Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Chernoff Et Al 1999 Fishes of The Rios T

Uploaded by

Juliana MonteiroOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Chernoff Et Al 1999 Fishes of The Rios T

Uploaded by

Juliana MonteiroCopyright:

Available Formats

CHAPTER 3

FISHES OF THE RIOS

T A H U A M A N U, M A N U R I P I A N D

N A R E U D A , D E P TO. P A N D O,

BOLIVIA: D I V E R S I T Y,

DISTRIBUTION, CRITICAL

HABITATS AND ECONOMIC

VALUE

Barry Chernoff, Philip W. Willink, Jaime Sarmiento,

Soraya Barrera, Antonio Machado-Allison, Naércio

Menezes, and Hernán Ortega

ABSTRACT This work reports upon the ichthyological results of

the first AquaRAP survey carried out in a relatively small

Two teams of ichthyologists surveyed the freshwater fishes area of the upper Río Orthon. Two teams of ichthyologists

of the Río Tahuamanu, Río Manuripi and Río Nareuda, surveyed aquatic habitats in the Ríos Tahuamanu and

Pando, Bolivia at 85 collecting stations for 17 days. They Manuripi and their tributaries over 17 days in 1996.

captured 313 species of which 87 are new records for Amazingly, 313 species of fishes were recorded. This value

Bolivia. These records bring the total fish fauna of Bolivia includes a spectacular number of new records for Bolivia and

to 641 species and for the Bolivian Amazon to 501 species. several species new to science, including a remarkable new

This small region in northeastern Bolivia contains 63% and piranha in the genus Serrasalmus.

49% of all the species known to inhabit the Bolivian The purpose of this report is to: (i) make known the

Amazon and Bolivia, respectively. This region is potentially general ichthyological results, including a breakdown by sub-

a hotspot of fish biodiversity. The habitats on which these basin; (ii) compare the diversity with those of other regions

fishes depend is discussed, from which we recommend the and discuss any distributional aspects of the data; (iii)

preservation of key flooded areas, main river channels, and discuss the economic and conservation importance of the

small streams or tributaries passing through terra firme results; (iv) discuss specific threats to the biodiversity; and

habitats. A large percentage of the fauna have high (v) discuss recommendations for conservation and future

economic value as food or ornamental fishes. Stocks are in research. In a companion paper (Chapter 5) , specific

need of immediate evaluation, and the exportation of food analyses of distributions within the study region and among

fishes needs to be regulated as soon as possible. macrohabitats and water type will be presented along with

specific management recommendations.

INTRODUCTION

METHODS

The forested lowlands of most amazonian tributaries remain

poorly explored. Lists of freshwater fishes do not exist for

Two fish teams, each containing three to four members,

more than one or two of the major arms of the Amazon,

made collections from 4 - 21 September 1996. The two

though Welcomme (1990) lists 389 species for the Río

teams usually worked apart and were camped in different

Madeira. Goulding (1981) produced a remarkable work on

sections of the Upper Río Tahuamanu for the first five days.

the fishes and fisheries of the Río Madeira, but provided no

Eighty-five collection stations were made, each receiving a

list of species. In Bolivia there have been attempts to bring

unique, sequential field number (Appendix 8). The field

together information for amazonian streams (e.g., Lauzanne

stations were enumerated separately for each group,

et al., 1991). More recently, a well documented fauna from

identified as P1 and P2. At each station, longitude and

the Río Gaupore/Itenez was provided by Sarmiento (1998).

latitudes were obtained from hand-held GPS units that had

Lauzanne et al. (1991) recorded 389 species of freshwater

been calibrated and checked at the airstrip in Cobija, Pando,

fishes from the Bolivian Amazon to which Sarmiento (1998)

Bolivia for which we have accurate coordinates. Obtaining

added an additional 21 species, bringing the total to 410

geographic coordinates in the field was not always possible

species.

because of forest cover and position of satellites.

BULLETIN OF BIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT FIFTEEN December 1999 39

At each field station a number of ecological variables were ambiguous or unknown in our list AND in published

describing the habitat were recorded. These included lists. So for example, if Hemigrammus sp. or

descriptions of the shore, substrate, type of habitat (e.g., Hemigrammus sp. 1 occurred in both lists, it was not

river, lake, flooded area, etc.) as well as the water type. The counted as a similarity or a difference because there is no

classification of water type (black, white, turbid) was way to ascertain that the taxonomic designations represent

checked with the results obtained by the limnology group. the same biological entity. However, Gephyrocharax sp.

Fishes were collected using a variety of nets and netting occurs in our list but only G. chapare is reported by either

techniques. Each group was equipped with seines (5m x 2m Lauzanne et al. (1991) or Sarmiento (1998). In this case we

x 1.25 cm, 5m x 2m x 0.63 cm, 1.3m x 0.7m x 0.37 cm), dip count the Gephyrocharax sp. as a new record because we

nets and experimental gill nets (40m x 2m, monofilament, compared our material to G. chapare, and it is different.

with five 8m panels, mesh size from 1.25 cm to 6.25 cm). The possible error in this latter case is identical to the

Team 2 pulled an otter trawl (mouth 3m wide) with two 15 possible errors in a list containing misidentified species

kg doors where the depth of the water was >2m over sandy bearing specific epithets or not.

or muddy stretches in a manner modified from that described

by López-Rojas et al. (1984). Additionally, one of the river Collecting Stations

pilots threw a 2m cast net in some deeper lakes or cochas.

Fishes were preserved in buffered 10% formalin Eighty-five collections were taken in the Tahuamanu and

solution. All specimens captured at the same place and time Manuripi river basins from the border with Peru down-

were maintained separately from all other collected speci- stream to Puerto Rico (Maps 1 - 3). The entire region was

mens. Larger specimens were tagged individually using fine divided into the following six subregions: Upper, Middle and

wire and punched cardboard tags and either placed in large Lower Tahuamanu; Upper and Lower Nareuda; and the

liquidpacks containing formalin with other specimens or Manuripi. The Río Nareuda is a major tributary of the Río

were skeletonized, soaked in 40% isopropanol and dried. Tahuamanu.

All material was wrapped and shipped to Chicago for The gear effort used to sample the 85 field stations

sorting, identification and enumeration in the Division of were as follows: seine –73; trawl – 6; gill net – 5; cast net –2.

