Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Greenberg 2007

Uploaded by

Rodrigo Aguirre BáezOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Greenberg 2007

Uploaded by

Rodrigo Aguirre BáezCopyright:

Available Formats

How To

try this By Sherry A. Greenberg, MSN, APRN,BC, GNP

2.5 HOURS

Continuing Education

The Geriatric Depression

Scale: Short Form

Depression in older adults is underdiagnosed; try this short,

simple tool to screen for depression.

Ed Eckstein

60 AJN ▼ October 2007 ▼ Vol. 107, No. 10 http://www.nursingcenter.com

read it watch it try it

Overview: Depression is underrecognized

Web Video

in older adults, especially those with chronic

Watch a video demonstrating the use and inter-

conditions such as heart disease and arthri- pretation of the Geriatric Depression Scale: Short

tis. Left untreated, depression may progress Form at http://links.lww.com/A101.

and have dramatic effects on overall health.

The Geriatric Depression Scale: Short Form A Closer Look

is a 15- question screening tool for depres- Get more information about depression in

sion in older adults that takes five to seven and assessment of older adults.

minutes to complete and can be filled out by

the patient or administered by a provider Try This: The Geriatric

with minimal training in its use. The ques- Depression Scale

tions focus on mood; the score can help cli- This is the Try This tool in its original form.

nicians decide whether further assessment is See page 67.

needed. (This screening tool is included in

a series, Try This: Best Practices in Nursing Online Only

Care to Older Adults, from the Hartford Unique online material is available for this

Institute for Geriatric Nursing at New York article. Direct URL citations appear in the

printed text; simply type the URL into any

University’s College of Nursing.) For a free

Web browser.

online video demonstrating the use of this

tool, go to http://links.lww.com/A101.

harlotte Balzan, a 78-year-old woman gown, little food in the refrigerator, some canned

C living in a two-bedroom apartment in

New York City, has felt lonely for the

past two years, since the death of her hus-

band of 45 years. (This case is a compos-

ite, based on my experience.) She has one son who

lives in Maryland, whom she speaks with weekly but

rarely sees. Ms. Balzan has no close friends and isn’t

goods in the cabinets, and several piles of dirty

laundry. Ms. Balzan appears apathetic. She says

that she sleeps poorly, is fatigued, and has little

appetite. Upon examination, Ms. Balzan is afebrile,

her vital signs are stable, and her blood pressure is

well controlled. The nurse finds no evidence of

acute illness. Recent routine laboratory tests

active in the nearby senior center, nor does she par- showed nothing abnormal.

ticipate in other activities. Recently diagnosed with The home care nurse completes a routine

hypertension and treated with hydrochlorothiazide Outcome and Assessment Information Set (OASIS)

(HydroDIURIL and others) 12.5 mg once daily, she assessment, which includes checking reported or

has been visited by a home care nurse twice weekly observed depressive symptoms, including depressed

for blood pressure monitoring and medication- mood, sense of failure or self-reproach, hopeless-

adherence assessment. On these visits Ms. Balzan ness, recurrent thoughts of death, or thoughts of sui-

says she has “nothing to do” and bemoans what cide.1 Ms. Balzan says she has none of these. But the

she sees as the poor condition of her apartment, nurse observes a flat affect, and because of this,

which is clean but cluttered with newspapers and along with the nonspecific nature of the complaints

has old plumbing, heating, and air-conditioning and her disinterest in activities, the nurse suspects

systems. She doesn’t want to move or have her apart- depression. Because the OASIS, which one study has

ment cleaned. She has no known history of depres- suggested may fail to identify depression in many

sion or other psychological disorders. people,2 is a checklist and doesn’t include detailed

When the home care nurse visits one early after- questions on mood, the nurse decides to administer

noon, she finds Ms. Balzan still wearing her night- the Geriatric Depression Scale: Short Form (GDS: SF),

ajn@wolterskluwer.com AJN ▼ October 2007 ▼ Vol. 107, No. 10 61

How To

try this

which is designed specifically to assess for depressed speak slowly and clearly, maintain good eye contact,

mood in older adults. and tell the patient that these are routine questions.

If necessary, an interpreter should administer the

THE GERIATRIC DEPRESSION SCALE: SHORT FORM questionnaire in the patient’s language. To view

Developed in 1986 to screen for depression in older “Demonstrating the GDS: SF Screening,” the online

adults, the GDS: SF has been used in community, video segment showing a nurse administering the

acute, and long-term care settings. The GDS: SF GDS: SF in an assisted-living facility, go to http://

consists of 15 questions requiring “yes” or “no” links.lww.com/A102.

answers and can be completed quickly (see the tool Challenges that may arise. When patients offer

on page 67). Although the tool itself states that detailed explanations rather than “yes” or “no”

a score above 5 is suggestive of depression and a answers, nod politely, and repeat the directions: “We

score equal to or greater than 10 is almost always can talk more about this later, please answer either

indicative of depression, a more detailed scoring is ‘yes’ or ‘no’ based on how you have felt over the past

often more helpful in rating depression. A score of week.” If patients respond with “I don’t know” to

• 0 to 4 isn’t typically cause for concern. any of the questions, as often occurs with depressed

• 5 to 8 suggests mild depression. patients, redirect them by saying, for example,

• 9 to 11 suggests moderate depression. “Overall, would you say more ‘yes’ or more ‘no’

• 12 to 15 suggests severe depression. based on how you’ve felt over the past week?” and

All GDS: SF questions relate to mood, rather than then repeat the question. It’s often helpful to ask fam-

the physical symptoms frequently reported by older ily members or friends to wait outside the room so

adults. It was modified from the original 30-item you can ask the questions in private. This prevents

form to focus on items with the highest correlation to others from answering for the patient or influencing

depressive symptoms in validation studies.3 It’s shorter the answers. Patients often feel more able to state feel-

than other assessment tools for depression in this ings if family members and friends are not present.

population and requires little training to administer. Patients who neither speak nor write may point to

The GDS: SF is useful in assessing older adults the words “yes” or “no” written on paper or a board

who are ill or well; are easily fatigued; have a short to respond. Those with even mild dementia may not

attention span; or have mild to moderate, though fully understand the questions, and Burke and col-

not severe, cognitive impairment. It can be com- leagues found that the GDS: SF has poor validity as a

pleted in less than seven minutes. Older adults may screening tool in this population.17 In such cases, it’s

have an easier time providing the GDS: SF’s yes-or- possible to use a version of the GDS: SF in which fam-

no responses than choosing answers, as is required ily members or caregivers answer the 15 questions

on other depression screening tools. Two other ben- for the patient. That version is available in English

efits of both the long and short forms are that the and Spanish at www.stanford.edu/~yesavage/GDS_

GDS is in the public domain and has been trans- INFORMANT_MEASURES.htm.

lated into many languages.

