Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Review: Kjell Tullus, Hazel Webb, Arvind Bagga

Review: Kjell Tullus, Hazel Webb, Arvind Bagga

Uploaded by

Anonymous G20oAbl6p8Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Review: Kjell Tullus, Hazel Webb, Arvind Bagga

Review: Kjell Tullus, Hazel Webb, Arvind Bagga

Uploaded by

Anonymous G20oAbl6p8Copyright:

Available Formats

Review

Management of steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome in

children and adolescents

Kjell Tullus, Hazel Webb, Arvind Bagga

More than 85% of children and adolescents (majority between 1–12 years old) with idiopathic nephrotic syndrome Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2018

show complete remission of proteinuria following daily treatment with corticosteroids. Patients who do not show Published Online

remission after 4 weeks’ treatment with daily prednisolone are considered to have steroid-resistant nephrotic October 17, 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

syndrome (SRNS). Renal histology in most patients shows presence of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, minimal

S2352-4642(18)30283-9

change disease, and (rarely) mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis. A third of patients with SRNS show mutations

Nephrology Unit, Great

in one of the key podocyte genes. The remaining cases of SRNS are probably caused by an undefined circulating Ormond Street Hospital for

factor. Treatment with calcineurin inhibitors (ciclosporin and tacrolimus) is the standard of care for patients with Children, Great Ormond Street,

non-genetic SRNS, and approximately 70% of patients achieve a complete or partial remission and show satisfactory London, UK (K Tullus MD,

H Webb BSc) and Division of

long-term outcome. Additional treatment with drugs that inhibit the renin–angiotensin axis is recommended for

Nephrology, Indian Council of

hypertension and for reducing remaining proteinuria. Patients with SRNS who do not respond to treatment with Medical Research Advanced

calcineurin inhibitors or other immunosuppressive drugs can show declining kidney function and are at risk for end- Center for Research in

stage renal failure. Approximately a third of those who undergo renal transplantation show recurrent focal segmental Nephrology, All India Institute

of Medical Sciences, New Delhi,

glomerulosclerosis in the allograft and often respond to combined treatment with plasma exchange, rituximab, and

India (Prof A Bagga MD)

intensified immunosuppression.

Correspondence to:

Dr Kjell Tullus, Nephrology Unit,

Introduction prednisolone at a dose of 60 mg/m² daily for 4 weeks. Great Ormond Street Hospital for

Nephrotic syndrome is diagnosed based on a triad of Others recommend treatment for 8 weeks.2–4 Several Children, Great Ormond Street,

London WC1N 3JH, UK

symptoms: severe proteinuria (>1 g/m² per day), centres, including the Great Ormond Street Hospital for

kjell.tullus@gosh.nhs.uk

hypoalbuminaemia (albumin <2·5 g/dL), and oedema. Children, London, UK, administer three intra venous

Most children older than 1 year (generally until 12 years pulses of methylprednisolone (500 mg/m²) before

old) are diagnosed with idiopathic nephrotic syndrome regarding patients as resistant.5 Steroid resistance most

based on these features and little else. A secondary cause often occurs during initial treatment with prednisolone

(eg, systemic lupus erythematosus and Henoch- (initial resistance), but can also occur during treatment

Schönlein purpura) is rare. for a relapse, in a patient who had previously responded

Idiopathic nephrotic syndrome presents as an acute to treatment with steroids or with a second-line drug

disease, with substantial proteinuria and increasing (late resistance). Steroid resistance is an important deter

oedema. A smaller proportion of patients have a slower minant of future risk for end-stage renal disease.

and more atypical onset, sometimes over several months

or even years. Atypical features include onset in infancy

or adolescence, symptoms suggestive of an inflam Key messages

matory kidney disease, renal failure, hypertension, and • About 10–15% of children with idiopathic nephrotic syndrome who do not show

macroscopic haematuria. complete remission of proteinuria following 4 weeks’ treatment with corticosteroids

More than 85% of patients with idiopathic nephrotic are considered to have steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome

syndrome respond (ie, complete remission of proteinuria • For 30% of patients with steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome, the condition results

and normal serum albumin) following treatment with from a genetic cause; for the remainder, the disease is probably caused by a circulating

prednisolone.1 Response to prednisolone is an important factor

prognostic indicator for survival of kidney function. • Renal histology shows minimal change disease and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis

Although many patients with steroid-sensitive nephrotic (FSGS) in most patients

syndrome have frequent relapses or steroid dependence, • Approximately 50–70% of patients with steroid resistance show complete or partial

the long-term outlook for kidney function is favourable. remission following treatment with a calcineurin inhibitor (either ciclosporin or

The main long-term problem in these patients is the risk tacrolimus)

of side-effects from prolonged treatment with cortico • Although additional treatment with mycophenolate mofetil or rituximab is

steroids and other immunosuppressive medications. considered in children who are resistant to treatment with steroids and calcineurin

Patients who do not respond to prednisolone are inhibitors, their efficacy to induce remission is low

considered to have steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome • Patients with a genetic FSGS or those who do not show complete or partial remission

(SRNS). The medical community has not yet reached a following treatment with calcineurin inhibitors have high risk of end-stage renal failure

consensus regarding the length of time prednisolone • Patients with late resistance and absence of a genetic cause show high risk of recurrent

should be given before regarding a patient as steroid FSGS in the renal allograft

resistant. We recommend that steroid resistance should • Intensification of treatment with ciclosporin or tacrolimus, and combined treatment

be considered in patients who do not show complete with rituximab and plasma exchange might prevent or treat recurrent FSGS effectively

remission of proteinuria despite treatment with

www.thelancet.com/child-adolescent Published online October 17, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30283-9 1

Review

Congenital nephrotic syndrome refers to infants with slit diaphragm (NPHS1, NPHS2, CD2AP, and PLCE1);

onset of nephrotic syndrome before 3 months of age. cytoskeleton (ACTN4, MHY9, MYO1E, INF2, and actin

Most of these patients have mutations involving the regulatory genes); glomerular basement membrane and

podocyte proteins (nephrin, podocin, and WT1) and do matrix proteins (LAMB2, ITGA3, and COL4A3–5);

not respond to treatment with steroids and other mitochondrial proteins (COQ2, COQ6, and ADCK4);

medications. The course of illness is progressive and nuclear proteins (WT1, LMX1B, NUP93, NUP107,

most patients require renal replacement treatment in the NUP205, and SMARCAL1); and other intracellular

first decade. We have not included the clinical manage proteins (TRPC6, SCARB2, APOL1, DGKE, CUBN,

ment of these children in this Review. and GAPVD1) with a wide spectrum of illness.

Nephrotic syndrome might also be associated with

Cause of SRNS syndromic features with mutations in specific genes—

Genetic causes eg, Denys-Drash syndrome and Frasier syndrome (WT1);

The medical community has learnt much about the Pierson syndrome (LAMB2); nail-patella syndrome

genetic causes for SRNS over the past decades. Mutations (LMX1B); Epstein syndrome, Sebastian syndrome, and

in more than 70 genes encoding key podocyte proteins related illnesses (MYH9); MELAS syndrome and Leigh

are recognised to cause the illness. Despite recognition syndrome (mitochondrial genes); Galloway-Mowat syn

of an increasing number of genetic causes, only drome (WDR73); and Schimke dysplasia (SMARCAL1),

30% of patients with sporadic SRNS show a defined as reviewed by Bierzynska and colleagues6 and Preston

mutation.6 and colleagues.7

Genes associated with the occurrence of SRNS are

broadly classified as involving: structural elements of the Circulating factor

The probable cause for most patients with non-genetic

SRNS is thought to be a circulating factor.8,9 Circum

A

stantial evidence exists that makes this theory quite

probable, but it has been elusive to define the circulating

factors responsible for SRNS.10 A large proportion of

children with non-genetic SRNS relapse quickly after

kidney transplantation: these patients often respond to

plasma exchange or immune adsorption. Small animals

infused with patient plasma, whole or its fractions, also

develop proteinuria. In 1975, a vascular permeability

factor was described.11 Other important suggestions of

circulating factors include haemopexin, interleukin-13,

cardiotrophin-like cytokine-1, and soluble urokinase-type

plasminogen activator receptor.12–15 None of these sug

gested factors have been confirmed by independent

research groups so far.

B

Kidney biopsy

Renal histology is an important tool for diagnostic and

prognostic categorisation. Biopsies should be examined

by light, immunofluorescence, and electron microscopy

to define their histological features. An adequate biopsy

should have approximately 25 glomeruli, especially when

evaluating lesions that are focal or segmental. Biopsies

with fewer glomeruli have low diagnostic accuracy.

