Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Plantar Fasciitis: What Is The Diagnosis and Treatment?

Uploaded by

Gener Toriq BachreisyOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Plantar Fasciitis: What Is The Diagnosis and Treatment?

Uploaded by

Gener Toriq BachreisyCopyright:

Available Formats

2.

5

ANCC

Contact

Hours

Plantar Fasciitis

What Is the Diagnosis and Treatment?

Rachel E. Johnson ▼ Kim Haas ▼ Kyle Lindow ▼ Robert Shields

Foot pain, specifically plantar heel pain, is a common com- specifically the medial calcaneal tubercle (Lawrence,

plaint among patients in a podiatric or orthopaedic office Rolen, Morshed, & Moukaddam, 2013), and extends

setting but may be seen in primary care offices, urgent distally into the five metatarsophalangeal joints and

care centers, or emergency departments as well. There ends and the proximal phalanges of the digits (Healey &

are numerous causes for heel pain, but plantar fasciitis is Chen, 2010; Neufeld & Cerrato, 2008). The fascia has

the most frequent cause. The diagnosis of plantar fasciitis

three distinct bands that run along the plantar foot that

includes the medial, central, and lateral bands. The fib-

is generally made clinically, but there are many diagnostic

ers of the plantar fascia blend into the dermis, flexor

modalities that may be used to confirm the diagnosis. Treat- tendon sheaths, and the deep transverse metatarsal liga-

ment of plantar fasciitis ranges from conservative measures ments among other ligaments (Healey & Chen, 2010). In

to surgical interventions, but most cases of plantar fascii- 1954, Hicks described the plantar fascia to be similar to

tis can be managed conservatively. There is no definitive a Windlass effect or mechanism to the arch (Cutts et al.,

treatment proven to be the best option for plantar fasciitis. 2012; Healey & Chen, 2010; Neufeld & Cerrato, 2008).

Treatment is patient dependent and commonly requires a During toe off of gait analysis, the toes are dorsiflexed

combination of different modalities to successfully alleviate resulting in a tightening of the plantar fascia along its

the symptoms. In this article, plantar fasciitis from defining entire course. This tightening shortens the plantar fas-

the disorder, diagnosis, and treatment are discussed. cia and increases tension along the fascial band, thus

activating the windlass mechanism. This increases the

stability and rigidity of the arch and prepares the foot

A

patient who all offices and emergency depart- for the propulsive phase of gait (Cutts et al., 2012;

ments may see at some point is one who pre- Healey & Chen, 2010).

sents as this case example. A 45-year-old Now that we know what the plantar fascia is and

woman comes in to the office with complaints where it is located, the next question is why it becomes

of foot pain that upon questioning is more localized to painful and debilitating. The term plantar fasciitis

the right plantar medial surface of the heel. She states implies an inflammatory process to the plantar fascia,

that the pain started approximately 3–4 weeks ago with- but literature review may not totally support that impli-

out any trauma to the area. She states that the pain is cation. Plantar fasciitis is a result from repetitive micro

worse in the morning, after periods of rest, and at the trauma to the fascia (Cutts et al., 2012; Healey & Chen,

end of the day. This patient case begins the typical com- 2010; Neufeld & Cerrato, 2008). This repetitive micro

plaint scenario for the diagnosis of plantar fasciitis. An trauma leads to degeneration and micro tears of the

orthopaedic nurse, whether working in an office, emer-

gency department, or even the orthopaedics floor, will

likely see a patient who will present with this chief com- Rachel E. Johnson, RN, DPM, is an Assistant Professor of the Podiatric

Medicine Department at Kent State University College of Podiatric

plaint or follow them possibly in the postoperative area Medicine, 6000 Rockside Woods Blvd. Independence, OH 44131. She

or on the orthopaedic floor. Approximately 10%–16% of can be reached at Kent State University College of Podiatric Medicine

the population suffers from plantar fasciitis (Healey & 216.231.3300 or by email at rjohn112@kent.edu.

Chen, 2010). Diagnosis and treatment of plantar heel Kimberly Haas, DPM PGY-1, is currently a first year Podiatric resident at

pain account for more than 1 million visits to physicians the University Hospital Richmond Medical Center/Kent State University

per year in the United States (Cutts, Obi, Pasapula, & College of Podiatric Medicine.

Chan, 2012). Finally, in 80% of patients, symptoms of Kyle Lindow, MSIII, is a third year podiatric medical student at Kent

plantar heel pain are attributed to plantar fasciitis State University College of Podiatric Medicine.

(Neufeld & Cerrato, 2008). Robert Shields, MSIII, is a third year podiatric medical student at Kent

The plantar fascia, or aponeurosis, is a band of con- State University College of Podiatric Medicine.

nective tissue that supports the arch of the foot (Cutts There were no grant funds with this project.

et al., 2012; Orchard, 2012). The plantar fascia runs pre- The authors have disclosed that they have no financial interests to any

dominantly longitudinally and originates from the ante- commercial company related to this educational activity.

rior calcaneal tubercle (Healey & Chen, 2010), more DOI: 10.1097/NOR.0000000000000063

198 Orthopaedic Nursing • July/August 2014 • Volume 33 • Number 4 © 2014 by National Association of Orthopaedic Nurses

Copyright © 2014 by National Association of Orthopaedic Nurses. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

ONJ692_LR 198 7/18/14 3:17 AM

plantar fascia, as well as periostitis of the medial calcaneal describe the nature of the pain. Patients often describe

tubercle (Cutts et al., 2012; Healey & Chen, 2010; Neufeld their heel as throbbing, searing, or piercing in nature

& Cerrato, 2008). An inflammatory process may result (Cole et al., 2005) that is nonradiating and without par-

from the micro trauma to the area. Cutts et al., 2012 dis- asthesias (Toomey, 2009). As a clinician, you begin to

cuss that few cases of plantar fasciitis lead to surgical rule out nerve entrapment disorders when the patient

intervention and therefore an absence of inflammation denies any parasthesias or radiation of pain. Some

in the histology results of these specimens may not be an patients will feel as if they are “walking on a stone” or

accurate indication of whether there is a lack of presence have a “bruising heel pain” (LaPorta & LaFata, 2005).

of an inflammatory process with plantar fasciitis. Plantar Plantar fasciitis frequently has a gradual, insidious

fasciitis is more likely a multifactorial etiology in combi- onset with acute onsets being far less common (Dyck &

nation with degeneration and inflammation. Boyajian-O’Neill, 2004; LaPorta & LaFata, 2005).

