Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Some Problems Falsificationism in Economics : Caldwell

Uploaded by

sad_jrOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Some Problems Falsificationism in Economics : Caldwell

Uploaded by

sad_jrCopyright:

Available Formats

489

Some Problems with Falsificationism in

Economics*

BRUCE J. CALDWELL, Economics, University of North

Carolina—Greensboro

In a recent review of Mark Blaug’s The Methodology of Economics in this

W. Hands points out that Blaug’s treatment of

journal (14, 1984, 115-25), D.

contemporary philosophy of science and his assessment of various research

programmes in economics reveal an inconsistency (1984, pp. 122-23).

The fundamental problem of Blaug’s criticism of economic practice is that it either

completely neglects, or at least is inconsistent with, everything he stated in his survey of

philosophy of science. His principal criticism is that there is not enough ’falsification’ or

even ’falsifiability’ in modem economics. In light of the previously discussed work of

Kuhn, Feyerabend, Lakatos, et al., one is inclined to retort so what! The unambiguous

conclusion of recent philosophy of science, which Blaug so accurately surveys in Part I, is

that no science does that which Blaug criticizes economics for not doing.

If Blaug is caught in an inconsistency (and I believe that he is), he must give up

either his position on philosophy or his optimism about the prospects for putting

falsificationism to work in economics.

Though Hands’s points are well-taken, they would not persuade a convinced

Popperian. An advocate of falsificationism would first note that Popper has

responded to his growth of knowledge critics, none of whose positive pro-

grammes have themselves escaped unscathed from criticism. He would next

argue that, since falsificationism is a prescriptive methodology, its failure to be

tried so far should not count against it: the point of a prescriptive methodology is

to change behaviour, after all. And finally, a proponent would point out that the

general claim that falsificationism may not work in the social sciences is unim-

pressive unless it is supported by specific reasons why one should expect it to be

unsuccessful.

To complete the task begun in Hands’s review, it is necessary to demonstrate

that falsificationism is, indeed, an inapplicable methodological stance for econ-

omics. After briefly describing falsificationism, such a demonstration is at-

tempted.

1. FALSIFICATIONISM DEFINED

Defining falsificationism is not easy. It should come as no surprise that Popper’ss

views have undergone some modification in the roughly fifty years since the

publication of Logik der Forschung in 1934. Nor is it possible here to include his

views on inductivism, fallibilism, verisimilitude, critical rationalism, objective

knowledge, and so on. Fortunately, all that is necessary in relating fal-

* Parts of this paper are drawn from Chapter 12 of my book, Beyond Positivism:

Economic Methodology in the Twentieth Century, London 1982.

1 Those unfamiliar with Popper’s work should begin with the autobiography in Schilpp,

ed. (1974), or, for a shorter version, Popper (1965), Chapter 1. Next, see Popper (1934);

Eng. trans. 1959), (1965), and (1972). The best secondary source is Ackermann (1976).

Downloaded from pos.sagepub.com at NORTH CAROLINA STATE UNIV on May 8, 2015

490

sificationism to the problems encountered by the working economist is a de-

scription of how falsificationism applies to the testing of scientific hypotheses.

Simply put, a necessary and sufficient condition for the application of fal-

sificationism in economics is that straight-forward tests of hypotheses be possi-

ble. A test of an hypothesis is always conditional. Every conditional hypothesis

is composed of two parts: an explanandum and an explanans. The explanandum

is a sentence describing the phenomenon to be explained. The explanans con-

tains sentences comprising a list of initial conditions which must obtain (these

can include both the variables impounded in ceteris paribus and those in which a

change is assumed to occur), and sentences presenting general laws. For a

straightforward test of an hypothesis to occur, the initial conditions and general

laws must be clearly specifiable and specified. In addition, any empirical proxies

which are chosen to represent theoretical concepts must permit a true test of the

theory. Finally, the data themselves must be clean.22

If all of these conditions are met, the results of tests of hypotheses are

relatively easy to interpret. Confirming instances, as always, cannot prove that a

hypothesis is true. But disconfirming test instances will direct scientists to

reinspect the initial conditions, general laws, data and test situation to see what

went wrong. If each of these is clearly defined, problems are discovered and

corrected, and by this slow, critical, trial and error process, science may hope-

fully advance. The argument against the workability of falsificationism in econ-

omics is based on the contention that rarely will all of the conditions mentioned

above be met. Not surprisingly, growth of knowledge philosophers made the

same point in criticizing the workability of Popper’s methodology in the natural

sciences.3 As Hands suggests, the problems seem even more serious in the social

science of economics.

