Professional Documents

Culture Documents

2015 - Pizzo - Should We Practice What We Profess - Care Near The End of Life

Uploaded by

Bê LagoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

2015 - Pizzo - Should We Practice What We Profess - Care Near The End of Life

Uploaded by

Bê LagoCopyright:

Available Formats

PE R S PE C T IV E Breast-Density Legislation

variably refer patients with dense most efficacious. For example, Disclosure forms provided by the authors

are available with the full text of this article

breasts for whole-breast ultra- some practices now use digital at NEJM.org.

sound screening, with some prac- breast tomosynthesis, which

tices referring 100% of such leads to increased cancer detec- From the Department of Radiology, Beth

Israel Deaconess Medical Center (P.J.S.),

women and others referring none. tion while limiting the need for Harvard Medical School (P.J.S., P.E.F., R.L.B.),

Furthermore, only 45% of Con- additional imaging in women the Department of Radiology, Massachu-

necticut women who were re- with dense breast tissue, accord- setts General Hospital (P.E.F.), and the De-

partment of Radiology, Brigham and Wom-

ferred for follow-up ultrasonog- ing to preliminary data. en’s Hospital (R.L.B.) — all in Boston.

raphy actually received it.5 Still, Having dense breast tissue

1. Kerlikowske K, Hubbard RA, Miglioretti

breast-density legislation provides does increase a woman’s lifetime

DL, et al. Comparative effectiveness of digital

an opportunity to strengthen risk of breast cancer, but it’s im- versus film-screen mammography in com-

patient–provider relationships by portant for providers to place munity practice in the United States: a cohort

study. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:493-502.

encouraging physicians to engage this risk in perspective for each

2. Smith RA, Duffy SW, Gabe R, Tabar L,

women in a conversation about patient. Risk stratification will Yen AM, Chen TH. The randomized trials of

the risks and benefits of screen- be an essential tool in determin- breast cancer screening: what have we

learned? Radiol Clin North Am 2004;42:793-

ing, regardless of breast density. ing the best screening plan for

806, v.

In this era of cost contain- each woman. It would be helpful 3. Tice JA, Ollendorf DA, Lee JM, Pearson

ment, and given the limited data if the medical community could SD. The comparative clinical effectiveness

and value of supplemental screening tests

supporting screening ultrasonog- reach a consensus on how best

following negative mammography in women

raphy, a rational and cost-effec- to advise women with dense with dense breast tissue. Institute for Clinical

tive approach to screening is breasts with regard to the limita- and Economic Review, 2013 (http://www

.ctaf.org/sites/default/files/assessments/

needed. So how should the medi- tions of various screening tests

ctaf-final-report-dense-breast-imaging-11.04

cal community address the grow- and the role of any supplemen- .2013-b.pdf).

ing concern over breast density tal screening. Then, practitioners 4. Berg WA, Blume JD, Cormack JB, et al.

Combined screening with ultrasound and

and breast-cancer detection? It is could base patient care on exist-

mammography vs mammography alone in

An audio interview critical that radiolo- ing evidence and each woman’s women at elevated risk of breast cancer.

with Dr. Slanetz gists work with individual risk. Such an approach JAMA 2008;299:2151-63.

is available at NEJM.org other specialists might well maximize cancer 5. Hooley RJ, Greenberg KL, Stackhouse RM,

Geisel JL, Butler RS, Philpotts LE. Screening

and primary care physicians to detection and minimize the

US in patients with mammographically

develop evidence-based recom- downsides of screening — espe- dense breasts: initial experience with Con-

necticut Public Act 09-41. Radiology 2012;

mendations regarding situations cially false positives and the

265:59-69.

in which supplemental screening risks of overdiagnosis and over- DOI: 10.1056/NEJMp1413728

is advisable and which method is treatment. Copyright © 2015 Massachusetts Medical Society.

Should We Practice What We Profess? Care near the End of Life

Philip A. Pizzo, M.D., and David M. Walker, B.S.