Therefore, it is important to note the onset of the pain as

it could help to narrow the list of differential diagnoses

Risk Factors and Differential significantly. Patients should be asked of any history of

Diagnoses trauma to the area, especially if the onset is acute, as

this could point to a calcaneal stress fracture or plantar

The question may arise: Who is at risk for plantar fas-

fascia rupture. Patients should be asked if the pain is

ciitis? There are several risk factors associated with

worse at certain points during the day or if it persistent

plantar fasciitis. Common risk factors include obesity,

and unrelenting. Typical patients with plantar fasciitis

decreased ankle dorsiflexion or shortened/tight Achilles

often have increased pain with their first several steps in

tendon, runners, pes cavus (high arched foot type), and

the morning or after periods of prolonged inactivity

pes planus (flat foot) (Cutts et al., 2012; Healey & Chen,

(Buchbinder, 2004; Cole et al., 2005; Dyck & Boyajian-

2010; Neufeld & Cerrato, 2008). People who stand a

O’Neill, 2004; LaPorta & LaFata, 2005; McPoil et al.,

large amount of time or work on hard flooring are at

2008; Toomey, 2009; ). This condition is referred to as

higher risk (Healey & Chen, 2010). Recent increase in

poststatic dyskinesia. In most cases, the patient will

body weight or recent activity changes may trigger plan-

have an improvement in symptoms with walking or

tar fasciitis symptoms. Patients ranging in age from 40

stretching, but will ultimately worsen toward the end of

to 60 years are more frequently diagnosed (Healey &

the day (Buchbinder, 2004; McPoil et al., 2008; Toomey,

Chen, 2010), but plantar fasciitis is not limited to this

2009). Patients should be asked of any scenarios that

range. There may be a higher frequency in women

worsen the pain as patients with plantar fasciitis often

(Orchard, 2012), but the literature is conflicting as to

admit to having their symptoms exacerbated by walking

whether there is a gender predilection.

barefoot (Cole et al., 2005). Patients should be asked of

A differential diagnosis list must be considered when

any recent modifications in shoe gear, activity changes,

a patient presents with foot pain that is localized to the

or weight gain as these can often elicit symptoms asso-

heel. These other diagnoses must be ruled out with a

ciated with plantar fasciitis (Buchbinder, 2004).

good history, physical examination, and other diagnos-

It is of important to note whether the patient has

tic tools if necessary. Differential diagnoses include, but

experienced pain in one heel or both. Plantar fasciitis is

are not limited to, rupture of the plantar fascia, Baxter’s

dominantly present unilaterally with bilateral involve-

neuritis, Tarsal tunnel syndrome, Medial calcaneal

ment occurring only 30% of the time (Toomey, 2009).

nerve entrapment, Fat pad atrophy, Calcaneal stress

However, in cases where bilateral presentation is evi-

fracture, bone contusion, infection, neoplasm, plantar

dent, then systemic arthropathies such as ankylosing

fibromatosis, seronegative arthropathies, and rheuma-

spondylitis, reactive arthritis/Reiter’s disease, and psori-

toid arthritis. Many of these differentials may be

atic arthritis must be considered (Buchbinder, 2004;

excluded with an extensive history and physical exami-

Cole et al., 2005; Neufeld & Cerrato, 2008). The past

nation. Below, we will cover the diagnosis and treat-

medical history should be reviewed with the patient,

ment of plantar fasciitis and indicate in some cases

especially any history of rheumatological disorder to

where these differentials may be excluded.

aid in ruling out any concerns for infection, seronega-

tive arthropathies, and rheumatoid arthritis.

History and Clinical Signs/

Symptoms Clinical Examination

The diagnosis of plantar fasciitis is made based on clini- After acquiring a history of the present illness and a past

cal history, examination, and with the aid of diagnostic medical history of the patient, we begin our physical

studies when necessary. A thorough history of present examination by means of a systematic approach. The

illness and past medical history are crucial in determin- physical examination begins by observing the patient’s

ing the most probable cause of the heel pain. Upon ini- gait. Patients may exhibit an antalgic gait as they

tial examination, patients are asked to point to the area attempt to favor the unaffected foot (Toomey, 2009;

of maximal tenderness. Patients who present with plan- Buchbinder, 2004). The patient may not be able to bear

tar fasciitis usually complain of pain localized to the weight on the affected foot, which would lead to suspi-

plantar medial aspect of the heel along the insertion of cion of a calcaneal stress fracture, bone contusion, or

the plantar fascia (Buchbinder, 2004; Cole, Seto, & plantar fascial rupture. If any of these differential diag-

Gazewood, 2005; Dyck & Boyajian-O’Neill, 2004; McPoil noses are suspected, then additional diagnostic tests

et al., 2008; Toomey, 2009). The patient is then asked to will be indicated. In addition, the patient may be obese.

© 2014 by National Association of Orthopaedic Nurses Orthopaedic Nursing • July/August 2014 • Volume 33 • Number 4 199

Copyright © 2014 by National Association of Orthopaedic Nurses. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

ONJ692_LR 199 7/18/14 3:17 AM

Those with an elevated body mass index place excessive a condition where the tibial nerve becomes entrapped

stress on the plantar fascia, especially in those who by the flexor retinaculum of the tarsal tunnel. Percussion,

spend most of the day on their feet (Cole et al., 2005; along the medial ankle, produces a radiating pain either

LaPorta & LaFata, 2005; McPoil et al., 2008). Finally, distally or both proximally and distally, known as Tinel’s

observe the shoe gear the patient presents in. or Valleix’s sign, respectively. It is among general con-

Inappropriate shoe gear that does not provide adequate sensus that plantar fasciitis does not yield radiating

heel and arch support has been determined to be a risk pain or signs of paresthesia and therefore produces a

factor for plantar fasciitis (LaPorta & LaFata, 2005). negative Tinel’s and Valleix’s (Toomey, 2009; Neufeld &

During the physical examination, palpation of the Cerrato, 2008; McPoil et al., 2008; Buchbinder, 2004).

foot and more specifically areas that correlate with Several tiers of the pedal examination have been dis-

plantar fasciitis are performed. The most common clin- cussed to determine pertinent positives that guide a

ical correlation indicative of plantar fasciitis is a local- diagnosis of plantar fasciitis. Pertinent negatives are of

ized area of maximal tenderness at the medial calcaneal equal importance as they allow a physician to build con-

tubercle (Buchbinder, 2004; Cole et al., 2005; LaPorta & fidence in a particular diagnosis, or refute it and begin

