Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Gender Post Truth Populism and Higher Education Pedagogies

Uploaded by

AnanyaRoyPratiharOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Gender Post Truth Populism and Higher Education Pedagogies

Uploaded by

AnanyaRoyPratiharCopyright:

Available Formats

Teaching in Higher Education

ISSN: 1356-2517 (Print) 1470-1294 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cthe20

Gender, post-truth populism and higher education

pedagogies

Penny Jane Burke & Ronelle Carolissen

To cite this article: Penny Jane Burke & Ronelle Carolissen (2018) Gender, post-truth

populism and higher education pedagogies, Teaching in Higher Education, 23:5, 543-547, DOI:

10.1080/13562517.2018.1467160

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2018.1467160

Published online: 30 May 2018.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 1445

View related articles

View Crossmark data

Citing articles: 1 View citing articles

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cthe20

TEACHING IN HIGHER EDUCATION, 2018

VOL. 23, NO. 5, 543–547

https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2018.1467160

INTRODUCTION

Gender, post-truth populism and higher education

pedagogies

Penny Jane Burkea and Ronelle Carolissenb

a

Centre of Excellence for Equity in Higher Education, University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW, Australia;

b

Department of Educational Psychology, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa

Across varying global contexts, significant feminist contribution has been demonstrated

through gains in education, such as the high level of female participation in higher edu-

cation in many countries worldwide (Leathwood and Read 2009). Policies of access and

equity have contributed to growing diversity in higher education, and female students

have increasingly out numbered male students in many higher education contexts,

leading in some cases to processes of ‘gender mainstreaming’ (David 2016a). However,

the recent rise of populism in some regions of the world, together with the apparent res-

onance of ‘post-truth’ narratives, suggests an emerging formation of power concerned

with the undoing of hard-won gains in relation to gender and other intersecting forms

of inequality and difference. Increased incidences of the public articulation of misogynistic

and racist discourses (particularly via social media) and the apparent legitimation of these

practices in some high-profile instances (including the President of the United States of

America, Donald Trump), point to the ongoing and urgent need for feminist critique,

as well as wider social movements for women’s and LGBTQI rights and equalities. This

indeed has led to new social movements, such as #metoo against sexual violence and har-

assment, aiming to empower women to take a stand against institutionalized sexism. This

has been taken up by feminist scholars to explore

how the issues being raised by #metoo are manifest in the everyday practices of the contem-

porary university, what political and interpersonal tensions are brought forth by various

responses to the issues and how might we best respond to such tensions (Kenway et al. 2018).

Higher education has a key role to play in deconstructing the issues connected to contem-

porary social movements on emergent formations of power. This includes challenging the

anti-education, anti-expertise and anti-intellectual strands of post-truth populism, as well

as paying attention to the ways that gendered inequalities are potentially reproduced

through pedagogical spaces and formations of difference (Burke, Crozier, and Misiaszek

2017). This special issue pays close attention to the relationship between gender, power

and higher education pedagogies in the context of current political struggles and divisions

attached to competing claims to ‘truth’, ‘fake news’ and ‘post truth’ discourses.

It has been argued that processes of ‘gender mainstreaming’ have often been used ‘to

dismiss the necessity of feminist analysis’ (David 2016a). Gender mainstreaming tends

to ignore feminist analyses of context and difference with the ‘frequent use of gender-

neutral language in laws produc[ing] inattention to gendered power relations’ (David

CONTACT Penny Jane Burke pennyjane.burke@newcastle.edu.au

© 2018 Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group

544 P. J. BURKE AND R. CAROLISSEN

2016a, 65–66). The dis/connections between gender mainstreaming, the undermining of

feminism and the rise of post-truth populism requires in-depth analysis to understand

its implications for teaching, teachers and students in a range of different pedagogical con-

texts. Over the past decade, feminist scholars have brought attention to moral panics

attached to ‘masculinity in crisis’ discourses and the perceived ‘feminization’ of teaching

and learning in higher education (Leathwood and Read 2009; Burke 2015). Although fem-

inist scholars have provided detailed, extensive and close-up critique of masculinity in

crisis discourses, including in schooling contexts (Epstein et al. 1998), the simultaneous

mainstreaming of gender equity has arguably undermined feminism and weakened

anti-sexist policies and practices in higher education (David 2016a). For example,

although feminist research has exposed rape culture and ‘lad culture’ on campus

(Phipps and Young 2015), feminist scholars argue that policies remain woefully

inadequate, not only for students, but also for women and feminist academics (e.g.