Common histological diagnoses include focal seg

mental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) in 35–55% of patients,

minimal change disease in 25–40% of patients, and

idiopathic mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis in

10–15% of patients (figure 1).16 In about 20% of patients,

the histology shows membranous nephropathy,

Figure 1: Kidney biopsy images of patients with SRNS immunoglobulin A nephropathy, or proliferative glome

(A) Glomerulus in minimal change disease appear normal on light microscopy. rulonephritis. We do not discuss their management in

Tubules and interstitium are normal. Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E),

magnification 40×. (B) Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Segmental sclerosis

this Review.

is noted in a perihilar location with hyalinosis. Evidence of tubular atrophy and Data from the 21-nation multiethnic PodoNet Registry

interstitial fibrosis is also present. H&E, magnification 20 ×. have provided important information on the course and

2 www.thelancet.com/child-adolescent Published online October 17, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30283-9

Review

outcome of a large cohort of children with SRNS.4

Clinical features were similar in patients with minimal Panel 1: Clinical tests for children with steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome

change disease, FSGS, and mesangioproliferative glome Main tests

rulonephritis. Repeat biopsies, in 171 patients, found that • Blood creatinine, electrolytes, protein, albumin, transaminases

the diagnosis changed from minimal change disease to • Full blood count

FSGS in 26 of 47 (55%) cases, and from mesangio • 24 h urine protein excretion, spot urine protein to creatinine ratio (or albumin to

proliferative glomerulonephritis to FSGS in 16 of 33 creatinine ratio)

(48%) cases.4 • Varicella antibody status, measles immunoglobulin G (if no history of the measles,

Patients with SRNS mostly require treatment with mumps, and rubella vaccination)

calcineurin inhibitors that can cause nephrotoxicity,

which is characterised histologically by microvascular Additional tests

ischaemia and striped interstitial fibrosis.17 • Streptococcal antibodies, complement C3, C4 (if suspected lupus nephritis)

• Antinuclear antibody, anti-double stranded DNA antibody (if suspected lupus

Evaluation nephritis)

Treatment of SRNS should start with a re-evaluation of • Hepatitis C and B serology, HIV antibody

the diagnosis. Does the child have idiopathic nephrotic • Kidney biopsy: light, immunofluorescence, and electron microscopy

syndrome with a probable biopsy diagnosis of minimal Genetic studies (targeted exome sequencing) indications

change disease or FSGS, or are there atypical features? • Congenital (onset<3 months of age), infantile-onset nephrotic syndrome, family

Evaluation should include a detailed investigation of history of steroid resistance, suspected syndromic forms, resistance to calcineurin

current metabolic status and an underlying cause inhibitors, and before transplantation

(eg, proliferative glomerulonephritis; panel 1). Patients

require regular monitoring for severity of proteinuria

and blood concentrations of creatinine and albumin. Child with typical nephrotic syndrome:

Experts recommend a renal biopsy in all patients to treatment with prednisolone for 4 weeks

counsel parents and guide treatment. Screening for

variations in known genes for SRNS is important,

especially in infants with initial resistance, familial or

Remission achieved No response:

syndromic FSGS, non-response to treatment with start CNI—aim to treat for

calcineurin inhibitors, and before transplantation. 3–6 months and send genetic screen

(for primary steroid resistant)

Treatment

Although the aim of treatment in SRNS is the Manage as steroid-sensitive Response to CNI: complete No response to CNI

achievement of complete remission, the occurrence of nephrotic syndrome remission

even partial remission is satisfactory.18,19 Complete

remission is defined as presence of trace or negative

proteinuria (by dipstick) or spot urine protein to

Genetic screen negative: Genetic screen positive: consider

creatinine ratio less than 0·2. Patients are considered to consider adding in MMF or stopping immunosuppression

be in partial remission if they show proteinuria level of rituximab

1–2+ (urine protein:urine creatinine from 0·2–2), serum

albumin more than 2·5 g/dL, and no oedema. Persistence

Remission achieved: No response to increased High chance of development of

of 3–4+ proteinuria (urine protein:urine creatinine more decreased chance of develop- immunosuppression ESRD: consider supportive

than 2), albumin less than 2·5 g/dL, or oedema ment of ESRD and high chance measures

of relapse

constitutes non-response.

Calcineurin inhibitors (ciclosporin and tacrolimus)

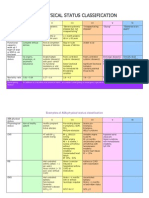

with low-dose prednisolone are recommended as the Figure 2: Flow chart schematically outlining clinical management for a child with steroid-resistant nephrotic

syndrome

main treatment for children with SRNS (figure 2). CNI=calcineurin inhibitor. MMF=mycophenolate mofetil. ESRD=end-stage renal disease.

Evidence-based role for treatment with other drugs,

including cyclophosphamide, myco phenolate mofetil,

and rituximab, is scarce. The optimal duration of occurrence of partial remission following treatment,

treatment with calcineurin inhibitors is not clear. most experts do not recommend that patients with a

Guidelines from Kidney Disease Improving Global confirmed mutation in podocyte genes receive

Outcomes recommend a minimum duration of immunosuppressive medications.19

12 months;2 in practice, treatment is often continued for

24–36 months. Calcineurin inhibitors

The question whether children with a proven genetic Although the immunosuppressive effect of calcineurin

cause should receive immunosuppressive treatment is inhibitors is through inhibition of T lymphocytes, a

being debated. Although anecdotal reports suggest direct effect of ciclosporin on the podocyte actin

www.thelancet.com/child-adolescent Published online October 17, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30283-9 3

Review

Dose Monitoring Side-effects

Tacrolimus 0·05–0·1 mg/kg in two divided doses Drug concentrations, creatinine Nephrotoxicity, hypertension, hyperglycaemia,

orally; trough 4–8 ng/mL electrolytes, glucose, seizures, diarrhoea, hypomagnesemia

transaminases

Ciclosporin 4–6 mg/kg per day in two divided doses Drug concentrations, creatinine Nephrotoxicity, hypertension, hypertrichosis,

orally; trough 80–150 ng/mL electrolytes, glucose, gingival hyperplasia

transaminases

Mycophenolate 600 mg/m² in two divided doses orally; Area under the curve Abdominal pain, diarrhoea, anorexia. Leucopenia

mofetil* maximum dose 1200 mg/m² measurements, full blood counts, and raised transaminases are uncommon

creatinine, transaminases

Cyclophosphamide† 500–750 mg/m² intravenously every month Blood counts Alopecia, marrow suppression, vomiting,

for 6 months; coadministration with sodium haemorrhagic cystitis, risk of systemic infections.

mercaptoethane sulphonate, and Long-term risks: cancer, infertility

ondansetron

Rituximab* 375–750 mg/m² (maximum 1000 mg) Hepatitis B screen, CD19 count, Monitoring of allergic reactions during infusion,

intravenously; 2–4 infusions, 1–2 weeks apart full blood count immunosuppression, risk of infections

Enalapril and 0·2–0·5 mg/kg per day for enalapril Creatinine, electrolytes, caution if Dry cough, hyperkalaemia, hypotension, anaemia,

ramipril and 1·25–6 mg/m² per day for ramipril hypovolaemia or hypotension nephrotoxicity

Drugs options are combined with alternate day prednisolone: 1·5 mg/kg on alternate days for 2–4 weeks, 1·25 mg/kg in the subsequent 2–4 weeks, 1 mg/kg for 3 months,

and 0·5–0·75 mg/kg for 9–12 months. *Scarce evidence for efficacy of these drugs. †Oral cyclophosphamide is not recommended for steroid resistance. Intravenous

cyclophosphamide limited to centres where cost is a major factor.

Table 1: Available drug options for the treatment of steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome

cytoskeleton has been suggested.20 Several prospective of cytochrome P450, respectively. The main CYP3A

studies have been done with calcineurin inhibitors for inhibitors are azoles (fluconazole, ketoconazole, and

patients with SRNS. Treatment with ciclosporin has been voriconazole), calcium channel blockers (diltiazem

shown to be effective in inducing complete or partial hydrochloride and verapamil hydrochloride), protease

remission in placebo-controlled studies, and in com inhibitors (ritonavir, saquinavir, and indinavir sulphate),

parison with intravenous cyclo phosph amide.21 A macrolides (clarithromycin and erythromycin), and grape

randomised controlled trial of 131 children with SRNS fruit and pomegranate juices. Clinically effective inducers

compared the efficacy of 12-month treatment with of the enzymatic pathway are rifampicin, rifabutin,

tacrolimus with six intravenous pulses of cyclophosph phenytoin, phenobarbital, and some non-nucleoside

amide.22 Complete remission was reported in 33 of 63 reverse transcriptase inhibitors (efavirenz and nevirapine).

(52%) patients receiving tacrolimus and in 9 of 51 (18%) Therapeutic monitoring of calcineurin inhibitor concen

patients receiving cyclophosphamide. Respective partial tration is necessary in patients receiving concomitant

responses were 19 of 63 (30%) and 19 of 61 (31%). treatment with these drugs.

