Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Dream Bizarreness Revisited

Uploaded by

Olivier BenarrocheOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Dream Bizarreness Revisited

Uploaded by

Olivier BenarrocheCopyright:

Available Formats

EDITORIAL

Dream Bizarreness Reconsidered

Claudio Colace, Ph.D.

INTRODUCTION neurobiological conditions that are found

only in REM sleep (7-14). In addition, this

reams frequently show impossible approach emphasizes the role of PGO

D and/or improbable aspects compared

with common life experiences, which have

(ponto-geniculo-occipital) activity in

determining dream bizarreness, on which

been referred to as “dream bizarreness”. two other neurobiological models, the

Although the issue of dream bizarreness “reverse learning” theory (15) and

has already been discussed by the Seligman and Yellen’s model (16) are also

psychoanalytic dream theory, the first grounded.

systematic investigations on this aspect of This paper will review the literature on

dreaming only began in the Sixties, when a dream bizarreness in order to demonstrate

few authors started attempting to measure that the current neurobiological approach

dream bizarreness by objective indicators to dreaming, represented primarily by the

(1-3). “activation-synthesis” hypothesis, is

The “activation-synthesis” model (4) reductive and not consistent with various

later proposed a first systematic attempt to research data.

explain the causes of dream bizarreness The paper, after an attempt to define

after Freud’s initial hypothesis. This model the term “dream bizarreness”, is structured

was based on the neurobiological events of as follows: Theoretical Models (Part I),

REM sleep and opened a new perspective Measuring Dream Bizarreness (Part II),

to investigation. However, it automatically Empirical Data and Implications (Part III),

invalidated the psychoanalytic approach and Conclusions.

and therefore excluded any sort of analysis

of psychological or motivational DEFINING DREAM BIZARRENESS

determinants. At the same time the

cognitive-psychological approach to According to the Webster’s New

dreaming processes (5,6) was limited to Collegiate Dictionary, there are two

analysing dream bizarreness generation features that define the word “bizarreness”:

mechanisms (i.e., “how”) rather than its 1.Improbability (strikingly out of the

possible reasons and causes (i.e., “why?”). ordinary) and 2.Unusualness, oddness,

Therefore, investigations on the causes of extravagance. Several terms have been

dream bizarreness were restricted to the used in literature to describe bizarreness,

neurobiological level alone. for example, “distortion from reality”,

Still according to the more recently “metamorphosis”, “implausibility”, but

revised versions of the “activation- many authors agree that the concept of

synthesis” hypothesis, dream bizarreness bizarreness includes both: a) Impossibility,

can be fully explained by the particular and b) Improbability and/or oddness

Acknowledgments: I am grateful to Dr. Vincenzo Natale for compared to “common daily experiences”.

critical reading and constructive comments on the earlier The first dimension includes those

version of this manuscript.

situations that are impossible from a

Address reprint requests to: Dr. Claudio Colace, Via Luigi physical and/or logical point of view; the

Volpicelli, 8, 00133 Roma, Italy second dimension implies statistical

Phone: 3336148977

e-mail: claudio65@infinito.it improbability.

Sleep and Hypnosis, 5:3, 2003 105

Dream Bizarreness Reconsidered

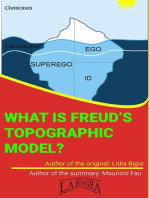

PART I: THEORETICAL MODELS phase of sleep “dreaming is the cognitive

by-product of a physiological state, REM

Psychoanalytic theory sleep” (14, p. 202). The original theory

stated that bizarreness is the result of a

According to psychoanalytic theory, temporally random and non-cognitive

dream bizarreness is an expression of a input from the brainstem (PGO spikes)

motivated effort to disguise unconscious and that dreams are merely the product of

wishes that are unacceptable to the “the best of a poor job” that the forebrain

conscience. The Ego and Superego makes to give sense to this random

defensive mechanisms are responsible for bombardment (forebrain synthesis) (4).

this effort to disguise latent dream Later on, it was suggested that the

contents. For example, children do not aminergic demodulation found in REM

dream bizarre dreams because they have sleep (or the lack of the inhibiting

not yet developed the superego which influence of norepinephrine and

enables these defensive changes of latent serotonin) causes defects in cognitive

dream contents (i.e. psychical censorship functioning (e.g. attention, memory, etc.)

functions) (17-21). In adults, bizarreness during forebrain synthesis, which

may be present in direct relation to the contributes to dream bizarreness (7,14,23-

state of the individual’s superego at 24). More recently, Hobson and others

particular moment in time (19). The proposed an updated version of the

psychoanalytic theory even classifies “activation-synthesis” hypothesis,

dreams according to bizarreness features. incorporated in a general brain/mind

Dreams may be as follows: model called AIM (9-10,12-13). According

to the AIM model, sleep and waking

a. “Sensible, plausible and without thought vary in function of three

oddities” - these sort of dreams lack any kind parameters: Activation level (A), Input

of “censorship” and dream-work activity; sources (I) and information-processing

b. “Sensible and consistent in itself but Mode (M) (i.e., the aminergic to

odd compared to common life”; cholinergic neuromodulation rate). REM

c. “Senseless, inconsistent and bizarre”; sleep is hypo-aminergic (compared to

waking state) and hypercholinergic. As in

Types b and c show a moderate and high the previous version, this model claims

degree, respectively, of “censorship” activity that dream bizarreness is due to an

(17). In Freud’s view, dream bizarreness is alteration of cognitive functioning caused

not an invariant property of dreams, as by the shift from a high level of aminergic

there are dreams that are typically non- neuromodulation during waking state to a

bizarre (e.g., young children’s dreams, and low level of same during REM sleep.

adult dreams directly engendered by the In Hobson’s view, dream bizarreness is

frustration of vital needs) (19,22). Bizarre a constant formal property of all dreams.

elements are psychologically meaningful, Bizarreness in itself has no particular

and dreams do have a meaning. psychological significance. It is

Motivations play an important role in this motivationally neutral and its

model, while other models reviewed give interpretation is gratuitous and probably

little relevance to them. hasty. Dream is inherently meaningless–a

state of the mind similar to delirium or

Neurobiological approach insanity (7,12,14,25-27).

“Activation-synthesis” hypothesis “Reverse learning” theory

This model ascribes dream bizarreness According to the “reverse learning”

exclusively to the unique neurobiological theory, dreaming and bizarreness are

conditions of the brain during the REM merely the result of the effort to erase from

106 Sleep and Hypnosis, 5:3, 2003

C. Colace

memory redundant associations or differences in the frequency of

“parasitic” thoughts (i.e., information bizarre/realistic dreams.

causing an overload in the memory

system) during REM sleep. In other words, Cognitive approach

we dream to forget, or to reduce fantasies

in the waking state. Random PGO spikes The cognitive approach assumes that

impinge on the neocortex, resulting in the dreaming is probably distributed along all

erasure, or “unlearning”, of false sleep stages (particularly–but not limited

information. As in Hobson and McCarley’s to–the REM and 2-NREM stage) and that

theory, in this model too random there is a common generative system for

subcortical PGO activity plays an dreaming and waking fantasies. This

important role for bizarreness. Dream is approach is principally interested in

inherently meaningless (15,28). studying dream production processes.

Seligman and Yellen’s theory Foulkes’s cognitive model

This model is based on “activation- Foulkes (5-6) indicates three

synthesis” hypothesis and on previous components in dream production: the

studies that had found a relationship input, i.e. the activation of memory units,

between tonic/phasic activities in REM their processing, known as “planner”, and

sleep and some aspects of dream mentation the output, i.e. conscious organisation.

