Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Post-Capitalist Interregnum: The Old System Is Dying, But A New Social Order Cannot Yet Be Born

Uploaded by

ShelscastOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Post-Capitalist Interregnum: The Old System Is Dying, But A New Social Order Cannot Yet Be Born

Uploaded by

ShelscastCopyright:

Available Formats

FEATURE 68

The post-capitalist interregnum

The old system is dying, but a new social order

cannot yet be born

A ‘post-capitalist interregnum’ is dawning, argues Wolfgang Streeck – a prolonged period

of social entropy, radical uncertainty and indeterminacy, in which society is essentially

ungovernable and no new world order waits in the wings. Tracing the four-stage crisis

sequence of neoliberal capitalism up to today’s disintegrating state system, he finds it

exemplified in borderless Europe – and specifically in Britain’s fateful referenda.

Capitalism was always a fragile and improbable order that depended on

continuous repair work for its survival.1 Today, however, too many of its

frailties have become acute simultaneously, while too many remedies to

them have been exhausted or destroyed. Rather than picking one of the

various manifestations of the crisis and privileging it over others, I suggest

that all – or most – of them may add up to a condition of multi-morbidity,

in which different disorders coexist and, more often than not, reinforce each

other. The end of capitalism may, then, occur as a death from a thousand

cuts – from multiple infirmities, each of which will become all the more

untreatable as all will demand treatment at the same time.

In other words, I do not believe that any of the potentially stabilising forces

frequently mentioned – be it regime pluralism, regional diversity and uneven

development, political reform, independent crisis cycles or whatever2 – will

be strong enough to neutralise the syndrome of accumulated weaknesses

that characterises contemporary capitalism as a social order. No effective

opposition being left, and no successor waiting in the wings of history,

capitalism’s accumulation of defects – paralleling its accumulation of capital

– amounts to an entirely endogenous dynamic of self-destruction, one that

follows an evolutionary logic that is moulded by contingent cirumstances

and coincidental events but cannot be suspended by them, along a

historical trajectory from early liberal capitalism, via state-administered

capitalism, to neoliberal capitalism, which for the time being culminated

in the financial crisis of 2008.

Towards social entropy

For the decline of capitalism to continue, I suggest, no revolutionary

alternative is required, and certainly no masterplan of a better society

that will displace or replace capitalism. Contemporary capitalism as

1 This article draws in part on the introductory chapter of my forthcoming book, How Will Capitalism End?

Essays on a Failing System, to be published by Verso in November 2016.

2 Wallerstein I, Collins R, Mann M, Derluguian G and Calhoun C (2013) Does Capitalism Have a Future?,

Oxford University Press.

Juncture \ Volume 23 \ ISSUE 2 © 2016 The Author/s. Juncture © 2016 IPPR

J23-2_text_160901.indd 68 01/09/2016 19:02:50

FEATURE 69

a functioning social order is vanishing on its own account, collapsing “Contemporary

from internal contradictions – not least as a result of having vanquished

capitalism as a

its enemies, who have often rescued capitalism from itself by forcing

it to evolve into a new form. What will follow on from capitalism next functioning social

will, I submit, not be socialism or some other defined social order, order is vanishing

but a long interregnum3 – no new world system equilibrium, but on its own

rather a prolonged period of social entropy; of radical uncertainty4 account, collapsing

and indeterminacy. It is an interesting problem for sociological theory

whether and (if so) how a society can turn for a significant length of time

from internal

into less than a society – a post-social society, or a society lite – until it contradictions

may or may not recover to again become a society in the full meaning – not least as a

of the term. I believe that one can get a conceptual handle on this by result of having

drawing liberally on the distinction, introduced by David Lockwood vanquished its

back in 1964, between system integration and social integration, or

integration at the macro and micro levels.5 An ‘interregnum’ would then

enemies.”

be defined as a breakdown of macro-level system integration, depriving

individuals at the micro-level of institutional structuring and collective

support and shifting the burden of ordering social life, of providing it

with a modicum of security and stability, to individual actors and such

social arrangements as they can improvise on their own. A society in

interregnum, in other words, would be a de-institutionalised or under-

institutionalised society, one in which expectations can be stabilised

only now and then by local extemporisation, and which for this very

reason is essentially ungovernable.

A post-capitalist society would, then, appear to be one whose

system integration is critically and irremediably weakened, so that the

continuation of capital accumulation – for a final, intermediate period

of uncertain duration – becomes dependent on the opportunism of

collectively incapacitated individualised individuals, struggling to protect

themselves from risk in their social and economic lives. Undergoverned

and undermanaged, the social world of the post-capitalist interregnum

– in the wake of neoliberal capitalism’s neutralisation of states,

governments, borders, trade unions and other moderating forces – can

at any time be hit by disaster: bubbles may implode, for example, or

violence penetrate from a collapsing periphery into the centre. With

individuals deprived of collective defences and left to their own devices,

what remains of a social order hinges on their motivation to co-operate

ad hoc with other individuals, driven by elementary interests in individual

survival and, often enough, fear and greed. As society loses its ability to

provide its members with effective protection and proven templates of

social action and social existence, individuals have only themselves to

rely on while social order must depend on the weakest possible mode of

social integration – Zweckrationalität (or ‘instrumental rationality’).

3 I take this concept from Antonio Gramsci’s Prison notebooks, in which he speaks of an era in which ‘the

old is dying but the new cannot yet be born’, ushering in ‘an interregnum in which sinister phenomena of

the most diverse sort come into existence’. See Gramsci A (1971) Selections from the Prison Notebooks of

Antonio Gramsci, edited and translated by Hoare Q and Nowell-Smith G, Lawrence & Wishart Ltd.