David 2016b; Burke, David, and Moreau 2018).

Feminist critiques of the ‘feminization of higher education’ have also pointed to

ongoing binary divisions at play in universities that privilege the rational over the

emotional and undermine an ethics of care, potentially marginalizing those dispositions

associated with femininity (Burke 2015, 2017). Scholarship focused on intersectionality

has engaged with the ways gender intersects with a range of social and cultural differences

including class and race (see for example Mirza (2015) on ‘embodied intersectionality’).

Furthermore, despite a long-term commitment to widening participation in many

national contexts, research on teaching in higher education has minimally engaged ques-

tions of participation, to contribute to theoretical understanding of what constitutes ‘par-

ticipation’, particularly in relation to gendered power relations and intersecting social

inequalities (Burke, Crozier, and Misiaszek 2017). Although there have been attempts

to raise the profile of teaching in higher education across different national contexts

through moves towards ‘modernizing the university’ for the twenty-first century, many

of these considerations tend to reinforce neoliberal discourses of marketization, position-

ing teachers as service providers and students as educational consumers. Consequently,

the complex dynamics of pedagogical relations and experiences in relation to gendered

practices and subjectivities has been largely absent from research on teaching and learning

in higher education (see Burke, Crozier and Misiaszek 2017; Carolissen and Bozalek 2017).

Building on the body of work that has examined teaching in higher education in

relation to gender, diversity and difference, this special issue considers the complex

relationship between different and competing political forces at play, how these political

forces shape pedagogical practices in complex ways and how this re/produces relations

of gender and difference. This includes consideration of the pedagogical challenges

posed by the rise of populism in relation to gender equity in education; the potential

for feminist interventions in pedagogies and practices in post-truth, populist and author-

itarian contexts and critical consideration of which truths matter, whose truths matter and

who gets to decide what is truth. The special issue explores the relationships and the ten-

sions between feminisms and activism including the dis/connections between the tempor-

alities of the academy and of popular discourses, and how feminist interventions circulate,

for example through digital media. Considering the particular challenges for feminist edu-

cators of diverse backgrounds in educational institutions and in the context of the rise of

post-truth populism, the special issue addresses the affective dimensions of gendered and

TEACHING IN HIGHER EDUCATION 545

pedagogical formations in populist, post-truth contexts. In developing gender sensitive

frameworks, pedagogical strategies require attention to the relationship between theory

and practice, as well as the politics of knowledge and being a knower. This special issue

examines such questions in relation to (re)framing feminist epistemologies, which tend

to foreground constructivist perspectives, in the context of ongoing assaults on ‘truth’;

the ways media literacies offer pedagogical forms within and against a post-truth world

and the resultant research agendas for higher education scholars.

Emily Danvers begins examining such themes with a feminist rethinking of the onto-

logical construction of the ‘critical thinker’ illuminating the implications of the decontex-

tualized discourse of critical thinking in higher education. Her reflection helps shed light

on the ways that the desire for a particular notion of the critically thinking subject masks

power relations and the politics of difference from view. Drawing on empirical data,

Danvers shows that be(com)ing a critical thinking student is tied to gendered, embodied

performatives and subjectivities. This is a valuable reflection on a highly taken-for-granted

dimension of becoming a recognizable subject as university student, entangled with claims

to knowing and tied in with embodied and gendered ontologies.

Jessica Gagnon builds on this with a focus on the politics of misrecognition, with her

analytic focus on the experiences of daughters of single mothers in the UK. She argues

that histories of pathologization, tied to notions of (il)legitimacy – both within and

outside of university contexts – continue to play out in ways that mis/frame higher edu-

cation pedagogical relations and experiences. She points to the complicity of academic

research in producing negative constructions of single mother families through its

decontextualized analyses and normalization of the heterosexual nuclear family form.

