Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Cambridge University Press Economic History Association

Uploaded by

D KOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Cambridge University Press Economic History Association

Uploaded by

D KCopyright:

Available Formats

Economic History Association

The Transition from Sail to Steam in Immigration to the United States

Author(s): Raymond L. Cohn

Source: The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 65, No. 2 (Jun., 2005), pp. 469-495

Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Economic History Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3875069 .

Accessed: 28/06/2014 08:23

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Cambridge University Press and Economic History Association are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize,

preserve and extend access to The Journal of Economic History.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 185.31.195.106 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 08:23:44 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Transitionfrom Sail to Steam in

Immigration to the United States

L. COHN

RAYMOND

The transitionfrom sailing ship to steamship is analyzed for Europeanimmi-

grants arriving at New York City. Based on informationtaken from the U.S.

PassengerLists, new estimatesof the timing and length of the transitionare pro-

vided. Though the accepted model suggests the changeover from sail to steam

could occur in only a few years, it actually took about 15 years in the Europeto

New York immigranttrade.The slow transitionis found to be due to slow con-

struction of new steamships given uncertaintyconcerning immigrantvolume

and new steamshiptechnology.

The most important change in nineteenth century emi-

grant transportationwas thatfrom sail to steam.

GunterMoltmann'

... the transitionfrom sail to steam in the transatlantic

immigranttrade was an event of enormous significance

for the historyof immigration.

MaldwynAllen Jones2

As bythetheopening quotes emphasize,the replacementof the sailing ship

steamshiphad wide-rangingeffects on Europeanimmigra-

tion to the United States during the nineteenthcentury. The steamship

shortenedthe length of the voyage from a minimumof five or six weeks

to less than two weeks and decreased the variability of arrival time.3

Both factors reduced mortality. In turn, the shorter voyage led to a

change in the natureof immigration.Under sail, immigrationwas usu-

ally permanentand comprised of families, though they sometimes mi-

gratedin stages. Under steam, more males migratedon a temporaryba-

sis. Individualswould come to the United States to work for a period of

The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 65, No. 2 (June 2005). C The Economic History

Association. All rightsreserved.ISSN 0022-0507.

RaymondL. Cohnis Professor,Department of Economics,CampusBox 4200, IllinoisState

University,Normal,IL61790-4200.E-mail:rlcohn@ilstu.edu.

The authorwishes to thankDrew Keeling,RalphShlomowitz,SimoneWegge, Melissa

Thomasson,and two anonymousrefereesfor helpfulcomments,and AndreeaAndronescu,

MadhuSundararaman, andDavidSackettfor researchassistance.Thedatawerecollectedwith

the assistanceof a Collegeof ArtsandSciencesSmallGrantfromIllinoisStateUniversity,for

whichthe authorexpresseshis appreciation.An earlierversionof this paperwas given at the

2004AmericanEconomicAssociationmeetings.

1 Moltmann,"SteamshipTransport,"p. 311.

2 Jones,AmericanImmigration,p. 157.

pp. 613-

of voyagesundersail,see thediscussionsin Gould,"European,"

3 Onthevariability

14; and Tyler, Steam,pp. 125-28.

469

This content downloaded from 185.31.195.106 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 08:23:44 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

470 Cohn

time and then returnto their Europeanhomes. In addition,the steamship

drasticallyshortenedthe trip from Mediterraneanports. It was also eas-

ier for steamshipsto get in and out of secondaryports of call. Ships, for

example, might leave from Le Havre and stop in Southampton,or leave

from Liverpool and stop at an Irish port. The result was that people

could leave on betterquality ships from many more Europeanports. Fi-

nally, steamshipsbecame substantiallylargerthan sailing ships, allow-

ing passengers to cross the ocean in greatercomfort. All these factors

reducedthe costs of migrating,led to a rise in volume, and increasedthe

areas in Europefrom which immigrantscame.

Most previous studies of the transitionfrom sail to steam have em-

phasized freighttraffic and examinedwhy it took more than 50 years

from the 1850s into the early twentieth century-for steam to replace

sail on every ocean route. In contrast,this articleexamines the transition

in the movement of one group of passengers-immigrants-who trav-

eled on one route, Europe to New York City.4Estimates are presented

showing it took about 15 years-from when the steamerbecame fully

competitive-for the transitionfrom sail to steam to occur in the New

York immigranttrade.Yet this finding contrastswith the acceptedtran-

sition model, which suggests the changeovershould occur on a specific

route in only a few years. After examining factors that could lead to a

long transition,the article argues the majorfactoroperatingon the New

York route was that the steamerbecame competitive near the start of a

time period when immigrantvolume underwenta substantial,and unex-

pected, increase. Thus, it took a fairly long period of time for sufficient

passenger steamshipsto be built to handle the increasedvolume. Over-

all, this article contributesto our knowledge concerningthe economics

of technology diffusion.

THECHANGETO STEAMFORARRIVALSAT NEWYORKCITY

The estimates of the arrivals of passengers and steamships at New

York City provided in Table 1 are based on the original U.S. source of

immigrationdata, the PassengerLists. Beginning in 1820 ship captains

were requiredto file with U.S. port authoritiesa list of all passengerson

an arrivingship. These PassengerLists serve as the basis for the official

U.S. estimates of immigrationfor the nineteenthcenturyand have been

used by numerousresearchers.For this article, the entire set of original

Passenger Lists (which are available on microfilm) was examined for

4 The classic article concerningthe transitionfor freighttraffic is Harley, "Shift."One excep-

tion that has examined immigrationby steamship,though not explicitly the transition,is Keel-

ing, "Transportation Revolution."

This content downloaded from 185.31.195.106 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 08:23:44 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Transitionfrom Sail to Steam 471

every third year beginning in 1852 and continuing through 1876. For

each of these nine years, all arrivals of steamships from Europe were

included in the data set.5 In total, the data set contains informationon

2,864 voyages. For each steamshipin each year, informationon owner-

ship from N. R. P. Bonsor was included along with data gatheredfrom

the lists: the ship name, the date of arrival,the port of embarkation,the

total numberof passengers,the numberof U.S. citizens, and the number

of deaths.6 The latterthree figures were determinedby manual count if

necessary, though usually each PassengerList provided, at a minimum,

a numberedlist of passengers. The numberof immigrants(actually, to-

tal Europeanpassengers) was then determinedby subtractingfrom the

total those passengers who were U.S. citizens and those non-U.S. citi-

zens who died on the voyage.7

The numberof passengers and the percentageof passengers arriving

at New York by steamshipincreasedconsistentlythroughoutthe period

from 1852 to 1873.8 This result holds in spite of sizable fluctuations

in total immigration. Due to the potato famine, the total volume of

immigrationwas huge in the early 1850s but only about 1 percentof the

5 I distinguished steamships from sailing ships in two ways. First, the original entry on the

Passenger List usually indicated if the ship was a steamship. Second, Bonsor, North Atlantic

Seaway, provides a virtually complete list of steamships that sailed on the north Atlantic, and

the discussions in Bowen, Century,were helpful.

6 Bonsor, NorthAtlanticSeaway.

7 This procedureis a little differentfrom the one used by the original compilers. For many of

the later years, the Passenger Lists often note whether alien passengers had previously been in

the United States. Anotherissue is that some individualsarrivedon ships that only carriedcabin

passengers. I believe that in neither case were the passengers counted as immigrants.Yet the

lists for early years did not include informationon previous visits and, even for lateryears, not

all lists containedthis information.It is also unclearhow ships with only cabin passengerswere

treated in earlier years. For consistency, therefore, all the total "immigration"figures used in

this article include all passengerswho were not U.S. citizens. This issue is one reason I chose

not to use the official figures that could be constructedfrom the reportsof the Commissionersof

Emigrationof the State of New York. Neither of these issues is large quantitatively,so the esti-

mates in Table 1 are generally consistentwith those given in the official sources. A second rea-

son for not using the official reportsis that they are primarilysummariesand, as such, do not

contain informationon each individualvoyage. Official estimatesare availablefor 1856 through

1860 in Commissionersof Emigration,AnnualReports,table D(D),p. 343; and for 1863 onward

in the yearly reports,for example, Commissionersof Emigration,EmigrationReport.

