Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Shift Work in Nursing: Is It Really A Risk Factor For Nurses' Health and Patients' Safety?

Shift Work in Nursing: Is It Really A Risk Factor For Nurses' Health and Patients' Safety?

Uploaded by

Maria0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

21 views9 pagesOriginal Title

out

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

21 views9 pagesShift Work in Nursing: Is It Really A Risk Factor For Nurses' Health and Patients' Safety?

Shift Work in Nursing: Is It Really A Risk Factor For Nurses' Health and Patients' Safety?

Uploaded by

MariaCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 9

Hanna Admi

Orna Tzischinsky

Rachel Epstein

Paula Herer

Peretz Lavie

Shift Work in Nursing: Is it

Really a Risk Factor for Nurses’

Health and Patients’ Safety?

HIFT WORK IS NOW A MAJOR fea-

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

There is evidence in the scientific lit-

erature of the adverse physiological

and psychological effects of shift

work, including disruption to biologi-

Shift work by itself was not found to

be a risk factor for nurses’ health

and organizational outcomes in this

study.

S ture of work life across a

broad range of industries.

Over 20% of workers in

industrialized nations are shift

workers, and about 10% of them

cal rhythm, sleep disorders, health Moreover, nurses who were identi- are diagnosed as having sleep disor-

problems, diminished performance fied as being “non-adaptive” to shift ders. However, the health and safe-

at work, job dissatisfaction, and work were found to work as effec- ty issues associated with shift work

social isolation. tively and safely as their adaptive in general (Basent, 2005; Drake,

In this study, the results of health colleagues in terms of absenteeism Roehers, Richardson, Walsh, &

problems and sleep disorders from work and involvement in pro- Roth, 2004) and with nurses’ health

between female and male nurses, fessional errors and accidents. and patient safety in particular have

between daytime and shift nurses, This research adds two additional

and between sleep-adjusted and

been poorly explored (Muecke,

findings to the field of shift work 2005). Moreover, most of the

non-sleep-adjusted shift nurses studies. The first finding is that

were compared. Also the relation- research in the field of shift work

female shift workers complain signif-

ship between adjustment to shift icantly more about sleep disorders and sleep disorders does not take

work and organizational outcomes than male shift workers. Second, into account the roles of ethnicity,

(errors and incidents and absen- although high rates of nurses whose age, and gender. The present study

teeism from work) was analyzed. sleep was not adapted to shift work attempts to fill this gap by examin-

Gender, age, and weight were more were found, this did not have a ing the impact of shift work on the

significant factors than shift work in more adverse impact on their quality of performance (e.g., work

determining the well-being of nurs- health, absenteeism rates, or per- absenteeism, errors, and adverse

es. formance (reported errors and inci- clinical incidents) among nurses

dents), compared to their “adaptive”

and “daytime” colleagues. and by comparing males and

females in the same profession.

Effects of Shift Work

Shift work can have an impact

HANNA ADMI, PhD, RN, is Director of PAULA HERER, MS, is Statistical Consultant,

on sleep, well-being, performance,

Nursing, Rambam Health Care Campus, Sleep Laboratory, Faculty of Medicine, and organizational outcomes. The

Haifa, Israel. Technion-Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa, existing scientific studies indicate

ORNA TZISCHINSKY, DsC, is a Member of Israel. that shift work affects both sleep

The Sleep Laboratory and Faculty of PERETZ LAVIE, PhD, is Vice President for and waking by disrupting circadian

Medicine, Technion-Israel Institute of Resource Development and Public Affairs, regulation, familial and social life

Technology, Emek Yezreel Academic College, Sleep Laboratory, Faculty of Medicine,

Emek Yezreel, Israel. Technion-Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa,

(Gordon, Cleary, Parker, & Czeisler,

Israel. 1986; Labyak, 2002; Lee, 1992).

RACHEL EPSTEIN, MA, is a Researcher,

Sleep Laboratory, Faculty of Medicine, NOTE: The research reported herein was sup- Sleep obtained during the day or at

Technion-Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa, ported by a grant from the Israel National irregular times is of poorer quality

Israel. Insurance Institute. than that obtained during normal

250 NURSING ECONOMIC$/July-August 2008/Vol. 26/No. 4

nighttime sleep. Chronically re- es, and needlestick injuries were complaints and sleep patterns of

stricted sleep patterns and the sub- associated with the complaint of hospital nurses who are working

sequent sleep debt that accumu- excessive sleepiness. Suzuki and rotating shifts and to examine the

lates over time may be most perva- colleagues (2004) presented no asso- impact of shift work on nurse

sive in such professions as health ciation between shift work and absenteeism and patient safety.

care delivery that function 24 hours occupational accidents, but rather The specific aims of the current

a day, 7 days a week. found an association between men- study were:

Evidence of high risk for signif- tal health and medical errors. 1. To compare subjective medical

icant behavioral and health-related Most of the nursing studies rely complaints and sleep disorders

morbidity is associated with sleep heavily on the general scientific lit- between female nurses and

disorders among shift workers. erature in the field of shift work and male nurses.

Shift workers with sleep disorders sleep disorders. Assuming that shift 2. To compare subjective medical

have higher rates of cardiovascular work is associated with sleep disor- complaints and sleep disorders

diseases and digestive tract prob- ders, the focus of the nursing litera- between daytime nurses and

lems. Research into the impact on ture has been on improving the shift nurses.

professionals has consistently iden- design of the shift system and on 3. To identify the scope of “non-

tified a range of negative outcomes offering strategies for coping with adaptive shift nurses.”

in physical, psychological, and rotating shift work. 4. To compare subjective medical

social domains (Akerstedt, 1988; Various recommendations have complaints and sleep disorders

Costa, Lievore, Casaletti, Gaffuri, & been made in regard to the design of between “adaptive shift nurs-

Folkard, 1989; Kogi, 2005; Paley & the shift work system, such as es” and “non-adaptive shift

Tepas, 1994). The morbidity associ- length of shift (8-12 hours); princi- nurses.”

ated with sleep disorders among ples of rotation (day, night, evening); 5. To compare rates of clinical

shift workers was significantly scheduling (clockwise, number of errors and adverse incidents

greater than that experienced by shifts); and adjustment to individ- between “adaptive shift nurs-

daytime workers with identical ual needs (“morning people” vs. es” and “non-adaptive shift

symptoms, such as sleep-related “night people”) (Thurston, Tanguay, nurses.”