4 King M (2016) The End of Alchemy: Money, Banking and the Future of the Global Economy, Little, Brown.

5 Lockwood D (1964) ‘Social Integration and System Integration’, in Zollschan G K and Hirsch W (eds)

Explorations in Social Change, Houghton Mifflin: 244–257.

© 2016 The Author/s. Juncture © 2016 IPPR Juncture \ Volume 23 \ ISSUE 2

J23-2_text_160901.indd 69 01/09/2016 19:02:50

FEATURE 70

As explained elsewhere,6 I anchor this condition in a variety of interrelated

developments, including the intensification of distributional conflict as

a result of declining growth; the rising inequality that results from this;

vanishing macroeconomic manageability, as manifested in, among other

things, steadily growing indebtedness, a pumped-up money supply, and

the possibility of another economic breakdown at any time; the suspension

of postwar capitalism’s engine of social progress, democracy, and the

associated rise of oligarchy; the dwindling capacity of governments and

the systemic inability of governance to limit the commodification of labour,

nature and money; the omnipresence of corruption of all sorts, in response

to intensified competition in winner-take-all markets with virtually unlimited

opportunities for self-enrichment; the erosion of public infrastructures and

collective benefits in the course of commodification and privatisation;

the failure, after 1989, of capitalism’s carrier nation, the US, to build and

maintain a stable global order; and so on and so on. These and other

developments, I suggest, have resulted in widespread cynicism regarding “A number of

political and economic life, forever ruling out a recovery of normative

developments

legitimacy for capitalism as a just society that offers equal opportunities

for individual progress – a legitimacy that capitalism needs to draw on in have resulted

critical moments. in widespread

cynicism regarding

Moving disequilibrium political and

In recent work I have argued that OECD capitalism has been on a crisis economic life,

trajectory since the 1970s, the historical turning point being the abandonment forever ruling

of the postwar settlement by capital in response to a global profit squeeze.

Subsequently, three crises followed one another: the global inflation of the

out a recovery

1970s, the explosion of public debt in the 1980s, and rapidly rising private of normative

indebtedness in the subsequent decade, resulting in the collapse of financial legitimacy for

markets in 2008. This sequence was, by and large, the same for all major capitalism as a

capitalist countries, whose economies have never nearly been in equilibrium just society.”

since the end of postwar growth. All three crises began and ended in the

same way, following the same political-economic logic: inflation, public

debt and the deregulation of private debt started out as politically expedient

solutions to distributional conflicts between capital and labour (and, in the

1970s, between the two and the producers of raw material whose cost had

long been negligible), until they became problems themselves. Inflation begot

unemployment as relative prices became distorted and owners of monetary

assets abstained from investment; mounting public debt made creditors

nervous and produced pressures for fiscal consolidation in the 1990s; and

the pyramid of private debt that had filled the gaps in aggregate demand and

citizen satisfaction caused by cuts in public spending imploded when the

bubbles produced by easy money burst.

Solutions thus turned into problems requiring new solutions which,

after another decade or so, became problems themselves – which then

called for yet other solutions that soon turned out to be as short-lived

and self-defeating as their predecessors. Government policies vacillated

between two equilibrium points, one political, the other economic, that

6 Streeck W (2014) ‘How Will Capitalism End?’, New Left Review 87: 35–64.

Juncture \ Volume 23 \ ISSUE 2 © 2016 The Author/s. Juncture © 2016 IPPR

J23-2_text_160901.indd 70 01/09/2016 19:02:50

FEATURE 71

had become impossible to attain simultaneously. Attending to the need

for democratic political legitimacy and social peace, so as to live up to

citizen expectations of economic prosperity and social stability, they

found themselves at risk of damaging economic performance. Conversely,

efforts to restore the economy to equilibrium tended to trigger political

dissatisfaction and undermine support for the government of the day, and

for the liberal-capitalist market economy in general.

Actually the situation was even more critical than that, although it was

not perceived as such for a long time as it unfolded only gradually,

spread out over two or three political generations. Intertwined with the

crisis sequence of the 1970s onwards was an evolving fiscal crisis of the

democratic-capitalist state, again basically in all countries undergoing the

secular transition from state-administered ‘late’ capitalism to neoliberal

capitalism. While in the 1970s governments still had a choice, within limits,

between inflation and public debt as means of bridging the gap between

the combined claims of capital and labour and the resources available

for distribution, after the end of inflation at the beginning of the 1980s the

‘tax state’ of postwar capitalism began to change into a ‘debt state’. In

this it was helped by the growth of a dynamic, increasingly global financial

industry based in the de-industrialising headquarter country of global

capitalism, the US. Concerned about the capacity of its new clients –

who were, after all, sovereign states – to unilaterally cancel their debt, an

increasingly powerful financial sector soon began to seek reassurance from

governments on their economic and political ability to service and repay

their loans. The result was another transformation of the democratic state,

this time into what I have called a ‘consolidation state’, which began in

the mid-1990s. To the extent that consolidation of public finances through

spending cuts resulted in overall gaps in demand or in popular discontent,

the financial industry was happy to step in with loans to private households,

provided that credit markets were sufficiently deregulated. “Since 2008, we

Since 2008, we have been living in a fourth stage of the post-1970s crisis have been living

sequence, and the by now familiar dialectic of problems treated with in a fourth stage

solutions that themselves turn into problems is again making itself felt. The

three apocalyptic horsemen of contemporary capitalism – stagnation, debt

of the post-1970s

and inequality – are continuing to devastate the economic and political crisis sequence,

landscape. With ever-lower growth, as recovery from the Great Recession and the by now

made little or no progress, deleveraging had to be postponed ad calendas familiar dialectic

graecas, and overall indebtedness is higher than ever.7 As part of a total debt

burden of unprecedented magnitude, public debt has jumped up again, not

of problems

only annihilating all gains made in the first phase of consolidation but also treated with

effectively blocking any fiscal effort to restart growth. Thus unemployment solutions that

remains high throughout the OECD world, even in a country like Sweden themselves turn

where full employment had for decades been a cornerstone of national into problems

identity. Where employment has been restored it has tended to be at lower

pay and inferior conditions, due to technological change, ‘reforms’ in social

is again making

security systems that lower workers’ reservation wage, and de-unionisation itself felt.”