(29-31). Seligman and Yellen (16) The dream is an attempt to give a plausible

suggested that dreaming consists of three sense to input information. In Foulkes's

elements: (i) periodic, unrelated visual view this attempt is generally successful.

episodes (REM burst), (ii) emotional However this dream production

episodes, and (iii) the cognitive synthesis of mechanism may be disturbed by the

both of the episodes above during REM presence of memory units with a higher

quiescence. The bizarreness and and more impinging level of activation

discontinuity found in REM dreams are due which the planner cannot exclude from

to the “visual burst” (discharges of eye processing. This event translates into the

movements) that supposedly cause presence of thematic changes (i.e.,

intrusions of inconsistent and discontinuity) and bizarre elements.

discontinuous images in the dream plot. Therefore bizarreness is considered an

The authors suggest that there are two exception rather than the rule. Indeed

separate forms of visual information/ dream Foulkes, based on the results of previous

imagery. The first, generated by bursts, is studies, suggests that the content of

more vivid and disjointed from the representatively sampled dreams (REM

underlying plot while the second, generated dreams) of both adults and children are

by cognitive synthesis, is less bizarre. As in generally realistic and ordinary, rather than

Hobson and McCarley’s model, Seligman fantastic and bizarre (32-35).

and Yellen attributed bizarreness to random

PGO activity (PGO spikes are commonly Antrobus’s General Cortical Activation/

associated with visual bursts) and therefore Thresholds (GCAT) model

to the difficulty in finding a sense in visual

bursts. However, the authors argued that According to Antrobus and colleagues,

their model also accounts for the banality bizarre mentation is the product of two

and realism of certain dreams (32). In other factors: cortical/cognitive activation and

words, while bizarre dreams are due to the level of environmental stimulation (or

visual burst activity, realistic dreams are due auditory thresholds) (36-41, Klinger’s

to a successful cognitive integration. study as cited in 39,42). Reinsel et al. (39)

Furthermore, individual differences in found that bizarreness is maximal in

individual cognitive styles could explain the conditions of high to moderate

Sleep and Hypnosis, 5:3, 2003 107

108

Table 1. Current models for dream bizarreness: Questions about dream bizarreness

Psychological Neurobiological Approach Cognitive Approach

Dream Bizarreness Reconsidered

Psychonalytic Activation- Reverse - Seligman and Foulkes’s Antrobus’s Hunt’s

Questions about dream bizarreness synthesis learning Yellen’s theory cognitive (GCAT) model phenomenological

hypothesis theory model perspective

Bizarreness is an invariant property no yes yes no no no no

of dreams

Bizarreness is exclusive to dream mentation no yes yes yes no no no

A generative system of dreaming and waking yes no / no yes yes yes

imagery, including bizarreness, is common

Bizarreness is present even when PGO / no no no / yes /

activity is notably reduced

Bizarreness is explained exclusively by / yes yes yes no no no

neurobiological events of REM sleep

Bizarreness has a psychological meaning yes no no no no no yes

Influences of motivations on dream yes no no no no no yes

bizarreness production

Sleep and Hypnosis, 5:3, 2003

C. Colace

cortical/cognitive activation when cognitive confusion (e.g., deficiencies in

external stimulation is minimal (i.e., REM memory and reasoning). Vice versa,

sleep and relaxed waking). REM dreams dreams of Freud’s and Jung’s collections

are not specifically more bizarre than any were characteristically bizarre. This

other form of thought when the approach does not consider bizarreness an

environmental conditions and the length invariant property of dreaming. Bizarreness

of the dream report (i.e., rate of cognitive is of great importance as an evidence of

activation) are under control. For creative symbolic imagination (visual-

instance, the authors noticed that NREM spatial processes) and has a metaphorical

dreams happen to be more bizarre in significance. In Hunt's view, dream

individuals with high activation levels bizarreness should be interpreted from

during NREM sleep (42). In addition, several different levels of analysis and not

Reinsel et al. show that bizarreness has from a merely physiological standpoint.

many dimensions that can differentiate

the quality of bizarre mentation across PART II: MEASUREMENTS

sleep and waking conditions. Thus, the

types of bizarreness depend on the At the beginning of the 1960s a few

variations of the two parameters above: authors attempted to measure the

waking mentation bizarreness (i.e., frequency of bizarre elements in dream

discontinuity) is due to external stimuli contents by means of objective indicators.

disrupting ongoing mentation (in Reinsel Retrospectively, we can see now that the

et al.’s study (39) relaxed waking was terminology used by these scales of

interrupted at varying intervals); while contents was influenced by the then

bizarreness in REM dreams is associated prevailing theories. The measurement

with the more genuinely “strange” nature created in the 60’s and 70’s used terms like

of the images (i.e., improbable or “distortion”, “metamorphosis”, “primary

impossible identities). Improbable process thinking”, reflecting psychoanalytic

combinations (bizarre elements concepts (e.g., “censorship”, “dream-work”,

regardless of context) increase and are etc.). On the other hand, after the

equally prevailing in relaxed waking development of neurobiological and

(without stimuli) and in dreams. cognitive approaches, terms such as

“discontinuities”, or “improbable

Phenomenological perspective combinations”, was clearly influenced by

concepts like “random activity in the

Hunt (43-44) elaborated a memory system” or “cognitive deficits” etc.

“phenomenological classification-ratings

system for formal anomalies in the The various scales of bizarreness may

dreaming experience” (see Table 2) and be categorized as follows:

analyzed different samples of dream

reports. In particular, laboratory dreams, • general scales: these provide a

home dreams, the “most fantastic” and the qualitative ranking of general classes of

“most realistic” of home dreams, and bizarreness (e.g., discontinuity,

dreams collected by Freud and Jung. In incongruity, etc.) (see Table 2);

Hunt’s view, “normative dreams” (i.e., • analytical scales: these provide a

laboratory and home dreams), albeit largely qualitative ranking of more specific

realistic in content and plot (in the sense kinds of bizarreness previously defined

that they reproduce typical waking by the author (e.g., “changes in sex and

situations and capacities), may show identity”, “monsters”, etc.) (see Table 3);

aspects of bizarreness that can be • global scales: these rank dreams using

assimilated to a mild clinical delirium, ordinal scales (e.g., various types of

namely: visual intrusion (e.g., visual bizarreness are considered together

transformations of form and setting) and without distinction in order to assign a

Sleep and Hypnosis, 5:3, 2003 109

Dream Bizarreness Reconsidered

Table 2. Bizarreness - “General” content scales

Scale Name Authors Brief Description

Scoring Reactive Rychlak & Brams (1963) (3) This scale scores the unusual content compared to

Content common expectation. Five categories: location,

actors, action, mood terms, implements.

Salience Cohen ’s study (as quoted in Salience is defined by 8 scales. Bizarreness is one of

Winget & Kramer, 1979) (45) these. Dreamer scores bizarreness as follows: settings

(objects, space) and events (behavior, experiences)

may be, 0-realistic likely, 1-unlikely, unexpected, but

possible, 2-impossible, ridiculous.

Discontinuities. Reinsel et al. (1992) (39) Discontinuities: when a part of mentation is

Improbable inconsistent with other parts according to common

combinations. daily experiences; Improbable combinations (e.g.

Improbable winged men); Improbable identities (e.g.

identities impossible or changing identities).

Classification- Hunt (1982) (43) Dimensions/changes: a. Competence functions,

ratingsystem b. performance (e.g. reasoning,memory attention),

of formal c. State of consciousness, d. Interpersonal relation

anomalies and personality identity. These dimensions are

divided into three stages: 1. Hypersensitivity to

“ordinary” subjective aspects of experience. 2.

Changes in awareness (e.g. derealization). 3. Specific

anomalies in each dimension.

Dream Hobson et al. (1987) (27) Two-stage scoring system. Stage 1 identifies

bizarreness Hobson (1988) (7) items as bizarre if they are physically impossible

or improbable (e.g. plot, characters, thoughts of

dreamer, etc.); Stage 2 characterizes items as

showing discontinuity, inconsistency or uncertainty.

Bizarre contents Cipolli, Bolzani, Cornoldi, De Bizarreness is defined according to the following

Beni, and Fagioli (1993) (46) criteria: a. physical impossibility, b. physical

implausibility c. behavioral implausibility, d. functional

implausibility and e. incongruity of dialogue, thought

and feeling with respect to the situation.

Continuity and Sutton, Rittenhouse, Pace- This scale attempts to measure continuity and

discontinuity Schott, Stickgold, and Hobson discontinuity in visual attention using the graphs

(1994) (47) theory. The sequence and developments of narrative

reports are presented in hierarchy graphs. Discontinuities

in temporal order are quantified by imposing a

weighted value to each transition within the graph.

Discontinuities Rittenhouse, Stickgold, and This scale analyzes the "mode" of discontinuities

Hobson (1994) (48) in settings, character and object. For example,

we can observe the "Insertion" (sudden appearance)

or "Removal" (sudden disappearance) of an

object and character or "Shift" (initial) or

"Return" (subsequent) in setting and plot.

Content Revonsuo & Salmivalli Dreams are classified into a two-stage scoring:

Bizarreness (1995) (49) 1. Element identification (14 categories, e.g. self,

Scoring actions, emotions) and 2. Content bizarreness

scoring: A. Non-bizarre element (consistent with

waking reality), B. Incongruous element (e.g.

impossible in waking reality), C. Vague element,

D. Discontinuous element.

Bizarreness Colace & Natale (1997) (50) This scoring scale classifies bizarreness as follows: 1)

Bizarre Elements (4 types), a. Improbable or

impossible characters, b. metamorphoses, c.

improbable or impossible actions/inappropriate roles

d. improbable or impossible objects; 2) Script

bizarreness (4 types): a. improbable or impossible

(physical) plot, b. improbable or impossible (logical)

plot, c. plot discontinuity, d. improbable or

impossible settings.

