Professional Documents

Culture Documents

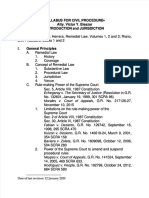

Remedial Law Compendium by Regalado PDF

Remedial Law Compendium by Regalado PDF

Uploaded by

Huffletot0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

232 views922 pagesOriginal Title

Remedial-Law-Compendium-by-Regalado-pdf.pdf

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

232 views922 pagesRemedial Law Compendium by Regalado PDF

Remedial Law Compendium by Regalado PDF

Uploaded by

HuffletotCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 922

REMEDIAL LAW

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

1. Classification of courts in the Philippines:

a. Courts of general jurisdiction: Those_competent

to decide their own jurisdiction and to take cognizance of

which have no power to decide their own jurisdiction and

can_only try cases . Example:

Municipal Trial Courts.

Th had

the rank of ut were courts of

special jurisdiction. ey have been

integrated into the Regional Trial Courts as branches)

thereof.

b. Courts of original jurisdiction: Those courts in

which, under the law, actions or proceedings may

originally be commenced.

Courts of appellate jurisdiction: Courts which have

the power to review on appea lecisions or orders of

a lower court.

c. Ce Courts which have the power of

review or supervision over another and lower court.

. Those which, in relation to another

court, are lower in rank and subject to review and super-

vision by the latter.

While, in a generic sense, a court is considered an

inferior court in relation to the powers of another tribunal

higher in rank, in its technical sense and unless otherwise

intended, it was formerly provided that the phrase

REMEDIAL LAW COMPENDIUM

“inferior court” referred to the then municipal or city

courts (former Sec. 1, Rule 5, in relation to R.A. 3820

and R.A. 3828), now called Metropolitan, Municipal, and

Municipal Circuit Trial Courts. Note, also, that under

Sec. 2, Rule 5, the term “municipal trial court” as used in

these revised Rules includes all other courts of the

same rank. In legal circles, they are also called “courts

of the first level.” In some official issuances, the Supreme

Court refers to them as “first level courts.”

However, the “inferior courts” whose decisions are

subject to the appellate jurisdiction of the Supreme

Court (Sec. 17, R.A. 296) refer to all the courts lower

than the Supreme Court. The term “lower courts” is now

used for that purpose in the 1987 Constitution (Sec. 5/2],

Art. VIII), in lieu of “inferior courts” used in the 1935

and 1973 Constitutions.

d. Courts of record: Those whose proceedings are

enrolled and which are bound to keep a written record

of all trials and proceedings handled by them (see Luzano

us. Romero, et al., L-33245, Sept. 30, 1971).

Courts not of record: Courts which are not required

to keep a written record or franscript of proceedings

held therein.

Prior to the effectivity of R.A. 6031 on August 4,

1969, inferior courts were not of record; but if a municipal

court of the capital of a province or a city court tried a

criminal case wherein the imposable penalty is

imprisonment of more than 6 months but not exceeding

6 years and/or a fine of more than P200 but not exceeding

P6,000, its proceedings were required to be recorded as

its decisions were appealable to the Court of Appeals or

the Supreme Court (R.A. 296, as amended by R.A. 2613

and R.A. 3828, Sec. 87{c], last paragraph). However,

under R.A. 2613, amending Sec. 45, R.A. 296, all inferior

courts are now required to record their proceedings and

are accordingly courts of record.

2

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

e. Constitutional courts: Those which owe their

creation and existence to the Constitution and, therefore

cannot be legislated out of existence or deprived by law

of the jurisdiction and powers unqualifiedly vested in

them by the Constitution. The Supreme Court and the

Sandiganbayan are the only courts specifically provided

for in the Constitution. With regard to the latter, the

better view is that the Sandiganbayan is only a

constitutionally-mandated court since, although its

existence is provided for in the Constitution, its creation

was by statutory enactment.

Statutory courts: Those created, organized and

with jurisdiction exclusively determined by law.

Accordingly, all other courts in the Philippines are

statutory courts.

2. The Court of Tax Appeals created by R.A. 1125

has been held to be a part of the judicial system vested

with special jurisdiction to act only on protests of private

persons adversely affected by the tax, customs or

assessment laws (Ursal us. CTA, et al., 101 Phil. 209).

On March 30, 2004, said law was amended by R.A.

9282 expanding the jurisdiction of the Court of Tax

Appeals (CTA) and elevating its rank to the level of a

collegiate court with special jurisdiction, of the same level

as the Court of Appeals, and consisting of a Presiding

Justice and 5 Associate Justices who shall sit en banc or

in 2 divisions of 3 justices each. The court shall, inter

alia, have exclusive appellate jurisdiction to review

decisions of the Commissioner of Internal Revenue in

disputes arising from the tax law administered by the

Bureau of Internal Revenue, the Regional Trial Courts in

local tax cases, the Commissioner of Customs in matters

administered by the Bureau of Customs, the Central Board

of Assessment Appeals in assessments of real property,

the Secretary of Finance and the Secretary of Trade

and Industry in matters specified therein. The decision

3

REMEDIAL LAW COMPENDIUM

of said court en banc may be reviewed by the Supreme

Court on certiorari pursuant to Rule 45 of the Rules of

Court (see Appendix CC).

3. The distinction obtaining in other jurisdictions

between courts of law and courts of equity, and among

civil, criminal and probate courts, does not apply in the

Philippines wherein all courts are courts both of law and

equity (Rustia vs. Franco, 41 Phil. 280; Roa, et al. vs.

CA, et al., L-27294, June 28, 1983; Galman, et al. vs.

Sandiganbayan, et al., G.R. No. 72670, Sept. 12, 1986);

and Regional! Trial Courts and, to a limited extent, the

lower courts, exercise jurisdiction, according to the case

involved, as civil, criminal or probate courts or courts of

land registration. Before B.P. Blg. 129 became operative,

there were special courts, such as the Juvenile and

Domestic Relations Courts, the Circuit Criminal Courts

and the Courts of Agrarian Relations, which were courts

exercising only limited and special jurisdiction.

4. Under our present statutory and jurisprudential

taxonomy, jurisdiction is classified, based on its nature,

as follows:

a. General jurisdiction, or the power to adjudicate

all controversies except those expressly withheld from the

plenary powers of the court; and special or limited

jurisdiction, which restricts the court’s jurisdiction only

to particular cases and subject to such limitations as may

be provided by the governing law.

b. Original jurisdiction, or the power of the court to

take judicial cognizance of a case instituted for judicial

action for the first time under conditions provided by law;

and appellate jurisdiction, or the authority of a court

higher in rank to reexamine the final order or judgment

of a lower court which tried the case now elevated for

judicial review.

c. Exclusive jurisdiction, or the power to adjudicate

a case or proceeding to the exclusion of all other courts

4

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

at that stage; and concurrent jurisdiction, sometimes

referred to as confluent or coordinate jurisdiction, which

is the power conferred upon different courts, whether of

the same or different ranks, to take cognizance at the

same stage of the same case in the same or different

judicial territories.

Concurrent original jurisdiction between trial courts

of different ranks has in the main been eliminated by

B.P. Blg. 129. For instance, there is no more concurrent

jurisdiction in adoption or guardianship proceedings

between inferior courts and the present Regional Trial

Courts as was provided by the Judiciary Act with respect

to the former Courts of First Instance, which Act also

provided for concurrence in criminal cases and special

civil actions. However, as among courts of the same rank,

it appears that a phase of concurrent original jurisdiction

still obtains in some instances as, for example, in civil

and criminal cases for libel or the settlement of the estate

of a nonresident with properties in different judicial

regions. Withal, in point of strict law, these situations

are matters of venue except in criminal cases for libel,

since in criminal procedure, venue is, as a rule,

jurisdictional. For a discussion of other criminal cases

covered by the same rule, see the Preliminary

Considerations in Criminal Procedure in Volume Two of

this work. Where such concurrence exists, the court first

taking cognizance of the case does so to the exclusion of

the other courts, although the Supreme Court may order

a transfer of venue or place of trial to another court of

competent jurisdiction.

