Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Brittan On Berlioz PDF

Uploaded by

KatieOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Brittan On Berlioz PDF

Uploaded by

KatieCopyright:

Available Formats

Berlioz and the Pathological Fantastic: Melancholy, Monomania, and Romantic

Autobiography

Author(s): Francesca Brittan

Source: 19th-Century Music , Vol. 29, No. 3 (Spring 2006), pp. 211-239

Published by: University of California Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/ncm.2006.29.3.211

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

University of California Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access

to 19th-Century Music

This content downloaded from

130.253.26.76 on Thu, 03 Sep 2020 19:41:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

FRANCESCA

BRITTAN

Berlioz and

the Pathological

Fantastic

Berlioz and the Pathological Fantastic:

Melancholy, Monomania, and Romantic

Autobiography

FRANCESCA BRITTAN

IDÉES FIXES: Uncanny Returns In his 1814 story, “Automata,” E. T. A. Hoff-

mann described an unusual love-sickness af-

How can I ever hope to give you the faintest idea of flicting the young and impressionable artist

the effect of those long-drawn swelling and dying Ferdinand. The malaise is born during a dream-

notes upon me. I had never imagined anything ap- vision—a “half-conscious state” brought on by

proaching it. The melody was marvelous—quite un- alcohol and fatigue—during which Ferdinand

like anything I had ever heard. It was itself the deep, hears a melody of such exquisite effect that it

tender sorrow of the most fervent love. As it rose in

transfixes him with “boundless longing.” The

simple phrases . . . a rapture which words cannot

describe took possession of me—the pain of bound-

melody is sung by a mysterious woman, whose

less longing seized my heart like a spasm.1 “spirit voice” awakens the innermost sounds

sleeping in his heart, articulating a long-sought

ideal:

I recognized, with unspeakable rapture, that she was

the beloved of my soul, whose image had been en-

shrined in my heart since childhood. Though an

I would like to express sincere thanks to Neal Zaslaw,

adverse fate had torn her from me for a time, I had

James Webster, Julian Rushton, and David Rosen, as well

as to the editors of this journal, for their invaluable assis- found her again now; but my deep and fervent love

tance with this project. for her melted into that wonderful melody of sor-

row, and our words and our looks grew into exquis-

1

E. T. A. Hoffmann, “Automata” (Die Automate), trans. ite swelling tones of music, flowing together into a

Major Alexander Ewing in The Best Tales of Hoffmann,

ed. E. F. Bleiler (New York: Dover, 1967), p. 85. This tale river of fire.2

first appeared as a whole in the Zeitung für die elegante

Welt in 1814, although it was written earlier, between

2

parts of “The Golden Flower Pot.” Ibid., p. 86.

19th-Century Music, XXIX/3, pp. 211–39. ISSN: 0148-2076, electronic ISSN 1533-8606. © 2006 by the Regents of the Univer- 211

sity of California. All rights reserved. Please direct all requests for permission to photocopy or reproduce article content

through the University of California Press’s Rights and Permissions website, at http://www.ucpress.edu/journals/rights.htm.

This content downloaded from

130.253.26.76 on Thu, 03 Sep 2020 19:41:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

19 TH Ferdinand is engulfed by an uncontrollable pas- edness of Emma.”5 Within days, Édouard’s pas-

CENTURY

MUSIC sion for the dream-woman—an amorous obses- sion becomes overwhelming, and, absorbed in

sion that, ossifying into an idée fixe, compels the “imaginary joys” of amorous fantasy, he

him to “give up everybody and everything but retreats into solipsistic reverie: “Surrendering

the most eager search for the very slightest myself to my sole thought, absorbed by one

trace of [his] unknown love.”3 By an uncanny fantasy alone, I lived once more in a world of

coincidence, every time he glimpses the lady, my own creation. . . . I saw Mme de Nevers, I

Hoffmann’s young lover hears the “long-drawn heard her voice, her glance made me tremble, I

swelling and dying notes” of her bewitching breathed in the perfume of her beautiful hair.

melody; beloved woman and mysterious music . . . Incapable of any study or other affair, I was

are inextricably linked as a malignant musico- sickened by this occupation.”6 Imaginary plea-

erotic fetish that begins to exert a hostile influ- sure soon gives way to torturous mental fixa-

ence on his “whole existence.” Eventually— tion; Édouard’s love for the unattainable Mme

having lost his beloved forever—he gives way de Nevers devolves into “a real misery” (un

to a “distracted condition of the mind,” fleeing véritable malheur) and, suffering hallucinations

to a distant town and writing only that he and palpitations, he describes the delirium of

might never return.4 an idée fixe: “I fell soon into a state hovering

Several years later, in Paris, Mme de Duras between despair and madness; consumed by an

described an amorous illness of similar cast— idée fixe, I saw Madame de Nevers ceaselessly;

an obsessive love manifesting itself through she pursued me during my sleep, I rushed forth

the relentless grip of an idée fixe. Her 1825 to seize her in my arms, but an abyss opened

novel, Édouard, tells the tale of a solitary youth suddenly between us.”7

plagued by melancholic reveries and restless Hounded even in sleep by images of his be-

dissatisfaction. As a young man, Édouard trav- loved, Édouard flees to the country in hopes of

els to Paris, where he falls hopelessly in love finding relief in the pastoral landscape. But on

with Natalie Nevers, the daughter of an old his rambling walks, he is visited by “hollow

family friend and a lady of high rank. She is the and terrible phantoms” (ombres vaines et

woman he has dimly imagined and unknow- terribles) and by inescapable thoughts of his

ingly sought since childhood; indeed, she com- Natalie, which, plunging him deeper into dis-

bines the fictional and even celestial perfec-

tions of an ideal beloved: “I found in Mme de

Nevers the beauty and modesty of Milton’s

Eve, the tenderness of Juliette, and the devot-

5

“Je trouvais à Mme de Nevers la beauté et la modestie de

l’Ève de Milton, la tendresse de Juliette, et le dévouement

d’Emma.” Presumably, Édouard is referring to Jane Austen’s

Emma. This excerpt (p. 124) and all others are given in my

3

Ibid., p. 87. Hoffmann introduces the term “idée fixe” in translations of an edition containing Édouard and another

the first section of the tale to describe a variety of un- short novel: Madame de Genlis: Mademoiselle de Cler-

canny and supernatural obsessions. The sisters Adelgunda mont; Madame de Duras: Edouard, afterword Gérard

and Augusta, for instance, fixate on the specter of the Gengembre (Paris: Editions Autrement, 1994). Mme de

White Lady, an apparition haunting the garden of their Duras (1778–1828) was born Claire Louise de Kersaint; she

family home. Of Adelgunda, Hoffmann writes: “There was, published two successful novels in the mid-1820s in Paris

of course, no lack of doctors, or of plans of treatment for (Ourika in 1824 and Édouard in 1825).

6

ridding the poor soul of the idée fixe, as people were pleased “Livré à mon unique pensée, absorbé par un seul souve-

to term the apparition which she said she saw” (p. 75). nir, je vivais encore un fois dans un monde créé par moi-

The fixation, in the case of both sisters, arises from a même . . . je voyais Mme de Nevers, j’entendais sa voix,

“disordered imagination” and culminates in insanity. son regard me faisait tressaillir je respirais le parfum de

Among other types of idée fixe, Hoffmann describes a “mu- ses beaux cheveux. . . . Incapable d’aucune étude et

sical” haunting—a man fixated on an invisible keyboardist d’aucune affaire, c’était l’occupation qui me dérangeait”

whose “compositions of the most extraordinary kind” are (ibid., pp. 89–90).

7

to be heard every night, although the player himself never “Je tombai bientôt dans un état qui tenait le milieu entre

materializes (p. 78). These fixations foreshadow Ferdinand’s le désespoir et la folie; en proie à une idée fixe, je voyais

own obsession with the musical lady, which Hoffmann sans cesse Mme de Nevers: elle me poursuivait pendant

aligns clearly with the earlier idées fixes, although he does mon sommeil; je m’élançais pour la saisir dans mes bras,

not use the term again. mais un abîme se creusait tout à coup entre nous deux”

4

Ibid., pp. 100–01. (ibid., p. 131).