7 Dobbs R, Lund S, Woetzel J and Mutafchieva M (2015) Debt and (not much) deleveraging, McKinsey Global

Institute, McKinsey & Company.

© 2016 The Author/s. Juncture © 2016 IPPR Juncture \ Volume 23 \ ISSUE 2

J23-2_text_160901.indd 71 01/09/2016 19:02:50

FEATURE 72

with the attendant increase in the power of employers. Indeed, ‘recovery’

often amounts to replacement of unemployment with underemployment.

Although interest rates are at a record low, investment and growth refuse

to respond, giving rise to discussions among policymakers about lowering

them further, to below zero. While in the 1970s inflation was public enemy

number one, now desperate efforts are being made throughout the OECD

world to bring it up to at least 2 per cent, thus far without success. Whereas

in the past it was the coincidence of inflation and unemployment that left

economists clueless, now it is very cheap money coinciding with deflationary

pressures, raising the spectre of ‘debt deflation’ and the collapse of a

pyramid of accumulated debt that far exceeds that of 2008.

Foremost among the signature characteristics of the current, fourth phase

of the post-1970s crisis sequence is the rise of the central banks to

supreme economic policymaking power – central banks that have, in the

course of the liberalisation process, been made independent from national

governments by national governments, consequently making them all the

more dependent on their other partner, the private banking industry. Since

the Great Recession, the same central banks that had been responsible

for the easy money policies that had produced the bubble have been

keeping the global economy alive by injecting a continuous stream of cash,

created out of thin air, into the international banking system. How long they

will continue to do so, and on what conditions, is considered a technical

question beyond the competence of governments and electorates. This

also applies to the question of which commercial and government bonds

central banks should buy in order to bring new money into circulation – a

practice that has no less than tripled the balance sheets of the leading

central banks since 2007. Unlike governments, central banks deliberate and

make decisions in full secrecy, out of the public view, with the full support

of governments which, given the proven uselessness of their own policy

instruments and their complete lack of ideas on how to bring back growth

and stability, depend vitally on being able to delegate responsibility for

economic policy to supposedly non-political actors and institutions.

The Interregnum

Why, if capitalism is on its way out, is there no non-capitalism ready to “Why, if capitalism

succeed it? A social order breaks down if and when its elites are no longer

is on its way out,

able to maintain it; but for it to be cleared away, there has to be a new

vanguard able to design and eager to install a new order. Obviously the is there no

incumbent management of advanced and not-so-advanced capitalism is non-capitalism

uniquely clueless. Consider the senseless production of money to stimulate ready to

growth in the real economy; the desperate attempts to restore inflation with succeed it?”

the help of negative interest rates; and the apparently inexorable coming

apart of the modern state system on its periphery. Concerning the latter,

systemic entropy originates in the weakening position of the US as the host

nation of global capitalist expansion. Historically, capitalism always advanced

on the coattails of a strong, hegemonic state opening up and preparing new

landscapes for capital accumulation, through military force or free trade, and

indeed typically through both. Political preparation for capitalist development

included not just the breaking-up of pre- or anti-capitalist social orders, but

Juncture \ Volume 23 \ ISSUE 2 © 2016 The Author/s. Juncture © 2016 IPPR

J23-2_text_160901.indd 72 01/09/2016 19:02:50

FEATURE 73

also the creation of new, ‘modern’ societies supportive of private capital

accumulation. After 1945, this meant the establishment of a global system of

secular states with a ‘development’ agenda, sovereign but integrated in an

international free trade regime. Also on the agenda was the containment and,

if necessary and possible, suppression of alternative, oppositional systems –

a program that at first glance came to its victorious completion in 1989.

This, however, was not the whole story. As it turned out, the US, while still

able to destroy its enemies, had lost the capacity to replace them with

stable pro-American and pro-capitalist regimes – losing its constructive

powers while retaining its destructive ones. The causes of this include the

demonstration effect of the defeats suffered by the US in successive wars,

as well as declining domestic support for what a majority of US citizens

now consider foreign ‘adventures’. ‘Nation-building’ having failed in large

parts of the world, the global system of semi-sovereign, development-

friendly free-trade states as originally envisaged shows growing holes

and gaps, with failed states as a permanent source of unpredictable and

increasingly unmanageable political and economic disorder. In many

regions, fundamentalist religious movements have taken control, rejecting

international law and modernism in general, and seeking an alternative to

the capitalist consumerism which they can no longer expect to replicate in

their countries. Others, having abandoned hope for ‘development’ at home,

are trying to join advanced capitalism by migrating from the periphery to the

center. There they meet with second-generation immigrants who have given

up on ever being fully admitted to the capitalist-consumerist mainstream of

their societies. One result of this is another migration – the migration of the

violence that is destroying the stateless societies of the periphery into the

metropolis, in the form of ‘terrorism’ wrought by a new class of ‘primitive

rebels’ that lacks any vision of a practically possible progressive future, of

a renewed industrial or new post-industrial society both developing further

than and overcoming the capitalist society of today.

