Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Copia de LanePullenEiseleJordan2002

Uploaded by

Angela WeaslyOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Copia de LanePullenEiseleJordan2002

Uploaded by

Angela WeaslyCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/261063471

Lane, H. B., & Pullen, P. C. (2004). Phonological awareness assessment and

instruction: A sound beginning. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Book · January 2004

CITATIONS READS

12 1,311

1 author:

Paige C. Pullen

University of Florida

68 PUBLICATIONS 1,391 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

IES Tier 2 Project IVI View project

Kauffman, J. M., Hallahan, D. P., and Pullen, P. C. (Eds.) Handbook of Special Education, Second Edition, New York: Routledge View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Paige C. Pullen on 01 January 2019.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Abstract. The article addresses translating

phonological awareness research for class-

room reading instruction. It presents a practi-

cal overview of phonological awareness devel-

opment and its relationship to beginning

reading, including a synopsis of findings of

recent research and an explanation of the

development of phonological skills. It presents

methods for formal and informal assessment

of children’s phonological awareness and

describes strategies for classroom-based

instruction in phonological skills with emer-

Preventing Reading gent readers.

Failure: Phonological R eading is a foundation skill for school

learning and life learning—the ability

to read is critical for success in modern

Awareness Assessment society. Learning to read is one of the most

important events in a child’s school career

and Instruction (Anderson, Hiebert, Scott, & Wilkinson,

1985; Lyon, 1999; National Reading

Panel, 2000). Unfortunately, many chil-

dren experience difficulties in the early

stages of learning to read that become bar-

riers to later reading and learning. A pri-

HOLLY B. LANE, PAIGE C. PULLEN, MARY R. EISELE, mary focus of recent research in educa-

and LuANN JORDAN tion, therefore, has been the prevention of

early reading problems (Adams, 1990;

Snow, Burns, & Griffin, 1998; Torgesen,

1998). One area of beginning reading

research that has received enormous atten-

tion in the professional literature is phono-

logical awareness. This research has been

called “a scientific success story”

(Stanovich, 1987) because phonological

awareness has been shown to be both a

reliable predictor of reading achievement

and a key to beginning reading acquisition

(Smith, Simmons, & Kame’enui, 1995).

What Is Phonological Awareness?

Phonological awareness can be defined

as conscious sensitivity to the sound

structure of language. Children with

strong phonological awareness can detect,

match, blend, segment, and manipulate

speech sounds. Such facility with the

sounds of spoken language enables chil-

dren to learn more readily how to apply

these skills to decode print. An under-

standing of phonemes, the smallest

Holly B. Lane is an assistant professor in the Department of Special Education detectable unit of sound in spoken lan-

at the University of Florida, Gainesville. Paige C. Pullen is an assistant pro- guage, is essential to the understanding of

fessor in the Department of Curriculum, Instruction, and Special Education at grapheme-phoneme (letter-sound) rela-

the University of Virginia, Charlottesville. Mary R. Eisele is a freelance edu- tionships. Numerous studies have demon-

cation consultant in Naples, Florida. LuAnn Jordan is an assistant professor strated the importance of phonological

in the Department of Counseling and Special Education at the University of awareness, particularly at the phoneme

North Carolina-Charlotte. level, as the foundation for skilled decod-

Vol. 46, No. 3 PREVENTING SCHOOL FAILURE 101

ing and, therefore, for fluent reading 1995; National Reading Panel, 2000) have

(Blachman, Tangel, Ball, Black, & yielded several important generalizations:

McGraw, 1999; Cornwall, 1992; Lenchn-

1. Phonological awareness is directly

er, Gerber, & Routh, 1990; Liberman &

related to reading ability.

Shankweiler, 1985; Pratt & Brady, 1988;

2. Although the relationship is recipro-

Wagner & Torgesen, 1987).

cal, phonological awareness precedes

Phonological awareness tasks have

skilled decoding.

been shown to be excellent predictors of

3. Phonological awareness is a reliable

reading ability or reading disability. That

predictor of later reading ability.

is, children who perform well on tasks of

4. Deficits in phonological awareness

phonological awareness typically are or

are usually associated with deficits in

will become good readers, but children

reading.

who perform poorly on them are or will

5. Early language experiences play an

become poor readers (Blachman, 1991;

important role in the development of

Catts, 1991; Perfetti, 1991; Perfetti, Beck,

phonological awareness.

Bell, & Hughes, 1987; Snow et al., 1998;

6. Early intervention can promote the

Stanovich, 1986, 1992; Torgesen, Wagner,

development of phonological awareness.

& Rashotte, 1997). To benefit from

7. Improvements in phonological

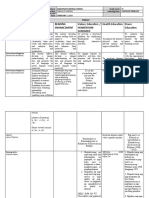

instruction in decoding and spelling, a FIGURE 1. Phonological awareness can

awareness can and usually do result in be illustrated as an umbrella term that

child must have a fundamental level of

improvements in reading ability. comprises four levels. Phonemic

phonological awareness (Chard & Dick-

awareness is an understanding of the

son, 1999; National Reading Panel, 2000). Phonological Skills and Developmental sound structure of language at the

Many educators confuse the terminol- Levels phoneme level.

ogy related to this research. In particular,

the terms phonological awareness, Several skills that are commonly asso-

phonemic awareness, and phonics are ciated with beginning reading instruction

is typically achieved at a very young age.

sometimes used interchangeably. As pre- help children develop phonological

The linguistic play of young children,

awareness. Typically, the first phonologi-

viously stated, phonological awareness is including rhyming and the generation of

cal skill that children master is the ability

a child’s sensitivity to the sound structure nonsense words, provides evidence of

to rhyme. Very young children may also

of language. Phonemic awareness refers this early level of phonological awareness

master skills such as phoneme detection

to a child’s ability to manipulate individ- (Bradley, 1988). When a child utters a

and sound matching with little instruc-

ual sounds (phonemes) within words. single word that he has only heard in

tion. More advanced phonological skills

Phonics is an instructional approach used combination with other words, he is

such as phoneme deletion, blending, and

to help children make sense of the con- demonstrating the word level of phono-

segmentation pose problems for many

nection between sounds and letters. Each logical awareness.

emergent readers. Most instruction

is important to early reading instruction.

designed to increase phonological aware- Syllable level. Syllables are the most eas-

Phonological Awareness Research ness emphasizes these difficult skills ily distinguishable units within words.

(activities designed to enhance these Most children acquire the ability to seg-

Phonological awareness has gained

skills will be described in detail in a sub- ment words into syllables with minimal

considerable attention in educational

sequent section). instruction (Liberman, Shankweiler, &

research during the last 15 years. The pri-

The levels of phonological awareness Liberman, 1989; Lundberg, 1988).

mary attraction to this relatively new area

development are associated with the dif- Activities such as clapping, tapping, and

of reading research is the repeated positive

ferent phonological components of spo- marching are often used to develop sylla-

results in studies of phonological aware-

ken language, including words, syllables, ble awareness. This level of phonological

ness interventions. Among the numerous

onsets and rimes, and phonemes (Blach- awareness is useful for initial instruction

reliable predictors of later reading perfor-

man, 1991; Smith, 1995). In Figure 1, we in detection, segmentation, blending, and

mance (e.g., socioeconomic status, moth-

depict phonological awareness as an manipulation of phonological compo-

er’s education) that educational

umbrella term that includes awareness at nents of language. The ability to detect,

researchers have identified phonological

each level of spoken language. Effective segment, and count syllables is more

awareness is one of the few that educators

assessment and instruction should important to reading acquisition than the

are able to influence significantly.

