Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Strategic Sourcing A Progressive Approach To The Make-Or-Buy Decision

Uploaded by

rafOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Strategic Sourcing A Progressive Approach To The Make-Or-Buy Decision

Uploaded by

rafCopyright:

Available Formats

Strategic Sourcing: A Progressive Approach to the Make-or-Buy Decision

Author(s): James A. Welch and P. Ranganath Nayak

Source: The Executive , Feb., 1992, Vol. 6, No. 1 (Feb., 1992), pp. 23-31

Published by: Academy of Management

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4165048

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Academy of Management is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

The Executive

This content downloaded from

14.139.218.161 on Mon, 19 Oct 2020 05:16:24 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

0 Academy of Management Executive, 1992 Vol. 6 No. I

...........................................................................................................................................................................

Strategic sourcing: a

progressive approach to the

make-or-buy decision

James A. Welch, Arthur D. Little, Inc.

P. Ranganath Nayak, Arthur D. Little, Inc.

Executive Overview Historically, many firms have made sourcing decisions-commonly known as

make-or-buy decisions-based disproportionately on unit cost, with insufficient

regard for strategic or technological issues. This cost-focused approach has led

to competitive tragedy for many firms, indeed, entire industries. Managers need

better tools for evaluating sourcing decisions-tools that can accommodate the

long-term, strategic issues. This article presents such a tool, the strategic

sourcing model, which augments the traditional cost analysis by considering

strategic and technological factors. Using this framework, in conjunction with a

cost analysis, can help companies make the sourcing decisions that will move

them into the leagues of world-class manufacturing and position them for

sustained competitive success in the future.

Article The decision to make or buy is arguably the most fundamental component of

manufacturing strategy. Should a firm be highly vertically integrated, such as

Henry Ford's River Rouge plant, with raw iron ore and coal flowing in one end

and finished model A's rolling out the other?' Or should it assign the manufacture

of components to capable suppliers and then perform an assembly role-in what

is termed by some a "hollow" or "screwdriver" plant-combining inputs from

many suppliers to produce a finished product?

While human Henry Ford's model of vertical integration slipped from vogue in the 1950s and

resources are key to 1960s, when industry increasingly began to use outsourcing. Firms found that

any firm, the outsourcing had certain advantages, potentially allowing them to:

emphasis placed on

the labor category of * Convert fixed costs to variable costs, thereby providing flexibility in an economic

the cost sheet is often downturn

disproportionate. * Balance work force requirements

* Reduce capital investment requirements

* Reduce costs via suppliers' economies of scale and lower wage structures

* Accelerate new product development2

* Gain access to invention and innovation from suppliers

* Focus resources on high value-added activities

The Importance of Make-or-Buy Decisions

Averaged across all U.S. manufacturing establishments, the costs of purchased

inputs amount to about fifty-three percent of sales revenues, while labor costs

amount to only ten percent.3 Despite this, many manufacturers are obsessed with

labor issues, allocate overhead based on labor content, and justify capital

improvements based primarily on labor savings alone. While human resources

are key to any firm, the emphasis placed on the labor category of the cost sheet is

often disproportionate.

23

This content downloaded from

14.139.218.161 on Mon, 19 Oct 2020 05:16:24 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Academy of Management Executive

While unionized manufacturers have decidedly less flexibility for outsourcing,

these companies may often overlook make-or-buy opportunities. Further,

unionized manufacturing workers are a relative minority, comprising only about

one-quarter of all plant laborers.4

Since purchased inputs are such a large portion of total product cost, the attention

that make-or-buy decisions deserve cannot be overstated. In fact, the gains to be

made by addressing purchasing issues are far greater than those that accrue by

attacking labor costs directly.

Beyond static cost issues, however, there are longer-term, strategic considerations

intertwined with the make-or-buy decision that are of even greater importance.