LaFata, 2005; McPoil et al., 2008; Neufeld & Cerrato, searching for other causative conditions. As mentioned

2008; Toomey, 2009). Direct palpation of this area elicits previously, heel pain is a common complaint among

the pain experienced by patients after long periods of patients and, therefore, other possibilities must be ruled

weight bearing or periods of rest. To thoroughly investi- out to further confirm a diagnosis of planter fasciitis.

gate the integrity of the plantar fascia, the function must

also be assessed which is accomplished by performing

the Windlass Test. The Windlass test applies a dorsiflex- Diagnostics

ory force to the hallux resulting in plantarflexion of the Diagnostic modalities may be used when proper history

first metatarsal, effectively increasing the arch of the and physical evaluation results are inconclusive. Select

foot, making the medial band of the plantar fascia taut. imaging studies are beneficial when ruling out other dif-

Palpation is then performed along the plantar fascial ferential diagnoses of heel pain as well as contributing

bands, which may further confirm the diagnosis of plan- supportive evidence toward the diagnosis of plantar fas-

tar fasciitis if any of the bands are painful to palpation, ciitis. Radiography, bone scan, magnetic resonance

especially the medial band. Palpation is performed imaging (MRI), and ultrasonography comprise the most

along the insertion of the Achilles tendon to rule out common studies ordered by physicians when assessing

insertional Achilles tendonitis. The foot and more spe- heel pain.

cifically the heel itself are evaluated for any bruising or Radiographs are a valuable tool in ruling out acute

edema that could indicate traumatic incident, which osseous abnormalities that cause heel pain such as cal-

would lead to consideration of a bone contusion or caneal stress fractures (Lawrence et al., 2013). A lateral

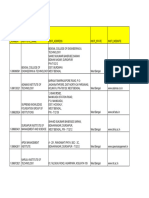

plantar fascial rupture. Also, the plantar fat pad or lack radiograph of the foot (see Figure 1) to assess soft tissue

thereof should be evaluated. changes should be the first choice if imaging is desired

Next, range of motion of the joints of the foot are (McPoil et al., 2008). Radiographs can identify a pro-

performed, particularly range of motion of the ankle nated foot type (i.e., pes planus), which has been shown

joint. An additional finding that has been correlated to correlate with chronic heel pain (Irving, Cook, Young,

with plantar fasciitis is the presence of equinus (a short, & Menz, 2007). Routine radiographs have been shown

or tight Achilles tendon) (Buchbinder, 2004; Dyck & to provide no real benefit in diagnosis or treatment in

Boyajian-O’Neill, 2004; LaPorta & LaFata, 2005; McPoil patients with plantar heel pain (Levy, Mizel, Clifford, &

et al., 2008; Neufeld & Cerrato, 2008; ). More objectively, Temple, 2006) unless an unusual presentation such as a

David D. Dyck noted that ankle dorsiflexion of 10 or less positive heel squeeze test or history of trauma is noted

degrees, beyond forming a right angle between the (Toomey, 2009). As is common with stress fractures,

lower leg and foot, as the most important independent radiographs are limited in their ability to identify frac-

risk factor in the development of plantar fasciitis. tures in the early stages as fracture lines may not be evi-

Compensation for equinus is achieved by everting the dent for several weeks. An MRI or bone scan would

subtalar joint during weight bearing that increases ten- likely be indicated at this point. Radiographic evidence

sile load on the plantar fascia, possibly exacerbating or of heel spurring along the plantar aspect of the calca-

creating the patient’s presenting symptoms (Dyck & neal tuberosity is a prospective finding in patients with

Boyajian-O’Neill, 2004). Observation of the patient plantar fasciitis (see Figure 1). Although there is a

weight bearing may reveal a pronated or cavus foot slightly increased incidence of heel spurs in patients

type.

Calcaneal stress fracture is a differential diagnosis of

concern with heel pain and must be evaluated during

physical examination, a negative heel squeeze test

should be observed. A compressive force is applied on

the calcaneus from lateral to medial, which will elicit

pain in the presence of a calcaneal stress fracture. The

absence of such pain tentatively rules out stress fracture

pending future radiographic studies (Toomey, 2009).

Another condition that must be considered because of

anatomical proximity is tarsal tunnel syndrome. This is FIGURE 1. Lateral radiograph with small calcaneal spur.

200 Orthopaedic Nursing • July/August 2014 • Volume 33 • Number 4 © 2014 by National Association of Orthopaedic Nurses

Copyright © 2014 by National Association of Orthopaedic Nurses. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

ONJ692_LR 200 7/18/14 3:17 AM

Magnetic resonance imaging is considered vastly

superior to other imaging modalities in terms of its soft-

tissue contrast resolution when evaluating plantar fas-

ciitis (Lawrence et al., 2013). Magnetic resonance imag-

ing is ideal when surgical correction is warranted as

magnetic resonance findings can be helpful in presurgi-

cal planning (Lawrence et al., 2013). Typical magnetic

resonance findings present in plantar fasciitis include

marrow edema in the calcaneal tuberosity, intrafascial

and perifascial edema on T2-weighted images, and fusi-

form plantar fascial thickening (Lawrence et al, 2013).

Normal ranges of plantar fascial thickness vary among

the literature, but it is regarded as a general consensus

that 2–4 mm would constitute a normal range

(Buchbinder, 2004). Patients with plantar fascia thick-

ness exceeding 4 mm are considered to be abnormal

FIGURE 2. Ultrasound of plantar fascia performed in office. and were symptomatic (Healey & Chen, 2010). In addi-

tion, magnetic resonance imaging can be used to iden-

tify plantar fascia ruptures, which appear as a partial or

with symptomatic plantar fasciitis, it is becoming a gen- complete disruption of the fascia with associated edema

eral consensus that the pain associated with plantar fas- and hemorrhage on T2 or STIR images (Lawrence et al.,

ciitis has a weak, if any, correlation to the presence of 2013). Ruptures occur as a result of strenuous pedal

heel spurring (Healey & Chen, 2010; Toomey, 2009). activity or as result of repeated corticosteroid injections

This belief brings criticism to the widely accepted syn- when treating chronic plantar fasciitis (Lawrence et al,

onymy between plantar fasciitis and “heel spur syn- 2013). Magnetic resonance imaging is useful in ruling

drome,” which now appears to be quite misleading. out other causes of heel pain such as Achilles tendino-

Other radiographic findings that can be seen with heel sis, Achilles tendon tears, Achilles paratendinitis, retro-

pain are bone tumors, bone cysts, periostitis, and ero- calcaneal bursitis, Haglund’s deformity, calcaneal apo-

sions due to infection of rheumatologic causes (Healey phytisits, calcaneal stress fractures, and Os trigonum

& Chen, 2010). syndrome (Lawrence et al., 2013).