8 A numberof estimates for a specific year or period of years exist in the literatureand are

mostly consistentwith those given in Table 1. Keeling, "Transportation Revolution,"p. 63, says

that 40 percentof immigrantsarrivedon steamersin 1863, the first year for which "comprehen-

sive figures . . . are available."Otherprevious estimates:Albion, Rise, p. 349, gives figures that

suggest 3.5 percent arrivedby steam in 1856 and 31.5 percent in 1860; Jones, AmericanImmi-

gration, p. 158, providesthe same figure for 1856; Guillet, GreatMigration,p. 239, says that 45

percent of British emigrantstraveled in steamshipsin 1863 and 81 percent in 1866; Hyde, Cu-

nard, pp. 91-92, says that 95 percentof all emigrantstraveledby steamshipin 1870; and Cole-

man, Going to America, says that 75 percentcame by steam in 1865.

This content downloaded from 185.31.195.106 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 08:23:44 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

472 Cohn

TABLE 1

ARRIVALS BY STEAMSHIPAT NEW YORK, 1852-1876

Arriving Total NY ArrivingNY

U.S. Immigrants: Immigrants:

Year of Passengers: Sail and Steamships Numberof Numberof Immigrants

Arrival Steamships Steam (percentage) Ships Voyages per Voyage

1852 3,989 303,153 2,989 18 77 38.8

(1.0)

1855 4,825 161,490 3,779 15 63 60.0

(2.3)

1858 7,070 85,848 16,628 33 123 135.2

(19.4)

1861 6,860 70,063 21,543 33 134 160.8

(30.7)

1864 7,195 174,434 78,112 54 218 358.3

(44.8)

1867 16,669 240,260a 193,381 92 444 435.5

(80.5)

1870 17,462 235,574a 203,447 102 476 427.4

(86.4)

1873 28,343 277,359a 269,171 133 720 373.8

(97.0)

1876 24,573 80,053a 80,053 120 609 131.4

(100.0)

a

Beginning in 1866, the figures for "TotalNY Immigrants"are reportedin the source for years

ending on 30 June. The numbersfor 1867 and 1870 in the Table are adjustedto calendaryears

using seasonal informationgiven in table 4 of the source. The total for 1873 is the sum of arri-

vals on steamshipsand those on sailing ships as recordedin the PassengerLists. Since the 1876

Passenger Lists do not record any immigrantsarrivingby sailing ship, the calendaryear 1876

total was assumedequal to the total arrivalsby steamship.

Sources: Columns 1, 3, 4, and 5: see the text. Column 2: U.S. Treasury,Arrivals, table 7, p. 82,

and table 4, p. 58. Column 6: calculatedfrom columns 3 and 5.

immigrants arrived by steamship. Total immigration fell abruptly in

1855 primarily due to the outbreak of nativism and fell further due

to the economic downturnin 1857 and the outbreakof the Civil War.9

An increase in the number of steamship voyages and passengers per

ship, however, led to almost 20 percent of the immigrantsarrivingby

steam in 1858 and 31 percentin 1861. Beginning in 1863 the volume of

immigrationagain began to increase and generally continued to do so

until the depression that began in 1873. In spite of large increases in

volume, both the total and the percentagearrivingby steamshipcontin-

ued to increase monotonically, with 97 percent of the total arrivingby

steam in 1873. The total volume fell substantiallyafter 1873 and by

1876 the transitionto steam had been completed. Thus, the figures in

Table 1 generally confirm the accepted view. Before the Civil War,

most immigrantsarrivedby sail, whereas after the Civil War, most ar-

9 See Thomas,Migration;and Cohn, "Nativism."

This content downloaded from 185.31.195.106 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 08:23:44 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Transitionfrom Sail to Steam 473

rived by steam. Yet these figures also emphasizethat the transitionwas

in effect before the Civil War, even though the final triumph of the

steamshipoccurredmainly duringthe eight years following its end.

Because each steamshipcompany serviced only one route, one might

suppose the transitionshould be analyzed by port of embarkation.This

article, however, views the change from sail to steam on the passenger

trade to New York as one transition,regardlessof the Europeanport of

embarkation.This approachis taken for both theoretical and practical

reasons. The majorports of embarkationfor ships arrivingat New York

with passengers were Liverpool, Le Havre, Bremen, Hamburg, and

Glasgow. Some ships left from other ports, but the percentage of pas-

sengers from ports other than these five was usually well under 10 per-

cent of the total arrivalsby steamship.Though Bremen, Hamburg,and

Glasgow were serviced by only one steamshipcompany in most years,

Liverpool and Le Havre saw substantialcompetition. Even the former

ports had to attractpassengers,however, and potentialpassengerscould

often choose to leave from Le Havre ratherthan Bremen or Hamburg,

or from Liverpool instead of Glasgow, or board a sailing ship rather

than a steamer. Small steamers also took passengers between Great

Britain and the Continent,and many steamshipsleaving from the Con-

tinent boarded passengers in ports in southernEngland. Thus, all the

companies would have faced similar fluctuationsin demand over time,

and thus the timing of the transitionwould have been similar across

ports of embarkation.The practical reason for grouping together all

ports of embarkationis that official sources do not provide data on the

total numberof passengers arrivingfrom each port. Thus, the transition

has to be analyzed in its entirety, though as noted, good reasons exist

for approachingthe analysis in this manner.

The figures in Table 1 indicatethatthe increasednumbersarrivingby

steamshipwere primarilydue to an increase in the numberand size of

steamships, not in the frequency of use for each ship. Fewer than 20

steamshipscarriedimmigrantsin 1852 and each voyage arrivedwith an

average of about 40 immigrants(and 52 U.S. citizens). In 1861 there

were 33 steamships, and each voyage arrivedwith an average of 161

immigrants(and 51 U.S. citizens). By 1870 the 102 steamshipsarriving

at New York carriedan average of 427 immigrantseach (and only 37

U.S. citizens). Yet the average number of voyages per ship did not

change very much. The 18 ships arrivingin 1852 averaged4.3 voyages

each during the year, whereas the 102 ships arrivingin 1870 averaged

only 4.7 voyages each. In 1852, for example, the most trips-nine-

were made by the Africa, and the Arctic made eight. In 1870 the City of

Brooklyn arrived 11 times, whereas a numberof other ships completed

This content downloaded from 185.31.195.106 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 08:23:44 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

474 Cohn

nine or ten voyages during the year. In sum, between 1852 and 1870,

the total number of immigrantsarrivingby steam increased 68 times.

This increase was due to an 11-times increase in average immigrants

per ship, a 5.7-times increase in the number of ships, and only a 9-

percent increase in the numberof trips per ship. Though the numberof

ships increased fairly consistently over the entire period of the transi-

tion, the increasein passengerload occurredmainly before 1864.

When immigrationbegan to fall during 1873 as a result of the out-

break of a depression, the shipping companies reacted in a manner

analogous to their response to the increase, mainly absorbing the de-

crease througha decline in the numberof immigrantsper ship. The de-

pression began duringthe last half of 1873 and immediatelyreducedthe

number of interestedimmigrants.The steamship companies could not,

however, quickly lower the numberof their already-scheduledvoyages.

In fact, the average numberof voyages per ship was actually higher in

1873 than in 1870. Furthermore,a large increase in steamshipbuilding

and the entry of a numberof new steamshipcompanies occurredduring

the early 1870s, as will be detailed later. All these factors caused the

average number of immigrantsper ship to be lower in 1873 than in

1870. By 1876 the mannerin which the steamshipcompaniesreactedto

the depression was clear. The total number of immigrantsfell by 70

percent between 1873 and 1876. Yet the number of ships was cut by

only 10 percentand the numberof voyages per ship by only 6 percent.

The numberof passengersper voyage, however, fell from 374 to 131, a

decline of 65 percent.In an industrywith a large fixed cost-building or

buying the ships-the reactionof the shippingcompaniesto the decrease

in demandis understandable.Betterto keep the ships in operation,which

incurreda fairly low variablecost thatcould presumablybe covered even

with the lowereddemand,thanto take ships out of commission.10

The increasein the numberof ships servingNew York was partlydue

to an increase in the number of steamship companies (Table 2). The

biggest percentage jumps in the number of immigrants carried by

steamships occurredbetween 1855 and 1858 (over four times more in

1858) and between 1861 and 1867 (3.6 times more in 1864 and another

2.5 times increase by 1867). Both are periods of substantialentry into

the industry. During the former period, the Hamburg-Americanand

North GermanLloyd lines were established,the first major companies

to operate primarilyfrom the Europeancontinent, and the Inman Line

10 Harley, "Aspects,"p. 172, estimates that one-thirdof the total costs were fixed capital costs

associated with the ship. Though his estimate is for freighters,it provides a general idea how

much the steamshiplines could cut fares in the shortrun and continueto operate.

