Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Bobo2013 PDF

Bobo2013 PDF

Uploaded by

Merari Lugo OcañaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Bobo2013 PDF

Bobo2013 PDF

Uploaded by

Merari Lugo OcañaCopyright:

Available Formats

Research

Original Investigation

Antipsychotics and the Risk of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

in Children and Youth

William V. Bobo, MD, MPH; William O. Cooper, MD, MPH; C. Michael Stein, MB, ChB; Mark Olfson, MD, MPH;

David Graham, MD, MPH; James Daugherty, MS; D. Catherine Fuchs, MD; Wayne A. Ray, PhD

Supplemental content at

IMPORTANCE The increased prescribing of antipsychotics for children and youth has jamapsychiatry.com

heightened concerns that this practice increases the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus.

OBJECTIVE To compare the risk of type 2 diabetes in children and youth 6 to 24 years of age

for recent initiators of antipsychotic drugs vs propensity score–matched controls who had

recently initiated another psychotropic medication.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS Retrospective cohort study of the Tennessee Medicaid

program with 28 858 recent initiators of antipsychotic drugs and 14 429 matched controls.

The cohort excluded patients who previously received a diagnosis of diabetes, schizophrenia,

or some other condition for which antipsychotics are the only generally recognized therapy.

Author Affiliations: Department of

Psychiatry, Vanderbilt University

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES Newly diagnosed diabetes during follow-up, as identified School of Medicine, Nashville,

from diagnoses and diabetes medication prescriptions. Tennessee (Bobo, Fuchs);

Department of Pediatrics, Vanderbilt

University School of Medicine,

RESULTS Users of antipsychotics had a 3-fold increased risk for type 2 diabetes (HR = 3.03 Nashville, Tennessee (Cooper);

[95% CI = 1.73-5.32]), which was apparent within the first year of follow-up (HR = 2.49 [95% Division of Clinical Pharmacology,

CI = 1.27-4.88]). The risk increased with cumulative dose during follow-up, with HRs of 2.13 Department of Internal Medicine,

Vanderbilt University School of

(95% CI = 1.06-4.27), 3.42 (95% CI = 1.88-6.24), and 5.43 (95% CI = 2.34-12.61) for

Medicine, Nashville, Tennessee

respective cumulative doses (gram equivalents of chlorpromazine) of more than 5 g, 5 to 99 (Stein); Department of Psychiatry,

g, and 100 g or more (P < .04). The risk remained elevated for up to 1 year following Columbia University College of

discontinuation of antipsychotic use (HR = 2.57 [95% CI = 1.34-4.91]). When the cohort was Physicians and Surgeons, New York,

New York (Olfson); US Food and Drug

restricted to children 6 to 17 years of age, antipsychotic users had more than a 3-fold Administration, Silver Spring,

increased risk of type 2 diabetes (HR = 3.14 [95% CI = 1.50-6.56]), and the risk increased Maryland (Graham); Division of

significantly with increasing cumulative dose (P < .03). The risk was increased for use Pharmacoepidemiology, Department

restricted to atypical antipsychotics (HR = 2.89 [95% CI = 1.64-5.10]) or to risperidone of Preventive Medicine, Vanderbilt

University School of Medicine,

(HR = 2.20 [95% CI = 1.14-4.26]). Nashville, Tennessee (Daugherty,

Ray).

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE Children and youth prescribed antipsychotics had an Corresponding Author: Wayne A.

increased risk of type 2 diabetes that increased with cumulative dose. Ray, PhD, Division of

Pharmacoepidemiology, Department

of Preventive Medicine, Vanderbilt

JAMA Psychiatry. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2053 University School of Medicine, 1500

Published online August 21, 2013. 21st Ave S, Ste 2600, Nashville, TN

37212 (wayne.ray@vanderbilt.edu).

I

ncreasing antipsychotic use among children and youth1-4 antipsychotic use might increase the risk of type 2 diabetes,12,13

raises the concern that this practice increases the risk of type epidemiologic data are more limited.5-7 Obstacles to studies of

2 diabetes mellitus in this vulnerable population.5-7 For this population include the lower incidence of type 2 diabe-

adults, there is considerable evidence linking antipsychotic use tes, the need to distinguish between type 1 and type 2 diabe-

to increased risk of type 2 diabetes. Several antipsychotics have tes, and the identification of appropriate comparison groups.

metabolic effects, such as weight gain, increased glucose level, Prior to the introduction of the atypical antipsychotic

and insulin resistance, that are thought to be precursors to drugs, the primary indications for antipsychotics in pediatric

diabetes. 8 Epidemiologic studies have confirmed an in- or adolescent populations were schizophrenia and other psy-

creased risk for type 2 diabetes for individuals using some types chotic disorders. Subsequently, use expanded to include bi-

of antipsychotics, particularly the atypical antipsychotic polar disorders, affective disorders, and symptoms related to

drugs.9-11 However, the evidence for children and youth is less behavior and conduct, which now account for the majority of

extensive. Although metabolic studies of children suggest that prescriptions.2-4,14 There are other well-recognized alterna-

jamapsychiatry.com JAMA Psychiatry Published online August 21, 2013 E1

Downloaded From: http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/ by a Oakland University User on 08/22/2013

Research Original Investigation Antipsychotics and the Risk of Type 2 Diabetes

tive medications for each of these conditions; indeed, anti- qualifying use of antipsychotics in the 90 days preceding the

psychotics are often a secondary or off-label therapeutic qualifying prescription (allowed inclusion of patients start-

choice.14-17 Thus, an increased risk of diabetes conferred by an- ing an antipsychotic shortly before meeting cohort eligibility

tipsychotic medications would be an important component of criteria) but had to have a prior period of 365 days free of an-

risk-benefit evaluation. tipsychotic use. The cohort was restricted to recent users to

To better define the relationship between antipsychotic use include cases of diabetes that occurred early in therapy and

and newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes among children and to ensure that baseline covariates were unaffected by chronic

youth, we conducted a retrospective cohort study of the Ten- antipsychotic effects.19

nessee Medicaid program. The cohort included recent initia- We excluded patients with diagnosed conditions for which

tors of antipsychotics who had received no diagnosis for which antipsychotics generally are the only recommended treat-

antipsychotics were generally the only recognized pharmaco- ment. These included schizophrenia or related psychoses, or-

therapy and a propensity score–matched control group of re- ganic psychoses, autism, mental retardation, Tourette syn-

cent initiators of other psychotropic medications. drome, or other tic disorders. We also excluded patients

prescribed clozapine or long-acting injectable preparations—

usually indicators of schizophrenia or related psychoses—as

well as those with parenterally administered drugs, typically

Methods given for transient agitation.