Fishes, Department of Zoology, Field Museum (FMNH). This adds up to 86 because one station, P2-04, included

Fifty percent of the specimens are housed in the Museum of both gill net and seine collections. The gill nets were usually

Natural History, La Paz, Bolivia; the remaining specimens set for several days. Because no striking differences were

were shared among the participating institutions: FMNH; noted for day and night samples within the gill nets, they

Museu Zoologia do Universidade do São Paulo, Brazil; were recorded as single stations. Due to low water condi-

Museo de Historia Natural San Marcos, Perú, and Museo tions during the time of the field sampling, trawling was

Biologica de la Universidad Central de Venezuela. difficult because motors had only limited use in the Upper

The identifications were made in a careful but relatively Tahuamanu and could not be used in the Río Nareuda except

rapid fashion. General works such as Eigenmann and Myers for in the vicinity of its confluence with the Río Tahuamanu.

(1929) or Gery (1977) were used, but preference was During the first portion of the expedition, Team 1

always given to systematic revisions (e.g., Vari, 1992; Mago- worked in the Upper Tahuamanu and also in the lower end

Leccia, 1994) and recent species descriptions (Stewart, of the Río Muymanu, whereas Team 2 collected in the

1985) if available. In many cases specimens were compared Upper Nareuda as well as in a number of small streams

to types or historic material referenced in the literature and (garapes) that drained independently into the Tahuamanu.

housed at FMNH. However, identification to the level of The Upper Tahuamanu and the Upper Nareuda systems as

species or even genus was not always possible. To do so well as their tributaries were surrounded by terra firme.

would represent a less than scholarly approach to the For the middle portion of the expedition, Team 1

taxonomy. Instead we rely upon morphospecies – the focused upon the Lower Nareuda down to its mouth in the

number of distinguishable entities present in our samples. Río Tahuamanu. Team 2 collected upstream and down-

This bears the assumption that such discernable entities or stream from this confluence to just below the village of

morphospecies are putative taxonomic entities (i.e., species). Filadelfia; this region is referred to as Middle Tahuamanu.

We were careful to check for sexual and ontogenetic Conditions in the Middle Tahuamanu were such that

differences. All specimens were examined critically and trawling was accomplished successfully.

identified to their lowest taxonomic level (Appendix 6). For the last period both teams camped on the Río

Another issue inheres in the appropriate selection of Manuripi upstream from Puerto Rico. Though both groups

taxa across lists in order to judge new geographic records worked independently, they covered the same territory in

(Appendix 7). We chose a conservative approach and did the Río Manuripi as well as in the Lower Tahuamanu, just

not include all of the taxa that we had collected. We above its mouth in the Río Manuripi. River conditions

eliminated from comparison those taxa whose identifications permitted trawling.

40 CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL Rapid Assessment Program

about 21% to 501 and increases the total for all of Bolivia

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

(using the previous total in Sarmiento, 1998) 16% to 641

species.

Diversity and Distribution: General

The significance of the Tahuamanu and Manuripi rivers

for the Bolivian ichthyofauna is now clear. This limited

The biodiversity of fishes was unexpectedly spectacular. A

region contains 63% of all fish species known from the

total of 313 species were captured and identified. The fishes

Bolivian Amazon and 49% of all fishes known from Bolivia.

(Appendix 6) included members of all trophic or activity

Furthermore, the 87 species found in the Tahuamanu and

groups, ornamentals (e.g., Abramites hypselonotus), food

Manuripi rivers that are not yet known elsewhere in Bolivia

fishes (e.g., Pseudoplatystoma fasciatum), as well as

represent within-country “endemism” values of 18% and

miniatures (Scoloplax cf. dicra, <20 mm SL) and large fishes

14% relative to the ichthyofaunas for the Bolivian Amazon

(e.g., Prochilodus cf. nigricans, Doras cf. carinatus, >200

and Bolivia, respectively.

mm SL).

Based upon the relatively sparse information published

Together Lauzanne et al. (1991) and Sarmiento (1998)

for the ichthyofauna of Bolivia, of regions with more than 50

record 410 species from all rivers within the Bolivian

species, only Lake Titicaca has a higher within-country

Amazon. The 313 species of fishes, therefore, represents a

“endemism” percentage. No other region within Bolivia is

fauna greater than 76% of the number of species previously

currently known to contain as high a percent of the

reported from all other Amazonian tributaries within Bolivia

amazonian or total country fauna. The impressive values

(Appendix 7). The number of fishes discovered in a

reported for the Río Guapore/Itenez basin within the Parque

relatively small section of the Tahuamanu and Manuripi

Nacional Noel Kempff reported upon by Sarmiento (1998)

rivers is more than three times that reported for the entire

must now be adjusted downwards due to the new species

Beni-Madre de Dios basin (n=101, Lauzanne et al., 1991),

totals. The adjusted values are well below those of the

more than 1.3 times that reported for the Río Guapore/

Tahuamanu and Manuripi rivers.

Itenez (n=246, Sarmiento, 1998) and almost equal to (96%)

Potentially, the impressive nature of the Tahuamanu-

that found over the entire Río Mamore basin (n=327,

Manuripi ichthyofauna could be tempered if, in fact, it was

Lauzanne et al., 1991). Furthermore, Santos et al. (1984)

representative of a more widespread fauna within Bolivia.

reported 300 species from the lower Río Tocantins of Brazil;

The most obvious possibility is that we used trawls to

Stewart et al. (1987) reported 473 species in the Napo River

sample the bottom communities for the first time within

Basin of Ecuador; and Goulding et al. (1988) reported 450+

Bolivian freshwaters. If the 87 novel records were largely

species from the Río Negro basin of Brazil. In each of these

due to trawl samples, then the lists would not really be

latter cases, the areas surveyed exceed vastly that of the

comparable. That is, we might expect to find similar bottom

Tahuamanu-Manuripi region sampled in the rapid assess-

communities in other regions; the uniqueness of the

ment.

Tahuamanu-Manuripi region would diminish even though its

It is important to consider that the number of species

overall diversity would remain exceptional. However, this

reported for both the Guapore/Itenez and Mamore drainages

was not observed. The trawls captured 53 species (17% of

included headwater habitats that usually contain fishes with

the total), but only 15 species were captured in trawls

restricted distributions. Even in the Upper Tahuamanu and

exclusively. Of these, 10 were new records for Bolivia.

Upper Nareuda, there were few habitats, perhaps the two

Thus, 77 of the 87 species newly reported for Bolivia were

garapes, that could correspond to headwater-like conditions.

captured by traditional means used commonly in ichthyo-

Because of the paucity of knowledge concerning the

logical sampling.

distributions of the freshwater fishes of South America, it is

We have no doubt that more careful sampling as

difficult to state with any certainty the degree of endemism

exemplified in the Guapore/Itenez by Sarmiento (1998) and

represented in AquaRAP samples from the upper Río

in the Tahuamanu-Manuripi by the AquaRAP team will lead

Orthon. However, we have apparently uncovered not only

to increasing the number of taxa found within Bolivia and

a region with high biodiversity, but a region with an

will increase knowledge of the distribution patterns of the

exceptional number of new records for Bolivia (Appendix

fishes. Nonetheless, it seems unlikely that the distinctive

7). Using the conservative approach discussed above, we

character of the Tahuamanu-Manuripi fauna will lose its

document 87 species not previously recorded from Bolivia.

uniqueness.