This content downloaded from 185.31.195.106 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 08:23:44 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Transitionfrom Sail to Steam 475

TABLE2

STEAMSHIPCOMPANIESSERVINGNEW YORKa

Number of New Companies

Year of Arrival Total Numberof Companies from ThreeYears Earlier

1852 5

1855 4 1

1858 8 4

1861 5 0

1864 8 4

1867 12 3

1870 9 0

1873 16 8

1876 14 2

a

Only companies with a minimum of five voyages arrivingat New York in the given year are

included.

Source: See the text.

switched its operationsfrom Philadelphiato New York."'Between 1861

and 1867, the Anchor Line, the CGT Line, and the Guion Line entered

the marketplacealong with a numberof smaller,less-famous firms. The

time period between 1870 and 1873 had the biggest absolute increasein

immigrantvolume and also saw a large numberof new firms enter the

market,though about half of these did not continue to service the New

York route in 1876. The 1873 to 1876 time period adds a slight adden-

dum to the preceding argumentconcerningthe reactionto the large fall

in immigration.The reaction involved some decline in the number of

firms serving New York but not in proportionto the fall in volume. As

previously indicated,most ships (and companies) kept sailing, although

with many fewer passengers.

Besides informationon the arrivalsof steamships,data were also ac-

quired on the arrivalsof the remainingsailing ships in 1873 (Table 3).

Though sailing ships with passengers were still leaving from a number

of major Europeanports, large-scale immigrationby sail was taking

place predominantlyfrom Bremen,which accountedfor over 80 percent

of all individuals arrivingby sailing ship. As shown in Table 3, only

ships leaving from Bremen carried large numbers of passengers in

1873.12 Twenty-six of the 55 voyages carriedover 100 passengers, and

21 of these left from Bremen.13 Furthermore,some sailing ships were

still engaged in a regularNew York passenger trade. Six of the ships

made three voyages during 1873 and another seven ships each made

" For information

concerning various steamship companies, see Adams, Ocean Steamers;

Fry,

12History; Maginnis,AtlanticFerry; and Bonsor,NorthAtlanticSeaway.

The results here differ from those given by Guillet, Great Migration,p. 239, who implies

thatpoor Irishwere the final users of the sailing ship.

13Two left from

Hamburgand three from Liverpool.

This content downloaded from 185.31.195.106 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 08:23:44 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

476 Cohn

TABLE

3

ARRIVALSBY SAILING SHIPAT NEW YORK CITY IN 1873

Port of ArrivingU.S. ArrivingNY Number Numberof Immigrants

Embarkation Passengers Immigrants of Ships Voyages per Voyage

London 19 242 6 9 26.9

Liverpool 62 736 6 9 81.8

Le Havre 1 5 1 1 5.0

Hamburg 0 589 1 3 18.4

Bremen 41 6,610 21 32 206.6

Mediterranean 0 6 1 1 6

Total 123 8,188 36 55 148.9

Source: See the text.

two voyages. With the onset of depression in late 1873, however, the

use of sailing ships for immigranttravel quickly ended. The fall in de-

mand meant the existing steamshipshad a large amount of excess ca-

pacity. With the steamship companies anxious to keep their capital-

intensive ships in operation,the few remaining sailing vessels did not

standa chance.'4

In summary,the transitionfrom sail to steam occurredover a fairly

long period of time. In 1867, for example, almost 47,000 immigrants

still arrivedat New York City on sailing ships, as many as in 1861 and

not many fewer than the 69,000 figure in 1858 (calculated from Ta-

ble 1). The transitionthat had startedas soon as the early or mid-1850s

was not finished by 1867; in fact, it did not completely finish until 1874

or so. During the transition,specifically in the middle of the Civil War,

total immigrantvolume began to rise. Because it proved difficult to in-

crease the average numberof voyages or, after 1864, the average pas-

senger load, the increased demand had to be met by increasing the

numberof steamshipsoperatingbetween Europeand the United States.

The informationin Tables 1 and 2 makes it clear the existing companies

expanded their fleets and new companies enteredthe market.Even so,

as late as the early 1870s, over 10 percent of the immigrantsarrivingat

New York City came on sailing ships.

14The

exact date of the last sailing ship voyage with emigrantsis not clear, though it probably

was not laterthan 1874. Moltmann,"SteamshipTransport,"p. 311, says thatthe last sailing ship

from Hamburgwas in 1873. According to the Passenger Lists, the Prinz Albert arrived from

Hamburgon 1 October 1873, with 35 passengersin its thirdvoyage of the year, though the last

sailing ship to arrive in 1873 (on 26 December) was the Marco Polo from Bremen. Pettersen,

"FromSail to Steam,"p. 126, says that the last sailing ship from Norway left in 1874. Gould,

"Ocean Passenger Travel,"p. 126, also says that 1874 saw the last clipper ships with immi-

grants.On the otherhand, Taylor,Distant Magnet,p. 131, is clearly incorrectwhen he says that

"(t)heyears 1865 to 1870 saw the end of sail in the northAtlantic emigranttrade."

This content downloaded from 185.31.195.106 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 08:23:44 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Transitionfrom Sail to Steam 477

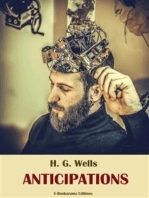

Voyage

Costs

Steamships

Sailing Ships

Length

of the

LI Voyage

FIGURE1

A VIEW OF THE TRANSITIONFROM SAIL TO STEAM

THETRANSITION

MODEL

The transitionfrom sail to steam during the nineteenth century has

usually been analyzed from the perspective of relative costs. Steam re-

placed sail on a particularroute when steam became less costly. The

general frameworkused is shown in Figure 1, which relatesthe variable

costs of the voyage to the length of the voyage for both steamshipsand

sailing ships."1Voyage costs increased more rapidly with distance for

steamshipsthan for sailing ships. The basic argumentis that steamships

requiredthe use of coal and all the coal for a particularvoyage had to be

carriedby the ship. As Britainwas the main source of coal in the world

at the time, ships leaving Europe could not reduce the amount of coal

they needed to carryby refueling along their route.16Thus, the length of

the voyage on which steamships could be competitive depended on

15 For simplicity, the cost lines in Figure 1 are shown as linear. A more technical

approachis

given in Harley, "Shift."

16Harley, "Ocean Freight Rates," p. 861, indicates that, during the nineteenth century, coal

comprised 20 percent and wages 10 percent of the cost of operating a steamer, while wages

comprised27 percentof the cost of operatinga sailing ship. Othercosts had fairly similarshares

between the two modes. At times, coal was hauled from Britainand deposited at various sites so

other steamships could refuel on their way. Because doing this would increase the cost of the

coal at the refueling stations,the main argumentis not affected.

This content downloaded from 185.31.195.106 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 08:23:44 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

478 Cohn

technological considerationsinvolving the use of coal. As will be de-

tailed shortly, early steamships used huge amounts of coal, making

them competitive only on shorterroutes. In Figure 1, steamshipswould

be used on voyages less than L1 in length and sailing ships would con-

tinue to be used on longer voyages. Over time, as steam engines became

more efficient in their use of coal, the voyage cost line for steamships

shifted downward,L1 moved to the right, and steamshipsreplaced sail-

ing ships on longer and longer routes.

This article concernsthe transitionon a specific route ratherthan the

overall transition.The model is designedto explainwhy the steamerdid

not replacethe sailing ship all at once on everyroute.For a specific route,

a straightforwardapplication of the model implies that the transition

shouldoccurfairlyquickly.After all, why shouldthe sailing ship continue

to be used at all on any specific routeonce it becamehighercost? In fact,

the transitiondid occur fairly rapidlyon some otherroutes.For example,

the changeto steam for passengertravelto Quebecoccurredwithin a few

years. As Basil Greenhillsays: "In 1858, 138 sailing ships carried9,104

steeragepassengersfromBritainto Quebecand 16 steamerscarried1,912.