address the various levels of phonological ability to manipulate and transpose them

Numerous studies of phonological

awareness development. In the following (Adams, 1990).

awareness have contributed to the knowl-

sections, we describe each of these four

edge base in this area. These studies can Onset and rime level. The onset-rime or

levels of phonological awareness.

and should inform future educational intrasyllabic level of phonological aware-

research and practice. Syntheses of this Word level. The awareness that the speech ness is an intermediate and instructionally

research (see, for example, Smith et al., flow is a compilation of individual words useful level of analysis between the sylla-

102 PREVENTING SCHOOL FAILURE Spring 2002

ble and the phoneme (Adams, 1990). The blended in such a way that one phoneme’s Yopp (1988) investigated some of the most

onset is the part of the syllable that pre- production is influenced by the surround- commonly used measures of phonological

cedes the vowel (e.g., the /k/ in cat, the /br/ ing phonemes. For example, the /k/ is awareness and determined that the relia-

in brown). The rime is the rest of the sylla- formed in slightly different ways in the bility and validity of measurement tasks

ble (e.g., the /og/ in dog, the /ack/ in black). words cat and cot due to the influence of were greatest when a combination of mea-

Because a syllable must contain a vowel, the vowel that follows it. Because phone- sures was employed.

all syllables must have a rime, but not all mic analysis requires the reader to detect,

syllables have an onset (e.g., and, out, or). segment, and manipulate individual Group Assessment

Treiman (1985) found that children phonemes, it is a much more sophisticat- Several methods have been developed

make more errors with consonants at the ed task and, consequently, a much more for group screening and assessment of

end of words or with consonant blends difficult task than either syllabic or intra- phonological skills. Tests of invented

than with initial or medial consonants. syllabic analysis (Treiman, 1991, 1992). spelling can be administered in a group

This finding suggests that children natu- setting, and the analysis of children’s

rally segment words at neither the sylla- Assessing Phonological Awareness attempts to spell words provides the

ble nor the phoneme level, but at the intra- Educators face the formidable challenge teacher with information about their abil-

syllabic level. In addition, most children of determining which children have weak- ity to segment phonemes, their knowl-

spell rimes more accurately than individ- nesses in phonological awareness and, edge of the alphabet, and their under-

ual vowel sounds, which illustrates the therefore, which children are likely to standing of letter-sound correspondences

level at which they are attending. Onset- develop reading problems. Several ways to (Invernizzi, Meier, Swank, & Juel, 1998;

rime segmentation skill is an essential assess phonological awareness have been Moats, 2000; Snow et al., 1998). Mann,

component of phonological awareness developed. Which method to use should be Tobin, and Wilson (1987) have advocated

(Adams, 1990; Goswami & Mead, 1992). determined based on the number of chil- the use of children’s invented spellings as

Instruction at the onset-rime level is an dren to be assessed, the amount of existing a tool for screening phonological aware-

important step for many childen information about the children, and the ness. They developed a system for scor-

(Treiman,1985, 1991, 1992). Because amount of time available. The most reli- ing an invented spelling that can help

tasks that require onset and rime analysis able and informative method of assessing determine if additional assessment is war-

require the segmentation of syllables, they phonological awareness is through, indi- ranted. In this and other similar scoring

are more sophisticated than syllable-level vidual testing. Other methods have been methods, points are awarded on the basis

tasks. Yet these same tasks are easier than developed, however, that are quick and of a spelling’s phonological accuracy. For

phoneme-level tasks because they do not easy to administer and that have reliability example, in an attempt to spell an unfa-

require discrimination between individual adequate for most classroom purposes. miliar word, a child may produce a scrib-

phonemes. Onset-rime tasks could, there-

fore, be considered an intermediate step in

the development of phonological aware-

ness. The difficulty that many children

experience when progressing from syllab-

ic analysis to phonemic analysis may arise

because the intermediate step, the intra-

syllabic unit, is often omitted from early

reading instruction. Providing experience

working with onsets and rimes may alle-

viate this difficulty.

Phoneme level. The most sophisticated

level of phonological awareness is the

phoneme level, most commonly referred to

as phonemic awareness. Children with

strong phonemic awareness are able to

manipulate individual phonemes, the

smallest sound units of spoken language.

Phonemic awareness skills include the abil-

ity to detect, segment, and blend phonemes

and to manipulate their position in words

(Adams, 1990; Lenchner et al., 1990).

Because humans coarticulate or overlap

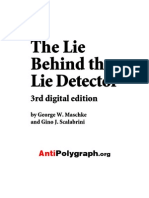

sounds in speech, phonemes are impossi- FIGURE 2 These example spellings for the word pretend begin with a series of scrib-

ble to segment in a pure sense. In the bles and move to a spelling that is phonologically accurate.

speech flow, phonemes are formed and

Vol. 46, No. 3 PREVENTING SCHOOL FAILURE 103

may be individualized, small-group, or

TABLE 1

Method for Scoring Invented Spelling

whole-class. For students who have signif-

icant weaknesses in phonological aware-

ness, 10–20 minutes of individual or

Characteristics of spelling Example spellings Score

small-group instruction each day may be

necessary to promote adequate growth. Of

One phoneme accurately represented other than t 1/2

initial phoneme course, student needs should dictate the

form and amount of instruction provided.

Initial phoneme accurately represented f 1

fesry Commerically Available Instructional

Initial phoneme and one other phoneme accurately ft 2 Programs

represented

As educators have become aware of the

Initial phoneme and two or more other phonemes fot 3

accurately represented flt

research on phonological awareness, pub-

lishers have recognized the demand for

Word is phonologically accurate flot 4 classroom materials. Numerous commer-

flote

cial programs are currently available.

Several of these programs have under-

gone field testing and evaluation. We pro-

ble, a random letter string, one or two cor- tion and production, sound matching, vide a list and brief description of

rectly represented phonemes, or even a phonemic oddity detection, deletion, research-based materials for teachers in

phonologically accurate spelling (Figure segmentation, and blending. Sample Table 4. In addition to these classroom

2). Each of these attempts represents sig- questions for informal assessment of a materials, several programs for computer-

nificant information about that child’s child’s phonological awareness appear assisted instruction have become avail-

phonological knowledge. See Table 1 for in Table 2. Several formal measures of able. A listing of these software programs

a summary of one method for scoring phonological awareness have been is provided in Table 5.

invented spellings. developed, as well. Descriptions of

The Screening Test of Phonological some of the most widely used appear in Informal Methods of Instruction

Awareness (STOPA) has been demon- Table 3. Most activities in commercial pro-

strated to be an effective group assess- grams such as those described can be

ment tool (Torgesen, Wagner, Bryant, & Developing Phonological Awareness

incorporated informally within existing

Pearson, 1992). The STOPA, designed for Just as assessing phonological aware- reading instruction. The following tasks

use with kindergarten students, requires ness is best accomplished by observing are useful for practicing and developing

students to identify sounds that are the students as they perform tasks that phonological skills. The tasks are

same and different. The test is simple to demonstrate phonological skills, devel- sequenced in an order that approximates

administer in a group setting, yet sophis- oping phonological awareness requires the developmental sequence. However,

ticated enough to detect individual differ- practicing phonological skills. Most skill the sequence and rate of skill develop-

ences in phonological awareness. instruction can be easily embedded ment vary from child to child, and skills

within the context of meaningful reading overlap during development. We also

Individualized Assessment or writing (Wadlington, 2000; Yopp, wish to stress that these activities are

