Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Independence of Suggestibility, Placebo Response, and Hypnotizability

The Independence of Suggestibility, Placebo Response, and Hypnotizability

Uploaded by

marcelo ponce velozoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Independence of Suggestibility, Placebo Response, and Hypnotizability

The Independence of Suggestibility, Placebo Response, and Hypnotizability

Uploaded by

marcelo ponce velozoCopyright:

Available Formats

10.

The Independence of Suggestibility, Placebo Response,

and Hypnotizability

F.l. EVANS

Introduction

Suggestibility has been an important concept in the history of psychology and psychiatry. In

addition to being equated with gullibility and persuasibility (Abraham, 1962), the concept of

suggestibility has been central to the historical development of hypnosis (Weitzenhoffer, 1953),

has been used to explain the placebo response in psychopharmacology (Trouton, 1957), and has

been employed as a measure of personality characteristics, particularly neuroticism (Cattell,

1957; Eysenck, 1947). This review evaluates contemporary attempts to classify different types of

suggestibility, and the relationship between suggestibility, hypnotizability, and the placebo

response.

Classification of Suggestibility

Eysenck (1943; 1947), Furneaux (1946; 1952), and Eysenck and Furneaux (1945) presented

empirical evidence demonstrating that there is no general, unitary trait of suggestibility. Two

factors, or possibly more, were necessary to account for the intercorrelations among tests

traditionally regarded as measures of suggestibility. The main factor, primary suggestibility,

involved the subject's responding to direct (verbal) suggestions of occurrence of specified bodily

or muscular movements without his/her active volitional participation. The Body-Sway and

Chevreul Pendulum tests are familiar examples. The second factor, secondary suggestibility, is a

more elusive entity involving "indirection" and "gullibility." Eysenck (1947) has described it as

"the experience on the part of the subject of a sensation or perception consequent upon the

direct or implied suggestion by the experimenter that such an experience will take place, in the

absence of any objective basis for the sensation of perception" (p. 167). The Ink Blot, Progressive

Lines, and Odor tests are typical examples.

Without empirical support, Eysenck (1947) also referred to tertiary suggestibility, apparently

involving attitude change consequent upon persuasive communications originating from a

prestige figure.

Contemporary Evidence

The classification presented by Eysenck and Furneaux (1945) has been widely accepted.

Subsequent attempts to corroborate the original factorial studies of Eysenck (1943) and Eysenck

and Furneaux (1945) have, however, produced equivocal results. Grimes (1948) found no

145

V. A. Gheorghiu et al. (eds.), Suggestion and Suggestibility

© Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 1989

evidence of a secondary suggestibility factor among 16 tests of suggestibility administered in

group settings to 233 orphan boys varying in age from 8 to 15 years. The tests were mainly of the

indirection, gullibility, or prestige types.

Benton and Bandura (1953) objected to generalizing from the neurotic army population used in

the studies by Eysenck (1943) and Eysenck and Fumeaux (1945). They administered tests of

suggestibility to 50 undergraduates. The intercorrelations were mostly insignificant, and no

evidence of either factor was found. Unfortunately, the sample was highly selected both in

intelligence and in suggestibility. Similar criticism can be made of studies by Duke (1964) who

administered nine suggestibility tests to veterans.

Factor analytic studies from three separate correlation matrices were reported to Stukat (1958).

Sixteen variables were administered to 67 elementary school children, averaging 8.6 years of age;

24 variables were administered to 187 ll-year-old school children; and 24 variables were given

to 90 adults in their early twenties. A factor identified as primary suggestibility was isolated in all

three factorial solutions. Secondary suggestibility, as described by Eysenck and Fumeaux (1945),

was not confirmed. Several small factors were found, usually defined by very few variables with

low factor loadings.

Administering 15 suggestibility tests to 63 undergraduates, Hammer et al. (1963) reported two

orthogonal factors from a factor analysis of the tetrachoric intercorrelations. One factor was

identified as primary suggestibility, but there were no grounds for identifying the second factor

with Eysenck's concept of secondary suggestibility. Three variations of the Heat lllusion test,

together with a rating of the vividness of imagery in a suggested hallucinatory situation, defined

the second factor. It was tentatively interpreted as an "imagery" factor. Some tests which were

similar to secondary suggestibility tests in the classification of Eysenck and Fumeaux (1945) did

not load significantly on the imagery factor.