Through her important analysis, Gagnon outlines significant spaces for feminist

approaches to re/frame the problem of who is seen as a legitimate student in (and

beyond) higher education.

However, feminist pedagogies do not provide a straightforward solution to the complex

power dynamics that circulate around knowledge production and ontological positioning.

Indeed, Judy Rohrer eloquently articulates that the ‘interdisciplines’ (e.g. Women’s,

Gender and Ethnic Studies) have been complicit in the rise of neoliberalism, making it

‘more difficult to respond effectively in the classroom to the current upsurge within the

U.S. in racism, xenophobia and post-truth populism’. Her important analysis examines

the entanglement of the ‘interdisciplines’ in the institutionalization of neoliberal corpor-

atization of the university over past decades, to then contextualize an approach she

names ‘its in the room’, which points to the often discomforting truth that whatever

the social justice issue being explored, it is almost always a presence in the classroom.

Through this, Rohrer helps to emphasize the urgent need for deep, critical and careful

reflexivity.

This theme of ‘it’s in the room’ is helpful when considering the power of the populist

discourse against ‘intellectual-elites’ of whom teachers in higher education might be cast.

Barbara Read examines two aligned but distinctive discourses: ‘Real World Anti-Elitist’

and the ‘Ivory Tower Rationalist’ to uncover their gendered, classed and raced underpin-

nings. She argues that these discourses can be linked to distinct epistemological and onto-

logical conceptions of the nature and purpose of academic knowledge, with significant

implications for conceptions of ‘truth’ and ultimately the nature and purpose of higher

education.

546 P. J. BURKE AND R. CAROLISSEN

A feminist and Freirean perspective brings light to processes of ‘curriculum activism’.

Natalie Jester argues that curriculum is a key site of contestation, and points to the value of

bringing in the voices of those historically marginalized from curriculum development.

Analysing two digital campaigns as curriculum activism, Why is my Curriculum White

(established by a group of UCL students in 2017) and Women Also Know Stuff (established

in 2016 by a group of academics in the US) Jester argues for a pedagogy of difference to

recognize the multidimensional, relational and complex nature of power relations in

higher education. This curriculum activism she locates as part of fourth wave feminism,

one that focuses on difference and intersectionality and that draws on digital technologies

as a pedagogical tool and a space for marginalized voices to be mobilized and articulated.

This is an article that captures the hope and excitement of new ways of being and doing

through deep engagement with feminism in all its trans/formations.

This includes post-humanist feminisms, which shed new light on teaching and the

affective and everyday experiences of uncomfortable pedagogical encounters. Sherilyn

Lennon, Tasha Riley and Sue Monk draw on their experiences of ‘uncomfortable teacherly

moments’ to foreground the affective over the rational and to reposition teaching within

an ethics of care, criticality and concern. Taking from Barad’s (2007) concept of onto-

ethico-epistemology, they show that what we know is inextricably tied to how we know.

Through an analysis of their everyday experiences as teachers, they examine how emotions

and the physical feelings they produce become entangled in the material and discursive

realities of pedagogical practices and identities and the intensive nature of teaching.

They reframe the ‘act of teaching as unstable, political, performative and entangled in

the words/worlds of others’ to ‘push back’ against the rationalism and reductivism of neo-

liberalized higher education.

Themes of care-fullness are also explored by Sara Motta and Anna Bennett in their

analysis of enabling education. They critique ‘care-lessness’ and posit three dimensions

of care-full pedagogical practice; care as recognition, care as dialogic relationality and

care as affective. Drawing on feminist Freirean pedagogical approaches they argue for

embodied praxis by foregrounding the centrality of caring work as part of the ethico-ped-

agogical commitments to care as a multidimensional pedagogical praxis within the field.