accidents, depression, absenteeism, & Fraser, 2000). Recommendations 6. To compare rates of absen-

and missed family and social activ- for dealing with shift work include teeism between “adaptive shift

ities (Drake et al., 2004). taking a nap prior to the shift; shift nurses” and “non-adaptive

There is growing concern about breaks; bright lighting; healthy shift nurses.”

the ability of individuals to main- snack food; and avoiding coffee,

tain adequate levels of performance alcohol and smoking before daytime Methodology

over long work shifts, particularly sleep (Cooper, 2003). Subjects. Researchers investi-

when those shifts span nighttime gated 738 hospital nurses in a major

hours. Research results are mixed Definition of Terms teaching hospital in northern Israel

on this issue. Gold and colleagues For the purpose of the present during the year 2003. The sample

(1992) reported that the main factor study, we defined “shift work” as a comprised all nurses working only

associated with medical errors was rotating 8-hour shift schedule, daytime shifts or rotating shifts. A

shift work. Rouch, Wild, Ansiau, including morning, evening, and total of 688 nurses (93.2%) com-

and Marquie (2005) demonstrated night shifts. This definition ex- pleted all the questionnaire data,

short-term memory disturbances cludes daytime nurses who perma- including 589 females (85.6%) and

related to circadian rhythm disrup- nently work only morning shifts. A 99 males (14.4%). Of the total sam-

tion caused by shift work. However, “non-adaptive shift worker” is ple, 195 nurses (175 females and 20

4 years after workers stopped work- defined as a shift worker (in our males) worked only days and 493

ing shifts, performance seemed to study, a rotating shift nurse) who nurses (414 females and 79 males)

improve, which suggests a possible complains of “difficulties falling worked flexible rotating shifts

reversibility of effects. asleep after evening, morning or (mornings, evenings, and night

Kawada and Suzuki (2002) night shift” and in addition com- shifts in accordance with the units’

found that rotating shift work affects plains about “multiple awaking and nurses’ needs).

the amount of sleep, but not the rate during day sleep after a night shift.” The study was approved by the

of errors among workers on a three- These definitions were used by the Helsinki Research Ethics Com-

shift schedule. Suzuki, Ohida, authors in previous research stud- mittee of Rambam Medical Center.

Kaneita, Yokoyama, and Uchiyama ies (Lavie et al., 1989). All subjects agreed to participate

(2005) found that professional mis- after they were fully informed

takes, such as drug administration Goal and Objectives about the nature of the study and of

errors, incorrect operation of med- The goal of this study was to their right to leave at any stage.

ical equipment in hospitals by nurs- explore and describe the health Measurements. All nurses com-

NURSING ECONOMIC$/July-August 2008/Vol. 26/No. 4 251

Table 1.

Study Variables and Groups

Medical History and Complaints Reported Sleep Disorders

Male nurses Female nurses Male nurses Female nurses

Day nurses Shift nurses Day nurses Shift nurses

Adaptive nurses Non-adaptive nurses Adaptive nurses Non-adaptive nurses

Nurses’ Absenteeism Errors and Incidents

Adaptive nurses Non-adaptive nurses Adaptive nurses Non-adaptive nurses

Table 2. to compare the different groups

Demographic Data of Male and Female Nurses (N=688) (females vs. males, daytime vs. shift

Males Females nurses, and adaptive vs. non-adap-

Gender N = 99 N = 589 p

tive nurses) in relation to the study

variables (medical history and com-

Mean ± SD Mean ± SD plaints, sleep disorders, incidents,

Age 37.0 ± 9.6 40.4 ± 9.9 0.0009 and absenteeism), as shown in

BMI 26.82 ± 3.45 25.17 ± 4.68 0.0001 Table 1.

Family status 0.02

Results

Single (%) 21.0 11.9

Sample demographics. Signifi-

Married (%) 74.7 75.3 cant differences were found be-

Divorced (%) 4.2 8.8 tween male and female nurses in all

Children 0.03 the demographic variables. In com-

None (%) 21.5 16.0 parison to the male nurses, the

1-2 (%) 49.5 50.0 female nurses were significantly

older, had higher rate of divorce,

3 or more (%) 29.0 34.0

more children, older children, and

Age of youngest 0.0002* longer seniority at work. Body Mass

<4 (%) 48.6 24.6 Index (BMI) was significantly high-

4-8 (%) 21.4 22.8 er in the males, and more male

>8 (%) 30.0 52.6 nurses were single than female

Years at work 0.04

nurses (see Table 2). Assuming that

family status, number, and age of

0-5 (%) 42.9 27.9 children and seniority at work are

6-10 (%) 22.4 22.6 age dependent, the observed demo-

>10 (%) 34.7 49.5 graphic findings indicate signifi-

* Significant after adjustment for age and BMI cant differences in age and BMI. Of

a total 688 nurses, 70% (414) of the

female nurses were working rotat-

pleted self-administered question- tions about daytime fatigue and ing shifts, compared to 80% (79) of

naires that included items on sleepiness, as well as overall well- the male nurses.

demographics; health history and being. Medical history and com-

complaints; and sleep habits and In addition, data about inci- plaints: Gender comparison. The

disorders. dents and errors at work were first aim of the study was to com-

The sleep questionnaires con- obtained for each participant from pare medical complaints and sleep

sisted of a 10-question Sleep an ongoing systematic database disorders between female and male

Disorder Questionnaire, which was gathered by the risk management nurses. The results of the reported

rated on a 7-point Likert scale rang- nurse for the purpose of quality medical history and complaints

ing from “never” to “all the time” (α improvement. Absenteeism was revealed that the female nurses

Cronbach=0.74) (Zomer, Peled, also obtained from a hospital data complained significantly more

Rubin, & Lavie, 1985), and a sleep source based on medical letters. about thyroid problems (p<0.002),

habit questionnaire reflecting Statistical analysis. All analy- backaches (p<0.0008), and leg pain

respondents’ perceptions of sleep ses were performed using SAS pro- (p<0.0005) than the male nurses,

time and sleep quality. In both sleep gram. The data were analyzed using even after adjusting for age and BMI

questionnaires, there were ques- T-test, ANOVA, and Chi Square (χ2) (see Table 3).