Not just capital and its running dogs, but also their opponents, today lack

a capacity to act collectively. Just as capitalism’s movers and shakers do

not know how to protect their society from decay, and in any case would “The historical

lack the means to do so, their enemies, when it comes to the crunch, have period after the

to admit that they have no idea of how to escape neoliberal capitalism. See

for example the Greek government and its capitulation in 2015, when the

death of capitalist

‘Eurogroup’ began to play hardball and Syriza (to use a different metaphor) society from

had to show its hand. an overdose of

The historical period after the death of capitalist society from an overdose capitalism will

of capitalism will be one lacking collective political capacities, making for a be one lacking

long and indecisive transition – a time of crisis as the new normal, a crisis collective political

that is neither transformative nor adaptive, and unable to either restore capacities, making

capitalism to equilibrium or replace it with something better. Deep changes

will occur, rapidly and continuously, but they will be unpredictable and in

for a time of crisis

any case ungovernable. Western capitalism will decay, but non-Western as the new normal.”

capitalism will not take its place, certainly not on a global scale; and neither

will Western non-capitalism.

© 2016 The Author/s. Juncture © 2016 IPPR Juncture \ Volume 23 \ ISSUE 2

J23-2_text_160901.indd 73 01/09/2016 19:02:50

FEATURE 74

With regards to non-Western capitalism, China will for many reasons not be

able to take over as capitalism’s carrier nation and provide an orderly global

environment for its further progress. Nor will there be a co-directorate of

China and the US, amicably dividing between them the task of making the

world safe for capitalism. And concerning non-capitalism, there is no such

thing today as a global socialist movement comparable to the socialisms

of the 19th and early 20th centuries, which so successfully confronted and

transformed capitalism in national power struggles. As long as capitalist “As long as capitalist

dynamism continues to outrun collective order-making and the development

dynamism

of non-market institutions, as it has for several decades now, it disempowers

both capitalism’s government and its opposition, resulting in capitalism being continues to

neither reborn nor replaced. outrun collective

order-making and

The state system in disarray the development

The social disorder of the emerging interregnum makes itself felt of non-market

at the macro level in a wide variety of dysfunctions of states and institutions it

governments. In one way or another, they are all related to the politically

willed obsolescence of national borders in a global economy, and the

disempowers

contests that arise over it. Border contests raise basic issues concerning both capitalism’s

the relationship between nationalism and cosmopolitanism, national government and

government and global governance, and particularism and universalism, its opposition.”

in ever-new configurations and permutations. Generally, in an era of

‘globalization’, governments are coming under pressure to open up their

countries, rendering national state borders economically and politically

irrelevant. As a consequence they must commit to policies of structural

‘adjustment’ in order to make their societies ready for global competition,

by cutting back on protective social policies in favor of ‘enabling’ ones,

while increasingly allowing their citizens to be exposed to the vagaries of

international markets.

Redefining borders in line with the demands of globalisation and in pursuit

of liberalisation invalidates national democratic institutions as channels

for transmitting popular demands for social protection against market

pressures. For a while this resulted in electorates – and particularly

voters at the lower end of the income distribution – losing interest in

democratic politics. As restructuring pressures increased, however, voters

negatively affected by liberalisation and globalisation rediscovered political

participation as a means of expressing protest. The resulting increase in

electoral turnout benefits new ‘populist’ parties, mostly on the right but

sometimes also on the left. Their common denominator is a radical rejection

of established political elites, combined with insistence that national

democracy must supersede the demands of international markets.

Ideologically, the ensuing conflict is complicated by the fact that free-

market liberals have found it convenient to appropriate the internationalism

of the progressive left as a rhetorical tool with which to discredit social

protection and the institutions associated with it – particularly national

democracy and the national welfare state. As a result, their defenders run

the risk of being accused of nationalism or xenophobia, and indeed racism.

The way the discourse over globalisation and democracy is unfolding,

Juncture \ Volume 23 \ ISSUE 2 © 2016 The Author/s. Juncture © 2016 IPPR

J23-2_text_160901.indd 74 01/09/2016 19:02:50

FEATURE 75

it is driving a wedge into the constituency of left-liberal political parties, “Those hoping to

between their new middle-class supporters who profess to internationalism

in the name of universal solidarity, and their traditional working-class voters

benefit from lower

whose experience tends to be that open borders undermine their jobs and prices and better

ways of life. The issue is particularly relevant when it comes to immigration quality may be

and the possibility it raises for developed national economies to attract tempted to deploy

an unlimited supply of labour, without having to improve the conditions in a universalistic

which families raise children. Here, conflicts over economic interests may

become particularly acute and emotionally and ideologically charged, as

rhetoric of

those hoping to benefit from lower prices and better quality – for example, international

in the provision of services – may be tempted to deploy a universalistic solidarity in order

rhetoric of international solidarity in order to silence those who feel to silence those

threatened by low-wage competition.

who feel threatened

Returning to the architecture of the contemporary state system and its by low-wage

growing dysfunctionality, all attempts to move redistributive government

competition.”

and the protective national welfare state to the international level have

failed – even in Europe, where such attempts were more consciously

made than elsewhere. In the course of the 1980s, at the latest, the

social democratic project to turn the then European Community into

a transnational welfare state was aborted, its most effective opponent

being the British government under Margaret Thatcher. Subsequently,

‘Europe’ became a liberalisation machine for its associated national

political economies, with particular emphasis on social policy cutbacks,

the privatisation of public services, and fiscal consolidation. Today,

European integration is essentially about curtailing corrective state

intervention into the capitalist market economy and extending the so-

called ‘four freedoms’ of the internal market, including the free movement

of labour, conceived as a quasi-constitutional right of citizens of all

member states.