Of the 87 species, 45 are new to science (e.g., the new

In fact with continued sampling, the ichthyofauna of

characid, Chrysobrycon sp. 1) or species with some

the Tahuamanu-Manuripi region will continue to rise and the

questions associated with their exact name (e.g. Anchoviella

number of species new to Bolivia should also increase. We

cf. carrikeri). The newly documented fauna increases the

base this estimate upon the species accumulation curves

total number of species inhabiting the Bolivian Amazon by

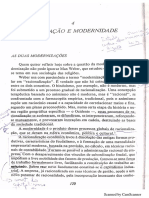

(Fig. 3.1). After 15 days of sampling, the rate of accumula-

tion of species new to the expedition had not diminished; the

BULLETIN OF BIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT FIFTEEN December 1999 41

graph displays no asymptote (Fig. 3.1). During the last six curve, the number of species represented in this region is

days, even with both groups working the same region of the predictably larger than we can document at present.

Manuripi, we increased the known fauna by 63 species. Furthermore, because the number of new records comprises

Species were being added at an average rate of 10.5 species 29% of the fauna of this region, it is reasonable to expect

per day. new records as well.

The total capture and accumulation rates were All of this leads to the conclusion that within Bolivia,

remarkably similar for each of the two collecting teams (Fig. the upper Río Orthon basin must be considered as a

3.1). Each group captured more than 200 species. By the potential hot spot for the biodiversity of freshwater fishes.

end of the sampling period, the species collected by the Conservation efforts are needed to preserve the unique

groups differed as much as 50%, which maintained the steep character of this fish fauna. At a secondary level, more field

slope of the total accumulation curve. Analyses of these studies are needed to finish documenting the ichthyofauna of

data argue strongly that continued collecting will increase the this amazing region.

size of the fauna known from the Tahuamanu-Manuripi

region. Because the species that represent new records for 350

Bolivia comprise more than 29% of all species captured, we

Cumulative Number of Species

expect that additional collecting will continue to uncover 300

new records for the country as well. These data exemplify

250

that the Upper Orthon basin is extremely diverse and may

prove more diverse than even the Río Mamore basin, which 200

has received vastly more collecting effort.

The biogeographic relationships of the Tahuamanu- 150

Manuripi region is difficult to ascertain, again because of 100

how little we know in general. There does seem to be a mix

of taxa representing three distinct distributional elements. 50

The first comprises widespread amazonian lowland species

0

from the north and the east of the Madeira basin: e.g.,

Serrasalmus rhombeus, Schizodon fasciatum, Anodus 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15

elongatus, Microschemobrycon geisleri, Cetopsorhamdia Time (Days)

fantasia, Pimelodus cf. altipinnis, Tatia altae, Electrophorus

electricus, and Rhabdolichops caviceps. The second Figure 3.1. Species accumulation curves for fishes collected

incorporates species found in black waters of the Guapore/ in the Ríos Tahuamanu, Nareuda, and Manuripi, Pando,

Itenez system that derive from the Brazilian Shield: e.g., Bolivia, 4 - 21 September, 1996. Symbols: Group 1

Hypopygus lepturus, Carnegiella strigata, Aphyocharax (squares), Group 2 (triangles), and combined (X).

alburnus, Hemigrammus cf. unilineatus, Pyrrhulina

australe, Nannostomus trifasciatus, Potamorhina latior, Economic Importance

Tatia aulopygia, Corydoras hastatus, Cichla monoculus, and

Aequidens cf. tetramerus. The third describes those species Many of the fishes found in the Upper Río Orthon basin are

in the small garapes that are typical for headwater habitats: valuable as commercial resources for food and for the

e.g., Chrysobrycon spp., Brachychalcinus copei, ornamental fish industry. We present a short discussion in

Bryconamericus cf. caucanus, Creagrutus sp., Cyphocharax order to stimulate immediate research into the potential of

spiluropsis, Piabucus melanostomus, Tyttocharax these resources to provide an economic alternative to other

tambopatensis, Corydoras trilineatus, Imparfinis stictonotus, activities that damage the environmental character of the

and Otocinclus mariae. region.

The discussions above show the nature of the unique- During the AquaRAP we employed local fisherman

ness of the ichthyofauna of the Tahuamanu-Manuripi river who were subsistence fisherman throughout the year and

basins. A relatively small region contains 63% of all the who fished commercially during the seasonal migrations.

freshwater species known from the Bolivian Amazon. The We also witnessed truck-side fish sales in Cobija and in

fauna comprises 87 species that have never been recorded Filadelfia and saw the following species for sale:

from Bolivia – a feature which does not seem to be an Pygocentrus nattereri, Pseudoplatystoma fasciatum,

artifact of sampling or collecting methods. The region Prochilodus nigricans, Curimata spp., Hydrolycus pectora-

contains an assemblage of fishes that may uniquely combine lis, Plagioscion squamosissimus, Mylossoma duriventris,

widespread amazonian species, with blackwater Brazilian and Myleus sp. We were told by the fishermen that the

shield species in addition to headwater species. Because we fishes of highest commercial value were the surubí,

never reached the asymptote of the species accumulation Pseudoplatystoma, and the serrasalmines, including both the

42 CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL Rapid Assessment Program

piranhas and the pacus. In our samples, we caught many 1999). Even though it was the dry season and at relatively

other species that are either consumed for subsistence or low water, there were still many suitable habitats for these

caught for sales according to our guides. That list included species. The gill net samples did not yield the quantity of

the following: Anodus elongatus, Cichla cf. monoculus, individuals for the commercially important species that

Cochliodon cochliodon, Crenicichla spp., Duopalatinus sp., would indicate bountiful populations, even though our

Hemisorubim platyrhynchos, Hoplias malabaricus, fishermen guided us to their favorite areas (with monetary

Megalechis thoracatus, Hypostomus spp., Leiarius exchange for the catch). In our experience from similar

marmoratus, Leporinus spp., Myleus sp., Pimelodus spp., habitats in other regions of the Amazon and Orinoco river

Pristobrycon sp., Rhamdia sp., Schizodon fasciatum, basins where fish populations are apparently healthy, the

Sorubim lima, and Triportheus angulatus. In that list the commercially important species are reasonably well

“spp.” refers to a number of species within the genus that represented in gill net samples even in the dry seasons. We

are eaten. Interestingly, the following armored catfishes are only suggest caution. And we recommend that the stocks

consumed in the Río Madeira basin of Brazil (Goulding, be surveyed immediately both within the Upper Río

1981) but were rejected as a source of food by our fisher- Orthon as well as downstream toward the Río Madeira.

men: Doras cf. carinatus, Pseudodoras niger, and Statements such as that by Walters et al. (1982) advocating

Liposarcus disjunctivus. across - the - board increase in fisheries are premature in

Our discussions with local fisherman including others in advance of the data on native stocks.