Bizarreness Bosinelli (1999) (51) Bizarreness is classified as: a. improbability, b. oddity

or a+b. c. physical impossibility, d. logical impossibility

or c+d.

110 Sleep and Hypnosis, 5:3, 2003

C. Colace

Table 3. Bizarreness - “Analytical” content scales

Scale Name Authors Brief Description

Bizarre Elements Domhoff & Kamiya (1964) (1) This scale identifies 3 general classes of

bizarre elements: metamorphoses (4

categories), unusual acts (2 categories),

magical occurrences (4 categories).

Distortion from reality Sutcliffe, Perry, & Sheehan, This scale scores atypical aspects with

(1970) (52) respect to the common experience

occurring in real world. Samples of

distortion considered are: changes in sex

and identity, false belief, implausible

behavior of an agent, alteration of typical

appearances or dimension of an agent, etc.

Setting and Hall & Van de Castle (1966) Metamorphoses of characters: changes in

characters distortion (53) sex, identity, or age. Changes from human

into animal or vice-versa. Setting

distortion: familiar settings indicated by

the dreamer have an element of peculiarity

or incongruity insofar as they differ from

the way the dreamer knows the setting to

be in his waking life.

Dream Bizarreness McCarley & Hoffman Dream bizarreness is divided into

(1981) (54) three major groups: a. animate characters,

6 kinds (e.g. monsters, alien beings),

b. inanimate environment, 3 kinds (e.g.

violation of physical laws), c. dream

transformations, 4 kinds (e.g. scene shift).

global score) (see Table 4); PART III: EMPIRICAL DATA AND

IMPLICATIONS

These three types of scales measure the

A. Frequencies

quantity of dream bizarreness in different

ways: while general and analytical scales Bizarreness in REM dreams

score the frequency of bizarreness of

dream reports in single units or elements Several studies have attempted to report

(e.g., action or setting), global scales the frequency of bizarre REM dreams;

frequently score dream bizarreness by however, due to the different scales used,

considering the dream as a whole. the conclusions reached were conflicting.

A common problem associated with Most of these studies agree in that

many measurements is that some bizarre bizarre dreams are very frequent, about

elements may be estimated differently 74% of REM dream reports (46,50,54,

without the help of the dreamer’s own 60,62-67) (see Table 5 and 6).

judgments (e.g., improbability and Less frequently, certain authors have

implausibility in the light of their own suggested that there are notably lower

personal waking reality) (49, 60). For percentages of bizarre REM dreams;

example, Zepelin (60) compared the however, they generally used a different

dreamer’s and the judge’s bizarreness definition of bizarreness (see Table 5) (32-

ratings and concluded that the lack of 33). For example, in Snyder's study, an

knowledge about the dreamer’s waking element being "extremely unlikely from

experiences may lead the judge to the standpoint of waking reality" and yet

exaggerate his/her rating of bizarreness. conceivable is not evaluated as bizarre

Future research should specify whether (p.146). Dorus et al. (33), who found little

the bizarreness scale adopted includes the bizarreness in REM dreaming, used a

dreamer’s contribution or not1. content scale substantially different from

1

For the definitions and scales of bizarreness see also Hobson et al. (27) and, Bonato, Moffitt, Hoffmann, Cuddy & Wimmer (61).

Sleep and Hypnosis, 5:3, 2003 111

Dream Bizarreness Reconsidered

Table 4. Bizarreness - “Global” content scales

Scale Name Authors Brief Description

Distortion Foulkes & Rechtschaffen’s Distortion is measured as follows: 1 extremely

study (as quoted in Winget distorted , 2 quite distorted, 3 fairly distorted,

& Kramer, 1979) (45) 4 somewhat distorted, 5 slightly distorted, 6 not

distorted at all.

Dream ratings Gooudenough, Lewis, Shapiro, A three-point scale of bizarreness/ rationality:

(bizarreness) and Sleser’s study (as cited in 1= “most bizarre” (e.g. strange objects or events),

Winget & Kramer 1979) (45) 1/ = unusual elements or confused combinations of

2

ordinary elements, 0 = dreams with ordinary elements.

Regressive dream Vogel, Foulkes, & Trosman’s This scale classifies dreams as follows:Nonregressive

content study (as quoted in Winget content dreams = plausible, realistic, consistent and

& Kramer, 1979) (45) undistorted dreams. Regressive content dreams =

1 or more bizarre categories such as, bizarre

sequence of images, inappropriate or distorted

images, magical omnipotent thinking, etc.

Child rating scales Foulkes, Pivik, Steadman, Dreams are classified into four levels: level 0 – no

/ distortion Spear, & Symonds (1967) distortion (realistic recreation or anticipation of

(55) upcoming event), 1- no distortion (plausible and

very probable event), 2- slight distortion (plausible

but not probable), 3- considerable distortion

(content is neither plausible nor probable but

contains certain elements of reality) 4- major

elements are neither plausible nor probable.

Scoring dream Koulack’s study (as quoted in Dream bizarreness: this scale refers to the extent of

dimensions Winget & Kramer, 1979) (45) “unreality”. 1. Dream which is entirely true to life.

2. Dream containing both real and unreal

elements. 3. Dream which is totally unreal.

Vivid fantasy Weisz and Foulkes (1970) (56) This scale measures the feeling of unreality (i.e.,

imagination and distortion) coupled with intensity

of experience (dramatization) (A 5 - point scale).

Primary process Auld, Goldenberg, & Weiss Starting from the psychoanalytic concept of

thinking (1968) (57) primary process, the authors focus on evaluating

the “mode of thinking”. A 7- point scale: 1) logical

vs. 7) bizarre and illogical thought.

Classification of Dorus, Dorus, & This scale measures the novelty of elements (e.g.

novelty in Rechtschaffen (1971) (33) setting, objects etc.) with respect to the experience of

dreams each dreamer. 1. the dream element is an exact

replication of something previously experienced vs.

6. the dream element was not previously experienced

and it is extremely unlikely that such an element

could occur in the dreamer’s experience

Chicago sleep Rechtschaffen, Watson, The experimenter asks: How unfamiliar, strange, or

mentation scales Wincor, and Molinari’s study distorted was the very last experience in terms

(as quoted in Winget & of your waking experience? 1. almost exactly like

Kramer, 1979) (45) my waking experience vs 6. new and unfamiliar

and very unlikely to occur in my waking life.

Implausibility Breger, Hunter, & This scale classifies dreams as follows: 1- quite

Lane’s study (as quoted in plausible (something that could well happen to

Winget & Kramer, 1979) (45) the dreamer) vs. 5-bizarre (something that is so

extremely unreal or fantastic that would be

unusual even in a dream report).

Dream distortion Zepelin’s study (as quoted This scale measures the strangeness of dream

in Winget & Kramer, contents compared to waking experience. Level 0 =

1979) (45) the event of dream closely resembles recent waking

experience vs level 5 = major aspects of the dream

are impossible (i.e. combination of illogical or

improbable elements).

Distortion/ Colace, Violani & Solano The authors attempt to formalize the original

Bizarreness (1993) (58) classification of dream bizarreness in Freud’s view.

Colace & Tuci (1996) (59) Dreams are classified as follows: 1 = “sensible,

plausible and without strange elements”, 2 =

“sensible, consistent in themselves but odd

compared to common life”, 3 = “senseless,

inconsistent and bizarre”.

112 Sleep and Hypnosis, 5:3, 2003

C. Colace

Table 5. Percentages of bizarre dreams in REM sleep

No of Bizarre

Studies Dreams REM Dreams Measurement

McCarley & Hoffman (1981) (54) 104 67 % reports containing at least one

element of bizarreness (e.g. monsters,

scene shift)1

Zepelin (1989) (60) 322 91 % reports containing at least a number of

elements not true to life (scores:

“perfectly true to life” vs. “not at all

true” (ratings 1-6)

Zito, Cicogna & Cavallero 183 63 % reports containing at least one bizarre

(1992) (67) element (physical and/or logical

impossibility, or improbability

(according to dreamer’s experience)

Cicogna, Cavallero & 27 67 % reports were scored as “plausible”

Bosinelli (1991) (63) or “implausible” according to waking

standards.

Cavallero et al. (1992) (62) 50 66% reports were scored as “plausible” or

“implausible” according to waking

standards.