252 NURSING ECONOMIC$/July-August 2008/Vol. 26/No. 4

Sleep disorders: Gender com- Table 3.

parison. Results of the sleep disor- Medical History, Complaints, and Sleep Disorders:

der questionnaire showed that the Comparison Between Female and Male Nurses

female nurses complained more Medical History and Males Females

about difficulties falling asleep Complaints (%) (n = 99) (n = 589) p

(p<0.03), mid-sleep awakenings

Heart disease 2.0 1.6 NS

(p<0.0002), headaches after awak-

Hypertension 11.2 8.5 NS

ening from sleep (p<0.0006), and

morning fatigue (p< 0.0001) than Thyroid 1.0 4.7 0.002*

the male nurses, who complained Asthma 3.1 4.7 NS

more about snoring (p<0.0002). Intestinal disease 1.0 3.1 NS

After adjusting for age and BMI (see Diabetes 4.1 1.6 NS

Table 3), the following differences Backache 25.5 40.3 0.0008*

remained significant: snoring, mid- Leg pain 18.6 35.9 0.0005*

sleep awakenings, headache on Sleep Disorders Mean ± SD Mean ± SD

awakening, and fatigue. Difficulty falling asleep 3.05 ± 1.77 3.39 ± 1.58 0.03

Medical history and complaints: Early morning awakening 3.15 ± 1.72 3.24 ± 1.68 NS

Daytime vs. shift work nurses. The

Sleeping pills 1.23 ± 0.78 1.32 ± 0.90 NS

second aim of the study was to com-

Excessive daytime sleepiness 2.25 ± 1.40 1.99 ± 1.28 NS

pare medical complaints and sleep

disorders between daytime versus Morning sleepiness 3.12 ± 1.59 3.34 ± 1.62 NS

shift work nurses. The results Snoring 3.01 ± 1.92 2.27 ± 1.54 0.002*

revealed that the group of daytime Mid-sleep awakenings 2.96 ± 1.42 3.58 ± 1.50 0.002*

nurses were older (p<0.0001), had Headaches on awakening 2.07 ± 1.32 2.44 ± 1.36 0.006*

higher BMI (p<0.02), and had longer Fatigue 2.54 ± 1.46 3.23 ± 1.63 0.001*

seniority (p<0.0001) in comparison Restless sleep 2.36 ± 1.82 2.44 ± 1.62 NS

to the shift nurses. More shift nurs-

* Significant after adjustment for age and BMI

es were single and had more young

children than the daytime nurses.

The daytime nurses complained Table 4.

Medical History, Complaints, and Sleep Disorders:

significantly more about hyperten- Comparison Between Day and Shift Work Nurses

sion (p<0.0007), thyroid (p<0.004),

intestinal disease (p<0.006), dia- Medical History and Day Nurses Shift Nurses

p

betes (p<0.003), leg pain (p<0.003), Complaints (%) (n = 195) (n = 493)

and medicine usage (p<0.0001) (see Heart disease 2.0 1.1 NS

Table 4). After adjustment for age, Hypertension 13.2 5.6 0.0007

BMI, and gender, no significant dif- Thyroid 13.7 6.8 0.004

ferences remained, indicating that Asthma 4.9 3.9 NS

these variables accounted for the

Intestinal disease 6.3 2.1 0.006

differences between daytime and

shift nurses rather than the type of Diabetes 6.3 1.9 0.003

work. Backache 42.9 39.8 NS

Sleep disorders: Daytime vs. Leg pains 42.6 30.7 0.003

Shift work nurses. The shift work Pre-menopause 65.4 84.9 0.0001

nurses complained more than the Medicine use 37.0 15.1 0.0001

daytime nurses about difficulties Sleep Disorders Mean ± SD Mean ± SD

falling asleep (p<0.04), headaches Difficulty falling asleep 3.17 ± 1.58 3.45 ± 1.61 0.04*

on awakening (p<0.05), morning Early morning awakening 3.46 ± 1.74 3.13 ± 1.66 0.02

sleepiness (p<0.0001), and exces- Sleeping pills 1.34 ± 0.94 1.29 ± 0.84 NS

sive daytime sleepiness (p<0.02). Excessive daytime sleepiness 1.88 ± 1.25 2.11 ± 1.32 0.02

The daytime nurses complained

Morning sleepiness 2.85 ± 1.57 3.52 ± 1.59 0.0001

more about snoring (p<0.0001),

early morning awakening (p<0.02), Snoring 2.79 ± 1.63 2.19 ± 1.56 0.0001*

and mid-sleep awakenings (p<0.02). Mid-sleep awakenings 3.71 ± 1.51 3.42 ± 1.49 0.02

After adjustment for age, BMI, and Headaches on awakening 2.20 ± 1.34 2.49 ± 1.35 0.05

gender, the differences in difficul- Fatigue 3.00 ± 1.60 3.22 ± 1.62 NS

ties falling asleep (p<0.003) remain- Restless sleep 2.45 ± 1.58 2.44 ± 1.69 NS

ed higher for the shift work nurses * Significant after adjustment for age, BMI, and gender

NURSING ECONOMIC$/July-August 2008/Vol. 26/No. 4 253

and the differences in snoring Table 5.

remained higher for the daytime Demographic Comparison Between Adaptive and Non-Adaptive Nurses

nurses (p<0.03) (see Table 4). Adaptive Non-Adaptive

The scope of non-adaptive Type p

n = 336 n = 129

nurses. The scope of non-adaptive

shift nurses was the third aim (see Age 36.3 ± 8.7 38.8 ± 9.4 0.01

Table 5). We defined a non-adaptive BMI 25.0 ± 4.2 25.82 ± 5.7 NS

shift nurse as one who complained Family status NS

about difficulty falling asleep after % Single 16.7 16.7

any of the shifts “always” or “many % Married 74.2 71.4

times” and about multiple awaken-

ings from sleep after a night shift % Divorced 6.7 8.7

”always” or “many times” (Lavie et Children NS

al., 1989). Based on the responses to % None 20.2 23.2

the sleep questionnaires, 27.7% % 1-2 54.3 48.8

(125 nurses) were defined as non- % 3 or more 25.5 28.0

adaptive nurses and 72.3% (336

Age of youngest NS

nurses) were defined as adaptive

nurses. No significant differences % <4 38.8 30.5

were found between the females % 4-8 25.0 23.2

and males in either the adaptive or % >8 36.2 46.3

the non-adaptive groups (χ2=2.236, Years at hospital 0.006*

p=0.134).