2. OBSTACLES TO FALSIFICATIONISM IN ECONOMICS

a . Initial conditions are numerous-It is impossible to specify all of the neces-

sary initial conditions in any test

situation, even in the laboratory sciences. As a

practical matter, however, one can begin to have confidence about the results of

a test if the important determining variables are finite in number and specifiable.

A true test of a theory occurs if all the exogenous variables are known, one is

varied while the others are held constant, and the effects are noted. Obviously,

such carefully controlled experimentation cannot occur in economics. In gen-

eral, not all exogenous variables are known, and a number of them vary simul-

taneously. This does not preclude the possibility of testing in economics, how-

ever : multivariate analysis is expressly designed for handling these problems.

Why then have certain economists claimed that a large number of exogenous

variables somehow damages the credibility of tests of hypotheses in economics?

There are, I think, two distinct complaints lying behind such a claim.

Some critics charge that the models of economists give a distorted, incorrect

representation of reality. This argument is often made by Institutionalists, who

prefer a more holistic approach to social phenomena. Thus Wilber and Harrison

assert that the use of a ceteris paribus clause in a closed, causal model lends a

2 This discussion follows Hempel and Oppenheim’s (1948) presentation of deductive

explanation under covering laws, but is completely compatible with Popper’s model of

deductive explanation as developed in his (1959).

3 For example, this is the reasoning underlying Lakatos’ (1970) views on the absence of

crucial tests and ’instant rationality’ in science, which leads him to conclude,’The main

difference from Popper’s original version is, I think, that in my conception criticism

does not—and must not—kill as fast as Popper imagined’ (p. 179).

Downloaded from pos.sagepub.com at NORTH CAROLINA STATE UNIV on May 8, 2015

491

’degree of determinedness’ to the model which does not exist in the subject

matter.Sidney Schoeffler makes a similar point when he argues that economic

systems, because they are ’essentially open’, cannot be adequately captured by

4

a closed model.4

A second concern of critics is that, while theories are stated causally,

econometric specifications of theories are only capable of indicating correlations

among variables. This has a number of implications. Few econometricians

expect the estimates of coefficients to be the same when different observations

of the same variables are used. It is often true that the addition or deletion of

particular variables may profoundly affect the estimated values and significance

of the coefficients of the remaining variables. The relationships among variables

that emerge from an econometric model thus have little in common with the

well-specified, causal relationships that exist in economic theories.

Might not such a situation be remedied someday, either when all the exogen-

ous variables involved in a particular test are discovered, or, better yet, when all

are ’endogenized’? As Emile Grunberg has shown, any attempt to ’endogenize’

exogenous variables leads to an infinite regress, since every variable now

considered exogenous is itself determined by other exogenous variables (1978).

Nor do economists seem to feel it necessary to try to specify all the exogenous

variables: it is easier to close a model by simply including some variable that

captures any relationships not explicitly specified.5 Finally, as the institutional

structure of the economy changes through time, it is likely that relationships that

once held among variables may be altered, and that new variables may be

discovered.

Reasonable men may disagree over whether the ’abstract deductive method’

or the more holistic, ’story-telling’ or ’pattern model’ approach favoured by the

Institutionalists is better for studying social reality. The first complaint, then,

primarily concerns preferences in theorizing. The second is more serious: it

involves limitations of econometric techniques that are well-known in the pro-

fession, but whose implications for the prospects of falsificationism have not

been generally recognized. When the number of exogenous variables is large,

when the universe of those variables is subject to change through time, and

when, as a result, many variables are left unspecified, there is little reason to

believe that the causal relationships postulated in economic theories are well-

represented by the relationships which emerge in an econometric model. Test

results, either confirming or disconfirming, must be interpreted cautiously.

b. Some initial conditions are untestable-Certain initial conditions, though

themselves exogenously determined and subject to change, are not indepen-

dently testable. Two that figure prominently in economic theory are tastes and

preferences and the state of information. Economists generally handle these

problems by assuming that preferences are stable and well-ordered, and by

assuming either that information is perfect or that uncertainty is reducible to

risk.6 This poses no problem at the theoretical level, but difficulties arise when

4 Wilber and Harrison (1978);Schoeffler(1955). This point has been made by a number of

on methodology; see, for example, Hutchison (1938),

economists in their writings

Machlup (1955; 1966), Grunberg (1978).

5 In demand theory, ’tastes and preferences’ and ’expectations of future prices and

income’ play this role. In Friedman’s (1974) theoretical model of the demand for

money, he includes the variable u, which ’is a portmanteau symbol standing for

whatever variables other than income may affect the utility attached to the services of

money’ (p. 13).