212

This content downloaded from

130.253.26.76 on Thu, 03 Sep 2020 19:41:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

orientation and despair, spark suicidal impulses: of “groundless joy,” “frenzied passion,” fury, FRANCESCA

BRITTAN

“I have no more future,” he proclaims, “and I jealousy, and tears culminate in a state of sui- Berlioz and

look for no repose but that of death.”8 cidal desperation. Like Édouard, the jeune the Pathological

Fantastic

A scant five years later, the love-illness trou- musicien is lured inexorably inward, toward a

bling Édouard, and Ferdinand before him, af- realm of disordered imagination from which

flicted the jeune musicien of Berlioz’s Sym- there is no retreat. Indeed, when Berlioz intro-

phonie fantastique (1830) in one of the nine- duces the familiar idée fixe, in part 1 of the

teenth century’s most famous tales of “fixated” Fantastique’s program, we can already antici-

passion. Berlioz’s story resonates immediately pate his hero’s ill fate:

with both Hoffmann and Duras, echoing frag-

ments of both narratives, and detailing the now- Reveries—Passions

familiar tortures of an amorous idée fixe. Most The author imagines that a young musician, afflicted

striking is the resemblance between Hoffmann’s with that moral disease that a well-known writer

and Berlioz’s musical fetish; Hoffmann prefig- calls the vague des passions, sees for the first time a

woman who embodies all the charms of the ideal

ures the “double” idée fixe—the yoking of amo-

being he has imagined in his dreams, and he falls

rous and aural fixation—so often identified as a

desperately in love with her. Through an odd whim,

key innovation of the Symphonie fantastique. whenever the beloved appears before the mind’s eye

Parallels between Berlioz and Duras are equally of the artist it is linked with a musical thought

transparent; indeed, Édouard is a work the com- whose character, passionate but at the same time

poser is likely to have known, and one that noble and shy, he finds similar to the one he at-

foreshadows many of the key elements of his tributes to the beloved.

own fantastic narrative.9 This melodic image and the model it reflects pur-

Berlioz’s protagonist, like Duras’s hero, falls sue him incessantly like a double idée fixe. That is

in love with an ideal beloved who embodies the reason for the constant appearance, in every

the perfections of a dream creature. But amo- moment of the symphony, of the melody that begins

the first Allegro. The passage from this state of mel-

rous fantasy escalates into the consuming ob-

ancholy reverie, interrupted by a few fits of ground-

session of an idée fixe that pursues the jeune

less joy, to one of frenzied passion, with its move-

musicien both sleeping and waking, torment- ments of fury, of jealousy, its return of tenderness,

ing him even on a pastoral country retreat. As its tears, its religious consolations—this is the sub-

in Duras, love leans toward pathology, and de- ject of the first movement.11

scriptions of the jeune musicien’s amorous at-

tachment are increasingly permeated with the Clearly, Berlioz was not the first to document

rhetoric of disease. A diffuse maladie morale the mysterious malady signaled by an amorous

linked with the melancholy and restlessness of fixation, nor was “idée fixe” itself a “new term

Chateaubriand’s vague des passions quickly in the 1830s,” as Hugh Macdonald has recently

escalates into a more serious problem charac- suggested.12 Rather, Berlioz’s love-illness boasts

terized by hallucinations, delusional reveries,

and “black presentiments.”10 Wild alternations

qui précède le développement des passions, lorsque nos

facultés, jeunes, actives, entières, mais renfermées, ne se

8

“Je n’ai plus d’avenir, et je ne vois de repos que dans la sont exercées que sur elles-mêmes, sans but et sans objet”

mort” (ibid., p. 120). (a state of the soul which . . . has not yet been sufficiently

9

As Elizabeth Teichmann points out in her study, La For- studied, namely, that which precedes the development of

tune d’Hoffmann en France (Paris: Minard and Droz, 1961), our passions when our faculties are young, active, and

“Automata” was not among the Hoffmann tales published whole, but closed in and exercised only on themselves,

in French translation during the 1830s. It is doubtful, there- without aim or object).

11

fore, that Berlioz had read the tale himself, although he From the 1845 version of the program published with

may have heard of it through some other avenue. That he the score, trans. Edward T. Cone, in Berlioz: Fantastic

knew Duras’s novel is much more likely, for he was an Symphony; An Authoritative Score, Historical Background,

avid reader well versed in the prose and poetry of his Analysis, Views and Comments (New York: Norton, 1971),

Parisian contemporaries. p. 23.

10 12

Chateaubriand describes the vague des passions in his See Hugh Macdonald’s entry under “idée fixe” in the

Génie du christianisme (II, 3, chap. 9; 1802) as “un état de New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, ed. Stanley

l’âme qui . . . n’a pas encore été bien observé; c’est celui Sadie (London: Macmillan, 2001), vol. 12, p. 72.

213

This content downloaded from

130.253.26.76 on Thu, 03 Sep 2020 19:41:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

19 TH a rich literary pedigree and a considerably longer tradition of literary “fixations”—obsessions that

CENTURY

MUSIC history than has thus far been imagined. Along- reached well beyond general romantic attach-

side the tales of erotic fixation by Hoffmann ment into the realm of clinical disorder. By

and Duras, we could place Louis Lanfranchi’s 1825, in the popular Physiologie du goût, the

novel, Voyage à Paris, ou Esquisses des hommes idée fixe was figured as a recognizable and treat-

et des choses dans cette capitale (Voyage to able pathology remedied—so Brillat-Savarin

Paris, or Sketches of the People and Things in claimed—by a dose of “amber chocolate.”16 As

that Capital [Paris, 1830]). As Peter Bloom has this fanciful “cure” suggests, the history of

also noted, Lanfranchi’s chapter titled “Episode Berlioz’s fixation lay not only in the realm of

de la vie d’un voyageur” features a young man literature but in the scientific sphere, at a curi-

with another “double” obsession, this time a ous intersection between medicine and aesthet-

visual-erotic fixation: he searches through Paris ics. Fiction begins to overlap with psychiatric

for a beautiful woman whose imaginary image theory and literature with “real life” as we

appears in his mind “like an idée fixe” when- trace the origins of the idée fixe; indeed, Berlioz

ever he sees a rose.13 Even the “musical idée drew on his own obsessive temperament as a

fixe” had precedents, notwithstanding Macdon- model for the jeune musicien.

ald’s claim that Berlioz “coined” the idea; well The first known draft of Berlioz’s symphonic

before Hoffmann imagined a musico-erotic fe- program, contained in a letter from the com-

tish, the Italian composer Gaetano Brunetti had poser to Humbert Ferrand, is prefaced by a pro-

incorporated a malignant “fixed idea” into his vocative autobiographical claim: “Now, my

programmatic Symphony No. 33, titled “Il friend, here is how I have woven my novel

maniático.”14 [mon roman], or rather my history [mon

Far from new, then, Berlioz’s amorous ob- histoire], whose hero you will have no diffi-

session resonates with a host of earlier fictional culty recognizing.”17 Berlioz was referring, of

fetishes.15 Although I do not suggest that he course, to the link between his hero’s torturous

knew all of the idées fixes cited here, it is clear infatuation and his own difficult love life—a

that his symphony participated in an existing history of unrequited amour, which manifested

itself first as a hopeless childhood crush and

later, more intensely, during his famous pur-

suit of the Irish actress, Harriet Smithson. The

13

Peter Bloom, The Life of Berlioz (Cambridge: Cambridge rapport between art and life in the Symphonie

University Press, 1998), p. 51.

14

Written in 1780, Brunetti’s “Il maniático” not only pre- fantastique is by no means simple—Berlioz

figures Berlioz’s recurring musical device, but makes an himself suggested an overlap between novelis-

early reference to an obsessive type of madness later named tic and autobiographical modes18—but the com-

and defined in French psychiatric theory. The symphony

“describes (as far as possible, using only instruments, and poser made an unambiguous point of contact

without the help of words) the fixation of a madman on between himself and his jeune musicien in a

one single purpose or idea.” Brunetti represents mental letter to Stephen de La Madelaine (early Febru-

fixation with a repeating cello motif that permeates all the

movements of the symphony, before the “madman” is ary 1830), in which he described his escalating

finally coaxed away from obsessive repetition. For a mod- infatuation with Smithson in precisely the

ern edition with preface, notes, and the above quote from

the symphony’s program, see Classici italiani della musica,

vol. 3, ed. A. Bonacorsi (Rome: Lorenzo del Turco, ca.

1960). My thanks to Ralph Locke for bringing Brunetti’s

symphony to my attention.