At any rate, B.P. Blg. 129 provides for concurrent

original jurisdiction between the Supreme Court and

either the Court of Appeals or the Regional Trial Courts,

or among all three courts in certain cases. To illustrate,

the Supreme Court has concurrent original jurisdiction

with the Court of Appeals in petitions for the issuance of

writs of certiorari, prohibition and mandamus against

5

REMEDIAL LAW COMPENDIUM

the Regional Trial Courts; with the Court of Appeals and

the Regional Trial Courts over the same petitions against

the inferior courts; and with the Regional Trial Courts

in actions affecting ambassadors, other public ministers

and consuls.

5. Also, under B.P. Blg. 129, delegated jurisdiction

is provided for, i.e., the grant of authority to inferior

courts to hear and determine cadastral and land

registration cases under certain conditions (see Sec. 34,

infra); and special jurisdiction, which is the power of

inferior courts to hear and decide petitions for a writ of

habeas corpus or applications for bail in the absence of

all the Regional Trial Judges in the province or city (see

Sec. 35, infra). This latter type of jurisdiction was

formerly included, with variations, in what was known

as the interlocutory jurisdiction of inferior courts under

the Judiciary Act.

6. Mention must also be made of the territorial

jurisdiction of a court, which refers to the geographical

area within which its powers can be exercised. As

already stated, this assumes importance in criminal cases

wherein considerations of the territory vis-d-vis the locus

of the crime determine not only the venue of the case

but the jurisdiction of the court; and, in civil cases, the

venue of real or mixed actions. In all cases, the Supreme

Court and the Court of Appeals have national jurisdiction;

the Regional Trial Courts have regional jurisdiction; and

the inferior courts have such territorial jurisdiction as

may be defined by the Supreme Court pursuant to Secs.

25, 28 and 31, B.P. Blg. 129.

Other classifications of original jurisdiction are based

on the subject-matter or the nature of the action being

tried by the court, such as civil, criminal, probate,

admiralty and maritime, juvenile and domestic relations,

agrarian, and land registration. Most of these different

areas of jurisdiction are exercised by the regular trial

6

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

courts, since the special courts like the circuit criminal

courts and the juvenile and domestic relations courts have

been abolished. With respect to the latter, domestic cases

are now generally handled by the newly created Family

Courts, hereinafter discussed. Other subjects of

controversies requiring special training and knowledge,

such as taxation, labor and securities, are handled by

quasi-judicial agencies, subject to the power of judicial

review by the appellate courts.

7. Jurisdiction and venue are distinguished as

follows:

a. Jurisdiction is the authority to hear and

determine a case; venue is the place where the case is to

be heard or tried.

b. Jurisdiction is a matter of substantive law; venue,

of procedural law.

c. Jurisdiction establishes a relation between the

court and the subject-matter; venue, a relation between

plaintiff and defendant, or petitioner and respondent.

d. Jurisdiction is fixed by law and cannot be

conferred by the parties; venue may be conferred by the

act or agreement of the parties (Manila Railroad Co. vs.

Attorney-General, 20 Phil. 523).

In criminal cases, the venue of the crime goes into

the territorial jurisdiction of the court (Lopez us. Paras,

L-25795, Oct. 29, 1966), hence where the criminal action

is instituted not in the place specified by the Rules and

declared by the substantive law as within the territorial

jurisdiction of the trial court, the motion to quash should

be grounded on lack of jurisdiction, and not improper

venue.

8, The authority to decide a case and not the decision

rendered therein is what makes up jurisdiction. Where

there is jurisdiction, the decision of all questions arising

in the case is but an exercise of jurisdiction (De la Cruz

7

REMEDIAL LAW COMPENDIUM

us. Moir, 36 Phil. 213; Associated Labor Union vs.

Ramolete, L-23527, Mar. 31, 1965). Consequently, a

court may have jurisdiction over the case but at the

same time act in excess of such jurisdiction.

9. The errors which a court may commit in the

exercise of jurisdiction differ from errors of judgment.

The former is reviewable in an original action for

certiorari, while the latter is correctible by appeal

(Henderson, et al. vs. Tan, etc., et al., 87 Phil. 466;

Maritime Co. of the Phil. vs. Paredes, L-24811, Mar. 3,

1967; Bulan vs. Masakayan, L-24428, June 26, 1968;

Palma us. Q & S, Inc., L-20366, May 19, 1986). Errors

of jurisdiction render a judgment void or, at least

voidable (see Sec. Ifa] and [b], Rule 16; Rule 65), while

errors of judgment are grounds for reversal only if it is

shown that prejudice has been caused thereby (Banco

Espanol-Filipino vs. Palanca, 37 Phil. 821; Bimeda us.

Perez, et al., 93 Phil. 636).

10. Requisites for the exercise of jurisdiction and

how the court acquires such jurisdiction:

a. Jurisdiction over the plaintiff or petitioner: This

is acquired by the filing of the complaint, petition or

initiatory pleading before the court by the plaintiff or

petitioner.

b. Jurisdiction over the defendant or respondent:

This is acquired by the voluntary appearance or

submission by the defendant or respondent to the

court or by coercive process issued by the court to

him, generally by the service of summons (Sharuff vs.

Bubla, L-17029, Sept. 30, 1964; Aban vs. Enage,

L-30666, Feb. 25, 1983).

c. Jurisdiction over the subject-matter: This is con-

ferred by law and, unlike jurisdiction over the parties,

cannot be conferred on the court by the voluntary act or

agreement of the parties.

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

d. Jurisdiction over the issues of the case: This is

determined and conferred by the pleadings filed in the

case by the parties, or by their agreement in a pre-trial

order or stipulation, or, at times, by their implied consent

as by the failure of a party to object to evidence on an

issue not covered by the pleadings, as provided in Sec. 5,

Rule 10 (see Lazo, et al. vs. Republic Surety & Insurance

Co., Inc., L-27365, Jan. 30, 1970).

e. Jurisdiction over the res (or the property or thing

which is the subject of the litigation): This is acquired

by the actual or constructive seizure by the court of the

thing in question, thus placing it in custodia legis, as in

attachment or garnishment; or by provision of law

which recognizes in the court the power to deal with the

property or subject-matter within its territorial juris-

diction, as in land registration proceedings or suits

involving civil status or real property in the Philippines

of a nonresident defendant.

In two instances, the court acquires jurisdiction to

try the case, even if it has not acquired jurisdiction over

the person of a nonresident defendant, as long as it has

jurisdiction over the res, as when the action involves the

personal status of the plaintiff or property in the Phil-

ippines in which the defendant claims an interest (see

Sec. 15, Rule 14). In such cases, the service of summons

by publication and notice to the defendant is merely

to comply with due process requirements (Banco

Espanol-Filipino vs. Palanca, 37 Phil. 921; De Midgely

us. Ferandos, et al., L-34314, May 13, 1975). Under

Sec. 133 of the Corporation Code, while a foreign

corporation doing business in the Philippines without a

license cannot sue or intervene in any action here, it may

be sued or proceeded against before our courts or

administrative tribunals.

11. As a general proposition, the jurisdiction of the

court is determined by the statute in force at the time of

the commencement of the action (People vs. Paderna,

9

REMEDIAL LAW COMPENDIUM

L-28518, Jan. 29, 1968; People vs. Mariano, et al.,

L-40527, June 30, 1976; Lee, et al. vs. Presiding Judge,

etc., et al., G.R. No. 68789, Nov. 10, 1986), unless such

statute provides for its retroactive application, as where

it is a curative legislation (Atlas Fertilizer Corp. us.

Navarro, etc., et al., G.R. No. 72074, April 30, 1987).

12. The settled rule is that the jurisdiction of the

court over the subject-matter is determined by the alle-

gations of the complaint (Edward J. Nell & Co. us.