In 1860, 37 steamerscarried6,932 passengers,20 sailing ships carried

904.""17Thus, in a two-yearperiod, the steamshipwent from carrying17

percentto 88 percentof the Quebec passengers.Evidence for routes re-

gardingfreightalso providescases of quick transition.Knick Harleysup-

plies examples of the change to steam in British trade with India and

China after the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 drasticallyshortened

travel distancesto these countries.For India, the percentageof tonnage

moving by steamerincreasedfrom 28 percent in 1870 to 65 percent in

1873; for China,it went from 14 percentin 1869 to 70 percentby 1873.18

The evidence for these otherroutesis consistentwith the transitionmodel

and emphasizesthe slowness of the transitionon the New Yorkroute.19

17 Greenhill, Great Migration,p. 8. Cowan, British Emigration,p. 170, provides slightly lar-

ger figures for all immigrantsto Quebec, includingthose from the Continent.Though the length

is not completely clear from her discussion, the transitionto steam for all Quebec arrivalsmay

have taken a few years longer.

18 Harley, "Shift,"pp. 221-24. The transitionwas less complete on the freight routes. The

reason is that different cargoes were carriedby different ships. For some products, speed was

importantand these items would be shipped by steamer. Seasonal agriculturalproducts, how-

ever, would have to be storedbetween harvestand consumption;the hold of a sailing ship oper-

ated as a warehouseand the slower voyage yielded lower total costs.

19Previous discussions of the length of the transitionon the Europe to New York route are

few. Most researchersview the transitionas occurringgradually,though do not provide much

additionalanalysis. See Albion, Rise, p. 43; Taylor,Distant Magnet, p. 131; Rowland, Steam at

Sea, p. 81; Tyler, Steam; and Hyde, Cunard.In contrast,the most explicit view concerningthe

length of the transitionhas been expressed by Keeling, "Transportation Revolution,"p. 40, who

says that "... the steamers' takeover of the migranttrade from sailing ships was not gradual."

Guillet, GreatMigration,p. 239, also suggests the transitionwas fairly rapid.

This content downloaded from 185.31.195.106 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 08:23:44 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Transitionfrom Sail to Steam 479

In orderto get an accurateidea of how long it took for the transition

on the New York route to occur, one must first determine when the

costs of steam travel for passengers fell below those for sailing-ship

travel. A wide variety of evidence suggests the change occurredduring

the late 1850s. One piece of evidence, just discussed, was that the tran-

sition occurredon the route to Quebec at this time, a voyage of similar

length as that to New York. A second reason for viewing the late 1850s

as the key period is that earliersteamshipcompanies,especially the Cu-

nard and Collins Line, were able to stay in business only because of

governmentsubsidies to carrythe mail.20Their passengerswere limited

to those individualswilling to pay very high prices. In 1856, however,

the Hamburg-AmericanLine began steamer service; in 1857, Inman

switched his line from Philadelphia to New York; and, in 1858, the

North GermanLloyd Line enteredthe market.The Inmantransferwas

particularlyimportantbecause Inman was a company that carriedpas-

sengers in steerage, and this innovationwas rapidlycopied by the other

new entrants.The success of companiesrelying on steeragepassengers,

and with little or no mail subsidy, implies that the costs of passenger

transportationby steamshiphad declined. The need to increaserevenues

even led the conservativeCunardLine to enter the steeragebusiness in

1860.21 As steerage became more prominent, steamships were able to

increase the averagenumberof passengersper voyage from 60 in 1855

to 358 in 1864 (Table 1).

Improvementsin the sailing ship into the middle 1850s also kept the

steamshipat bay until the late 1850s. GeraldGrahampoints to advances

in oceanography, such as improved knowledge concerning seasonal

winds and currents,and declines in the prices for hemp, sail, and cloth

duringthe 1850s that kept sailing ships competitive.22Wages earnedby

shipbuildersin the CanadianMaritimes also declined in the 1850s as

builders of sailing ships struggled to remain competitive.23In addition,

the sailing packets grew in size into the middle 1850s in response to the

increased demand by immigrantsand the growing competition of the

steamship.24 Investment in sailing ships was also encouragedby their

longer life. A sailing ship could expect to continue to operate for 20

years whereas a steamshipbuilt during the 1850s or 1860s had an ex-

pected life of only eight years.25One final item needs to be mentioned.

20Harcourt,"British."

21 Hyde, Cunard, pp. 58-59.

22Graham,"Ascendancy,"pp. 81-82.

23 Harley, "Aspects," p. 173.

24 Guillet, Great Migration, pp. 233-35; Albion, Rise, pp. 43-44; and Hyde, Cunard, p. 60.

25Albion, Rise, pp. 48-49; and Keeling, "Transportation

Revolution,"p. 45.

This content downloaded from 185.31.195.106 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 08:23:44 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

480 Cohn

Beginning in about 1845, attempts were made to equip sailing ships

with a small auxiliary steam engine. The idea was to reduce passage

times by avoiding holdups during periods of calm, but to also have a

ship that did not need to carry as much coal as a regular steamship of

the period. Yet the continued advances in the steamship, discussed in

what follows, led to the abandonmentof these experimentsaround1855

and, in fact, almost no new sailing packetswere built after 1855.26 All in

all, the various developments led contemporaryauthoritiesto express

doubt about the superiority of steam on the north Atlantic route

throughoutthe early and middle 1850s.27 By the end of the 1850s, how-

ever, most doubts had disappeared. In fact, in 1860 the Hamburg-

American Line sold their remainingsailing ships in order to buy more

steamships.28

Technological improvementsin steam transportationalso point to the

late 1850s as being the key period.29 As noted, the inefficiency of the

steam engine in its use of coal was the major cost factor keeping steam

from being more competitive. During the 1820s steamships with low

pressure single-expansion engines operatedwith a normal boiler pres-

sure of 3-5 pounds per squareinch and consumed 10 pounds of coal per

horsepowerper hour. Various improvementsin efficiency lowered fuel

use somewhat over time as did bettertrainingof stokers so they did not

use more coal than was needed or blow off too much steam throughthe

safety valve. By the 1850s coal consumptionby the single-expansion

engine had been reduced to about 4 pounds per hour with a furtherde-

crease to 3.5 pounds by the mid-1860s. Improvementscontinued over

time with the developmentof the compoundengine, which reducedfuel

needs by another30-40 percent.30 In fact, as early as 1862, compound

engines had achieved a boiler pressure of 60 pounds with a fuel con-

sumption as low as 2-2.25 pounds or less per hour. Yet the new type

engine was still basically in the experimentalstage duringthe 1860s and

all the mechanicalproblems were only worked out near the end of the

decade. The compoundengine did not come into generaluse until about

26

Thornton,British Shipping, pp. 51-53; Guillet, Great Migration, pp. 235-38; Coleman,

Going to America,p. 242; and Hutchins,AmericanMaritimeIndustries,p. 320.

27

Tyler, Steam,p. 178; and Smith, ShortHistory, p. 125.

28Fry, History,p. 211.

29 The materialin the next two paragraphsis based on Gardiner,Advent of Steam; Slaven,

"ShipbuildingIndustry,"pp. 110-14; Thornton,British Shipping, pp. 14, 65; Tyler, Steam,

pp. 118-28, 197, 253-56; Rowland, Steam at Sea, pp. 86-101, 119-22; Smith, Short History,

pp. 75-80, 96, 135-38, 168-81; and Headrick,Tentacles,pp. 23-25. It is also useful to note that

coordinationproblems developed with each improvement,as one change did not always work

with the configurationof the rest of the steamship.See Graham,"Ascendancy,"p. 75.

30 The compoundengine reduced fuel use by using a small (second) cylinder to increase the

pressureof the steambefore it passed into the main chamber.

This content downloaded from 185.31.195.106 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 08:23:44 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Transitionfrom Sail to Steam 481

1870, well after the steamshiphad taken most of the passenger traffic

from the sailing ship. Similarly, the surface condenser, which also re-

duced fuel consumption,was not generally adopted until the 1860s.31

Thus, the compound engine and the surface condenser appearto have

simply reinforced the steamship's already-existing advantage on the

northAtlanticroute.