Triphasic bone scans use technetium-99 and are a Ultrasound is thought to be as effective as MRI or

sensitive but nonspecific imaging technique. In assess- bone scan in diagnosing plantar fasciitis (Toomey,

ing heel pain, they are thought to be most beneficial 2009). The fact that it is noninvasive, readily available,

when differentiating between plantar fasciitis and and inexpensive makes it a great alternative to other

calcaneal stress fractures. In a stress fracture, there will imaging modalities. Many physician offices may have

be diffuse, intense increased activity whereas plantar an ultrasound machine on site (see Figure 2). A normal

fasciitis will show focal uptake of in the area of the plantar fascia tends to be hyperechoic and isoechoic

medial calcaneal tuberosity due to chronic periostitis with adjacent fat (Healey & Chen, 2010). Sonographic

and inflammation (Healey & Chen, 2010). Bone findings of fusiform thickening and hypoechoic

scintigraphy can rule out infections in the foot such as (darkened) fascia were deemed to be diagnostic of plan-

osteomyelitis. tar fasciitis (Karabay, Toro, & Hurel, 2007). As noted

FIGURE 3. Ultrasound measurement of plantar fascia.

© 2014 by National Association of Orthopaedic Nurses Orthopaedic Nursing • July/August 2014 • Volume 33 • Number 4 201

Copyright © 2014 by National Association of Orthopaedic Nurses. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

ONJ692_LR 201 7/18/14 3:17 AM

previously, normal plantar fascia thickness is approxi- to resolution of 12.5 weeks. A disadvantage to night

mately 2–4 mm (see Figure 3). Ultrasonography can be splints is that they may be uncomfortable to some peo-

used to assess the thickness and echogenicity of the ple and disrupt sleep.

plantar fat pad, although Karabay and colleagues deter- There is a taping method utilized for treatment of

mined that these findings were not diagnostic of plantar plantar fasciitis called a low-Dye taping. This taping

fasciitis. High-resolution ultrasound can help physi- helps immobilize the foot and decrease the distance

cians determine their course of treatment for plantar between the origin and insertion of the plantar fascia and

fasciitis based on sonographic findings. Patients with thus relieve fascia strain (Healey & Chen, 2010). It is a

perifascial edema on ultrasound benefited from corti- good indicator of the efficacy of orthotics for treatment

costeroid injections, whereas those lacking perifascial of a patient’s plantar fasciitis symptoms. The low-Dye

edema had a better outcome with extracorporeal shock- taping may provide temporary relief of mild to moderate

wave therapy (Sorrentino et al., 2008). Ultrasound may heel pain but is an ineffective monotherapy for chronic

additionally be used in the treatment of plantar fasciitis plantar fasciitis (Goff & Crawford, 2011). If a low-Dye

when used for ultrasound-guided steroid injections. taping relieved a patient’s plantar fasciitis symptoms,

orthotics are indicated for the long-term treatment.

There are prefabricated orthotics that may be utilized or

Treatment a patient can be casted for custom-molded orthotics.

Now that plantar fasciitis has been diagnosed, how do Many studies have shown effectiveness to be similar

we treat it? Plantar fasciitis is usually considered to be a between prefabricated and custom-molded orthotics.

self-limiting condition, but there are many treatment Prefabricated orthotics will be much less expensive than

modalities ranging from conservative measures to sur- the custom-molded orthotics. For custom-molded

gical management. Conservative therapies are the main- orthotics, a patient is first cast in office using either plas-

stay of treatment, beginning with patient-directed ther- ter or foam box most commonly, but there are other

apies then progressing to physician-prescribed materials that may be used. During the casting, the

modalities, and improve the condition in 90% of patients patient’s subtalar joint is held in a neutral position and

(Goff & Crawford, 2011). Surgical interventions are the midtarsal joint is maximally pronated. This will allow

reserved for chronic or recalcitrant cases of plantar the custom orthotic to hold the patient’s foot in a neutral

fasciitis and are required only in about 1% of patients position during gait to decrease tension on the plantar

suffering from plantar fasciitis (Cutts et al., 2012). fascia.

One of the first-line treatments of plantar fasciitis is There are modifications that can be made to a cus-

rest and oral analgesics such as acetaminophen and tom orthotic to help achieve better relief of plantar fas-

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Oral steroids ciitis symptoms. A high medial flange may be added to

such as a Medrol dose pack may be used to treat plantar increase motion control at the medial plantar area of

fasciitis symptoms, but nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory the arch of the orthotic (Cox & Cox, 2013). A plantar

drugs and analgesics are used on a more frequent basis. fascia groove may be added as a concavity on the medial

A small, randomized placebo-controlled study of non- aspect to accommodate the inflamed medial band of

steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to treat plantar fas- plantar fascia (Cox & Cox, 2013). A groove may be added

ciitis showed short-term improvement in pain relief and to the heel portion of the orthotic to offload any undue

disability when accompanied by other conservative stress caused by plantar calcaneal spurring (Cox & Cox,

treatments (Goff & Crawford, 2011). Analgesics have 2013). A medial heel skive may be added to essentially

not been proven to improve plantar fasciitis symptoms lift the medial aspect of the heel cup to bring the heel to

when used as the only treatment. a more neutral position (Cox & Cox, 2013). These are

Stretching is another early treatment for plantar fas- the most common orthotic modifications used when

ciitis. Stretching of the gastroc-soleal complex (Achilles treating plantar fasciitis.

tendon) and/or plantar fascia is indicated. There are As stated before, corticosteroids may be given orally

many stretching techniques used in various combina- to treat the symptoms of plantar fasciitis. A local injec-

tions. In one study, at 8 weeks there was improvement in tion of corticosteroids may be used, too, after other con-

52% of patients stretching only the plantar fascia and servative measures have failed. The plantar fascial injec-

22% of patient stretching only the gastroc-soleal com- tion usually consists of a local anesthetic and

plex (Healey & Chen, 2010). There is no definitive corticosteroid mix that is injected into the heel at the

amount of time that should be dedicated to stretching point of maximum tenderness usually either medially or

each day, but increased amount of time spent stretching at times plantarly. Generally, most physicians perform

generally correlates with greater improvement of symp- only a limited number of corticosteroid injections per

toms. year, depending on the patient’s response to the injec-

Night splints are another form of treatment that tions. Limited evidence supports the use of corticoster-

essentially is used for prolonged stretching. They are oid injections to manage plantar fasciitis. There is a

worn at night and keep the ankle in a neutral or slightly Cochrane study that proved corticosteroids did help

dorsiflexed position. This prevents nocturnal contrac- manage plantar fasciitis symptoms at 1 month but not

ture of the plantar fascia and promotes stretching of the at 6 months when compared to control groups (Cole

Achilles tendon. Healey and Chen 2010 relay studies on et al., 2005). Injections should be used with caution

the effectiveness of night splints and all patients in the because they are associated with plantar fascia rupture

study experience substantial relief, with an average time and plantar fat pad atrophy.