Another trial, funded by the US National Institutes of The most important side-effect of calcineurin inhibitors

Health (NIH), showed a 46% combined complete and is the potential risk on long-term renal function.

partial response with ciclosporin.18 Although the medical community has not reached a

The probability of complete or partial response to consensus on the duration of treatment, most experts

treatment with calcineurin inhibitors is similar in consider weaning off calcineurin inhibitors after

patients with minimal change disease (46·5%), 2–3 years.2,27 The risk of relapse on stopping treatment is

mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis (38·0%), and high, but some children can be weaned off the medication

FSGS (39·0%).4,19 Although most patients with SRNS and maintain remission. Treatment with a calcineurin

who respond to treatment stay in remission, relapses are inhibitor increases the risk of acute kidney injury,

not uncommon. Most of these relapses respond to particularly if the child is depleted intravascularly.

addition of daily corticosteroid treatment (table 1). Temporary discontinuation of treatment could be

Therapies with tacrolimus and ciclosporin show similar considered during such episodes. Cosmetic side-effects,

efficacy.23 Treatment with tacrolimus might be preferred including hypertrichosis and gingival hyperplasia,

because of lower risk of relapses and fewer side-effects.24 are common with ciclosporin. Glucose intolerance and

12 hour trough levels are used for monitoring treatment diarrhoea are potential risks with tacrolimus. Both

with ciclosporin and tacrolimus; target levels vary between medications have a small risk of neurotoxicity, mani

80–150 ng/mL for ciclosporin and 4–8 ng/mL for festing with headache and occasional seizures.

tacrolimus.24–26 Calcineurin inhibitors are metabolised by

cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYP3A). Therefore, their Mycophenolate mofetil

concentrations are affected by inhibitors or inducers of Mycophenolate mofetil, which works by selective in

this pathway, resulting in increased or reduced amounts hibition of DNA replication in T and B lymphocytes, is

4 www.thelancet.com/child-adolescent Published online October 17, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30283-9

Review

considered less effective than calcineurin inhibitors.23,26 especially in patients with minimal change disease.19 A

However, an NIH trial in children and adults (<40 years of review of data from multiple case series shows that

age) with steroid-resistant FSGS did not show a statistically treatment with intravenous cyclophosphamide results in

significant difference in treatment response between the complete and partial remission in 30–35% of patients.22,27

combination of oral dexamethasone and mycophenolate Cyclophosphamide can result in severe side-effects,

mofetil compared with ciclosporin.18 A report by Sinha including haemorrhagic cystitis, bone marrow depres

and colleagues26 showed that an early switch (at 6 months) sion with leucopenia, and alopecia. The risk of azo

from tacrolimus to mycophenolate mofetil was not ospermia is higher in pubertal than pre-pubertal boys

effective in sustaining remission in patients with SRNS. and is related to cumulative exposure to the drug; the risk

Studies in paediatric transplant recipients suggest the of female infertility is lower than for male patients.36 The

importance of measuring area under the curve dose of intravenous cyclophosphamide used for SRNS is

(mycophenolic acid concentration over time) for considerably lower than that associated with infertility.

monitoring treatment with mycophenolate mofetil.28 The

proposed area under the curve measurement for patients Rituximab

with steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome is between Rituximab, a monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody, is standard

30 mg/h per litre and 60 mg/h per litre.29 Information on treatment for children with frequently relapsing or

target blood concentrations of mycophenolate mofetil for steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome, particularly

patients with SRNS is scarce, and possibly targeting when other immunosuppressive drugs have not achieved

higher concentrations than those currently in clinical longstanding full remission.37–39 Apart from action on

practice might be associated with better response to lymphocytes, rituximab might have off-target effects

mycophenolate mofetil treatment. The side-effect profile on lipid metabolism in podocytes by binding to

of mycophenolate mofetil makes it preferable to sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase acid-like 3b protein

calcineurin inhibitors, since mycophenolate mofetil does and regulating acid sphingomyelinase activity. The first

not have adverse effects on renal function. Gastro children with SRNS to be treated with rituximab were

intestinal disturbances are important; leucopenia and reported by Bagga and colleagues,37 in 2007. Three patients

other adverse effects are less common. had a complete response and two had a partial response.

Patients who do not show remission following treat Further case series confirmed these findings, but the

ment with calcineurin inhibitors pose a great challenge overall response to treatment was less impressive.39,40 An

for management of SRNS. Few reports suggest that the international cohort of 27 children showed response in

combined use of calcineurin inhibitors, mycophenolate 18 patients (67%), but only six patients had complete

mofetil, and prednisone might be effective in inducing response.41 Similar figures were found in other reports,

partial or complete remission in a small proportion with complete remission in 27% and 29% of patients.25,42

of these patients.30,31 However, the intense immuno The first, and to our knowledge only, randomised,

suppression associated with combined treatment could controlled study in children with SRNS included

predispose patients to serious infectious complications. 31 patients who were non-responsive to calcineurin

inhibitors and steroids. All patients continued pred

Cyclophosphamide nisolone and the calcineurin inhibitors, whereas 16 also

Cyclophosphamide, an alkylating agent, has been widely received two doses (375 mg/m²) of rituximab. No

used in patients with steroid-sensitive nephrotic syn statistically significant reduction of proteinuria was

drome. Early studies in SRNS did not show benefit with measured at 3 months.43 Despite limitations, many

use of oral cyclophosphamide and steroids com pared paediatric nephrology centres use intravenous rituximab

with treatment with steroids only.32,33 Therefore, oral in selected patients of steroid and calcineurin inhibitors-

cyclo

phosphamide is not recommended for manage resistant nephrotic syndrome. The dose and frequency

ment of SRNS.2,26 of administration is not defined. A range of doses

An aggressive regime, proposed by Tune and Mendoza,34 from 375 mg/m² (single dose) to 750 mg/m² per dose

combined multiple pulses of intravenous methylpredni (two doses given 7–14 days apart) are used.44

solone (30 mg/kg per dose, initially given every other day, Rituximab is well tolerated but might cause infusion

and then tapered to weekly and monthly dosing), oral reactions of varying severity.45 These reactions can be

prednisone (2 mg/kg every other day), and oral cyclo controlled by premedication with steroids and anti

phosphamide. The efficacy of this protocol was variable, histamines, and reduced rate of infusion. Bone marrow

with remission varying from 20–50%. These regimens suppression with neutropenia has been described.46

have substantial adverse events and are not recommended. The risks for prolonged hypogammaglobulinaemia are

Intravenous cyclophosphamide is more effective than controversial and, although monitoring blood concen

oral treatment,35 and due to its low cost is still used in tration of immunoglobulins has been suggested, most

resource-limited countries. Treatment involves six-dose centres do not administer intravenous immunoglobulins,

treatment with intravenous cyclophosphamide (once a even if they find low immunoglobulin concentrations in

month) and tapering alternate day prednisolone, the blood.47

www.thelancet.com/child-adolescent Published online October 17, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30283-9 5

Review

or prevent glomerular fibrosis (inhibitors of transforming

Trial Study design and indication

growth factor β, fresolimumab, microRNA, pirfenidone,

NCT02592798 Safety and efficacy of abatacept (every 28 days Phase 2 placebo-controlled; minimal rosiglitazone, pioglitazone hydrochloride, and paclitaxel).54

for four cycles) in steroid-resistant and change disease, FSGS

calcineurin-resistant illness (adults and Some of these strategies are being examined

children 6–17 years) prospectively in phase 1–4 studies (table 2). However,

NCT02394106 Ofatumumab in steroid-resistant and Phase 2, double-blind, placebo-controlled; none of these drugs are currently recommended for

calcineurin inhibitor-resistant nephrotic minimal change disease, FSGS, treatment of patients with SRNS.

syndrome (children 2–18 years) mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis

NCT02382874 Adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells Phase 1 open label pilot study on safey

(children 2–14 years) and efficacy; multiresistant FSGS

Ofatumumab

The first use of ofatumumab, a humanised anti-CD20

NCT00098020 Efficacy of 6 months’ therapy with isotretinoin Phase 2 open label pilot study on safey

(children ≥16 years and adults) with resistant and efficacy; minimal change disease, monoclonal antibody, was reported in five children who

nephrotic syndrome FSGS, HIV-associated disease were resistant to cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate

mofetil, calcineurin inhibitors, and rituximab.55 The

FSGS=focal segmental glomerulosclerosis.

results were exceptionally positive with all patients going

Table 2: Ongoing clinical trials of steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome in children and adolescents into remission with normal blood concentration of

albumin 6-weeks after treatment. Two other studies that

reported on nine children have shown that four patients

A small but increased risk of viral infections is present achieved complete remission, two had partial remission,

after rituximab treatment. Cerebral infections with two did not respond, and one patient had a severe

JC virus have been described in adult patients and also infusion reaction.56,57

reactivation of hepatitis B.48,49 A severe respiratory illness,

rituximab-associated lung injury, develops in a very small Abatacept

group of children.50 Infections with Pneumocystis jiroveci Abatacept (cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen

have also been reported.51 Previous treatment can result 4-immunoglobulin fusion protein, CTLA-4-Ig) is a co-

in antichimeric antibodies, which reduce the effect of stimulation inhibitor targeting B7–1 (CD80) on antigen-

rituximab and might result in anaphylactic reactions. presenting cells, including podocytes. In 2013, treatment

Rituximab-induced depletion of CD19 B cells is taken with this drug was reported to induce partial or total

as a sign of effective treatment and usually lasts for remission in four patients with recurrent and one with