Puerto Rico indicated that the commercial food fisheries are Economic potential also exists for the establishment of

burgeoning in the Tahuamanu and Manuripi rivers. It was a harvest-based ornamental fishery. The extreme number of

not possible to obtain from our fishermen or from the truck- species, the number of cochas and inundated flooded

side sellers the annual totals for weight or value of the catch. habitats makes the Tahuamanu-Manuripi regions especially

However, the notion of increasing annual landings would not attractive. These habitats are easily collected while serving

seem to make sense relative to the local populations that we as natural critical rearing habitats for ornamental fishes.

encountered and interviewed for two reasons: i) the The ornamental fishes ranged from the common (e.g.,

population of Pando, while increasing, is doing so slowly; Moenkhausia sanctaefilomenae, Hemigrammus ocellifer) to

and ii) the Bolivian residents have largely settled the region ornamentals that are more highly prized, including the

from cattle rearing areas or from La Paz and do not have following: Astronotus crassipinnis, Apistogramma spp.,

strong traditions of fish consumption. Most of their Aequidens spp., Satanoperca cf. acuticeps, Eigenmannia

demand is for premium species, tiger catfishes and pacus, spp., Apteronotus albifrons, Gymnotus carapo, Hypopygus

species that are delicate in flavor. Apparently, much of the lepturus, Heptapterus longior, Imparfinis stictonotus,

catch is exported across the border to Brazil, and this Microglanis sp., Brachyrhamdia marthae, Cheirocerus

exportation appears to be unregulated. Sarmiento (1998) eques, Scoloplax cf. dicra, Peckoltia arenaria,

also noted a similar pattern of unregulated exportation of Parotocinclus sp., Otocinclus mariae, Hypostomus spp.,

several tons of fish per month with a slightly increasing Ancistrus spp., Agamyxis pectinifrons, Acanthodoras

demand from populations living along the Río Itenez. The cataphractus, Brochis splendens, Corydoras spp.,

mere fact that catches are not being monitored is reason for Bunocephalus spp., Dysichthys spp., Nannostomus

concern. trifasciatus, Pyrrhulina spp., Carnegiella spp., Tyttocharax

Peres and Terbourgh (1995) , Goulding (1980, 1981) spp., Poptella compressa, Phenacogaster spp.,

and Goulding et al. (1988) document not only the impor- Prionobrama filigera, Metynnis luna, Paragoniates

tance of rivers in structuring human settlements throughout alburnus, Iguanodectes spilurus, Hemigrammus spp.,

Amazonia but also the increasing dependence of humans on Hyphessobrycon spp. Chrysobrycon spp., Aphyocharax

aquatic resources for sustenance. At this time we cannot spp., Leporinus spp., Cynolebias spp., and Pterolebias

document the size of species-specific harvests that are spp.

sustainable for the future. There are no accurate data on the The most important areas within the region surveyed

nature of fish migration into the Tahuamanu-Manuripi for the ornamental fishes are the Upper Río Nareuda and

region. Many of the commercially important species such the Río Manuripi (Appendix 6). In some cases, trapped

as the curimatids and prochilodontids move out of tributar- interior flooded forest lakes (e.g., Appendix 8: B96-P2-42,

ies and forest habitats into the main rivers to spawn at the B96-P2-44) can be harvested entirely because these

beginning of the flooding cycle (Goulding, 1981). Many of ephemeral environments either dry completely or become

the larger catfishes migrate upstream to spawn and appar- anoxic. However, in the more permanent habitats the

ently ascend the cataracts in the upper Madeira into reproductive and population biologies of the ornamental

Bolivian waters (Goulding, 1981). The only relevant data fishes must be studied in order to support a sustainable

that we collected was that the abundance of the most enterprise.

favored species was relatively low (Machado-Allison et al.,

BULLETIN OF BIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT FIFTEEN December 1999 43

Critical Habitats channels also contain a diverse fauna with a number of

unique or rare elements (e.g., Cetopsorhamdia phantasia).

We identified a number of critical habitats that are required The Río Tahuamanu above Filadelfia contains a number of

for continued survival of freshwater fishes and maintenance rocky outcrops, including some small rapids and shallow

of the spectacular biodiversity. These are the same habitats regions with many downed logs. In the dry season the area

that support the growth and reproduction of economically near Aserradero was almost un-navigable because of the tree

valuable species. trunks and rapids. Such regions are prime candidates for

The habitats are described in detail in the companion spawning areas of the commercially important, large,

paper (Machado Allison et al., 1999). However, they fall pimelodid catfishes (e.g., Pseudoplatystoma fasciatum,

into three main classes: i) flooded areas; ii) small tributaries; Leiarius marmoratus) (Barthem and Goulding, 1997). As

and iii) main channels. The flooded areas comprise the most development continues towards the Peruvian border,

critical and highly endangered areas, including the varzea pressure may be exerted to channelize the river to permit

(flooded forest), cochas, swamps, forest lakes, etc. These shipment of supplies or equipment up river.

areas provide nursery grounds for perhaps 66% of the

species that we captured (Goulding, 1980, 1981; Lowe-

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

McConnell, 1987). Furthermore, many species, including

the pacus, feed on the fruits and nuts, including the Brazil

The following are the major conclusions and recommen-

nuts, dropped by the plants into the water (see Goulding,

dations that derive from our studies:

1980, 1981). Goulding (1981) characterizes the Brazilian

portion of the Río Madeira as having a relatively narrow

1. The region of the Río Tahuamanu-Río Manuripi,

flood plain and margin. This is certainly true for the Ríos

Upper Río Orthon basin, Pando, Bolivia is a potential

Tahuamanu, Muymanu, Nareuda and Manuripi in the areas

hotspot for the biodiversity of freshwater fishes. We

that we surveyed. Given such a narrow flood plain, there is

discovered 313 species in the region, of which 87 species

little buffer between logging and ranching activities and these

represent new records for Bolivia. This region contains 63%

critical flood zones. Extended development from Puerto

of the fishes found in the Bolivian Amazon and 49% of the

Rico, Filadelfia and Aserradero threaten this flood plain

species found in the entire country.

zone.

