Professional Documents

Culture Documents

(TOPIC 1: Requisites of A Negotiable Instrument (Module 2) )

Uploaded by

atOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

(TOPIC 1: Requisites of A Negotiable Instrument (Module 2) )

Uploaded by

atCopyright:

Available Formats

NEGOTIABLE INSTRUMENTS AND INSOLVENCY LAW – 2H 2020-2021

CASE TITLE CALTEX v. CA G.R. NO. 97753

PONENTE Regalado, J DATE August 10, 1992

DOCTRINE [TOPIC 1: Requisites of a negotiable instrument (Module 2)]

Section 1 of Act No. 2031, otherwise known as the Negotiable Instruments Law, enumerates the requisites

for an instrument to become negotiable, viz: "(a) It must be in writing and signed by the maker or drawer;

(b) Must contain an unconditional promise or order to pay a sum certain in money; (c) Must be payable

on demand, or at a fixed or determinable future time; (d) Must be payable to order or to bearer; and (e)

Where the instrument is addressed to a drawee, he must be named or otherwise indicated therein with

reasonable certainty."

[TOPIC 2: Determination of negotiability or nonnegotiability of instrument (Module 2)]

The accepted rule is that the negotiability or nonnegotiability of an instrument is determined from the

writing, that is, from the face of the instrument itself. In the construction of a bill or note, the intention of

the parties is to control, if it can be legally ascertained. While the writing may be read in the light of

surrounding circumstances in order to more perfectly understand the intent and meaning of the parties,

yet as they have constituted the writing to be the only outward and visible expression of their meaning,

no other words are to be added to it or substituted in its stead. The duty of the court in such case is to

ascertain, not what the parties may have secretly intended as contradistinguished from what their words

express, but what is the meaning of the words they have used. What the parties meant must be

determined by what they said.

[TOPIC 3: Parties (Module 1)]

Delivery of instrument constitute the transferee a mere holder for value by reason of his lien. Under the

Negotiable Instruments Law, an instrument is negotiated when it is transferred from one person to another

in such a manner as to constitute the transferee the holder thereof, and a holder may be the payee or

indorsee of a bill or note, who is in possession of it, or the bearer thereof. The pertinent law on this point

is that where the holder has a lien on the instrument arising from contract, he is deemed a holder for value

to the extent of his lien.

FACTS § Security Bank and Trust Company (Security Bank), a commercial banking institution, through its Sucat

Branch issued 280 certificates of time deposit (CTDs) in favor of Angel dela Cruz who deposited with

Security Bank an aggregate amount of P1,120,000

§ Dela Cruz delivered the CTDs to Caltex for his purchase of fuel products.

§ On a later date, Dela Cruz approached the bank manager, communicated the loss of certificates and

requested for reissuance. Upon compliance with some formal requirements, he was issued

replacements on March 18, 1982.

§ March 25, 1982: Dela Cruz negotiated and obtained a loan from Security Bank in the amount of

P875,000 and executed a notarized Deed of Assignment of Time Deposit.

§ November, 1982: Mr. Aranas, Credit Manager of Caltex went to the Sucat branch to verify the CTDs

declared lost by Dela Cruz alleging that the same were delivered to them as a SECURITY for

purchases made with petitioner by Dela Cruz.

§ November 26, 1982: Security Bank received a letter from Caltex formally informing it of its possession

of the CTDs in question and of its decision to pre-terminate the same.

§ December 8, 1982: Caltex was requested by Security Bank to furnish a copy of the document

evidencing the guarantee agreement with Dela Cruz and the details of his obligation against which

Caltex proposed to apply the time deposits.

§ Security Bank rejected Caltex demand for payment because it failed to furnish a copy of its agreement

w/ Dela Cruz.

§ April 1983, the loan of Dela Cruz with Security Bank matured.

§ August 5, 1983: CTD were set-off w/ the matured loan and applied the time deposits as payment for

the loan.

§ Caltex filed a complaint praying the bank to pay 1,120,000 plus 16% interest.

§ CA affirmed RTC to dismiss complaint on the ground that CTDs are non-negotiable and that the

petitioner did not become a holder in due course of the said certificate of deposits.

NEGOTIABLE INSTRUMENTS AND INSOLVENCY LAW – 2H 2020-2021

ISSUE/S 1. W/N CTDs are negotiable instrument.

