Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Society and Economic Life 339

Uploaded by

Churrita de OroOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Society and Economic Life 339

Uploaded by

Churrita de OroCopyright:

Available Formats

338 The Stuarts Society and Economic Life 339

tunnage of shipping engaged in coastal trading probably rose Only two groups had 'social' status in seventeenth-century

by the same amount. The roads were thronged with petty England—the gentry and the peerage. Everybody else had 'eco-

chapmen, with their news-sheets, tracts, almanacs, cautionary nomic' status, and was defined by his economic function (hus-

tales, pamphlets full of homespun wisdom; pedlars with trin- bandman, cobbler, merchant, attorney, etc.). The peerage and

kets of all sorts; and travelling entertainers. If the alehouse had gentry were different. They had a 'quality' which set them

always been a distraction from that other social centre of vil- apart. That 'quality' was 'nobility'. Peers and gentlemen were

lage life, the parish church, it now became much more its rival 'noble'; everybody else was 'ignoble' or 'churlish'. Such con-

in the dissemination of news and information and in the forma- cepts were derived partly from the feudal and chivalric tradi-

tion of popular culture. In the early years of the century, tions in which land was held from the Crown in exchange for

national and local regulation of alehouses was primarily con- the performance of military duties. These duties had long since

cerned with ensuring that not too much of the barley harvest disappeared, but the notion that the ownership of land and

was malted and brewed; by the end of the century, regulation 'manors' conferred status and 'honour' had been reinvigorated

was more concerned with the pub's potential for sedition. by the appropriation to English conditions of Aristotle's notion

In the century from 1540 to 1640 there was a redistribution of the citizen. The gentleman or nobleman was a man set apart

of wealth away from rich and poor towards those in the middle to govern. He was independent and leisured: he derived his

of society. The richest men in the kingdom derived the bulk income without having to work for it, that income made him

of their income from rents and services, and these were notor- free from want and from being beholden to or dependent upon

iously difficult to keep in line with inflation: a tradition of long others, and he had the time and leisure to devote himself to the

leases and the custom of fixed rents and fluctuating 'entry arts of government. He was independent in judgement and

fines'—payments made when tenancies changed hands— trained to make decisions. Not all gentlemen served in the

militated against it. Vigilant landowners could keep pace with offices which required such qualities (justice of the peace,

inflation, but many were not vigilant. Equally, those whose sheriff, militia captain, high constable, etc.). But all had this

farms or holdings did not make them self-sufficient suffered capacity to serve, to govern. A gentleman was expected to be

rising (and worse, fluctuating) food prices, while a surplus on hospitable, charitable, fair-minded. He was distinguished from

the labour market and declining real wages made it very hard his country neighbour, the yeoman, as much by attitude of

for the poor to make good the shortfall. The number of land- mind and personal preference as by wealth. Minor gentry and

less labourers and cottagers soared. Those in the middle of yeomen had similar incomes. But they lived different lives: the

society, whether yeomen farmers or tradesmen, prospered. gentleman rented out his lands, wore cloth and linen, read

If they produced a surplus over and above their own needs Latin; the yeoman was a working farmer, wore leather, read

they could sell dear and produce more with the help of cheap and wrote in English. By 1640, there were perhaps 120 peers

labour. They could lend their profits to their poorer neighbours and 20,000 gentry, one in twenty of all adult males. The per-

(there were after all no banks, stocks and shares, building manence of land and the security of landed income restricted

societies) and foreclose on the debts. They invested in more gentility to the countryside; the prosperous merchant or crafts-

land, preferring to extend the scale of their operations rather man, though he may have had a larger income than many

than sink capital into improved productivity. Many of those gentlemen, and have discharged, in the government of his

who prospered from farming rose into the gentry. borough, the same duties, was denied the status of gentleman.

