Professional Documents

Culture Documents

BB The Design of It Patterns in Pibroch 2005-Ii

Uploaded by

HD POriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

BB The Design of It Patterns in Pibroch 2005-Ii

Uploaded by

HD PCopyright:

Available Formats

MUSIC

The Design of It:

Patterns in Pibroch

The secret to composing, memorizing, and

appreciating ceol mór. (Part II)

by Barnaby Brown

GEOMETRICAL AND LYRICAL The contrast in sonority between played before competitions replaced

PRINCIPLES A and B phrases can be either slight or this genre’s original performance con-

There are two opposite forces in pi- bold. A popular work in the eighteenth text: the gathering of warriors, or their

broch design. “Geometrical” principles century, “War or Peace,” uses bold encouragement in battle.

of pattern, order and symmetry have contrast to produce a more battle-like

one effect on the brain, while “lyrical” effect. In Example 3a, the A phrase uses LYRICAL INTERLACED

principles of spontaneity and tuneful- the consonant notes A-C-E, to contrast

ness have quite another effect. In the with the dissonant sonority of the B ��������������

Ùrlar of most pibrochs, geometrical phrase (highlighted in red), which lies ����� ��������

and lyrical principles operate in part- on the notes G-B-D, clashing with the

nership, but in some works, the Ùrlar drones. The four repetitions of “ho- The lyrical principal comes to the fore

is relentlessly geometrical, devoid of droha” in the 4th eighth are answered in the Lyrical Interlaced Ùrlar design

melody. Only in a couple of instances by the four “haninun” beats in the last family, which includes “Lament for

is the Ùrlar a pure, uncomplicated eighth. “Haninun” in MacCrimmon the Children” (3: 99), “Hiotrotraho

tune, without any intellectual clever- canntaireachd corresponds to “hiharin” hiobabem” (15: 535), “Salute to Don-

ness. Generally, professional pipers of in Campbell notation. ald” (8: 229) and “The Pretty Dirk”

the seventeenth century showed off This is one of several instances in (11: 318). It is closely related to the

their skill in the craft of composition, pibroch where an editor—in this case, Interlaced design, with the distinction

producing results that are comparable Angus MacKay—has wrongly recon- that here the 2nd quarter is a repeat

in intricacy and sophistication to the structed a lacuna, or memory lapse. of the 1st quarter, and the final eighth

designs found in the metalwork, sculp- Example 3a was transcribed by Niel recalls the 1st eighth. “Hihorodo

ture, and poetry of the Gaelic culture MacLeod of Gesto from the chanting hao” (Example 4) is an example of

of the time. of Iain Dubh MacCrimmon (c.1731– outstanding melodic beauty, and it is

c.1822), and corresponds with the staff unfortunate that such short works find

INTERLACED notation of the other sources, with one no performance outlet today outside

small exception: it is unique in hav- the rare recital. Modern institutions of

�������������� ing 5 “hodroha”s in succession. Other

������������� training and patronage devalue works

sources have 4 “hodroha”s (“hiotraha” that do not fit the twentieth-century

In the Interlaced family of musical de- in Campbell notation), leaving the 5th competition mould. As a result, about

signs, geometrical and lyrical principles eighth a beat short. This is probably 25 per cent of the pibroch repertoire is

operate hand in hand. Key works in what MacKay was taught. In Example still unpublished.

this family are (with their Piobaireachd 3c, Patrick MacDonald made up the The Lyrical Interlaced design

Society Book and page numbers) “The missing beat in the measure by adding family has much in common with the

MacDonalds’ Salute” (11: 340), “A a rest. In Example 3d, we see that this rounded binary or sonata forms that have

Flame of Wrath for Patrick Caogach” rest has been replaced by a low A note. dominated Western classical music

(5: 139), “Lament for MacSwan of There can be little doubt that this is since the early eighteenth century. The

Roaig” (1: 39), “The Old Men of the Angus MacKay silently improving what 1st quarter of the Ùrlar corresponds

Shells” (7: 207), and “Lament for the he had been taught. In this case, he has to the exposition of sonata form, which

Castle of Dunyveg” (1: 25). Fundamen- corrupted the phrase, transforming its is normally repeated. In the case of

tal to the Interlaced design is a strong identity from B to A. “Hihorodo hao,” though, there is a

cadence on B in the 4th eighth, normal- “War or Peace” is an exciting touch of genius: one note is lifted up a

ly ending on repeated “hihorodo” beats. musical work when liberated from scale step on the repeat (highlighted in