Cubacub, L-20843, June 23, 1965; Time, Inc. us. Reyes,

et al., L-28882, May 31, 1971; Ganadin us. Ramos, et

al., L-23547, Sept. 11, 1980), but this rule is not without

exceptions. Thus, it was held that while the allegations

in the complaint make out a case for forcible entry, where

tenancy is averred by way of defense and is proved to be

the real issue, the case should be dismissed for lack of

jurisdiction as the case should properly be filed with the

then Court of Agrarian Relations (Ignacio vs. CFI of

Bulacan, L-27897, Oct. 29, 1971). However, with the

integration of the courts of agrarian relations as branches

of the Regional Trial Courts under B.P. Blg. 129, the

case was required to be filed with the corresponding

Regional Trial Court if it was within the jurisdiction

thereof, for assignment to the appropriate branch. Also,

although the allegations in the complaint make out a case

cognizable by a Regional Trial Court, where, however,

the acts complained of are shown at the trial to be

interwoven with an unfair labor practice case, the action

should be dismissed since jurisdiction is vested in the

National Labor Relations Commission. This is so since

the Rules now permit a motion to dismiss based upon

facts not alleged in the complaint (Mindanao Rapid Co.,

Inc. vs. Omandam, et al., L-23058, Nov. 27, 1971, jointly

deciding therein L-23473, 23871, 24232, 24718 and

24956).

13. Where the complaint is for actual damages of

P978, but the other claims for damages and attorney's

10

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

fees bring the total relief sought to more than P10,000

(which was then the jurisdictional limit for civil cases in

the inferior courts), the totality of said claims puts the

case within the jurisdiction of the then Court of First

Instance and the trial court erred in dismissing the

complaint upon its mere impression that the other claims

were “bloated” for the purpose of invoking its jurisdiction,

without hearing and proof of such fact (Enerio us.

Alampay, L-40010, May 26, 1975; Ratila vs. Tapucar,

L-45018, Jan. 24, 1977). This doctrine is still applicable

subject to the increased jurisdictional amount under

B.P. Blg. 129 and subsequent legislation.

14. The jurisdiction of a court, whether in criminal

or civil cases, once it attaches cannot be ousted by

subsequent happenings or events although of a charac-

ter which would have prevented jurisdiction from

attaching in the first instance (Ramos, et al. vs. Central

Bank, L-29352, Oct. 4, 1971, and cases therein cited;

Dioquino vs. Cruz, et al., L-38579, Sept. 9, 1982) and it

retains jurisdiction until it finally disposes of the case

(Republic us. Pielago, et al., G.R. No. 72218, July 21,

1986).

15. The constitutionality of a statute must be ques-

tioned at the earliest opportunity, except in criminal

cases where the question may be raised at any stage and,

in civil cases, if the determination of the question is

necessary for the decision of the case, even if raised for

the first time on appeal. A constitutional question will

also be considered by the appellate court at any time if it

involves the jurisdiction of the court a quo. The same

rule applies to ordinances (San Miguel Brewery, Inc. vs.

Magno, L-21879, Sept. 9, 1967).

16. Basic in the law on procedure is the doctrine that

the jurisdiction of a court over the subject-matter of an

action is conferred only by the Constitution or the law

and that the Rules of Court yield to substantive law, in

ll

REMEDIAL LAW COMPENDIUM

this case, the Judiciary Act and B.P. Big. 129, both as

amended, and of which jurisdiction is only a part.

Jurisdiction cannot be fixed by the agreement of the

parties; it cannot be acquired through, or waived, en-

larged or diminished by, any act or omission of the

parties; neither can it be conferred by the acquiescence

of the court (De Jesus, et al. vs. Garcia, et al., L-26816,

Feb. 28, 1967; Calimlim, et al. vs. Ramirez, et al.,

L-34363, Nov. 19, 1982). Jurisdiction must exist as a

matter of law (People us. Casiano, L-15309, Feb. 16,

1961), Consequently, questions of jurisdiction may be

raised for the first time on appeal even if such issue

was not raised in the lower court (Government us.

American Surety Co., 11 Phil. 203; Vda. de Roxas vs.

Rafferty, 37 Phil. 957; People vs. Que Po Lay, 94 Phil.

640). A court can motu proprio dismiss a case which is

outside its jurisdiction (Sec. 1, Rule 9).

17. Nevertheless, in some cases, the principle of

estoppel by laches has been availed of by our appellate

courts to bar attacks on jurisdiction and this principle

has been applied to both civil and criminal cases, thus:

a. Inthe early case of Santiago, et al. vs. Valenzuela

(78 Phil. 397), it was held that if a motion to dismiss the

appeal, on the ground that said appeal was perfected out

of time, is filed for the first time with the appellate court

after the appellant had paid the docket fee and the cost

of printing the record on appeal, and after the filing of

appellant’s brief, the appellate court should deny the

motion as the appellee may be considered in estoppel by

his failure to object on time.

This doctrine was subsequently abandoned in

Miranda vs. Guanzon (92 Phil. 168) since the “require-

ment regarding the perfection of an appeal within the

reglementary period is not only mandatory but juris-

dictional,” a ruling subsequently reiterated in Garganta

vs. CA (105 Phil. 412), Valdez vs. Ocumen (106 Phil.

12

GENERAL PRINCIPLES.

929), Galima us. CA (L-21046, Jan. 31, 1966), Antique

Sawmills, Inc. vs. Zayco (L-20051, May 30, 1966), Roque

us. Vda. de Del Rosario (L-24873, Sept. 23, 1966) and

Arellano, et al. us. CA, et al. (L-31856, Nov. 24, 1972).

b. In the later case, however, of Tijam us. Sibong-

hanoy, et al. (L-21450, April 15, 1968), the co-defendant

surety company never raised the issue of jurisdiction in

the Court of First Instance despite several opportunities

to do so and, although the claim being for only P1,908,

the case was within the exclusive original jurisdiction

of the municipal court. It was only after the court of

Appeals had affirmed the decision of the trial court in

favor of the plaintiff but before the finality of this

decision of the Court of Appeals that the co-defendant

surety company filed its motion to dismiss on the ground

of lack of original jurisdiction of the trial court. Denying

said motion, the Supreme Court stated: “Were we to

sanction such conduct on its part, we would in effect be

declaring as useless all the proceedings had in the present

case since it was commenced on July 19, 1948 and compel

the judgment creditors to go up their Calvary once more.

The inequity and unfairness of this is not only patent

but revolting.” It further stated that “after voluntarily

submitting a cause and encountering an adverse decision

on the merits, it is too late for the loser to question the

jurisdiction or power of the court .. . it is not right for

a party who has affirmed and invoked the jurisdiction

of a court in a particular matter to secure an affirmative

relief, to afterwards deny that same jurisdiction to

escape a penalty,” citing Pindangaz, etc. vs. Dans, et al.

(L-14591, Sept. 26, 1962), Young Men’s Labor Union,

etc. vs. CIR, et al. (L-20307, Feb. 26, 1965) and Mejia

us. Lucas (100 Phil. 277). See also Capilitan us. De la

Cruz, (L-29536-37, Feb. 28, 1974), Summit Guaranty vs.

CA, et al. (G.R. No. 51139, Dec. 14, 1981), Tajonera, et

al. vs. Lumaroza, et al. (L-48907 & L-49035, Dec. 19,

1981), Nieva vs. Manila Banking Corp. (L-30811,

13

REMEDIAL LAW COMPENDIUM

Sept. 2, 1983), Florendo, et al. vs. Coloma, et al. (G.R.

No. 60544, May 19, 1984), and Medijia us. Patcho

(L-30310, Oct. 23, 1984).

c. In Rodriguez us. CA (L-29264, Aug. 29, 1969), the

action involved property worth more than P200,000, at

that time within the exclusive appellate jurisdiction of the

Supreme Court. Despite several opportunities to raise that

issue in the Court of Appeals where the appeal was taken,

defendant did not challenge the appellate jurisdiction of

the court and did so only after decision was rendered

therein against him. He raised the issue of jurisdiction,

for the nullification of the decision of the Court of Appeals,

when the case was on appeal in the Supreme Court. The

Supreme Court denied his plea under the doctrine of

estoppel by laches.

d. The same ruling was applied in Crisostomo vs.