To collect the kind of information 1992). Some children, however, require auditory and interactive in nature; chil-

about a child’s phonological knowledge more extensive practice with skills. Stu- dren do not develop phonological skills

that is necessary to design effective dents who have very low levels of read- by doing independent written work.

instructional interventions, individual ing ability benefit most from explicit

assessments are particularly useful. The instruction in phonological skills paired Tapping words. Children can be taught to

assessment method can be informal, cri- with explicit instruction in how to apply tap with a rhythm stick or finger for each

terion-referenced, or norm-referenced. those skills in a meaningful context word in a sentence or phrase. Most chil-

Clearly, the most direct informal (Cunningham, 1990; Lane, 1994). As dren acquire this skill with minimal

method of measuring a child’s phonolog- these children develop sensitivity to the instruction. Teacher modeling and guid-

ical awareness is repeated observation by sound structure of language, instruction ance are useful for those children who

a knowledgeable teacher of the child’s in phoneme segmentation and blending have difficulty with this task. Children

ability to perform tasks that require the should be coupled with instruction using who struggle with this activity typically

use of phonological skills. Such observa- letters (Pullen, 2000). confuse words and syllables. Care should

tion provides a teacher with an authentic Instruction in phonological skills can be taken to make this distinction explicit.

measure of what a child can or cannot do be conducted as formal, structured Counting and tallying words. Tallying the

(Valencia, 1997). A variety of skill areas lessons, as an integrated part of ongoing number of words in a sentence requires a

may be examined to measure phonologi- reading instruction, or as fun activities greater degree of cognitive engagement

cal awareness; these include rhyme detec- throughout the school day. Instruction than tapping words and is considered a

104 PREVENTING SCHOOL FAILURE Spring 2002

more sophisticated task. Another method ual syllables can begin in kindergarten. explicit instruction about what a rhyme is

of word counting involves moving a This process can be made into a game in (i.e., words rhyme when they sound the

marker to indicate the number of words in which children separate their names or the same in the middle and at the end). This

a sentence. names of familiar objects into syllables. instruction should be accompanied by

Instruction may begin with segmentation numerous examples and nonexamples of

Tapping syllables. Children may be of compound words (e.g., football, out- rhymes. Rhyme recognition simply

taught to tap out the number of syllables side, sidewalk). Children may also be requires the student to indicate whether or

in a word. This task requires auditory taught to count the number of syllables in not a pair of spoken words rhymes.

attention. The teacher should provide other long but familiar words. These tasks Instead of simply providing a pair of

extensive modeling and guided practice require auditory attention and memory. words, to promote rhyme recognition, the

to help children understand the concept of teacher might say, “Cat and sat both have

syllable. Starting with long but familiar Rhyme recognition. Children can be

an at. Does hat have an at?”

multisyllable words (e.g., refrigerator, taught to determine if two one-syllable

motorcycle) makes the acquisition of this words rhyme. Some children have an Rhyme generation. Generating a word or

skill easy for most children. inherent understanding of rhymes based list of words that rhyme with a given word

on extensive experiences with language is more difficult than determining if two

Segmenting syllables. Teaching students to and print. Other children who have not given words rhyme. The additional cog-

segment multisyllable words into individ- developed this understanding may need nitive and language requirements of

TABLE 2

Sample Assessment Questions

Assessment Directions Sample

Word level

Tapping words Teacher reads sentence aloud. Child taps for each word The little frog is jumping.

in the sentence.

Deleting words Teacher reads a compound word, the child deletes one word. Teacher says, “Say cowboy.” Child

repeats. “Now say cowboy, with-

out saying cow.”

Syllable level

Blending syllables Teacher reads word one syllable at a time. The child listens, What word do these sounds make?

then blends the sounds together to make the whole word. tea-cher.

Tapping syllables Teacher reads word aloud. Child taps for each syllable in the alligator

word.

Deleting syllables Teacher reads child a multisyllable word and the child deletes Teacher says, “Say wonder.” Child

a specific syllable. repeats. “Now say wonder with-

out saying der.

Onset-rime level

Matching rhymes Teacher gives child a word pair, the child decides whether Do these two words rhyme?

or not the pair rhymes. sack/black

Do these two words rhyme?

beat/bean

Blending onsets and rimes The teacher segments the word orally between the onset and What word do these sounds make?

rime. The child listens, then blends the sounds together n-ote.

to make the whole word.

Generating rhymes The teacher gives child a target word and the child must Tell me a word that rhymes with sat.

provide a word that rhymes with the target word.

Phoneme level

Blending phonemes Teacher segments a word into phonemes and the child is What word do these sounds make?

asked to blend the sounds to make the whole word. b-o-th.

Segmenting phonemes Teacher reads child a whole word and the child is asked to I will say a word, then you say it

produce the word sound-by-sound. sound by sound. mat.

Vol. 46, No. 3 PREVENTING SCHOOL FAILURE 105

rhyme generation make it quite challeng- begin or end with that sound. This activi- from a given word. For example, the

ing for some children. The ability to gen- ty can be used during story or passage teacher may ask, “Which of these words

erate rhymes, however, is an excellent reading, as well. While reading connect- does not have the same ending sound as

indicator of a child’s ability to apply ed text, students find all words in the cat: mutt, lift, cake, or bite?” Again, work

phonological knowledge. Many children selection that include the target phoneme. with medial sounds should start when stu-

engage in spontaneous word games that As students become comfortable with dents become skilled with beginning and

employ rhyming skills. This fun way to beginning and ending sounds, activities ending sounds.

practice skills should be encouraged. that include detection of a target medial

Rhyme and sound matching using pic-

Using nonsense words in such games sound should be added.

tures. For these activities, children are

reinforces the child’s attention to sounds.

Sound matching. To match sounds, stu- asked to look at pictures and generate the

Rhyme oddity detection. This task dents must determine which in a selection sounds themselves by naming the word

requires children to indicate which in a of words begins or ends with the same the picture represents. Students match

list of three or four words does not rhyme sound as a given word. For example, the pictures illustrating words that share a

with the other words in the list. The famil- teacher may ask students, “Which word common rime or a common initial, medi-

iar song from the television show Sesame begins with the same sound as dog: can, al, or final phoneme. This activity is

Street does this well: “Which of these must, or dish? somewhat more advanced than activities

words is not like the others? Which of As students master this skill, the activ- that begin with the teacher generating the

these words just doesn’t belong?” ity should be modified to request ending sounds, because some students find it

Rhyme matching. Given a list of three or or middle sound-matching, and more more difficult to detect individual

four words, students indicate which one words may be added to the list. phonemes when they do not hear some-

from the list rhymes with a target word. one else say the word.

Sound oddity detection. The procedures

For example, the teacher might say, for this activity are very similar to those Oddity detection using pictures. As in

“Which word rhymes with stamp: map, for rhyme oddity detection. The differ- the previous activity, the student is

lip, or lamp?” ence, however, is that students are asked expected to generate the name of the

Sound detection. Given a target phoneme, to determine which in a list of words word the pictures represents. The student

students determine which words on a list begins or ends with a sound different then determines which in a set of pic-

TABLE 3

Assessments of Phonological Awareness

Assessment Author/publisher Description

Lindamood Auditory Lindamood and Lindamood/ The LAC is a comprehensive, individually administered

Conceptualization Test Pro-Ed assessment for both children and adults. It is effective for a

(LAC) wide range of ages, however, it is difficult for very young

children (kindergarten).