Subsequently, two parallel batteries of tests, similar to those usually administered during

hypnosis, were given in the waking state to 50 undergraduates (Evans, 1967a). Tests similar to

"secondary suggestibility" measures were not well represented. Of the five factors matched across

the two sessions, three were identified as "primary suggestibility," "challenge suggestibility," and

"imagery." The latter factor involved measures similar to the Heat Illusion.

Suggestibility

There has been a failure to replicate in exact detail the procedures employed by Eysenck (1943)

and Eysenck and Fumeaux (1945) in all these studies. The classification originally presented by

Eysenck (1943) was based upon an examination of the intercorrelations among eight

suggestibility tests, including two linearly and experimentally dependent methods of scoring both

the Progressive Weights and Progressive Lines tests. Recognizing the limitations of this

investigation, Eysenck and Fumeaux (1945) replicated the study, administering suggestibility

tests to 60 hospitalized soldiers.

146

You might also like

- Test Bank For Saunders Comprehensive Review For Nclex PN Exam 4th Edition Linda A SilvestriDocument6 pagesTest Bank For Saunders Comprehensive Review For Nclex PN Exam 4th Edition Linda A SilvestriRobert Taylor100% (33)

- How To Code RorschachDocument17 pagesHow To Code RorschachBob Zeevi100% (6)

- The+Six+Pillars+of+Self Esteem+by+Nathaniel+BrandenDocument1 pageThe+Six+Pillars+of+Self Esteem+by+Nathaniel+Branden› PHXNTOM; ‹No ratings yet

- Black Women and Choice Theory Reality TherapyDocument12 pagesBlack Women and Choice Theory Reality TherapyMiKael AshantiNo ratings yet

- The Phenomenological Approach in Psychopathology..Document25 pagesThe Phenomenological Approach in Psychopathology..Luiza Pimenta RochaelNo ratings yet

- Pitch AnythingDocument14 pagesPitch AnythingGiampaolo D'Andrea100% (4)

- Near-Death Studies and Out-of-Body Experiences in The BlindDocument47 pagesNear-Death Studies and Out-of-Body Experiences in The Blindnikesemper100% (1)

- Stone - Cognitive DissonanceDocument24 pagesStone - Cognitive DissonanceAnca DbjNo ratings yet

- The Short-Form Revised Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (EPQ-S)Document9 pagesThe Short-Form Revised Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (EPQ-S)nesumaNo ratings yet

- Rle Focus PDFDocument8 pagesRle Focus PDFCarmina AlmadronesNo ratings yet

- 4th Quarter Summative in pr1Document3 pages4th Quarter Summative in pr1Melisa Marie Naperi CloresNo ratings yet

- Session 4: OLFU Vision and & 5, History, Core Values: Our Lady of Fatima University Veritas Et MisericordiaDocument3 pagesSession 4: OLFU Vision and & 5, History, Core Values: Our Lady of Fatima University Veritas Et MisericordiaAngela100% (1)

- Barber, T. X. (1965) - Physiological Effects of 'Hypnotic Suggestions' - A Critical Review of Recent Research (1960-64) - Psychological Bulletin, 63 (4), 201-222Document22 pagesBarber, T. X. (1965) - Physiological Effects of 'Hypnotic Suggestions' - A Critical Review of Recent Research (1960-64) - Psychological Bulletin, 63 (4), 201-222Guilherme RaggiNo ratings yet

- Keywords Hermeneutic Phenomenology, Phenomenology, HusserlDocument24 pagesKeywords Hermeneutic Phenomenology, Phenomenology, HusserlClaudette Nicole Gardoce100% (1)

- Frustrative Nonreward in Partial Reinforcement and Discrimination LearningDocument23 pagesFrustrative Nonreward in Partial Reinforcement and Discrimination LearningJef_8No ratings yet