2. W/N the petitioner is the holder in due course of the CTDs.

RULING/S

1. Yes. CTDs in question are negotiable instruments as they meet the requirements of the law for

negotiability as provided for in Section 1 of the Negotiable Instruments Law. Section 1 Act No. 2031,

otherwise known as the Negotiable Instruments Law, enumerates the requisites for an instrument to

become negotiable, viz:

(a) It must be in writing and signed by the maker or drawer;

(b) Must contain an unconditional promise or order to pay a sum certain in money;

(c) Must be payable on demand, or at a fixed or determinable future time;

(d) Must be payable to order or to bearer; and

(e) Where the instrument is addressed to a drawee, he must be named or otherwise indicated

therein with reasonable certainty.

The accepted rule is that the negotiability or nonnegotiability of an instrument is determined from the

writing, that is, from the face of the instrument itself. In the construction of a bill or note, the intention of

the parties is to control, if it can be legally ascertained. While the writing may be read in the light of

surrounding circumstances in order to more perfectly understand the intent and meaning of the parties,

yet as they have constituted the writing to be the only outward and visible expression of their meaning,

no other words are to be added to it or substituted in its stead. The duty of the court in such case is to

ascertain, not what the parties may have secretly intended as contradistinguished from what their words

express, but what is the meaning of the words they have used. What the parties meant must be

determined by what they said.

Contrary to what respondent court held, the CTDs are negotiable instruments. The documents provide

that the amounts deposited shall be repayable to the depositor. And who, according to the document, is

the depositor? It is the "bearer." The documents do not say that the depositor is Angel de la Cruz and that

the amounts deposited are repayable specifically to him. Rather, the amounts are to be repayable to the

bearer of the documents or, for that matter, whosoever may be the bearer at the time of presentment.

If it was really the intention of respondent bank to pay the amount to Angel de la Cruz only, it could have

with facility so expressed that fact in clear and categorical terms in the documents, instead of having the

word "BEARER" stamped on the space provided for the name of the depositor in each CTD. On the

wordings of the documents, therefore, the amounts deposited are repayable to whoever may be the

bearer thereof.

2. NO. The records reveal that Angel de la Cruz delivered the CTDs amounting to P1,120,000.00 to

petitioner without informing respondent bank thereof at any time. Unfortunately for petitioner, although the

CTDs are bearer instruments, a valid negotiation thereof for the true purpose and agreement between it

and De la Cruz, as ultimately ascertained, requires both delivery and indorsement. For, although petitioner

seeks to deflect this fact, the CTDs were in reality delivered to it as a security for De la Cruz' purchases

of its fuel products. Any doubt as to whether the CTDs were delivered as payment for the fuel products or

as a security has been dissipated and resolved in favor of the latter by petitioner's own authorized and

responsible representative himself.

Petitioner's insistence that the CTDs were negotiated to it begs the question. Under the Negotiable

Instruments Law, an instrument is negotiated when it is transferred from one person to another in such a

manner as to constitute the transferee the holder thereof, and a holder may be the payee or indorsee of

a bill or note, who is in possession of it, or the bearer thereof. In the present case, however, there was no

negotiation in the sense of a transfer of the legal title to the CTDs in favor of petitioner in which situation,

for obvious reasons, mere delivery of the bearer CTDs would have sufficed. Here, the delivery

thereof only as security for the purchases of Angel de la Cruz (and we even disregard the fact that the

amount involved was not disclosed) could at the most constitute petitioner only as a holder for value by

reason of his lien. Accordingly, a negotiation for such purpose cannot be affected by mere delivery of the

instrument since, necessarily, the terms thereof and the subsequent disposition of such security, in the

event of non-payment of the principal obligation, must be contractually provided for.