CA, et al. (L-27166, Mar. 25, 1970) and Libudan us. Gil

(L-21163, May 17, 1972) under the justification that

“the principle of estoppel is in the interest of a sound

administration of the laws,” citing the Tijam case. The

Supreme Court pointed out that the doctrine of laches is

“based upon grounds of public policy which requires, for

the peace of society, the discouragement of stale claims”

and “is principally a question of the inequity or unfair-

ness of permitting a right or claim to be enforced or

asserted.”

e. In Sarmiento us. Salud (L-25211, Aug. 18, 1972),

the Supreme Court, in resolving the motion for recon-

sideration filed therein, held that while it is true that

a record on appeal must show on its face that it was

perfected on time and such requirement is jurisdictional

in nature, nevertheless if the record on appeal does not

comply with this requirement but the motion to dismiss

the appeal is filed more than 6 months after the appellee

filed his brief, the motion should be denied.

The same ruling was applied in Dequito vs. Lopez

(L-27757, Mar. 28, 1968) involving virtually the same set

14

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

of facts. These rulings would still apply in cases wherein

a record on appeal is required, as where multiple appeals

are allowed or in special proceedings.

f. In Vera us. People (L-31218, Feb. 18, 1970), it

was held that while a judgment is null and void where it

was promulgated when the presiding judge had already

ceased to hold office, since the accused failed to raise that

issue in the trial court and only did so after the Court of

Appeals had rendered a judgment adverse to him, it

would be an injustice if all the proceedings had in the

case would be set aside since, after all, the court that

rendered sentence was one of competent jurisdiction.

The case of Carillo us. Allied Workers’ Association of the

Philippines (L-23689, July 31, 1968) was cited in support

of this ruling.

g-. In People us. Casuga (L-37642, Oct. 22, 1973),

the accused was convicted of grave slander, which

offense was within the concurrent jurisdiction of the

then Courts of First Instance and the municipal courts

of capitals of provinces or the City Courts. Instead of

appealing to the then Court of Appeals or the Supreme

Court, as would have been proper, he appealed to the

Court of First Instance which affirmed said conviction.

On his subsequent challenge to the appellate jurisdiction

exercised by the Court of First Instance, the Supreme

Court held that the accused, having taken his appeal

to the Court of First Instance, is in estoppel to challenge

the appellate jurisdiction of the said court.

h. In People vs. Tamani (L-22160-61, Jan. 21,

1974), although the appeal of the accused was demon-

strably filed out of time, the Supreme Court nevertheless

reviewed the case and rendered a judgment on the merits

thereof, while declaring in the same decision the dismissal

of the appeal, in view of the fact that the filing of the

appeal out of time was due to the fault of the defense

counsel and the further consideration that the briefs for

the parties had already been filed.

16

REMEDIAL LAW COMPENDIUM

i. The doctrine laid down in Tijam vs. Sibong-

hanoy, supra, has been reiterated in many succeeding

cases and is still good case law. The rule up to now is

that a party’s active participation in all stages of a case

before the trial court, which includes invoking the court's

authority to grant affirmative relief, effectively estops

such party from later challenging the jurisdiction of

the said court (Gonzaga, et al. us. CA, et al., G.R.

No. 144025, Dec. 27, 2002).

j. See, moreover, the summary in Figueroa us. People

of the Philippines (G.R. No. 147406, July 14, 2008) which

apparently presents the prevailing position of the Supreme

Court on the issue of when a litigant is estopped by laches

from assailing the jurisdiction of a court, in light of its

other and subsequent holdings on the matter.

18. Jurisdiction over a person may also be acquired

even if he was never impleaded nor summoned in the

action as a defendant if he thereafter voluntarily

submitted himself to the jurisdiction of the court. Thus,

where the spouses voluntarily signed the compromise

agreement to guarantee the payment by the original

impleaded defendants, and that compromise agreement

was approved and made the basis of the judgment

rendered by the court, said spouses are bound by the

judgment as they are in estoppel to deny the very autho-

rity which they invoked. By voluntarily entering into

the compromise agreement, they effectively submitted

themselves to the jurisdiction of the court (Rodriguez,

et al. us. Alikpala, et al., L-38314, June 25, 1974).

19. Since a Court of First Instance (now, the

Regional Trial Court) is a court of general original

jurisdiction, whether a particular matter should be

resolved by it in the exercise of its general jurisdiction,

or in its limited jurisdiction as a probate or land

registration court, is not a jurisdictional question but

a procedural question involving a mode of practice

16

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

which, therefore, may be waived (Manalo us. Mariano,

et al., L-33850, Jan. 22, 1976; Santos vs. Banayo,

L-31854, Sept. 9, 1982). Parenthetically, Sec. 2 of

P.D. 1529 has eliminated the distinction between the

general jurisdiction of a Regional Trial Court and the

limited jurisdiction conferred upon it by the former law

when acting as a cadastral court (Ligon us. CA, et al.,

G.R. No. 107751, June 1, 1995). However, the holding

that such situations present only procedural, and not

jurisdictional, questions still applies.

20. Questions involving ownership of or title to real

property should be litigated in an ordinary civil action

or in the proceeding where the incident properly belongs,

before a court of general jurisdiction and not before a

land registration court (Santos vs. Aquino, L-32949,

Nov. 28, 1980).

21. Statutes regulating the procedure of the courts

will be construed as applicable to actions pending and

undetermined at the time of their passage, but not to

actions which have already become final and executory

(Borre, et al. us. CA, et al., G.R. No. 57204, Mar. 14,

1988). Procedural laws are retrospective in that sense

and to that extent (People vs. Sumilang, 77 Phil. 764;

Liam Law vs. Olympic Sawmill Co., et al., L-30771,

May 26, 1984; Yakult Philippines, et al. us. CA, et al.,

G.R. No. 91856, Oct. 5, 1990). Thus, the provision of

B.P. Blg. 129 which eliminated the need for a record on

appeal was given retroactive effect to authorize the giving

of due course to an appeal, which should have been

perfected in 1982 with the required record on appeal, by

relieving the appellant of the need therefor in line with

the change of procedure under B.P. Blg. 129 (Alday us.

Camilon, G.R. No. 60316, Jan. 31, 1983; Ouano vs. CA,

et al., L-44823, June 27, 1985; De Guzman, et al. us.

CA, et al., G.R. No. 52738, July 23, 1985; Lagunzad vs.

CA, et al., G.R. No. 52007, Sept. 24, 1987; Mun. Gov't of

17

REMEDIAL LAW COMPENDIUM

Coron vs. Carino, et al., G.R. No. 65896, Sept. 24, 1987;

Sarmiento vs. Gatmaitan, et al., L-38173, Nov. 12, 1987).

However, new court rules apply to pending cases

only with reference to proceedings therein which take

place after the date of their effectivity. They do not

apply to the extent that in the opinion of the court their

application would not be feasible or would work injustice,

in which event the former procedure shall apply. Thus,

where the application of the Rule on Summary Procedure

will mean the dismissal of the appeal of the party, the

same should not apply since, after all, the procedure

they availed of was also allowed under the Rules of

Court (Laguio, et al. vs. Gamet, et al., G.R. No. 74903,

Mar. 21, 1980).

22. Substantive law is that part of the law which

creates rights concerning life, liberty or property, or the

powers of instrumentalities for the administration of

public affairs (Primicias vs. Ocampo, 81 Phil. 650).

Procedural law refers to the adjective laws which prescribe

rules and forms of procedure in order that courts may be

able to administer justice (Lopez vs. Gloria, 40 Phil. 33).

Substantive law creates, defines and regulates rights,

as opposed to “adjective or remédial law” which prescribes

the method of enforcing the rights or obtaining redress

for their invasion (Black's Law Dictionary, 6th Ed.,

p. 1429; citations omitted).

Procedure is the mode of proceeding by which a legal

right is enforced, as distinguished from the law which

gives or defines the right, and which, by means of the

proceeding, the court is to administer. This term is com-

monly opposed to the sum of legal principles constituting

the substance of the law, and denotes the body of rules,

whether of practice or pleading, whereby rights are

effectuated through the successful application of the

Proper remedies (op. cit., pp. 1367-1368; id.).