% 0-5 42.5 26.0

Medical history, health com-

plaints: Adaptive versus non- % 6-10 26.6 31.5

adaptive nurses. Comparison of % >10 30.9 42.5

the medical history, health com- Years in shift NS

plaints, and sleep disorders % 0-5 35.0 26.6

between adaptive versus non-

% 6-10 29.7 28.1

adaptive shift nurses was the

fourth aim of the study. No signif- % >10 35.3 45.3

icant differences were found in Physical activity 0.009*

any reported medical histories or Never 58.5 44.1

health complaints between the 1-3 times a week 28.4 36.2

adaptive nurses and the non-

>3 times a week 13.1 29.7

adaptive nurses (see Table 6).

Sleep disorders: Adaptive vs. * Significant after adjustment for age, BMI, and gender

non-adaptive. In addition to the

difficulties falling asleep and mid-

sleep awakenings after a night reported by 201 night shift nurses. between the adaptive and non-

sleep — the criteria for maladapta- No significant differences were adaptive nurses for all three cate-

tion to the shift system — non- found between the group of 153 gories (χ2=0.49, NS). Adjustments

adaptive shift nurses complained adaptive nurses (45%), and the for age, gender, and BMI did not

more about early morning awaken- group of 48 non-adaptive nurses change the results. It is interesting

ing, use of sleeping pills, (37%) (p=0.14). Adjustments for to note that over 50% of the non-

headaches in the morning, morn- age, gender, and BMI did not adaptive nurses did not miss work

ing fatigue, and restless sleep. change the results. even once a year because of a

Adjustments for age and BMI did Absentees at work. The last health problem and only 8%

not change the results (see Table 6). aim of this study was to compare missed work more than four times

Errors and incidents at work. rates of absenteeism between “ad- a year.

The fifth aim of this study was to aptive” and “non-adaptive” shift

compare clinical errors and ad- nurses. The number of absentees Discussion

verse incidence report between was divided into three categories It is well established that 20%

adaptive and non-adaptive shift during the 1-year research period: of the workers in our society are

nurses. During the 1-year research none, one to three times a year, and shift workers (night shifts and

period, 205 clinical errors and more than four times a year. As rotating shifts) and that approxi-

adverse incidences (e.g., medica- demonstrated in Table 7, no signif- mately half of them complain of

tion errors, patient falls) were icant differences were found difficulties with their sleep (Drake

254 NURSING ECONOMIC$/July-August 2008/Vol. 26/No. 4

Table 6. nizational outcomes (errors and

Medical History, Health Complaints, and Sleep Disorders: incidents and absenteeism from

Comparison Between Adaptive and Non-Adaptive Nurses work).

Shift work and gender. The

Medical History and Adaptive Non-Adaptive

Complaints (%) n = 336 n = 129

p main demographic gender-related

differences in this study indicate

Heart disease 0.9 1.6 NS

that the female nurses are signifi-

Hypertension 4.4 8.5 NS cantly older and have lower BMI

Thyroid 7.7 4.7 NS than the male nurses. In addition,

Asthma 3.6 4.7 NS the female nurses complained

Intestinal disease 1.8 3.1 NS more about health problems (thy-

Diabetes 2.1 1.6 NS roid problems, backache, and leg

Backache 39.6 40.3 NS pain) and sleep disorders (mid-

Leg pains 28.7 35.9 NS sleep awakenings, headaches on

Pre-menopause 86.5 80.9 NS awakening, and morning fatigue)

Sleep Disorders Mean ± SD Mean ± SD than the male nurses. One question

that should be raised is whether

Difficulty falling asleep** 3.11 ± 1.52 4.33 ± 1.52 0.0001*

these results reflect a general ten-

Early morning awakening 2.79 ± 1.59 4.0 ± 1.52 0.0001*

dency of females to complain more

Sleeping pills 1.19 ± 0.59 1.5 ± 1.2 0.003* than males about their health and

Excessive daytime sleepiness 2.09 ± 1.3 2.16 ± 1.39 NS sleep. Another question that needs

Morning sleepiness 3.45 ± 1.56 3.72 ± 1.65 NS examination is whether the

Snoring 2.15 ± 1.56 2.30 ± 1.57 NS females’ subjective complaints

Mid-sleep awakenings** 3.1 ± 1.4 4.2 ± 1.4 0.0001* about their health problems and

Headaches on awakening 2.34 ± 1.28 2.9 ± 1.45 0.0001* sleep disorders can be supported

Morning fatigue 3.1 ± 1.6 3.6 ± 1.6 0.009* by objective evidence. To answer

Restless sleep 2.3 ± 1.6 2.8 ± 1.8 0.0009* these questions, we designed a sec-

ond phase of this study that was

* Significant after adjustment for age, gender, and BMI aimed to test objective indicators of

** Variables that define non-adaptive shift nurse health condition and sleep patterns

among the sample.

Shift work, health problems,

Table 7. and sleep disorders. Surprisingly,

Absentees at Work During 1 Year in contrast with the wealth of liter-

Adaptive Non-adaptive ature on the adverse effects of shift

Number of Absentees work on workers’ health, our

n = 336 n = 129 p

results indicate that daytime nurs-

None (%) 45.5 52.1 NS

es complained significantly more

1-3 times (%) 43.7 39.6 NS

than shift nurses about health prob-

More than 4 times (%) 10.8 8.3 NS lems and sleep disturbances. The

* During 1 year main predictors of health symp-

toms and sleep disturbances were

age and BMI.

The phenomenon of non-ad-

et al., 2004). There is also evidence male workers in the same profes- aptive shift nurses. In our study,

in the scientific literature of the sion, namely nursing. We com- 27.7% of the nurses were non-ad-

adverse physiological and psycho- pared the results of health prob- aptive to shift work, compared to

logical effects of shift work, includ- lems and sleep disorders between the 5% to 10% reported for sleep

ing disruption to biological female and male nurses, between disorders in the scientific sleep liter-

rhythm, sleep disorders, health daytime and shift nurses, and ature (Drake et al., 2004). The differ-

problems, diminished performance between sleep-adjusted and non- ences might stem from meth-

at work, job dissatisfaction, and sleep-adjusted shift nurses. Given odological, gender, or cultural dif-

social isolation (Morshead, 2002; the lack of research on the impact ferences. Methodologic problems

Muecke, 2005; Westfall-Lake, of shift work and sleep deprivation can stem from different definitions

1997). on nurses’ performance and patient of the terms “non-adaptive” and

Our study was aimed at exam- care (Brown, 2004), we also “sleep disorder” or from non-stan-

ining the phenomenon of shift explored the relationship between dardized criteria for shift workers

work among a group of female and adjustment to shift work and orga- (e.g., type, length, duration of shift).

