Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Managing Pain in Geriatric Patients: Thomas A. Cavalieri, DO

Uploaded by

Claudia BuitragoOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Managing Pain in Geriatric Patients: Thomas A. Cavalieri, DO

Uploaded by

Claudia BuitragoCopyright:

Available Formats

sequences of undertreatment for pain

can have a negative impact on the health

and quality of life of the elderly, resulting

in depression, anxiety, social isolation,

cognitive impairment, immobility, and

Managing Pain sleep disturbances.4 Reasons that physi-

in Geriatric Patients cians often cite for inadequate pain con-

trol include lack of training, inappro-

Thomas A. Cavalieri, DO priate pain assessment, and reluctance

to prescribe opioids.2

As with other age groups, the

elderly have pain that can be classified

pathophysiologically as either nociceptive

or neuropathic in origin. Alternatively,

pain may be mixed, that is, having ori-

gins that are both nociceptive and neu-

ropathic. Nociceptive pain may be either

visceral or somatic and is due to stimu-

The elderly are often untreated or undertreated for pain. Barriers to effective lation of pain receptors. In the elderly,

management include challenges to proper assessment of pain; underreporting this stimulation may be the result of

by patients; atypical manifestations of pain in the elderly; a need for increased inflammation or musculoskeletal or

appreciation of the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes of aging; ischemic disorders. Patients with noci-

and misconceptions about tolerance and addiction to opioids. Physicians can ceptive pain are treated pharmacologi-

provide appropriate analgesia in geriatric patients by understanding different cally with both opioid and nonopioid

types of pain (nociceptive and neuropathic), and correctly using nonopioid, agents as well as nonpharmacologic

opioid, and adjuvant medications. interventions.1,3 Neuropathic pain results

Opioids have become more widely accepted for treating older adults who from a pathophysiologic disturbance of

have persistent pain, but such use requires physicians have an understanding either the peripheral or the central ner-

of prevention and management of side effects, opioid titration and withdrawal, vous system. In the elderly, common

and careful monitoring. Placebo use is unwarranted and unethical. Nonphar- examples include postherpetic neuralgia

macologic approaches to pain management are essential and include osteo- and diabetic neuropathy. Patients with

pathic manipulative treatment, cognitive behavioral therapy, exercise, and spir- neuropathic pain are less likely to

itual interventions. The holistic and interdisciplinary approach of osteopathic respond to agents used to treat patients

medicine offers an approach that can optimize effective pain management in with nociceptive pain such as pain due to

older adults. bone metastasis, and more likely to

respond to adjuvant agents such as anti-

J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2007;107(suppl 4):ES10-ES16. convulsants and antidepressants. Pain

of mixed origins may respond to admin-

istration of agents that treat for both noci-

ceptive and neuropathic pain.1,4

Because diseases often have an atyp-

more likely to have arthritis, bone and ical presentation in the elderly, it has

P ain is a common complaint of the

elderly. As the number of individ-

uals older than 65 years continues to

joint disorders, cancer, and other chronic

disorders associated with pain.1 Between

been speculated that pain perception

may be different in older adults.

rise, frailty and chronic diseases associ- 25% and 50% of community-dwelling Although pain sensitivity and tolerance

ated with pain will likely increase. elderly have important pain problems.2 across all ages varies,5 it is generally

Therefore, primary care physicians will Geriatric nursing home residents have accepted that such differences probably

face a significant challenge in pain man- an even higher prevalence of pain, do not have a significant clinical impact.

agement in older adults. The elderly are which is estimated to be between 45% As is the case in the use of any med-

and 80%.3 ications in the elderly, older adults are

The elderly are often either likely to have an increased risk of adverse

Address correspondence to Thomas A. Cavalieri, untreated or undertreated for pain. Con- reactions from pharmacologic agents

DO, FACOI, Interim Dean, Professor and Director,

New Jersey Institute for Successful Aging, Univer-

sity of Medicine and Dentistry of New

Jersey–School of Osteopathic Medicine, One Med-

ical Center Dr, Stratford, NJ 08084-1354. This continuing medical education publication is supported by an educational grant

Dr Cavalieri has no conflicts of interest. from Purdue Pharma LP.

E-mail: cavalita@umdnj.edu

ES10 • JAOA • Supplement 4 • Vol 107 • No 6 • June 2007 Cavalieri • Managing Pain in Geriatric Patients

Downloaded From: http://jaoa.org/ on 05/24/2017

Figure 1. Sample pain assessment scales for

use in the evaluation of pain in the care of the

elderly.

be described. Standardized geriatric

assessment tools to assess function, gait,

affect, and cognition should be used.8

Intensity should be assessed by using

one of several pain scales that have been

accepted for use in the elderly (Figure 1).

A verbally administered 0-through-

10 scale is an effective measurement of

pain intensity in most older adults. When

using this scale, physicians can ask

patients, “On a scale of zero to 10, with

zero meaning no pain and 10 meaning

the worst pain possible, how much pain

do you have now?” Some older adults,

particularly those with dementia, may

have difficulty using this scale. Other

tools such as a visual analog scale,

numerical scale, pain thermometer scale,

and pain faces scale can be helpful.1,4,9

Recently, evidence has established the

reliability and validity for the use of the

faces pain scale with older adults. 10

administered for analgesia.This propen- vital sign,” and therefore, physicians When possible, use of an interdisci-

sity is likely due to pharmacokinetic should regularly inquire about the pres- plinary team approach to assessment and

changes such as reduced renal excretion ence of pain in their elderly patients. Pain management of pain in the elderly is

and hepatic metabolism, as well as phar- can be assessed, even in those with advantageous. These strategies need to be

macodynamic changes that occur with dementia, using simple questions and sensitive to cultural and ethnic issues, as

age, such as an increased sensitivity to screening tools.6 well as to values and beliefs of patients

certain analgesics, particularly the opi- Assessing pain in the elderly is often and their families. Once etiologic factors

oids.2,4 In addition, polypharmacy is a associated with significant obstacles. are determined and therapy is initiated,

contributing factor for the increased inci- Older adults frequently fail to report pain a pain log or diary is appropriate to

dence of adverse drug reactions. because they may view that it is an assess effectiveness of treatment. Physi-

For pain management to be effec- expected part of old age or because they cians should encourage patients to record

tive in the elderly, physicians need to be are fearful that it may lead to more diag- such documentation on a daily basis.

skillful in pain assessment; capable of nostic testing or added medication.1 Regular reassessment by use of previ-

recognizing the importance of a holistic, Some patients may accept pain as pun- ously administered assessment scales is

interdisciplinary team approach to care; ishment for past actions.3 Rather than important and serves to modify therapy

and knowledgeable of both pharmaco- admitting to the presence of pain, the to assure an optimal response. Reassess-

logic and nonpharmacologic approaches elderly may use terms such as “aching” ment should include an evaluation of

to providing optimal analgesia.1,4 or “hurting.”7 Communication and cog- compliance and the presence of adverse

nitive disturbances are additional bar- drug effects11 (Figure 2).