These strategic issues are the focus of this article. Here, we explain why and how

the following strategic variables should be considered in the course of a

make-or-buy decision:

* Process technology and its relationship to competitive advantage

* Maturity of process technology

* Competitors' process technology positions

Contemporary Challenges

In previous decades, outsourcing became big business and purchasing

departments expanded to tremendous proportions to manage the many vendors

supplying components, subassemblies, and services. As recently as 1989, General

Motors reported more than 8,000 suppliers for direct material alone.5 In the past,

manufacturers often elected to buy inputs, rather than make them, typically based

on myopic cost analyses. Rather than automating difficult or complex

labor-intensive processes, manufacturers bought from low-labor-wage sources

around the globe, at rates that were less than twenty-five percent of the U.S.

average. Today, the labor-cost advantage held by these suppliers is diminishing

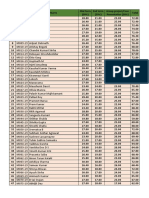

(Exhibit 1).

.............................................................................................................................................................................

Just as Japan's labor-cost advantage has disappeared for U.S. manufacturers, the

labor-cost advantage of other countries is shrinking as their industrial bases and

economies develop. Furthermore, many suppliers that are located abroad, chosen

in prior decades because of their low labor costs, have grown to become feared

competitors.

The list of industries affected by this phenomenon is well known. Some of the most

notable include: consumer electronics, machine tools, semiconductors, and office

equipment.

Pressured by short decision cycles, many manufacturers lost sight of the long-term

risk associated with outsourcing key inputs. They did not anticipate that

low-labor-cost suppliers could learn the critical skills necessary to become

competitive threats. These suppliers subsequently leveraged their relationships

with their customers to become highly competent at manufacturing, assembly,

engineering, and design. Today, many have also mastered Reseatrch and

Development (R&D). Ironically, the processes that were once thought too difficult

or costly to automate have now been automated by the very suppliers who were

chosen in favor of automation.7 These aggressive suppliers have successfully

integrated forward, becoming world-class competitors that continue to gain market

share from the companies they once served.

24

This content downloaded from

14.139.218.161 on Mon, 19 Oct 2020 05:16:24 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Welch and Nayak

Relative manufacturing wage rates

Japan l

Taiwan

Singapore

South Korea

Hong Kong

Mexico

Brazil

India 1974 1988

0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140

Percent of U.S. dollars per hour

* Wages include supplemental benefits.

* Sources:6

-The World Competitiveness Report 1990, table 2.04

-Yearbook of Labor Statistics 1978, table 1 7A

-International Financial Statistics Yearbook 1982, passim

-The Wall Street Journal, June 28, 1974, p. 34

Exhibit 1. Wage Rate Gap Has Narrowed for Manufacturing Abroad

Consumer radios provide an example of an unfortunate sourcing decision. In the

late 1940s, U.S. manufacturers sought to cut costs by assembling radios in Japan

and elsewhere. Trans-Pacific technology migration increased steadily as U.S.

firms, hoping to reduce their costs even further, encouraged Japanese and other

manufacturers to develop capabilities to manufacture parts. Once the Japanese

internalized these capabilities, they began to develop and sell parts and later

complete receivers in the United States. They started with transistor radios,

which U.S. producers were slow to pursue because they had lower margins and

higher risks than vacuum-tube sets. Not only were the Japanese successful at

vertically integrating forward to compete with former customers, they actually

created a completely new market segment.8

These consumer product manufacturers must not have been astute history

students. If they were, they would have heeded yet another lesson from Henry

Ford, who experienced at least one supplier turning the tables on him. The Dodge

brothers, founders of what is now a division of the Chrysler Corporation, made

their debut in the auto industry as suppliers of gasoline engines to Ford. By 1914,

they had vertically integrated forward to produce entire automobiles and were

competing directly with Ford.9

These sagas and many others illustrate the danger in applying the classical

cost-oriented make-or-buy decision process; i.e., basing sourcing decisions

primarily on cost, with insufficient regard for strategic imperatives, including

evaluating a supplier's or licensee's potential to become a competitor.

25

This content downloaded from

14.139.218.161 on Mon, 19 Oct 2020 05:16:24 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Academy of Management Executive

In contrast, an inspiring sourcing story comes from Lifeline Systems, Inc., a

Watertown, Massachusetts firm that manufactures emergency-response

communications equipment. By early 1991, after achieving tremendous success

with internal productivity improvements, Lifeline was able to repatriate all its

offshore manufacturing. ?