You might also like

- (Mahaba Ver) Caltex v. CA and Security Bank and Trust CompanyDocument4 pages(Mahaba Ver) Caltex v. CA and Security Bank and Trust CompanyYvonne MallariNo ratings yet

- Caltex v. CADocument2 pagesCaltex v. CAReymart-Vin MagulianoNo ratings yet

- Caltex Phil. vs. CADocument3 pagesCaltex Phil. vs. CAKym AlgarmeNo ratings yet

- NEGO CasesDocument23 pagesNEGO CasesMorgana BlackhawkNo ratings yet

- Caltex v Court of Appeals Ruling on Negotiability of CTDsDocument2 pagesCaltex v Court of Appeals Ruling on Negotiability of CTDsKaren Ryl Lozada BritoNo ratings yet

- Caltex Philippines Vs CADocument3 pagesCaltex Philippines Vs CAbeth_afanNo ratings yet

- Caltex (Philippines) Vs CA 212 SCRA 448 August 10, 1992 FactsDocument3 pagesCaltex (Philippines) Vs CA 212 SCRA 448 August 10, 1992 FactsHal JordanNo ratings yet

- Trinanes, JA Digests NILDocument3 pagesTrinanes, JA Digests NILJoshua Anthony TrinanesNo ratings yet

- Caltex (Philippines) Inc. vs. CA GR 97753, 10 August 1992 - NegotiabilityDocument5 pagesCaltex (Philippines) Inc. vs. CA GR 97753, 10 August 1992 - Negotiabilitykitakattt100% (1)

- 7 Caltex Philippines Inc. v. Court of AppealsDocument15 pages7 Caltex Philippines Inc. v. Court of AppealsJulius R. TeeNo ratings yet

- Caltex vs CA - Elements of Negotiable Instruments and EstoppelDocument6 pagesCaltex vs CA - Elements of Negotiable Instruments and EstoppelHiroshi CarlosNo ratings yet

- Caltex Vs CA MNDocument1 pageCaltex Vs CA MNmei_2208No ratings yet

- Second Division: Negotiable Instruments Law Act No. 2031 Negotiable Instruments LawDocument106 pagesSecond Division: Negotiable Instruments Law Act No. 2031 Negotiable Instruments LawCzarianne GollaNo ratings yet

- Caltex v. CADocument2 pagesCaltex v. CAReymart-Vin MagulianoNo ratings yet

- Caltex Inc Vs CADocument2 pagesCaltex Inc Vs CAcmv mendozaNo ratings yet

- Caltex vs Court of Appeals: Certificate of Time Deposit as Negotiable InstrumentDocument108 pagesCaltex vs Court of Appeals: Certificate of Time Deposit as Negotiable InstrumentCzarianne GollaNo ratings yet

- Caltex Philippines Inc. v. CADocument14 pagesCaltex Philippines Inc. v. CARein NantesNo ratings yet

- Caltex Phil Inc. VS CaDocument1 pageCaltex Phil Inc. VS CaRengie GaloNo ratings yet

- Caltex V CaDocument2 pagesCaltex V CaCarlyn Belle de Guzman100% (2)

- Caltex vs. CA and Security Bank and Trust Company (GR No. 97753)Document1 pageCaltex vs. CA and Security Bank and Trust Company (GR No. 97753)Katharina CantaNo ratings yet

- (Slightly Maikli) Caltex v. CA and Security Bank and Trust CompanyDocument3 pages(Slightly Maikli) Caltex v. CA and Security Bank and Trust CompanyYvonne MallariNo ratings yet

- Caltex (Phil) Inc., V. CA (212 Scra 448)Document11 pagesCaltex (Phil) Inc., V. CA (212 Scra 448)Eric Villa100% (1)

- Caltex v. Court of AppealsDocument16 pagesCaltex v. Court of AppealsNoel Cagigas FelongcoNo ratings yet

- CALTEX (PHILIPPINES), INC., Petitioner, vs. COURT OF Appeals and Security Bank and Trust CompanyDocument22 pagesCALTEX (PHILIPPINES), INC., Petitioner, vs. COURT OF Appeals and Security Bank and Trust CompanyChristiaan CastilloNo ratings yet

- Court rules on negotiability of certificates of time depositDocument2 pagesCourt rules on negotiability of certificates of time depositsectionbcoeNo ratings yet

- Issues:: Appealed Decision Is Hereby AFFIRMEDDocument2 pagesIssues:: Appealed Decision Is Hereby AFFIRMEDabc12342No ratings yet

- CD 3. Caltex Phil V CADocument2 pagesCD 3. Caltex Phil V CAAlyssa Alee Angeles JacintoNo ratings yet

- Caltex v. CA: CTDs as Negotiable InstrumentsDocument2 pagesCaltex v. CA: CTDs as Negotiable InstrumentsmishiruNo ratings yet

- Caltex Vs CA - G.R. No. 97753. August 10, 1992Document12 pagesCaltex Vs CA - G.R. No. 97753. August 10, 1992Ebbe DyNo ratings yet