Assessment of Pain in the Elderly riers to such assessment. Increased agi-

Effective assessment of pain in the elderly tation, changes in functional status, Pharmacologic Management

can be challenging. It requires an appre- altered gait, and social isolation may be of Pain in the Elderly

ciation that such discomfort may present signs of pain in patients with dementia.6 Even though adverse drug reactions in

atypically, particularly in the cognitively A comprehensive assessment the elderly are a significant risk, phar-

impaired. Because biologic markers are should include a careful history and macologic intervention for pain man-

not available, self-reporting is viewed as physical examination and diagnostic agement is the principal treatment

the best evidence for the presence of pain studies aimed at identifying the precise modality for pain. Along with consid-

and the optimal way to assess pain inten- etiology of pain. Characteristics such as ering age-associated changes of phar-

sity.4 Pain has been described as the “fifth intensity, frequency, and location should macokinetics and pharmacodynamics,

Cavalieri • Managing Pain in Geriatric Patients JAOA • Supplement 4 • Vol 107 • No 6 • June 2007 • ES11

Downloaded From: http://jaoa.org/ on 05/24/2017

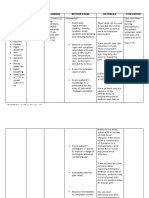

Figure 2. Suggestions for effective pain

assessment in the elderly.

Checklist

physicians must consider the likelihood 䡵 Consider pain as the first vital sign that is best measured by the

of drug-drug and drug-disease interac- patient.

tions. Despite these challenges, pain in 䡵 Ask about the presence of pain when examining an older person.

the elderly can be controlled but most 䡵 Console patient for atypical manifestations of pain in the elderly,

likely will require trials of various agents such as changes in function or gait, withdrawn or agitated

and careful titration of dosages. Because behavior, or increased confusion.

older patients may have increased sen- 䡵 Use standard geriatric assessment tools to evaluate function,

sitivity to analgesic medications, lesser affect, cognition, gait, and psychosocial issues.

dosages may be effective as compared 䡵 Rely on the input of caregivers, particularly in elderly patients with

with effective dosages in younger cognitive impairment and communication disorders.

patients.12 This difference is especially 䡵 Do a comprehensive pain assessment evaluating pain quality,

true when using opioid analgesics. intensity, and factors that exacerbate or relieve the pain.

Inasmuch as there is still a paucity of 䡵 Use standard pain scales such as a numerical scale, a pain

clinical trials that focus specifically on thermometer scale, or a visual analog scale.

geriatric patients, information regarding

䡵 Identify the etiology of pain in the elderly (keeping in mind that it

initial and titrating medication dosages may be multifactoral) by use of geriatric assessment tools, the

may not be available. Therefore, initial history and physical examination, and appropriate diagnostic tests.

doses should be lower and titration 䡵 Conduct a careful structural examination to identify regions of

should be slower in the elderly. In addi- somatic dysfunction.

tion, the general approach should be to

䡵 Monitor and measure presence of pain regularly by use of a pain

start with nonopioid medications for log or diary and by readministering the pain scales to assess the

treating patients with mild pain, efficacy of the intervention.

advancing to opioids for those with mod-

erate to severe pain. The selection of the

agent should be determined by targeting

the underlying pathophysiology if pos- erated in older patients provided that Opioid Analgesics

sible. For example, if pain is due pri- both renal and hepatic functions are Administration of opioid analgesics to

marily to inflammation, an anti-inflam- normal. 15 The daily dose of manage chronic noncancer pain in the

matory agent should be given. However, acetaminophen should not exceed 2 gm. elderly has become acceptable; these

if pain is predominantly neuropathic, an Long-term use of nonsteroidal anti- agents are effective in treating patients

anticonvulsant should be used. At times, inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), because with moderate to severe nociceptive pain.

combinations of analgesics may be of their association with gastrointestinal True addiction in the elderly is

required. bleeding and renal dysfunction, places uncommon, and the possibility of addic-

Selecting an agent likely to cause the the elderly at significant clinical risk. tion should not be used as justification for

fewest side effects is paramount. Once Although the likelihood of bleeding is undertreatment of the elderly for

dosing is initiated, it is essential that pri- lower with the concomitant use of miso- pain.1,18,19

mary care physicians regularly and care- prostol or a proton pump inhibitor, miso- Morphine sulfate and oxycodone

fully monitor for drug side effects and prostol is not well tolerated in the elderly. hydrochloride, now available in both

adverse events.1,4 The use of placebos is For this reason, a proton pump inhibitor short-acting and sustained-release prepa-

unethical, and placebos should not be may be an optimal choice.16,17 rations, are commonly used. Short-acting

used in pain management,13 a position Because of their association with a opioids can be used in treatment of

that the American Osteopathic Associa- lower incidence of gastrointestinal patients with intermittent pain, whereas

tion (AOA) endorses in the statement bleeding, selective cyclooxygenase-2 sustained-release opioids should be given

prepared by the AOA’s End-of-Life Care (COX-2) inhibitors (coxibs) have been for continuous pain (with short-acting

Committee,14 now the Council on Pallia- viewed as a safer alternative to the other preparations available for breakthrough

tive Care Issues. (See pages ES35-ES38.) NSAIDs; however, concern about their pain). The dosage of sustained-release

association with heart disease and stroke opioids can be titrated based on the fre-

Nonopioid Analgesics has dampened their acceptance and quency of use of the short-acting prepa-

Most mild or moderate pain in the resulted in the withdrawal of rofecoxib ration. For patients who may not be able

elderly is of musculoskeletal origin and (Vioxx) from the market.17 Prolonged use to take oral preparations periodically,

responds well to acetaminophen given of NSAIDs in the elderly should be opioids are available as parenteral, sub-

around-the-clock. This agent is well tol- avoided whenever possible. lingual, suppository (oxymorphone

ES12 • JAOA • Supplement 4 • Vol 107 • No 6 • June 2007 Cavalieri • Managing Pain in Geriatric Patients

Downloaded From: http://jaoa.org/ on 05/24/2017

Figure 3. Suggestions for effective pharma-

cologic pain management in the elderly.

