Professional Documents

Culture Documents

IJED Lobo Scopin Barbosa Hirata

Uploaded by

Catia Sofia A POriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

IJED Lobo Scopin Barbosa Hirata

Uploaded by

Catia Sofia A PCopyright:

Available Formats

Clinical Research

Periodontal considerations for

adhesive ceramic dental restorations:

key points to avoid gingival problems

Maristela Lobo, DDS, MsC, PhD

Professor of Advanced Program in Implant and Esthetic Dentistry, SENAC University,

Sao Paulo, Brazil

Oswaldo Scopin de Andrade, DDS, MSc, PhD

Director of Advanced Program in Implant and Esthetic Dentistry, SENAC University,

Sao Paulo, Brazil

João Malta Barbosa, DDS, MSc

Prosthodontist, Department of Oral Rehabilitation, Implantology Institute, Lisbon, Portugal

Volunteer Researcher, Department of Biomaterials and Biomimetics,

New York University College of Dentistry, New York, NY, USA

Ronaldo Hirata, DDS, MsC, PhD

Assistant Professor of Biomaterials, New York University College of Dentistry, New York, NY, USA

Correspondence to: Dr Maristela Maia Lobo

Rua Ministro Gabriel de Resende Passos, 500, Cj 1010, Moema São Paulo SP, Brazil;

Tel: +55 11 5051-3534/+55 11 9 9447-7436; Email: maristelalobo@me.com

2 | The International Journal of Esthetic Dentistry | Volume 14 | Number 4 | Winter 2019

Lobo et al

Abstract tions, regardless of their thickness, and to reinforce

the importance of each step to ensure the success

The stability and health of the periodontal tissues and longevity of the treatment from a periodontal

should be a common goal for all dental care providers standpoint. This article reviews the fundamentals of

with regard to natural or restored teeth as well as im- the periodontics that relate directly or indirectly to ad-

plant-supported restorations or any other type of hesive ceramic dental restorations, and also addresses

prosthesis. The objective of this study was to address their clinical relevance.

the key aspects to be respected when executing ad-

hesive oral rehabilitations involving ceramic restora (Int J Esthet Dent 2019;14:2–15)

The International Journal of Esthetic Dentistry | Volume 14 | Number 4 | Winter 2019 | 3

Clinical Research

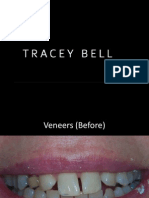

Fig 1 (a to c) tooth loss.2,3 The recurrence of these clinic-

Recurrent gingivitis al scenarios may indicate that there has not

associated with

been enough commitment to periodontal

indirect restorations.

health by some dental professionals. It

therefore seems pertinent to reinforce the

importance of the commitment to health,

function, and esthetics, in that order. These

a goals are fundamental to obtain the desired

longevity and stability for any provided treat-

ment.

The term ‘contact lenses’ has been in-

creasingly used worldwide by the dental

community as a marketing term to describe

thin porcelain veneers that aim to improve

smile esthetics without dental preparation

(no-prep veneers). However, clinical reality

b has shown that only very few and highly

specific situations make it possible to avoid

the need for dental preparation while pro-

viding the space required for the restorative

material. In most clinical situations, the

need for a ceramic restoration is highly

subjective, and the request for such a treat-

ment by a patient may be comparable with

the desire to acquire a fashion/trendy item.

c When a patient demands a treatment that

conflicts with the clinician’s recommenda-

tion, the clinician should educate the pa-

tient and explain the indications and contra-

indications of such a treatment so that a

Introduction fully informed decision can be taken. De-

spite this ideal approach, unfortunately

A healthy periodontium should be the ulti- some clinicians seem more interested in

mate goal for all professionals involved with performing the treatment regardless of its

comprehensive oral rehabilitations because clinical indications, which leads to an in-

the health and stability of the periodon- crease in overtreatments. As a conse-

tal-restorative transition is key to treatment quence, the rate of retreatments of recently

success.1 Unfortunately, frequent adhesive performed adhesive esthetic rehabilitations

rehabilitation failures occur because this due to periodontal compromises is also on

clear goal for prosthetic rehabilitations is the rise. With that, the patient enters, often

not sufficiently respected. These failures oc- at an early age, the so called ‘restorative cy-

cur as recurrent gingivitis, localized or gen- cle,’ which sooner or later culminates in

eralized, or as irreversible periodontal at- tooth loss.4

tachment loss through gingival recession Most failures occur from what can only

and/or periodontal pocket formation that, be seen as a lack of knowledge of the inter-

in extreme cases, may ultimately lead to action between restorative dentistry and

4 | The International Journal of Esthetic Dentistry | Volume 14 | Number 4 | Winter 2019

Lobo et al

Fig 2 (a to d) Classic

signs of inflammation

(flushing, heat, tumor,

exudate, and pain).

a b

c d

periodontics, sometimes combined with a avoiding overlapping or misadaptations

poor or careless technical execution (Figs 1 that may promote plaque accumulation

and 2). An important factor that seems to and/or affect the ideal food trajectory.8

potentiate these negative outcomes is the 3. Avoid excessive manipulation of the gin-

presence of a thin/festooned periodontal gival margin with retraction cords, he-

biotype, described to present an increased mostatic agents, clamps, impression ma-

risk of gingival margin instability and conse- terials, and inadequate instrumentation.9

quent esthetic compromise.5 Patients with 4. Strive for excellent marginal adaptation,

delicate biotypes are more prone to devel- with or without tooth preparation.

oping gingival margin recession as a result 5. Avoid the contact of impregnated mater-

of a temporary or prolonged periodontal ials during cementation (retraction cords

aggression, often seen in adhesive rehabili- and an excess of adhesive cement).

tations with ‘contact lenses.’ Therefore, it is 6. Ensure adequate sealing and adaptation

important to recall patients presenting deli- of the restoration in relation to the dental

cate biotypes that require extra care when substrate, avoiding misadaptations, voids,

managing soft tissues for restorative pur- and/or spaces susceptible to subsequent

poses (ie, it can be stated that periodontal plaque accumulation.10

tissues require clinical respect).

