Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The University of Chicago Press

Uploaded by

pishoi gergesOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The University of Chicago Press

Uploaded by

pishoi gergesCopyright:

Available Formats

Holy Scripture: Canon, Authority, Criticism by James Barr

Review by: Robert G. Boling

The Journal of Religion, Vol. 66, No. 1 (Jan., 1986), pp. 69-70

Published by: The University of Chicago Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1562396 .

Accessed: 17/06/2014 20:20

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The

Journal of Religion.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.90 on Tue, 17 Jun 2014 20:20:43 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Book Reviews

Hellenistic literature. While he rightly argues for the continuity between the

symbolic meanings of biblical and rabbinic Zion, he does not take sufficient

account of the discontinuities shaped by the very different sociopolitical, cul-

tural, and demographic realities. (On this point, and for another treatment of

the Sinai and Zion symbolism, see my book, not cited by Levenson: TheShape

of SacredSpace[Chico, Calif.: Scholars Press, 1981], pp. 25-79.)

But Levenson fulfills the promise of comparative study in his sensitive

analysis of the distinctive emphases of the Zion symbolism. He demonstrates,

for instance, that whereas the Sinai traditions focus on audition as the medium

of revelation, the Jerusalem temple tradition emphasizes vision. Again, he

argues that Zion functions especially as a moral center. In contrast to those

scholars who identify the priesthood and temple as corrupt, Levenson stresses

the priesthood's self-critique manifested in texts such as Psalm 24.

In his concluding part, Levenson challenges those critics who claim that the

Sinai and Zion traditions represent radically different visions of God's rela-

tionship to Israel. Levenson's eye toward Judaism, in which Torah and

Messiah complement rather than oppose each other, leads him to argue for the

coexistence - indeed, the mutual fructification- of the two theological

traditions in ancient Israel. Together they represent two sides of the same

coin, the coin of Judaism minted in the Jewish Bible. In this eminently read-

able work of biblical scholarship of the highest order, Levenson enables that

Bible's many voices to speak for themselves and yet communicate a coherent

religious vision.

ROBERT L. COHN, Northwestern University.

BARR, JAMES. Holy Scripture: Canon, Authority, Criticism. Philadelphia: West-

minster Press, 1983. vi+ 182 pp. $9.95.

In these James Sprunt Lectures of 1982, James Barr evaluates canonical

criticism, as represented chiefly by B. S. Childs in Introductionto the Old

Testament as Scripture(Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1979). James Sanders, in

Torahand Canon(Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1972), receives proportionately

smaller and somewhat less negative space.

Three constructive chapters lay the groundwork of canonical criticism,

while opposition waits in the wings. Chapter 1, "Before Scripture and after

Scripture,"is a well-reasoned statement of matters that ought to be obvious:

"Faithand religion, within the Bible, were not faith and religion defined and

determined by a Bible" (p. 1). When, in later centuries, completed Scripture

became the starting point for interpretation- a point outside the situation of

the biblical people - the result was a deep anachronism in the traditionaldoc-

trine. The subsequent Renaissance and Enlightenment made the history of

religion indispensable to biblical theology.

Chapter 2 addressesbiblical authority and biblical criticism in the conflict of

church traditions: Catholic versus Protestant (Judaism regularly comes in for

comparison, eastern Christianity is ignored). Barr unmasks the Jekyll-and-

Hyde behavior of tradition in the opposing camps and applauds beneficent

ecumenical effects of twentieth-century biblical criticism in this regard. In

Barr's brief history of tradition both camps score points. "It no longer makes

sense to speak of the authority of the Bible as if it meant the authority of the

69

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.90 on Tue, 17 Jun 2014 20:20:43 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Journal of Religion

written documents, quite apart from the persons and lives that lie behind

them" (p. 47).

Chapter 3, "The Concept of Canon and Its Modern Adventures," deals

mostly with the concept. The bottom line is canon as a list, a rather late Chris-

tian one, of scriptural books. "Canon" is only applicable in some analogical

way to the formation of Old Testament books as recognized Scripture forJews

and earliest Christians. The triumph of Torah was "not really a process of

canonization at all" (p. 51). Nor are "canon" and "Scripture" synonymous for

the New Testament, where "the existence of holy scripture is beyond doubt,

but we do not know exactly what it comprised, or whether it was thought to

have precise boundaries at all" (p. 61).