Checklist

䡵 Consider age-related alterations of drug metabolism resulting in to gastric hypomotility, patients need to

increased drug sensitivity and adverse reactions while using take stool softeners for as long as they

pharmacologic interventions for pain management in the are on opioid therapy. Chewing or

elderly.

crushing sustained-release opioids must

䡵 When considering pharmacologic interventions, keep in mind be avoided as doing so can cause rapid

that pain is often unrecognized in the elderly and the elderly are absorption of the entire dose resulting

often undertreated for pain.

in overdosing.1

䡵 Start with the lowest possible dose, and proceed slowly to Certain opioids should be avoided

increase dose.

in elderly patients when possible.

䡵 Consider acetaminophen as the drug of choice for mild to Propoxyphene is thought to be no more

moderate musculoskeletal pain. effective than aspirin or acetaminophen,

䡵 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use should be avoided as but it is associated with ataxia, dizziness,

much as possible for the treatment of elderly patients who have and neuroexcitatory effects due to drug

persistent pain.

accumulation.22 Meperidine hydrochlo-

䡵 Consider opioid analgesics for moderate to severe nociceptive ride should not be used because of the

pain in the elderly. accumulation of a nephrotoxic metabo-

䡵 Use sustained-release opioids for continuous pain and short- lite. Methadone hydrochloride should

acting preparations for breakthrough or episodic pain. also be avoided in the elderly because it

䡵 Titrate opioid dose based on use of medications for has a long and variable half-life, which

breakthrough pain. makes titration difficult. In addition, the

䡵 Prevent constipation with opioid use by recommending a analgesic action is shorter than that of

prophylactic bowel regimen. respiratory depression1 so patients whose

䡵 Anticipate and manage opioid side effects such as sedation, methadone dosage is too low may

confusion, and nausea until tolerance develops. increase their daily amount, which

䡵 Avoid the use of opioids that have frequent adverse reactions in increases the risk of death from respira-

the elderly, such as propoxyphene, meperidine hydrochloride, tory depression.

and methadone hydrochloride. Transdermal fentanyl, contraindi-

䡵 Closely monitor patients on long-term analgesic therapy for side cated in opioid-naïve patients, should

effects and drug-drug and drug-disease interactions. also be used with extreme caution in the

䡵 Consider adjuvant analgesics such as the anticonvulsant elderly. It has a variable absorption rate

gabapentin for the management of neuropathic pain. in older adults and a long residual effect

even when the patch is removed.

Tramadol hydrochloride, an anal-

gesic that has some opioid properties

hydrochloride), and transdermal (eg, fen- could propel the patient on long-term and is used for mild to moderate pain,

tanyl patch) products.20 opioid therapy into withdrawal. It is should be used with caution in the

Physicians should anticipate, pre- advisable that patients take a mainte- elderly because it may cause dizziness

vent, and manage side effects. They nance dose for several days before they and reduce the seizure threshold.23

should initiate prevention of constipa- resume driving.

tion through the use of stool softeners Antiemetics such as prochlorper- Adjuvant Medications

and other prophylactic bowel regimens azine or metoclopramide may be needed Adjuvant medications are frequently

whenever opioid therapy is used in the early on with the initiation of opioid used to treat elderly patients with chronic

elderly. When opioid therapy is initiated, therapy. Falls, dizziness, and gait dis- pain disorders. Many were developed

sedation and delirium are commonplace turbances are not uncommon; therefore, for purposes other than analgesic use but

until tolerance develops. Although res- preventive precautions are often recom- have been shown to be effective in the

piratory depression occurs uncommonly, mended, such as the use of an assistive management of certain pain syn-

tolerance develops rapidly. If needed, device. Eventually, for most patients, the dromes.24 Anticonvulsants, steroids, top-

naloxone hydrochloride could be used analgesic effect of opioids is preserved ical local anesthetics, and antidepressants

for profound respiratory depression and while tolerance develops to most side are such agents that may be used alone

sedation; care must be taken when effects (eg, respiratory depression, seda- or in combination with nonopioid or

reversing this adverse effect since an tion, nausea, and vomiting).1,4,11,21 How- opioid analgesics.

antagonist action that is too powerful ever, because tolerance does not develop Adjuvant medications are particu-

Cavalieri • Managing Pain in Geriatric Patients JAOA • Supplement 4 • Vol 107 • No 6 • June 2007 • ES13

Downloaded From: http://jaoa.org/ on 05/24/2017

Figure 4. Suggestions for effective non-

pharmacologic pain management in the

elderly. Checklist

䡵 Realize the importance of nonpharmacologic approaches to pain

larly useful in managing neuropathic management, both alone or in combination with analgesics, as a

means of avoiding the high incidence of adverse drug reactions in

pain.4 Although tricyclic antidepressants the elderly.

such as amitriptyline hydrochloride and

䡵 Recognize the importance and efficacy of patient and caregiver

nortriptyline hydrochloride have been

education in the management of pain, enabling the patient and

used to treat patients with this disorder, caregiver to understand the goals of therapy, method of pain

anticonvulsants such as gabapentin and assessment, appropriate use of analgesics, and self-help techniques.

carbamazepine are thought to be more 䡵 Incorporate the appropriate use of osteopathic manipulative

effective.25 In addition, amitriptyline has treatment to reduce pain and enhance function.

significant anticholinergic effects that can

䡵 Consider the role of cognitive-behavioral therapy as a means of

be problematic for geriatric patients. education and for enhancing coping skills and prevention of pain in

Gabapentin seems to be more effective the elderly.

and better tolerated in older adults. How- 䡵 Recognize the role of exercise targeted to the individual as a means

ever, the recently available anticonvul- of pain management to maintain and enhance functioning and

sant pregabalin is effective and easier to avoid deconditioning.

tolerate than gabapentin.26 䡵 Consider the role of psychiatry or occupational therapy to avoid

Selective serotonin-reuptake dysfunction, improve muscle strength, and aid in identifying the

inhibitor (SSRI) drugs are effective and appropriate use of heat, cold, and massage therapy in the

well tolerated when used for treating management of pain.

patients with depression, but their effi- 䡵 Recognize that some older patients may be helped by other

cacy in pain management is not docu- nonpharmacologic therapy such as acupuncture and transcutaneous

mented.1 More recently,however, sero- electrical nerve stimulation.

tonin norepinephrine-reuptake inhibitor 䡵 Appreciate the spiritual aspects of pain in the elderly and provide

(SNRI) in duloxetine, has been shown to counseling or refer to a member of the clergy if appropriate.