You might also like

- KARL MARX GENESIS OF CAPITALIST FARMERDocument2 pagesKARL MARX GENESIS OF CAPITALIST FARMERArun PrakashNo ratings yet

- The Hispanic Nations of the New World: A Chronicle of Our Southern NeighborsFrom EverandThe Hispanic Nations of the New World: A Chronicle of Our Southern NeighborsNo ratings yet

- Country-House Radicals 1590-1660 by H. R. Trevor-Roper (History Today, July 1953)Document8 pagesCountry-House Radicals 1590-1660 by H. R. Trevor-Roper (History Today, July 1953)Anders FernstedtNo ratings yet

- A Brief History of English SocietyDocument8 pagesA Brief History of English SocietyNikki ParkerNo ratings yet

- George Washington: The Life & Times of George Washington – Complete BiographyFrom EverandGeorge Washington: The Life & Times of George Washington – Complete BiographyNo ratings yet

- Domesday Book: Social Classes The FreeDocument3 pagesDomesday Book: Social Classes The FreeannaNo ratings yet

- The Feudal SystemDocument4 pagesThe Feudal SystemNikhat MehmoodNo ratings yet

- Cantillon Essay on Commerce Part OneDocument105 pagesCantillon Essay on Commerce Part OneLuís Leandro DinisNo ratings yet

- ManorialismDocument6 pagesManorialismbhagyalakshmipranjanNo ratings yet

- King Tenants in Chief Sub Tenants Tenants Serfs: Module II: Medieval Social Formations Feudalism and Manorial SystemDocument10 pagesKing Tenants in Chief Sub Tenants Tenants Serfs: Module II: Medieval Social Formations Feudalism and Manorial SystemArya BNNo ratings yet

- 368 Can Till Ones Say TableDocument75 pages368 Can Till Ones Say TableRaúl MercauNo ratings yet

- Final Crisis of The Middle AgesDocument11 pagesFinal Crisis of The Middle AgesmanavegaNo ratings yet

- Town Life in the Fifteenth Century, Volume 2 (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)From EverandTown Life in the Fifteenth Century, Volume 2 (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)No ratings yet

- 1.3.a-Science and Technology in The Middle AgesDocument17 pages1.3.a-Science and Technology in The Middle Agestwinkledreampoppies100% (1)

- Civi Brit 1Document8 pagesCivi Brit 1lea salhabNo ratings yet

- 02b FeudalismDocument3 pages02b FeudalismFrialynNo ratings yet

- The Armies of Labor: A Chronicle of the Organized Wage-EarnersFrom EverandThe Armies of Labor: A Chronicle of the Organized Wage-EarnersNo ratings yet

- Causes of The French RevolutionDocument19 pagesCauses of The French RevolutionJohnSibandaNo ratings yet

- Black-Owned Businesses in the South Analyzed 1790-1880Document25 pagesBlack-Owned Businesses in the South Analyzed 1790-1880Horace BatisteNo ratings yet

- Civil War Live (Illustrated Edition): Personal Observations and Experiences of Charles Carleton Coffin From the American BattlegroundsFrom EverandCivil War Live (Illustrated Edition): Personal Observations and Experiences of Charles Carleton Coffin From the American BattlegroundsNo ratings yet

- The Feudal System in Medieval EuropeDocument7 pagesThe Feudal System in Medieval EuropeAchintya MandalNo ratings yet

- AncientTimes 42-49 KeyDocument9 pagesAncientTimes 42-49 KeyPremier AcademeNo ratings yet

- Feudal System ArticleDocument4 pagesFeudal System ArticleAchintya MandalNo ratings yet

- Arthur YoungDocument3 pagesArthur Youngapi-68361523No ratings yet

- Civil War Live: Observations and Experiences of Charles Carleton Coffin From the American BattlegroundsFrom EverandCivil War Live: Observations and Experiences of Charles Carleton Coffin From the American BattlegroundsNo ratings yet

- Virginia Since The First Planting of That Colony (London: John Tappe, 1608) - Names of Places and Commodities HaveDocument2 pagesVirginia Since The First Planting of That Colony (London: John Tappe, 1608) - Names of Places and Commodities HaveNhesza Kesha AthenaNo ratings yet

- II Feudalism: TH THDocument4 pagesII Feudalism: TH THAlexandra JuhászNo ratings yet

- The Life of George Washington: The Life History of the First President of United StatesFrom EverandThe Life of George Washington: The Life History of the First President of United StatesNo ratings yet

- Feudalism To CapitalismDocument4 pagesFeudalism To CapitalismAparupa RoyNo ratings yet

- SerfdomDocument8 pagesSerfdomAlex KibalionNo ratings yet

- Civil War Live: Personal Observations and Experiences From the American Battlegrounds (Illustrated Edition)From EverandCivil War Live: Personal Observations and Experiences From the American Battlegrounds (Illustrated Edition)No ratings yet

- Economic revolution_SynopsisDocument6 pagesEconomic revolution_SynopsisEESHANo ratings yet

