Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Dimensions, Determinants, and Differences in The Expatriate Adjustment Process

Uploaded by

syed bismillahOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Dimensions, Determinants, and Differences in The Expatriate Adjustment Process

Uploaded by

syed bismillahCopyright:

Available Formats

Dimensions, Determinants, and Differences in the Expatriate Adjustment Process

Author(s): Margaret A. Shaffer, David A. Harrison and K. Matthew Gilley

Source: Journal of International Business Studies , 3rd Qtr., 1999, Vol. 30, No. 3 (3rd

Qtr., 1999), pp. 557-581

Published by: Published by: Palgrave Macmillan Journals on behalf of Academy of

International Business.

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.com/stable/155465

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

http://www.jstor.com/stable/155465?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Palgrave Macmillan Journals is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access

to Journal of International Business Studies

This content downloaded from

35.154.245.7 on Sat, 04 Jul 2020 10:40:38 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Dimensions, Determinants, and Differences

in the Expatriate Adjustment Process

Margaret A. Shaffer*

THE HONG KONG POLYTECHNIC UNIVERSITY

David A. Harrison**

UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON

K. Matthew Gilley***

OKLAHOMA STATE UNIVERSITY

We comprehensively test the Black, by large multinational firms. The

Mendenhall, and Oddou (1991) multi-dimensionality of adjustment

model of the dimensions and deter- was investigated and confirmed.

minants of adjustment to interna- Support for the expanded Black et

tional assignments. We also al. (1991) model was found.

expand the model to examine two Several significant moderating

individual factors (i.e., previous effects emerged, showing different

assignments and language fluency) patterns of adjustment for those

and three positional factors (i.e., with different amounts of pervious

hierarchical level, functional area, expatriate experience and levels of

and assignment vector) as modera- host country language fluency.

tors of adjustment determinants. Hierarchical level and assignment

Surveys were completed by 452 vector were also important modera-

expatriates from 29 different coun- tors, but the effects for functional

tries assigned to 45 host countries area were generally weak.

Expatriates represent a major invest- foreign assignments are at least three

ment for multinational corporations times the base salaries of their domestic

(MNCs). It has been estimated that the counterparts (Wederspahn, 1992).

first-year costs of sending expatriates on Sixteen to forty percent of assignments

*Margaret A. Shaffer is an assistant professor of management at the Hong Ko

Polytechnic University. Her research interests include expatriate adjustment and perfor-

mance and workplace aggression.

* David A. Harrison is a professor of management at the University of Texas, Arlingt

He studies work role adjustment, executive decision-making, time, and organizational

measurement.

K. Matthew Gilley is an assistant professor of strategic management at Oklahoma State

University. His current research interests include expatriate issues, outsourcing, and

corporate governance.

JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS STUDIES, 30, 3 (THIRD QUARTER 1999): 55 7-581. 557

This content downloaded from

35.154.245.7 on Sat, 04 Jul 2020 10:40:38 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

EXPATRIATE ADJUSTMENT

end in failure (Black, 1988), and costs (1991) as a foundation, we first assess

have risen from as much as $250,000 a the dimensionality of adjustment and

decade ago (Copeland & Griggs, 1985) to comprehensively test the adjustment

$1 million per failure for U. S. firms determinants proposed in their model.

today (Shannonhouse, 1996). In spite of We then extend our study to examine

these high costs, MNCs are increasingly the complexity of the adjustment

using expatriates, not only for tradition- process by considering the moderating

al control and expertise reasons, but effects of both individual adjustment

also to facilitate entry into new markets, factors (previous assignment experience

or to develop international management and host country language fluency) and

competencies (Torbiorn, 1994). positional characteristics (hierarchical

Consequently, the effective management level, functional area, and assignment

of expatriate assignments is an impor- vector).

tant challenge for international human

resource managers. LITERATURE REVIEW AND

Of the many factors affecting the suc- HYPOTHESIS DEVELOPMENT

cess of international assignments, cross- Integrating the international and

cultural adjustment has probably domestic adjustment literatures, Black

received the most attention from et al. (1991) proposed two major compo-

researchers. To guide this research, nents of the expatriate adjustment

Black, Mendenhall, and Oddou (1991) process. The first component, anticipa-

developed an integrated model of inter- tory adjustment, includes selection

national adjustment. Yet, most empiri- mechanisms and accurate expectations,

cal studies of adjustment have focused which are based on training and previ-

on a (small) subset of the hypothesized ous international experience. The prop-

antecedents; none have attempted to er level of anticipatory adjustment facil-

test the full, a priori model for all itates the second major component, in-

dimensions of adjustment simultane- country adjustment. This component

ously. Furthermore, extant studies have consists of four main factors: job (role

generally assumed that the adjustment clarity, discretion, conflict, and novel-

process is the same for all expatriates. ty), organizational (organizational cul-

Differences in the process or patterns of ture novelty, social support, and logisti-

adjustment for different types of expa- cal help), nonwork (culture novelty and

triates and assignments have not been spouse adjustment), and individual

explored. Finally, expatriate investiga- (self-efficacy, relation skills, and per-

tions have generally been limited to a ception skills) factors. These differen-

restricted number of locations and to tially influence three dimensions of

expatriates representing one nationality adjustment: work, interaction with

(e.g., Black, 1988, 1990; Nicholson & host country nationals, and general cul-

Imaizumi, 1993). ture.

The purpose of this paper is to inves- After discussing the dimensionality of

tigate the personal adjustment of a adjustment to an international assign-

multinational sample of expatriates liv- ment, we consider the direct determi-

ing and working in 45 countries around nants of the dimensions proposed by

the world. Using the expatriate adjust- Black et al. (1991). Building upon this

ment model developed by Black, et al. model, we explore the complexity of the

558 JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS STUDIES

This content downloaded from

35.154.245.7 on Sat, 04 Jul 2020 10:40:38 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MARGARET A. SHAFFER, DAVID A. HARRISON AND K. MATTHEW GILLEY

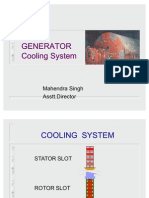

FIGURE 1

DETERMINANTS OF ADJUSTMENT TO INTERNATIONAL ASSIGNMENTS

JOB FACTORS

Role Clarity (1) POSITIONAL FACTORS

Role Discretion (1) Hierarchical Level

Role Conflict (1) Functional Area

Role Novelty (1) Assignment Vector

ORGANIZATIONAL FACTORS

Supervisor Support (1)

Coworker Support (1)

Logistical Support (2,3) EXPATRIATE ADJUSTMENT

(1) Work

(2) Interaction

NONWORK FACTORS (3) General

Culture Novelty (2,3)

Spouse Adjustment (1,2,3)

INDIVIDUAL FACTORS

Achievement Self-efficacy (1,2,3)

Social Self-efficacy (1,2,3)

aAdapted from Black, Mendenhall, and Oddou (1991); numbers in parentheses indicate the

dependent variables.

adjustment process by testing several country (socializing with host country

potential moderators. These relation- nationals - HCNs), and general adjust-

ships are depicted in Figure 1. ment to the foreign culture (living con-

ditions abroad). Exploratory factor

Dimensionality of Adjustment analyses (Black, 1988, 1990; Black &

Expatriate adjustment has been Stephens, 1989) supported a multi-

described by Black and his colleagues dimensional adjustment construct for

(e.g., Black, 1988; Black & Gregersen, American and Japanese expatriates. To

1991b; Black et al., 1991) as having confirm these dimensions of adjustment

three dimensions: adjustment to work for our multinational sample, we pro-

(job requirements), adjustment to inter- pose the following:

acting with individuals in the foreign

VOL. 30, No. 3, THIRD QUARTER, 1999 559

This content downloaded from

35.154.245.7 on Sat, 04 Jul 2020 10:40:38 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

EXPATRIATE ADJUSTMENT

Hypothesis 1 Expatriate adjustment to cal support. In a study by Guzzo,

international assignments is a multi- Noonan, and Elron (1994), expatriates'

dimensional construct consisting of judgments of sufficiency of employer

three distinct factors. benefits and their perceptions of sup-

port were significant predictors of orga-

Determinants of Expatriate nizational commitment and intention to

Adjustment quit. The other two factors, organiza-

In this section, we discuss empirical tional culture novelty and social sup-

evidence related to the four factors pro- port, have not been studied empirically.