In the final Points of Departure contribution to this special issue, Jessica Ringrose pre-

sents a charged and powerful analysis of the potential of digital pedagogies to create a ped-

agogical platform for the visibility of feminist critiques against post-truth populism. She

locates this within her own pedagogical work and in the context of the presidential election

and Donald Trump’s ‘dramatic win’ in late 2016. Ringrose with her colleague Victoria

Showunmi draw on this moment as an opportunity to engage students in deep sociological

analysis, drawing on the tools of Black feminist and intersectional feminist theories. Ring-

rose shows the power of digital feminist activism and how it might be put to work in the

classroom.

It is perhaps also important to ask what the omissions in submissions and final pieces

are in terms of significant feminist scholarship that challenges post-truth populism. One

notable absence is the specific tradition of feminist decolonial work that draws on inter-

sectionalities (see for example the special edition of Journal of Feminist Scholarship).

This special issue – a collection of eight significant pieces of feminist scholarship and

intervention, at a moment of and against post-truth populism – contributes to the peda-

gogical spaces of Teaching in Higher Education. It is our hope that these eight pieces spark

TEACHING IN HIGHER EDUCATION 547

you the reader’s pedagogical imagination to create spaces of critique and hope, to recog-

nize what and who is in the room, and to contribute to transformational practices through,

within and beyond higher education.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

Barad, J. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter

and Meaning. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Burke, P. J. 2015. “Re/Imagining Higher Education Pedagogies: Gender, Emotion and Difference.”

Teaching in Higher Education 20 (4): 388–401.

Burke, P. J. 2017. “Difference in Higher Education Pedagogies: Gender, Emotion and Shame.”

Gender and Education 29 (4): 430–444.

Burke, P. J., G. Crozier, and L. Misiaszek. 2017. Changing Pedagogical Spaces in Higher Education.

Diversity, Inequalities and Misrecognition. London: Routledge.

Burke, P. J., M. David, and M. P. Moreau. 2018. “Policy Implications for Equity, Gender and

Widening Participation in Higher Education.” In The Oxford Handbook of Comparative

Higher Education Systems and University Management, edited by G. Redding, S. Crump, and

T. Drew. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Carolissen, R., and V. Bozalek. 2017. “Addressing Dualisms in Student Perceptions of a Historically

Black and White University in South Africa.” Race Ethnicity and Education 20 (3): 344–357.

David, M. E. 2016a. A Feminist Manifesto for Education. Cambridge: Polity Press.

David, M. E. 2016b. Reclaiming Feminism: Challenging Everyday Misogyny. Bristol: Policy Press.

Epstein, D., J. Elwood, V. Hey, and J. Maw. 1998. Failing Boys? Issues in Gender and Achievement.

Buckinghamshire: Open University Press.

Kenway, J., R. Barron, D. Epstein, and M. Wolfe. 2018. “#Metoo in the Contemporary University:

Probing Possibilities Through Everyday Scenarios.” Abstract for workshop to be presented at

the gender and education association 2018 conference, University of Newcastle, Australia,

December 9–12 2018.

Leathwood, C., and B. Read. 2009. Gender and the Changing Face of Higher Education: A Feminized

Future? Berkshire: Open University Press.

Mirza, H. 2015. “Decolonizing Higher Education: Black Feminism and the Intersectionality of Race

and Gender.” Journal of Feminist Scholarship 7/8: 1–12.

Phipps, A., and I. Young. 2015. “‘Lad Culture’ in Higher Education: Agency in the Sexualization

Debates.” Sexualities 18 (4): 459–479.

You might also like

- Diversity Assessment 1Document10 pagesDiversity Assessment 1api-368798504No ratings yet

- Intersectional Pedagogy - Gal Harmat - Chapter2Document28 pagesIntersectional Pedagogy - Gal Harmat - Chapter2Cloè Saint-NomNo ratings yet

- 4j-1d-Ways of Learning About The Social World 1 1Document7 pages4j-1d-Ways of Learning About The Social World 1 1marianabejan27No ratings yet

- Gender Equality in Higher Education and ResearchDocument8 pagesGender Equality in Higher Education and ResearchKyle MonteroNo ratings yet

