Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Guideline Di

Uploaded by

Boris ChapelletOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Guideline Di

Uploaded by

Boris ChapelletCopyright:

Available Formats

REFERENCE MANUAL V 36 / NO 6 14 / 15

Guideline on Dental Management of Heritable

Dental Developmental Anomalies

Originating Council

Council on Clinical Affairs

Adopted

2008

Revised

2013

Purpose hand searches, were performed. This strategy yielded 131

The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) recog- articles. Articles for review were chosen from this list and from

nizes that pediatric dentists are uniquely qualified to manage references within selected articles. Thirty-nine articles each

the oral health care needs of children with heritable dental had full examination and analysis in order to revise this guide-

developmental anomalies. These children have multiple, com- line. When data did not appear sufficient or were inconclusive,

plex problems as their dental conditions affect both form and recommendations were based upon expert and/or consensus

function and can have significant psychological impact. These opinion by experienced researchers and clinicians.

conditions may present early in life and require both immediate

intervention and management of a protracted nature, including Background

coordination of multi-disciplinary care. The AAPD’s Guideline Anomalies of tooth development are relatively common and

on Management of Dental Patients with Special Health Care may occur as an isolated condition or in association with other

Needs1 alludes to this patient population but does not make anomalies. Developmental dental anomalies often exhibit

specific treatment recommendations for the oral manifestations patterns that reflect the stage of development during which the

of such diagnoses. This guideline is intended to address the malformation occurs. For example, disruptions in tooth initi-

diagnosis, principles of management, and objectives of therapy ation result in hypodontia or supernumerary teeth, whereas

of children with heritable dental developmental anomalies disruptions during morphodifferentiation lead to anomalies of

rather than provide specific treatment recommendations. This size and shape (eg, macrodontia, microdontia, taurodontism,

guideline will focus on the following heritable dental develop- dens invaginatus).3 Disruptions occurring during histodiffer-

mental anomalies: amelogenesis imperfecta (AI), dentinogenesis entiation, apposition, and mineralization result in enamel

imperfecta (DI), and dentin dysplasia (DD). Ectodermal dys- hypoplasia or hypomineralization4,5 for AI, DI, and DD.3

plasia has been thoroughly studied and reported in the Heritable dental developmental anomalies can have

National Foundation for Ectodermal Dysplasia’s “Parameters profound negative consequences for the affected individual

of Oral Health Care for Individuals Affected by Ectodermal and the family.6,7 Preventive care is of foremost importance.

Dysplasia Syndromes.”2 Refer to that document for care of Meticulous oral hygiene must be established and maintained,8

children with ectodermal dysplasia. The problems range from esthetic concerns that impact self-

esteem to masticatory difficulties, tooth sensitivity, financial

Methods burdens, and protracted, complex dental treatment. These

This revision is an update of a guideline adopted in 2008. It is emotional and physical strains have been demonstrated, show-

based upon a review of the current dental and medical litera- ing that persons with AI have fewer long-term relationships

ture related to heritable dental developmental anomalies. A and children than nonaffected people. 6 Due to extensive

systematic literature search of the PubMed® database was con- treatment needs, a patient may require sedation or general

ducted using the following parameters: Terms: “heritable dental anesthesia for restorative care.9

developmental anomalies”, “amelogenesis imperfecta”, “den-

tinogenesis imperfecta”, “dentinal dysplasia”, “dentin dysplasia”, Amelogenesis imperfecta

“enamel hypoplasia”, “enamel hypocalcification”, “amelogenin”, Amelogenesis imperfecta is a developmental disturbance that

and “enamelin”; Fields: all; Limits: within the last 10 years, interferes with normal enamel formation in the absence of a

humans, English, clinical trials, birth through age 18. One systemic disorder.7,10 In general, it affects all or nearly all of

thousand five hundred and twenty one articles matched these the teeth in both the primary and permanent dentitions. 7-11

criteria. Alternate strategies such as appraisal of references from The estimated frequency of AI ranges from one in 718 to

recent evidence-based reviews and meta-analyses, as well as one in14,000 depending on the population studied.12,13

264 CLINICAL GUIDELINES

AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRIC DENTISTRY

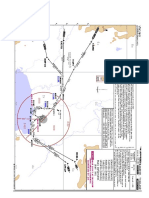

Figure 1. Amelogenesis imperfecta. Diagram

of enamel defects of basic types. Hypocalcified

- normal thickness, smooth surface, less hard-

ness. Hypoplastic, pitted - normal thickness,

pitted surface, normal hardness. Hypoplastic,

generalized - reduced thickness, smooth surface,

normal hardness. Hypomaturation - normal

thickness, chipped surface, less hardness, opaque

white coloration.

This figure was published in Contemporary Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, Sapp J, Eversole L, Wysocki G; Developmental Disturbances of the

Oral Region, page 19; Mosby, Inc. 2004.18

Genetic etiology: AI may be inherited by x-linked or sporadic ankylosis have been reported.21 In addition, the incidence of

inheritance. The different clinical manifestations of AI have anterior open bite is 50 percent in hypoplastic AI, 31 percent

a specific gene anomaly associated with each phenotype.10-12 in hypomaturation AI, and 60 percent of hypocalcified AI.20,23

Specific mutations proven to cause AI include: amelogenin

(AMELX), enamelin (ENAM), kallikrein4 (KLK4), enamel- Differential diagnosis: Other forms of enamel dysmineralization

ysis (MMP-20) and FAM83H.10,14-16 will exhibit a pattern based upon the time of insult, thus affect-

ing the enamel forming at the time. In contrast, AI will affect

Clinical manifestation: The most widely accepted classification13 all teeth similarly and can have a familial history. Fluorosis

of AI includes four types: hypoplastic, hypomaturation, hypo- can mimic AI, but usually the teeth are not affected uniformly,

calcified, and hypomaturation-hypoplastic with taurodontism. often sparing the premolars and second permanent molars. A

Each type has subtypes differentiated by mode of inheritance. history of fluoride intake can aid in the diagnosis.

