Professional Documents

Culture Documents

JaLEVIK Et Al-2007

Uploaded by

player osamaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

JaLEVIK Et Al-2007

Uploaded by

player osamaCopyright:

Available Formats

DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2007.00849.

Evaluation of spontaneous space closure and development of

Blackwell Publishing Ltd

permanent dentition after extraction of hypomineralized

permanent first molars

BIRGITTA JÄLEVIK1 & MARIE MÖLLER2

1

Specialist Clinic of Pedodontics and 2Orthodontics, Sahlgrenska University Hospital Mölndal, Sweden

International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry 2007; 17: 328– Results. Fifteen children were judged to have a

335 favourable spontaneous development of their

permanent dentition without any orthodontic inter-

Aim. The aim of this study was to evaluate spon- vention. Seven children were or should be subjected

taneous space closure, development of the permanent to orthodontic treatment for other reasons registered

dentition, and need for orthodontic treatment after prior to the extraction. Five children were judged

extraction of permanent first molars due to severe to have a treatment at least caused by the extrac-

molar–incisor hypomineralization (MIH). tions, but three of them abstained because of no

Subjects. Twenty-seven children aged 5.6–12.7 subjective treatment need.

(median 8.2) years had one to four permanent Conclusion. Extraction of permanent first molars

first molars extracted due to severe MIH. Each case severely affected by MIH is a good treatment

was followed up on individual indications 3.8–8.3 alternative. Favourable spontaneous space reduction

(median 5.7) years after extractions. and development of the permanent dentition

The eruption of the permanent dentition, and space positioning can be expected without any inter-

closure were documented by orthopantomograms, vention in the majority of cases extracted prior to

casts, photographs, and/or bitewings. the eruption of the second molar.

morphology in the porous enamel is altered6,

Introduction

making bonding hazardous, and a substantial

Hypomineralized permanent first molars, often amount of defective fillings and need of re-

in combination with hypomineralized incisors treatment in MIH teeth have been reported8 –11.

[molar–incisor hypomineralization (MIH)]1, As a consequence of repeated painful treat-

are common (3.6–19.3%) in many child pop- ments, children with severe MIH have been

ulations2–5. The severely affected molars often reported to display more behaviour manage-

show disintegration of the enamel in the occlusal ment problems and more dental fear and

parts6 and require extensive treatment4. These anxiety8. In cases with extensive disintegration,

teeth create problems both for the patients and troublesome hypersensivity, and/or increasing

for the dentists. Children often report shooting dental anxiety, the extraction of the tooth

pain when they are brushing their teeth or might be the therapy of choice.

even breathing cold air often shortly after the From the orthodontists’ point of view, there

eruption of the affected teeth has started. The have been conflicting opinions about the

severely affected teeth are soon in need of benefit of extracting permanent first molars

restoration due to disintegrating enamel and with poor prognosis and there is little evidence

subsequent caries7. for the rationale of the timing and extraction

The treatments can be painful due to dif- pattern for the first permanent molar12. The

ficulties in anaesthetizing. The prismatic opinions about first-molar extraction range

between the unbridled enthusiasm expressed

by Wilkinson13 to the great scepticism expressed

Correspondence to:

Birgitta Jälevik, Specialist Clinic of Pedodontics, Sahlgrenska by Mill14. Thilander and Skagius have reported

University Hospital Mölndal, SE-431 80 Mölndal, Sweden. that the best results were found when extrac-

E-mail: birgitta.jalevik@vgregion.se tions were performed during 8 –10 years of age.

© 2007 The Authors

328 Journal compilation © 2007 BSPD, IAPD and Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Space closure after extraction of first molars 329

Crowding in the relevant quadrant was also therapy was avoided in the lower jaw unless

found to be favourable for a good orthodontic the opposite upper molar was extracted.

result as well as presence of the third molar15. Three children (cases 5, 9, and 14) had ortho-

Mandibular first-molar extraction might also dontic treatment directly after the extractions

increase the space for mandibular third-molar and therefore the spontaneous bite development

eruption and helps the third molars move to could not be evaluated. All three had lower

better position16. Furthermore, it has been first permanent molar(s) extracted after the

shown that early loss of permanent first molars eruption of the second molars, i.e. late extraction

might have an accelerating effect on develop- (11.6 to 14.4 year olds). Those cases are

ment of the third molar on the extraction side17. shown in Table 1 in italics. As further three of

Williams and Gowans12 recommended consider- the patients had migrated, the follow up was

ing compensating extraction of the opposing based on 27 children (15 girls and 12 boys),

maxillary permanent first molar when extracting where eruption and development of the per-

the mandibular permanent first molar. Further- manent dentition was followed.

more, in case of crowding in the mandibular After the extractions, the development was

arch they strongly recommended considering followed and the need for orthodontic treatment

balancing extraction of the contra-lateral lower was judged. Each case was followed after

permanent first molar. individual indications, and the development

The aim of this study was to evaluate the was documented by orthopantomograms, casts,

development of the permanent dentition and photographs, and/or bitewings.

need for orthodontic treatment after extraction The median age at the time of extraction for

of permanent first molars due to severe MIH. 27 children was 8.2 year (range 5.6–12.7). The

median follow-up time was 5.7 year (range

3.8–8.3). The children each had an average of

Materials and methods

2.6 molars extracted. The distribution is shown

A total of 33 children who had one to four in Table 1.

first permanent molars extracted due to severe Evaluations of development of the permanent

MIH and poor prognosis were eligible for dentition were performed by the authors, a

this follow-up evaluation. These cases have specialist in orthodontics (MM), and a specialist

previously been reported in a study analysing in paediatric dentistry (BJ). Criteria for good

histo-morphology of teeth with MIH6. The or favourable bite development were sponta-

children were the patients consecutively referred neous space reduction, no tilting of teeth that

to Specialist Clinic of Pedodontics, Sahlgrenska could make oral hygiene more difficult, no

University Hospital, Mölndal, and to the Depart- teeth elongation in the opposite jaw, and patient

ment of Pedontontics, Faculty of Odontology, satisfaction.