- Feist8e SG Ch14Document22 pagesFeist8e SG Ch14vsbr filesNo ratings yet

- (Eysenck, 1990) Genetic and Environmental Contributions To Individual Differences. The Three Major Dimensions of PersonalityDocument18 pages(Eysenck, 1990) Genetic and Environmental Contributions To Individual Differences. The Three Major Dimensions of PersonalityangieNo ratings yet

- G. Eysenck H.: Psychologicd ReporfsDocument9 pagesG. Eysenck H.: Psychologicd ReporfsNelson BrunoNo ratings yet

- Inderbitzin. Patients Sleep On The Analytic CouchDocument23 pagesInderbitzin. Patients Sleep On The Analytic CouchIoana Maria MateiNo ratings yet

- Eysencks Biologically Based Factor TheoryDocument5 pagesEysencks Biologically Based Factor TheoryKristine AquitNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Emotion Attributions: A Unifying View: Steven R. Truax 1Document22 pagesDeterminants of Emotion Attributions: A Unifying View: Steven R. Truax 1Sanjib Kumar JenaNo ratings yet

- Classics in The History of Psychology - Bruner & Goodman (1947)Document11 pagesClassics in The History of Psychology - Bruner & Goodman (1947)Federico WimanNo ratings yet

- Epq-R (Forma Scurta)Document9 pagesEpq-R (Forma Scurta)minodoraNo ratings yet

- Eysenck 1991Document17 pagesEysenck 1991Magda MoldovanNo ratings yet

- Psihobiologia PersonalitatiiDocument6 pagesPsihobiologia PersonalitatiiDav Ina100% (1)

- Personality and Reinforcement in AssociaDocument25 pagesPersonality and Reinforcement in AssociaAnggaNo ratings yet

- Forming Impressions of PersonalityDocument31 pagesForming Impressions of PersonalityFurther InstructionsNo ratings yet

- Rice Shelby 1967Document49 pagesRice Shelby 1967Todva MhlangaNo ratings yet

- Burke Heuer Emotional Story 1992Document14 pagesBurke Heuer Emotional Story 1992ousia_rNo ratings yet

- Introducing An Existential-Phenomenological Approach: Part 1 - Basic Phenomenological Theory and Research by Ian Rory OwenDocument14 pagesIntroducing An Existential-Phenomenological Approach: Part 1 - Basic Phenomenological Theory and Research by Ian Rory OwenPelagyalNo ratings yet

- Analytic Induction, Norman K. DenzinDocument2 pagesAnalytic Induction, Norman K. Denzincarlosusass100% (1)

- Bruner & Postman (1947) Value and Need As Organizing Factors in PerceptionDocument20 pagesBruner & Postman (1947) Value and Need As Organizing Factors in PerceptionNatália BarrosNo ratings yet

- The Nature of Epiphanic Experience: KeywordsDocument27 pagesThe Nature of Epiphanic Experience: KeywordsbrcgomezleNo ratings yet

- Edith Stein and Tania Singer A ComparisoDocument26 pagesEdith Stein and Tania Singer A Comparisomirjana pinezićNo ratings yet

- Phenomenology and Psychophysics - HorstDocument21 pagesPhenomenology and Psychophysics - HorstRose DarugarNo ratings yet

- Delprato (2009) - Sketch of J. R. Kantor's Psychological Interbehavioral Field TheoryDocument8 pagesDelprato (2009) - Sketch of J. R. Kantor's Psychological Interbehavioral Field TheoryPedro Sánchez LópezNo ratings yet

- Personality Essa Hans EysenckDocument4 pagesPersonality Essa Hans EysenckNur Ainun HafizahNo ratings yet

- Value and Need As Organizing Factors in Perception (1947) Jerome S. Bruner and Cecile C. Goodman Harvard UniversityDocument14 pagesValue and Need As Organizing Factors in Perception (1947) Jerome S. Bruner and Cecile C. Goodman Harvard UniversitymchlspNo ratings yet