- Cities and Strangers: How Medieval Urban Centers Grew Through ImmigrationDocument24 pagesCities and Strangers: How Medieval Urban Centers Grew Through ImmigrationZeynepNo ratings yet

- What Is An AmericanDocument15 pagesWhat Is An AmericanCeren EnginNo ratings yet

- Hispanic Nations of the New World; a chronicle of our southern neighborsFrom EverandHispanic Nations of the New World; a chronicle of our southern neighborsNo ratings yet

- Scribd 3Document1 pageScribd 3Churrita de OroNo ratings yet

- Scribd 1Document1 pageScribd 1Churrita de OroNo ratings yet

- Bibliographies and References in a Renaissance DocumentDocument1 pageBibliographies and References in a Renaissance DocumentChurrita de OroNo ratings yet

- Scribd 4Document1 pageScribd 4Churrita de OroNo ratings yet

- Scribd 5Document1 pageScribd 5Churrita de OroNo ratings yet

- SFAFDocument1 pageSFAFChurrita de OroNo ratings yet

- Mightier Than a Lord: The Struggle for the Scottish Crofters' Act of 1886From EverandMightier Than a Lord: The Struggle for the Scottish Crofters' Act of 1886No ratings yet

- ASFDocument1 pageASFChurrita de OroNo ratings yet

- Nelson Goodman - Ways of Worldmaking (1978) Page 51Document1 pageNelson Goodman - Ways of Worldmaking (1978) Page 51Churrita de OroNo ratings yet

- Nelson Goodman - Ways of Worldmaking (1978) Page 27Document1 pageNelson Goodman - Ways of Worldmaking (1978) Page 27Churrita de OroNo ratings yet

- Nelson Goodman - Ways of Worldmaking (1978) Page 23Document1 pageNelson Goodman - Ways of Worldmaking (1978) Page 23Churrita de OroNo ratings yet

- Ex Nihilo Sui Et Subiecti, As The Latin Puts It - and This, in The Strict Sense, Is ADocument1 pageEx Nihilo Sui Et Subiecti, As The Latin Puts It - and This, in The Strict Sense, Is AChurrita de OroNo ratings yet

- Nelson Goodman - Ways of Worldmaking (1978) Page 33Document1 pageNelson Goodman - Ways of Worldmaking (1978) Page 33Churrita de OroNo ratings yet

- ASFAFDocument1 pageASFAFChurrita de OroNo ratings yet

- 450 Bibliographies: C.1250-C.1360, University of Cambridge, PHD No. 18626Document1 page450 Bibliographies: C.1250-C.1360, University of Cambridge, PHD No. 18626Churrita de OroNo ratings yet

- Transmedial Growth and AdaptationDocument1 pageTransmedial Growth and AdaptationChurrita de OroNo ratings yet

- Transmedial Growth and AdaptationDocument1 pageTransmedial Growth and AdaptationChurrita de OroNo ratings yet

- Nelson Goodman - Ways of Worldmaking (1978) Page 41Document1 pageNelson Goodman - Ways of Worldmaking (1978) Page 41Churrita de OroNo ratings yet

- The Nature of Transmediality: Transmedial Growth and Adaptation 247Document1 pageThe Nature of Transmediality: Transmedial Growth and Adaptation 247Churrita de OroNo ratings yet

- PhilosophiaeDocument1 pagePhilosophiaeChurrita de OroNo ratings yet

- Transmedial Growth and Adaptation 251Document1 pageTransmedial Growth and Adaptation 251Churrita de OroNo ratings yet

- Matrix, Who Use The Unknowing Human Inhabitants of Their Worlds For Scientifi CDocument1 pageMatrix, Who Use The Unknowing Human Inhabitants of Their Worlds For Scientifi CChurrita de OroNo ratings yet

- Moth History of The Peloponnesian WarDocument1 pageMoth History of The Peloponnesian WarChurrita de OroNo ratings yet

- 24 The Cambridge Companion To HobbesDocument1 page24 The Cambridge Companion To HobbesChurrita de OroNo ratings yet

- At Glasgow University Library On June 27, 2015 Downloaded FromDocument1 pageAt Glasgow University Library On June 27, 2015 Downloaded FromChurrita de OroNo ratings yet

- At Glasgow University Library On June 27, 2015 Downloaded FromDocument1 pageAt Glasgow University Library On June 27, 2015 Downloaded FromChurrita de OroNo ratings yet

- A Summary Biography of Hobbes 25: de Homine, Corpore.Document1 pageA Summary Biography of Hobbes 25: de Homine, Corpore.Churrita de OroNo ratings yet

