Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Schizophrenia Trends in Diagnosis and Therapy

Uploaded by

Doc HadiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Schizophrenia Trends in Diagnosis and Therapy

Uploaded by

Doc HadiCopyright:

Available Formats

doi:10.1111/pcn.

12322

Schizophrenia in 2020: Trends in diagnosis and therapy

1,2 1,2

Wolfgang Gaebel, MD * and Jürgen Zielasek, MD

1

Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Medical Faculty, Heinrich Heine University, and 2WHO Collaborating

Center for Quality Assurance and Empowerment in Mental Health, Düsseldorf, Germany

Schizophrenia research is providing an increasing stimulation, an additional hope is to improve early

number of studies and important insights into the detection and prevention. As the results of new

condition’s etiopathogenesis based on genetic, neu- research into the etiopathogenesis of schizophrenia

ropsychological and cranial neuroimaging studies. are promising to improve diagnosis, classification

However, research progress has not yet led to the and therapy in the future, a picture of complex

incorporation of such findings into the revised clas- brain dysfunction is currently emerging requiring

sification criteria of mental disorders or everyday sophisticated mathematical methods of analysis. The

clinical practice. By 2020, schizophrenia will most imminent clinical challenge will be to develop com-

likely still be a clinically defined primary psychotic prehensive diagnostic and treatment modules

disorder. While there is some hope that treatment individually tailored to the time-variable needs of

will be improved with new antipsychotic drugs, drugs patients and their families.

addressing negative symptoms, more refined psy-

chotherapy approaches and the introduction of Key words: etiopathogenesis, classification, psycho-

new treatment modalities like transcranial magnetic ses, psychotic disorders, schizophrenia.

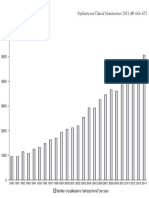

LINICAL AND BASIC research has been provid- This indicates that schizophrenia research is

C ing increasingly detailed information about the

etiopathogenesis, diagnosis, classification and treat-

picking up pace. New genome-wide association

studies and sophisticated methods to analyze func-

ment of schizophrenia. The number of published tional neuroimaging data are being used. New detec-

studies in schizophrenia research has been rapidly tion methods, like magnetic resonance spectroscopy,

increasing over the last 25 years and an analysis of are being introduced in schizophrenia research. The

MEDLINE, a relevant database of international scien- main challenges to clinical psychiatrists and research-

tific publications, shows that the increase of ers in the field of primary psychotic disorders are not

schizophrenia-related publications since 1990 is only to keep abreast of the rising stack of schizophre-

much larger than the increase of the total number of nia research publications on their desks, but also to

all research publications included in MEDLINE (Fig. 1). evaluate this vast amount of knowledge as regards its

pertinence to everyday clinical diagnostic and thera-

peutic practice. This review aims to: (i) describe the

major findings of schizophrenia research over the last

*Correspondence: Wolfgang Gaebel, MD, Department of Psychiatry 5–10 years, which may be of importance for shaping

and Psychotherapy, LVR-Klinikum Düsseldorf, Bergische Landstr. 2,

D-40629 Düsseldorf, Germany. Email:

the next 5 years of schizophrenia research and clinical

wolfgang.gaebel@uni-duesseldorf.de practice; and (ii) describe the scientific challenges to

Accepted 22 May 2015. the fields of schizophrenia research and clinical prac-

© 2015 The Authors 661

Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences © 2015 Japanese Society of Psychiatry and Neurology

662 W. Gaebel and J. Zielasek Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 2015; 69: 661–673

6000

5000

4000

3000

2000

1000

0

1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

Number of publications “schizophrenia” per year

Figure 1. Number of publications indexed in MEDLINE per year with the term ‘schizophrenia’ in the title and/or the abstract. The

number of annual publications related to ‘schizophrenia’ has quadrupled in the last 25 years from 958 in 1990 to 5054 in 2014.

The total number of all publications indexed in MEDLINE only rose from 408 502 in 1990 to 1 084 367 in 2014, which means that

the total number of all publications increased by a factor of approximately 2.5. Thus, the increase of the annual number of

publications about schizophrenia rose disproportionately faster than the general number of publications in MEDLINE. Date of

analysis: 26 February 2015.

tice for the next 5 years, and how these challenges schizophrenia) of the World Health Organization

may be addressed. (WHO) International Classification of Disorders

(ICD). ICD-11 is due to be published in 2017 and at

the time of writing, a preliminary beta version of

TRENDS IN SCHIZOPHRENIA ICD-11 was available for review on the Internet

CLASSIFICATION AND DIAGNOSIS 2020 (http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd11/browse/f/

en, last accessed 26 February 2015). The develop-

ICD-11 and DSM-5: Revision of the ment of both ICD-11 and DSM-5 were and are

classification criteria for schizophrenia characterized by disorder group-specific working

This field has mainly been influenced by the work to groups of clinical and research experts, who reviewed

prepare a revised version of the Diagnostic and Statis- the available evidence for classification issues

tical Manual for Mental Disorders, which was pub- of schizophrenia, and prepared suggestions for

lished by the American Psychiatric Association in changes.2–4 Several common and divergent

2013.1 In addition, there is a currently ongoing revi- approaches to the classification of schizophrenia in

sion process of the 10th version of the clinical DSM-5 and ICD-11 are evident. Both classification

diagnostic criteria for mental disorders (including systems omit the traditional clinical subtypes of

© 2015 The Authors

Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences © 2015 Japanese Society of Psychiatry and Neurology

Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 2015; 69: 661–673 Schizophrenia in 2020 663

DSM-5

A. Two (or more) of the following, each present for a significant portion of time during a 1-month period (or less if successfully

treated).

At least one of these must be (1), (2), or (3):

1. Delusions.

2. Hallucinations.

3. Disorganized speech (e.g., frequent derailment or incoherence).

4. Grossly disorganized or catatonic behavior.

5. Negative symptoms (i.e., diminished emotional expression or avolition).

B. Social/occupational dysfunction

C. Duration (6 months)

D. Schizoaffective and Mood Disorder Exclusion

E. Substance/General Medical Condition Exclusion

F. Relationship to a Pervasive Developmental Disorder

ICD-11

At least two of the following (one of which must be from the list of [a] to [d]) must be present (by patient report or observation by the

clinician or other informants) most of the time for a period of 1 month or more:

a. Persistent delusions (e.g., grandiose delusions, delusions of reference, persecutory delusions).

b. Persistent hallucinations (most commonly auditory, although they may be in any sensory modality).

c. Disorganized thinking (formal thought disorder) (e.g., tangentiality and loose associations,irrelevant speech, neologisms). When

severe, the person’s speech may be so incoherent as to be incomprehensible (‘word salad’).

d. Experiences of influence, passivity or control (e.g., the experience that thoughts are not generated by the person, are beingplaced

in one’s mind or withdrawn from one’s mind by others, or that thoughts are being broadcast to others).

e. Negative symptoms, such as affective flattening, alogia or paucity of speech, avolition, asociality and anhedonia.

f. Grossly disorganized behavior, which may be noted in any form of goal-directed activity (e.g., unpredictable or inappropriate

emotional responses, behavior that appears bizarre or purposeless).

g. Psychomotor disturbances, such as catatonic restlessness or agitation, posturing, waxy flexibility, negativism, mutism, or stupor.

