Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Hubungan Merokok Sama Led

Hubungan Merokok Sama Led

Uploaded by

Alessandra NidiaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Hubungan Merokok Sama Led

Hubungan Merokok Sama Led

Uploaded by

Alessandra NidiaCopyright:

Available Formats

Clinical and Laboratory Investigations

Dermatology 2005;211:118–122 Received: July 15, 2004

Accepted: December 20, 2004

DOI: 10.1159/000086440

Association between Discoid Lupus

erythematosus and Cigarette Smoking

A Case-Control Study

Hélio Amante Miota Luciane Donida Bartoli Miota

Gabriela Roncada Haddadb

a

Dermatology Department and b Internal Medicine, UNESP Medical School, Botucatu, Brazil

Key Words Introduction

Cigarette smoking ! Discoid lupus erythematosus

Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) is a chronic, be-

nign inflammatory skin disease characterized by discrete-

Abstract ly infiltrated erythematous scaly plaques of varying sizes,

Background: Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) is a well-defined borders and atrophic centers generally in-

chronic cutaneous disease affecting photoexposed ar- volving the face and photoexposed areas. The plaques

eas and has also been associated with cigarette smoking. evolve with scarring and a tendency to hypochromia. Le-

Objective: To evaluate the association between smoking sions can be restricted to the face or head or be diffuse

and DLE. Methods: A case-control study was performed [1]. The mean age for DLE development is between 20

involving 57 cases diagnosed with DLE and 215 healthy and 40 years, with a female-to-male ratio of 2–3:1 [2].

controls. Results: A higher smoking prevalence was not- Some authors consider DLE a benign and localized

ed in DLE cases (84.2%) than controls (33.5%), and the form of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), since dis-

odds ratio adjusted for gender, age and ultraviolet index coid lesions occur in 5–15% of patients with the systemic

in the city of origin was 14.4 (95% confidence interval disease, sometimes appearing before its overt manifesta-

6.2–33.8; multiple logistic regression, p ! 0.01). The cu- tion [1, 3].

mulative smoking exposure was not related to prema- The etiology is autoimmune with genetic, hormonal

ture DLE development. At the beginning of the disease, and environmental factors involved. Cigarette smoking

smokers had more extensive involvement than non- was suggested as an environmental trigger that induces

smokers; compromise of the upper arms was statisti- DLE in genetically predisposed individuals [3]. The influ-

cally related to smoking. Conclusion: Cigarette smoking ence of smoking on the immune system can be demon-

was statistically associated with DLE development. Oth- strated in other inflammatory diseases such as SLE,

er studies are needed in order to evaluate the effects of Crohn’s disease, psoriasis vulgaris, Goodpasture’s syn-

smoking cessation on the course of disease. drome, Graves’ disease, primary biliary cirrhosis, rheu-

Copyright © 2005 S. Karger AG, Basel matoid arthritis, pustulous palmoplantar psoriasis and

Siriraj Medical Library, Mahidol University

198.143.39.97 - 1/27/2016 4:02:15 PM

© 2005 S. Karger AG, Basel Dr. Hélio Amante Miot

1018–8665/05/2112–0118$22.00/0 Departamento de Dermatologia da UNESP, SN

Fax +41 61 306 12 34 Campus Rubião Jr

Downloaded by:

E-Mail karger@karger.ch Accessible online at: Botucatu, SP 18618–000 (Brazil)

www.karger.com www.karger.com/drm Tel./Fax +55 21 14 3882 4922, E-Mail heliomiot@uol.com.br

thromboangiitis obliterans. Conversely, smoking is also

associated with decreased inflammatory activity in idio-

pathic ulcerative colitis [4, 5].

This study aims to evaluate the association between

cigarette smoking and DLE.

Methods

A case-control study was performed. Epidemiological informa-

tion on DLE and smoking habits was obtained with a standard

questionnaire. Cases with a clinical and histopathological diagnosis

of DLE who did not meet 4 or more SLE criteria were selected from

the connective diseases outpatient clinic of Hospital das Clínicas,

UNESP Medical School, between July 2002 and October 2003 [6].

Four controls were selected for each case from spouses, close rela- Fig. 1. Smoking prevalence according to age distribution (!2 p !

tives and household members; they were paired with cases accord- 0.05).

ing to sex, age and city of origin [7]. Cases were personally inter-

viewed after their consultation, and controls were individually con-

tacted by telephone.

