Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Social Research

Uploaded by

ShahbazCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Social Research

Uploaded by

ShahbazCopyright:

Available Formats

Ricard Zapata-Barrero

Theorizing State Behavior

in International Migrations:

An Evaluative Ethical

Framework

Outlining the problem: the Analysis of state

behavior toward migrants

an emerging research agenda exists around the ethics of

migration. In this context, I would like to propose a research frame

work within a theory of state behavior in international migration.

My objective here is to discuss the first phase of the broader research:

justifying the need to establish an evaluative ethical framework for

analyzing state practices in relation to migration policies. In the second

phase, I will apply the framework to specific political practices, such as

bilateral agreements between receiving and sending countries, family

reunification policies, return policies, or state visa policies.

To drive the proposal, I put myself in the position of the policy

maker and ask the following question: What information resources

(positions, perspectives, discourses, target groups, etc.) does the policy

maker have or need to have for ethically orienting migration policies? I

ask this question in a determined context: the stage of first admission,

This paper belongs to a research project entitled “FRONTERAS,” funded by

the VI National Plan of Scientific Research, Development and Technological

Innovation 2008-2011, Ministry of Science and Innovation, Spain Consolidated

Group Ref: CSO2008-02181/CPOL.

social research Vol 77 : No 1 : Spring 2010 325

although it may be extended into other areas of immigration policies,

such as citizenship policies.

This reflection should help us theorize about state behavior

toward human mobility and propose a framework for addressing two

key issues, one related to difference between states, another to varia-

tions within a same state—namely, how to understand migration policy

differences and similarities between states and how to understand

migration policy change and permanence within the same state.

Migration and Borders: A review of the

normative debate

In the face of the current increase in international migration, the need

to recognize freedom of movement and human mobility begins to be

viewed as a serious issue that directly challenges the basic state expres-

sion of sovereignty: the control of borders.1 This does not refer to a

symbolic or conceptual border, but rather to the sea-air-land border

that territorially limits a state power jurisdiction.

Following on from the seminal work of Carens (1987), this norma-

tive debate has been referred to as the ethics of borders (Philpott 2001),

the ethics of migration (Seglow 2005b), the relation between borders

and justice (O’Neill 1994), democracy and borders (Balibar 2001), the

ethics of first admissions (Bader 1997, 2005; Gibney 1988; Carens 1999,

2000), or simply the case of open borders (Hayter 2001). Whatever the

label, the debate assumes at least two basic issues.

First, it is a debate based on finding that there are inconsisten-

cies in state practices if we compare liberal democratic principles and

current policies on border management. We are, therefore, situated

within a discursive context basically concerned with the distinction

between values and policies, having exhausted all possible measures

and resources that may be offered by the established institutional order.

This is the debate about principles, where inconsistencies are identi-

fied between the principles of freedom and equal respect championed

by the liberal democratic tradition, on the one hand, and state prac-

tices that constantly hinder the freedom of movement, on the other

326 social research

(Cole 2000; Meilaender 2001; Pécoud and de Guchteneire 2007). The

basic problem assumed is that liberal democracy, and the debate on

justice that it endorses, has real difficulties in conducting their argu-

ments beyond the traditional paradigm of the relation between states

and their citizens, neglecting the reality of increased human mobility

between states. To date, noncitizens have neither been contemplated as

beneficiaries of justice nor as subjects of liberal democratic thinking.

This debate has presupposed or ignored the issue of borders.2 Within

this theoretical framework there is also a line of discussion, related

to principles, which seeks to directly question asymmetrical situa-

tions that demonstrate the inconsistencies of political practice, such

as the asymmetry between the right of entry (the right of admission,

eminently under state sovereignty) and the human right of exit (no

state can impede the exit of its citizens), or the disparity between the

freedom of movement of goods, people, money and services (Barry and

Goodin 1992).

Second, and as a direct consequence of the first assessment, the

Kantian question of ethics par excellence is what frames the debate:

What can we do? That is, what alternatives to the current situation

can we propose? Although this is a theoretical question, it is oriented

toward practical principles. We find questions about whether closed

borders may be justified within our liberal democratic paradigm in

Gibney’s work (1988), and about whether restrictive policies may be

justified in Hudson’s work (1984). This debate originates from Carens’

influential article (1987) stating that strictly following the liberal prin-

ciples of freedom and equal respect does not justify the existence of

borders (neither according to the liberalism of Rawls, nor the liber-

tarianism of Nozick, nor utilitarianism). In this phase, the principle of

freedom of movement has been prevalent and has linked the issue of

border control with the very justification of the existence of borders

themselves, starting with the claim that the existence of borders is a

contingency upon which sovereignty is constructed. The positions in

favor of control have primarily been communitarian statist surrounded

by arguments of justice. Examples include the classic arguments of

Theorizing State Behavior in International Migrations 327

Walzer (1983) regarding the right of citizenry to decide about their own

community, as well as the three highly debated arguments based on

security, identity, and welfare (Kukathas 2005). Perhaps we might also

look to the reactions of Isbister (1999) and Meilaender (1999), who close

this phase of the debate about the foundations of borders.

Both trends in the debate are clearly idealistic in character,

supporting Carens’ article (1996) about realistic and idealistic perspec-

tives. Perhaps there are two suppositions in this first stage of ethics of

migration that ought to be problematized.

First, there is the supposition that the debate about open borders

vs. closed borders implies a debate about a “borderless world.” This

confusion is present in numerous works, even in one of the latest

studies sponsored by UNESCO, edited by Pécoud and de Guchteneire

(2007). An analytical distinction needs to be made with regard to this

issue: first where states maintain their borders, but allow freedom of

movement in common agreement with other states, as in the case of

the European Union’s Schengen area. People are permitted to cross

the border without controls, but the border as an institution remains

and is activated when conflicts or serious problems arise (recall that

Spain threatened France with respect to controlling the borders in the

Pyrenees if it continued allowing immigrants to cross). Let us call these

“stand-by borders” that can be “on-line” if a conflict arises. Hence, the

debate should move from the simple question of border controls to the

possibility of stand-by borders and occasional controls, with the border

remaining as a basic state institution.

Within this open/closed border debate there is also the discussion

of the literal disappearance of borders as state institutions. This founda-

tionalist discussion is first directly addressed by O’Neill (1994), whose

arguments are an example of anti-idealistic rationale that must be kept

in mind. Her analysis attempts to link borders and justice. As she herself

affirms, “Why several states are better than just one World state is the

best focus to approach the justification of boundaries” (O’Neill 1994:

70). For O’Neill, arguing in favor of a world without borders is equiva-

lent to challenging the existing plurality of states, and thus, advocat-

328 social research

ing for a world government that would inevitably become tyrannical

in the absence of the plurality necessary for balancing power. O’Neill

tells us “it is often said that a plurality of political units, hence of states,

is needed for justice, because World government would concentrate

power too much, and so endanger the very consideration—e.g. order,

freedom and other rights that are thought to legitimate government”

(O’Neill 1994: 71). O’Neill also advocates the argument that achieving

a world without borders would require all states to be liberal, since

nonliberal states would threaten our tradition’s liberal democratic

principles. With respect to the necessary conditions, we must consider

not only the political orientation of states, but also economic inequali-

ties between states, as they constitute one of the principal explanatory

factors for human mobility. A basic example of this is the Schengen

area within the European Union, which permits the internal mobility

of European citizens (Kunz and Leinonen 2007).

Second, existing literature tends to mix (and maybe confuse)

two quite distinct practices. It is assumed that the debate about border

controls (the debate about open/closed borders) implies a debate on flow

management. Both migration policy practices are, of course, related,

but do not necessarily imply each other.3 The emerging debate about

the external dimension of immigration policies,4 for example, begins

with the assumption that migratory flows and movement of people can

be managed without the need to control territorial borders. There are

“remote policies” (Zolberg 1999),5 a practice that needs to be debated in

terms of normative foundation and should be included in the debate on

ethics. This refers to the idea that it is possible to control the movement

of people without the need to control territorial borders, instead carry-

ing out measures of control before people choose to migrate. This type

of political orientation, in one way or another, challenges the supposed

framework of the debate: that controlling migration is equivalent to

controlling territorial borders. In addition, since this issue deals with

an act of externalizing the borders, there are implications regarding

the extension of state sovereignty that have yet to be debated from a

normative point of view.