Comprehensive Test of Wagner, Toregesen and The CTOPP is an individually-administered assessment that

Phonological Processing Rashotte/Pro-Ed measures (a) phonological awareness (e.g., sound matching,

(CTOPP) blending, elision); (b) phonological memory (memory of dig-

its, nonword repetition); and (c) rapid serial naming (rapid

naming of objects, numbers, and letters).

Test of Phonological Toregesen and Bryant/ TOPA is a measure of young children’s ability to isolate indi-

Awareness (TOPA) Pro-Ed vidual phonemes in spoken words. It can be administered to

groups of children and is available in Kindergarten and Early

Elementary versions.

Phonological Awareness Invernizzi, Meier, Swank PALS measures the child’s rhyming abilities and sound aware-

Literacy Screening and Juel/University of ness. In addition to these phonological skills, alphabet knowl-

(PALS) Virginia edge, letter sound knowledge, concept of word, and word

recognition are also assessed.

The Developmental Spelling Ganske/Guilford Press This assessment includes a screening inventory for determining

Analysis in Word Journey a child’s stage of spelling development and two parallel feature

inventories for high lighting strengths and weaknesses in a

child’s knowledge of specific spelling features.

106 PREVENTING SCHOOL FAILURE Spring 2002

tures illustrating words does not share a the skill orally. The teacher demonstrates Blending and segmenting. Blending and

common rime or a common initial, using fingers to count phonemes, raising segmenting phonemes are the most sophis-

medial, or final phoneme. one finger as each phoneme is pro- ticated skills associated with phonological

Counting phonemes. Elkonin (1963) nounced. With teacher guidance, the stu- awareness and the most important for

introduced a method of developing dent should be able to learn how to count application to decoding. Blending and seg-

phonemic segmentation skills that has phonemes independently. menting may be taught in a variety of

become quite popular in recent years. Phoneme deletion. Phoneme deletion ways. One of the most useful methods for

This method involves the use of Elkonin activities require students to detect and helping young children to understand the

boxes—picture cards with boxes under manipulate sounds in a word. Students concepts of phonemic blending and seg-

each picture representing the number of are asked to delete a specified sound from mentation is teaching them to “converse”

phonemes in the word (see Figure 3). a target word. For example, the teacher with a puppet or toy robot in a secret lan-

While saying the word slowly, sound by may say, “Say seat. Now say seat without guage. Torgesen and Bryant (1994) used

sound, the student moves a marker into saying the /t/ sound.” Again, practice with this approach in Phonological Awareness

each box to represent each sound in the this activity should begin with initial Training for Reading, but the method is

word. This activity may be modified to sounds and progress to final and, eventu- easy to adapt to informal instruction. In

allow the teacher and student to practice ally, medial sounds. this approach, the puppet or robot can only

TABLE 4

Commercially Available Instructional Programs

Program Author/publisher Description

Lindamood Phoneme Lindamood/ProEd LiPS is designed to provide intensive remedial instruction for

Sequencing Program students struggling to develop phonological awareness.

for Reading, Spelling, Sounds are represented with objects and descriptive names to

and Speech (LiPS) develop students’ concrete understanding of distinct sounds

by drawing a child’s attention to the motoric features of

phoneme articulation through individual or small group

instruction. Students learn how to position their mouths to

produce sounds and how to distinguish among various types

of sounds.

Road to the Code: A Program Blachman, Ball, Black, and Road to the Code includes activities to move students from

of Early Literacy Activities Tangel/Brookes phonological awareness to letter knowledge. The program

to Develop Phonological gradually moves into activities that encourage the application

Awareness of these skills in writing and spelling.

Phonological Awareness Torgesen and Bryant/ProEd This program includes games and activities to help children

Training for Reading develop sound segmenting and blending, reading and

spelling. An audiotape guide for sound pronunciation is

included.

Phonemic Awareness in Adams, Foorman, Lundberg, This curriculum provides a basis for assessment and instruc-

Young Children and Beeler/Brookes tion in phonological awareness. The book includes a variety

of language games, listening games, rhyming activities, and

activities for developing students’ understanding of sounds in

words. Several instruments for assessing phonological aware-

ness are also included.

Ladders to Literacy O’Connor, Notari-Syverson, These preschool and kindergarten activity books provide

and Vadasy/Brookes early literacy activities in phonological awareness, vocabulary

development, and letter names and sounds. The program is

designed to emphasize the provision of appropriate levels of

instructional support for developing students.

Sounds Abound Catts and Vartiainen/ Sounds Abound is for children in grades PreK–3. It targets

LinguiSystems listening and rhyming skills as students work toward match-

ing sounds with letters. Five sections include fun activities in

(1) speech sound awareness, (2) rhyming, (3) beginning and

ending sounds, (4) segmenting and blending sounds, and (5)

putting sounds together with words.

Vol. 46, No. 3 PREVENTING SCHOOL FAILURE 107

say words and can only understand words should be very careful to model correct this strategy may help them blend stop

when they are said one sound at a time. letter sound pronunciation. Many teach- consonants more readily.

Young children seem to accept and under- ers, in an effort to make short or “stop” Another way to alleviate this problem

stand this explanation quite readily and are consonant sounds more audible, add a is to begin instruction in blending and

eager to try communicating in this unusu- vowel sound to the consonant. This addi- segmenting using only words with con-

al fashion. tional sound, usually a schwa or short u tinuous consonant sounds (e.g., /s/, /v/,

When teaching or assessing blending sound, distorts the consonant sound, mak- /z/, /f/, /m/, /n/) at the beginning posi-

and segmentation skills, the teacher ing it very difficult to blend with other tion. These sounds are much easier to

should be careful to completely segment phonemes. For example, a b may be blend than the stop consonants, and their

phonemes before blending them. Many incorrectly pronounced “buh,” and a t use in early instruction makes the skill of

teachers have the tendency simply to say may be incorrectly pronounced “tuh.” blending more accessible for children.

a word slowly, drawing out the Blending the letters b, a, and t then pro- As children are introduced to blending

phonemes. The teacher should be certain duces “buh-a-tuh,” and many children skills, stop consonants may be used at

to include a brief but discernible pause have serious difficulty identifying the the end of words. In the final position,

between segmented sounds. When chil- word. It is important to pronounce these stop consonants are easier to pronounce

dren learn to decode, it is necessary for stop consonants as quickly as possible, quickly and with little distortion. When

them to identify the sounds of separate without the confusing “uh.” Because it is students become competent with pro-

letters and then to blend those letter impossible to pronounce a voiced stop nunciation, the introduction of stops at

sounds together. Previous oral blending consonant such as b or d in isolation with the initial position becomes less trouble-

practice is helpful for students when they no vowel sound attached, the teacher some.

are ready to become more fluent with should model saying the sound with an

Including Phonological Awareness

decoding skills. extremely brief short i sound following it.

Instruction in an Existing Reading

Another important caution for teachers The place in the vocal anatomy where the

Program

is that individual phonemes must be pro- short i is produced is closer to the loca-

nounced in a manner that will make them tion of more of the other vowel sounds Many of the activities we have

blendable. In other words, teachers than the short u. Teaching children to use described can be integrated into any read-

TABLE 5

Instructional Software Programs

Program Author/publisher Description

Earobics Wasowicz/Cognitive Concepts Earobics is a software program designed to develop phonemic

awareness and letter-sound knowledge through engaging

games.

Daisy Quest and Daisy’s Erikson, Foster, Foster, and Daisy Quest and Daisy’s Castle are computer programs for the

Castle Torgesen/ProEd Macintosh. The games are motivating for children while pro-

viding opportunities to develop phonological awareness at each

level. Research studies have found these software programs to

be an effective way to stimulate phonological awareness in

young children.

