Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Project Management

Project Management

Uploaded by

Nahid Abubakr0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

10 views2 pagesOriginal Title

project management

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

TXT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as TXT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

10 views2 pagesProject Management

Project Management

Uploaded by

Nahid AbubakrCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as TXT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 2

Another means of reducing conflicts and minimizing the need for communication was

detailed planning. Functional representation would be present at all planning,

scheduling,

and budget meetings. This method worked best for nonrepetitive tasks and projects.

In the traditional organization, one of the most important responsibilities of

upper-

level management was the resolution of conflicts through �hierarchical referral.�

The con-

tinuous conflicts and struggle for power between the functional units consistently

required

that upper-level personnel resolve those problems resulting from situations that

were either

nonroutine or unpredictable and for which no policies or procedures existed.

The fourth method is direct contact and interactions by the functional managers.

The

rules and procedures, as well as the planning process method, were designed to

minimize

ongoing communications between functional groups. The quantity of conflicts that

execu-

tives had to resolve forced key personnel to spend a great percentage of their time

as arbi-

trators, rather than as managers. To alleviate problems of hierarchical referral,

upper-level

management requested that all conflicts be resolved at the lowest possible levels.

This

required that functional managers meet face-to-face to resolve conflicts.

In many organizations, these new methods proved ineffective, primarily because

there

still existed a need for a focal point for the project to ensure that all

activities would be

properly integrated.

When the need for project managers was acknowledged, the next logical question was

where in the organization to place them. Executives preferred to keep project

managers

low in the organization. After all, if they reported to someone high up, they would

have to

be paid more and would pose a continuous threat to management.

The first attempt to resolve this problem was to develop project leaders or

coordina-

tors within each functional department, as shown in Figure 3�2. Section-level

personnel

were temporarily assigned as project leaders and would return to their former

positions at

project termination. This is why the term �project leader� is used rather than

�project man-

ager,� as the word �manager� implies a permanent relationship. This arrangement

proved

effective for coordinating and integrating work within one department, provided

that the

correct project leader was selected. Some employees considered this position an

increase

in power and status, and conflicts occurred about whether assignments should be

based on

experience, seniority, or capability. Furthermore, the project leaders had almost

no author-

ity, and section-level managers refused to take directions from them, fearing that

the

project leaders might be next in line for the department manager�s position.

When the activities required efforts that crossed more than one functional

boundary, con-

flicts arose. The project leader in one department did not have the authority to

coordinate activ-

ities in any other department. Furthermore, the creation of this new position

caused internal

conflicts within each department. As a result, many employees refused to become

dedicated to

project management and were anxious to return to their �secure� jobs. Quite often,

especially

when cross-functional integration was required, the division manager was forced to

act as the

project manager. If the employee enjoyed the assignment of project leader, he would

try to

�stretch out� the project as long as possible.

Even though we have criticized this organizational form, it does not mean that it

can-

not work. Any organizational form will work if the employees want it to work. As an

example, a computer manufacturer has a midwestern division with three departments,

as

in Figure 3�2, and approximately fourteen people per department. When a project

comes

Developing Work Integration Positions 99

c03.qxd 1/21/09 11:30 AM Page 99

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5810)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (346)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Staff of FEdex and TCSDocument13 pagesStaff of FEdex and TCSMUHAMMAD FAHAM L1F15BBAM0169No ratings yet

- Transform Your Life Handwriting: ThroughDocument5 pagesTransform Your Life Handwriting: Throughadvanced1313100% (1)

- New Project UploadDocument69 pagesNew Project UploadNahid AbubakrNo ratings yet

- Study On The Effect of Replacement of Portland Cement by Sugar Cane Bagasse Ash and Egg Shell Powder On HPCDocument4 pagesStudy On The Effect of Replacement of Portland Cement by Sugar Cane Bagasse Ash and Egg Shell Powder On HPCNahid AbubakrNo ratings yet

- .Trashed-4 5843498676328074672Document20 pages.Trashed-4 5843498676328074672Nahid AbubakrNo ratings yet

- Hydraulic Structures: Seepage Theories (I)Document22 pagesHydraulic Structures: Seepage Theories (I)Nahid AbubakrNo ratings yet

- Dissipation of Mechanical Energy Over Spillway Through Counter FlowDocument15 pagesDissipation of Mechanical Energy Over Spillway Through Counter FlowNahid AbubakrNo ratings yet

- Project:Residential Building Location: Khartoum"Alsahafa" Block No: 20 Sheet Name: G.Beams &slabs SectionDocument1 pageProject:Residential Building Location: Khartoum"Alsahafa" Block No: 20 Sheet Name: G.Beams &slabs SectionNahid AbubakrNo ratings yet

- منشات هيدروليكية مرحلة رابعةDocument100 pagesمنشات هيدروليكية مرحلة رابعةNahid Abubakr100% (1)

- Archivetemppresentation XML PDFDocument2 pagesArchivetemppresentation XML PDFNahid AbubakrNo ratings yet