Sources of Data

Study data were obtained from the computerized files of the Controls

Tennessee Medicaid program, augmented with linkage to a Potential controls were recent initiators of other psychotro-

statewide hospital discharge database and computerized birth pic drugs, defined as for antipsychotics, with no antipsy-

certificates.18,19 Study files (enrollment, pharmacy, hospital, chotic use in the 365 days preceding the qualifying prescrip-

outpatient, nursing home, and linked death certificates) al- tion. Control drugs included mood stabilizers (lithium or

lowed for the identification of the study cohort, the classifi- anticonvulsant mood stabilizers [absent evidence of a neuro-

cation of baseline comorbidity, the tracking of medication use, logic indication]), antidepressants with a psychiatric diagno-

and the ascertainment of diabetes. sis, psychostimulants, α-agonists with diagnosed attention-

Antipsychotics and other study medications were identi- deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or other problems of

fied from Medicaid pharmacy files. These included the date behavior/conduct, and benzodiazepines with a psychiatric di-

that the prescription was dispensed, drug name, quantity, dose, agnosis (eAppendix and eTable 3 in Supplement).

and days of supply. Computerized pharmacy records are an ex- From the pool of potential controls, we calculated the pro-

cellent source of medication data because they are not sub- pensity scores,24 the conditional probability of being an anti-

ject to information bias19 and have a high level of concor- psychotic user, given the study covariates. These were fac-

dance with patient self-reports of medication use.20-22 Residual tors that might be directly or indirectly related to both

misclassification should be limited and, if nondifferential, antipsychotic use and the development of type 2 diabetes (eAp-

should bias toward the null.18 pendix and eTable 4 in Supplement). The 115 covariates in-

cluded demographic characteristics, psychiatric diagnoses and

Antipsychotic Users medications, metabolic disorders and related conditions (eg,

The study population included children and youth 6 to 24 years diagnosed obesity), obstetric-gynecologic conditions (eg, ab-

of age enrolled in Medicaid for at least 1 year between Janu- sent/irregular menstruation), cardiovascular disease (eg, hy-

ary 1, 1996, and December 31, 2007. The lower age limit is the pertension), respiratory disorders (eg, sleep apnea), muscu-

youngest age for which there are material numbers of case re- loskeletal symptoms (eg, joint pain), other somatic conditions,

ports of type 2 diabetes; the upper age limit corresponds to the and intensity of health care utilization (medical surveillance)

World Health Organization's definition of youth.23 Cohort eli- for both psychiatric and somatic comorbidity. The estimation

gibility (eAppendix and eTables 1 and 2 in Supplement) re- of the propensity scores was stratified according to the pres-

quired that, during the past year, there was adequate enroll- ence of a bipolar disorder (diagnosis or mood stabilizer pre-

ment and health care utilization to ensure availability of data scription) because the propensity score coefficients differed

for study variables, no evidence of life-threatening illness or for patients with this disorder.

institutional residence, no evidence of diabetes, and no evi- The final control group included 1 control for every 2 an-

dence of pregnancy (gestational diabetes might be misdiag- tipsychotic users, frequency-matched25 with the antipsy-

nosed) or polycystic ovarian syndrome (treated with oral hy- chotic users according to propensity score to ensure baseline

poglycemics). Cohort members could not have been in the comparability with regard to study covariates. Because we

hospital in the past month because changes in the medica- sought a control group highly comparable to the antipsy-

tion regimen cannot be identified until up to 30 days follow- chotic users, we required that the controls be matched within

ing hospital discharge. centiles (1%) of the antipsychotic propensity score distribu-

Cohort antipsychotic users had recently initiated antipsy- tion. The 1:2 matching ratio was established by a preliminary

chotic therapy by filling an antipsychotic prescription on a day analysis of the potential control pool, indicating that there were

of cohort eligibility. The first such prescription during the study too few controls to permit such close 1 to 1 matching (eAppen-

period was the qualifying prescription. They could have non- dix and eTable 5 in Supplement).

E2 JAMA Psychiatry Published online August 21, 2013 jamapsychiatry.com

Downloaded From: http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/ by a Oakland University User on 08/22/2013

Antipsychotics and the Risk of Type 2 Diabetes Original Investigation Research

Follow-up Analysis

Follow-up began on t0, the day following the filling of the quali- The statistical analysis compared the adjusted incidences of

fying prescription for the antipsychotic or control drug, which diabetes according to antipsychotic exposure status. Relative

permitted exclusion of participants based on medical care on risk was estimated with the hazard ratio (HR), calculated from

the prescription fill date (eg, schizophrenia diagnosis). Fol- Cox regression models with a robust sandwich estimation of

low-up ceased (eAppendix and eTable 6 in Supplement) with variance to account for persons reentering the cohort.27 There

the end of the study, owing to a failure of the participant to was no evidence of interaction between time and antipsy-

meet study inclusion/exclusion criteria, a diagnosis of diabe- chotic use status (HR for interaction, 1.00; P < .30), indicating

tes, or the death of the participant or 365 days following the that the proportional hazards assumption was satisfied. Re-

last day of antipsychotic/control drug use. Follow-up for con- gression models included the baseline propensity score

trols also ended with an antipsychotic prescription. Antipsy- (deciles), to adjust for residual confounding,24 as well as age

chotic users or controls who left the cohort could reenter if they and calendar year during follow-up. Other time-dependent co-

subsequently met the study eligibility criteria, unless fol- variates were not included in the primary analysis because

low-up terminated because of diabetes. these might be on the causal pathway for development of dia-

betes (eg, new diagnosis of obesity).

Antipsychotic Exposure Variables For the analyses of antipsychotic dose, the propensity score

The primary exposure variable was antipsychotic use status may not control for confounding,28 given that the distribu-

(user or control) on t0, the first day of follow-up. Because base- tion of study covariates could vary according to dose. Thus,

line exposure status did not change during follow-up, the analy- models for these analyses included a disease risk score (the

sis provided a conservative assessment of antipsychotic ef- probability of type 2 diabetes, conditional on no antipsy-

fects. At baseline, antipsychotic users were also classified chotic use), expressed as deciles. 29 Tests for the dose-

according to daily dose on t0, expressed as chlorpromazine response relationship used a single degree of freedom orthogo-

equivalents (eAppendix and eTable 7 in Supplement). nal polynomial contrast for linear trend.

We defined time-dependent antipsychotic exposure vari- An a priori subgroup analysis was performed for children

ables in order to study antipsychotic cumulative dose and ces- 6 to 17 years of age, with follow-up ending on the day before

sation of use. Cumulative dose on a given follow-up day was their 18th birthdays. Subgroup analyses also were performed

the sum of all previously dispensed antipsychotic doses (chlor- according to sex, the presence of a bipolar disorder (the most

promazine equivalents). A follow-up day was considered “re- common labeled indication for antipsychotics in the cohort),

cent use” if the prescription days of supply indicated use on use of psychostimulants (which can possibly limit weight gain),

that day or within the preceding 90 days. The “former use” of and a diagnosis of ADHD or conduct disorder.

antipsychotics was defined as more than 90 days without use Given that since 2004 guidelines have recommended rou-

of an antipsychotic. tine glucose monitoring for antipsychotic users,30 we per-

formed several analyses to assess the potential effect of dif-

Diabetes ferential screening during follow-up. Thus, follow-up time was

Newly diagnosed cases of diabetes during study follow-up were classified according to the presence of a metabolic panel with

identified from medical care encounters using an algorithm that glucose or other screening test in the past year. The screening

was validated in a sample of the study cohort.26 A primary dis- variable was lagged 90 days to exclude the tests associated with

charge diagnosis of diabetes met the case definition. Other- the diagnosis of diabetes in the cases. We also performed an

wise, we required both a diagnosis of diabetes and a prescrip- analysis that excluded person-time subsequent to 2004, which

tion for an antidiabetic medication within a 120-day period. should be little affected by screening recommendations.