P hysicians should be in a bet-

ter position than people

without medical training to judge

ated from Johns Hopkins School

of Medicine between 1948 and

1964, revealed that 70% had not

ences were expressed in a 2013

survey of 1147 younger academic

physicians (a group that was more

the likely value of health care ser- had a conversation with their own diverse and included more women):

vices available near the end of personal physician about end-of- 88.3% indicated that they would

life. Yet several studies have re- life care. But 64% had an advance forgo high-intensity end-of-life

vealed a disconnect between the directive that they’d discussed treatment.2

way physicians themselves wish with their spouse or family, and Although physicians ought not

to die and the way the patients more than 80% indicated that assume that their views about

they care for do in fact die. they would choose to receive pain dying should apply to others,

A 1998 survey of participants medication but would refuse life- public surveys and research stud-

in the Precursors Study, which en- sustaining medical treatments at ies have shown that 80% of

rolled 999 physicians who gradu- the end of life.1 Similar prefer- Americans, like the large majority

n engl j med 372;7 nejm.org february 12, 2015 595

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org at UNB on March 10, 2015. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2015 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

PERS PE C T IV E Care near the End of Life

Teno et al. noted that the rate of

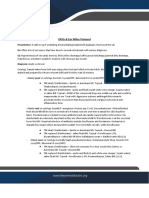

Summary of IOM Committee Recommendations.* acute care hospitalization de-

creased from 32.6% in 2000 to

Delivery of care 24.6% in 2009 but that use of in-

Government health insurers and care delivery programs, as well as tensive care in the last month of

private health insurers, should cover comprehensive care, including life increased from 24.3% to

palliative care and hospice care for persons with advanced serious 29.2%.3 Although hospice use in-

illness who are nearing the end of life.

creased during this period,

Clinician–patient communication and advance care planning 28.4% of the decedents studied

Professional societies and other organizations should develop stan- had used hospice for 3 days or

dards for clinician–patient communication and advance care plan- less in 2009.

ning that are measurable, actionable, and evidence-based. Payers Complex social, cultural, eco-

and delivery organizations should adopt these standards and their nomic, geographic, and health

supporting processes and integrate them into assessments, care system factors and impediments

plans, and the reporting of health care quality. contribute to this discordance be-

tween how doctors treat their pa-

Professional education and development tients and how they themselves

Educational institutions, credentialing bodies, accrediting boards, state (and the majority of surveyed

regulatory agencies, and health care delivery organizations should Americans) wish to be cared for

establish appropriate training, certification, and licensure require-

at the end of life. We are experi-

ments to strengthen the palliative care knowledge and skills of all

clinicians who care for patients with advanced serious illness who encing the greatest demographic

are nearing the end of life. shift in U.S. history. According

to current projections, by 2030,

Policies and payment systems 20% of Americans will be more

Federal, state, and private insurance and health care delivery pro- than 65 years old. Cultural diver-

grams should integrate the financing of medical and social services sity is also increasing, as is the

to support the provision of high-quality care consistent with patients’ percentage of people with one or

values, goals, and informed preferences. Insofar as additional legis- more chronic illnesses. It is there-

lation is necessary to implement this recommendation, the admin- fore imperative that the medical

istration should seek and Congress should enact such legislation. The community listen to patients and

federal government should require public reporting on quality mea- recognize that their end-of-life

sures, outcomes, and costs and encourage private payers and deliv-

preferences may change over time,

ery systems to do the same.

especially as longevity increases.

Public education and engagement The goal should be to help peo-

Civic leaders, public health and other governmental agencies, com- ple receive care in keeping with

munity-based organizations, faith-based organizations, con sumer their personal preferences as they

groups, health care delivery organizations, payers, employers, and pro- near the end of life.

fessional societies should engage their constituents and provide fact- In Dying in America: Improving

based information to encourage advance care planning and informed Quality and Honoring Individual

choice based on individuals’ needs and values. Preferences near the End of Life, an

Institute of Medicine (IOM) com-

* The full report is available at www.iom.edu/endoflife.

mittee (which we cochaired) con-

cluded that the U.S. health care

system is poorly designed to

of surveyed physicians, say they’d sponding to the wishes and de- meet the needs of patients and

like to die at home and avoid high- mands of patients’ families who their families at the end of life

intensity care and hospitalization. want more medical therapy than and that major changes are need-

Yet their wishes are too frequently medical providers believe is indi- ed. We need to begin by foster-

overridden by the physicians car- cated or beneficial. In a study ex- ing patients’ ability to take con-

ing for them, who undertake amining the care of more than trol of their quality of life

more medical interventions than 848,000 people who had died in throughout their life and to

patients desire. Physicians also 2000, 2005, or 2009 while cov- choose the care they desire near

sometimes find themselves re- ered by fee-for-service Medicare, the end of life.4 The committee

596 n engl j med 372;7 nejm.org february 12, 2015

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org at UNB on March 10, 2015. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2015 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