With chapter 4, Barr steps into the ring, assuming the readers' familiarity

with canonical criticism. Barr faults the use of "canon" and "canonical form"

for three different things that function in three different ways. Canon 1 is

standard usage for the list of books comprising holy scripture. Canon 2, the

final form, so-called canonical form, is something else, making it possible to

attribute "intentionality" to the canon. With Scripture virtually hypostatized,

canonical criticism completely rules out any attention to earlier stages that

may, Barr argues, have something more or better to contribute to interpreta-

tion. Canon 3 is a governing perspective required of the interpreter, for which

"holistic" is a favorite label. Not a canon in any ordinary sense, that is rather

"the principle of attraction, value, and satisfaction that makes everything

about canons and canonicity beautiful" (p. 76). Barr's point is that the

influence of structuralism ought to be openly acknowledged as another mem-

ber in the family of criticism, subject to the same give and take of family life.

"Theology begins when we pass by the sense of religious satisfaction and begin

to pose the question of truth" (p. 104).

With chapter 5, Barr returns to the constructive vein: "For critical scholar-

ship the standard and criterion for judging the validity of exegesis lies no

longer in church doctrine, but in research" (p. 108).

Two appendixes, a bibliography, and two indexes augment the usefulness

of this book, which helps to clear the air of inflated claims, so that enduring

contributions of canonical criticism can be welcomed.

ROBERT G. BOLING, McCormick TheologicalSeminary.

CANCIK, HUBERT, ed. Markus-Philologie: Historische, literargeschichtlicheund

stilistische Untersuchungenzum zweiten Evangelium. Tiibingen: J. C. B. Mohr

(Paul Siebeck), 1984. v+227 pp. DM 148.

The eight studies in this collection seek to describe the historical and literary

character of the Gospel of Mark. Questions of date, place of origin,

authorship, and language are addressed in the first part of the book (Martin

Hengel, "Entstehungszeit und Situation des Markusevangeliums"; Giinther

Zuntz, "Wann wurde das Evangelium Marci geschrieben?"; Hans Peter

Riiger, "Die lexikalischen Aramaismen im Markusevangelium"), while

problems of genre, composition, and rhetoric occupy the second part (Hubert

70

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.90 on Tue, 17 Jun 2014 20:20:43 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Demons and Spirits in Biblical Theology: Reading the Biblical Text in Its Cultural and Literary ContextFrom EverandDemons and Spirits in Biblical Theology: Reading the Biblical Text in Its Cultural and Literary ContextRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Conversion in Luke-Acts: Divine Action, Human Cognition, and the People of GodFrom EverandConversion in Luke-Acts: Divine Action, Human Cognition, and the People of GodNo ratings yet

- Society, the Sacred and Scripture in Ancient Judaism: A Sociology of KnowledgeFrom EverandSociety, the Sacred and Scripture in Ancient Judaism: A Sociology of KnowledgeNo ratings yet

- Death and Resurrection: The Shape and Function of a Literary Motif in the Book of ActsFrom EverandDeath and Resurrection: The Shape and Function of a Literary Motif in the Book of ActsNo ratings yet

- Sinai & Zion: An Entry into the Jewish BibleFrom EverandSinai & Zion: An Entry into the Jewish BibleRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (10)

- Biblical Prophecy: Perspectives for Christian Theology, Discipleship, and MinistryFrom EverandBiblical Prophecy: Perspectives for Christian Theology, Discipleship, and MinistryNo ratings yet

- Interpreting the Old Testament: A Guide for ExegesisFrom EverandInterpreting the Old Testament: A Guide for ExegesisRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Ancient Jewish and Christian Scriptures: New Developments in Canon ControversyFrom EverandAncient Jewish and Christian Scriptures: New Developments in Canon ControversyNo ratings yet

- Bible and Ethics in the Christian Life: A New ConversationFrom EverandBible and Ethics in the Christian Life: A New ConversationRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- The Authors of the Deuteronomistic History: Locating a Tradition in Ancient IsraelFrom EverandThe Authors of the Deuteronomistic History: Locating a Tradition in Ancient IsraelNo ratings yet