The British case

Freedom of movement became a prominent issue with the eastern

accession in 2004. It was, unsurprisingly, Britain (this time under New

Labour) that made the most extensive use of the liberalisation of European

labour markets, by waiving the waiting period allowed under the treaties

and immediately opening its national economy to eastern European labour.

(Germany under Schröder, by contrast, chose a waiting period of seven

years.) Clearly the intention was to improve the labour supply in Britain

both quantitatively and qualitatively, to compensate for domestic skill

deficits while keeping wages low. It appears that the move added roughly

750,000 Polish workers and several hundred thousand other eastern

Europeans to the British labour force in a short time.

In subsequent years, strong moral pressures from an all-party pro-

immigration ‘grand coalition’ notwithstanding, dissatisfaction with labour

market internationalism and EU immigration rules seems to have grown

in Britain, frustrating all attempts to establish legitimacy for a borderless

cosmopolitan (that is, non-protective) nation state. A powerful expression

of this dissatisfaction was the rise of the UK Independence Party (Ukip),

© 2016 The Author/s. Juncture © 2016 IPPR Juncture \ Volume 23 \ ISSUE 2

J23-2_text_160901.indd 75 01/09/2016 19:02:50

FEATURE 76

which articulated the rising popular discontent through a call for Britain to

leave the EU that reflected an apparently widespread feeling that the country

should ‘take back control’ over its borders. ‘Taking back control’ promised

a restoration of democratic accountability that many, including many on the

liberal left, felt had been lost to Brussels’ summit diplomacy and technocracy.

With hindsight it seems that the idea that Britain should again be free to

make its own laws was given added momentum by the spectacle of the

treatment of Greece as a member of the European monetary union, and also

by the claim of the German government in 2015 that its peculiar, domestically

motivated interpretation of European and international law on refugees and

asylum seekers had to be binding for Europe as a whole, including Britain.

Politics makes strange bedfellows, particularly in times of systemic

disintegration and radical uncertainty. The story of Brexit may be taken to

illustrate the bizarreries of the perverse political power plays that become

possible when an old social order is dying without a new one waiting to

take over. To the outside observer, it appears that popular anti-European

pressure must at some point have become so strong that David Cameron’s

wing of the Conservative party felt a need to once and for all re-establish

the legitimacy of open-borders liberalism. The way this was to be done was

by calling a referendum on Britain’s membership of the EU, which Cameron

was confident he would win thanks to a package of superficial concessions

on the free movement of labour that would be provided by Brussels. No

thought was given to what would happen if the vote was lost, because it was

firmly expected to be won. That the same Conservative party would spawn

a movement to leave the EU must have come as a surprise, especially since

Leavers and Remainers shared the same neoliberal economic philosophy.

Probably the prospect of carving up the Labour party right down the middle

by luring its working-class supporters into the Conservative camp while also

finishing off Ukip – thereby establishing ever-lasting electoral hegemony for

the Conservatives – was too tempting. Here, no thought was given to what

was to be done if the referendum was won, perhaps because the strategic

goal of the Leave camp within the Conservative party would have been

achieved even if the vote was narrowly lost.8

The politics of Brexit, national idiosyncrasies notwithstanding, are

informed (or misinformed) by a deep general crisis in the contemporary

state system that is in turn related to the decline of the capitalist social

order. This is already evident from the fact that the referendum on British

membership of the EU was preceded by a referendum on Scottish

membership of the UK. Like national sovereigntism, regional separatism

reflects declining confidence in a (self-)disempowered national state that

has given up its capacity to protect its citizens from market forces in

deference to international liberalisation. (That Scottish separatists seem

to intend to subject themselves, upon achieving independence, to the

very liberalisation engine that the UK has just decided to leave is another

8 The Remain revolt of old New Labour against the ‘populist’ ‘old Labour’ (led by the Remainer Corbyn)

might still result in the break-up of the Labour party. Cameron, of course, was also hoping to destroy

Labour. Where he differed from Conservative Leaver Boris Johnson was that he placed his bet on

attracting the progressive cosmopolitan middle-class Labour camp, especially since it was possible

that Corbyn himself would opt for Leave. Since Corbyn didn’t do him this favour, the Tories now

depend on Labour cutting itself up.

Juncture \ Volume 23 \ ISSUE 2 © 2016 The Author/s. Juncture © 2016 IPPR

J23-2_text_160901.indd 76 01/09/2016 19:02:50

FEATURE 77

oddity that is characteristic of a situation of radical uncertainty in which

being small may seem beautiful but is also risky.) The struggle over British

EU membership, intertwined as it is with the struggle over Scottish and,

perhaps, Welsh and Northern Irish UK membership, may be taken as

one manifestation among others of the ‘sinister phenomena of the most

diverse sort’9 that, according to Gramsci, are to be expected in an age

of interregnum: a search for political and institutional reconstruction

under conditions of structural indeterminacy, offering ample opportunity

for disoriented, arbitrary, frivolous and cynical maneuvering as the state

system of neoliberal capitalism turns dysfunctional with no cure in sight.

Ironically, the first modern state, the UK, could be also the first to

disintegrate, after having, under Thatcher, foreclosed the European rescue

of the social-democratic welfare state in the 1980s. Equally ironically, it

is Britain, which was instrumental in turning European integration into “Ironically it is

a neoliberal restructuring tool, that is now putting an end to its further

Britain, which was

progress. As the supranational order of integrated Europe is breaking down,

nobody knows how a renationalised state system is to be sustained and instrumental in

operated in a globalised political economy – note the absence of a plan B turning European

on the part of the Remainers, and of a plan A among the Leavers. How will integration into

the newly sovereign Britain of the future use its reinstated borders to ‘take a neoliberal

back control’ of its collective fate?

restructuring tool,

One cannot avoid taking note here of new prime minister Theresa May’s that is now putting

Birmingham speech of 11 July, which won her the support of her party.