Periodontal clinical respect means to: The objective of this article is to address

1. Preserve the biological space, avoiding the key factors or ‘rules’ to be respected

the direct contact of the restorative ma- during the execution of adhesive ceramic

terials with the junctional epithelium (JE) restorations, regardless of their thickness,

and/or the connective tissue (CT) attach- and to reinforce the importance of each

ment.6,7 step to ensure the success and longevity of

2. Optimize the emergence profile and the the treatment from a periodontal stand-

cervical contour of the restoration by point.

The International Journal of Esthetic Dentistry | Volume 14 | Number 4 | Winter 2019 | 5

Clinical Research

Fig 3 (a to c) A the external and internal environments so

biological seal is as to prevent microorganisms from pene-

provided by the

trating the systemic blood stream. This seal

combined functions

of the junctional

exists through the combined functions of

epithelium and the the JE (epithelial seal) and the CT insertion

connective tissue (connective seal), which in combination

insertion, which in form the so-called biological space11-13

combination form a (Fig 3).

the biological space.

The first line of periodontal defense

consists of the oral epithelium (OE), partic-

Connective sealing ularly the inserted gingiva. This epithelial

Epithelial sealing

Gingival sealing

layer is stratified and keratinized as well as

impermeable and resistant to mechanical,

chemical, and bacterial aggressors.14 It is

considered to be part of the protective

periodontium as it plays a role in protecting

b the more internal organic layer – the CT –

from coming into contact with external

agents. Like other epithelial tissues, the

periodontal epithelium exhibits little inter-

stitial space, with its constituting cells very

close to each other and with few to no

blood vessels. Therefore, the nutrition of

this outer layer is provided by the underly-

ing CT through the basal layer of the epi-

c thelium. Often, with the goal of increasing

the area of nutrition, the epithelium can

project crests toward the inner CT that can

increase in number and size in the pres-

ence of inflammatory processes.15

Rule 1: The biological equilibrium Due to the dual environment (external

of prosthetic/periodontal transi- and internal) in which a tooth exists, the OE

tion determines the success and invaginates toward the tooth surface to

longevity of the treatment form a sulcus. This sulcular epithelium (SE)

is less keratinized and has characteristics

For the majority of mammals, teeth are ar- similar to those of the OE, with a superficial

ticulated organs. This imposes an anatomi- layer of keratin. This characteristic allows it

cal challenge to the organism’s defense to seal the internal and external environ-

system: one third of the tooth is exposed in ments and therefore represents the primary

the oral cavity, in contact with the saliva line of periodontal protection.16 On average,

and diverse microorganisms, and the re- it is 0.7 mm long in the vestibular surface

maining two thirds are inserted within the and 1.0 mm long in the interproximal sur-

bony structure of the alveolar process. face of the anterior teeth11 (Fig 3). It is clini-

Therefore, an efficient and reliable bio- cally important to recall that the SE can

logical seal is essential to maintain a bio- only be evaluated histologically (eg, it is not

logical and ecological balance between possible to perform a probing evaluation).

6 | The International Journal of Esthetic Dentistry | Volume 14 | Number 4 | Winter 2019

Lobo et al

However, it can be assumed that, as this is a surement should not be used to define

transition tissue, it will present much vari- how far the probe can penetrate into the

ability among different individuals and gingival sulcus under pressure, since this

should be considered the anatomical and action will likely invade the JE.

histological limit for the intracrevicular level 3. The restorative materials currently avail-

of a restorative margin preparation. able for restorative adhesive dentistry are

A second epithelial layer – the JE – lies biotolerable but not biocompatible. This

underneath the SE and presents distinct his- means that they should not remain in

tological characteristics compared with the contact with the JE because an anti-

OE and the gingival epithelium. The JE is gen-antibody reaction may occur.6,7 Ideal-

not keratinized and is therefore permeable, ly, these materials should be bioactive,

allowing for fluid exchange between the in- stimulating cellular proliferation and ad-

ternal and external environments. The JE hesion, which is similar to what happens

only presents two layers of cells – the exter- in oral and orthopedic implantology18

nal lamina (EL) and the internal basal lamina with materials such as titanium and zirco-

(IBL) – with only the former providing tissue nia as well as polymers such as polyether

stability and sealing by adhering weakly to etherketone (PEEK).19 Even implant-sup-

the surface of the enamel through hemides- ported restorations, being transmucosal

mosomes.16 It is through the JE that the hu- in nature, have been considered by some

moral and cellular defenses come into con- authors to invade the biological space.20

tact with external agents, as in cases of

tissue inflammation. Additionally, the JE is From the approximate level of the cemento-

responsible for the secretion of the gingival enamel junction (CEJ), the JE gives way api-

crevicular fluid. cally to a CT insertion. The CT forms a union

In cases of lesioning (common during through connective fibers with the root ce-

periodontal probing and/or procedures such mentum. This connection is real, since the

as prophylaxis and the insertion of a retrac- tooth end of these fibers is mineralized and

tion cord for impression, amongst others), anchors in the cement surface (the Sharpey’s

the JE is able to regenerate quickly (in 48 h) fibers). From this mineralized origin they di-

unlike the other epithelial tissues.17 rect toward the CT of the gingival margin,

The following are some critical clinical being part of its structure. From a sealing

aspects regarding the JE: perspective, an important function of the

1. Being a permeable tissue, no restorative CT is to prevent apical migration of the JE,

material or debris resulting from clinical keeping the level of the gingival margin in

procedures should remain in contact position.15

with the JE due to the risk of inducing

transient or permanent gingival inflam- Rule 2: The excellence of the

mation. clinical execution is more determi-

2. The conventional periodontal probing nant than the selected restorative

performed with a Williams or North material

Carolina millimeter probe should be per-

formed with a slight digital pressure, Several factors should be observed to

since the depth of the clinical sulcus dif- achieve periodontal health in the vicinity of

fers from that of the gingival sulcus that a dental restoration, regardless of its extent

often encompasses a small or medium and the material used. The primary factor

portion of the JE. Thus, this clinical mea- relates to the vertical location of the tooth