Cipolli et al. (1993) (46) 110 79 % reports containing bizarre elements

(e.g. physical impossibility, behavioral

implausibility, etc.)

Colace & Natale (1997) (50) 50 82 % reports containing at least one bizarre

feature (e.g. improbable or impossible

characters, actions, roles, etc.)

Cicogna et al (1998) (64) 1442 84 % reports were scored as “plausible” or

“implausible”

Cicogna et al (2000) (65) 20 75 % reports containing one or more

impossible or improbable elements

according to the subject’s waking

experience

Natale & Esposito (2001) (66) 342 70 %3 reports containing one or more

impossible or improbable elements

according to the subject’s waking

experience

Snyder (1970) (32) 635 L: 20-35% very improbable elements with respect

M: 5-15% to waking reality but yet conceivable

H: 2-7%4 are not necessarily evaluated as bizarre

Dorus et al. (1971) (33) 119 16 % dreams with elements that are a

replication of something previously

experienced, but with major changes

from the original (level 3 of 6)5

1

See table 3 for detail

2

So, St 2, REM.

3

Average score REM 1, 2, 3, 4, cicle

4

L = Low, M = medium and H = high bizarreness

5

See table 4 for detail

more common bizarreness scales (see dream bizarreness is not an invariant

Tables 2-4). formal property of all dreams. About 25%

From a theoretical point of view, these of REM dreams among adults are not at all

data are not consistent with the hypothesis bizarre. In addition, non-bizarre dreams

that REM dreams are generally realistic occur very frequently in young children

compared to dreams derived from a (see below). The non-invariant nature of

psychoanalytic setting or from a home bizarreness in REM dreams cannot be

setting (70). Actually, as stated above, REM easily explained through approaches that

dreaming often reveals bizarre features. On regard bizarreness as intrinsic to the

the other hand, it may be observed that neurobiology of REM sleep (7,15).

Sleep and Hypnosis, 5:3, 2003 113

Dream Bizarreness Reconsidered

Table 6. Percentages of bizarre dreams across sleep stages

Sleep Stages Bizarre Dreams / Range Average STUDIES

Sleep onset min 33% - 43% max 38 % Cicogna, Cavallero & Bosinelli (1991) (63);

Cicogna et al (1998) (64); Zito, Cicogna &

Cavallero (1992) (67); Cicogna et al.

(1996) (68).

NREM, stage 2 47% - 79 % 61 % Cicogna, Cavallero & Bosinelli (1991) (63);

Cicogna et al (1998) (64); Natale &

Esposito (2001) (66); M.Bosinelli (personal

communication).

NREM, stages 3-4 and 4 48% - 54% 51 % Cavallero et al. (1992) (62); Cicogna et al.

(2000) (65); Colace & Natale (1997) (50);

M. Bosinelli (personal communication);

Natale (2000) (69).

REM 63% - 91% 74 % Cipolli et al. (1993) (46); Colace & Natale

(1997) (50); McCarley & Hoffman, (1981)

(54); Zepelin, (1989) (60); Zito et al. (1992)

(67); Cicogna, Cavallero & Bosinelli (1991)

(63); Cavallero et al. (1992) (62); Cicogna

et al (1998) (64); Cicogna et al. (2000)

(65); Natale & Esposito (2001) (66).

Comparing bizarreness in REM and support the hypothesis that the

NREM dreams underlying cognitive processes of dream

production mechanisms could be the

Empirical evidence suggests that the same through all sleep stages. However

original “REM sleep=dreaming” hypothesis this dream-generation system may be

and the rigid REM/NREM dichotomy associated to the quantity of mnestic

needs to be completely revised. In activation that is different between REM

particular, researchers have found that2: and NREM sleep (i.e., different levels of

system engagement) (85);

• REM sleep, in itself is not a sufficient

condition for dreaming. Foulkes has • In agreement with the above,

demonstrated that in children aged 3 to 5 Solms’neuropsychological studies

REM dreaming is relatively absent; i.e. the suggest that REM sleep and dreaming

presence of REM sleep is not a guarantee are dissociable states, controlled by

of concomitant dream activity (34-35,73); different brain mechanisms (86-88).

Thus, dreaming is preserved even when

• REM sleep is not a necessary condition a major damage to pontine brainstem

for dream production. Several studies eliminate REM sleep. Therefore, dream

have shown that dreams can occur mentation can occur without REM

during all the sleep stages sleep. Furthermore, forebrain damage

(6,62,63,67,70,74-83). In particular, (dopamine circuit) would stop

the work of the research group of the dreaming but would not affect REM

Sleep and Dream Laboratory of the sleep. Consequently, dreaming can be

Bologna University Department of initiated by the forebrain mechanisms

Psychology has shown that dream-like regardless of REM state.

mental activity is present also in slow

wave sleep (SWS) (from a physiological These results open the field to

point of view this sleep phase differs investigations on bizarreness in NREM

greatly from the REM phase) dreaming as well. As a further analysis of

(65,66,69,72,84). These studies dream bizarreness the following two

2

On the REM//NREM current debate see Nielsen (71) and Cavallero (72)

114 Sleep and Hypnosis, 5:3, 2003

C. Colace

questions should be answered to: measurement used for bizarreness. For

example, by applying “global” (ordinal)

1. Is bizarreness an exclusive feature of bizarreness scales the REM dreams

REM dreaming? observed are more bizarre than NREM

2. Are REM dreams characteristically dreams, while “general” (qualitative)

(qualitatively and quantitatively) scales applied to the same dream reports

more bizarre than NREM dreams? do not lead to the same results (39,92).

The data found in literature demonstrate • Correlation between length and

that bizarreness is not exclusive to REM bizarreness of dream reports. The well-

dreaming, as bizarre dreams are frequently known correlation between the length

present in NREM sleep. In particular, the of dream reports and their bizarreness

percentage of bizarre dreams is about 38% (36,54,57,93) may make the

in sleep onset, about 61% in NREM stage 2, differences between REM and NREM

and about 51% in stages 3 and 4 (SWS) (see dreams bizarreness scores less clear

Table 6). These results suggests that bizarre (REM dreams are frequently longer).

mentation is not state-specific of REM sleep, Thus, the difference between REM and

and its distinctive neurobiological events NREM stage 2 dream reports vary

(PGO activity and aminergic demodulation), according to whether dream length is

are not a necessary condition for bizarre controlled or not (39).

dreaming.

It could be hypothesized that there are In general, authors suggesting that

other causes of bizarreness, different from REM–NREM mentation differ only in

the ones assumed in REM sleep. Thus, the quantitative terms but not qualitatively (i.e.,

models that base their explanation of the mechanisms of dream production are the

bizarreness on REM neurobiological events same across sleep stages) usually compare

do not account exhaustively for the REM and NREM dreams after dream report

explanation of dream bizarreness in other length is controlled and find no difference

phases of sleep. (39,66,69). These authors suggest that the

The followings studies have compared heightened frequency of bizarreness in REM

directly the frequency of bizarre dreams in dreams is the result of the increased cortical

REM and NREM sleep and might activation (memory systems included) found

contribute to providing an answer to the in REM sleep (36,81). In other words, they

second question. suppose that REM dreams are longer and

REM vs. sleep onset. Several studies more bizarre because the underlying

underlined the low frequency of bizarre cognitive processes operate on higher levels

dreams in sleep onset stage compared to REM of engagement than in NREM stage 2 sleep

sleep (63,64,67,76,82,89-91). A few authors conditions.

have suggested that the contents of mentation On the other hand, authors claiming

at sleep onset are still strongly related to the that the correlation between bizarreness

waking state, which supposedly limits the and length does not justify the differences

presence of bizarreness (66,78). between in REM and NREM dream

REM vs. NREM, Stage 2. The studies bizarreness, (wrongly assumed only in

that have compared dream reports for quantitative terms), maintain that the

bizarreness in REM and NREM stage 2 are difference remains even when length is

controversial, and certain methodological controlled, hence REM dreams are always

aspects should be viewed in deeper detail more bizarre than NREM, stage 2,

before interpreting their results. (12,92,94). These authors have

interpreted these results in support of the

• Measurements. The differences found activation-synthesis model.

between REM and NREM Stage 2 The studies that analyzed REM vs.

dreams depend much on the NREM stage 2 differences in dream

Sleep and Hypnosis, 5:3, 2003 115

Dream Bizarreness Reconsidered

bizarreness are still numerically insufficient wakeful mentation may contribute to clarify

in order to draw any sort of general whether bizarreness is exclusive to

conclusions. The evidence that emerges dreaming or not, and whether REM dreams

from previous studies is insufficient to are typically more bizarre than waking

conclude that REM dreams are more mentation (i.e. relaxed wakefulness,

bizarreness than NREM stage 2 dreams. "simulated dreams," daydreaming).