be effective for the treatment of patients

with neuropathic pain and seems to be

well tolerated in the elderly.27

When selecting an adjuvant agent use is increasing, particularly when such Osteopathic Manipulative

to treat the elderly for pain, physicians methods are used in conjunction with Treatment

should: (1) prescribe medications with drug therapy.15,28,29 Clearly, osteopathic manipulative treat-

the lowest side effect profile for older ment is effective in the management of

adults; (2) titrate the drug slowly; and Patient and Caregiver Education chronic pain.31,32 The type of techniques

(3) assess patients carefully for both effec- Patient and caregiver education is essen- and the extent of intervention must be

tiveness and the presence of adverse tial as a mechanism to improve pain tailored to the individual.4 The holistic

effects1,2,4 (Figure 3). management in the elderly. Patient edu- approach to care, central to the practice of

cation programs typically include infor- osteopathic medicine, supports the need

Nonpharmacologic Pain mation about the nature of pain, assess- for an interdisciplinary team approach

Management in the Elderly ment instruments, medication use, and to the care of elderly patients with chronic

Although most elderly patients require nonpharmacologic treatment modalities, pain.31-33

pharmacologic intervention to manage as well as coping strategies. Both one-

pain, nonpharmacologic approaches may on-one as well as group programs can Complementary and Alternative

have an added benefit and should be be effective. Caregiver education is espe- Modes of Therapy

routinely considered. This aspect is par- cially important in caring for the Evidence exists that participation in reg-

ticularly important in older adults elderly.28,29 ular physical activity can reduce pain

because procedures that avoid drugs and enhance functional capacity of older

have a low frequency of adverse reac- Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy adults with persistent pain.34 Addition-

tions compared with pharmacologic Cognitive-behavioral therapy using a ally, an assessment by a physiatrist, phys-

approaches. structured systemic approach to teaching ical therapist, or occupational therapist

Although many nonpharmacologic coping skills has been shown to be effec- may be helpful for recommending ways

methods lack rigorous, evidence-based tive. It requires a trained therapist con- to improve muscle strength and avoid

studies to document their efficacy, the ducting 6 to 10 sessions.1,30 dysfunction and also for identifying the

body of knowledge to substantiate their appropriate use of heat, cold, or massage

ES14 • JAOA • Supplement 4 • Vol 107 • No 6 • June 2007 Cavalieri • Managing Pain in Geriatric Patients

Downloaded From: http://jaoa.org/ on 05/24/2017

Figure 5. Ten principles for effective pain

management in the elderly.

䡵 The use of osteopathic manipulative treatment and the holistic

approach of osteopathic medicine in the management of pain in the The most useful approach in this patient

elderly optimizes care of older patients. would be the pain faces scale, which, as pre-

䡵 The use of placebos in the management of pain in the elderly is viously noted, has been found to be reliable

unacceptable, unethical, and unjustified. and valid for assessing pain in older adults.10

䡵 Regularly inquire about the presence of pain in the elderly and Given the patient’s mental status, her

consider pain as the “fifth vital sign.” responses to the other pain assessment

䡵 Keep in mind that pain is undertreated, underrecognized, and options—open-ended questions, numeric

frequently presents atypically in older adults. scale, pain thermometer scale, and use of a

䡵 An interdisciplinary, multidimensional approach to assessment, pain diary—would not provide an accurate

evaluating the physical, structural, functional, and psychosocial aspects indication of the severity of her pain, which is

of pain, using standard assessment tools is important to appropriate most likely of nociceptive and neuropathic

evaluation. origin.

䡵 When prescribing medications, be aware of altered drug metabolism An attempt to reintroduce long-acting

with aging and the presence of polypharmacy; when selecting opioids after careful titration resulted in only

pharmacologic interventions, be aware of the increased frequency of

minimal improvement in this patient’s pain.

adverse drug reactions in the elderly.

Therefore, pregabalin was added because of the

䡵 Acetaminophen is an effective analgesic for mild to moderate neuropathic origin of the pain. This addition

musculoskeletal pain in the geriatric population and should be

considered whenever possible in lieu of medications with higher side was supported by the nature of the pain and

effect profiles; long-term NSAID use should be avoided if possible. the lack of pain relief through the reintro-

duction of long-acting opioids.

䡵 Opioid analgesics are effective for chronic pain in the elderly; fear of

addiction is exaggerated; side effects must be anticipated and

prevented; and skill at dosage initiation, route of administration, and Comment

titration is important. The elderly are frequently untreated or

䡵 Adjuvant medications such as anticonvulsants and antidepressants are undertreated for pain because of barriers

effective in treating elderly patients for neuropathic pain. to recognition, assessment, and man-

䡵 Nonpharmacologic approaches such as patient education, cognitive- agement in such patients. A greater

behavioral therapy, physical therapy, and spiritual interventions understanding of clinical manifestations

should be included in pain management in older adults. of pain, improved methods of assess-

ment, and use of both pharmacologic

and nonpharmacologic interventions can

result in more favorable outcomes in the

therapy. Both acupuncture and transcu- which is representive of problems in pain treatment of older adults for pain. Osteo-

taneous electrical nerve stimulation have assessment and treatment decisions. pathic physicians are uniquely equipped

been used with modest success for man- for optimal care of elderly patients with

agement of persistent pain in older Case Presentation persistent pain by incorporating bene-

adults.4 Mrs Jones, an 80-year-old woman, has a his- fits of manipulative treatment and using

tory of Alzheimer disease in the middle stages holistic and team approaches of osteo-

Spirituality and metastatic breast carcinoma to bone. She pathic medicine (Figure 5).

Last, for many patients, there exists a has resided in a nursing home for the past

spiritual dimension to persistent pain; year. Lately, she has had increased agitation References

evidence exists to support spirituality as and confusion. She was recently treated with 1. AGS Panel on Persistent Pain in Older Persons.

The management of persistent pain in older per-

being helpful to some who are suffering haloperidol because of the confusion; this med- sons. J Am Geriatr Soc>.2002;50(6 suppl):S205-S224.

from persistent pain.35 Keeping in mind ication did not improve her mental status.

2. Gloth FM III. Pain management in older adults:

the basic osteopathic tenet, “A person is Upon questioning, she complained of pain prevention and treatment. J Am Geriatr

the product of dynamic interaction and pointed to her back and left leg. Mrs Soc.2001;49:188-199.

between body, mind, and spirit,” appro- Jones had been treated with opioid analgesics

3. Ferrell BA, Ferrell BR, Osterweil D. Pain in the

priate counseling or referral to clergy initially as needed, then around-the-clock, nursing home. J Am Geriatr Soc.1990;38:409-414.

may be helpful in the management of without any improvement. Her current med-

4. Cavalieri TA. Pain management in the elderly.

pain4 (Figure 4). ications include aspirin, 81 mg/d; donepezil J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2002;102:481-485.