posed by Black et al. (1991) as the direct Although it seems likely that organiza-

determinants of expatriate in-country tional culture novelty could affect expa-

adjustment. Based on this evidence, we triate adjustment, it was nearly impossi-

hypothesize various effects of these fac- ble for initial subjects in the present

tors on the different dimensions of study to distinguish it from cultural

adjustment. novelty in general. On the other hand,

Job factors. Of the four job factors social support, defined in terms of the

specified by Black et al. (1991), all have sources and quality of helping relation-

been found to be significantly related to ships (Ganster, Fusilier, & Mayes, 1986),

expatriate work adjustment. In a study does seem to be a unique and measur-

by Black and Gregersen (1991b), role able factor. The relationship between

clarity, role discretion, and role conflict social support and stress has been stud-

were significant predictors of work ied extensively, and there is evidence

adjustment. However, evidence for role that social support acts as a stress buffer

novelty is inconsistent. Although (e.g., Cohen & Wills, 1985) and that it

domestic studies of work-role transi- has an indirect effect on strains such as

tions (Munton & West, 1995) and an job dissatisfaction (e.g., Ganster et al.,

expatriate study by Black (1988) do not 1986). To test the organizational fac-

support the relationship between role tors, we propose:

novelty and adjustment, Nicholson and

Imaizumi (1993) found role novelty to Hypotheses 3a-b Higher levels of

be a significant predictor of work social support from supervisors (a)

adjustment for Japanese expatriates. To and coworkers (b) will facilitate expa-

test these four job factors, we propose: triate work adjustment.

Hypotheses 2a-b Role clarity (a) and Hypothesis 3c Higher levels of logisti-

role discretion (b) will facilitate expa- cal support will facilitate expatriate

triate work adjustment. interaction and general adjustment.

Hypotheses 2c-d Role novelty (c) and Nonwork factors. Both culture novel-

role conflict (d) will inhibit expatriate ty, which is the perceived distance

work adjustment. between the host and home cultures,

and spouse/family adjustment have

Organizational factors. Of the three been found to be significantly related to

organizational factors identified by expatriate adjustment (Black &

Black et al. (1991), the only one that has Gregersen, 1991b; Black & Stephens,

been empirically tested is that of logisti- 1989). Just as role novelty is believed to

560 JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS STUDIES

This content downloaded from

35.154.245.7 on Sat, 04 Jul 2020 10:40:38 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MARGARET A. SHAFFER, DAVID A. HARRISON AND K. MArTHEw GILLEY

inhibit work adjustment, culture novel- and perception skills. Despite its inclu-

ty is expected to inhibit the other sion in the model and in transition

dimensions of adjustment. Spouse/fam- studies (Nicholson & Imaizumi, 1993),

ily adjustment, which refers to the psy- self-efficacy, however, has not been

chological comfort experienced by the empirically tested as a predictor of

spouse and children, has long been dis- adjustment to international assign-

cussed as a potentially important influ- ments. Initially conceptualized as a

ence on expatriate adjustment (Harvey, belief in a person's ability to succeed in

1985). In a recent study by Arthur and the enactment of a specific task

Bennett (1995), family situation was (Bandura, 1977), researchers have

rated by expatriates as the most impor- recently explored the concept of general

tant contributor to successful interna- self-efficacy, defined as "an individual's

tional assignments. Despite the poten- past experiences with success and fail-

tial influence of these family-related ure in a variety of situations which

factors, as well as others such as the should result in a general set of expecta-

increasing number of dual-career cou- tions that the individual carries into

ples (Harvey, 1997), spouse employ- new situations" (Sherer et al., 1982).

ment (Black & Gregersen, 1991a), and According to these researchers, there

the likely reciprocal effect of expatriate are two dimensions of general self-effi-

adjustment on spouse adjustment cacy: one focuses on performance

(Shaffer & Harrison, 1995), the effects of achievements and another focuses on

spouse adjustment on expatriate adjust- interpersonal relationship development.

ment have generally been tested (e.g., Because adjustment to international

Black & Stephens, 1989; Nicholson & assignments involves both dimensions,

Imaizumi, 1993). These researchers we would expect high levels of achieve-

found that spouse adjustment was a sig- ment and social self-efficacy to facilitate

nificant predictor of expatriate adjust- this process.

ment. Thus, in keeping with the find- Several relational and perceptual

ings regarding both of these nonwork skills, such as willingness to communi-

factors, we propose: cate, cultural flexibility, and social ori-

entation, have been found to be signifi-

Hypothesis 4a Lower levels of per- cantly related to expatriate adjustment

ceived discrepancy between host and (Black, 1990). Not only are such skills

home cultures (i.e., less cultural nov- difficult to measure, but they also tend

elty) will facilitate expatriate interac- to vary across cultures (Harris & Moran,

tion and general adjustment. 1987). Therefore, for our multinational,

multi-location study, we include two

Hypothesis 4b Higher degrees of anticipatory adjustment variables (Black

spouse adjustment will facilitate all et al., 1991) that are indicators of these

three dimensions of expatriate adjust- skills: previous international assign-

ment. ment experience and host country lan-

guage fluency. With previous interna-

Individual factors. According to the tional experience, relocation skills are

Black et al. (1991) model, expatriate developed and these may facilitate

adjustment is affected by three individ- adjustment to a new assignment by

ual factors: self-efficacy, relation skills, reducing uncertainty associated with the

VOL. 30, No. 3, THIRD QUARTER, 1999 561

This content downloaded from

35.154.245.7 on Sat, 04 Jul 2020 10:40:38 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

EXPATRIATE ADJUSTMENT

move (Black et al., 1991). Fluency in the adjustment antecedents by changing the

host country language may also facilitate aspects of the assignment to which

adjustment by equipping individuals expatriates direct their attention (Louis,

with communications and perceptual 1980). Experienced expatriates are like-

skills (Nicholson & Imaizumi, 1993). To ly to have gone through trial-and-error

test the effects of these individual factors processes of discarding ineffective cop-

on adjustment, we propose: ing strategies and retaining effective

ones. That is, previous experience may

Hypotheses 5a-b Higher levels of change how expatriates adjust, by

achievement (a) and social (b) self- allowing them to ignore what had not

efficacy will facilitate all three dimen- worked for them in the past and to con-

sions of expatriate adjustment. centrate on what did (Russ & McNeilly,

1995). For example, first-time expatri-

Hypotheses 5c-d Previous interna- ates may need more support from super-

tional assignments (c) and fluency in visors or coworkers. On the other hand,

the host country language (d) will those who have had previous overseas

facilitate all three dimensions of experience may be better able to with-

expatriate adjustment. stand high levels of culture novelty.

Similarly, language fluency might

Moderating Relationships moderate the effect of the various

An implicit assumption of the Black antecedents on adjustment (Bell &

et al. (1991) model is that it applies Harrison, 1996). If expatriates are not

equally well to all expatriates. As with fluent in the host country language, cer-

many theories of behavioral processes, tain inputs to their adjustment could be

however, we think it is likely that some weaker. For instance, a lack of fluency

of the factors that expatriates carry with might cause expatriates to rely more on

them to their assignments will moderate support from spouses or supervisors

some of the proposed relationships (who likely speak the same language).