The total costs of a steamshipwere also reducedby the adoption of

iron hulls and screw technology, both of which began to be applied to

steamshipsin the early 1840s. The first transatlanticiron steamshipwas

the City of Glasgow, built in 1850 and put into operationby the Inman

Line, which only used iron ships for carryingpassengers. One problem

that had to be overcome was the fouling of the hulls, which interfered

with the compass. Thus, it was only in the late 1850s that iron came

fully into favor and allowed the building of largerships.32For example,

the CunardLine did not order its first iron steamship(the Persia) until

1855. The use of iron hulls is a second factor, along with the wide-

spread adoption of steerage, that gave rise to the large increase in the

average passenger load that occurred between 1855 and 1864.33The

screw was potentially much more efficient than the paddlewheel since

the entire screw was submergedcomparedto only part of the paddle-

wheel. But early problems existed in where to place the screw in the

ship, in whetherto power it from the steam engine directly or indirectly,

in keeping water from seeping in where the screw exited the ship, and in

devising a system to lift the screw out of the water when the captain

wanted to use the sails. Though the British Admiraltycommittedto the

screw in 1845, most of the problemswere not fixed until the middle or

the late 1850s; for example, the leakage problem was solved in 1855.

Again, one of the first adoptersof the screw was the InmanLine and the

City of Glasgow was one of the first ships to use them. Most other com-

panies rapidly adopted the screw for new ships. The conservative

CunardLine continued with paddle steamers longer than others. Even

Cunard,however, adoptedscrew technology after 1861.34

31The surface

condensercollected the used steam and reducedit back to (hot) water.

32Davies, "Development,"p. 179.

33 During the 1850s iron was used mainly for the constructionof passenger steamships or

small experimentalwar vessels. In the United Kingdom,total new iron constructionon all types

of shipping outweighed new wood constructionin shipping for the first time duringthe 1860s.

See Graham,"Ascendancy,"pp. 75-77; and Davies, "Development,"p. 200.

34The location of the screw proved to be a problemduringthe 1860s as its placementproved

noisy for cabin passengerswhose rooms and saloons were traditionallyin the stern of the ship.

It was not until 1870 that the White Star Line rearrangedthe interiorof the ship to reduce the

noise and motion arising from the operation of the screw. See Gould, "Ocean Passenger

Travel,"pp. 126-27.

This content downloaded from 185.31.195.106 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 08:23:44 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

482 Cohn

Perhapsthe best evidence thatthe steamshiphad become competitive

with the sailing ship comes from limited informationconcerning rela-

tive fares. It is generally thoughtthat travel by sailing ship from Liver-

pool cost ?3 10s to ?5 after 1830, with no long-runtrend,and fares from

the Germanports may have risen duringthe 1840s and 1850s.35Consis-

tent fare informationis not available for travel by steamship until the

1880s, though a variety of partial estimates exist for the time period of

interest and these are shown in Table 4. Until late in the 1850s, with a

few exceptions, one could travel on steamshipsonly as a cabin passen-

ger, and the rates reflect this fact. Thus, as is well known, the steamship

first took high-ratepassenger and freight travel away from the sailing

ship.36The technological improvementsin the steamship, the entry of

new lines, and the adoptionof steerage led to a large fall in the relative

price of steamshiptravel by the late 1850s.37 Yet the informationin Ta-

ble 4 indicates that steamship fares generally remainedabove or at the

upper end of fares on sailing ships. Edwin Guillet summarizesthis in-

formation by saying that passage by steam generally cost one-third

more than passage by sail even afterthe changes discussed.38Even later

in the 1860s, the money fare via steam never fell to that via sail. Over

the entire time period, however, individuals continued to switch to

steam because the quicker,safer, and more comfortablevoyage reduced

an immigrant'stotal opportunitycosts.39 Thus, by the late 1850s, steam

fares had apparentlydeclined enough to make the steamship competi-

tive with the sailing ship for passenger travel. Yet the sailing ship did

not disappearas a means of passenger travel on the northAtlantic until

1874, about 15 years after the steamshipbecame the low-cost means of

travel.

FORA SLOWTRANSITION

EXPLANATIONS

The previous sections suggest the transitionfrom sail to steam in the

Europeto New York route was more gradualthan a straightforwardap-

plication of the transitionmodel would suggest. This section examines

four factorsthat could lead to a slow transitionon a specific route. First,

immigrantshad a choice in whetherto spend the extra money to obtain

a faster voyage. Essentially, poorer immigrantsmight have chosen the

35 Gould, "European,"p. 612; and Page, "Transportation," pp. 737-38.

36Cohn, "Transatlantic."

37Tyler, Steam,p. 267.

38 Guillet, GreatMigration,p. 239. Thomas,Migration,p. 96, cites figures for 1863 of ?4 15s

for steamshipsand ?2 17s for sailing ships, but providesno referencefor them.

39Gould, "European,"pp. 613-14.

This content downloaded from 185.31.195.106 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 08:23:44 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Transitionfrom Sail to Steam 483

TABLE4

STEAMSHIPFARES

Date CabinFare SteerageFare OtherInformation

middle 1840s ?30-38 various companies

1846 ?39 to Boston

1850 ?13 13s - ?23 is InmanLine to Philadelphia

1850s ?35 first class; from Liverpool

?20 second class

1853 ?8 16s InmanLine; limited numbers

1856 ?12 ?7 from Glasgow

1857 ?30 based on shippingadvertisements

1858? ?7 Irishpassengerson Galway Line

1860 ?8 8s based on shippingadvertisements

1863 ?6 6s based on shippingadvertisements

1863 ?5 5s on Hibernia from Ireland

1863? as low as ?3 15s on China

1875 ?5 to ?5 5s set by agreement

Sources: Rows 1, 8, 11, 12: Tyler, Steam, pp. 165, 267, 288, 290. Rows 2, 4, 7, 9, 10, 13: Hyde,

Cunard, pp. 40, 42, 64, 80, 97. Row 3: Bowen, Century,p. 62. Row 5: Coleman, Going to

America,p. 238. Row 6: McLellan,AnchorLine, p. 19.

sailing ship because of an income constraint,sacrificing time to save

money. Clearly, this sort of mechanism was at work during the early

1850s when only those passengers who could afford the high cost of

travelingin a cabin took a steamship.In addition,a tradeoffof time for

money may explain why Bremen, throughwhich poor immigrantsfrom

central and eastern Europe left at this time, was the main holdout for

sailing ships in 1873.40 Yet this line of reasoning would better explain

why steam did not completely win out between Europe and New York

than why it was adoptedslowly. Thoughthe introductionof steerage on

steamships made them more affordable to immigrants, without in-

creases in immigrant incomes or continual reductions in the relative

price of steam travel, the likely outcome would have been a situation

where sail indefinitely kept some portion of the north Atlantic immi-

grantmarket.It is unlikely that immigrantincomes went up very much

over the course of the decade of the 1860s nor was the innovationof re-

ceiving prepaid tickets from relatives in America new. Informationis

not extant concerning the relative prices of steam and sail throughout

the 1860s, though as shown in Table 4, it is believed there was little

trend.41Moreover,in 1867/68 the major steamshipcompanies agreed to

40 This

explanationis speculative. It is supportedby the fact that, during 1873, almost 10,500

immigrantsenteredthe United States from the presumablypoorer areas of Poland and Austria-

Hungary.Between 1870 and 1872 only 4,500-6,000 arrivedyearly from these areas. See U.S.

Department of the Census, Historical Statistics, Series C94 and C95.

41

Also, see Gould, "European,"pp. 611-13.

This content downloaded from 185.31.195.106 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 08:23:44 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

484 Cohn

set minimum passenger fares.42 Both factors make it unlikely the rela-

tive price of steam travel declined sufficiently to allow poorer immi-

grants, who could not afford to travel by steam early in the decade, to

suddenlybe able to affordthe steamship.

The second possibility is subject to the same general criticism. Theo-

retically, continued technological improvementsin steam power could

have reduced the relative price of steam transportation,making the

steamship a progressively better value. Yet we have just seen that the

relative price of steam travel did not fall during the 1860s, so this ex-

planationcannotbe true.