This classification system takes into consideration 15 subtypes

based on clinical features and inheritance pattern. Figure 1 Dentinogenesis imperfecta

represents the basic types of emanel defects seen in AI. The Dentinogenesis imperfecta is a hereditary developmental dis-

variability of the appearance of the different types of AI makes turbance of the dentin originating during the histodiffer-

identification difficult.15 Some dentitions will appear normal entiation stage of tooth development. DI may be seen alone

to the untrained eye while other types of AI will be disfiguring. or in conjunction with the systemic hereditary disorder of the

Hypomaturation-hypoplastic with taurodontism type of AI bone, osteogenesis imperfecta. Children with unexplained

also is associated with tricho-dento-osseous syndrome.19 bone fracturing should be evaluated for DI as a possible

Children with AI can exhibit accelerated tooth eruption indicator of an undiagnosed case of OI. This is important in

compared to the normal population or have late eruption.20-25 helping delineate child abuse from mild or undiagnosed

Other clinical implications of AI include low caries suscepti- OI. 27 The incidence of DI is about one in 8000. 28 Two

bility, rapid attrition, excessive calculus deposition, and gingival systems, one by Witkop28 and the other by Shields29, are well

hyperplasia. 25 Pathologies associated with AI are enlarged accepted classification systems of DI (See Table 1).

follicles, impacted permanent teeth, ectopic eruption, con-

genitally missing teeth, crown and/or root resorption, and pulp Genetic etiology: Type I collagen (product of COL1A1 and

calcification.21,24-26 Agenesis of second molars also has been COL1A2 genes) is the most abundant dentin protein.30 The

observed.22 Although uncommon in AI, enamel resorption and diverse mutations associated with the COL1A1 and COL1A2

Table 1. DENTINOGENESIS IMPERFECTA*

Shields Clinical Presentation Witkop

Dentinogenesis Imperfecta I Osteogenesis Imperfecta with opalescent teeth Dentinogenesis Imperfecta

Dentinogenesis Imperfecta II Isolated Dentinogenesis Imperfecta Hereditary Opalescent Dentin

Dentinogenesis Imperfecta III Isolated Dentinogenesis Imperfecta Brandywine Isolate

* This table was published in Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, 3rd ed, Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Bouquot JE, Abnormalities of Teeth, page 106,

Copyright Saunders/Elsevier, 2009.8

CLINICAL GUIDELINES 265

REFERENCE MANUAL V 36 / NO 6 14 / 15

genes can cause the DI phenotype in association with osteo- Clinical manifestation: In 1973, Shields and colleagues pro-

genesis imperfecta (DI type I). DI Type II and Type III are posed a classification system of dentinal dysplasia.23

autosomal dominant conditions that have been linked to chro- Dentin Dysplasia Type I (radicular dentin dysplasia;

mosome 4q12-21, suggesting these may be allelic mutations rootless teeth):7-9,33 The crowns in DD Type I appear mostly

of the DSPP gene encoding dentin phosphoprotein and normal in color and shape in both the primary and perma-

dentin sialoprotein.31,32 nent dentitions. Occasionally, an amber translucency is ap-

parent. The roots tend to be short and sharply constricted. DD

Clinical manifestation: In all three DI types, the teeth have a Type I has been referred to as “rootless teeth” because of the

variable blue-gray to yellow-brown discoloration that appears shortened root length due to a loss of organization of root

opalescent due to the defective, abnormally-colored dentin dentin. Wide variation of root formation and pulp formation

shining through the translucent enamel. Due to the lack of exists due to the timing of dentinal disorganization. With

support of the poorly mineralized dentin, enamel frequently early disorganization, the roots are extremely short or absent

fractures from the teeth leading to rapid wear and attrition of and no pulp can be detected. With later disorganization, the

the teeth. The severity of discoloration and enamel fracturing roots are shortened with crescent or chevron-shaped pulp

in all DI types is highly variable, even within the same family. chambers. With late disorganization, typical root lengths exist

If left untreated, it is not uncommon to see the entire DI- with pulp stones present in a normal shaped pulp chambers.

affected dentition worn to the gingiva. This variability is most profound in the permanent dentition

Shields Type I occurs with osteogenesis imperfecta. All and can vary for each person and from tooth to tooth in a

teeth in both dentitions are affected. Primary teeth are affected single individual.

most severely, followed by the permanent incisors and first Radiographically, the roots of all teeth in the primary and

molars, with the second and third molars being the least permanent dentitions are either short or abnormally shaped.

altered. Radiographically, the teeth have bulbous crowns, cer- The primary teeth have obliterated pulps that completely fill

vical constriction, thin roots, and early obliteration of the root in before eruption. The extent of pulp canal and chamber

canal and pulp chambers due to excessive dentin production. obliteration in the permanent dentition is variable. Both the

Periapical radiolucencies and root fractures are evident. An primary and permanent teeth demonstrate multiple periapical

amber translucent tooth color is common. radiolucencies. They represent chronic abscesses, granulomas,

Shields Type II is also known as hereditary opalescent or cysts. The inflammatory lesions appear secondary to caries

dentin. Both primary and permanent dentitions are equally or spontaneous coronal exposure of microscopic threads of

affected, and the characteristics previously described for Type pulpal remnants present within the defective dentin.

I are the same. Radiographically, pulp chamber obliteration Dentin Dysplasia Type II (coronal dentin dysplasia):7-9,33

can begin prior to tooth eruption. DD Type II demonstrates numerous features of DI. In con-

Shields Type III is rare; its predominant characteristic is trast to DD Type I, root lengths are normal in both dentitions.

bell-shaped crowns, especially in the permanent dentition. Un- The primary teeth are amber-colored closely resembling DI.

like Types I and II, Type III involves teeth with shell-like Radiographically, the primary teeth exhibit bulbous crowns,

appearance and multiple pulp exposures. Shell teeth demon- cervical constrictions, thin roots, and early pulp obliteration.

strate normal-thickness enamel in association with extremely The permanent teeth are normal in coloration. Radiographic-

thin dentin and dramatically enlarged pulps. The thin dentin ally, they exhibit thistle-tube shaped pulp chambers with

may involve the entire tooth or be isolated to the root. multiple pulp stones; periapical radiolucencies are not present.