(Howell, Dorfman, & Kerr, 1986). In Because of the high degree of interac-

addition to the direct effects of previous tion with host country nationals often

international assignment experience required in the work environment, we

and host country language fluency would expect language fluency to

described above, we also consider pos- enhance the impact of role clarity and

sible interactive effects of these vari- discretion and diminish the impact of

ables, as well as three positional charac- role conflict and novelty. To examine

teristics (hierarchical level, functional the moderating effects of these individ-

area, and assignment vector). Although ual factors, we propose the following:

these variables are often important

selection criteria (Black et al., 1992; Hypothesis 6a Previous international

Harvey, 1996), their role in the adjust- assignments has a moderating effect

ment process has not been systematical- on the relationship between the

ly examined. antecedents (job, organizational, non-

Individual factors as moderators. work and individual factors) and the

Relocation skills acquired during previ- dimensions of adjustment.

ous overseas assignments might miti-

gate or enhance the impact of various Hypothesis 6b Fluency in the host

562 JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS STUDIES

This content downloaded from

35.154.245.7 on Sat, 04 Jul 2020 10:40:38 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MARGARET A. SHAFFER, DAVID A. HARRISON AND K. MATTHEW GILLEY

country language has a moderating select various types of expatriates

effect on the relationship between the (Harvey, 1996). For example, parent

antecedents (job, organizational, non- country nationals facilitate communica-

work and individual factors) and the tion between corporate and foreign

dimensions of adjustment. offices and third country nationals tend

to be more sensitive to cultural and

Positional factors as moderators. political issues. Such differences sug-

Differences in the nature of work and gest that the patterns of adjustment may

stress at varying hierarchical levels (e.g., vary across the three types of expatri-

Martin, 1980; Mintzberg, 1980) and ates. To test the moderating effects of

functional positions (Menon & the positional factors, we propose:

Akhilesh, 1994) should manifest them-

selves in differences in the nature of Hypothesis 7a The influence of job,

adjustment to international assign- organizational, nonwork, and individ-

ments. For example, because top man- ual factors on expatriate adjustment

agers engage in more conceptual and will vary depending on the assignee's

strategic decision making activities, role hierarchical level within the firm.

clarity may not be as important as it is

for middle and lower-level managers. Hypothesis 7b The influence of job,

For lower-level managers, who tend to organizational, nonwork, and individ-

have less home-office support, the rela- ual factors on expatriate adjustment

tionship between logistical support and will vary depending on the assignee's

adjustment may be stronger than it is for functional position.

top managers. Functional position also

influences managerial selective percep- Hypothesis 7c The influence of job,

tions (Waller, Huber, & Glick, 1995), organizational, nonwork, and individ-

and the stress resulting from working in ual factors on expatriate adjustment

different functional positions affects will vary depending on the assign-

one's adjustment to interacting with ment vector (parent country national,

others (Menon & Akhilesh, 1994). third country national, and inpatri-

Although expatriates are collectively ate).

defined as individuals living and work-

ing in a foreign environment, they are METHOD

usually classified into three broad cate-

gories or vectors based on their national Sample

origin relative to that of the parent com- To test the hypotheses presented

pany (Briscoe, 1995). Parent country above, we surveyed international

nationals (PCNs) are expatriates who are assignees employed with ten large U.S.

from the home country of the MNC; multinational corporations in a variety

third country nationals are non-PCN of industrial sectors, including trans-

immigrants in the host country (e.g., portation, aerospace, petrochemical,

those transferred between foreign sub- pharmaceutical, and other manufactur-

sidiaries); inpatriates are employees ing and service industries. Of the 1,090

from foreign subsidiaries who are surveys mailed, 483 were returned, and

assigned to work in the parent country. a usable sample of 452 questionnaires

There are several reasons why MNCs was analyzed, yielding a response rate

VOL. 30, No. 3, THIRD QUARTER, 1999 563

This content downloaded from

35.154.245.7 on Sat, 04 Jul 2020 10:40:38 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

EXPATRIATE ADJUSTMENT

CIO CIO

0-0 0-0 -0-0 -0-0 -0-0 -0-0 -0-0 -0-0 -0-0 -0-0 -00- -00- -00-

C14 N N m LO 0) r-i m N LO LO cn LO

F* cq r-4 N C14 cq 00 r-i 00 r-4 co

>

14

cti co co

co cn

cci co a)

C) cd

co

0 u

CO

w l--4

CO

tx

4 u cn

P* Po

co

u

CO -4 co

co 4 co

co C-0

C'o 8 a) 4 -o

---4

CO ..O co

CO co

co a) C)

Z Z Z cn C/5 cn cn

cn C) cn

cn

z co cn

co (3)

co C)

CO co 78 cn

4-i

a) --4 -4 C) (1) <

co cl, cn N COco

>-) U d), 4.j (3) -C'O

+b co 1-4 4.j

co cd

co co

P. z z z cn cn

X

-t:$ co C) 4-

co u co co

CO co co

CO o

(1)m CO U) 4-

5-'e,

(1)co 5

a)9 -6--i

co

z z z u uc) Mc) 04

co

z P-4

cn

co

ci

-4co

co 'm

cou CO CO C) co

-4 P-4

co cn -tz C) -4

.1-4 CO co Cd In

u -4

CO IC

co'mCom0 ",

co-4 co4.j

C) a) -13 m : 'I)

0 G.) CO

co (2) 9 C)

-4 C) 0 4 CO

F. o

u

.,..4

44 r co

z 1-4

Z co P4 C) 4 co

This content downloaded from

35.154.245.7 on Sat, 04 Jul 2020 10:40:38 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MARGARET A. SHAFFER, DAVID A. HARRISON AND K. MATTHEW GILLEY

of 41.5%. Questionnaires were com- Job Factors

pleted by expatriates assigned to 45

Role clarity was measured using a 6-

countries. They were of 29 different

item, 7-point (1=very false to 7=very

nationalities (67% American, 9%

true) scale developed by Rizzo, House,

British, 7% Australian, and all others

and Lirtzman (1970). Since this was

less than 3%), all of whom spoke and

originally a measure of role ambiguity,

read English. Characteristics of the

it was reverse-scored to indicate role

sample are presented in Table 1; demo-

clarity (Odewahn & Petty, 1980). A typ-

graphic data are comparable to those of

ical statement on the role clarity scale

the population. The individual compa-

is: "I know exactly what is expected of

nies coordinated the distribution and

me." Role discretion was measured

collection of the surveys with their

using a modified subscale (with a 7-

internal mail services and forwarded

point response format) from Hackman

them (sealed) to the researchers. In this

and Oldham's (1975) Job Diagnostic

manner, respondent confidentiality was

Survey. The reverse-scored question

assured.

was replaced with one not reverse-

scored to improve the measurement

Measures

properties of the scale (Idaszak &

Operationalizations of the constructs

Drasgow, 1987). An example of a ques-

are described below. Most measures

tion on this scale is: "How much auton-

have been used in previous research,

omy is there in your job?" Role conflict

and each had sound psychometric prop-

was measured using an 8-item, 7-point

erties in the present sample (see Results

(1=very false to 7=very true) scale devel-

section).

oped by Rizzo, House, and Lirtzman

(1970). An example of a statement on

Expatriate Adjustment

the role conflict scale is: "I receive

Expatriate adjustment was measured incompatible requests from two or more

with the scale developed by Black and

people." Role novelty was measured

his colleagues (Black, 1988; Black &

with a 4-item, 4-point (1=almost identi-

Stephens, 1989). This scale assesses

cal to 4=almost completely different)

three dimensions of adjustment and

scale developed by Nicholson and West

consists of 7 items for general adjust-

(1988). An example of a statement on

ment, 4 for interaction adjustment, and

this scale is: "The methods used to do

3 for work adjustment. General adjust-

the job are almost identical/have minor

ment items examined such things as the

differences/have major differences/are

expatriates' adjustment to living condi-

almost completely different from my

tions, housing, and food. Interaction

previous job."

adjustment items investigated the expa-

triates' adjustment to socializing with Organizational Factors

HCNs. Work adjustment items exam-

Supervisor and coworker support

ined the expatriates' adjustment to the

were operationalized with two sub-

requirements of the new position. For

scales from a survey by Caplan, Cobb,

each item, respondents indicate their

French, Harrison, and Pinneau (1975).

degree of adjustment on a 7-point scale

Each subscale consists of 4 items with

(1=very unadjusted to 7=very adjusted).

responses on a 5-point Likert-type scale.

A typical statement on the support

VOL. 30, No. 3, THIRD QUARTER, 1999 565

This content downloaded from

35.154.245.7 on Sat, 04 Jul 2020 10:40:38 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

EXPATRIATE ADJUSTMENT

scales is: "How much have you been ferent). Spouse adjustment was mea-

able to rely on (your supervisor or sured by having respondents indicate

coworkers) when things get tough?" the extent to which they thought their

Logistical support was not measured spouse "belonged," "felt comfortable,"

with a forced-choice rating scale such as and "felt at home" in the host country.