The Strategic Sourcing Model

What is the correct structure of the make-or-buy decision? The cost accounting

component provides one dimension of the answer. However, even this relatively

straightforward analysis can be mishandled. A true cost analysis includes a

rigorous examination of the assumptions that govern overhead costs. Questions

management must be able to answer include: How are overhead costs

determined? Is allocation used? What effect will outsourcing a product currently

made in-house have on the cost structure of remaining products? Conversely,

what effect will manufacturing a purchased product-in-house have on the cost

structure of this and other products made in-house?

When evaluating a sourcing decision, however, managers must consider more

than just manufacturing costs; in fact, all the factors involved in developing and

introducing products must be considered. These include design, R&D, engineering,

manufacturing, and assembly. The sourcing decision should also consider the

technology positions of competitors and potential competitors.

A conceptual framework known as the Strategic Sourcing Model (SSM) has been

developed to help managers account for these strategic and technological factors.

By examining various dimensions of the process technologies involved in the

sourcing decision, a firm can avoid the pitfalls of the classical make-or-buy

exercise where cost alone is used as a decision variable. To achieve this end, the

SSM examines:

* Process technology's role in providing competitive advantage

* Maturity of the process technologies under consideration

* Competitors' process technology positions

Process Technology's Role in Competitive Advantage

When sourcing decisions are examined, managers must ask themselves whether it

will be detrimental to their firm's competitive position to outsource R&D, design,

engineering, manufacturing, or assembly, both in the short term and in the long

term. Managers must determine the importance of process technology in attaining

and/or sustaining competitive advantage. Examples of process technologies that

have a high degree of importance in providing competitive advantage include:

near-net shape casting and forging in the automotive industry, assembly of

surface-mount devices for circuit boards in the computer industry, and diffusion

bonding in the orthopedic implant industry. Examples that typically rank low

today include: conventional green-sand casting of cast iron for automotive power

trains, conventional soldering of copper-brass radiators, and Dual In-line Package

(DIP) assembly used in circuit boards for the computer industry. Managers must

also consider a forecast of those technologies that have the potential to provide

significant competitive advantage in the future. Examples of these include: the

lost-foam casting process for making magnesium engine blocks for automobiles,

Tape Automated Bonding (TAB) for circuit board assembly in the computer

industry, and processing of composites for orthopedic implants (Exhibit 2).

While the examples offered here fall largely within the manufacturing arena, the

concept of "process technology" is truly broader in scope, applying to processes

like product development and supply chain management. Since these processes

can be done internally or "bought" and since they can provide competitive

advantage, they can also be considered within the framework presented here.

26

This content downloaded from

14.139.218.161 on Mon, 19 Oct 2020 05:16:24 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Welch and Nayak

Industry/segment Low today (base technology) High today (key technology) High in the future (pacing technology)

Automobile power trains Product design isolated from Stand-alone software for Design for DFM and DFA software integrated with

manufacturing requirements Manufacturability (DFM) and Design for CAD/CAM systems

Assembly (DFA)

Automobile radiators Soldering of copper-brass Vacuum/NOCOLOK brazing of aluminum Advanced brazing techniques

Automobile bodies Spot welding of unitized steel Processing of unitized steel/aluminum hybrid Processing of all-composite space-frames

Automobile engine blocks Green-sand casting Near-net shape casting/forming Lost-foam casting of magnesium

Computers (circuit boards) Dual In-line Package (DIP) assembly Assembly of surface-mount components Tape Automated Bonding

Industrial controls Numerical Control (NC) Programmable Logic Control (PLC) Adaptive control

Orthopedic implants Investment casting Diffusion bonding Processing of composite materials

Exhibit 2. Significance of Process Technologies for Competitive Advantage-Industry Examples

Once the significance of the process technology for attaining and/or sustaining

competitive advantage is determined as low today, high today, or potentially high

in the future, the major abscissa range is known for positioning within the SSM

(Exhibit 3).

Maturity of the Process Technologies under Consideration

To determine the corresponding ordinate range for positioning within the SSM,

managers must evaluate the maturity of the process technology under

consideration-not just in their own industry, but across all industries. For

example, while composites are still emerging or embryonic in the orthopedic

implant industry, they are widely used in the aerospace and sporting goods

sectors. If the process technology is undeveloped or unavailable in your own

industry, other industries should be scanned to determine the relative maturity of

the process technology in a global sense. Do not invest in R&D to reinvent the

proverbial wheel.