For detailed definitions of depression in older SCORING AND INTERPRETING RESULTS

adults, see Why Screen for Depression? on page 63. For the purposes of scoring, answer in each of the 15

questions on the GDS: SF is in bold type to emphasize

its significance to depression and to assist the clinician

ADMINISTERING THE GDS: SF in scoring the items. As can be seen on page 68, 10 of

The GDS: SF may be used in any setting—acute the “yes” responses and five of the “no” responses

care, primary care, home care, assisted living, or are bold. The higher the total number of bold

long-term care. It can be completed by the patient responses, the greater the likelihood that a patient

before a clinical visit or during a provider interview, requires further assessment for depression. If the

in person or by telephone.15, 16 If a patient cannot patient is providing written rather than oral

read because of illiteracy or low vision, the GDS: SF responses, give her or him a printed form that con-

should be administered by interview. tains no responses in bold, which could influence

Introduce the tool and instruct patients by saying, their choice of answers. (Such a form can be found

for example, “I’m going to ask you some questions at www.stanford.edu/~yesavage/GDS.english.short.

about your mood. Please answer ‘yes’ or ‘no’ based html.) For patients who don’t answer one or more

on how you have felt over the past week.” The GDS: items, the score may be prorated. For example, if the

SF should be administered in a private, quiet room patient answers 12 of the 15 items, four of these with

when the clinician is not rushed. The provider should bolded responses, the patient’s total score will be 4

62 AJN ▼ October 2007 ▼ Vol. 107, No. 10 http://www.nursingcenter.com

Why Screen for Depression?

epression may be broadly defined as a mood dis- depressed mood or diminished pleasure or interest in

D order that has affective, cognitive, and physical

signs and symptoms.4 Symptoms range from mild to

activities. Older adults with depressive symptoms that do

not meet DSM-IV-TR criteria for major or minor depres-

severe and may progress with time; marking the sion are considered to have subsyndromal depression.

most severe form are suicidal ideation, psychotic fea- Since they don’t meet DSM-IV-TR criteria, they often don’t

tures such as hallucinations and delusions, and exces- receive treatment.6 Both minor and subsyndromal

sive somatic complaints.4 Depression, unlike seasonal depression, if left untreated, may increase the risk of

affective disorder or moderate bereavement, usually physical, cognitive, and social impairment, as well as

doesn’t resolve on its own and may persist or progress delayed recovery from acute illness and surgery, and

if left untreated. may lead to major depression, more frequent and costly

Depression is classified as minor or major. The use of health care services, poorer physical and social

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, functioning, and a poorer quality of life.7, 8

fourth edition, text revision (DSM-IV-TR), lists the follow- Incidence and prevalence. One metaanalysis found

ing criteria for the diagnosis of “major depressive “clinically significant depressive symptoms” reported in

episode” (the primary criterion in the diagnosis of 3% to 26% of community-dwelling older adults, 10%

major depressive disorder)5: of older medical outpatients, 23% of older acute care

• persistently depressed mood patients, and 16% to 30% of older nursing home resi-

• diminished ability to take pleasure in activities dents.9 The prevalence of depression in patients with

• feelings of worthlessness or excessive guilt Alzheimer disease is 23% to 55%,10 and one study

• difficulty thinking and concentrating; indecisive- found that patients with arthritis or heart disease are

ness 18% more likely to experience depression, with func-

• thoughts of death, suicidal ideation, suicide tional limitation as the strongest factor associated with

attempts depression.11 In older adults, somatic symptoms such

• excessive tiredness as pain may mask depressive symptoms and lead to

• significantly altered appetite and weight underdiagnosis of depression, a disorder that is often

• too much or too little sleep treatable.

• psychomotor agitation or retardation Depression is a leading risk factor for suicide. In

For an episode to meet the criteria, the symptoms 2004 people ages 65 and older constituted 12% of the

shouldn’t be the direct result of a drug or a medical con- U.S. population but accounted for 16% of suicides.12 In

dition, and at least five of the nine criteria must be pres- 2004, 14.3 of every 100,000 people ages 65 and

ent almost daily for two weeks or longer and involve older died by suicide—higher than the rate of about

”clinically significant distress or impairment in social, 11 per 100,000 in the general population.12, 13 Non-

occupational, or other important areas of functioning.”5 Hispanic white men ages 85 and older were the sub-

At least one of the symptoms must be depressed mood group most likely to die by suicide, with a disturbingly

or diminished pleasure or interest in activities. high rate of 50 suicides per 100,000 in that age

The DSM-IV-TR criteria for the diagnosis of “minor group.12 And a 2004 study by Juurlink and colleagues

depressive disorder” includes depressive episodes of at found that older adults who died by suicide “were almost

least two weeks’ duration, with the patient meeting twice as likely to have visited a physician in the week

fewer than five but at least two of the criteria required before death” than were living control subjects.14 To view

for major depressive disorder. As with major depressive the online video segment “Recognizing Geriatric

disorder, at least one of the symptoms present must be Depression,” go to http://links.lww.com/A103.

plus one-third of the three unanswered questions— The GDS: SF helps to quantify and validate the

that is, 4 plus 1, making a total score of 5.18 Any nurse’s suspicions and concerns about depression. A

score higher than 5 warrants a comprehensive assess- comprehensive assessment involves input from oth-

ment and, if indicated, evaluation for suicidality. ers, including such specialists as a geriatrician, geri-

Although the GDS: SF is a useful tool in screening for atric nurse, geriatric social worker, geriatric

depression in older adults, it’s not diagnostic and not psychiatrist, pharmacist, and dietitian. The video

a substitute for clinical observation and judgment. segment discussing scoring, “The Interpretation of

ajn@wolterskluwer.com AJN ▼ October 2007 ▼ Vol. 107, No. 10 63

How To

try this

the GDS: SF,” is available online at http://links.lww. suggest a need for depression screening with older

com/A104. immigrant populations in this country.

Ms. Balzan’s GDS: SF score was 8 of 15. Her Translations of the GDS: SF are in the public

responses receiving one point each included not feel- domain and available in various languages, including

ing satisfied with her life, dropping many activities Spanish, Chinese, French, and Korean (among oth-

and interests, feeling that her life was empty, feeling ers), and can be downloaded for free from the Web

bored, not being in good spirits most of the time, site of the Aging Clinical Research Center of Stanford

not feeling happy most of the time, preferring to University and the Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health

stay home rather than to go out and do new things, Care System, www.stanford.edu/~yesavage/GDS.

and not feeling full of energy. Taking into account html. A literature search finds no studies of validity

not only her score but also her apathy, her poor self- and reliability for the GDS: SF in translation (scor-

care (in bathing and doing laundry), the paucity of ing of all versions is the same). It’s important to bear

food in the apartment, and her poor appetite, the in mind the significant cultural differences in how

nurse decided it would be wise to call Ms. Balzan’s people express emotion.20, 22 More cross-cultural

primary care provider, an NP. research is needed.