REM vs. NREM, stages 3 and 4. Very few The findings in literature reveal that

studies have compared REM and Stage 3 bizarreness is also undoubtedly present in

and 4 sleep mentation for bizarreness scores. relaxed wakeful mentation (97-99).

Cavallero et al. (62) used a measurement of Furthermore, other studies have found

Plausibility/Implausibility and found no that relaxed wakeful mentation and

significant differences in the frequency of "simulated dreams” are equally–or perhaps

“plausible” dreams between REM and SWS even more–bizarre than REM dream

sleep (slow wave sleep). Colace and Natale reports (39,100). For example, Reinsel et

(50) compared REM and SWS sleep al. (39) compared REM dreams, NREM

mentation (Dreams Data Bank, Bologna stage 2 dreams, and relaxed wakeful

University, Department of Psychology, 95) mentation (subjects were reclining in a

and found that REM dream reports were darkened room) and found that there is a

significantly more bizarre than SWS dream greater quantity of bizarreness in waking

reports for “script bizarreness”, but no thoughts. The authors suggested that these

significant differences were found when results were consistent with the GCAT

looking at “bizarre elements” (see Table 2 for model, according to which the higher

detail). It is interesting to note that when cortical activation level during waking

dream length was controlled, all REM/SWS state (compared to REM and NREM sleep)

differences disappeared. Recently, Cicogna might increase bizarre contents.

et al. (65) found no significant differences in The studies based on “home dreaming”

“implausibility” (one or more impossible or led to controversial results. Williams et al.

improbable elements) between REM and (99) compared “home dreaming” reports

SWS mentation. to waking fantasies and showed that home

Although the comparison between dreams were significantly more bizarre.

REM and Stage 3-4 sleep mentation The authors claimed that their results were

should be examined more closely, the data consistent with the “activation synthesis”

available seem to point to the conclusion hypothesis. Subsequently, Strauch &

that there are not significant differences in Lederborgen (101) obtained comparable

bizarreness between these two stages. results. On the other hand, Carswell and

In conclusion, previous researches have Webb (102) compared home dreams and

found no clear differences in bizarreness “artificial dream reports” (i.e., subject-

between REM and NREM dreaming (with developed summaries of a random

the exception of sleep onset dreaming). succession of photographs) and found no

There is not enough evidence to support difference in the rates of “implausibility”

the hypothesis that REM dreaming is and bizarreness used (“unusual acts” and

typically more bizarre than NREM “magical occurrence”). The only category

dreaming. The methodological issues of found to be more frequent in home

the uniformity of the measures used, and dreams was the “metamorphosis”.

of whether it is appropriate or not to Since studies have revealed that there

correct report length are still open in were at least no significant differences

comparative analyses between REM and between REM dream reports and waking

NREM dreaming (96). mentation, the great quantity of bizarreness

found in home dreams by certain authors

Bizarreness: dreams vs. waking mentation could be due to the effects of a better recall of

bizarre elements after a longer time span since

The studies on bizarreness in relaxed dream generation (46). It is clear, from the

116 Sleep and Hypnosis, 5:3, 2003

C. Colace

studies reviewed, that there is no distinctive data do not support this hypothesis:

physiological property of REM sleep that can

explain bizarreness alone, because • bizarreness is also present in NREM

bizarreness also occur in waking mentation dreams where PGO activity is notably

and because REM dreams do not seem to be reduced (39);

characteristically more bizarre than waking

• there are insufficient data to support the

fantasies. Vice versa, these results are more

concept of random and non-cognitive

consistent with those models that assume

nature of pontine brainstem activation.

qualitatively common processes during

In fact the beginning of eye movement

dreams and waking fantasies.

(EM), its associated PGO activity, and the

B. Neurophysiological and resulting dream imagery might not be

neurobiological factors totally independent from the prior

cortical/cognitive activity. In other words,

Phasic events the cortex may have an important role in

initiating and creating the visual imagery

Several authors have focused on the of dreaming. (38,112-116)3;

phasic events of REM and NREM sleep and

on the parallel presence of bizarre • Solms (88) suggested that dream imagery

elements in dream contents (103-105). is not generated by the brainstem’s chaotic

Bizarreness seems to be related to REMs activation of the forebrain–on the

(Rapid eye movements) (106), with PIPs contrary, it is apparently built through

(Periorbital Integrated Potentials, the complex cognitive processes;

equivalent of PGO in humans) in REM and

NREM sleep (107-109) and with MEMA • various studies have shown that dreams

(middle-ear muscle activity) in REM and are meaningful rather than random

NREM sleep (110). However these data events. In particular, dream contents

were not always confirmed (111). are affected by gender, age, social status

While there is no evidence supporting and psychopatology (118-119,45).

that PGO spikes are a necessary cause of

bizarreness (see below) the possibility • the data from studies on memory

remains that, phasic neural events consolidation during REM sleep clash

(intrusion), in general and not only at with the hypothesis of random

PGO level, during REM and NREM sleep processing in memory system. Pavlides

may provide one source (i.e., correlate) of and Winson (120-121) in an single-

bizarre mentation. unit experiment with rats found that

hippocampal neurons (CA1 “place

PGO activity cell”), that had fired preferably in their

place fields during waking state, in

The hypothesis that dream bizarreness order to encode spatial information and

may be attributed to the nature of pontine committing it to memory, fired

PGO activity suggests that dream preferably in subsequent sleep states

bizarreness imagery might be due to: a) (REM/SWS). This result was replicated

non-cognitive (subcortical) and random in another study with three rats (122).

nature of eye movements and their Similarly, Skaggs and McNaughton

associated PGO spikes, and b) from the (123) found that the pattern of rat

fact that dreaming and dream bizarreness hippocampal pyramidal cells during

could consist of associations and memory sleep reflects the order in which the

units elicited from the forebrain in cells fired during earlier spatial

response to random inputs from the exploration in a waking state. These

brainstem (PGO) (i.e., random processing data imply the existence of a sort of

in memory system). Unfortunately, several orderly processing of the memory

3

On this topic see also Mancia (117)

Sleep and Hypnosis, 5:3, 2003 117

Dream Bizarreness Reconsidered

rather than a random activity during dreams, it has been found that young

sleep. In particular, Winson suggest children’s dreams are not bizarre at all (see

that in REM sleep types of memory that below);

are important for survival information On grounds of the above, aminergic

during waking state are selectively and demodulation is neither a necessary nor a

preferentially reprocessed (122,124). sufficient condition for dream bizarreness.

This group of data is not consistent Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex inactivity

with the models according to which PGO

random activation and its supposed Studies on dreaming with Positron

consequences in the memory system are Emission Tomography (PET) show which

the cause of bizarreness. Specifically, these parts of the brain areas are active and

studies show that PGO activity is neither a which are inactive during REM sleep. With

necessary nor a sufficient condition of this method, some authors have

dream bizarreness. More generally, these hypothesized that the deactivation of the

data clash with the concept of dreams as a dorsolateral pre-frontal cortex during REM

chaotic and random product. sleep, which causes cognitive deficits (e.g.,

short-term memory, orientation, etc.),

Aminergic demodulation would explain why dreams are so bizarre

and illogical (12, 23,127,132-136).

In Hobson’s view, the aminergic These approaches to the explanation of

demodulation of the brain in REM sleep REM dream bizarreness are inclined to

could be a cause of cognitive deficits that considering bizarreness as a constant

contribute to dream bizarreness, formal property; however, we have seen

compared to waking state where aminergic that this is not true.

neuromodulation is high (12,14,125). For

example, aminergic demodulation might Cortical/cognitive activation

predict an alteration in the strength of

associative links in memory (i.e., The hypothesis of Antrobus et al. (38-

hyperassociative character) that would 39,112), i.e. bizarreness is due to an

explain the bizarre character of REM overall increase in cortical and cognitive

dreaming (126). Recently this view has activation, appears to be backed by the

been suggested also by Gottesman (127- following data:

128) who claimed that the aminergic

demodulation in REM sleep (with the a) Individuals with high cortical

exception of dopaminergic neurons) could activation in NREM sleep have shown a

be responsible for unusual cognitive greater amount of “dreaming” while

functioning and for dream bizarreness. individuals with slow cortical activation

These hypotheses seem scarcely showed NREM mentation defined as

plausible, as long as we have seen that: “thought-like” (42);

b) Dream reports of the second half of

a) bizarreness is also present in waking night sleep (where it is supposed to be a

mentation and in NREM sleep, where greater cortical/cognitive activation) are

aminergic modulation is supposed to be generally more bizarre than in the first part

efficient (see above); (66,70,94,114,137-139);

b) recent studies suggest that certain c) Waking and REM mentation (states

cognitive abilities, e.g. attentional with higher activation), if report length is

processes, are not impaired during not controlled, may appear more bizarre

dreaming compared to waking (129-131); than NREM stage 2 mentation (39).

c) while, according to the “aminergic Based on these data, the bizarreness of

demodulation hyphotesis”, bizarreness REM dreaming could reflect persistent

should be a constant formal property of all cortical activation rather than specific

118 Sleep and Hypnosis, 5:3, 2003

C. Colace

mechanism of REM sleep. quite surprisingly, no implications of this

finding were elaborated for their own

Frontal-limbic structures theory of dream bizarreness (12,145).