Competitors' Process Technology Positions

Managers considering outsourcing must rigorously evaluate their firm's technology

position vis-a-vis that of the competition. This analysis involves a structured

Minor abscissa -

Your process technology relative to competitors

Weak Tenable Superior Weak Tenable Superior Weak Tenable Superior

Emnerging/ vX _ _

emnbryonic

Growth Buy

0

E ~~~~~Low today High today High In the future

Significance of proces technology for compettive advantage

Maior abscissa ->

Exhibit 3. Strategic Sourcing Model|

27

This content downloaded from

14.139.218.161 on Mon, 19 Oct 2020 05:16:24 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Academy of Management Executive

benchmarking approach similar to that described by Camp or Scharlacken and

Greene. 1 ' This procedure will differ by industry, as can the metrics used to rank

your firm versus the competition. Probably the most widely used metric for this

analysis is "cost per unit." Other underlying metrics include: unit output per

If the process worker-hour, unit output per machine-hour, defects in parts per million, or

technology is material usage per unit. Even knowing the number of process engineers per

undeveloped or product line is useful when comparing your position to that of your competitors.

unavailable in your Once you have determined your firm's relative technology position, the minor

abscissa coordinate is known for positioning within the SSM. In the context of a

own industry, other

key sourcing decision, knowing your competitors' technology positions is as

industries should be

important as knowing their market shares.

scanned to determine

the relative maturity

of the process Sourcing Decisions Involving Proprietary Technology

While the potential exists to lose your technological edge through outsourcing key

technology in a

processes, it can also be lost through licensing arrangements, joint ventures, or

global sense.

reverse-engineering. The ramifications of exposing and ultimately compromising

important technology should be weighed heavily in the outsourcing decision. It is

unwise to assume that a less developed subcontractor is incapable of learning

and innovating.

The "Cost of Quality" in a Sourcing Decision

Quality is extremely important in the sourcing decision. Leading manufacturers

have become skilled at quantifying quality and its associated costs. This

framework, the "cost of quality," provides a meaningful way to consider quality in

the sourcing decision. 12 Poor quality will cost more, whether it is manifested as

scrap, rework, customer returns, recalls, warranty costs, complaints, or general

customer dissatisfaction leading to foregone business and share. These factors can

be quantified and accounted for in the sourcing decision. To determine a potential

supplier's quality performance, a priori, progressive manufacturers evaluate the

supplier's processes, not just prototypes or sample parts. Quality should be

quantified and incorporated into the make-or-buy decision as costs or cost

avoidances. If a supplier's quality performance results in a cost difference vis-d-vis

in-house manufacture, then this cost difference must be considered in the

make-or-buy decision. A premium price from a supplier can be justified if there is

commensurate reduction in the categories of scrap, rework, returns, recalls, or

warranty costs.

In the context of a key Sourcing Decision Frequency

sourcing decision, The recommended frequency of the make-or-buy decision will differ by industry,

knowing your technology, and specific input, as well as varying with economic cycles. In

competitors' extremely dynamic industries, such as semiconductors, decisions will require more

frequent reassessments. Conversely, the analysis by a punch press manufacturer

technology positions is

as to whether to make or buy crankshafts a strategic but mature input-will

as important as

have a much longer decision cycle.

knowing their market

shares.

Making the Final Decision

After following the model's guidelines and locating the applicable cell in the

matrix, the tentative sourcing decision will be one of the following: make,

marginal make, develop internal capability, buy, marginal buy, or develop

suppliers.

Make and marginal make: For technologies that provide significant competitive

advantage but are not mature-and therefore not readily available-the

preferred decision is to internalize the technology and develop it, thus preventing

the competition from benefiting from it as well. These "make" technologies will

embody the core competencies of the firm. Honda's core products, for example,

are internal combustion engines and power trains. Honda does not outsource

28

This content downloaded from

14.139.218.161 on Mon, 19 Oct 2020 05:16:24 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Welch and Nayak

these critical items because the ability to design and build them is the very heart

of its competitive advantage. 13

However, if the firm is technologically weak in the area under consideration, the

decision to internalize is only marginal. As a result, the firm must choose between

investing to develop its own capability and outsourcing the technology. Ultimately,

all marginal decisions should be examined collectively, thereby allowing priorities

to be set. Riskier investments should be few and focused to avoid exposure and to

facilitate clear evaluation of their effectiveness.