CULTURAL CONSIDERATIONS COMMUNICATING THE RESULTS

The concept of depression may vary by culture. For The GDS: SF score and responses along with related

example, in a small study of 50 elderly African symptoms from the patient’s history need to be doc-

American outpatients at a large urban hospital, umented in the chart and shared with the other care

many said that they didn’t understand questions providers. Nurses may be the only ones who’ve had

such as Do you feel that your situation is hopeless? repeated contact with a patient, and important

and Do you feel pretty worthless the way you are information must be communicated to other staff

now?19 The authors speculate that culture and reli- members. When describing the patient to other

gion can affect the meaning of worthlessness and providers, include information related to the

hopelessness, although the patients’ level of educa- patient’s self-care, recent changes in health, somatic

tion didn’t significantly affect their understanding of complaints, medications, personal losses, weight

the questions. The study highlights the need for changes, sleep patterns, activity level, substance

larger studies that examine other populations’ use or abuse, and suicidal ideation. An interdisci-

responses to these questions. plinary approach is best; older adults often have

One study notes that older adults living in Korea interconnected physical, psychiatric, functional,

and those in the United States hold very different con- social, and financial issues. The video segment dis-

cepts of depression.20 In Korea, for example, older cussing communicating results, “The Communica-

adults tend to live with their families. When asked, tion and Utilization of Findings,” is available online

“Do you prefer to stay at home, rather than going out at http://links.lww.com/A105.

and doing new things?” a positive response may not When discussing results with patients and fami-

indicate depression as much as it would in an older lies, remember that the GDS: SF is a screening tool,

adult in the United States. According to the authors, not a diagnostic tool. Results give a basis for discus-

“Korean elderly [patients] who are suffering with sion; make sure that patients and families know that

depressive symptoms may choose going out as one of a comprehensive assessment—by a psychiatric

the coping strategies to escape their depressive moods nurse, NP, geriatrician, or geropsychiatrist—is

. . . especially when the main cause of their depressive needed to diagnose depression. The GDS: SF may be

symptoms is related to family matters.” Despite such repeated as needed to screen for or to monitor the

differences, the authors found their own Korean severity of depression over time. The GDS: SF does

translation of the GDS: SF to be a reliable measure not contain a question related to suicidal ideation

for use with older Koreans. and may be a poor predictor of suicidality.23 If a

A study using a regional probability study sam- provider suspects that a patient may harm her- or

ple of elderly Asian immigrants living in New York himself, a detailed assessment for suicidal ideation

City showed that the long and short forms of the should be performed and a plan of care developed. If

GDS were reliable in assessing depression in that a patient is suicidal, with or without a detailed plan,

population.21 Using the long form, the researchers the patient should not be left alone and help should

found that 40% of 407 elderly immigrants from be sought immediately. The toll-free National

India, China, Vietnam, Japan, and the Philippines Suicide Prevention Lifeline is available 24 hours a

screened positive for depression. Such data strongly day, seven days a week: (800) 273-TALK (8255).

64 AJN ▼ October 2007 ▼ Vol. 107, No. 10 http://www.nursingcenter.com

Watch It!

o to http//links.lww.com/A101 to

G watch a nurse use the GDS: SF to screen

an older woman for depression and discuss

Ms. Balzan, continued. The nurse discussed the

findings with the patient: “Ms. Balzan, your ways to meet the challenges of administering

answers to these questions lead me to think that it and interpreting and quickly acting on find-

maybe you’re depressed. Your primary care ings. Then watch the health care team plan

provider should know so that she can do a more short- and long-term interventions to alleviate

thorough assessment. With your permission I’d like the woman’s depression.

to talk with her about this.” Ms. Balzan allowed View this video in its entirety and then

the nurse to call from her apartment (although she apply for CE credit at www.nursingcenter.

didn’t have to approve the call; the nurse had suffi- com/AJNolderadults; click on the How to

cient reason for concern). The nurse reported to Try This series. All videos are free and in a

Ms. Balzan’s NP, “I am currently visiting Charlotte downloadable format (not streaming video)

Balzan. Though her vital signs are stable and her that requires Windows Media Player.

blood pressure is well controlled, I’m concerned

about her mood. She’s still wearing her nightgown,

has little food available, and hasn’t bathed in a CONSIDER THIS

while. And there are several piles of dirty laundry in There are other screening and assessment tools for

the apartment. She appears apathetic, says that she depression, but the GDS: SF stands out as the best

sleeps poorly, and complains of fatigue and little tool to use with older adults. (Go to http://links.lww.

appetite. Thinking she might be depressed, I com- com/A117 for a comparison of the GDS: SF with

pleted a GDS: SF; her score is 8 out of 15. She’s not other tools used to screen for depression.) The fol-

feeling satisfied with her life, is dropping many lowing questions and answers provide additional

activities and interests, feels that her life is empty, insight into the use of this tool.

feels bored, isn’t in good spirits most of the time, What is the evidence for using the GDS: SF?

isn’t feeling happy most of the time, prefers to stay According to the original study on the GDS: SF, the

home rather than go out and do new things, and tool was moderately reliable and valid as a screen-

isn’t feeling full of energy. I was hoping you could ing tool for depression in older adults.3 For a more

fit her into your home visit schedule today.” in-depth discussion of psychometrics, see “Define

When Ms. Balzan’s NP saw her later that day, Your Terms,” by series coeditor Nancy Stotts and

she obtained a thorough history and performed a Katherine Alderich, page 71.

physical examination and in-depth psychological • Reliability. The GDS: SF has demonstrated

assessment. The NP told Ms. Balzan that she would moderate reliability. In one study of 960 func-

benefit from an inpatient stay on a geropsychiatry tionally impaired, cognitively intact primary

unit, where she would be assessed and treated for care patients ages 65 and older, Friedman and

depression by a team of providers. Ms. Balzan con- colleagues reported moderate internal consis-

sented and was admitted to a nearby private hospi- tency (a Cronbach a coefficient of 0.749).23 The

tal where her NP could follow her along with a functional status of the older adult did not sig-

geropsychiatrist and other team members on the nificantly affect the reliability.

inpatient unit. There, Ms. Balzan was treated for • Validity. In this same study by Friedman and col-

major depression with group and individual ther- leagues, the GDS has moderate correlations with

apy, as well as an antidepressant. measures of depressed mood and life satisfac-

After the inpatient stay, Ms. Balzan moved into tion.23 For criterion validity:

an assisted-living facility near her son. Outpatient ❍ Sensitivity. The original research established

therapy was arranged for ongoing evaluation of that the GDS: SF could identify 92% of the

depression, adverse effects of the antidepressant, people who were actually depressed.3 The

and adjustment to the move. Ms. Balzan sold her study by Friedman and colleagues found that

apartment to finance the move. When her home the sensitivity increased with a lower cutoff

health care nurse called to follow up, Ms. Balzan score: it was 81.45% with a cutoff score of 6

still spoke of boredom, sleepiness, and loneliness, and 89.5% with a cutoff score of 5.23

but she said that she ate meals in the dining room ❍ Specificity. The tool accurately identified 89%

with others at the facility, participated in scheduled of those who were not depressed in the origi-

activities, and had lunch regularly with her son. nal study.3 The study by Friedman and col-

Ms. Balzan recognized that she was no longer able leagues found that this varies with the cutoff

to handle the upkeep on her apartment; she was score: it was 75.36% with a cutoff score of 6

grateful, she said, to live with others her age. and 65.3% with a cutoff score of 5.23

ajn@wolterskluwer.com AJN ▼ October 2007 ▼ Vol. 107, No. 10 65

How To

try this

tion,26 the quality of life,27 caregiver well-being,28 and

cognition.29 But depression in patients with Parkinson

Online Resources disease may be underrecognized and too rarely

treated.30, 31 Because the GDS: SF is a brief instrument

For more information on the GDS: SF and other geriatric and can be self-administered, it’s useful for distin-

assessment tools and best practices, go to www.hartfordign. guishing depressed from nondepressed older adults in

org, the Web site of the John A. Hartford Foundation–funded this population.

Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing at New York University What about its use with patients with Alzheimer

College of Nursing. The institute focuses on improving the disease or other conditions? Limited work has been

quality of care provided to older adults by promoting excel- done on using the GDS: SF in screening for depres-

lence in geriatric nursing practice, education, research, and sion in older adults with Alzheimer disease, chronic

policy. Download the original Try This document on the GDS: pain, heart disease, diabetes, and other chronic or

SF by going to www.hartfordign.org/publications/trythis/ degenerative conditions that afflict this population

issue04.pdf. and may affect mood.