202 Orthopaedic Nursing • July/August 2014 • Volume 33 • Number 4 © 2014 by National Association of Orthopaedic Nurses

Copyright © 2014 by National Association of Orthopaedic Nurses. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

ONJ692_LR 202 7/18/14 3:17 AM

In recent years, other injectables have been utilized open procedure. One of the most common complica-

to try to manage plantar fasciitis. Hyperosmolar dex- tions that may arise from an endoscopic procedure is

trose (prolotherapy), whole blood, platelet-rich plasma, sural neuritis at the lateral port. Care must be taken to

and onabotulinumtoxin A (Botox) are being investi- avoid this important neural structure. There is a higher

gated as treatment options (Goff & Crawford, 2011). A satisfaction rate in patients receiving an endoscopic

few small studies have proven these other injectable procedure versus an open procedure (Healey & Chen,

options as effective, but there is no concrete evidence to 2010).

prove that they are more effective than a corticosteroid Finally, cryosurgery and radiofrequency nerve abla-

injection. Platelet-rich plasma is the most promising of tion are much less commonly used procedures to allevi-

these alternatives and a randomized controlled trial is ate plantar fasciitis symptoms. Cryosurgery utilizes

under way to determine whether platelet-rich plasma is subfreezing temperatures to produce analgesic effects.

effective in treating plantar fasciitis. A 3-minute freeze 30-second thaw cycle is used during

Additional conservative methods and adjuncts may this procedure. Studies are still being performed to

include immobilization, ice, formal physical therapy, assess the effect on nerve and soft tissue structures after

and shoe gear modification. A physician may consider the freeze–thaw cycles (Healey & Chen, 2010).

placing the patient in an immobilizing device, such as a Radiofrequency ablation utilizes heat around the tip of

CAM walking boot, to rest the area for a short time an electrode to ablate the nerves that are thought to be

period. Ice may be used to the plantar heel for 10–15 the source of plantar fasciitis pain. Very few studies

minutes, depending on your patient’s neurological and have been performed to assess the effectiveness of this

vascular status. Some physicians recommend massage therapy for treatment of plantar fasciitis (Healey &

to the heel. Examples of devices that a patient could use Chen, 2010).

at home to massage the area include a frozen water bot- There are multiple treatment modalities available for

tle, which incorporates the icing, and a golf ball. A phys- the treatment of plantar fasciitis ranging from conserv-

ical therapy consult may be considered for additional ative to surgical in nature. In a high percentage of

stretching techniques and instruction as well as other patients, conservative therapy is sufficient to alleviate

modalities that the physical therapist may use during the symptoms of plantar fasciitis. Surgical therapy is

sessions. Shoe modification may also be considered reserved for chronic cases of plantar fasciitis. No one

depending on the patient’s shoe gear to a more stable treatment has been proven more effective than another

and supportive shoe. and usually a combination of different therapies is uti-

Extracorporeal shockwave therapy is another newer lized for successful treatment of plantar fasciitis.

therapy being used in the treatment of plantar fasciitis.

Extracorporeal shockwave therapy is used to promote

neovascularization to aid in healing the degenerative Conclusion

tissue found in plantar fasciitis (Goff & Crawford, 2011). Plantar fasciitis is a common diagnosis in a patient who

This treatment option is noninvasive and offers hope for enters the office, urgent care, or emergency department

a faster recovery time. The adverse effects of extracor- with heel pain. Within the nursing profession, a nurse

poreal shockwave therapy are pain during and after the or nurse practitioner will invariably come in contact

treatment, ecchymosis to therapy site, and numbness with a patient who relates foot pain, specifically heel

with dysesthesia (Goff & Crawford, 2011). At this time, pain, and should be aware of the diagnosis of plantar

there are conflicting studies to the effectiveness of extra- fasciitis and what aspects of the history and examina-

corporeal shockwave therapy as a treatment of plantar tion they will participate in. Plantar fasciitis has a mul-

fasciitis. tifactorial etiology. A thorough history and physical

Fasciotomies (transection of fascia) may be per- examination should be performed to confirm the diag-

formed and allow for release of the tight plantar fascial nosis and to rule out any differential diagnoses. At

bands. Generally, only the medial and central bands of times, additional diagnostic testing may be required

plantar fascia are released and the lateral band is left and useful in your evaluation of suspected plantar fas-

intact. An open plantar fasciotomy may be performed ciitis. Once the diagnosis of plantar fasciitis is made,

with an incision typically placed along the plantar there is a multitude of treatment options. Conservative

medial aspect of the heel just distal to the origin of the treatment therapies are very effective in relieving the

plantar fascia on the calcaneal tubercle. Risks of open pain and only in a small number of the patient popula-

surgery include about one in four patients still experi- tion is surgical treatment indicated. Recurrence of plan-

encing pain and an overrelease of fascia leading to flat tar fasciitis may occur, but during our literature search

foot (Healey & Chen, 2010). An advantage to an open we did not find a statistical analysis of how often and

procedure is allowing resection of a calcaneal spur if when. Recurrence is likely associated with the risk fac-

one is present. Removal of the spur is not warranted, tors mentioned initially, such as increased weight gain,

though, as a cadaveric study was performed that found changes in activity, or shoe gear as well as the other risk

about half the cases of plantar fasciitis with a bone factors listed. Prevention of recurrence lies in continued

spur present, the bony spur was not in the same layer stretching exercises, shoe modifications to a more sta-

as the plantar fascia (Cutts et al., 2012). An endoscopic ble and supportive shoe, and wearing orthotics if they

plantar fasciotomy has become more popular because were prescribed in initial treatment. A patient with a

of its minimally invasive nature and visualization of recurrence may need additional treatment modalities as

plantar fascial bands. Complications and recovery well. Plantar fasciitis is has a multifactorial etiology

times are greatly reduced compared to those of an with many treatment options with no treatment option