Primary care physicians often are hydrochloride,10 mg/d, haloperidol, 0.5 mg

5. Gibson SJ, Helme RD. Age-related differences in

confronted by elderly patients such as twice a day; and memantine hydrochloride, pain perception and report. Clin Geriatr Med.

the one in the following case scenario, 10 mg twice a day. 2001;17: 433-456, v-v1.

Cavalieri • Managing Pain in Geriatric Patients JAOA • Supplement 4 • Vol 107 • No 6 • June 2007 • ES15

Downloaded From: http://jaoa.org/ on 05/24/2017

6. Herr KA, Garand L. Assessment and measure- 16. Greenberger NJ. Update in gastroenterology. 27. Treatment Options: A Guide for People Living

ment of pain in older adults. Clin Geriatr Med. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:827-834. with Pain. American Pain Foundation Web site.

2001;17: 457-478, vi. Available at: http://www.painfoundation.org.

17. Topol EJ. Failing the public health-rofecoxib, Accessed March 20, 2007

7. Miller J, Neelon V, Dalton J, Ng’andu N, Bailey Merck, and the FDA. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1707-

D Jr, Layman E, et al. The assessment of discomfort 1709. 28. Ferrell BR, Rhiner M, Ferrell BA. Development

in elderly confused patients: a preliminary study. J and implementation of a pain education program.

Neurosci Nurs.1996;28:175-182. 18. Forman WB. Opioid analgesic drugs in the Cancer.1993;72(11 suppl):3426-3432.

elderly. Clin Geriatr Med. 1996;12:489-500.

8. Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older 29. Mazzuca SA, Brandt KD, Katz BP, Chambers M,

people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities 19. Cavalieri TA. Pain management at the end of Byrd D, Hanna M. Effects of self-care education

of daily living. Gerontologist.1969;9:179-186. life. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1999;99(6 suppl): S16- on health status of inner-city patients with

S21. osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Rheum.1997;40:

9. Parmelee PA. Pain in cognitively impaired older 1466-1474.

persons. Clin Geriatr Med.1996;12:473-478. 20. Leipzig RM. Cumming RG, Tinetti ME. Drugs

and falls in older people: a systematic review and 30. Keefe FJ, Beaupre PM, Weiner DK, Siegler IC.

10. Kim EJ, Buschmann M.F. Preliability and validity meta-analysis: II. Cardiac and analgesic drugs. J Am Pain in older adults: a cognitive-behavioral per-

of the Faces Pain Scale with older adults. Interna- Geriatr Soc.1999;47:40-50. spective. In: Ferrell BR, Ferrell BA, eds. Pain in the

tional Journal of Nursing Studies. 2006;43 (447- Elderly. Seattle, Wash: IASP Press; 1996 :11-19.

456). 21. Miller RR, Feingold A, Paxinos J. Propoxyphene

hydrochloride. A critical review. JAMA 1970; 213: 31. Jerome JA. Pain management. In: Ward RC,

11. Ferrell BA, ed. Pain management in the elderly. 996-1006. executive ed. Foundations for Osteopathic

Clin Geriatr Med. 2001;17:417-615. Medicine. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams &

22. Schnitzer TJ. Tramadol: role in the manage- Wilkins; 2003:171-185.

12. Bellville JW, Forrest WH Jr, Miller E, Brown ment of pain in elderly patients. Home Health Care

BW Jr. Influence of age on pain relief from anal- Consult.2000;7:27-34. 32. Ehrenfeucter WC, Heilig D, Nicholas AS. Soft

gesics. A study of postoperative patients. JAMA. tissue techniques in pain management. In: Ward RC,

1971;217:1835-1841. 23. Lipman AG. Analgesic drugs for neuropathic executive ed. Foundations for Osteopathic

and sympathetically maintained pain. Clin Geriatr Medicine. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams &

13. Bradley JD, Brandt KD, Katz BP, Kalasinski LA, Med.1996;12:501-515. Wilkins; 2003:212-226.

Ryan SL. Comparison of antiinflammatory dose of

ibuprofen, an analgesic dose of ibuprofen, and 24. Ross EL. The evolving role of antiepileptic 33. Nicholas AS, Bezilla TA, Jones R. Osteopathic

acetaminophen in the treatment of patients with drugs in treating neuropathic pain. Neurology. manipulation for management of pain. J Am

osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med.1991; 2000;55(5 suppl):S41-S46; discussion S54-S58. Osteopath Assoc. 1999;99(6 suppl):S5-S10.

325:87 -91.

25. Jacox A, Carr DB, Payne R, Berde CB, Breitbart 34. Ferrell BA, Josephson KR, Pollan AM, Loy S,

14. Nichols KJ, Galluzzi KE, Bates B, Husted BA, W, Cain JM, et al. Management of Cancer Pain. Ferrell BR. A randomized trial of walking versus

Leleszi JP, Simon K, et al for the American Osteo- Clinical Practice Guideline No. 9. Rockville, Md: physical methods for chronic pain management.

pathic Association End-of-Life Care Committee. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, US Aging (Milano). 1997;9(1-2):99-105.

AOA’s position against use of placebos for pain Department of Health and Human Services, Public

management in end-of-life care. J Am Osteopath Health Service; AHCPR Publication No. 94-0592. 35. Sundbloom DM, Haikonen S, Niemi-Pynttari J,

Assoc.2005;:105(suppl 1):S2-S5. March 1994. Tigerstedt I. Effect of spiritual healing on chronic

idiopathic pain: a medical and psychological study.

15. Stucki G, Johannesson M, Liang MH. Use of 26. Pauson D, ed. Triple i Geriatrics Prescribing Clin J Pain.1994;10:296-302.

misoprostol in the elderly: is the expense justified? Guide. Carlstadt, NJ: Triple i Division, Medimedia

Drugs Aging.1996;8:84-88. USA; Spring/Summer 2007:176, 198.