Also, Special Topics in Long-Term Care, at www.hartfordign. Now it’s your turn to try this. ▼

org/resources/special_topics/spectopics.html, includes infor-

mation relevant to the long-term care setting. This site links to Sherry A. Greenberg is a geriatric NP and a consultant at the

information on pertinent issues such as wandering and Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing, New York

elopement litigation, ethical issues related to cultural change, University (NYU) College of Nursing in New York City.

Contact author: sherry@familygreenberg.com. The author

and more. has no significant ties, financial or otherwise, to any com-

For a list of other online resources go to http://links.lww. pany that might have an interest in the publication of this

com/A118. And go to www.nursingcenter.com/ educational activity.

AJNolderadults and click on the How To Try This link to How to Try This is a three-year project funded by a grant

from the John A. Hartford Foundation to the Hartford

access all articles and videos in this series. Institute for Geriatric Nursing at NYU’s College of Nursing

in collaboration with AJN. This initiative promotes the

Hartford Institute’s geriatric assessment tools, Try This: Best

Practices in Nursing Care to Older Adults: www.hartfordign.

For more discussion of the psychometric properties org/trythis. The series will include 30 articles and corresponding

of the GDS: SF, go to http://links.lww.com/A119. videos, all of which will be available for free online at

www.nursingcenter.com/AJNolderadults. Greenberg and Nancy

Does the GDS: SF work as well in people who A. Stotts, EdD, RN, FAAN (nancy.stotts@nursing.ucsf.edu), are

are functionally impaired? A study demonstrated coeditors of the print series. The articles and videos are to be

that the reliability and validity of the tool did not used for educational purposes only.

Routine use of a Try This tool may require formal review

differ significantly when used to assess community- and approval by your employer.

dwelling older adults with either low or high func-

tional impairment.23 So nurses should be able to use REFERENCES

it with the same level of confidence with older 1. Quality Improvement and Evaluation Services. Outcome

adults with varying levels of functional capacity. and Assessment Information Set (OASIS). Oklahoma State

Has the GDS: SF been used in special populations? Department of Health. n.d. http://www.health.state.ok.us/

program/qies/oasis/index.html.

The tool’s use with adults who have Parkinson dis-

2. Brown EL, et al. Recognition of late-life depression in home

ease has been examined in several studies. One study care: accuracy of the Outcome and Assessment Information

compared the psychometric properties of the GDS: SF Set. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52(6):995-9.

and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale in 148 3. Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS):

recent evidence and development of a shorter version. In:

outpatients with Parkinson disease.24 Thirty-two sub- Brink TL, editor. Clinical gerontology: a guide to assessment

jects (22%) were diagnosed with a depressive disor- and intervention. New York: Haworth Press; 1986. p. 165-73.

der. Although the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, 4. NIH consensus conference. Diagnosis and treatment of

depression in late life. JAMA 1992;268(8):1018-24.

designed to rate the severity of symptoms in patients

5. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th

already diagnosed with depression, provided a more ed., text revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric

comprehensive evaluation of depressive symptoms, Association; 2000.

the GDS: SF identified critical symptoms of depres- 6. Lyness JM, et al. Screening for depression in elderly primary

care patients. A comparison of the Center for Epidemiologic

sion in those with Parkinson disease. Studies-Depression Scale and the Geriatric Depression Scale.

A literature review of 45 studies of depression and Arch Intern Med 1997;157(4):449-54.

Parkinson disease from 1922 through 1998 found 7. Gaynes BN, et al. Depression and health-related quality of

that 31% of people with the disease experience life. J Nerv Ment Dis 2002;190(12):799-806.

8. Lyness JM, et al. The clinical significance of subsyndromal

depression at some point.25 In older adults with depression in older primary care patients. Am J Geriatr

Parkinson disease, depression negatively affects func- Psychiatry 2007;15(3):214-23.

66 AJN ▼ October 2007 ▼ Vol. 107, No. 10 http://www.nursingcenter.com

from

Issue Number 4, Revised 2007 Series Editor: Marie Boltz, PhD, APRN, BC, GNP

Managing Editor: Sherry A. Greenberg, MSN, APRN, BC, GNP

New York University College of Nursing

The Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS)

By: Lenore Kurlowicz, PhD, RN, CS, FAAN, University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing and

Sherry A. Greenberg, MSN, APRN, BC, GNP, Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing, NYU College of Nursing

WHY: Depression is common in late life, affecting nearly 5 million of the 31 million Americans aged 65 and older. Both major and minor

depression are reported in 13% of community dwelling older adults, 24% of older medical outpatients, 30% of older acute care patients, and 43%

of nursing home dwelling older adults (Blazer, 2002a). Contrary to popular belief, depression is not a natural part of aging. Depression is often

reversible with prompt and appropriate treatment. However, if left untreated, depression may result in the onset of physical, cognitive and social

impairment, as well as delayed recovery from medical illness and surgery, increased health care utilization, and suicide.

BEST TOOL: While there are many instruments available to measure depression, the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), first created by

Yesavage, et al., has been tested and used extensively with the older population. The GDS Long Form is a brief, 30-item questionnaire in which

participants are asked to respond by answering yes or no in reference to how they felt over the past week. A Short Form GDS consisting of 15

questions was developed in 1986. Questions from the Long Form GDS which had the highest correlation with depressive symptoms in validation

studies were selected for the short version. Of the 15 items, 10 indicated the presence of depression when answered positively, while the rest

(question numbers 1, 5, 7, 11, 13) indicated depression when answered negatively. Scores of 0-4 are considered normal, depending on age,

education, and complaints; 5-8 indicate mild depression; 9-11 indicate moderate depression; and 12-15 indicate severe depression.

The Short Form is more easily used by physically ill and mildly to moderately demented patients who have short attention spans and/or feel

easily fatigued. It takes about 5 to 7 minutes to complete.

TARGET POPULATION: The GDS may be used with healthy, medically ill and mild to moderately cognitively impaired older adults. It has been

extensively used in community, acute and long-term care settings.

VALIDITY AND RELIABILITY: The GDS was found to have a 92% sensitivity and a 89% specificity when evaluated against diagnostic criteria.

The validity and reliability of the tool have been supported through both clinical practice and research. In a validation study comparing the Long

and Short Forms of the GDS for self-rating of symptoms of depression, both were successful in differentiating depressed from non-depressed

adults with a high correlation (r = .84, p < .001) (Sheikh & Yesavage, 1986).

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS: The GDS is not a substitute for a diagnostic interview by mental health professionals. It is a useful

screening tool in the clinical setting to facilitate assessment of depression in older adults especially when baseline measurements are compared

to subsequent scores. It does not assess for suicidality.

FOLLOW-UP: The presence of depression warrants prompt intervention and treatment. The GDS may be used to monitor depression over time

in all clinical settings. Any positive score above 5 on the GDS Short Form should prompt an in-depth psychological assessment and evaluation

for suicidality.

MORE ON THE TOPIC:

Best practice information on care of older adults: www.ConsultGeriRN.org.

The Stanford/VA/NIA Aging Clinical Resource Center (ACRC) website. Retrieved Jan 9, 2007, from http://www.stanford.edu/~yesavage/ACRC.html.