PE R S PE C T IV E Care near the End of Life

recognized that these goals organize their clinical services er’s license, get married, begin a

could be achieved only by mak- so as to provide seamless, high- new job, relocate, or become eli-

ing major changes to the educa- quality, patient- and family-cen- gible for Medicare — not just

tion, training, and practice of tric care that is consistently avail- when advanced illness or death is

health care professionals, as well able to their patients, especially imminent. Many physicians need

as changes in health care policy those who have advanced serious to learn how to conduct these

and payment systems, Simulta illness or are nearing the end of conversations respectfully and

neously, individual and public life. Even by simply providing pa- successfully. Physicians can then

education would have to be radi- tients with a consistent and ac- make their patients’ preferences

cally reformed to reshape expec- cessible place to call when they known to all members of the

tations and allow patients and need help, physicians can avert un- health care team. Physicians

clinicians to have meaningful dis- necessary trips to the emergency should be compensated for the

cussions about end-of-life plan- department or another acute care time required to have these dis-

ning (see box). setting where patients’ individual cussions — a change they can

The IOM committee concluded preferences may not be known or prod the government and other

that “federal, state, and private in- honored. Becoming more acces- payers to make.

surance and health care delivery sible in this way improves the Changing the culture in these

programs should integrate the fi- quality of care and should reduce ways will require intervention at

nancing of medical and social unnecessary utilization of expen- all stages of physicians’ education.

services to support the provision sive medical treatments. Physician educators can develop

of quality care consistent with the Physicians can also work to new models of teaching (includ-

values, goals, and informed pref- ensure that their patients have ac- ing the use of simulation) for

erences of people with advanced cess — in all care settings — to students, residents, and fellows.

serious illness nearing the end of skilled palliative care or, when But physicians can also learn and

life.” More specifically, the com- appropriate, hospice care. We be- teach about compassionate patient

mittee recommended that insofar lieve that basic palliative care care in their practice settings

as additional legislation is required skills should be part of the knowl- and communities. They can then

to allow for such financing, rele- edge base of all physicians car- contribute to public dialogues

vant laws should be enacted (e.g., ing for people with advanced se- about end-of-life issues in their

authorization of payments for ser- rious illness or near the end of communities and religious groups

vices delivered in ambulatory or life. Physicians can also seek out — working especially to help to

home settings rather than only collaboration, whenever possible, dispel misinformation.

in inpatient settings) and that the with skilled palliative care spe- Physicians’ experiences with

federal government should “re- cialists, whether doctors, nurses, medical care and dying patients

quire public reporting on quality social workers, or clergypersons, have helped crystallize their de-

measures, outcomes, and costs to ensure the best possible care sires for their own end-of-life

regarding care near the end of of their patients. It has been experiences. As Dying in America

life . . . for programs it funds demonstrated that when pallia- makes clear, physicians should

or administers (e.g., Medicare, tive care is combined with active now practice what they profess,

Medicaid, the Department of treatment for patients with ad- to ensure that their patients have

Veterans Affairs)” and encourage vanced cancer, the quality and the same options that they them-

other U.S. payment and delivery duration of life are enhanced.5 selves, and a majority of Ameri

systems to follow suit. We believe All this care should be coordi- cans, would choose and that they

that physicians can and should nated, and handoffs should be honor patients’ preferences at the

work with their professional or- avoided at critical junctures for end of life.

ganizations to advocate for these patients, such as when they first Disclosure forms provided by the authors

changes — but rather than wait- encounter a chronic illness or a are available with the full text of this article

at NEJM.org.

ing for new legislation, they can life-threatening disease.

take action now, in part by set- Ideally, physicians would initi- Dr. Pizzo is a professor of pediatrics and of

ting aside time to encourage pa- ate discussions about advance di- microbiology and immunology and former

tients to express their preferenc- rectives with their patients at key dean at Stanford University School of Medi-

cine, Stanford, CA; and Mr. Walker is a for-

es regarding end-of-life care. milestones throughout their lives mer comptroller general of the United

Physician practices can also — perhaps when they get a driv- States.

n engl j med 372;7 nejm.org february 12, 2015 597

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org at UNB on March 10, 2015. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2015 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

PERS PE C T IV E Care near the End of Life

1. Gallo JJ, Straton JB, Klag MJ, et al. Life- 3. Teno JM, Gozalo PL, Bynum JPW, et al. 5. Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, et al.

sustaining treatments: what do physicians Change in end-of-life care for Medicare ben- American Society of Clinical Oncology pro

want and do they express their wishes to eficiaries: site of death, place of care, and visional clinical opinion: the integration of

others? J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:961-9. health care transitions in 2000, 2005, and palliative care into standard oncology care.

2. Periyakoil VS, Neri E, Fong A, Kraemer H. 2009. JAMA 2013;309:470-7. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:880-7.