A premium price from Develop internal capability: Technologies that promise future advantage but are

a supplier can be still emerging or embryonic-and therefore not available elsewhere-should be

justified if there is nurtured through emphasis on R&D. Well-established conceptual frameworks and

commensurate specific techniques exist which ensure that a firm has a strategically balanced

portfolio of R&D work. This approach embodies a structured process for R&D

reduction in the

analysis and planning, empowering a company to: set project goals and priorities,

categories of scrap,

allocate resources among R&D efforts, measure results, and evaluate progress. 14

rework, returns,

recalls, or warranty

Buy: In cases where competitive advantage provided by a technology is low

costs.

today, outsourcing is indeed a prudent decision. Used judiciously, outsourcing

allows a firm to leverage its own capabilities by focusing resources on high

value-added activities. For example, scarce management talent and time should

not be wasted on activities that do not add unique value. In addition, outsourcing

provides the potential to reap economies of scale through specialized suppliers. In

cases where the input has historically been made internally, but is now evaluated

as a candidate for outsourcing, the value of further investments in the associated

technology should be critically examined and weighed vis-d-vis outsourcing.

Marginal buy: Mature technologies that provide significant competitive advantage

are typically those that have been developed in other industries. An example of

this is fermentation technology, which was developed in the brewing industry and

later applied to biotechnology. If licensing is economically feasible and the firm

has demonstrated the ability to integrate and assimilate externally developed

technologies, then the technology should be purchased. Otherwise, outsourcing is

again a prudent decision, although this will typically involve developing a

supplier that is currently participating in another industry.

Used judiciously, Develop suppliers: Mature technologies that will become important in the future

outsourcing allows a should be considered as candidates for outsourcing, with the added objective of

firm to leverage its developing suppliers. Even if the firm has already developed internal capabilities,

own capabilities by there will inevitably be suppliers-in other industries where the technology has

become mature-who have further traversed the experience curve. Therefore,

focusing resources on

competitors will soon gain access to the technology, and the time window of

high value-added

advantage will be relatively narrow. This decision holds even if the technology is

activities.

in a growth stage in other industries and your firm's competence in the given

technology is weak. The investment required to gain parity can be better applied

elsewhere.

A Progressive Sourcing Decision

An example of an enlightened-although difficult-outsourcing decision is one

made by Ford Motor Company many years after the Henry Ford era. Ford owns

twenty-five percent of Mazda and has had a long relationship of product

co-development with them, including the 1988 Probe and Festiva models. As part

of its more recent CT 20 project, Ford outsourced product development to Mazda

and then relied upon this company for valuable manufacturing help. Even with its

equity position in Mazda, Ford's outsourcing was subject to certain key conditions:

29

This content downloaded from

14.139.218.161 on Mon, 19 Oct 2020 05:16:24 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Academy of Management Executive

Products

Efforts were limited to subcompact and compact cars only, recognized as the

Japanese firm's strong suit, but admittedly not Ford's. In the CT 20 project, the

platforms for the Ford Escort and Mercury Tracer were developed by Mazda in

Hiroshima, Japan, using the same platforms as the Mazda 323 and Protege.

Involvement and Learning

Ford engineering and management staff were on-site in Hiroshima and were

actively involved in the new product development for CT 20, facilitating

organizational learning.

Technology Transfer

Ford builds the Escort and Tracer models in two different plants: Hermosillo,

Mexico, and Wayne, Michigan. The Hermosillo plant is an exact copy of Mazda's

plant in Hofu, Japan, where the 323 and Protege models are made. Mazda was

heavily involved in establishing this plant, adapting Japanese philosophies and

practices to local political, cultural, linguistic, and geographical conditions, thus

obviating the excuse that "it can't work here." Even with lower wage rates and

higher labor turnover than any U.S. plant, Hermosillo generates the highest

quality of any Ford assembly plant in North America. Subsequently, the Wayne

operations have been modified to capitalize on the Hermosillo plant's experience.

Conclusion

The sourcing dilemma-to buy or not to buy-is of central importance. While cost

is always important in any business decision, managers should consider strategic

and technological issues in conjunction with the decision. Companies that

continue to make sourcing decisions based solely on cost will eventually wither

and die, as many already have. Conversely, thoughtful use of the strategic

sourcing model, in conjunction with a rigorous cost analysis, can help companies

make the sourcing decisions that will move them toward world-class stature.