Göteborg University, in October 1996 to January

1999 due to severe MIH. In all cases, difficulties

Results

in performing lasting filling therapy and/or

continues sensitivity in these teeth were Patient material, number of first molars

reported. In agreement with the orthodontists, extracted, age at extractions, and need of ortho-

a more radical treatment option was decided dontic treatment are shown schematically in

implying extraction the troublesome teeth. Table 1.

Exclusion criteria for extraction therapy were

general spacing and/or agenesis of permanent

Orthodontic treatment

teeth in the quadrant concerned with exception

of third molars. It was not possible to judge if Fifteen children were considered to have a

the child had third molars or not before the favourable bite development without any ortho-

age of nine approximately. If pre-normality, dontic intervention (Figs 1 and 3b,c). Three

extraction therapy was avoided in the upper children (cases 5, 9, and 14) had orthodontic

jaw unless the opposite lower molar was treatment directly after the extractions and

extracted. If post-normal relation, extraction therefore the spontaneous bite development

© 2007 The Authors

Journal compilation © 2007 BSPD, IAPD and Blackwell Publishing Ltd

330 B. Jälevik & M. Möller

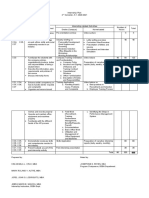

Table 1. Patient material by gender, age at extraction, and evaluated need for orthodontic treatment at follow up.

Extracted Good bite Need for Need for Need for

Age at teeth development orthodontics orthodontics orthodontics,

Patient Age at evaluation without not related to caused by extraction(s)

no. Gender extraction (year) (year) 16 26 36 46 intervention extraction(s) extraction(s) partly involved

1 F 8.8 15.9 x x x x Yes

2 F 11.1 16.2 x x Yes

3 M 8.4 15.0 x Yes

4 M 12.3 16.7 x Yes

5 F 13.1 19.0 x x x x Yes†

6 M 10.3 16.3 x x x x Yes

7 F 6.9 13.2 x Yes

8 F 8.7 13.7 x Yes

9 F 14.4 18.9 x x Yes†

10 F 7.5 13.2 x Yes

11 F 7.2 12.9 x Yes

12 F 7.9 12.1 x x x x Yes

13 M 12.7 16.9 x x x Yes

14 F 11.6 16.0 x Yes†

15 M 7.7 13.1 x x Yes

16 F 9.6 14.6 x x x x Yes

17 F 8.2 13.8 x x x x Yes

18 F 8.3 12.2 x x x x Yes

19 M 8.2 12.7 x x x Yes‡

20 M 8.9 13.8 x Yes

21 M 8.7 13.6 x Yes

22 M 5.6 13.9 x x x x Yes

23 F 6.8 13.9 x x x§ Yes

24 F 6.2 12.9 x x x Yes

25 M 8.4 15.2 x x x x Yes

26 F 7.8 15.3 x x x x Yes‡

27 F 6.9 13.4 x x x Yes

28 F 7.9 15.3 x x x x Yes‡

29 M 8.1 13.6 x Yes

30 M 9.5 15.3 x x Yes

†Orthodontic treatment directly after the extraction.

‡Abstained from orthodontic treatment.

§Extracted at 11.9 years of age.

could not be evaluated. They all had lower extraction of the first molar. One of these

first permanent molar(s) extracted after the patients (case 28) abstained from orthodontic

eruption of the second molars, i.e. late extraction treatment because of no subjective treatment

(11.6 to 14.4 year olds). Seven children were need. Three were offered orthodontic treatment

or should be subjected to orthodontic treat- to correct gaps, spacing, or deficiencies in occlu-

ment for other reasons, e.g. crowding of fronts sion caused by the extractions. Two of them

as well as crossbites, or distal bites (Fig. 2) (cases 19 and 26) abstained from orthodontic

registered prior to the extraction. Two children treatment because of no subjective treatment

(cases 16 and 28) were offered treatment for need. The third child (case 23) had a lower

orthodontic problems partly due to the extrac- permanent first molar extracted at late age.

tions. Case 16 had esthetical problems with This case (23) is of particular interest. She had

irregular upper front teeth and peg-shaped her two upper first molars extracted at the age

laterals. Case 28 had open bite on the right side of 6.8 years. It was also decided to extract the

due to abnormal swallow pattern. Beside that, left lower first molar, but the orthodontic con-

she also had mesial inclination of the lower sultant recommended postponing the extraction

second molar and some distal inclination of until the second lower molar was beginning

lower second premolar on this side due to to erupt in order to get optimal spontaneous

© 2007 The Authors

Journal compilation © 2007 BSPD, IAPD and Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Space closure after extraction of first molars 331

Fig. 1. Case 17. Tooth eruption and

positioning in a girl having all

permanent first molars extracted at the

age of 8.2 years.