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

In determining whether a rule prescribed by the

Supreme Court abridges, enlarges or modifies any

substantive right, the test is whether the rule really

regulates procedure, that is, the judicial process for

enforcing rights and duties recognized by the substantive

low and for justly administering remedy and redress for

a disregard or infraction of them. If the rule takes away

a vested right, it is not procedural. If the rule creates a

right, such as the right to appeal, it may be classified as

a substantive matter; but if it operates as a means of

implementing an existing right, then the rule deals

merely with procedure (Fabian vs. Desierto, etc., et al.,

G.R. No. 129742, Sept. 16, 1998).

It is, therefore, the nature and the purpose of the

law which determines whether it is substantive or

procedural, and not its place in the statute or its inclusion

in a code. Thus, for instance, Arts. 539 and 1674 of the

Civil Code and Sec. 85, R.A. 296 provided injunctive rules

in ejectment cases in the trial and appellate stages, but

these have been properly incorporated with modifications

as Secs. 8 and 9, respectively, of Rule 70 of the 1964

Rules of Court (now, Sec. 15 of revised Rule 70). These

subsequent amendatory provisions on injunctions were

proper since the mere fact that those provisions on in-

junctions were formerly included in a substantive statute

or code does not convert them into or detract from the

fact that they are procedural laws, contrary to common

misimpression. In fact, there are many such procedural

rules found in the Civil Code or, for that matter, in other

codes or basically substantive laws but they do not

thereby lose their character as procedural laws.

This matter is being clarified and emphasized here

in view of the Constitutional provision that the rules

which the Supreme Court is authorized to promulgate

shall not diminish, increase or modify substantive rights

(Sec. 5 [5], Art. VIH, 1987 Constitution). The improbable

position that a clearly procedural provision becomes a

19

REMEDIAL LAW COMPENDIUM

substantive law by the mere fact that it is included in a

compilation, codification or statutory enactment of

substantive rights, although only to indicate the

remedial complement for the enforcement thereof,

would effectively subvert the Constitutional intent and

diminish the scope and extent of the rule-making

power of the Supreme Court.

I. CIVIL PROCEDURE

A. PRELIMINARY CONSIDERATIONS

1. The study of civil procedure includes ordinary

civil actions, special civil actions and provisional

remedies. Special civil actions are governed by specific

and individual rules supplemented by the general

provisions on civil actions.

2. Definition of terms:

a. Cause of action: The delict or wrongful act or

omission committed by the defendant in violation of

the primary rights of the plaintiff (Racoma us. Fortich,

et al., L-29380, June 10, 1971).

b. Right of action: The remedial right or right to

relief granted by law to a party to institute an action

against a person who has committed a delict or wrong

against him.

The cause of action is the delict or wrong, while

the right of action is the right to sue as a consequence

of that delict. The question as to whether the plaintiff

has a cause of action is determined by the averments

in the pleading regarding the acts committed by the

defendant; whether such acts give him a right of action

is determined by the substantive law. There can be no

right of action without a cause of action being first

established (see Espafol vs. The Chairman, etc. of the

PVA, L-44616, June 29, 1985).

A right of action is the right to presently enforce a

cause of action — a remedial right affording redress

for the infringement of a legal right belonging to some

definite person; a cause of action consists of the operative

facts which give rise to such right of action. The right

of action does not arise until the performance of all

conditions precedent to the action, and may be taken

away by the running of the statute of limitations,

21

REMEDIAL LAW COMPENDIUM

through an estoppel, or by other circumstances which do

not affect the cause of action. There may be several

rights of action and one cause of action, and rights may

accrue at different times from the same cause (1 Am Jur 2d,

Sec. 2, p. 541).

c. Relief: The redress, protection, award or coercive

measure which the plaintiff prays the court to render in

his favor as a consequence of the delict committed by the

defendant.

d. Remedy: The procedure or type of action which

may be availed of by the plaintiff as the means to obtain

the relief desired.

e. Subject-matter: The thing, wrongful act, con-

tract or property which is directly involved in the action,

concerning which the wrong has been done and with

respect to which the controversy has arisen (Yusingco,

et al. us, Ong Hing Lian, L-26523, Dec. 24, 1971).

Thus, in a case for breach of contract, the contract

violated is the subject-matter; the breach by the obligor

is the cause of action; the right of action is the consequent

substantive right on the part of the obligee to sue for

redress; the relief is the damages or rescission or the act

which the plaintiff asks the court to order; and the remedy

is the type of action which may be availed of by the

plaintiff, which may be an action either for damages,

for rescission or for specific performance.

The subject-matter of a given case is determined not

by the nature of the action that a party is entitled to

bring but by the nature and character of the pleadings

and issues submitted by the parties (Viray us. CA, et al.,

G.R. No. 92481, Nov. 9, 1990).

3. Classification of actions:

a. Real action: One brought for the protection of

real rights, land, tenements or hereditaments or one

founded on privity of estate only (Paper Industries Corp.

22

PRELIMINARY CONSIDERATIONS

of the Phil. vs. Samson, et al., L-80175, Nov. 28, 1975).

Example: Accion reivindicatoria.

Personal action. One which is not founded upon the

privity of real rights or real property. Example: Action

for a sum of money.

Mixed action. One brought for protection or recovery

of real property and also for an award for damages

sustained. Example: Accion publiciana with a claim for

damages.

For purposes of venue, a mixed action is governed

by the rules of venue in real actions.

b. Action in rem: One which is not directed only

against particular persons but against the thing itself

and the object of which is to bar indifferently all who

might be minded to make any objection against the right

sought to be enforced, hence the judgment therein is

binding theoretically upon the whole world. Example:

Expropriation.

Action in personam: One which is directed against

particular persons on the basis of their personal liability

to establish a claim against them and the judgment

wherein is binding only upon the parties impleaded or

their successors in interest. Example: Action for breach

of contract.

Action quasi in rem: One directed against particular

persons but the purpose of which is to bar and bind not

only said persons but any other person who claims any

interest in the property or right subject of the suit.

Example: Judicial foreclosure of a mortgage (Ocampo

vs. Domalanta, L-21011, Aug. 30, 1967).

A proceeding for attachment of property is in remif

the defendant does not appear in court, and in personam

if he appears (Banco Espanol-Filipino vs. Palanca,

supra).

23

REMEDIAL LAW COMPENDIUM

c. Transitory action. One the venue of which is

dependent generally upon the residence of the parties

regardless of where the cause of action arose. Example.

Personal action.

Local action: One which is required by the Rules to

be instituted in a particular place in the absence of an

agreement to the contrary. Example: Real action.

The classification of actions into real, personal

or mixed is based on the subject-matter thereof. With

respect to the binding effect of the relief sought or the

judgment therein, actions are classified into actions in

rem, quasi in rem or in personam. Hence, a real action

may be in personam, or a personal action may be in rem

(see Hernandez, et al. vs. Rural Bank of Lucena, Inc.,

L-29791, Jan. 10, 1978). Transitory or local actions are

so denominated on the basis of the permissible venues

thereof.

4. In Yu us. Pacleb, etc. (G.R. No. 172172, Feb. 24,

2009), the Supreme Court cited this extended discussion

on classification of civil action: The settled rule is that the

aim and object of an action determine its character.

Whether a proceeding is rem, or in personam, or quasi in

rem is determined by its nature-and purpose, and by these

only. A proceeding in personam is a proceeding t~ enforce

personal rights and obligations brought against the person

and is based on the jurisdiction of the person, although it

may involve his right to, or the exercise of ownership of,

specific property, or seek to compel him to control or dispose

of it in accordance with the mandate of the court. The

purpose of a proceeding in personam is to impose, through

the judgment of a court, some responsibility or liability to

compel a defendant to specifically perform some act or

actions to fasten a pecuniary liability on him. An action

in personam is said to be one which has for its object a

judgment against the person, as distinguished from a

judgment against the property to determine its state. It

24

PRELIMINARY CONSIDERATIONS

has been held that an action in personam is a proceeding

to enforce personal rights or obligations, such action is

brought against the person.

x x x

On the other hand, a proceeding quasi in rem is one

brought against persons seeking to subject the property

of such persons to the discharge of the claims assailed. In

an action quasi in rem, an individual is named as

defendant and the purpose of the proceeding is to subject

his interests therein to the obligations or loans burdening

the property. Actions quasi in rem deal with the status,

ownership or liability of a particular property but which

are intended to operate on these questions only as between

particular parties to the proceedings and not to ascertain

or cut off the rights or interests of all possible claimants.