Differential diagnosis: OI, other collagen disorders, and nu- Differential diagnosis: The first differential diagnosis for DD

merous syndromes have DI-like phenotypes associated with Type II is DI. The differentiation between DD and DI can

them. DD Type I clinically has normal appearing crowns, but be challenging because these two developmental anomalies

radiographically the teeth have pulpal obliterations and short form a continuum. 7 Both DD and DI have amber tooth

blunted roots. DD Type II has the same phenotype as DI coloration and obliterated or occluded pulp chambers. How-

Type II in the primary dentition but normal to slight blue- ever, the pulp chambers do not fill in before eruption in DD

gray discoloration in permanent dentition. Type II. A finding of a thistle-tube shaped pulp chamber in a

single-rooted tooth increases the likelihood of DD diagnosis.

Dentin dysplasia The crowns in DD usually are normal in size, shape, and pro-

Dentin dysplasia represents another group of inherited den- portion while the crowns in DI typically are bell-shaped

tin disorders resulting in characteristic features involving the with a cervical constriction. The roots in DD usually are not

dentin and root morphology. DD is rarer than DI, affecting present or appear normal while the roots in DI typically are

one in 100,000.3 short and narrow. Association of periapical radiolucencies with

non-carious teeth and without obvious cause is an important

Genetic etiology: DD exhibits an autosomal dominant pattern characteristic of DD Type I.7,8

of inheritance.7-9 An unrelated disorder with pulpal findings similar to DD

Type II is pulpal dysplasia.8 This process occurs in teeth that

266 CLINICAL GUIDELINES

AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRIC DENTISTRY

appear clinically normal. Radiographically, pulpal dysplasia seling for the child or adolescent and his/her family should

exhibits thistle-tube shaped pulp chambers and multiple pulp be recommended when negative psychosocial consequences

stones in the both the primary and permanent dentitions. of the disorder are recognized.

Recommendations Dentinogenesis imperfecta

Amelogenesis imperfecta General considerations and principles of management: Providing

General considerations and principles of management: A primary optimal oral health treatment for DI frequently includes pre-

goal for treatment is to address each concern as it presents but venting severe attrition associated with enamel loss and rapid

with an overall comprehensive plan that outlines anticipated wear of the poorly mineralized dentin, rehabilitating dentitions

future treatment needs. Clinicians treating children and adoles- that have undergone severe wear, optimizing esthetics, and

cents with AI must address the clinical and emotional demands preventing caries and periodontal disease. The dental approach

of these disorders with sensitivity. It is important to establish for managing DI will vary depending on the severity of the

good rapport with the child and family early. Timely inter- clinical expression.

vention is critical to spare the patient from the psychosocial The clinician must be cautious in treating individuals with

consequences of these potentially disfiguring conditions. A OI if performing surgical procedures or other treatment that

comprehensive and timely approach is reassuring to the could transmit forces to the jaws, increasing the risk of bone

patient and family and may help decrease their anxiety.6 fracture. Some types of protective stabilization may be con-

traindicated in the patients with OI.

Preventive care: Early identification and preventive interven-

tions are critical for infants and children with AI in order to Preventive care: Early identification and preventive interven-

avoid the negative social and functional consequences of the tions are critical for individuals with DI in order to avoid the

disorder. Regular periodic examinations can identify teeth negative social and functional consequences of the disorder.

needing care as they erupt. Meticulous oral hygiene, calculus Regular periodic examinations can identify teeth needing care

removal, and oral rinses can improve periodontal health. Fluo- as they erupt. Meticulous oral hygiene, calculus removal, and

ride applications and desensitizing agents may diminish tooth oral rinses can improve periodontal health. Fluoride applica-

sensitivity.35,36 tions and desensitizing agents may diminish tooth sensitivity.35,36

Restorative care: The appearance, quality, and amount of Restorative care: Routine restorative techniques often can be

affected enamel and dentin will dictate the type of restorations used effectively to treat mild to moderate DI. These treatments

necessary to achieve esthetic, masticatory, and functional more commonly are applied to the permanent teeth, as the

health. 35,39,40 When the enamel is intact but discolored, permanent dentition frequently is less severely affected than

bleaching and/or microabrasion may be used to enhance the the primary dentition. In more severe cases with significant

appearance.36,37 If the enamel is hypocalcified, composite resin enamel fracturing and rapid dental wear, the treatment of choice

or porcelain veneers may be able to be retained with bond- is full coverage restorations in both the primary and permanent

ing.28 If the enamel or dentin cannot be bonded, full coverage dentitions.49-51 The success of full coverage is greatest in teeth

restorations will be required.19,31-42 In order to facilitate veneer with crowns and roots that exhibit close to a normal shape

or crown placement, periodontal therapy may be necessary and size, minimizing the risk of cervical fracture.49-51

when acute/chronic marginal gingivitis along with hyperplastic Ideally, restorative stabilization of the dentition will be

tissue exists.34,39-4241-48 completed before excessive wear and loss of vertical dimension

During the primary dentition, it is important to restore occur.54 Cases with significant loss of vertical dimension will

the teeth for adequate function and to maintain adequate arch benefit from reestablishing a more normal vertical dimension

parameters. Primary teeth may require composite or veneered during dental rehabilitation. Cases having severe loss of cor-

anterior crowns with posterior full coverage steel or veneered onal tooth structure and vertical dimension may be considered

crowns.44,49,50 candidates for overdenture therapy. Overlay dentures placed

The permanent dentition usually involves a complex treat- on teeth that are covered with fluoride-releasing glass ionomer

ment plan with specialists from multiple disciplines.46,48,51 Peri- cement have been used with success.8

odontics, endodontics, and orthodontics may be necessary Bleaching has been reported to lighten the color of DI

and treatment could include orthognathic surgery.44,46,52,53 The teeth with some success; however, because the discoloration is

prosthetic treatment may require veneers, full coverage crowns, caused primarily by the underlying yellow-brown dentin,

implants, and fixed or removable prostheses. 39,45,48,51-53 The bleaching alone is unlikely to produce normal appearance in

fabrication of an occlusal splint may be needed to reestablish cases of significant discoloration. Different types of veneers can

vertical dimension when full mouth rehabilitation is neces- be used to improve the esthetics and mask the opalescent

sary.22,49-51 Therapy will need to be planned carefully in phases blue-gray discoloration of the anterior teeth.

as teeth erupt and the need arises.