In the Upper Tahuamanu and Upper Nareuda there

2. The diversity within the Río Tahuamanu-Río Manuripi

were many smaller streams (garapes) and tributaries with

region will increase with increased sampling. The collecting

both black and white water conditions. These smaller

efforts at the end of the expedition were still increasing the

habitats are highly threatened by deforestation and cattle

species known from the area at a rate of 10.5 species per

ranching. A number of the garapes crossing the main road

day. An asymptote was not reached.

and on cattle ranches are completely denuded of riparian

vegetation. Furthermore, one team walked through dense

3. The ichthyofauna is a unique assemblage of species. It

forests into a number of forest streams and neither captured

appears to contain three distinct biogeographical elements as

nor saw any fishes, crustaceans or aquatic insects in crystal

follows: i) widespread lowland Amazonian elements from

clear water with sand bottoms. These streams were

the north and east; ii) Brazilian Shield elements from the Río

downstream from a ranch that was recently cleared and

Guapore/Itenez; and iii) headwater elements.

burned. We could only speculate that ashes, which are toxic

to aquatic organisms (N. Menezes, pers. comm.), or

4. The freshwater fishes are economically valuable. Many

pesticides poisoned these streams.

of the species are currently used for subsistence or commer-

These upper areas are highly diverse. We captured 168

cial fishery and have a high value. The food fishery may

species in the Upper Tahuamanu and the Upper Nareuda,

largely be for exportation. The ornamental fishes have a

slightly more than half of all the species we discovered

very high value.

(Appendix 6). Seventy-one species were found to inhabit

both the Upper Tahuamanu and Upper Nareuda, but 30

5. Populations and stocks of commercially exploited

species were found only in these upper regions. These

fishes need to be studied immediately across the Río

upper regions contain habitats that are similar to headwater

Madeira basin in Bolivia and coordinated with Brazil. The

areas with a unique and diverse fauna. These are among the

exploitation of local fishes for exportation may be putting

most threatened habitats due to logging, deforestation and

undo pressure on stocks. Catch data from the expedition do

ranching.

not support viable populations living in the region.

The main river channels are not habitats that are usually

focused upon. However, as pointed out above, the principal

44 CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL Rapid Assessment Program

6. We recommend the development of fisheries for local Lauzanne, L., G. Loubens, and B. Le Guennec. 1991. Liste

consumption and the careful regulation of catches for commentée des poissons de l’Amazonie bolivienne.

exportation. Revista Hydrobiologia Tropical 24:61-76.

7. The potential to develop local fishery for ornamental López-Rojas, H., J. G. Lundberg, and E. Marsh. 1984.

species should be studied. Many species are available Design and operation of a small trawling apparatus

locally that are not well - represented in the aquarium trade, for use with dugout canoes. North American Journal

but population biology and life histories need to be studied of Fisheries Management 4: 331-334.

to guarantee sustainability.

Lowe-McConnell, R. H. 1987. Ecological studies in tropical

8. Zones of critical habitats with varzea, cochas, main fish communities. Cambridge University Press, New

channels and upland areas should be protected. Rather than York. 382 pp.

the formation of a park, consider multiple use zones with

some habitats restricted for modification. Protect the Machado-Allison, A., J. Sarmiento, P.W. Willink, N.

narrow floodplain. Menezes, H. Ortega, and S. Barrera. 1999. Diversity

and abundance of fishes and habitats in the Río

9. Programs should be developed to work with local Tahuamanu and Río Manuripi basins. In Chernoff, B.,

fisherman and floodplain residents to explain the relation- and P.W. Willink (eds.). A biological assessment of

ships between maintenance of habitats and biodiversity of of the Upper Río Orthon basin, Pando, Bolivia. Pp.

fishes. Educational programs should also be developed and 47-50. Bulletin of Biological Assessment No. 15,

should involve local residents and fishermen in monitoring Conservation International, Washington, D.C.

stocks and habitats. These programs should promote the

learning of the different fishes and how to recognize new or Mago-Leccia, F. 1994. Electric fishes of the continental

unusual species that should be brought to the attention of waters of America. Biblioteca de la Academia de

scientists. Ciéncias Físicas, Matematicas y Naturales, Volume

XXIX, Caracas, Venezuela.

LITERATURE CITED

Peres, C. A., and J. W. Terborgh. 1995. Amazonian nature

reserves: an analysis of the defensibility status of

Barthem, R., and M. Goulding. 1997. The catfish

existing conservation units and design criteria for the

connection: ecology, migration, and conservation of

future. Conservation Biology 9: 34-45.

Amazon predators. Biology and Resource

Management in the Tropics Series, Columbia

Santos, G. M., M. Jegu, and B. Merona. 1984. Catálogo de

University Press, New York.

peixes comerciales do baixo Tocantins. Elcectronorte/

CNPq/INPA, Manaus. 83 pp.

Eigenmann, C. H., and G. S. Myers. 1929. The American

Characidae. Memoirs of the Museum of

Sarmiento, J. 1998. Ichthyology of Parque Nacional Noel

Comparative Zoology, Harvard, 43: 429-574.

Kempff Mercado., Appendix 5. In Killeen, T.J. and

T. S. Schulenberg (eds.) A biological assessment of

Gery, J. 1977. Characoids of the world. T.F.H. Publications,

Parque Nacional Noel Kempff Mercado. Pp. 168-

New Jersey. 672 pp.

180. RAP Working Papers No. 10. Conservation

International, Washington, D.C.

Goulding, M. 1980. The fishes and the forests: explorations

in Amazonian natural history. University of

Stewart, D. J. 1985. A new species of Cetopsorhamdia

California Press, Los Angeles. 280 pp.

(Pisces: Pimelodidae) from the Río Napo Basin of

Eastern Ecuador. Copeia 1985: 339-344.

Goulding, M. 1981. Man and fisheries on an Amazon

frontier. Dr. W Junk Pub., Boston. 137 pp.

Stewart, D. J., R. Barriga, and M. Ibarra. 1987. Ictiofauna de

la cuenca del Río Napo, Ecuador Oriental: lista

Goulding, M., M. L. Carvalho, and E. G. Ferreira. 1988. Río

anotada de especies. Revista del Politecnica 12: 9-63.

Negro: rich life in poor water: Amazonian

diversity and foodchain ecology as seen through

fish communities. SPB Academic Publishing, The

Hague, Netherlands. 200 pp.