The judgments therein are binding only upon the parties

who joined in the action.

26

B. JURISDICTION OF THE SUPREME COURT

UNDER THE 1987 CONSTITUTION

Article VI (Legislative Department)

“Sec. 30. No law shall be passed increasing the

appellate jurisdiction of the Supreme Court as

provided in this Constitution without its advice and

concurrence.”

Article VII (Executive Department)

“Sec. 4, (last par.) The Supreme Court, sitting en

banc, shall be the sole judge of all contests relating to

the election, returns and qualifications of the President

or Vice-President, and may promulgate rules for the

purpose.”

x x Xx

“Sec. 18. (third par.) The Supreme Court may

review, in an appropriate proceeding filed by any citizen,

the sufficiency of the factual basis of the proclamation of

martial law or the suspension of the privilege of the writ

or the extension thereof, and must promulgate its decision

thereon within thirty days from its filing.”

Article VIII (Judicial Department)

“Sec. 2. The Congress shall have the power to define,

prescribe, and apportion the jurisdiction of the various

courts but may not deprive the Supreme Court of its

jurisdiction over cases enumerated in Section 5 hereof.

No law shall be passed reorganizing the Judiciary

when it undermines the security of tenure of its

Members.”

x x Xx

“Sec. 5. The Supreme Court shall have the following

powers:

26

qd)

(2)

(3)

(4)

(5)

JURISDICTION OF THE SUPREME COURT

UNDER THE 1987 CONSTITUTION

Exercise original jurisdiction over cases affecting

ambassadors, other public ministers and consuls, and

over petitions for certiorari, prohibition, mandamus,

quo warranto, and habeas corpus.

Review, revise, reverse, modify, or affirm on appeal

or certiorari, as the law or the Rules of Court may

provide, final judgments and orders of lower courts

in:

(a) All cases in which the constitutionality or

validity of any treaty, international or exe-

cutive agreement, law, presidential decree,

proclamation, order, instruction, ordinance, or

regulation is in question.

(b) All cases involving the legality of any tax, impost,

assessment, or toll, or any penalty imposed in

relation thereto.

(c) All cases in which the jurisdiction of any lower

court is in issue.

(d) All criminal cases in which the penalty imposed

is reclusion perpetua or higher.

(e) All cases in which only an error or question of

law is involved.

Assign temporarily judges of lower courts to other

stations as public interest may require. Such

temporary assignment shall not exceed six months

without the consent of the judge concerned.

Order a change of venue or place of trial to avoid a

miscarriage of justice.

Promulgate rules concerning the protection and

enforcement of constitutional rights, pleading,

practice, and procedure in all courts, the admission

to the practice of law, the Integrated Bar, and legal

assistance to the underprivileged. Such rules shall

provide a simplified and inexpensive procedure for

27

REMEDIAL LAW COMPENDIUM

the speedy disposition of cases, shall be uniform for

all courts of the same grade, and shall not diminish,

increase, or modify substantive rights. Rules of

procedure of special courts and quasi-judicial bodies

shall remain effective unless disapproved by the

Supreme Court.

(6) Appoint all officials and employees of the Judiciary

in accordance with the Civil Service Law.”

Article IX (Constitutional Commissions)

A. Common Provisions

“Sec. 7. Each Commission shall decide by a majority

vote of all its Members any case or matter brought before

it within sixty days from the date of its submission for

decision or resolution. A case or matter is deemed

submitted for decision or resolution upon the filing of

the last pleading, brief, or memorandum required by

the rules of the Commission or by the Commission itself.

Unless otherwise provided by this Constitution or by law,

any decision, order or ruling of each Commission may be

brought to the Supreme Court on certiorari by the

aggrieved party within thirty days from receipt of a

copy thereof.” .

NOTES

1. See, in this connection, the notes under Sec. 7,

Rule 56.

2. Considering the provisions of B.P. Blg. 129, the

fact that appeals from the Securities and Exchange

Commission and in naturalization and denaturalization

cases should now be taken to the Court of Appeals, and

all decisions of the constitutional commissions are

reviewable on original actions of certiorari, all appeals

in civil cases to the Supreme Court can now be brought

only on petition for review on certiorari (cf. Sec. 17,

28

JURISDICTION OF THE SUPREME COURT

UNDER THE 1987 CONSTITUTION

R.A. 296, as amended by R.A. 5440; Santos, et al. vs.

CA, et al., G.R. No. 56614, July 28, 1987). Moreover, as

hereafter explained, Sec. 9 of B.P. Blg. 129 was amended

by R.A. 7902 to further vest appellate jurisdiction in the

Court of Appeals over judgments, final orders, awards or

resolutions of the Civil Service Commission and the

Central Board of Assessment Appeals.

C. THE JUDICIARY REORGANIZATION ACT

OF 1980

ORGANIZATION

1. The Judiciary Reorganization Act of 1980 (Batas

Pambansa Blg. 129) took effect upon its approval on

August 14, 1981 (Sec. 48). However, the transitory pro-

vision (Sec. 44) declared that its provisions “shall

immediately be carried out in accordance with an

Executive Order to be issued by the President. The

Court of Appeals, the Courts of First Instance, the

Circuit Criminal Courts, the Juvenile and Domestic

Relations Courts, the Courts of Agrarian Relations, the

City Courts, the Municipal Courts and the Municipal

Circuit Courts shall continue to function as presently

constituted and organized until the completion of the

reorganization provided in this Act as declared by the

President. Upon such declaration, the said courts shall

be deemed automatically abolished and the incumbents

thereof shall cease to hold office. The cases pending in

the old Courts shall be transferred to the appropriate

Courts constituted pursuant to this Act, together with

the pertinent functions, records, equipment, property

and the necessary personnel.” The constitutionality of

this Act was upheld by the Supreme Court en banc,

with one dissent, in De la Llana, et al. us. Alba, et al.

(G.R. No. 57883, Mar. 12, 1982).

2. The Court of Appeals was replaced by the

Intermediate Appellate Court consisting of a Presiding

Justice and 49 Associate Appellate Justices, which shall

sit in 10 divisions each composed of 5 members, except

only for the purpose of exercising administrative,

ceremonial or other non-adjudicatory functions in which

instances it may sit en banc (Secs. 3 and 4).

30

JUDICIARY REORGANIZATION ACT OF 1980

However, under Executive Order No. 33 (July 28, 1986),

amending B.P. Blg. 129, the Court of Appeals was

re-created, consisting of a Presiding Justice and 50

Associate Justices, which shall exercise its powers,

functions and duties through 17 divisions, each composed

of 3 members. It may sit en banc for the purpose of

exercising administrative, ceremonial or other non-

adjudicatory functions (Secs. 3 and 4, as amended).

A majority of the actual members of the Court shall

constitute a quorum for its sessions en banc. Three (3)

members shall constitute a quorum for the sessions of a

division. The unanimous vote of the three members ofa

division shall be necessary for the pronouncement of a

decision or final resolution, which shall be reached in

consultation before the writing of the opinion by any

member of the division. In the event that the three

members do not reach a unanimous vote, the Presiding

Justice shall request the Raffle Committee of the Court

for the designation of two additional Justices to sit

temporarily with them, forming a special division of five

members and the concurrence of a majority of such

division shall be necessary for the pronouncement of a

decision or final resolution. The designation of such

additional Justices shall be made strictly by raffle

(Sec. 11, as amended).

Executive Order No. 33 repealed Sec. 8 of B.P.

Blg. 129 which had provided for grouping of divisions

to handle specific classes of cases (Sec. 4). It further

provided that the term “Intermediate Appellate Court,

Presiding Appellate Justice and Associate Appellate

Justice(s)” used in B.P. Blg. 129 or in any other law or

executive order shall hereafter mean Court of Appeals,

Presiding Justice and Associate Justice(s), respectively

(Sec. 8).