The International Journal of Esthetic Dentistry | Volume 14 | Number 4 | Winter 2019 | 7

Clinical Research

Fig 4 (a) The and the adequate adaptation of the overlay-

purpose of any ing restoration (temporary or permanent) is

dental preparation is

paramount to achieving periodontal health.

to provide space for

the restorative

An inadequate dental preparation may re-

material. A tooth may sult in excessive restoration contouring, an

present a deficient inadequate emergence profile, an incorrect

coronal volume and occlusal design, and ultimately in functional

therefore not require a and esthetic failure.

preparation. (b) It is

It is important to recall that the purpose

important to position

the cervical and

of any dental preparation is to provide space

interproximal for the restorative material. In rare excep-

demarcation with an tions, a tooth may present a deficient coro-

average depth of 0.2 nal volume and therefore require no prepara

to 0.4 mm to avoid tion (Fig 4a). However, even in the case of a

cervical dentin

tooth with such characteristics, it is import-

exposure and ensure

an adequate

ant to plan for the position of the cervical

emergence profile. b and interproximal restorative limits of the

(c) Dental prepara future restoration. It is also important to plan

tions should ideally for its emergence profile in such a way that

be positioned 0.2 to a predictable adaptation in the restoration is

0.5 mm above the

achieved, avoiding possible periodontal

gingival margin, espe-

cially when the color

damage. This cervical and interproximal de-

of the substrate is marcation should be smooth, with an aver-

favorable. age depth of 0.2 to 0.4 mm to avoid cervical

dentin exposure (Fig 4b).

c According to Richter and Ueno,22 the

definition and excellence of the preparation

limit may be even more important than its

vertical level in relation to the free gingival

margin. Preferably, dental preparations

preparation limit. In this respect, two ele- should not be positioned within the gingival

ments should be considered: first, ensuring sulcus,21 ideally being 0.2 to 0.5 mm above

an appropriate distance for an adequate re- the gingival margin, especially when the

storative emergence profile; and second, color of the substrate is favorable (Fig 4c).

aiming whenever possible for a supragin- SupG preparations have various advantages

gival (SupG) or equigingival (EqG) restorative as they are more accessible during the exe-

limit. However, if a subgingival (SubG) limit is cution of several clinical procedures, includ-

unavoidable, the preparation limit should re- ing easier access and visualization during

main in contact with the SE (an imperme- preparation, facilitated impression or scan-

able tissue), penetrating a maximum of ning as well as for oral hygiene procedures

0.5 mm on the vestibular surface and and long-term maintenance.21,23

1.0 mm on the interproximal surfaces in re- Despite all the previous considerations,

lation to the free gingival margin.21 SubG preparations are justified in certain sit-

In addition to the vertical level of the uations:

preparation limit (SupG, EqG or SubG), the 1. Substrate discoloration (Fig 5).

overall excellence of the tooth preparation 2. Replacement of restorations that already

8 | The International Journal of Esthetic Dentistry | Volume 14 | Number 4 | Winter 2019

Lobo et al

Fig 5 (a to g)

Subgingival prepara

tions are justified in

situations of substrate

discoloration that

require total

coverage of the

tooth by the

a b restoration. Figure (e)

shows that some-

times it is important

to restore the

discolored substrate

with direct opaque

composite resin prior

to cementation.

c d

e f

The International Journal of Esthetic Dentistry | Volume 14 | Number 4 | Winter 2019 | 9

Clinical Research

Fig 6 (a to e)

Subgingival prepara

tions are also justified

to replace restor-

ations that already

present with

subgingival prepara

tions or restorations.

a b

c d

present with SubG preparations or res- In the above cases, there is a justifiable need

torations (Fig 6). to extend the preparation within the sulcus.

3. For SubG caries. However, the position of the JE must be fully

4. For diastemas that require a suitable respected, and direct contact of the restora-

proximal emergence profile to optimize tive material should be limited to the SE,

the position of the interdental papilla which is keratinized and impermeable. Since

(Fig 7). the SE is a tissue with unique characteristics

10 | The International Journal of Esthetic Dentistry | Volume 14 | Number 4 | Winter 2019

Lobo et al

that are clinically indefinable, parameters Fig 7 (a to c)

such as probing should not be used in the Diastemas that

require a suitable

decision-making process regarding how

proximal emergence

much a particular sulcus can be penetrated profile to optimize

in relation to the free gingival margin. It is im- the position of the

portant to consider that in the vast majority interdental papilla

of individuals, the gingival sulcus (or SE) has a demand subgingival

perennial distance, being a transitional epi- a margin preparations.

thelium between the OE and the JE.11

From an evidenced-based dentistry (EBD)

standpoint, some of the previously men-

tioned clinical considerations regarding the

relational dental preparation limit and the

periodontal tissues have already gained con-

sensus with the scientific community, these

being:

1. The JE is part of the biological space and b

is permeable. Therefore, any restorative

material that contacts its surface will

have an almost direct contact with the

underlying CT and will generate varying

levels of inflammation.24

2. The restorative materials available for

dental restorations are only biotolerable,

not biocompatible or bioactive.25 All re-

storative materials (direct or indirect, c

temporary or final) can generate anti-

gen-antibody reactions and should not

come into direct contact with the JE,

with the exception of titanium, zirconia,

and PEEK.6,19

3. The vast majority of patients present with terms of respecting the periodontal in-

thin/festooned periodontal biotypes, volvement. These clinical strategies should

which increases the risk of periodontal translate into sufficient invasiveness, ade-

harm, gingival margin stability, and a re- quate instrumentation, EBD clinical proto-

sultant esthetic compromise.5 Depend- cols, and the employment of premium ma-

ing on the periodontal biotype, different terials. Well-adjusted provisional and/or

clinical and histological responses may final restorations directly affect the final re-

arise from a biological space violation: storative outcome as well as the health of

periodontal pocket formation, gingival the adjacent tissues. An in-depth know

recession, and/or apical migration of the ledge of the histoanatomy of the periodon-

dentogingival complex.26 tal tissues and an awareness of how certain

prosthetic procedures can impact perio

In summary, it is important to define clinic- dontal health are prerequisites for any clin-

al strategies, not only regarding the preser- ician involved in adhesive restorative den-

vation of hard dental tissues but also in tistry.

