Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Adherence To A Wellness Model and Perceptions of PWB

Uploaded by

IsmaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Adherence To A Wellness Model and Perceptions of PWB

Uploaded by

IsmaCopyright:

Available Formats

TOC Electronic Journal: To print this article select pages 91-95.

Adherence to a Wellness Model and Perceptions of

Psychological Well-Being

David A. Hermon and Richard J. Hazler

This study investigated the relationship between college students’ perceived psychological well-being and the quality of their lives

on 5 variables associated with a 5-factor holistic wellness model. The Wellness Evaluation of Lifestyle (Witmer, Sweeney, &

Myers, 1993) and Memorial University of Newfoundland Scale of Happiness (Kozma & Stones, 1994) were completed by 155

undergraduate college students. Multivariate regression analysis revealed a significant relationship between 5 dimensions of

wellness and both short-term state and long-term trait constructs of psychological well-being. Subsequent univariate analysis

found that students’ ability to self-regulate, identity with work, and friendships contributed the most to their psychological well-

being. Implications for college counseling centers and student development professionals are presented.

T

he increasing creation of wellness programs This study follows the directions of institutions, theo-

in higher education are evidence of institutional rists, students, and some researchers in an attempt to fill

efforts to improve the quality of life, psycho- the research gap between our knowledge of physiological

logical well-being and holistic development of aspects of wellness and other dimensions that currently rely

students on campus (Hettler, 1980; Opatz, on more theory than research and practice for their sup-

1986; Sivik, Butts, Moore, & Hyde, 1992. There has not been port. Specifically, it seeks to find whether college students

a matching increase in research studies on the overall effec- who adhere (demonstrated through behaviors and their

tiveness of these actions. The few studies that do exist focus agreement with ideology) to a holistic wellness model re-

primarily on physiological components of wellness (Barth port that they have a greater sense of psychological well-

& Johnson, 1983; Hall, 1992; Johnson & Wernig, 1986; being (measured on affective and quality of experience

Zimpfer, 1992) and ignore most other aspects that would scales) than those students who do not adhere.

make up a holistic view of people’s wellness.

HOLISTIC WELLNESS

RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN ADHERENCE TO A WELLNESS MODEL AND

Witmer, Sweeney, and Myers (1993) translated many of the

PERCEPTIONS OF PSYCHOLOGICAL WELL-BEING wellness theoretical and research concepts into a holistic

Theorists and college students seem to agree that wellness wellness model. Their original model consisted of 16 dimen-

is more than just a physical issue (Ardell, 1985; Benjamin, sions later categorized into five major life tasks based on

1994; Hettler, 1980, 1986; Sivik et al., 1992; Witmer & Adler’s theory of life tasks (Sweeney, 1989; Sweeney & Witmer,

Sweeney, 1992). For example, two separate surveys found 1991): (a) spirituality (a profound depth of appreciation for

that college students believed emotional and social dimen- life); (b) self-regulation (composite variable measuring effec-

sions of wellness were just as important as the physical di- tiveness in coping with self); (c) work, recreation, and leisure

mension (Archer, Probert, & Gage, 1987; Hybertson, Hulme, (ability to integrate a lifestyle); (d) friendship; and (e) love

Smith, & Holton, 1992). A situation therefore exists in (recognition of social interdependence). These five major

which institutions, theorists, and students believe in a ho- life tasks formed the basis of the independent variables of

listic wellness model while research continues to primarily this study.

emphasize only the physiological dimensions. Sivik et al. The developmental underpinnings of this model came

(1992) made a particularly strong call for filling this re- from theoretical constructs and empirical research in the

search gap with studies on the relationship between wellness fields of psychology, anthropology, sociology, religion, edu-

and other constructs. cation, and behavioral medicine (Witmer & Sweeney, 1992).

Da vid A. Hermon is an assistant professor in the Counseling Program at Marshall University, Huntington, West Virginia. Richard JJ.. Hazler is a professor of

David

counselor education at Ohio University, Athens. The authors thank Isabelle Antoniou for her help with this article. Correspondence regarding this article should

be sent to David A. Hermon, Counseling Program, Marshall University, Huntington, WV 25755 (e-mail: hermon@marshall.edu).