Theorizing State Behavior in International Migrations 329

In short, the debate is combining desirability and viability, contrast-

ing the principles but with an interest in managing the contingencies of

radical proposals for opening borders.6 We now find ourselves in the phase

of viability where two types of debate prevail, each focused on an interest

in combining viability and achievability. The first regards recognition of the

right of human mobility as a basic human right. This is a debate that mobi-

lizes the principles and arguments of the discourse on the freedom of move-

ment, but that is more focused on the demand for a new human right: the

right of human mobility (Ugur 2007). The second regards the justification

of admission criteria, which have yet to be clearly defined, but that already

have a realistic desire to base themselves on criteria that mobilize states.

One of Carens’ last works takes this precise turn: from the frame-

work of desirability-viability to the framework of viability-achievability.

He asks, “What criteria do states use and what should they use in select-

ing . . . ?” (Carens 2003: 106). In his concluding arguments, he adds,

“even if one accepts the widely accepted premise that states have a right

to control immigration, there are still significant moral constraints on

how that control may be exercised” (Carens 2003: 110).7

We are really just at the beginning of analyzing the connection

between ethics, border management, and migration policies. In this

framework of the debate, I would like not so much to analyze what

states do in the area of migration policies as to theorize about the behav-

ior toward the demand for entry by people from other states. Analysis

of state behavior implies entering into the field of applied ethics and

taking a contextual approach. The construction of an ethical frame-

work for the evaluation of decision making represents a justified task

in the current context of migration policies in Europe, and can contrib-

ute to the incipient debate on the Ethics of migration.

An applied ethics of migration policies:

Fundamental premises

The ethical phenomenon that we are interested in dealing with is not

only a person’s demand for entry in a territory, but also human mobil-

ity between states. There are three important and interrelating prem-

330 social research

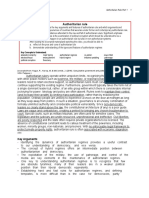

Migrant Immigrant Citizen

Figure 1: Stages of Migration

ises that we need to keep in mind when analyzing state behavior. A

political premise: the majority of people move from nonliberal demo-

cratic states, or states with difficulties consolidating liberal democracy,

to liberal democratic states. An economic premise: movement from the

third world or developing countries to economically consolidated coun-

tries. A social premise: movement of people attracted by our welfare

systems and social rights. In other words, we do not want to analyze

the movement of people between advanced liberal democracies with

similar economies and minimum social rights, such as the movement

of people within Europe or the Schengen area.

What implications might this line of thought have in the design

of migration policies? We will refer back to this question throughout

this paper. Specifically, my objective is to establish, justify, and criti-

cally discuss the ethical point of view in the debate on migration poli-

cies and the control of borders. And I would like to do that from an

applied perspective and in the framework of the “viability-achievabil-

ity” debate, introduced at the end of the last section.

In order to avoid formulating arguments that are too abstract,

we must be more precise when considering state frameworks for theo-

rizing about migration policies (Zolberg 1999). We specifically ask

what information resources (positions, perspectives, discourses, target

groups) the policymaker has to ethically orient migration policies. We

ask this question in a specific context: the migrant’s first entrance

gate (see figure 1). Later, once admitted, the “migrant” becomes the

Theorizing State Behavior in International Migrations 331

“immigrant,” with different legal obstacles to negotiate (different types

of residency permits) until finally achieving citizenship, if so desired,

with access to full citizenship rights (citizenship is always an option

and is never automatic for the immigrant).

Although the other stages can be considered within the perspec-

tive of borders, following the thread of the citizenship borders argu-

ment,8 what we particularly want to analyze here is the border that

coincides with the land border, “first admission.”

This stage is significant in ethical terms because we are facing

a “circumstance of justice” (in Rawls’ terms) that is significant to both

the principles and the criteria that guide distributive policies. In this

case, migration policies distribute the good that the entry into a state

represents, and the opportunity to reside and work in the receiving

society, along with other immigrants and citizens. It is important to

highlight that the policymaker is not facing a one-off situation, but

rather a social challenge. It is true that his decisions will affect different

individuals differently, but the frame of reference is always impersonal.

Therefore, we find ourselves facing a situation of ethical equality as

defined by Nagel (1991) in terms of impartiality. Furthermore, we must

not forget to mention that the state context is constantly present and

that we can either remain within or go beyond it in the ethical argu-

ment. In fact, if we are talking about the state context, we should also

mention the dimension of power behind the management of borders.

The border is the maximum expression of political power. In fact, the

functional definition of border is that it legally delimits a territory. In

this approach, classical definitions of the sovereign state that emerged

in the Westphalia period are used in international relations studies.

The border is a line that can be crossed, but only under the conditions

imposed by those inside it (Bigo 2001). The monopoly of the control

of borders is, perhaps, the last bastion of state sovereignty. There is a

direct link between border and state, up to the point that each needs

the other in order to define itself.

This framework is significant to applied ethics for at least four

reasons. First, the decisions being made affect third persons and the

332 social research

course of their lives.9 Second, we are in a situation of choice. Speaking

about ethics means speaking about options. In this respect, migration

ethics should examine the choices made by policymakers in control-

ling borders10 and also the decision to admit application for asylum

(Gibney 2004). The third reason is very much linked to ethics, consider-

ing the fact that the act of migration itself, in the strict sense, is not a

voluntary one. That is, people do not displace themselves of their own

will, but rather out of necessity. This need may be basic (such as the

need for decent shelter, a paid job, and for food and clothing) or more

complex (the need to change country for personal circumstances, in

order to study or work, or simply to give one’s children an education

and bring up a family in better conditions than in the country of origin).

Recognizing this implies that we are facing an ethical issue because it

affects one of the first foundations of ethics: the infringement of the

person’s will.11 The fourth and last reason we are facing a situation

significant to applied ethics is that we are discussing the approaches

and orientations of actions (Miller 1988: 651).

In short, we wish to analyze the ethical context that occurs when

there are people who wish to enter a state, and a state that limits this

freedom of movement. Of these four fundamental reasons that apply

to migration ethics, it is the practical situations requiring theorization

that most interest us.

Theorizing migration policy practices: facing

policy dilemmas

The policymaker finds himself in situations that are true moral dilem-

mas, in the sense that it is impossible for him to irrefutably know if the

decision to allow or deny entry of people moved by necessity is good and

right.12 One of the characteristics of these dilemmas is that they require

urgent responses. The dilemma is expressed not only at the level of

principles (which principle to follow) but also at a practical level (which

practice is the most appropriate for following up a principle). Generally

speaking, a situation characterized by a dilemma forces us to decide

between various possible practices. The information resources that can

Theorizing State Behavior in International Migrations 333

be used to respond to these dilemmas make up exactly what we call the

“evaluative ethical framework.”

We base our analysis on the system of reasoning available to the

policymaker when making an ethical decision. We want to consider at

least two theoretical issues directly linked to the political practice that

we are analyzing.

The task of policy evaluation is to challenge two types of tradi-

tional political policies. The first is evaluation centered on the relation

between policy aims and policy implementation. Focused primarily on

public political programs, an evaluation is made of what is said will

be done and the outcomes. Second, the evaluative task can be carried

out in terms of efficiency and effectiveness. For example, in the area

of migration, evaluative indicators can be introduced, based on the

hypothetical premise that zero migration is possible. In this case, the

number of people in irregular situations in a country allows us to evalu-

ate the migration policy in terms of access to borders. In this way, a

policy can be evaluated in terms of efficiency, taking into account the

objectives and resources used. However, all of these forms of evaluation

have a common denominator: the fact that they are based on the logic

of cost-benefit that always measures objectives, the means of reaching

them and outcomes.