15 16

Reviews in both Le Figaro (11/12 April 1830) and the Brillat-Savarin, Physiologie du gout ou méditations de

Journal des Débats (22 Feb. 1830) bear witness to another gastronomie transcendente: Ouvrage théorique, historique,

narrative of “fixated” passion—a tale entitled Idée Fixe by et à l’ordre du jour dédié aux gastronomes parisiens (Paris:

the anonymous author of La Fille d’un roi. Although the Garnier Frères, 1824), p. 118.

17

novel seems not to have survived, we learn from these Correspondance générale, ed. Pierre Citron (Paris:

reviews that it revolves around the sufferings of M. Flammarion, 1972–2003) (henceforward CG), I, 158 (16 April

Léopold—“a soul entirely occupied and exalted by a pro- 1830). This and subsequent translations of Berlioz’s letters

found and deep passion” for the “celestial” Noëma. As are mine unless otherwise indicated.

18

with many similar tales, the hero’s obsessive amour leads The autobiographical status of the Fantastique is a com-

to “desperation” and “the sad resignation of suicide.” plex question to which I shall return in the last section of

(Quotes are taken from the Figaro review.) this article.

214

This content downloaded from

130.253.26.76 on Thu, 03 Sep 2020 19:41:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

pathological terms defining his hero’s malady: references to the physical debilitation, psycho- FRANCESCA

BRITTAN

“I was going to come and see you today, but logical disturbances, and imaginative excess Berlioz and

the frightful state of nervous exaltation which I occasioned by his idée fixe. Together, they read the Pathological

Fantastic

have been struggling against for the past few as a series of meticulous self-diagnoses tracing

days is worse this morning and I am incapable the unfolding narrative of his erotic fixation in

of carrying on a conversation of any reason- emotional and physiological detail. As we in-

ableness. An idée fixe is killing me . . . all my vestigate Berlioz’s own pathology, the ana-

muscles twitch like a dying man’s.”19 Berlioz, logous condition afflicting his symphonic

it seems, was suffering from the same affliction alter-ego comes into sharper focus. Disease

he ascribed to his symphonic protagonist—a itself—as theorized in early-nineteenth-century

malignant idée fixe triggering convulsive mus- France—provides a vital context in which to

cular tremors and precipitating a state of ner- consider the mechanisms of self-representation

vous malfunction. No longer an ailment con- at work in the Fantastique. Berlioz’s idée fixe

fined to the imaginary realm, mental fixation leads us inexorably outward, toward a web of

emerges here as a real illness with a set of literary, philosophical, and psychiatric dis-

concrete medical symptoms—an affliction that courses integral to the aesthetic construction

draws Berlioz’s “novel” closer to a “history,” of the Fantastique, while drawing us simulta-

and suggests that pathology itself mediated a neously inward toward the fundamental and

key intersection between the composer and his intimate processes of autobiographical construc-

programmatic alter ego. Berlioz’s self-descrip- tion at the heart of the composer’s fantastic

tion grounds fictional accounts of mental fixa- self-telling.

tion in quasi-scientific rhetoric, situating the

idée fixe as a diagnosable medical phenomenon The Trope of Pathology

and proposing a complex relationship between in the “Fantastic” Letters

physical and fantastic disease.

In fact, the malady plaguing both Berlioz and The evolution of the Symphonie fantastique

his symphonic hero had been familiar to doc- stretched over more than a year, during which

tors and romance readers alike since the first Berlioz’s correspondence is peppered with ref-

decade of the nineteenth century, and well theo- erences to a planned instrumental composition

rized in early psychiatric texts. Berlioz’s self- of “immense” proportions.20 Despite frequent

descriptions, scattered throughout his personal references to the work, Berlioz was unable to

correpondence during the gestation period of begin composition, paralyzed by melancholic

the Symphonie fantastique, borrow liberally anxiety, hallucinations, and even convulsions

from an evolving vocabulary of scientific lan- brought on (in part) by an unrequited passion

guage to describe the mental “aberration” that for Harriet Smithson. Indeed, the symphony

plays such a central role in his symphonic nar- was inextricably intertwined with Berlioz’s

rative. As we explore the intersection between amorous obsession; he claimed repeatedly that

science and fantasy at the heart of his fantastic the work would draw him nearer to his be-

tale, we begin to map “fiction” onto “real life” loved, allowing him to satisfy the relentless

and to uncover the medical underpinnings of craving of his idée fixe. His sufferings built to a

the composer’s program. His letters over the climax in the winter of 1830, but they had

course of 1829 and early 1830 are suffused with begun considerably earlier, the result of a seri-

20

David Cairns provides invaluable commentary on the

19

CG, I, 153. I am by no means the first to note Berlioz’s creative emergence of the Fantastic Symphony in his re-

reference to his own idée fixe (see, for instance, David view of Berlioz’s letters over the period 1829–30; see his

Cairns’s recent Berlioz, vol. 1: The Making of an Artist Making of an Artist, pp. 355–61. Here, I take the same

1803–1832 [Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of Cali- epistolary journey, although I am primarily interested in

fornia Press, 1999], p. 357), but the full medical and liter- documenting the evolution of Berlioz’s self-diagnosed idée

ary significance of the term has not, to my knowledge, fixe and examining links between pathology and creative

been brought to bear on either Berlioz’s biography or his impulse that permeate his self-accounts during this pe-

first symphony. riod.

215

This content downloaded from

130.253.26.76 on Thu, 03 Sep 2020 19:41:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

19 TH ous malady whose development he described layed a series of love letters to Harriet, but they

CENTURY

MUSIC in a series of letters to Edouard Rocher, Humbert failed to elicit a response. Even a note in En-

Ferrand, and Albert du Boys. glish proved unsuccessful and, after weeks of

Berlioz opened a letter to Rocher (11 January fruitless pursuit, Berlioz seemed reconciled with

1829) with the melancholy notion that he could his amorous failure, declaring “everything over”

write only of “suffering,” and of the “continu- in a miserable letter to Albert du Boys.22 But

ous alternation between hope and despair” pro- only days later, he renewed his efforts, hatch-

voked by his passion for Harriet Smithson. The ing a desperate plot to communicate with

composer’s lovesick distress mingled with a Harriet through the maître de la maison at her

gripping ambition to achieve “new things”; the Parisian residence. The results were disastrous:

torment born of his “overpowering passion” Harriet was both annoyed and frightened and,

was to be transmuted into revolutionary musi- in reply to Berlioz’s pleas, insisted brusquely

cal form, misery itself giving shape to his ideas: that the composer’s advances were unwanted,

that she “absolutely could not share his senti-

Oh, if only I did not suffer so much! . . . So many ments,” and indeed, that “nothing was more

musical ideas are seething within me[. . . .] There are impossible.”23 Il n’y a rien de plus impossible:

new things, many new things to be done, I feel it the phrase reverberates through Berlioz’s corre-

with an intense energy, and I shall do it, have no spondence in the following months as the mel-

doubt, if I live. Oh, must my entire destiny be en-

ancholic leitmotif of his idée fixe, yet even in

gulfed by this overpowering passion? . . . If on the

the face of Harriet’s explicit rejection, he con-

other hand it turned out well, everything I’ve suf-

fered would enhance my musical ideas. I would work tinued to refer to her as his darling, to speak of

non-stop . . . my powers would be tripled, a whole her love, and to anticipate their union.

new world of music would spring fully armed from Letters of this period seldom refer to Harriet

my brain or rather from my heart.21 by name; instead, Berlioz called her Ophélie, a

reference to the Shakespearean guise in which

In the months that followed, Berlioz’s obses- he first encountered her. For Berlioz, who had

sion with Harriet intensified; his letters docu- never exchanged a word with Harriet, the tragic

ment a series of convoluted communications heroine of Hamlet was more immediate than

with friends and acquaintances of the actress, the actress herself. In the composer’s imagina-

through whom he hoped to reach the object of tion, Harriet hovered between the fictional and

his infatuation. Via the English impresario, the actual, her theatrical personas accruing sub-

Turner—who chaperoned Smithson and her stance and agency in his letters. At times, Berlioz

mother on their European travels—Berlioz re- perceived her as a conflation of imaginary char-

acters: in an outburst to Ferdinand Hiller, he

wrote, “Oh Juliet, Ophelia, Belvidera, Jane Shore,

names which Hell repeats unceasingly.” 24

21

CG, I, 111. Translated by Cairns in The Making of an Harriet’s rejections were incapable of weaken-

Artist, p. 355. Ellipses without brackets are Berlioz’s; el-

lipses within brackets indicate omitted text in the quota- ing Berlioz’s passion, for, in his mind, she was

tions throughout this article. Berlioz’s fixation on Smithson, not a flesh-and-blood woman but the symbol of

which became intertwined with a Shakespearean obses- an ephemeral ideal—an imaginary perfection

sion, had begun some time before. He first encountered

both actress and English playwright in September of 1827,

when Harriet appeared as Ophelia in a production of Ham-

22

let at the Odéon Theater. Berlioz recalls the overwhelm- CG, I, 117 (2 March 1829). Berlioz’s love letters do not

ing emotional and psychological effect of the experience survive, but his Mémoires suggest that they were numer-

in his Mémoires, couching his description in unmistak- ous; indeed, Harriet finally instructed the maids at her

ably pathological terms: “A feeling of intense, overpower- Amsterdam hotel to stop delivering the composer’s amo-

ing sadness came over me, accompanied by a nervous con- rous pleas.