- Looking at Pictures: Affective, Facial, Visceral, and Behavioral ReactionsDocument14 pagesLooking at Pictures: Affective, Facial, Visceral, and Behavioral ReactionsieysimurraNo ratings yet

- Bruner & Goodman (1947)Document12 pagesBruner & Goodman (1947)Hugo SantanaNo ratings yet

- Emil Boller - Examining PsychokinesisDocument27 pagesEmil Boller - Examining PsychokinesisMatCultNo ratings yet

- History of Experimental PsychologyDocument7 pagesHistory of Experimental PsychologyRhain GarciaNo ratings yet

- Concept of The Stimulus in Psychology - GibsonDocument10 pagesConcept of The Stimulus in Psychology - GibsonwalterhornNo ratings yet

- 191511-History of Experimental PsyDocument3 pages191511-History of Experimental Psyumar farooqNo ratings yet

- Lecture 12 Hans Eysenck - Life and Dimensions of Personality 16112022 122601pmDocument7 pagesLecture 12 Hans Eysenck - Life and Dimensions of Personality 16112022 122601pmm.muneeb raufNo ratings yet

- Speaking With One's Self: Shahar Arzy, Moshe Idel, Theodor Landis & Olaf BlankeDocument14 pagesSpeaking With One's Self: Shahar Arzy, Moshe Idel, Theodor Landis & Olaf BlankeIbnqamarNo ratings yet

- Notes On A Troubled Reception History: Christian Ferencz-Flatz & Andrea StaitiDocument20 pagesNotes On A Troubled Reception History: Christian Ferencz-Flatz & Andrea StaitiSardanapal ben Esarhaddon100% (1)

- Theories of PersonalityDocument8 pagesTheories of PersonalityRhaine Antoinette BattungNo ratings yet

- Bruner and GoodmanDocument12 pagesBruner and Goodmanclaulop13No ratings yet

- Emotionality, Repression-Sensitization, and Maladjustment: Brie. 3. Psychiat. (1965), Iii, 399-404Document7 pagesEmotionality, Repression-Sensitization, and Maladjustment: Brie. 3. Psychiat. (1965), Iii, 399-404dodoNo ratings yet

- Exp Psy HistoryDocument5 pagesExp Psy Historykankshi ChopraNo ratings yet

- Personality Walter MischelDocument1 pagePersonality Walter MischelNur Ainun HafizahNo ratings yet

- Gordon Willard AllportDocument13 pagesGordon Willard AllportZIM6662No ratings yet

- Can Existential Phen Thepory and Epist Congruent With Empirical WorldDocument15 pagesCan Existential Phen Thepory and Epist Congruent With Empirical WorldAna Teresa MirandaNo ratings yet

- Wapner - The Sensory-Tonic Field Theory of PerceptionDocument23 pagesWapner - The Sensory-Tonic Field Theory of PerceptionupanddownfileNo ratings yet

- Some Effects of Spinal Cord Lesions On Experienced Emotional FeelingsDocument15 pagesSome Effects of Spinal Cord Lesions On Experienced Emotional FeelingsLuís FernandoNo ratings yet

- From The Binet Simon To The Wechsler Bellevue: Tracing The History of Intelligence TestingDocument23 pagesFrom The Binet Simon To The Wechsler Bellevue: Tracing The History of Intelligence TestingAlan MuñozNo ratings yet

- Eysenck, McCrae, and CostaDocument2 pagesEysenck, McCrae, and CostaChriza Mae Dela Pe�aNo ratings yet

- 1992 Eysenck - The Definition and Measurement of Psychoticism Personality andDocument29 pages1992 Eysenck - The Definition and Measurement of Psychoticism Personality andAnoop AnandNo ratings yet

- Wolfberg PSYC 360Document33 pagesWolfberg PSYC 360dom dean silvaNo ratings yet

- Articol Loftus - Jane DoeDocument29 pagesArticol Loftus - Jane DoeCosmina MihaelaNo ratings yet

- What Determines A Feeling's Position in Affective PDFDocument23 pagesWhat Determines A Feeling's Position in Affective PDFMary GomezNo ratings yet