The International Journal of Esthetic Dentistry | Volume 14 | Number 4 | Winter 2019 | 11

Clinical Research

a b

Fig 8 (a and b) In thin/festooned periodontal biotypes, the teeth usually present a more pronounced vestibular convexity, located between

the middle and cervical thirds of the crown. This seems to alleviate the direct impact of food on the periodontium. Clinicians should be

careful not to cause overcontouring in cases of no-prep as this could lead to periodontal damage.

Rule 3: The periodontal biotype is tibular surface. This biotype is less sensitive

fundamental to define the vestibu- to dental procedures and may allow for cer-

lar convexity of the restoration tain clinical indelicacies without resulting in

permanent periodontal damage.28 On the

The periodontal biotype is a factor of para- other hand, this biotype appears more

mount importance for the esthetic risk as- prone to developing periodontal pockets in

sessment in restorative dentistry and its ob- the presence of inflammation, which may

servance is fundamental to selecting the mask the evolution of irreversible tissue

adequate treatment sequence and proto- loss.15

cols, including preparation, impression pro-

cedures, temporization, and cementation. Rule 4: A respectful transition

The periodontal biotype is directly related to between the periodontium and

the convexity of the vestibular surface of restoration increases the consis-

natural teeth, which plays an important role tency of the clinical results

in directing bolus trajectory during mastica-

tion and promoting proper stimulation and The tooth-restoration-periodontium inter-

toning of the gingival margins.27 face should be optimized, with the aim of

When the periodontium is thin/fes- achieving harmony between tissues that are

tooned, the teeth usually present a more very different from an anatomical and bio-

pronoun ced vestibular convexity, located logical standpoint. The position, preparation

between the middle and cervical thirds of limit, emergence profile in combination

the crown, which seems to alleviate the di- with the vestibular contour of the ceramic

rect impact of food on the periodontium. restoration, and establishment of an “area of

Clinicians should be careful not to cause adhesive continuity” (AAC)29 allow for an ad-

overcontouring in cases of no-prep as this equate perio-restorative integration, facili-

could lead to periodontal damage (Fig 8). tating plaque control in the cervical region

The flat and thick periodontium is typically (Fig 9). The AAC, forming a hybrid interface

more mechanically resistant and is generally of different structures that have been bond-

associated with teeth that have a flatter ves- ed together, results from the correct adap-

12 | The International Journal of Esthetic Dentistry | Volume 14 | Number 4 | Winter 2019

Lobo et al

tation between them, so that there are no

discrepancies that promote plaque accu-

mulation.

Not only the clinician but also the dental

technician/ceramist must be knowledge-

able about the biological implications of the

indirect restoration being produced in order

to ensure an adequate finishing and adapta-

tion of the restoration margin as well as an

appropriate emergence profile. The dental

technician must observe the position of the

soft tissues and respect the biological space a

in no-prep cases, participating together with

the clinician in the material selection pro-

cess for each particular situation.

Finally, care during the bonding of ce-

ramic dental restorations is fundamental to

attaining a successful perio-restorative in-

terface connection. Attention should be

paid to the choice of the composite resin

cement viscosity and the adhesive protocol,

which must be respected and followed me-

ticulously. The use of gingival retraction

cords should be restricted to cases where

complete hemostasis is not attainable in the b

JE, allowing for the passage of crevicular

fluid from the internal to the external envi-

ronment. In these cases, a thinner retraction

cord (No. 000), impregnated with an alumi-

num-based hemostatic solution (to avoid

subsequent spotting) should be selected

and positioned at the level of the JE (ie, it

should not be apparent). Retraction cords

should also be used in cases of SubG prep-

arations, since mechanical separation is re-

quired. The shorter the time the retraction

cord is kept in position, the better for the

health of the periodontium. On the other

hand, there is no need to use gingival re-

traction cords in the case of a SupG prepara

tion with healthy periodontal tissues. c

While absolute isolation (with rubber

dam) is fundamental to control humidity, it

Fig 9 (a to c) The position, preparation limit, and emergence profile in combina-

may be deleterious to the gingival margin tion with the vestibular contour of the ceramic restoration as well as the

during cementation.30 Alternatively, this establishment of an area of adhesive continuity (AAC) allow for an adequate

control could be achieved with relative iso- perio-restorative integration, facilitating plaque control in the cervical region.

The International Journal of Esthetic Dentistry | Volume 14 | Number 4 | Winter 2019 | 13

Clinical Research

lation through the use of saliva absorbents A follow-up appointment should be

and lip retractors or by utilizing modified ab- scheduled to assure that the periodontium

solute isolation. in the vicinity of the new restoration pres-

Another important aspect is the sealing ents a healthy appearance, with no signs of

of the restoration and the flow of the ce- inflammation, pain, heat, redness, tumor,

ment. During this procedure, the clinician and/or exudate.

should be careful to prevent the formation

of voids that occur when air is trapped be- Final considerations

tween the restoration and the tooth surface.