- MARVELL & CHILD - 2022 - I Have Some Trauma Responses But It's Not My IdentityDocument23 pagesMARVELL & CHILD - 2022 - I Have Some Trauma Responses But It's Not My IdentityLeonardo MonteiroNo ratings yet

- Diversity and Excellence in Higher Education: Is There A Con Ict?Document19 pagesDiversity and Excellence in Higher Education: Is There A Con Ict?Renan SantiagoNo ratings yet

- Gender and Environmental Education in The Time of MeTooDocument4 pagesGender and Environmental Education in The Time of MeTooOnur YılmazNo ratings yet

- Does Class Still Matter Conversations About Power, Privilege and Persistent Inequalities in Higher EducationDocument13 pagesDoes Class Still Matter Conversations About Power, Privilege and Persistent Inequalities in Higher EducationKyle MonteroNo ratings yet

- HistoryDocument10 pagesHistoryapi-249684663No ratings yet

- EquityDocument83 pagesEquityMrunalNo ratings yet

- Feminism, Power and Pedagogy: Editors'Document6 pagesFeminism, Power and Pedagogy: Editors'Laura Ordóñez AlcaláNo ratings yet

- Lynch InequalityHigherEducation 1998Document35 pagesLynch InequalityHigherEducation 1998Minaal AhmedNo ratings yet

- The Next Generation of Diversity and Intergroup Relations ResearchDocument16 pagesThe Next Generation of Diversity and Intergroup Relations ResearchSarmad SultanNo ratings yet

- Literacy Education in The Post-Truth Era The PedagDocument18 pagesLiteracy Education in The Post-Truth Era The PedagJohnmar FortesNo ratings yet

- Conditionally Accepted: Navigating Higher Education from the MarginsFrom EverandConditionally Accepted: Navigating Higher Education from the MarginsEric Joy DeniseNo ratings yet

- Multiculturalism Inclusion Policy and LearningDocument5 pagesMulticulturalism Inclusion Policy and Learningapi-528785412No ratings yet

- Future Directions and Evolving ParadigmsDocument1 pageFuture Directions and Evolving Paradigmsmarykamande73No ratings yet

- p1 Final PublicDocument39 pagesp1 Final PublicIvanovici DanielaNo ratings yet

- 4 C YatesDocument19 pages4 C YatesJames McDonaldNo ratings yet

- Essay 1 Critically AnalyseDocument8 pagesEssay 1 Critically Analyseapi-332423029No ratings yet

- Theories of Gender DevelopmentDocument6 pagesTheories of Gender DevelopmentNeil Kio GipayaNo ratings yet

- Critical Pedagogy "Under The Radar" and "Off The Grid": Tricia M. Kress, Donna Degennaro, & Patricia PaughDocument9 pagesCritical Pedagogy "Under The Radar" and "Off The Grid": Tricia M. Kress, Donna Degennaro, & Patricia PaughAbdelalim TahaNo ratings yet

- From One To Three - China's Motherhood Dilemma and Obstacle To Gender EqualityDocument15 pagesFrom One To Three - China's Motherhood Dilemma and Obstacle To Gender Equalityyujialing2011No ratings yet

- Researching As A Critical Secretary A Strategy and Praxis For Critical EthnographyDocument17 pagesResearching As A Critical Secretary A Strategy and Praxis For Critical EthnographyFabiana AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- Emery TSOC 5000 Three Perspectives Essay 15SEP2021Document11 pagesEmery TSOC 5000 Three Perspectives Essay 15SEP2021emeryNo ratings yet

- Intersectionality in EducationDocument11 pagesIntersectionality in EducationHoàng MinhNo ratings yet

- IntersectionalityDocument25 pagesIntersectionalityapi-540296556No ratings yet

- Creating Queer Space in Schools As A Matter of Social JusticeDocument15 pagesCreating Queer Space in Schools As A Matter of Social JusticeemeryNo ratings yet

- LivroVIICIEC2020 - Ingls 74 82Document9 pagesLivroVIICIEC2020 - Ingls 74 82Giancarlo Gevu dos SantosNo ratings yet

