document71 pagesBai Tap Tieng Anh Lop 4 Theo Tung Unit 2019Hang LeNo ratings yet

- Đến Với Lịch Sử Văn Hóa Việt Nam - Hà Văn TấnDocument407 pagesĐến Với Lịch Sử Văn Hóa Việt Nam - Hà Văn TấnHạnh DungNo ratings yet

- HUB Legal Department Compensation Claim by DR Romesh Senewiratne-Alagaratnam Arya Chakravarti $29.95Document18 pagesHUB Legal Department Compensation Claim by DR Romesh Senewiratne-Alagaratnam Arya Chakravarti $29.95Dr Romesh Arya ChakravartiNo ratings yet

- South Vietnam and The Politics of Self-SupportDocument26 pagesSouth Vietnam and The Politics of Self-SupportASIAANALYSISNo ratings yet

- Development RatingsDocument6 pagesDevelopment RatingsBlue Dragon Children's FoundationNo ratings yet

- BIỂU MẪU QUẢN LÝ NHÂN SỰ EXCELDocument56 pagesBIỂU MẪU QUẢN LÝ NHÂN SỰ EXCELKhai Trí Khưu NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Veitnam Defence Paper 2019Document134 pagesVeitnam Defence Paper 2019Rajat GargNo ratings yet

- Name: Huy Mai ID Number: 1566837: o Population Growth (Worldpopulationreview, 2021)Document8 pagesName: Huy Mai ID Number: 1566837: o Population Growth (Worldpopulationreview, 2021)Đức Minh ChuNo ratings yet

- Baùo Caùo Thöïc Taäp Oâ Toâ 1: Caàu Xe Chuû Ñoäng Daãn HöôùngDocument16 pagesBaùo Caùo Thöïc Taäp Oâ Toâ 1: Caàu Xe Chuû Ñoäng Daãn Höôùngnguyenhaicr9No ratings yet

- Mock Test 01.7Document13 pagesMock Test 01.7Ngân ThanhNo ratings yet

- Danh Sách Xe 12ADocument2 pagesDanh Sách Xe 12ATruong NhiNo ratings yet

- Renovation Washing RoomDocument12 pagesRenovation Washing RoomLý Chính ĐạoNo ratings yet

- 180 Bài Tập Viết Lại Câu Tiếng Anh - KhoaDocument17 pages180 Bài Tập Viết Lại Câu Tiếng Anh - Khoaquynguyenn0405No ratings yet

- Arup in Vietnam Eng 2019Document2 pagesArup in Vietnam Eng 2019Kiva DangNo ratings yet

- Marketing ManagementDocument23 pagesMarketing ManagementNghé ConNo ratings yet

- HUST Vietnam 2021 ProfileDocument35 pagesHUST Vietnam 2021 ProfilePhạm DươngNo ratings yet

- The Quiz Show: Appeared Would Presenter Value Out ofDocument5 pagesThe Quiz Show: Appeared Would Presenter Value Out ofChưa Đặt TênNo ratings yet

- Thayer Vietnam and The Vatican To Upgrade RelationsDocument3 pagesThayer Vietnam and The Vatican To Upgrade RelationsCarlyle Alan ThayerNo ratings yet

- Operational and Technical ProposalDocument82 pagesOperational and Technical ProposalTuyet DamNo ratings yet