- 14 The Cambridge Companion To HobbesDocument1 page14 The Cambridge Companion To HobbesChurrita de OroNo ratings yet

- At Glasgow University Library On June 27, 2015 Downloaded FromDocument1 pageAt Glasgow University Library On June 27, 2015 Downloaded FromChurrita de OroNo ratings yet

- At Glasgow University Library On June 27, 2015 Downloaded FromDocument1 pageAt Glasgow University Library On June 27, 2015 Downloaded FromChurrita de OroNo ratings yet

- At Glasgow University Library On June 27, 2015 Downloaded FromDocument1 pageAt Glasgow University Library On June 27, 2015 Downloaded FromChurrita de OroNo ratings yet

- LT Tax Advantage FundDocument2 pagesLT Tax Advantage FundDhanashri WarekarNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7 Audit of LiabilitiesDocument26 pagesChapter 7 Audit of LiabilitiesSteffany Roque100% (2)

- Compania Maritima vs. Allied Free Workers UnionDocument18 pagesCompania Maritima vs. Allied Free Workers UnionAngelReaNo ratings yet

- Government Structure in CanadaDocument4 pagesGovernment Structure in CanadaMichelleLawNo ratings yet

- All About Indian Administrative System - GK Notes For Bank & SSC Exams! - Testbook Blog PDFDocument7 pagesAll About Indian Administrative System - GK Notes For Bank & SSC Exams! - Testbook Blog PDFArathi NittadukkamNo ratings yet

- CR Vantage Plus Traders Awards 2023 Promotion ENDocument4 pagesCR Vantage Plus Traders Awards 2023 Promotion ENCatarina VelezNo ratings yet

- History Final Project by Noah A and Xavier HDocument18 pagesHistory Final Project by Noah A and Xavier Hapi-232469506No ratings yet

- Dáil Eireann Debate OF PESCO EU ARMY IN SECRETDocument488 pagesDáil Eireann Debate OF PESCO EU ARMY IN SECRETRita CahillNo ratings yet

- NAILTA's Amicus Curiae BriefDocument36 pagesNAILTA's Amicus Curiae BriefOAITANo ratings yet

- Current Affairs Solved MCQsDocument12 pagesCurrent Affairs Solved MCQsmuhammad_sarwar_270% (1)

- Investment Pattern of Salaried Persons in MumbaiDocument62 pagesInvestment Pattern of Salaried Persons in MumbaiyopoNo ratings yet

- 2012 Legal Ethics Bar Exam QDocument30 pages2012 Legal Ethics Bar Exam QClambeaux100% (1)

- Aviation Industry in IndiaDocument23 pagesAviation Industry in IndiaKranthi PatiNo ratings yet

- Habaluyas Enterprises Vs JapsonDocument1 pageHabaluyas Enterprises Vs JapsonJL A H-DimaculanganNo ratings yet

- 5070 Manthan2.0JANUARY-2024 WEEK-4 (Topic1-10) V02012024Document38 pages5070 Manthan2.0JANUARY-2024 WEEK-4 (Topic1-10) V02012024Vanshika GaurNo ratings yet

- American Transport Lines, Inc. v. Jorge Wrves, Maria Wrves, Miami General Supply, Inc., Anauco Corp., Occidental Fragrances Corp., Imex, Usa, Inc., 985 F.2d 1065, 11th Cir. (1993)Document3 pagesAmerican Transport Lines, Inc. v. Jorge Wrves, Maria Wrves, Miami General Supply, Inc., Anauco Corp., Occidental Fragrances Corp., Imex, Usa, Inc., 985 F.2d 1065, 11th Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Cement Infobank 2016Document49 pagesCement Infobank 2016Priya SinghNo ratings yet

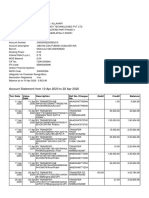

- Statement of Account: Product: Ca-Gen-Pub-Metro/Urban-Inr Currency: INRDocument1 pageStatement of Account: Product: Ca-Gen-Pub-Metro/Urban-Inr Currency: INRAottry MukherjeeNo ratings yet

- The First Epistle of Paul To The CorinthiansDocument14 pagesThe First Epistle of Paul To The Corinthiansmaxi_mikeNo ratings yet

- RODRIGUEZ VS TAN HEIRS' RIGHT TO ADMINISTER ESTATEDocument2 pagesRODRIGUEZ VS TAN HEIRS' RIGHT TO ADMINISTER ESTATEtops videosNo ratings yet