We required confirmation because single outpatient diabetes- Additional analyses modeled possible clustering effects in-

related medical care encounters often were false positives. Out- troduced by the frequency matching, restricted the cohort to

patient diagnoses of diabetes in the absence of an anti- new users of antipsychotics and control medications, did not

diabetic medication prescription frequently indicated allow antipsychotic users to reenter the cohort, and utilized

subthreshold hyperglycemia, whereas prescriptions for oral hy- an alternative definition of type 2 diabetes. All analyses were

poglycemics in the absence of a diagnosis of diabetes were of- performed with SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc). All P val-

ten considered the treatment of choice for polycystic ovarian ues are 2-sided. The institutional review board at Vanderbilt

syndrome. The presumed date of the diagnosis was that of the University and the Tennessee Bureau of TennCare and the De-

earliest diabetes-related medical encounter. Type 1 diabetes partment of Health approved our study, which was funded by

was indicated by exclusive treatment with insulin; other cases grants from federal agencies with no role in study conduct or

were considered type 2 diabetes. reporting.

In the validation study,26 84% of cases identified by our

computer algorithm as having type 2 diabetes were con-

firmed as being true cases, 10% had subthreshold hypergly-

cemia, 3% had type 1 diabetes, and 3% had polycystic ovarian

Results

syndrome.26 The positive predictive value for type 2 diabetes Cohort Characteristics at Baseline

did not differ materially between antipsychotic users (82%) and The cohort included 28 858 children and youth who had re-

controls (85%). cently initiated antipsychotic therapy (eAppendix and eTable

jamapsychiatry.com JAMA Psychiatry Published online August 21, 2013 E3

Downloaded From: http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/ by a Oakland University User on 08/22/2013

Research Original Investigation Antipsychotics and the Risk of Type 2 Diabetes

Table 1. Characteristics of Cohort on the First Day of Follow-upa Table 2. Demographic Characteristics of Cases of Diabetes Mellitus

Indentified During Follow-up

Antipsy-

chotic Cases of Diabetes, %

Characteristic Controls Usersb

Type 1 Type 2

Total No. 14 429 28 858 Characteristic (n = 21) (n = 106)

Mean calendar year t0 2002.8 2002.8 Age at t0,a mean, y 13.0 16.7

Duration of prior qualifying drug use, mean, d 5.6 5.5 White race, % 47.6 73.6

Age at t0, mean, y 14.5 14.5 Male sex, % 61.9 36.8

White race, % 73.5 72.8 Standard metropolitan 61.9 74.5

statistical area, %

Male sex, % 55.9 56.0

Medicaid enrollment 28.6 34.0

Standard metropolitan statistical area, % 66.7 67.1 disabled, %

Medicaid enrollment disabled, % 26.1 26.6 a

First day of follow-up.

Psychiatric diagnoses in past year, %

Bipolar disorder 18.4 18.3

trols had initiated use of the study psychotropic drug within

Depression 19.5 19.3

a mean of fewer than 6 days prior to cohort entry.

Other mood disorder 32.5 33.3

Cohort members had a mean age of 14.5 years, and 56%

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder 38.3 38.9

were male participants (Table 1). The most frequently re-

Conduct disorder 24.9 25.3

corded psychiatric diagnoses were mood disorders (includ-

Anxiety 19.9 20.6

ing bipolar disorder), ADHD, and conduct disorder. Metabolic

Alcohol abuse 3.3 3.1 disorders and other factors potentially associated with diabe-

Other substance abuse 9.3 8.9 tes were relatively infrequent, although 23% of cohort mem-

Psychiatric inpatient stay 13.8 14.5 bers had had a diagnostic test that included glucose measure-

Psychiatric medications in past year, % ment administered in the year preceding t0.

Lithium 4.1 4.2 The median starting dose for cohort antipsychotic users

Valproate 9.3 9.5 was 67 mg (interquartile range, 33-100 mg) of chlorproma-

Lamotrigine, carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine 9.0 8.8 zine equivalents. Of antipsychotic users, 87% were pre-

Other mood stabilizer 1.8 1.8 scribed an atypical agent (eAppendix and eTable 8 in Supple-

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor 46.6 47.0 ment); use of typical antipsychotics was largely restricted to

Heterocyclic antidepressant 14.3 14.9 the earlier study years. The most frequently prescribed indi-

Psychostimulant 33.7 34.1 vidual antipsychotic was risperidone (n = 10 718; 37% of an-

α-Agonist 14.2 14.6 tipsychotic users), followed by quetiapine fumarate (n = 5807;

Benzodiazepine 12.6 12.4 20% of antipsychotic users) and olanzapine (n = 5671; 20% of

Conditions associated with metabolic disorders antipsychotic users). Risperidone users were younger, more

in past year, % likely to be male, had greater prevalence of diagnosed ADHD,

Menstruation absent or infrequent 3.7 3.8 and were started at lower doses than were users of other atypi-

Menstruation disorder, other 5.0 4.9 cal antipsychotics.

Diagnosed obesity 3.9 3.8

Metabolic disorderc 2.1 2.1 Antipsychotics and the Risk of Diabetes

Blood chemistry panel with glucose 22.5 22.9 The cohort had 55 984 person-years of follow-up, during which

Diabetes-screening procedures 5.9 5.5 there were 21 cases of type 1 diabetes (3.8 cases per 10 000 per-

Hyperlipidemia-screening procedures 8.4 8.5 son-years). These cases consisted of persons who had a mean

Cardiovascular conditions in past year, % age of 13 years, 62% were male, and 29% had Medicaid enroll-

Hypertension 2.5 2.6 ment related to disability (Table 2). Antipsychotic users had no

Other diagnosed cardiovascular disease 4.2 4.5 significantly increased risk for type 1 diabetes (HR = 1.13 [95%

a CI = 0.43-3.00]).

Unless otherwise noted, all demographic characteristics are as of the first day

of follow-up (t0), and other factors for the year preceding t0. There were 106 incident cases of type 2 diabetes (18.9 cases

b

None of the differences are statistically significant except for “Psychiatric per 10 000 person-years) during cohort follow-up. The mean

inpatient stay” (P = .03). age of the persons was 16.7 years, 37% were male, and 34% had

c

Hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, acanthosis nigricans, and hyperlipidemia. Medicaid enrollment related to disability (Table 2).

Antipsychotic users had a 3-fold increased risk for type 2

diabetes (Figure 1 and Table 3; HR = 3.03 [95% CI = 1.73-

1 in Supplement). There were 14 429 propensity score– 5.32]). The increased risk was apparent within the first year of

matched controls who had recently initiated a control psycho- follow-up (HR = 2.49 [95% CI = 1.27-4.88]). Risk did not vary

tropic drug and who were selected from 122 738 potential con- significantly according to baseline dose but did increase with

trols. By virtue of the matching, the baseline characteristics cumulative dose during follow-up (Table 2). The HR for co-

of the controls were entirely comparable to those of the anti- hort members with a cumulative dose of 100 g or greater of

psychotic users (Table 1). Both antipsychotic users and con- chlorpromazine equivalents was 5.43 [95% CI = 2.34-12.61],

E4 JAMA Psychiatry Published online August 21, 2013 jamapsychiatry.com

Downloaded From: http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/ by a Oakland University User on 08/22/2013

Antipsychotics and the Risk of Type 2 Diabetes Original Investigation Research

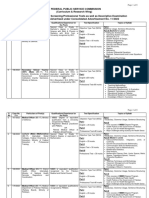

Figure 1. Cumulative Incidence of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, According to Baseline Antipsychotic Use and Using

the Kaplan-Meier Method

.014

Control medication HR =3.03 (95% CI=1.73-5.32)

.012 Antipsychotic drug

Probability of Type 2 Diabetes

.010

.008

.006

.004

.002

0

0 1 2 3 4

Years of Follow-Up

No. of Children and Youth at Risk

Control medication 14 417 7799 2504 1074 485

Antipsychotic drug 28 825 17 803 5066 2188 972

HR, hazard ratio (adjusted).