May vowed to honour the outcome of the referendum and duly resign

an end to its

from the EU (an organisation, of course, that is now – for reasons of its further progress.”

own, related again to the multi-morbidity of contemporary capitalism –

so moribund that one doubts whether it will still exist in five years). But

she also interspersed her obviously carefully crafted speech with a ‘one

nation’ rhetoric not heard from a Conservative leader since the 1980s

(but heard from a Labour one rather more recently): less inequality,

controls on executive compensation, more equitable taxation, better

public education, a voice for workers in corporate governance, the

protection of British jobs from relocation abroad, and so on – all of this,

of course, combined with less immigration. This program, clearly to the

left of the Labour party in its New Labour incarnation, may have been

‘just political’ – and if not, it may soon turn out to be impractical. But it

is interesting nevertheless that it appeared when and where it did.

Wolfgang Streeck is director and professor emeritus of the

Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies, Cologne.

9 Gramsci 1971.

© 2016 The Author/s. Juncture © 2016 IPPR Juncture \ Volume 23 \ ISSUE 2

J23-2_text_160901.indd 77 01/09/2016 19:02:50

You might also like

- Rebuilding After the Fall: A Guide To Post-Apocalyptic RenaissanceFrom EverandRebuilding After the Fall: A Guide To Post-Apocalyptic RenaissanceNo ratings yet

- Summary Of "Social Aspects Of Mass Society" By William Kornhauser: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESFrom EverandSummary Of "Social Aspects Of Mass Society" By William Kornhauser: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESNo ratings yet

- Against the Dictatorship of Capital. New Philosophical, Political and Educational Lines.From EverandAgainst the Dictatorship of Capital. New Philosophical, Political and Educational Lines.No ratings yet

- Right Wing Social Revolution and Its Discontent: the Dynamics of Genocide: A Case StudyFrom EverandRight Wing Social Revolution and Its Discontent: the Dynamics of Genocide: A Case StudyNo ratings yet

- Authoritarian Collectivism and ‘Real Socialism’: Twentieth Century Trajectory, Twenty-First Century IssuesFrom EverandAuthoritarian Collectivism and ‘Real Socialism’: Twentieth Century Trajectory, Twenty-First Century IssuesNo ratings yet

- Summary Of "The Crisis Of Welfare State And Depletion Of Utopian Energies" By Jürgen Habermas: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESFrom EverandSummary Of "The Crisis Of Welfare State And Depletion Of Utopian Energies" By Jürgen Habermas: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESNo ratings yet

- Summary Of "Conceptual Fundamentals Of Political Sociology" By Robert Dowse & John Hughes: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESFrom EverandSummary Of "Conceptual Fundamentals Of Political Sociology" By Robert Dowse & John Hughes: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESNo ratings yet

- Highbeam Research: Title: Socialism in Question. Date: 3/1/1991 Publication: Monthly Review Author: Miliband, RalphDocument7 pagesHighbeam Research: Title: Socialism in Question. Date: 3/1/1991 Publication: Monthly Review Author: Miliband, RalphYazmin BaltazarNo ratings yet

- 1AR Washburn Daniel Archer ISU R1Document5 pages1AR Washburn Daniel Archer ISU R1Nadz IwkoNo ratings yet

- Mamaroneck TaMi Neg Georgetown Day School Round 1Document36 pagesMamaroneck TaMi Neg Georgetown Day School Round 1EmronNo ratings yet

- Exchanging Autonomy: Inner Motivations as Resources for Tackling the Crises of Our TimesFrom EverandExchanging Autonomy: Inner Motivations as Resources for Tackling the Crises of Our TimesNo ratings yet

- Jürgen Habermas: Selected Summaries: SELECTED SUMMARIESFrom EverandJürgen Habermas: Selected Summaries: SELECTED SUMMARIESNo ratings yet

- Richard Sennett: Selected Summaries: SELECTED SUMMARIESFrom EverandRichard Sennett: Selected Summaries: SELECTED SUMMARIESRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Conflict Theory PDFDocument6 pagesConflict Theory PDFshahid khanNo ratings yet

- Summary Of "Gramscian Dossier" By Vivana Hanono: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESFrom EverandSummary Of "Gramscian Dossier" By Vivana Hanono: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESNo ratings yet

- 27 Mouffe - Hegemony and New Political SubjectsDocument9 pages27 Mouffe - Hegemony and New Political Subjectsfmonar01No ratings yet

- Summary Of "The Political Man" By Seymour Lipset: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESFrom EverandSummary Of "The Political Man" By Seymour Lipset: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESNo ratings yet

- Summary Of "Classic Sociology: Durkheim & Weber" By Juan Carlos Pontantiero: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESFrom EverandSummary Of "Classic Sociology: Durkheim & Weber" By Juan Carlos Pontantiero: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESNo ratings yet

- Institute For Precarious Consciousness We Are All Very AnxiousDocument16 pagesInstitute For Precarious Consciousness We Are All Very AnxiousJoão EçaNo ratings yet

- Organizing for Autonomy: History, Theory, and Strategy for Collective LiberationFrom EverandOrganizing for Autonomy: History, Theory, and Strategy for Collective LiberationNo ratings yet

- BPSC 105 Block - IIDocument43 pagesBPSC 105 Block - IIavinash.kumar.876424No ratings yet

- Communists Like Us - Antonio NegriDocument90 pagesCommunists Like Us - Antonio NegriRevista EstructuraNo ratings yet