23

dition like a sickness, of which only a great writer on CG, I, 117. Berlioz’s letter to Du Boys describes a series

physiology could give any adequate idea. I lost my power of events stretching over several weeks, from the failure of

of sleep and with it all my former animation, all taste for his English letter to Harriet to his ill-fated interactions

my favorite studies, all ability to work. I wandered aim- with her Parisian landlord and subsequent despair.

24

lessly about the Paris streets and the neighboring plains” CG, I, 156 (3 March 1830). All are, of course, roles in

(trans. Cairns in The Memoirs of Hector Berlioz [London: which Smithson appeared on the Parisian stage at the height

Gollancz, 1969], pp. 95–96). of her fame.

216

This content downloaded from

130.253.26.76 on Thu, 03 Sep 2020 19:41:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

that, like the poetic vision of the symphony By June, Berlioz’s condition had worsened FRANCESCA

BRITTAN

itself, was as yet agonizingly beyond his reach. considerably. Suffering from physical weakness Berlioz and

Indeed, Berlioz’s idée fixe was intimately tied to and depression, he consulted a doctor, who di- the Pathological

Fantastic

his evolving creative process; the obsession mo- agnosed a nervous disorder brought on by emo-

tivated him toward “immense” musical thought tional strain:

and concentrated his compositional power. In

his letters, disease itself is figured as a generative My life is so painful to me that I cannot help but

force and a central impetus for the Fantastique: regard death as a deliverance. In the past days, I have

Berlioz tells Ferrand that “this passion will kill gone out very little, I could not abide it; my strength

me,” although, only a few letters earlier, he had disappears with an alarming rapidity. A doctor, whom

I consulted the day before yesterday, attributed the

assured his friend that “Ophelia’s love has in-

symptoms to fatigue of the nervous system caused

creased my powers a hundredfold.”25 The sym-

by an excess of emotion. He could also have added,

phony, it seems, was not merely generated by by a sorrow that is destroying me.28

Berlioz’s fixation, but promised to perpetuate it.

Again, to Ferrand, the composer wrote: “When I The baths and solitary rest prescribed by

have written an immense instrumental compo- Berlioz’s physician provided only temporary re-

sition, on which I am meditating, I will achieve lief. Ten days later, he complained of “anguish”

a brilliant success in her eyes.”26 and “terrible despair” sparked by Harriet’s de-

While goading him onwards, Berlioz’s fixation parture for London, linking the return of his

proved increasingly destructive to his emotional physical suffering to a familiar sense of isola-

and psychological health. In the 2 March letter tion, now coupled with a near-convulsive im-

to Albert du Boys, he was already reporting a pulse:

condition of intense misery and alienation from

the “physical and intellectual” worlds. Here we Now she’s left! . . . London! . . . Enormous success!

read of a sensation of utter isolation in which, . . . While I am alone . . . wandering through the

bereft of his rational faculties, he is abandoned streets at night, with a poignant misery which ob-

to the imaginative realm of “memory” and un- sesses me like a red-hot iron on my chest. I feel like

able to order his thoughts: rolling on the ground to try to alleviate it! . . . Going

out into society doesn’t help; I keep myself busy all

It is as though I am at the centre of a circle whose

circumference is continuously enlarging; the physi-

cal and intellectual world appear placed on this un- Berlioz,” Music & Letters 59 (1978), 33–48. Citing nervous

“exacerbation” (p. 40) as a condition permeating much of

ceasingly expanding circumference, and I remain Berlioz’s life, she identifies a more intense period of ill-

alone with my memory, and a sense of isolation ness surrounding the production of the Symphonie

which is always intensifying. In the morning when I fantastique, a work that “gives the fullest and purest ex-

wake from the nothingness wherein I am plunged pression of the mal d’isolement” (p. 46). But Ironfield gives

an aesthetic rather than physiological description of

during sleep, my spirit—which was so easily accus-

Berlioz’s condition; it is a vague pathology “perhaps liable

tomed to the ideas of happiness—awakes smiling; to some fairly prosaic medical explanation” (p. 40). Al-

this brief illusion is soon replaced by the atrocious though she identifies “love”—and even ideal fantasy—as

idea of reality which overwhelms me with all its the “fundamental element” (p. 45) of Berlioz’s malaise,

weight and freezes my entire being with a mortal Ironfield does not explore the psychiatric ramifications of

the composer’s idée fixe, a term that points toward a much

shudder. I have great trouble gathering my thoughts. more concrete species of nineteenth-century pathology.

[. . .] I have been forced to recommence this letter She posits a link between illness and creative impulse in

many times in order to arrive at the end.27 Berlioz’s psychology, but resists the suggestion that the

composer might have regarded disease itself as an impetus

for composition, claiming that “it is no longer fashionable

to attribute genius to some abnormality of temperament,

imbalance, or even madness” (p. 40). While I agree that

associations between mental aberration and creative vi-

25

CG, I, 126 (3 June 1829) and I, 114 (18 Feb. 1829) respec- sion may have fallen out of fashion today, such connec-

tively. tions were alive and well in the early nineteenth century

26

CG, I, 126. and, as I shall claim, underpin Berlioz’s Fantastic Sym-

27

CG, I, 117. Susan Ironfield examines Berlioz’s lifelong phony as well as permeating many aspects of Romantic

tendency toward melancholy and mal de l’isolement in literary and medical culture.

28

“Creative Developments of the ‘Mal de l’Isolement’ in CG, I, 127 (14 June 1829); to Edouard Rocher.

217

This content downloaded from

130.253.26.76 on Thu, 03 Sep 2020 19:41:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

19 TH day long but I can’t take my mind off her. I haven’t Here Berlioz suggested that anxiety and emo-

CENTURY seen her for four months now[. . . .] You talk to me of

MUSIC tional excess were fundamental aspects of his

my parents, all I can do for them is to stay alive; and character—they “come from the way [he is]

I’m the only person in the world who knows the made”—and have tormented him since early

courage I need in order to do this.29

youth. His tendency toward melancholy, he

explained, was fueled by an imagination so vivid

February 1830 found the composer in a “fright-

that he experienced “extraordinary impres-

ful state of nervous exaltation” accompanied

sions” akin to opium hallucinations. Berlioz’s

by convulsive muscle tremors. The cause of his

fantastic interior realm (ce monde fantastique),

misery was the obsessive passion that Berlioz

according to this letter, had only grown in

now identified specifically as an idée fixe (see

breadth and power as he aged, exerting increas-

p. 215)—a diagnosis that located his illness

ing influence over his rational faculties. In-

squarely within the realm of psychiatric dis-

deed, he described his fantasy world as a darkly

course and, as we shall see, referred to a spe-

pathological place marked by disorientation and

cific category of known mental disorders.30

excess: it had become “a real malady” (une

Plans for the Symphonie fantastique contin-

véritable maladie). Illusory images and magni-

ued to progress, despite Berlioz’s distress. As

fied passions now drove him into a convulsive

early as 6 February, he informed Ferrand that

state close to hysteria; he almost “shouts and

“the whole thing is in my head,” although he

rolls on the ground.” Only music could harness

had not been able to write it down. The sym-

and control his wayward fantasy, and yet even

phony would trace the course of Berlioz’s “in-

the enormous symphony in gestation was un-

fernal passion”—not simply his infatuation with

able to draw his mind away from destructive

Harriet Smithson, but the obsessive illness that

imaginings:

had resulted. Nervous overstimulation, trem-

bling, and a painful sensitivity of all the facul- I wish I could also find a remedy to calm the feverish

ties began to torment the composer: “I listen to excitement which so often torments me; but I shall

the beating of my heart, its pulsations shake never find it, it comes from the way I am made. In

me like the pounding pistons of a steam en- addition, the habit I have got into of constantly

gine. Every muscle in my body quivers with observing myself means that no sensation escapes

pain. . . . Futile! . . . Horrible!” At times he me, and reflection doubles it—I see myself in a mir-

seemed to lapse into a semi-delirious state; he ror. Often I experience the most extraordinary im-

wrote of “clouds charged with lightning” that pressions, of which nothing can give an idea; ner-

