Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Literature Review Submitted By: Muhammad Tayyab 44 Submitted To: Sir Azhar Majeed

Uploaded by

Shoaib Gondal0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

16 views3 pagesOriginal Title

Research proposal

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

16 views3 pagesLiterature Review Submitted By: Muhammad Tayyab 44 Submitted To: Sir Azhar Majeed

Uploaded by

Shoaib GondalCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 3

Literature review

Submitted By: Muhammad Tayyab 44

Submitted To: Sir Azhar Majeed

Role of Peers in reinforcing Gender Equality

Research problem

As children spend time with other children, they become more alike. Over time, children who are

friends tend to become much more similar to each other than chance alone would predict. This is

true in regard to gender development – children’s gendered behavior becomes more similar to

those they spend time with.4 Two processes have been used to explain this similarity.

First, children prefer to play with peers who are similar to them. Thus, girls may select other girls

because they share similar interests and activities. Second, children may become similar to their

friends due to influence, or the tendency of behaviors and interests to spread through social ties

over time.

Distinguishing between selection and influence effects requires identifying exactly whom

children play with and how their peer interactions affect their behavior and development. This is

not easy because one needs detailed longitudinal data on social relationships and individual

characteristics – something that is quite demanding, expensive and difficult to obtain.

Different Dimensions

Peer groups can serve as a venue for teaching members gender roles. Gender roles refer to the set

of social and behavioral norms that are considered socially appropriate for individuals of a

specific sex in the context of a specific culture, and which differ widely across cultures and

historical periods.

Through gender-role socialization, group members learn about sex differences, and social and

cultural expectations. Biological males are not always masculine and biological females are not

always feminine. Both genders can contain different levels of masculinity and femininity. Peer

groups can consist of all males, all females, or both males and females.

Peer groups can have great influence on each other’s gender role behavior depending on the

amount of pressure applied. If a peer group strongly holds to a conventional gender social norm,

members will behave in ways predicted by their gender roles, but if there is not a unanimous peer

agreement, gender roles do not correlate with behavior. There is much research that has been

done on how gender affects learning within student peer groups. The purpose of a large portion

of this research has been to see how gender affects peer cooperative groups, how that affects the

relationships that students have within the school setting, and how gender can then affect

attainment and learning. One thing that is an influence on peer groups is student behavior.

Knowing early on that children begin to almost restrict themselves to same-gendered groups, it is

interesting to see how those interactions within groups take place. Boys tend to participate in

more active and forceful activities in larger groups, away from adults, while girls were more

likely to play in small groups, near adults. These gender differences are also representative of

many stereotypical gender roles within these same-gendered groups. The stereotypes are less

prominent when the groups are mixed-gendered.

When children do not conform to the appropriate gender role, they may face negative sanctions

such as being criticized or marginalized by their peers. Though many of these sanctions are

informal, they can be quite severe. For example, a girl who wishes to take karate class instead of

dance lessons may be called a “tomboy,” facing difficulty gaining acceptance from both male

and female peer groups. Boys, especially, are subject to intense ridicule for gender

nonconformity.

International Researchers

Children’s gender-typed play activities and the reinforcement of same-gender play partners. A

young man describes strong preferences among peer groups for regarding for gender-conforming

play activities amongst peers.

Each gender had a set of rules. Girls wore pink and red, bright colors, while boys wore black and

blue, dark colors. Girls played house, colored, and did their hair, while boys played sports, had

action figures, and loved cars and trucks... We would think that girls are weak and bad at sports,

so when we played in recess we would not let them play with us. We never allowed the girls to

play tether ball or kickball.

Another young man confirms the strict “rule” status of preferences in schoolyard play. In

elementary school, when playing soccer during recess, I remember always selecting the boys to

be on my team, and stating „girls cannot run as fast‟, thus supporting the mentality and ideology

that women are weaker when it comes to playing sports.

Both young men appear to have internalized gender-differences in play to the extent that they

enact what they believe to be appropriate behavior for their identified gender, and also enforce

others’ adherence. In this way, gender-segregated play supports a binary conception of gender

roles and belief chemas.

A young woman recalls her play activities at school and in her neighborhood. In elementary

school, girls were friends and played with girls and boys were friends and played with boys. We

played games like jacks or hopscotch and did dances and cheerleading routines. Boys played

basketball or kickball and sports like that.

Outside of school in the neighborhood I lived in, the boys all had BMX bikes and would race

them. I remember that seeming like a very „boy‟ thing to do. The girls would say „ready, set,

go‟ for the boys to race, just like the girls would do in the movie „Grease‟. It seemed like

something a pretty girl would do for boys.