NURSING ECONOMIC$/July-August 2008/Vol. 26/No. 4 255

The findings may indicate true teeism rates from work than the field of shift work studies. The first

differences between male and “adaptive” nurses. We can only finding is that female shift workers

female shift workers or may sug- conclude that there is no relation- complain significantly more about

gest sociocultural differences. ship between reported sleep disor- sleep disorders than male shift

Lavie and colleagues (1989) re- ders and performance, as demon- workers. The second finding is that

ported about 15% non-adaptive strated by this study’s findings. although we found high rates of

shift workers among a group of nurses whose sleep was not adapt-

male workers, which is less than Conclusions ed to shift work, we did not find a

that found among male and female It appears that gender, age, and more adverse impact on their

non-adaptive nurses. Even though weight are more significant factors health, absenteeism rates, or per-

we used only two questions to than shift work in determining the formance (reported errors and inci-

define adaptiveness, there were well-being of nurses. Moreover, dents), compared to their “adap-

many more differences between nurses who were identified as tive” and “daytime” colleagues. In

the two groups. Those differences being non-adaptive to shift work other words, shift work by itself

may present organizational culture based on their complaints about was not a risk factor for nurses’

effects. Further research is needed sleep were found to work as effec- health and organizational out-

to address these differences. tively and safely as their adaptive comes in this study.

Shift work and organizational colleagues in terms of absenteeism

outcomes. In the present study, we from work and involvement in pro- Policy Implications

investigated the impact of sleep fessional errors and accidents. Nurses are expected to deliver

disturbances on shift nurses and on It is important to emphasize high-quality care and to assure

two organizational outcomes: that the decision to define a nurse patient safety 24 hours a day in

errors and incidents and absen- as “adaptive” or “non-adaptive” health care facilities. Taking into

teeism from work. Based on our lit- was solely based on two subjective account that nursing is a predomi-

erature review (Morshead, 2002; complaints about sleep disorders. nantly female profession with an

Muecke, 2005; Westfall-Lake, The fact that we found higher rates increasingly aging workforce and a

1997), we expected that “non-ad- of nurses who were not adjusted to prolonged shortage of human

aptive shift nurses” would report shift work than reported in the lit- resources, it is the responsibility of

on more involvement in errors and erature thus far, might be attributed health care leaders to identify

adverse incidents as compared to to differences in gender, age, BMI, health risks and their effects on

“adaptive shift nurses.” We also and the definition of “adapting” work patterns (absenteeism) among

assumed that non-adaptive nurses, versus “non-adapting” nurses nursing personnel as well as risks

who by definition have more sleep- employed in our study. It is well- to patient safety.

related complaints, would have established that the ability to cope Policymakers should consider

higher absenteeism rates due to ill- with rotating night shifts is dimin- the impact of the aging nursing

ness compared to their adaptive ished with age and that BMI is workforce. Daytime nursing per-

colleagues. Neither of our hypothe- rising with age (Learhart, 2000; sonnel tend to be in managerial

ses was supported by the results of Reid & Dawson, 2001; Reilly, positions, as they are older and

this study. Waterhouse, & Atkinson, 1997). have more seniority and experi-

It is known that there is a ten- As for gender, most research on ence. However, with the increasing

dency toward under-reporting on sleep disturbances associated with age of nurses, we already find

professional errors and incidents; shift work has been conducted growing numbers of older nurses

however, there is no reason to among male workers, and there is who are required to work rotating

believe that the non-adaptive not enough evidence for compari- shifts, including night shifts. This

nurses would avoid reporting son with females. It has yet to be should be a point of concern for

more or less than the adaptive investigated whether the differ- both the nurses and the patients.

nurses. We found lower absen- ences in adjustment to shift work The work scheduling policy

teeism rates among the shift work between male and female workers for the nurses in the hospital where

nurses (both adaptive and non- are supported objectively or this study was conducted is to

adaptive) than among the daytime whether they are attributable to the schedule 8-hour flexible rotating

nurses, which may be explained tendency of female workers to shifts according to employee pref-

by differences in age. express more complaints. In this erences and organizational needs.

There is a need to further context, it would be interesting to There is some research evidence in

explore the reasons that the “non- investigate the impact of organiza- the literature indicating that in gen-

adaptive” nurses in the present tional culture and social culture on eral, nurses who work their pre-

study were not more involved in workers’ norms of complaining. ferred shifts and their preferred

professional errors and incidents In conclusion, this research work weeks report more positive

and did not have higher absen- adds two additional findings to the work outcomes and less interfer-

256 NURSING ECONOMIC$/July-August 2008/Vol. 26/No. 4

ence with their non-work activities Gordon, N.P., Cleary, P.D., Parker, C.E., & Reid, K., & Dawson, D. (2001). Comparing

(Havlovic, Lau, & Pinfield, 2002). Czeisler, C.A. (1986). The prevalence performance on a simulated 12 hour

and health impact of shift work. shift rotation in young and older sub-

While there is not much that American Journal of Public Health, jects. Occupational and Environment-

can be done about age and gender, 76(10), 1225-1228. al Medicine, 58(1), 58-62.

other than to take these factors into Havlovic, S.J., Lau, D.C., & Pinfield, L.T. Reilly, T., Waterhouse, J., & Atkinson, G.

account in shift planning, there is a (2002). Repercussions of work sched- (1997). Aging, rhythms of physical per-

ule congruence among full-time, part- formance, and adjustment to changes

need to address the increasing obe- time and contingent nurses. Health in the sleep activity cycle.

sity among health care profession- Care Management Review, 27(4), 30- Occupational and Environmental

als, such as by encouraging a bal- 41. Medicine, 54(11), 812-816.

anced diet and exercise regime. Kogi, K. (2005). International research needs Rouch, I., Wild, P., Ansiau, D., & Marquie,

Future studies should contin- for improving sleep and health of J.C. (2005). Shiftwork experience, age,

workers. Industrial Health, 43(1), 71- and cognitive performance. Ergonom-

ue to explore the effects of shift 79. ics, 48(10), 1282-1293.

work through objective indicators Kawada, T., & Suzuki, S. (2002). Monitoring Suzuki, K., Ohida, T., Kaneita, Y.,

for measuring sleep disorders, sleep hours using a sleep diary and Yokoyama, E., Miyake, T., Harano, S.,

adaptation to shift work, and bio- errors in rotating shiftworkers. et al. (2004). Mental health status, shift

Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, work, and occupational accidents

logical markers of health problems. 56, 213-214. among hospital nurses in Japan.