Guzzo et al. (1994) because the corpora- Responses were on a 5-point scale

tions included in the sample did not (1=strongly agree to 5=strongly dis-

want to make some features of support agree). To avoid losing data from single

salient, or create explicit expectations respondents, the mean for this variable

that some aspects of logistical support was used for those individuals who

should be improved. Therefore, we were not married. According to Cohen

operationalized the construct by exam- and Cohen (1983), this procedure will

ining comments written by the respon- not affect estimates of relationships

dents in response to open-ended ques- among other variables.

tions (e.g., "If there is anything we did-

n't cover that you think companies Individual Factors

should know about international assign- Self-efficacy was measured using the

ments, please use the space below..."). self-efficacy scale developed by Sherer

Comments were coded 1 if they had a and colleagues (1982). It contains two

positive tone, -1 if they had a negative subscales. The Achievement Self-effica-

tone, or 0 if the tone was neutral or no cy subscale (17 items) focuses on goal

comment was made. One example of a attainment, and the Social Self-efficacy

negative comment is: "I thought that subscale (6 items) focuses on the devel-

we were not given enough time or help opment of interpersonal relationships.

in finding accommodation when we Responses were made on a 5-point scale

first arrived". Two trained raters rated (1=strongly agree to 5=strongly dis-

organizational support responses indi- agree). A typical statement on the

vidually, first using a practice set of achievement subscale is: "When learn-

comments, and then using actual com- ing something new, I soon give up if I'm

ments from the surveys. Inter-rater reli- not initially successful." Previous inter-

ability for organizational support was national assignments was operational-

.95. Although this is a less-than-ideal ized as the frequency of assignments,

measure of logistical support, we use it including the present one. Language

so that we can test the Black et al. fluency was assessed by asking respon-

(1991) model in as complete a form as dents to report what foreign languages

possible. they spoke and their degree of fluency.

We then matched these reports with the

Non-work Factors language of the host country and city of

Culture novelty was measured using a assignment (Campbell, 1991) and coded

scale that Black and Stephens (1989) respondents' host country language

adopted from Torbiorn (1982). This skills on a scale from 0 to 3 (O=none,

measure consists of 8 items to which 1=poor, 2=average, 3= very good).

respondents compared their native

country to the host country on various Positional Factors

characteristics, using a 5-point Likert- Hierarchical level was measured by

type scale (1=very similar to 5=very dif- asking respondents to indicate their

566 JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS STUDIES

This content downloaded from

35.154.245.7 on Sat, 04 Jul 2020 10:40:38 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MARGARET A. SHAFFER, DAVID A. HARRISON AND K. MATTHEW GILLEY

level within their organizations (upper-, Dimensionality of Adjustment to

middle-, or lower-level of the firm). International Assignments

Functional area was measured by hav-

To examine the dimensionality of

ing respondents indicate whether they

expatriate adjustment (Hypothesis 1),

were in management or technical posi-

we conducted an exploratory factor

tions. Assignment vector was opera-

analysis on a random half of the data.

tionalized by creating three subsamples:

In this analysis, we used principal axis

parent country nationals (U.S. citizens

extraction and several techniques for

living in a foreign country), third coun-

determining the number of factors:

try nationals (non-U.S. citizens living in

scree plots, parallel analyses of random

a foreign country), and inpatriates (non-

data, maximum likelihood tests, and

U.S. citizens living in the United

interpretability criteria. Oblique rota-

States).

tions (promax) were used to help arrive

Because these measures were

at the simplest factor structure (Ford,

assessed by self-report ratings, common

MacCallum, & Tait, 1986). These meth-

method variance is a concern.

ods suggested either three or four fac-

However, for some variables, such as

tors of expatriate adjustment. Over- and

number of previous assignments, hierar-

under-factoring also led to the conclu-

chical level, functional position, and

sion that three or four factors likely

language fluency, it is unlikely that

existed in the data. Careful inspection

common method variance is a problem

revealed that the fourth factor was a

(Crampton & Wagner, 1994). Moreover,

minor one (a 'doublet'), arising from an

as common method variance inflates

especially strong correlation between

correlations, it increases the shared

only two items, both of which used the

variance among all independent vari-

term "facilities." Rather than treat this

ables, making it less likely that one

as a substantive factor, we regarded it as

would find unique, significant beta-

a wording artifact in the confirmatory

weights. Also, because common

factor analysis described below,

method variance is a main effect, it only

accounting for it as correlated error

inflates zero-order correlations and does

between the two items.

not inflate the possibility of falsely

In the second random split of the

detecting moderator variables.

data, we conducted a confirmatory fac-

tor analysis (CFA) using LISREL VIII

RESULTS

and maximum likelihood estimation

Means, standard deviations, zero-

(J6reskog & S6rbom, 1993). Each item's

order correlations, and reliability coeffi-

loading on its respective factor was esti-

cients for all variables are presented in

mated iteratively, using starting values

Appendix A. Except for logistical sup-

from the earlier exploratory analysis.

port, reliabilities were estimated using

All cross-loadings were fixed to zero

coefficient alpha. For logistical sup-

and were therefore potential sources of

port, inter-rater reliability was estimat-

lack of fit. Factor variances were set at

ed from the correlation between two

1.0 in lieu of choosing one item per fac-

raters' judgments about (the lack of)

tor as a "marker" variable with a load-

logistical support indicated in open-

ing of 1.0. Consistent with Black et al.'s

ended comments.

(1991) formulation, factors were

allowed to correlate. Results of the CFA

VOL. 30, No. 3, THIRD QUARTER, 1999 567

This content downloaded from

35.154.245.7 on Sat, 04 Jul 2020 10:40:38 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

EXPATRIATE ADJUSTMENT

(see Appendix B) supported Hypothesis gle items and assigned error variance of

1. The three dimensional model, with 0.

each adjustment item loading on only Parameter estimation and sequential

one factor, yielded a close fit to the data tests. Another set of SEM considera-

(Bagozzi & Yi, 1988). Fit indices were: tions involves choosing estimation pro-

X273 = 124.81 (p<.Ol), GFI = .93, AGFI = and planning a series of models

cedures

.90, NFI = .94, CFI = .97, and SRMR = to be tested. We chose maximum likeli-

.05. hood estimation because it provides the

best parameter estimates in moderate

Analytic Approach for Testing sample sizes, and it yields fit indices

Hypotheses 2-5 that allow for comparisons of nested

To evaluate the Black et al. (1991) models (J6reskog & S6rbom, 1989). In

model in its entirety, we used tests pro- our modeling approach, we first fit the

vided by structural equation modeling Black et al. (1991) framework, described

techniques (SEM: e.g., Bollen, 1989). as Model 1 below and in Table 2.

We compared various indices of good- Depending on its fit, we were prepared

ness-of-fit (Mulaik et al., 1989) to arrive to progressively relax sets of restrictions

at a bestfitting structural model, and by estimating new paths until accept-

then examined the paths in the model able fit was attained and further

that reflected each hypothesis. Prior to changes did not improve it.

reporting numerical results, however, it

is important to describe the critical Results for Tests of

choices we made before model fitting Hypotheses 2-5

(Medsker, Williams, & Holahan, 1994). Overall model. Table 2 reports the

Accounting for measurement error. results of our SEM analyses. Sequential

In addition to simultaneously account- models are listed, along with their fit

ing for all relationships in a model, the statistics and the incremental improve-

other main advantage of SEM is unbi- ment in X2 from the previous, more

ased estimation of relationships in the restricted, model. In terms of overall fit,

presence of measurement error. To the Black et al. (1991) model had a X216 =

account for this, we used a technique 117.48 (p < .01), GFI =.97 and an AGFI

first suggested by Kenny (1979), in = .75, with CFI=.91 and NFI=.91. These

which a single total score is used as a fit indices are near or slightly below rec-

measure of each construct, with error ommended levels for close fit (Bagozzi

variance set at (1-estimated reliability) & Yi, 1988). Therefore, we proceeded

x total variance of that score. with relaxing some of the restrictions in

Netemeyer, Johnston, and Burton (1990) the model.

showed that this technique conformed A noteworthy feature of our modeling

better to distributional assumptions and sequence stems from the fact that the

produced virtually identical estimates original Black et al. (1991) model

of latent regression parameters as the restricts culture novelty and logistical

multi-indicator approach. We therefore support to affect only interaction and

applied this procedure to each total general adjustment. Likewise, it con-

score for all variables except language strains job-related factors (role clarity,

fluency and number of previous assign- role discretion, role conflict, and role

ments, which were measured with sin- novelty) to affect only work adjustment.