JOURNAL OF COUNSELING & DEVELOPMENT • SUMMER 1999 • VOLUME 77 339

Hermon and Hazler

A major strength of the model is that it includes a wider are made on 5-point Likert scales (strongly agree, agree, un-

range of factors contributing to holistic wellness than other decided, disagree, strongly disagree).

models and provides a measurement instrument to assess The following are sample items from each dimension of

these factors. Although some other models of wellness do the WEL. “Prayer, meditation, or individual spiritual study

incorporate multiple dimensions, the instruments used to is a regular part of my life” and “I have had an experience in

measure those models are physiologically biased (Cooper, which I felt a sense of oneness with nature, the universe, or

1990). The Wellness Evaluation of Lifestyle (WEL; Witmer a higher power” are items used to assess spirituality. “I am

et al., 1993) was selected for this study because its design appreciated by those with whom I work” and “I engage in a

specifically gives more equal assessment recognition to each leisure time activity in which I lose myself and feel like time

dimension of this model. stands still” are items used to assess work, recreation, and

A basic assumption regarding the value of any wellness leisure. “I get a sufficient amount of sleep” and “I usually

model is that those who adhere to the model would some- achieve the goals I set for myself” are items used to assess

how be noticeably better off than those who do not. One self-regulation. “I am comfortable with the social skills I have

measurement of this practical value is a person’s perception for interacting with others” and “I have at least one person

of the quality of their subjective life experience (happiness, with whom I can ‘be myself’ in bad moments as well as

sadness). Psychological well-being is an internal focused good” are items used to assess friendship. “I have at least one

method of attaching value to the quality of life and affec- intimate relationship that is secure and lasting” and “When

tive experience generally accepted as a scientific construct the going gets tough, my family or friends pull together to

with long-term (propensity or disposition) and short-term meet the challenge” are items used to assess love.

(mood) components similar in design to the trait/state dis- The WEL’s content validity was supported by results of

tinction in anxiety (Diener, 1984; Kozma, Stone, Stones, experts’ ratings of the items for appropriateness in measur-

Hannah, & McNeil, 1990). Short-term state and long-term ing their intended wellness dimensions (Witmer, 1995).

trait components of the Memorial University of Newfound- Witmer also found that the WEL effectively distinguished

land Scale of Happiness (MUNSH; Kozma & Stones, 1994) clinical samples (i.e., persons diagnosed with mental or

were used in this study to measure psychological well-being emotional disorders) from nonclinical samples.

and serve as dependent variables in this study. The WEL’s five dimensions have demonstrated solid in-

This study investigated the nature and strength of relation- ternal consistency and test–retest reliability (time interval

ships between college students’ adherence to a five-factor for test–retest was 2 weeks) based on a sample size of 552

(spirituality; work, recreation, and leisure; self-regulation; (mostly college students). Internal consistency reliabilities

friendship; and love) holistic wellness model and their self- of the individual scales ranged from .76 on the Work, Rec-

reported levels of psychological well-being. reation, and Leisure scale to .87 on the Love scale. Test–

retest reliability ranged from .82 on the Work, Recreation,

METHOD and Leisure scale to .87 on Self-Regulation (J. E. Myers,

Witmer, & Sweeney, 1995).

Sample Memorial University of Newfoundland Scale of Happiness

The sample consisted of 155 undergraduate students (94

(MUNSH). The MUNSH (Kozma & Stones, 1994) is a 24-

women and 61 men) at a large midwestern United States uni- item dichotomous response format instrument that mea-

versity. The traditional undergraduate college age group (ages sures both state (10 items) and trait (14 items) aspects of

psychological well-being. The MUNSH served as the mea-

18–23) accounted for 49% of the entire sample. The other

sure of the dependent variables in this study. Sample items

51% of the participants fell into a nontraditional age group

that measure the affective state dependent variable ask par-

(24–51) for undergraduate college students. The majority of

ticipants if, in the past month, they have felt “particularly

participants were single (71%), whereas 24% were married,

5% divorced, and less than 1% widowed. The cultural back- content with [their] life” and “depressed or very unhappy.”

ground of participants consisted of 113 (73%) Caucasians, 20 “Life is hard for me most of the time” and “the things I do

are as interesting to me as they ever were” are examples of

African Americans (13%), 18 Asian or Pacific Islanders (12%),

the general life experience, trait, dependent variable used

3 (2%) Hispanics, and 1 Native American.

in this study.