In contrast, the framework that we propose deals with ethical

approaches and orientations. Further developing Zolberg’s relevant

observations on migration policy analysis (1999)—that is, it is not so

much who to let in, but rather who to leave out—this ethical debate

concerns both what is included and what is excluded. In both cases,

the partial or unequal treatment of migrants is directly discussed. Why

are some allowed entry and others not? What are the ethical references

that justify this inclusion or exclusion? How can the difference in treat-

ment of those demanding entry be ethically justified?

The theoretical task of proposing an evaluative ethical frame-

work is precedented by the work of Ruhs and Chang (2004) and Ruhs

(2005). Their approach has been centered on workers’ programs and

has an economic perspective that we, also, would like to discuss. To a

334 social research

certain extent, the effort made to think of migration ethics from the

point of view of the policies used and from the policymakers’ perspec-

tive is present in the work of Carens (2003) and Bader (2005). We would

like to develop the important turn they make in the normative debate.

Furthermore, the debate has always concerned the effects on the receiv-

ing society, driven by the question of which attitudes the state should

adopt in the face of demand for entry by migrants, without taking into

account all the actors involved, not just the state, but the citizens, the

immigrants, and the states of origin.

The policymaker’s information resources

There are two parameters around which decisions on policy revolve:

the numbers granted admission and the terms of admission. Kymlicka

considers, in his reflections on border ethics, that these two param-

eters are being constantly modified given that they reflect the assess-

ment of what is of interest to the political community (Kymlicka 2001:

264).13 These two parameters reflect the two fundamental questions of

how many should enter and who should enter. The first parameter is

quantitative in nature while the second has a more qualitative dimen-

sion. However, we need to know what information resources (positions,

perspectives, discourses, target groups) the policymaker has at hand for

designing a migration policy (see table 1).

Our intention is to consider each information resource (IR) sepa-

rately and later analyze the possible combinations that the policymaker

may make, leading to four ethical approaches and twelve orientations.

It is important to highlight that although we present some arguments

in dual terms, they should be interpreted gradually.14

IR 1. Ethical Position

There are at least two ethical traditions that can inform policymak-

ers.15 First, they may base their decisions on the teleological tradition

(Aristotelian), which takes purposes into account. In its modern form,

it is the tradition that focuses on the consequences of an action. In this

case, the aspect of what is good prevails over what is right. Therefore,

Theorizing State Behavior in International Migrations 335

Table 1: Information Resources (IR) and Categories Informing Policy-

maker Ethical Decisions

Information resources Categories

IR1. Ethical positions Deontology ——————— Consequentialism

IR2. Perspectives Nationalism ——————— Cosmopolitanism

Identity / Community (logic of inclusion/exclusion): origin,

community, language, skin colour, religion,….

Security / Stability (internal/external logic): economic (such as work,

IR3. Discourses on the ‘good’

salary), physical,…

Social welfare / cohesion (logic of access or no to state social

welfare): distributive justice, social equality,…

Society of origin

Collective Receiving Society

IR4. Target groups

Migrant

Individual

Citizen

a) Historical restrictions:

- Historical relation with the state of origin.

- Colonial past between receiving state and state of origin.

b) Socio-political and economical restrictions:

- Anti-immigration parties (and level of power in the party system)

-Economical context.

-Existence of an informal market

c) Structural and legal framework

d) position of actors

IR5. Economy of the ethics of - Administrative actors (different levels of administration)

first admission: contextual - Social actors (immigrant associations, citizen’s associations network,

restrictions. and NGO’s)

- Economic actors (business people and trade unions)

- Religious actors (the catholic church and institutions of other

confessions)

e) Diversity context and profile of the majority of the population:

- Skin colour

- Religion

- Language

f) Media and public opinion

- The media treatment and categorisation of immigrants

- Negative public opinion

the main aim is to manage the consequences of a political decision

focusing on outcomes. In utilitarian terms, its pursuit is to maxi-

mize the good, interpreted as identity, welfare, or security (the three

discourses on the good that we shall see in IR3). It is concerned about

the consequences of the migratory act in the country of origin as well

as the receiving country, for both the migrant and the citizen (the

four target groups we shall see in IR4). We shall see how the manage-

ment of consequences cannot only be focused on effects but also on

causes—what the literature refers to as the root-cause (Boswell, 2003).

336 social research

However, this we shall see later when we cross “Ethical Position” (IR1)

with ”Target Groups” (IR4).

At the other extreme we have the ethic that originates from the

Kantian tradition, which tells us that what is important is achieving the

principles, defined by duty, regardless of the consequences. In this case,

what is right prevails over what is good. The principle always prevails

over any other means of consideration. In general, this deontologi-

cal tradition does not manage consequences, but humanist a prioris,

such as considering the person in his moral and human statute, or also

depending on the perspective (IR2), according to national, ideologi-

cal, and religious conditions. As a human being, the person deserves

equal respect and should be treated as an end, and never as a means

of achieving other ends. This orientation adheres to certain principles

that can never be given up, although it generates consequences that do

not maximize the welfare, security, and identity (IR3) of the majority. If

necessary, pursuing this logic of ethical argument, the overall level of

welfare should be reduced so that a greater number can benefit.

IR 2. Perspectives

The perspective taken by each ethical position is always a determining

role in evaluating a decision. In order to understand them we must take

into account the population framework within which an ethical posi-

tion is found. This population framework can be linked to the category

of nation, characterized by a political community, or independent of it,

and include non-nationals. This means there is a division of the popu-

lation that can be the object of perspective, between those who are

nationals and those who are not, between those who are recognized

members of the state community and those who are not, given that

they have no system of direct relation with the state in the way citizens

do. Definitively, the frame of reference may be that which includes all of

humanity (cosmopolitanism) or that which is defined by a determined

state, for example citizenship (nationalism). The analytical basis of this

distinction focuses on the ever more visible differentiation between

those who belong to the category of population and those who belong

Theorizing State Behavior in International Migrations 337

to the category of citizens. Here the distinction lies between those who

fall under the state’s jurisdiction within the category of citizenship and

those within the noncitizen category. An admission policy does not

decide on citizenship, but rather on whether or not a person can form

part of the population category of a state.

Taking into account these two ways of categorizing people—

that is, they either form part of the population or part of the citi-

zenry—two perspectives are shaped: the cosmopolitan and the

nationalist, respectively. The nationalist perspective shapes its

arguments by taking into account the citizen population only,

identified as the population belonging to the political and cultural

community. The second perspective is that which breaks the distinc-

tion between the migrant and population, given that its territorial

frame of reference is not in the context of the state, but rather the

context of the world. In this case, cosmopolitanism rejects any

debate around priorities for justifying the treatment a person may

receive. Therefore, it rejects any moral argument that justifies up to

the last moment nationalistic patriotism. Necessity and humanitar-

ian attention are what should guide moral treatment, not the issue

of whether or not one belongs to a nation.

These two perspectives form the basis of two discourses, one

that takes the person into account, independent of nationality, and

another that specifically takes nationality into account.16 Here we are

referring to the difference between cosmopolitan universalism and

nation-state particularism. As we shall see, cosmopolitanism includes

the country of origin and the migrants themselves in its ethical

argument, while the nationalist argument does not take them into

account when resolving the moral dilemmas generated at the level of

first admission.

IR 3. Discourses on the Good

When speaking about the discourses on the good we think of three

categories: identity, security, and welfare (Kukathas 2005). Behind this

IR lies the premise that the state context determines discourses on the

338 social research

good. However, we argue that this discourse can be broader if the ethi-

cal position is cosmopolitan (we will link to IR2 and IR3 later).

These categories support different state logics. If we focus on the

category of identity, it is a known fact that the borders are symbolic

of cultural difference and identity. It has a direct relation with the

definition of “otherness” (Zapata-Barrero 2009b). It is also a historical

fact that the function of borders is to define cultural communities.