- Repayable To The Depositor. The Depositor, As Provided Is The "Bearer." The Documents Do Not SayDocument7 pagesRepayable To The Depositor. The Depositor, As Provided Is The "Bearer." The Documents Do Not SaySelynn CoNo ratings yet

- Nego - Midterms - Case DoctrinesDocument25 pagesNego - Midterms - Case DoctrinesSage LingatongNo ratings yet

- Caltex (Phils.), Inc. vs. Court of AppealsDocument2 pagesCaltex (Phils.), Inc. vs. Court of Appealskaye choiNo ratings yet

- Caltex (Philippines), Inc. vs. Court of Appeals, 212 SCRA 448 (1992) )Document34 pagesCaltex (Philippines), Inc. vs. Court of Appeals, 212 SCRA 448 (1992) )Jacqueline Paulino100% (1)

- Case DigestDocument1 pageCase DigestGericah Rodriguez100% (1)

- Case MatrixDocument10 pagesCase MatrixAly ConcepcionNo ratings yet

- Caltex Vs Ca DigestDocument2 pagesCaltex Vs Ca DigestAnonymous joKjxH6No ratings yet

- CALTEX V CADocument4 pagesCALTEX V CAjodelle11No ratings yet

- 212 Scra 448 RGFMDocument2 pages212 Scra 448 RGFMRhuejane Gay MaquilingNo ratings yet

- Caltex (Phils.) Inc. V. Ca and Security Bank and Trust Co. (1992) FactsDocument11 pagesCaltex (Phils.) Inc. V. Ca and Security Bank and Trust Co. (1992) FactsAerith AlejandreNo ratings yet

- Requisites for Negotiability and Forms of Negotiable InstrumentsDocument23 pagesRequisites for Negotiability and Forms of Negotiable InstrumentsKaren RefilNo ratings yet

- Provisions Applicable Only To Pledge DigestsDocument9 pagesProvisions Applicable Only To Pledge DigestsMikkaEllaAnclaNo ratings yet

- Caltex V CA & Security Bank and Trust CompanyDocument2 pagesCaltex V CA & Security Bank and Trust CompanyMaureen CoNo ratings yet

- Caltex Vs CA (Digest)Document2 pagesCaltex Vs CA (Digest)Glorious El Domine100% (1)

- Negotiable Instruments LawDocument2 pagesNegotiable Instruments LawREA RAMIREZNo ratings yet

- Caltex v. CADocument13 pagesCaltex v. CAJoanne CamacamNo ratings yet

- Negotiability of Treasury Warrants and Certificates of DepositDocument43 pagesNegotiability of Treasury Warrants and Certificates of DepositTsuuundereeNo ratings yet

- CALTEX (PHILIPPINES), INC. vs. COURT OF APPEALS & SECURITY BANK & TRUST COMPANYDocument1 pageCALTEX (PHILIPPINES), INC. vs. COURT OF APPEALS & SECURITY BANK & TRUST COMPANYTrudgeOnNo ratings yet

- Quo and Adopted by Respondent Court, Appears of RecordDocument43 pagesQuo and Adopted by Respondent Court, Appears of RecordAmethyst Vivo TanioNo ratings yet

- Caltex v Security Bank CTD Assignment CaseDocument3 pagesCaltex v Security Bank CTD Assignment CaseAgee Romero-ValdesNo ratings yet

- Caltex v. CA (1992)Document1 pageCaltex v. CA (1992)Cathy AlcantaraNo ratings yet

- Caltex (Phils.) Inc. V. Ca and Security Bank and Trust Co. (1992)Document11 pagesCaltex (Phils.) Inc. V. Ca and Security Bank and Trust Co. (1992)Aerith AlejandreNo ratings yet

- Caltex Inc. v. Court of Appeals (G.R. No. 97753. August 10, 1992)Document2 pagesCaltex Inc. v. Court of Appeals (G.R. No. 97753. August 10, 1992)Elmer LucreciaNo ratings yet

- Negotiable Instruments LawDocument38 pagesNegotiable Instruments Lawanna bee67% (3)

- Principal. Thus, The Loan Secured by Gutierrez Is Void.)Document3 pagesPrincipal. Thus, The Loan Secured by Gutierrez Is Void.)Pj DegolladoNo ratings yet