Behavior guidance, as well as the psychological health of Endodontic considerations: Some patients with dentinogen-

the patient, will need to be addressed in each phase. 6 Coun- esis imperfecta will suffer from multiple periapical abscesses

CLINICAL GUIDELINES 267

REFERENCE MANUAL V 36 / NO 6 14 / 15

apparently resulting from pulpal strangulation secondary to ectodermal dysplasias. National Foundation for Ecto-

pulpal obliteration or from pulp exposure due to extensive co- dermal Dysplasias. Mascoutah, Ill; 2003, Revision 2007.

ronal wear. The potential for periapical abscesses is an Available at: “http://nfed.org/uploads/parameters.pdf ”.

indication for periodic radiographic surveys on individuals Accessed July 3, 2013.

with DI. Because of pulpal obliteration, apical surgery may be 3. Slayton RL. Congenital genetic disorders and syndromes.

required to maintain the abscessed teeth. Attempting to nego- In: Casamassimo PS, Fields HW Jr, McTigue DJ, Nowak

tiate and instrument obliterated canals in DI teeth can result AJ, eds. Pediatric Dentistry: Infancy through Adolescence.

in lateral perforation due to the poorly mineralized dentin. 5th ed. St. Louis, Mo: Elsevier/Saunders; 2013:242-5.

4. William V, Messer LB, Burrow MF. Molar hypominer-

Occlusion: Class III malocclussion with high incidences of alization: Review and recommendations for clinical man-

posterior crossbites and openbites occur in DI Type I and agement. Pediatr Dent 2006;28(3):224-32.

should be evaluated. 55 Multidisciplinary approaches are 5. Elfrink ME, ten Cate JM, Jaddoe VW, Hofman A, Moll

essential in addressing the complex needs of the individuals HA, Veerkamp JS. Deciduous molar hypomineralization

affected with DI. and molar incisor hypomineralization. J Dent Res 2012;

91(6):551-5.

Dentin dysplasia 6. Coffield K, Philips C, Brady M, Roberts M, Strauss R,

General considerations and principles of management 9: The goal Wright JT. The psychosocial impact of developmental

of treatment is to retain the teeth for as long as possible. dental defects in people with hereditary amelogenesis

However, due to shortened roots and periapical lesions, the imperfecta. J Am Dent Assoc 2005;136(5):620-30.

prognosis for prolonged tooth retention is poor. Prosthetic 7. White SC, Pharoah MJ. Dental anomalies. In: Oral Ra-

replacement including dentures, overdentures, partial dentures, diology: Principles and Interpretation. 5th ed. St. Louis,

and/or dental implants may be required. Mo: Mosby/Elsevier; 2009:307-11.

8. Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Bouquot JE. Abnor-

Preventive care 3: Meticulous oral hygiene must be established malities of Teeth. In: Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology. 3rd

and maintained. As a result of shortened roots with DD Type ed. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders Company; 2009:99-112.

I, early tooth loss from periodontitis is frequent. 9. Quiñonez R, Hoover R, Wright JT. Transitional anterior

esthetic restorations for patients with enamel defects.

Restorative care: Teeth with DD Type I have such poor crown Pediatr Dent 2000;22(1):65-7.

to root ratios that prosthetic replacement including dentures, 10. Wright JT, Torain M, Long K, et al. Amelogenesis imper-

overdentures, partial dentures, and/or dental implants are the fecta: Genotype-phenotype studies in 71 families. Cells

only practical courses for dental rehabilitation.3 Teeth with Tissues Organs 2011;194(2-4):279-83.

DD Type II that are of normal shape, size, and support can 11. Regezi JA, Sciubba JJ, Jordan RCK. Abnormalities of

be restored with full coverage restorations if necessary. For teeth. In: Oral Pathology: Clinical-Pathologic Correlations.

esthetics, discolored anterior teeth can be improved with resin 5th ed. St. Louis, Mo: WB Saunders/Elsevier; 2008:369-72.

bonding, veneering, or full coverage esthetic restorations. 12. Bäckman B, Holmgren G. Amelogenesis imperfecta: A

Clinicians should be aware that even shallow occlusal re- genetic study. Human Heredity 1988;38(4):189-206.

storations may result in pulpal necrosis due to the pulpal 13. Witkop CJ. Amelogenesis imperfecta, dentinogenesis im-

vascular channels that extend close to the dentin-enamel perfecta and dentin dysplasia revisited: Problems in classi-

junction.8 If periapical inflammatory lesions develop, the fication. J Oral Pathol 1988;17(9-10):547-53.

treatment plan is guided by the root length.8 14. Hu J, Simmer J. Developmental biology and genetics of

dental malformations. Orthod Craniofac Res 2007;10(2):

Endodontic considerations: Endodontic therapy, negotiating 45-52.

around pulp stones and through whorls of tubular dentin, has 15. Stephanopoulos G, Garefalaki M, Lyroudia K. Genes and

been successful in teeth without extremely short roots. Peria- related proteins involved in amelogenesis imperfecta. J

pical curettage and retrograde amalgam seals have demon- Dent Res 2005;84(12):1117-26.

strated short-term success in teeth with short roots. 16. Aldred M, Savarirayan R, Crawford P. Amelogenesis

imperfecta: A classification and catalogue for the 21st cen-

Ectodermal dysplasia tury. Oral Dis 2003;9(1):19-23.