The authors considered current smokers as those who were

smoking at the time of the interview and had been smoking at least Table 1. Comparisons between cases and controls

4 cigarettes/day for 4 years. The odds ratio (OR) was adjusted for

possible confounding factors: age, sex and ultraviolet index from DLE Controls p value

the city of origin using multiple logistic regression [7]. The popula-

tion-attributable risk was calculated using the adjusted OR, and n 57 215

smoking prevalence in the control group represented prevalence in Sex

the population [8]. Females 40 (70.2) 147 (68.4) >0.05 (!2)

Data were recorded and analyzed with Bioestat 2.0™, consider- Males 17 (29.8) 68 (31.6)

ing a significance of p ! 0.05 [9]. Median age 8 SD, years 40.0810.1 39.0816.4 >0.05 (t test)

UVO

5 54 (94.7) 198 (92.1) >0.05 (Yates)

6 3 (5.3) 17 (7.9)

Results

p values are unadjusted; UVO = ultraviolet index from the city

of origin; figures in parentheses are percentages.

Initially, 61 cases were selected, but 4 were excluded

for lack of histopathological examination, inconclusive

clinical diagnosis or diagnosis of SLE. The 215 control

cases were representative in comparison to cases for gen-

der, age and ultraviolet index from the city of origin Table 2. Epidemiological description of cases

(table 1).

There were more female cases (2.4:1), but there was p value

no difference in smoking rates between sexes; by the way, Median age at the beginning

among controls smoking was more prevalent in men (!2 of DLE 8 SD, years 31.089.6

p ! 0.01). Smoking prevalence was significantly higher for Females 31.089.2 >0.05 (t test)

adults in DLE groups at any age (fig. 1). Males 30.0810.6

The median age for disease development was 31 years, Smokers 31.088.6

>0.05 (t test)

Nonsmokers 25.0813.8

with no differences according to sex or smoking exposure Median age when they started

(table 2). Only 1 case had a close relative (sister) with smoking 8 SD, years 14.085.3

DLE; this is consistent with the literature on familial oc- Females 14.085.7

>0.05 (t test)

currence (!1.8%). Males 16.084.2

DLE affected the face most (91.2%), followed by the Proportion of smokers 48 (84.2%)

Females 34 (85.0%)

upper arms, neck and ears (table 3). Upper and lower arm Males 14 (82.4%)

>0.05 (Fisher)

occurrence was only found in smokers; the prevalence of

Siriraj Medical Library, Mahidol University

198.143.39.97 - 1/27/2016 4:02:15 PM

Discoid Lupus erythematosus and Dermatology 2005;211:118–122 119

Cigarette Smoking

Downloaded by:

smoking in patients with upper arm lesions was the only Table 3. Topographical distribution (%) of initial lesions and rela-

one to reach statistical significance. There was no statisti- tionship to smoking

cal association between the lesion topography and sex or

Smokers Non- Total p value

age (Fisher p 1 0.05). The number of body sites affected smokers

by the disease at the outset was significantly higher in

smokers (166.0%) (table 3). Face 91.7 88.9 91.2 >0.05 (Fisher)

Most DLE cases had started smoking at an early age Upper arms 43.8 – 36.8 <0.03 (Fisher)

Neck 25.0 22.2 24.6 >0.05 (Fisher)

(median 14 years) and presented an average consumption

Ears 22.9 11.1 21.1 >0.05 (Fisher)

of 29 cigarettes per day. There was no difference in smok- Scalp 16.7 11.1 15.8 >0.05 Fisher

ing prevalence between sexes (table 2). All DLE cases who Back 12.5 – 10.5 >0.05 (Fisher)

smoked had started smoking before developing the dis- Others 8.3 – 7.0 >0.05 (Fisher)

ease, with a mean interval of 17.4 8 9.1 years, but there Mean count of

affected regions 2.2 1.3 2.1 <0.05

was no relationship between the number of cigarettes

(Mann-Whitney)

smoked or accumulated smoking exposure until disease

development (Pearson p 1 0.05). p values are unadjusted.

There was a higher smoking prevalence in cases (84.2%)

compared to controls (33.5%) (table 4), and the calcu-

lated OR after adjustment for sex, age and ultravio-

let index from the city of origin was 14.4 (95% confi-

Table 4. Association between smoking and DLE

dence interval, 6.2–33.8, multiple logistic regression,

p ! 0.01).