Finally, some preliminary systematic

Based on clinic/anatomical studies, observations in young children’s dreams

Solms (86,88) hypothesized that the show that they are frequently a clear and

frontal–limbic structures (anterior easily understandable wish-fulfillment

cingulate gyrus, anterior and dorsomedial (142,150). From this point of view, dreams

thalamus, basal forebrain nuclei, and cannot be characterized as meaningless,

medial frontal cortex) would be implicated the result of random nerve cell activity (7)

in Freud’s “censorship” function. In fact or as a mere activity aimed at reducing

this region seems essential for the control spurious associations, fantasy and

and regulation of emotions and impulses, obsession (15). Studies on formal aspect of

and for the reality monitoring system children dreams are fully consistent with

through the inhibition of the motor system the psychoanalytic approach.

during sleep. When this region is

functioning normally, arousal stimuli of Personality development

dream processes are deflected towards the

perceptive system (i.e., dream-work, The psychoanalytic model predicts that

symbolic operation etc.); conversely, when children dreams are not bizarre because they

this region is damaged excessively have not yet developed the superego

frequent and intense dreaming is triggered. function that could permit the defensive

transformation of latent dream contents

C. Individual factors (17,19-22). Certain studies have found

indications consistent with this hypothesis.

Age For example, Foulkes (34) has shown that

dream “distortion” is correlated to “social

Various studies have shown that dreams comprehension” scores (Wechsler Test) (i.e.,

of normal children of preschool age are often development of moral norms, adjustment to

simple rather than bizarre, even if collected reality). Colace et al. (58,141,142) suggest

with different methodologies (family/non- that the appearance of bizarreness in

family interviewer) and/or in different children’s dreams seems more related to

settings (dream laboratory, home, school) measures of the “capacity to experience guilt

(34,58,59,140-145). The frequency of non- feelings” (i.e., differentiation of the super- ego

bizarre dreams is about 70%. These data function, interiorization of moral norms)

confirm previous anecdotal and quantitative than to descriptive/linguistic abilities.

observation on the simplicity of children’s Furthermore, in agreement with Foulkes’

dreams (146-148). Bizarreness seems to findings, these authors found that in children

occur more frequently starting from 5 to 6 of 3-6 years of age “social comprehension” is

years of age compared to dreams of younger correlated to scores of the “capacity to

children (34,58,142,149). experience guilt feelings” and that both these

These data suggest that dream variables are positively correlated with

bizarreness should not be considered as an measures of dream bizarreness (142).

intrinsic regular property of the dream

process. Indeed, in the light of children’s Waking creativity

dreams, it’s difficult to ascribe dream

bizarreness to a unique neurobiological Several empirical studies have strongly

condition. In particular, why do random supported the hypothesis of a positive

PGO activity and aminergic demodulation relationship between dream bizarreness and

not cause bizarre features in children’s waking creativity (151-157). In a critical

dreams? Hobson’s colleagues also found review of these studies, Wood, Sebba and

that children’s dreams are not bizarre, but, Domino (93) suggested that dream

Sleep and Hypnosis, 5:3, 2003 119

Dream Bizarreness Reconsidered

bizarreness might be primarily related to bizarreness was associated with well-

vocabulary knowledge than to waking adjusted/maladjusted (MMPI) scores.

creativity. According to Wood, Sebba and Carrington concluded that a high rate of

Domino, the dream reports of verbally dream bizarreness might, on the basis of

intelligent people obtain higher bizarreness further investigation, turn out to be at least

ratings only because they are longer, and an important index of the degree of

not because they contain a higher “density” maladjustment in the dreamer. It is also

of bizarre events. A similar result was found worth noting that dreams are more

by Livingston and Levin (158). unrealistic among children suffering from

However, at least three facts should be emotional disturbances (55). These results

mentioned in opposition to these are consistent with the psychoanalytic

statements: a) people with higher verbal view according to which the dreams of

creativity do not always have longer dreams maladjusted persons are generally more

(159), b) several studies have found that bizarre (quantitatively) than those of

non-verbal measures of imaginative ability normal persons (18).

rather than verbal ability are excellent

predictors of dream bizarreness (160-164), The results of studies on waking

c) certain authors suggest and maintain creativity and psychopathology converge

that, in observing the relationship between together towards the following statements:

bizarreness and creativity, to separate dream

length from bizarreness may be a • NREM PIPs activity (correlate of

questionable practice (43,96,164). bizarreness), that vary from one

In accordance with these data, individual to another, is more frequent

Hartmann’s group found that individuals in psychiatric patients and in

with “thin boundaries” property (i.e., individuals who show a greater

flexible, imaginative and creative imagination (correlates with dream

individuals) report more bizarre dreams bizarreness) (181-184);

than people with “thick boundaries”

property (i.e., solid, rigid and reliable • NREM PIPs activity seems more frequent

individuals) (165-169). in persons who have less control of over-

anxiety, fluid ego boundaries, less solid

Psychopathology indices sense of self , and with more imagination

(i.e., “thin boundaries” structure) rather

Several studies have given good than in persons with better control of

support to the relationship between dream anxiety, rigid ego boundaries and less

bizarreness ratings and the degree of imagination (i.e., “thick boundaries”

psychological disturbance of the dreamer structure) (182). We have seen that

measured with the MMPI test (total score “thin” persons are exactly those who

and/or scale of “hysteria” and Sc) dream a greater number of bizarre

(2,3,171). Other studies have observed dreams (see above).

that the dreams of schizophrenic patients

generally appear more bizarre (oddity, The data on the relationship between

implausibility) than those of normal dream bizarreness and waking creativity,

individuals (170,172-174). In addition, psychopathology degree, and types of ego

the dreams of the schizophrenic are boundaries structure, suggest that dream

frequently characterised as unrealistic bizarreness is substantially and not negligibly

(175-180). Carrington (170) compared affected by individual differences. All those

the dream reports of schizophrenic and models that ascribe dream bizarreness solely

nonschizophrenic individuals and showed to neurobiological events cannot explain the

that the dreams of the former were more effects of individual differences (Hobson,

bizarre than those of control subjects. Crick and Mitchison) or at least do not

Furthermore, in the control group, dream explain how can these variables reconcile

120 Sleep and Hypnosis, 5:3, 2003

C. Colace

with a neurobiological explanation. rat sleep suggest that during REM sleep the

processes in the memory system are orderly,

CONCLUSIONS rather than random.