Do unto others: doctors’ personal end-of-life 4. Institute of Medicine. Dying in America:

resuscitation preferences and their attitudes improving quality and honoring individual DOI: 10.1056/NEJMp1413167

toward advance directives. PLoS One 2014; preferences near the end of life. Washington, Copyright © 2015 Massachusetts Medical Society.

9(5):e98246. DC: National Academies Press, 2014.

Finding the Right Words at the Right Time — High-Value

Advance Care Planning

Justin Sanders, M.D.

Related article, p. 595

W hen Ms. C. died, I was sad

but not surprised. I had

met her 4 years earlier, when I

I remember when Ms. C.’s car-

diologist, who was as close to

her as I was, told me he was con-

among other strategies, better

advance care planning (ACP).1

Specifically, it recommends the

was an intern and she was the cerned that she might not live development of “standards for

first patient who identified me another year: her arrhythmia had clinician–patient communication

as “my doctor.” She did so en- become more difficult to control. and advance care planning that

thusiastically, asking the inpatient She had no advance directive. He are measurable, actionable, and

medical teams who frequently suggested that I speak with her evidence based” and that these

cared for her to run every deci- about it, and I said I’d try to find standards be tied by payers and

sion by me. As a trainee, and a good time. I never did. professional societies to “reim-

given her complex needs, I found Some months later, as a newly bursement, licensing, and creden-

those requests both absurd and appointed attending, I returned tialing” (see Perspective article by

overwhelming. By 65 years of age, from a vacation to an e-mail in- Pizzo and Walker, pages 595–598).

Ms. C., a lifelong smoker, had forming me of Ms. C.’s death. She If promoting ACP discussions

coronary artery disease, atrial had died in the intensive care unit were as simple as asking or pay-

fibrillation, diabetes, and chron- after an unsuccessful attempt at ing physicians to have them, Dy-

ic obstructive pulmonary disease cardiopulmonary resuscitation. I’m ing in America might not have been

(COPD) complicated by pulmo- pretty sure that’s not what she necessary. These discussions are

nary hypertension. During the would have wanted, but I couldn’t difficult, and for multiple reasons:

time I knew her, she was hospi- say for certain. I stared at my perceived difficulty of prognosti-

talized at least every 3 months computer screen, feeling the lead- cation, uncertainty about how

for complications of one or an- en weight of a missed opportu- best to communicate with pa-

other of her chronic conditions. nity and a sense of profound dis- tients and families with diverse

The only thing she hated more appointment in myself. I felt that communication needs, and inad-

than the hospital was the panic I had failed one of my first and equate time to have them — not

induced by uncontrolled dyspnea, favorite patients. to mention the troubling emo-

chest pain, or palpitations — Since becoming a palliative tions that talk of death raises for

the panic that led her to dial care doctor some years later, I’ve both patients and physicians.2

911. When she came into the thought many times about Ms. C. During our medical education,

clinic for follow-up, she’d tell and the consequences of my own discussions of end-of-life care re-

me that she never wanted to go and others’ inaction. And these ceive minimal, if any, attention.

back. I would check to make sure missed opportunities have become In response to deficiencies in

she understood her medication a topic of national conversation. physician communication about

changes. She would ask about Last September, the Institute of end-of-life care preferences, policy-

my family. I would plead with Medicine (IOM) released a report makers, patient advocates, and

her to quit smoking. A gregarious entitled Dying in America, in which payers have endeavored to move

Latina, she always shouted “I love it recommends measures to im- ACP out of physicians’ hands,

you” as I walked out of the room. prove end-of-life care through, from the clinic to the telephone

598 n engl j med 372;7 nejm.org february 12, 2015

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org at UNB on March 10, 2015. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2015 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (589)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (842)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5806)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- International College of Applied Kinesiology USA (PDFDrive)Document241 pagesInternational College of Applied Kinesiology USA (PDFDrive)dvenumohan100% (4)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Understanding: Body Dysmorphic DisorderDocument14 pagesUnderstanding: Body Dysmorphic DisordervivienNo ratings yet

- DC - M. Youssry Final WhiteDocument21 pagesDC - M. Youssry Final Whitemarwa abdelmegedNo ratings yet

- Veterinary Cytology by Leslie C. Sharkey, M. Judith Radin, Davis SeeligDocument994 pagesVeterinary Cytology by Leslie C. Sharkey, M. Judith Radin, Davis SeeligBê LagoNo ratings yet

- Otitis & Ear Mites ProtocolDocument5 pagesOtitis & Ear Mites ProtocolBê LagoNo ratings yet

- ACVIM Consensus Statement On The Diagnosis and TreatmentDocument28 pagesACVIM Consensus Statement On The Diagnosis and TreatmentBê LagoNo ratings yet