BULLETIN OF BIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT FIFTEEN December 1999 45

Vari, R. P. 1992. Systematics of the Neotropical characiform

genus Curimatella Eigenmann and Eigenmann

(Pisces: Ostariophysi) with summary comments on

the Curimatidae. Smithsonian Contributions to

Zoology 533: 1-48.

Walters, P. R., R. G. Poulter, and R. R. Coutts. 1982.

Desarrollo pesqueiro de la Region Amazonica en

Bolivia. London: Tropical Products Institute,

Overseas Development Agency.

Welcomme, R.L. 1990. Status of fisheries in South American

rivers. Interciencia 15: 337-345.

46 CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL Rapid Assessment Program

You might also like

- Batching Plant Project: Initial Environmental Examination (Iee) ReportDocument16 pagesBatching Plant Project: Initial Environmental Examination (Iee) ReportavieNo ratings yet

- Interpreting NietzscheDocument227 pagesInterpreting NietzscheCamilo Lelis100% (3)

- Unpublished Writings From The Period of Unfashionable Observations (PDFDrive)Document530 pagesUnpublished Writings From The Period of Unfashionable Observations (PDFDrive)Juliana Monteiro100% (1)

- Risk Based Joint Inspection FormatDocument64 pagesRisk Based Joint Inspection Formatredracer002No ratings yet

- Human, All Too Human II and Unpublished Fragments From The Period of Human, All Too Human II (Spring 1878-Fall 1879) (PDFDrive)Document650 pagesHuman, All Too Human II and Unpublished Fragments From The Period of Human, All Too Human II (Spring 1878-Fall 1879) (PDFDrive)Juliana MonteiroNo ratings yet

- CONSTÂNCIO, João BRANCO, Maria João Mayer. Nietzsche On Instinct and Language PDFDocument319 pagesCONSTÂNCIO, João BRANCO, Maria João Mayer. Nietzsche On Instinct and Language PDFPRBRNo ratings yet

- Taxonomic Review of Azorean InvertebratesDocument25 pagesTaxonomic Review of Azorean InvertebratesJN GPNo ratings yet

- Medusas en MexicoDocument12 pagesMedusas en MexicoSiervoupNo ratings yet

- Palma Et Al. - 2014 - Biodiversity and Spatial Distribution of Medusae IDocument15 pagesPalma Et Al. - 2014 - Biodiversity and Spatial Distribution of Medusae IEverton GiachiniNo ratings yet

- CheckList Article 53857 en 1Document4 pagesCheckList Article 53857 en 1Jonathan DigmaNo ratings yet

- Apteronotus MagdalenensisDocument3 pagesApteronotus MagdalenensisLuis Carlos Villarreal DiazNo ratings yet

- Ramirez 1981 Copepods 383ÑDocument12 pagesRamirez 1981 Copepods 383ÑJosé Vélez TacuriNo ratings yet

- Estructuratrficadelospecesenarroyosdel Corralde San Luis 2016Document21 pagesEstructuratrficadelospecesenarroyosdel Corralde San Luis 2016Baltazar Calderon RoncalloNo ratings yet

- Reproducción Del Pez Erizo, Diodon Holocanthus (Pisces: Diodontidae) en La Plataforma Continental Del Pacífico Central MexicanoDocument16 pagesReproducción Del Pez Erizo, Diodon Holocanthus (Pisces: Diodontidae) en La Plataforma Continental Del Pacífico Central MexicanoChristian Moises CasasNo ratings yet

- Structure and composition of the ichthyofauna of streams of the Rio Paranapanema riverDocument31 pagesStructure and composition of the ichthyofauna of streams of the Rio Paranapanema riverWhite Scorpion 4002No ratings yet

- Prieto-Piraquive Et Al 2023. Food Habits in Fish AmazonDocument14 pagesPrieto-Piraquive Et Al 2023. Food Habits in Fish Amazoncp190206No ratings yet

- Características Limnológicas y Estructura de La Ictiofauna de Una Laguna Asociada Al Rio QuintoDocument12 pagesCaracterísticas Limnológicas y Estructura de La Ictiofauna de Una Laguna Asociada Al Rio QuintoDOLMA BALCAZARNo ratings yet

- Peces de La Laguna Cormorán, Parque Nacional Sangay, EcuadorDocument10 pagesPeces de La Laguna Cormorán, Parque Nacional Sangay, EcuadorTatiana GaonaNo ratings yet

- Seasonal patterns of fish assemblage in a mangrove swamp in Baja California Sur, MexicoDocument10 pagesSeasonal patterns of fish assemblage in a mangrove swamp in Baja California Sur, MexicoMyk Twentytwenty NBeyondNo ratings yet

- Abundance and Distribution of Loligo Sanpaulensis Brakoniecki 1984 (Cephalopoda, Loliginidae) in Southern BrazilDocument8 pagesAbundance and Distribution of Loligo Sanpaulensis Brakoniecki 1984 (Cephalopoda, Loliginidae) in Southern BrazilJosé Milton Andriguetto FilhoNo ratings yet

- Astyanax Pampa Perez 2008Document3 pagesAstyanax Pampa Perez 2008homonota7330100% (2)

- Fishes From The Las Piedras River, Madre de Dios Basin, Peruvian Amazon - Carvalho Et Al. - 2012Document47 pagesFishes From The Las Piedras River, Madre de Dios Basin, Peruvian Amazon - Carvalho Et Al. - 2012Dayvis RH MontesNo ratings yet

- Freshwater decapod crustaceans of southeast BahiaDocument30 pagesFreshwater decapod crustaceans of southeast BahiaAndré Ramos CostaNo ratings yet

- Belajar MenganalisaDocument19 pagesBelajar MenganalisaAnggi TasyaNo ratings yet

- Check List: Bivalves and Gastropods of Tubbataha Reefs Natural Park, PhilippinesDocument12 pagesCheck List: Bivalves and Gastropods of Tubbataha Reefs Natural Park, PhilippinesMarc AlexandreNo ratings yet

- Dieta Natural Habitos AlimentaresDocument10 pagesDieta Natural Habitos AlimentaresDaniel CostaNo ratings yet

- Fishes of The Lagunas Encadenadas (Province of Buenos Aires, Argentina), A Wetland of International ImportanceDocument6 pagesFishes of The Lagunas Encadenadas (Province of Buenos Aires, Argentina), A Wetland of International ImportancepedroNo ratings yet

- Equinod Sur Golfo-Mexico 2008Document14 pagesEquinod Sur Golfo-Mexico 2008Franvier Val-SanNo ratings yet