Table 3. Risk of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus by Antipsychotic Exposure Status

Person- Rate per 104

Status Years Cases Person-Years HR (95% CI)

No antipsychotic use in nonuser control group 17 963 14 7.8 1 [Reference]a

Antipsychotic use at baseline for all 24.2

38 022 92 3.03 (1.73-5.32)

antipsychotic users

Antipsychotic users, according to baseline daily

dose of antipsychotic

<50 mg 12 777 22 17.2 2.65 (1.69-5.77)

50-99 mg 11 991 30 25.0 3.07 (1.63-5.78)

≥100 mg 13 254 40 30.2 3.13 (1.33-5.30)

Antipsychotic users, according to cumulative

dose of antipsychotic during follow-upb Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio

<5 g 13 634 27 19.8 2.13 (1.06-4.27) (adjusted).

a

5-99 g 21 734 56 25.8 3.42 (1.88-6.24) Reference for all comparisons is the

33.9 nonuser control group.

≥100 g 2654 9 5.43 (2.34-12.61)

b

Antipsychotic users, according to continuity P < .04 (test for dose-response

of use during follow-upc relationship).

c

Former (use ceased for >90 d) 11 388 26 22.8 2.57 (1.34-4.91) Follow-up persisted for 365 days

following last dispensed day of

Recent (use within past 90 d) 26 634 66 24.8 3.19 (1.77-5.74)

antipsychotic medication.

whereas the HR for those with a cumulative dose of less than lative dose of all atypical antipsychotics, including risperi-

5 g of chlorpromazine equivalents was 2.13 [95% CI = 1.06- done, which drug was used by approximately 40% of the co-

4.27] (P = .04). The risk remained elevated for up to 1 year fol- hort antipsychotic users (eAppendix and eTable 9 in

lowing the discontinuation of antipsychotic use (HR = 2.57 [95% Supplement). Significantly increased HRs were present for

CI = 1.34-4.91]). Although this was less than that for cohort other atypical antipsychotics; the difference between HRs for

members who continued to use antipsychotics (HR = 3.19 [95% risperidone and HRs for aripiprazole was statistically signifi-

CI = 1.77-5.74]), the difference was not statistically signifi- cant (P < .001).

cant. We examined several subgroups defined by baseline co-

When the cohort was restricted to children 6 to 17 years hort characteristics (Figure 3), including age, sex, presence of

of age, antipsychotic users had more than a 3-fold increased a bipolar disorder, psychostimulant use, and a diagnosis of

risk of type 2 diabetes (Figure 2; HR = 3.14 [95% CI = 1.50- either ADHD or conduct disorder. For each of these sub-

6.56]). For these children, the incidence increased with in- groups, the risk of type 2 diabetes was significantly increased

creasing cumulative dose (Figure 2), from an HR of 2.00 (95% for antipsychotic users, and the estimates for the subgroups

CI = 0.76-5.30) for cumulative doses of less than 5 g to an HR defined by the individual factors did not differ statistically.

of 7.05 (95% CI = 2.63-18.89) for cumulative doses of 100 g or We also assessed the risk of type 2 diabetes according to

more (P = .03). screening for elevated glucose levels in either the year pre-

We examined the risk for atypical antipsychotics, which ceding t0 or during follow-up (Figure 3). For the controls, 28%

were used by 87% of cohort users, and for individual atypical of the follow-up person-time had such screening, as did 33%

drugs. The risk for type 2 diabetes increased with the cumu- of the person-time for the antipsychotic users. Both expo-

jamapsychiatry.com JAMA Psychiatry Published online August 21, 2013 E5

Downloaded From: http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/ by a Oakland University User on 08/22/2013

Research Original Investigation Antipsychotics and the Risk of Type 2 Diabetes

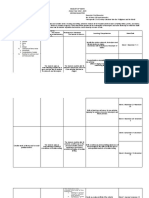

Figure 2. Adjusted Annual Incidence of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Among Children and Youth 6 to 17 Years

of Age, According to Cumulative Antipsychotic Dose

P < .03

60

Type 2 Diabetes per 10 000 Person-Years

40

20

0 The vertical bars represent 95% CIs.

Control <5 g 5-99 g ≥100 g

The P value is for the test for the

Cumulative Antipsychotic Dose, Chlorpromazine Equivalents

dose-response relationship. Adjusted

incidence was calculated by

Diabetes cases: 8 15 33 8 multiplying the incidence in the

Person-years: 13 536 10 154 16 786 2076 control group by the hazard ratio,

with an analogous calculation for the

95% CIs.

Figure 3. Risk of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus for Antipsychotic Users Within Subgroups Defined by Baseline Cohort Characteristics

Controls Antipsychotic Users

P-y No. P-y No. Hazard ratio

(95% CI)

13 536 8 29 015 56 3.14 (1.50-6.56) Age, y <18

4427 6 9006 36 2.95 (1.23-7.02) ≥18

11 071 4 23 793 35 3.86 (1.39-10.74) Sex Male

6892 10 14 229 57 2.67 (1.36-5.23) Female

4538 2 11 265 32 6.66 (1.58-28.14) Bipolar disorder Yes

13 425 12 26 756 60 2.41 (1.29-4.50) diagnosis No

7420 2 15 540 25 5.71 (1.35-24.07) Stimulant use Yes

10 543 12 22 482 67 2.65 (1.43-4.91) No

10 817 6 23 236 48 3.57 (1.52-8.36) ADHD/conduct Yes

7146 8 14 786 44 2.62 (1.23-5.62) disorder No

diagnosis

4985 8 12 306 46 2.44 (1.15-5.18) Glucose screen Yes

12 978 6 25 715 46 3.64 (1.55-8.50) (baseline or No

during follow-up)

3359 6 8892 39 2.54 (1.08-6.00) Glucose screen Yes

14 603 8 29 129 53 3.17 (1.51-6.68) (follow-up only) No

0 1 5 10 20 30

Antipsychotic decreases risk Antipsychotic increases risk

Hazard Ratio

No., number of cases of type 2 diabetes; P-y, person-years of follow-up.

sure groups had increased HRs for type 2 diabetes, and these The increased risk of type 2 diabetes among antipsy-

did not differ significantly according to screening status. Simi- chotic users persisted in several sensitivity analyses that as-

lar results were present in an analysis according to the pres- sessed study assumptions (eAppendix and eTable 10 in Supple-

ence of a screening test during follow-up (there was a mean ment). These analyses included control for possible clustering

number of 0.35 tests during follow-up for the controls and of induced by the frequency matching (HR = 3.07 [95% CI = 1.74-

0.51 tests for the antipsychotic users). An analysis that ex- 5.39]), restriction of the cohort to new users of antipsychotics

cluded person-time subsequent to 2004 (the year of the first and control psychotropic medications (HR = 3.05 [95%

publication of guidelines recommending screening of antipsy- CI = 1.70-5.46]), not permitting antipsychotic users who left the

chotic users30) also demonstrated increased risk for antipsy- cohort to reenter (HR = 2.86 [95% CI = 1.55-5.26]), and use of

chotic users (HR = 2.73 [95% CI = 1.35-5.53]). an alternative definition for type 2 diabetes that required a pre-

E6 JAMA Psychiatry Published online August 21, 2013 jamapsychiatry.com

Downloaded From: http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/ by a Oakland University User on 08/22/2013

Antipsychotics and the Risk of Type 2 Diabetes Original Investigation Research

scription to confirm a diagnosis, except in the case of a pri- covariates, many of which either are plausibly associated

mary inpatient diagnosis (HR = 3.11 [95% CI = 1.74-5.57]). In with increased body mass or might mediate an association

each of these analyses, the risk for type 2 diabetes increased between obesity and antipsychotic use. These included

with cumulative antipsychotic dose (eAppendix and eTable 10 diagnosed obesity, disorders or diagnostic testing linked to

in Supplement). excess weight, psychiatric diagnoses, psychotropic drug

use, and demographic characteristics. The observed dose-

response relationship is further evidence that the study

findings were not due to confounding by obesity.