Endnotes The authors would like to thank their clients Strategy and Supplier Involvement on Product

and their colleagues at Arthur D. Little, Inc. for Development," Management Science, volume

helpful comments and suggestions. The authors 35, number 10, October 1989, 1247-1263.

would also like to thank Professor Joseph 3Purchased inputs include both goods and

Blackburn and Professor Germain Boer of services. Labor costs are the wages paid to

Vanderbilt University's Owen Graduate School production workers. U.S. Department of

of Management. Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Census of

' In its heyday, vertical integration Manufactures 1987 and Annual Survey of

associated with the River Rouge facility Manufactures. Washington, DC, 1986, 1988.

included: iron ore and coal mines, a dedicated 4 Grant Thornton, Grant Thornton

railroad, 20 diesel locomotives, two 600-foot Manufacturing Climates Study (9th edition).

ore-carrying ships, three blast furnaces, one (Chicago, IL: Prentice Hall, July 1988), 168, 170

basic oxygen furnace, foundry, engine plant, (prepared by Leo Troy).

tool and die plant, stamping plant, glass plant, 5 This figure is a count of GM's direct

assembly plant, and power-generation material suppliers for its North American

capability. Ford Motor Company Public manufacturing plants. It does not include

Relations, The Rouge. Dearborn, MI: November, suppliers of spare parts and MRO items. This

1977. information was obtained through private

2 A study of product development in the auto correspondence with Lorrie Janis, Coordinator

industry found that "supplier involvement of Supplier Assessment and Development;

accounts for about one-third of the advantage General Motors Purchasing Activities, Supplier

in labor hours and four to five months of the Development & Systems; Detroit, MI; October 5,

lead time advantage" that Japanese firms hold 1989.

over their U.S. competitors in the race to 6 Data for Exhibit 1 were adapted from the

introduce new products and that "much of the following sources: IMD International (Lausanne,

difference we observe has to do with the Switzerland) and The World Economic Forum

engineering capabilities in the supplier (Geneva, Switzerland), The World

network, and the ability of the [Japanese] auto Competitiveness Report 1990, Geneva,

firms to both nurture and capitalize on that Switzerland: 10th Edition, 1990, table 2.04;

capability." Kim B. Clark, "Project Scope and International Labor Organization, Yearbook of

Project Performance: The Effect of Parts Labor Statistics 1978. Geneva, Switzerland,

30

This content downloaded from

14.139.218.161 on Mon, 19 Oct 2020 05:16:24 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Welch and Nayak

1978. table 17A; Intemational Monetary Fund, High-Tech Company Makes a Huge Leap in

International Financial Statistics Yearbook 1982. Quality." Business Week, May 20, 1991, 128.

Washington. D.C., 1982, passim; and "Foreign " Benchmarking is treated thoroughly by:

Exchange," The Wall Street Journal, June 28, Robert C. Camp, Benchmarking: The Search for

1974, 34. Industry Best Practices that Lead to Superior

7 Product designs can be enhanced through Performance (Milwaukee, WI: ASQC Quality

concurrent engineering and use of techniques Press, 1989). Also refer to: John Scharlacken and

such as Design for Assembly (DFA) and Design Alice Greene of Arthur D. Little, Inc.,

for Manufacture (DFM). While previous product Competitive Benchmarking: A Tool for Helping

designs may have made automation infeasible, Companies Become World Class (Cambridge,

the manufacturing processes for these MA: Arthur D. Little, Inc.), Manufacturing Notes,

re-designed products can be easily automated. Volume 3, No. 2, 1991.

8 Michael Dertouzos, Richard Lester. Robert 12 The cost of quality is treated

Solow, and the MIT Commission on Industrial philosophically and conceptually by Philip

Productivity, Made in America: Regaining the Crosby, Quality is Free (New York, NY:

Productive Edge (Cambridge, MA: The MIT McGraw-Hill, 1979), 15, 115. For rigorous

Press, 1989). 222. examples of cost of quality analyses, see

9 This information was obtained through Joseph Juran, Juran's Quality Control Handbook

private correspondence with Brandt (4th edition) (New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 1988),

Rosenbusch, Corporate Archivist, Chrysler 4.1-4.30.