Information on the GDS. Retrieved Jan 9, 2007, from http://www.stanford.edu/~yesavage/GDS.html

Blazer, D.G. (2002a). Depression in late life (3rd ed.). St. Louis: Mosby Year Book.

Koenig, H.G., Meador, K.G., Cohen, J.J., & Blazer, D.G. (1988). Self-rated depression scales and screening for major depression in the older

hospitalized patient with medical illness. JAGS, 36, 699-706.

Kurlowicz, L.H., & NICHE Faculty. (1997). Nursing stand or practice protocol: Depression in elderly patients. Geriatric Nursing, 18(5), 192-199.

NIH Consensus Development Panel. (1992). Diagnosis and treatment of depression in late life. JAMA, 268, 1018-1024.

Sheikh, J.I., & Yesavage, J.A. (1986). Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS). Recent evidence and development of a shorter version. In T.L. Brink (Ed.),

Clinical Gerontology: A Guide to Assessment and Intervention (pp. 165-173). NY: The Haworth Press, Inc.

Yesavage, J.A., Brink, T.L., Rose, T.L., Lum, O., Huang, V., Adey, M.B., & Leirer, V.O. (1983). Development and validation of a geriatric depression

screening scale: A preliminary report. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 17, 37-49.

Permission is hereby granted to reproduce, post, download, and/or distribute, this material in its entirety only for not-for-profit educational purposes only, provided that

The Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing, College of Nursing, New York University is cited as the source. This material may be downloaded and/or distributed in electronic

format, including PDA format. Available on the internet at www.hartfordign.org and/or www.ConsultGeriRN.org. E-mail notification of usage to: hartford.ign@nyu.edu.

ajn@wolterskluwer.com AJN ▼ October 2007 ▼ Vol. 107, No. 10 67

✁

Geriatric Depression Scale: Short Form

Choose the best answer for how you have felt over the past week:

1. Are you basically satisfied with your life? YES / NO

2. Have you dropped many of your activities and interests? YES / NO

3. Do you feel that your life is empty? YES / NO

4. Do you often get bored? YES / NO

5. Are you in good spirits most of the time? YES / NO

6. Are you afraid that something bad is going to happen to you? YES / NO

7. Do you feel happy most of the time? YES / NO

8. Do you often feel helpless? YES / NO

9. Do you prefer to stay at home, rather than going out and doing new things? YES / NO

10. Do you feel you have more problems with memory than most? YES / NO

11. Do you think it is wonderful to be alive now? YES / NO

12. Do you feel pretty worthless the way you are now? YES / NO

13. Do you feel full of energy? YES / NO

14. Do you feel that your situation is hopeless? YES / NO

15. Do you think that most people are better off than you are? YES / NO

Answers in bold indicate depression. Score 1 point for each bolded answer.

A score > 5 points is suggestive of depression.

A score > 10 points is almost always indicative of depression.

A score > 5 points should warrant a follow-up comprehensive assessment.

Source: http://www.stanford.edu/~yesavage/GDS.html

A SERIES PROVIDED BY

The Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing

EMAIL : hartford.ign@nyu.edu

HARTFORD INSTITUTE WEBSITE : www.hartfordign.org

CONSULTGERIRN WEBSITE : www.ConsultGeriRN.org

✃

68 AJN ▼ October 2007 ▼ Vol. 107, No. 10 http://www.nursingcenter.com

9. Hybels CF, Blazer DG. Epidemiology of late-life mental dis-

orders. Clin Geriatr Med 2003;19(4):663-96.

10. Zubenko GS, et al. A collaborative study of the emergence

and clinical features of the major depressive syndrome of

2.5 HOURS

Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160(5):857-66.

Continuing Education

11. Dunlop DD, et al. Arthritis and heart disease as risk factors EARN CE CREDIT ONLINE

Go to www.nursingcenter.com/CE/ajn and receive a certificate within minutes.

for major depression: the role of functional limitation. Med

Care 2004;42(6):502-11.

12. Older Adults: depression and suicide facts. Rockville, MD:

National Institute of Mental Health; 2007 Apr. NIH publi- GENERAL PURPOSES: To provide registered professional

cation no. 4593. http://www.nimh.nih.gov/publicat/ nurses with current information on depression in older

elderlydepsuicide.cfm. adults, highlighting the use of the Geriatric Depression

13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Suicide: fact Scale: Short Form (GDS: SF) as a screening tool.

sheet. 2007. http://www.cdc.gov/ncipc/factsheets/suifacts.htm. LEARNING OBJECTIVES: After reading this article and taking

14. Juurlink DN, et al. Medical illness and the risk of suicide in the test on the next page, you will be able to

the elderly. Arch Intern Med 2004;164(11):1179-84. • discuss depression among older adults, including

15. Burke WJ, et al. The reliability and validity of the Geriatric classification and prevalence.

Depression Rating Scale administered by telephone. J Am • outline the general use of the GDS: SF.

Geriatr Soc 1995;43(6):674-9. • list the advantages and disadvantages of using the

16. Carrete P, et al. Validation of a telephone-administered GDS: SF.

Geriatric Depression Scale in a Hispanic elderly population.

J Gen Intern Med 2001;16(7):446-50. TEST INSTRUCTIONS

17. Burke WJ, et al. The short form of the Geriatric Depression To take the test online, go to our secure Web site at www.

Scale: a comparison with the 30-item form. J Geriatr nursingcenter.com/CE/ajn.

Psychiatry Neurol 1991;4(3):173-8.

To use the form provided in this issue,

18. Yesavage JA. Geriatric Depression Scale. Stanford/VA/NIA • record your answers in the test answer section of the CE

Aging Clinical Research Center. n.d. http://www.stanford.edu/ enrollment form between pages 56 and 57. Each ques-

~yesavage/GDS.html.

tion has only one correct answer. You may make copies

19. Flacker JM, Spiro L. Does question comprehension limit the of the form.

utility of the Geriatric Depression Scale in older African • complete the registration information and course evalua-

Americans? J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51(10):1511-2. tion. Mail the completed enrollment form and registration

20. Jang Y, et al. Cross-cultural comparability of the Geriatric fee of $22.95 to Lippincott Williams and Wilkins CE

Depression Scale: comparison between older Koreans and Group, 2710 Yorktowne Blvd., Brick, NJ 08723, by

older Americans. Aging Ment Health 2001;5(1):31-7. October 31, 2009. You will receive your certificate in four

21. Mui AC, et al. Reliability of the Geriatric Depression Scale to six weeks. For faster service, include a fax number and

for use among elderly Asian immigrants in the USA. Int we will fax your certificate within two business days of

Psychogeriatr 2003;15(3):253-71. receiving your enrollment form. You will receive your CE

22. Jang Y, et al. Acculturation and manifestation of depressive certificate of earned contact hours and an answer key to

symptoms among Korean-American older adults. Aging review your results. There is no minimum passing grade.

Ment Health 2005;9(6):500-7.

23. Friedman B, et al. Psychometric properties of the 15-item DISCOUNTS and CUSTOMER SERVICE

Geriatric Depression Scale in functionally impaired, cogni- • Send two or more tests in any nursing journal published by

tively intact, community-dwelling elderly primary care Lippincott Williams and Wilkins (LWW) together, and

patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53(9):1570-6. deduct $0.95 from the price of each test.