- NAMEDocument11 pagesNAMERose Jane AdobasNo ratings yet

- Assignment 2Document8 pagesAssignment 2朱珠No ratings yet

- Making Excellence Inclusive:: Higher Education's LGBTQ ContextsDocument24 pagesMaking Excellence Inclusive:: Higher Education's LGBTQ ContextsinquepennNo ratings yet

- 2016 Book AGirlSEducationDocument228 pages2016 Book AGirlSEducationBilly James St JohnNo ratings yet

- DSJL EssayDocument6 pagesDSJL Essayapi-357321063No ratings yet

- Mathematics Education and Society: An OverviewDocument11 pagesMathematics Education and Society: An OverviewSantiago Gomez ObandoNo ratings yet

- Keddie Amanda - Engaging Boys in Gender Activism Issues of Discomfort and EmotionDocument24 pagesKeddie Amanda - Engaging Boys in Gender Activism Issues of Discomfort and Emotioncagedo5892No ratings yet

- Towards A Framework For A Critical Statistical Literacy in High School MathematicsDocument8 pagesTowards A Framework For A Critical Statistical Literacy in High School MathematicsManuel Alejandro Fernandez CifuentesNo ratings yet

- Race, Ethnicity and Gendered Educational IntersectionsDocument8 pagesRace, Ethnicity and Gendered Educational IntersectionsshyamoliesinghNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Ni KelvinDocument39 pagesChapter 2 Ni KelvinJessie Marie PorcallaNo ratings yet

- FinalDocument3 pagesFinalNow OnwooNo ratings yet

- Not in Their Name: Re-Interpreting Discourses of STEM Learning Through The Subjective Experiences of Minoritized GirlsDocument25 pagesNot in Their Name: Re-Interpreting Discourses of STEM Learning Through The Subjective Experiences of Minoritized GirlsAnonymous Fwe1mgZNo ratings yet

- Deliberation & the Work of Higher Education: Innovations for the Classroom, the Campus, and the CommunityFrom EverandDeliberation & the Work of Higher Education: Innovations for the Classroom, the Campus, and the CommunityRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Thesis Statement For Womens EqualityDocument4 pagesThesis Statement For Womens Equalityjensantiagosyracuse100% (2)

- Capstone Annotated Bibliography 1Document6 pagesCapstone Annotated Bibliography 1api-610048393No ratings yet

- Gender EducationDocument8 pagesGender EducationMiguel CompletoNo ratings yet

- Approaches To Media Literacy EducationDocument4 pagesApproaches To Media Literacy EducationNilo LoloNo ratings yet

- Public Engagement for Public Education: Joining Forces to Revitalize Democracy and Equalize SchoolsFrom EverandPublic Engagement for Public Education: Joining Forces to Revitalize Democracy and Equalize SchoolsNo ratings yet

- Transphobic Violence in Educational CentersDocument15 pagesTransphobic Violence in Educational CentersamayalibelulaNo ratings yet

- Critical Pedagogy and Social WorkDocument8 pagesCritical Pedagogy and Social WorkdonnakishotNo ratings yet

- Student AttitudeDocument4 pagesStudent AttitudeRamela BauliteNo ratings yet

- Trans Children1Document18 pagesTrans Children1Nesrin AydınNo ratings yet

- Chapters 1-3Document63 pagesChapters 1-3Bagwis MayaNo ratings yet

- Perales Sartorello 2023 Inclusion Critical and Decolonial PerspectivesDocument20 pagesPerales Sartorello 2023 Inclusion Critical and Decolonial PerspectivesAileen Cortés BarreraNo ratings yet

- PHD Thesis On Gender MainstreamingDocument4 pagesPHD Thesis On Gender Mainstreamingbk4pfxb7100% (2)

- Textbook RegimesDocument62 pagesTextbook RegimessachitNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 FinalDocument9 pagesChapter 1 FinalkenntorrespogiNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Topics Gender EducationDocument4 pagesDissertation Topics Gender EducationThesisPapersForSaleSingapore100% (1)

- "But What Can I Do?" Fifteen Things Education Students Can Do To Transform Themselves In/Through/With Education by Paul R. CarrDocument17 pages"But What Can I Do?" Fifteen Things Education Students Can Do To Transform Themselves In/Through/With Education by Paul R. CarrAbdelalim TahaNo ratings yet