It is of importance to further Lavie, P., Chillag, N., Epstein, R., Journal of Occupational Health, 46,

explore gender differences among Tzischinsky, O., Givon, R., Fuchs, S., et 448-454.

shift workers, as well as the effects al. (1989). Sleep disturbances in shift- Suzuki, K., Ohida, T., Kaneita, Y.,

of different organizational cultures workers: A marker for maladaptation Yokoyama, E., & Uchiyama, M. (2005).

syndrome. Work and Stress, 3(1), 33- Daytime sleepiness, sleep habits and

and different occupations (indus- 40. occupational accidents among hospi-

trial workers, helping professions) Labyak, S. (2002). Sleep and circadian tals nurses. Journal of Advanced

on adjustment to shift work and its schedule disorders. Nursing Clinics of Nursing, 52(4), 445-453.

impact on employees’ health and North America, 37, 599-610. Thurston, N.E., Tanguay, S.M., & Fraser, K.L.

Lee, K.A. (1992). Self reported sleep distur- (2000). Sleep and shiftwork. The

organizational outcomes.$ bances in employed women. Sleep, Canadian Nurse, 96(9), 35-40.

15(6), 493-498. Westfall-Lake, P. (1997). Shift scheduling’s

REFERENCES Learhart, S. (2000). Health effects of internal impact on morale, and performance.

Akerstedt, T. (1988). Sleepiness as a conse- rotation of shifts. Nursing Standard, Occupational Health & Safety, 66(10),

quence of shift work. Sleep, 11(1), 17- 14(47), 34-36. 146-149.

34. Morshead, D.M. (2002). Stress and shift Zomer, J., Peled, R., Rubin, A., & Lavie, P.

Basent, B. (2005). Shift-work sleep disorder work. Occupational Health & Safety, (1985). Mini-sleep questionnaire

– The glass is more than half empty. 71(4), 36-39. (MSQ) for screening large populations

New England Journal of Medicine, Muecke, S. (2005). Effects of rotating night for EDS complaints. In W.P. Koella & P.

353(5), 519-521. shifts: Literature review. Journal of Levin (Eds.), Sleep (pp. 467-470).

Brown, P.S. (2004). Relationships among life Advanced Nursing, 50(4), 433-439. Basel, Switzerland: Krager.

event stress, role and job strain, and Paley, M.J., & Tepas, D.I. (1994). Fatigue and

sleep in middle-aged female shift the shiftworker: Firefighters working

workers. Unpublished doctoral disser- on a rotating shift schedule. Human

tation: Wayne State University, Detroit, Factors, 36(2), 269-284.

MI.

Costa, G., Lievore, F., Casaletti, G., Gaffuri,

E., & Folkard, S. (1989). Circadian

characteristics influencing inter-indi-

vidual differences in tolerance and

adjustment to shift work. Ergonomics,

32(4), 373-385.

Cooper, E.E. (2003). Pieces of the shortage

puzzle: Aging and shift work. Nursing

Economic$, 21(2), 75-79.

Drake, C.L., Roehers, T., Richardson, G.,

Walsh, J.K., & Roth, T. (2004). Shift

work sleep disorders: Prevalence and

consequences beyond that of sympto-

matic day workers. Sleep, 27(8), 1453-

1462.

Gold, D.R., Rogacz, S.R., Bock, N., Tosteson,

T.D., Baum, T.M., Speizer, F.E., et al.

(1992). Rotating shift work, sleep, and

accidents related to sleepiness in hos-

pital nurses. American Journal of

Public Health, 82, 1011-1014.

NURSING ECONOMIC$/July-August 2008/Vol. 26/No. 4 257

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

You might also like

- Benefits of Giving Up PornDocument83 pagesBenefits of Giving Up Porncabanoso50% (2)

- Astral Q-ADocument14 pagesAstral Q-ARyon Shorter100% (1)

- Dream Arc Part 1Document6 pagesDream Arc Part 1ZenZol75% (4)

- Natural Muscle - June 2008Document35 pagesNatural Muscle - June 2008alfortlan100% (1)

- Fatigue, Performance and The Work Environment A Survey of Registered NursesDocument13 pagesFatigue, Performance and The Work Environment A Survey of Registered NursesnindyaNo ratings yet

- Burnout Research 2019 AbellabnosaDocument16 pagesBurnout Research 2019 AbellabnosaRex Decolongon Jr.100% (1)

- Workplace Bullying, Job Stress, Intent To Jurnal 1Document23 pagesWorkplace Bullying, Job Stress, Intent To Jurnal 1haslinda100% (1)

- Cataract (Care Study)Document30 pagesCataract (Care Study)John Ryan100% (3)

- 7steps 523 PDFDocument100 pages7steps 523 PDFsudyNo ratings yet

- Measurement of Job Stress & Satisfaction Among Sudanese Doctors in Khartoum State - Sudan 2019Document8 pagesMeasurement of Job Stress & Satisfaction Among Sudanese Doctors in Khartoum State - Sudan 2019International Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- 6 Surprising Habits That Hurt His Sex LifeDocument7 pages6 Surprising Habits That Hurt His Sex LifeBhagoo Hathey100% (1)

- 200 108 PBDocument76 pages200 108 PBAmi NuariNo ratings yet

- 2018-The Relationship Between PerceivedDocument8 pages2018-The Relationship Between PerceivedFernandoCedroNo ratings yet

- Evidence Based Nursing Practice For Oncology Nursing2Document4 pagesEvidence Based Nursing Practice For Oncology Nursing2Alaina MalsiNo ratings yet

- Journal of Advanced Nursing - 2017 - Olsen - Work Climate and The Mediating Role of WorkplaceDocument11 pagesJournal of Advanced Nursing - 2017 - Olsen - Work Climate and The Mediating Role of WorkplaceAqib SyedNo ratings yet

- Heavy Physician Workloads: Impact On Physician Attitudes and OutcomesDocument9 pagesHeavy Physician Workloads: Impact On Physician Attitudes and OutcomesNguyễn Xuân LộcNo ratings yet

- Schaaf DumontArbesomMay-BensonASIevidence2018Document11 pagesSchaaf DumontArbesomMay-BensonASIevidence2018Claudia ArandaNo ratings yet

- Park, 2019Document10 pagesPark, 2019Fatimah EkaNo ratings yet

- Psychometric Propertiesofthe Extended Nursing Stress ScaleDocument15 pagesPsychometric Propertiesofthe Extended Nursing Stress Scaleabeer alzhoorNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Shift Work On The Psychological andDocument9 pagesThe Impact of Shift Work On The Psychological andratna220693No ratings yet