Figure 2. Clinical diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia in DSM-51 and ICD-11 (preliminary beta version, to be finalized by 2017;

http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd11/browse/f/en, last accessed 26 February 2015).

schizophrenia (paranoid, hebephrenic), because a the two classification systems, which includes func-

number of studies indicated that such clinical tional impairments in DSM-5, whereas WHO dis-

subtyping had little relevance for determining prog- courages the use of functional impairments as criteria

nosis or therapy. Similarly, first-rank symptoms were for a mental disorder.

de-emphasized in both classification systems follow- Both classification systems took steps in the direc-

ing studies, indicating that these had little prognostic tion of a ‘dimensional’ clinical assessment of schizo-

relevance.5 The classification in both systems will rely phrenia symptoms using severity ratings for positive

on the assessment of the clinical symptoms of schizo- symptoms, negative symptoms, mood symptoms,

phrenia, a minimum disease duration (different in psychomotor symptoms and cognitive impairments,

both systems: 6 months in DSM-5 and 1 month sug- with some differences in the details of the two

gested for ICD-11, Fig. 2), and the exclusion of other systems (Fig. 2). Of note, in both systems, affective

somatic disorders or the effects of drugs or their with- symptoms, catatonia and cognitive impairment now

drawal as reasons for the appearance of psychotic form parts of the assessment of schizophrenia, with

symptoms. catatonia not a clinical subtype of schizophrenia, but

Importantly, DSM-5 requires the occurrence of one of the clinical manifestations without the status

functional impairments as a mandatory diagnostic of a separate clinical subtype. Recent research sug-

criterion, whereas ICD-11 will not include this as a gests that the classification criteria of DSM-5 for cata-

mandatory criterion. This difference reflects differ- tonia may not be sufficient and may lead to

ences of the general definition of a mental disorder in underdiagnosis,6 which is one of the reasons that in

© 2015 The Authors

Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences © 2015 Japanese Society of Psychiatry and Neurology

664 W. Gaebel and J. Zielasek Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 2015; 69: 661–673

Symptom Specifiers ICD-11 DSM-5

0 Positive symptoms • Hallucinations

1 Negative symptoms • Delusions

2 Depressive symptoms • Disorganized speech

3 Manic symptoms • Abnormal psychomotor

4 Psychomotor symptoms behavior

5 Cognitive impairment • Negative symptoms

• Impaired cognition

• Depression

• Mania

Course Specifiers 0 First episode, currently in acute episode

(harmonized for use in both 1 First episode, currently in partial remission

ICD-11 and DSM-5) 2 First episode, currently in full remission

3 Multiple episodes, currentlly in acute episode Figure 3. Symptom and source

4 Multiple episodes, currentlly in partial remission specifiers of ICD-11 (beta version,

5 Multiple episodes, currentlly in full remission

http://apps.who.int/classifications/

6 Continuous

icd11/browse/f/en, last accessed 26

7 Unspecified

February, 2015) and DSM-5.1

ICD-11, more comprehensive clinical feature lists of led to major paradigmatic changes, but rather to

catatonia are currently being developed. An impor- subtle moves in the direction of dimensional assess-

tant area of harmonization between ICD-11 and ments in the classification process and a clarification

DSM-5 regarding the schizophrenia criteria are the of course and symptom specifiers.

novel course criteria, which were developed in close

collaboration of the development teams of both

systems, and which are now formulated in a way to

cover all disease stages (Fig. 3).

Elucidation of the etiopathogenesis of

An attenuated psychosis syndrome was not consid-

schizophrenia

ered as a new diagnostic entity in DSM-5 given the Although the etiopathogenesis of schizophrenia is

lack of certainty about the progression rate of those still unknown, evidence from many lines of research

who experience such symptoms.7 The syndrome was (genetic, psychophysiology, neurobiology etc.)

included as a condition for further study in the indicates that there are probably many roads of

appendix of DSM-5. ICD-11 will probably reach a etiopathogenesis leading to the diverse clinical mani-

similar conclusion. However, the classification crite- festations of schizophrenia. Genetic research impli-

ria may need to be re-revised, as a Swiss study recently cates a large number of genetic variants in

showed that the current DSM-5 symptom list may schizophrenia, ranging from major copy number

exclude persons who have a stable prodromal variations to single gene polymorphisms. The multi-

syndrome, but no current progression, and who are tude of described genetic alterations (most of which

help-seeking.8 have a low penetrance) in patients with schizophre-

Notable is the absence of any etiopathogenetic nia is large and several challenges have arisen:9–13

aspects in the schizophrenia classification criteria of

DSM-5 and the current suggestions for ICD-11. Obvi- • The number of risk-associated loci in schizophrenia

ously, the currently available evidence was not con- is estimated to be at about 850 loci. All of these

sidered robust enough by the expert panels to warrant genetic risk markers may explain around 10% of all

the inclusion for example of genetic or other schizophrenia cases.

biomarker information in the classification process • Some rare copy number variations, especially those

(with the exception of the ruling out of somatic dis- involving partial deletions of the long arm of chro-

orders, for example by using cranial neuroimaging mosome 22 (22q11.2), show a high penetrance in

techniques to exclude a brain tumor as the reason for schizophrenia, but these cases only amount to

the occurrence of psychotic symptoms in an indi- approximately 0.2–0.3% of all patients with

vidual). Altogether, neither of the revision processes schizophrenia.

© 2015 The Authors

Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences © 2015 Japanese Society of Psychiatry and Neurology

Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 2015; 69: 661–673 Schizophrenia in 2020 665

• Genome-wide association studies in schizophrenia tions of the topological network structures, which

have added new risk loci and recently increased the involve the normally observed modular structure of

number of probably relevant genetic polymor- connectivity of brain regions via hubs as central

phisms into the range of n = 8500, but also increas- nodes of communication channeling between

ing the explained variance of liability to about modules.19,20 Such analyses may open new roads to

32%. therapeutic interventions by correcting altered con-

• None of the genetic polymorphisms demonstrated nectivity or modular brain topology using tech-

in schizophrenia is disease-specific or can be used niques developed in neurology for the treatment of

for individual diagnostic purposes or the classifi- Parkinson’s disease motor symptoms.19 However,

cation of schizophrenia. two aspects of caution need to be considered: (i) in

schizophrenia, it is still unclear if disturbed connec-

Recent genome-wide association studies converge tivity and disturbed modular topology are the

on genes involved in the regulation of synaptic causes or the consequences of the pathophysiology

activities, neurodevelopment and immune func- of schizophrenia; and (ii) altered brain network

tions.11 An interesting new aspect here is the finding topologies may represent attempts by the brain to

of immunity-related genes, which seems to compensate for schizophrenia-induced brain dys-

vindicate theories about an involvement of functions.21 Therefore, further studies are needed

neuroimmunologic processes in the pathogenesis of to prove that such dysfunctions are causes of

schizophrenia.14,15 Also, there is now a subtype of symptoms, and not (beneficial) compensatory

patients with symptoms of schizophrenia, who have mechanisms.

autoantibodies against the N-methyl-D-aspartate Besides such (neuro)biologic factors, psychosocial

receptor, and whose psychotic symptoms respond to factors are obviously also involved. Among the psy-

immunologic therapies.16 Clearly, more work is chological disease mechanisms, studies implicate

needed to characterize the clinical features of this factors like aberrant salience,22 jumping to conclu-

subgroup of patients, in whom autoantibody testing sions23 and biases in evidence integration24 in the

is needed to indicate immunologic therapy. formation of psychotic symptoms, and therapeuti-

However, it is still largely unknown how much and cally addressing such psychological dysfunctions for

by which pathomechanisms such genetic or immu- example with psychotherapeutic methods may lead

nologic variation contributes to the pathophysi- to novel therapies in the future, but will probably

ologic process of schizophrenia, except in the few not influence the diagnostic process in the next 5

cases of antineuronal-antibody-associated psychosis, years. Another aspect may emerge through research

in which the binding of the autoantibody to its on socioenvironmental pathogenic processes, which

brain receptors seems to be implicated (although may be detectable with techniques of epigenetic

this would still need to be elucidated in detail). One changes like altered DNA-methylation25 or through

of the common final pathways of the etiopathogen- effects on the brain of socioenvironmental

esis of schizophrenia is a disturbance of brain dopa- factors.26,27 However, these approaches are still far

mine neurotransmitter pathways, and investigations from clinical relevance. For clinical routine use, sen-

to subtype schizophrenia by responsiveness to anti- sitivity, specificity, and the positive and negative

dopaminergic (antipsychotic) treatment are under- predictive values would need to be available, and

way, which may lead to novel classification criteria such information is still lacking. Thus, while prog-

in the future.17 New technologies, like magnetic ress in the field of the etiopathogenesis of schizo-

resonance spectroscopy, are adding information on phrenia has been considerable, it has supported

dopamine and other neurotransmitters in the Bleuler’s assumption that schizophrenia will most

pathogenesis of schizophrenia, but so far, this has probably not have a unitary etiopathogenesis, and

no immediate bearing on the individual diagnostic that several pathogenic factors may converge to a

process.18 Neuro/psychophysiological evidence common final pathway like the disturbance of brain

obtained using sophisticated graph-analytic proce- neurotransmitter functions and brain network

dures to disentangle network structures in func- topologies. While the elucidation of details of these

tional or structural neuroimaging of the brain processes are pending, Bleuler’s formulation of the

indicates that there are complex, inter-individually schizophrenias in the plural form may be an

variable (and probably also time-dynamic) altera- adequate reflection on these findings.