The Waterford Early The Waterford Institute/ The Waterford Early Reading Program is a comprehensive

Reading Program Electronic Education computer program for Kindergarten. It provides activities in

phonological awareness, concepts of print, letter names, and

letter sounds.

Read, Write, and Type! Herron and Grimm/ This computer software program merges the teaching of phon-

Learning System Talking Fingers ics skills with an introduction to typing. Children move

through a progressively challenging sequence games that

begins with single letters, advances to whole words, and con-

cludes with complete sentences, including capitalization and

punctuation.

Fast ForWord Merzenich, Tallal, Jenkins, Fast ForWord is an interactive program that stimulates child-

and Miller/Scientific ren’s phonological skills using acoustically modified speech

Learning sounds. This acoustic training is provided in five 20-minute

sessions each day. Requires teacher training.

108 PREVENTING SCHOOL FAILURE Spring 2002

at the end”). Teachers can challenge stu- REFERENCES

dents to think of words that have a partic- Adams, M. J. (1990). Beginning to read: Thinking

ular number of syllables or phonemes. and learning about print. Cambridge: MIT.

Adams, M. J., Foorman, B. R., Lundberg, I., & Beel-

Finding many fun and innovative ways to er, T. (1998). Phonemic awareness in young chil-

include such sound play in the school day dren: A classroom curriculum. Baltimore, MD:

will address the instructional needs of Brookes.

Anderson, R. C., Hiebert, E. H., Scott, J. A., &

many students. Additional practice in Wilkinson, I. A. (1985). Becoming a nation of

specific skills will certainly be required readers: The report of the commission on read-

for some students who have difficulty ing. Washington, DC: National Institute of Edu-

cation.

acquiring phonological skills, but such Blachman, B. A. (1991). Early interventions for

informal opportunities to practice children’s reading problems: Clinical applica-

throughout the day will help these stu- tions of the research in phonological awareness.

Topics in Language Disorders, 12(1), 51–65.

dents, as well. Blachman, B. A., Ball, E. W., Black, R., & Tangel,

Combining informal sound play and D. M. (2000). Road to the code: A phonological

formal phonological awareness instruc- awareness program for young children. Balti-

more, MD: Brookes.

tion during typical reading and writing Blachman, B. A., Tangel, D. M., Ball, E. W., Black,

activities for all students with explicit R., & McGraw, C. K. (1999). Developing phono-

skill instruction for students who need logical awareness and word recognition skills: A

two-year intervention with low-income, inner-

additional practice should address the city children. Reading and Writing: An Interdis-

diverse needs in most elementary class- ciplinary Journal, 11, 239–273.

FIGURE 3. The teacher models Bradley, L. (1988). Rhyme recognition and reading

moving one chip into a square for

rooms. The most important thing for

and spelling in young children. In R. L. Masland

each sound in fish. The student then teachers to do is to make the sound struc- & M. W. Masland (Eds.), Preschool prevention of

moves the chips into the squares with ture of language conspicuous to students reading failure (pp. 143-162). Parkton, MD:

help from the teacher, until the stu- who do not develop phonological aware- York.

dent is able to move the chips into the Catts, H. W. (1991). Early identification of reading

ness independently. disabilities. Topics in Language Disorders, 12(1),

squares independently. Eventually,

the student learns to write letters in

The activities presented here are 1–16.

designed to develop phonological aware- Chard, D. J., & Dickson, S. V. (1999). Phonological

the boxes. awareness: Instructional and assessment guide-

ness. Applying these auditory skills to lines. Intervention in School and Clinic, 34, 261-

reading requires students to have a work- 270.

ing knowledge of sound-symbol relation- Cornwall, A. (1992). The relationship of phonolog-

ical awareness, rapid naming, and verbal memo-

ing activity or used as games during ships, which is typically acquired through ry to severe reading and spelling disability. Jour-

instruction or during noninstructional phonics instruction. Despite popular mis- nal of Learning Disabilities, 25, 532–538.

time. For example, singing and play conceptions, phonological awareness Cunningham, A. E. (1990). Explicit versus implicit

instruction in phonemic awareness. Journal of

activities offer many opportunities for instruction is not the same as phonics Experimental Child Psychology, 50, 429–444.

kindergarten teachers to incorporate instruction; instead, phonological aware- Elkonin, D. B. (1963). The psychology of mastering

phonological skill development. Stories ness instruction prepares students to be the elements of reading. In B. Simon & J. Simon

(Eds.), Educational psychology in the U.S.S.R. (pp.

or poems that include rhyming words able to benefit from instruction in phonics. 165–179). Stanford, CA: Stanford University.

may be used as a tool to introduce and Erikson, G. C., Foster, K. C., Foster, D. F. & Torge-

develop concepts and skills in rhyming. A Conclusion sen, J. K. (1992). Daisy Quest. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed.

Erikson, G. C., Foster, K. C., Foster, D. F. & Torge-

teacher of older students could ask them Reading research has clearly demon- sen, J. K. (1993). Daisy’s Castle. Austin, TX:

to count the number of syllables or strated the significance of phonological Pro-Ed.

phonemes in the names of story charac- awareness in the development of early Ganske, K. (2000). Word journeys: Assessment-

guided phonics, spelling, and vocabulary instruc-

ters or in new vocabulary words. If a reading skills, and a variety of effective tion. New York: Guildford.

teacher encourages the use of carefully methods for assessment and instruction of Goswami, U., & Mead, F. (1992). Onset and rime

invented spellings, students learn to seg- phonological skills has been developed. awareness and analogies in reading. Reading

ment words and represent the correct Research Quarterly, 27, 152–162.

Teachers in remedial and special educa- Herron, J., & Grimm, L. (2001). Read, Write, &

number of phonemes. Modeling how to tion programs now have another tool for Type! Learning System. San Raphael, CA: Talk-

sound out a word to invent a spelling can addressing students’ reading problems. ing Fingers.

help students develop these skills. As stu- Invernizzi, M., Meier, J. D., Swank, L., & Juel, C.

Teachers of young children must recog- (1998). Phonological awareness literacy screen-

dents learn about decoding, numerous nize the importance of incorporating ing. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia.

other opportunities for instruction in phonological awareness into programs Lane, H. B. (1994). The effects of explicit instruc-

blending and segmentation arise. designed to promote emergent literacy, tion in contextual application of phonological

awareness on the reading skills of first-grade stu-

The teacher could make a simple because these teachers now have a tool dents. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Univer-

whole-class game out of rhyme or for preventing reading problems. sity of Florida, Gainesville.

phoneme matching (e.g., “Line up for Lenchner, O., Gerber, M. M., & Routh, D. K.

Key words: phonological awareness, phone- (1990). Phonological awareness tasks as predic-

lunch if your name rhymes with mic awareness, phonics, beginning reading, tors of decoding ability: Beyond segmentation.