“rumbled” in his head.31 A longer and more vous exaltation is no doubt the cause, but the effect

is like opium intoxication.

detailed letter to his father followed several

Well, this imaginary world (ce monde fantastique)

weeks later, in which Berlioz interrogated not

is still part of me, and has grown by the addition of

only the immediate symptoms of his illness all the new impressions that I experience as my life

but also its preconditions. As he implied in a goes on; it’s become a real malady (c’est devenu une

later letter to Rocher, Berlioz was reluctant to véritable maladie). Sometimes I can scarcely endure

reveal to his father that Harriet was the focus this mental or physical pain (I can’t separate the

of his “cruel maladie morale” and omitted men- two), especially on fine summer days when I’m in an

tion of the actress in the diagnosis of his afflic- open space like the Tuileries Garden, alone. Oh then

tion that he sent to Papa.32 (as M. Azaïs rightly says) I could well believe there is

a violent “expansive force” within me.33 I see that

wide horizon and the sun, and I suffer so much, so

29

CG, I, 129 (25 June 1829); to Rocher. Translated by Roger

Nichols in Selected Letters of Berlioz, ed. Hugh Macdonald

33

(New York: Norton, 1995), pp. 55–56. Pierre-Hyacinthe Azaïs (1766–1845): a philosopher best

30

CG, I, 153 (early Feb. 1830). known for his treatise Des compensations dans les

31

CG, I, 152 (6 Feb. 1830). destinées humaines (also known as the Traité des com-

32

CG, I, 165 (5 June 1830). Berlioz reminds Edouard Rocher pensations) (Paris: Firmin Didot; Garney and Leblanc, 1809)

that his father must know nothing of his attachment to in which he proposed that all experience could be under-

Harriet: “Mais que mon père n’apprenne rien de ma cruelle stood in terms of an interaction between expansive and

maladie morale pour H. Smithson: c’est inutile.” compressive forces.

218

This content downloaded from

130.253.26.76 on Thu, 03 Sep 2020 19:41:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

much, that if I did not take a grip of myself I should tal and emotional torment, yet his “autobio- FRANCESCA

shout and roll on the ground. I have found only one BRITTAN

graphical” hero traversed a darker path: the Berlioz and

way of completely satisfying this immense appetite jeune musicien of the Fantastique not only the Pathological

for emotion, and that is music. Without it I am Fantastic

attempted suicide but also imagined, under the

certain I could not go on living.34

influence of opium, that he had killed his be-

loved. David Cairns has recently suggested that

Reports of anguished hallucination followed:

the news of Harriet’s alleged indiscretions was

Berlioz told Hiller that he “saw Ophelia” shed-

not a deciding factor in the creation of the

ding tears and “heard her tragic voice,” going

grotesque finale of the work, claiming that “the

on to describe a series of odd imaginings in

‘plan of the symphony’ had been in existence

which Beethoven “looked at him severely” and

for some while before the discovery in ques-

Weber “whispered in [his] ear like a familiar

tion.”36 In Cairns’s view, to argue that petty

spirit.” Suddenly breaking off, he acknowledged

“revenge” was a motivating force in the cre-

that his behavior was bordering on madness:

ation of Berlioz’s dark narrative is to misunder-

“All this is crazy . . . completely crazy, for a

stand the composer’s musical and personal mo-

man who plays dominoes in the Café de Régence

tives. What, then, was the source for the

or for a member of the Institut. . . . No, I want

composer’s murderous plot twist and sinister

to live . . . once more.” The letter dissolves into

alter ego? Why does his hero’s idée fixe lead to

near-incoherence as Berlioz returns again to his

more dangerous and ominous imaginings than

ideé fixe: “I’m beside myself, quite incapable of

those that Berlioz was ascribing to himself?

saying anything . . . reasonable. . . . Today it is a

Contextualization and partial elucidation of

year since I saw HER for the last time. . . .

both Berlioz’s obsessive illness and its reconfi-

Unhappy woman, how I loved you! I love you,

guration in the program of the Fantastique is

and I shudder as I write the words.” A desper-

to be found—I argue—in the realm of medicine

ate attempt to locate his obsession in the past

and, more specifically, in the writings of early-

tense fails, the fixation quickly reasserting it-

nineteenth-century psychiatrists, whose new

self in the present. As the letter draws to a

and sensational diagnoses of madness had far-

close, Berlioz seems to sink into despondency,

reaching effects in both scientific and artistic

unable to master his ravaging imagination: “I

circles. The writings of the early médecins-

am a miserably unhappy man, a being almost

aliénistes (doctors of mental medicine) point

isolated from the world, an animal burdened

toward a specific diagnosis of the maladies af-

with an imagination that he cannot endure,

flicting the composer and his musical hero,

devoured by a boundless love which is rewarded

providing a richly theorized backdrop for the

only by indifference and contempt.”35

debilitating and potentially fatal idée fixe. As

Desperate for a reprieve from his pathologi-

we shall see, the link between Berlioz’s famous

cal fantasies, Berlioz suddenly received it: slan-

fixation and early French psychiatric theory

derous reports of Harriet’s moral character

has already been noted, though not explored at

reached the composer in March 1830, tempo-

length, in recent scholarship within the field of

rarily weakening the grip of his idée fixe and

medical history.

allowing him to refocus his imaginative pow-

ers. Berlioz poured out the tale of his suffering

Early Psychiatry and the Formulation

and obsession in musico-literary form, describ-

of a “Monomania” Diagnosis

ing an amorous illness taken directly from per-

sonal experience. His symphonic narrative reso-

The late eighteenth and early nineteenth cen-

nated clearly with the records of his own men-

turies saw a burgeoning interest in psychologi-

cal health in French medical thought, as physi-

cians linked to the circle of the Idéologues

34

CG, I, 155 (19 Feb. 1830); translation adapted from David began to expand the definition of medicine to

Cairns, The Making of an Artist, pp. 357–58.

35

CG, I, 156 (3 March 1830); quoted passages rely on the

translation by Roger Nichols, in Selected Letters of Berlioz,

36

pp. 66–67. Cairns, The Making of an Artist, p. 361.

219

This content downloaded from

130.253.26.76 on Thu, 03 Sep 2020 19:41:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

19 TH include study of both le moral and le phy- hysterie, hallucination, and idées fixes perme-

CENTURY

MUSIC sique.37 Recent studies of the emerging psychi- ated medical and legal texts and soon filtered

atric profession in early-nineteenth-century into popular discourse. Through the early 1800s,

France and elsewhere—work by Jan Goldstein, psychiatry evolved as an autonomous and in-

Ian R. Dowbiggin, and Elizabeth A. Williams— creasingly important medical field, and the new

inform us that a new “medicine of the imagi- médecin-aliéniste as a powerful figure both in

nation” was rendering mental functions and the scientific and public realms.40

even the mechanisms of sentiment accessible Foremost among doctor-psychiatrists of

to rational examination, and bringing insanity the new school was Jean-Etienne-Dominique

to the forefront of medical attention.38 Pioneer- Esquirol, a student of the revered Pinel, who

ing work by P.-J.-G. Cabanis and Phillipe Pinel devoted his long career almost exclusively to

at the turn of the century proposed a complex the study, definition, and systematic classifica-

symbiosis between “internal impressions” of tion of madness, becoming the principal

the imagination and physical sensations trans- médecin-aliéniste of the first half of the cen-

mitted via the nervous system, laying the theo- tury. Among Esquirol’s chief contributions was

retical foundation for the first generation of the theorization of a new mental malady called

psychiatrists.39 Mental disorders (maladies mo- “monomania,” which he first identified around

rales) began to be described and defined with a 1810 and later defined and classified in an 1819

newly precise body of language; references to paper published in the Dictionaire des sciences

médicales.41 Here, as Goldstein explicates in

her chapter on “Monomania,” Esquirol situ-

37

ated monomanie as a circumscribed type of

These are terms that, as Jan Goldstein points out in her

invaluable study, Console and Classify: The French Psy- mania involving a “partial deliria” or localized

chiatric Profession in the Nineteenth Century (Cambridge: “disorder of the understanding.” Classing it as