© 2015 The Authors

Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences © 2015 Japanese Society of Psychiatry and Neurology

666 W. Gaebel and J. Zielasek Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 2015; 69: 661–673

the latter receiving due increased attention given the

Deconstructing schizophrenia high disease burden of somatic disorders in people

For elucidating the etiopathogenesis of schizophre- with schizophrenia and its role in excess mortality.36

nia, it may be necessary to focus on the etiopatho- This may be due to late diagnosis and

genesis of specific psychotic symptoms rather than undertreatment, unhealthy lifestyles, and drug side-

on the complex complete clinical picture. While still effects, although it has also been shown that

clinically useful, the concept of ‘schizophrenia’ may adequate use of antipsychotic medication reduces

obfuscate biological markers simply by providing the ‘mortality gap’ of patients with schizophrenia.37

a too heterogenous population of individuals Therefore, any future program to improve the

with similar symptoms but of very different quality of schizophrenia diagnostics will need to

etiopathogenetic background. Genetic and other include the aspect of attention to somatic

(neuro)biological endophenotypes may need to be comorbidity.

identified to establish objective markers of the pro-

cesses leading to particular psychotic symptoms

like hallucinations or delusions.28,29 However,

there will still be a long way from biomarkers/

SCHIZOPHRENIA 2020: TRENDS

endophenotypes to clinical practice.30 The National

IN THERAPY

Institutes of Mental Health has initiated a large-scale Treatment modalities in schizophrenia have changed

research program to develop, for research purposes, with the concepts of schizophrenia over the decades

new ways of classifying mental disorders based on and are currently shaped by the biopsychosocial

dimensions of observable behavior and neurobio- model leading to three pillars of schizophrenia

logical measures. The range of dimensions to be therapy:

assessed encompasses positive and negative valence

systems, cognitive systems, social systems and 1 Biological therapeutic methods employing anti-

arousal/regulatory systems, which will all be psychotic drugs, which act via blockade of brain

assessed in a comprehensive analysis of the genetic dopamine receptors and modulating effects on

backgrounds of these systems, the cellular level, the other brain neurotransmitter systems.

brain network level, physiology, behavior and 2 Psychotherapeutic approaches increasingly

patient self-reports.31 This ambitious project has informed by research on specific psychological

yielded the first information on the pathophysiol- aspects of the pathophysiology of schizophrenia as

ogy of hallucinations,32,33 but whether this ‘Research mentioned before (like aberrant salience and

Domain Criteria’ (RDoC) project will ultimately jumping to conclusions38 and cognitive training

lead to new (and more technology-driven?) classifi- techniques to overcome cognitive impairments,

cation criteria remains to be seen and seems for example of working memory functions).

unlikely to be fully operational for schizophrenia in 3 Psychosocial treatments addressing aspects of

2020. An advantage of this approach is that it may workplace rehabilitation (like supported employ-

provide patient-driven analyses, and genetic-driven ment programs).

analyses, which may then converge on common

pathways of disease development.34 The constraints Current trends in developing new treatments for

imposed upon research by the boundaries of tradi- schizophrenia can be found in five areas:

tional classification concepts, like ‘schizophrenia’,

can be overcome using the RDoC approach. 1 Novel pharmacologic agents

2 Further development of psychotherapy for schizo-

phrenia

Addressing somatic comorbidity in the 3 New somatic therapies like transcranial magnetic

diagnostic process stimulation or deep brain stimulation

A final clinical-practical aspect for the diagnostic 4 Improving the quality of mental health care by

process in patients with schizophrenia is the implementing guidelines and developing more

increased attention to somatic comorbidity. The effective care models

increased mortality of patients with schizophrenia is 5 Developing early need-based, personalized

mainly caused by suicides and somatic disorders35 – interventions.

© 2015 The Authors

Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences © 2015 Japanese Society of Psychiatry and Neurology

Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 2015; 69: 661–673 Schizophrenia in 2020 667

cal practice in order to overcome traditional but

Novel pharmacologic agents outdated nihilistic attitudes towards the psycho-

Current antipsychotic therapy mainly relies on target- therapy of schizophrenia.

ing brain dopamine D2 receptors, but novel drugs are

being developed that work via glutamate receptors,

glycine transporters or the alpha-7-nicotinic acetyl-

New somatic therapies

choline receptor.39 However, so far none of these One of the most promising approaches is the use of

novel approaches has led to therapeutic break- repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS)

throughs. Besides hallucinations and delusions, therapy to control the symptoms of psychosis.

against which the current antipsychotic drugs show However, the therapeutic efficacy of the currently

sufficient activity, new therapeutic targets will be available protocols was limited in controlled, ran-

‘negative’ symptoms like avolition and anhedonia, domized trials,45,46 and treatment effects were vari-

and cognitive symptoms, like working memory able on the different symptom dimensions with

impairments. Another important aspect will be to some notable therapeutic effects for mimic affect rec-

reduce the side-effects of the current antipsychotic ognition.47 It may be hoped that by carefully selecting

drugs, which may lead to dyskinesias, cardiac patients who are likely to respond to rTMS by using

arrhythmias or the metabolic syndrome, all of which clinical profiles or biomarkers, and by optimizing the

frequently limit the clinical acceptance of these drugs. treatment protocols, this therapeutic alternative will

Another aspect is that pharmaceutical companies are become more widely available and acceptable. For

reducing their engagements for antipsychotic drug example, a recent review showed that the stimulation

developments, as developing drugs for brain disor- site and the stimulation type were important for

ders like schizophrenia is complex, time-consuming determining the efficacy of rTMS in reducing the

and expensive, and may thus appear as a less attrac- intensity of auditory hallucinations.48 Another area of

tive area for investment compared to other areas of research is the development of deep brain stimula-

drug development.40 Changing policies that regulate tion (DBS) techniques for the treatment of the symp-

market returns may be one way to address this chal- toms of psychosis. This is mainly driven by the

lenge, and clearly another approach would be to observation that in Parkinson’s disease, the elucida-

provide convincing results about the etiopathogen- tion of disturbed neurocircuitry led to the develop-

esis of schizophrenia to drug developers. Other ment of DBS treatment algorithms. While modeling

aspects could be to establish biomarkers for stratifi- studies showed that in principle this would be a fea-

cation of schizophrenia patients, to develop predic- sible therapeutic approach to correct the disturbed

tive models and to enhance data sharing and brain network topology in schizophrenia,19 it

collaboration.41 Such measures are urgently needed remains to be determined which patients may profit

to ascertain the future of drug development for the and to address the potential side-effects of such new

treatment of schizophrenia. therapies. Obviously, the invasiveness of the proce-

dure will be an issue and the emerging ethical issues

about invasive brain procedures in patients with psy-

Further development of psychotherapy chotic disorders need to be addressed.

for schizophrenia

In the last 20 years, a number of studies have shown

that cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy is effective

Improving health care for people

to reduce the symptoms of schizophrenia, especially

with schizophrenia

when combined with antipsychotic drug therapy, While the previous sections have shown that the

while psychodynamic therapy is not effective.42 Prog- developments of new pharmacologic antipsychotic

ress in the area of psychological therapies for schizo- agents, of new psychotherapeutic methods and of

phrenia is currently emerging in that there is evidence new somatic therapies addressing the disturbed

for psychotherapeutic treatment of specific symp- neurocircuitry in schizophrenia are underway, none

toms of psychosis like auditory hallucinations43 or of these approaches is promising to provide short-

mimic affect recognition.44 An important aspect will term success on a broad basis before 2020. Therefore,

be to implement such new psychotherapeutic strate- alternatives are needed that may be more readily

gies in schizophrenia health care and everyday clini- available and one area of potential improvement of

© 2015 The Authors

Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences © 2015 Japanese Society of Psychiatry and Neurology

668 W. Gaebel and J. Zielasek Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 2015; 69: 661–673

the diagnosis and therapy of schizophrenia is the 4 Offer individualized, need-adapted and stage-

optimization of the use of the currently available specific combinations of diagnostic and treatment

evidence and therapeutic methods. First, there is still modules

a treatment gap indicating that only about half of all 5 Provide a ‘holistic’, person- and recovery-centered

patients with schizophrenia receive treatment. This approach addressing clinical symptoms, func-

could be addressed by information campaigns about tional abilities, quality of life, mental health lit-

the nature and symptoms of the disorder, the avail- eracy, trust in services and empowerment for the

able treatment options and the mental health-care patient and his/her family.

services, which provide such services. Improving trust

in mental health-care services may be a central issue Such novel models of mental health care for

here, as was shown by a recent review and recom- schizophrenia can be conceptualized integrating the

mendations to increase trust in mental health-care biopsychosocial model (Fig. 4).

services developed in the framework of the Guidance This could then be used to devise an integrated

Project of the European Psychiatric Association.49 care model for patients with schizophrenia based

Along this line of reasoning, fighting stigma and dis- on evidence-informed diagnostic and treatment

crimination of people with mental disorders and the modules that transgress traditional boundaries of in-

people and institutions providing mental health care and outpatient care sectors, and which are tailored to

will be important elements of such programs.50 the disease-stage-specific needs of the individual

(Fig. 5).