6–8 months.52 Data from most studies suggest that primary FSGS.58 The authors also showed that abatacept

relapses of nephrotic syndrome are uncommon in stabilises β1-integrin activation in podocytes in vitro,

patients with B lymphocyte depletion. Therapeutic reducing proteinuria in patients with B7–1-positive

response does, however, last several months, even after glomerular disease. These findings have not been

repopulation of B cells.42 Recent data also suggest that replicated in other patients treated with abatacept or with

recovery of memory B cells might predict the occurrence belatacept, a drug that binds B7–1 with even higher

of a relapse.53 affinity than abatacept.59,60

Although treatment with calcineurin inhibitors is

effective in most patients with SRNS, the precise duration Adrenocorticotropic hormone

of treatment is not defined. Also, a few patients continue to Administration of adrenocorticotropic hormone was one

relapse while on treatment with calcineurin inhibitors and of the first therapies for nephrotic syndrome.61 Since

show features of steroid or calcineurin inhibitor toxicity. clinical and experimental evidence suggested that

Treatment with two doses of rituximab has been shown to adrenocorticotropic hormone has antiproteinuric, lipid-

enable weaning off treatment with calcineurin inhibitors lowering, and renoprotective properties,62 the drug was

and prednisolone. A report from Ito and colleagues39 reintroduced as treatment for nephrotic syndrome.

showed that treatment with rituximab resulted in a Hogan and colleagues63 treated 24 adult patients with

71% reduction in relapse, with withdrawal of calcineurin steroid-resistant or steroid-dependent FSGS with adreno

inhibitors in 95% and corticosteroids in 74% patients. corticotropic hormone and achieved remission in seven

More information is required regarding the frequency of (29%) patients. Adrenocorticotropic hormone is proposed

redosing and potential long-term toxicities. to have actions beyond those of corticosteroids via anti-

inflammatory mechanisms, or directly on podocytes via

Other treatments the melanocortin receptor.62,64

The treatment of steroid-resistant and calcineurin

inhibitor-resistant nephrotic syndrome is challenging. Adalimumab

Newer drugs are available that target immune-mediated Since tumour necrosis factor is upregulated in human

inflammation and glomerular damage (ofatumumab, and experimental models of FSGS, monoclonal

adrenocorticotropic hormone, abatacept, adalimumab, antibodies have been used to inhibit this pathway.65 In a

and saquinavir); inhibit action of permeability factors phase 1 trial on novel therapies for resistant FSGS

(galactose and inhibitors of soluble urokinase receptor); (FONT), adalimumab was well tolerated, and after

6 www.thelancet.com/child-adolescent Published online October 17, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30283-9

Review

16 months of follow-up, four of ten patients showed of proteinuria by approximately 15%. However, patients

stable kidney function and reduced proteinuria.66 Studies receiving dual treatment are at risk of hypotension,

are required to confirm the benefits of adalimumab in hyperkalaemia, and impaired kidney function; therefore,

slowing the progression of FSGS. the combination is not recommended.74 The DUET

study,75 which concluded in 2017, showed that sparsentan,

Lipoprotein apheresis a novel drug with dual blockade of the angiotensin II

11 children with steroid-resistant and ciclosporin- receptor and endothelin 1, was more efficient than

resistant nephrotic syndrome were treated with irbesartan in decreasing proteinuria in SRNS.

lipoprotein apheresis three times per week, for 3 weeks,

and then once a week for 6 weeks. Prednisone was given Infection prophylaxis

at a dose of 1 mg/kg per day during the last 6 weeks and Children with SRNS have increased risk of infections,

then tapered.67 Five of these children had complete due to urinary loss of immunoglobulins and effect of

remission and two had partial remission. Those children immunosuppressive treatment. An important compli

with complete response showed normal kidney function cation is spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, often caused

during a median follow-up of 4·4 (range 4·0–11·1) years, by Streptococcus pneumoniae or by gram-negative bacteria.

whereas patients with partial and no response progressed Although few paediatric nephrology centres advocate the

to end-stage renal failure. Further studies are ongoing to use of prophylactic oral penicillin, most do not follow

determine the efficacy of this treatment. this practice.68 All patients with SRNS should receive the

pneumococcal vaccine.

Symptomatic treatment Viral infections, especially varicella zoster virus, can be

A comprehensive review on symptomatic treatments for a serious problem in immunocompromised patients.68 If

children with SNRS was published in 2016.68 a child has substantial exposure to chickenpox (within

the preceding 48 h of appearance of rash), immunity

Oedema against varicella should be checked. If not immune,

Oedema is a cardinal feature of nephrotic syndrome and varicella zoster immunoglobulin is given as soon as

often a debilitating symptom. A bodyweight increase by possible, but up to 10 days after exposure. Confirmed

25% from the baseline (before treatment) is not unusual chickenpox while on prednisolone or immunosuppressive

in children with nephrotic syndrome. However, a treatment, or within 3 months of stopping, should be

relatively large group of children show only mild oedema, treated with acyclovir for 7 days. Intravenous treatment is

despite having chronically low concentrations of serum considered in all patients, especially if unwell, and

albumin, sometimes below 10 g/L. usually for at least the first 48 h of treatment.

Initial treatment consists of restriction of intake of

sodium and of fluids to two-thirds of maintenance.69 Thrombosis

Careful use of diuretics including furosemide, meto Children with ongoing nephrotic syndrome have an

lazone, and spironolactone is helpful.70 Many children with increased risk of both venous and arterial thrombosis.

active nephrotic syndrome have a loss of fluid from the Prophylactic aspirin is advised, but is not widely used.68

vascular compartment to the extracellular space and have Physicians should have a high index of suspicion for

low intravascular volume. Aggressive diuretic treatment in thrombosis. Prompt evaluation and treatment with

these patients carries a risk of hypovolaemia and acute heparin followed by oral anticoagulants is recommended.

kidney injury.71 Despite conservative management, a small

group of children continue to have substantial oedema Hyperlipidaemia

resulting in discomfort. These children need repeated Patients with SRNS often show markedly raised blood

infusions of human albumin together with intravenous concentrations of cholesterol and triglycerides.76 The

furosemide. abnormal lipid profile might contribute to later

cardiovascular morbidity. Adult patients with nephrotic

Residual proteinuria syndrome are treated with statins, with satisfactory

Children with SRNS who show partial or no response to improvement of lipid concentrations. Treatment with

calcineurin inhibitors continue to show proteinuria. statins is not routinely used in children with SRNS and

Studies in adults, as well as children, show that treatment prospective studies are required.77

with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors

reduces the degree of proteinuria by 30–40% in a Vitamin D

dose-dependent and time-dependent manner and, Children with SRNS have urinary losses of

thus, is recommended.72,73 Angiotensin receptor blockers vitamin D-binding protein, which might lead to reduced

(valsartan and irbesartan) are advised for patients bone density and increased risk of fractures. A study on

showing adverse effects to ACE inhibitors, mainly cough. supplementation with vitamin D and calcium did not

Combined treatment with an ACE inhibitor and show any benefits on bone mineral density, but did show

angiotensin receptor blocker results in further reduction an increase in the risk of hypercalciuria.78

www.thelancet.com/child-adolescent Published online October 17, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30283-9 7

Review

Results from various case series show that almost

Panel 2: Prevention and management of recurrent focal segmental 30–50% patients with idiopathic SRNS with end-stage

glomerulosclerosis after kidney transplantation kidney disease who receive an allograft can develop

Prevention of recurrence recurrent FSGS. Patients with recurrent FSGS are at risk

• Ensure period of normalised serum albumin before transplantation of delayed graft function and graft loss, approaching

• Genetic screening of recipient if living-related donor 30–50% at 5 years.80 Although the pathogenesis is

• Intravenous rituximab (375 mg/m²; one or two doses) 2 weeks before transplantation unclear, disease recurrence is attributed to circulating

• Plasma exchanges (begin 7–10 days before transplantation) permeability factors. Recurrent proteinuria occurs from

• Induction with intravenous methylprednisolone and basiliximab; hours to days after the transplant, and is associated with

triple immunosuppression progressive hypoalbuminaemia and effacement of

• Post-transplantation proteinuria screen: daily for 1 week; weekly for 4 weeks; podocyte foot process under electron microscopy.

every 3 months for first year; and every 6 months thereafter Features associated with increased risk of recurrent

FSGS include onset of disease before 15 years of age,

Treatments for recurrence non-genetic (immune) form of the disease, mesangial

• Plasma exchange (8–12 sessions for response; might require long-term for maintenance proliferation on renal biopsy, and rapid progression to

of remission; 1–1·5 volume exchanges) on alternate days for 7–10 sessions, then taper end-stage kidney disease.81,82

and continue until proteinuria subsides A report on 150 patients with nephrotic syndrome who

• Methylprednisolone (10–15 mg/kg intravenously, three doses daily) underwent renal transplantation showed that the risk of

• Switch to high-dose ciclosporin, targeting trough concentrations of 250–300 ng/mL recurrence was highest (26 of 28, 93%) in patients who

for 2–3 weeks; alternatively, continue tacrolimus at higher dose were initially corticosteroid responsive, but showed late