This vignette highlights a pattern that continues into adolescence and beyond. Girls take on

supportive roles and remain on the sidelines, while boys are involve in the main action of play

activity. In the following a young woman describes her self-socialization. She is keenly aware of

the impact her peers changing expectations have had on her choice in music, television shows,

and play activities, despite her actual preferences which remained non-normative.

If I wanted to be a good girl and be seen as a good girl by others then I had to dress a certain

way. I had to be, act, and even listen to certain music and even play with others a certain way.

Towards the end of the third grade, I no longer watched wrestling shows, I no longer chased my

friends and played in the dirt. If I played outside, I played picnic or Barbies with my neighbor on

my front lawn, or we would ride our bikes to the park and back. I was somewhat upset that I

could no longer play the way I wanted to.

Other girls at my school still played and chased each other in the dirt. I told them I couldn’t play

anymore. So we changed our way of playing, we still wrestled just not in the dirt. It was either in

the grass or bark. I still had to be careful not to stain my clothes and it just wasn‟t as fun as

before. Eventually the school changed its school ground policies and the kids could not play so

“rough” because they would get hurt. I guess the institution stepping in helped ease my playing

transition from “rough” and “boy-like” to playing like an actual “lady” with Barbies and picnics.

Her desire to be a “good girl” motivates self-socialization, which describes as a common source

of conformity among young women.

You might also like

- Gender SocializationDocument13 pagesGender Socializationreenachrn78% (9)

- Solution. Investment 1: Simple Interest, With Annual Rate RDocument11 pagesSolution. Investment 1: Simple Interest, With Annual Rate RLucky Gemina67% (3)

- Grievance Handling-Industrial RelationsDocument4 pagesGrievance Handling-Industrial RelationsArif Mahmud Mukta100% (5)

- Clup 2016-2030 Volume 2 - Zoning Ordinance Version 5.12 2018-10-31 For PrintingDocument249 pagesClup 2016-2030 Volume 2 - Zoning Ordinance Version 5.12 2018-10-31 For PrintingClarissa AlegriaNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Peer Groups On Gender Identity and ExpressionDocument9 pagesThe Effect of Peer Groups On Gender Identity and ExpressionQazi QaziNo ratings yet

- Gender Roles Harm Self-PerceptionTITLEDocument4 pagesGender Roles Harm Self-PerceptionTITLEAnasol Del RiveroNo ratings yet

- CamScanner 08-02-2022 08.24.33Document19 pagesCamScanner 08-02-2022 08.24.33Ruby CasasNo ratings yet

- The Development of Gender IdentityDocument7 pagesThe Development of Gender IdentityAlyza May FenisNo ratings yet

- Sex-Stereotypical Behaviors in Ms Bentons Kindergarten Classroom A Case StudyDocument8 pagesSex-Stereotypical Behaviors in Ms Bentons Kindergarten Classroom A Case Studyapi-99042879No ratings yet

- English 113a Final Essay 1Document6 pagesEnglish 113a Final Essay 1api-302420785No ratings yet

- Developmental Psychology WordDocument6 pagesDevelopmental Psychology WordSundas SaikhuNo ratings yet

- Gender Roles and Household WorkDocument12 pagesGender Roles and Household WorkGamidi Suneetha NaiduNo ratings yet

- Gender in EducationDocument7 pagesGender in EducationAnonymous v8AfMnT5No ratings yet

- Gess 304Document12 pagesGess 304Dhruv ChaturvediNo ratings yet

- Unit Three: Rationalised 2023-24Document12 pagesUnit Three: Rationalised 2023-24Deepa ShuklaNo ratings yet

- Betwixt and Be TweenDocument16 pagesBetwixt and Be Tweenapi-241255416No ratings yet

- Gender SocializationDocument2 pagesGender SocializationTasaddaq Iqbal BagriNo ratings yet

- Gender Roles and SocializationDocument6 pagesGender Roles and SocializationJenny May GodallaNo ratings yet

- Final Essay On Gender ConstructionDocument5 pagesFinal Essay On Gender Constructionapi-273285076No ratings yet

- Gender Is It A Social Construct or A Biological InevitabilityDocument5 pagesGender Is It A Social Construct or A Biological InevitabilitySaurabhChoudharyNo ratings yet

- Christeen Mazed Composing Gender Essay 2126972 2112889466 1Document5 pagesChristeen Mazed Composing Gender Essay 2126972 2112889466 1api-302460411No ratings yet