6 Regarding tastes and preferences, another gambit, developed by Stigler and Becker

Downloaded from pos.sagepub.com at NORTH CAROLINA STATE UNIV on May 8, 2015

492

the theories are tested empirically: neither confirming nor disconfirming in-

stances are unambiguously interpretable if these initial conditions cannot be

independently tested.~7

c. Absence of falsifiable general laws-Though economists often use the

term ’economic law’, it is used to refer to a wide variety of propositions.

Compared to the many debates over how the term general law should be defined

within the philosophy of science, economists have virtually ignored the question

in their methodological debates.

Some consider the rationality postulate to be the fundamental behavioural law

in economics: Hutchison and Machlup took this approach in their debate in the

fifties, for example.8 If that is the case, then economists must admit that their

most basic general law is not directly testable.9 This poses no problem for

instrumentalists, who only require that theories be evaluated by how well their

predictions conform to reality. But a falsificationist, who requires that discon-

firming test instances be treated seriously, would be alarmed to find out that

disconfirming test instances cannot be unambiguously interpreted, that one can

never know whether the assumed initial conditions or the behavioural law has

been falsified. Though the theoretical definition of rationality has been resolved

by economists (transitivity in choice over a well-ordered preference function),

its empirical interpretation has always remained problematical. Can rationality

be defined in the absence of full information? Is there a difference between short

run and long run rationality? Does Simon’s (1976) distinction between substan-

tive and procedural rationality hold any promise for resolving this dilemma? The

questions go on and on.

There are other candidates for general laws in economics. The ’law’ of

diminishing marginal returns is certainly one. But, as is often noted, this

hypothesis when correctly stated only implies that returns will eventually di-

minish. This necessary caveat renders the ’law’ effectively unfalsifiable, how-

ever : one may always respond to a disconfirming instance that ’we simply have

not reached the point of diminishing returns yet’. And indeed, perhaps the major

difference between the Classicals and modern treatments of the ’law of diminish-

ing returns’ is that, whereas the Classicals believed the law was operative and

observable in history, modern economists view it as an analytic device.

The ’law’ of demand is another example. In a recent work, Terence Hutchison

(1977) points out that, in the absence of checkable initial conditions, especially

regarding tastes, prices of other goods, and price expectations, the law is

effectively untestable. Hutchison also comments on so-called empirical laws in

economics, and compares them with laws in the natural sciences (pp. 19-20).

Since very few or no fully adequate scientific laws, in the physico-chemical or natural

scientific sense, have been established in economics, on which economists can base

predictions, what are used, and have to be used, for predictive purposes are trends,

(1977), is to claim that tastes and preferences are themselves determined by income and

relative prices, hence analyzable using the usual tools of the economist.

7 This can be easily shown. Say the rationality postulate (transitivity in choice over a

well-ordered preference function) is tested using the revealed preference approach.

Transitive choice is taken to mean the consumer is rational, but if his preference

function was not well-ordered (because tastes changed or information was imperfect),

transitivity in choice reveals the consumer as irrational. Similarly, if intransitivities are

revealed, is the consumer irrational, or do we assume that there was a change in one of

the initial conditions?

8 Hutchison (1956), Machlup (1955; 1956).

9 See footnote 7.

Downloaded from pos.sagepub.com at NORTH CAROLINA STATE UNIV on May 8, 2015

493

tendencies, or patterns, expressed in empirical or historical generalizations of less than

universal validity, restricted by local and temporal limits.

Hutchison cites as an example that, even if the elasticity of demand for herrings

over a period of years lay between 1.2 and 1.45, ’it surely cannot be claimed to be

a universal law, that in all markets, in all countries, at all times, the elasticity of

demand for herrings is, and has always been, between 1.2 and 1.45’. Hutchison

concludes that the primary contribution of economists ‘must inevitably come

from trend-spotting, not by deduction from laws’ (pp. 21, 22).

As he did some forty years ago, Hutchison argues in his book against the idea

that economics proceeds by deduction from universal laws. As he admits, his is a

somewhat skeptical position: even well-tested generalizations that have per-

formed perfectly in the past need not be applicable in the future, especially if the

structural relationships within an economy change. Empiricism is then still quite

important to Hutchison. But it must also be recognized that, in the absence of

checkable initial conditions and general laws, the hope for the success of fal-

sificationism in economics grows dimmer.

d. Tests of models are not tests of theories-Though this idea can be found in

Papandreou’s Economics as a Science (1958), it has been forcefully and

eloquently restated in a recent piece by Boland (1977). He notes that the concept

of testability has been variously interpreted by economists, but settles on the

definition, ’empirically refutable’. He then argues that, for three reasons, ’it is

impossible to test any economic theory convincingly even when it is not

tautological’ (p. 93). Two of these reasons concern the nature of testing and of

logic, and are similar to arguments that have already been made. The third,

however, is unique. Boland shows that, to test a theory, a model must be

constructed. However, a wide variety of models may be constructed to repre-

sent any theory. As a result, the empirical falsification of any single model does

not imply the falsification of the theory. Falsification of theories, as opposed to

models, is thus impossible in economics (pp. 93-103).