• Rituximab (1–6 doses used; early use and normal serum albumin at onset predict resistance; intermediate (26 of 86, 30%) in those with

response): 375 mg/m², two doses 1 week apart; avoid plasma exchange for 36 h initial resistance, but no known mutations; and none in

following treatment; monitor CD19 depletion those with mutations affecting key podocyte genes.83 A

• Other treatments (considered for refractory patients; variable efficacy): low-density panel of antibodies against seven glomerular antigens

lipoprotein apheresis, and oral cyclophosphamide (8–12 weeks) to replace (CD40, PTPRO, CGB5, FAS, P2RY11, SNRPB2, and

mycophenolate mofetil. APOL2) is reported to predict post-transplant FSGS

recurrence with 92% accuracy; findings of this report

need confirmation.84

Thyroid disease

Children with SRNS, especially congenital nephrotic Treatment recommendations

syndrome, lose large amounts of thyroid-binding protein All patients with FSGS who are about to undergo renal

in urine. Therefore, the amount of thyroid hormones in transplantation should be advised about the possibility of

such patients should be monitored.68 recurrence of disease. Combined treatment with

1–2 doses of rituximab and pretransplant plasmapheresis

Prognosis is likely to benefit recipients at high risk of recurrent

Children with SRNS are at risk of progressing to end- FSGS. Since rituximab is cleared from the body by

stage kidney disease. One study showed renal survival at plasma exchange, an interval of 36–48 h between rituxi

10 years to vary between 54·6% and 100%, depending on mab infusion and the exchange is recommended.85

renal histology and treatment. Important influencing Strategies for management of children with docu

factors for unsatisfactory outcome were a proven genetic mented recurrent disease are not based on randomised

cause, renal histology, response to immunosuppressive trials, but on observational reports and clinical expertise.

treatment, and duration of follow-up.79 Data from a large Typically plasma exchange or immunoadsorption in

multicentre registry showed that 10-year survival free of combination with high-dose ciclosporin (trough concen

end-stage kidney disease was 29% in patients with a trations 250–300 ng/mL for 3 weeks) and cyclophos

genetic diagnosis, 52% in those with FSGS, and 79% in phamide (2–2·5 mg/kg per day for 3 months) is used.

minimal change disease.19 The 10-year renal survival With these strategies, 70% of children with recurrent

in the group that responded to immunosuppression FSGS achieve complete or partial remission.86,87 Experts

was 94%, compared with 72% with partial remission, and have reported remission of proteinuria in 64% patients

43% with non-response to treatment.19 with the use of rituximab (2–6 doses of 375 mg/m²,

administered once every 1–2 weeks), in conjunction with

Recurrence in transplantation plasma exchange and post-trans plantation immuno

Several paediatric nephrology centres advocate nephrect suppression.88 The median time to best clinical response

omy before accepting the child for transplantation. This was 2 months (range 0·6–12·0 months). On stepwise

procedure is used to reduce the problems related to regression, normal serum albumin concentration at

continuous proteinuria, which can make the monitoring recurrence (suggesting mild FSGS) and young age

of any recurrence of the disease in the transplanted predict a favourable response to treatment.88 In a review

kidney easier. on patients with recurrent FSGS treated with rituximab

8 www.thelancet.com/child-adolescent Published online October 17, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30283-9

Review

5 Deschenes G, Vivarelli M, Peruzzi L. Variability of diagnostic

Search strategy and selection criteria criteria and treatment of idiopathic nephrotic syndrome across

European countries. Eur J Pediatr 2017; 176: 647–54.

We did multiple searches on PubMed and Cochrane over the 6 Bierzynska A, McCarthy HJ, Soderquest K, et al. Genomic and

past 10 years for studies published until Jan 1, 2018, with clinical profiling of a national nephrotic syndrome cohort advocates

a precision medicine approach to disease management.

different combinations of the search terms “nephrotic Kidney Int 2017; 91: 937–47.

syndrome”, “steroid resistant treatment”, “calcineurin 7 Preston R, Stuart HM, Lennon R. Genetic testing in

inhibitor”, “ciclosporin”, “tacrolimus”, “mycophenolate steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome: why, who, when and how?

Pediatr Nephrol 2017; published online Nov 27. DOI:10.1007/s00467-

mofetil”, “rituximab”, “outcome”, “prognosis”, “kidney 017-3838-6 (preprint).

transplantation”, and “relapse after transplantation”. Studies 8 Dogra S, Kaskel F. Steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome:

were chosen based on the quality and amount of information. a persistent challenge for pediatric nephrology. Pediatr Nephrol 2017;

32: 965–74.

Only studies published in Eglish were used. 9 Davin JC. The glomerular permeability factors in idiopathic

nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 2016; 31: 207–15.

10 Savin VJ, Sharma M, Zhou J, et al. Multiple targets for novel

infusions and plasma exchange, the 12 patients who therapy of FSGS associated with circulating permeability factor.

Biomed Res Int 2017; 2017: 6232616.

achieved remission had received the infusions statistically 11 Lagrue G, Branellec A, Blanc C, et al. A vascular permeability factor

significantly earlier than the 13 patients who did not in lymphocyte culture supernants from patients with nephrotic

respond (mean 100·5 days [SD 95·4] from onset of syndrome. II. Pharmacological and physicochemical properties.

Biomedicine 1975; 23: 73–75.

recurrence vs 468·1 days [379·8]).89 A systematic review of 12 Konigshausen E, Sellin L. Circulating permeability factors in

423 patients with recurrent FSGS showed that patients primary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: a review of proposed

treated with prompt plasma exchanges within 2 weeks of candidates. Biomed Res Int 2016; 2016: 3765608.

13 Lennon R, Singh A, Welsh GI, et al. Hemopexin induces

recurrence show likelihood of remission.86 The role of nephrin-dependent reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton in

lipid apheresis in achieving remission in patients with podocytes. J Am Soc Nephrol 2008; 19: 2140–49.

recurrent FSGS is under investigation. Guidelines for 14 Wei C, Trachtman H, Li J, et al. Circulating suPAR in two cohorts of

primary FSGS. J Am Soc Nephrol 2012; 23: 2051–59.

prevention and management of recurrent FSGS in

15 Sinha A, Bajpai J, Saini S, et al. Serum-soluble urokinase receptor

allograft recipients are summarised in panel 2. levels do not distinguish focal segmental glomerulosclerosis from

other causes of nephrotic syndrome in children. Kidney Int 2014;

Future directions in research 85: 649–58.

16 Nammalwar BR, Vijayakumar M, Prahlad N. Experience of renal

The biggest challenge, as we see it, is to define the biopsy in children with nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 2006;

presumed circulating factors that cause the disease in 21: 286–88.

most patients with SRNS. The nature of this factor has 17 Sinha A, Sharma A, Mehta A, et al. Calcineurin inhibitor induced

nephrotoxicity in steroid resistant nephrotic syndrome.

been investigated for several decades without success. Indian J Nephrol 2013; 23: 41–46.

The precise effect of this circulating factor on podocyte 18 Gipson DS, Trachtman H, Kaskel FJ, et al. Clinical trial of focal

biology also needs to be clarified. We suspect that the segmental glomerulosclerosis in children and young adults.

Kidney Int 2011; 80: 868–78.

circulating factor is in some way related to the immune 19 Trautmann A, Schnaidt S, Lipska-Zietkiewicz BS, et al.

system, since all currently effective treatments are with Long-term outcome of steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome in

immunosuppressive medications. children. J Am Soc Nephrol 2017; 28: 3055–65.

20 Shen X, Jiang H, Ying M, et al. Calcineurin inhibitors ciclosporin A

The number of genes causing SRNS will undoubtedly and tacrolimus protect against podocyte injury induced by puromycin

continue to rise until all have been found. Patients with aminonucleoside in rodent models. Sci Rep 2016; 6: 32087.

SRNS who have an underlying genetic disorder are 21 Hodson EM, Wong SC, Willis NS, Craig JC. Interventions for

idiopathic steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome in children.

unlikely to respond to medications and might be future Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; 10: CD003594.

candidates for genetic therapy, including genomic 22 Gulati A, Sinha A, Gupta A, et al. Treatment with tacrolimus and

editing. prednisolone is preferable to intravenous cyclophosphamide as the

initial therapy for children with steroid-resistant nephrotic

Contributors syndrome. Kidney Int 2012; 82: 1130–35.

All authors wrote the first draft of one part of the Review. The draft was 23 Hodson EM, Willis NS, Craig JC. Interventions for idiopathic

reviewed by all authors iteratively, until all three approved of the final steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome in children.

manuscript. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010; 10: CD003594.

Declaration of interests 24 Choudhry S, Bagga A, Hari P, Sharma S, Kalaivani M, Dinda A.

Efficacy and safety of tacrolimus versus ciclosporin in children with

We declare no competing interests.

steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome: a randomized controlled trial.

References Am J Kidney Dis 2009; 53: 760–69.