- Balance, Health, and Workplace Safety Experiences of New Nurses in The Context of Total Worker HealthDocument9 pagesBalance, Health, and Workplace Safety Experiences of New Nurses in The Context of Total Worker HealthSAIYIDAH AFIQAH BINTI MUHAMAD YUSOFNo ratings yet

- Work-Related Stress Among Nurses Working in NorthwestDocument5 pagesWork-Related Stress Among Nurses Working in NorthwestAdrian KmeťNo ratings yet

- Kerangka JJ HurrellDocument14 pagesKerangka JJ HurrellNur qamaliahNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Job Demands On PDocument10 pagesThe Effects of Job Demands On PMadalina SoldanNo ratings yet

- Occupational Stress of Nurses in South Africa: Research ArticleDocument12 pagesOccupational Stress of Nurses in South Africa: Research Articleanna regarNo ratings yet

- The Prevalence of Work-Related Neck, Shoulder, and Upper Back Musculoskeletal Disorders Among Midwives, Nurses, and PhysiciansDocument18 pagesThe Prevalence of Work-Related Neck, Shoulder, and Upper Back Musculoskeletal Disorders Among Midwives, Nurses, and Physiciansmutiara yerivandaNo ratings yet

- The Prevalence of Work-Related Neck, Shoulder, and Upper Back Musculoskeletal Disorders Among Midwives, Nurses, and PhysiciansDocument18 pagesThe Prevalence of Work-Related Neck, Shoulder, and Upper Back Musculoskeletal Disorders Among Midwives, Nurses, and Physiciansmutiara yerivandaNo ratings yet

- Articolo Zurlo Vallone Smith 2020Document13 pagesArticolo Zurlo Vallone Smith 2020Kairaba KijeraNo ratings yet

- Hegney 2006Document11 pagesHegney 2006Angel Mary BarronNo ratings yet

- Applied Nursing Research: Jiajia Guo, MD, Juan Chen, MD, Jie Fu, MD, Xinling Ge, MD, Min Chen, MD, Yanhui Liu, PHDDocument5 pagesApplied Nursing Research: Jiajia Guo, MD, Juan Chen, MD, Jie Fu, MD, Xinling Ge, MD, Min Chen, MD, Yanhui Liu, PHDselfiNo ratings yet

- Health Trade-Offs in TeleworkingDocument5 pagesHealth Trade-Offs in TeleworkingCaroHerreraNo ratings yet

- Out (1) NurcesDocument19 pagesOut (1) Nurcesjosselyn ayalaNo ratings yet

- Turnover Intention Among Italian Nurses: The Moderating Roles of Supervisor Support and Organizational SupportDocument8 pagesTurnover Intention Among Italian Nurses: The Moderating Roles of Supervisor Support and Organizational SupportDr-Aamar Ilyas SahiNo ratings yet

- Artikel Bahasa InggrisDocument7 pagesArtikel Bahasa InggrisFaruq AlfarobiNo ratings yet

- Chapter IDocument47 pagesChapter IJane ParkNo ratings yet

- Presenteeism Revisited: A Comprehensive ReviewDocument15 pagesPresenteeism Revisited: A Comprehensive ReviewTeguh GarinNo ratings yet

- Nursing Students' Sleep Patterns and Perceptions of Safe Practice During Their Entree To Shift WorkDocument7 pagesNursing Students' Sleep Patterns and Perceptions of Safe Practice During Their Entree To Shift WorkshaviraNo ratings yet

- Making Women Visible in OHS ENGLISH DefDocument20 pagesMaking Women Visible in OHS ENGLISH DefDinaSeptiNo ratings yet

- Exploring Productivity of Nurses in Pakistan's Health SectorDocument13 pagesExploring Productivity of Nurses in Pakistan's Health SectorApplied Psychology Review (APR)No ratings yet

- Chang2006 PDFDocument9 pagesChang2006 PDFNotafake NameatallNo ratings yet

- Sarita StressDocument6 pagesSarita StressAl FatihNo ratings yet

- Nurse Health, Work Environment, Presenteeism and Patient SafetyDocument17 pagesNurse Health, Work Environment, Presenteeism and Patient Safetymadalena limaNo ratings yet

- Jobstressdimension MSDs WorkDocument8 pagesJobstressdimension MSDs WorkcacaNo ratings yet

- For Needle Stick InjuriesDocument17 pagesFor Needle Stick InjuriesMrLarry DolorNo ratings yet

- Assignment Evidence-Based Project, Part 1 - Identifying Research MethodologiesDocument6 pagesAssignment Evidence-Based Project, Part 1 - Identifying Research MethodologiesJoseph AkitongaNo ratings yet

- Work-Related Fatigue Among Medical Personnel in TaiwanDocument8 pagesWork-Related Fatigue Among Medical Personnel in TaiwanfaridaNo ratings yet

- Investigating The Relationship Between Musculoskeletal Disorders and Quality of Work Life in Nursing StaffDocument4 pagesInvestigating The Relationship Between Musculoskeletal Disorders and Quality of Work Life in Nursing Staffmaria.centeruniNo ratings yet

- Burnout Male InfertilityDocument7 pagesBurnout Male InfertilityAbraham ChiuNo ratings yet

- The Mental Health Impacts of HealthDocument7 pagesThe Mental Health Impacts of HealthReno ShiapahyyNo ratings yet

- ASurveyonthe Associated Factorsof Stressamong Operating Room PersonnelDocument6 pagesASurveyonthe Associated Factorsof Stressamong Operating Room PersonnelzharifderisNo ratings yet

- Journal of Advanced Nursing - 2007 - Wu - Relationship Between Burnout and Occupational Stress Among Nurses in ChinaDocument7 pagesJournal of Advanced Nursing - 2007 - Wu - Relationship Between Burnout and Occupational Stress Among Nurses in ChinaEsraa QabeelNo ratings yet

- Effort-Reward Imbalance and Burnout Among ICU Nursing Staff A Cross-Sectional StudyDocument7 pagesEffort-Reward Imbalance and Burnout Among ICU Nursing Staff A Cross-Sectional StudySebastian Adolfo Palma MoragaNo ratings yet

- Nurse Burnout and Its Association With Occupational Stress in A Cross-Sectional Study in ShanghaiDocument10 pagesNurse Burnout and Its Association With Occupational Stress in A Cross-Sectional Study in ShanghainadiaNo ratings yet