A third factor that could possibly explain the slow switch to steam

travel is that sailing ships lowered prices in response to the decreased

demandfor their service. After all, simple economics suggests a sailing-

ship firm would continue to carrypassengers as long as the fares cov-

ered the variablecosts of operation.Though data on fares are not avail-

able, it is unlikely this situationprevailedfor the passengertradeon the

north Atlantic. The sailing ships were not stuck carryingpassengers on

the northAtlantic. Ownerscould have moved their sailing ships to more

profitable routes had sailing ship fares declined.43In addition, sailing

ships could have been converted to carrying freight more easily than

could steamships, which used a large amount of their space on fixed

cabin accommodations.Given the ability to switch sailing ships to other

routes or purposes, and given the minimum fares set for steamship

travel in the late 1860s, it is probablethe sailing ships continuingin the

northAtlanticpassengertraderemainedprofitable.

The fourth explanationviews the transitionas an example of capital

replacementthat did not occur quickly. The steamshipwas an expensive

piece of capital, one that took six to nine months to build.44The actual

decision to constructa new passenger steamshipwas made by a steam-

ship company that contractedwith a shipyard.The company's decision

process would be influenced by a number of factors: expected future

passenger demand, currentand expected technological changes, plans

by currentcompetitors,expected entry, and any agreementswith com-

42 Hyde, Cunard, p. 94. The original

agreement was between Cunard and Inman, though

Hyde says the otherLiverpool-basedlines also joined. The effectiveness of the agreementis not

clear, because the lines based on the Continentdid not belong and many of their ships boarded

passengersin ports in southernEngland.

43Large-scaleimmigrationhad begun to Australiain 1852 as a result of the discovery of gold

in that country, so ships could have been moved to that route. See Thornton,British Shipping,

p. 42. In addition,duringthe Civil War, many sailing ships were sold to the North's government

for use in the war effort. See Dyos and Aldcroft,British Transport,p. 237; and Jones,American

Immigration, p. 158.

44 Slaven, "Shipbuilding Industry," p. 120.

This content downloaded from 185.31.195.106 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 08:23:44 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Transitionfrom Sail to Steam 485

petitors.45In particular,at about the time the steamer became the pre-

ferredcarrier,the volume of immigrationbegan to increaserapidly.The

increase was sufficiently large that much of it would not have been an-

ticipatedby existing and potential steamshipcompanies. The result was

that steamship constructionwas consistently too small to completely

catch up with the continually growing immigration.Sailing ships then

kept the residualtraffic,with their sharefalling over time as the number

of steamships increased and slowly caught up to the larger volume of

immigration.46

The emphasis on immigranttraffic disregardsany importantrole for

revenues the steamship companies could earn from operating sailing

ships or from carryingfreighton passengerships. Each item was of lim-

ited importance.In particular,each steamship company carrying pas-

sengers to New York did so only on steamships,that is, by the 1860s,

the remaining sailing ships were operatedby separatecompanies.47 As

to freight, though some was carriedby every steamship,the ships were

designed with passengers in mind, and passenger traffic was the main

source of revenue from the use of these ships.48In addition, once built

for passengertraffic, a steamshipwas used exclusively for this purpose.

Though a few steamshipswere eventuallytaken out of passengertraffic

and converted to carrying freight, no back-and-forthconversions oc-

curred.In other words, most steamshipscarryingfreightwere explicitly

built for that purpose. Thus, the demand for passenger steamships can

be analyzedindependentlyof the demandfor freighters.

ANALYZINGTHERATEOF STEAMSHIP

CONSTRUCTION

To the best of my knowledge, no estimates exist on the total tonnage

or new constructionof passenger steamships.Though data are available

on the total steamship tonnage in Great Britain, these figures are not

45 The directionof influence is not always simple to determine.For example, the literatureis

filled with situationswhere new ships built by one firm incorporatedimprovementsfor passen-

gers, and caused other firms to ordernew ships in response. A similar argumentapplies to the

entry of new firms.

46Hyde, Cunard,p. 63, discussing the 1860s, says that duringthe peak season from April to

September".. . there was usually insufficient tonnage and overcrowdingin years of high emi-

gration."In 1873, of the 26 sailing ships that carriedover 100 passengers, 18 (69 percent) ar-

rived between April and August. Only 45 percentof the steamshipsarrivedduringthe same pe-

riod. It is not clear, however, whether sailing ships arrived during these months due to the

availabilityof passengersor whethersailing conditionswere betterduringthis partof the year.

47The one exception was the heavily-subsidizedFrenchCGT Line, which continuedto oper-

ate sailing ships until 1873.

48 Hyde, Cunard,p. 82, in discussing the determinantsof profits before 1874 says the "pas-

senger trade had become the definitive element" in determiningthe profitabilityof the steam-

ship companies.

This content downloaded from 185.31.195.106 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 08:23:44 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

486 Cohn

350,000-" " NY Arrivals Tonnage 120,000

300,000- *

I' 100,000

250,00-0

200,000 ?

60,000

Z 150,000 S, I

-40,000

10000020000

50,000 ' 20,000

n 't

e0 n .

o

o". or or o4

o0 1-

o0 o0 o0 0

FIGURE2

NEW YORK ARRIVALSAND CONSTRUCTIONBY NEW YORK-BOUND LINES,

1838-1875

Sources: Data on "New York Arrivals"from Bromwell, History, table 1 for various years, and

U.S. TreasuryDepartment,Arrivals, table 7, p. 83, adjustedby informationin Table 4 for the

years beginning in 1868. The arrivalsdata are for calendaryears except: 1843, which is for the

first nine months of the year; 1844-1849, which are for 12 months ending in September;and

1850, which is for 15 months. The steamshiptonnage data are primarilyfrom Bonsor, NorthAt-

lantic Seaway.

useful for our purposes because, as just noted, passenger-carrying

steamships were different from freight-carryingsteamships.49 In addi-

tion, Grahamindicates the Lloyd's Register list is far from complete.50

Consequently,new estimates of passengersteamshiptonnagehave been

constructedfor each year from 1838 through 1875. These are shown in

Figures 2 and 3. The new estimates are based on published sources that

specify the year each steamshipwas built, the name of the ship, and its

gross tonnage.51The estimates in Figure 2 include steamshipsbuilt only

for those companiesthat carriedpassengersto New York at some point

49 Harley, "Aspects,"p. 171; and Palmer,"BritishShippingIndustry,"pp. 92-93, provide es-

timates for total shipbuildingand ship registrationin Britain.

50 Graham,"Ascendancy,"p. 74.

5 Bonsor, North Atlantic Seaway, has comprehensivelists of ships used by each company

carryingpassengers on the north Atlantic, along with their date of launchingand tonnage. Ma-

ber, North Star, provides similar lists for companies serving Asia and Australia. I have not

found any sources for companies serving South America,so my estimatesmay be missing some

ships here. The estimates do not include the 18,915 ton Great Eastern constructedin 1858,

which was considereda "freak"at the time, never carriedmany passengers, and seems to have

had no subsequent effect on the constructionof steamships. See Thornton,British Shipping,

p. 55.

This content downloaded from 185.31.195.106 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 08:23:44 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Transitionfrom Sail to Steam 487

500,000 200,000

" Immigration Tonnage

450,000- 180,000

400,000- 160,000

350,000 140,000

120,000 g

"300,000 ,

s 250,000

1 100,000

-

200,000- , , 80,000

150,000- ' 60,000

100,00-0 40,000

50,000- * 20,000

00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

FIGURE3

TOTALU.S. IMMIGRATIONAND TOTAL STEAMSHIPCONSTRUCTION,

1838-1875

Sources: Immigrationdata through1867 are from U.S Departmentof Census, Historical Statis-

tics, Series C89. Data for 1868 through 1875 from U.S. TreasuryDepartment,Arrivals, table 4,

p. 58. The immigrationdata are for calendar years except: 1843, which is for the first nine

months of the year; 1844-1849, which are for 12 months ending in September;and 1850, which

is for 15 months. The steamshiptonnage data are primarilyfrom Bonsor, North Atlantic Sea-

way, and Maber,North Star.

between 1852 and 1876. Those in Figure 3 include steamshipsbuilt by

any company. Though certain companies specialized in the New York

trade, all companies bought and sold steamers and reallocated them

among their routes. Thus, both sets of estimates are useful. Figure 2 in-

cludes data on 394 passenger-carryingsteamships. Figure 3 contains

dataon 539.