© 2014 by National Association of Orthopaedic Nurses Orthopaedic Nursing • July/August 2014 • Volume 33 • Number 4 203

Copyright © 2014 by National Association of Orthopaedic Nurses. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

ONJ692_LR 203 7/18/14 3:17 AM

standing above the rest. Conservative treatment is Karabay, N., Toro, T., & Hurel, C. (2007). Ultrasonographic

successful in the majority of cases. The practitioner and evaluation in plantar fasciitis. Journal of Foot and

the patient must work together to diagnose and appro- Ankle Surgery, 46(4), 442–446.

priately resolve plantar fasciitis. LaPorta, G. A., & LaFata, P. C. (2005). Pathologic condi-

tions of the plantar fascia. Clinical Podiatric Medical

Surgery, 22(1), 1–9.

Lawrence, D. A., Rolen, M. F., Morshed, K. A., &

REFERENCES Moukaddam, H. (2013). MRI of heel pain. American

Buchbinder, R. (2004). Clinical practice: Plantar fasciitis. Journal of Roentgenology, 200(4), 845–855.

New England Journal of Medicine, 350(21), 2159–2166. Levy, J. C., Mizel, M. S., Clifford, P. D., & Temple, H. T.

Cole, C., Seto, C., & Gazewood, J. (2005). Plantar fasciitis: (2006). Value of radiographs in the initial evaluation of

Evidence-based review of diagnosis and therapy. non-traumatic adult heel pain. Foot and Ankle

American Family Physician, 72(11), 2237–2242. International, 27(6), 427–430.

Cox, D., & Cox, K. (2013). Cast correction & mold design. McPoil, T. G., Martin, R. L., Cornwall, M. W., Wukich, D.

Cox Orthotic Lab. Retrieved October 20, 2013, from K., Irrgang, J. J., & Godges, J. J. (2008). Heel pain—

http://www.coxorthotics.com plantar fasciitis: clinical practice guidelines linked to

Cutts, S., Obi, N., Pasapula, C., & Chan, W. (2012). Plantar the international classification of function, disability,

fasciitis. Annals of The Royal College of Surgeons of and health from the orthopaedic section of the

England, 94(8), 539–542. American Physical Therapy Association. Journal of

Dyck, D. D., Jr. & Boyajian-O’Neill, L. A. (2004). Plantar Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 38(4), A1–A18.

fasciitis. Clinical Journal of Sports Medicine, 14(5), Neufeld, S. K., & Cerrato, R. (2008). Plantar fasciitis: evalu-

305–309. ation and treatment. Journal of the American Academy

Goff, J. D., & Crawford, R. (2011). Diagnosis and treatment of Orthopedic Surgery, 16(6), 338–346.

of plantar fasciitis. American Family Physician, 84(6), Orchard, J. (2012). Plantar fasciitis. British Medical Journal,

676–682. 10, 345. doi:10.1136/bmj.e6603

Healey, K., & Chen, K. (2010). Plantar fasciitis: Current di- Sorrentino, F., Iovane, A., Vetro, A., Vaccari, A., Mantia, R.,

agnostic modalities and treatments. Clinical Podiatric & Midiri, M. (2008). Role of high-resolution ultra-

Medical Surgery, 27(3), 369–380. sound in guiding treatment of idiopathic plantar fas-

Irving, D. B., Cook, J. L., Young, M. A., & Menz, H. B. ciitis with minimally invasive techniques. La

(2007). Obesity and pronated foot type may increase Radiologica Media, 113(4), 486–495.

the risk of plantar heel pain: A matched case–control Toomey, E. P. (2009). Plantar heel pain. Foot and Ankle

study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 8, 41. Clinics, 14(2), 229–245.

For 90 additional continuing nursing education activities on

quality improvement topics, go to nursingcenter.com/ce.

204 Orthopaedic Nursing • July/August 2014 • Volume 33 • Number 4 © 2014 by National Association of Orthopaedic Nurses

Copyright © 2014 by National Association of Orthopaedic Nurses. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

ONJ692_LR 204 7/18/14 3:17 AM

You might also like

- Physiotherapy Treatment in Plantar Fasciitis: A Case Report: January 2015Document6 pagesPhysiotherapy Treatment in Plantar Fasciitis: A Case Report: January 2015ayuNo ratings yet

- Synopsis Plantar FascitiisDocument18 pagesSynopsis Plantar FascitiisSherry bhattiNo ratings yet

- Extensor Tendon Injuries 2010 The Journal of Hand SurgeryDocument8 pagesExtensor Tendon Injuries 2010 The Journal of Hand SurgeryProfesseur Christian DumontierNo ratings yet

- Articulo DTM 1 PDFDocument9 pagesArticulo DTM 1 PDFAna maria mendozaNo ratings yet

- Plantar Fasciitis A Review of Treatments.4Document5 pagesPlantar Fasciitis A Review of Treatments.4diki Tri MardiansyahNo ratings yet

- Acute Nursing Care of The Older Adult With Fragility Hip Fracture: An International Perspective (Part 2)Document26 pagesAcute Nursing Care of The Older Adult With Fragility Hip Fracture: An International Perspective (Part 2)spring flowerNo ratings yet

- Hallux Valgus BTA, International Journal of PM and R 0.988 2019Document4 pagesHallux Valgus BTA, International Journal of PM and R 0.988 2019ypz55735No ratings yet

- BAB I FixDocument5 pagesBAB I FixUmmi AzizahNo ratings yet

- Evidence-Based Podiatry: A Clinical Guide to Diagnosis and ManagementFrom EverandEvidence-Based Podiatry: A Clinical Guide to Diagnosis and ManagementDyane E. TowerNo ratings yet

- Does Manual Therapy Improve Pain and Function in Patients With Plantar Fasciitis? A Systematic ReviewDocument12 pagesDoes Manual Therapy Improve Pain and Function in Patients With Plantar Fasciitis? A Systematic ReviewDavid InfanteNo ratings yet

- Managing The Patient With Heel PainDocument5 pagesManaging The Patient With Heel Painmh8m58brjnNo ratings yet