The MUNSH has been widely used in Canada and the

Variables

United States since 1975 with college students, adults, and

Wellness Evaluation of Lifestyle (WEL). The WEL (Witmer in gerontological studies. Kozma and Stones (1988) illus-

et al., 1993) was used to assess the five life tasks that were trated the effectiveness of the MUNSH in a study explor-

the independent variables in this study. The five tasks were ing the relationship between psychological well-being and

conceptualized from research in psychology (personality, social desirability in three age groups (21–40, 41–60, and

social, clinical, health, and developmental), anthropology, 61–80). The researchers found that the psychometric prop-

sociology, religion, behavioral medicine and education erties of the MUNSH are consistent across age groups. Stud-

(Witmer & Sweeney, 1992). The WEL consists of 114 state- ies have repeatedly shown the MUNSH to be a highly reli-

ments (both positively and negatively weighted). Responses able and effectively discriminating instrument when testing

340 JOURNAL OF COUNSELING & DEVELOPMENT • SUMMER 1999 • VOLUME 77

Wellness Adherence and Psychological Well-Being

clinical and nonclinical populations for both younger and TABLE 1

older adults (Kozma & Stones, 1988; Kozma, Stones, &

Kazarian, 1985; Stones & Kozma, 1994; Stones, Kozma, Summary of Simultaneous Regression Anaysis for

Hannah, & McKim, 1991). The MUNSH’s internal consis- Variables Predicting the State Dimension of

tency and reliability alphas with undergraduate college stu- Subjective Well-Being

dent subjects exceeded .85.

Covariate B SE B b

Procedure

Spirituality .01 .04 .03

Packets containing both the WEL and the MUNSH inven- Work, Recreation, and Leisure .20 .06 .27**

tories were distributed to 155 students enrolled in three Friendship .07 .09 .09

200-level communications courses and three 300-level or- Love .00 .07 .00

ganizational behavior courses. Identification numbers were Self-Regulation .06 .03 .28*

assigned to the instruments for the purpose of analyzing

the data. The students received verbal instructions with their Note. R 2 = .35.

instruments informing them that they are not required to *p < .05. **p < .01.

complete the instruments and may stop at any time with-

out penalty. The participants’ confidentiality and anonym-

ity were assured by the first author. All students completed

DISCUSSION

the instruments in full. This study revealed a significant relationship between re-

ported adherence to a holistic wellness model (as measured

RESULTS by engagement in wellness behaviors and agreement with

wellness ideology) and state (affective component) and trait

Data were analyzed through a multivariate regression analy- (quality of life) aspects of psychological well-being. The

sis using simultaneous entry of variables into the regression multivariate results indicated that in combination the five

equation of the five wellness predictor variables with the wellness variables are significantly related to the two psy-

two psychological well-being dependent variables. A key chological well-being variables. The nature of this signifi-

advantage of multivariate regression is protection from in- cant relationship was further examined by using betas from

flated errors of statistical inference from separate univariate univariate analyses on each dependent variable separately

analyses run for each dependent variable (Kalaian & to reveal which wellness tasks contributed most to the sig-

Raudenbush, 1996; Stevens, 1992). However, if the aspects nificance of this relationship.

of psychological well-being (state and trait) are not highly The variables self-regulation and work, recreation, and

correlated, this type of separation of one construct would leisure of the wellness model seem to be the best predic-

not fit this analysis. The two dependent variables state and tors of a college students’ psychological well-being (state

trait aspects of psychological well-being were highly corre- and trait). The strong relationship between self-regulation

lated at .71. Hence, this “bedifferentiation” of psychologi- and psychological well-being is supportive of Lightsey’s

cal well-being is appropriate for multivariate regression. (1996) comprehensive review of research studies that found

Multivariate analysis revealed a Wilk’s Lambda of .55 consistently positive relationships between generalized self-

(multivariate F = 10.42, p < .01, df = 10, 296). Therefore efficacy and psychological well-being. Apparently, students

the null hypothesis was rejected because a positive multi- in the current study who experienced success in tasks that

variate relationship did seem to exist, attributable to both

dependent variables’ relationship with the five predictors.