The determinantsof steamship construction can be analyzed using

regression analysis.52 The dependentvariable is yearly tonnage of new

steamshipconstruction,either for all companies or just for those sailing

to New York. Given that immigrationto the United States was the larg-

est source of demand for passenger travel, one would expect the build-

ing of passenger-carryingsteamshipswould be closely relatedto lagged

immigrationto the United States. It is not clear, however, whether the

relationshipwould be to total immigrationor to immigrationto New

52

The approachtaken here is consistentwith the discussions in Slaven, "ShipbuildingIndus-

try,"pp. 114-16; and Brattne,"Importance,"pp. 197-99.

This content downloaded from 185.31.195.106 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 08:23:44 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

488 Cohn

York City. Thus, Figure 2 includes data on arrivalsat New York, and

Figure 3 includes data on total immigration.Both figures show there is

an apparentdirect relationshipbetween constructionand immigration.

In addition, to account for the hypothesis that the steamship was the

preferredmode of travel and not enough steamshipsexisted, the regres-

sion includes a time trendvariable.Finally, a dummy variableis added,

taking on a value of one beginning in 1870. This variablerepresentsthe

opening of the Suez Canal and the introductionof the compound en-

gine, both of which spurredsteamshipconstruction.53 As few passengers

traveledby steamshipbefore 1850 and essentially all did after 1873, the

regressionswere run over the period from 1850 through 1873. The OLS

results of the various specificationsare presentedin Table 5.54 All inde-

pendent variables are statistically significant in all of the regressions,

though in a few cases only marginally.

Suppose the volume of immigrationto the United States (or New

York) increasedby 100,000 duringone year of the 1860s. The response

to this increase shows up in the coefficients on immigrantvolume and

the yearly trend. To calculate the maximum constructionresponse dur-

ing the 1860s, use the values in column 2, which includes all steamship

companies and accounts for the discontinuityarising from the adoption

of the compound engine and the opening of the Suez Canal. Then, the

increase of 100,000 in the total volume of immigrationwould increase

new steamship tonnage the next year by about 12,562 tons. Given the

average steamshiptonnage of 2350 tons, the total response would equal

5.35 new steamships. Yet this response is fairly small. If each newly-

built ship made an average of six voyages per year and carried600 pas-

sengers per voyage, then the new steamships would increase capacity

by only about 19,250, or only about one-fifth of the increase in de-

mand.55Indeed, the responsewould be even smallerbecause all the new

steamships would not necessarily be used to carry passengers on the

53 Graham,"Ascendancy,"p. 83. No attempt is made to include the 1867 agreementto set

minimumfares among the Liverpool-basedcompanies. As noted earlier,the effectiveness of the

agreementis not clear.

54 The results do not measurablychange if the numberof new steamships is used instead of

total new tonnage, if total immigrationis not lagged, if a dummy variable is included for the

Civil War years, if the regression is continued through 1875, or if a year-squaredterm is in-

cluded. The use of OLS is supportedby tests of Grangercausality (not reported),which indicate

the lagged immigrationvariablecauses tonnage but tonnage does not cause lagged immigration,

and tests of cointegration(also not reported)thatreveal no problems.

55 The figures used for the average number of voyages and the average passenger load are

both greaterthan the averages calculatedfrom Table 1, but then the ships being discussed were

new. For example, 31 passenger steamshipswere built in 1865 and 19 (61 percent)of them car-

ried passengersto New York in 1867. The maximumload averaged586 passengers,the average

load was 449 passengers,and each ship averaged5.3 voyages.

This content downloaded from 185.31.195.106 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 08:23:44 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Transitionfrom Sail to Steam 489

TABLE 5

REGRESSIONRESULTS, 1850-1873

(t-statisticsin parentheses)

DependentVariable

Total Tonnage Tonnage for U.S. SteamshipCompanies

Variable (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6)

Constant -44,366 -16,719 -18,570 -5,008 -19,448 -6,339

Lagged total 0.165 0.102 0.075 0.044

immigration (3.76) (2.08) (3.05) (1.56)

Lagged - -- 0.102 0.066

arrivals at (2.97) (1.87)

New York

Yeartrend 3,756 2,362 2,580 1,896 2,625 1,875

variable (5.57) (2.70) (6.85) (3.77) (6.92) (3.68)

Suez canal/ 41,107 - 20,164 - 21,530

compound (2.24) (1.92) (2.28)

engine

dummy

R2 0.69 0.75 0.73 0.78 0.73 0.79

F-value 23.38 20.25 28.95 22.98 28.34 24.38

Notes: The steamship constructionand immigrationvariables are from the same sources as in

Figures 2 and 3. The year trendvariableis given the value of unity in 1850 and increasesby one

each year. The Suez Canal/CompoundEngine dummy takes on a value of unity for each year

beginningin 1870.

north Atlantic.56Of course, additionalships already in existence could

be switched to the northAtlantic from otherroutes, eitherby companies

already serving the route or by the entry of new companies. The infor-

mation in Table 2 indicates that new companies did enter the market

fairly regularly. Even so, the relatively small construction response

would make it difficult for steamshipcompanies to meet passenger de-

mand in a period of rapidlyrising immigration.

If the passenger demandfor steamshiptravel unexpectedly increased

and outstrippedthe supply of steamships through 1873, then profits

should have been above the normal level for steamship companies.

Some evidence exists to supportthis implication.Hyde presents figures

indicatingthe companiesmade large accountingprofits through 1873.57

A more obvious implicationof above normalprofits is that entry should

occur. The informationin Table 2 shows that the numberof companies

carryingpassengers to New York increased from five in 1861 to 16 in

1873. Though many of the new firms serviced the Liverpool route, all

56

Redoing the calculationusing the coefficients in columns 4 and 6, which providethe results

only for those companies travelingto New York, yields a response of 2.7 and 3.6 new steam-

ships, respectively.

57Hyde, Cunard,pp. 79-82.

This content downloaded from 185.31.195.106 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 08:23:44 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

490 Cohn

of the major routes saw attempts by new firms to enter the market.58

Then, when demandand passenger revenues fell after 1873, accounting

profits plummeted and some of the firms exited, furtheremphasizing

the key role of passenger demand in explaining the demand for steam-

ships.

The reasons for the small constructionresponse are not completely

clear. Because the volume of constructionjumped so dramaticallyin the

early 1870s, the problem does not appearto be a lack of productionfa-

cilities. Instead, the likely causes were uncertaintyconcerningboth fu-

ture technological changes and the volume of immigration.As noted

earlier, experimentswere continuing on the compound engine during

the 1860s. Given the strong likelihood the engine would be perfected in

the not-too-distantfuture, companies may have wanted to avoid build-

ing too many steamships that might soon become obsolete, or at least

requireextensive renovations.Certainly,the huge increasethat occurred

in the volume of constructionin the early 1870s once the compounden-

gine had been perfected, shown by the large positive coefficient on the

Suez Canal/CompoundEngine dummy variable in the regression re-

sults, suggests this factor may have been important.In addition, given

the history of immigrationto that time, it is not hard to see why immi-

grant volume would be consistently underestimated.Before the potato

famine, the volume of immigrationwas fairly small, averagingless than

80,000 each year between 1836 and 1845. Average yearly volume

jumped to over 300,000 during the 1846 to 1854 period, but the large

increase was clearly due to the potato famine, an event not likely to be

repeated. Between 1855 and the outbreak of the Civil War, average

yearly volume declined to 175,000. The companiesanticipatedthat vol-

ume would pick up after the Civil War,but to what extent would not be

clear. In fact, averagevolume between 1865 and 1868 was 290,000, vir-

tually as large as during the potato famine, but with no upwardtrend.

Then, between 1869 and 1873, average volume jumped again and al-

most reached 400,000, surpassing the 1854 record. Determining the

numberof steamshipsto build in an environmentof fairly rapidtechno-

logical change and unpredictableimmigrantvolume must have been ex-

traordinarilydifficult. In such a situation,it is not surprisingthe steam-

ship companiestook a conservativeapproach.

Even given the conservativeapproachof the steamshipcompanies to

building new steamships, the transition would have been completed

58 For example, the New York and Bremen Line provided competitionfor the North German

Lloyd Line in 1867, the Adler Line provided competition for the Hamburg-AmericanLine in

1873, and the Union MaritimeLine and the National Line provided competition for the CGT

Line from Le Havre. See Bonsor,NorthAtlanticSeaway.