Additionally, effective February 2, 1997, B.P. Ble. 129

was further amended by R.A. 8246 (Appendix G),

pursuant to which the Court of Appeals shall consist of

31

REMEDIAL LAW COMPENDIUM

a Presiding Justice and 68 Associate Justices, and shall

be composed of 23 divisions of 3 members each, with the

first 17 divisions stationed in Manila, the 18th to 20th

divisions in Cebu City, and the 21st to 23rd divisions in

Cagayan de Oro City.

3. The Courts of First Instance, the Circuit Criminal

Courts, the Juvenile and Domestic Relations Courts and

the Courts of Agrarian Relations have been integrated

into the Regional Trial Courts for each of the 13 Judicial

Regions which replaced the former 16 Judicial Districts,

each Regional Trial Court to consist of the number of

branches provided in Section 14 of the Act.

4. The city courts and municipal courts in the

National Capital Judicial Region have been merged into

a Metropolitan Trial Court of Metro Manila and were

converted into branches thereof (Sec. 27). The Supreme

Court shall constitute other Metropolitan Trial Courts

in such other metropolitan areas as may be established

by law and whose territorial jurisdiction shall be co-

extensive with the cities and municipalities comprising

such metropolitan area (Sec. 28).

5. The city courts in other cities which do not now

or hereafter form part of a metropolitan area shall be

known as Municipal Trial Courts, with the corresponding

number of branches (Sec. 29), and the municipal courts,

whether of an ordinary municipality or of a capital of a

province or sub-province but not comprised within a

metropolitan area and a municipal circuit, shall likewise

be known as Municipal Trial Courts with the corre-

sponding number of branches (Sec. 30). The municipal

circuit courts shall be known as Municipal Circuit Trial

Courts and the Supreme Court may further reorganize

the same (Sec. 31).

6. Excepted from the coverage of the Act are the

Supreme Court and the Sandiganbayan, but these

32

JUDICIARY REORGANIZATION ACT OF 1980

courts have been affected by the jurisdictional changes

introduced therein. The provisions of the Judiciary Act

of 1948 (R.A. 296, as amended), R.A. 5179, as amended,

the Rules of Court and all other statutes, letters of

instructions and general orders or parts thereof,

inconsistent with the provisions of this Act are repealed

or modified accordingly.

7. No mention is made of the Court of Tax Appeals

since the Act is basically on the matter of jurisdictional

changes. However, appeals from its judgments or final

orders, which used to be governed by R.A. 1125, were later

required to be taken to the Court of Appeals pursuant to

Revised Administrative Circular No. 1-95 of the Supreme

Court, which thereafter was adopted as Rule 43 of these

revised Rules. See, however, the more recent changes in

R.A. 9282 (Appendix CC).

JURISDICTION

I. Intermediate Appellate Court (now, the Court of

Appeals):

“Sec. 9. Jurisdiction. — The Intermediate Appellate

Court shall exercise:

(1) Original jurisdiction to issue writs of man-

damus, prohibition, certiorari, habeas corpus, and quo

warranto, and auxiliary writs or processes, whether

or not in aid of its appellate jurisdiction;

(2) Exclusive original jurisdiction over actions

for annulment of judgments of Regional Trial Courts;

and

(3) Exclusive appellate jurisdiction over all final

judgments, decisions, resolutions, orders or awards

of Regional Trial Courts and quasi-judicial agencies,

instrumentalities, boards, or commissions, except

those falling within the appellate jurisdiction of the

Supreme Court in accordance with the Constitution,

33

REMEDIAL LAW COMPENDIUM

the provisions of this Act, and of subparagraph (1) of

the third paragraph and subparagraph (4) of the

fourth paragraph of Section 17 of the Judiciary Act

of 1948.

The Intermediate Appellate Court shall have the

power to try cases and conduct hearings, receive

evidence and perform any and all acts necessary to

resolve factual issues raised in cases falling within

its original and appellate jurisdiction, including the

power to grant and conduct new trials and further

proceedings.

These provisions shall not apply to decisions and

interlocutory orders issued under the Labor Code

of the Philippines and by the Central Board of

Assessment Appeals.”

The second paragraph of Sec. 9 above set forth was

subsequently amended by Sec. 5 of Executive Order

No. 33 to read as follows:

“The Court of Appeals shall have the power to

receive evidence and perform any and all acts

necessary to resolve factual issues raised in (a) cases

falling within its original jurisdiction, such as actions

for annulment of judgments of regional trial courts,

as provided in paragraph (2) hereof; and in (b) cases

falling within its appellate jurisdiction wherein a

motion for new trial based only on the ground of

newly discovered evidence is granted by it.”

However, effective March 18, 1995, Sec. 9 was further

amended by R.A. 7902 (Appendix F) and now provides:

“SEC. 9. Jurisdiction. — The Court of Appeals

shall exercise:

“(1) Original jurisdiction to issue writs of man-

damus, prohibition, certiorari, habeas corpus, and quo

warranto, and auxiliary writs or processes, whether

or not in aid of its appellate jurisdiction;

34

JUDICIARY REORGANIZATION ACT OF 1980

“(2) Exclusive original jurisdiction over actions

for annulment of judgments of Regional Trial Courts;

and

“(3) Exclusive appellate jurisdiction over all final

judgments, decisions, resolutions, orders or awards

of Regional Trial Courts and quasi-judicial agencies,

instrumentalities, boards or commissions, including

the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Social

Security Commission, the Employees Compensation

Commission and the Civil Service Commission, except

those falling within the appellate jurisdiction of the

Supreme Court in accordance with the Constitution,

the Labor Code of the Philippines under Presidential

Decree No. 442, as amended, the provisions of this

Act, and of subparagraph (1) of the third paragraph

and subparagraph (4) of the fourth paragraph of

Section 17 of the Judiciary Act of 1948.

“The Court of Appeals shall have the power to

try cases and conduct hearings, receive evidence and

perform any and all acts necessary to resolve factual

issues raised in cases falling within its original and

appellate jurisdiction, including the power to grant

and conduct new trials or further proceedings. Trials

or hearings in the Court of Appeals must be con-

tinuous and must be completed within three (3)

months unless extended by the Chief Justice.”

NOTES

1. Unlike the provisions of Sec. 30 of the Judiciary

Act, B.P. Blg. 129 vested the Intermediate Appellate

Court with original jurisdiction to issue writs of man-

damus, prohibition, certiorari, habeas corpus, and all other

auxiliary writs and processes whether or not in aid of its

appellate jurisdiction and added the special civil action of

quo warranto to such original jurisdiction. Furthermore,

the Intermediate Appellate Court had exclusive original

36

REMEDIAL LAW COMPENDIUM

jurisdiction over actions for the annulment of judgments

of the Regional Trial Courts. The latter, however, retain

their jurisdiction over actions for the annulment of

judgments of the inferior courts (Sec. 19), i.e., the

Metropolitan, Municipal and Municipal Circuit Trial

Courts (Sec. 25).

2. Amendatory of previous legislation, the appellate

jurisdiction of the then Intermediate Appellate Court over

quasi-judicial agencies, or the so-called administrative

tribunals, was extended to and included the Securities

and Exchange Commission and the different boards

which took the place of the quondam Public Service

Commission, i.e., the Boards of Transportation, Commu-

nications, and Power and Waterworks, whose decisions

were theretofore appealable to the Supreme Court. Cases

involving petitions for naturalization and denaturalization

are now exclusively appealable to the Court of Appeals.

3. However, by specific provisions of Sec. 9 of this

Act, the Supreme Court retained exclusive appellate

jurisdiction over the decisions of the two constitutional

commissions, i.e., Commission on Elections and Com-

mission on Audit (see 1973 Constitution, Art. XII-C and

D). Under the 1987 Constitution, this exclusive appellate

jurisdiction was made to include the Civil Service

Commission (Sec. 7, Art. IX-A). Also, likewise specifically

excluded from the appellate jurisdiction of the Interme-

diate Appellate Court were decisions and interlocutory

orders under the Labor Code, such as those promulgated

by the Secretary of Labor and Employment and the

National Labor Relations Commission, those of the Central

Board of Assessment Appeals, and the 5 types of cases

which fall within the exclusive appellate jurisdiction of

the Supreme Court under the 1973 Constitution (Sec. 5/2],

Art. X) and reproduced in the 1987 Constitution

(Sec. 5[2], Art. VIII), as amplified in the provisions of the

Judiciary Act specified by said Sec. 9.