These are answered in the last eighth by the trappings of modern competition Example 4, phrase A2). In sonatas and

repeated “hiharin” beats on low A. style, which do not suit it. It was widely Lyrical Interlaced movements, the sec-

44 The Voice • Spring 2005

MUSIC

ond half begins with a development sec- design group conveniently includes schema is of sufficient interest in itself

tion, C-, which can extend into some works that don’t fit into any other cat- that, often, little or no modification of

or all of the 6th eighth—hence the dash egory. It is, in effect, a set of variations the component phrases occurs—they

between C and A in the schema. When on the 1st quarter. This theme within are simply repeated according to the

the opening material re-emerges, -A B a theme is reworked and transformed schema. This is the case in “Struan

A’, this is known as the recapitulation. in the course of the Ùrlar, just as the Robertson’s Salute” (Example 6), which

Unlike most sonatas, the recapitulation Ùrlar is reworked and transformed in is also typical in having a B phrase that

of Lyrical Interlaced works is dovetailed the course of the pibroch. Well-known climbs higher than the A phrase. Other

into the development, creating a seam- examples of this design are “The Finger examples include “Lament for the Old

less melodic flow. The dovetail joint in Lock” (1: 8), “The MacLeods’ Salute” Sword” (3: 77), “The Pride of Barra”

Example 4 (phrase A3) is a fine example (12: 372), “Lament for Donald of Lag- (5: 151), and “Lament for Patrick Og

of melodic craftsmanship. gan” (8: 219), and “Lament for Mary MacCrimmon” (3: 83).

The last eighth of the schema, A’, MacLeod” (5: 155).

has an apostrophe mark because the “The Unjust Incarceration” (2: 42) PHRASE ELONGATION

recapitulation always incorporates a has a 5th “quarter,” and perhaps this In many types of music, composers do

surprise, something to startle the lis- is the composer, Iain Dall, expressing not want phrase lengths to be regular

tener. Western classical composers did indignation against authority, but it throughout the composition. In most

exactly the same thing, generating mu- provides one of the clearest examples dance music, regularity of phrase is es-

sical shocks of varying kinds to keep the of the progressive, dramatic build-up sential, but in pure music, like pibroch,

audience engaged, and to announce the typical of this group. Each of its five there is no such requirement. On the

end of a formal unit. The surprise event “quarters” grows out of the previous contrary, techniques to vary phrase

in “Hihorodo hao” occurs in the last one, brilliantly evoking human anguish, lengths and metre are found in every

bar where, instead of G-B-D, we have welling up to new emotional heights on great composer’s toolbox. The craft of

A-B-E. This marks the culmination each pass. pibroch is no exception.

of a process in which phrase A is com- Usually, the first two quarters In their pre-MacKay settings, the

pletely transformed in four progressive in Progressive works are identical, or B phrases of “The Piper’s Warning to

steps (highlighted in Example 4). This nearly so, and melodic transformation His Master” are elongated from 4 to

transformation creates a sense of musi- becomes serious only in the second 6 beats (Example 7). This Rounded

cal achievement and has an uplifting half. The most common type of pro- Lyrical design is regular in every other

emotional effect. gression, from quarter to quarter, is the respect, and I am not convinced that

Despite being a small group, the “lifting” of a few notes by one or more the elongation of the B phrases is suf-

works in the Lyrical Interlaced design scale degrees (as seen in the transfor- ficiently unusual in seventeenth-cen-

family are rich in imagination and pro- mation of phrase A in “Hihorodo hao,” tury pibroch to constitute an effective

miscuous in their relationships with Example 4). In Example 5, “Lament “Warning.” A similar thing happens in

other designs. One of several works for the Young Laird of Dungallon,” the “Sir Ewin Cameron of Locheil’s Salute”

that lie on its borderline with other lifted sections are highlighted in red. (Example 8). In each case, the elonga-

design families is “The Marquis of Many Progressive works have a tion is carried through the variations.

Argyll’s Salute,” in its canntaireachd design that is similar to those in the Examples of this type of metrical sport

settings (10: 280). When the “hiharin” Rounded Lyrical design group. The are found in all the major sources, but

and “hihorodo” beats are removed, its crucial distinction comes in the final it is not a compositional technique with

construction is similar to “The Pretty eighth, which in Rounded Lyrical which Angus MacKay or the Piobai-

Dirk” and “Salute to Donald”. Howev- works is a recapitulation, repeating the reachd Society editors were comfort-

er, with the cadential beats in place (as 2nd eighth. Progressive works continue able. Every example of it, apart from

the composer intended), it has equally progressing, right to the end. the variations of “The Parading of the

strong Progressive features. MacDonalds” (7: 217), is suppressed

ROUNDED LYRICAL from the pages of the Piobaireachd So-

PROGRESSIVE ciety Books.