Once the restoration is fully seated, the ex- Many factors can be related to the perio

cessive cement should be carefully re- dontal success of an adhesive dental reha-

moved using appropriate instrumentation, bilitation. Although techniques and mater-

brushes, and floss, ideally under magnifica- ials will change and evolve over the years

tion. Light curing only the central area of the and new tools will emerge, the biology will

restoration through the use of collimating not change. The clinician and dental techni-

tips on the photopolymerization device fa- cian/ceramist are obliged to keep abreast of

cilitates the complete removal of the resin the latest developments and constantly ex-

cement. This helps to ensure that there is pand their knowledge of the biological be-

no excess material before the final polymer- havior of the periodontal and dental tissues

ization of the resin cement at the AAC. in relation to the techniques and materials

In cases of multiple restorations, the gin- used for oral rehabilitation, so that by res

gival retraction cords (if indicated) should be pecting these tissues the success and long

removed only after complete photopoly- evity of the restoration may be fully achieved.

merization of all the elements. After this has The stability and health of the periodontal

been completed, marginal finishing should tissues should be a common goal for all

take place, for which No. 12 and/or No. 12D dental care providers with regard to natural

scalpel blades, prophylactic strips, dental or restored teeth as well as implant-support-

floss, and in some cases rubber cups with ed restorations or any other type of pros-

fine polishing pastes may be used. thesis.

14 | The International Journal of Esthetic Dentistry | Volume 14 | Number 4 | Winter 2019

Lobo et al

References

1. Gracis S, Fradeani M, Celletti R, Bracchetti 11. Gargiulo AW, Wentz FM, Orban B. Di- 21. Schätzle M, Land NP, Anerud A, Boysen

G. Biological integration of aesthetic res- mension and relations of the dentogingival H, Bürgin W, Löe H. The influence of

torations: factors influencing appearance junction in humans. J Periodontol 1961;32: margins of restorations of the periodontal

and long-term success. Periodontol 2000 261–267. tissues over 26 years. J Clin Periodontol

2001;27:29–44. 12. Stern IB. Current concepts of the 2001;28:57–64.

2. Newcomb GM. The relationship between dentogingival junction: the epithelial and 22. Richter WA, Ueno H. Relationship of

the location of subgingival crown margins connective tissue attachments to the tooth. crown margin placement to gingival inflam-

and gingival inflammation. J Periodontol J Periodontol 1981;52:465–476. mation. J Prosthet Dent 1973;30:156–161.

1974;45:151–154. 13. Nevins M, Skurow HM. The intracrevic- 23. Christensen GJ. Marginal fit of gold inlay

3. Schroeder HE, Listgarten MA. The gingival ular restorative margin, the biologic width, castings. J Prosthet Dent 1966;16:297–305.

tissues: the architecture of periodontal pro- and the maintenance of the gingival margin. 24. Ten Cate AR. The role of epithelium in

tection. Periodontol 2000 1997;13:91–120. Int J Periodontol Restorative Dent 1984;4: the development, structure and function

4. Cohen LC, Dahlen G, Escobar A, Fejer- 30–49. of the tissues of tooth support. Oral Dis

skov O, Johnson NW, Manji F. Dentistry in 14. Lange D, Schroeder HE. Cytochemistry 1996;2:55–62.

crisis: time to change. La Cascada Declara- and ultrastructure of gingival sulcus cells. 25. Werner S, Huck O, Frisch B, et al. The

tion. Aust Dent J 2017;62:258–260. Helv Odontol Acta 1971;15(suppl 6):65–86. effect of microstructured surfaces and lami-

5. Fischer KR, Künzlberger A, Donos N, Fickl 15. Pöllänen MT, Laine MA, Ihalin R, Uitto VJ. nin-derived peptide coatings on soft tissue

S, Friedmann A. Gingival biotype revisited Host-bacteria crosstalk at the dentogingival interactions with titanium dental implants.

– novel classification and assessment tool. junction [epub ahead of print 26 July 2012]. Biomaterials 2009;30:2291–2301.

Clin Oral Investig 2018;22:443–448. Int J Dent 2012;2012:821383. 26. Maynard JG Jr, Wilson RD. Physiologic

6. Messer RL, Lockwood PE, Wataha JC, 16. Nakamura M. Histological and immu- dimensions of the periodontium significant

Lewis JB, Norris S, Bouillaguet S. In vitro cy- nological characteristics of the junctional to the restorative dentist. J Periodontol

totoxicity of traditional versus contemporary epithelium. Jpn Dent Sci Rev 2018;54: 1979;50:170–174.

dental ceramics. J Prosthet Dent 2003;90: 59–65. 27. Kao RT, Pasquinelli K. Thick vs. thin gin-

452–458. 17. Kinumatsu T, Hashimoto S, Muramatsu gival tissue: a key determinant in tissue re-

7. Raffaelli L, Rossi Iommetti P, Piccioni E, et T, et al. Involvement of laminin and integrins sponse to disease and restorative treatment.

al. Growth, viability, adhesion potential, and in adhesion and migration of junctional J Calif Dent Assoc 2002;30:521–526.

fibronectin expression in fibroblasts cultured epithelium cells. J Periodontal Res 2009;44: 28. Block MS. Management of the facial gin-

on zirconia or feldspathic ceramics in vitro. 13–20. gival margin. Dent Clin North Am 2011;55:

J Biomed Mater Res A 2008;86:959–968. 18. Rompen E, Domken O, Degidi M, 663–671.

8. Padbury A Jr, Eber R, Wang HL. Interac- Pontes AE, Piattelli A. The effect of material 29. Scopin de Andrade OS, Borges GA, Ky-

tions between the gingiva and the margin characteristics, of surface topography and rillos M, Moreira M, Calicchio L, Correr-So-

of restorations. J Clin Periodontol 2003;30: of implant components and connections brinho L. The Area of Adhesive Continuity:

379–385. on soft tissue integration: a literature review. A New Concept for Bonded Ceramic Res-

9. Lang NP, Kiel RA, Anderhalden K. Clinical Clin Oral Implants Res 2006;17(suppl 2): torations. Quintessence Dental Technology

and microbiological effects of subgingival 55–67. 2013;36:9–26.

restorations with overhanging or clinically 19. Schwitalla A, Müller WD. PEEK dental 30. Daudt E, Lopes GC, Vieira LC. Does

perfect margins. J Clin Periodontol 1983;10: implants: a review of the literature. J Oral operatory field isolation influence the per-

563–578. Implantol 2013;39:743–749. formance of direct adhesive restorations?