- Gender in the Political Science ClassroomFrom EverandGender in the Political Science ClassroomEkaterina M. LevintovaNo ratings yet

- Case Based Group DiscussionDocument1 pageCase Based Group DiscussionAnanyaRoyPratiharNo ratings yet

- Early Modern: Humanism and The English Renaissance and The Print RevolutionDocument9 pagesEarly Modern: Humanism and The English Renaissance and The Print RevolutionAnanyaRoyPratiharNo ratings yet

- Interview Skills: Communication Skills: Lecture No. 27Document8 pagesInterview Skills: Communication Skills: Lecture No. 27AnanyaRoyPratiharNo ratings yet

- George Bernard ShawDocument1 pageGeorge Bernard ShawAnanyaRoyPratiharNo ratings yet

- Creative Thinking - Session 6Document2 pagesCreative Thinking - Session 6AnanyaRoyPratiharNo ratings yet

- Science and Human LifeDocument2 pagesScience and Human LifeAnanyaRoyPratiharNo ratings yet

- Me Too Content Analysis of Uk PaperDocument21 pagesMe Too Content Analysis of Uk PaperAnanyaRoyPratiharNo ratings yet

- On The Rule of The RoadDocument4 pagesOn The Rule of The RoadAnanyaRoyPratihar100% (1)

- Subhajit PHD Thesis PDFDocument370 pagesSubhajit PHD Thesis PDFAnanyaRoyPratiharNo ratings yet

- Interview Skills: Communication Skills: Lecture No. 25Document12 pagesInterview Skills: Communication Skills: Lecture No. 25AnanyaRoyPratiharNo ratings yet

- 2 NDDocument8 pages2 NDAnanyaRoyPratiharNo ratings yet

- Identifying Past, Present or Future Verb Tenses WorksheetDocument1 pageIdentifying Past, Present or Future Verb Tenses WorksheetAnanyaRoyPratiharNo ratings yet

- Nationalism in The WestDocument7 pagesNationalism in The WestAnanyaRoyPratiharNo ratings yet

- The Child in Postcolonial Fiction: A Cross-Cultural StudyDocument1 pageThe Child in Postcolonial Fiction: A Cross-Cultural StudyAnanyaRoyPratiharNo ratings yet

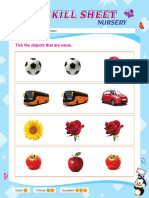

- Nursery 2 PDFDocument15 pagesNursery 2 PDFAnanyaRoyPratiharNo ratings yet

- 08 - Chapter 2Document64 pages08 - Chapter 2AnanyaRoyPratiharNo ratings yet

- 10 - Chapter 4Document65 pages10 - Chapter 4AnanyaRoyPratiharNo ratings yet

- 11 - Chapter 5Document19 pages11 - Chapter 5AnanyaRoyPratiharNo ratings yet

- CASE 1: The Promising Chemist Who Buried His ResultsDocument1 pageCASE 1: The Promising Chemist Who Buried His ResultsAnanyaRoyPratihar67% (3)

- 09 - Chapter 3Document62 pages09 - Chapter 3AnanyaRoyPratiharNo ratings yet

- Folktale in Modern Indian LiteratureDocument55 pagesFolktale in Modern Indian LiteratureAnanyaRoyPratiharNo ratings yet

- The Awakening IndiaDocument14 pagesThe Awakening IndiaAnanyaRoyPratiharNo ratings yet

- Literary Art in An Age of Formula Fiction and Mass Consumption: Double Coding in Arthur Conan Doyle's "The Blue Carbuncle"Document16 pagesLiterary Art in An Age of Formula Fiction and Mass Consumption: Double Coding in Arthur Conan Doyle's "The Blue Carbuncle"AnanyaRoyPratiharNo ratings yet