© 2007 The Authors

Journal compilation © 2007 BSPD, IAPD and Blackwell Publishing Ltd

332 B. Jälevik & M. Möller

Fig. 2. Case 13 had 26, 36, and 46

extracted at the age of 12.7 years.

Crossbite on both sides, frontal open

bite, and crowding were registered

prior to extractions.

space closure. The tooth was extracted at

Space closure, inclination of adjacent teeth, and

11.9 years of age (Fig. 3a). Two and a half

centreline shift

years later, the girl was referred to orthodontic

treatment because of remaining gap, and mesial About two-thirds of the children had good

as well as lingual tilting of the lower second spontaneous space closure after the extractions

molar. Two other girls (cases 24 and 27) had with no or minor remaining gaps (Figs 1, 2 and

the same teeth (16, 26, 36) extracted, all teeth 3a,b). Every tenth child had gaps and every

before the age of seven. They had a good fifth had spacing in the involved quadrants

spontaneous bite development (Fig. 3b,c) after extraction (Fig. 4).

© 2007 The Authors

Journal compilation © 2007 BSPD, IAPD and Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Space closure after extraction of first molars 333

Fig. 3. (a) Case 23 had 16 and 26

extracted at 6.8 years of age, 36

extracted at 11.9 years of age. (b) Case

24 had 16, 26, and 36 extracted at 6.2

years of age. (c) Case 27 had 16, 26, and

36 extracted at 6.9 years of age.

Fig. 4. A 15-year-old boy (case 3) who

had his right lower permanent first

molar extracted at the age of 8.5 years.

In the affected quadrant there are

some general spacing and also slight

tilting of the second molar mesially and

the premolars distally.

Mesial inclination of the second molar was (Figs 1 and 4). The bicuspids had drifted some-

seen in about two-thirds of the children. How- what distally in less than one-third of the

ever, in all cases but four, the inclination was cases that had lower first molar(s) extracted.

minor, and in no case there was a severe tilting. In three of these cases (3, 6, and 28), there

Tilting was more common in the lower jaw was also a slight distal tilting of the bicuspids.

© 2007 The Authors

Journal compilation © 2007 BSPD, IAPD and Blackwell Publishing Ltd

334 B. Jälevik & M. Möller

Distal inclination of the tooth germ of the dentition after first-molar extraction in the

second bicuspid before eruption is characteristic majority of cases.

for these cases (Fig. 4). In any of these cases, Twelve children were offered orthodontic

impaction of a second premolar was seen. treatment but seven of them (26% of the whole

In four children (cases 3, 4, 13, and 19), a group) had common orthodontic problems as

lower first molar was extracted but not the crowding, crossbites, and distal bites which

upper opposite first molar (Figs 2 and 4). They not could be related to the extractions. The

all had a favourable development. In two of orthodontic treatment besides first molars

those cases (13 and 19), the upper opposite extraction was in accordance with a recent

first molar was extracted on one side but not systematic literature review which reported

on the other (Fig. 2). The bite development that the need for orthodontic treatment in the

was not more favourable on either side. Swedish population was 27%19. The remaining

When extraction was performed in the upper five children were offered orthodontic treat-

jaw and not in the lower, a common situation, ment for reason which could be related to

the bite development was still good. extractions. In one case (23), the extraction of

In no case, we revealed unfavourable a lower first molar had been postponed

centreline shift that could be derived from a because the dentist had waited for the second

unilateral extraction. molar to erupt. Case 26 had agenesis of all

third molars and case 19 had not the tooth

germs of the third molars visible until 11 years

Presence of third molars

old. These findings are in accordance with

Three cases (12, 21, and 26) had all third Thilander and Skagius, who found the best

molars missing and two cases (8 and 18) had result when extractions were performed at 8 –

two third molars missing. Seventy-nine per 10 years of age and when the third molars

cent of the exactions had been performed in were present15. The remaining two children (case

a jaw half with a third molar present. 16 and 28) had, as mentioned before, besides

spacing, respectively, tilting caused by the

extractions and other complicating orthodontic

Discussion

problems. Remarkable, only two of those five

This study has shown that extraction of per- children had a subjective treatment need.

manent first molars severely affected by MIH Earlier extractions of, especially, lower per-

can be a good treatment option. Preferably, the manent first molar were not recommended

extractions should be planned in collaboration because of risk of the lower second premolar

with an orthodontist, before the eruption of tilting and drifting distally12. This fear was not

the second permanent molar. verified in the present study. Instead, all cases

The extraction of permanent first molars has that had a lower and/or upper first molar

been controversial for a long time12,18. However, extracted at an early age had a good sponta-

in the latter half of the last century, orthodon- neous development.

tists took a more positive attitude to extraction A clinical dilemma is if compensating

of the permanent first molars. The extraction extraction of an opposing healthy first molar

of permanent first molars severely affected by or balancing extraction of a contra lateral

MIH draws conflicting opinions between the healthy first molar ought to be carried out.

paediatric dentists and more conservative Williams and Gowans recommend considering

orthodontists. The paediatric dentists have to compensating extraction of an upper molar

perform technically complicated fillings in a child when you extract the opposing molar to avoid

with increasing dental anxiety and behaviour- elongation. As a preventive measure in avoiding

management problems8, whereas the ortho- centreline shift, they recommend considering

dontists may want to preserve the importance balancing extraction of an upper as well as a

of keeping permanent first molars. lower molar when extracting the contra lateral

This follow-up study shows favourable molar12. In this follow up, uncompensated and

spontaneous development of the permanent unbalanced extractions were performed. In

© 2007 The Authors

Journal compilation © 2007 BSPD, IAPD and Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Space closure after extraction of first molars 335

spite of this, there was a good spontaneous impact on the treatment need. Caries Res 2001; 35:

occlusal development. Therefore, you can 36–40.