10. Dragoo MR, Williams GB. Periodontal 20. Schupbach P, Glauser R. The defense J Adhes Dent 2013;15:27–32.

tissue reactions to restorative procedures. architecture of the human periimplant mu-

Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 1981;1: cosa: a histological study. J Prosthet Dent

8–23. 2007;97(6 suppl):S15–S25.

The International Journal of Esthetic Dentistry | Volume 14 | Number 4 | Winter 2019 | 15

You might also like

- Matrix Impression TechniqueDocument9 pagesMatrix Impression TechniqueAnupriya SinghNo ratings yet

- DSD PDF Photo - Video ProtocolDocument43 pagesDSD PDF Photo - Video ProtocolCésar Mejía GualleNo ratings yet

- Deliperi S - PPAD - 2005 PDFDocument9 pagesDeliperi S - PPAD - 2005 PDFAlfredo PortocarreroNo ratings yet

- Current Concepts in Dental ImplantologyDocument274 pagesCurrent Concepts in Dental ImplantologyClaudiu LefterNo ratings yet

- All Ceramic 5p PDFDocument6 pagesAll Ceramic 5p PDFWiwin Nuril FalahNo ratings yet

- Bio Emulation Edinburgh EventsDocument8 pagesBio Emulation Edinburgh EventsAing MaungNo ratings yet

- Afraccion PDFDocument9 pagesAfraccion PDFzayraNo ratings yet

- Anesthesia in Endodontics - Facts & Myths PDFDocument6 pagesAnesthesia in Endodontics - Facts & Myths PDFVioleta BotnariNo ratings yet

- The International Journal of Periodontics & Restorative DentistryDocument10 pagesThe International Journal of Periodontics & Restorative Dentistrykevin1678No ratings yet

- 27-2 Summer 2011 PDFDocument132 pages27-2 Summer 2011 PDFBJ VeuxNo ratings yet

- Types of CrownsDocument6 pagesTypes of CrownsFa FaNo ratings yet

- The Need For Simplification: Aesthetics in One Shot?Document3 pagesThe Need For Simplification: Aesthetics in One Shot?Margaretha Yessi BudionoNo ratings yet

- Esthetic Technique: Crown Considerations, Preparations, and Material Selection For Esthetic Metal-Ceramic RestorationsDocument16 pagesEsthetic Technique: Crown Considerations, Preparations, and Material Selection For Esthetic Metal-Ceramic RestorationsAyu Nur A'IniNo ratings yet

- Develop Lingual OrtoDocument68 pagesDevelop Lingual OrtoOrtodonti UnhasNo ratings yet

- Ceramic Bonded Inlays-Onlays: Case SeriesDocument8 pagesCeramic Bonded Inlays-Onlays: Case SeriesInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Noncarious Cervical Lesions As Abfraction Etiology Diagnosis and Treatmentmodalities of Lesions A Review Article 2161 1122 1000438 PDFDocument6 pagesNoncarious Cervical Lesions As Abfraction Etiology Diagnosis and Treatmentmodalities of Lesions A Review Article 2161 1122 1000438 PDFFaniaNo ratings yet

- Biologic Interfaces in Esthetic Dentistry Part IIDocument27 pagesBiologic Interfaces in Esthetic Dentistry Part IINoelia MadrizNo ratings yet

- Journal 072019 PDFDocument60 pagesJournal 072019 PDFestefyNo ratings yet

- Biologic Width and Its Importance in DentistryDocument7 pagesBiologic Width and Its Importance in DentistryPremshith CpNo ratings yet

- 10 TIPS On Posterior Direct Restoration in Daily FlowDocument11 pages10 TIPS On Posterior Direct Restoration in Daily FlowMaria Jose Ortega MedinaNo ratings yet

- Additive Contour of Porcelain Veneers A Key Element in Enamel PreservationDocument13 pagesAdditive Contour of Porcelain Veneers A Key Element in Enamel PreservationPablo BenitezNo ratings yet

- Vertical Ridge Augmentation and Soft Tissue Reconstruction of The Anterior Atrophic Maxillae - Urban2017Document12 pagesVertical Ridge Augmentation and Soft Tissue Reconstruction of The Anterior Atrophic Maxillae - Urban2017Claudio GuzmanNo ratings yet

- 2 - Evaluation of Bond Strength and Thickness of Adhesive Layer According To The Techniques of Applying Adhesives in Composite Resin RestorationsDocument7 pages2 - Evaluation of Bond Strength and Thickness of Adhesive Layer According To The Techniques of Applying Adhesives in Composite Resin RestorationskochikaghochiNo ratings yet

- Dental Anatomy FactsDocument10 pagesDental Anatomy FactsGhee MoralesNo ratings yet

- The New Science of Strong TeethDocument4 pagesThe New Science of Strong TeethThe Bioclear ClinicNo ratings yet

- Pulp Dentin BiologyDocument21 pagesPulp Dentin BiologyCristiane VazNo ratings yet

- Composite in Everyday Practice - How To Choose The Right Material and Simplify Application Techniques in The Anterior TeethDocument24 pagesComposite in Everyday Practice - How To Choose The Right Material and Simplify Application Techniques in The Anterior TeethTania Azuara100% (1)

- The American Journal of Esthetic PDFDocument77 pagesThe American Journal of Esthetic PDFZaira Angélica Hernández JiménezNo ratings yet

- Cosmetic Dentistry CSD 2013Document3 pagesCosmetic Dentistry CSD 2013Rodrigo Daniel Vela RiveraNo ratings yet

- Principles in Esthetis DentistryDocument82 pagesPrinciples in Esthetis DentistryMaria0% (1)

- Eur JEsthet Dent 2013 MeyenbergDocument97 pagesEur JEsthet Dent 2013 Meyenbergsoma kiranNo ratings yet

- Color and Shade Management in Esthetic DentistryDocument9 pagesColor and Shade Management in Esthetic DentistryPaula Francisca MoragaNo ratings yet

- Course 2 Jordi Anna 2018 Brochure 1Document6 pagesCourse 2 Jordi Anna 2018 Brochure 1mhd ssaghNo ratings yet