Improving the quality of mental health care by These needs may vary greatly over time and the

implementing guidelines main advantage of such a modular system is its flex-

ibility and adaptiveness to the most current mental

Another aspect will be to implement existing guide-

health care needs of the individual affected by schizo-

lines, which summarize the available evidence and

phrenia. It is also adaptable to different health-care

provide recommendations for clinical practice.

systems, in that different (national) mental health-

Schizophrenia guidelines are available worldwide51

care systems may adopt different diagnostic or treat-

and there is a need to increase their implementation

ment contents in the various models, considering the

in clinical practice and to evaluate the efficacy of their

regional or national availability of mental health-care

implementation. Research in this field is scarce but

service types, traditions of mental health care and the

indicates that guideline implementation and guide-

continuous evaluation of novel treatment strategies

line adherence improve the outcome of schizophre-

in schizophrenia. Therefore, the contents of the

nia health care.52,53

modules will have to be reviewed and adapted con-

stantly following new evidence or the introduction of

A novel health-care model for schizophrenia new service types.

Optimally, guideline implementation would be part

of a more comprehensive model to implement best-

evidence practices in mental health care, which may

Early need-based, personalized interventions

also include developing new structures like enhanced A final aspect regarding the mental health care aspect

outpatient services and to tailor the therapeutic which bridges into the area of basic research into the

program to patients’ individual – and time-variable – etiopathogenesis of schizophrenia is the develop-

needs. Such models may also help to close the treat- ment of personalized interventions in the early phase

ment gap, which indicates that approximately half of of the disorder with a view to either completely

all persons in need of schizophrenia treatment actu- prevent or considerably ameliorate the initial phase

ally receive treatment.54 Such a new care model of psychosis. Currently, the clinical criteria for the

should: early phases of schizophrenia are being refined, but

biomarkers allowing individual risk predictions

1 Be evidence-based and should be used to transfer would be needed to bring about decisive progress in

scientific progress quickly into clinical practice this field.55 One promising approach is to use cranial

2 Use all levels of information sources neuroimaging data of persons at risk of developing

3 Form an integrated network of local mental schizophrenia, and use machine-learning algorithms

health-care providers to obtain computerized predictions based on

© 2015 The Authors

Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences © 2015 Japanese Society of Psychiatry and Neurology

Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 2015; 69: 661–673 Schizophrenia in 2020 669

Bio Psycho Social

Level of Personal and

Etiology Psychological

information mental health-care

Pathophysiology mechanisms

source system level

New therapies developed New therapies developed New therapies addressing

based on novel based on findings about recovery and empowerment,

Examples mechanisms of etiology the role of cognitive including and going beyond

of novel and pathophysiology, like processes in symptom classical outcome assessments

approaches information on brain formation like symptom assessments

network disturbances in Demonstrated efficacy of

schizophrenia elements of mental health care

like CMHT or supported

employment

Resulting Deep brain stimulation Cognitive training Comprehensive Community

health-care rTMS treatment for negative symptoms Mental Health Centers,

modules Assertive Community

Treatment, home treatment,

crisis intervention,

psychoeducation and

empowerment training

Figure 4. The biopsychosocial foundations of a novel health-care model for schizophrenia. CMHT, community mental health

treatment; rTMS, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation.

Examples of modules:

Acute Module Remission-stabilizing Chronic Phase Module

(e.g., clarification of Module (e.g., cognitive training,

Relapse Module

differential (e.g., home supported employment,

(e.g., crisis

diagnosis, initiation treatment if patient rehabilitation modules to

intervention)

of antipsychotic does not attend to assess and improve recovery

medication) appointments) and empowerment)

In-patient Out-patient In-patient Out-patient

Symptom First

severity episode

Relapse

Diagnostic

threshold

Partial Note that modules transgress

remission traditional boundaries of in-

and out-patient health-care

service sectors

Time [years]

Figure 5. Course-stage specific, individualized modular mental health-care model for schizophrenia.

© 2015 The Authors

Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences © 2015 Japanese Society of Psychiatry and Neurology

670 W. Gaebel and J. Zielasek Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 2015; 69: 661–673

biomarkers.56 Transition outcomes can be correctly hundred genes identified as being associated with

predicted in about 80% of cases with the current schizophrenia, only one to two may be expected

techniques, but clearly this needs to be improved to yield useful targets for novel therapeutic

probably by using combinations of biomarkers in approaches.59 Estimations based on neuroimaging

order to become clinically more useful. Clinical data indicate that there may be 100–1000 ‘hubs’,

investigations show that there is a long prodromal which are brain centers connecting the ‘modules’ of

phase of many years before overt psychosis occurs, the brain, and that there may be on the order of 5000

and cognitive impairments and negative symptoms to 5 million connections within modules and

like depression or avolition may be present earlier between hubs that will need to be assessed.21 Another

than ‘positive’ symptoms like hallucinations and aspect is that it will be necessary to not only analyze

delusions. Together with neuroimaging data, these biomarkers horizontally, that is, comparing healthy

clinical features suggest that there is a prodromal controls with persons with schizophrenia, but also

period antedating the dopamine-induced psychotic vertically, that is, comparing whole sets of

state by many years, and that this prodromal phase biomarkers in individuals with and without schizo-

may be an opportunity for preventing disease pro- phrenia.30 Such combinatorial assessments may be

gression.57 The challenge here is the identification of guided by target-identified objectives focusing, for

persons at a high risk of developing schizophrenia, example, in one combinatorial study on synaptic

and to determine which therapeutic approaches are protein, synaptic functions and ensuing network

safe and effective at this disease stage. alterations, and in others focusing on immunological

aspects. Thus, several critical open questions remain:

CONCLUSIONS • How can a coherent picture be conceptualized

The following four conceptual trends have become given the highly complex, time-variable and

evident from this review of the current state of the art interindividually variable (neuro)biologic under-

and foreseeable future developments of the diagno- pinnings of schizophrenia?

sis, classification and therapy of schizophrenia: • How can compensatory mechanisms be distin-

guished from etiopathogenic factors?

• The main informant for concepts, classification • How can this information be used in individual

and treatment will be research results on the etio- clinical cases to improve diagnosis or the selection

pathogenesis of schizophrenia. of the most effective therapeutic modalities?

• Personalized early recognition using neuroimaging

will become a reality. Probably, deconstructing schizophrenia using the

• Mental health care optimization will lead to RDoC approach in combination with improved

improved outcomes. mental health care will be shaping the development

• There will be no utterly new principles of schizo- of schizophrenia diagnosis and therapy until 2020.

phrenia concepts – but more and better evidence This phase will also be shaped by the current insight

for the current biopsychosocial conceptualization that there is a bidirectional relation between sophis-

of all mental disorders, including schizophrenia, ticated advances in the diagnosis and treatment of

will emerge. schizophrenia, and the mental health-care system in

the community: Scientific advances will change

A major challenge will be to integrate the findings mental health-care systems, and reforms in the

from genetic research, neuroimaging, neurophysi- mental health-care systems will enhance scientific

ological studies and clinical trials into an evolving advances, for example by providing access for more

coherent picture of the etiopathogenesis, classifica- people with schizophrenia to modern treatment

tion and treatment of schizophrenia. Different modalities and broadening the experience base about

methods of investigation and studies across tradi- the clinical use of innovative treatments.

tional diagnostic boundaries will be necessary to In summary, the following conclusions can be

unravel the etiopathogenesis of the symptoms of drawn:

schizophrenia, to develop new classification criteria

that employ biomarkers, and to target therapy to • Even following the recent revisions of the classifi-

such disturbed neurobiological functions.34,58 Of the cation criteria of schizophrenia in DSM-5 and ICD-

© 2015 The Authors

Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences © 2015 Japanese Society of Psychiatry and Neurology

Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 2015; 69: 661–673 Schizophrenia in 2020 671

11, in 2020, schizophrenia will remain a clinically 2. Tandon R, Gaebel W, Barch DM et al. Definition and

defined primary psychotic disorder. description of schizophrenia in the DSM-5. Schizophr. Res.