568 JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS STUDIES

This content downloaded from

35.154.245.7 on Sat, 04 Jul 2020 10:40:38 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MARGARET A. SHAFFER, DAViD A. HARRISON AND K. MATTHEW GILLEY

Thus, the next step in our SEM plan was best-fitting model, it was possible to

to allow culture novelty and logistical examine structural coefficients (paths)

support to affect work adjustment that reflected specific hypotheses. The

(Model 2 in Table 2). However, this did parameter estimates are presented in

Table 3, along with significance levels.

not result in significantly better fit: AX22

= 2.63 (n.s.). In the ensuing step, we Standardized coefficients are given to

allowed job-related factors to "spill over" aid in comparing effect sizes.

and affect interaction and general adjust- The values in Table 3 show that role

ment (in addition to their original effect clarity, role discretion, and role novelty

on work adjustment; see Model 3 in - but not role conflict - all had a

Table 2). The fit of this less restricted unique impact on some form of adjust-

Model 3 was a substantial improvement ment, and in the anticipated directions.

over the fit of the original Black et al. These results support Hypotheses 2a,

(1991) model: AX212 = 60.62 (p < .01). 2b, and 2c, but not 2d. The strongest

Allowing both of these additions to effects of job factors were on work

occur jointly (Model 4 in Table 2) did not adjustment, as originally predicted by

improve fit over Model 3: AX22 = 2.89 Black et al. (1991), although the only

(n.s.), but it fit much better than Model 2: significant (and negative) impact of role

AX212 = 60.88 (p < .01). The GFI, CFI, novelty was on general adjustment.

NFI, and SRMR associated with Model 3 Role clarity appeared to be the strongest

were also idicative of close fit (Bagozzi & determinant of work adjustment, with a

Yi, 1988). Consequently, an augmented standardized effect size that was twice

Black et al. theory, with additional as large as any other predictor.

effects of job-related factors on interac- Organizational factors also exhibited

tion and general adjustment, was chosen many of their proposed effects.

as the best-fitting model. Coworker support (Hypothesis 3b) and

Specific hypotheses. Within this logistical support (Hypothesis 3c) both

TABLE 2

TESTS OF OVERALL STRUCTURAL MODELS FOR EXPATRIATE ADJUSTME

Model X2df AX2df GFI AGFI CFI NFI SRMR

1. Black, Mendenhall,

& Oddou (1991) Theory 117.48**16 .97 .75 .91 .91 .05

2. Model 1 plus Nonwork

Inputs to Work Adjustment 114.85**14 2.632 .97 .72 .91 .91 .05

3. Model 1 plus Work-related

Inputs to Interaction and

General Adjustment 56.96**4 60.62**2 .99 .49 .95 .96 .03

4. Models 2 and 3 combined 53.94**2 2.892 .99 .03 .95 .96 .02

Note: GFI is the Goodness of Fit Index; AGFI is the Adjusted Goodness of Fit

Index; CFI is the Comparative Fit Index; NFI is the Normed Fit Index;

SRMR is the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual.

pI**P<O

<3.01

VOL. 30, No. 3, THIRD QUARTER, 1999 569

This content downloaded from

35.154.245.7 on Sat, 04 Jul 2020 10:40:38 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

EXPATRIATE ADJUSTMENT

TABLE 3

STANDARDIZED PATH COEFFICIENrTS (y)

FOR BEST FITTING STRUCTURAL MODEL

Dependent Variable

Predictors Work Interaction General

Adjustment Adjustment Adjustment

Job Factors

Role Clarity .42** .08 .14*

Role Discretion .21** .11* .10

Role Conflict .03 -.05 -.06

Role Novelty -.02 -.07 -.15**

Organizational Factors

Supervisor Support -.05 -.03 -.01

Coworker Support .11 .29** .10

Logistical Support .10* .08

Nonwork Factors

Culture Novelty -.17** -.30**

Spouse Adjustment .06 .13** .34**

Individual Factors

Achievement Self-efficacy .07 .06 -.12

Social Self-efficacy -.03 .10 .01

Previous Assignments .02 .12** .02

Language Fluency .06 .23** -.02

R2

0 .34** .36* * .37**

*p <.05 ** p <.01

facilitated interaction adjustment. on general adjustment far exceeded

Indeed, coworker support had the those of any other variable. The same

strongest influence of any variable on nonwork factors also had significant

this part of an expatriate's acclimation effects on interaction adjustment,

to the international assignment. In con- although they were not as potent.

trast, supervisor support (Hypothesis Results did not support the relevance

3a) did not significantly affect adjust- of the individual factors specified in

ment. Hypotheses 5a and 5b. Neither achieve-

The observed effects of nonwork fac- ment self-efficacy nor social self-effica-

tors also supported their corresponding cy explained incremental variance in

Hypotheses (4a and 4b). Culture novel- any of the dimensions of adjustment.

ty hindered general adjustment, while On the other hand, the individual fac-

spouse adjustment helped it. The tors specified in Hypotheses 5c and 5d

impacts of both of these nonwork inputs were important. Both the amount of

570 JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS STUDIES

This content downloaded from

35.154.245.7 on Sat, 04 Jul 2020 10:40:38 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MARGARET A. SHAFFER, DAVID A. HARRISON AND K. MATTHEW GILLEY

previous experience in international 40.54, p < .01), and other individual

assignments and host country language (AX218= 29.20, p < .01) factors.

fluency seemed to aid in an expatriate's Language fluency. Consistent with

interaction adjustment. Hypothesis 6b, language fluency inter-

acted with the model's independent

Tests of Moderating Effects variables to influence adjustment (AX2

A final set of SEM tests involved the = 134.38, p < .01). Significant interac-

moderating effects of individual and tions were found for both job (AX224 =

positional factors proposed in 44.39, p < .01) and individual (AX218 =

Hypotheses 6a-b and 7a-c. The treat- 47.48, p < .01) factors.

ment of these discrete-step variables as Hierarchical level. In accord with

moderators is fairly well established Hypothesis 7a, hierarchical level also

and straightforward in SEM moderated the effects of the proposed

(Marcoulides & Schumaker, 1996). It is determinants of adjustment (Ax274 =

accomplished through the creation of 131.43, p < .01). In particular, job (AX224

subsample covariance matrices at each = 38.43, p < .05), organizational (AX216 =

level of the moderator (Cole, Maxwell, 42.94, p < .01), and individual (AX224 =

Arvey, & Salas, 1993). Moderating 56.56, p < .01) factors all had their

effects are evaluated by comparing the influences moderated by managerial

fit of models whose parameters are level.

forced to be the same across all subsam- Functional area. Although it was the

ples versus being allowed to vary freely weakest of all proposed moderators,

across those subsamples. If there is a functional area did have a significant

significant improvement in fit, the paths overall interactive effect (AX237 = 66.90,

differ across subsamples and an overall p < .01), which was predicted by

moderating effect has been detected. Hypothesis 7b. Specifically, it moderat-

The source of the overall effect can then ed the influence of the individual fac-

be pinpointed by subsequently restrict- tors on adjustment (AX212 = 22.46, p <

ing particular (sets of) paths, to see if .05). This effect stemmed from a single

keeping them the same across subsam- large difference in the influence of lan-

ples significantly degrades the fit of the guage fluency on the interaction adjust-

model (Lomax, 1983). In the tests ment of managers versus technicians.