1 Lombel RM, Gipson DS, Hodson EM. Treatment of steroid-sensitive 25 Gulati A, Sinha A, Jordan SC, et al. Efficacy and safety of treatment

nephrotic syndrome: new guidelines from KDIGO. with rituximab for difficult steroid-resistant and -dependent

Pediatr Nephrol 2013; 28: 415–26. nephrotic syndrome: multicentric report. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010;

2 Lombel RM, Hodson EM, Gipson DS. Treatment of steroid-resistant 5: 2207–12.

nephrotic syndrome in children: new guidelines from KDIGO. 26 Sinha A, Gupta A, Kalaivani M, Hari P, Dinda AK, Bagga A.

Pediatr Nephrol 2013; 28: 409–14. Mycophenolate mofetil is inferior to tacrolimus in sustaining

3 Nourbakhsh N, Mak RH. Steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome: past remission in children with idiopathic steroid-resistant nephrotic

and current perspectives. Pediatric Health Med Ther 2017; 8: 29–37. syndrome. Kidney Int 2017; 92: 248–57.

4 Trautmann A, Bodria M, Ozaltin F, et al. Spectrum of steroid-resistant 27 Gulati A, Bagga A, Gulati S, Mehta KP, Vijayakumar M.

and congenital nephrotic syndrome in children: the PodoNet registry Management of steroid resistant nephrotic syndrome.

cohort. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2015; 10: 592–600. Indian Pediatr 2009; 46: 35–47.

www.thelancet.com/child-adolescent Published online October 17, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30283-9 9

Review

28 Filler G, Alvarez-Elias AC, McIntyre C, Medeiros M. 51 Sato M, Ito S, Ogura M, et al. Atypical Pneumocystis jiroveci

The compelling case for therapeutic drug monitoring of pneumonia with multiple nodular granulomas after rituximab for

mycophenolate mofetil therapy. Pediatr Nephrol 2017; 32: 21–29. refractory nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 2013; 28: 145–49.

29 Gellermann J, Weber L, Pape L, Tonshoff B, Hoyer P, Querfeld U. 52 Colucci M, Carsetti R, Cascioli S, et al. B cell reconstitution after

Mycophenolate mofetil versus ciclosporin A in children with rituximab treatment in idiopathic nephrotic syndrome.

frequently relapsing nephrotic syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol 2013; J Am Soc Nephrol 2016; 27: 1811–22.

24: 1689–97. 53 Colucci M, Carsetti R, Cascioli S, Serafinelli J, Emma F, Vivarelli M.

30 El-Reshaid K, El-Reshaid W, Madda J. Combination of B cell phenotype in pediatric idiopathic nephrotic syndrome.

immunosuppressive agents in treatment of steroid-resistant Pediatr Nephrol 2018; published online Sept 28. DOI:10.1007/s00467-

minimal change disease and primary focal segmental 018-4095-z (preprint).

glomerulosclerosis. Ren Fail 2005; 27: 523–30. 54 Belingheri M, Moroni G, Messa P. Available and incoming

31 Wu B, Mao J, Shen H, et al. Triple immunosuppressive therapy in therapies for idiopathic focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis in

steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome children with tacrolimus adults. J Nephrol 2018; 31: 37–45.

resistance or tacrolimus sensitivity but frequently relapsing. 55 Basu B. Ofatumumab for rituximab-resistant nephrotic syndrome.

Nephrology Carlton 2015; 20: 18–24. N Engl J Med 2014; 370: 1268–70.

32 [No authors listed]. Prospective, controlled trial of 56 Bonanni A, Rossi R, Murtas C, Ghiggeri GM. Low-dose ofatumumab

cyclophosphamide therapy in children with nephrotic syndrome. for rituximab-resistant nephrotic syndrome. BMJ Case Rep 2015;

Report of the International Study of Kidney Disease in Children. 2015: bcr2015210208.

Lancet 1974; 304: 423–27. 57 Wang CS, Liverman RS, Garro R, et al. Ofatumumab for the

33 Tarshish P, Tobin JN, Bernstein J, Edelmann CM. treatment of childhood nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 2017;

Cyclophosphamide does not benefit patients with focal segmental 32: 835–41.

glomerulosclerosis. A report of the International Study of Kidney 58 Yu CC, Fornoni A, Weins A, et al. Abatacept in B7–1-positive

Disease in Children. Pediatr Nephrol 1996; 10: 590–93. proteinuric kidney disease. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 2416–23.

34 Tune BM, Mendoza SA. Treatment of the idiopathic nephrotic 59 Delville M, Baye E, Durrbach A, et al. B7–1 blockade does not

syndrome: regimens and outcomes in children and adults. improve post-transplant nephrotic syndrome caused by recurrent

J Am Soc Nephrol 1997; 8: 824–32. FSGS. J Am Soc Nephrol 2016; 27: 2520–27.

35 Bajpai A, Bagga A, Hari P, Dinda A, Srivastava RN. Intravenous 60 Garin EH, Reiser J, Cara-Fuentes G, et al. Case series: CTLA4-IgG1

cyclophosphamide in steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. therapy in minimal change disease and focal segmental

Pediatr Nephrol 2003; 18: 351–56. glomerulosclerosis. Pediatr Nephrol 2015; 30: 469–77.

36 Latta K, Von SC, Ehrich JH. A meta-analysis of cytotoxic treatment 61 Mateer FM, Weigand FA, Greenman L, Weber CJ Jr, Kunkel GA,

for frequently relapsing nephrotic syndrome in children. Danowski TS. Clinical results and effects of protenuria in one

Pediatr Nephrol 2001; 16: 271–82. hundred and six instances. AMA J Dis Child 1957; 93: 591–603.

37 Bagga A, Sinha A, Moudgil A. Rituximab in patients with the 62 Lieberman KV, Pavlova-Wolf A. Adrenocorticotropic hormone

steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. N Engl J Med 2007; 356: 2751–52. therapy for the treatment of idiopathic nephrotic syndrome in

38 Benz K, Dotsch J, Rascher W, Stachel D. Change of the course of children and young adults: a systematic review of early clinical

steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome after rituximab therapy. studies with contemporary relevance. J Nephrol 2017; 30: 35–44.

Pediatr Nephrol 2004; 19: 794–97. 63 Hogan J, Bomback AS, Metha K, et al. Treatment of idiopathic

39 Ito S, Kamei K, Ogura M, et al. Survey of rituximab treatment for FSGS with adrenocorticotropic hormone gel.

childhood-onset refractory nephrotic syndrome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2013; 8: 2072–81.

Pediatr Nephrol 2013; 28: 257–64. 64 Gong R. Leveraging melanocortin pathways to treat glomerular

40 Nakagawa T, Shiratori A, Kawaba Y, Kanda K, Tanaka R. Efficacy of diseases. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2014; 21: 134–51.

rituximab therapy against intractable steroid-resistant nephrotic 65 Trachtman H, Vento S, Herreshoff E, et al. Efficacy of galactose and

syndrome. Pediatr Int 2016; 58: 1003–08. adalimumab in patients with resistant focal segmental

41 Prytula A, Iijima K, Kamei K, et al. Rituximab in refractory glomerulosclerosis: report of the font clinical trial group.

nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 2010; 25: 461–68. BMC Nephrol 2015; 16: 111.

42 Sinha A, Bhatia D, Gulati A, et al. Efficacy and safety of rituximab in 66 Peyser A, Machardy N, Tarapore F, et al. Follow-up of phase I trial

children with difficult-to-treat nephrotic syndrome. of adalimumab and rosiglitazone in FSGS: III. Report on the FONT

Nephrol Dial Transplant 2015; 30: 96–106. study. BMC Nephrol 2010; 11: 2.

43 Magnasco A, Ravani P, Edefonti A, et al. Rituximab in children with 67 Hattori M, Chikamoto H, Akioka Y, et al. A combined low-density

resistant idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol 2012; lipoprotein apheresis and prednisone therapy for steroid-resistant

23: 1117–24. primary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in children.

44 Leandro MJ, Edwards JC, Cambridge G, Ehrenstein MR, Am J Kidney Dis 2003; 42: 1121–30.

Isenberg DA. An open study of B lymphocyte depletion in systemic 68 McCaffrey J, Lennon R, Webb NJ. The non-immunosuppressive

lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2002; 46: 2673–77. management of childhood nephrotic syndrome.

45 Kamei K, Ogura M, Sato M, Ito S, Ishikura K. Infusion reactions Pediatr Nephrol 2016; 31: 1383–402.

associated with rituximab treatment for childhood-onset 69 Kapur G, Valentini RP, Imam AA, Mattoo TK. Treatment of severe

complicated nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 2018; 33: 1013–18. edema in children with nephrotic syndrome with diuretics alone—

46 Kamei K, Takahashi M, Fuyama M, et al. Rituximab-associated a prospective study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2009; 4: 907–13.

agranulocytosis in children with refractory idiopathic nephrotic 70 Bockenhauer D. Over- or underfill: not all nephrotic states are

syndrome: case series and review of literature. created equal. Pediatr Nephrol 2013; 28: 1153–56.