- Now and Then: Biblical Conversations, New Testament Contexts, Formative MemoriesFrom EverandNow and Then: Biblical Conversations, New Testament Contexts, Formative MemoriesNo ratings yet

- Symbol, Service, and Song: The Levites of 1 Chronicles 10-29 in Rhetorical, Historical, and Theological PerspectivesFrom EverandSymbol, Service, and Song: The Levites of 1 Chronicles 10-29 in Rhetorical, Historical, and Theological PerspectivesNo ratings yet

- Seeing the Lord's Glory: Kyriocentric Visions and the Dilemma of Early ChristologyFrom EverandSeeing the Lord's Glory: Kyriocentric Visions and the Dilemma of Early ChristologyNo ratings yet

- God's Word in Human Words: An Evangelical Appropriation of Critical Biblical ScholarshipFrom EverandGod's Word in Human Words: An Evangelical Appropriation of Critical Biblical ScholarshipRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (9)

- Sola Scriptura: Scripture's Final Authority in the Modern WorldFrom EverandSola Scriptura: Scripture's Final Authority in the Modern WorldNo ratings yet

- Canon Revisited: Establishing the Origins and Authority of the New Testament BooksFrom EverandCanon Revisited: Establishing the Origins and Authority of the New Testament BooksRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (24)

- Money and Possessions: Interpretation: Resources for the Use of Scripture in the ChurchFrom EverandMoney and Possessions: Interpretation: Resources for the Use of Scripture in the ChurchRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Genesis 1–11: Its Literary Coherence and Theological MessageFrom EverandGenesis 1–11: Its Literary Coherence and Theological MessageNo ratings yet

- The Erosion of Inerrancy in Evangelicalism: Responding to New Challenges to Biblical AuthorityFrom EverandThe Erosion of Inerrancy in Evangelicalism: Responding to New Challenges to Biblical AuthorityRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- From Text to Performance: Narrative and Performance Criticisms in Dialogue and DebateFrom EverandFrom Text to Performance: Narrative and Performance Criticisms in Dialogue and DebateNo ratings yet

- The Jewish Apocalyptic Tradition and the Shaping of New Testament ThoughtFrom EverandThe Jewish Apocalyptic Tradition and the Shaping of New Testament ThoughtBenjamin E. ReynoldsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Theology of the Prophetic Books: The Death and Resurrection of IsraelFrom EverandTheology of the Prophetic Books: The Death and Resurrection of IsraelNo ratings yet

- Scripture, Cultures, and Criticism: Interpretive Steps and Critical Issues Raised by Robert JewettFrom EverandScripture, Cultures, and Criticism: Interpretive Steps and Critical Issues Raised by Robert JewettNo ratings yet

- The Book of Exodus (1974): A Critical, Theological CommentaryFrom EverandThe Book of Exodus (1974): A Critical, Theological CommentaryRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (17)

- Scripture as Real Presence: Sacramental Exegesis in the Early ChurchFrom EverandScripture as Real Presence: Sacramental Exegesis in the Early ChurchRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Being Human in God's World: An Old Testament Theology of HumanityFrom EverandBeing Human in God's World: An Old Testament Theology of HumanityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- Studies on the Origin of Divine and Resurrection ChristologyFrom EverandStudies on the Origin of Divine and Resurrection ChristologyNo ratings yet

- Dempster - Torah and TempleDocument34 pagesDempster - Torah and TempleMichael Morales100% (1)

- Scripture First: Biblical Interpretation that Fosters Christian UnityFrom EverandScripture First: Biblical Interpretation that Fosters Christian UnityNo ratings yet

- Ancient Word, Changing Worlds: The Doctrine of Scripture in a Modern AgeFrom EverandAncient Word, Changing Worlds: The Doctrine of Scripture in a Modern AgeRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (10)

- God's Israel and the Israel of God: Paul and SupersessionismFrom EverandGod's Israel and the Israel of God: Paul and SupersessionismNo ratings yet