In this framework, the relation may be oriented in one of two direc-

tions: from borders to identity, and the other way around—that is,

the debate on whether borders create identity or whether the origin

of borders lies in the previous existence of an identity. In this case,

the logic of the argument is the logic of inclusion and exclusion, of

them and us, or as Zolberg (1999) correctly affirms, of like-us and not

like-us. The border is the line that separates identities. The interesting

fact is when territorial borders are expected to coincide with national

identities, and the logic of inclusion-exclusion is legitimately applied

by principles exclusively based on national identity (what we call the

nationalist perspective).

If we now move on to the category of security, we go into the

actual origin of the protective function of borders. In fact, this link

complies with the etymology of frontera (the Spanish word for border)

as “front” and ”barrier” to any external danger. The logic of the argu-

ment is the one that differentiates the external from the internal (rather

than inclusion from exclusion) and preservation. Here the argument is

based on maintaining order inside the border and preserving stability.

Inverting the effects of borders, with the disappearance of borders, the

main problems are related to order and stability (for example, O’Neill

1994).

Last but not least is the category of welfare. At this point, we must

accept that the ideas of social equality, distributive justice, and social

rights have always been thought of within this state framework of

implementation. Without borders, difficulties emerge in guaranteeing

the welfare state. The logic of the argument characterizing this cate-

gory is the access to the benefits of the social state. Thus, this empirical

Theorizing State Behavior in International Migrations 339

reference is fundamental in designing an ethical framework that can

orient first admission policies.

We can mention subcategories (identity, security, and welfare)

that help to define each narrative. These can be treated separately or be

combined in the ethical argument. In accordance with this viewpoint,

the discourse on identity conveys the notion of community, and can

manifest itself through the origin of the migrant, language, skin color,

and religion. The discourse on security conveys the notion of stability

and can manifest itself under the economic dimension of security (at

work, in maintaining a job, in maintaining a salary) but also physical

and national identity, including maintaining social dependence on the

state. Last, the discourse on welfare appears in the category of social

cohesion and can be shown under the socioeconomic ideas of distribu-

tive justice and social equality.

IR 4. Target Groups

The debate on migration policies tends to be two- or three-dimensional,

as it only builds arguments from the point of view of two actors (receiv-

ing society and immigrant) or three (the two aforementioned as well as

the society of origin). However, in reality there are at least four actors

that directly influence the ethical decision, each acting in its own inter-

ests: the migrant, the national citizen, the receiving society, and the

society of origin.

In this context, the policymaker can take into account either the

collective or individual dimension of the policy. By collective dimen-

sion we refer to two target groups: the receiving society or the society

of origin. By individual dimension we are especially thinking of the

migrant and of the national citizen.

IR 5. The Economy of the Ethics of First Admission: Contextual

Restrictions

Last, if we look from the policymaker’s viewpoint and in the frame-

work of the ethical decision, we can identify certain contextual

restrictions. Here, a variety of contexts exist, and not all of them act

340 social research

in the same way and at the same time. They can combine with each

other to varying degrees of intensity. They do not necessarily main-

tain relations with each other, as we have seen in the case of other

resources identified within the same category. We find, for example,

the historical relation with countries of origin, which may or may not

be linked with the colonial past. There are also information resources

related to society itself and how it reacts to the arrival of immigrants.

Here we are referring to negative public opinion and also to the exis-

tence of political parties that are clearly anti-immigrant (and their

level of power in the party system), or that have formed under this

same social fracture. The labor market situation plays a role in reduc-

ing the ethical argument and the existence of an informal economy.

Along the same lines, there can be structural factors, mainly coming

from the legal framework that can restrict ethical positions toward

migrants. Equally, the perceptions of other actors that form part of

the political system are also influential in deciding the orientation

of the criteria for first admission. We are referring to administrative

actors (public powers of the different levels of government), differ-

ent economic actors directly related to the management of the labor

market (such as workers’ unions and employers’ organizations), and

also social actors linked to the associations’ network (both citizen and

immigrant, including NGOs that are interested in the issue of first

admissions). We should also include the actors linked to the manage-

ment of beliefs and religious confessions (the Catholic Church, as it

forms part of the tradition on which society lies and is historically

linked to the state, but also others that wish to get involved with polit-

ical management). Last, but no less influential, is the contextual factor

of the media (both written and audiovisual) and how they categorize

immigration as negative or positive.

All these restrictions can condition an ethical decision, and can

help us to understand why states do not react always in the same way

(what we have called “policy change/permanence within a same state”)

and why states can decide to change their political orientation and ethical

view (what we have called policy differences/similarities between states).

Theorizing State Behavior in International Migrations 341

Table 2: Four Ethical Approaches to First Admission Policies

Deontology Consequentialism

Priority migrant (the person

Society of origin (the impact of the

without any relation to the national

Cosmopolitanism decision on the society of origin is

dimension has priority. The value

taken into account)

of equal respect prevails here)

Priority citizens (the national Receiving society (the impact of

citizen has priority over any the entry of migrants on the

Nationalism

interest that the migrant might receiving society is taken into

have) account)

Combining information resources: ethical

approaches and orientations.

To resolve the moral dilemmas between “allow entry” or “prohibit

entry,” and to ethically guide the decision, the policymaker establishes

combinations of these IR. Not all combinations are feasible, and not

all are relevant in delimiting an ethical framework. We emphasize the

following combinations: IR1/IR2/IR4, IR1/IR2/IR4 + IR3. The first combi-

nation shapes four ethical approaches (that make up frames of refer-

ence) and the second shapes twelve ethical orientations (focused on

aims).

Ethical approaches (IR1/IR2/IR4): If we combine IR1 (ethical posi-

tions) and IR2 (perspectives), we can establish four different ethical

approaches that differ in the priority given to one or other of the possi-

ble target groups (IR4). If we describe the ethical argument in brackets

(that is, the argument that responds to the moral dilemma of deciding

who and how many enter), this first combination may be schematically

represented as shown in table 2.

The general hypothesis is that a consequentialist nationalism

and a deontological nationalism prevail over a deontological cosmopol-

itanism and a consequentialist cosmopolitanism. Deontological cosmo-

politanism would favor the freedom of movement between states

and a system of “stand-by borders.” To date, this deontological cosmo-

politanism has only been possible between liberal democratic states,

with advanced economies and well-consolidated welfare systems.

Consequentialist cosmopolitanism would be that which orients the

policies that value the consequences of the decision of admission,

342 social research

Table 3: Twelve Ethical Orientations of the Policies of First Admission

Identity Security Welfare

The moral condition

Deontological of the individual

Security of the Welfare of the

Cosmopolitanism prevails over all other

migrant migrant

(Priority migrant) aspects of his/her

identity

Consequentialist

Respect for a person’s Security of society of Co-development and

Cosmopolitanism

identity origin help in developing

(Society of origin)

Deontological Priority in

Priority given to

Nationalism Security of the citizen guaranteeing social

citizen’s identity

(Priority citizen) welfare of citizen

Consequencialist

Priority given to Guarantee welfare

Nationalism National security

national identity state

(Receiving Society)

of who is allowed to enter and who is denied entry, on the society of

origin. Consequentialist cosmopolitanism is one of the channels being

adopted in the externalization of migration policies, linked to the

“root causes” and “remote control” approaches (Zolberg 2003; Aubarell

Zapata-Barrero and Aragall 2009).

Ethical orientations (IR1/ RI2/RI4 + IR3): These four ethical approaches

can be linked to the discourse on the goods (IR3), resulting in twelve

ethical orientations. One of the characteristics of table 2 is that it devel-

ops a multidimensional conception of each good and steers away from

evaluative criteria that sometimes accompany them in the academic

and public debates. For example, the good of security is not necessarily

positive or negative, but rather acquires a different value depending on

each ethical approach. That is, each ethical approach expresses a differ-

ent conception of the good (identity, security, welfare). Table 3 shows

the different ways of understanding goods.

Some general remarks for further research: On

the application of the ethical framework17

In essence, the policy orientation of the ethical framework results

in two types of action: it can help in both evaluating and designing

a migration policy. In the first case, it serves to describe a previously

made decision, illustrating its ethical approaches and orientations. It

Theorizing State Behavior in International Migrations 343

is true that both the description and design of a policy are placed at

the level of intentions, but it does not provide possibilities for using

the framework for evaluating outcomes. This reflection could probably

form a new basis for reflection.