- Paper Hemibrycon 2006Document8 pagesPaper Hemibrycon 2006carlochessNo ratings yet

- Comportamiento de La Nutria en La Guajira 2019Document14 pagesComportamiento de La Nutria en La Guajira 2019MariaVictoriaCastañedaUsugaNo ratings yet

- Zamudio Et Al - Hábitos Alimentarios de Diez Especies de Peces Del Piedemonte Del Departamento CasanareDocument14 pagesZamudio Et Al - Hábitos Alimentarios de Diez Especies de Peces Del Piedemonte Del Departamento CasanareHECTORNo ratings yet

- Peces de La Fauna de Acompañamiento en La Pesca Industrial de Camarón en El Golfo de California, MéxicoDocument18 pagesPeces de La Fauna de Acompañamiento en La Pesca Industrial de Camarón en El Golfo de California, MéxicoDirk Hans Krakaur FloranesNo ratings yet

- 38 Aguilera DistributionDocument22 pages38 Aguilera DistributionMisterJanNo ratings yet

- Art 25Document9 pagesArt 25Mafer CabezasNo ratings yet

- 09 Susan Macro FaunaDocument12 pages09 Susan Macro Faunaanon_487078862No ratings yet

- Articulo PDFDocument9 pagesArticulo PDFDaniel Miguel Manchego RamosNo ratings yet

- Carpio, Carl Lawrence R. - Additional ActivityDocument7 pagesCarpio, Carl Lawrence R. - Additional ActivityCarl Lawrence R. CarpioNo ratings yet

- Seasonality of habitat use, mortality and reproduction of the Vulnerable Antillean manateeDocument8 pagesSeasonality of habitat use, mortality and reproduction of the Vulnerable Antillean manateePremunicion ChanelNo ratings yet

- TMP 756Document16 pagesTMP 756FrontiersNo ratings yet

- Biology and Conservation of The Freshwater Turtles and Tortoises of PeruDocument14 pagesBiology and Conservation of The Freshwater Turtles and Tortoises of PeruGeorge A. LoayzaNo ratings yet

- Preliminary Observations On Habitat Use Patterns oDocument8 pagesPreliminary Observations On Habitat Use Patterns oetejada00No ratings yet

- 11 NERIA ComDocument12 pages11 NERIA ComEric JacksonNo ratings yet

- Ayón Et Al PK Review 2008 PDFDocument18 pagesAyón Et Al PK Review 2008 PDFJesus JasNo ratings yet

- Estructura Trófica de Los Peces en Arroyos Del Corral de San Luis, Cuenca Del Bajo Magdalena, Caribe, ColombiaDocument18 pagesEstructura Trófica de Los Peces en Arroyos Del Corral de San Luis, Cuenca Del Bajo Magdalena, Caribe, ColombiaKate HowardNo ratings yet

- Cunha Et AlDocument9 pagesCunha Et Alapi-3828346No ratings yet

- Akmentins 2020 Alimentacion de TelmatobiusDocument7 pagesAkmentins 2020 Alimentacion de Telmatobiustuvieja entangaNo ratings yet

- Notes on jaguarundi diet in Belize and Guatemala lowlandsDocument5 pagesNotes on jaguarundi diet in Belize and Guatemala lowlandsMaría José TorallaNo ratings yet

- Species Composition, Distribution, Biomass Trends and Exploitation ofDocument16 pagesSpecies Composition, Distribution, Biomass Trends and Exploitation ofnikka csmNo ratings yet

- MEXICAN REPORT ON SEAHORSE SPECIES AND FISHERIESDocument15 pagesMEXICAN REPORT ON SEAHORSE SPECIES AND FISHERIESHéctor Quintanilla HerebiaNo ratings yet

- Abundancia, Tamaño y Estructura Poblacional Del Tiburón Punta Blanca de Arrecife, Triaenodon Obesus (Carcharhiniformes: Carcharhinidae), en Bahía Chatham, Parque Nacional Isla Del Coco, Costa RicaDocument8 pagesAbundancia, Tamaño y Estructura Poblacional Del Tiburón Punta Blanca de Arrecife, Triaenodon Obesus (Carcharhiniformes: Carcharhinidae), en Bahía Chatham, Parque Nacional Isla Del Coco, Costa RicaDayanna MeraNo ratings yet

- Baumgartner & Greenberg 1985Document23 pagesBaumgartner & Greenberg 1985DIEGO ANDRES CADENA DURANNo ratings yet

- Diatom genera from Colombian and Peruvian Amazon rivers and lakesDocument19 pagesDiatom genera from Colombian and Peruvian Amazon rivers and lakesBibiana DuarteNo ratings yet

- 2008 Maldonado-Ocampoetal - ChecklistofthefreshwterfishofColombiaDocument96 pages2008 Maldonado-Ocampoetal - ChecklistofthefreshwterfishofColombiaJuan MNo ratings yet

- Francisco J. Fernández-Rivera Melo, Héctor Reyes-Bonilla, Jorge A. López-Rocha, and Carlos A. SALOMON-AGUILARDocument9 pagesFrancisco J. Fernández-Rivera Melo, Héctor Reyes-Bonilla, Jorge A. López-Rocha, and Carlos A. SALOMON-AGUILARPutri AmaliaNo ratings yet

- Estructura Trófica de Los Peces en Arroyos Del Corral de San Luis, Cuenca Del Bajo Magdalena, Caribe, ColombiaDocument19 pagesEstructura Trófica de Los Peces en Arroyos Del Corral de San Luis, Cuenca Del Bajo Magdalena, Caribe, ColombiaBaltazar Calderon RoncalloNo ratings yet

- Scarabino Et Al RevMACN 20 (2) 251-270 2018Document20 pagesScarabino Et Al RevMACN 20 (2) 251-270 2018aliciacardozo63No ratings yet

- tmpB8A7 TMPDocument26 pagestmpB8A7 TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- Changes in The Structure of A Shallow Sandy-Beach Community in Peru During An El Niño Event Arntz 1987Document15 pagesChanges in The Structure of A Shallow Sandy-Beach Community in Peru During An El Niño Event Arntz 1987Eduardo LopezNo ratings yet

- Silva-Oliveira Et Al. 2023-Knodus BorariDocument7 pagesSilva-Oliveira Et Al. 2023-Knodus BorariCárlison OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Dixon y Soini (1977) The Reptiles of The Upper Amazon Basin, Iquitos Region, Perú. Part II Crocodilians, Turtles and SnakesDocument93 pagesDixon y Soini (1977) The Reptiles of The Upper Amazon Basin, Iquitos Region, Perú. Part II Crocodilians, Turtles and SnakesDiego LoboNo ratings yet