- Balius R. 2021. HFPS Beyond Acute Plantar Fasciitis.Document32 pagesBalius R. 2021. HFPS Beyond Acute Plantar Fasciitis.Javier MartinNo ratings yet

- Plantar and Medial Heel Pain: Diagnosis and Management: Review ArticleDocument9 pagesPlantar and Medial Heel Pain: Diagnosis and Management: Review ArticleGhani AbdurahimNo ratings yet

- Metsemakers2017 1Document16 pagesMetsemakers2017 1Cris JiménezNo ratings yet

- Heigh2019 PDFDocument9 pagesHeigh2019 PDFVALENNo ratings yet

- KneeDocument10 pagesKneeMario Rico GonzálezNo ratings yet

- Medicine: Hoffa Fracture of The Femoral CondyleDocument7 pagesMedicine: Hoffa Fracture of The Femoral Condylesheshagiri vNo ratings yet

- Acute Nursing Care of The Older Adult With Fragility Hip Fracture An International Perspective Part 2 PDFDocument15 pagesAcute Nursing Care of The Older Adult With Fragility Hip Fracture An International Perspective Part 2 PDFOktaNo ratings yet

- Oup Accepted Manuscript 2018Document9 pagesOup Accepted Manuscript 2018Carolina PereiraNo ratings yet

- Articulo Diciembre 2019Document6 pagesArticulo Diciembre 2019LUCIA BELLOSO GONZÁLEZNo ratings yet

- Heel Pain Plantar Fascitis Hard Vs Sorft Orthotics and Heels PadDocument11 pagesHeel Pain Plantar Fascitis Hard Vs Sorft Orthotics and Heels PadDik 40No ratings yet

- 239 1078 4 PBDocument5 pages239 1078 4 PBEmiel AwadNo ratings yet

- Cavus Foot Correction Using A Full Percutaneous Procedure: A Case SeriesDocument8 pagesCavus Foot Correction Using A Full Percutaneous Procedure: A Case Seriespaulobrasil.ortopedistaNo ratings yet

- Current Trends in Tendinopathy ManagementDocument19 pagesCurrent Trends in Tendinopathy ManagementEduardo Santana SuárezNo ratings yet

- Trigger Point Therapy and Plantar Heel Pain: A Case Report: The FootDocument5 pagesTrigger Point Therapy and Plantar Heel Pain: A Case Report: The FootRo KohnNo ratings yet

- Bartold S.J. (2004) The Plantar Fascia As Souce of PainDocument13 pagesBartold S.J. (2004) The Plantar Fascia As Souce of PainManuel DamilNo ratings yet

- Neural Therapy of An Athletes Chronic Plantar FasDocument6 pagesNeural Therapy of An Athletes Chronic Plantar FasMario Emilio MathieuNo ratings yet

- 485-Article Text-605-1-10-20161227 PDFDocument10 pages485-Article Text-605-1-10-20161227 PDFJeg1No ratings yet

- First Page PDFDocument1 pageFirst Page PDFaudiNo ratings yet

- Case Study Gait Assessment of A Patient With Ha 2024 International JournalDocument6 pagesCase Study Gait Assessment of A Patient With Ha 2024 International JournalRonald QuezadaNo ratings yet

- Calcaneo-Stop Procedure in The Treatment of The Juvenile Symptomatic FlatfootDocument4 pagesCalcaneo-Stop Procedure in The Treatment of The Juvenile Symptomatic FlatfootEmiel AwadNo ratings yet

- Indications and Clinical Outcomes of High Tibial Osteotomy A Literature ReviewDocument8 pagesIndications and Clinical Outcomes of High Tibial Osteotomy A Literature ReviewPaul HartingNo ratings yet

- Prevalence and Type of Long Term Disabilities Among An Insured Cohort of OrthodontistsDocument5 pagesPrevalence and Type of Long Term Disabilities Among An Insured Cohort of OrthodontistsPatricia BurbanoNo ratings yet

- MutiLoc Nail Versus Philos Plate inDocument9 pagesMutiLoc Nail Versus Philos Plate inResi de Trauma OrtopediaNo ratings yet

- The Functional Appliance Debate The Choice Is YourDocument2 pagesThe Functional Appliance Debate The Choice Is YourAriana AmarilesNo ratings yet

- Sarmiento - 2011Document422 pagesSarmiento - 2011jmhinos4833No ratings yet

- The Role of Orthodontics in Temporomandi20161013 6132 1xvcb8q With Cover Page v2 2Document20 pagesThe Role of Orthodontics in Temporomandi20161013 6132 1xvcb8q With Cover Page v2 2Sara PetekNo ratings yet

- Acute Fractures of The Pediatric Foot and AnkleDocument7 pagesAcute Fractures of The Pediatric Foot and AnkleAlejandro Godoy SaidNo ratings yet

- Belhan O. 2019. Thickness of Heel Fat Pad Patients Plantas FasciitisDocument5 pagesBelhan O. 2019. Thickness of Heel Fat Pad Patients Plantas FasciitisJavier MartinNo ratings yet

- Journal of Cranio-Maxillo-Facial Surgery: SciencedirectDocument7 pagesJournal of Cranio-Maxillo-Facial Surgery: SciencedirectananthNo ratings yet

- Early Outcome After The Use of The Triceps Fascia Flap in Interposition Elbow Arthroplasty A Novel Method in The Treatment of Post-Traumatic Elbow StiffnessDocument6 pagesEarly Outcome After The Use of The Triceps Fascia Flap in Interposition Elbow Arthroplasty A Novel Method in The Treatment of Post-Traumatic Elbow StiffnessJohannes CordeNo ratings yet

- Anthony JP Mathes SJ: SourceDocument4 pagesAnthony JP Mathes SJ: SourcekramierNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Flatfeet-A Disease Entity That Demands Greater Attention and TreatmentDocument9 pagesPediatric Flatfeet-A Disease Entity That Demands Greater Attention and TreatmentGiovanna AriasNo ratings yet

- Identifying Vascular Pathologies or Flow Limitations Important Aspects inDocument4 pagesIdentifying Vascular Pathologies or Flow Limitations Important Aspects inDiana ArevaloNo ratings yet

- Osteopathic Manipulative Treatment of Congenital TDocument7 pagesOsteopathic Manipulative Treatment of Congenital TDiana SchlittlerNo ratings yet

- JTD 2018 ORCWI 14 FinalDocument13 pagesJTD 2018 ORCWI 14 FinalLinh DoanNo ratings yet