- Chetan Bhagat 2Document7 pagesChetan Bhagat 2AnanyaRoyPratiharNo ratings yet

- MISCOMMUNICATIONDocument7 pagesMISCOMMUNICATIONAnanyaRoyPratiharNo ratings yet

- Eclipse Phase - Character QuestionnaireDocument13 pagesEclipse Phase - Character QuestionnaireFlorian RussierNo ratings yet

- Gender HierarchyDocument5 pagesGender HierarchyNorielyn RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Waala LangDocument37 pagesWaala LangLarie San T. MalonzoNo ratings yet

- Thompson Bennett 2015Document20 pagesThompson Bennett 2015Felipe Corrêa MessiasNo ratings yet

- Chapter One: Critical Discourse Analysis by Diako Hamzehzadeh AfkhamDocument73 pagesChapter One: Critical Discourse Analysis by Diako Hamzehzadeh AfkhamFarhana Peter100% (2)

- First Wedding Night - ImportanceDocument8 pagesFirst Wedding Night - Importanceapi-3800338100% (1)

- Laws, Policies, and Programs For Philippine WomenDocument21 pagesLaws, Policies, and Programs For Philippine WomenHannah Joy MariNo ratings yet

- Gender and Power RelationsDocument15 pagesGender and Power RelationsputrilailiNo ratings yet

- Finals - ED01Document36 pagesFinals - ED01Personal AdminNo ratings yet

- Philo Q1 M8Document13 pagesPhilo Q1 M8Pril Gueta100% (3)

- Table of Specification in DissDocument16 pagesTable of Specification in DissVenus Samillano EguicoNo ratings yet

- Louella Lofranco The Spiritual Ramifications of The SOGIE Bill Part 2Document20 pagesLouella Lofranco The Spiritual Ramifications of The SOGIE Bill Part 2Lynn BeckNo ratings yet

- Students' Attitudes, Motivation, AnxietyDocument25 pagesStudents' Attitudes, Motivation, AnxietyileanasinzianaNo ratings yet

- African Women Under Pre-ColonialDocument9 pagesAfrican Women Under Pre-ColonialAnonymous UGZskpisNo ratings yet

- Federal Public Service Commission Revised Scheme of Css Competitive ExaminationDocument38 pagesFederal Public Service Commission Revised Scheme of Css Competitive ExaminationPrabesh PrabeshNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Health Studies Sample Chapter1Document22 pagesContemporary Health Studies Sample Chapter1Rodolfo RuizNo ratings yet

- Panchayat RajDocument5 pagesPanchayat RajDaniel Sundar RajNo ratings yet

- Masculinity, Marriage and Migration PDFDocument21 pagesMasculinity, Marriage and Migration PDFGautamiNo ratings yet

- Images of Circumcision Complications Adult Circumcision Images Complications of Circumcision - Your Whole BabyDocument1 pageImages of Circumcision Complications Adult Circumcision Images Complications of Circumcision - Your Whole BabyPhoenixxx BeyNo ratings yet

- Parreño, 2023Document22 pagesParreño, 2023Angela Mae SuyomNo ratings yet

- DissertationDocument67 pagesDissertationshubhsarNo ratings yet

- Tangible Territory Final Version Thesis (Unlocked by WWW - Freemypdf.com)Document168 pagesTangible Territory Final Version Thesis (Unlocked by WWW - Freemypdf.com)orlati.federica2007No ratings yet

- Toft, Franklin, LangleyDocument14 pagesToft, Franklin, LangleyalanNo ratings yet

- Sub GuideDocument96 pagesSub GuidereditisNo ratings yet

- Women's RightsDocument2 pagesWomen's RightsRuba Tarshne :)No ratings yet

- Oguny Chapter OneDocument38 pagesOguny Chapter OneSheri DeanNo ratings yet

- Transgender HealthcareDocument3 pagesTransgender HealthcareAdamNo ratings yet

- Crime in IndiaDocument19 pagesCrime in IndiaAkshat AgarwalNo ratings yet

- 2021 Book ParentingAndCoupleRelationshipDocument324 pages2021 Book ParentingAndCoupleRelationshipAbigailNo ratings yet

- Setegn ArasawDocument151 pagesSetegn ArasawJosh TingNo ratings yet