5 Weerheijm KL, Groen HJ, Beentjes VEVM, Poorterman

assume that compensating and/or balancing

JHG. Prevalence in 11-year-old Dutch children of

extraction is not always beneficial when cheese molars. ASDC J Dent Child 2001; 68: 259 –262.

extracting a permanent first molar. 6 Jälevik B, Norén JG. Enamel hypomineralization of

Recent studies have shown that you can permanent first molars. A morphological study and

expect earlier development and better position- survey of possible etiologic factors. Int J Paediatr Dent

ing of the third molar when extracting the first 2000; 10: 278–289.

7 Alaluusua S, Bäckman B, Brook AH, Lukinmaa P-L.

molar16,17. As the majority of the extractions in Developmental defects of dental hard tissue and

this study were performed in quadrants with their treatment. In: Koch G, Poulsen S, (eds). Pediatric

third molars present you can expect an earlier Dentistry – A Clinical Approach. Copenhagen: Munks-

eruption and fewer problems with the third- gaard, 2001: 273–299.

molar impaction as a favourable side-effect. 8 Jälevik B, Klingberg G. Dental treatment, dental fear

and behaviour management problems in children

In conclusion, spontaneous space reduction

with severe enamel hypomineralization of their

and favourable development of the permanent permanent first molars. Int J Paediatr Dent 2002; 12:

dentition can be expected when extracting a 24–32.

severely hypomineralized permanent first molar 9 Mejare I, Bergman E, Grindefjord M. Hypomineralized

prior to the eruption of the second permanent molars and incisors of unknown origin: treatment

molar. outcome at age 18 years. Int J Paediatr Dent 2005; 15:

20–28.

10 Kotsanos N, Kaklamanos EG, Arapostathis K.

Treatment management of first permanent molars in

What does this paper adds children with molar–incisor hypomineralisation.

• Good spontaneous space closure can be expected when Eur J Paediat Dent 2005; 6: 179–184.

extracting a permanent first molar prior to eruption of 11 Williams V, Messer LB, Burrow MF. Molar: incisor

the permanent second molar. hypomineralization: review and recommendations

• Extraction of a permanent first molar with bad

for clinical management. Pediatr Dentist 2006; 28:

prognosis could be a good treatment alternative.

224–232.

Why this paper is important to paediatric dentists 12 Williams JK, Gowans AJ. Hypomineralised first

• Paediatric dentists often meet children who suffer great permanent molars and the orthodontist. Eur J

pain as a result of seriously hypomineralized Paediatr Dent 2003; 4: 129–132.

permanent first molars. 13 Wilkinson AA. The permanent first molar again. Brit

• Early extraction of teeth affected by MIH may prevent Dent J 1940; 8: 269–284.

future dental problems.

14 Mills JRE. Principles and Practice of Orthodontics, 2nd

edn. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1987: 123–125.

15 Thilander B, Skagius S. Orthodontic sequelae of

References extraction of permanent first molars. A longitudinal

study. Rep Cong Eur Orthod Soc 1970; 429–442.

1 Weerheijm K, Jälevik B, Alaluusua S. Molar–incisor 16 Ay S, Agar U, Bicakci AA, Kosger HH. Changes in

hypomineralisation (MIH). Caries Res 2001; 35: 390– mandibular third molar angle and position after

391. unilateral mandibular first molar extraction. Am J

2 Koch G, Hallonsten A-L, Ludvigsson N, Hansson B-O, Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2006; 129: 36–41.

Holst A, Ullbro C. Epidemiologic study of idiopathic 17 Yavuz I, Baydas B, Ikbal A, Dagsuyu IM, Ceylan I.

enamel hypomineralization in permanent teeth of Effects of early loss of permanent first molars on the

Swedish children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol development of third molars. Am J Orthod Dentofacial

1987; 15: 279 –285. Orthop 2006; 130: 634–638.

3 Jälevik B, Klingberg G, Barregård L, Norén JG. The 18 Sandler PJ, Atkinson R, Murray AM. For four sixes.

prevalence of demarcated opacities in permanent first Am J Dentofacial Orthop 2000; 117: 418–434.

molars in a group of Swedish children. Acta Odontolol 19 The Swedish Council on Technology Assessment

Scand 2001; 59: 255 –260. in Health Care. Bettavvikelser och tandreglering ett

4 Leppäniemi A, Lukinmaa PL, Alaluusua S. Nonfluoride hälsoperspektiv – En systematisk litteraturöversikt.

hypomineralizations in the first molars and their SBU-Rapport 2005; 176: 49–61.