Cambridge University Press, 1987), were first paired in a disorder of the nervous system, he identified

Pierre-Jean-George Cabanis’s 1802 treatise, Rapports du

physique et du moral de l’homme. Cabanis and members monomania’s primary symptom as the patho-

of his intellectual circle were termed Idéologues for their logical fixation on a single idea—an idée fixe.42

interest in idéologie—the “science of ideas”—which en-

couraged a merger of medical discourse and philosophical

method (see pp. 90–91 for further clarification). Goldstein

40

explores not only the philosophization of medical practice For a discussion of “hallucination”—a new term in the

that began during Cabanis’s career, but its evolution into early nineteenth century—and “hysterie,” see Goldstein,

“an all-embracing science of man” (p. 49), which, extend- Console and Classify, pp. 263; 370; 323–31 and Williams,

ing the sensationalist psychology of the Enlightenment, Physical and the Moral, pp. 252–53; see also Goldstein

interrogated both physical and mental functions (see pp. Console and Classify, p. 99, n. 126 for the etymology of

49–55). “aliénation mentale,” a term that led to the later designa-

38

“Medicine of the imagination” was a broad designation tion “médecin-aliéniste.” I am most concerned here, of

that applied both to speculative practices including mes- course, with the medical implications of the term “idée

merism and to the newly rigorous and “scientific” field of fixe,” which I explore in greater detail over the following

French psychiatry; see Goldstein, Console and Classify, several pages.

41

pp. 54; 78–79. During the early nineteenth century, simi- Goldstein, Console and Classify, pp. 155–56. See also

lar developments in “imaginative” medicine were under- her full chapter on monomania (pp. 152–96)—the most

way in Germany and England, although French physicians comprehensive study of the subject available, and one that

played a central role in establishing the new science. In must serve as a starting point in any exploration of

addition to Goldstein, the following sources have proven Esquirol’s disease. This section relies significantly on her

useful in my own work: Elizabeth Williams, The Physical historical narrative, while the following sets out new evi-

and the Moral: Anthropology, Physiology, and Philosophi- dence garnered from mid-century musical and literary

cal Medicine in France 1750–1850 (Cambridge: Cambridge sources.

42

University Press, 1994); and Ian Dowbiggin, Inheriting Mad- Esquirol, “Monomania,” Dictionaire des sciences

ness: Professionalization and Psychiatric Knowledge in medicales, vol. 34 (1819), pp. 117–22; quoted in Goldstein,

Nineteenth-Century France (Berkeley and Los Angeles: Console and Classify, pp. 156–57. The terms monomanie

University of California Press, 1991). and idée fixe were coined well before 1818. “Monomania”

39

As Goldstein points out, Pinel’s 1801 Traité médico- appears in Esquirol’s early writings, ca. 1810; idée fixe

philosophique sur l’aliénation mentale, ou la manie—the dates from the same period in both Esquirol and in Gall

first comprehensive treatise on insanity—elaborated on and Spurzheim’s commentary on Esquirol, contained in

Cabanis’s notion of “internal impressions” or “instincts” their treatise on phrenology, Anatomie et physiologie du

that, in conjunction with reason, constituted the newly système nerveaux en général et du cerveau en particulier

important realm of “le morale” (Console and Classify, see (Paris: F. Schoell, 1812) (see Goldstein, Console and Clas-

pp. 50; 71). sify, p. 153, n. 6; p. 155, n. 21).

220

This content downloaded from

130.253.26.76 on Thu, 03 Sep 2020 19:41:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Monomaniacs were consumed by one thought, Esquirol’s 1838 treatise warrants closer at- FRANCESCA

BRITTAN

idea, or plan of action, a state of mental fixa- tention, for it was here that he synthesized his Berlioz and

tion producing an “energetic” effect while also earlier writing and research on monomania and the Pathological

Fantastic

causing “nervous exaltation,” “illusions,” fe- described certain subclassifications of mental

verish thought patterns and—in advanced fixation in greater detail. Drawing on a series of

cases—hallucinations, convulsions, and disturb- case studies, he detailed the symptoms and

ing dreams. Sufferers might also experience effects of theomania, incendiary monomania,

melancholic symptoms, the frustration of their monomania from drunkenness, and—most im-

desires leading to depression, despair, and sor- portant to our investigation—erotic monoma-

rowful withdrawal.43 nia.46 Erotic fixation (or erotomania) was a spe-

According to Esquirol’s later treatise on in- cies of obsession characterized by an “over-

sanity—Des maladies mentales: considérées abundance of passion” (un amour excessif) in

sous les rapports médical, hygiénique et which “the affections take on the character of

médico-légal (1838)—monomaniacs were those monomania; that is to say, they are fixed and

who “appear[ed] to enjoy the use of their rea- concentrated upon a single object.”47 Esquirol

son, and whose affective functions alone distinguished erotomania from the languor and

seem[ed] to be in the wrong.”44 In all areas out- “soft revery” (douce rêverie) of youthful love,

side of their fixation, they reasoned logically; which he designated simply as melancholy, al-

indeed, Esquirol suggested that the minds most though—like Berlioz—he recognized early bouts

susceptible to idées fixes were those endowed of amorous depression as frequent forerunners

with marked intelligence, sensitivity, and vivid of more serious nervous disorder. Despite its

imagination. Such persons were given to ambi- romantic nature, erotomania was not to be con-

tious or “exaggerated” projects and fantastic fused with the shameful and humiliating con-

imaginings, often allowing setbacks and frus- dition of nymphomania for it intensified “the

trations to drive them to mental instability: ardent affections of the heart” (les affections

vives du coeur) without invoking unchaste de-

Sanguine and nervous-sanguine temperaments, and sires: “The erotomaniac neither desires, nor

persons endowed with a brilliant, warm and vivid dreams even, of the favors to which he might

imagination; minds of a meditative and exclusive aspire from the object of his insane tenderness;

cast, which seem to be susceptible only of a series of his love sometimes having for its object, things

thoughts and emotions; individuals who, through

inanimate.”48

self-love, vanity, pride, and ambition, abandon them-

Esquirol reported that some men were seized

selves to their reflections, to exaggerated projects

and unwarrantable pretensions, are especially dis- with monomaniacal passion for mythical char-

posed to monomania.45 acters, imaginary creatures, or women they had

43

These are symptoms described in Esquirol’s later trea- par ambition, s’abandonnent à des pensées, à des projets

tise, Des maladies mentales: considérées sous les rapports exagérés, à des prétentions outrées sont, plus que les autres,

médical, hygiénique et médico-légal, vol. 2 (Paris: Baillière, disposés à la monomanie” (ibid., p. 29). See also Goldstein’s

1838), in which he consolidated his earlier writings on discussion of monomanie ambitieuse, Console and Clas-

monomania, detailing case studies gathered over several sify, pp. 160–61.

46

decades of work in Parisian asylums and hospitals; see pp. Not all of these subtypes of monomania were new to

1–4. These and subsequent quotations are given in transla- Esquirol’s diagnosis, but they were presented in 1838 with

tions adapted from those of Raymond de Saussure, in Men- fresh evidence. Goldstein draws our attention to the “spe-

tal Maladies: A Treatise on Insanity; A Facsimile of the cific forms of monomania,” including erotomania (Con-

English Edition of 1845 (New York: Hafner, 1965). sole and Classify, p. 171), although she does not explore

44

“On a classé parmi les maniaques des individus qui monomanie érotique in any detail.

47

paraissent jouir de leur raison; mais dont les fonctions “[Dans la manie érotique], les affections ont le caractère

affectives seules semblent lésées” (Esquirol, Des maladies de la monomanie, c’est-à-dire qu’elles sont fixes et

mentales, p. 94). concentrées sur un seul objet” (Esquirol, Des maladies

45

“Les tempéramens sanguins et nervoso-sanguins, les mentales, p. 47).

48

individus doués d’une imagination brillante, vive, exaltée; “L’érotomaniaque ne desire, ne songe pas même aux

les esprits méditatifs, exclusifs, qui ne semblent faveurs qu’il pourrait prétendre de l’objet de sa folle

susceptibles que d’une série d’idées et d’affections; les tendresse, quelquefois même son amour a pour objet des

individus qui, par amour-propre, par vanité, par orgueil, êtres inanimés” (ibid., p. 33).