- Iii. Socialization Into Gender: Reporter: Aira Jane Villa Course Facilitator: Prof. DemaisipDocument2 pagesIii. Socialization Into Gender: Reporter: Aira Jane Villa Course Facilitator: Prof. Demaisiparia jen05No ratings yet

- Socializing GenderDocument9 pagesSocializing GenderMohammed Hasnain MansooriNo ratings yet

- FINAL EXAM - Nguyễn Hồng-SOC105002Document9 pagesFINAL EXAM - Nguyễn Hồng-SOC105002walyonhNo ratings yet

- Ncgessch14 PDFDocument12 pagesNcgessch14 PDFAnonymous KSF09JKBNo ratings yet

- Geel 2 Reflective EssayDocument2 pagesGeel 2 Reflective EssayEssa MalaubangNo ratings yet

- What Is MaleDocument6 pagesWhat Is MaleBudi PrasetyoNo ratings yet

- Exams Answer PaperDocument11 pagesExams Answer PaperIsmael Mooniaruth RoubinahNo ratings yet

- Carl J PDFDocument7 pagesCarl J PDFElizabeth MartínezNo ratings yet

- Astrid Dia Graded Essay 1Document5 pagesAstrid Dia Graded Essay 1api-273264890No ratings yet

- CHAPTER 4 - Socialization and GenderDocument5 pagesCHAPTER 4 - Socialization and GenderHIEZEL BAYUGNo ratings yet

- Gender School and SocietyDocument15 pagesGender School and SocietyMisha ShuklaNo ratings yet

- Benefits of Co-Ed SchoolsDocument2 pagesBenefits of Co-Ed SchoolsDessa BartolomeNo ratings yet

- Sample Reaction PaperDocument1 pageSample Reaction Paperjasonmscofield63% (8)

- Progression 1Document5 pagesProgression 1api-341026919No ratings yet

- Gender Socialization in Childhood DevelopmentDocument16 pagesGender Socialization in Childhood DevelopmentSuman AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Gender Lesson 2.1Document3 pagesGender Lesson 2.1Jao Duran100% (1)

- Essay 1 FinalDocument5 pagesEssay 1 Finalapi-357218012No ratings yet

- 3.3 Gender Socialization in ChildhoodDocument2 pages3.3 Gender Socialization in ChildhoodaliazmaNo ratings yet

- Final Essay RedoDocument5 pagesFinal Essay Redoapi-302427497No ratings yet

- Reflection Essay 2Document2 pagesReflection Essay 2SamicamiNo ratings yet

- Gender Discrimination in Hidden CurriculumDocument15 pagesGender Discrimination in Hidden CurriculumManerisSanchez PenamoraNo ratings yet

- Krishna Kumar, Growing Up Male PDFDocument8 pagesKrishna Kumar, Growing Up Male PDFSayani NandyNo ratings yet

- Gender Schema Theory Explains Cultural Influence on Gender RolesDocument3 pagesGender Schema Theory Explains Cultural Influence on Gender RolesM SadiqNo ratings yet

- Ans 2 JjjjnskjlefhDocument4 pagesAns 2 JjjjnskjlefhJayesh TanejaNo ratings yet

- How Do Single Sex Schools Effect Students Young People EssayDocument3 pagesHow Do Single Sex Schools Effect Students Young People EssaydulichsinhthaiNo ratings yet

- Pangasinan State University Social Sciences DepartmentDocument3 pagesPangasinan State University Social Sciences DepartmentPia Mae Zenith CalicdanNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument5 pagesUntitledParofil NestleNo ratings yet

- Gender Early SocializationDocument27 pagesGender Early SocializationNat LindsayNo ratings yet

- Coa 3 - GSDocument1 pageCoa 3 - GSGrace Anne IldefonsoNo ratings yet

- Media's reinforcement of gender stereotypesDocument3 pagesMedia's reinforcement of gender stereotypesJayJayNo ratings yet

- Progression I EssayDocument6 pagesProgression I Essayapi-302479991No ratings yet

- Gender: Biology or Society?: Tal Elgaoi Writing 303 Due: 02/08/11Document4 pagesGender: Biology or Society?: Tal Elgaoi Writing 303 Due: 02/08/11Tal ElgaoiNo ratings yet

- Gender Socialization and Stereotypes in the PhilippinesDocument3 pagesGender Socialization and Stereotypes in the PhilippinesAshley June GomezNo ratings yet

- Sociology Group AssignmentDocument23 pagesSociology Group AssignmentLayton YanniNo ratings yet