described below, we followed the over- Assignment vector. According to

all moderator tests with analyses indi- Hypothesis 7c, employees on overseas

cating if the moderating effects occurred assignments will experience different

for the job, organization, nonwork, or patterns of adjustment depending on

individual factors. These results are whether they are parent country nation-

presented in Table 4. als, third country nationals, or inpatri-

Previous assignment experience. ates. This proposition was born out in

Previous experience on international the data, with a test showing that the

assignments was a significant overall moderating effects of assignment vector

moderator of the influences on adjust- were significant overall (Ax274 = 182.44,

ment (AX268 = 124.82, p < .01), which p < .01). This positional variable mod-

supports Hypothesis 6a. Specifically, it erated the impact of all types of inputs

moderated the impact on the job (AX224 = to adjustment: job (AX224 = 51.74, p <

39.25, p < .01), organizational (AX216 = .01), organizational, (AX216 = 56.32, p <

VOL. 30, No. 3, THIRD QUARTER, 1999 571

This content downloaded from

35.154.245.7 on Sat, 04 Jul 2020 10:40:38 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

EXPATRIATE ADJUSTMENT

co

>

to

+

co

co

co

co E--4

to

co

CIJ Lo

4-j

CIO

co

tx

O

4

;T-(

tx

co C)

0 C/)

LO

C/)

'e4

C/)

7:1

0

-4

C/)

0

> 4-i .1-4

cn

P-4 cn C/)

M-4 cid

U C)

0 $=O E

4-i cid cn

$-4

-4 C/) 0 cj

cn cn ;>

0 -4 z 'a E - -)4

cn %-, V. 0 rZ4 --4 cn

C/) C) -4

t > (1) a) cid > co

-C z 1-4 $-4 fn

oi

u

'a)

a)

P.4

0 O

C)0Z4 Pt

cn.,..4

:Z a) -.0En

-4

CO --4 --4 --f --4 t-J -4 4 a) -4 >

.,..4

-cl

O cn

a4

C)

-4

(f) >

$-4

u (n 'a)

-12)

$-4 C/)

II

(1) It:$ 'e4 0.4 1-4 4--A

$-4 ol 'a) -+

44 0-4 1-4 -

This content downloaded from

35.154.245.7 on Sat, 04 Jul 2020 10:40:38 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MARGARET A. SHAFFER, DAVID A. HARRISON AND K. MATTHEW GILLEY

.01), non-work (AX21o = 36.24, p < .01), ing all three dimensions of adjustment.

and individual factors (AX224 = 49.36, p < Below, we further explore the results

.01). The source of these variations in and make concrete suggestions for

adjustment patterns was almost always application and research in this critical

a difference of inpatriates versus parent domain.

and third country nationals. In fact, the

expanded Black et al. (1991) model had Main Effects

much greater explanatory power for Our analyses revealed that many of

inpatriates than for the other two the direct effects proposed by Black et

groups. The R2 for the latent adjustment al. (1991) were indeed significant pre-

variables ranged from .66-.75 in the dictors of adjustment. The significance

inpatriate subsample, but ranged from of three job-related factors (i.e., role

.39-.49 in the parent and third country clarity, role discretion, and role novelty)

national subsamples. highlights the importance of job design

to the success of international assign-

DISCUSSION ments. This suggests that multinational

firms should place more emphasis on

Summary designing global positions such that

This study provides considerable sup- expatriates have more clearly defined

port for, and empirical clarification of, jobs and greater decision-making

the Black et al. (1991) model of expatri- authority. Furthermore, greater levels

ate adjustment to international assign- of pre-departure training may be neces-

ments. First, factor analysis confirmed sary for expatriates expected to experi-

that adjustment to international assign- ence higher levels of role novelty.

ments has three substantive dimen- Of the organizational support factors,

sions. Second, the Black et al. (1991) logistical support and coworker support

model fit fairly well, but the fit were significant positive predictors of

improved when the work-related factors adjustment. As a result, firms seeking

were allowed to influence interaction to enhance the effectiveness of their

and general adjustment. Third, all of expatriates should attempt to foster a

the immediate antecedents proposed by supportive organizational culture both

Black et al. (1991) that we tested at home and abroad. For example, dedi-

emerged as either significant main or cated home-office support staff, ideally

interactive effects on adjustment. comprised of highly experienced expa-

However, this study goes beyond con- triates, could aid in this initiative by

firming their model by testing factors acting as mentors for international

that we proposed would moderate the assignees. On-site organizational sup-

influence of the antecedents on the port could be fostered by providing

three types of adjustment. We found cross-cultural skills training for both

that two proposed individual factors expatriates and their host country

(previous international assignment national colleagues.

experience and host country language The non-work factors, culture novelty

fluency) and three positional factors and spouse adjustment, were important

(hierarchical level, functional area, and direct effects of interaction and general

assignment vector) are noteworthy mod- adjustment, as predicted by Black et al.

erators of various relationships involv- (1991). Thus, cross-cultural training for

VOL. 30, No. 3, THIRD QUARTER, 1999 573

This content downloaded from

35.154.245.7 on Sat, 04 Jul 2020 10:40:38 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

EXPATRIATE ADJUSTMENT

expatriates and their spouses, whose ment, except for role novelty, were

own adjustment will likely be affected involved in significant interactions.

by culture novelty, is vital for the suc- The differential effects for nonwork fac-

cess of international assignments. In tors, however, occurred only in interac-

addition, because the level of adjust- tions involving assignment vector. This

ment experienced by expatriates' spous- suggests that culture novelty and spouse

es directly influences the adjustment adjustment have a more universal

processes of the expatriates themselves, impact on adjustment, regardless of the

firms must place more emphasis on expatriate's experience, language fluen-

preparing spouses for international cy, or position in the organization.

assignments and supporting those Below, we discuss some of the stronger

spouses once in the foreign environ- interactions involving each of the five

ment. Having a person in the firm that moderators.

spouses could contact directly, rather Previous international experience.

than relying on 'second-hand' informa- Experience in previous international

tion from expatriates, would help to assignments was found to be a powerful

reduce much of the uncertainties associ- moderator, especially in relationship

ated with settling into a foreign culture. with supervisor and coworker support.

Also, with the increasing number of Supervisor support seemed to work in

dual career couples, it is likely that differing ways, depending on whether

more spouses will want to work. By the expatriate was a first-timer or had

offering employment assistance, such as been on several international assign-

help with work visas or subsidized ments. For those on their first assign-

career development activities, MNCs ment, supervisor support negatively

can facilitate the adjustment of these influenced all three dimensions of

spouses. adjustment. The opposite effect was

Of the individual factors, previous found for more experienced expatriates,

international experience and fluency in suggesting that those who have been on

the host-country language had signifi- multiple assignments tend to rely more

cant, direct effects on expatriate interac- on on-site management rather than the

tion adjustment. However, these main home office (effects for logistical sup-

effects are only part of the influence of port were neutral) to facilitate the

such variables on adjustment; they also adjustment process. Similarly, expatri-

were associated with differing patterns ates on their first assignment relied less

of other inputs to adjustment, as dis- on coworker support for their work and

cussed below. general adjustment than did those with

more international assignment experi-

Moderating Relationships ence. These findings indicate that

Several interesting results surfaced home office support of expatriates may

with respect to the moderating power of be generally lacking, and suggests that

previous assignment experience, lan- firms should take steps to improve their

guage fluency, hierarchical level, func- global support networks.

tional area, and assignment vector. Language fluency. Although role con-

Each proposed moderator had a signifi- flict did not have a direct impact on any

cant influence on adjustment in general, dimension of adjustment, it was

and all of the antecedents of adjust- involved in important interactions with

574 JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS STUDIES

This content downloaded from

35.154.245.7 on Sat, 04 Jul 2020 10:40:38 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MARGARET A. SHAFFER, DAVID A. HARRISON AND K. MATTHEW GILLEY

host-country language fluency. For all but it did have a significant overall

three aspects of adjustment, the nega- effect on adjustment, primarily because

tive impact of role conflict was stronger of one large difference. Host-country

for those who were fluent than for those language fluency was much more

who had only moderate host-country important for the interaction adjustment

language skills. Thus, fluency in the of technical expatriates than managerial

host-country language exacerbated the expatriates. This may be indicative of

effects of role conflict on adjustment. the important role of technicians in the

Perhaps those who are fluent are more transfer of knowledge to host country

aware of the contradictory demands nationals, in which case language train-

from host country nationals and parent ing is critical for this group of expatri-

company employees; those who are not ates.