Likewise, it is important to emphasize that the evaluative task of

the ethical framework is not to focus attention solely on the action of the

state, but rather on its different forms of expression through migration

policies. We, therefore, emphasize that the framework is useful for eval-

uating policy, and that a state may have a more cosmopolitan approach

toward a determined policy and simultaneously, a nationalist orienta-

tion in other aspects. This variety of approaches and orientations should

be the object of future analysis. Furthermore, the second function of the

framework may open the lines for further empirical research.

The viability for empirical analysis of the framework is funda-

mental, and we may focus our attention on the variety of ethical

approaches/orientations that exist within a state in a given moment

(synchronic empirical analysis), or how a policy’s approach or orienta-

tion varies over time (diachronic empirical analysis) and even migra-

tion policies between states (comparative analysis).

In fact, this is what happens in many cases. It is here that the

moral dilemma appears strongest at the state level, as it often conveys

specific policies in the terms of the ethical orientations and approaches

that we have described. Probably, one way of going more deeply into

this line of reflection is by including the IR6 (economy of the ethics

of first admissions: contextual restrictions), which doubtlessly helps to

shape explanatory arguments. It is true that a policy is ethically justi-

fied by the outcomes when these are very clearly favorable for the citi-

zens. The state can use a more cosmopolitan argument when they are

not. The ethical framework can provoke an explanatory debate on the

factors that make a state move from one orientation or approach to

another. Here the contextual framework is fundamental in making

sense of potential explanatory arguments.

The ethical framework helps answer two key issues: how we

might understand migration policy differences and similarities between

344 social research

states, and, how we might understand change and continuities within

a same state.

To conclude, it is clear that migration policies can only be

analyzed contextually as a set of practices. Let us propose four specific

cases: a) bilateral agreements between receiving states and states of

origin, especially those related to the labor market, but also those

produced in the externalization framework of migration policies (see

Aubarell et al. 2009). Continuing on from Caren’s open line of norma-

tive reflection (2003), we could also take the b) family reunification

policy and analyze the justifications of these policies to see if they

follow determined ethical orientations and approaches. Furthermore,

c) return policies (although they are not strictly first admission, they do

have a direct relation to first admission, given that someone who has

been granted admission, or entered illegally, is returned) and d) visa

policies could be very good practices to analyze.

However, this application of the framework would, without a

doubt, involve a second phase of research. What concerns us now is

whether or not the proposed evaluative ethical framework is justified

and if we have proved its potential viability for public policy analysis

and empirical research. Let us leave the debate open.

notes

1. We are reminded here of H. Arendt’s famous assertion “Theoretically, . . .

sovereignty is nowhere more absolute than in matters of emigration,

naturalization, nationality and expulsion” (Arendt 1973; 278, quoted

by Zolberg 1999)

2. In his suggestive article, W. Kymlicka reminds us that “silence or

taken as given of boundaries is an unsatisfactory approach to some of

the world’s most urgent problems.” And later on: “in the real world,

we can’t assume that existing boundaries are accepted, let alone that

they will be accepted in perpetuity. Nor can we assume that people

outside these boundaries have no desire or claim to enter the coun-

try. Any political theory which has nothing to say about these ques-

tions is seriously flawed” (Kymlicka 2001: 252).

Theorizing State Behavior in International Migrations 345

3. I first became aware of this distinction reading Cassarino’s suggestive

paper (2006). See also Delanty (2006).

4. See, among others, of theoretical concern, Boswell (2003), Lavenex

and Uçarer (2004), Debenedetti (2006), and Aubarell, Zapata-Barrero,

and Aragall (2009)

5. This refers to the idea that it is possible to control the movement of

people without the need to control territorial borders, instead carry-

ing out measures of control before people choose to migrate. This

type of political orientation still requires normative reflection, since

it challenges in one way or another the supposed framework of the

debate: that controlling migration is equivalent to controlling terri-

torial borders. In addition, since this issue deals with an act of exter-

nalizing the borders, there are implications regarding the extension

of state sovereignty that have yet to be debated from a normative

perspective.

6. However, it is framed within the debate on the utopian way of think-

ing. What is of interest to me is the use of Wright’s suggestive analytic

distinction between desirability, viability, and achievability (2007).

Combining all the components, his argument is that “not all desirable

alternatives are viable, and not all viable alternatives are achievable”

(2007: 28). In the exploration of desirability, one asks the question,

“What are the moral principles that a given alternative is supposed to

serve?” (2007: 28) We enter here into the field of normative political

theory. Its material consists of abstract principles, not institutional

arrangements. The study of viability “is a response to the perpetual

objection that radical egalitarian proposals ‘sound good on paper, but

will never work.’” (2007: 28).

7. The debate about a “world without borders” (Pécoud and de

Guchteneire 2007) is also moving toward the viability-achievability

logic framework, although there are still few proposals dealing with

both advances in theoretical analysis and specific political reforms.

We can quote for instance the proposal of creating a global fund

regime and a global tax that transfers wealth to poor countries (see

Philpott 2001 and Bader 1997, 2005).

346 social research

8. Let us remember the article by Hammar (2003) on the different

“gates” that the person must go through.

9. As Seglow (2005b: 318) declares, “Immigration controls involve

considerations of justice because they plainly greatly affect people’s

life chances.”

10. Here the work of Sullivan (1996) is relevant, given that she takes into

account the different settings of choice for both the state and the

migrant. She emphasizes that circumstances may occur where the

state has no choice, for example, in the case of asylum.

11. There are numerous works that contemplate the act of migration

as an act of necessity, and therefore, have a determined involun-

tary aspect (the ideal for a person is to stay in his/her country, if the

circumstances were different). This is one of the conclusions of the

Global Commission on International Migration (2005) and authors

such as Zolberg (1999), who always highlights the socioeconomic

aspect that goes with the act of migration, and Miller (1988: 661),

who addresses the issue that the “need of other human beings make

demand of justice.”

12. I use the definition in the Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy (2nd ed.,

2006): “moral dilemma refers to any topic where it is not known

what, if anything, is morally good or right” (584).

13. Other authors consider that the variable of economic impact is the

key to understanding the variation in policies (Ruhs and Chang

2004).

14. As Lomasky (2001: 70) argues: “most policy goals are analogous rather

than binary, that is, they are advanced to a greater or lesser extent

rather than being on/off.“

15. Here I base my argument on the works of Ruhs and Chang (2004) and

Ruhs (2005), although, I will deal with these traditions differently and

broaden their content.

16. This population framework was a criterion for differentiating

between a reactive discourse (only takes the voting citizen popula-

tion into account) and a proactive discourse (takes the whole popula-

tion into account). See Zapata-Barrero (2009a).

Theorizing State Behavior in International Migrations 347

17. I am grateful for the discussions we had when I first presented

this ethical framework at the Interdisciplinary Research Group in

Immigration (GRITIM-UPF) seminar of the Department of Social and

Political Science (UPF), which, without a doubt, has helped me to fine

tune arguments, discriminate approaches and evaluate the empirical

potential of the framework.

references

Arendt, Hannah. The Origins of Totalitarianism. New York: Harcourt Brace,

1973

Aubarell, Gemma, Ricard Zapata-Barerro, and Xavier Aragall. “New

Directions of National Immigration Policies: The Development

of the External Dimension and its Relationship with the Euro-

Mediterranean Process.” Euromesco Paper no. 79 (2009).

Audi, Robert, ed. Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy. 2nd ed. Cambridge,

U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Bader, Veit. “Fairly Open Borders.” Citizenship and Exclusion. Ed. V. Bader.

Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1997: 28-60.

———. “The Ethics of Immigration.” Constellations 12:3 (2005): 331-361.

Balibar, Etienne. Nous, citoyens d’Europe? Les frontières, l’Etat, le peuple. Paris:

La Découverte, 2001.

Barry, Bryan, and Robert Goodin, eds. Free Movement: Ethical Issues in the

Transnational Migration of People and of Money. University Park: The

Pennsylvania State University Press, 1992.