- Caltex VS CaDocument18 pagesCaltex VS CaViolet BlueNo ratings yet

- China Banking Corp V CA and AfpslaiDocument3 pagesChina Banking Corp V CA and AfpslaiPS PngnbnNo ratings yet

- Case NegoDocument6 pagesCase NegoLou StellarNo ratings yet

- A Simple Guide for Drafting of Conveyances in India : Forms of Conveyances and Instruments executed in the Indian sub-continent along with Notes and TipsFrom EverandA Simple Guide for Drafting of Conveyances in India : Forms of Conveyances and Instruments executed in the Indian sub-continent along with Notes and TipsNo ratings yet

- Introduction to Negotiable Instruments: As per Indian LawsFrom EverandIntroduction to Negotiable Instruments: As per Indian LawsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Dishonour of Cheques in India: A Guide along with Model Drafts of Notices and ComplaintFrom EverandDishonour of Cheques in India: A Guide along with Model Drafts of Notices and ComplaintRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- 30 - Leviste Management System Inc. - v. - Legaspi Towers 2000, Inc.Document2 pages30 - Leviste Management System Inc. - v. - Legaspi Towers 2000, Inc.atNo ratings yet

- Case Title People vs. Wagas G.R. NO. G.R. No. 157943 Ponente Bersamin, J. DATE September 4, 2013 DoctrineDocument2 pagesCase Title People vs. Wagas G.R. NO. G.R. No. 157943 Ponente Bersamin, J. DATE September 4, 2013 DoctrineatNo ratings yet

- Case Title People vs. Wagas G.R. NO. G.R. No. 157943 Ponente Bersamin, J. DATE September 4, 2013 DoctrineDocument2 pagesCase Title People vs. Wagas G.R. NO. G.R. No. 157943 Ponente Bersamin, J. DATE September 4, 2013 DoctrineatNo ratings yet

- Aguilar v. Lightbringers Credit CooperativeDocument2 pagesAguilar v. Lightbringers Credit Cooperativeat0% (1)

- Case Title G.R. NO. 157150 Ponente Date Doctrine: Bersamin, J.: September 21, 2011Document2 pagesCase Title G.R. NO. 157150 Ponente Date Doctrine: Bersamin, J.: September 21, 2011atNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law Cases CompilationDocument7 pagesConstitutional Law Cases CompilationatNo ratings yet

- San Beda University College of Law MendiolaDocument6 pagesSan Beda University College of Law MendiolaatNo ratings yet

- The Constitution of The PhilippinesDocument40 pagesThe Constitution of The PhilippinesatNo ratings yet

- TABLE OF CONTENTS CASE DIGESTS AND ETHICAL RULESDocument26 pagesTABLE OF CONTENTS CASE DIGESTS AND ETHICAL RULESatNo ratings yet

- A. Cruz v. Secretary of Environment and Natural Resources, G.R. No. 135383, 6 December 2000 B. Secretary of DENR v. Yap, G.R. No. 167707, 8 October 2008Document2 pagesA. Cruz v. Secretary of Environment and Natural Resources, G.R. No. 135383, 6 December 2000 B. Secretary of DENR v. Yap, G.R. No. 167707, 8 October 2008atNo ratings yet

- Hiragana Writing Practice SheetsDocument10 pagesHiragana Writing Practice SheetsDina Dinel100% (2)

- Revised Penal Code Elements of Crimes UnDocument47 pagesRevised Penal Code Elements of Crimes UnRommel Tottoc100% (8)

- Revised Penal Code Elements of Crimes UnDocument47 pagesRevised Penal Code Elements of Crimes UnRommel Tottoc100% (8)

- Callanta Notes Criminal Law 2 ReviewerDocument238 pagesCallanta Notes Criminal Law 2 ReviewerYen05567% (3)

- Revised Penal Code Elements of Crimes UnDocument47 pagesRevised Penal Code Elements of Crimes UnRommel Tottoc100% (8)

- Callanta Notes Criminal Law 2 ReviewerDocument238 pagesCallanta Notes Criminal Law 2 ReviewerYen05567% (3)

- 2011 Bar Examination in (With Suggested Answers) : Legal EthicsDocument53 pages2011 Bar Examination in (With Suggested Answers) : Legal EthicsPan RemyNo ratings yet

- Earnest Money Receipt Agreement (Final)Document1 pageEarnest Money Receipt Agreement (Final)v_sharon100% (1)