A histogram of the standardized residual confirmed that the TABLE 2

error was distributed normally, and no violations of assump-

tions for multivariate regression analysis were apparent. Summary of Simultaneous Regression Anaysis for

Table 1 reports the univariate findings of the five predictor Variables Predicting the Trait Dimension of

variables on the affective, state, component of psychological Subjective Well-Being

well-being (F = 16.26, p < .001, df = 5, 149). The simulta-

neous regression betas revealed that self-regulation (b = .28); Covariate B SE B b

and work, recreation, and leisure (b = .27) had the greatest

influence on the overall significance of this test. Spirituality .04 .05 .08

A significant relationship was found between the predic- Work, Recreation, and Leisure .16 .08 .17*

Friendship .26 .11 .26*

tor variables on the quality of life, trait, component of psy- Love –.05 .08 –.06

chological well-being (F = 19.84, p < .001, df = 5, 149). Self-Regulation .07 .03 .27*

Self-regulation (b = .27); friendship (b = .26); and work,

recreation and leisure (b = .17) contributed the most to the Note. R 2 = .40.

significance of this regression equation (see Table 2). *p < .05.

JOURNAL OF COUNSELING & DEVELOPMENT • SUMMER 1999 • VOLUME 77 341

Hermon and Hazler

constitute the self-regulation variable (managing stress, sense increasing satisfaction with personal and academic experi-

of worth, control, emotional responsiveness and manage- ences. Counseling centers, career counseling centers, and

ment, intellectual challenge, nutrition, exercise, sense of health services on campus can educate and increase stu-

gender, and cultural identity) were also the students who dents’ self-regulating behaviors through psycho-educational

felt positive about the way their lives were going. Experi- programs directed at these key components (e.g., managing

encing success in these self-regulating tasks seems to be as- stress, managing time, nutrition, and development of cul-

sociated with higher levels of psychological well-being. tural and gender awareness).

Strong relationships found between the work, recreation, Identification of vocational and avocational meaningful

and leisure variable and psychological well-being seemed pursuits is a challenge faced by every student. Colleges’

to support and expand previous findings that work satis- efforts to assist individuals in identifying and pursuing these

faction is a good predictor of longevity (Bortz, 1991; Pelletier, personally meaningful activities may increase satisfaction

1981). The WEL’s comprehensive definition of this vari- with experiences on campus. Career counseling and cam-

able is evaluated by the amount the person is engaging in pus programming efforts directed at student exploration of

meaningful activity, regardless of the absence or presence meaningful pursuits should aid the quality of student life

of monetary gain. on campus and satisfaction with personal and academic

Friendship reached statistical significance in the univariate experiences.

analysis with the trait dimension of psychological well-being Research on psychological well-being, happiness, and life

but not with the state dimension. This finding is consistent satisfaction quintupled in the 1980s (D. G. Myers & Diener,

with research that supports the importance of social relation- 1995). This area has clearly become a major factor in the

ships and quality of life. The fact that it did not reach statis- assessment of quality of student life (Pascarella & Terenzini,

tical significance on both dimensions may stem from the 1991) and can be used as a marker for university adminis-

dynamic nature of the state aspect of psychological well- trators evaluating the impact of efforts to improve student

being. The fact that one enjoys quality relationships with peers life. Holistic wellness activities that are initiated to improve

may not be critical to the fluctuating short-term affective state the experience of college students can be expected to result

experiences one has in life. in higher levels of student psychological well-being. Using

The nature of the constructs used in this study has been psychological well-being as a measure of success in this way

difficult to define and capture through paper-and-pencil adds an important formative dimension to the use of stu-

test items, which gives all such studies inherent limitations. dent retention rates. Although it is true that retention rates

The results also need to be generalized only so far as one offer clear numerical outcome data, they have little value

recognizes the population was volunteers only from six in the ongoing assessment of what needs to be changed,

classes at a large midwestern university. Finally, consider- when, how, and for whom. Once students have not returned

ation should be given to the fact that the measures were to school, they will show up in retention rate data, but there

given consecutively, which creates the possibility of over- is little that can be done to help them at that point. On the

lap in participant answers from one instrument to the other. other hand, psychological well-being can be used in forma-

Although all these limitations are common for this type of tive evaluations to identify a program’s weaknesses and

study, they deserve attention when considering outcomes strengths. These areas can then be given attention before

and additional research steps. individuals or groups of students might choose to leave

college.