- Summary of Vaclav Havel & John Keane's The Power of the PowerlessFrom EverandSummary of Vaclav Havel & John Keane's The Power of the PowerlessNo ratings yet

- India SubalternosDocument21 pagesIndia SubalternositadelcieloNo ratings yet

- Psychosocial Analysis of the Pandemic and Its Aftermath: Hoping for a Magical UndoingFrom EverandPsychosocial Analysis of the Pandemic and Its Aftermath: Hoping for a Magical UndoingNo ratings yet

- Post COVID 19 SociologyDocument8 pagesPost COVID 19 SociologyCesar Adriano Casallas CorchueloNo ratings yet

- Micheal Velli - Manual For Revolutionary Leaders. 1972 (The Anarchist Library)Document160 pagesMicheal Velli - Manual For Revolutionary Leaders. 1972 (The Anarchist Library)Jeremy BushNo ratings yet

- Ride the Tiger: A Survival Manual for the Aristocrats of the SoulFrom EverandRide the Tiger: A Survival Manual for the Aristocrats of the SoulRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (7)

- What Can Marx Teach Us About The Restoration of Capitalism?: Rastko MočnikDocument18 pagesWhat Can Marx Teach Us About The Restoration of Capitalism?: Rastko MočnikRastkoNo ratings yet

- Manifiesto: Peligros y oportunidades de la megacrisisFrom EverandManifiesto: Peligros y oportunidades de la megacrisisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- From Equality of Opportunity To The Society of EqualsDocument13 pagesFrom Equality of Opportunity To The Society of EqualsSophia Maciel Da Rocha CaldasNo ratings yet

- Out of Control: Global Turmoil on the Eve of the 21st CenturyFrom EverandOut of Control: Global Turmoil on the Eve of the 21st CenturyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- Capitalism and Desire: The Psychic Cost of Free MarketsFrom EverandCapitalism and Desire: The Psychic Cost of Free MarketsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- The Postcolonial Contemporary: Political Imaginaries for the Global PresentFrom EverandThe Postcolonial Contemporary: Political Imaginaries for the Global PresentNo ratings yet

- Kadar EraDocument39 pagesKadar Eraanipakast100% (1)

- We Are All Very AnxiousDocument8 pagesWe Are All Very Anxiousalexpepe1234345No ratings yet

- The Capital Come Under Bourgeois Rule And Present Scenario of Political BusinessFrom EverandThe Capital Come Under Bourgeois Rule And Present Scenario of Political BusinessNo ratings yet

- Totality Inside Out: Rethinking Crisis and Conflict under CapitalFrom EverandTotality Inside Out: Rethinking Crisis and Conflict under CapitalNo ratings yet

- Beck, Ulrich & Lau, Christoph - Second Modernity As A Research Agenda (2005)Document33 pagesBeck, Ulrich & Lau, Christoph - Second Modernity As A Research Agenda (2005)Germán GiupponiNo ratings yet

- TC Suspended Step-IMPDocument14 pagesTC Suspended Step-IMPdefoemollyNo ratings yet

- Rinky-Dink Revolution: Moving Beyond Capitalism by Withholding Consent, Creative Constructions, and Creative DestructionsFrom EverandRinky-Dink Revolution: Moving Beyond Capitalism by Withholding Consent, Creative Constructions, and Creative DestructionsNo ratings yet

- The Proposed Roads to Freedom: Socialism, Anarchism & SyndicalismFrom EverandThe Proposed Roads to Freedom: Socialism, Anarchism & SyndicalismNo ratings yet

- Machover-Collective Decision-Making PDFDocument49 pagesMachover-Collective Decision-Making PDFmrendon1998No ratings yet

- Business English Pair Work 1Document177 pagesBusiness English Pair Work 1marynaylor100% (2)

- CELTA Pre Course TaskDocument33 pagesCELTA Pre Course TaskAndrésNo ratings yet

- Institutional Variation AmongDocument24 pagesInstitutional Variation AmongShelscastNo ratings yet

- EU Political Economy Enlargement Szabo 17 04 2019Document17 pagesEU Political Economy Enlargement Szabo 17 04 2019ShelscastNo ratings yet

- Dynamic Sustainabilities: Technology, Environment, Social JusticeDocument44 pagesDynamic Sustainabilities: Technology, Environment, Social JusticeShelscastNo ratings yet

- Qualitative Methods and The Study of Civil War Course SyllabusDocument6 pagesQualitative Methods and The Study of Civil War Course SyllabusShelscastNo ratings yet

- Implementing The Global Strategy Where It Matters Most The EU S Credibility Deficit and The European NeighbourhoodDocument16 pagesImplementing The Global Strategy Where It Matters Most The EU S Credibility Deficit and The European NeighbourhoodShelscastNo ratings yet

- DVD Extra: Starter Unit 1Document11 pagesDVD Extra: Starter Unit 1Daniel D'Alessandro100% (1)

- Business English Pair Work 1Document177 pagesBusiness English Pair Work 1marynaylor100% (2)

- Qualitative Methods and The Study of Civil War Course SyllabusDocument6 pagesQualitative Methods and The Study of Civil War Course SyllabusShelscastNo ratings yet

- "W" Stands For Women: Feminism and Security Rhetoric in The Post-9/11 Bush AdministrationDocument31 pages"W" Stands For Women: Feminism and Security Rhetoric in The Post-9/11 Bush AdministrationShelscastNo ratings yet

- Implementing The Concept of SuDocument15 pagesImplementing The Concept of SuShelscastNo ratings yet

- Institutional Variation AmongDocument24 pagesInstitutional Variation AmongShelscastNo ratings yet