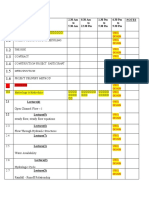

- NO. Subject Notes: 2.30 Am To 5.30 Am 8.30 Am To 12.30 PM 1.30 PM To 5.30 PM 6.30 PM To 9.30 PMDocument4 pagesNO. Subject Notes: 2.30 Am To 5.30 Am 8.30 Am To 12.30 PM 1.30 PM To 5.30 PM 6.30 PM To 9.30 PMNahid AbubakrNo ratings yet

- TasksDocument1 pageTasksNahid AbubakrNo ratings yet

- .Archivetemp (Content Types) .XMLDocument3 pages.Archivetemp (Content Types) .XMLNahid AbubakrNo ratings yet

- A Survey: Unethical Issues in AdvertisingDocument4 pagesA Survey: Unethical Issues in AdvertisingRitesh ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Aung Kyaw Moe Task 4 Module 1Document9 pagesAung Kyaw Moe Task 4 Module 1Ibrahim AbdiNo ratings yet

- Theoretical Blending: EPC Contractor ClientDocument4 pagesTheoretical Blending: EPC Contractor ClientDeepakNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Management AccountingDocument484 pagesFundamentals of Management AccountingMorick Gibson Mwasaga100% (9)

- Amity Business School: MBA Legal Aspects of Business Ms. Shinu VigDocument20 pagesAmity Business School: MBA Legal Aspects of Business Ms. Shinu VigAamir MalikNo ratings yet

- Yema CandyDocument2 pagesYema CandyBar2012100% (1)

- BCL - Intro To LawDocument17 pagesBCL - Intro To LawAisyah MakhzanNo ratings yet

- BER Performance of OFDM-Based Visible Light Communication SystemsDocument6 pagesBER Performance of OFDM-Based Visible Light Communication SystemsKarim Abd El HamidNo ratings yet

- AGSM Full-Time MBA Scholarships: Recognising True TalentDocument2 pagesAGSM Full-Time MBA Scholarships: Recognising True TalentChandra ErickNo ratings yet

- Designing Traffic Signs: A Case Study On Driver Reading Patterns and BehaviorDocument8 pagesDesigning Traffic Signs: A Case Study On Driver Reading Patterns and Behaviorzero bitsNo ratings yet

- 6ra7031 6dv62 0 Siomreg DC Converter Siemens ManualDocument234 pages6ra7031 6dv62 0 Siomreg DC Converter Siemens ManualBorislav ChavdarovNo ratings yet

- Automation in Jaggery Making Using PLCDocument49 pagesAutomation in Jaggery Making Using PLCavinash shahapureNo ratings yet

- NKDM Wo F1 DH PWs 7 FLDocument8 pagesNKDM Wo F1 DH PWs 7 FLAravind ChunduriNo ratings yet

- Dynamics of Infectious DiseasesDocument41 pagesDynamics of Infectious DiseasesRodrigo ChangNo ratings yet

- List of 10 Sexiest Women in The WorldDocument1 pageList of 10 Sexiest Women in The WorldDetained EngineersNo ratings yet

- Olivia Pettenati2016Document1 pageOlivia Pettenati2016api-315892089No ratings yet

- Application No: RegularDocument2 pagesApplication No: RegularBussiness EmpireNo ratings yet

- Raw JHS Map7 Study Guide WK8Document14 pagesRaw JHS Map7 Study Guide WK8Jerick Carbonel SubadNo ratings yet

- Indigenous People of The CaribbeanDocument27 pagesIndigenous People of The CaribbeanROXANNE MORRIS100% (5)

- 09 2017 EJPB Lallemand Cyclosporine A Delivery To The Eye A Comprehensive Review of Academic and Industrial EffortsDocument15 pages09 2017 EJPB Lallemand Cyclosporine A Delivery To The Eye A Comprehensive Review of Academic and Industrial EffortsFagner CruzNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Philosophy of The Human Person IntersubjectivityDocument24 pagesIntroduction To The Philosophy of The Human Person IntersubjectivityGlezy Yutuc50% (2)

- American Apple Pie RecipeDocument21 pagesAmerican Apple Pie RecipeCristohper RFNo ratings yet

- PrintMSDSAction PDFDocument11 pagesPrintMSDSAction PDFM.ASNo ratings yet

- Take Five: The Dave Brubeck Quartet Arranged by Trinity Chung 174 174 Swing SwingDocument13 pagesTake Five: The Dave Brubeck Quartet Arranged by Trinity Chung 174 174 Swing SwingJudit Díaz ÁlvarezNo ratings yet

- A Resolution For Reappropriation 10 SK Funds For Cy 2014 To 2017Document2 pagesA Resolution For Reappropriation 10 SK Funds For Cy 2014 To 2017Maribel MontajesNo ratings yet

- MC Donalds v. LC Big MakDocument2 pagesMC Donalds v. LC Big MakArah Salas PalacNo ratings yet

- Service Supply RelationshipsDocument18 pagesService Supply RelationshipsBhavna AdvaniNo ratings yet

- DX-D 400 (English - Brochure)Document8 pagesDX-D 400 (English - Brochure)luc1902No ratings yet