Historical Foundation; Highland Park, MI; 13 The concept of core competencies is

September 13, 1991. The story is also explained by: C.K. Prahalad and Gary Hamel,

documented by: Ford Whitman Harris and "The Core Competence of the Corporation,"

Harry Franklin Porter, "Deciding Whether to Harvard Business Review, May-June 1990, 79-91.

Buy or Make" from The Library of Factory 14 Please refer to: Philip Roussel, Kamal

Management, Volume III: Materials and Saad, and Tamara Erickson of Arthur D. Little,

Supplies, (Chicago. IL: A.W. Shaw Company, Inc., Third Generation R&D: Managing the Link

1915), 49-50. to Corporate Strategy (Boston, MA: Harvard

" This example was taken from: "A Small Business School Press, 1991).

About the Authors James A. Welch is a senior consultant for Arthur D. Little, Inc., where he

specializes in manufacturing strategy with an emphasis on supplier

management, manufacturing planning and control, facilities planning, and

Just-In-Time manufacturing. Mr. Welch earned his M.B.A. from Vanderbilt

University's Owen Graduate School of Management and his B.S. in mechanical

engineering from The University of Michigan. Mr. Welch is certified in

production and inventory management (CPIM) by the American Production and

Inventory Control Society (APICS). Mr. Welch serves on the Alumni Board of

Directors for the Owen Graduate School of Management at Vanderbilt

University.

P. Ranganath Nayak is a senior vice president at Arthur D. Little, Inc.,

where he is responsible for the company's worldwide operations management

consulting practice. Dr. Nayak is co-author of the book Breakthroughs! (Rawson

Associates, New York, 1986), and is currently writing a book on product creation

and productivity improvement. Dr. Nayak received his Ph.D. in mechanical

engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

31

This content downloaded from

14.139.218.161 on Mon, 19 Oct 2020 05:16:24 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- 339 - DADMB End TermDocument3 pages339 - DADMB End TermrafNo ratings yet

- 365 - End Term BS 2020Document4 pages365 - End Term BS 2020rafNo ratings yet

- Strategic Sourcing To Make or Not To Make PDFDocument13 pagesStrategic Sourcing To Make or Not To Make PDFrafNo ratings yet

- Section B - SCM - Mid Term MarksDocument2 pagesSection B - SCM - Mid Term MarksrafNo ratings yet

- MBA 2019-21 Batch Term-V Class ScheduleDocument1 pageMBA 2019-21 Batch Term-V Class SchedulerafNo ratings yet

- Social Leaders Program PDFDocument1 pageSocial Leaders Program PDFrafNo ratings yet

- Post-Graduate Programme in Management (MBA) : Indian Institute of Management RanchiDocument3 pagesPost-Graduate Programme in Management (MBA) : Indian Institute of Management RanchirafNo ratings yet

- DADMB MarksDocument3 pagesDADMB MarksrafNo ratings yet

- LinkedIn Campaign Manager PDFDocument3 pagesLinkedIn Campaign Manager PDFrafNo ratings yet

- Behavioral & Psychographic Segmentation - How To Develop Buyer PersonasDocument6 pagesBehavioral & Psychographic Segmentation - How To Develop Buyer PersonasrafNo ratings yet

- LinkedIn Campaign Manager PDFDocument3 pagesLinkedIn Campaign Manager PDFrafNo ratings yet

- EfsdfDocument6 pagesEfsdfrafNo ratings yet

- GE IndustryDocument1 pageGE IndustryrafNo ratings yet

- Course Outline Marketing Management-IDocument4 pagesCourse Outline Marketing Management-IrafNo ratings yet

- Marketing - Module 2 PDFDocument44 pagesMarketing - Module 2 PDFrafNo ratings yet

- Marketing - Module 2 PDFDocument44 pagesMarketing - Module 2 PDFrafNo ratings yet

- Technology For GDDocument14 pagesTechnology For GDrafNo ratings yet

- EfsdfDocument6 pagesEfsdfrafNo ratings yet

- Revised - Queuing Theory FormulaDocument4 pagesRevised - Queuing Theory FormularafNo ratings yet

- Business Model Canvas PosterDocument1 pageBusiness Model Canvas PostersunnyNo ratings yet

- Business Model Canvas PosterDocument1 pageBusiness Model Canvas Posterosterwalder75% (4)