• Treatment can still be improved with new antipsy- 2013; 150: 3–10.

chotic drugs, drugs addressing negative symptoms, 3. Gaebel W, Zielasek J, Cleveland HR. Classifying psychosis

– challenges and opportunities. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2012;

new treatment modalities like rTMS and by

24: 538–548.

improving early detection and prevention. 4. Gaebel W, Zielasek J, Cleveland HR. Psychotic disorders in

• New research insights into the etiopathogenesis of ICD-11. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2013; 6: 263–265.

schizophrenia are promising to improve diagnosis, 5. Nordgaard J, Arnfred SM, Handest P, Parnas J. The diag-

classification and therapy in the future, although a nostic status of first-rank symptoms. Schizophr. Bull. 2008;

picture of complex brain dysfunction is emerging 34: 137–154.

requiring sophisticated mathematical methods of 6. Wilson JE, Niu K, Nicolson SE, Levine SZ, Heckers S. The

analysis. diagnostic criteria and structure of catatonia. Schizophr.

• The challenge is to develop comprehensive diag- Res. 2015; 164: 256–262.

nostic and treatment modules individually tailored 7. Tsuang MT, Van Os J, Tandon R et al. Attenuated psychosis

to the time-variable needs of patients and their syndrome in DSM-5. Schizophr. Res. 2013; 150: 31–35.

8. Schultze-Lutter F, Michel C, Ruhrmann S, Schimmelmann

families.

BG. Prevalence and clinical significance of DSM-5-

attenuated psychosis syndrome in adolescents and young

Schizophrenia has been and will be a developing adults in the general population: The Bern Epidemiologi-

construct, which has diagnostic, prognostic and cal At-Risk (BEAR) study. Schizophr. Bull. 2014; 40: 1499–

therapy-indicating values and can therefore currently 1508.

not be abandoned. However, the road is now open 9. Chen C, Cheng L, Grennan K et al. Two gene co-expression

and the techniques and methods are available to modules differentiate psychotics and controls. Mol. Psy-

deconstruct schizophrenia based on symptoms or chiatry 2013; 18: 1308–1314.

biomarkers, which will hopefully lead to innovative 10. Hiroi N, Takahashi T, Hishimoto A, Izumi T, Boku S,

and improved diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. Hiramoto T. Copy number variation at 22q11.2: From

Besides deconstructing schizophrenia and using com- rare variants to common mechanisms of developmental

neuropsychiatric disorders. Mol. Psychiatry 2013; 18:

binatorial biomarker approaches, pragmatically

1153–1165.

closing the existing treatment gap and improving the 11. Ripke S, O’Dushlaine C, Chambert K et al. Genome-wide

quality of schizophrenia mental and somatic health association analysis identifies 13 new risk loci for schizo-

care are attainable goals for the next 5 years. phrenia. Nat. Genet. 2013; 45: 1150–1159.

12. Schwab SG, Wildenauer DB. Genetics of psychiatric disor-

ders in the GWAS era: An update on schizophrenia. Eur.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2013; 263 (Suppl. 2): S147–

S154.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest pertain-

13. Xu B, Ionita-Laza I, Roos JL et al. De novo gene mutations

ing to the preparation of this manuscript or its con- highlight patterns of genetic and neural complexity in

tents. W.G. has received symposia support from schizophrenia. Nat. Genet. 2012; 44: 1365–1369.

Janssen-Cilag GmbH, Neuss, Lilly Deutschland 14. Deakin J, Lennox BR, Zandi MS. Antibodies to the

GmbH, Bad Homburg, Servier Deutschland GmbH, N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor and other synaptic pro-

Munich and Sanofi-Aventis Deutschland GmbH, teins in psychosis. Biol. Psychiatry 2014; 75: 284–291.

Frankfurt am Main. W.G. is a member of the Faculty 15. Needham E, Zandi MS. Recent advances in the

of the Lundbeck International Neuroscience Foun- neuroimmunology of cell-surface CNS autoantibody syn-

dation (LINF), Denmark. J.Z. has received an author dromes, Alzheimer’s disease, traumatic brain injury and

honorarium for a review article by Servier Medical schizophrenia. J. Neurol. 2014; 261: 2037–2042.

Publishing. 16. Zandi MS, Deakin JB, Morris K et al. Immunotherapy for

patients with acute psychosis and serum N-Methyl

D-Aspartate receptor (NMDAR) antibodies: A description

of a treated case series. Schizophr. Res. 2014; 160: 193–195.

REFERENCES 17. Howes OD, Kapur S. A neurobiological hypothesis

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical for the classification of schizophrenia: Type A

Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edn. American Psychiatric (hyperdopaminergic) and type B (normodopaminergic).

Publishing, Arlington, WA, 2013. Br. J. Psychiatry 2014; 205: 1–3.

© 2015 The Authors

Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences © 2015 Japanese Society of Psychiatry and Neurology

672 W. Gaebel and J. Zielasek Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 2015; 69: 661–673

18. Wijtenburg SA, Yang S, Fischer BA, Rowland LM. In vivo 35. Saha S, Chant D, McGrath J. A systematic review of mor-

assessment of neurotransmitters and modulators with tality in schizophrenia: Is the differential mortality gap

magnetic resonance spectroscopy: Application to schizo- worsening over time? Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2007; 64:

phrenia. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2015; 51C: 276–295. 1123–1131.

19. Deco G, Kringelbach ML. Great expectations: Using 36. Anthes E. Live faster, die younger. Nature 2014; 508: S16–

whole-brain computational connectomics for understand- S17.

ing neuropsychiatric disorders. Neuron 2014; 84: 892– 37. Cullen BA, McGinty EE, Zhang Y et al. Guideline-

905. concordant antipsychotic use and mortality in schizophre-

20. Zielasek J, Gaebel W. Modern modularity and the road nia. Schizophr. Bull. 2013; 39: 1159–1168.

towards a modular psychiatry. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. 38. Sarin F, Wallin L. Cognitive model and cognitive behavior

Neurosci. 2008; 258 (Suppl. 5): 60–65. therapy for schizophrenia: An overview. Nord. J. Psychiatry

21. Fornito A, Zalesky A, Breakspear M. The connectomics of 2014; 68: 145–153.

brain disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2015; 16: 159–172. 39. Dunlop J, Brandon NJ. Schizophrenia drug discovery and

22. Winton-Brown TT, Fusar-Poli P, Ungless MA, Howes OD. development in an evolving era: Are new drug targets

Dopaminergic basis of salience dysregulation in psycho- fulfilling expectations? J. Psychopharmacol. 2015; 29: 230–

sis. Trends Neurosci. 2014; 37: 85–94. 238.

23. Garety PA, Freeman D. The past and future of delusions 40. Choi DW, Armitage R, Brady LS et al. Medicines for the

research: From the inexplicable to the treatable. Br. J. Psy- mind: Policy-based ‘pull’ incentives for creating break-

chiatry 2013; 203: 327–333. through CNS drugs. Neuron 2014; 84: 554–563.

24. Eifler S, Rausch F, Schirmbeck F et al. Neurocognitive capa- 41. Pankevich DE, Altevogt BM, Dunlop J, Gage FH, Hyman

bilities modulate the integration of evidence in schizo- SE. Improving and accelerating drug development for

phrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2014; 219: 72–78. nervous system disorders. Neuron 2014; 84: 546–553.