- Common Abbreviations in Vet MedDocument5 pagesCommon Abbreviations in Vet MedBê LagoNo ratings yet

- Blocked CatDocument9 pagesBlocked CatBê LagoNo ratings yet

- 2015 - Mounsey - Management of Constipation in Older AdultsDocument6 pages2015 - Mounsey - Management of Constipation in Older AdultsBê LagoNo ratings yet

- 2015 - Locke - Diagnosis and Management of Generalized Anxiety and PanicDocument9 pages2015 - Locke - Diagnosis and Management of Generalized Anxiety and PanicBê LagoNo ratings yet

- 1999 MullenDocument6 pages1999 MullenElisaMiNo ratings yet

- Lakshmi Sahgal Class 7 LibraryDocument2 pagesLakshmi Sahgal Class 7 Library7A04Aditya MayankNo ratings yet

- UpdatedThe Third LevelDocument24 pagesUpdatedThe Third Levelmysterious girlNo ratings yet

- ARNISDocument19 pagesARNISJulien KwonNo ratings yet

- NSSBCHM Activity 16 LabDocument4 pagesNSSBCHM Activity 16 Labsad asdNo ratings yet

- Organisational Behaviour Assignment - Job Satisfaction - PDFDocument17 pagesOrganisational Behaviour Assignment - Job Satisfaction - PDFMuna Hussien OsmanNo ratings yet

- Family Nursing Care PlanDocument11 pagesFamily Nursing Care PlanBrenden Justin NarcisoNo ratings yet

- Nexgard For Dogs and Puppies Free 2 Day ShippingDocument1 pageNexgard For Dogs and Puppies Free 2 Day Shippinglyly23748No ratings yet

- Care Skills Level 5Document4 pagesCare Skills Level 5anitadavid40No ratings yet

- Literature Review On Drug AddictionDocument8 pagesLiterature Review On Drug Addictionaflsodqew100% (1)

- I-Byte Healthcare July 2021Document89 pagesI-Byte Healthcare July 2021IT ShadesNo ratings yet

- Lmce1072 Academic Literacy ASSESSMENT 1 (40%) Text Dissect Content Organiser (Tedco) SEMESTER 2, 2020-2021Document4 pagesLmce1072 Academic Literacy ASSESSMENT 1 (40%) Text Dissect Content Organiser (Tedco) SEMESTER 2, 2020-2021Luqman HakemNo ratings yet

- Academic Calendar 2012-2013 MITDocument6 pagesAcademic Calendar 2012-2013 MITnhartono_1No ratings yet

- I. Find ONE Word To Complete The Following Sentences Exercise 1Document2 pagesI. Find ONE Word To Complete The Following Sentences Exercise 1Nguyễn HằngNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Nursing 6th Class 2078Document67 pagesPediatric Nursing 6th Class 2078Poonam RanaNo ratings yet

- Lecture 06 (Corrosive - Organic Acids) 2Document45 pagesLecture 06 (Corrosive - Organic Acids) 2saraNo ratings yet

- COVID Testing Labs 31052021Document176 pagesCOVID Testing Labs 31052021SangiliNo ratings yet

- Charles BabbageDocument3 pagesCharles BabbageElgen B. AgravanteNo ratings yet

- Clinical Practice Experience (CPE) RecordDocument9 pagesClinical Practice Experience (CPE) RecordSammy ChegeNo ratings yet

- 000 00 Qa FRM 0108Document2 pages000 00 Qa FRM 0108vijay rajNo ratings yet

- Minerals Sports Club June Fitness ScheduleDocument2 pagesMinerals Sports Club June Fitness ScheduleMineralsSportsClubNo ratings yet

- Stryker Prime Stretcher 1115 Hospital Bed - User ManualDocument93 pagesStryker Prime Stretcher 1115 Hospital Bed - User ManualBiancaNo ratings yet

- Ultrasound System: Acoustic Output TablesDocument108 pagesUltrasound System: Acoustic Output TablesFoued MbarkiNo ratings yet

- Management Hypovolemic Shock, NurinDocument12 pagesManagement Hypovolemic Shock, Nurinرفاعي آكرمNo ratings yet

- Material Safety Data Sheet: Manufacturer Pt. Bital AsiaDocument3 pagesMaterial Safety Data Sheet: Manufacturer Pt. Bital Asiaedi100% (1)

- PHLEBOTOMYDocument21 pagesPHLEBOTOMYmyka brilliant cristobalNo ratings yet

- 2020 State of Digital Accessibility Report Level AccessDocument40 pages2020 State of Digital Accessibility Report Level AccessSangram SabatNo ratings yet