© 2007 The Authors

Journal compilation © 2007 BSPD, IAPD and Blackwell Publishing Ltd

You might also like

- Prevalence of Loss of Permanent First Molars in A Group of Romanian Children and AdolescentsDocument8 pagesPrevalence of Loss of Permanent First Molars in A Group of Romanian Children and AdolescentsZvikyNo ratings yet

- 2016 Belgrad EAPD PDFDocument82 pages2016 Belgrad EAPD PDFMirel TomaNo ratings yet

- Ambard 2019Document4 pagesAmbard 2019Akanksha MahajanNo ratings yet

- Periodontal Root Coverage: An Evidence-Based Guide to Prognosis and TreatmentFrom EverandPeriodontal Root Coverage: An Evidence-Based Guide to Prognosis and TreatmentNo ratings yet

- Third Molar Extractions: Evidence-Based Informed Consent: Residents' Journal ReviewDocument4 pagesThird Molar Extractions: Evidence-Based Informed Consent: Residents' Journal Reviewplayer osamaNo ratings yet

- Peri-Implant Complications: A Clinical Guide to Diagnosis and TreatmentFrom EverandPeri-Implant Complications: A Clinical Guide to Diagnosis and TreatmentNo ratings yet

- PIIS0889540612000881Document11 pagesPIIS0889540612000881Aly OsmanNo ratings yet

- The Premature Loss of Primary First Molars: Space Loss To Molar Occlusal Relationships and Facial PatternsDocument6 pagesThe Premature Loss of Primary First Molars: Space Loss To Molar Occlusal Relationships and Facial PatternsZaenuriNo ratings yet

- Causes of Primary and PermanentDocument11 pagesCauses of Primary and PermanentUSER BGNo ratings yet

- Bompereta Labial 2Document7 pagesBompereta Labial 2Aleja LombanaNo ratings yet

- 2019 Mcnamara 40 AñosDocument13 pages2019 Mcnamara 40 AñosshadiNo ratings yet

- Interdisciplinary Management of Nonsyndromic Oligodontia With Multiple Retained Deciduous Teeth: A Rare Case ReportDocument4 pagesInterdisciplinary Management of Nonsyndromic Oligodontia With Multiple Retained Deciduous Teeth: A Rare Case ReportAdvanced Research PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Examination of Antimicrobial and AntiinfDocument66 pagesExamination of Antimicrobial and AntiinfCristina CapettiNo ratings yet

- A Multidisciplinary Treatment of CongenitallyDocument7 pagesA Multidisciplinary Treatment of CongenitallyStephanie Patiño MNo ratings yet

- Dental Caries and Pericoronitis Associated With Impacted Mandibular Third Molars-A Clinical and Radiographic StudyDocument6 pagesDental Caries and Pericoronitis Associated With Impacted Mandibular Third Molars-A Clinical and Radiographic StudyFardiansyah DwiristyanNo ratings yet

- Article - 1653239529 2Document5 pagesArticle - 1653239529 2Mega AzzahraNo ratings yet

- Original Article Assessment of Different Patterns of Impacted Mandibular Third Molars and Their Associated PathologiesDocument9 pagesOriginal Article Assessment of Different Patterns of Impacted Mandibular Third Molars and Their Associated PathologiesMaulidahNo ratings yet

- Management of Severe Dento-Alveolar Traumatic Injuries in A 9-YeaDocument7 pagesManagement of Severe Dento-Alveolar Traumatic Injuries in A 9-YeasintaznNo ratings yet

- A Labially Positioned Mesiodens: Case Report: Robert J. Henry, DDS, MS A. Charles Post, DDSDocument5 pagesA Labially Positioned Mesiodens: Case Report: Robert J. Henry, DDS, MS A. Charles Post, DDSDr. Naji ArandiNo ratings yet

- Martinez 10.1111@j.1365-263X.2011.01172.xDocument10 pagesMartinez 10.1111@j.1365-263X.2011.01172.xNicole StoicaNo ratings yet

- Smile Makeover in ChildrenDocument7 pagesSmile Makeover in Childrendavidiaz1989No ratings yet

- Guidance For The Extraction of First Permanent Molars in ChildrenDocument10 pagesGuidance For The Extraction of First Permanent Molars in ChildrenRawan ZaatrehNo ratings yet

- Treatment of A Patient With Oligodontia A Case ReportDocument5 pagesTreatment of A Patient With Oligodontia A Case ReportWindaNo ratings yet

- Effect of Fluoride-Releasing Resin Composite in White Spot Lesions Prevention: A Single-Centre, Split-Mouth, Randomized Controlled TrialDocument7 pagesEffect of Fluoride-Releasing Resin Composite in White Spot Lesions Prevention: A Single-Centre, Split-Mouth, Randomized Controlled TrialXIID 67No ratings yet

- Management of Children With Poor Prognosis Frst41415 - 2023 - Article - 5816Document6 pagesManagement of Children With Poor Prognosis Frst41415 - 2023 - Article - 5816jing.zhao222No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S107387461200093X MainDocument13 pages1 s2.0 S107387461200093X MainMr-Ton DrgNo ratings yet

- Endodontic Management of An Infected Primary Molar in A Child With Agenesis of The Permanent PremolarDocument4 pagesEndodontic Management of An Infected Primary Molar in A Child With Agenesis of The Permanent PremolarFebriani SerojaNo ratings yet