The AAPD endorses the National Foundation for Ectodermal 17. Kim J, Simmer J, Lin B, Seymen F, Bartlett J, Hu J. Mu-

Dysplasia’s “Parameters of Oral Health Care for Individuals tational analysis of candidate genes in 24 amelogenesis

Affected by Ectodermal Dysplasia Syndromes.”2 imperfecta families. Eur J Oral Sci 2006;114(suppl 1):

3-12, 39-41.

References 18. Sapp J, Eversole L, Wysocki G. Developmental distur-

1. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on bances of the oral region. In: Contemporary Oral and

management of dental patients with special health care Maxillofacial Pathology. 2nd ed. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby Inc;

needs. Pediatr Dent 2012;30(special issue):152-7. 2004:17-20.

2. National Foundation for Ectodermal Dysplasias. Para- 19. Hart T, Bowden D, Bolyard J, Kula K, Hall K, Wright

meters of oral health care for individuals affected by JT. Genetic linkage of the tricho-dento-osseous syndrome

268 CLINICAL GUIDELINES

AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRIC DENTISTRY

to chromosome 17q2.1 Hum Mol Genet 1997;6(13): 38. Arnetzl GV, Arnetzl G. Adhesive techniques and machi-

2279-84. neable high-performance polymer restorations for am-

20. Aren G, Ozdemir D, Firatli S, Uygur C, Sepet E, Firatli elogenesis imperfecta in mixed dentition. Int J Comput

E. Evaluation of oral and systemic manifestations in an Dent 2011;14(2):129-38.

amelogenesis imperfecta population. J Dent Res 2003;31 39. Lindunger A, Smedberg J. A retrospective study of the

(8):585-91. prosthodontic management of patients with amelo-

21. Seow W. Dental development in amelogenesis imperfecta: genesis imperfecta. Int J Prosth 2005;18(3):189-94.

A controlled study. Pediatr Dent 1995;17(1):26-30. 40. Seymen F, Kiziltan B. Amelogenesis imperfecta: A scan-

22. Yip H, Smales R. Oral rehabilitation of young adults with ning electron microscopic and histopathologic study. J

amelogenesis imperfecta. Int J Prosth 2003;16(4):345-9. Clin Pediatr Dent 2002;26(4):327-35.

23. Crawford P, Aldred M, Bloch-Zupan A. Amelogenesis 41. Muhney K, Campbell PR. Pediatric dental management

imperfecta. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2007;4(2):17. of a patient with osteogenesis imperfecta and dentino-

24. Wright J, Robinson C, Kirkham J. Enamel protein in genesis imperfecta. Spec Care Dent 2007;27(6):240-5

smooth hypoplastic amelogenesis imperfecta. Pediatr 42. Ashkenazi M, Sarnat H. Microabrasion of teeth with discol-

Dent 1992;14(5):331-7. oration resembling hypomaturation enamel defects: Four-

25. Poulsen S, Gjorup H, Haubek D, et al. Amelogenesis year follow up. J Clin Pediatr Dent 2000;25(1):29-34.

imperfecta – A systematic literature review of associated 43. Dale B. Bleaching and related agents. In: Esthetic Den-

dental and oro-facial abnormalities and their impact on tistry: A Clinical Approach to Techniques and Materials.

patients. Acta Odontol Scand 2008;66(4):193-9. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby Inc; 2001:245-55.

26. Ravassipour D, Powell C, Phillips C, et al. Variation in 44. Williams W, Becker L. Amelogenesis imperfecta: Func-

dental and skeletal open bite malocclusion in humans tional and esthetic restoration of a severely compromised

with amelogenesis imperfecta. Arch Oral Bio 2005;50(7): dentition. Quintessence Int 2000;31(6):397-403.

611-23. 45. Robinson F, Haubenreich J. Oral rehabilitation of a

27. Wright J, Thornton J. Osteogenesis imperfecta with den- young adult with hypoplastic amelogenesis imperfecta: A

tinogenesis imperfecta: A mistaken case of child abuse. clinical report. J Prosth Dent 2006;95(1):10-3.

Pediatr Dent 1983;5(3):207-9. 46. Encinas R, Garcia-Espona I, Mondelo J. Amelogenesis

28. Witkop CJ. Hereditary defects in enamel and dentin. imperfecta: Diagnosis and resolution of a case with hypo-

Acta Genet Stat Med 1957;7(1):236-9. plasia and hypocalcification of enamel, dental agenesis,

29. Shields ED, Bixler D, el-kafrawy AM. A proposed classi- and skeletal open bite. Quintessence Int 2001;32(3):183-9.

fication for heritable human dentine defects with a de- 47. Brennan M, O’Connell B, Rams T, O’Connell A. Man-

scription of a new entity. Arch Oral Biol 1973;18(4): agement of gingival overgrowth associated with general-

543-53. ized enamel defects in a child. J Clin Pediatr Dent 1999;

30. Linde A, Goldberg M. Dentinogenesis. Crit Rev Oral 23(2):97-101.

Biol Med 1993;4(5):679-728. 48. Turkün L. Conservative restoration with resin composites

31. Takagi Y, Sasaki S. A probable common disturbance in of a case of amelogenesis imperfecta. Int Dent J 2005;

the early stage of odontoblast differentiation in dentino- 55(1):38-41.

genesis imperfecta type I and type II. J Oral Pathol 1988; 49. Kwok-Tung L, King N. The restorative management of

17(5):208-12. amelogenesis imperfecta in the mixed dentition. J Clin

32. MacDougall M, Jeffords L, Gu T, et al. Genetic linkage of Pediatr Dent 2006;31(2):130-5.

the dentinogenesis imperfecta type III locus to chromo- 50. Vitkov L, Hannig M, Krautgartner W. Restorative ther-

some 4q. J Dent Res 1999;78(6):1277-82. apy of primary teeth severely affected by amelogenesis

33. Dummett CO Jr. Anomalies of the developing dentition. imperfecta. Quintessence Int 2006;37(3):219-24.

In: Pinkham JR, Casamassimo PS, Fields HW Jr, McTigue 51. Ozturk N, Sari Z, Ozturk B. An interdisciplinary ap-

DJ, Nowak AJ, eds. Pediatric Dentistry: Infancy through proach for restoring function and esthetics in a patient

Adolescence. 4th ed. St. Louis, Mo: Elsevier Saunders; with amelogenesis imperfecta and malocclusion: A

2005:61-73. clinical report. J Prosth Dent 2004;92(2):112-5.