Discussion For adults, the risk of type 2 diabetes conferred by anti-

In this cohort of children and youth who had recently initi- psychotics is most pronounced for atypical antipsychotics32

ated use of an antipsychotic or a control psychotropic drug, an- and may vary according to specific drug.10,33 In the study

tipsychotic users had a risk of newly diagnosed type 2 diabe- cohort, 87% of antipsychotic users received atypical drugs.

tes 3 times greater than that for propensity score–matched Study findings were largely unchanged when the cohort was

controls. The excess risk occurred within the first year of an- restricted to this group or to risperidone, the most fre-

tipsychotic use, increased with cumulative antipsychotic dose, quently prescribed individual drug. Olanzapine, quetiapine,

and was present for children 6 to 17 years of age. The in- ziprasidone, and aripiprazole were used less frequently, but

creased risk persisted for up to 1 year following cessation of each had a significantly elevated HR. However, this post hoc

antipsychotic use. finding must be interpreted cautiously. There was marked

Study cases of type 2 diabetes were identified from diag- variation in the baseline characteristics of users of specific

noses from clinical practitioners and prescriptions for antidia- antipsychotics. Our study was not designed to study the

betic drugs. Thus, there was the potential for false positives. comparative risk of individual drugs, given that sample size

However, a validation study conducted in a cohort sample did not permit a propensity score match for specific antipsy-

found that the case definition had a positive predictive value chotics. Furthermore, it is possible that high-risk patients

of 84% and that this did not differ materially according to an- may have been recommended a drug perceived to have

tipsychotic use status. These data suggest that the errors made greater metabolic safety.34

by clinical practitioners in the diagnosis of diabetes are un- Both the pathophysiology and the epidemiology of type

likely to explain the study findings. 2 diabetes indicate that its development is a chronic process.35

Another type of misclassification that may have affected Although the risk of type 2 diabetes did increase with cumu-

our findings was the incomplete identification of type 2 dia- lative dose of antipsychotics, which is consistent with a chronic

betes in the cohort. In routine practice, many children and process, we also found that a significantly increased risk was

youth may not undergo the testing necessary for this diag- present during the first year of therapy. Cases of early-onset

nosis. This could introduce bias if the diagnostic scrutiny of antipsychotic-associated diabetes have been reported for

the antipsychotic group was greater than that for controls. adults. In one series,36 the majority of cases occurred within

To minimize this potential bias, we sought to ensure compa- 6 months of drug initiation. Although there are fewer case re-

rability of medical surveillance for both groups. Thus, anti- ports in the literature for children, early-onset cases also have

psychotic users and controls had recently initiated psycho- been described.37,38 Further study of the pathophysiology of

tropic drug therapy and were closely matched at baseline antipsychotic-associated diabetes is needed.

according to glucose or diabetes screening tests, as well as In the study cohort, there were an estimated 15.8 addi-

recent medical care utilization, which is an indicator of tional cases of type 2 diabetes per 10 000 person-years of

diagnostic scrutiny. antipsychotic exposure, or a number needed to harm of 633.

However, guidelines published in 2004 recommending However, this number should be applied cautiously in clini-

routine glucose monitoring for antipsychotic users could have cal practice because the baseline risk for a child or youth will

led to differential surveillance during follow-up. Thus, we per- vary substantially according to age and body mass index. Fur-

formed several analyses to assess this possibility. When data thermore, the study cohort consisted of Tennessee Medicaid

were analyzed according to the presence of a screening test, enrollees (approximately 40% of the state's children), which

either at any time or only during follow-up, the increased risk also limits the generalizability of study findings, given that the

was present for both those who were and those were not incidence of type 2 diabetes in children covered by Medicaid

screened. This analysis should be conservative, given that may be elevated owing to economic and social factors, as well

screening could be triggered by antipsychotic-related weight as to a greater prevalence of behavioral risk factors, 39,40

gain. Furthermore, in an analysis that excluded person-time disability,41 and chronic illness.42,43

subsequent to the year of guideline publication, the magni- In conclusion, in the study cohort of children and youth

tude of the increased risk for antipsychotic users was little between 6 and 24 years of age, those recently initiating an

changed. antipsychotic medication had a 3-fold greater risk of newly

We could not directly control for obesity, which is diagnosed type 2 diabetes than did propensity score–

closely linked to the development of type 2 diabetes.31 How- matched controls. Risk was elevated during the first year of

ever, a material difference in body mass index between anti- antipsychotic use, increased with increasing cumulative

psychotic users and controls seems unlikely, given that con- dose, and was present for children younger than 18 years of

trols were very closely matched according to 115 study age.

jamapsychiatry.com JAMA Psychiatry Published online August 21, 2013 E7

Downloaded From: http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/ by a Oakland University User on 08/22/2013

Research Original Investigation Antipsychotics and the Risk of Type 2 Diabetes

ARTICLE INFORMATION intolerance in youth treated with of data collection of self-reported medicine use

Submitted for Publication: September 11, 2012; second-generation antipsychotic medications. Can among the elderly. Gerontologist.

final revision received December 2, 2012; accepted J Psychiatry. 2009;54(11):743-749. 1988;28(5):672-676.

January 21, 2013. 6. Hammerman A, Dreiher J, Klang SH, Munitz H, 21. Johnson RE, Vollmer WM. Comparing sources

Published Online: August 21, 2013. Cohen AD, Goldfracht M. Antipsychotics and of drug data about the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc.

doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2053. diabetes: an age-related association. Ann 1991;39(11):1079-1084.

Pharmacother. 2008;42(9):1316-1322. 22. West SL, Savitz DA, Koch G, Strom BL, Guess

Author Contributions: All authors had full access

to all of the data in the study and take responsibility 7. Andrade SE, Lo JC, Roblin D, et al. Antipsychotic HA, Hartzema A. Recall accuracy for prescription

for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the medication use among children and risk of diabetes medications: self-report compared with database

data analysis. mellitus. Pediatrics. 2011;128(6):1135-1141. information. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142(10):1103-

Study concept and design: All authors. 8. Newcomer JW. Second-generation (atypical) 1112.

Acquisition of data: Bobo, Cooper, Daugherty, Ray. antipsychotics and metabolic effects: a 23. World Health Organization (WHO). The Health

Analysis and interpretation of data: Bobo, Cooper, comprehensive literature review. CNS Drugs. of Youth. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 1989.

Stein, Olfson, Graham, Ray. 2005;19(suppl 1):1-93. Document A42/Technical Discussions/2.