- Extraction of Wisdom Teeth Under General Anesthesia-A StudyDocument5 pagesExtraction of Wisdom Teeth Under General Anesthesia-A StudyCiutac ŞtefanNo ratings yet

- Prevalence and Change of Malocclusions From Primary To Early Permanent Dentition: A Longitudinal StudyDocument7 pagesPrevalence and Change of Malocclusions From Primary To Early Permanent Dentition: A Longitudinal StudyAmadeaNo ratings yet

- Borderline Cases in Orthodontics-A ReviewDocument6 pagesBorderline Cases in Orthodontics-A ReviewShatabdi A ChakravartyNo ratings yet

- Long Term Vertical ChangesDocument5 pagesLong Term Vertical ChangesthganooNo ratings yet

- Late Development of Supernumerary Teeth: A Report of Two CasesDocument6 pagesLate Development of Supernumerary Teeth: A Report of Two CasessauriuaNo ratings yet

- Primary Canine Auto-Transplantation: A New Surgical TechniqueDocument16 pagesPrimary Canine Auto-Transplantation: A New Surgical TechniqueMaryGonzalesʚïɞNo ratings yet

- ScriptDocument3 pagesScriptNurhayani AkhiriyahNo ratings yet

- 3435-Article Text-10228-1-10-20211027Document6 pages3435-Article Text-10228-1-10-20211027Irin Susan VargheseNo ratings yet

- 33 D17 370 Muhammad Harun Achmad1 Yuferaa RezpectorDocument6 pages33 D17 370 Muhammad Harun Achmad1 Yuferaa RezpectorputriandariniNo ratings yet

- Dental Traumatology - 2009 - T Z Ner - Temporary Management of Permanent Central Incisors Loss Caused by TraumaDocument5 pagesDental Traumatology - 2009 - T Z Ner - Temporary Management of Permanent Central Incisors Loss Caused by Traumamidok33No ratings yet

- 5-Management of Space ProblemsDocument10 pages5-Management of Space ProblemsMuhammad UzairNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Premolar Discrepancy Extractions On Tooth-SizeDocument7 pagesThe Effect of Premolar Discrepancy Extractions On Tooth-SizeKanish AggarwalNo ratings yet

- Mta Vs Formocresol PulpotomyDocument4 pagesMta Vs Formocresol PulpotomySitapriya SubrahmanyamNo ratings yet

- Pulpotomy in Mature Permanent TeethDocument8 pagesPulpotomy in Mature Permanent Teethsümeyra akkoçNo ratings yet

- Avulsed TeethDocument3 pagesAvulsed TeethSimona DobreNo ratings yet

- Nonsyndromic Oligodontia With Ankyloglossia A Rare Case Report.20150306123428Document5 pagesNonsyndromic Oligodontia With Ankyloglossia A Rare Case Report.20150306123428dini anitaNo ratings yet

- Orthodontic Management of Midline Diastema in Mixed DentitionDocument5 pagesOrthodontic Management of Midline Diastema in Mixed DentitionfatimahNo ratings yet

- Correction of Severe Tooth Rotation by Using Two Different Orthodontic Appliances: Report of Two CasesDocument6 pagesCorrection of Severe Tooth Rotation by Using Two Different Orthodontic Appliances: Report of Two CasesChelsy OktaviaNo ratings yet

- Can Forces Be Applied Directly To The Root For Correction of A Palatally Displaced Central Incisor With A Dilacerated Root?Document8 pagesCan Forces Be Applied Directly To The Root For Correction of A Palatally Displaced Central Incisor With A Dilacerated Root?Osama SayedahmedNo ratings yet

- Extraction or Nonextraction in Orthodontic Cases - A Review - PMCDocument6 pagesExtraction or Nonextraction in Orthodontic Cases - A Review - PMCManorama WakleNo ratings yet

- Factors Related To Treatment and Outcomes of Avulsed TeethDocument8 pagesFactors Related To Treatment and Outcomes of Avulsed TeethJessie PcdNo ratings yet

- Tendência 2021Document7 pagesTendência 2021ludovicoNo ratings yet

- 2017-Santiago Poster Abstracts PDFDocument105 pages2017-Santiago Poster Abstracts PDFMirel TomaNo ratings yet

- Midline ShiftDocument6 pagesMidline ShiftMaiush JbNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Dentinogenesis ImperfectaDocument10 pagesJurnal Dentinogenesis Imperfectahillary aurenneNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Dental Anomalies in VariousDocument8 pagesPrevalence of Dental Anomalies in VariousMaria SilvaNo ratings yet

- Regional Early Development and Eruption of Permanent Teeth Case ReportDocument5 pagesRegional Early Development and Eruption of Permanent Teeth Case ReportAngelia PratiwiNo ratings yet

- Extraction Planning in Orthodontics: 10.5005/jp-Journals-10024-2307Document5 pagesExtraction Planning in Orthodontics: 10.5005/jp-Journals-10024-2307serahNo ratings yet

- Long-Term Spontaneous Changes Following Removal of All First Premolars in Class I Cases With CrowdingDocument12 pagesLong-Term Spontaneous Changes Following Removal of All First Premolars in Class I Cases With CrowdingElizabeth MesaNo ratings yet

- 2020 Rizell Predictive Factors For Canine Position in Patients With Unilateral Cleft Lip and PalateDocument7 pages2020 Rizell Predictive Factors For Canine Position in Patients With Unilateral Cleft Lip and Palateplayer osamaNo ratings yet