25. Castellani CA, Melka MG, Diehl EJ, Laufer BI, O’Reilly RL, 42. Huhn M, Tardy M, Spineli LM et al. Efficacy of pharmaco-

Singh SM. DNA methylation in psychosis: Insights into therapy and psychotherapy for adult psychiatric disorders:

aetiology and treatment. Epigenomics 2015; 7: 67–74. A systematic overview of meta-analyses. JAMA Psychiatry

26. Akdeniz C, Tost H, Meyer-Lindenberg A. The neurobiol- 2014; 71: 706–715.

ogy of social environmental risk for schizophrenia: An 43. Thomas N, Hayward M, Peters E et al. Psychological thera-

evolving research field. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. pies for auditory hallucinations (voices): Current status

2014; 49: 507–517. and key directions for future research. Schizophr. Bull.

27. Haddad L, Schäfer A, Streit F et al. Brain structure corre- 2014; 40 (Suppl. 4): S202–S212.

lates of urban upbringing, an environmental risk factor for 44. Drusch K, Stroth S, Kamp D, Frommann N, Wölwer W.

schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2015; 41: 115–122. Effects of Training of Affect Recognition on the recogni-

28. Allardyce J, Gaebel W, Zielasek J, van Os J. Deconstructing tion and visual exploration of emotional faces in schizo-

Psychosis conference February 2006: The validity of phrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2014; 159: 485–490.

schizophrenia and alternative approaches to the classifica- 45. Hovington CL, McGirr A, Lepage M, Berlim MT. Repetitive

tion of psychosis. Schizophr. Bull. 2007; 33: 863–867. transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) for treating

29. Braff DL, Freedman R, Schork NJ, Gottesman II. major depression and schizophrenia: A systematic review

Deconstructing schizophrenia: An overview of the use of of recent meta-analyses. Ann. Med. 2013; 45: 308–

endophenotypes in order to understand a complex disor- 321.

der. Schizophr. Bull. 2007; 33: 21–32. 46. Wobrock T, Guse B, Cordes J et al. Left prefrontal high-

30. Pickard BS. Schizophrenia biomarkers: Translating the frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for

descriptive into the diagnostic. J. Psychopharmacol. 2015; the treatment of schizophrenia with predominant nega-

29: 138–143. tive symptoms: A sham-controlled, randomized multi-

31. Morris SE, Cuthbert BN. Research Domain Criteria: Cog- center trial. Biol. Psychiatry 2015; 77: 978–988.

nitive systems, neural circuits, and dimensions of behav- 47. Wölwer W, Lowe A, Brinkmeyer J et al. Repetitive

ior. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2012; 14: 29–37. transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) improves facial

32. Badcock JC, Hugdahl K. A synthesis of evidence on inhibi- affect recognition in schizophrenia. Brain Stimul. 2014; 7:

tory control and auditory hallucinations based on the 559–563.

Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) framework. Front. 48. Slotema CW, Blom JD, van Lutterveld R, Hoek HW,

Hum. Neurosci. 2014; 8: 180. Sommer IE. Review of the efficacy of transcranial magnetic

33. Ford JM, Morris SE, Hoffman RE et al. Studying hallucina- stimulation for auditory verbal hallucinations. Biol. Psy-

tions within the NIMH RDoC framework. Schizophr. Bull. chiatry 2014; 76: 101–110.

2014; 40 (Suppl. 4): S295–S304. 49. Gaebel W, Muijen M, Baumann AE et al. EPA guidance on

34. Owen MJ. New approaches to psychiatric diagnostic clas- building trust in mental health services. Eur. Psychiatry

sification. Neuron 2014; 84: 564–571. 2014; 29: 83–100.

© 2015 The Authors

Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences © 2015 Japanese Society of Psychiatry and Neurology

Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 2015; 69: 661–673 Schizophrenia in 2020 673

50. Gaebel W, Zielasek J. Overcoming stigmatizing attitudes 55. Barker-Haliski M, Friedman D, White HS, French JA. How

towards psychiatrists and psychiatry. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. clinical development can, and should, inform transla-

2015; 131: 5–7. tional science. Neuron 2014; 84: 582–593.

51. Gaebel W, Riesbeck M, Wobrock T. Schizophrenia guide- 56. Koutsouleris N, Riecher-Rössler A et al. Detecting the psy-

lines across the world: A selective review and comparison. chosis prodrome across high-risk populations using neu-

Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2011; 23: 379–387. roanatomical biomarkers. Schizophr. Bull. 2015; 41: 471–

52. Miller AL, Crismon ML, Rush AJ et al. The Texas medica- 482.

tion algorithm project: Clinical results for schizophrenia. 57. Kahn RS, Sommer IE. The neurobiology and treatment of

Schizophr. Bull. 2004; 30: 627–647. first-episode schizophrenia. Mol. Psychiatry 2015; 20:

53. Weinmann S, Hoerger S, Erath M, Kilian R, Gaebel W, 84–97.

Becker T. Implementation of a schizophrenia practice 58. Krystal JH, State MW. Psychiatric disorders: Diagnosis to

guideline: Clinical results. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2008; 69: therapy. Cell 2014; 157: 201–214.

1299–1306. 59. Schubert CR, Xi HS, Wendland JR, O’Donnell P. Translat-

54. Kohn R, Saxena S, Levav I, Saraceno B. The treatment gap ing human genetics into novel treatment targets for

in mental health care. Bull. WHO 2004; 82: 858–866. schizophrenia. Neuron 2014; 84: 537–541.

© 2015 The Authors

Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences © 2015 Japanese Society of Psychiatry and Neurology

You might also like

- Van Os J, Kapur S. Schizophrenia - Lancet 2009 374 635-45 PDFDocument11 pagesVan Os J, Kapur S. Schizophrenia - Lancet 2009 374 635-45 PDFVictorVeroneseNo ratings yet

- Psychiatric diagnosis and treatment in the 21st century: incremental integration versus paradigm shiftsDocument22 pagesPsychiatric diagnosis and treatment in the 21st century: incremental integration versus paradigm shiftsLucas DistelNo ratings yet

- Psychedelic-Assisted Psychotherapy: A Paradigm Shift in Psychiatric Research and DevelopmentDocument11 pagesPsychedelic-Assisted Psychotherapy: A Paradigm Shift in Psychiatric Research and DevelopmentIago LôboNo ratings yet

- Schizophr Bull 2007 Regier 843 5Document3 pagesSchizophr Bull 2007 Regier 843 5András SzabóNo ratings yet

- Material DisertatieDocument6 pagesMaterial DisertatievioletaNo ratings yet

- Ensefalitis Dan PsikosisDocument15 pagesEnsefalitis Dan PsikosisLhia PrisciliiaNo ratings yet

- Schizophrenia: Epidemiology, Causes, Neurobiology, Pathophysiology, and TreatmentDocument37 pagesSchizophrenia: Epidemiology, Causes, Neurobiology, Pathophysiology, and TreatmentAngela EnacheNo ratings yet

- VolkanKevin 2020Schizophrenia-EpidemiologyCausesNeurobiologyPathophysiologyandTreatment In-JournalofHealthandMedicalSciencesVol 3no 4487-521Document37 pagesVolkanKevin 2020Schizophrenia-EpidemiologyCausesNeurobiologyPathophysiologyandTreatment In-JournalofHealthandMedicalSciencesVol 3no 4487-521Kirey UllimazNo ratings yet

- Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria: PsychiatryDocument23 pagesRevista Brasileira de Psiquiatria: Psychiatryputri weniNo ratings yet

- Dimensional PsychopathologyFrom EverandDimensional PsychopathologyMassimo BiondiNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Schizophrenia PDFDocument10 pagesJurnal Schizophrenia PDFfathiyyahnurulNo ratings yet

- Schizoaffective Disorder: Continuing Education ActivityDocument10 pagesSchizoaffective Disorder: Continuing Education ActivitymusdalifahNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology of Negative Symptoms Dimensions of SchizophreniaDocument15 pagesPathophysiology of Negative Symptoms Dimensions of Schizophreniafelix08121992No ratings yet

- Review of Related Literature of SchizophreniaDocument6 pagesReview of Related Literature of Schizophreniac5rqq644100% (1)

- Seminar: Jonathan Posner, Guilherme V Polanczyk, Edmund Sonuga-BarkeDocument13 pagesSeminar: Jonathan Posner, Guilherme V Polanczyk, Edmund Sonuga-BarkeCristinaNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Impairment in Schizophrenia: A Review of Key FindingsDocument28 pagesCognitive Impairment in Schizophrenia: A Review of Key FindingsErinaTandirerungNo ratings yet

- Diedrich Voderholzer Review OCPD PrintDocument11 pagesDiedrich Voderholzer Review OCPD PrintAbid AliNo ratings yet