e. Empirical data may not accurately represent theoretical constructs-A

final obstacle to falsificationism in economics concerns the interpretation of

data. Many economists have commented on the ’aggregation problem’ in econ-

omics, which refers to the difficulties that are encountered both in aggregating

data in macroeconomics, and in providing meaningful interpretations of what

those data are meant to represent.10 But even when microeconomic data are

used, problems may arise. In his discussion of how economists might

’operationalize’ the seemingly innocuous construct, ’the price of steel’, Fritz

Machlup concludes that ’one could propose as many as fifty different sets of

operations, all sensible and reasonable, but yielding different findings’ (1966,

p. 58). Wilber and Harrison offer a more general, and pointedly skeptical,

assessment of this problem (1978, p. 69).

Both the methods of collection and construction of economic data are unreliable. Typi-

cally, economic data are statistically constructed and are not conceptually the same as the

corresponding variables in the theory. Therefore, econometricians and statisticians en-

gage in data massaging. If a test disconfirms a hypothesis, the investigator can always

blame the data: they have been massaged, either too much or not enough.

10 For some discussions of the many forms of aggregation problems confronting

economists, see Blaug (1975), Lancaster (1966), Morgenstern (1979). Schelling (1978)

offers an eclectic and highly readable approach to the aggregation problem in the social

sciences generally; his book is suitable for classroom use in many disciplines.

Downloaded from pos.sagepub.com at NORTH CAROLINA STATE UNIV on May 8, 2015

494

3. CONCLUSION

Falsificationism does not guarantee that its use will lead scientists always to

choose the ’true’ theory. It is a more modest methodology of theory appraisal-

its aim is only the avoidance of error; its method is to eliminate theories that have

been falsified by strict empirical tests. But for falsificationism to be viable,

straightforward empirical tests must be possible. This requires that general laws

be present; that initial conditions be relatively few in number, known, not

subject to change, and easily checkable; that a test be a test of a theory, not a

model; that data be trustworthy, complete, and accurately representative of

analogous constructs in the theory. It is now perhaps understandable why

falsificationism, though dominant in the methodological literature, seems to

have been little practiced by working economists.

The invocation to try to put falsificationism into practice in economics need

not be dropped, though it seems that there is little chance for its successful

application. What must be avoided is the wholesale rejection of research pro-

grammes that do not meet the falsificationist criteria of acceptability, for that

would lead to an elimination, not only of alternative research programmes like

those proposed by Austrians and Institutionalists, but much of standard econ-

omic theory, as well

For their part, I think economic methodologists could better serve their

profession by attempting the sort of ‘empirical philosophy of history’ mentioned

by Hands (p. 3). Though the problems of circularity and irrationality which

plague that approach are formidible, it still seems to make sense for economic

methodologists to start with the practice of economists, rather than with the

writings of prescriptivist philosophers of science, in coming to terms with the

methodology of their discipline.

REFERENCES

Ackermann, R. J. (1976) The Philosophy of Karl Popper. Amherst, Mass.

Blaug, M. (1975) The Cambridge Revolution: Success or Failure? Revised ed., London.

— (1980) The Methodology of Economics: Or How Economists Explain. Cam-

bridge, U.K.

Boland, L. ( 1977) ’Testability in Economic Science’, South African Journal of Economics,

45, 93-105.

Friedman, M. (1974) ’A Theoretical Framework for Monetary Analysis’, in R. Gordon

(ed.), Milton Friedman’s Monetary Framework. Chicago.

Grunberg, E. (1978) ’"Complexity" and "Open Systems" in Economic Discourse’,

Journal of Economic Issues, 12, 541-60.

Hands, D. (1984) ’Blaug’s Economic Methodology’, 14, Philosophy of the Social Sciences,

115-25.

Hempel, C., and Oppenheim, P. (1948) ’Studies in the Logic of Explanation’, Philosophy

of Science, 15, 135-75.

Hutchison, T. (1938) The Significance and Basic Postulates of Economic Theory. London.

— (1956)’Professor Machlup on Verification in Economics’, Southern Economic

Journal, 22, 476-83.

— (1977) Knowledge and Ignorance in Economics. Chicago.

Lancaster, K. (1966) ’Economic Aggregation and Additivity’, in S. Krupp (ed.), The

Structure of Economic Science: Essays on Methodology. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.,

pp. 201-15.