- 2003.john H. Warford JR - Prediction of Maxillary Canine Impaction UsingDocument5 pages2003.john H. Warford JR - Prediction of Maxillary Canine Impaction UsingLuis HerreraNo ratings yet

- Ectopic Eruption of The Maxillary Canine On CephalometDocument8 pagesEctopic Eruption of The Maxillary Canine On CephalometyeiNo ratings yet

- 2000 Ericson Resorption of Incisors AfterDocument9 pages2000 Ericson Resorption of Incisors Afterplayer osamaNo ratings yet

- 2002 Ericson Does The Canine Dental Follicle Cause Resorption ofDocument10 pages2002 Ericson Does The Canine Dental Follicle Cause Resorption ofplayer osamaNo ratings yet

- 2003.john H. Warford JR - Prediction of Maxillary Canine Impaction UsingDocument5 pages2003.john H. Warford JR - Prediction of Maxillary Canine Impaction UsingLuis HerreraNo ratings yet

- Afrand Et Al 2017 AJODODocument11 pagesAfrand Et Al 2017 AJODOplayer osamaNo ratings yet

- Delayed Tooth Eruption Pa Tho Genesis, Diagnosis and Treatment.Document14 pagesDelayed Tooth Eruption Pa Tho Genesis, Diagnosis and Treatment.DrFarhana AfzalNo ratings yet

- 2000 RichardsonDocument5 pages2000 Richardsonplayer osamaNo ratings yet

- A New Guide Using CBCT To Identify TheDocument6 pagesA New Guide Using CBCT To Identify Theplayer osamaNo ratings yet

- Effect of Surgical Exposure Technique, Age, andDocument11 pagesEffect of Surgical Exposure Technique, Age, andplayer osamaNo ratings yet

- Comparison and Reproducibility of 2 Regions of Reference For Maxillary Regional Registration With Cone-Beam Computed TomographyDocument10 pagesComparison and Reproducibility of 2 Regions of Reference For Maxillary Regional Registration With Cone-Beam Computed Tomographyplayer osamaNo ratings yet

- Palatally Impacted Canines A NewDocument9 pagesPalatally Impacted Canines A Newplayer osamaNo ratings yet

- A Treatment Difficulty Index For Unerupted Maxillary CaninesDocument4 pagesA Treatment Difficulty Index For Unerupted Maxillary Caninesplayer osamaNo ratings yet

- AJODO-2013 143 4 446 UmesanDocument2 pagesAJODO-2013 143 4 446 Umesanplayer osamaNo ratings yet

- 2009 Kau A Novel 3D ClassificationDocument6 pages2009 Kau A Novel 3D Classificationplayer osamaNo ratings yet

- Corticotomy Assisted Rapid Maxillary Expansion - 2016 - American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial OrthopedicsDocument2 pagesCorticotomy Assisted Rapid Maxillary Expansion - 2016 - American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedicsplayer osamaNo ratings yet

- AJODO-2013 (First Author) 143 5 A14 PDFDocument1 pageAJODO-2013 (First Author) 143 5 A14 PDFplayer osamaNo ratings yet

- AJODO-2013 (First Author) 143 5 A10Document1 pageAJODO-2013 (First Author) 143 5 A10player osamaNo ratings yet

- Boneceramic Graft Regenerates Alveolar Defects But Slows Orthodontic Tooth Movement With Less Root ResorptionDocument10 pagesBoneceramic Graft Regenerates Alveolar Defects But Slows Orthodontic Tooth Movement With Less Root Resorptionplayer osamaNo ratings yet

- AJODO-2013 143 4 446 KaramiDocument1 pageAJODO-2013 143 4 446 Karamiplayer osamaNo ratings yet

- Bone and Cartilage Changes After Injection of Botulinum Toxin - 2016 - American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial OrthopedicsDocument1 pageBone and Cartilage Changes After Injection of Botulinum Toxin - 2016 - American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedicsplayer osamaNo ratings yet

- Letters To The Editor: Bone and Cartilage Changes After Injection of Botulinum ToxinDocument3 pagesLetters To The Editor: Bone and Cartilage Changes After Injection of Botulinum Toxinplayer osamaNo ratings yet

- "Facial Keys To Orthodontic Diagnosis and Treatment Planning Parts IDocument14 pages"Facial Keys To Orthodontic Diagnosis and Treatment Planning Parts ILeonardo Lamim80% (5)

- SDJ 3 2013Document61 pagesSDJ 3 2013player osamaNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Three Different Orthodontic Wires For Bonded Lingual Retainer FabricationDocument8 pagesComparison of Three Different Orthodontic Wires For Bonded Lingual Retainer Fabricationosama-alaliNo ratings yet

- AJODO-2013 (First Author) 143 5 752Document1 pageAJODO-2013 (First Author) 143 5 752player osamaNo ratings yet

- AJODO-2013 (First Author) 143 5 A2Document4 pagesAJODO-2013 (First Author) 143 5 A2player osamaNo ratings yet

- Zachrisson Am J Orthod 2011Document9 pagesZachrisson Am J Orthod 2011player osamaNo ratings yet

- PracticalTechforAchiev PDFDocument4 pagesPracticalTechforAchiev PDFosama-alaliNo ratings yet