Most of these data, conflicting with the

The activation-synthesis hypothesis “activation-synthesis” hypothesis, also

and its updated versions, that attribute question the two other neurobiological

dream bizarreness solely to the distinctive explanations of bizarreness, which are

neurobiological conditions of REM sleep, largely based on the concept of PGO activity

can be essentially rejected on the basis of and on the REM=dreaming equation (i.e.,

the data found in literature. the “reverse learning” theory and Seligman

This approach suggests that dream and Yellen’s model).

bizarreness is a constant formal property of all Apart from the evidence to the contrary at

dreams because it is intrinsic to REM sleep neurobiological level, there is another major

neurobiology, namely PGO random activity reason for reconsidering the neurobiological

and aminergic brain demodulation. approach to dream bizarreness: the data on

Moreover, as these neurobiological events are the relationship between dream bizarreness

not present in NREM dreaming and in and waking creativity, psychopathology and

waking mentation, bizarreness is supposed to types of ego boundaries structure, suggest

be exclusive and peculiar to REM dreaming. that dream bizarreness is substantially

These assertions are not supported by influenced by individual variables.

data. Indeed there is evidence that dream From this viewpoint, the studies on

bizarreness is a non-invariant, non-exclusive children’s dreams have been quite useful in

and not peculiar feature of REM dreaming. reconsidering dream bizarreness. In

Particularly, although REM dreams are particular, they have shown that: (i)

frequently bizarre in adults, there are also bizarreness is not present in early forms of

REM dreams that are not at all bizarre, and dreaming, (ii) bizarreness seems to appear

non-bizarre dreams have been often at around 5 to 6 year of age, and (iii) it

observed in young children. In practice, seems to be related to the development of

the neurobiological events of REM sleep moral norms.

are not a sufficient condition for the While the literature data do not seem

occurrence of bizarreness. consistent with the activation-synthesis

The literature shows that bizarreness is hypothesis and other neurobiological

present also in NREM dreaming and in approaches, they appear to be at least in

some waking mentation (e.g., relaxed part consistent with other alternative

waking, fantasies, etc.). In addition, it theories on dream bizarreness.

cannot be clearly distinguished from REM The non-invariant nature of bizarreness

dreaming bizarreness. In other words, the seems more consistent with models that

neurobiological events of REM sleep (PGO do not regard bizarreness as intrinsic to

activity, aminergic demodulation) are not dreaming processes.

an essential requirement for bizarreness. The presence of bizarreness in dreams

Results from other researches have cast in all sleep stages and in some waking

doubts on the role of PGO brainstem mentation (e.g., fantasies) seems more

activation as a cause of REM dream consistent with the concept of a common

bizarreness. Thus, the assumption that REM dream generation system in the stages of

dream bizarreness may be attributed to the sleep and of waking fantasies that is typical

random and non-cognitive nature of PGO of cognitive approaches. On the other

activity is not supported by the following hand, Foulkes’s claim of an essential

data: in first place, dream imagery seems to realism of REM dream reports does not

be actively constructed through complex seems to be confirmed.

cognitive processes rather than generated The evidence of more bizarreness in

by brainstem chaotic activation of the dream reports of the second half of night

forebrain; secondly, experimental studies on sleep than in those of the first part is

Sleep and Hypnosis, 5:3, 2003 121

Dream Bizarreness Reconsidered

consistent with the GCAT model on the Briefly, the literature has highlighted a

role of cortical cognitive activation in the need to reconsider dream bizarreness in a

increase of dream bizarreness. more general way, including several levels of

While there is no evidence that PGO analysis (neurobiological, cognitive and

spikes are fundamental for bizarreness, there psychological-motivational), rather than

still is the possibility that, phasic neural taking only the neurobiological point of

events (intrusion), in general and not only view. Dream bizarreness cannot be

PGO, during REM and NREM sleep may be explained as a simple expression of

a source (i.e., correlate) of bizarre mentation. neurobiological facts, and, on the other

From this viewpoint, Watson has shown hand, individual determinants seem to play

that PIPs activity varies individually and is an important role in its theoretical

more frequent in psychiatric patients and in explanation. From this perspective,

persons with greater imaginative abilities; considering dream bizarreness as deprived

exactly those people who apparently have of any psychological significance and

more bizarre dreams. dreams themselves as a meaningless by-

The data on the relationship between product appears to be premature. The

dream bizarreness and psychopathology studies on dream bizarreness could

are consistent with Hunt’s finding that probably be supported by research work on

dream reports in a psychoanalytic setting those forms of dreaming which, for reason

are more bizarre than home and laboratory still unclear, do not show the presence of

dreams. Together, these data seem to bizarreness (e.g., children dreams, childish

confirm Freud‘s observation, i.e. that the adult dreams, etc.). On the other hand, the

dreams of neurotic patients were more clinical/anatomical method, which has

bizarre than those of normal people. In already proved to be useful somehow in the

addition, the studies on the formal aspect study of dreams, might also contribute to

of children’s dreams are totally consistent the research on the underlying factors of

with the psychoanalytic approach. dream bizarreness production.

REFERENCES

1. Domhoff B, Kamiya J. Problem in dream content 9. Hobson JA. Activation, input source, and

study with objective indicators. Arch Gen modulation:neurocognitive model of the state of the

Psychiatry 1964;11:519-532. brain-mind. In: Bootzin RR, Kihlstrom JF, Schacter

DL, eds. Sleep and Cognition. University of

2. Foulkes D, Rechtschaffen A. Presleep determinants Arizona: American Psychological Association,

of dreams content: the effects of two films. Percept 1990;25-40.

Mot Skills 1964;19:983-1005.

10. Hobson JA. A new model of brain-mind state:

3. Rychlak JF, Brams JM. Personality dimension in Activation level, Input source, and Mode of

recalled dream content. Journal of Projective processing (AIM). In: Antrobus JS, Bertini M, eds.

Techniques 1963;27:226-234. The neuropsychology of sleep and dreaming.

Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum

4. Hobson JA, McCarley RW. The brain as a dream-state Associates Publisher, 1992;227-247.

generator: Activation-Synthesis hypothesis of dream

process. Am J Psychiatry 1977;134:1335-1368. 11. Hobson JA. Sleep and Cognition (1999). Retrieved

from the Web 2/ 22/00.

5. Foulkes D. Cognitive-psychological model of REM http://www.websciences.org/worldsleep/cancun99/hobson99.html

dream production. Sleep 1982;5:169-187.

12. Hobson JA, Pace-Schott EF, Stickgold R. Dreaming

6. Foulkes D. Dreaming: A cognitive-psychological and the brain: toward a cognitive neuroscience of

approach, Hillsdale: Erlbaum, 1985. conscious states. Behav Brain Sci 2000;23:793-

842.

7. Hobson JA. The dreaming brain, New York: Basic

Books Inc., 1988. 13. Hobson JA, Stickgold R. Dreaming: a

neurocognitive approach. Conscious Cognition

8. Hobson JA. Sleep, San Francisco: Freeman, 1989. 1994;3:1-15.

122 Sleep and Hypnosis, 5:3, 2003

C. Colace

14. Mamelak A, Hobson JA. Dream bizarreness as the 29. Bosinelli M, Cicogna P, Molinari S. The Tonic-

cognitive correlate of altered neuronal behavior in phasic model and the feeling of Self-participation in

REM sleep. Journal Cogn Neurosci 1989;1:843-849. different stages of sleep. Giornale Italiano di

Psicologia 1974;1:35-65.

15. Crick F, Mitchison G. The function of REM sleep.

Nature 1983;304:111-114. 30. Foulkes D, Pope R. Primary visual experience and

secondary cognitive elaboration in stage REM: a

16. Seligman M, Yellen A. What is a Dreaming? Behav modest confirmation and extension. Percept Mot

Res Ther 1987;25:1-24. Skills 1973;37:107-118.

17. Freud S. The Interpretation of Dreams. In: 31. Molinari S, Foulkes D. Tonic and phasic events

Strachey J, ed. The complete psychological works of during sleep: psychological correlates and

Sigmund Freud, London: Hogarth Press, 1900, vol implications. Percept Mot Skills 1969;29:343-368.

4-5.

32. Snyder F. The phenomenology of dreaming. In: Madow

18. Freud S. On dreams. In: Strachey J, ed. The L, Snow LH, eds. The Psychodynamic implications of

complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud, the physiological studies on dreams. Springfield:

London: Hogarth Press, 1901, vol 5. Charles C. Thomas Publisher, 1970;124-151.

19. Freud S. Introductory Lectures on Psycho-Analysis. 33. Dorus E, Dorus W, Rechtschaffen A. The incidence

In: Strachey J, ed. The complete psychological of novelty in dreams. Arch Gen Psychiatry

works of Sigmund Freud, London: Hogarth Press, 1971;25:364.

1915-17, vol 15-16.

34. Foulkes D. Children's Dreams, longitudinal studies,

20. Freud S. The dissolution of the Oedipus Complex. New York: Wiley-Interscience Publication, 1982.

In: Strachey J, ed. The complete psychological

works of Sigmund Freud, London: Hogarth Press, 35. Foulkes D. Children’s dreaming and the

1924, vol 19. development of consciousness, Cambridge,

Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1999.

21. Freud S. Autobiography. In: Strachey J, ed. The

complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud, 36. Antrobus JS. REM and NREM Sleep Reports:

London: Hogarth Press, 1924, vol 20. Comparison of Word Frequencies by Cognitive

Classes. Psychophysiology 1983;20:562-568.

22. Freud S. Jokes and their relation to the

Unconscious. In: Strachey J, ed. The complete 37. Antrobus JS. Dreaming: Cortical activation and

psychological works of Sigmund Freud, London: Perceptual Thresholds. J Mind Behav 1986;7:193-

Hogarth Press, 1905, vol 8. 212.