- Southern Luzon Employees vs. GolpeoDocument2 pagesSouthern Luzon Employees vs. GolpeoRegina Elim Perocillo Ballesteros-ArbisonNo ratings yet

- Manifestation With Motion To AdmitDocument4 pagesManifestation With Motion To AdmitAron Panturilla100% (2)

- PCSO Vigilant Enterprise Service Agreement For "COVERT LPR TRAILERS"Document13 pagesPCSO Vigilant Enterprise Service Agreement For "COVERT LPR TRAILERS"James McLynasNo ratings yet

- Study GuideDocument154 pagesStudy GuideOseameNo ratings yet

- Armstrong V Winnington NetworksDocument3 pagesArmstrong V Winnington NetworksMichael RhimesNo ratings yet

- Cesar Raet, Et Al. vs. Court of Appeals, Et Al.Document2 pagesCesar Raet, Et Al. vs. Court of Appeals, Et Al.Dana Jeuzel MarcosNo ratings yet

- UCP FAR 14 investment equity securitiesDocument12 pagesUCP FAR 14 investment equity securitieslois martinNo ratings yet

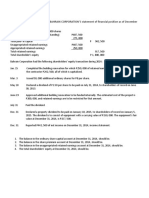

- The Shareholder's Equity Section BAHRAIN CORPORATION'S Statement of Financial Position As of December 31, 2013, Is As FollowsDocument4 pagesThe Shareholder's Equity Section BAHRAIN CORPORATION'S Statement of Financial Position As of December 31, 2013, Is As FollowsCyril John ReyesNo ratings yet

- Civil Law Review Ii: Sales, Lease, Agency, Partnership, Trust and Credit TransactionsDocument74 pagesCivil Law Review Ii: Sales, Lease, Agency, Partnership, Trust and Credit TransactionsyanyanersNo ratings yet

- 2019 Torts Reviewer Ver. 6Document22 pages2019 Torts Reviewer Ver. 6Ellis Lagasca100% (6)

- Maybank Philippines, Inc. (Formerly PNB-Republic Bank) vs. TarrosaDocument12 pagesMaybank Philippines, Inc. (Formerly PNB-Republic Bank) vs. TarrosaAlthea Angela GarciaNo ratings yet

- Lhuillier V British AirwaysDocument2 pagesLhuillier V British AirwaysGrace Managuelod GabuyoNo ratings yet

- Lee County Estate Summary AdministrationDocument2 pagesLee County Estate Summary AdministrationNan EatonNo ratings yet

- Kalaw Vs RelovaDocument5 pagesKalaw Vs Relovalouis jansenNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument14 pagesUntitledSanjeet HoraNo ratings yet

- Difference Between Representation and WarrantiesDocument3 pagesDifference Between Representation and WarrantiesHusain AttarNo ratings yet

- CommercialDocument77 pagesCommercialGNo ratings yet

- Match FractionsDocument6 pagesMatch Fractionsmomztutelage4182No ratings yet

- Board Re So For CompanyDocument6 pagesBoard Re So For CompanydebashisdasNo ratings yet

- 1 MBL Ka Dec11Document18 pages1 MBL Ka Dec11Neha JayaramanNo ratings yet

- Hoffman v. Red Owl Stores, Inc.Document2 pagesHoffman v. Red Owl Stores, Inc.crlstinaaa100% (2)

- Sergio Naguiat Vs National Labor Relations CommissionDocument2 pagesSergio Naguiat Vs National Labor Relations CommissionAbdulateef SahibuddinNo ratings yet

- SMU Company Law Cheat SheetDocument57 pagesSMU Company Law Cheat SheetOng LayLiNo ratings yet

- Nemo Dat Quod Non HabetDocument27 pagesNemo Dat Quod Non HabetRavi RathiNo ratings yet

- Discharge of ContractDocument8 pagesDischarge of ContractMaria AslamNo ratings yet

- Core Word List For Unit 8Document7 pagesCore Word List For Unit 8jeruskaNo ratings yet

- Rera RepresentationDocument8 pagesRera RepresentationSumanth MuvvalaNo ratings yet

- ABS CBN Vs CADocument1 pageABS CBN Vs CACamañanÍvyNo ratings yet

- Civil LawDocument66 pagesCivil LawjrenceNo ratings yet