- Transgender-Booklet Web-BookletDocument36 pagesTransgender-Booklet Web-Bookletapi-254863225No ratings yet

- Argument EssayDocument8 pagesArgument Essayapi-702737514No ratings yet

- Running Head: Parenting Styles 1Document6 pagesRunning Head: Parenting Styles 1LaDonna WhiteNo ratings yet

- How Society Affects Gender Roles RevisedDocument5 pagesHow Society Affects Gender Roles Revisedapi-302486431No ratings yet

- Module 1 (Week 1)Document5 pagesModule 1 (Week 1)Niña Rica DagangonNo ratings yet

- Unit 2 GENDER SENSITISATIONDocument21 pagesUnit 2 GENDER SENSITISATIONPiyushNo ratings yet

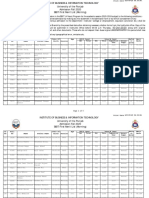

- Subject:Theories of Test Development: Final Term ExaminationDocument11 pagesSubject:Theories of Test Development: Final Term ExaminationShoaib GondalNo ratings yet

- Effects of Tiktok on YouthDocument73 pagesEffects of Tiktok on YouthShoaib GondalNo ratings yet

- Name: Darakhshan Nigar Roll No: 2020-1104 Instructor Name: Dr. Abaidullah Semester: 2nd Subject: Theories of Test DevelopmentDocument9 pagesName: Darakhshan Nigar Roll No: 2020-1104 Instructor Name: Dr. Abaidullah Semester: 2nd Subject: Theories of Test DevelopmentShoaib GondalNo ratings yet

- Usman Soomro 51 MDocument3 pagesUsman Soomro 51 MShoaib GondalNo ratings yet

- Sociology Central Teaching NotesDocument15 pagesSociology Central Teaching NotesRaveena.WarrierNo ratings yet

- 61ST Bbitmeritlist M PDFDocument5 pages61ST Bbitmeritlist M PDFShoaib GondalNo ratings yet

- Usman Soomro 51 MDocument3 pagesUsman Soomro 51 MShoaib GondalNo ratings yet

- LN Sociology FinalDocument292 pagesLN Sociology FinalShahriar MullickNo ratings yet

- 7FML MTE Morning 2020 PDFDocument2 pages7FML MTE Morning 2020 PDFShoaib GondalNo ratings yet

- Gender Art and LiteratureDocument3 pagesGender Art and LiteratureShoaib GondalNo ratings yet

- 85first Merit List Bs Sociology Regular 2020 PDFDocument2 pages85first Merit List Bs Sociology Regular 2020 PDFShoaib GondalNo ratings yet

- Women Building Cohesive Societies Summary PDFDocument2 pagesWomen Building Cohesive Societies Summary PDFShoaib GondalNo ratings yet

- 7FML MA Islamic Education 2020 PDFDocument2 pages7FML MA Islamic Education 2020 PDFShoaib GondalNo ratings yet

- 5first Merit List BBA M-Iba 2020 PDFDocument3 pages5first Merit List BBA M-Iba 2020 PDFShoaib GondalNo ratings yet

- 6GML MTE Morning 2020 PDFDocument3 pages6GML MTE Morning 2020 PDFShoaib GondalNo ratings yet

- Department of Islamic Education announces selectees for M.A. Islamic EducationDocument3 pagesDepartment of Islamic Education announces selectees for M.A. Islamic EducationShoaib GondalNo ratings yet

- 8GML BS Chemistry 2020 PDFDocument138 pages8GML BS Chemistry 2020 PDFShoaib GondalNo ratings yet

- Women PakistanDocument67 pagesWomen PakistansabinaNo ratings yet

- Gender roles and working patterns in LahoreDocument9 pagesGender roles and working patterns in LahoreShoaib GondalNo ratings yet

- Literature Review: Background of ResearchDocument5 pagesLiterature Review: Background of ResearchShoaib GondalNo ratings yet

- Family of Single ParentsDocument8 pagesFamily of Single ParentsShoaib GondalNo ratings yet

- The Economics of Late MarriageDocument9 pagesThe Economics of Late MarriageShoaib GondalNo ratings yet

- Unw Pakistan Country Profile 2018 Compressed PDFDocument32 pagesUnw Pakistan Country Profile 2018 Compressed PDFShoaib GondalNo ratings yet

- Application Form For Streams One & Two: Regional Technology Clustering FundDocument11 pagesApplication Form For Streams One & Two: Regional Technology Clustering FundShoaib GondalNo ratings yet