DLE Controls Total

The population-attributable risk was estimated as

81.8% (95% confidence interval, 65.7–91.0%). Smokers 48 (84.2%) 72 (33.5%) 120

Nonsmokers 9 (15.8%) 143 (66.5%) 152

Total 57 215 272

Discussion

Unadjusted OR = 10.6 (95% confidence interval, 4.9–22.8),

p < 0.01. OR adjusted for sex, age and ultraviolet index from the

The higher smoking prevalence in DLE patients city of origin = 14.4 (95% confidence interval, 6.2–33.8), p < 0.01,

strongly suggests a relationship with disease develop- multiple logistic regression.

ment.

In another controlled study with fewer participants,

the smoking prevalence in DLE cases was 82% with an

OR of 12.2. The same study showed a higher cigarette use

(1.4 packs/day) in cases compared to controls (0.7 packs/ Solar radiation is classically involved in the disease’s

day). These values are consistent with our study [3]. The pathogenesis. Lesions can be induced experimentally by

median age for starting smoking was very precocious (14 UVB and UVA radiation, and visible light. Lesions wors-

years) with a high average of 29 cigarettes/day. It repre- en in more than half the patients during summer, but in

sents an important accumulated smoking exposure that winter it can also happen in up to 10% of cases [11].

could be a disease trigger in predisposed individuals, par- Pregnancy can improve DLE lesions during the second

ticularly considering that all cases with smoking habits and third trimester and worsen them during the first tri-

developed the disease after they had started to smoke. mester and in the postpartum period, but its impact is

The pathological immune response in DLE lesions less important than in SLE [12]. Anxiety and emotional

shows a typical Th1 profile, with the predominance of factors can also precipitate lesions and induce treatment

T lymphocyte infiltrate and inflammatory cytokines: resistance. Because smoking exposure is significantly

IFN-", IL-1 and TNF-# [10]. Discoid lesions can be spon- higher in DLE patients, it was considered a risk factor in

taneous or triggered by factors such as trauma, sunburn, skin lesion development. This was especially true for

psychological stress, infections, exposure to cold or preg- heavy smokers [3].

nancy. Exacerbations often occur with sun exposure and An association with HLA-B7, B8, Cw7, DR2, DR3

traumas. Occasionally, drugs like isoniazid, penicillin, and DQw1 has been described, along with an increased

griseofulvin and dapsone can precipitate DLE lesions [2]. risk of developing the disease in certain gene combina-

Siriraj Medical Library, Mahidol University

198.143.39.97 - 1/27/2016 4:02:15 PM

120 Dermatology 2005;211:118–122 Miot/Bartoli Miot/Haddad

Downloaded by:

tions, such as HLA-Cw7, DR3, DQw1 and HLA B7, comparison of smoking prevalence of cases with these

HLA-Cw7 and DR3 [13]. historical controls will identify a stronger association be-

Familial cases are uncommon, accounting for less than tween DLE and smoking because controls in this study

4%. A documented case of monozygotic twins with DLE had higher smoking rates than Brazilian surveys.

and polymorphic light eruption suggests that genetic fac- From case-control studies, we can also estimate the

tors and somatic mutations are also involved in the dis- percentage of the population-attributable risk. Regarding

ease’s pathogenesis [14]. the prevalence of smoking in the population and the role

The age at DLE onset, male-to-female ratio, familial of smoking in DLE pathogenesis, 81.8% of DLE cases

occurrence and topographic distribution of lesions in this could have been influenced by smoking and might have

study were in accordance with the literature. However, been prevented if exposure to smoking had not existed.

this study has the first report of a significant compromise It was noted that 3 single patients who had quit smoking

in smokers’ upper arms [1]. Smoking is the most impor- showed clinical improvement in the lesions and 1 a wors-

tant environmental risk in global public health. Reduc- ening when taking up smoking again. This fact, already

tions in smoking rates would have a direct favorable im- mentioned in the literature, supports the hypothesis of

pact in more than 50 diseases [5]. Smoker prevalence is the participation of smoking in the pathogenesis of DLE

tending to reduce in populations, but even so global con- [23].

sumption is increasing. The prevalence of smokers in the This study did not evaluate the consumption of caf-