- Revised - Queuing Theory FormulaDocument4 pagesRevised - Queuing Theory FormularafNo ratings yet

- 674 1661 1 PBDocument4 pages674 1661 1 PBrafNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- 3.3 Motherboard SchematicsDocument49 pages3.3 Motherboard SchematicsJoanna WęgielNo ratings yet

- Online Banking TCsDocument52 pagesOnline Banking TCsmaverick_1901No ratings yet

- Publication PDFDocument20 pagesPublication PDFBhaumik VaidyaNo ratings yet

- Deguzman Vs ComelecDocument3 pagesDeguzman Vs ComelecEsnani MaiNo ratings yet

- Sonos Outdoor by Sonance Installation ManualDocument4 pagesSonos Outdoor by Sonance Installation Manualvlad111No ratings yet

- TT21 28112019BNN (E)Document40 pagesTT21 28112019BNN (E)Thanh Tâm TrầnNo ratings yet

- CH 121: Organic Chemistry IDocument13 pagesCH 121: Organic Chemistry IJohn HeriniNo ratings yet

- Dialer AdminDocument5 pagesDialer AdminNaveenNo ratings yet

- Forcep DeliveryDocument11 pagesForcep DeliveryNishaThakuriNo ratings yet

- Type Italian Characters - Online Italian KeyboardDocument3 pagesType Italian Characters - Online Italian KeyboardGabriel PereiraNo ratings yet

- Laboratory Activity 1CDocument4 pagesLaboratory Activity 1CAini HasshimNo ratings yet

- Primax Solar Energy CatalogueDocument49 pagesPrimax Solar Energy CatalogueSalman Ali QureshiNo ratings yet

- Rural MarketingDocument25 pagesRural MarketingMohd. Farhan AnsariNo ratings yet

- Value For Money Analysis.5.10.12Document60 pagesValue For Money Analysis.5.10.12Jason SanchezNo ratings yet

- Impromptu SpeechDocument44 pagesImpromptu SpeechRhea Mae TorresNo ratings yet

- Math 7 LAS W1&W2Document9 pagesMath 7 LAS W1&W2Friendsly TamsonNo ratings yet

- Questão 13: Technology Anticipates Fast-Food Customers' OrdersDocument3 pagesQuestão 13: Technology Anticipates Fast-Food Customers' OrdersOziel LeiteNo ratings yet

- Autodesk 2016 Product Keys 1Document3 pagesAutodesk 2016 Product Keys 1EfrEn QuingAtuñaNo ratings yet

- Executive MBA Project - Self Help Allowance - FinalDocument55 pagesExecutive MBA Project - Self Help Allowance - FinalKumar SourabhNo ratings yet

- A Woman Who Is at 36 Weeks of Gestation Is Having A Nonstress TestDocument25 pagesA Woman Who Is at 36 Weeks of Gestation Is Having A Nonstress Testvienny kayeNo ratings yet

- Swash Plate Leveling Tool Instructions: Trex 600 Electric & NitroDocument3 pagesSwash Plate Leveling Tool Instructions: Trex 600 Electric & NitroEdinal BachtiarNo ratings yet

- 304 TextsetlessonDocument18 pages304 Textsetlessonapi-506887728No ratings yet

- h110m Pro VD Plus User GuideDocument19 pagesh110m Pro VD Plus User GuideIgobi LohnNo ratings yet

- A Simple and Convenient Synthesis of Pseudo Ephedrine From N-MethylamphetamineDocument2 pagesA Simple and Convenient Synthesis of Pseudo Ephedrine From N-Methylamphetaminedh329No ratings yet

- 2003 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.: Max VisserDocument10 pages2003 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.: Max VisserMariano DomanicoNo ratings yet

- Questionnaire On Teaching Learning 1Document4 pagesQuestionnaire On Teaching Learning 1Sonia Agustin100% (1)

- C1036 16Document10 pagesC1036 16masoudNo ratings yet

- Oops MCQ (Unit-1)Document7 pagesOops MCQ (Unit-1)Jee Va Ps86% (14)

- Literature Review Topics RadiographyDocument8 pagesLiterature Review Topics Radiographyea7w32b0100% (1)

- Spark RPG Colour PDFDocument209 pagesSpark RPG Colour PDFMatthew Jackson100% (1)