- Articol 2Document20 pagesArticol 2Mona IcaNo ratings yet

- Advanced ESP TestingDocument252 pagesAdvanced ESP TestingShane HillNo ratings yet

- S F and His Impact To The WorldDocument12 pagesS F and His Impact To The WorldVictoria CoslNo ratings yet

- Overwalle 1992Document17 pagesOverwalle 1992vladimir216No ratings yet

- Section Psychiatry: Medicine I-Oetg Oa OttDocument6 pagesSection Psychiatry: Medicine I-Oetg Oa OttBóngMa TrongTimNo ratings yet

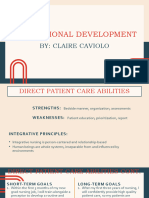

- Professional Development: By: Claire CavioloDocument11 pagesProfessional Development: By: Claire Cavioloapi-708272588No ratings yet

- PJ04 Care Practitioner Job DescriptionDocument2 pagesPJ04 Care Practitioner Job DescriptionIsabela FecheteNo ratings yet

- English ProjectDocument6 pagesEnglish Projectdhaarshu kuttyNo ratings yet

- OT 1025 - IADL Universal DesignDocument46 pagesOT 1025 - IADL Universal DesignRidz FNo ratings yet

- 8-Simple Regression AnalysisDocument9 pages8-Simple Regression AnalysisSharlize Veyen RuizNo ratings yet

- Lesson - 9 PerdevDocument23 pagesLesson - 9 PerdevBianca BucsitNo ratings yet

- What Is SuicideDocument10 pagesWhat Is SuicideKwenzie FortalezaNo ratings yet

- Dr. Sunetta, Monga, Measuring What MattersDocument3 pagesDr. Sunetta, Monga, Measuring What MattersU of T MedicineNo ratings yet

- Manual For Research Project 8613-For OnlineDocument32 pagesManual For Research Project 8613-For OnlineMarrah MarrahNo ratings yet

- Read The Text and Choose The Best Answer. Write Your Answers (A, B, C, or D) in The Numbered BoxDocument4 pagesRead The Text and Choose The Best Answer. Write Your Answers (A, B, C, or D) in The Numbered Boxhuu hungNo ratings yet

- Book Review-1: The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People Submitted ToDocument19 pagesBook Review-1: The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People Submitted ToGayatri G.No ratings yet

- Gerontik Setelah UtsDocument93 pagesGerontik Setelah UtsNidaa NabiilahNo ratings yet

- Idioms IllnessDocument9 pagesIdioms Illnessrafael gomezNo ratings yet

- The Principles of Performance ManagementDocument20 pagesThe Principles of Performance ManagementGrace MasdoNo ratings yet

- Study Notebook Module 2 Modified With AnswerDocument4 pagesStudy Notebook Module 2 Modified With AnswerRandy MagbudhiNo ratings yet

- Ram Post ReflectionDocument4 pagesRam Post Reflectionapi-402053549No ratings yet

- Post Graduate Diploma in Dance Movement Therapy 2023-24Document11 pagesPost Graduate Diploma in Dance Movement Therapy 2023-24sushikaNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Incentives On Job Performance BusineDocument14 pagesThe Impact of Incentives On Job Performance BusineSuperior McCowinNo ratings yet

- Module 4.3 - Joyce TravelbeeDocument2 pagesModule 4.3 - Joyce Travelbeeidk lolNo ratings yet

- 2NCP Dystocia Fetal MalpositionDocument2 pages2NCP Dystocia Fetal MalpositionMark FernandezNo ratings yet

- Written Assignment Unit 2 University of The People HS 2711-Health Science 1 Gloria Okereke (Instructor) April 20, 2022Document6 pagesWritten Assignment Unit 2 University of The People HS 2711-Health Science 1 Gloria Okereke (Instructor) April 20, 2022Zyon XadaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Quantitative Research: Activity 1A: True or FalseDocument5 pagesIntroduction To Quantitative Research: Activity 1A: True or FalseGwenn ColantroNo ratings yet