- Endo Crown: An Approach For Restoring Endodontically Treated Right Mandibular First Molars With Large Coronal Destruction - A Case ReportDocument7 pagesEndo Crown: An Approach For Restoring Endodontically Treated Right Mandibular First Molars With Large Coronal Destruction - A Case ReportIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Air Abrasion An Emerging Standard of CarDocument25 pagesAir Abrasion An Emerging Standard of CarValeriu IlincaNo ratings yet

- Cosmetic Dentistry PortfolioDocument50 pagesCosmetic Dentistry PortfoliotraceybellNo ratings yet

- Ceramics in Dentistry-Part I: Classes of MaterialsDocument6 pagesCeramics in Dentistry-Part I: Classes of MaterialsDilesh PradhanNo ratings yet

- Dentaltown 2018marchDocument113 pagesDentaltown 2018marchDanutz BalanNo ratings yet

- The Endocrown - A Different Type of All-Ceramic Reconstruction For Molars - JcdaDocument10 pagesThe Endocrown - A Different Type of All-Ceramic Reconstruction For Molars - Jcdaabcder1234No ratings yet

- Create beautiful smiles with nano-composite restorationsDocument1 pageCreate beautiful smiles with nano-composite restorationsRamandeep ChathaNo ratings yet

- Mclaren Smile AnalysisDocument15 pagesMclaren Smile AnalysisXavier Vargas PerezNo ratings yet

- Make Your Endo-Life Easier Using E-Connect S: AuthorDocument1 pageMake Your Endo-Life Easier Using E-Connect S: AuthorSaber AL ShargabiNo ratings yet

- Indications For All Ceramic RestorationsDocument6 pagesIndications For All Ceramic RestorationsNaji Z. ArandiNo ratings yet

- 322d68f0d808a43de4798d2c38a69eb6Document118 pages322d68f0d808a43de4798d2c38a69eb6AlyaefkageNo ratings yet

- Aesthetic Rehab Visagism ConceptDocument7 pagesAesthetic Rehab Visagism ConceptvaamdevaaNo ratings yet

- Maciej Zarow Metal Post and Core How To Improve Aesthetics Via WWW Styleitaliano OrgDocument27 pagesMaciej Zarow Metal Post and Core How To Improve Aesthetics Via WWW Styleitaliano OrgghfhfdghNo ratings yet

- The Dahl Concept Past Present and FutureDocument9 pagesThe Dahl Concept Past Present and FuturevivigaitanNo ratings yet

- Caries and Diabetes PDFDocument9 pagesCaries and Diabetes PDFMonica LunguNo ratings yet

- Deep Margin ElevationDocument1 pageDeep Margin ElevationJazNo ratings yet

- Speeds in DentistryDocument38 pagesSpeeds in DentistryRiya Jain100% (1)

- Proantibio 1Document52 pagesProantibio 1KraftchezNo ratings yet

- Crown and Post-Free Adhesive Restorations For Endodontically Treated Posterior Teeth From Direct Composite To Endocrowns-Stappert 2008Document8 pagesCrown and Post-Free Adhesive Restorations For Endodontically Treated Posterior Teeth From Direct Composite To Endocrowns-Stappert 2008Dan MPNo ratings yet

- Tooth WearDocument11 pagesTooth WearNaji Z. ArandiNo ratings yet

- An Overview of Tooth-BleachingDocument23 pagesAn Overview of Tooth-BleachingRolzilah RohaniNo ratings yet

- Cons VII Script 1 Bleaching Discolored TeethDocument19 pagesCons VII Script 1 Bleaching Discolored TeethPrince AhmedNo ratings yet

- Avoiding and Managing The Failure of Conventional Crowns and BridgesDocument6 pagesAvoiding and Managing The Failure of Conventional Crowns and BridgesAulia Maghfira Kusuma WardhaniNo ratings yet

- Oral Diagnosis and Treatment Planning: Part 5. Preventive and Treatment Planning For Dental CariesDocument10 pagesOral Diagnosis and Treatment Planning: Part 5. Preventive and Treatment Planning For Dental CariesalfredoibcNo ratings yet

- 1 Partially Edentulous Epidemiology Physiology and Terminology 1Document6 pages1 Partially Edentulous Epidemiology Physiology and Terminology 1Alexandra CastilloNo ratings yet

- Restorative RelationshipDocument6 pagesRestorative RelationshipDr Fahad and Associates Medical and dental clinicNo ratings yet

- A Review of Selected Dental Literature On Contemporary Provisional FPD S Treatment - Report of The Commmitee On Research in FPD S of The Academy of Fixed ProsthodonticsDocument24 pagesA Review of Selected Dental Literature On Contemporary Provisional FPD S Treatment - Report of The Commmitee On Research in FPD S of The Academy of Fixed ProsthodonticsLynda M. NaranjoNo ratings yet

- Treating Gummy Smile Using Digital Smile DesignDocument15 pagesTreating Gummy Smile Using Digital Smile DesignDewi Fitria AnugrahatiNo ratings yet

- Fphys 12 630859Document8 pagesFphys 12 630859Catia Sofia A PNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S107387461200093X MainDocument13 pages1 s2.0 S107387461200093X MainMr-Ton DrgNo ratings yet

- Impacts of Orthodontic Treatment On PeriDocument10 pagesImpacts of Orthodontic Treatment On PeriCatia Sofia A PNo ratings yet

- FasesTratamento LuísNunezDocument16 pagesFasesTratamento LuísNunezCatia Sofia A PNo ratings yet

- Principles and Technique: Antonino G. Secchi, DMD, MSDocument22 pagesPrinciples and Technique: Antonino G. Secchi, DMD, MSCatia Sofia A PNo ratings yet

- Complete Clinical Orthodontics: Treatment Mechanics: Part 1Document8 pagesComplete Clinical Orthodontics: Treatment Mechanics: Part 1Alan Ibarra MasterNo ratings yet