- Family D PDFDocument26 pagesFamily D PDFShoaib GondalNo ratings yet

- Female Labor Force Participation Pakistan PDFDocument8 pagesFemale Labor Force Participation Pakistan PDFShoaib GondalNo ratings yet

- Junior Accountant-Clerk CTS FormDocument3 pagesJunior Accountant-Clerk CTS FormenergyrockfulNo ratings yet

- Society For The Scientific Study of Religion, Wiley Journal For The Scientific Study of ReligionDocument12 pagesSociety For The Scientific Study of Religion, Wiley Journal For The Scientific Study of ReligionShoaib GondalNo ratings yet

- Family D PDFDocument26 pagesFamily D PDFShoaib GondalNo ratings yet

- Macbeth and Decanonizing ShakespeareDocument4 pagesMacbeth and Decanonizing ShakespeareChezka AngaraNo ratings yet

- The New Foreign PolicyDocument25 pagesThe New Foreign PolicydidierNo ratings yet

- Illustrator Cooperation AgreementDocument9 pagesIllustrator Cooperation AgreementCaroline FeijóNo ratings yet

- POB TestDocument2 pagesPOB TestMuricia AshbyNo ratings yet

- Jatiya Kabi Kazi Nazrul Islam University: Trishal, MymensinghDocument10 pagesJatiya Kabi Kazi Nazrul Islam University: Trishal, MymensinghrafatsantoNo ratings yet

- A Written Report On Self Governance, Independent Nursing Practice, Evidence Based PracticeDocument16 pagesA Written Report On Self Governance, Independent Nursing Practice, Evidence Based PracticeCarlo Emmanuel Santos100% (2)

- The Place of Race in Conservative and Far-Right MovementsDocument10 pagesThe Place of Race in Conservative and Far-Right Movementsapi-402856696No ratings yet

- IPC Final ProjectDocument22 pagesIPC Final ProjectHrishika NetamNo ratings yet

- Ansi Saia A92 5 2006 R2014 Boom Supported Elevating Work PlatformsDocument62 pagesAnsi Saia A92 5 2006 R2014 Boom Supported Elevating Work PlatformsLuis Carcamo Martinez100% (1)

- THE INSURANCE CODE OF ReviewerDocument20 pagesTHE INSURANCE CODE OF ReviewerMary Kristin Joy GuirhemNo ratings yet

- Form GaransiDocument3 pagesForm GaransiRovita TriyambudiNo ratings yet

- Calimlim-Canullas V Fortun Sales CaseDocument1 pageCalimlim-Canullas V Fortun Sales Caseruth_pedro_2100% (1)

- Format of Final Research PaperDocument10 pagesFormat of Final Research PaperHaroon AhmedNo ratings yet

- Gul v. Bush Reply in Support of Motion To Review Certain Detainee MaterialsDocument30 pagesGul v. Bush Reply in Support of Motion To Review Certain Detainee MaterialsWashington Free BeaconNo ratings yet

- Internal Audit S Role in EsgDocument4 pagesInternal Audit S Role in EsgDumNo ratings yet

- Políticas de ReservaDocument12 pagesPolíticas de Reservafauno_ScribdNo ratings yet

- Labour Law - IIDocument10 pagesLabour Law - IIAbhijit BansalNo ratings yet

- Social Justice GoalsDocument2 pagesSocial Justice GoalsCheesy MacNo ratings yet

- Ac16 601P Gabuat The Budget ProcessDocument5 pagesAc16 601P Gabuat The Budget ProcessRenelle HabacNo ratings yet

- Expropriation or Eminent DomainDocument3 pagesExpropriation or Eminent Domaindivine venturaNo ratings yet

- Adcb Aura BankDocument1 pageAdcb Aura Bankabdhaadi.saqibNo ratings yet

- WWW - Eaadharam.in - 25.08.2020 - Chitty Compounding FEEDocument4 pagesWWW - Eaadharam.in - 25.08.2020 - Chitty Compounding FEEAnand MvlNo ratings yet

- The Tortilla Curtain EssayDocument5 pagesThe Tortilla Curtain Essayapi-272863828No ratings yet

- Central Information Commission and Panchayati Raj in IndiaDocument29 pagesCentral Information Commission and Panchayati Raj in IndiahariNo ratings yet

- Judicial Appointments in PakistanDocument9 pagesJudicial Appointments in PakistanFURQAN AHMEDNo ratings yet

- Auto Bus Transport Systems Inc V BautistaDocument2 pagesAuto Bus Transport Systems Inc V BautistaJordan Chavez100% (1)

- The American Freshman 2019Document86 pagesThe American Freshman 2019mmcintyrNo ratings yet