24. Weintraub D, et al. Test characteristics of the 15-item Geriatric • We also offer CE accounts for hospitals and other health

Depression Scale and Hamilton Depression Rating Scale in care facilities online at www.nursingcenter.com. Call

Parkinson disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2006;14(2):169-75. (800) 787-8985 for details.

25. Slaughter JR, et al. Prevalence, clinical manifestations, etiol- PROVIDER ACCREDITATION

ogy, and treatment of depression in Parkinson’s disease. J LWW, publisher of AJN, will award 2.5 contact hours

Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2001;13(2):187-96. for this continuing nursing education activity.

26. Weintraub D, et al. Effect of psychiatric and other nonmotor LWW is accredited as a provider of continuing nursing

symptoms on disability in Parkinson’s disease. J Am Geriatr education by the American Nurses Credentialing Center’s

Soc 2004;52(5):784-8. Commission on Accreditation.

27. Schrag A, et al. What contributes to quality of life in patients LWW is also an approved provider of continuing nurs-

with Parkinson’s disease? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry ing education by the American Association of Critical-

2000;69(3):308-12. Care Nurses #00012278 (CERP category A), District of

28. Aarsland D, et al. Predictors of nursing home placement in Columbia, Florida #FBN2454, and Iowa #75. LWW

Parkinson’s disease: a population-based, prospective study. J home study activities are classified for Texas nursing con-

Am Geriatr Soc 2000;48(8):938-42. tinuing education requirements as Type 1. This activity

29. Starkstein SE, et al. A prospective longitudinal study of is also provider approved by the California Board of

depression, cognitive decline, and physical impairments in Registered Nursing, provider number CEP 11749, for

patients with Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg 2.5 contact hours.

Psychiatry 1992;55(5):377-82. Your certificate is valid in all states.

30. Shulman LM, et al. Non-recognition of depression and other

non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism TEST CODE: AJNTT02

Relat Disord 2002;8(3):193-7.

31. Weintraub D, et al. Recognition and treatment of depression

in Parkinson’s disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2003;

16(3):178-83.

ajn@wolterskluwer.com AJN ▼ October 2007 ▼ Vol. 107, No. 10 69

You might also like

- Journeys Through ADDulthood: Discover a New Sense of Identity and Meaning with Attention Deficit DisorderFrom EverandJourneys Through ADDulthood: Discover a New Sense of Identity and Meaning with Attention Deficit DisorderRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (13)

- Goldberg Depression Test ScoresDocument3 pagesGoldberg Depression Test ScoresBrittanyNo ratings yet

- ADHD: Inside the Distracted Mind - The Brain Trap of the DMN & TPN - A Life-Changing Guide to Turning Neurodiversity Into a Gift & Thriving With ADHD From Disorganized Children to Successful Adults: Master Your MindFrom EverandADHD: Inside the Distracted Mind - The Brain Trap of the DMN & TPN - A Life-Changing Guide to Turning Neurodiversity Into a Gift & Thriving With ADHD From Disorganized Children to Successful Adults: Master Your MindRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (8)

- Adhd Diva - 5Document20 pagesAdhd Diva - 5quaz486% (14)

- The Get to the Point! Guide to Beating DepressionFrom EverandThe Get to the Point! Guide to Beating DepressionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- A Parentsmedguide PDFDocument15 pagesA Parentsmedguide PDFMikitaTorresNo ratings yet

- Men with Adult ADHD: How to Raise Emotionally Intelligent Men and Improve RelationshipsFrom EverandMen with Adult ADHD: How to Raise Emotionally Intelligent Men and Improve RelationshipsNo ratings yet

- Peripartum Depression - Does It Occur in Fathers and Does It Matter?Document11 pagesPeripartum Depression - Does It Occur in Fathers and Does It Matter?Ionela BogdanNo ratings yet

- Attention Deficit Disorder In Adults: Practical Help and UnderstandingFrom EverandAttention Deficit Disorder In Adults: Practical Help and UnderstandingNo ratings yet

- Anti Depressant Skills PDFDocument72 pagesAnti Depressant Skills PDFkajini2No ratings yet

- Grief Case StudyDocument6 pagesGrief Case StudyRich AmbroseNo ratings yet

- Anxiety And Depression: How to Overcome Intrusive Thoughts With Simple PracticesFrom EverandAnxiety And Depression: How to Overcome Intrusive Thoughts With Simple PracticesNo ratings yet

- Depression ChecklistDocument2 pagesDepression ChecklistWaseem QureshiNo ratings yet

- Loved One in Treatment? Now What!: An Essential Handbook for Family Members and Friends Navigating the Path Of A Loved One's Addiction, Treatment, and RecoveryFrom EverandLoved One in Treatment? Now What!: An Essential Handbook for Family Members and Friends Navigating the Path Of A Loved One's Addiction, Treatment, and RecoveryNo ratings yet

- Rancho Los Amigos Scale of Cognitive Recovery AccDocument13 pagesRancho Los Amigos Scale of Cognitive Recovery Accmemi100% (1)

- Modern Anti Depression Management, Recovery, Solutions and Treatment: A Guidebook for healing, mindfulness & understanding depression in relationships, men & women, husbands, teenagers, kids, etc.From EverandModern Anti Depression Management, Recovery, Solutions and Treatment: A Guidebook for healing, mindfulness & understanding depression in relationships, men & women, husbands, teenagers, kids, etc.No ratings yet

- DIVA - 2 - EN - FORM - Invulbaar PDFDocument20 pagesDIVA - 2 - EN - FORM - Invulbaar PDFGerencia Publimax100% (1)

- Argumentessayskeleton2017 ElizabethvaughnDocument7 pagesArgumentessayskeleton2017 Elizabethvaughnapi-358340036No ratings yet

- Diagnostic Interview For ADHD in Adults (DIVA) : EnglishDocument20 pagesDiagnostic Interview For ADHD in Adults (DIVA) : EnglishVigdís Margrétar JónsdóttirNo ratings yet

- Generalized Anxiety DisorderDocument8 pagesGeneralized Anxiety DisorderKat SimborioNo ratings yet

- GDS Scale PDFDocument2 pagesGDS Scale PDFDiyah RahmawatiNo ratings yet

- Adolescent Depression Research PaperDocument6 pagesAdolescent Depression Research Papergz8qs4dn100% (1)

- Physical Assessment - Specifics On General ObservationsDocument14 pagesPhysical Assessment - Specifics On General ObservationsJennifer B. GarciaNo ratings yet

- ADD vs. ADHDDocument13 pagesADD vs. ADHDKathleen Josol100% (1)

- Final PaperDocument7 pagesFinal Paperapi-339682129No ratings yet

- Modified Case Study On Assessment of An Older PersonDocument7 pagesModified Case Study On Assessment of An Older PersonMAE DEVILLANo ratings yet

- KADS6 SpanishDocument4 pagesKADS6 SpanishKemish MartinezNo ratings yet

- Birleson Self-Rating Scale For Child Depressive DisorderDocument4 pagesBirleson Self-Rating Scale For Child Depressive DisordervkNo ratings yet

- A Case Report On Childhood Dysthymia-Low Mood Triggers The EndDocument7 pagesA Case Report On Childhood Dysthymia-Low Mood Triggers The EndAinun Jariah FahayNo ratings yet

- PSYCHE - Tourette'sDocument32 pagesPSYCHE - Tourette'sIngrid Sasha FongNo ratings yet