36

JUDICIARY REORGANIZATION ACT OF 1980

Furthermore, in view of the exclusionary provision

in said Sec. 9, the Intermediate Appellate Court appeared

to have no appellate jurisdiction over the cases in the

specified paragraphs of Sec. 17 of the Judiciary Act, i.e.,

those involving constitutional, tax or jurisdictional

questions even if the same also involve questions of fact

or mixed questions of fact and law which were appealable

to the Court of Appeals under Sec. 17 of the Judiciary

Act, as amended. It is believed that despite the present

formulation of said Sec. 9(3) of B.P. Blg. 129, the former

rule, vesting the Court of Appeals with appellate juris-

diction in the aforestated cases whenever a factual issue

is involved, should still apply.

As indicated earlier, with the amendments introduced

by R.A. 7902, the dispositions of the Civil Service Com-

mission and the Central Board of Assessment Appeals

are now within the exclusive appellate jurisdiction of the

Court of Appeals.

4. While the Intermediate Appellate Court was

authorized to receive evidence on factual issues on appeal,

this evidentiary hearing contemplates “incidental facts”

which were not touched upon or fully heard by the trial

court, and not an original and full trial of the main

factual issue which properly pertains to the trial court

(Lingner & Fisher GMBH vs. IAC, et al., G.R. No. 63557,

Oct. 28, 1983). This power to conduct new trials or

further proceedings is not obligatory on the appellate

court and it may remand the case to the trial court

for that purpose (De la Cruz, etc. us. IAC, et al., G.R.

No. 72981, Jan. 29, 1988).

5. The exclusive appellate jurisdiction of the Court

of Appeals provided for in Sec. 9(3) of B.P. Blg. 129 over

final orders or rulings of quasi-judicial instrumentalities,

boards or commissions refers to those which resulted from

proceedings wherein the administrative body involved

exercised quasi-judicial functions. Such quasi-judicial

37

REMEDIAL LAW COMPENDIUM

action or discretion involves the investigation of facts,

holding of hearings, drawing conclusions therefrom as a

basis for official action, and exercising discretion of a

judicial nature. Quasi-judicial adjudication requires a

determination of rights, privileges and duties resulting

in a decision or order which applies to a specific situation.

Rules and regulations of general applicability issued by

the administrative body to implement its purely adminis-

trative policies and functions, or those which are merely

incidents of its inherent administrative functions, are

not included in the appealable orders contemplated in

said provision, unless otherwise specifically provided by

other laws governing the matter. Controversies arising

from such orders are within the cognizance of the

Regional Trial Courts (Lupangco, et al. us. CA, et al.,

G.R. No. 77372, April 29, 1988).

6. It was formerly held that the 30-day period to

appeal to the Intermediate Appellate Court from a

decision or final order of the Securities and Exchange

Commission, pursuant to its rules issued consequent

to Sec. 6, P.D. 902-A, had not been affected by B.P.

Blg. 129 which provides for a 15-day appeal period

from decisions of courts of justice. The Securities and

Exchange Commission is not a court; it is an adminis-

trative agency. Repeals by implication are not favored

(Gimenez Stockbrokerage & Co., Inc. us. SEC, et al.,

G.R. No. 68568, Dec. 26, 1984).

7. The aforesaid doctrine was taken into account by

the Supreme Court in an appeal from a decision of the

Insurance Commission to the then Intermediate Appellate

Court since Sec. 416(7) of the Insurance Code (P.D. 612,

as amended) provides for a 30-day period for appeal from

notice of a final order,.ruling, or decision of the Com-

mission. The Supreme Court noted that if the provisions

of R.A. 5434 were to be applied, pursuant to Par. 22(c) of

the Interim Rules which governs appeals from quasi-

38

JUDICIARY REORGANIZATION ACT OF 1980

judicial bodies, Sec. 2 thereof provides that the appeal

should be filed within 15 days from notice of the ruling,

award, order, decision, or judgment or from the date of

its last publication if required by law, or in case a motion

for reconsideration is filed within the period for appeal,

then within 10 days from notice or such publication of

the resolution denying the motion for reconsideration.

Nevertheless, in line with the ruling in Gimenez, since

the Insurance Commission is likewise an administrative

body, appeals from its final orders, decisions, resolutions,

or awards may not necessarily be deemed modified by

Sec. 39 of B.P. Blg. 129 which limits the period to

appeal to 15 days (Midland Ins. Corp. us. IAC, et al.,

G.R. No. 71905, Aug. 13, 1986; see also Zenith Ins. Corp.

us. IAC, et al., G.R. No. 73336, Sept. 24, 1986; Malayan

Ins. Co., Inc. vs. Arnaldo, et al., G.R. No. 67835, Oct. 12,

1987).

8. The foregoing doctrines, however, are no longer

controlling in view of Circular No. 1-91 issued by the

Supreme Court on February 27, 1991 which provided

that appeals from quasi-judicial agencies shall be taken

to the Court of Appeals within 15 days from notice or last

publication of the judgment or final order. This was

more recently further amplified by Revised Adminis-

trative Circular No. 1-95 which took effect on June 1,

1995, and has now been formulated as Rule 43 of these

revised Rules.

9. It will also be recalled that appeals from the

decisions, orders or rulings of the three constitutional

commissions, i.e., Civil Service Commission, Commission

on Elections and Commission on Audit, may be brought to

the Supreme Court on certiorari within 30 days from

receipt thereof unless otherwise provided by the Consti-

tution or by law (Sec. 7, Art. IX-A, 1987 Constitution).

However, as earlier stated, Sec. 9 of B.P. Blg. 129 which

originally contained the same jurisdictional rule was

subsequently amended by R.A. 7902, effective March 18,

39

REMEDIAL LAW COMPENDIUM

1995, to provide that appeals from the Civil Service

Commission should be taken to the Court of Appeals.

10. In the landmark decision in St. Martin Funeral

Home vs. NLRC, et al. (G.R. No. 130866, Sept. 16, 1998),

the Supreme Court clarified that ever since appeals from

the NLRC to the Supreme Court were eliminated, the

legislative intendment is that the special civil action of

certiorari was and still is the proper vehicle for judicial

review of decisions of the NLRC. All references in the

amended Sec. 9 of B.P. Blg. 129 to supposed appeals from

the NLRC to the Supreme Court are interpreted and

declared to mean and refer to petitions under Rule 65.

Consequently, all such petitions should be initially filed

in the Court of Appeals in strict observance of the rule on

hierarchy of courts. The concurrent original jurisdiction

of the Supreme Court can be availed of only under

compelling and exceptional circumstances.

“11. On a different rationale, the Supreme Court

ruled in Fabian vs. Desierto, etc., et al. (G.R. No. 129742,

Sept. 16, 1998) that appeals from the Office of the

Ombudsman in administrative disciplinary cases should

be taken to the Court of Appeals via a verified petition for

review under Rule 43. Striking down as unconstitutional

Sec. 27, R.A. 6770 (Ombudsman Act of 1989) which

authorized such appeal to the Supreme Court “in

accordance with Rule 45,” it was pointed out that

appeals under Rule 45 apply only to judgments or final

orders of the courts enumerated under Sec. 1 thereof, and

not to those of quasi-judicial agencies. Furthermore, that

provision of R.A. 6770 violates the proscription in Sec. 30,

Art. VI of the 1987 Constitution against a law which

increases the appellate jurisdiction of the Supreme Court

without its advice and consent.

II. Regional Trial Courts:

“SEC. 19. Jurisdiction in civil cases. — Regional

40

JUDICIARY REORGANIZATION ACT OF 1980

Trial Courts shall exercise exclusive original jurisdiction:

(1) In all civil actions in which the subject of the

litigation is incapable of pecuniary estimation;

(2) In all civil actions which involve the title

to, or possession of, real property, or any interest

therein, where the assessed value of the property

involved exceeds Twenty thousand pesos (P20,000.00)

or, for civil actions in Metro Manila, where such value

exceeds Fifty thousand pesos (P50,000.00) except

actions for forcible entry into and unlawful detainer