IMPLICATION FOR COUNSELING IN HIGHER EDUCATION The utility of the holistic wellness model and psycho-

logical well-being can also be linked to evaluation, assess-

This analysis of relationships between wellness and psy- ment, and accreditation. The model is not simply a low pri-

chological well-being has repercussions for institutions of ority—do it if you have time—activity. It is a viable method

higher education that are increasingly pressed to find more for evaluating, assessing, and predicting outcomes in col-

effective ways of supporting students. Most current reten- lege counseling centers around the country (Howard,

tion goals are predicated on involving students in Lueger, Maling, & Martinovich, 1993). Kiracofe et al. (1994)

cocurricular activities to enhance their psychological expe- noted that for university and college counseling centers to

rience of the campus environment (Noel, Levitz, & Saluri, become accredited, they should provide “programming fo-

1985). The results of this study combined with previous cused on the developmental needs of students that maxi-

research should point college directors and campus leaders mizes their potential to benefit from an academic experi-

to additional actions and formative means for evaluating ence” (p. 39). The findings in this study underscore the

outcomes. importance of using proactive strategies that result in stu-

The importance of implementing activities that help stu- dents moving in a positive direction toward the less spo-

dents develop self-regulating behaviors gives specific direc- ken Jeffersonian ideals of striving for the ultimate goal—

tion to institutions of higher education. Activities that help happiness and well-being.

students gain control of stress levels, intellectual challenges, In summary, the results of this research demonstrate a

nutritional needs, and a sense of self-worth, including gen- significant positive relationship between adherence to a

der and cultural identities, seem to go a long way toward holistic wellness model and one psychological construct,

342 JOURNAL OF COUNSELING & DEVELOPMENT • SUMMER 1999 • VOLUME 77

Wellness Adherence and Psychological Well-Being

psychological well-being, and supports Sivik et al.’s (1992) & Yamada, K. T. (1994). Accreditation standards for university and col-

theoretical position that wellness goes beyond the current lege counseling centers. Journal of Counseling & Development, 73, 38–43.

Kozma, A., Stone, S., Stones, M. J., Hannah, T. E., & McNeil, K. (1990).

focus on physiology. Future studies should examine other Long- and short-term affective states in happiness: Model, paradigm

psychological constructs and their relationships with and experimental evidence. Social Indicators Research, 22, 119–138.

wellness adherence. These studies could incorporate physi- Kozma, A., & Stones, M. J. (1988). Social desirability in measures of subjec-

ological measures and observational measures in addition tive well-being: Age comparisons. Social Indicators Research, 20, 1–14.

to paper-and-pencil self-reports. Regardless of method of Kozma, A., & Stones, M. J. (1994). The Memorial University of Newfound-

land Scale of Happiness (MUNSH). Newfoundland, Canada: Memo-

assessing the effects of wellness adherence, psychological rial University.

constructs, although less obvious, may hold equal or possi- Kozma, A., & Stones, M. J., & Kazarian, S. (1985). The usefulness of the

bly even greater significance to our understanding of the MUNSH as a measure of well-being and psychopathology. Social Indi-

wellness of the whole person. cators Research, 17, 49–55.

Lightsey, O. R. (1996). What leads to wellness? The role of psychological

resources in well-being. The Counseling Psychologist, 24, 589–735.

REFERENCES Myers, D. G., & Diener, E. (1995) Who is happy? Psychological Science, 6, 10–19.

Myers, J. E., Witmer, J. M., & Sweeney, T. J. (1995). The Wellness Evalua-

Archer, J., Probert, B. S., & Gage, L. (1987). College students’ attitudes tion of Lifestyle: An instrument for assessing wellness. Unpublished manu-

toward wellness. Journal of College Student Development, 28, 311–317. script, University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

Ardell, D. B. (1985). The history and future of wellness. Health Values, Noel, L., Levitz, R. S., & Saluri, D. (1985). Increasing student retention.