USA was 37.4% in 1970; this had been reduced to 25% feine, alcohol, analgesics or hypnotics, which have a high-

in 1993 [3]. er use among smokers and could also play a role in the

Smoking is also a risk factor associated with other in- pathogenesis of DLE. The ultraviolet exposure dose from

flammatory diseases such as SLE, with an OR of 2.3, professional exposure and outdoor activities could not be

rheumatoid arthritis (OR of 2.0), thromboangiitis oblit- isolated because of imprecise data from the participants

erans (OR of 34.8), palmar pustulosis (OR of 7.2), Crohn’s [9].

disease (OR of 3.1) and others [4, 5, 15, 16]. By the way, Another feature of this study was the lack of racial or

a recent meta-analysis found a statistical association be- phototype adjustment, because it was difficult to be pre-

tween SLE and smoking only for current smokers, but not cise about this information from the telephone interviews

former smokers [17]. with controls. We were also unable to accurately estimate

How smoking precisely affects lymphocyte inflamma- the use of any medication at the beginning of the disease.

tory activity is yet unknown. Some T lymphocytes with Nevertheless, the strong association between smoking

suppressor profiles appear to have depressed activity and DLE found in this study (OR of 14.4) reduces the

while an augmented immune activity stimulates prolif- possibility of this being a chance result or confounding

eration of peripheral T lymphocytes and B cells. Poly- interference; it suggests that smoking can represent an

clonal B cell activation is one of the theories explaining independent risk factor for DLE. The discrepancy found

autoimmune activity in SLE [3, 18]. between the unadjusted and adjusted OR was due to a

Cigarette smoke contains more than 100 organic sub- weaker prevalence of smoking among women of the con-

stances, many of them known carcinogens and toxic trol group in comparison to men.

chemicals. Also, smoke has a genotoxic effect to DNA and Some publications have highlighted an increased ther-

oxidative effects in the human body, interfering in the apy resistance in DLE, and especially a diminished re-

metabolism of prostaglandins and the vascular reactivity sponse to antimalarials in smokers, probably due to an

[18–20]. increase in drug excretion. It also seems to have a direct

It is hard to estimate the real prevalence of smoking in negative influence on disease course, over and above the

the Brazilian population. Smoking habits are influenced pharmacological interference. Therefore, cessation of

by sex, education, age and cultural, familial and social smoking could positively interfere in the progression of

aspects. The choice of more than one control for each case DLE, leading patients to less toxic and less expensive

was aimed at increasing statistical power and lowering treatments [9, 7, 24].

sampling errors to reduce the chances of selection bias, as These findings can also reinforce an opportunity for

smoking has so many external influences [7]. health education against smoking. Early exposure to to-

In 1989, 26% of Brazilian women and 40% of men over bacco, greater disease extension in smokers, diminished

15 years old smoked. In other case-control studies in Bra- therapeutic response and the high number of cigarettes

zil, the prevalence ranged from 25 to 34% [21, 22]. The consumed are indirect evidence that smoking can influ-

Siriraj Medical Library, Mahidol University

198.143.39.97 - 1/27/2016 4:02:15 PM

Discoid Lupus erythematosus and Dermatology 2005;211:118–122 121

Cigarette Smoking

Downloaded by:

ence the course of DLE. This study detected a statistical Acknowledgements

association between cigarette smoking and DLE. New

The authors are thankful to the editor and referees for important

controlled studies are needed in order to measure how

contributions to this paper.

giving up smoking would affect the therapeutic response

and its impact on the clinical course of the disease.

References

1 Duarte AA: Lupus eritematoso cutâneo. An 9 Ayres M, Ayres M Jr, Ayres DL, dos Santos AS: 17 Costenbader KH, Kim DJ, Peerzada J, Lock-

Bras Dermatol 2001;76:655–671. Bioestat: 2.0 Aplicações estatísticas nas áreas man S, Nobles-Knight D, Petri M, Karlson

2 Rowell NR, Goodfield MJD: The connective das ciências biológicas e médicas. Belém, So- EW: Cigarette smoking and the risk of system-

tissue diseases; in Champion RH, Burton JL, ciedade Civil Mamirauá e MCT – CNPq, ic lupus erythematosus: A meta-analysis. Ar-

Burns DA, Breathnach SM (eds): Rook/Wilkin- 2000. thritis Rheum 2004;50:849–857.

son/Ebling Textbook of Dermatology. Oxford, 10 Toro JR, Finlay D, Dou X, Zheng SC, LeBoit 18 Mills CM: Cigarette smoking, cutaneous im-

Blackwell Scientific Publications, 1998, vol 3, PE, Connolly MK: Detection of type 1 cyto- munity, and inflammatory response. Clin Der-

pp 1437–1575. kines in discoid lupus erythematosus. Arch matol 1998;16:589–594.