ES16 • JAOA • Supplement 4 • Vol 107 • No 6 • June 2007 Cavalieri • Managing Pain in Geriatric Patients

Downloaded From: http://jaoa.org/ on 05/24/2017

You might also like

- Nursing Diagnosis Nursing Intervention Rationale: Prioritized Nursing Problem For PharyngitisDocument6 pagesNursing Diagnosis Nursing Intervention Rationale: Prioritized Nursing Problem For PharyngitisJinaan MahmudNo ratings yet

- The Art of Holistic Pain Management: A Practical HandbookFrom EverandThe Art of Holistic Pain Management: A Practical HandbookNo ratings yet

- Neuropathic Pain: Mechanisms and Their Clinical ImplicationsDocument12 pagesNeuropathic Pain: Mechanisms and Their Clinical Implicationsfahri azwarNo ratings yet

- Nursing Diagnosis Nursing Intervention Rationale: Prioritized Nursing Problem For InfluenzaDocument6 pagesNursing Diagnosis Nursing Intervention Rationale: Prioritized Nursing Problem For InfluenzaJinaan MahmudNo ratings yet

- The Management of Chronic Pain in Older PersonsDocument17 pagesThe Management of Chronic Pain in Older PersonsyurikhanNo ratings yet

- Antidepressants and Antiepileptic Drugs For Chronic Non-Cancer PainDocument8 pagesAntidepressants and Antiepileptic Drugs For Chronic Non-Cancer PainSamer FarhanNo ratings yet

- Midterms GeriaDocument18 pagesMidterms GeriaGiselle Estoquia100% (1)

- Pain and Analgesia: by Gilles L. Fraser, Pharm.D., MCCM and David J. Gagnon, Pharm.D., BCCCPDocument19 pagesPain and Analgesia: by Gilles L. Fraser, Pharm.D., MCCM and David J. Gagnon, Pharm.D., BCCCPyouffa hanna elt misykahNo ratings yet

- Mind Body TherapiesDocument1 pageMind Body TherapiesFenny KusumasariNo ratings yet

- Pain ManagementDocument7 pagesPain ManagementHazel ZullaNo ratings yet

- April Focus GibsonDocument6 pagesApril Focus GibsonMashael SulimanNo ratings yet

- D. Nursing Care Plan: Chronic Pain Related ToDocument2 pagesD. Nursing Care Plan: Chronic Pain Related ToReinette LastrillaNo ratings yet

- Assessment and Treatment of Pain in Pediatric PatientsDocument10 pagesAssessment and Treatment of Pain in Pediatric PatientsAnonymous zd0Bwj4nNo ratings yet

- Chronic Stress Cortisol Dysfunction and PainDocument10 pagesChronic Stress Cortisol Dysfunction and PainMomna KashifNo ratings yet

- Ananad2 PDFDocument8 pagesAnanad2 PDFmustafasacarNo ratings yet

- Austprescr 41 60Document4 pagesAustprescr 41 60Ussy TsnnnNo ratings yet

- Pain Management For ElderlyDocument14 pagesPain Management For ElderlyandikaisnaeniNo ratings yet

- Pain Management in Palliative Care - Art or ScienceDocument6 pagesPain Management in Palliative Care - Art or ScienceArmando José MaldonadoNo ratings yet

- Clinical Review - FullDocument5 pagesClinical Review - FullBenvenuto AxelNo ratings yet

- Nonnarcotic Methods of Pain ManagementDocument1 pageNonnarcotic Methods of Pain ManagementVanessa PasikNo ratings yet

- Neuropathic PainDocument19 pagesNeuropathic PainBush HsiehNo ratings yet

- Physical Therapy Modalities and Rehabilitation Techniques in The Treatment of Neuropathic Pain 2329 9096.1000124Document4 pagesPhysical Therapy Modalities and Rehabilitation Techniques in The Treatment of Neuropathic Pain 2329 9096.1000124Mayah SNo ratings yet

- Ncm116 Lesson2 Rle Pain ManagementDocument4 pagesNcm116 Lesson2 Rle Pain ManagementMilcah NuylesNo ratings yet

- Assessment Diagnosis Planning Intervention Rationale EvaluationDocument5 pagesAssessment Diagnosis Planning Intervention Rationale EvaluationArian May MarcosNo ratings yet

- Musculoskeletal Pain and Exercise-Challenging Existing Paradigms and Introducing NewDocument6 pagesMusculoskeletal Pain and Exercise-Challenging Existing Paradigms and Introducing NewCelia CaballeroNo ratings yet

- Emphasis On Non-Pharmacologic Aspect: Key Principles: o Gate Control & Neuromatrix Theory of PainDocument3 pagesEmphasis On Non-Pharmacologic Aspect: Key Principles: o Gate Control & Neuromatrix Theory of PainJudy Ignacio EclarinoNo ratings yet

- Psychological Pain Interventions 2014Document9 pagesPsychological Pain Interventions 2014MilenaSpasovskaNo ratings yet

- Individual Difference Variables and The Effects of Progressive Muscle Relaxation and Analgesic Imagery Interventions On Cancer PainDocument12 pagesIndividual Difference Variables and The Effects of Progressive Muscle Relaxation and Analgesic Imagery Interventions On Cancer PainUswatun HasanahNo ratings yet

- Know Pain, Know Gain? A Perspective On Pain Neuroscience Education in Physical TherapyDocument4 pagesKnow Pain, Know Gain? A Perspective On Pain Neuroscience Education in Physical TherapySamuelNo ratings yet

- Greene, S. A. Chronic Pain Pathophysiology and Treatment Implications. Topics in Companion Animal Medicine, v.25, n.1, p.5-9. 2010 PDFDocument5 pagesGreene, S. A. Chronic Pain Pathophysiology and Treatment Implications. Topics in Companion Animal Medicine, v.25, n.1, p.5-9. 2010 PDFFran WermannNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Patients With Arthritis-Related Pain: Nicholas A. Deangelo, Do Vitaly Gordin, MDDocument4 pagesTreatment of Patients With Arthritis-Related Pain: Nicholas A. Deangelo, Do Vitaly Gordin, MDHapsyah MarniNo ratings yet

- Goals and Outcomes: Acute Pain Is Characterized by The Following Signs and SymptomsDocument5 pagesGoals and Outcomes: Acute Pain Is Characterized by The Following Signs and SymptomsCyril Jane Caanyagan AcutNo ratings yet

- Tutorial Pain Management ChogaDocument26 pagesTutorial Pain Management ChogaChoga ArlandoNo ratings yet

- Epidemiology and Definition: o Most Common Locations: o Acute PainDocument4 pagesEpidemiology and Definition: o Most Common Locations: o Acute PainJudy Ignacio EclarinoNo ratings yet

- MOD014 Nyeri KankerDocument23 pagesMOD014 Nyeri KankerMien Dwi CahyaniNo ratings yet

- Lewis: Medical-Surgical Nursing, 10 Edition: Pain Key Points Magnitude of Pain ProblemDocument7 pagesLewis: Medical-Surgical Nursing, 10 Edition: Pain Key Points Magnitude of Pain ProblemAmber Nicole HubbardNo ratings yet