9(6), 37–56. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Barth, G., & Johnson, G. A. (1983) A survey of wellness/healthy lifestyling Opatz, J. P. (1986). Stevens Point: A longstanding program for students at a

on college and university campuses. Journal of American College Health, midwestern university. American Journal of Health Promotion, 1, 60–67.

31, 226–227. Pascarella, E. T., & Terenzini, P. T. (1991). How college affects students. San

Benjamin, M. (1994). The quality of student life: Toward a coherent Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

conceptualization. Social Indicators Research, 31, 205–264. Pelletier, K. R. (1981). Longevity: Fulfilling our biological potential. New

Bortz, W. M. (1991). We live too short and die too long. New York: Bantam. York: Delacorte Press.

Cooper, S. E. (1990). Investigation of the Lifestyle Assessment Ques- Sivik, S. J., Butts, E. A., Moore, K. K., & Hyde, S. A. (1992). College and

tionnaire. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, university wellness programs: An assessment of current trends. NASPA

23, 83–87. Journal, 29, 136–142.

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 542–575. Stevens, J. (1992). Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences.

Hall, M. (1992). Wellness: A personal program for leaders. Campus Ac- Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

tivities Programming, 25, 44–51. Stones, M. J., & Kozma, A. (1994). The relationships of affect intensity

Hettler, B. (1980). Wellness promotion on a university campus. Family to happiness. Social Indicators Research, 31, 159–173.

and Community Health, 3, 77–95. Stones, M. J., & Kozma, A., Hannah, T. E., & McKim, W. A. (1991). The

Hettler, B. (1986). Strategies for wellness and recreation program devel- correlation coefficient and models of subjective well-being. Social In-

opment. In F. Leafgren (Ed.), New directions for student services (No. dicators Research, 24, 317–327.

34, pp. 19–32). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Sweeney, T. J. (1989). Adlerian counseling (3rd ed.). Muncie, IN: Acceler-

Howard, K. I., Lueger, R. J., Maling, M. S., & Martinovich, Z. (1993). A ated Development.

phase model of psychotherapy outcome: Causal mediation of change. Sweeney, T. J., & Witmer, J. M. (1991). Beyond social interest: Striving to-

Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 61, 678–685. ward optimum health and wellness. Individual Psychology, 47, 527–540.

Hybertson, D., Hulme, E., Smith, W. A., & Holton, M. A. (1992). Wellness in Witmer, J. M. (1995). Rationale and procedures in developing validity and

non-tradition-age students. Journal of College Student Development, 33, 50–55. reliability for the WEL inventory. Unpublished manuscript, Ohio Uni-

Johnson, K. L., & Wernig, S. R. (1986). Life directions: A comprehensive versity, Athens.

wellness program at a small college. In F. Leafgren (Ed.), New directions Witmer, J. M., & Sweeney, T. J. (1992). A holistic model for wellness and

for student services (No. 34, pp. 33–44). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. prevention over the life span. Journal of Counseling & Development,

Kalaian, H. A., & Raudenbush, S. W. (1996). A multivariate mixed linear 71, 140–148.

model for meta-analysis. Psychological Methods, 1, 227–235. Witmer, J. M., Sweeney, T. J., & Myers, J. E. (1993). Wellness Evaluation of

Kiracofe, N. M., Donn, P. A., Grant, C. O., Podolnick, E. E., Bingham, R. P., Lifestyle. Unpublished manuscript, Ohio University, Athens.

Bolland, H. R., Carney, C. G., Clementson, J., Gallagher, R. P., Grosz, R. Zimpfer, D. G. (1992). Psychosocial treatment of life-threatening disease:

D., Handy, L., Hansche, J. H., Mack, J. K., Sanz, D., Walker, L. J., A wellness model. Journal of Counseling & Development, 71, 203–209.