Nephrol Dial Transplant 2015; 30: 91–96. 71 Rheault MN, Zhang L, Selewski DT, et al. AKI in children

47 Sellier-Leclerc AL, Belli E, Guerin V, Dorfmuller P, Deschenes G. hospitalized with nephrotic syndrome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2015;

Fulminant viral myocarditis after rituximab therapy in pediatric 10: 2110–18.

nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 2013; 28: 1875–79. 72 Bagga A, Mudigoudar BD, Hari P, Vasudev V. Enalapril dosage in

48 Delbue S, Ferraresso M, Elia F, et al. Investigation of steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 2004;

polyomaviruses replication in pediatric patients with nephropathy 19: 45–50.

receiving rituximab. J Med Virol 2012; 84: 1464–70. 73 Yi Z, Li Z, Wu XC, He QN, Dang XQ, He XJ. Effect of fosinopril in

49 Kronbichler A, Windpessl M, Pieringer H, Jayne DRW. children with steroid-resistant idiopathic nephrotic syndrome.

Rituximab for immunologic renal disease: what the nephrologist Pediatr Nephrol 2006; 21: 967–72.

needs to know. Autoimmun Rev 2017; 16: 633–43. 74 Makani H, Bangalore S, Desouza KA, Shah A, Messerli FH.

50 Bitzan M, Anselmo M, Carpineta L. Rituximab B-cell depleting Efficacy and safety of dual blockade of the renin-angiotensin

antibody associated lung injury (RALI): a pediatric case and system: meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ 2013; 346: f360.

systematic review of the literature. Pediatr Pulmonol 2009;

44: 922–34.

10 www.thelancet.com/child-adolescent Published online October 17, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30283-9

Review

75 Komers R, Gipson DS, Nelson P, et al. Efficacy and safety of 84 Delville M, Sigdel TK, Wei C, et al. A circulating antibody panel for

sparsentan compared with irbesartan in patients with primary focal pretransplant prediction of FSGS recurrence after kidney

segmental glomerulosclerosis: randomized, controlled trial design transplantation. Sci Transl Med 2014; 6: 256ra136.

(DUET). Kidney Int Rep 2017; 2: 654–64. 85 Puisset F, White-Koning M, Kamar N, et al. Population

76 Arneil GC. The nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Clin North Am 1971; pharmacokinetics of rituximab with or without plasmapheresis in

18: 547–59. kidney patients with antibody-mediated disease.

77 Querfeld U, Kohl B, Fiehn W, et al. Probucol for treatment of Br J Clin Pharmacol 2013; 76: 734–40.

hyperlipidemia in persistent childhood nephrotic syndrome. 86 Kashgary A, Sontrop JM, Li L, et al. The role of plasma exchange in

Report of a prospective uncontrolled multicenter study. treating post-transplant focal segmental glomerulosclerosis:

Pediatr Nephrol 1999; 13: 7–12. asystematic review and meta-analysis of 77 case-reports and

78 Banerjee S, Basu S, Sengupta J. Vitamin D in nephrotic syndrome case-series. BMC Nephrol 2016; 17: 104.

remission: a case-control study. Pediatr Nephrol 2013; 28: 1983–89. 87 Ponticelli C. Recurrence of focal segmental glomerular sclerosis

79 Inaba A, Hamasaki Y, Ishikura K, et al. Long-term outcome of (FSGS) after renal transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2010;

idiopathic steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome in children. 25: 25–31.

Pediatr Nephrol 2016; 31: 425–34. 88 Araya CE, Dharnidharka VR. The factors that may predict response

80 Leca N. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis recurrence in the renal to rituximab therapy in recurrent focal segmental glomerulosclerosis:

allograft. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2014; 21: 448–52. a systematic review. J Transplant 2011; 2011: 374213.

81 Saeed B, Mazloum H, Askar M. Spontaneous remission of 89 Sakai K, Takasu J, Nihei H, et al. Protocol biopsies for focal

post-transplant recurrent focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis. segmental glomerulosclerosis treated with plasma exchange and

Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 2011; 22: 1219–22. rituximab in a renal transplant patient. Clin Transplant 2010;

82 Vinai M, Waber P, Seikaly MG. Recurrence of focal segmental 24 (suppl 22): 60–65.

glomerulosclerosis in renal allograft: an in-depth review.

© 2018 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Pediatr Transplant 2010; 14: 314–25.

83 Ding WY, Koziell A, McCarthy HJ, et al. Initial steroid sensitivity in

children with steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome predicts

post-transplant recurrence. J Am Soc Nephrol 2014; 25: 1342–48.

www.thelancet.com/child-adolescent Published online October 17, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30283-9 11

You might also like

- Harrison - Gastroenterology and Hepatology - 2013 Ed 18 PDFDocument784 pagesHarrison - Gastroenterology and Hepatology - 2013 Ed 18 PDFCarmen Elena Plaisanu94% (34)

- Understanding Chronic Kidney Disease: A guide for the non-specialistFrom EverandUnderstanding Chronic Kidney Disease: A guide for the non-specialistRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Measles PamphletDocument2 pagesMeasles Pamphletapi-384459604No ratings yet

- 10-26 Soap NoteDocument2 pages10-26 Soap Notedondavis77No ratings yet

- Nephrotic Syndrome: Rasheed Gbadegesin and William E. SmoyerDocument14 pagesNephrotic Syndrome: Rasheed Gbadegesin and William E. SmoyerrrentiknsNo ratings yet

- Neph Rot I C Syndrome IntroDocument14 pagesNeph Rot I C Syndrome IntroThaer AbusbaitanNo ratings yet

- Intravenous Cyclophosphamide in Steroid-Resistant Nephrotic SyndromeDocument6 pagesIntravenous Cyclophosphamide in Steroid-Resistant Nephrotic SyndromeRicho WijayaNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Steroid Sensitive Nephrotic Syndrome: A.S. AbeyagunawardenaDocument8 pagesTreatment of Steroid Sensitive Nephrotic Syndrome: A.S. AbeyagunawardenaZenithaMeidaNo ratings yet

- Overview of Nephrotic SyndromeDocument19 pagesOverview of Nephrotic Syndromefarmasi_hm100% (1)

- Treatment-Associated Side Effects in Patients With Steroid-Dependent Nephrotic SyndromeDocument6 pagesTreatment-Associated Side Effects in Patients With Steroid-Dependent Nephrotic SyndromeIndah SolehaNo ratings yet

- IJP Volume 4 Issue 1 Pages 1233-1242Document10 pagesIJP Volume 4 Issue 1 Pages 1233-1242Anca AdamNo ratings yet

- Oftal Case StudyDocument11 pagesOftal Case StudyMohamad RaisNo ratings yet

- Acid-Base and Electrolyte Teaching Case Diuretic Resistance: Ewout J. Hoorn, MD, PHD, and David H. Ellison, MDDocument7 pagesAcid-Base and Electrolyte Teaching Case Diuretic Resistance: Ewout J. Hoorn, MD, PHD, and David H. Ellison, MDDiana GarcíaNo ratings yet

- 16.nephrotic SyndromeDocument115 pages16.nephrotic SyndromeRhomizal MazaliNo ratings yet

- Nelson: Nephrotic Syndrome (NS) TreatmentDocument7 pagesNelson: Nephrotic Syndrome (NS) TreatmentadystiNo ratings yet

- Review of Refractory Lupus NephritisDocument12 pagesReview of Refractory Lupus NephritisDeddy WijayaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal ANCADocument22 pagesJurnal ANCAMuthia FaurinNo ratings yet

- Bmjopen 2017 018148 PDFDocument7 pagesBmjopen 2017 018148 PDFEva AstriaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0140673623010516 MainDocument16 pages1 s2.0 S0140673623010516 MainJOY INDRA GRACENo ratings yet

- Nephrotic Syndrome: Ron Christian Neil T. Rodriguez, MD 1 Year Pedia ResidentDocument26 pagesNephrotic Syndrome: Ron Christian Neil T. Rodriguez, MD 1 Year Pedia ResidentRon Christian Neil RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Cyclosporine Experience in Nephrotic Syndrome: K. Phadke, S. Ballal and V. MaiyaDocument6 pagesCyclosporine Experience in Nephrotic Syndrome: K. Phadke, S. Ballal and V. Maiyarachel0301No ratings yet

- Nephrotic Syndrome Treatment & Management - Approach Considerations, Acute NephroDocument5 pagesNephrotic Syndrome Treatment & Management - Approach Considerations, Acute NephroErvirson Jair Cañon AbrilNo ratings yet

- CKD Lancet 2021Document17 pagesCKD Lancet 2021Fabiola AlonsoNo ratings yet

- Gulati 2020Document14 pagesGulati 2020Anisha MDNo ratings yet

- Nephrotic SyndromeDocument9 pagesNephrotic SyndromeSonny WijanarkoNo ratings yet

- Final NS Guidelines August 26 2019-1Document17 pagesFinal NS Guidelines August 26 2019-1Nido MalghaniNo ratings yet

- Kidney News Article p20 7Document2 pagesKidney News Article p20 7ilgarciaNo ratings yet

- E423 FullDocument11 pagesE423 FullCecepNo ratings yet

- 101-Article For Submission-298-1-10-20210207Document21 pages101-Article For Submission-298-1-10-20210207Umer RazaqNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Genetic Testing in Adolescent-Onset Steroid-Resistant Nephrotic Syndrome - Case ReportDocument9 pagesThe Importance of Genetic Testing in Adolescent-Onset Steroid-Resistant Nephrotic Syndrome - Case ReportAlrista MawarNo ratings yet