34. Markovic D, Petrovic B, Peric T. Case series: Clinical find- 52. Bäckman B, Adolfsson U. Craniofacial structure related

ings and oral rehabilitation of patients with amelogenesis to inheritance pattern in amelogenesis imperfecta. Am J

imperfecta. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent 2010;11(4):201-8. Orthod Dentofac Orthop 1994;105(6):575-82.

35. Sapir S, Shapira J. Clinical solutions for developmental 53. Hoppenreijs T, Voorsmic R, Freihofer H, van ’t Hof M.

defects of enamel and dentin in children. Pediatr Dent Open bite deformity in amelogenesis imperfecta Part 2:

2007;29(4):330-6. Le Fort 1 osteotomies and treatment results. J Cranio-

36. Hicks J, Flaitz C. Role of remineralizing fluid in in vitro maxillofacial Surg 1998;26(5):286-93.

enamel caries formation and progression. Quintessence 54. Sapir S, Shapira J. Dentinogenesis imperfecta: An early

Int 2007;38(4):313-24. treatment strategy. Pediatr Dent 2001;23(3):232-7.

37. Pavlic A, Battelino T, Trebusak Podkrajsek K, Ovsenik M. 55. O’Connell A, Marini J. Evaluation of oral problems in an

Craniofacial characteristics and genotypes of amelogenesis osteogenesis imperfecta population. Oral Surg Oral Med

imperfecta patients. Eur J Orthod 2011;33(3):325-31. Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1999;87(2):189-96.

CLINICAL GUIDELINES 269

You might also like

- Script For TourguidingDocument2 pagesScript For Tourguidingfshe2677% (125)

- Oral Pathology Mnemonics Online Course - PDF versionFrom EverandOral Pathology Mnemonics Online Course - PDF versionRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- B757-200 MPDDocument393 pagesB757-200 MPDSebastian Rendon100% (3)

- Mx81x Mx71x Service ManualDocument834 pagesMx81x Mx71x Service ManualCarlosNey0% (1)

- Solutions of Mini Case Bruce HoniballDocument5 pagesSolutions of Mini Case Bruce HoniballShivshankar Yadav100% (1)

- IndictmentDocument2 pagesIndictmentCBS Austin WebteamNo ratings yet

- Ceramic Inlays A Case Presentation and LessonsDocument11 pagesCeramic Inlays A Case Presentation and LessonsStef David100% (1)

- Guideline On Dental Management of Heritable Dental Developmental AnomaliesDocument6 pagesGuideline On Dental Management of Heritable Dental Developmental AnomaliesNicky MachareonsapNo ratings yet

- Amelogenesis ImperfectaDocument4 pagesAmelogenesis Imperfectamirfanulhaq100% (1)

- Amelogenesis Imperfecta Case Report ReviewDocument6 pagesAmelogenesis Imperfecta Case Report ReviewSurgaBetariJelitaNo ratings yet

- AmelogenezaDocument9 pagesAmelogenezaRuxandra FitaNo ratings yet

- Amelogenesis ImperfectaDocument16 pagesAmelogenesis ImperfectaRajat Kansal100% (1)

- Case report on amelogenesis imperfectaDocument4 pagesCase report on amelogenesis imperfectaIndomie GorengNo ratings yet

- Amelogenesis Imperfecta and Anterior Open Bite: Etiological, Classification, Clinical and Management InterrelationshipsDocument6 pagesAmelogenesis Imperfecta and Anterior Open Bite: Etiological, Classification, Clinical and Management InterrelationshipsMelisa GuerraNo ratings yet

- Multidisciplinary Management of A Child With Severe Open Bite and Amelogenesis ImperfectaDocument7 pagesMultidisciplinary Management of A Child With Severe Open Bite and Amelogenesis ImperfectaSelvaArockiamNo ratings yet

- Simultaneous Occurrence of Hypodontia and Microdontia in A Single CaseDocument3 pagesSimultaneous Occurrence of Hypodontia and Microdontia in A Single CaseNadeemNo ratings yet

- Manejo Clinico de La AI Hipoplasica NateraDocument15 pagesManejo Clinico de La AI Hipoplasica NateraDanitza GutiérrezNo ratings yet

- Australian Dental Journal - 2013 - Seow - Developmental Defects of Enamel and Dentine Challenges For Basic ScienceDocument12 pagesAustralian Dental Journal - 2013 - Seow - Developmental Defects of Enamel and Dentine Challenges For Basic Sciencelanasembraga1990No ratings yet

- Unraveling The Enigma of Amelogenesis Imperfecta: A Detailed Case ReportDocument5 pagesUnraveling The Enigma of Amelogenesis Imperfecta: A Detailed Case ReportInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Full-Mouth Adhesive Rehabilitation in A Case of Amelogenesis Imperfecta: A 5-Year Follow-Up Case ReportDocument20 pagesFull-Mouth Adhesive Rehabilitation in A Case of Amelogenesis Imperfecta: A 5-Year Follow-Up Case Report강북다인치과No ratings yet

- Amelogenesis Imperfekt Makalah Nurul - TranslatedDocument23 pagesAmelogenesis Imperfekt Makalah Nurul - Translatednurulia JanuartiNo ratings yet

- Amelogenesis ImperfectaDocument13 pagesAmelogenesis ImperfectaHema SinghNo ratings yet