JOURNAL OF COUNSELING & DEVELOPMENT • SUMMER 1999 • VOLUME 77 343

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5796)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (589)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Lesson Plan 5Document2 pagesLesson Plan 5api-261801340No ratings yet

- Module Code FIN 7001 Module Title: Financial ManagementDocument9 pagesModule Code FIN 7001 Module Title: Financial ManagementTitinaBangawaNo ratings yet

- Context For LearningDocument2 pagesContext For LearningCoco BoothbyNo ratings yet

- Methods in Psychology WebpDocument37 pagesMethods in Psychology WebpxxxtrememohsinNo ratings yet

- PBL IduDocument7 pagesPBL Iduapi-312729994No ratings yet

- Using Conversation Analysis in The Second Language ClassroomDocument22 pagesUsing Conversation Analysis in The Second Language ClassroomlethanhtuhcmNo ratings yet

- Week 5Document3 pagesWeek 5Boyel SaludNo ratings yet

- PYPx Parent - Booklet - 2017Document7 pagesPYPx Parent - Booklet - 2017Vanessa SchachterNo ratings yet

- IdiolectDocument3 pagesIdiolectsadiqmazariNo ratings yet

- Public SpeakingDocument30 pagesPublic Speakinglogosunil100% (6)

- SkimmingDocument11 pagesSkimminghaziziNo ratings yet

- Healthy and Unhealthy Foods SIOP Lesson Plan: BackgroundDocument4 pagesHealthy and Unhealthy Foods SIOP Lesson Plan: BackgroundNasrea GogoNo ratings yet

- Scientific MethodDocument7 pagesScientific MethodMateen BashirNo ratings yet

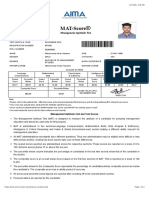

- MAT-Score: Management Aptitude TestDocument2 pagesMAT-Score: Management Aptitude TestMohammed AbrarNo ratings yet

- Programme Specification - Undergraduate Programmes Key FactsDocument11 pagesProgramme Specification - Undergraduate Programmes Key FactsSonia GalliNo ratings yet

- DLL - Science 4 - Q4 - W3Document3 pagesDLL - Science 4 - Q4 - W3Krystel Monica Manalo100% (1)

- Overcoming ProcrastinationDocument3 pagesOvercoming ProcrastinationDaniel Appropriate SheppardNo ratings yet

- Basketball Detaild Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesBasketball Detaild Lesson Planrom kero100% (2)

- Effectiveness of Concentration Enhancement Activity On Attention and Concentration Among School Age ChildrenDocument9 pagesEffectiveness of Concentration Enhancement Activity On Attention and Concentration Among School Age ChildrenEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Accomplishment Report in Brigada Pagbasa: Department of EducationDocument5 pagesAccomplishment Report in Brigada Pagbasa: Department of EducationChesee Ann SoperaNo ratings yet

- Validation of The Inclusion Skills Measurement Profile - Summary of Phase 1Document7 pagesValidation of The Inclusion Skills Measurement Profile - Summary of Phase 1carlosadmgoNo ratings yet

- Observation TableDocument4 pagesObservation Tableapi-302003110No ratings yet

- Course Syllabus - Streaming Media, Contemporary Society and Cultural MemoryDocument3 pagesCourse Syllabus - Streaming Media, Contemporary Society and Cultural MemorySofia CasabellaNo ratings yet

- Instructional Model of Self-Defense Lesson in Physical Education: A Systematic ReviewDocument4 pagesInstructional Model of Self-Defense Lesson in Physical Education: A Systematic ReviewTri WaluyoNo ratings yet

- Assure Lesson Plan PDFDocument4 pagesAssure Lesson Plan PDFapi-337261174No ratings yet

- Index and LogDocument4 pagesIndex and LogSabariah OsmanNo ratings yet

- QarDocument3 pagesQarSami RichmondNo ratings yet

- Statement of The Problem (GRADE12 TVL AUTO)Document4 pagesStatement of The Problem (GRADE12 TVL AUTO)Niño Gutierrez FloresNo ratings yet

- Motivational Interviewing PPT For ADNEPDocument43 pagesMotivational Interviewing PPT For ADNEPEd LeeNo ratings yet

- Communicating Effectively - The TalkDocument10 pagesCommunicating Effectively - The TalkCelarukeliru HarubiruNo ratings yet