- Complete Clinical Orthodontic Treatment Mechanic by Dr. Antonino SecchiDocument4 pagesComplete Clinical Orthodontic Treatment Mechanic by Dr. Antonino Secchirimarsha nugrafitraNo ratings yet

- CCO Patient Diagnostic Sheet v6Document2 pagesCCO Patient Diagnostic Sheet v6Catia Sofia A P0% (1)

- Analise Dinamica Sorriso - Mudanças Com A IdadeDocument2 pagesAnalise Dinamica Sorriso - Mudanças Com A IdadeCatia Sofia A PNo ratings yet

- Complete Clinical Orthodontics: Treatment Mechanics: Part 2: Continuing EducationDocument5 pagesComplete Clinical Orthodontics: Treatment Mechanics: Part 2: Continuing EducationGissellePantojaNo ratings yet

- SDSCDocument11 pagesSDSCAndiUmarNo ratings yet

- Ceramic Veneers Contact Lenses and FragmentsDocument568 pagesCeramic Veneers Contact Lenses and FragmentsNoelia Madriz100% (7)

- La-Verdad-Sobre-Los-Sistemas-De-Brackets-De-Autoligado Nobrega SecchiDocument3 pagesLa-Verdad-Sobre-Los-Sistemas-De-Brackets-De-Autoligado Nobrega SecchiCatia Sofia A PNo ratings yet

- Principles of Smile Design-DemystifiedDocument25 pagesPrinciples of Smile Design-DemystifiedDiana SuărășanNo ratings yet

- JPD Barbosa Hirata Donovan CaramesDocument2 pagesJPD Barbosa Hirata Donovan CaramesCatia Sofia A PNo ratings yet

- Protocolos de Tratamento Sistema DamonDocument38 pagesProtocolos de Tratamento Sistema DamonCatia Sofia A PNo ratings yet

- MCQsDocument10 pagesMCQsraguchandra7527100% (1)

- Xerox Wc423 SMDocument600 pagesXerox Wc423 SMkerintNo ratings yet

- A-DEWS 2015 - Design Engineering in the Context of AsiaDocument568 pagesA-DEWS 2015 - Design Engineering in the Context of AsiaMukhlis Al QahharNo ratings yet

- Cystocentesis K4Document24 pagesCystocentesis K4Sze KhayNo ratings yet

- Hemisync ConcentrationDocument1 pageHemisync ConcentrationbsorinbNo ratings yet

- Product Lifecycle ManagementDocument27 pagesProduct Lifecycle ManagementDeepanshu ChawlaNo ratings yet

- 서초구 고교기출 4회차Document7 pages서초구 고교기출 4회차ᄋᄋNo ratings yet

- The Benefits of Positive Emotions at WorkDocument4 pagesThe Benefits of Positive Emotions at WorkAgustina NadeakNo ratings yet

- Effect of Prone Positioning on Respiratory Rate and Oxygen Saturation in Infants with RDSDocument3 pagesEffect of Prone Positioning on Respiratory Rate and Oxygen Saturation in Infants with RDSAgustina VivoNo ratings yet

- Cholera Toolkit 2013Document280 pagesCholera Toolkit 2013UNICEFNo ratings yet

- Abnormal Cervical CytologyDocument21 pagesAbnormal Cervical CytologyNatalia HaikaliNo ratings yet

- PE 10 LAS Quarter 3Document20 pagesPE 10 LAS Quarter 3Dennis100% (1)

- HerbicidesDocument28 pagesHerbicidesDr.KanamNo ratings yet

- What Is Moxibustion Acupuncturedrcmt PDFDocument3 pagesWhat Is Moxibustion Acupuncturedrcmt PDFStillingKruse2No ratings yet

- Instructions: Answer What Are Being Asked ForDocument23 pagesInstructions: Answer What Are Being Asked ForCatlyn Tagala CalzadoNo ratings yet

- Colonic Irrigation: Holistic Cleansing and DetoxificationDocument5 pagesColonic Irrigation: Holistic Cleansing and DetoxificationVijaya RaniNo ratings yet

- Cam CMD 2022 Presentation SepDocument156 pagesCam CMD 2022 Presentation SepLeBron JamesNo ratings yet

- Spa Tleung 112016Document1 pageSpa Tleung 112016Denzel Edward CariagaNo ratings yet

- Fever: Central Nervous System ConditionsDocument14 pagesFever: Central Nervous System ConditionsthelordhaniNo ratings yet

- DM-PH&SD-GU17-HCKS2 - Health Requirements For Kids SalonsDocument13 pagesDM-PH&SD-GU17-HCKS2 - Health Requirements For Kids SalonsPraveenKatkooriNo ratings yet

- CDC Emails On Changing DefinitionsDocument67 pagesCDC Emails On Changing DefinitionsEpoch TranslatorNo ratings yet

- Flow rate uniformity of TARAL 200 PITON TURBO sprayer for pest controlDocument4 pagesFlow rate uniformity of TARAL 200 PITON TURBO sprayer for pest controlAndreea DiaconuNo ratings yet

- Postpartum Health AssessmentDocument11 pagesPostpartum Health Assessmentapi-546355462No ratings yet

- Chapter 6 - Adipose TissueDocument13 pagesChapter 6 - Adipose TissueREMAN ALINGASANo ratings yet

- 849 FullDocument13 pages849 FullAnsuf WicaksonoNo ratings yet

- JMP 2023 Wash HouseholdsDocument172 pagesJMP 2023 Wash Householdsmadiha.arch24No ratings yet

- Emotional ResilienceDocument3 pagesEmotional ResilienceGODEANU FLORIN100% (1)

- Principles of Paragraph Writing IIIDocument15 pagesPrinciples of Paragraph Writing IIITitiek DwiNo ratings yet

- Patient Care in Radiography 8th Edition Ehrlich Test BankDocument5 pagesPatient Care in Radiography 8th Edition Ehrlich Test Bankselinadu4in1100% (22)

- H&PEDocument2 pagesH&PEDanielleNo ratings yet