- 1999 Perales-Rayaetal LoligovulgarisDocument11 pages1999 Perales-Rayaetal LoligovulgarisLost LiveNo ratings yet

- Species composition of macroinvertebrates in Philippine coveDocument10 pagesSpecies composition of macroinvertebrates in Philippine coveJfkfkfjfNo ratings yet

- EchinoideaDocument35 pagesEchinoideaEvika Fatmala DeviNo ratings yet

- Cyclic Phenomena in Marine Plants and Animals: Proceedings of the 13th European Marine Biology Symposium, Isle of Man, 27 September - 4 October 1978From EverandCyclic Phenomena in Marine Plants and Animals: Proceedings of the 13th European Marine Biology Symposium, Isle of Man, 27 September - 4 October 1978No ratings yet

- Parmana: Prehistoric Maize and Manioc Subsistence Along the Amazon and OrinocoFrom EverandParmana: Prehistoric Maize and Manioc Subsistence Along the Amazon and OrinocoNo ratings yet

- Niilismo e Filosofia5Document21 pagesNiilismo e Filosofia5Juliana MonteiroNo ratings yet

- Word ArtDocument1 pageWord ArtJuliana MonteiroNo ratings yet

- Let Education HurtDocument16 pagesLet Education HurtJuliana MonteiroNo ratings yet

- Fritz K. Ringer - The Decline of The German MandarinsDocument538 pagesFritz K. Ringer - The Decline of The German MandarinsJuliana MonteiroNo ratings yet

- Nietzsche On Instinct and LanguageDocument9 pagesNietzsche On Instinct and LanguageJuliana MonteiroNo ratings yet

- Huddleston 2014Document27 pagesHuddleston 2014Juliana MonteiroNo ratings yet

- GARRARD Enlightenment NietzscheDocument15 pagesGARRARD Enlightenment NietzscheJuliana MonteiroNo ratings yet

- Nietzsches Vision Einer Neuen AristokraDocument12 pagesNietzsches Vision Einer Neuen AristokraJuliana MonteiroNo ratings yet

- Ilustração e Modernidade PDFDocument65 pagesIlustração e Modernidade PDFJuliana MonteiroNo ratings yet

- Topic: Farmers Suicide in IndiaDocument4 pagesTopic: Farmers Suicide in IndiaJash ParmarNo ratings yet

- Balanced FertilizationDocument44 pagesBalanced FertilizationChristian Tabanera NavaretteNo ratings yet

- DissertationDocument70 pagesDissertationSonu MohapatraNo ratings yet

- Annex 4Document3 pagesAnnex 4siddhant singhNo ratings yet

- Zero Energy Building Materials and DesignDocument15 pagesZero Energy Building Materials and DesignNipesh MAHARJANNo ratings yet

- LAS 7 SCIENCE 10 BS 3 Samaniego LeisethDocument6 pagesLAS 7 SCIENCE 10 BS 3 Samaniego LeisethGail MoraNo ratings yet

- BSBSUS401 SAT Task 3 Performance Improvement Implementation Ver. 1 2 PDFDocument14 pagesBSBSUS401 SAT Task 3 Performance Improvement Implementation Ver. 1 2 PDFOchaOngNo ratings yet

- Production Equipment and Facilities Postharvest Equipment and FacilitiesDocument49 pagesProduction Equipment and Facilities Postharvest Equipment and FacilitiesRonel Dimaya CañaNo ratings yet

- NLC India Limited: Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Policy Revision-3Document13 pagesNLC India Limited: Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Policy Revision-3Richard SonNo ratings yet

- Ethno Biology Group One AssignmentDocument8 pagesEthno Biology Group One AssignmentDessalew MeneshaNo ratings yet

- 2021CHIKO E-Catalogue (5793)Document48 pages2021CHIKO E-Catalogue (5793)Shafik AlieNo ratings yet

- 4a. PDC - 55 MLD MPS - Rev1Document6 pages4a. PDC - 55 MLD MPS - Rev1epe civil1No ratings yet

- 2.1 Species and PopnDocument60 pages2.1 Species and PopnKip 2No ratings yet

- Teaching Poetry Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesTeaching Poetry Lesson PlanJJ Delegero Bergado100% (1)

- PT BALIKPAPAN ENVIRONMENTAL SERVICES: Total Waste Management SolutionsDocument38 pagesPT BALIKPAPAN ENVIRONMENTAL SERVICES: Total Waste Management Solutionsmekarsari retnoNo ratings yet

- 1421 PQ Contract 2 WWTP Publication 200508 VVJDocument2 pages1421 PQ Contract 2 WWTP Publication 200508 VVJLuminita NeteduNo ratings yet

- W9a1 PDFDocument4 pagesW9a1 PDFbosscaptainNo ratings yet

- KEY high strength cast iron pipes and fittings product guideDocument21 pagesKEY high strength cast iron pipes and fittings product guideRonnie Au YeungNo ratings yet

- TCPA EIA Screening Matrix 2017 Regs Nov 2021Document8 pagesTCPA EIA Screening Matrix 2017 Regs Nov 2021Mohammed Ali QaziNo ratings yet

- Sustainability 14 05077Document25 pagesSustainability 14 05077Mohit SharmaNo ratings yet

- Data Centre Training Roadmap: A Quick Guide For Data Centre Career DevelopmentDocument5 pagesData Centre Training Roadmap: A Quick Guide For Data Centre Career Developmentxuyen tranNo ratings yet

- RENK Hydropower en PDFDocument11 pagesRENK Hydropower en PDFhamdaNo ratings yet

- User Manual Panel Tank FRPDocument7 pagesUser Manual Panel Tank FRPwika mepNo ratings yet

- 201210221219130.laporan Eia Damansara-Shah Alam Elevated Highway-Ukmpakarunding PDFDocument480 pages201210221219130.laporan Eia Damansara-Shah Alam Elevated Highway-Ukmpakarunding PDFmanimaran75100% (1)

- Gender and LeadershipDocument5 pagesGender and Leadershipsushant tewariNo ratings yet

- Case Body Shop VisualCasePresentationDocument28 pagesCase Body Shop VisualCasePresentationHanna AbejoNo ratings yet

- Unit 1: Q2e Listening & Speaking 2: Audio ScriptDocument2 pagesUnit 1: Q2e Listening & Speaking 2: Audio ScriptAnh DangNo ratings yet

- FLSMIDTH - Wave Grate For The SF Cross-Bar Cooler PDFDocument4 pagesFLSMIDTH - Wave Grate For The SF Cross-Bar Cooler PDFEduart Guerrero100% (1)