- 07 Clinical Assessment Diagnosis & TreatmentDocument39 pages07 Clinical Assessment Diagnosis & TreatmentSteven T.No ratings yet

- NIH Public AccessDocument12 pagesNIH Public AccessFajar Rudy QimindraNo ratings yet

- 2019 Acute and Transient Psychotic Disorders - Newer UnderstandingDocument11 pages2019 Acute and Transient Psychotic Disorders - Newer Understandingjuliana izquierdoNo ratings yet

- Developmental PSYCH ActivityDocument2 pagesDevelopmental PSYCH ActivityHallia ParkNo ratings yet

- Deconstructing PsychosisDocument8 pagesDeconstructing PsychosisEvets DesouzaNo ratings yet

- Development of DSM-V and ICD-11 Tendencies and Potential of New ClassificationsDocument18 pagesDevelopment of DSM-V and ICD-11 Tendencies and Potential of New Classificationsfabiola.ilardo.15No ratings yet

- ICD-11 Mental Disorder RevisionDocument27 pagesICD-11 Mental Disorder RevisionFlorin IonutNo ratings yet

- A Randomized Controlled Trial of A Mindfulness-Based Intervention Program For People With Schizophrenia: 6-Month Follow-UpDocument14 pagesA Randomized Controlled Trial of A Mindfulness-Based Intervention Program For People With Schizophrenia: 6-Month Follow-UpOrion OriNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0965229920306270 MainDocument15 pages1 s2.0 S0965229920306270 Mainstevenburrow06No ratings yet

- 10yr F-U Psychosis - 2017-World - PsychiatryDocument3 pages10yr F-U Psychosis - 2017-World - Psychiatryscribd4kmhNo ratings yet

- The Clinical Characterization of The Patient With Primary Psychosis Aimed at Personalization of ManagementDocument30 pagesThe Clinical Characterization of The Patient With Primary Psychosis Aimed at Personalization of ManagementDaniel ZalewskiNo ratings yet

- Artigo EsquizofreniaDocument26 pagesArtigo EsquizofreniaJulio CesarNo ratings yet

- Discuss Issues Associated With The Classification andDocument3 pagesDiscuss Issues Associated With The Classification andAkshay NayakNo ratings yet

- Psychology - Syllabus and Keynotes of Psychopathology For PG 2nd Semester Session 2018-20Document13 pagesPsychology - Syllabus and Keynotes of Psychopathology For PG 2nd Semester Session 2018-20abhi_kr84No ratings yet

- Journal of Psychosomatic Research: Katharina Schieber, Ines Kollei, Martina de Zwaan, Alexandra MartinDocument5 pagesJournal of Psychosomatic Research: Katharina Schieber, Ines Kollei, Martina de Zwaan, Alexandra MartinJuanNo ratings yet

- Review: Major Depressive Disorder in Dsm-5: Implications For Clinical Practice and Research of Changes From Dsm-IvDocument13 pagesReview: Major Depressive Disorder in Dsm-5: Implications For Clinical Practice and Research of Changes From Dsm-IvCarlos GardelNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Depression Symptoms Between Primary Depression and Secondary-To-Schizophrenia DepressionDocument5 pagesComparison of Depression Symptoms Between Primary Depression and Secondary-To-Schizophrenia DepressionnatashiaNo ratings yet

- Tavistock and Portman E-Prints Online: Journal Article Original CitationDocument13 pagesTavistock and Portman E-Prints Online: Journal Article Original CitationDarkAnqelNo ratings yet

- A Review of Schizophrenia Research in Malaysia: Chee Kok Yoon, Mmed (Psych), Salina Abdul Aziz, Mmed (Psych)Document9 pagesA Review of Schizophrenia Research in Malaysia: Chee Kok Yoon, Mmed (Psych), Salina Abdul Aziz, Mmed (Psych)Amir Arif RoslanNo ratings yet

- DSM 5 TR What's NewDocument2 pagesDSM 5 TR What's NewRafael Gaede Carrillo100% (1)

- Download Schizophrenia And Psychiatric Comorbidities Recognition Management Oxford Psychiatry Library Series 1St Edition David J Castle all chapterDocument68 pagesDownload Schizophrenia And Psychiatric Comorbidities Recognition Management Oxford Psychiatry Library Series 1St Edition David J Castle all chapterroy.nogle598100% (5)

- WFSBP Treatment Guidelines Dementia PDFDocument31 pagesWFSBP Treatment Guidelines Dementia PDFALLNo ratings yet

- 404 1609 1 PBDocument5 pages404 1609 1 PBRohamonangan TheresiaNo ratings yet

- Classification of Mental Disorders: Prepared By: Ms. Snehal Kapadiya M.SC (N) AconDocument26 pagesClassification of Mental Disorders: Prepared By: Ms. Snehal Kapadiya M.SC (N) AconAhmed Abdel-naserNo ratings yet

- Review of Obsessive-Compulsive Personality DisorderDocument10 pagesReview of Obsessive-Compulsive Personality DisorderClaudia AranedaNo ratings yet

- Ijms 22 09309Document22 pagesIjms 22 09309John SmithNo ratings yet

- Agitasi Di ADDocument9 pagesAgitasi Di ADnurulnadyaNo ratings yet

- Schizophrenia Stigma in Mental Health Professionals and Associated Factors A Systematic ReviewDocument1 pageSchizophrenia Stigma in Mental Health Professionals and Associated Factors A Systematic ReviewFrida Ximena Perez CaballeroNo ratings yet

- Esquizo ITP 2011Document4 pagesEsquizo ITP 2011DrMartens AGNo ratings yet

- Executive Dysfunctions in Schizophrenia: A Critical Review of Traditional, Ecological, and Virtual Reality AssessmentsDocument26 pagesExecutive Dysfunctions in Schizophrenia: A Critical Review of Traditional, Ecological, and Virtual Reality Assessmentslolocy LNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Brain Imaging in PsychiatryDocument8 pagesDiagnostic Brain Imaging in PsychiatryalexNo ratings yet

- Schizopherian and Risk To DementiaDocument9 pagesSchizopherian and Risk To DementiaAura DiscyacittaNo ratings yet

- Understanding ADHD: Diagnosis, Causes, and Treatment ChallengesDocument26 pagesUnderstanding ADHD: Diagnosis, Causes, and Treatment ChallengesJhonny Prambudi BatongNo ratings yet

- Fifteen-Year Follow-Up of ICD-10 Schizoaffective Disorders Compared With Schizophrenia and Affective DisordersDocument9 pagesFifteen-Year Follow-Up of ICD-10 Schizoaffective Disorders Compared With Schizophrenia and Affective Disordersdr.cintaNo ratings yet

- Holistic Management of Schizophrenia Symptoms Using Pharmacological and Non-Pharmacological TreatmentDocument9 pagesHolistic Management of Schizophrenia Symptoms Using Pharmacological and Non-Pharmacological TreatmenttiaranadyaNo ratings yet

- Neuroimaging of Schizophrenia and Other Primary Psychotic Disorders: Achievements and PerspectivesFrom EverandNeuroimaging of Schizophrenia and Other Primary Psychotic Disorders: Achievements and PerspectivesNo ratings yet

- DSM 5 Changes in Child Psychiatric DisordersDocument5 pagesDSM 5 Changes in Child Psychiatric DisordersFelipe Andrés Ruiz PérezNo ratings yet

- The Incremental Value of Neuropsychological Assessment: A Critical ReviewDocument33 pagesThe Incremental Value of Neuropsychological Assessment: A Critical ReviewJose Alonso Aguilar ValeraNo ratings yet

- A Five-Factor Model of Psychosis With The Mmpi-2-RfDocument49 pagesA Five-Factor Model of Psychosis With The Mmpi-2-RfskafonNo ratings yet

- 2013 DefdesDocument8 pages2013 DefdesDedy Gunawan BaringbingNo ratings yet

- Schizophrenia: Epidemiology of Mental Disorders and Psychosocial ProblemsDocument149 pagesSchizophrenia: Epidemiology of Mental Disorders and Psychosocial ProblemsAsif Raza SoomroNo ratings yet

- DSM 5 Mood DisorderDocument9 pagesDSM 5 Mood DisorderErlin IrawatiNo ratings yet