Machlup. F. (1955) ’The Problem of Verification in Economics’, Southern Economic

Journal, 21. 1-21.

11 This point is recognized by Blaug (1980), p. 259.

Downloaded from pos.sagepub.com at NORTH CAROLINA STATE UNIV on May 8, 2015

495

(1956) ’Reply to a Reluctant Ultra-Empiricist’, Southern Economic Journal,

22, 483-93.

— (1966) ’Operationalism and Pure Theory in Economics’, in S. Krupp (ed.), The

Structure of Economic Science: Essays on Methodology. Englewood Cliffs, N.J., pp.

53-67.

Morgenstern, O. ( 1979) National Income Statistics: A Critique of Macroeconomic Aggre-

gation. Second ed., San Francisco.

Papandreou, A. (1958) Economics as a Science. Chicago.

Popper, K. (1959) The Logic of Scientific Discovery. Eng. trans., New York.

— (1965) Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge.

Second ed., New York.

— (1972) Objective Knowledge: An Evolutionary Approach, Oxford.

— (1974) ’Intellectual Autobiography’, in P. Schilpp (ed.), The Philosophy of Karl

Popper, Vol. 1. Lasalle, Ill., pp. 3-181.

Schelling, T. (1978) Micromotives and Macrobehavior. New York.

Schoeffler, S. (1955) The Failure of Economics: A Diagnostic Study. Cambridge, Mass.

Simon, H. (1976) ’From Substantive to Procedural Rationality’, in S. Latsis (ed.), Method

and Appraisal in Economics. Cambridge, U.K.

Stigler, G. and Becker, G. (1977) ’De Gustibus Non Est Disputandum’, American Econ-

omic Review, 67, 79-90.

Wilber, C. and Harrison, R. (1978) ’The Methodological Basis of Institutionalist Econ-

omics : Pattern Model, Storytelling and Holism’, Journal of Economic Issues, 12,

61-89.

Downloaded from pos.sagepub.com at NORTH CAROLINA STATE UNIV on May 8, 2015

You might also like

- Introduction to Clinical Assessment MethodsDocument7 pagesIntroduction to Clinical Assessment MethodsJahnaviNo ratings yet

- Rules For Scientific Research in Economics The Alpha Beta MethodDocument173 pagesRules For Scientific Research in Economics The Alpha Beta MethodJoan MirandaNo ratings yet

- Comparative and Superlative Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesComparative and Superlative Lesson Planapi-339056821100% (6)

- Claude Diebolt, Michael Haupert (Eds.) - Handbook of Cliometrics (2016, Springer References)Document597 pagesClaude Diebolt, Michael Haupert (Eds.) - Handbook of Cliometrics (2016, Springer References)André Martins100% (1)

- Internal Versus External Control of Reinforcement PDFDocument5 pagesInternal Versus External Control of Reinforcement PDFKharubi Pagar AlhaqNo ratings yet

- (Routledge Library Editions - Social Theory 60) Michael Mulkay - Science and The Sociology of Knowledge-Routledge (2014)Document143 pages(Routledge Library Editions - Social Theory 60) Michael Mulkay - Science and The Sociology of Knowledge-Routledge (2014)sad_jrNo ratings yet

- (Routledge Library Editions - Social Theory 60) Michael Mulkay - Science and The Sociology of Knowledge-Routledge (2014)Document143 pages(Routledge Library Editions - Social Theory 60) Michael Mulkay - Science and The Sociology of Knowledge-Routledge (2014)sad_jrNo ratings yet

- Praxeology As The MethodDocument21 pagesPraxeology As The MethodAdrian AntkowiakNo ratings yet

- Oligopoly in The LabDocument43 pagesOligopoly in The Labeconomics6969No ratings yet

- Victor A. BekerDocument23 pagesVictor A. BekerJshea11No ratings yet

- Sesi 5_Article Summary Starmer_180324Document8 pagesSesi 5_Article Summary Starmer_180324Eri KusumaNo ratings yet

- Ompetition As A Iscovery Rocedure: T M S. S IDocument15 pagesOmpetition As A Iscovery Rocedure: T M S. S IantitrusthallNo ratings yet

- Inductive and Deductive Method of ResearchDocument3 pagesInductive and Deductive Method of ResearchDinesh KumarNo ratings yet

- Topic 2Document18 pagesTopic 2mphoNo ratings yet

- Ideology and Methodology Duncan FoleyDocument11 pagesIdeology and Methodology Duncan Foley신재석No ratings yet

- PIER Working Paper 12-001: "Economic Models As Analogies"Document32 pagesPIER Working Paper 12-001: "Economic Models As Analogies"tjohns56No ratings yet