Bigo, Didier. “Internal and External Security(ies): The Möbius Ribbon.”

Identities, Borders and Orders. Eds. M. Albert, D. Bigo, M. Heisler, F.

Kratochwil, D. Jacobson, Y. Lapid. Minneapolis: University of

Minnesotta Press, 2001: 91-116.

Boswell, Christopher. “‘The External Dimension’ of EU Immigration and

Asylum Policy.” International Affairs 79:3 (2003): 619-683.

Carens, Joseph. “Aliens and Citizens: The Case for Open Borders.” Review

of Politics. 49 (Spring 1987): 251-273.

———. “Who Should Get In? The Ethics of Immigration Admission.”

Ethics and International Affairs 17:1 (2003): 95-110.

348 social research

———. “Realistic and Idealistic Approaches to the Ethics of Migration.”

International Migration Review 30:1 (1996): 156-170.

———. “A Reply to Meilaender: Reconsidering Open Borders.” International

Migration Review 33:4 (1999): 1082-1097.

Carens, Joseph. “Open Borders and Liberal Limits: A Response to Isbister.”

International Migration Review 34:2 (2000): 636-643.

Cassarino, Jean-Pierre. Approaching Borders and Frontiers: Notions and

Implications. Cooperation Project on the Social Integration of

Immigrants, Migration, and the Movements of Persons. Florence:

European University Institute, 2006.

Cole, Phillip. Philosophies of Exclusion. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University

Press, 2000.

Debenedetti, Sara. “Externalization of European Asylum and Migration

Policies.” Florence School on Euro-Mediterranean Migration and

Development. Robert Schuman Center for Advanced Studies,

2006.

Delanty, Gerard. “Borders in a Changing Europe: Dynamics of Openness

and Closure:” Comparative European Politics 4:2 (2006): 183-202.

Gibney, Mark, ed. Open Borders, Closed Societies? New York: Greenwood

Press, 1988.

Gibney, Mark. The Ethics and Politics of Asylum: Liberal Democracy and the

Response to Refugees. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Global Commission on International Migration. Migration in an

Interconnected World: New Directions for Action. October 2005.

Hammar, Tomas. “Denizen and Denizenship. “ Eds. A. Kondo and

Ch.Westin. New Concepts of Citizenship. CEIFO Publications no: 93.

Stockholm University, 2003.

Hayter, Teresa. “Open Borders: The case Against Immigration Controls.”

Capital and Class 75 (2001): 149-156.

Hudson, James. “The Ethics of Immigration Restriction.” Social Theory and

Practice. 10:2 (1984) 201-239.

Isbister, John. “Are Immigration Controls Ethical?” Eds. S. Jonas and S. D.

Thomas. Immigration: A Civil Rights Issue for the Americas. Wilmington,

Del.: Scholarly Resources, 1999: 85-98.

Theorizing State Behavior in International Migrations 349

Isbister, John. “A Liberal Argument for Border Controls: Reply to Carens.”

International Migration Review 34:2 (2000): 629-635.

Kukathas, Chandran. “The Case for Open Immigration.” Eds. A. I. Cohen

and C. H. Wellman. Contemporary Debates in Applied Ethics. Malden,

Mass.: Blackwell, 2005: 207-220.

Kunz, Jan, and Leinonen, Mari. “Europe without Borders: Rhetoric, Reality

or Utopia?” Migration without Borders: Essays on the Free Movement

of People. Eds. A. Pécoud and P. de Guchteneire. Paris: UNESCO

Publishing, 2007: 137-160.

Kymlicka, Will. “Territorial Boundaries: A Liberal Egalitarian Perspective.”

Eds. D. Miller and S. Hashmi. Boundaries and Justice: Diverse Ethical

Perspectives. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001: 249-275.

Lavenez, Sandra, and Emek Uçarer. “The External Dimension of

Europeanization: The Case of Immigration Policies.” Cooperation

and Conflict 39:4 (2004): 417-443.

Lomasky, Loren. “Toward a Liberal Theory of National Boundaries.”

Eds. D. Miller and S. Hashmi. Boundaries and Justice: Diverse Ethical

Perspectives. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001: 55-78.

Meilaender, Peter. “Liberalism and Open Borders: The Argument of Joseph

Carens.” International Migration Review 33:4 (1999): 1062-1081.

———. Toward a Theory of Immigration. New York: Palgrave Macmillan,

2001.

Miller, David. “The Ethical Significance of Nationality.” Ethics 98:4 (1988)

647-662.

———. “Immigration: The Case for Limits.” Eds. A. I. Cohen and C. H.

Wellman. Contemporary Debates in Applied Ethics. Malden, Mass.:

Blackwell, 2005: 193-206.

Miller, David, and Sohail Hashmi, eds. Boundaries and Justice: Diverse Ethical

Perspectives. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001.

Nagel, Thomas. Equality and Partiality. Oxford:Oxford University Press,

1991.

O’Neill, Onora. “Justice and Boundaries.” Ed. C. Brown. Political Restructuring

in Europe: Ethical Perspectives. London: Routledge, 1994: 69-88.

Pécoud, Antoine, and Paul de Guchteneire, eds. Migration without Borders:

350 social research

Essays on the Free Movement of People. Paris: UNESCO Publishing,

2007.

Philpott, Daniel. “The Ethics of Boundaries: A Question of Partial

Commitments.” Eds. D. Miller and S. H. Hashmi. Boundaries and

Justice. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001.

Ruhs, Martin. “Designing Viable and Ethical Labour Immigration Policies.”

Center on Migration, Policy and Society (COMPAS), University of

Oxford, June 2005.

Ruhs, Martin, and Ha-Joon Chang. “The Ethics of Labor Immigration

Policy.” International Organization 58:1 (2004): 69-102.

Seglow, Jonathan. “Immigration, Sovereignty, and Open Borders: Fortress

Europe and Beyond.” Review of Constitutional Studies 10:1-2 (2005a):

111-134.

———. “The Ethics of Immigration.” Political Studies Review 3:3 (2005b):

317-334.

Sullivan, Teresa. “Immigration and the Ethics of Choice.” International

Migration Review 30:1 (1996): 90-104.

Ugur, Mehmet. “The Ethics, Economics and Governance of Free

Movement.” Migration without Borders: Essays on the Free Movement

of People. Eds. A. Pécoud and P. de Guchteneire. Paris: UNESCO

Publishing, 2007: 65-96.

Walzer, Michael. Spheres of Justice. New York: Basic Books, 1983.

Wright, Erik Olin. “Guidelines for Envisioning Real Utopias.” Soundings 36

(2007) 26-39.

Zapata-Barrero, Ricard. Fundamentos de los discursos políticos en torno a la

inmigración. Madrid: Trotta, 2009a.

———. “Political Discourses about Borders: On the Emergence of a

European Political Community.” Ed. H. Lindahl. A Right to Inclusion

and Exclusion? Normative Fault Lines of the EU’s Area of Freedom, Security

and Justice. Oxford: Hart Publishing, 2009b: 15-31.

Zolberg, Aristide. “Matters of State: Theorizing Immigration Policy.” The

Handbook of International Migration: The American Experience. Eds. C.

Hirschman, P. Kasinitz, and J. DeWind. New York: Russell Sage,

1999: 71-93.

Theorizing State Behavior in International Migrations 351

———. “The Archaeology of “Remote Control.” Migration Control in the

North Atlantic World: The Evolution of State Practices in Europe and the

United States from the French Revolution to the Inter-War Period. Eds. A.

Fahrmeir, O. Faron, and P. Weil. New York: Berghahn Books, 2003:

195-222.