- Apocalyptic Thought in Early Christianity (Holy Cross Studies in Patristic Theology and History)From EverandApocalyptic Thought in Early Christianity (Holy Cross Studies in Patristic Theology and History)No ratings yet

- Canonical Theology: The Biblical Canon, Sola Scriptura, and Theological MethodFrom EverandCanonical Theology: The Biblical Canon, Sola Scriptura, and Theological MethodNo ratings yet

- Reading Romans after Supersessionism: The Continuation of Jewish Covenantal IdentityFrom EverandReading Romans after Supersessionism: The Continuation of Jewish Covenantal IdentityNo ratings yet

- (Wam) Sparks of The Logos, Essays in Rabbinic Hermeneutics - Daniel BoyarinDocument317 pages(Wam) Sparks of The Logos, Essays in Rabbinic Hermeneutics - Daniel BoyarinJeanFobeNo ratings yet

- Boyarin Daniel Sparks of The LogosDocument317 pagesBoyarin Daniel Sparks of The LogosSuleiman Hodali100% (3)

- Christ and the New Creation: A Canonical Approach to the Theology of the New TestamentFrom EverandChrist and the New Creation: A Canonical Approach to the Theology of the New TestamentRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- The Dance Between God and Humanity: Reading the Bible Today as the People of GodFrom EverandThe Dance Between God and Humanity: Reading the Bible Today as the People of GodNo ratings yet

- Theological Hermeneutics and the Book of Numbers as Christian ScriptureFrom EverandTheological Hermeneutics and the Book of Numbers as Christian ScriptureNo ratings yet

- New Meanings for Ancient Texts: Recent Approaches to Biblical Criticisms and Their ApplicationsFrom EverandNew Meanings for Ancient Texts: Recent Approaches to Biblical Criticisms and Their ApplicationsNo ratings yet

- How Jews and Christians Interpret Their Sacred Texts: A Study in TransvaluationFrom EverandHow Jews and Christians Interpret Their Sacred Texts: A Study in TransvaluationNo ratings yet

- Eschatological Relationships and Jesus in Ben F. Meyer, N. T. Wright, and Progressive DispensationalismFrom EverandEschatological Relationships and Jesus in Ben F. Meyer, N. T. Wright, and Progressive DispensationalismNo ratings yet

- Justice for the Poor?: Social Justice in the Old Testament in Concept and PracticeFrom EverandJustice for the Poor?: Social Justice in the Old Testament in Concept and PracticeNo ratings yet

- Beyond Judaisms - Metatron and The Divine Polymorphy of Ancient JudaismDocument43 pagesBeyond Judaisms - Metatron and The Divine Polymorphy of Ancient Judaismיונתן בן הראשNo ratings yet

- The Society of Biblical LiteratureDocument26 pagesThe Society of Biblical LiteraturePavlMikaNo ratings yet

- Literal Sense Sandra M SchneiderspdfDocument19 pagesLiteral Sense Sandra M Schneiderspdf321876100% (1)

- Brevard Childs: ' Canonical TheologyDocument6 pagesBrevard Childs: ' Canonical TheologyDavid Muthukumar S100% (1)

- The Sermon On The MountDocument47 pagesThe Sermon On The MountLearn Kriya100% (1)

- The Formation of The Pentateuch BridgingDocument22 pagesThe Formation of The Pentateuch Bridgingpishoi gergesNo ratings yet

- Genesis 22 What Question Should We Ask TDocument12 pagesGenesis 22 What Question Should We Ask Tpishoi gergesNo ratings yet

- The Historical-Critical Method and The Holy FatherDocument24 pagesThe Historical-Critical Method and The Holy Fatherpishoi gergesNo ratings yet

- Via Pontifical Biblical InstituteDocument1 pageVia Pontifical Biblical Institutepishoi gergesNo ratings yet

- The Limits of Interpretation The PentateDocument12 pagesThe Limits of Interpretation The Pentatepishoi gergesNo ratings yet

- 10 1002@sici1096-865219960852@4275@@aid-Ajh63 0 Co2-P PDFDocument6 pages10 1002@sici1096-865219960852@4275@@aid-Ajh63 0 Co2-P PDFpishoi gergesNo ratings yet