Drafting of the manuscript: Bobo, Ray. 9. Kessing LV, Thomsen AF, Mogensen UB, 24. Glynn RJ, Schneeweiss S, Stürmer T. Indications

Critical revision of the manuscript for important Andersen PK. Treatment with antipsychotics and for propensity scores and review of their use in

intellectual content: All authors. the risk of diabetes in clinical practice. Br J pharmacoepidemiology. Basic Clin Pharmacol

Statistical analysis: Graham, Ray. Psychiatry. 2010;197(4):266-271. Toxicol. 2006;98(3):253-259.

Obtained funding: Ray.

Administrative, technical, or material support: 10. Lambert BL, Cunningham FE, Miller DR, Dalack 25. Rothman KJ, Greenland S. Modern

Cooper, Daugherty. GW, Hur K. Diabetes risk associated with use of Epidemiology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA:

Study supervision: Cooper, Ray. olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone in veterans Lippincott-Raven; 1998.

health administration patients with schizophrenia. 26. Bobo WV, Cooper WO, Stein CM, et al. Positive

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr Bobo has Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164(7):672-681.

received research support from Cephalon and predictive value of a case definition for diabetes

served on speaker bureaus for Janssen 11. Nielsen J, Skadhede S, Correll CU. mellitus using automated administrative health

Pharmaceutica and Pfizer. Dr Olfson has received Antipsychotics associated with the development of data in children and youth exposed to antipsychotic

support from a research grant to Columbia type 2 diabetes in antipsychotic-naïve drugs or control medications: a Tennessee Medicaid

University from Eli Lilly (end date June 20, 2010) schizophrenia patients. Neuropsychopharmacology. study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12(1):128.

and one from Bristol-Myers Squibb (end date 2010;35(9):1997-2004. 27. Donner A, Klar N. Design and Analysis of Cluster

January 31, 2010). No other disclosures are 12. Correll CU, Manu P, Olshanskiy V, Napolitano B, Randomization Trials in Health Research. London,

reported. Kane JM, Malhotra AK. Cardiometabolic risk of England: Arnold; 2000.

Funding/Support: This study was supported by the second-generation antipsychotic medications 28. Arbogast PG, Ray WA. Use of disease risk

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, during first-time use in children and adolescents. scores in pharmacoepidemiologic studies. Stat

Centers for Education and Research on JAMA. 2009;302(16):1765-1773. Methods Med Res. 2009;18(1):67-80.

Therapeutics cooperative agreement (grant 13. Correll CU. Weight gain and metabolic effects of 29. Arbogast PG, Ray WA. Performance of disease

HS1-16974). mood stabilizers and antipsychotics in pediatric risk scores, propensity scores, and traditional

Disclaimer: The views expressed are solely the bipolar disorder: a systematic review and pooled multivariable outcome regression in the presence

responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily analysis of short-term trials. J Am Acad Child of multiple confounders. Am J Epidemiol.

represent the official views of the US Food and Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(6):687-700. 2011;174(5):613-620.

Drug Administration. 14. Maglione M, Maher AR, Hu J, et al. Off-label use 30. American Diabetes Association; American

Additional Information: The first draft of the of atypical antipsychotics: an update [internet]. Psychiatric Association; American Association of

article was written by Drs Bobo and Ray, who vouch AHRQ Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. 2011; No. Clinical Endocrinologists; North American

for the data and the analysis. 43. Association for the Study of Obesity. Consensus

Additional Contributions: We gratefully 15. Alexander GC, Gallagher SA, Mascola A, development conference on antipsychotic drugs

acknowledge the Tennessee Bureau of Medicaid Moloney RM, Stafford RS. Increasing off-label use of and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Care.

and the Department of Health, which provided antipsychotic medications in the United States, 2004;27(2):596-601.

study data. 1995-2008. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 31. Stumvoll M, Goldstein BJ, van Haeften TW. Type

2011;20(2):177-184. 2 diabetes: principles of pathogenesis and therapy.

REFERENCES 16. Kutcher S, Aman M, Brooks SJ, et al. Lancet. 2005;365(9467):1333-1346.

1. Olfson M, Blanco C, Liu L, Moreno C, Laje G. International consensus statement on 32. Smith M, Hopkins D, Peveler RC, Holt RI,

National trends in the outpatient treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Woodward M, Ismail K. First- v. second-generation

children and adolescents with antipsychotic drugs. and disruptive behaviour disorders (DBDs): clinical antipsychotics and risk for diabetes in

Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(6):679-685. implications and treatment practice suggestions. schizophrenia: systematic review and

Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2004;14(1):11-28. meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192(6):

2. Crystal S, Olfson M, Huang C, Pincus H, Gerhard

T. Broadened use of atypical antipsychotics: safety, 17. Kowatch RA, Fristad M, Birmaher B, Wagner KD, 406-411.

effectiveness, and policy challenges. Health Aff Findling RL, Hellander M; Child Psychiatric 33. Yood MU, DeLorenze G, Quesenberry CP Jr,

(Millwood). 2009;28(5):w770-w781. Workgroup on Bipolar Disorder. Treatment et al. The incidence of diabetes in atypical

guidelines for children and adolescents with bipolar antipsychotic users differs according to

3. Cooper WO, Hickson GB, Fuchs C, Arbogast PG, disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.

Ray WA. New users of antipsychotic medications agent—results from a multisite epidemiologic study.

2005;44(3):213-235. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18(9):791-799.

among children enrolled in TennCare. Arch Pediatr

Adolesc Med. 2004;158(8):753-759. 18. Ray WA, Griffin MR. Use of Medicaid data for 34. De Hert M, Dobbelaere M, Sheridan EM, Cohen

pharmacoepidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. D, Correll CU. Metabolic and endocrine adverse

4. Cooper WO, Arbogast PG, Ding H, Hickson GB, 1989;129(4):837-849.

Fuchs DC, Ray WA. Trends in prescribing of effects of second-generation antipsychotics in

antipsychotic medications for US children. Ambul 19. Ray WA. Population-based studies of adverse children and adolescents: a systematic review of

Pediatr. 2006;6(2):79-83. drug effects. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(17):1592- randomized, placebo controlled trials and

1594. guidelines for clinical practice. Eur Psychiatry.

5. Panagiotopoulos C, Ronsley R, Davidson J. 2011;26(3):144-158.

Increased prevalence of obesity and glucose 20. Landry JA, Smyer MA, Tubman JG, Lago DJ,

Roberts J, Simonson W. Validation of two methods

E8 JAMA Psychiatry Published online August 21, 2013 jamapsychiatry.com

Downloaded From: http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/ by a Oakland University User on 08/22/2013

Antipsychotics and the Risk of Type 2 Diabetes Original Investigation Research

35. Nolan CJ, Damm P, Prentki M. Type 2 diabetes an evidence-based approach to atypical 42. Hing E, Hall MJ, Xu J. National Hospital

across generations: from pathophysiology to antipsychotic use in children and adolescents. J Can Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2006 outpatient

prevention and management. Lancet. Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;19(2):124-137. department summary. Natl Health Stat Report.

2011;378(9786):169-181. 39. Hampl SE, Carroll CA, Simon SD, Sharma V. 2008;(4):1-31.

36. Newcomer JW, Haupt DW. The metabolic Resource utilization and expenditures for 43. Shatin D, Levin R, Ireys HT, Haller V. Health care

effects of antipsychotic medications. Can J overweight and obese children. Arch Pediatr utilization by children with chronic illnesses: a

Psychiatry. 2006;51(8):480-491. Adolesc Med. 2007;161(1):11-14. comparison of Medicaid and employer-insured

37. Bloch Y, Vardi O, Mendlovic S, Levkovitz Y, 40. Alaimo K, Olson CM, Frongillo EA Jr. Low family managed care. Pediatrics. 1998;102(4):44.