- Princess Joy Placement and General Services vs. BinallaDocument2 pagesPrincess Joy Placement and General Services vs. Binallaapple_doctoleroNo ratings yet

- Volume Booster: YT-300 / YT-310 / YT-305 / YT-315 / YT-320Document1 pageVolume Booster: YT-300 / YT-310 / YT-305 / YT-315 / YT-320SeikatsukaiNo ratings yet

- Comparative Study of Different Varieties of Rice For Making Homemade Instant CoffeeDocument9 pagesComparative Study of Different Varieties of Rice For Making Homemade Instant CoffeeJhon Kyle RoblesNo ratings yet

- WaveLab - BUC Datasheet - Ku Band 80W 100WDocument4 pagesWaveLab - BUC Datasheet - Ku Band 80W 100WLeonNo ratings yet

- Carac Biogas FlamelessDocument7 pagesCarac Biogas FlamelessTaine EstevesNo ratings yet

- Algerian Carob Tree Products PDFDocument10 pagesAlgerian Carob Tree Products PDFStîngă DanielaNo ratings yet

- Substation Off Line and Hot Line CommissioningDocument3 pagesSubstation Off Line and Hot Line CommissioningMohammad JawadNo ratings yet

- ISO 27001 MindmapsDocument6 pagesISO 27001 MindmapsYagnesh VyasNo ratings yet

- Reading ComprehensionDocument9 pagesReading Comprehensionxifres i lletres xifres i lletres100% (1)

- ACS AMI FacilitatorDocument21 pagesACS AMI FacilitatorPaul Zantua57% (7)

- SCRAPBOOKDocument19 pagesSCRAPBOOKJulius Michael GuintoNo ratings yet

- Physical, Biology and Chemical Environment: Its Effect On Ecology and Human HealthDocument24 pagesPhysical, Biology and Chemical Environment: Its Effect On Ecology and Human Health0395No ratings yet

- Ketone OxidationDocument20 pagesKetone OxidationNgurah MahasviraNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Designing Relative Strength ProgramsDocument35 pagesFundamentals of Designing Relative Strength ProgramsFlorian WolfNo ratings yet

- Problem 21-02 Wright Company Spreadsheet For The Statement of Cash Flows Dec. 31 Changes Dec. 31 2020 Debits Credits 2021 Balance SheetDocument17 pagesProblem 21-02 Wright Company Spreadsheet For The Statement of Cash Flows Dec. 31 Changes Dec. 31 2020 Debits Credits 2021 Balance SheetVishal P RaoNo ratings yet

- Static Var CompensatorDocument12 pagesStatic Var CompensatorBengal Gaming100% (1)

- 7-Day Indian Keto Diet Plan & Recipes For Weight LossDocument43 pages7-Day Indian Keto Diet Plan & Recipes For Weight LossachusanachuNo ratings yet

- 1-A Colored Substance That Is Spread Over A Surface and Dries To Leave A Thin Decorative or Protective Coating. Decorative or Protective CoatingDocument60 pages1-A Colored Substance That Is Spread Over A Surface and Dries To Leave A Thin Decorative or Protective Coating. Decorative or Protective Coatingjoselito lacuarinNo ratings yet

- Microcosmic Orbit Breath Awareness and Meditation Process: For Enhanced Reproductive Health, An Ancient Taoist MeditationDocument1 pageMicrocosmic Orbit Breath Awareness and Meditation Process: For Enhanced Reproductive Health, An Ancient Taoist MeditationSaimon S.M.No ratings yet

- Professional DevelopmentDocument1 pageProfessional Developmentapi-488745276No ratings yet

- Paper - Impact of Rapid Urbanization On Agricultural LandsDocument10 pagesPaper - Impact of Rapid Urbanization On Agricultural LandsKosar Jabeen100% (1)

- Climate Responsive ArchitectureDocument32 pagesClimate Responsive ArchitectureNikhila CherughattuNo ratings yet

- 1.ar-315 BC&BL Lighting & IlluminationDocument28 pages1.ar-315 BC&BL Lighting & IlluminationUsha Sri GNo ratings yet

- The Four Aspects of Food CostDocument12 pagesThe Four Aspects of Food CostMukti UtamaNo ratings yet

- Amp-Eng Anger Management ProfileDocument6 pagesAmp-Eng Anger Management Profileminodora100% (1)

- Internship-Plan BSBA FInalDocument2 pagesInternship-Plan BSBA FInalMark Altre100% (1)

- Laboratory Manual For Microbiology Fundamentals A Clinical Approach 4Th Edition Susan Finazzo Full ChapterDocument51 pagesLaboratory Manual For Microbiology Fundamentals A Clinical Approach 4Th Edition Susan Finazzo Full Chapterlinda.ferguson121100% (7)

- Paraffin Wax Deposition: (The Challenges Associated and Mitigation Techniques, A Review)Document8 pagesParaffin Wax Deposition: (The Challenges Associated and Mitigation Techniques, A Review)Jit MukherheeNo ratings yet

- Nath Bio-Genes at Inflection Point-2Document9 pagesNath Bio-Genes at Inflection Point-2vinodtiwari808754No ratings yet

- Elecsys T4: Cobas e 411 Cobas e 601 Cobas e 602 English System InformationDocument5 pagesElecsys T4: Cobas e 411 Cobas e 601 Cobas e 602 English System InformationIsmael CulquiNo ratings yet