3 Gallego H, Crutchfield CE 3rd, Lewis EJ, Gal- Dermatol 2000;136:1497–1501. 19 Alberg AJ: The influence of cigarette smoking

lego HJ: Report of an association between dis- 11 Velthuis PJ, van Weelden H, van Wichen D, on circulating concentrations of antioxidant

coid lupus erythematosus and smoking. Cutis Baart de la Faille H: Immunohistopathology of micronutrients. Toxicology 2002; 180: 121–

1999;63:231–234. light-induced skin lesions in lupus erythemato- 137.

4 Rahman M, Chowdhury AS, Fukui T, Hira K, sus. Acta Derm Venereol 1990;70:93–98. 20 Trüeb RM: Association between smoking and

Shimbo T: Association of thromboangiitis ob- 12 Shlepakov VM: Effect of gestation in the course hair loss: Another opportunity for health edu-

literans with cigarette and bidi smoking in of chronic lupus erythematosus. Soviet Med cation against smoking? Dermatology 2003;

Bangladesh: A case-control study. Int J Epide- 1969;32:111–116. 206:189–191.

miol 2000;29:266–270. 13 Knop J, Bonsmann G, Kind P, Doxiadis I, 21 Menezes AMB, Horta BL, Oliveira ALB,

5 Smith JB, Fenske NA: Cutaneous manifesta- Vogeler U, Doxiadis G, Goerz G, Grosse-Wil- Kaufmann RAC, et al: Risco de câncer de pul-

tions and consequences of smoking. J Am Acad de H: Antigens of the major histocompatibility mão, laringe e esôfago atribuível ao fumo. Rev

Dermatol 1996;34:717–732. complex in patients with chronic discoid lupus Saúde Pública 2002;36:129–134.

6 Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries JF, Masi AT, Mc- erythematosus. Br J Dermatol 1990;122:723– 22 Ministério da Saúde, Instituto Nacional de Al-

Shane DJ, Rothfield NF, Schaller JG, Talal N, 728. imentação e Nutrição (INAN): PNSN: es-

Winchester RJ: The 1982 revised criteria for 14 Wojnarowska F: Simultaneous occurrence in tatísticas sobre hábitos de fumo no Brasil. Bra-

the classification of systemic lupus erythema- identical twins of discoid lupus erythematosus sília, INAN, 1989.

tosus. Arthritis Rheum 1982;25:1271. and polymorphic light eruption. J R Soc Med 23 Jewell ML, McCauliffe DP: Patients with cu-

7 Hennekens CH, Buring JE: Epidemiology in 1983;76:791–792. taneous lupus erythematosus who smoke are

Medicine, ed 1. Boston, Little, Brown & Co, 15 Achutti A, Menezes AMB: Epidemiologia do less responsive to antimalarial treatment. J Am

1987. tabagismo; in Achutti A (ed): Guia Nacional de Acad Dermatol 2000;42:983–987.

8 Bruzzi P, Green SB, Byar DP, Brinton LA, Prevenção e Tratamento do Tabagismo. Rio de 24 Rahman P, Gladman DD, Urowitz MB: Smok-

Schairer C: Estimation of population attribut- Janeiro, Vitrô Comunicação & Editora, 2001, ing interferes with efficacy of antimalarial ther-

able risk for multiple factors using case-control pp 9–27. apy in cutaneous lupus. J Rheumatol 1998;25:

data. Am J Epidemiol 1985;122:904–914. 16 Nagata C, Fujita S, Iwata H, Kurosawa Y, Ko- 1716–1719.

bayashi K, Kobayashi M, Motegi K, Omura T,

Yamamoto M, Nose T, et al: Systemic lupus

erythematosus: A case-control epidemiologic

study in Japan. Int J Dermatol 1995;34: 333–

337.