Gothelf D, Ratzoni G. Hyperglycemia from income and food insufficiency in relation to

olanzapine treatment in adolescents. J Child overweight in US children: is there a paradox? Arch

Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2003;13(1):97-102. Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155(10):1161-1167.

38. Panagiotopoulos C, Ronsley R, Elbe D, 41. Rosenbaum S. Medicaid. N Engl J Med.

Davidson J, Smith DH. First do no harm: promoting 2002;346(8):635-640.

jamapsychiatry.com JAMA Psychiatry Published online August 21, 2013 E9

Downloaded From: http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/ by a Oakland University User on 08/22/2013

You might also like

- Concise Definitive Review: Stress Ulcer ProphylaxisDocument11 pagesConcise Definitive Review: Stress Ulcer ProphylaxisMuhammad Umar RazaNo ratings yet

- Alternative Vaccine ScheduleDocument2 pagesAlternative Vaccine ScheduleAndreea PanaitNo ratings yet

- General Engineering Knowledge: H. D. Mcgeorge, Ceng, Fimare, MrinaDocument1 pageGeneral Engineering Knowledge: H. D. Mcgeorge, Ceng, Fimare, MrinaThomas JoseNo ratings yet

- Nej Mo A 1312828Document11 pagesNej Mo A 1312828هناء همة العلياNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Dr. BobbinDocument11 pagesJurnal Dr. BobbinNhiyar Indah HasniarNo ratings yet

- Association of Hormonal Contraception With Depression: Original InvestigationDocument9 pagesAssociation of Hormonal Contraception With Depression: Original InvestigationBruno Pinheiro CNo ratings yet

- Manu Et Al-2015-Acta Psychiatrica ScandinavicaDocument12 pagesManu Et Al-2015-Acta Psychiatrica ScandinavicamerianaNo ratings yet

- Drug Utilization Evaluation of Antidiabetic Drugs Among Type 2 Diabetes Patients of Tamil NaduDocument4 pagesDrug Utilization Evaluation of Antidiabetic Drugs Among Type 2 Diabetes Patients of Tamil NaduMelly MV HutasoitNo ratings yet

- A Retrospective Cohort Study of Diabetes Mellitus and Antipsychotic Treatment in The United StatesDocument7 pagesA Retrospective Cohort Study of Diabetes Mellitus and Antipsychotic Treatment in The United StatesDeegh MudhaNo ratings yet

- Artigo InglesDocument11 pagesArtigo InglesEllen AndradeNo ratings yet

- ACOs DepresiónDocument9 pagesACOs DepresiónSamu Saad PestanaNo ratings yet

- Artikel Eso 4Document8 pagesArtikel Eso 4Selly maulidinaNo ratings yet

- Clortalidona Vs HCLDocument10 pagesClortalidona Vs HCLdiana stefhany marin ramirezNo ratings yet

- Chittaranjan, A. 2017Document4 pagesChittaranjan, A. 2017Andrea HenaoNo ratings yet

- Adolescents DMT1Document8 pagesAdolescents DMT1Mia ValdesNo ratings yet

- 10 1001@jamapsychiatry 2017 3544Document10 pages10 1001@jamapsychiatry 2017 3544Mohamed AbozeidNo ratings yet

- Dose-Response Association of Early-Life Antibiotic Exposure and Subsequent Overweight or Obesity in Children A Meta-Analysis of Prospective StudiesDocument12 pagesDose-Response Association of Early-Life Antibiotic Exposure and Subsequent Overweight or Obesity in Children A Meta-Analysis of Prospective StudiesxinNo ratings yet

- Jamapsychiatry Huybrechts 2017 Oi 170090Document9 pagesJamapsychiatry Huybrechts 2017 Oi 170090Lara ReisNo ratings yet

- Paediatrica Indonesiana: Dwi Novianti, Tiangsa Sembiring, Sri Sofyani, Tri Faranita, Winra PratitaDocument7 pagesPaediatrica Indonesiana: Dwi Novianti, Tiangsa Sembiring, Sri Sofyani, Tri Faranita, Winra PratitaMatthew NathanielNo ratings yet

- RRL3 RLRLDocument18 pagesRRL3 RLRLRowena BayalanNo ratings yet

- NPP 2015275Document10 pagesNPP 2015275Weverson LinharesNo ratings yet

- Associations of Per Uoroalkyl and Poly Uoroalkyl Substances With Incident Diabetes and Microvascular DiseaseDocument9 pagesAssociations of Per Uoroalkyl and Poly Uoroalkyl Substances With Incident Diabetes and Microvascular Diseasespadini putriNo ratings yet

- Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome Advances in Diagnosis and TreatmentDocument14 pagesNeonatal Abstinence Syndrome Advances in Diagnosis and TreatmentdzratsoNo ratings yet

- Nonpharmacological Interventions To Prevent DeliriumDocument12 pagesNonpharmacological Interventions To Prevent Deliriumjuan.pablo.castroNo ratings yet

- Hudson 2003Document10 pagesHudson 2003Borja Recuenco CayuelaNo ratings yet

- Anticonvulsant Medications and The Risk of Suicide, Attempted Suicide, or Violent DeathDocument9 pagesAnticonvulsant Medications and The Risk of Suicide, Attempted Suicide, or Violent DeathMarcelo MonteiroNo ratings yet

- Nej Mo A 1312828Document11 pagesNej Mo A 1312828Chu DatsuNo ratings yet

- Diabetic Emergencies PDFDocument20 pagesDiabetic Emergencies PDFhenry leonardo gaona pinedaNo ratings yet

- 0 Diabetic Hyperglicemic Emergencies A Sistematic ApproachDocument20 pages0 Diabetic Hyperglicemic Emergencies A Sistematic ApproachKaryn AlbaNo ratings yet

- Nejmoa 2008663Document10 pagesNejmoa 2008663emmyNo ratings yet

- KWR 394Document10 pagesKWR 394Peni HeryaniNo ratings yet

- Assessment of College Students Awareness and Knowledge About Conditions Relevant To Metabolic SyndromeDocument15 pagesAssessment of College Students Awareness and Knowledge About Conditions Relevant To Metabolic SyndromeManimegalai SNo ratings yet

- Heath2018 PDFDocument8 pagesHeath2018 PDFFelicia FloraNo ratings yet

- Proton Pump Inhibitor Use and The Risk of Chronic Kidney DiseaseDocument9 pagesProton Pump Inhibitor Use and The Risk of Chronic Kidney DiseaseDita IndahNo ratings yet

- Ada Easd 2012Document16 pagesAda Easd 2012Susannah OdettaNo ratings yet

- Antipsychotic Use in Pregnancy and The Risk For Congenital MalformationsDocument9 pagesAntipsychotic Use in Pregnancy and The Risk For Congenital MalformationsRirin WinataNo ratings yet

- 529-Einstein 5 3 1 246-251Document7 pages529-Einstein 5 3 1 246-251Gatwech DechNo ratings yet

- RosperidonDocument7 pagesRosperidonEndang SusilowatiNo ratings yet

- Focus Paper PregDocument12 pagesFocus Paper PregMaria Magdalena DumitruNo ratings yet