- Low-Level Laser Therapy at 635 NM For Treatment of Chronic Plantar Fasciitis. A Placebo-Controlled, Randomized StudyDocument5 pagesLow-Level Laser Therapy at 635 NM For Treatment of Chronic Plantar Fasciitis. A Placebo-Controlled, Randomized StudymarioNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document5 pagesChapter 1CHRISTIAN CALAMBANo ratings yet

- Pin Site Care Using Chlorhexidine Case Study Report: Desak Wayan SuarsedewiDocument10 pagesPin Site Care Using Chlorhexidine Case Study Report: Desak Wayan SuarsedewiBabang YasNo ratings yet

- Infection: Long Bone Osteomyelitis in Adults: Fundamental Concepts and Current TechniquesDocument7 pagesInfection: Long Bone Osteomyelitis in Adults: Fundamental Concepts and Current TechniquesAdriana NavaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2214031X20300693 MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S2214031X20300693 MainCristhian Jover CastroNo ratings yet

- Orthopaedics PunchDocument6 pagesOrthopaedics PunchHicham GawishNo ratings yet

- 4.RCT Oliveira2015Document10 pages4.RCT Oliveira2015elproedrosNo ratings yet

- Bennett FractureDocument5 pagesBennett FractureeviherdiantiNo ratings yet

- WJGPT 2 9Document8 pagesWJGPT 2 9Ana Beatriz RibeiroNo ratings yet

- Does Manual Therapy Improve Pain and Function in Patients With Plantar Fasciitis? A Systematic ReviewDocument11 pagesDoes Manual Therapy Improve Pain and Function in Patients With Plantar Fasciitis? A Systematic ReviewMagali Perez AdassusNo ratings yet

- The Novel Periosteal Flap Stretch Technique: A Predictable Method To Achieve and Maintain Primary Closure in Augmentative ProceduresDocument10 pagesThe Novel Periosteal Flap Stretch Technique: A Predictable Method To Achieve and Maintain Primary Closure in Augmentative ProceduresAshish PandaNo ratings yet

- Hip Bone Marrow Edema Presenting As Low Back Pain A Case ReportDocument10 pagesHip Bone Marrow Edema Presenting As Low Back Pain A Case ReportVizaNo ratings yet

- Current Understanding of TendinopathyDocument40 pagesCurrent Understanding of TendinopathyMaxNo ratings yet

- Proximal Humerus Fractures Epidemiology and TrendsDocument5 pagesProximal Humerus Fractures Epidemiology and TrendsHelena Sofia Fonseca Paiva De Sousa TelesNo ratings yet

- DBMS Lab ManualDocument57 pagesDBMS Lab ManualNarendh SubramanianNo ratings yet

- WBDocument59 pagesWBsahil.singhNo ratings yet

- The Covenant Taken From The Sons of Adam Is The FitrahDocument10 pagesThe Covenant Taken From The Sons of Adam Is The FitrahTyler FranklinNo ratings yet

- TriPac EVOLUTION Operators Manual 55711 19 OP Rev. 0-06-13Document68 pagesTriPac EVOLUTION Operators Manual 55711 19 OP Rev. 0-06-13Ariel Noya100% (1)

- Buried PipelinesDocument93 pagesBuried PipelinesVasant Kumar VarmaNo ratings yet

- UltimateBeginnerHandbookPigeonRacing PDFDocument21 pagesUltimateBeginnerHandbookPigeonRacing PDFMartinPalmNo ratings yet

- What's New in CAESAR II: Piping and Equipment CodesDocument1 pageWhat's New in CAESAR II: Piping and Equipment CodeslnacerNo ratings yet

- Delonghi Esam Series Service Info ItalyDocument10 pagesDelonghi Esam Series Service Info ItalyBrko BrkoskiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document13 pagesChapter 2Kumkumo Kussia KossaNo ratings yet

- Cooperative Learning: Complied By: ANGELICA T. ORDINEZADocument16 pagesCooperative Learning: Complied By: ANGELICA T. ORDINEZAAlexis Kaye GullaNo ratings yet

- 8051 NotesDocument61 pages8051 Notessubramanyam62No ratings yet

- Building Services Planning Manual-2007Document122 pagesBuilding Services Planning Manual-2007razanmrm90% (10)

- Baseline Scheduling Basics - Part-1Document48 pagesBaseline Scheduling Basics - Part-1Perwaiz100% (1)

- The RBG Blueprint For Black Power Study Cell GuidebookDocument8 pagesThe RBG Blueprint For Black Power Study Cell GuidebookAra SparkmanNo ratings yet

- An Annotated Bibliography of Timothy LearyDocument312 pagesAn Annotated Bibliography of Timothy LearyGeetika CnNo ratings yet

- Topic 3Document21 pagesTopic 3Ivan SimonNo ratings yet

- Review On AlgebraDocument29 pagesReview On AlgebraGraziela GutierrezNo ratings yet

- Final Project Strategic ManagementDocument2 pagesFinal Project Strategic ManagementMahrukh RasheedNo ratings yet

- Dwnload Full Principles of Economics 7th Edition Frank Solutions Manual PDFDocument35 pagesDwnload Full Principles of Economics 7th Edition Frank Solutions Manual PDFmirthafoucault100% (8)

- Intellirent 2009 CatalogDocument68 pagesIntellirent 2009 Catalograza239No ratings yet

- Iguana Joe's Lawsuit - September 11, 2014Document14 pagesIguana Joe's Lawsuit - September 11, 2014cindy_georgeNo ratings yet

- Injections Quiz 2Document6 pagesInjections Quiz 2Allysa MacalinoNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Public Health ManagementDocument3 pagesFundamentals of Public Health ManagementHPMA globalNo ratings yet

- Music CG 2016Document95 pagesMusic CG 2016chesterkevinNo ratings yet

- SOL LogicDocument21 pagesSOL LogicJa RiveraNo ratings yet

- Recitation Math 001 - Term 221 (26166)Document36 pagesRecitation Math 001 - Term 221 (26166)Ma NaNo ratings yet

- Shakespeare Sonnet EssayDocument3 pagesShakespeare Sonnet Essayapi-5058594660% (1)

- Scholastica: Mock 1Document14 pagesScholastica: Mock 1Fatema KhatunNo ratings yet

- World Insurance Report 2017Document36 pagesWorld Insurance Report 2017deolah06No ratings yet

- Micro Lab Midterm Study GuideDocument15 pagesMicro Lab Midterm Study GuideYvette Salomé NievesNo ratings yet