___________,” or “if your name has a /t/ early intervention Journal of Learning Disabilities, 23, 240-247.

Vol. 46, No. 3 PREVENTING SCHOOL FAILURE 109

Liberman, I. Y., Shankweiler, D., & Liberman, A. M. read: Basic research and its implications (pp. diation of phonologically based reading disabili-

(1989). The alphabetic principle and learning to 33–44). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Asso- ties. In B. Blachman (Ed.), Foundations of read-

read. In D. Shankweiler & I. Y. Liberman (Eds.), ciates. ing acquisition and dyslexia: Implications for

Phonology and reading disability: Solving the Perfetti, C. A., Beck, I., Bell, L. C., & Hughes, C. early intervention (pp. 287-304). Mahwah, NJ:

reading puzzle (pp. 1-33). Ann Arbor: The Uni- (1987). Phonemic knowledge and learning to read Erlbaum.

versity of Michigan Press. are reciprocal: A longitudinal study of first grade Torgesen, J. K., Wagner, R. K., Bryant, B. R., &

Liberman, I., & Shankweiler, D. (1985). Phonology children. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 33, 283–319. Pearson, N. (1992). Toward development of a

and the problems of learning to read and write. Pratt, A. C., & Brady, S. (1988). Relation of phono- kindergarten group test for phonological aware-

Remedial and Special Education, 6, 8–17. logical awareness to reading disability in children ness. Journal of Research and Development in

Lindamood, C., & Lindamood, P. (1972). Lin- and adults. Journal of Educational Psychology, Education, 25, 113–120.

damood auditory conceptualization test. Austin, 80, 319–323. Treiman, R. (1985). Onsets and rimes as units of

TX: Pro-Ed. Pullen, P. C. (2000). The effects of alphabetic word spoken syllables: Evidence from children. Jour-

Lindamood, C., & Lindamood, P. (1998). Lin- work with manipulative letters on the reading nal of Experimental Child Psychology, 39,

damood phoneme sequencing program for read- acquisition of struggling first-grade students. 161–181.

ing, spelling, and speech. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of Treiman, R. (1991). The role of intrasyllabic units

Lundberg, I. (1988). Preschool prevention of read- Florida, Gainesville. in learning to read. In L. Rieben & C. A. Perfetti

ing failure: Does training in phonological aware- Smith, C. R. (1995, March). Assessment and reme- (Eds.), Learning to read: Basic research and its

ness work? In R. L. Masland & M. W. Masland diation of phonological segmentation difficulties. implications (pp. 149–160). Hillsdale, NJ:

(Eds.), Preschool prevention of reading failure Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Lawrence Erlbaum.

(pp. 163–176). Parkton, MD: York. Learning Disabilities Association of America, Treiman, R. (1992). The role of intrasyllabic units

Lyon, G. R. (1999). Education research: Is what we Orlando, FL. in learning to read and spell. In P. B. Gough, L.

don’t know hurting our children? Statement of the Smith, S. B., Simmons, D. C., & Kame’enui, E. J. C. Ehri, & R. Treiman (Eds.), Reading acquisi-

Chief of the Child Development and Behavior (1995). Synthesis of research on phonological tion (pp. 65–106). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erl-

Branch of the National Institute of Child Health awareness: Principles and implications for read- baum.

and Human Development, National Institutes of ing acquisition. Technical Report No. 21, Nation- Valencia, S. W. (1997). Authentic classroom assess-

Health, to the House Science Committee. Wash- al Center to Improve the Tools of Educators, Uni- ment of early reading: Alternatives to standard-

ington, DC. versity of Oregon. ized tests. Preventing School Failure, 41, 63–70.

Mann, V. A., Tobin, P., & Wilson, R. (1987). Mea- Snow, C. E., Burns, M. S., & Griffin, P. (Eds.). Wadlington, E. (2000). Effective language arts

suring phonological awareness through the (1998). Preventing reading difficulties in young instruction for students with dyslexia. Preventing

invented spellings of kindergarten children. Mer- children. Washington, D C: National Academy. School Failure, 44, 61-65.

rill-Palmer Quarterly, 33, 365–391. Stanovich, K. E. (1986). Matthew effects in reading: Wagner, R. K., & Torgesen, J. K. (1987). The nature

Merzenich, M., Tallal, P., Jenkins, W., & Miller, S. Some consequences of individual differences in of phonological processing and its causal role in

(1996). Fast ForWord. Oakland, CA: Scientific the acquisition of literacy. Reading Research the acquisition of reading skills. Psychological

Learning. Quarterly, 21, 360–406. Bulletin, 101, 192–212.

Moats, L. (2000). Speech to print: Language essen- Stanovich, K. E. (1987). Introduction to special Wagner, R., Torgesen, J., & Rashotte, C. (1999).

tials for teachers. Baltimore, MD: Brookes. issue. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 33. Comprehensive test of phonological processing

National Reading Panel. (2000). Teaching children Stanovich, K. E. (1992). Speculations on the causes (CTOPP). Austin, TX: Pro-Ed.

to read: An evidence-based assessment of the sci- and consequences of individual differences in Wasowicz, J. (1997). Earobics 1. Evanston, IL:

entific research literature on reading and its early reading acquisition. In P. B. Gough, L. C. Cognitive Concepts.

implications for reading instruction. Washington, Ehri, & R. Treiman (Eds.), Reading acquisition Wasowicz, J. (1999). Earobics 2. Evanston, IL:

DC: National Institute of Child Health and (pp. 307–342). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Cognitive Concepts.

Human Development, National Institutes of Torgesen, J. K. (1998). Catch them before they fall: Waterford Institute. (1993). Waterford early learn-

Health. Identification and assessment to prevent reading ing program. Sunnyvale, CA: Electronic Educa-

Notari-Syverson, A., O’Connor, R. E., & Vadasy, P. failure in young children. American Educator, 22, tion.

F. (1998). Ladders to Literacy: A Preschool Activ- 32–39. Yopp, H. K. (1988). The validity and reliability of

ity Book. Baltimore, MD: Brookes. Torgesen, J. K., & Bryant, B. R. (1994). Phonolog- phonemic awareness tests. Reading Research

O’Connor, R. E., Notari-Syverson, A., & Vadasy, P. ical awareness training for reading. Austin, TX: Quarterly, 23, 159–177.

F. (1998). Ladders to Literacy: A Kindergarten Pro-ed. Yopp, H. K. (1992). Developing phonemic aware-

Activity Book. Baltimore, MD: Brookes. Torgesen, J. K., & Bryant, B. R. (1997). Test of ness in young children. The Reading Teacher, 45,

Perfetti, C. A. (1991). Representations and aware- phonological awareness. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed. 696–703.

ness in the acquisition of reading competence. In Torgesen, J. K., Wagner, R. K., & Rashotte, C. A.

L. Rieben & C. A. Perfetti (Eds.), Learning to (1997). Approaches to the prevention and reme-

110 PREVENTING SCHOOL FAILURE Spring 2002

View publication stats

You might also like

- Phonological AwarenessDocument11 pagesPhonological AwarenessJoy Lumamba TabiosNo ratings yet

- Developing Language and Literacy: Effective Intervention in the Early YearsFrom EverandDeveloping Language and Literacy: Effective Intervention in the Early YearsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Phonemic Awareness and PhonicsDocument4 pagesPhonemic Awareness and PhonicsNesya EskenaziNo ratings yet

- Phonemic Awareness and Phonics: Author MonographsDocument4 pagesPhonemic Awareness and Phonics: Author MonographsEryNo ratings yet

- Phonics Resource KitDocument23 pagesPhonics Resource KitLina AliNo ratings yet

- Listening Skill For InclusiveDocument7 pagesListening Skill For Inclusivelim07-148No ratings yet

- ResearchDocument13 pagesResearchAnneNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Science in Literacy Education: Today'S Climate and Tomorrow'S HopeDocument28 pagesRunning Head: Science in Literacy Education: Today'S Climate and Tomorrow'S HopercjamckNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Syllable Instruction On Phonemic Awareness in PreschoolersDocument11 pagesThe Effects of Syllable Instruction On Phonemic Awareness in Preschoolerslifiana khofifahNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Prior Knowledge PDFDocument10 pagesThe Relationship Between Prior Knowledge PDFThê Hîrumzz HëllNo ratings yet