This content downloaded from 185.31.195.106 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 08:23:44 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Transitionfrom Sail to Steam 491

much more rapidly in the absence of the rising volume of immigration.

In 1861, only 21,000 of the 70,000 passengers arrived on steamships

(Table 1). In 1864, 78,000 passengers arrivedon steamships,more than

the total arrivals in 1861. In 1864, total arrivals at New York City

equaled 174,000; in 1867, 193,000 arrived on steamships, more than

both the total in 1864 and the average yearly number that arrivedbe-

tween 1855 and 1860. In turn, if we consider the transitionon the Que-

bec route, the volume of immigrationwas small and little change oc-

curredin its size into the early 1860s. In this case, when a number of

new steamship firms began carryingpassengers to Quebec during the

late 1850s, the transitioncould be, and was, very rapid. Given a stable

demand, these steamship companies could more easily determine the

numberof steamshipsneeded to service all, or at least the vast majority,

of passengerson the Quebec route.59

In all cases, the steamship did not replace the sailing ship because

immigrantvolume was increasing. Rather, the steamship replaced the

sailing ship because of passenger demand for a safer, quicker trip. On

the Quebec route, without much change in volume, the transitionwas

rapid. On the New York route, with volume continually increasing

through1873, the transitionwas much slower.

EXPLAINING TONEWYORK

THETRANSITION

Previouswork on the transitionfrom sail to steam on the northAtlan-

tic duringthe nineteenthcenturyhas emphasizedtechnological change,

a supply factor, as key. In fact, every previous discussion is similar. The

introductionof iron hulls and screw technology, improvementsin fuel

use in single-expansion engines, and the adoption of steerage allowed

steamshipsto begin to take the passengertrade away from sailing ships

by the late 1850s. The 1860s saw the introductionof the surface con-

denser and, at the end of the decade, the compound engine. The length

of the transitionis usually ignored or viewed as occurringquickly. The

discussion in this article certainlydoes not disagreewith the importance

of technological change to understandingthe transitionto steam in the

northAtlantic. However, an analysis of technological change is not suf-

ficient to completely understandthe transitionwhich, in other circum-

stances, could have occurred much more quickly. A complete under-

standing requires informationon the demand for passenger travel, the

59TOthe best of my knowledge, only one steamshipcompany, the Anchor Line, carriedpas-

sengers directly to both New York and Quebec during the late 1850s and early 1860s, though

some of the New York companies carriedpassengersto Halifax. A numberof other steamship

lines served Quebec but not the New York market.

This content downloaded from 185.31.195.106 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 08:23:44 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

492 Cohn

factors that influenced the constructionof steamships, and the rate at

which the new technology was adopted.Only by includingthese factors

can we understandwhy it took 15 years for the steamshipto completely

replacethe sailing ship as a carrierof passengerson the northAtlantic.

The findings of this article, especially the informationin Table 1 and

Figure 3, can be used to more fully explain developmentsin the market

for passenger travel on the north Atlantic between the 1850s and the

1870s. Passenger steamship constructionrose rapidly during the first

half of the 1850s in response to the huge volume of immigrationat the

time. A peak in constructionis apparentin 1855, the year in which the

volume of immigrationunderwenta precipitous decline. Even though

the steamshipwas just becoming fully competitivewith the sailing ship

about 1858, the decline in total immigrantvolume meantthat 20 percent

of the immigrantsarrivedat New York City that year on a steamship.

Immigrantvolume remainedrelatively small into the early 1860s so, by

1864, the continued slow pace of steamship construction,the growing

use of steerage, and the general adoption of iron hulls had led to a siz-

able increase in the total number of passengers arrivingby steamship.

Yet the construction response was not large enough to drive sailing

ships out of the north Atlantic market.Even though the percentage of

passengers traveling by steam had risen to 45 percent in 1864 from 31

percent in 1861, the actual number of passengers arriving on sailing

ships was much largerin 1864 (96,000) than in either 1858 (69,000) or

1861 (48,000).

Immigrantvolume began to increase during 1863, perhaps in antici-

pation of the end of the Civil War and the resumptionof more normal

economic conditions. Steamshipconstructionalso picked up, peaking in

1865, and a numberof new firms enteredthe market.Immigrantvolume

continued to increase into 1866, then stagnated through 1868, and

startedto rise again only in 1869. As a consequence, in 1867, 47,000

passengers,nearly as many as in 1861, still arrivedon sailing ships. The

slow growth in immigrantvolume duringthe late 1860s, and the pend-

ing adoption of the compound engine, contributedto a decline in the

rate of new steamship constructionat this time.60 The continued con-

structionof some new steamships, however, along with the stagnation

in immigrantvolume, caused the numberof immigrantsarrivingby sail-

ing ship to decline to 32,000 in 1870. In addition,the sailing ships built

in the early 1850s to carrypassengersto North America may have been

reaching the end of their useful life. Immigrantvolume began to in-

crease once again in 1869, the year the Suez Canal opened and the

60 Slaven, "ShipbuildingIndustry,"p. 116.

This content downloaded from 185.31.195.106 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 08:23:44 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Transitionfrom Sail to Steam 493

compoundengine began to be used. These factors led to a boom in the

constructionof new steamshipsand the entry of a large numberof new

steamship firms into the north Atlantic market.By 1873, 97 percent of

passengers arrivedat New York on a steamshipwith total sailing ship

passengersfalling to 8,000.

The result of the interplaybetween rising immigrantvolume, techno-

logical changes, and a small constructionresponse was that the transi-

tion to steam on the northAtlantic passengerroute took almost 15 years

to complete. The large increase in passenger volume occurredafter the

steamship became truly competitive with the sailing ship in the late

1850s and meant that a large number of new steamers needed to be

built. With uncertaintyover how much immigrantvolume would con-

tinue to rise, when the compound engine would be perfected, and how

many new firms would enter the market, the demand for new steam-

ships lagged passengerdemand.Consequently,it took a large numberof

years for steamship capacity to catch-up with the generally growing

volume of immigration.Only when the volume again began to rise in

the early 1870s was a sufficient numberof ships built to handle the en-

tire demand. At just about the time when enough steamshipshad been

constructed, however, the market collapsed with the depression of

1873.61 The situationrapidly changed from a lack of passenger steam-

ship capacity to one of substantialexcess capacity. The result was a

huge decline in the constructionof new steamships,the abandonmentof

the New York market by some steamship companies (or their bank-

ruptcy), and the end of the sailing ship as a carrierof passengerson the

northAtlantic.

61

Ibid., pp. 114-16. In discussing the capital-goodsshipbuildingindustry,Slaven uses similar

reasoningwhen he says it exhibited ".... a tendency to over-capacityin shipbuilding."He spe-

cifically discusses the overbuilding during the 1868-1874 period. When immigrant volume

again increased,the numberof new ships did not increase at the same rate. Keeling, "Transpor-

tation Revolution,"pp. 52-53, makes the point that steamship lines concentratedon building

more ships up to 1873 and bigger ships afterthat date.

REFERENCES

Adams, John. Ocean Steamers:A Historyof Ocean-goingPassenger Steamships,1820-

1970. London: New Cavendish Books, 1993.

Albion, Robert Greenhalgh. The Rise of New York Port (1815-1860). Boston:

NortheasternUniversityPress, 1984 (reprintof 1939 edition).

Bonsor, N. R. P. North AtlanticSeaway. 3 volumes. New York: Arco PublishingCo.,

1975.

Bowen, FrankC. A Centuryof Atlantic Travel,1830-1930. Boston: Little, Brown, and

Co., 1930.

Brattne, Berit. "The Importanceof the TransportSector for Mass Emigration."In

This content downloaded from 185.31.195.106 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 08:23:44 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

494 Cohn

From Sweden to America:A History of the Migration,edited by HaraldRunblom

and Hans Norman, 176-200. Minneapolis:Universityof MinnesotaPress, 1976.

Bromwell, William J. History of Immigrationto the United States. New York: Arno

Press, 1969 (reprintof 1856 edition).

Cohn, RaymondL. "Transatlantic U.S. PassengerTravelat the Dawn of the Steamship

Era."InternationalJournalof MaritimeHistory4, no. 1 (1992): 43-64.