- EU Political Economy Enlargement Szabo 17 04 2019Document17 pagesEU Political Economy Enlargement Szabo 17 04 2019ShelscastNo ratings yet

- Chords: Names and SymbolsDocument24 pagesChords: Names and SymbolsShelscastNo ratings yet

- Implementing The Global Strategy Where It Matters Most The EU S Credibility Deficit and The European NeighbourhoodDocument16 pagesImplementing The Global Strategy Where It Matters Most The EU S Credibility Deficit and The European NeighbourhoodShelscastNo ratings yet

- Co-Option or Resistance To TradeDocument15 pagesCo-Option or Resistance To TradeShelscastNo ratings yet

- Collective ActionDocument22 pagesCollective ActionShelscastNo ratings yet

- MacBook 13inch HardDrive DIYDocument8 pagesMacBook 13inch HardDrive DIYd-fbuser-15712100% (8)

- Public Evid HUKEI ISBEC 2014 PDFDocument18 pagesPublic Evid HUKEI ISBEC 2014 PDFabdul muslimNo ratings yet

- Contemporary European SecurityDocument233 pagesContemporary European SecuritycarlaNo ratings yet

- State of Nuclear Power in Europe: A ReportDocument21 pagesState of Nuclear Power in Europe: A Reportعمر نجارNo ratings yet

- July Monthly Update SlidesDocument48 pagesJuly Monthly Update SlidesBeatriz FerreiraNo ratings yet

- Eradication, Control and Monitoring Programmes To Contain Animal DiseasesDocument52 pagesEradication, Control and Monitoring Programmes To Contain Animal DiseasesMegersaNo ratings yet

- Ahvenniemi2017 Smart and Sustainable Cities PDFDocument12 pagesAhvenniemi2017 Smart and Sustainable Cities PDFaakankshaNo ratings yet

- II Bauböck 2006Document129 pagesII Bauböck 2006OmarNo ratings yet

- Paget-Advance - Advancing Knowledge To Improve Outcome in Paget's Disease of BoneDocument44 pagesPaget-Advance - Advancing Knowledge To Improve Outcome in Paget's Disease of BoneRicardo Jose GuerreroNo ratings yet

- Sample International Business Report 1Document71 pagesSample International Business Report 1Yuni DeShuong50% (2)

- Football AgentsDocument82 pagesFootball AgentsJason del Ponte100% (1)

- Malawi - ZombaDocument52 pagesMalawi - ZombaUnited Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT)100% (1)

- Connolly - The Rotten Heart of Europe The Dirty War For Europe's Money (1995) PDFDocument450 pagesConnolly - The Rotten Heart of Europe The Dirty War For Europe's Money (1995) PDFCliff100% (1)

- IEC Seminar 2 - Introduction 2 202223Document2 pagesIEC Seminar 2 - Introduction 2 202223nneoma kengoldenNo ratings yet

- OCADODocument4 pagesOCADODavid Fluky FlukyNo ratings yet

- Guide To Complete Joining FormDocument20 pagesGuide To Complete Joining FormAnto JoisenNo ratings yet

- Ana Gureanu-Barbacaru "STRENGHTENING RESILIENCE OF THE REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA TO HYBRID THREATS OF NATIONAL SECURITY"Document100 pagesAna Gureanu-Barbacaru "STRENGHTENING RESILIENCE OF THE REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA TO HYBRID THREATS OF NATIONAL SECURITY"Ana AnaNo ratings yet

- UG - Cao - .00134-004 Aircraft MaintenanceDocument39 pagesUG - Cao - .00134-004 Aircraft MaintenanceDharmendra Sumitra UpadhyayNo ratings yet

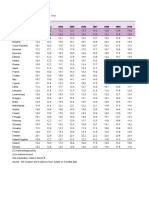

- Table 3: Indirect Taxes As % of GDP - TotalDocument20 pagesTable 3: Indirect Taxes As % of GDP - TotalAlexandra OffenbergNo ratings yet

- 024 Defining-Value-Vbhc enDocument94 pages024 Defining-Value-Vbhc enmert05No ratings yet

- Ce 2013Document80 pagesCe 2013mhldcnNo ratings yet

- Eurobarometer Standard 100 Autumn 2023 Factsheet SK enDocument4 pagesEurobarometer Standard 100 Autumn 2023 Factsheet SK enMelioris LiborNo ratings yet

- The Great EU Sugar Scam: How Europe's Sugar Regime Is Devastating Livelihoods in The Developing WorldDocument39 pagesThe Great EU Sugar Scam: How Europe's Sugar Regime Is Devastating Livelihoods in The Developing WorldOxfamNo ratings yet

- EU Tax Observatory - Annual Report - 202122Document14 pagesEU Tax Observatory - Annual Report - 202122Alexander BocaNo ratings yet

- Studies On Translation and Multilingualism: IntercomprehensionDocument60 pagesStudies On Translation and Multilingualism: IntercomprehensionNicosuuuNo ratings yet

- Directive 2004Document11 pagesDirective 2004Neena KiranNo ratings yet

- Best - in - LT - 10 OKDocument132 pagesBest - in - LT - 10 OKnavatoNo ratings yet

- Evropský Politický A Právní Diskurz: Svazek 4 2. Vydání 2017Document12 pagesEvropský Politický A Právní Diskurz: Svazek 4 2. Vydání 2017Dmytro YagunovNo ratings yet

- Countering Cyber Proliferation-Zeroing in On Access-as-a-Service PDFDocument33 pagesCountering Cyber Proliferation-Zeroing in On Access-as-a-Service PDFJanina JaniNo ratings yet

- EU Code of Conduct - JTPFDocument7 pagesEU Code of Conduct - JTPFGeorg ProkschNo ratings yet