- Kennedy 1999Document16 pagesKennedy 1999djsuraz0No ratings yet

- The Effects of Depression On The Student's Academic Performances in STI Baliuag and Ways How To Cope With ItDocument18 pagesThe Effects of Depression On The Student's Academic Performances in STI Baliuag and Ways How To Cope With Itarisu100% (1)

- Research Paper On Adolescent DepressionDocument4 pagesResearch Paper On Adolescent DepressionafeaxlaaaNo ratings yet

- Postnatal DepressionDocument17 pagesPostnatal Depressionmaria100% (1)

- Helping Mothers With The Emotional Dysregulation of Borderline Personality Disorder and Their Infants in Primary Care SettingsDocument9 pagesHelping Mothers With The Emotional Dysregulation of Borderline Personality Disorder and Their Infants in Primary Care SettingsyundaNo ratings yet

- APA - DSM 5 Diagnoses For Children PDFDocument3 pagesAPA - DSM 5 Diagnoses For Children PDFharis pratamsNo ratings yet

- GrievingDocument31 pagesGrievingmelodyfathiNo ratings yet

- Generalised Anxiety Disorder ThesisDocument5 pagesGeneralised Anxiety Disorder Thesisalyssahaseanchorage100% (2)

- Session 6-9 CFU - NUR 152 RLEDocument3 pagesSession 6-9 CFU - NUR 152 RLEDarwin QuirimitNo ratings yet

- DIVA-5 Diva 5 Id English FormDocument20 pagesDIVA-5 Diva 5 Id English FormEspíritu Ciudadano92% (26)

- Jurnal AntidepresanDocument15 pagesJurnal AntidepresanKelvinNo ratings yet

- NURS8337 Exam2Document21 pagesNURS8337 Exam2Solange WilsonNo ratings yet

- Bibliotherapy ActivityDocument8 pagesBibliotherapy ActivityRichelle Delos ReyesNo ratings yet

- Late NakoDocument2 pagesLate NakoJoanna Marie MaglangitNo ratings yet

- 6-Item - KADS - Portuguese - Package Escala de Depressão para AdolescentesDocument4 pages6-Item - KADS - Portuguese - Package Escala de Depressão para Adolescentesmaisalazzarone8652No ratings yet

- Geriatric DepressionDocument2 pagesGeriatric DepressionelvinegunawanNo ratings yet

- Clinical Case Scenarios PDF 136292509 PDFDocument23 pagesClinical Case Scenarios PDF 136292509 PDFRheeza Elhaq100% (2)

- Major Depression in Children and Adolescents: ObjectiveDocument2 pagesMajor Depression in Children and Adolescents: ObjectiveJonty ArputhemNo ratings yet

- Max Hamilton (1 5)Document5 pagesMax Hamilton (1 5)retnoNo ratings yet

- HDRS PDFDocument7 pagesHDRS PDFFelipeNo ratings yet

- Max Hamilton Rating ScaleDocument2 pagesMax Hamilton Rating ScaleretnoNo ratings yet

- Adhd EssayDocument3 pagesAdhd Essayapi-241238813No ratings yet

- Annotated-Research 20paperDocument7 pagesAnnotated-Research 20paperapi-667261947No ratings yet

- Teen DepressionDocument2 pagesTeen DepressionKshitij Ghumaria100% (2)

- Live and Work WellDocument2 pagesLive and Work WellW1ngch0nNo ratings yet

- Notre Dame of Jaro, Inc.: Module in Pe& Health 11Document6 pagesNotre Dame of Jaro, Inc.: Module in Pe& Health 11mark jay legoNo ratings yet

- Reflective Case StudyDocument33 pagesReflective Case StudyAmir MahmoudNo ratings yet

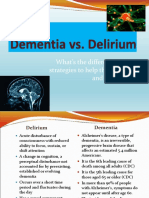

- Dementia and DeliriumDocument20 pagesDementia and DeliriumWyz ClassNo ratings yet

- Research Paper About Teenage DepressionDocument5 pagesResearch Paper About Teenage Depressiond1fytyt1man3100% (1)

- Neurobiological Theories of ConsciousnessDocument14 pagesNeurobiological Theories of ConsciousnessRodrigo Aguirre BáezNo ratings yet

- Neurobiological Theories of ConsciousnessDocument14 pagesNeurobiological Theories of ConsciousnessRodrigo Aguirre BáezNo ratings yet

- Prefrontal Contributions To Metacognition in Perceptual Decision MakingDocument9 pagesPrefrontal Contributions To Metacognition in Perceptual Decision MakingRodrigo Aguirre BáezNo ratings yet

- Integrative Systematic Review of Psychodrama Psychotherapy Research Trends and Methodological Implications PDFDocument26 pagesIntegrative Systematic Review of Psychodrama Psychotherapy Research Trends and Methodological Implications PDFRodrigo Aguirre BáezNo ratings yet

- Social Cognitive Neuroscience A Review of Core ProcessesDocument35 pagesSocial Cognitive Neuroscience A Review of Core ProcessesRodrigo Aguirre BáezNo ratings yet

- Knowing Your Own Heart Distinguishing Interoceptive Accuracy From Interoceptive AwarenessDocument10 pagesKnowing Your Own Heart Distinguishing Interoceptive Accuracy From Interoceptive AwarenessRodrigo Aguirre BáezNo ratings yet

- Human Prefrontal Cortex - Processind and Representational PerspectivesDocument9 pagesHuman Prefrontal Cortex - Processind and Representational PerspectivesRodrigo Aguirre BáezNo ratings yet

- C Uestion RioDocument8 pagesC Uestion RioLuisanaMoralesNo ratings yet

- How The Visual Brain Encodes and Keeps Track of TimeDocument8 pagesHow The Visual Brain Encodes and Keeps Track of TimeRodrigo Aguirre BáezNo ratings yet

- Intelectual Test de MatricesDocument26 pagesIntelectual Test de MatricesMauricio PalaciosNo ratings yet

- Depression and Cognitive Impairment in Older Adults: Geriatric Disorders (DC Steffens, Section Editor)Document9 pagesDepression and Cognitive Impairment in Older Adults: Geriatric Disorders (DC Steffens, Section Editor)Rodrigo Aguirre BáezNo ratings yet

- Late-Life Depression, Mild Cognitive Impairment, and DementiaDocument7 pagesLate-Life Depression, Mild Cognitive Impairment, and DementiaRodrigo Aguirre BáezNo ratings yet

- The Patterns of Cognitive and Functional Impairment in Amnestic and Non-Amnestic MCI in Geriatric Depression. ReinliebDocument14 pagesThe Patterns of Cognitive and Functional Impairment in Amnestic and Non-Amnestic MCI in Geriatric Depression. ReinliebRodrigo Aguirre BáezNo ratings yet

- Polifarmacia ActualizacionDocument10 pagesPolifarmacia ActualizacionMiguelySusy Ramos-RojasNo ratings yet

- Screening Performance of The 15-Item Geriatric Depression Scale in A Diverse Elderly Home Care PopulationDocument8 pagesScreening Performance of The 15-Item Geriatric Depression Scale in A Diverse Elderly Home Care PopulationRodrigo Aguirre BáezNo ratings yet

- Integrative Systematic Review of Psychodrama Psychotherapy Research Trends and Methodological Implications PDFDocument26 pagesIntegrative Systematic Review of Psychodrama Psychotherapy Research Trends and Methodological Implications PDFRodrigo Aguirre BáezNo ratings yet