- Manish PDFDocument4 pagesManish PDFLeena Losheene VijayakumarNo ratings yet

- HypoplasiaDocument7 pagesHypoplasiaSOMVIR KUMARNo ratings yet

- AnamolisDocument11 pagesAnamolisAbood SamoudiNo ratings yet

- Hypoplasia, Flurosis, Amelogenesis Imperfecta and Abnormal DVPT of ToothDocument49 pagesHypoplasia, Flurosis, Amelogenesis Imperfecta and Abnormal DVPT of ToothcrazieelorraNo ratings yet

- Tooth Fusion-A Rare Dental Anomaly: Analysis of Six CasesDocument5 pagesTooth Fusion-A Rare Dental Anomaly: Analysis of Six CasessafutriNo ratings yet

- Sri Maya Koas 15 - 5 - Managemen AmelogenesisDocument9 pagesSri Maya Koas 15 - 5 - Managemen AmelogenesisMaya MunggaranNo ratings yet

- Management of Amelogenesis Imperfecta in Adolescent Patients: Clinical ReportDocument6 pagesManagement of Amelogenesis Imperfecta in Adolescent Patients: Clinical ReportWafa FoufaNo ratings yet

- Giovani 2016Document5 pagesGiovani 2016Marina Miranda MirandaNo ratings yet

- Amelogenesis Imperfecta: Therapeutic Strategy From Primary To Permanent Dentition Across Case ReportsDocument8 pagesAmelogenesis Imperfecta: Therapeutic Strategy From Primary To Permanent Dentition Across Case ReportsbanyubiruNo ratings yet

- Lec 1 Developmental Disturbances of TeetDocument17 pagesLec 1 Developmental Disturbances of TeetRana SayedNo ratings yet

- Enamel HypoplasiaDocument2 pagesEnamel Hypoplasiakonda_siri83100% (1)

- JDentResRev2130-2809426 074814Document4 pagesJDentResRev2130-2809426 074814Sushma DhimanNo ratings yet

- Nonsyndromic Oligodontia With Ankyloglossia A Rare Case Report.20150306123428Document5 pagesNonsyndromic Oligodontia With Ankyloglossia A Rare Case Report.20150306123428dini anitaNo ratings yet

- Ecde 18 01168Document5 pagesEcde 18 01168Ahmad UraidziNo ratings yet

- CRID2015 579169 PDFDocument7 pagesCRID2015 579169 PDFNawaf RuwailiNo ratings yet

- Characteristics and Distribution of Dental Anomalies in Patients with CleftDocument9 pagesCharacteristics and Distribution of Dental Anomalies in Patients with CleftcareNo ratings yet

- AI Case Study Treatment from Childhood to AdulthoodDocument14 pagesAI Case Study Treatment from Childhood to AdulthoodBarbulescu Anca DianaNo ratings yet

- Non Syndromic Generalised MacrodontiaDocument4 pagesNon Syndromic Generalised MacrodontiaArum Kartika DewiNo ratings yet

- GRUPO 4 HIM-Caries Americano 2017Document11 pagesGRUPO 4 HIM-Caries Americano 2017Vanessa MinNo ratings yet

- Amelogenesis Imperfecta FinalDocument8 pagesAmelogenesis Imperfecta FinalAbdullah Muhammed khaleel HassanNo ratings yet

- Dentinogenesis Imperfecta: Type II in Children: A Scoping ReviewDocument8 pagesDentinogenesis Imperfecta: Type II in Children: A Scoping ReviewRoxana OneaNo ratings yet

- 14 R. NavasheillaDocument4 pages14 R. NavasheillafenimelaniNo ratings yet

- Clinical Management of Fusion in Primary Mandibular Incisors: A Systematic Literature ReviewDocument9 pagesClinical Management of Fusion in Primary Mandibular Incisors: A Systematic Literature ReviewRoxana OneaNo ratings yet

- Dentin Disorders Anomalies of Dentin Formation and StructureDocument21 pagesDentin Disorders Anomalies of Dentin Formation and Structureantoniolte12No ratings yet

- تقرير تشريح الاسنانDocument9 pagesتقرير تشريح الاسنانبكر بكرNo ratings yet

- Anodontia of Permanent Teeth - A Case ReportDocument3 pagesAnodontia of Permanent Teeth - A Case Reportanandsingh001No ratings yet

- A Case Report of Enamel Hypoplasia: Alka Hazari, Rana K Varghese, Aditya Mitra, Nivedita V BajantriDocument4 pagesA Case Report of Enamel Hypoplasia: Alka Hazari, Rana K Varghese, Aditya Mitra, Nivedita V BajantriRuxandra FitaNo ratings yet

- Jaber 2011Document6 pagesJaber 2011Alvaro LaraNo ratings yet

- Compound Odontoma Associated With Impacted Teeth: A Case ReportDocument4 pagesCompound Odontoma Associated With Impacted Teeth: A Case ReportayuandraniNo ratings yet

- VanderwoudesyndromeDocument3 pagesVanderwoudesyndromeDrSharan AnatomistNo ratings yet

- Molar Incisor Hypomineralization: A Literature ReviewDocument6 pagesMolar Incisor Hypomineralization: A Literature ReviewAngie Figueroa OtaloraNo ratings yet

- Article-Etiology Enamel DefectsDocument10 pagesArticle-Etiology Enamel DefectsSteph Vázquez SuárezNo ratings yet

- Amelogenesis Imperfecta: Review of Diagnostic Findings and Treatment ConceptsDocument12 pagesAmelogenesis Imperfecta: Review of Diagnostic Findings and Treatment ConceptsBruno M. StrangioNo ratings yet

- Oral Manifestations of Systemic Disease: Autoimmune DiseasesDocument7 pagesOral Manifestations of Systemic Disease: Autoimmune DiseaseshussainNo ratings yet

- 506 - 07 Carmen SavinDocument4 pages506 - 07 Carmen SavinGabriel RotarNo ratings yet

- 82984-Article Text-200031-1-10-20121112Document3 pages82984-Article Text-200031-1-10-20121112Yusuf DiansyahNo ratings yet