- Results of A Genome-Wide Genetic Screen For Panic Disorder: © 1998 Wiley-Liss, IncDocument9 pagesResults of A Genome-Wide Genetic Screen For Panic Disorder: © 1998 Wiley-Liss, Incpishoi gergesNo ratings yet

- Via Pontifical Biblical InstituteDocument3 pagesVia Pontifical Biblical Institutepishoi gergesNo ratings yet

- Pesticide Science Volume 50 Issue 3 1997 (Doi 10.1002 - KineDocument8 pagesPesticide Science Volume 50 Issue 3 1997 (Doi 10.1002 - Kinepishoi gergesNo ratings yet

- Steegmann 1996Document6 pagesSteegmann 1996pishoi gergesNo ratings yet

- Hiding From God's Word: ReallyDocument3 pagesHiding From God's Word: Reallypishoi gergesNo ratings yet

- Search For Process To Produce Hot Metal 1995Document1 pageSearch For Process To Produce Hot Metal 1995pishoi gergesNo ratings yet

- Prasad 1999Document9 pagesPrasad 1999pishoi gergesNo ratings yet

- Emotion On Display: Your You You You You YouDocument3 pagesEmotion On Display: Your You You You You Youpishoi gergesNo ratings yet

- Biblico 6Document4 pagesBiblico 6pishoi gergesNo ratings yet

- Hiding From God's Word: ReallyDocument3 pagesHiding From God's Word: Reallypishoi gergesNo ratings yet

- Biblico 5Document4 pagesBiblico 5pishoi gergesNo ratings yet

- Without Rightly Discerning What's Revealed Only in The Bible, We Cannot Know The Most Important Realities in Life.Document8 pagesWithout Rightly Discerning What's Revealed Only in The Bible, We Cannot Know The Most Important Realities in Life.pishoi gergesNo ratings yet

- Biblico 9Document3 pagesBiblico 9pishoi gergesNo ratings yet

- Without Rightly Discerning What's Revealed Only in The Bible, We Cannot Know The Most Important Realities in Life.Document8 pagesWithout Rightly Discerning What's Revealed Only in The Bible, We Cannot Know The Most Important Realities in Life.pishoi gergesNo ratings yet

- Beware The Book: The Girl He LikesDocument3 pagesBeware The Book: The Girl He Likespishoi gergesNo ratings yet

- God's Word Over Man's: Habakkuk 2:14Document3 pagesGod's Word Over Man's: Habakkuk 2:14pishoi gergesNo ratings yet

- Emotion On Display: Your You You You You YouDocument3 pagesEmotion On Display: Your You You You You Youpishoi gergesNo ratings yet

- Wonder of Having: "No Word of God Is A Dead Word."Document5 pagesWonder of Having: "No Word of God Is A Dead Word."pishoi gergesNo ratings yet

- Three Fatal Dreams: But GodDocument5 pagesThree Fatal Dreams: But Godpishoi gergesNo ratings yet

- Biblico 6Document4 pagesBiblico 6pishoi gergesNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 82.191.49.154 On Sun, 27 Sep 2020 22:15:32 UTCDocument22 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 82.191.49.154 On Sun, 27 Sep 2020 22:15:32 UTCpishoi gergesNo ratings yet

- To See Biblical Reality As True and Real, We Need New Eyes.Document5 pagesTo See Biblical Reality As True and Real, We Need New Eyes.pishoi gergesNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 82.191.49.154 On Sun, 27 Sep 2020 22:12:33 UTCDocument11 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 82.191.49.154 On Sun, 27 Sep 2020 22:12:33 UTCpishoi gergesNo ratings yet

- Wordlist Unit 7Document4 pagesWordlist Unit 7Anastasiia SokolovaNo ratings yet

- The Petrosian System Against The QID - Beliavsky, Mikhalchishin - Chess Stars.2008Document170 pagesThe Petrosian System Against The QID - Beliavsky, Mikhalchishin - Chess Stars.2008Marcelo100% (2)

- Data Warga RT 02 PDFDocument255 pagesData Warga RT 02 PDFeddy suhaediNo ratings yet