- PainDocument38 pagesPainUsama FiazNo ratings yet

- Australian Prescriber PDFDocument4 pagesAustralian Prescriber PDFNadaSalsabilaNo ratings yet

- 907 FullDocument6 pages907 FullMilton Ricardo de Medeiros FernandesNo ratings yet

- Can We Conquer Pain?: ReviewDocument6 pagesCan We Conquer Pain?: Reviewfernandoribeirojr98No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0007091217329677 MainDocument5 pages1 s2.0 S0007091217329677 MainAndy OrtizNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Nursing Practice #16Document8 pagesFundamentals of Nursing Practice #16AS DeltaNo ratings yet

- Advances in Neuropathic Pain: Diagnosis, Mechanisms, and Treatment RecommendationsDocument11 pagesAdvances in Neuropathic Pain: Diagnosis, Mechanisms, and Treatment Recommendationsgamesh waran gantaNo ratings yet

- An Update On The Pharmacologic Management And.3Document5 pagesAn Update On The Pharmacologic Management And.3Amany AlnajjarNo ratings yet

- Pain Management Literature Review Poster by Megan Jones Kelsey Rising Cheyenne Singleton and Lauren SyersakDocument1 pagePain Management Literature Review Poster by Megan Jones Kelsey Rising Cheyenne Singleton and Lauren Syersakapi-663972838No ratings yet

- Appendicitis - NCPDocument5 pagesAppendicitis - NCPEarl Joseph Deza100% (1)

- Appendicitis NCPDocument5 pagesAppendicitis NCPEarl Joseph DezaNo ratings yet

- Anti Nyeri Saraf The Pharmacological TherapyDocument12 pagesAnti Nyeri Saraf The Pharmacological TherapyTiara Renita LestariNo ratings yet

- Pain Management: in The Critically IllDocument37 pagesPain Management: in The Critically Illstawberry shortcakeNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care Plan: Assessment Diagnosis Planning Intervention Rationale EvaluationDocument1 pageNursing Care Plan: Assessment Diagnosis Planning Intervention Rationale EvaluationJoselyn M. LachicaNo ratings yet

- Pain PDFDocument15 pagesPain PDFmahmoud EltoukhyNo ratings yet

- PainDocument7 pagesPainVALERIANO TRISHANo ratings yet

- Ncm-212-Pain Reliever and Anti-Inflammatory DrugsDocument8 pagesNcm-212-Pain Reliever and Anti-Inflammatory Drugskristine caminNo ratings yet

- Kohns 2020Document10 pagesKohns 2020Marco Antonio Morales OsorioNo ratings yet

- Depression and Chronic Pain PDFDocument8 pagesDepression and Chronic Pain PDFracquela_3No ratings yet

- 907 FullDocument6 pages907 FullItai IzhakNo ratings yet

- Assessment and Treathment of Pain in Pediatric PatientsDocument11 pagesAssessment and Treathment of Pain in Pediatric Patientsfuka priesleyNo ratings yet

- Molecules: Transdermal and Topical Drug Administration in The Treatment of PainDocument16 pagesMolecules: Transdermal and Topical Drug Administration in The Treatment of PainAbraham GomezNo ratings yet

- AnalgesiaDocument6 pagesAnalgesiajoyceereiisNo ratings yet

- Side Effects of NSAIDsDocument8 pagesSide Effects of NSAIDsAlmas PrawotoNo ratings yet

- Aspirin Drug StudyDocument8 pagesAspirin Drug StudyAngie Mandeoya0% (1)

- Cyclooxygenase-2 OverexpressionDocument7 pagesCyclooxygenase-2 OverexpressionGessyca JeyNo ratings yet

- The Ocular Surface: Sarah E. Kenny, Cooper B. Tye, Daniel A. Johnson, Ahmad Kheirkhah TDocument7 pagesThe Ocular Surface: Sarah E. Kenny, Cooper B. Tye, Daniel A. Johnson, Ahmad Kheirkhah TSaaraAlleyahAlAnaziNo ratings yet

- Sign 155 Migraine 2022 v10 PDFDocument58 pagesSign 155 Migraine 2022 v10 PDFDeeNo ratings yet

- Pharmaceutics 14 02240Document17 pagesPharmaceutics 14 02240oliverasrommelNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Pharmacology 1Document5 pagesRunning Head: Pharmacology 1jacobNo ratings yet

- OTC Pain Relievers Dosage Chart For Adults and Children 12 Years and OlderDocument2 pagesOTC Pain Relievers Dosage Chart For Adults and Children 12 Years and OlderAdocueNo ratings yet

- WP contentuploads202209BRAVE Ebook No Brainer PDFDocument24 pagesWP contentuploads202209BRAVE Ebook No Brainer PDFDacianaNo ratings yet

- NSAIDSDocument19 pagesNSAIDSDonna Kelly DuranNo ratings yet

- Case Presentation - Acute Kidney InjuryDocument5 pagesCase Presentation - Acute Kidney InjuryC KandasamyNo ratings yet

- Abstract, Defenitionofterms EditDocument24 pagesAbstract, Defenitionofterms EditRF PopeXianNo ratings yet

- Drug Information Abjad KDocument11 pagesDrug Information Abjad Kfransiska labuNo ratings yet

- Pain ManagementDocument32 pagesPain ManagementShania CandaNo ratings yet

- KetoprofenDocument22 pagesKetoprofenRickNo ratings yet

- Drug Study Diclofenac KDocument3 pagesDrug Study Diclofenac KCarl Julienne Masangcay100% (1)

- A2 2b Rle Final DraftDocument59 pagesA2 2b Rle Final DraftQuiannë Delos ReyesNo ratings yet

- Dr. Marcelia Suryatenggara, Sp. S - How To Choose Your AnalgeticsDocument9 pagesDr. Marcelia Suryatenggara, Sp. S - How To Choose Your AnalgeticsFreade AkbarNo ratings yet

- 20110606-Fkg-Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Drugs Used in Oral Surgery AKHIRDocument63 pages20110606-Fkg-Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Drugs Used in Oral Surgery AKHIRWilan Dita NesyiaNo ratings yet

- OTC Advisor - Fever, Cough, Cold, and Allergy FINAL PDFDocument33 pagesOTC Advisor - Fever, Cough, Cold, and Allergy FINAL PDFmorsi0% (1)

- Animal Model For RA 3Document10 pagesAnimal Model For RA 3amitrameshwardayalNo ratings yet