- Research PaperDocument16 pagesResearch PaperQurat-ul-ain abroNo ratings yet

- Nurses' Work-Related Stress in China: A Comparison Between Psychiatric and General HospitalsDocument6 pagesNurses' Work-Related Stress in China: A Comparison Between Psychiatric and General HospitalspuneymscNo ratings yet

- 2015 - Effects of Deep Pressure Stimulation On Physiological Arousal VAYU VEST With STRESSOR MORON TESTDocument5 pages2015 - Effects of Deep Pressure Stimulation On Physiological Arousal VAYU VEST With STRESSOR MORON TESTM Izzur MaulaNo ratings yet

- IJEAS0208032Document6 pagesIJEAS0208032erpublicationNo ratings yet

- 2023 Exploring The Sources Among Operating Theatre Nurses in GhanaianDocument9 pages2023 Exploring The Sources Among Operating Theatre Nurses in GhanaianNursyazni SulaimanNo ratings yet

- Adriaen S Sens 2013Document13 pagesAdriaen S Sens 2013Krem LinNo ratings yet

- EJOM Volume 39 Issue 2 Pages 119-133Document15 pagesEJOM Volume 39 Issue 2 Pages 119-133Mohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- 2006 - Kovner - Factors Associated With Work Satisfaction of Registered NursesDocument9 pages2006 - Kovner - Factors Associated With Work Satisfaction of Registered NursesGeorgianaDîdălNo ratings yet

- 22 The Effects of Noise Levels On Nurses inDocument7 pages22 The Effects of Noise Levels On Nurses inLeonardoMartínezNo ratings yet

- The Mediating Role of Psychophysic Strain in The Relationship Between Workaholism, Job Performance, and Sickness AbsenceDocument7 pagesThe Mediating Role of Psychophysic Strain in The Relationship Between Workaholism, Job Performance, and Sickness AbsenceAleCsss123No ratings yet

- Situational Factors Associated With Burnout Among Emergency Department NursesDocument4 pagesSituational Factors Associated With Burnout Among Emergency Department NursesAl FatihNo ratings yet

- Adriaenssens - Determinants and Prevalence of Burnout in Emergency NursesDocument13 pagesAdriaenssens - Determinants and Prevalence of Burnout in Emergency NursesaditeocanNo ratings yet

- Adriaen S Sens 2015Document13 pagesAdriaen S Sens 2015PeepsNo ratings yet

- SOCIAL WORK ISSUES: STRESS, THE TEA PARTY ROE VERSUS WADE AND EMPOWERMENTFrom EverandSOCIAL WORK ISSUES: STRESS, THE TEA PARTY ROE VERSUS WADE AND EMPOWERMENTNo ratings yet

- Ics-Pearson AssessmentDocument16 pagesIcs-Pearson AssessmentShane JacobNo ratings yet

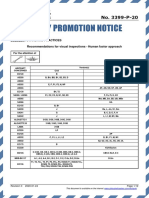

- Safety Promotion Notice: Subject: Standard Practices Recommendations For Visual Inspections - Human Factor ApproachDocument12 pagesSafety Promotion Notice: Subject: Standard Practices Recommendations For Visual Inspections - Human Factor ApproachAlejandro RagoNo ratings yet

- Why Is Getting Old Getting Harder To Sleep?Document1 pageWhy Is Getting Old Getting Harder To Sleep?Wilda FuadiyahNo ratings yet

- Assignment in Advance ReadingDocument3 pagesAssignment in Advance ReadingJessa CaberteNo ratings yet

- ReadingDocument43 pagesReadingjd.malagon19No ratings yet

- Sat 1-11Document2 pagesSat 1-11TolkynNo ratings yet

- Effect of Modern Food and Lifestyle On Human Biological Clocks and Health: A ReviewDocument13 pagesEffect of Modern Food and Lifestyle On Human Biological Clocks and Health: A ReviewPriyanka SharmaNo ratings yet

- Analytical Exposition TextDocument9 pagesAnalytical Exposition TextIza LaelinaNo ratings yet

- Juggling Academics and Work: The Experiences of Marist Working StudentsDocument14 pagesJuggling Academics and Work: The Experiences of Marist Working StudentsPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- MELLA Instruction Manual v.1.6 FINAL EUDocument96 pagesMELLA Instruction Manual v.1.6 FINAL EUrtsNo ratings yet

- Cakna BiDocument7 pagesCakna BiAkMa KemaNo ratings yet

- Wi-Sleep. Contactless Sleep Monitoring Via WiFi Signals. Xuefeng Liu. 2014Document10 pagesWi-Sleep. Contactless Sleep Monitoring Via WiFi Signals. Xuefeng Liu. 2014Pavel SchukinNo ratings yet

- Review Related LiteratureDocument3 pagesReview Related LiteraturerdsamsonNo ratings yet

- 64b7b35bc9375b7b74aa4812 - Monk Mode Guide - Quantified-Self System™Document22 pages64b7b35bc9375b7b74aa4812 - Monk Mode Guide - Quantified-Self System™StefanNo ratings yet

- Verran and Snyder-Halpern Sleep Scale (VSH)Document2 pagesVerran and Snyder-Halpern Sleep Scale (VSH)Bastan SNo ratings yet

- 1471 2431 12 13Document10 pages1471 2431 12 13Toriq FatwaNo ratings yet

- Sleeping My Day Away Chords (Ver 2) by D.A.D.tabs at Ultimate Guitar ArchiveDocument2 pagesSleeping My Day Away Chords (Ver 2) by D.A.D.tabs at Ultimate Guitar ArchiveKarl GirdamanNo ratings yet

- Mock Occupational English Test Hyperthyroidism PDFDocument5 pagesMock Occupational English Test Hyperthyroidism PDFAbdullahNo ratings yet

- 14 Interesting Facts About DreamsDocument3 pages14 Interesting Facts About Dreamsratchagar aNo ratings yet

- Bed Configuration of HotelDocument12 pagesBed Configuration of HotelMarnieNo ratings yet

- AP Psych Mod 3 JournalDocument12 pagesAP Psych Mod 3 Journal5662649No ratings yet

- Anti Aging Health Benefits of YogaDocument5 pagesAnti Aging Health Benefits of Yogasourav.surNo ratings yet

- VSTEP Reading Test - 4.2024Document12 pagesVSTEP Reading Test - 4.2024tieen379No ratings yet