- 08 Primary Glumerulopathies I - OtDocument2 pages08 Primary Glumerulopathies I - OtGerarld Immanuel KairupanNo ratings yet

- FSR Physicians Protocol1Document32 pagesFSR Physicians Protocol1Nishtha SinghalNo ratings yet

- Adult Minimal-Change Disease: Clinical Characteristics, Treatment, and OutcomesDocument9 pagesAdult Minimal-Change Disease: Clinical Characteristics, Treatment, and OutcomesMutiara RizkyNo ratings yet

- Can Radioiodine Be Administered Effectively and Safely To A Patient With Severe Chronic Kidney Disease?Document6 pagesCan Radioiodine Be Administered Effectively and Safely To A Patient With Severe Chronic Kidney Disease?Mariano CadeNo ratings yet

- Nephrotic Syndrome Guidelines 2019Document14 pagesNephrotic Syndrome Guidelines 2019Sara Ilyas KhanNo ratings yet

- Crescentic Glomerulonephritis and Membranous NephropathyDocument8 pagesCrescentic Glomerulonephritis and Membranous NephropathyVíctor Cruz CeliNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Anita HuraeraDocument3 pagesJurnal Anita HuraeraRachmi AvillianiNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1755001708000109 MainDocument5 pages1 s2.0 S1755001708000109 MainRazmi Wulan DiastutiNo ratings yet

- Ten Common Mistakes in The Management of Lupus Nephritis. 2014Document10 pagesTen Common Mistakes in The Management of Lupus Nephritis. 2014Alejandro Rivera IbarraNo ratings yet

- Approach ConsiderationsDocument12 pagesApproach ConsiderationsTyna Mew-mewNo ratings yet

- Review: Hepatocellular Damage From Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory DrugsDocument5 pagesReview: Hepatocellular Damage From Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugsshessy-jolycia-kerrora-3047No ratings yet

- Greenbaum 2012Document14 pagesGreenbaum 2012Aulia putriNo ratings yet

- Medip, IJCP-2856 ODocument6 pagesMedip, IJCP-2856 OMarcelita DuwiriNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Steroid Dependence Nephrotic Syndrome: A Case SeriesDocument2 pagesPediatric Steroid Dependence Nephrotic Syndrome: A Case SeriesadeNo ratings yet

- Efficacy of Higher-Dose Levamisole in Maintaining Remission in Steroid-Dependant Nephrotic SyndromeDocument6 pagesEfficacy of Higher-Dose Levamisole in Maintaining Remission in Steroid-Dependant Nephrotic Syndromechandra maslikhaNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Journal 3Document9 pagesDiagnostic Journal 3dr.yogaNo ratings yet

- Chap128 Terapi GNA PDFDocument4 pagesChap128 Terapi GNA PDFnovaNo ratings yet

- Nephrotic Syndrome 5th Year Lecture 2011Document7 pagesNephrotic Syndrome 5th Year Lecture 2011Gutierrez MarinellNo ratings yet

- Early Subsequent Relapse As A Predictor of Unfavourable Prognosis of Idiopathic Nephrotic SyndromeDocument6 pagesEarly Subsequent Relapse As A Predictor of Unfavourable Prognosis of Idiopathic Nephrotic SyndromeBianti Nur'ainiNo ratings yet

- ES-Eisenmenger Syndrome - Not Always Inoperable. HuangDocument8 pagesES-Eisenmenger Syndrome - Not Always Inoperable. HuangRamaNo ratings yet

- Duchenne ENDocument7 pagesDuchenne ENAli Toma HmedatNo ratings yet

- Management of The Complications of Nephrotic SyndromeDocument6 pagesManagement of The Complications of Nephrotic SyndromeRagabi RezaNo ratings yet

- AMACING2017Document11 pagesAMACING2017Emiliano GarcilazoNo ratings yet

- Consensus and Audit Potential For Steroid Responsive Nephrotic SyndromeDocument7 pagesConsensus and Audit Potential For Steroid Responsive Nephrotic Syndromedanielleon65No ratings yet

- Adrenal Senior 1Document12 pagesAdrenal Senior 1mohammad saifuddinNo ratings yet

- Nephrotic Syndrome PDFDocument36 pagesNephrotic Syndrome PDFanwar jabariNo ratings yet

- RHEUMATOLOGY1 - RA Refractory To DMARDsDocument4 pagesRHEUMATOLOGY1 - RA Refractory To DMARDsEunice PalloganNo ratings yet

- Case Report of Acute and Chronic Interstitial NephritisDocument10 pagesCase Report of Acute and Chronic Interstitial NephritisDoncyNo ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDocument12 pagesNIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptIgo MouraNo ratings yet

- Insuficiencia Renal CronicaDocument13 pagesInsuficiencia Renal CronicaCarlos DNo ratings yet

- Methyl PrednisoloneDocument4 pagesMethyl PrednisoloneAnjar WijayadiNo ratings yet

- Case Presentation and Review of LiteratureDocument65 pagesCase Presentation and Review of LiteratureShrey BhatlaNo ratings yet

- Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) : Diabetes High Blood Pressure Responsible For Up To Two-Thirds GlomerulonephritisDocument6 pagesChronic Kidney Disease (CKD) : Diabetes High Blood Pressure Responsible For Up To Two-Thirds GlomerulonephritisKyle Ü D. CunanersNo ratings yet

- Norland Swissray Dmo2Document8 pagesNorland Swissray Dmo2Edison JmrNo ratings yet

- Medical Terminology 2 Cardiovascular System Lesson 2Document8 pagesMedical Terminology 2 Cardiovascular System Lesson 2sotman58No ratings yet

- The Anxiety Symptoms Among Chronic Kidney Disease Patients Who Undergo Hemodialysis TherapyDocument5 pagesThe Anxiety Symptoms Among Chronic Kidney Disease Patients Who Undergo Hemodialysis TherapyIJPHSNo ratings yet

- Surgical Management of Fourniers Gangrene A Seven Year Experience at The Philippine General HospitalDocument6 pagesSurgical Management of Fourniers Gangrene A Seven Year Experience at The Philippine General HospitalGian PagadduNo ratings yet

- Role of Radiographs in Pdl. DiseaseDocument71 pagesRole of Radiographs in Pdl. DiseaseDrKrishna Das0% (1)

- Human Defenses Against Infectious Diseases: Barcarse, Renzel DaveDocument23 pagesHuman Defenses Against Infectious Diseases: Barcarse, Renzel Davehmoody tNo ratings yet

- Co-Tle 8Document19 pagesCo-Tle 8janine100% (1)

- TB in ChildrenDocument26 pagesTB in ChildrenReagan PatriarcaNo ratings yet

- Gowland - The Problem of Early Modern MelancholyDocument45 pagesGowland - The Problem of Early Modern MelancholyHolly Blastoise SharpNo ratings yet

- WaterleafDocument2 pagesWaterleafGILBERTNo ratings yet

- Asa ClassDocument3 pagesAsa ClassPriska Gusti Wulandari67% (3)

- Tuned Spacer BlendDocument7 pagesTuned Spacer Blendadvantage025No ratings yet

- Problem TreeDocument1 pageProblem Treeyel5buscatoNo ratings yet

- Pathology Mcqs Week 11: 1. in Adult Respiratory Distress SyndromeDocument4 pagesPathology Mcqs Week 11: 1. in Adult Respiratory Distress Syndromeمجتبى علي100% (5)

- Uterine MyomDocument19 pagesUterine MyomfahlevyNo ratings yet

- Product Brochure - Lunit INSIGHT CXRDocument16 pagesProduct Brochure - Lunit INSIGHT CXRDebora NunesNo ratings yet

- Drug Study For Multiple Sclerosis (Betaseron)Document4 pagesDrug Study For Multiple Sclerosis (Betaseron)Leslie Lagat PaguioNo ratings yet

- ARDS QuizDocument6 pagesARDS QuizMeliza BancolitaNo ratings yet

- Hypertension Management-1Document15 pagesHypertension Management-1Ali Sibra MulluziNo ratings yet

- Set 1 Checked: E. Pathological ConditionDocument60 pagesSet 1 Checked: E. Pathological ConditionKunal BhamareNo ratings yet

- Or Drug StudyDocument19 pagesOr Drug StudyBenjie DimayacyacNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Vitae Panagiotis Vagianas 10.07.2012Document7 pagesCurriculum Vitae Panagiotis Vagianas 10.07.2012Panagiotis VagianasNo ratings yet

- A Case Study-FinalDocument45 pagesA Case Study-FinalJáylord OsorioNo ratings yet

- Understanding Eating DisordersDocument10 pagesUnderstanding Eating DisorderspuchioNo ratings yet

- TMC213. Bacalso, Eva Mae. Module 2, Lesson3-5Document8 pagesTMC213. Bacalso, Eva Mae. Module 2, Lesson3-5John Ariel Labnao GelbolingoNo ratings yet

- Motility Disorders of The GITDocument57 pagesMotility Disorders of The GITMahmoud AjinehNo ratings yet