- WHO Drug Information: Regulatory ChallengesDocument38 pagesWHO Drug Information: Regulatory Challengespurushothama reddyNo ratings yet

- Nursing Rsponsibilities DynastatDocument1 pageNursing Rsponsibilities DynastatJoan Mae BasamotNo ratings yet

- The Paddison Program For Rheumatoid ArthritisDocument7 pagesThe Paddison Program For Rheumatoid ArthritisAmbika Ramesh Font RifoNo ratings yet

- AGS 2023 BEERS PocketDocument9 pagesAGS 2023 BEERS Pocketerika avelina rodriguez jaureguiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 37 - Management of Patients With Gastric and Duodenal DisordersDocument9 pagesChapter 37 - Management of Patients With Gastric and Duodenal DisordersMindy Severino100% (1)

- Drug Card AspirinDocument3 pagesDrug Card Aspirincelosia23100% (10)

- Condroitina Uebelhart Clinical Review of Chondroitin Sulfate in Osteoarthritis 2008Document3 pagesCondroitina Uebelhart Clinical Review of Chondroitin Sulfate in Osteoarthritis 2008Elisabeth PradoNo ratings yet

- Final ProjectDocument33 pagesFinal ProjectShowmiya NNo ratings yet

- Carrageenan 4Document3 pagesCarrageenan 4Cao Đức Duy (19140345)No ratings yet

- The Upward Spiral: Using Neuroscience to Reverse the Course of Depression, One Small Change at a TimeFrom EverandThe Upward Spiral: Using Neuroscience to Reverse the Course of Depression, One Small Change at a TimeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (141)

- Critical Thinking: How to Effectively Reason, Understand Irrationality, and Make Better DecisionsFrom EverandCritical Thinking: How to Effectively Reason, Understand Irrationality, and Make Better DecisionsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (39)

- Summary: The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture By Gabor Maté MD & Daniel Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture By Gabor Maté MD & Daniel Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (9)

- Rewire Your Anxious Brain: How to Use the Neuroscience of Fear to End Anxiety, Panic, and WorryFrom EverandRewire Your Anxious Brain: How to Use the Neuroscience of Fear to End Anxiety, Panic, and WorryRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (157)

- Don't Panic: Taking Control of Anxiety AttacksFrom EverandDon't Panic: Taking Control of Anxiety AttacksRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (12)

- Summary of The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma by Bessel van der Kolk MDFrom EverandSummary of The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma by Bessel van der Kolk MDRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (167)

- An Autobiography of Trauma: A Healing JourneyFrom EverandAn Autobiography of Trauma: A Healing JourneyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Feel the Fear… and Do It Anyway: Dynamic Techniques for Turning Fear, Indecision, and Anger into Power, Action, and LoveFrom EverandFeel the Fear… and Do It Anyway: Dynamic Techniques for Turning Fear, Indecision, and Anger into Power, Action, and LoveRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (250)

- The Complex PTSD Workbook: A Mind-Body Approach to Regaining Emotional Control & Becoming WholeFrom EverandThe Complex PTSD Workbook: A Mind-Body Approach to Regaining Emotional Control & Becoming WholeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (49)

- Redefining Anxiety: What It Is, What It Isn't, and How to Get Your Life BackFrom EverandRedefining Anxiety: What It Is, What It Isn't, and How to Get Your Life BackRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (153)

- Breaking the Chains of Transgenerational Trauma: My Journey from Surviving to ThrivingFrom EverandBreaking the Chains of Transgenerational Trauma: My Journey from Surviving to ThrivingRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (30)

- Feeling Great: The Revolutionary New Treatment for Depression and AnxietyFrom EverandFeeling Great: The Revolutionary New Treatment for Depression and AnxietyNo ratings yet

- Summary: No Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems Model by Richard C. Schwartz PhD & Alanis Morissette: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: No Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems Model by Richard C. Schwartz PhD & Alanis Morissette: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (5)

- The Worry Trick: How Your Brain Tricks You into Expecting the Worst and What You Can Do About ItFrom EverandThe Worry Trick: How Your Brain Tricks You into Expecting the Worst and What You Can Do About ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (107)

- Happiness Hypothesis, The, by Jonathan Haidt - Book SummaryFrom EverandHappiness Hypothesis, The, by Jonathan Haidt - Book SummaryRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (95)

- The Autoimmune Cure: Healing the Trauma and Other Triggers That Have Turned Your Body Against YouFrom EverandThe Autoimmune Cure: Healing the Trauma and Other Triggers That Have Turned Your Body Against YouNo ratings yet

- Overcoming Unwanted Intrusive Thoughts: A CBT-Based Guide to Getting Over Frightening, Obsessive, or Disturbing ThoughtsFrom EverandOvercoming Unwanted Intrusive Thoughts: A CBT-Based Guide to Getting Over Frightening, Obsessive, or Disturbing ThoughtsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (48)

- A Profession Without Reason: The Crisis of Contemporary Psychiatry—Untangled and Solved by Spinoza, Freethinking, and Radical EnlightenmentFrom EverandA Profession Without Reason: The Crisis of Contemporary Psychiatry—Untangled and Solved by Spinoza, Freethinking, and Radical EnlightenmentNo ratings yet

- Somatic Therapy Workbook: A Step-by-Step Guide to Experiencing Greater Mind-Body ConnectionFrom EverandSomatic Therapy Workbook: A Step-by-Step Guide to Experiencing Greater Mind-Body ConnectionNo ratings yet

- My Grandmother's Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and BodiesFrom EverandMy Grandmother's Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and BodiesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (70)

- Binaural Beats: Activation of pineal gland – Stress reduction – Meditation – Brainwave entrainment – Deep relaxationFrom EverandBinaural Beats: Activation of pineal gland – Stress reduction – Meditation – Brainwave entrainment – Deep relaxationRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (9)

- It's All Too Much: An Easy Plan for Living a Richer Life with Less StuffFrom EverandIt's All Too Much: An Easy Plan for Living a Richer Life with Less StuffRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (232)

- Taking Charge of Adult ADHD, Second Edition: Proven Strategies to Succeed at Work, at Home, and in RelationshipsFrom EverandTaking Charge of Adult ADHD, Second Edition: Proven Strategies to Succeed at Work, at Home, and in RelationshipsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (25)

- Beyond Thoughts: An Exploration Of Who We Are Beyond Our MindsFrom EverandBeyond Thoughts: An Exploration Of Who We Are Beyond Our MindsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (7)

- Winning the War in Your Mind: Change Your Thinking, Change Your LifeFrom EverandWinning the War in Your Mind: Change Your Thinking, Change Your LifeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (560)