Siriraj Medical Library, Mahidol University

198.143.39.97 - 1/27/2016 4:02:15 PM

122 Dermatology 2005;211:118–122 Miot/Bartoli Miot/Haddad

Downloaded by:

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5819)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

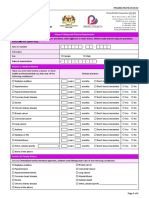

- PeKa B40 Health Screening Form 3 - First Consultation - 201902Document4 pagesPeKa B40 Health Screening Form 3 - First Consultation - 201902Ezanii ShaharuddinNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Cause and Effect EssayDocument3 pagesCause and Effect Essaykeethagurl2450% (2)

- ItcDocument57 pagesItcBhargav Jambukiya33% (3)

- Surrogate Advertisment BY Nikhil Kalra Nikhil Kumar Ghanshyam MundhraDocument18 pagesSurrogate Advertisment BY Nikhil Kalra Nikhil Kumar Ghanshyam Mundhraghanshyam100% (1)

- Smoking and Its EffectsDocument65 pagesSmoking and Its EffectsElvyn Fabellore HerreraNo ratings yet

- Research Roadmap 3.1: The Reflective StatementDocument2 pagesResearch Roadmap 3.1: The Reflective Statementmtlol17No ratings yet

- 0605Document3 pages0605iris virtudezNo ratings yet

- 2015 Grade 8 English FAL Memo PDFDocument5 pages2015 Grade 8 English FAL Memo PDFthokozile nkqezoNo ratings yet

- Smoking: Related Kidshealth LinksDocument7 pagesSmoking: Related Kidshealth LinksNLNo ratings yet

- Barangay DunaoDocument1 pageBarangay DunaoRonie ObeñaNo ratings yet

- Health 8 4th Quiz #01 Tobacco SmokingDocument4 pagesHealth 8 4th Quiz #01 Tobacco SmokingRyan BersaminNo ratings yet

- Kip W. Viscusi - Regulation Through Litigation-Aei Press, NBN (2002)Document380 pagesKip W. Viscusi - Regulation Through Litigation-Aei Press, NBN (2002)Marcella PuppioNo ratings yet

- Fear Stalks The Land!Document20 pagesFear Stalks The Land!andrew_bloomNo ratings yet

- International Management: AdibaDocument19 pagesInternational Management: AdibaAdiba SyamlanNo ratings yet

- Edexcel International GCSE Biology Hard PPQDocument14 pagesEdexcel International GCSE Biology Hard PPQTravel Unlimited100% (1)

- Sec 4 Prohibition of Smoking in Public PlacesDocument3 pagesSec 4 Prohibition of Smoking in Public Placesdokka veerarajNo ratings yet

- Bahan Ajar Genre of TextDocument112 pagesBahan Ajar Genre of Textokta anita pouwNo ratings yet

- Soal Bahasa Inggris Kelas XIIDocument7 pagesSoal Bahasa Inggris Kelas XIIDian OctavianiNo ratings yet

- From Social Taboo To "Torch of Freedom": The Marketing of Cigarettes To WomenDocument6 pagesFrom Social Taboo To "Torch of Freedom": The Marketing of Cigarettes To WomenfaithnicNo ratings yet

- Advanced - Supplementary Book (Jan 5 2018)Document325 pagesAdvanced - Supplementary Book (Jan 5 2018)pacoh75% (4)

- Final Stamped Juul ComplaintDocument66 pagesFinal Stamped Juul ComplaintGMG EditorialNo ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson Plan On Mapeh 8Document7 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan On Mapeh 8JamesNo ratings yet

- Narrative Report On Tobacco Control and Anti-Smoking: San Roque Elementary SchoolDocument4 pagesNarrative Report On Tobacco Control and Anti-Smoking: San Roque Elementary SchoolLoriefy Dela Cruz0% (1)

- J.K. Hospital, Dadra Presents: Dr. Ravi TiwariDocument23 pagesJ.K. Hospital, Dadra Presents: Dr. Ravi Tiwarib_manthanNo ratings yet

- Tugas 1Document3 pagesTugas 1Suci Novira Aditiani0% (1)

- 3 Charged in Beating of Mayor: He Imes EaderDocument48 pages3 Charged in Beating of Mayor: He Imes EaderThe Times LeaderNo ratings yet

- DLL - Fourth GradingDocument5 pagesDLL - Fourth GradingMeek Adan RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Provocation & MovementDocument38 pagesProvocation & MovementAashish SinghalNo ratings yet

- Dangers of SmokingDocument4 pagesDangers of SmokingNhiyar Indah HasniarNo ratings yet