fluent may not even notice the conflict- Assignment vector. The three assign-

ing signals. ment categories were all involved in sig-

Hierarchical level. Several significant nificant interactions with at least one of

interactions involving hierarchical level each of the job, organizational, non-

emerged. For job factors, the moderat- work, and individual factors. The pat-

ing effect on work adjustment was car- terns of adjustment were quite similar

ried by the increasingly important influ- for parent country nationals and third

ence of role discretion as expatriates country nationals. The only difference

held higher-level positions. Thus, con- between these two groups was that cul-

sistent with Karasek's (1979) job ture novelty had a significant negative

demands/control theory of stress, expa- impact on the interaction adjustment of

triates are better adjusted as long as job parent country nationals but no impact

demands are matched by role discretion on third country nationals. This pro-

or control. Hierarchical level also inter- vides support for the contention that

acted with previous assignment experi- TCNs tend to be more culturally sensi-

ence to influence work adjustment. For tive and empathetic (Harvey, 1996). In

middle-level managers, the effect was contrast, there were distinct differences

positive, indicating that previous between the inpatriates and the other

assignment experience enhanced work two subsamples. For example, role clar-

adjustment for these managers. For ity and coworker support were impor-

senior-level expatriates, however, the tant determinants of all three dimen-

opposite effect emerged. This reversal sions of adjustment for inpatriates, but

in effects masks the overall important they affected only one adjustment

influence that previous assignment dimension for parent and third country

experience has on the work adjustment nationals. Thus, the adjustment

of expatriates at different hierarchical involved in moving to the country of

levels. In particular, the negative the parent firm seems to be a substan-

impact of previous assignment experi- tially different process from that

ence on the work adjustment of upper- involved in moving out to or moving

level managers has important implica- between international subsidiaries.

tions for both staffing and training deci- This suggests that MNCs need to con-

sions. sider different intervention programs to

Functional area. Functional area was facilitate the adjustment of inpatriates.

the weakest of the proposed moderators,

VOL. 30, No. 3, THIRD QUARTER, 1999 575

This content downloaded from

35.154.245.7 on Sat, 04 Jul 2020 10:40:38 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

EXPATRIATE ADJUSTMENT

Suggestions for Future Research levels and for the effects of role conflict

across assignment vectors. Also, just as

Insofar as this study is cross-sectional

differences were found between man-

and correlational, our results and con-

agerial levels and functional areas, there

clusions are somewhat tenuous. To

may be differences in adjustment pat-

enhance internal validity, and to

terns for line and staff managers. To

increase our understanding of the

address these issues, future researchers

adjustment process, future research

could collect more detailed information

should focus on collecting longitudinal

about expatriates' positions, including

data. However, conducting longitudinal

their day-to-day duties and responsibili-

research of any type is challenging. A

ties, involvement in decision-making,

longitudinal investigation of expatriate

and interactions with parent, third

adjustment would compound an

county, and host country nationals.

already-difficult process. One way of

overcoming this difficulty would be to

Conclusion

follow expatriates throughout their

All indications are that the number of

assignment, regularly surveying them

international assignees will increase over

using a diary-keeping method or short

the next decade. To help firms and inter-

e-mail questionnaires.

national assignees maximize the effec-

Another concern is that our classifica-

tiveness of these assignments, it is impor-

tions of parent country nationals, third

tant that we continue our investigation of

country nationals, and inpatriates are

factors that influence the adjustment

defined relative to the United States as

process. This study has provided several

the parent country. Thus, these cate-

insights into the complexities of this

gories are confounded with national ori-

process by (1) confirming the dimension-

gin and generalizability of the moderat-

ality of expatriate adjustment, (2) testing

ing effects of the assignment vector is

and supporting a comprehensive model

restricted to expatriates employed by

of adjustment, and (3) extending that

United States' MNCs. To better differ-

model to account for systematic differ-

entiate the effects of assignment type

ences in adjustment patterns across expa-

and country of origin, we encourage

triates with different language skills,

future researchers to include MNCs

international experiences, hierarchical

from a variety of nations.

levels, functional positions, and assign-

The results of this study also stimu-

ment vectors, all in a large and heteroge-

late consideration of several substantive

neous sample of expatriates. Further

issues and argue for a more complex

investigations will help both practition-

reformulation of the adjustment

ers and theorists to better understand the

process. For example, the positive and

challenges associated with managing

negative effects of achievement and

today's global work force.

social self-efficacy across well-defined

subsamples help to explain the lack of a REFERENCES

direct effect of these variables on adjust-

Arthur, Winfred, Jr. & Winston Bennett,

ment. The effects cancel each other out

Jr. 1995. The international assignee:

and are obscured when the subsamples

The relative importance of factors

are combined in the overall sample.

perceived to contribute to success.

This is also true for the influence of pre-

Personnel Psychology, 48: 99-114.

vious assignments across hierarchical

576 JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS STUDIES

This content downloaded from

35.154.245.7 on Sat, 04 Jul 2020 10:40:38 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MARGARET A. SHAFFER, DAVID A. HARRISON AND K. MATTHEW GILLEY

Bagozzi, Richard P. & Y. Yi. 1988. On Bollen, Kenneth A. 1989. Structural

the evaluation of structural equation equations with latent variables. New

models. Journal of the Academy of York: Wiley.

Marketing Science, 16: 74-94. Briscoe, Dennis R. 1995. International

Bandura, Albert. 1977. Social learning human resource management.

theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Prentice-Hall. Campbell, George L. 1991.

Bell, Myrtle P. & David A. Harrison. Compendium of the world's lan-

1996. Using intranational diversity for guages. New York: Routledge.

international assignments: A model of Caplan, Robert D., Sidney Cobb, John R.

bicultural life experiences and expatri- P. French, R. Van Harrison & Samuel

ate adjustment. Human Resources R. Pinneau, Jr. 1975. Job demands

Management Review, 65: 47-74. and worker health. Washington,

Black, J. Stewart. 1988. Work role tran- D. C.: H. E. W. Publication No.

sitions: A study of American expatri- NIOSH 75-160.

ate managers in Japan. Journal of Cohen, Jacob & Patricia Cohen. 1983.

International Business Studies, 19: Applied multiple regression/correla-

277-94. tion analysis for the behavioral sci-

Black, J. Stewart. 1990. The relation- ences (2nd ed.). New Jersey:

ship of personal characteristics with Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

the adjustment of Japanese expatriate Cohen, Sheldon & Thomas A. Wills.

managers. Management International 1985. Stress, social support, and the

Review, 30: 119-34. buffering hypothesis. Psychological

Black, J. Stewart & Hal B. Gregersen. Bulletin, 98: 310-57.

1991a. The other half of the picture: Cole, Donald A., Scott E. Maxwell,

Antecedents of spouse cross-cultural Richard Arvey & Eduardo Salas.

adjustment. Journal of International 1993. Multivariate group compar-

Business Studies, 22: 461-77. isons of variable systems: MANOVA

Black, J. Stewart & Hal B. Gregersen. and structural equation modeling.

1991b. Antecedents to cross-cultural Psychological Bulletin, 114: 174-84.

adjustment for expatriates in Pacific Copeland, L. & L. Griggs. 1985. Going

Rim assignments. Human Relations, international. New York: Random

44: 497-515. House.

Black, J. Stewart, Mark E. Mendenhall & Crampton, Suzanne M. & John A.

Gary Oddou. 1991. Toward a com- Wagner III. 1994. Percept-percept

prehensive model of international inflation in microorganizational

adjustment: An integration of multi- research: An investigation of preva-

ple theoretical perspectives. lence and effect. Journal of Applied

Academy of Management Review, Psychology, 79: 67-76.