- Metodo de La PraxeologiaDocument22 pagesMetodo de La PraxeologiaFernanda JimenezNo ratings yet

- Freedman - Shoe Leather Statistical ModelDocument24 pagesFreedman - Shoe Leather Statistical ModelArchivo RCNo ratings yet

- Anomalies in Finance - What Are They and What Are They Good ForDocument23 pagesAnomalies in Finance - What Are They and What Are They Good ForTrần Mai HươngNo ratings yet

- Econophysics and The Social Sciences: Challenges and OpportunitiesDocument12 pagesEconophysics and The Social Sciences: Challenges and OpportunitiesHenrique97489573496No ratings yet

- 時光機 2019科技部結案報告=自己2002 博士論文Document40 pages時光機 2019科技部結案報告=自己2002 博士論文Rebecaa JuleeNo ratings yet

- 11 PDFDocument32 pages11 PDFJane BalesacanNo ratings yet

- Statistical Models and Shoe LeatherDocument43 pagesStatistical Models and Shoe LeatheredgardokingNo ratings yet

- Oxford - 03. Wren-Lewis (2018)Document15 pagesOxford - 03. Wren-Lewis (2018)Juan Ignacio Baquedano CavalliNo ratings yet

- The University of Chicago Press Journal of Political EconomyDocument11 pagesThe University of Chicago Press Journal of Political EconomyStefanAndreiNo ratings yet

- Lavanya Session2 Clarifying PopperDocument18 pagesLavanya Session2 Clarifying PopperLavanyaNo ratings yet

- Methods of Economic AnalysisDocument25 pagesMethods of Economic AnalysisPritam Banik49No ratings yet

- An Agenda For Reforming Economic Theory: Paradigm in Monetary Economics, Cambridge University Press, 2003Document15 pagesAn Agenda For Reforming Economic Theory: Paradigm in Monetary Economics, Cambridge University Press, 2003api-26091012No ratings yet

- Is Economics a science? Exploring definitions and challengesDocument10 pagesIs Economics a science? Exploring definitions and challengesanimeshkumarvermaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 The Methodology of Economic Research: AidankaneDocument5 pagesChapter 3 The Methodology of Economic Research: AidankaneSrira BanerjeeNo ratings yet

- What Would A Scientific Economics Look Like?: Peter DormanDocument7 pagesWhat Would A Scientific Economics Look Like?: Peter DormanjrodascNo ratings yet

- The Philosophy of Karl Popper, Liberal Governance and The Social Control of TechnologyDocument5 pagesThe Philosophy of Karl Popper, Liberal Governance and The Social Control of Technologyj.c.canizaresgazteluNo ratings yet

- Theory Psych 2009Document19 pagesTheory Psych 2009Farrukh KazmyNo ratings yet

- The Vanity of Rigour in Economics Theoretical ModeDocument43 pagesThe Vanity of Rigour in Economics Theoretical ModeFranco ImpaNo ratings yet

- A Behavioral Economics ViewDocument19 pagesA Behavioral Economics ViewValentina Vera CortésNo ratings yet

- Behavioral Economics: August 2005Document53 pagesBehavioral Economics: August 2005S NeNo ratings yet

- Response To "Worrying Trends in Econophysics": Jmccauley@uh - EduDocument26 pagesResponse To "Worrying Trends in Econophysics": Jmccauley@uh - EduHenrique97489573496No ratings yet

- TOK Sample Essay ADocument6 pagesTOK Sample Essay AShafin MohammedNo ratings yet

- The Vanity of Rigour in Economics Theoretical ModeDocument43 pagesThe Vanity of Rigour in Economics Theoretical ModeAn RoyNo ratings yet

- LopezDePrado (2015) FutureOfEmpiricalFinanceDocument12 pagesLopezDePrado (2015) FutureOfEmpiricalFinanceFarid RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Introductory Concepts - 2022 BatchDocument7 pagesIntroductory Concepts - 2022 BatchCharlie DeltaNo ratings yet

- H3 Economics PapersDocument21 pagesH3 Economics Papersdavidboh100% (1)

- University of California Berkeley: IbraryDocument45 pagesUniversity of California Berkeley: IbraryMaysin LozanoNo ratings yet

- University of California Berkeley: IbraryDocument20 pagesUniversity of California Berkeley: IbraryAlexandra LeyvaNo ratings yet

- Value JudgementDocument30 pagesValue JudgementShen WilliamNo ratings yet

- Statistical Models and Shoe Leather: David A. FreedmanDocument24 pagesStatistical Models and Shoe Leather: David A. Freedmanaqsamushtaq2970No ratings yet