- Effective Word Reading Instruction What Does The Evidence Tell UsDocument9 pagesEffective Word Reading Instruction What Does The Evidence Tell UsDaniel AlanNo ratings yet

- "Find Me Now, Say Me Later": A Play-Based Approach in Teaching Phonemic Awareness To Grade One Pupils of Kinagunan Elementary SchoolDocument9 pages"Find Me Now, Say Me Later": A Play-Based Approach in Teaching Phonemic Awareness To Grade One Pupils of Kinagunan Elementary SchoolPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- Phonemic Awareness On Consonant Sounds FinalDocument30 pagesPhonemic Awareness On Consonant Sounds FinalMikkaella RimandoNo ratings yet

- Dynamic Assessment of Phonological Awareness For Children With Speech Sound DisordersDocument11 pagesDynamic Assessment of Phonological Awareness For Children With Speech Sound DisordersRodrigo TarbesNo ratings yet

- 1-1 PDFDocument25 pages1-1 PDFOrunsolu TemitolaNo ratings yet

- ArticolDocument12 pagesArticolEunice LuncanNo ratings yet

- Alrj 3 3 41 50Document10 pagesAlrj 3 3 41 50asad modawiNo ratings yet

- Oficial-Proposal-Action ResearchDocument3 pagesOficial-Proposal-Action ResearchRoyce DivineNo ratings yet

- Directed Learning Experience Final 11-1Document16 pagesDirected Learning Experience Final 11-1api-463538537No ratings yet

- Successfold CFDocument16 pagesSuccessfold CFRamon SanhuezaNo ratings yet

- Muñoz, Valenzuela, OrellanaDocument12 pagesMuñoz, Valenzuela, OrellanakattiamunoznaviaNo ratings yet

- Phonological Awareness and Bilingual Preschoolers: Should We Teach It And, If So, How?Document7 pagesPhonological Awareness and Bilingual Preschoolers: Should We Teach It And, If So, How?Diana DiazNo ratings yet

- Phonemic Awareness and The Teaching of ReadingDocument10 pagesPhonemic Awareness and The Teaching of ReadingDavid Woo100% (2)

- Knowledge 7Document20 pagesKnowledge 7Jake Arman PrincipeNo ratings yet

- Catch-Up-Fridays-February 2, 2024Document18 pagesCatch-Up-Fridays-February 2, 2024DAHLIA BACHONo ratings yet

- Development of Phonological Awareness. Jason Anthony David Francis. With Cover Page v2Document7 pagesDevelopment of Phonological Awareness. Jason Anthony David Francis. With Cover Page v2BorostyánLéhnerNo ratings yet

- CognitionDocument9 pagesCognitionMarilyn BucahchanNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 78.131.36.94 On Wed, 24 Nov 2021 12:31:14 UTCDocument6 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 78.131.36.94 On Wed, 24 Nov 2021 12:31:14 UTCBorostyánLéhnerNo ratings yet

- Sound Systems - Explicit, Systematic Phonics in Early Literacy Contexts (PDFDrive)Document176 pagesSound Systems - Explicit, Systematic Phonics in Early Literacy Contexts (PDFDrive)Claudia Patricia FernándezNo ratings yet

- Listening DiaryDocument19 pagesListening DiaryIryna BilianskaNo ratings yet

- Gillon 2005Document5 pagesGillon 2005RobertaXDNo ratings yet

- Using English Songs To Improve Young Learners' Listening ComprehensionDocument11 pagesUsing English Songs To Improve Young Learners' Listening ComprehensionIJELS Research JournalNo ratings yet

- The Use of Song Lyrics in Teaching Listening (A Case Study of Junior High School Grade 8 in Bandung)Document10 pagesThe Use of Song Lyrics in Teaching Listening (A Case Study of Junior High School Grade 8 in Bandung)Muhamad UmamNo ratings yet

- Phonemic Awareness and Phonics BrochureDocument2 pagesPhonemic Awareness and Phonics Brochureapi-525672352No ratings yet

- WPH001 - IsmaelDocument14 pagesWPH001 - Ismaelkristine camachoNo ratings yet

- 2017 Effective Reading Instruction in The Early Years of SchoolDocument18 pages2017 Effective Reading Instruction in The Early Years of SchoolVanessa MadukaNo ratings yet

- Children Learning To Read Later Catch Up To Children Reading Earlier PDFDocument16 pagesChildren Learning To Read Later Catch Up To Children Reading Earlier PDFotiliaglamNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Phonics To The Reading Readiness Thesis SeminarDocument16 pagesThe Effects of Phonics To The Reading Readiness Thesis Seminarerika garcelisNo ratings yet

- Reading Achievement in Relation To Phonological Coding and Awareness in Deaf Readers: A Meta-AnalysisDocument25 pagesReading Achievement in Relation To Phonological Coding and Awareness in Deaf Readers: A Meta-AnalysisNino LomadzeNo ratings yet

- Julia Mershon TLP HandoutDocument5 pagesJulia Mershon TLP Handoutapi-529096611No ratings yet

- Como Facilitar El AprendizajeDocument14 pagesComo Facilitar El AprendizajeMarjorie TovarNo ratings yet

- Campbell - Feeling The Pressure - 2015Document16 pagesCampbell - Feeling The Pressure - 2015MariaNo ratings yet

- How To Promote Reading ComprehensionDocument9 pagesHow To Promote Reading ComprehensionJack EckhartNo ratings yet

- Nursery Rhymes and Language Learning: Issues and Pedagogical ImplicationsDocument6 pagesNursery Rhymes and Language Learning: Issues and Pedagogical ImplicationsIJ-ELTSNo ratings yet

- Nursery Rhymes 1 PDFDocument6 pagesNursery Rhymes 1 PDFMaria Theresa AlcantaraNo ratings yet

- Kindergarten Letter Knowledge, Phonological Skills, and Memory Processes: Relative Effects On Early LiteracyDocument30 pagesKindergarten Letter Knowledge, Phonological Skills, and Memory Processes: Relative Effects On Early LiteracySara XocotlNo ratings yet

- MorrisDevelopmental PDFDocument27 pagesMorrisDevelopmental PDFJeffery McDonaldNo ratings yet

- Emergent Reading ProgramDocument14 pagesEmergent Reading ProgramSangie CenetaNo ratings yet

- Bus I Van IJzendoorn 1999 MetaanalizaDocument12 pagesBus I Van IJzendoorn 1999 MetaanalizaRobertaXDNo ratings yet

- TASK 1: Research Matrix Based On Empirical Literature and Personal LearningDocument17 pagesTASK 1: Research Matrix Based On Empirical Literature and Personal Learningkristine camachoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE ADocument31 pagesChapter 2 REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE AAlexandra HiromiNo ratings yet

- Conciencia Fonologica 3 MuñozDocument18 pagesConciencia Fonologica 3 MuñozkattiaNo ratings yet

- Phonological and Phonemic AwarenessDocument11 pagesPhonological and Phonemic AwarenessMay Anne AlmarioNo ratings yet

- The Big Six Components of Reading PDFDocument5 pagesThe Big Six Components of Reading PDFJaphet Raymundo Garcia50% (2)

- The Relationship Between Music and Reading in Beginning ReadersDocument10 pagesThe Relationship Between Music and Reading in Beginning ReadersNuzul AliNo ratings yet

- Placing Music at The Centre of Literacy InstructionDocument4 pagesPlacing Music at The Centre of Literacy InstructionKandiceNo ratings yet