16(2): 291-317. Ford, J. Kevin, Robert C. MacCallum &

Black, J. Stewart & Gregory K. Stephens. Marianne Tait. 1986. The applica-

1989. The influence of the spouse on tion of exploratory factor analysis in

American expatriate adjustment and applied psychology: A critical

intent to stay in Pacific Rim overseas review and analysis. Personnel

assignments. Journal of Management, Psychology, 39: 291-314.

15: 529-44. Ganster, Daniel C., Marcelline R.

VOL. 30, No. 3, THIRD QUARTER, 1999 577

This content downloaded from

35.154.245.7 on Sat, 04 Jul 2020 10:40:38 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

EXPATRIATE ADJUSTMENT

Fusilier & Bronston T. Mayes. 1986. LISREL 8: User's reference guide.

Role of social support in the experi- Chicago: Scientific Software

ence of stress at work. Journal of International.

Applied Psychology, 71: 102-10. Karasek, Robert A., Jr. 1979. Job

Guzzo, Richard A., Katherine A. demands, job decision latitude, and

Noonan & Efrat Elron. 1994. mental strain: Implications for job

Expatriate managers and the psycho- redesign. Administrative Science

logical contract. Journal of Applied Quarterly, 24: 285-304.

Psychology, 79: 617-26. Kenny, David A. 1979. Correlation and

Hackman, J. Richard & Greg R. Oldham. causality. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

1975. Development of the Job Lomax, Richard G. 1983. A guide to

Diagnostic Survey. Journal of multiple-sample structural equation

Applied Psychology, 60: 159-70. modeling. Behavior Research

Harris, P. R. & R. T. Moran. 1987. Methods and Instrumentation, 15:

Managing cultural differences. 580-84.

Houston: Gulf. Louis, M. R. 1980. Surprise and sense

Harvey, Michael G. 1985. The executive making: What newcomers experi-

family: An overlooked variable in ence in entering unfamiliar organiza-

international assignments. Columbia tional settings. Administrative

Journal of World Business, (Spring) Science Quarterly, 25: 226-51.

20: 84-92. Marcoulides, George & Randall E.

Harvey, Michael G. 1996. The selec- Schumaker. 1996. Advanced struc-

tion of managers for foreign assign- tural equation modeling: Issues and

ments: A planning perspective. techniques. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Columbia Journal of World Business, Martin, N.H. 1980. Differential deci-

31: 102-18. sions in the management of an indus-

Harvey, Michael G. 1997. Dual-career trial plant. Journal of Business, 29:

expatriates: Expectations, adjustment 249-60.

and satisfaction with international Medsker, Gary J., Larry J. Williams &

relocation. Journal of International Peter J. Holahan. 1994. A review of

Business Studies, 27: 627-658. current practices for evaluating

Howell, Jon P., Teter W. Dorfman & causal models in organizational

Steven Kerr. 1986. Moderator vari- behavior and human resources man-

ables in leadership research. agement research. Journal of

Academy of Management Review, 11: Management, 20: 439-64.

88-102. Menon, Nityamalyni & K. Akhilesh.

Idaszak, Jacqueline R. & Fritz Drasgow. 1994. Functionally dependent stress

1987. A revision of the Job among managers: A new perspective.

Diagnostic Survey: Elimination of a Journal of Managerial Psychology,

measurement artifact. Journal of 9(3): 13-22.

Applied Psychology, 72: 69-74. Mintzberg, Henry. 1980. The nature of

Joreskog, Karl G. & Dag S6rbom. 1989. managerial work. Englewood Cliffs:

LISREL 7: User's reference guide. Prentice-Hall.

Mooresville, IN: Scientific Software, Mulaik, Stanley A., Larry R. James, J. V.

Inc. Alstine, N. Bennett, S. Lind & C. D.

Joreskog, Karl G. & Dag Sorbom. 1993. Stilwell. 1989. Evaluation of good-

578 JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS STUDIES

This content downloaded from

35.154.245.7 on Sat, 04 Jul 2020 10:40:38 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MARGARET A. SHAFFER, DAVID A. HARRISON AND K. MATTHEW GILLEY

ness-of-fit indices for structural equa- Management, Vancouver.

tion models. Psychological Bulletin, Shannonhouse, R. 1996, Nov. 8.

105: 430-45. Overseas-assignment failures. USA

Munton, Anthony G. & Michael A. Today/International Edition, 8A.

West. 1995. Innovations and person- Sherer, Mark, James E. Maddux, Blaise

al change: Patterns of adjustment to Mercandante, Steven Prentice-Dunn,

relocation. Journal of Organizational Beth Jacobs & Ronald W. Rogers.

Behavior, 16: 363-75. 1982. The Self-efficacy Scale:

Netemeyer, R. G., M. W. Johnston & S. Construction and validation.

Guerton. 1990. Analysis of role con- Psychological Reports, 51: 663-71.

flict and role ambiguity in a structur- Torbiorn, Ingemar. 1982. Living

al equations framework. Journal of abroad: Personal adjustment and

Applied Psychology, 81: 400-10. personnel policy in the overseas set-

Nicholson, Nigel & Ayako Imaizumi. ting. New York: John Wiley.

1993. The adjustment of Japanese Torbiorn, Ingemar. 1994. Operative

expatriates to living and working in and strategic use of expatriates in

Britain. British Journal of new organizations and market struc-

Management, 4: 119-34. tures. International Studies of

Nicholson, Nigel & Michael A. West. Management & Organization, 24 (3):

1988. Managerial job change: Men 5-17.

and women in transition. Cambridge: Waller, Mary J., George P. Huber &

Cambridge University Press. William H. Glick, 1995. Functional

Odewahn, C.A. & M. M. Petty. 1980. A position as a determinant of execu-

comparison of levels of job satisfac- tives' selective perception. Academy

tion, role stress, and personal compe- of Management Journal, 38: 943-74.

tence between union members and Wederspahn, Gary M. 1992. Costing

non-union members. Academy of failures in expatriate human

Management Journal, 23: 150-55. resources management. Human

Rizzo, John R., Robert J. House & Sidney Resource Planning, 15: 27-35.

I. Lirtzman. 1970. Role conflict and

ambiguity in complex organizations.

Administrative Science Quarterly, 15:

150-63.

Russ, Frederick A. & Kevin M.

McNeilly. 1995. Links among satis-

faction, commitment, and turnover

intentions: The moderating effect of

experience, gender, and performance.

Journal of Business Research, 34: 57-

65.

Shaffer, Margaret A. & David A.

Harrison. 1995. Forgotten partners:

Developing and testing a model of

spouse adjustment to international

assignments. Paper presented at the

annual meeting of the Academy of

VOL. 30, No. 3, THIRD QUARTER, 1999 579

This content downloaded from

35.154.245.7 on Sat, 04 Jul 2020 10:40:38 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

EXPATRIATE ADJUSTMENT

000 qO

CS Cs (D (D dq n N ?~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~O m

H~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~0 144 '4 L Do LO _I

00 Ic C) C)rq

C: o C CD CD It m N 0

a O s O. ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

W~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~0 00 00 CDC nC C) m O) CD)

O oo CD~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~L o 0 o o ) cq CY CY m LO

00 0D CD cs c: (M N O CO4 dq c0o c

M ffi z '~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~O C' I' '~ C' r' 'i ' ' s O

n~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~c 00 CSd CD d qHN C CD C) dq C) 4 co

v~~ ~ ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Ic 11 m 11 O n N n sm N m m . e

LO cq C, C. C.C. , ..

i ~ ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ _ 0 C) 0 c- " C) C) Nq cq C ?

S n X H H H O~~~~~~~~. . . . . t . O. O. . O. .E

H~~~~~~~~~~~0 r z C) C) 0 C) C) z zz

cn~~~~~~~~~( 00 oo N N cq 00 C) cs q CS4 cq 00 Lo co co

cq 0 1X cq r- C) r- O q r- cq cq r- cq H N T- T e

za m dq It CSd D H O N CDN 00 N LO dq n c+ *

. q Cs 1 N 00 CD N N N dq N Ct) co 00 C) dq

t Cf tS O -1 d4 0 n (~~~~~~~D CD C< C< 1O r- 00 r- H N t q -