- Capm and EmhDocument29 pagesCapm and EmhNguyễn Viết ĐạtNo ratings yet

- Neoclassical Economics As A Method of Scientific Research Program: A Review of Existing LiteratureDocument19 pagesNeoclassical Economics As A Method of Scientific Research Program: A Review of Existing LiteratureLazar MilinNo ratings yet

- Theory, Experiment and Economics: Vernon L. SmithDocument20 pagesTheory, Experiment and Economics: Vernon L. Smitharkhea studioNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id3104826Document5 pagesSSRN Id3104826Richard LindseyNo ratings yet

- ansell_what_is_democratic_experimentDocument34 pagesansell_what_is_democratic_experimentcarolina_stcNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S027269639800028X Main PDFDocument17 pages1 s2.0 S027269639800028X Main PDFLeonardo GomesNo ratings yet

- Summers 1991Document21 pagesSummers 1991FedericoGlusteinNo ratings yet

- Economic Models Provide Explanations-What of Historical PhenomenaDocument21 pagesEconomic Models Provide Explanations-What of Historical PhenomenaSerdar GunerNo ratings yet

- Brennan 2008 - Psychological Voter ChoiceDocument15 pagesBrennan 2008 - Psychological Voter ChoicemoeeneNo ratings yet

- Advanced Economicsciences2017Document12 pagesAdvanced Economicsciences2017Ed ZNo ratings yet

- Are There Laws of Motion of Capitalism?Document23 pagesAre There Laws of Motion of Capitalism?bubulaqNo ratings yet

- Mccubbins Et AlDocument39 pagesMccubbins Et AlBeatriz Penteado RodriguesNo ratings yet

- Methodological Rules, Rationality, and TruthDocument11 pagesMethodological Rules, Rationality, and TruthJohn SteffNo ratings yet

- A Review of The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred NobelDocument17 pagesA Review of The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobelgayatri singhNo ratings yet

- Tariff TheoryDocument16 pagesTariff TheoryFadhillah SidikNo ratings yet

- Microeconomics and Human Behavior: Toward a New Synthesis of Economics and PsychologyFrom EverandMicroeconomics and Human Behavior: Toward a New Synthesis of Economics and PsychologyNo ratings yet

- Freeland Corones 2000 PDFDocument408 pagesFreeland Corones 2000 PDFRenata DutraNo ratings yet

- (Science, Technology and Culture, 1700-1945) Matthew D. Eddy (Editor), David M. Knight (Editor) - Science and Beliefs - From Natural Philosophy To Natural Science, 1700-1900-Routledge (2005)Document287 pages(Science, Technology and Culture, 1700-1945) Matthew D. Eddy (Editor), David M. Knight (Editor) - Science and Beliefs - From Natural Philosophy To Natural Science, 1700-1900-Routledge (2005)sad_jrNo ratings yet

- (Life and Mind - Philosophical Issues in Biology and Psychology) Tim Lewens-Organisms and Artifacts - Design in Nature and Elsewhere-The MIT Press (2004) PDFDocument196 pages(Life and Mind - Philosophical Issues in Biology and Psychology) Tim Lewens-Organisms and Artifacts - Design in Nature and Elsewhere-The MIT Press (2004) PDFAnneMarieNo ratings yet

- A Critical Overview of Biological FunctionsDocument119 pagesA Critical Overview of Biological FunctionsIrtizahussainNo ratings yet

- Freeland Corones 2000 PDFDocument408 pagesFreeland Corones 2000 PDFRenata DutraNo ratings yet

- A Critical Overview of Biological FunctionsDocument119 pagesA Critical Overview of Biological FunctionsIrtizahussainNo ratings yet

- Theoretical Virtues in Eighteenth Century Debates On Animal CognitionDocument35 pagesTheoretical Virtues in Eighteenth Century Debates On Animal Cognitionsad_jrNo ratings yet

- (Life and Mind - Philosophical Issues in Biology and Psychology) Tim Lewens-Organisms and Artifacts - Design in Nature and Elsewhere-The MIT Press (2004) PDFDocument196 pages(Life and Mind - Philosophical Issues in Biology and Psychology) Tim Lewens-Organisms and Artifacts - Design in Nature and Elsewhere-The MIT Press (2004) PDFAnneMarieNo ratings yet

- Science Perspectives On Psychological: The Value of Direct ReplicationDocument6 pagesScience Perspectives On Psychological: The Value of Direct Replicationsad_jrNo ratings yet

- (Science, Technology and Culture, 1700-1945) Matthew D. Eddy (Editor), David M. Knight (Editor) - Science and Beliefs - From Natural Philosophy To Natural Science, 1700-1900-Routledge (2005)Document287 pages(Science, Technology and Culture, 1700-1945) Matthew D. Eddy (Editor), David M. Knight (Editor) - Science and Beliefs - From Natural Philosophy To Natural Science, 1700-1900-Routledge (2005)sad_jrNo ratings yet