221

This content downloaded from

130.253.26.:ffff:ffff:ffff on Thu, 01 Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

19 TH never met but to whom they assigned all man- system of classifications for aliénation mentale

CENTURY

MUSIC ner of physical and moral perfections. These to the forefront of the psychiatric field. Teach-

unfortunates were consumed by fixated devo- ers of médecine mentale in Paris focused heavily

tion and “pursued both night and day by the on the concept of monomania, and a spate of

same thoughts and affections,” although their supporting research began to appear in the early

sentiments were directed toward an unattain- 1820s. By 1826 monomania “was the single

able object: most frequent diagnosis made of patients en-

tering Charenton,” becoming a virtual epidemic

While contemplating its often imaginary perfections, that dominated medical debate and captured

they are thrown into ecstasies. Despairing in its the imagination of the public at large.51 In Pari-

absence, the look of this class of patients is dejected; sian salons, mental illness and psychiatric

their complexion becomes pale; their features change, theory were fashionable concerns, and refer-

sleep and appetite are lost: these unfortunates are

ences to monomaniacal fixation began to sur-

restless, thoughtful, greatly depressed in mind, agi-

face in journalism, fiction, and even visual cul-

tated, irritable and passionate, etc. ( . . . ) their aug-

mented muscular activity is convulsive in its char- ture (notably, in the series of “monomaniac”

acter.49 portraits painted by Géricault in the early

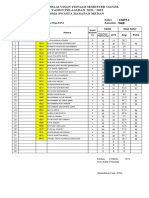

1820s); see plate 1.52 When, in 1830, Berlioz

Animated, “expansive,” and often frenetically assigned his symphonic hero the symptoms of

lively, erotomaniacs were “ordinarily exceed- monomania—a melancholic-frenetic delirium

ingly loquacious, and always speaking of their characterized by an idée fixe—he was not de-

love.” They lived in a constant state of emo- scribing a vague or imaginary nervous disorder,

tional unrest resulting in nervous pains, fever, but a maladie morale that would have been

convulsion, and often “irrational conversation” easily identified by many of those in the

(conversation desordonée); Esquirol described concertgoing public. As Martina van Zuylen

their tortured passions, noting that “fear, hope, has also noted, the composer’s reported symp-

jealousy, joy, fury, seem unitedly to concur, or toms bear a clear resemblance (both rhetorical

in turn, to render more cruel the torment of and substantive) to Esquirol’s general delinea-

these wretched beings,” who were “capable of tion of monomania and—I argue—to the more

the most extraordinary, difficult, painful and specific diagnosis of the erotomaniac. Indeed,

strange actions.”50 Personalities particularly sus- it could well be that Berlioz was constructing

ceptible to erotomania—those with an intense

emotional capacity—suffered an exaggeration

of their natural passions, which, in serious cases, 51

Goldstein, Console and Classify, p. 154. See also p. 153,

led to delirium and suicidal despondency. where she also notes references to “monomania” in writ-

As Goldstein has noted, Esquirol’s monoma- ing by both Tocqueville and Balzac in the 1830s and ob-

nia diagnosis created a significant stir in medi- serves that the term “had already percolated down to the

nonmedical French intelligentsia and been incorporated

cal circles, catapulting both the doctor and his into their language by the late 1820s.” As I have already

shown, references to idées fixes began to appear in fictional

writing as early as 1814 both in and outside of France; this

evidence suggests a somewhat earlier popularization of

49

“En contemplation devant ses perfections souvent Esquirol’s terminology and—as the final sections of this

imaginaires; désespérés par l’absence, le regard de ces article argues—a more pervasive intertwining of French

malades est abattu, leur teint devient pâle, leurs traits medical theory and early Romantic literature.

52

s’altèrent, le sommeil et l’appétit se perdent: ces Goldstein lists a series of articles on monomania pub-

malheureux sont inquiets, rêveurs, désespérés, agités, lished in leading French journals through the mid-late

irritables, colères, etc. ( . . . ) leur activité musculaire 1820s, including pieces in the Globe, Journal des Débats,

augmentée, a quelque chose de convulsif” (ibid., pp. 33– Figaro, and Mercure de France aux XIX siècle (see Console

34). and Classify, p. 184, nn. 114–16). To these, I can add two

50

“Ces malades sont ordinairement d’une loquacité slightly later articles: “Les Monomanies,” Figaro, 13 Oc-

intarissable, parlant toujours de leur amour (. . .) L’espoir, tober 1833, and “Monomania,” Figaro, 13 September 1834.

la jalousie, la joie, la fureur, etc., semblent concourir toutes On Géricault’s portraits of monomaniacs, see Margaret

à-la-fois ou tour-à-tour pour rendre plus cruel le tourment Miller, “Géricault’s Paintings of the Insane,” Journal of

de ces infortunés . . . ils sont capables des actions les plus the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 4 (1941), 151–63.

extraordinaires, les plus difficiles, les plus pénibles, les Goldstein reproduces one of these portraits, “The Physiog-

plus bizarres” (ibid., p. 34). nomy of Monomania” [ca. 1822] in plate 3, p. 223.

222

This content downloaded from

130.253.26.76 on Thu, 03 Sep 2020 19:41:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Obvious links between the erotomania diag- FRANCESCA

BRITTAN

nosis and Berlioz’s illness are underscored by a Berlioz and

case study published in Esquirol’s 1838 trea- the Pathological

Fantastic

tise. Following his general definition of erotic

fixation, the doctor recounted the tale of a young

man “of a nervous temperament and melan-

choly character” (d’un tempérament nerveux,

d’un caractère mélancolique) who moves to

Paris in the hopes of advancing his career. While

in the capital, he “goes to the theatre, and

conceives a passion for one of the most beauti-

ful actresses of [the Théâtre] Feydeau, and be-

lieves that his sentiments are reciprocated. From

this period he makes every possible attempt to

reach the object of his passion.”54 The young

man talks constantly of his beloved, imagines

their blissful union, and devotes himself fully

to the pursuit of his idée fixe. He waits for the

actress at her dressing room, goes to her lodg-

ings, and attends her performances assiduously:

“Whenever Mad . . . appears upon the stage, M.

. . attends the theatre, places himself on the

fourth tier of seats opposite the stage, and when

Plate 1: Theodore Géricault, “Monomanie du this actress appears, waves a white handker-

vol” (ca. 1822). Oil on canvas. Musée des chief to attract her attention.”55 The actress

Beaux-Arts, Gand (Bernard Noél, Géricault rebuffs his advances, refuses to acknowledge

[Paris: Flammarion, 1991]). his letters and visits, and expresses her annoy-

ance with his constant attentions. Neverthe-

less, the young man insists that she loves him,

his own erotic disorder and that of his “fantas- that her rough treatment is only a ruse to de-

tic” protagonist according to the detailed de- ceive others, and that they will soon be united.

scriptions of manic fixation saturating scien- Eventually, he begins to experience delusions,

tific and journalistic writing of the period. Once believing that he hears the voice of his beloved

a medical student himself, and the son of a and imagining that she is in the house. Esquirol

doctor, Berlioz would have been better equipped reported that his obsession intensified over

than many of his contemporaries to follow de- time, becoming an all-consuming and danger-

velopments in the psychiatric field, and was ous fixation despite the fact that he reasoned

likely to have been aware of the popular debate logically on all other subjects.

surrounding Esquirol’s new disease.53

bothto his idée fixe and his tendency toward dark depres-

53

Goldstein notes, in passing, Berlioz’s use of the term sion (pp. 9–10). These references, though brief, point to-

idée fixe in the Symphonie fantastique (Console and Clas- ward the broad medical implications of Berlioz’s symphonic

sify, p. 155, n. 21), as does Stephen Meyer who, in a foot- program and suggest that a more detailed exploration is

note to his discussion of monomania among Marschner’s warranted.

54

operatic villains, identifies the Symphonie fantastique as “Il va au spectacle et se prend de passion pour une des

“the most famous musical expression” of “fixed delusion” plus jolies actrices de Feydeau, et se croit aimé; dès-lors, il

(see “Marschner’s Villains, Monomania, and the Fantasy fait toutes les tentatives possibles pour arriver jusqu’à

of Deviance,” Cambridge Opera Journal 12/2 [2000], 115, l’objet de sa passion” (Esquirol, Des maladies mentales,

n. 15). More recently, Martina van Zuylen, in the intro- p. 37).