23. Hobson JA, Stickgold R, Pace-Schott EF. The 38. Antrobus JS. Dreaming: Cognitive processes during

neuropsychology of REM sleep dreaming. cortical activation and high afferent thresholds.

Neuroreport 1998;9:1-14. Psychol Rev 1991;98:96-121.

24. Kahn D, Pace-Schott EF, Hobson JA. Consciousness 39. Reinsel R, Antrobus JS, Wollman M. Bizarreness in

in waking and dreaming: the roles of neuronal dreams and waking fantasy. In: Antrobus JS,

oscilation and neuromodulation in determining Bertini M, eds. The neuropsychology of sleep and

similarities and differences. Neuroscience dreaming. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence

1997;78:13-38. Erlbaum Associates Publisher, 1992;157-183

25. Hobson JA. How the brain goes out of its mind. 40. Reinsel R, Wollman M, Antrobus JS. Effects of

Endeavour 1996;20:86-89. enviromental contex and cortical activation on

thought. J Mind Behav 1986;7:259-275.

26. Hobson JA. Dreaming as delirium : a mental status

analysis of our nightly madness. Semin Neurol 41. Wollman M, Antrobus JS. Sleeping and waking

1997;17:121-128. thought: effects of external stimulation. Sleep

1986;9:438-448.

27. Hobson JA, Hoffman SA, Helfand R, Kostner D.

Dream bizarreness and the activation-synthesis 42. Zimmerman WB. Sleep mentation and auditory

hypothesis. Hum Neurobiol 1987;6:157-164. awakening thresholds. Psychophysiology

1970;6:540-549.

28. Crick F, Mitchison G. REM sleep and neural nets. J

Mind Behav 1986;7:229-249. 43. Hunt HT. Forms of dreaming. Percept Mot Skills

1982;54:559-633.

Sleep and Hypnosis, 5:3, 2003 123

Dream Bizarreness Reconsidered

44. Hunt HT. The multiplicity of dreams, New Haven: 59. Colace C, Tuci B, Ferendeles R. Bizarreness in early

Yale University Press, 1989. children’s dreams collected in the home setting:

preliminary data. Sleep Res 1997;26:241.

45. Winget C, Kramer M. Dimension of dream,

Gainesville: Presses of Florida, 1979. 60. Zepelin H. Bizarreness in REM dreams. Sleep Res

1989;18:161.

46. Cipolli C, Bolzani R, Cornoldi C, De Beni R, Fagioli

I. Bizarreness effects in dream recall. Sleep 61. Bonato RA, Moffit AR, Hoffmann RF, Cuddy MA,

1993;16:163- 170. Wimmer L. Bizarreness in dream and nightmares.

Dreaming 1991;1:53-61.

47. Sutton JP, Rittenhouse CD, Pace-Schott E, Stickgold

R, Hobson JA. A new approach to dream 62. Cavallero C, Cicogna P, Natale V, Occhionero M,

bizarreness: graphing continuity and discontinuity Zito A. Slow Wave Sleep Dreaming. Sleep

of visual attention in narrative reports. Conscious 1992;15:562-566.

Cogn 1994;3:61-88.

63. Cicogna P, Cavallero C, Bosinelli M. Cognitive

48. Rittenhouse C, Stickgold R, Hobson JA. Constraints aspects of mental activity during sleep. Am J

on the transformation of characters, objects, and Psychol 1991;104:413- 425.

settings in dream reports. Conscious Cogn

1994;3:100-113. 64. Cicogna P, Natale V, Occhionero M, Bosinelli M. A

comparison of Mental Activity During Sleep Onset

49. Revonsuo A, Salmivalli C. A content analysis of bizarre and Morning Awakenings. Sleep 1998;21:462-470.

elements in dreams. Dreaming 1995;5:169-187.

65. Cicogna P, Natale V, Occhionero M, Bosinelli M.

50. Colace C, Natale V. Bizarreness in REM and SWS Slow Wave and REM Sleep Mentation. Sleep

dreams. Sleep Res 1997;26:240. Research Online 2000;3:67-72.

51. Bosinelli M. The study of Meta-Cognition during 66. Natale V, Esposito MJ. Bizarreness across the first

Sleep Mental Experiences. Metodological Problems, four cycles of sleep. Sleep and Hypnosis 2001;3:18-

1999. Retriewed February 22, 2000, from: 24.

http://www.websciences.org/worldsleep/cancun99/bosinelli2.html

67. Zito A, Cicogna P, Cavallero C. Sogni REM e sogni

52. Sutcliffe JP, Perry CW, Sheehan PW. Relation of some di addormentamento:in che termini è ancora

aspects of imagery and fantasy to hypnotic legittimo parlare di differenze?. Ricerche di

susceptibility. J Abnorm Psychol 1970;76:279-28. Psicologia 1992;2:7-18.

53. Hall CS, Van de Castle RL. The content analysis of 68. Cicogna P, Natale V, Occhionero M, Bosinelli M.

dreams, New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, Comparing dreams at onset and end of sleep. J

1966. Sleep Res 1996;5(Suppl. 1):33.

54. McCarley RW, Hoffman E. REM Sleep Dreams an 69. Natale V. Slow Wave Sleep Mentation: A

the Activation-Synthesis Hypothesis. Am J Comparison Between the First and the Second

Psychiatry 1981;138:904-912. Sleep Cycle. Sleep and Hypnosis 2000;2:84-89.

55. Foulkes D, Pivik T, Steadman HS, Spear PS, 70. Foulkes D. Dream Research: 1953-1993. Sleep

Symonds JD. Dreams of the male child: an EEG 1996;19:609-624.

study. J Abn Psychol 1967;72:457-467.

71. Nielsen TA. A review of mentation in REM and

56. Weisz RA, Foulkes D. Home and laboratory NREM sleep: “Covert” REM sleep as a possible

dreams collected under uniform sampling reconciliation of two opposing models. Behav Brain

conditions. Psychophysiology 1970;16:155-156. Sci 2000;23: 851-866.

57. Auld F, Goldenberg GM, Weiss JV. Measurement of 72. Cavallero C. REM sleep=dreaming: The never-

Primary-Process thinking in dream report. J Pers ending story. Behav Brain Sci 2000;23:904-907.

Soc Psychol 1968;8:418-426.

73. Foulkes D. Dreaming and REM sleep. J Sleep Res

58. Colace C, Violani C, Solano L. La 1993;2:199-202.

deformazione/bizzarria onirica nella teoria

freudiana del sogno:indicazioni teoriche e verifica 74. Bosinelli M. Impressione di realtà e proprietà

di due ipotesi di ricerca in un campione di 50 sogni percettive nella fenomenologia onirica. In: Gerbino

di bambini. Archivio di Psicologia Neurologia e W, ed. Conoscenza e struttura. Bologna: Il Mulino,

Psichiatria 1993;54:380-401. 1985;107-118.

124 Sleep and Hypnosis, 5:3, 2003

C. Colace

75. Bosinelli M, Molinari S. Contributo alle interpretazioni 90. Rowley JT, Stickgold R, Hobson JA. Eyelid

psicodinamiche dell'addormentamento. Rivista di movements and mental activity at sleep onset.

Psicologia 1968;62:369-393. Conscious Cogn 1998;7:67-84.

76. Bosinelli M, Cavallero C, Cicogna P. Self 91. Vogel GW. Sleep onset mentation. In: Arkin AM,

representation in two different psychophysiological Antrobus JS, Ellman SJ, eds. The mind in sleep:

contidions: the analysis of dream experiences psychology and psychophysiology. Hillsdale, New

during sleep onset and REM sleep. Sleep Jersey: Lawrence Erlabaum Associates Publishers,

1982;5:290-299. 1978;113-140.

77. Brown J, Cartwright R. Locating NREM dreaming 92. Porte H, Hobson JA. Bizarreness in REM and

through instrumental responses. Psychophysiology NREM reports. Sleep Res 1986;15:81.

1978;15:35-39.

93. Wood JM, Sebba D, Domino G. Do creative people

78. Cicogna P, Bosinelli M, Occhionero M. (1992). have more bizarre dreams? A reconsideration.

Processi ed esperienze mentali in sonno a onde Imagination, Cognition and Personality 1989;9:3-

lente. In: Smirne SL, Ferini Strambi L, Zucconi M, 16.

eds. Il sonno in Italia. Milano: Poletto Edizioni,

1992;55-59. 94. Casagrande M, Violani C, Lucidi F, Buttinelli E,

Bertini M. Variation in sleep mentation as a