- IntDocument2 pagesIntsad_jrNo ratings yet

- Hacking Kinds of PeopleDocument17 pagesHacking Kinds of Peoplesad_jrNo ratings yet

- CitaDocument1 pageCitasad_jrNo ratings yet

- Haesol Bae CV 2023Document9 pagesHaesol Bae CV 2023api-347045710No ratings yet

- Questionnaire Design: Marketing Research-Naval BajpaiDocument45 pagesQuestionnaire Design: Marketing Research-Naval Bajpaiaman100% (1)

- Alpha Angelicum Academy: Activity: Filipino Values MonthDocument1 pageAlpha Angelicum Academy: Activity: Filipino Values MonthMark Lowie Acetre ArtillagasNo ratings yet

- Diversity Lesson Plan Edu 280Document3 pagesDiversity Lesson Plan Edu 280api-582907786No ratings yet

- LG Acquisition - Exercises - 01Document6 pagesLG Acquisition - Exercises - 01Wiktoria KarkoszkaNo ratings yet

- TTX 01 Concept Note TemplateDocument6 pagesTTX 01 Concept Note TemplatePushpa Khandelwal100% (1)

- Assignment 6Document2 pagesAssignment 6j__dNo ratings yet

- Decision Analysis:: Choice of The Best AlternativeDocument46 pagesDecision Analysis:: Choice of The Best AlternativeAyda KhadivaNo ratings yet

- History: Chinese Pidgin English (Also Called Pigeon EnglishDocument2 pagesHistory: Chinese Pidgin English (Also Called Pigeon EnglishGregory JonesNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1 - HookDocument2 pagesLesson 1 - Hookapi-253272001No ratings yet

- The Humanizing Mission of TeachingDocument3 pagesThe Humanizing Mission of TeachingRisa BarritaNo ratings yet

- ADHD symptoms: Hyperactivity, inattention, and poor organizationDocument1 pageADHD symptoms: Hyperactivity, inattention, and poor organizationMiea MieNo ratings yet

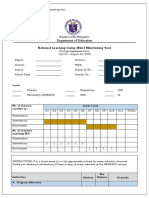

- School Learning Recovery PlanDocument3 pagesSchool Learning Recovery PlanGlydel Octaviano-GapoNo ratings yet

- Critical Lens Essay Analysis OutlineDocument3 pagesCritical Lens Essay Analysis OutlineΑθηνουλα ΑθηναNo ratings yet

- Week 3 - Q1 Oral Com. SHS Module 2Document16 pagesWeek 3 - Q1 Oral Com. SHS Module 2John John BidonNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Summarizing Your SummaryDocument3 pagesLesson Plan Summarizing Your Summaryapi-660091563No ratings yet

- Eng 391 - Inverted Triangle LessonDocument3 pagesEng 391 - Inverted Triangle Lessonapi-250244845No ratings yet

- RANSON, S HININGS, B GREENWOOD, R. The Structuring of Organizational StructuresDocument18 pagesRANSON, S HININGS, B GREENWOOD, R. The Structuring of Organizational StructuresjaddedyouNo ratings yet

- NLC Checklist During ImplementationDocument6 pagesNLC Checklist During ImplementationAlexis V. LarosaNo ratings yet

- Marissa J Corbett ResumeDocument2 pagesMarissa J Corbett Resumeapi-428448687No ratings yet

- Modern PhilosophyDocument2 pagesModern PhilosophyRhodaCastilloNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument3 pagesUntitledRhylyn Khaye ReyesNo ratings yet

- MyDev Session 1 Activity 1Document3 pagesMyDev Session 1 Activity 1Ashley RañesesNo ratings yet

- BS English Syllabus 2013-2Document81 pagesBS English Syllabus 2013-2asadNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1to5 Group of RADZMER-AJIJUL-newDocument61 pagesChapter 1to5 Group of RADZMER-AJIJUL-newAbujarin MahamodNo ratings yet

- Improving Ability in Writing Procedure Text Through Pictures at The 11 Grade Students of Sma Bina Negara 1-BaleendahDocument2 pagesImproving Ability in Writing Procedure Text Through Pictures at The 11 Grade Students of Sma Bina Negara 1-Baleendah-Ita Puspitasari-No ratings yet

- TinnitusDocument4 pagesTinnitusIndriyaniiIntandewataNo ratings yet

- Domain 1Document42 pagesDomain 1DANDY DUMAYAONo ratings yet