- Phonics and Word Recognition Instruction in Early Reading Programs: Guidelines For AccessibilityDocument17 pagesPhonics and Word Recognition Instruction in Early Reading Programs: Guidelines For AccessibilityAlicia Pagbilao BacaniNo ratings yet

- Phonemic AwarenessDocument12 pagesPhonemic Awarenessapi-249409482No ratings yet

- Feduc 06 750328Document7 pagesFeduc 06 750328Babol GilbertNo ratings yet

- GST Step4Document113 pagesGST Step4Angela WeaslyNo ratings yet

- Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine: SciencedirectDocument16 pagesComputer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine: SciencedirectAngela WeaslyNo ratings yet

- The Home Literacy Environment and Preschool Children's Reading Skills and InterestDocument26 pagesThe Home Literacy Environment and Preschool Children's Reading Skills and InterestAngela WeaslyNo ratings yet

- Abecedario Animales Formato Tarjetas PDFDocument14 pagesAbecedario Animales Formato Tarjetas PDFAngela WeaslyNo ratings yet

- Introduction To MicrobesDocument10 pagesIntroduction To MicrobesAngela WeaslyNo ratings yet

- Methods For Evaluating Mobile Learning: January 2009Document15 pagesMethods For Evaluating Mobile Learning: January 2009Angela WeaslyNo ratings yet

- Impact of The Home Learning Environment On Child Cognitive Development: Secondary Analysis of Data From 'Growing Up in Scotland'Document41 pagesImpact of The Home Learning Environment On Child Cognitive Development: Secondary Analysis of Data From 'Growing Up in Scotland'Angela WeaslyNo ratings yet

- Computers in Human Behavior: Full Length ArticleDocument9 pagesComputers in Human Behavior: Full Length ArticleAngela WeaslyNo ratings yet

- Early Childhood Education & Care & Long-Term Effects: Edward MelhuishDocument27 pagesEarly Childhood Education & Care & Long-Term Effects: Edward MelhuishAngela WeaslyNo ratings yet

- DFE RR142a PDFDocument80 pagesDFE RR142a PDFAngela WeaslyNo ratings yet

- 03 ZARANIS CONF 57zaEDULERN828Document11 pages03 ZARANIS CONF 57zaEDULERN828Angela WeaslyNo ratings yet

- 10 1 1 607 4118 PDFDocument21 pages10 1 1 607 4118 PDFAngela WeaslyNo ratings yet

- Childrens Early Home Learning Environment and Learning Outcomes in The Early Years of SchoolDocument19 pagesChildrens Early Home Learning Environment and Learning Outcomes in The Early Years of SchoolAngela WeaslyNo ratings yet

- Interactive English Phonics Learning For Kindergarten Consonant-Vowel-Consonant (CVC) Word Using Augmented RealityDocument7 pagesInteractive English Phonics Learning For Kindergarten Consonant-Vowel-Consonant (CVC) Word Using Augmented RealityAngela WeaslyNo ratings yet

- Computers & Education: Mansureh Kebritchi, Atsusi Hirumi, Haiyan BaiDocument17 pagesComputers & Education: Mansureh Kebritchi, Atsusi Hirumi, Haiyan BaiAngela WeaslyNo ratings yet

- Computers in Human Behavior: Full Length ArticleDocument8 pagesComputers in Human Behavior: Full Length ArticleAngela WeaslyNo ratings yet

- Nios Accountancy Full BookDocument300 pagesNios Accountancy Full BookVivek Ratan100% (1)

- Lesson Plan Class 7th New Kings and KingdomsDocument2 pagesLesson Plan Class 7th New Kings and KingdomsPankhuri Agarwal60% (5)

- Total Gadha-Progression and TSDDocument6 pagesTotal Gadha-Progression and TSDSaket ShahiNo ratings yet

- Flight Instructor Training Aeroplane PDFDocument20 pagesFlight Instructor Training Aeroplane PDFMohamadreza TaheriNo ratings yet

- Final Outcomes Inventory HDF 492Document65 pagesFinal Outcomes Inventory HDF 492api-284496257No ratings yet

- Civil EngineerDocument1 pageCivil EngineerEdgar Henri NicolasNo ratings yet

- Thesis Synopsis NIFT BhopalDocument7 pagesThesis Synopsis NIFT BhopalsagrikakhandkaNo ratings yet

- MODULE 4 THE STRENGTH AND WEAKNESSES OF THE FILIPINO CHARACTER A SOCIO CULTURAL ISSUE Most RecentDocument10 pagesMODULE 4 THE STRENGTH AND WEAKNESSES OF THE FILIPINO CHARACTER A SOCIO CULTURAL ISSUE Most RecentJonel Razon74% (34)

- Best Practices in Public AdministrationDocument8 pagesBest Practices in Public AdministrationRicky BuloNo ratings yet

- Differentiated Lesson Plan 1: CCSS - Math.Content - HSG.SRT.C.6Document9 pagesDifferentiated Lesson Plan 1: CCSS - Math.Content - HSG.SRT.C.6api-373598912No ratings yet

- June 3, 2015Document16 pagesJune 3, 2015The Delphos HeraldNo ratings yet

- Unit 16 and First Half of Unit 17Document25 pagesUnit 16 and First Half of Unit 17toantran87No ratings yet

- Llengua Estrangera: AnglèsDocument16 pagesLlengua Estrangera: Anglèsavilella26No ratings yet

- 1 - Social Media Use Integration ScaleDocument13 pages1 - Social Media Use Integration ScaledavidrferrerNo ratings yet

- English 3-Q4-L8 ModuleDocument15 pagesEnglish 3-Q4-L8 ModuleZosima AbalosNo ratings yet

- Mock Test-Foundation-Of-EducationDocument3 pagesMock Test-Foundation-Of-EducationVinus RosarioNo ratings yet

- Parents With Mental Retardation and Their Children PDFDocument15 pagesParents With Mental Retardation and Their Children PDFNabila RizkikaNo ratings yet

- Events That Changed History (Description)Document5 pagesEvents That Changed History (Description)Pasat TincaNo ratings yet

- Lie Behind The Lie DetectorDocument216 pagesLie Behind The Lie DetectorAlin Constantin100% (1)

- Desert Based Muslim Religious Education Mahdara As A ModelDocument15 pagesDesert Based Muslim Religious Education Mahdara As A ModelJanuhu ZakaryNo ratings yet

- Mirrors and Windows - HuberKrieglerDocument110 pagesMirrors and Windows - HuberKrieglerJaime Gómez RomeroNo ratings yet

- Micro ControllerDocument7 pagesMicro ControllerYogesh MakwanaNo ratings yet

- Connotation and Denotation ExtensiveDocument4 pagesConnotation and Denotation Extensiveapi-395145532No ratings yet

- Applying Life Skills Ch.7Document30 pagesApplying Life Skills Ch.7linaNo ratings yet

- CS10-1L SyllabusDocument6 pagesCS10-1L SyllabusakladffjaNo ratings yet

- The Leadership ChallengeDocument12 pagesThe Leadership ChallengeJose Miguel100% (1)

- Ausubel's Meaningful Verbal LearningDocument28 pagesAusubel's Meaningful Verbal LearningNicole Recimo Mercado0% (1)

- Linking Words 1Document10 pagesLinking Words 1Yuliia KharytonovaNo ratings yet

- B.tech - Syllabus Oct 2016Document144 pagesB.tech - Syllabus Oct 2016Ravi RanjanNo ratings yet

- Position PaperDocument3 pagesPosition PaperCy PanganibanNo ratings yet