352 social research

You might also like

- Stanley Hoffmann Ethics in IRDocument27 pagesStanley Hoffmann Ethics in IRPaula Castiglioni100% (1)

- LD - JanFebDocument112 pagesLD - JanFebGilly FalinNo ratings yet

- The Power of Human RightsDocument74 pagesThe Power of Human RightsMaya BoyleNo ratings yet

- Global Justice As Ethico-Political Labor and The Enactment of Critical CosmopolitanismDocument18 pagesGlobal Justice As Ethico-Political Labor and The Enactment of Critical CosmopolitanismMark S MarkNo ratings yet

- IPSA Paper Gay Rights Are Human Rights Final 32589Document63 pagesIPSA Paper Gay Rights Are Human Rights Final 32589Anirudh KaushalNo ratings yet

- Constitutionalizing Polycontexturality in a Globalized WorldDocument25 pagesConstitutionalizing Polycontexturality in a Globalized WorldVitor SolianoNo ratings yet

- Migration in Legal and Political Theory, Eds. Sarah Fine and Lea Ypi (Oxford, Forthcoming)Document17 pagesMigration in Legal and Political Theory, Eds. Sarah Fine and Lea Ypi (Oxford, Forthcoming)text7textNo ratings yet

- From Molehills To Mountains - and Myths - A Critical History of Transitional Justice AdvocacyDocument82 pagesFrom Molehills To Mountains - and Myths - A Critical History of Transitional Justice AdvocacyMary SuescaNo ratings yet

- Matthew Waites Critique of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in Human Rights DiscourseDocument21 pagesMatthew Waites Critique of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in Human Rights DiscourseIriz BelenoNo ratings yet

- Comment On Held's From Executive To Cosmopolitan Multilateral IsmDocument7 pagesComment On Held's From Executive To Cosmopolitan Multilateral IsmmarlinbennettNo ratings yet

- Transnational Governance and Constitutionalism International Studies in The Theory of Private LawDocument403 pagesTransnational Governance and Constitutionalism International Studies in The Theory of Private LawHector CuryNo ratings yet

- U J N S T C A C: María Luisa BartolomeiDocument41 pagesU J N S T C A C: María Luisa BartolomeiMike SiscoNo ratings yet

- Hughes 2020Document6 pagesHughes 2020Irvhyn Hinostroza AbadNo ratings yet

- Coevolving Relationships Between Political Science and EconomicsDocument15 pagesCoevolving Relationships Between Political Science and EconomicsFahad Jameel SheikhNo ratings yet

- An Ethics of Human Rights - Two Interrelated MisunderstandingsDocument23 pagesAn Ethics of Human Rights - Two Interrelated MisunderstandingsLucky SharmaNo ratings yet

- Comparative Public PolicyDocument20 pagesComparative Public PolicyWelly Putra JayaNo ratings yet

- Critique of Rights Discourse in Left Legal ThoughtDocument50 pagesCritique of Rights Discourse in Left Legal ThoughtplainofjarsNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 34.195.88.230 On Sun, 24 Jan 2021 23:40:29 UTCDocument20 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 34.195.88.230 On Sun, 24 Jan 2021 23:40:29 UTCmarting91No ratings yet

- UR V12 ISS-1 10to16 IlievaDocument7 pagesUR V12 ISS-1 10to16 IlievaJana IlievaNo ratings yet

- Anne Marie Slaughter - International Law in A World of Liberal StatesDocument36 pagesAnne Marie Slaughter - International Law in A World of Liberal StatesLimeng OngNo ratings yet

- Victim Reparations in Transitional Justice-What IsDocument93 pagesVictim Reparations in Transitional Justice-What IsHector Puerta OsorioNo ratings yet

- political theory and International lawDocument17 pagespolitical theory and International lawshivesh sainiNo ratings yet

- The Challenge of Globalization On Citizenship: Topic 10Document26 pagesThe Challenge of Globalization On Citizenship: Topic 10Eleonor ClaveriaNo ratings yet

- 5420 Ijhas 03Document7 pages5420 Ijhas 03Sachin VermaNo ratings yet

- The International Legal OrderDocument30 pagesThe International Legal OrderBerna GündüzNo ratings yet

- SpringerDocument18 pagesSpringerKostas BizasNo ratings yet

- The Self-Perceived Gender Identity PDFDocument17 pagesThe Self-Perceived Gender Identity PDFMarta Mercado-GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Handbook On The Rule of Law: The Invisible Constitution of Politics: Contested Norms and International EncountersDocument2 pagesHandbook On The Rule of Law: The Invisible Constitution of Politics: Contested Norms and International EncountersCthutqNo ratings yet

- The Rejection of Human Rights Framings: The Case of LGBT Advocacy in The USDocument30 pagesThe Rejection of Human Rights Framings: The Case of LGBT Advocacy in The USSurya Ageng PriambudiNo ratings yet

- International RelationsDocument23 pagesInternational RelationsRocking SheikhNo ratings yet

- Slaughter (1993) - International Law and International Relations TheoryDocument36 pagesSlaughter (1993) - International Law and International Relations TheoryJessica SteinemannNo ratings yet

- CASE STUDY Global JusticeDocument5 pagesCASE STUDY Global JusticeManviNo ratings yet

- Transitions To Democracy and Democratic Consolidation: Theoretical and Comparative IssuesDocument43 pagesTransitions To Democracy and Democratic Consolidation: Theoretical and Comparative IssuesigonboNo ratings yet

- From Backsliding To Illiberalism and Beyond - Law AndRegressive Political ChangeDocument28 pagesFrom Backsliding To Illiberalism and Beyond - Law AndRegressive Political Change李小四No ratings yet

- Neorealism, Neoliberalism and Regimes in International RelationsDocument14 pagesNeorealism, Neoliberalism and Regimes in International RelationsILINCANo ratings yet

- Smith Chapter in M Goodhart Human Rights - DScholarship VersionDocument16 pagesSmith Chapter in M Goodhart Human Rights - DScholarship VersionPRADEEP RAMAVATH JAYANAIKNo ratings yet

- Political Neutrality and PunishmentDocument14 pagesPolitical Neutrality and PunishmentIana Solange Ingrid MarinaNo ratings yet

- Feminist Theory 2016 Tapia Tapia 141 56Document16 pagesFeminist Theory 2016 Tapia Tapia 141 56AlejandroHdzLuisNo ratings yet

- George Sorensen - What Kind of World OrderDocument28 pagesGeorge Sorensen - What Kind of World Ordermatiasaugusto9No ratings yet

- POLITICS BEYOND THE STATE: World Civic ActivismDocument30 pagesPOLITICS BEYOND THE STATE: World Civic ActivismNicole NasrNo ratings yet

- "The Walls Will Not Be Silent:" A Cautionary Tale About Transitional Justice and Collective Memory in EgyptDocument21 pages"The Walls Will Not Be Silent:" A Cautionary Tale About Transitional Justice and Collective Memory in EgyptLuluNo ratings yet

- Reflections on Migration and GovernmentalityDocument25 pagesReflections on Migration and GovernmentalityWalter MendozaNo ratings yet

- Law Social Inquiry ArticleDocument38 pagesLaw Social Inquiry ArticleAshwini KrishnanNo ratings yet

- Researchdossier2020 LetterwritersDocument6 pagesResearchdossier2020 Letterwritersapi-512570058No ratings yet

- Transnational Human Rights NetworksDocument35 pagesTransnational Human Rights NetworksJey GhafezNo ratings yet

- The Spaces of Democracy and The Democracy of Space A New Network Exploring The Disciplinary Effects of The Spatial TurnDocument7 pagesThe Spaces of Democracy and The Democracy of Space A New Network Exploring The Disciplinary Effects of The Spatial TurnJames Mwangi100% (1)

- The Prosecution of Human Rights Violations: FurtherDocument20 pagesThe Prosecution of Human Rights Violations: FurtherJairo Antonio LópezNo ratings yet

- The Political Origins of The New ConstitutionalismDocument39 pagesThe Political Origins of The New ConstitutionalismThiagoNo ratings yet

- Cosmopolitan State - BeckDocument18 pagesCosmopolitan State - BeckAlberto Bórquez ParedesNo ratings yet

- Turchin Etal 2018 Evolutionary Pathways To StatehoodDocument18 pagesTurchin Etal 2018 Evolutionary Pathways To StatehoodWaqas Ahmed JamalNo ratings yet