- Edited-Preschool LiteracyDocument22 pagesEdited-Preschool LiteracyEdna ZenarosaNo ratings yet

- Earn 5 Unlocks For Every 10 Resources You UploadDocument1 pageEarn 5 Unlocks For Every 10 Resources You UploadHuber Emiro Riascos GomezNo ratings yet

- Adam Nitti - Not of This World Digital BooketDocument6 pagesAdam Nitti - Not of This World Digital BooketAbimael Reis33% (3)

- G.R. No. 171146Document9 pagesG.R. No. 171146Atty McdNo ratings yet

- Account activity and balance from 10 Apr to 22 AprDocument2 pagesAccount activity and balance from 10 Apr to 22 AprSRIDHAR allhari0% (1)

- BS7419 1991 PDFDocument13 pagesBS7419 1991 PDFsurangaNo ratings yet

- Syllabus - LABOR LAW 1-Atty. TiofiloDocument12 pagesSyllabus - LABOR LAW 1-Atty. TiofiloJeffrey MendozaNo ratings yet

- 19 - BPI Employees Union v. BPI - G.R. No. 178699. September 21, 2011Document2 pages19 - BPI Employees Union v. BPI - G.R. No. 178699. September 21, 2011Jesi CarlosNo ratings yet

- L/epublit Of: TBT BtlippintgDocument8 pagesL/epublit Of: TBT BtlippintgCesar ValeraNo ratings yet

- Te Ture Whenua Maori Act 1993Document294 pagesTe Ture Whenua Maori Act 1993:eric:1313No ratings yet

- Learn Arabic: 3000 essential words and phrasesFrom EverandLearn Arabic: 3000 essential words and phrasesRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Phrasal Verbs for TOEFL: Hundreds of Phrasal Verbs in DialoguesFrom EverandPhrasal Verbs for TOEFL: Hundreds of Phrasal Verbs in DialoguesNo ratings yet

- English Made Easy Collection (for Beginners): Beginner English, Conversation Dialogues, & Simple Medical EnglishFrom EverandEnglish Made Easy Collection (for Beginners): Beginner English, Conversation Dialogues, & Simple Medical EnglishNo ratings yet

- Learn German: 3000 essential words and phrasesFrom EverandLearn German: 3000 essential words and phrasesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Learn Spanish: 3000 essential words and phrasesFrom EverandLearn Spanish: 3000 essential words and phrasesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Words You Should Know to Sound Smart: 1200 Essential Words Every Sophisticated Person Should Be Able to UseFrom EverandThe Words You Should Know to Sound Smart: 1200 Essential Words Every Sophisticated Person Should Be Able to UseRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Webster's New World Power Vocabulary, Volume 4From EverandWebster's New World Power Vocabulary, Volume 4Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (75)

- Conversational Languages: The Most Innovative Technique to Master Any Foreign LanguageFrom EverandConversational Languages: The Most Innovative Technique to Master Any Foreign LanguageRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (5)

- Let's Bring Back: The Lost Language Edition: A Collection of Forgotten-Yet-Delightful Words, Phrases, Praises, Insults, Idioms, and Literary Flourishes from Eras PastFrom EverandLet's Bring Back: The Lost Language Edition: A Collection of Forgotten-Yet-Delightful Words, Phrases, Praises, Insults, Idioms, and Literary Flourishes from Eras PastRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (12)

- The Official Dictionary of Idiocy: A Lexicon For Those of Us Who Are Far Less Idiotic Than the Rest of YouFrom EverandThe Official Dictionary of Idiocy: A Lexicon For Those of Us Who Are Far Less Idiotic Than the Rest of YouNo ratings yet

- Barkham Burroughs' Encyclopaedia of Astounding Facts and Useful InformationFrom EverandBarkham Burroughs' Encyclopaedia of Astounding Facts and Useful InformationNo ratings yet

- Easy Learning Spanish Complete Grammar, Verbs and Vocabulary (3 books in 1): Trusted support for learningFrom EverandEasy Learning Spanish Complete Grammar, Verbs and Vocabulary (3 books in 1): Trusted support for learningRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Easy Learning German Complete Grammar, Verbs and Vocabulary (3 books in 1): Trusted support for learningFrom EverandEasy Learning German Complete Grammar, Verbs and Vocabulary (3 books in 1): Trusted support for learningRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)