- TolemicaDocument101 pagesTolemicaPrashanth KumarNo ratings yet

- Carl Rogers Written ReportsDocument3 pagesCarl Rogers Written Reportskyla elpedangNo ratings yet

- Family Code Cases Full TextDocument69 pagesFamily Code Cases Full TextNikki AndradeNo ratings yet

- Web DesignDocument2 pagesWeb DesignCSETUBENo ratings yet

- 1.1 Cce To Proof of Cash Discussion ProblemsDocument3 pages1.1 Cce To Proof of Cash Discussion ProblemsGiyah UsiNo ratings yet

- A Documentary Report of Work Immersion Undertaken at The City Mayor'S OfficeDocument17 pagesA Documentary Report of Work Immersion Undertaken at The City Mayor'S OfficeHamdan AbisonNo ratings yet

- Easter in South KoreaDocument8 pagesEaster in South KoreaДіана ГавришNo ratings yet

- Colville GenealogyDocument7 pagesColville GenealogyJeff MartinNo ratings yet

- Ethiopia Pulp & Paper SC: Notice NoticeDocument1 pageEthiopia Pulp & Paper SC: Notice NoticeWedi FitwiNo ratings yet

- Final Annexes Evaluation Use Consultants ApwsDocument51 pagesFinal Annexes Evaluation Use Consultants ApwsSure NameNo ratings yet

- JONES - Blues People - Negro Music in White AmericaDocument46 pagesJONES - Blues People - Negro Music in White AmericaNatalia ZambaglioniNo ratings yet

- Case Study For Southwestern University Food Service RevenueDocument4 pagesCase Study For Southwestern University Food Service RevenuekngsniperNo ratings yet

- Memorandum1 PDFDocument65 pagesMemorandum1 PDFGilbert Gabrillo JoyosaNo ratings yet

- My Portfolio: Marie Antonette S. NicdaoDocument10 pagesMy Portfolio: Marie Antonette S. NicdaoLexelyn Pagara RivaNo ratings yet

- MhfdsbsvslnsafvjqjaoaodldananDocument160 pagesMhfdsbsvslnsafvjqjaoaodldananLucijanNo ratings yet

- Sculi EMT enDocument1 pageSculi EMT enAndrei Bleoju100% (1)

- Viking Solid Cone Spray NozzleDocument13 pagesViking Solid Cone Spray NozzlebalaNo ratings yet

- Case 1. Is Morality Relative? The Variability of Moral CodesDocument2 pagesCase 1. Is Morality Relative? The Variability of Moral CodesalyssaNo ratings yet

- Keys For Change - Myles Munroe PDFDocument46 pagesKeys For Change - Myles Munroe PDFAndressi Label100% (2)

- Decline of Mughals - Marathas and Other StatesDocument73 pagesDecline of Mughals - Marathas and Other Statesankesh UPSCNo ratings yet

- Bond by A Person Obtaining Letters of Administration With Two SuretiesDocument2 pagesBond by A Person Obtaining Letters of Administration With Two Suretiessamanta pandeyNo ratings yet

- IMS Checklist 5 - Mod 4Document9 pagesIMS Checklist 5 - Mod 4Febin C.S.No ratings yet

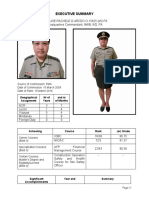

- Executive Summary: Source of Commission: PMA Date of Commission: 16 March 2009 Date of Rank: 16 March 2016Document3 pagesExecutive Summary: Source of Commission: PMA Date of Commission: 16 March 2009 Date of Rank: 16 March 2016Yanna PerezNo ratings yet

- 3-16-16 IndyCar Boston / Boston Grand Prix Meeting SlidesDocument30 pages3-16-16 IndyCar Boston / Boston Grand Prix Meeting SlidesThe Fort PointerNo ratings yet

- Swepp 1Document11 pagesSwepp 1Augusta Altobar100% (2)

- SOL 051 Requirements For Pilot Transfer Arrangements - Rev.1 PDFDocument23 pagesSOL 051 Requirements For Pilot Transfer Arrangements - Rev.1 PDFVembu RajNo ratings yet

- Roads of Enlightenment GuideDocument5 pagesRoads of Enlightenment GuideMicNo ratings yet