- Law, Globalisation and The Second ComingDocument24 pagesLaw, Globalisation and The Second Cominggabriela alkminNo ratings yet

- Identity Formation and The International StateDocument14 pagesIdentity Formation and The International StateGünther BurowNo ratings yet

- StateDocument29 pagesStatepsykhanNo ratings yet

- The Rules of Human Rights Conflicts (Evolved Policy of Human Rights)Document10 pagesThe Rules of Human Rights Conflicts (Evolved Policy of Human Rights)Dr.Safaa Fetouh GomaaNo ratings yet

- The Strange Neglect of Normative International Relations Theory Environmental Political Theory and The Next FrontierDocument24 pagesThe Strange Neglect of Normative International Relations Theory Environmental Political Theory and The Next Frontierapto123No ratings yet

- Afterword To "Anthropology and Human Rights in A New Key": The Social Life of Human RightsDocument7 pagesAfterword To "Anthropology and Human Rights in A New Key": The Social Life of Human RightsDani MansillaNo ratings yet

- The Complex Conceptual Relationship Between Political Institutions and PopulismDocument19 pagesThe Complex Conceptual Relationship Between Political Institutions and Populismjuaest01No ratings yet

- 2008, Diane Stone, Global Public Policy, Transnational Policy Communities and Their Networks PDFDocument37 pages2008, Diane Stone, Global Public Policy, Transnational Policy Communities and Their Networks PDFMaximiliano Prieto MoralesNo ratings yet

- Global Public Policy StoneDocument21 pagesGlobal Public Policy StonemoeedbinsufyanNo ratings yet

- The National Interest, August 19, 2013: China's South Asia DriftDocument2 pagesThe National Interest, August 19, 2013: China's South Asia DriftShahbazNo ratings yet

- The Politics of Ethnicity in Sindh: Muhajir Perceptions of Declining RepresentationDocument19 pagesThe Politics of Ethnicity in Sindh: Muhajir Perceptions of Declining RepresentationShahbazNo ratings yet

- China-Russia Alliance DeepensDocument2 pagesChina-Russia Alliance DeepensShahbazNo ratings yet

- AccountAbility-UN Global CompaDocument1 pageAccountAbility-UN Global CompaShahbazNo ratings yet

- The National Accountability Commission Bill 2012 PDFDocument2 pagesThe National Accountability Commission Bill 2012 PDFShahbazNo ratings yet

- 25 ScatterDocument3 pages25 ScatterManoj Kumar GNo ratings yet

- AccountAbility - Setting The Standard For Corporate Responsibility and Sustainable Development - AccountAbility-UN Global Compa PDFDocument2 pagesAccountAbility - Setting The Standard For Corporate Responsibility and Sustainable Development - AccountAbility-UN Global Compa PDFShahbazNo ratings yet

- (Elearnica - Ir) - Air-Lift Bioreactors For Algal Growth On Flue Gas Mathematical ModelingDocument10 pages(Elearnica - Ir) - Air-Lift Bioreactors For Algal Growth On Flue Gas Mathematical ModelingalirezamdfNo ratings yet

- Communication Skills (MCM 301) : 1. Think SmartlyDocument5 pagesCommunication Skills (MCM 301) : 1. Think SmartlyShahbazNo ratings yet

- Developing Leaders from Base Camp to SummitDocument27 pagesDeveloping Leaders from Base Camp to SummitShahbazNo ratings yet

- Selected Daud Kamal Poems and Afterword PDFDocument5 pagesSelected Daud Kamal Poems and Afterword PDFSana NadeemNo ratings yet

- CS101 Introduction to Computing Course OverviewDocument59 pagesCS101 Introduction to Computing Course OverviewirfanvuNo ratings yet

- Differences between Marketing and SellingDocument3 pagesDifferences between Marketing and SellingShahbaz khanNo ratings yet

- Accountability and A Responsibility Based Workplace PPT HODocument37 pagesAccountability and A Responsibility Based Workplace PPT HOShahbazNo ratings yet

- To Business Lecture No 1Document12 pagesTo Business Lecture No 1Shahbaz khanNo ratings yet

- Lecture 24Document2 pagesLecture 24ShahbazNo ratings yet

- Market Research Process for New BusinessDocument5 pagesMarket Research Process for New BusinessShahbazNo ratings yet

- Cs101 Lec02Document42 pagesCs101 Lec02Fahad NabeelNo ratings yet

- Cs101 Lec04Document40 pagesCs101 Lec04Umair LiaquatNo ratings yet

- CS101 Introduction To ComputingDocument8 pagesCS101 Introduction To ComputingShahbazNo ratings yet

- National Defence University, Islamabad PakistanDocument36 pagesNational Defence University, Islamabad PakistanShahbazNo ratings yet

- The Impact of The Media On National Security Policy Decision MakingDocument34 pagesThe Impact of The Media On National Security Policy Decision MakingchovsonousNo ratings yet

- Cs101 Lec03Document41 pagesCs101 Lec03Fahad NabeelNo ratings yet

- External EnvironmentDocument4 pagesExternal EnvironmentShahbaz khanNo ratings yet

- Foreign Investment and National SecurityDocument27 pagesForeign Investment and National SecurityShahbazNo ratings yet

- Cyber Warfare-ImplicationDocument63 pagesCyber Warfare-ImplicationShahbaz0% (1)

- The Disputed Durand Line: Geography in The News™Document1 pageThe Disputed Durand Line: Geography in The News™ShahbazNo ratings yet

- A Law For Crossing The Durand LineDocument4 pagesA Law For Crossing The Durand LineManzoor HussainNo ratings yet

- 5Document26 pages5farazahmedkhanNo ratings yet

- The Durand LineDocument19 pagesThe Durand LineShahbazNo ratings yet

- Pol101 - ReportDocument13 pagesPol101 - ReportEshrat Tarabi Shimla 2211281030No ratings yet

- HSY2601 Study GuideDocument154 pagesHSY2601 Study GuideDeutro HeavysideNo ratings yet

- Western Civilization, Our Tradition PDFDocument9 pagesWestern Civilization, Our Tradition PDFDarío Fernando RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Olw 101 - Constitutions and Legal System of East AfricaDocument33 pagesOlw 101 - Constitutions and Legal System of East Africahabiye201382% (11)

- ThesisDocument19 pagesThesisrichie sNo ratings yet

- Democratic Rights Movement in India - PapersDocument156 pagesDemocratic Rights Movement in India - PapersSatyam VarmaNo ratings yet

- Global Populisms and Their ChallengesDocument24 pagesGlobal Populisms and Their ChallengesAN725No ratings yet

- How Fascism Seized the Masses in YugoslaviaDocument11 pagesHow Fascism Seized the Masses in YugoslaviaRastkoNo ratings yet

- Against Identity Politics The New Tribalism and The Crisis of Democracy by Francis FukuyamaDocument33 pagesAgainst Identity Politics The New Tribalism and The Crisis of Democracy by Francis FukuyamazdododNo ratings yet

- Jenkins, - Klandermans The - Politics of Social Protest 1Document388 pagesJenkins, - Klandermans The - Politics of Social Protest 1Mar DerossaNo ratings yet

- Africana, 3, Dec. 2009Document113 pagesAfricana, 3, Dec. 2009EduardoBelmonteNo ratings yet

- Monarchy (Bachelor Thesis 2006)Document61 pagesMonarchy (Bachelor Thesis 2006)Sancrucensis100% (2)

- Authoritarian Rule FeaturesDocument22 pagesAuthoritarian Rule FeaturesEevee CatNo ratings yet

- Integralist Manifesto - October 1932Document5 pagesIntegralist Manifesto - October 1932bruhgNo ratings yet

- Overview of Political BehaviorDocument31 pagesOverview of Political BehaviorPatricia GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Roxburgh, Shelagh - Witchcraft, Violence and Mediation in Africa - A Comparative Study of Ghana and Cameroon (2014)Document256 pagesRoxburgh, Shelagh - Witchcraft, Violence and Mediation in Africa - A Comparative Study of Ghana and Cameroon (2014)Pedro SoaresNo ratings yet