- Switch Olanzapin Ke RisperidonDocument10 pagesSwitch Olanzapin Ke RisperidonAnonymous Ca0YyWNnVNo ratings yet

- 2017 Antipsychotic-Associated Weight Gain Management Strategies and Impact On Treatment AdherenceDocument11 pages2017 Antipsychotic-Associated Weight Gain Management Strategies and Impact On Treatment AdherenceanonNo ratings yet

- Health Literacy and Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Among Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients in The Northeast of ThailandDocument7 pagesHealth Literacy and Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Among Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients in The Northeast of ThailandFatima Rima AndiniNo ratings yet

- Depression During PregnancyDocument17 pagesDepression During PregnancySellymarlinaleeNo ratings yet

- 2016, Bechard BmiDocument8 pages2016, Bechard Bmizeenat04hashmiNo ratings yet

- Calderon Margalit2009Document8 pagesCalderon Margalit2009Aulya ArchuletaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S089085671931929XDocument12 pages1 s2.0 S089085671931929XFahrunnisa NurdinNo ratings yet

- DM Type 2Document8 pagesDM Type 2dana putraNo ratings yet

- XlskdsladDocument9 pagesXlskdsladJoãoNo ratings yet

- DM 2Document8 pagesDM 2Roberto AlexiNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Medication Adherence To JNC-7 Guidelines and Risk Factors For Hypertension in A South Indian Tertiary Care HospitalDocument12 pagesAssessment of Medication Adherence To JNC-7 Guidelines and Risk Factors For Hypertension in A South Indian Tertiary Care HospitalSophian HaryantoNo ratings yet

- Adherence of Psychopharmacological Prescriptions To Clinical PDFDocument9 pagesAdherence of Psychopharmacological Prescriptions To Clinical PDFGaby ZavalaNo ratings yet

- Prevalence and Predictors of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Adult Survivors of Childhood CancerDocument13 pagesPrevalence and Predictors of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Adult Survivors of Childhood CancerImran A. IsaacNo ratings yet

- A Randomised Controlled Trial of Dietary Improvement For Adults With Major Depression (The SMILES' Trial)Document13 pagesA Randomised Controlled Trial of Dietary Improvement For Adults With Major Depression (The SMILES' Trial)agalbimaNo ratings yet

- Ada Cvd-Renalcompendium Fin-WebDocument32 pagesAda Cvd-Renalcompendium Fin-WebJoseph Antonio Apaza GómezNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 6nnnnjnDocument8 pagesJurnal 6nnnnjnFirstiafina TiffanyNo ratings yet

- Amer Peds Recomm Re Psy Drugs and PregnancyDocument10 pagesAmer Peds Recomm Re Psy Drugs and Pregnancyscribd4kmhNo ratings yet

- Greden2019 - OriginalDocument9 pagesGreden2019 - Originalاحمد صباح مالكNo ratings yet

- Cancer - 15 December 1982 - Bernstein - Food Aversions in Children Receiving Chemotherapy For CancerDocument3 pagesCancer - 15 December 1982 - Bernstein - Food Aversions in Children Receiving Chemotherapy For Cancerhelda fitria wahyuniNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0920996420301584 MainDocument10 pages1 s2.0 S0920996420301584 MainAndreaNo ratings yet

- Polsky 2005Document7 pagesPolsky 2005Tatiana FlorianNo ratings yet

- Tourette For ChildrenDocument9 pagesTourette For ChildrenPedro GuimarãesNo ratings yet

- The Essential Guide to Prescription Drugs, Update on RemdesivirFrom EverandThe Essential Guide to Prescription Drugs, Update on RemdesivirNo ratings yet

- MinervaProject - Toward The Hybrid Future - Insights2023Document26 pagesMinervaProject - Toward The Hybrid Future - Insights2023Jimmy SimpsonNo ratings yet

- Web-Based Facilitated Learning or Blended LearningDocument11 pagesWeb-Based Facilitated Learning or Blended LearningfilipinianaNo ratings yet

- Accelerated Math in The Classroom: Grades K-6Document16 pagesAccelerated Math in The Classroom: Grades K-6catherineholthausNo ratings yet

- Malimono Campus Learning Continuity PlanDocument7 pagesMalimono Campus Learning Continuity PlanEmmylou BorjaNo ratings yet

- Edid 6507-Group Project-Needs Assessment ReportDocument49 pagesEdid 6507-Group Project-Needs Assessment Reportapi-298012003No ratings yet

- Pa-3 Literature Rev WKST PDFDocument2 pagesPa-3 Literature Rev WKST PDFAishah GojeNo ratings yet

- MedTerm Machine LearningDocument14 pagesMedTerm Machine LearningMOhmedSharafNo ratings yet

- CFM Case SudyDocument2 pagesCFM Case SudysamruddhiNo ratings yet

- Group Scoring SheetDocument1 pageGroup Scoring SheetDon Carlson Astorga MatutinaNo ratings yet

- Social Organization - WikipediaDocument38 pagesSocial Organization - WikipediaPat ONo ratings yet

- Common Techniques in Teaching of ReadingDocument4 pagesCommon Techniques in Teaching of ReadingresearchparksNo ratings yet

- Bosch Solidworks PracticalDocument2 pagesBosch Solidworks Practicaljasbir999No ratings yet

- English: Quarter 1 - Module 6Document22 pagesEnglish: Quarter 1 - Module 6Khiem AmbidNo ratings yet

- Combined Ad No 11-2022Document9 pagesCombined Ad No 11-2022FaizaNo ratings yet

- DBOW English 9Document4 pagesDBOW English 9dennis camposNo ratings yet

- Hasil Turnitin Pengaruh Terapi Bekam Terhadap Penurunan Nyeri Kepala Pada Penderita HipertensiDocument62 pagesHasil Turnitin Pengaruh Terapi Bekam Terhadap Penurunan Nyeri Kepala Pada Penderita HipertensiVita AmiliaNo ratings yet

- Today's Youth Are Tomorrow's Better CitizensDocument3 pagesToday's Youth Are Tomorrow's Better CitizensAishwarya MNo ratings yet

- Ways To Use Thinglink in The ClassroomDocument106 pagesWays To Use Thinglink in The ClassroomRamiro Lagos AltamiranoNo ratings yet

- 5 A Different Kind of SchoolDocument2 pages5 A Different Kind of SchoolArchanaNo ratings yet

- Albert Einstein Class 11Document2 pagesAlbert Einstein Class 11Aayushi TomarNo ratings yet

- Martha Raile Alligood (Inggris)Document19 pagesMartha Raile Alligood (Inggris)uli0% (1)

- Ipcrf 2022 2023 CCS 1Document11 pagesIpcrf 2022 2023 CCS 1Krisna Isa PenalosaNo ratings yet

- OPM3 A Comprehensive Playbook For PMPDocument195 pagesOPM3 A Comprehensive Playbook For PMPGiap le Dinh100% (1)

- Sel ListDocument66 pagesSel Listcharuhans nandgaonkarNo ratings yet

- 8overall: The Mentor's GuideDocument8 pages8overall: The Mentor's GuideClaudia Zamora100% (1)

- Cot 3Document2 pagesCot 3Geraldine Dela Torre Matias100% (1)

- Creative Writing BowDocument5 pagesCreative Writing BowJabie TorresNo ratings yet

- CV/Resume Nikola HorvatDocument3 pagesCV/Resume Nikola HorvatAnonymous NpZI8AWNo ratings yet