55

duction to her study Monomania: The Flight from Every- “Chaque fois que Mad . . . joue, M . . . se rend au spec-

day Life in Literature and Art (Ithaca: Cornell University tacle, se place au quatrième vis-à-vis la scène, et lorsque

Press, 2005) notes that Berlioz “was the first artist to make l’actrice paraît, il secoue un mouchoir blanc pour se faire

music and monomania coincide,” drawing our attention remarquer” (ibid., pp. 37–38).

223

This content downloaded from

130.253.26.76 on Thu, 03 Sep 2020 19:41:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

19 TH Here we find a striking parallel to Berlioz’s though this language does not strike a particu-

CENTURY

MUSIC illness—so much so, that one wonders whether lar chord with the modern reader, some sectors

erotomania for Parisian actresses was a com- of Berlioz’s audience may have recognized “re-

mon malady. As with Esquirol’s young patient, ligious consolations” as a standard type of

Berlioz developed an idée fixe for a lady of the remède morale administered to the insane. In

theater to whom he had not even been intro- Goldstein’s chapter entitled “Religious Roots

duced, attended her performances compulsively, and Rivals,” she examines “the moral treat-

lavished her with unwanted attention, and be- ment as religious consolation,” tracing an in-

lieved stubbornly that he would be united with tertwining of medical and spiritual cures in

the object of his devotions. His passion was psychiatric discourse of the period. She shows

directed toward a fictional and therefore unat- that many religious orders active in hospitals

tainable character: it was suffused with the advocated a special branch of douce remède

quality of rapturous worship rather than lusty known as consolation religieuse—a gentle moral

amour for a woman of the flesh. As Berlioz’s intervention in which “sweet,” tender, and

idée fixe escalated, he demonstrated the wildly courteous treatment encouraged lunatics to “re-

“expansive” energy and tortured passions that turn to themselves.”58 The consolation method

Esquirol described, as well as the delusional, proved considerably successful and was em-

convulsive, and finally suicidal symptoms as- ployed by medical as well as spiritual practitio-

sociated with manic fixation. It is hardly nec- ners in Paris through the first half of the cen-

essary to enumerate the connections between tury. Berlioz’s reference to tenderness and con-

Berlioz’s pathology and Esquirol’s disease: we solations religieuses may have been an acknowl-

are left with little doubt that, in the composer’s edgment of such moral remedies as popular

case, “erotic monomania” would have been the treatments in insanity cases. The melancholy

psychiatric diagnosis of his own time. monomaniac of his symphonic program would

Painting, writing, and music were often pre- have been a prime candidate for religious

scribed as therapeutic activities for monomani- therapy, although, as his narrative progresses,

acs. Such intellectual-emotional remedies fell the hero’s disorder threatens to degenerate into

into the broad category of “moral treatments,” a more dangerous, less manageable condition—

which were distinguished from purely physical a subtype of manic fixation in which passion-

cures including baths, purging and bleeding.56 ate brooding was replaced by violent and invol-

When Berlioz consulted a doctor, as he described untary action.59

in letters to Rocher and Ferrand, the medécin Certainly, not all the manifestations of mo-

diagnosed a nervous disorder and prescribed nomania were as pathetically appealing as

physical remedies including purifying baths and erotomania; an 1825 pamphlet published by

quiet rest. But Berlioz’s symphonic alter ego in

the Fantastique does not mention undergoing

such pragmatic treatments; rather, in the wake 58

Goldstein, Console and Classify, pp. 197–225; the above

of his “melancholy reverie” and “frenzied pas- quotations are taken from pp. 200–02. Goldstein points to

sions,” he describes “religious consolations” a substantial body of literature on “religious consolation,”

(consolations religieuses), which are preceded notably Xavier Tissot’s Manuel de l’hospitalier (1829),

which was well known to doctors and clergy alike.

by tears and a “return to tenderness.”57 Al- 59

Barzun suggests that, since Berlioz considered himself an

atheist during his early years in Paris, the religioso section

of the Fantastique’s first movement, and parallel refer-

ence to consolations religieuses in the revised program,

56

Remèdes moraux were described at length in Pinel’s “should be a further warning against literalism in discuss-

Traité and prescribed by Esquirol and members of his ing the relation between art and life”; see Berlioz and the

school. Dowbiggin discusses both the early implementa- Romantic Century (Boston: Little, Brown and Company,

tion of such remedies among French psychiatrists and their 1950; 3rd edn. New York: Columbia University Press,

later rejection by François Leuret and his followers (see pp. 1969), I, 163, n. 27. I propose, however, that Berlioz was

10, 38–53). See also Goldstein, Console and Classify, pp. not depicting his own religious sentiment but referencing

72–89. a remède morale that would have been standard treatment

57

This portion of the program, as well as the corresponding for an erotic monomaniac; such a reading incorporates the

religioso section of the first movement of the symphony, religioso section as a logical part of the symphony’s psy-

were added during Berlioz’s tenure in Italy in 1831. chiatric narrative.

224

This content downloaded from

130.253.26.76 on Thu, 03 Sep 2020 19:41:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Esquirol’s student Etienne-Jean Georget iden- medical, and social ramifications of the dis- FRANCESCA

BRITTAN

tified a sinister species of fixation called ease.63 Crowds gathered to witness court pro- Berlioz and

monomanie-homicide (homicidal monomania), ceedings, consuming each new tale of “fixated” the Pathological

Fantastic

which, characterized by a sudden “lesion of the murder with greater relish and rendering homi-

will,” drove otherwise sane persons to commit cidal monomania a profoundly fashionable dis-

murderous crimes.60 Although Georget argued order whose wide publicity (according to

that homicidal fixation might happen sponta- Esquirol) encouraged a spate of “imitative”

neously and without prior symptoms, other doc- murders: “A woman cuts off the head of a child

tors held that murderous monomania was pre- whom she scarcely knew, and is brought to

ceded by a set of telltale signs: strange “inter- trial for it. The trial is very extensively pub-

nal sensations,” “extreme misery,” “an idée lished, and produces, from the effects of imita-

fixe” or “an illusion, a hallucination, or a pro- tion, many cases of homicidal monomania with-

cess of false reasoning” (une illusion, une hal- out delirium.”64 Self-perpetuating and increas-

lucination, un raisonnement faux).61 Oddly, ac- ingly rampant, homicidal madness held the pub-

cording to Georget, homicidal monomaniacs lic in a state of horrified and titillated suspense

were often “compelled to kill the persons they as they waited for the next monomaniac to

loved the most”: his case studies (some bor- strike.

rowed from Pinel) record children killing their There is little surprise, then, that Berlioz

siblings, mothers their children, and husbands created a hero whose fixated passions evolve

their wives.62 Such murderers, he argued, were into gruesomely murderous imaginings; his

neither monsters nor criminals but sufferers symphonic narrative capitalizes unashamedly

from a terrible mental affliction—unfortunates on popular fascination with criminal madness.

who could neither prevent nor explain their The grisly plot twist in the final two sections

actions. of Berlioz’s program suggests that his protago-

As Goldstein informs us, monomanie homi- nist not only suffers from erotomania, but is

cide began to feature regularly as a defense in teetering dangerously on the edge of homicidal

criminal trials through the mid-1820s, spark- monomania. Succumbing to suicidal despair,

ing widespread debate surrounding the legal, the jeune musicien poisons himself with opium,

and—in a nightmarish hallucination—dreams

that he has killed his beloved and is on trial for

60

murder. All this resonates unmistakably with

E.-J.- Georget, Examen médical des procès criminels des

nommés Léger, Feldtmann, Lecouffe, Jean-Pierre et the theories of Esquirol, who later noted that

Papavoine, dans lesquels l’aliénation mentale a été monomaniacs who had committed murder

alléguée comme moyen de défense, suivi de quelques “confessed to me that ideas of homicide tor-

considérations médico-légales sur la liberté morale [A

medical examination of the criminal trials of Léger, mented them during their delirium, particu-

Feldtmann, Lecouffe, Jean-Pierre et Papavoine, in which larly at the commencement of their disorder.”65

mental illness was proposed as a means of defense, fol- Both Berlioz and his “fantastic” alter-ego mani-

lowed by some medico-legal considerations surrounding

moral liberty] (Paris: Migneret, 1825). I rely here both on fest many of the symptoms cited by Esquirol as