- Liang Kung Chen 2020Document13 pagesLiang Kung Chen 2020Rodrigo Aguirre BáezNo ratings yet

- Accepted Manuscript: MaturitasDocument18 pagesAccepted Manuscript: MaturitasRodrigo Aguirre BáezNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Cognitive Performance and Decline in 20 Diverse Ethno-Regional Groups: A COSMIC Collaboration Cohort StudyDocument27 pagesDeterminants of Cognitive Performance and Decline in 20 Diverse Ethno-Regional Groups: A COSMIC Collaboration Cohort StudyRodrigo Aguirre BáezNo ratings yet

- Heser 2016Document15 pagesHeser 2016Rodrigo Aguirre BáezNo ratings yet

- Association of Depressive Symptoms With Decline of Cognitive Function - Rugao Longevity and Ageing StudyDocument7 pagesAssociation of Depressive Symptoms With Decline of Cognitive Function - Rugao Longevity and Ageing StudyRodrigo Aguirre BáezNo ratings yet

- Issue 4 PDFDocument2 pagesIssue 4 PDFNa DilanNo ratings yet

- JNEUROSCIENCEDocument40 pagesJNEUROSCIENCERodrigo Aguirre BáezNo ratings yet

- Integrative Systematic Review of Psychodrama Psychotherapy Research Trends and Methodological Implications PDFDocument26 pagesIntegrative Systematic Review of Psychodrama Psychotherapy Research Trends and Methodological Implications PDFRodrigo Aguirre BáezNo ratings yet

- Microstates As Disease and Progression Markers in Patients With Mild Cognitive ImpairmentDocument11 pagesMicrostates As Disease and Progression Markers in Patients With Mild Cognitive ImpairmentRodrigo Aguirre BáezNo ratings yet

- Attachment 8 LAST REVISED 20/04/2018: PHD in Neural and Cognitive Sciences in BriefDocument3 pagesAttachment 8 LAST REVISED 20/04/2018: PHD in Neural and Cognitive Sciences in BriefRodrigo Aguirre BáezNo ratings yet

- Cronicon: Letter To Editor Neuropsychological Impairment in Major Depressive DisorderDocument2 pagesCronicon: Letter To Editor Neuropsychological Impairment in Major Depressive DisorderRodrigo Aguirre BáezNo ratings yet

- JNEUROSCIENCEDocument40 pagesJNEUROSCIENCERodrigo Aguirre BáezNo ratings yet

- Adoçante e Resistência À Insulina - Nature PDFDocument17 pagesAdoçante e Resistência À Insulina - Nature PDFMell FalcãoNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Health Psychology 7th Edition TaylorDocument26 pagesTest Bank For Health Psychology 7th Edition Taylorsequelundam6h17s100% (10)

- Ganser Syndrome: A Case Report From ThailandDocument4 pagesGanser Syndrome: A Case Report From ThailandYuyun Ayu ApriyantiNo ratings yet

- Mental Health and Psychiatric NursingDocument14 pagesMental Health and Psychiatric NursingJAY-AR DAITNo ratings yet

- The Assessment of Anxiety States by RatingDocument6 pagesThe Assessment of Anxiety States by RatingGilbert LimenNo ratings yet

- Shall We Really Say Goodbye To First Rank SymptomsDocument6 pagesShall We Really Say Goodbye To First Rank SymptomsJujae YunNo ratings yet

- Somatoform DisordersDocument88 pagesSomatoform DisordersGothanda RamanNo ratings yet

- Procena Zdravstvenog Stanja I Kvaliteta Zivota Beskucnika U Beogradu PDFDocument8 pagesProcena Zdravstvenog Stanja I Kvaliteta Zivota Beskucnika U Beogradu PDFVanja PalčekNo ratings yet

- 6 DepressionDocument42 pages6 DepressionEIorgaNo ratings yet

- The Flight of The MindDocument285 pagesThe Flight of The Mindmusic2850No ratings yet

- CHOI, Sung-Youl KIM, Geun-Woo. (2018)Document3 pagesCHOI, Sung-Youl KIM, Geun-Woo. (2018)Rafael ConcursoNo ratings yet

- GHQ ScoringDocument13 pagesGHQ ScoringMonica IuliaNo ratings yet

- COMLEX Level 3 Time Grid and Self AssessmentDocument19 pagesCOMLEX Level 3 Time Grid and Self AssessmentR KidderNo ratings yet

- Abram Hoffer - Prousky - Orthomolecular Treatment of Anxiety DisordersDocument7 pagesAbram Hoffer - Prousky - Orthomolecular Treatment of Anxiety DisordersEbook PDFNo ratings yet

- CBCL Overview of The Development of The Original and Brazilian VersionDocument16 pagesCBCL Overview of The Development of The Original and Brazilian VersionDoniLeiteNo ratings yet

- QIM 2011 Symposium E-Proceedings 0Document369 pagesQIM 2011 Symposium E-Proceedings 0aleksapaNo ratings yet

- PentingDocument5 pagesPentingrsudabadiNo ratings yet

- BSC Psychology PPR New 2022Document28 pagesBSC Psychology PPR New 2022ranith sociologyNo ratings yet

- What's New With DSM 5? (Formerly Known As DSM V) : 1 Credit Continuing Education CourseDocument15 pagesWhat's New With DSM 5? (Formerly Known As DSM V) : 1 Credit Continuing Education CourseTodd Finnerty44% (9)

- Functional Neurological Disorders: It Is All in The Head: Linda ThomsonDocument12 pagesFunctional Neurological Disorders: It Is All in The Head: Linda ThomsonKit GuintoNo ratings yet

- Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Clinical Practice Guidelines Management of Anxiety DisordersDocument6 pagesGeneralized Anxiety Disorder: Clinical Practice Guidelines Management of Anxiety DisordersDaciana DumitrescuNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology of A Anxiety Disorder PDFDocument7 pagesPathophysiology of A Anxiety Disorder PDFpragna novaNo ratings yet

- Unit-2 Human Values Updated ContentDocument63 pagesUnit-2 Human Values Updated ContentTanya GuptaNo ratings yet

- CASE 7 Somatic Symptom DisorderDocument11 pagesCASE 7 Somatic Symptom DisorderApril AstilloNo ratings yet

- Compiled Lecture Materials: Human Behavior and VictimologyDocument64 pagesCompiled Lecture Materials: Human Behavior and Victimologyanna lei mazaredoNo ratings yet

- Applied Psychology 29 8 18Document52 pagesApplied Psychology 29 8 18SoouNo ratings yet

- From Psychosomatics To NeuropsychoanalysiDocument19 pagesFrom Psychosomatics To NeuropsychoanalysiJosMaBeas100% (1)

- Somatic Therapy: Reporter: Daryl S. AbrahamDocument10 pagesSomatic Therapy: Reporter: Daryl S. AbrahamBiway RegalaNo ratings yet

- 2002-Conversion Disorder in Children and Adolescents A 4-Year Follow-Up StudyDocument5 pages2002-Conversion Disorder in Children and Adolescents A 4-Year Follow-Up StudyJuan Francisco YelaNo ratings yet

- Consultation and Liaison Consultation and Liaison Psychiatry (PDFDrive)Document70 pagesConsultation and Liaison Consultation and Liaison Psychiatry (PDFDrive)mlll100% (1)

- Chronic Fatigue Syndrome A ReviewDocument16 pagesChronic Fatigue Syndrome A ReviewMarcelita DuwiriNo ratings yet