- Healy 1994Document9 pagesHealy 1994Doc HadiNo ratings yet

- Garlow 2013Document5 pagesGarlow 2013Doc HadiNo ratings yet

- CESD-10 Website PDFDocument3 pagesCESD-10 Website PDFDoc HadiNo ratings yet

- Gibbons 2012Document8 pagesGibbons 2012Doc HadiNo ratings yet

- QEEG Abnormalities in Psychiatric Settings: Neurofeedback Clinical TrainingDocument63 pagesQEEG Abnormalities in Psychiatric Settings: Neurofeedback Clinical TrainingDoc HadiNo ratings yet

- Differences in cognitive function between elderly with good and poor sleep qualityDocument12 pagesDifferences in cognitive function between elderly with good and poor sleep qualityDoc HadiNo ratings yet

- Rehabilitasi Medis Untuk GSA - Dr. LuhDocument32 pagesRehabilitasi Medis Untuk GSA - Dr. LuhDoc HadiNo ratings yet

- Psychiatric con-WPS OfficeDocument1 pagePsychiatric con-WPS OfficeDoc HadiNo ratings yet

- A Local Review of Child Abuse in HongDocument12 pagesA Local Review of Child Abuse in HongDoc HadiNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Impairment and Personality Traits in Epilepsy (2.6)Document6 pagesCognitive Impairment and Personality Traits in Epilepsy (2.6)Doc HadiNo ratings yet

- 672 The Maudsle-WPS OfficeDocument1 page672 The Maudsle-WPS OfficeDoc HadiNo ratings yet

- Early Post-Stroke Depression and Mortality: Meta-Analysis and Meta-RegressionDocument7 pagesEarly Post-Stroke Depression and Mortality: Meta-Analysis and Meta-RegressionDoc HadiNo ratings yet

- CESD-10 Website PDFDocument3 pagesCESD-10 Website PDFDoc HadiNo ratings yet

- A Local Review of Child Abuse in HongDocument12 pagesA Local Review of Child Abuse in HongDoc HadiNo ratings yet

- JurnalDocument8 pagesJurnalDoc HadiNo ratings yet

- SJMMS 4 206Document6 pagesSJMMS 4 206Doc HadiNo ratings yet

- Journal 1 PDFDocument8 pagesJournal 1 PDFpososuperNo ratings yet

- Comparison FFP2 KN95 N95 Filtering Facepiece Respirator Classes PDFDocument3 pagesComparison FFP2 KN95 N95 Filtering Facepiece Respirator Classes PDFazsigncNo ratings yet

- Appi Ps 201800073Document3 pagesAppi Ps 201800073Doc HadiNo ratings yet

- Trust and Acceptance of A Virtual Psychiatric Interview Between Embodied Conversational Agents and OutpatientsDocument7 pagesTrust and Acceptance of A Virtual Psychiatric Interview Between Embodied Conversational Agents and OutpatientsDoc HadiNo ratings yet

- Taking Legal Histories in Psychiatric AssessmentsDocument3 pagesTaking Legal Histories in Psychiatric AssessmentsDoc HadiNo ratings yet

- Horsdal2017-Metabolic Profile at First-Time Schizophrenia Diagnosis A PopulatDocument10 pagesHorsdal2017-Metabolic Profile at First-Time Schizophrenia Diagnosis A PopulatDoc HadiNo ratings yet

- What Does Schizophrenia Teach Us About AntipsikotikDocument5 pagesWhat Does Schizophrenia Teach Us About AntipsikotikDoc HadiNo ratings yet

- Document-WPS OfficeDocument1 pageDocument-WPS OfficeDoc HadiNo ratings yet

- Prakash Nayi V State of Goa 2023Document20 pagesPrakash Nayi V State of Goa 2023Alaparthi AshrithaNo ratings yet

- Revisiting the concept of unitary psychosisDocument14 pagesRevisiting the concept of unitary psychosiscorpus delicti100% (1)

- CENE Course Outline On Psychiatric NursingDocument3 pagesCENE Course Outline On Psychiatric NursingJohn Ryan BuenaventuraNo ratings yet

- Mental ExamDocument31 pagesMental ExamMaryann LayugNo ratings yet

- Part 1 Sample Questions MRCPDocument33 pagesPart 1 Sample Questions MRCPCharan Pal Singh100% (1)

- Corticosteroid-Related Central Nervous System Side Effects: Case ReviewDocument6 pagesCorticosteroid-Related Central Nervous System Side Effects: Case Revieweva.mmNo ratings yet

- Schizophrenia ReportDocument6 pagesSchizophrenia ReportAnna Reeka AmadorNo ratings yet

- DualDiagnosisFactSheet, Co-Occurring Mental Illness and Substance Disorders, Kathleen Sciacca, July09Document4 pagesDualDiagnosisFactSheet, Co-Occurring Mental Illness and Substance Disorders, Kathleen Sciacca, July09Kathleen Sciacca, MA - Sciacca Comprehensive Service Dev. Dual Diagnosis; Motivational Interviewing100% (9)

- Psychiatric EmergencyDocument65 pagesPsychiatric EmergencyDivya ToppoNo ratings yet

- Life Writing and Schizophrenia Encounters at The E... - (3 A Striking Similarity With Our Theory' Freud and Bateson Read Memoi... )Document55 pagesLife Writing and Schizophrenia Encounters at The E... - (3 A Striking Similarity With Our Theory' Freud and Bateson Read Memoi... )cheshireangekNo ratings yet

- Functional Analysis and Treatment of Inappropriate Verbal BehaviorDocument3 pagesFunctional Analysis and Treatment of Inappropriate Verbal BehaviorMariaNo ratings yet

- Kleptomania and HomoeopathyDocument7 pagesKleptomania and HomoeopathyDr. Rajneesh Kumar Sharma MD HomNo ratings yet

- SIGN 131 - Management of Schizophrenia: A National Clinical Guideline March 2013Document71 pagesSIGN 131 - Management of Schizophrenia: A National Clinical Guideline March 2013Septia Widya PratamaNo ratings yet

- Klaus Conrad - History of PsychiatryDocument20 pagesKlaus Conrad - History of Psychiatryrocolmar100% (1)

- Autism Adults Misdiagnosis 2015Document16 pagesAutism Adults Misdiagnosis 2015Jennifer Soares de Souza de FreitasNo ratings yet

- Understanding Phobias and Anxiety DisordersDocument304 pagesUnderstanding Phobias and Anxiety DisordersASHISHNo ratings yet

- The Infantile Psychotic Self and Its Fates: Understanding and Treating Schizophrenics and Other Difficult PatientsDocument338 pagesThe Infantile Psychotic Self and Its Fates: Understanding and Treating Schizophrenics and Other Difficult PatientsKevin McInnes100% (1)

- STEP 2018 National Conference HighlightsDocument42 pagesSTEP 2018 National Conference HighlightsAnamika Sinha100% (1)

- Block 4 PDFDocument81 pagesBlock 4 PDFD S ThejeshNo ratings yet

- PsychiatryDocument23 pagesPsychiatryNaveenKumarNo ratings yet

- Emergency Psychiatry: Paper B Syllabic Content 7.4Document21 pagesEmergency Psychiatry: Paper B Syllabic Content 7.4CetVital100% (1)

- FORENSIC PSYCHIATRYDocument52 pagesFORENSIC PSYCHIATRYSiow Siow0% (1)

- Understanding Mental Health Problems 2016Document36 pagesUnderstanding Mental Health Problems 2016api-273164510No ratings yet

- Depresion en Adolescentes 2021 ReviewDocument5 pagesDepresion en Adolescentes 2021 ReviewDiana DuránNo ratings yet

- Life Review-Basic ConceptsDocument16 pagesLife Review-Basic ConceptsUdisha MerwalNo ratings yet

- Psicosis - 2021Document30 pagesPsicosis - 2021Felipe VergaraNo ratings yet

- Schizophrenia Care Plan RNDocument8 pagesSchizophrenia Care Plan RNlisa75% (4)

- Stopping and Switching Antipsychotic DrugsDocument6 pagesStopping and Switching Antipsychotic Drugsgilbert defretesNo ratings yet

- Understanding Schizophrenia: Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment ApproachesDocument57 pagesUnderstanding Schizophrenia: Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment ApproachesBorlongan PaulineNo ratings yet

- Couvade SyndromeDocument5 pagesCouvade SyndromejudssalangsangNo ratings yet