- Hypomin or HypoplasiaDocument4 pagesHypomin or HypoplasiababukanchaNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis of Tooth Agenesis in Childhood and RiskDocument7 pagesDiagnosis of Tooth Agenesis in Childhood and RiskIndah VitasariNo ratings yet

- 06 2021 Anomalias-DentalesDocument4 pages06 2021 Anomalias-DentalesAnahomiNo ratings yet

- Effect of Adhesive Pretreatments On Marginal Sealing of Aged Nano-Ionomer RestorationsDocument7 pagesEffect of Adhesive Pretreatments On Marginal Sealing of Aged Nano-Ionomer RestorationsBoris ChapelletNo ratings yet

- ContentServer PDFDocument3 pagesContentServer PDFBoris ChapelletNo ratings yet

- 44 FullDocument8 pages44 FullBoris ChapelletNo ratings yet

- Caries Management by Risk Assessment: The Caries Balance/imbalance ModelDocument11 pagesCaries Management by Risk Assessment: The Caries Balance/imbalance ModelBoris ChapelletNo ratings yet

- 1331 FullDocument8 pages1331 FullBoris ChapelletNo ratings yet

- Caries Management by Risk Assessment: The Caries Balance " Disclosure "Document26 pagesCaries Management by Risk Assessment: The Caries Balance " Disclosure "Boris ChapelletNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0278239111005672 MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S0278239111005672 MainBoris ChapelletNo ratings yet

- Current State of Dental AutotransplantationDocument5 pagesCurrent State of Dental AutotransplantationBoris ChapelletNo ratings yet

- Caries Management by Risk Assessment: The Caries Balance/imbalance ModelDocument11 pagesCaries Management by Risk Assessment: The Caries Balance/imbalance ModelBoris ChapelletNo ratings yet

- 8!!!!!!!Document13 pages8!!!!!!!anamelgarNo ratings yet

- Think Before You Extract - A Case of Tooth AutotransplantationDocument5 pagesThink Before You Extract - A Case of Tooth AutotransplantationBoris ChapelletNo ratings yet

- YOSHINO Et Al-2012-Journal of Oral RehabilitationDocument7 pagesYOSHINO Et Al-2012-Journal of Oral RehabilitationBoris ChapelletNo ratings yet

- Survival and Success Rates of Autotransplanted Premolars: A Prospective Study of The Protocol For Developing TeethDocument9 pagesSurvival and Success Rates of Autotransplanted Premolars: A Prospective Study of The Protocol For Developing TeethBoris ChapelletNo ratings yet

- Reactions of Substituted Benzenes: 6 Edition Paula Yurkanis BruiceDocument72 pagesReactions of Substituted Benzenes: 6 Edition Paula Yurkanis BruiceyulliarperezNo ratings yet

- 1964 Plymouth Barracuda Landau (Factory Prototype W/ Targa Top) - Photos & CorrespondenceDocument12 pages1964 Plymouth Barracuda Landau (Factory Prototype W/ Targa Top) - Photos & CorrespondenceJoseph GarzaNo ratings yet

- Presidential Decree No. 1616 establishes Intramuros AdministrationDocument22 pagesPresidential Decree No. 1616 establishes Intramuros AdministrationRemiel Joseph Garniel BataoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 17Document48 pagesChapter 17MahmoudKhedrNo ratings yet

- I PU Assignment 2023-24 For WorkshopDocument12 pagesI PU Assignment 2023-24 For Workshopfaruff111100% (1)

- Replacing The Volvo Oil Trap and Oil Pan SumpDocument6 pagesReplacing The Volvo Oil Trap and Oil Pan SumpsaifrulNo ratings yet

- Topic 1 - Textile Finishing - 2020 PDFDocument11 pagesTopic 1 - Textile Finishing - 2020 PDFSadaf SweetNo ratings yet

- PI734DDocument8 pagesPI734Deng_hopaNo ratings yet

- UL Anatomy 2022Document4 pagesUL Anatomy 2022jhom smithNo ratings yet

- Relative Density and Load Capacity of SandsDocument14 pagesRelative Density and Load Capacity of SandsgatotNo ratings yet

- Nature 1Document6 pagesNature 1Susanty SainudinNo ratings yet

- SOLAR DRYER v1Document43 pagesSOLAR DRYER v1Maria Angelica Borillo100% (1)

- VTBS 20-3DDocument1 pageVTBS 20-3Dwong keen faivNo ratings yet

- Unit 1.Pptx Autosaved 5bf659481837fDocument39 pagesUnit 1.Pptx Autosaved 5bf659481837fBernadith Manaday BabaloNo ratings yet

- Skin LesionDocument5 pagesSkin LesionDominic SohNo ratings yet

- Des 415 Research 01Document29 pagesDes 415 Research 01Just scribble me For funNo ratings yet

- MTD Big Bore Engines 78 277cc 83 357cc 90 420cc Repair Manual PDFDocument136 pagesMTD Big Bore Engines 78 277cc 83 357cc 90 420cc Repair Manual PDFGiedrius MalinauskasNo ratings yet

- Gardening Tool Identification QuizDocument3 pagesGardening Tool Identification Quizcaballes.melchor86No ratings yet

- 2004 Big Bay Dam Failure in MississippiDocument62 pages2004 Big Bay Dam Failure in MississippianaNo ratings yet

- 3 Uscg BWM VRPDocument30 pages3 Uscg BWM VRPdivinusdivinusNo ratings yet

- Ase Utra Military and Law Enforcement ProductsDocument12 pagesAse Utra Military and Law Enforcement ProductsjamesfletcherNo ratings yet

- Syngo - Via: HW Data SheetDocument4 pagesSyngo - Via: HW Data SheetCeoĐứcTrườngNo ratings yet

- Forward Blocking ModeDocument10 pagesForward Blocking ModeSmithi SureshanNo ratings yet

- Life Saving Appliance: Personal Life-Saving Appliances Lifeboats & Rescue Boats LiferaftsDocument18 pagesLife Saving Appliance: Personal Life-Saving Appliances Lifeboats & Rescue Boats Liferaftsdafa dzaky100% (1)