����������������� Compare Example 8 with the

����������� ������������������ Society’s edited version in Book 10,

page 284. Angus MacKay’s original

���������� ���������������������

The Rounded Lyrical design family is a regular Lyrical Interlaced design,

is the largest and most homogenous with a development that fills the 3rd

Due to the simplicity of the schema— of the groups introduced so far. The quarter. As in “Hihorodo hao,” the A

four similar quarters—the Progressive phrase is totally transformed in the final

The Voice • Spring 2005 45

MUSIC

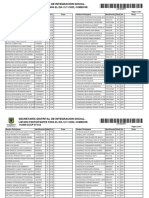

EXAMPLE 3. Interlaced design—“War or Peace.” The Ùrlar uses “hodroha” instead of “hihorodo”

to finish the 4th eighth, but is otherwise typical of the Interlaced design family.

A

B

A

bbbb

B

A

B’

aaaa

Example 3a. From Niel MacLeod of Gesto, A Collection of Piobaireachd or Pipe Tunes, as ver-

bally taught by the McCrummen pipers in the Isle of Skye, to their apprentices, (1828) No.3.

A B…

…A bbb

BA

B’ aaaa

Example 3b. This corresponds with the MacCrimmon canntaireachd above, except that the 4th quarter is a

“hodroho” short—bbb instead of bbbb in the schematic analysis. (Peter Reid’s MS, 1825, folio 11r.).

Example 3c. The 4th eighth, marked in red, corresponds to Gesto’s and Reid’s B phrase, but with an erro-

neous rest inserted by the editor to make up the 4/4 bar. (Patrick MacDonald, A Collection of Highland Vocal

Airs, 1784, p.43.)

46 The Voice • Spring 2005

MUSIC

Example 3d. Angus MacKay replaced Patrick MacDonald’s rest in Example 3c with a low A, creating

an “improved” setting which, far from being traditional, departs significantly from what he was taught.

To agree with the MacCrimmon canntaireachd above, the bar marked in red should be replaced with

phrase B: MacKay’s first time bar. (Angus MacKay, A Collection of Ancient Piobaireachd, 1838 p.128.).

When restoring a twelfth-cen-

A1 tury church, would you make two

arches that were originally dif-

ferent the same? I’m lucky to live

B A2 in Sardinia, where architectural

jewels of that age are readily ac-

cessible. Invention and creativity

explode in these buildings, no

B matter where you set your eyes.

Wherever two things in modern

buildings would be identical, in

Development A33

A medieval buildings they are not.

This increases their natural beauty

and splendor. The pibroch sources

Dovetailed recapitulation B demonstrate unequivocally that

this music operates with medieval

aesthetics, not with the aesthet-

A4 ics of the industrial age that has

subliminally conditioned “devel-

oped” society since the nineteenth

century.

EXAMPLE 4. Lyrical Interlaced design—“Hihorodo hao.” The highlighted sections mark the

gradual transformation of phrase A. From the MacGregor-MacArthur MS, (1820) No.18. John Mac- EVEN OR UNEVEN LINES?

Gregor, a .autist as well as a piper, wrote pipe music down in the key of D. This score is transposed

up a 4th in Frans Buisman’s critical edition (The Music of Scotland 1, 2001, p. 99) and, with Angus The late James Campbell, who

MacKay’s editorial changes, in Piobaireachd Society Book 4, p.111. Note how John MacGregor probably knew the repertoire bet-

divided the Ùrlar into three uneven sections using the sign //. ter than anyone else in his time,

stated that there was very little we

know for sure about pibroch. Seu-

eighth. What is unusual here is that the Piper’s Warning to His Master.” It mas MacNeill was less humble in

A phrases of the first half have 3 beats helps guard against musical monotony. his convictions. In response to Joseph

(marked in red). Although I would Perhaps we need to remind our- MacDonald’s statement, circa 1761,

move Angus MacKay’s barlines to make selves that pibroch is pre-Industrial that, “Their Adagios when regular,

the phrase construction clearer to the Revolution. The “factory-standard” commonly consisted of 4 quarters,”

eye, I do not agree with the statement mentality that age engendered in all Seumas wrote:

in Book 10, that “the setting of Angus matters of construction—visual and An attempt has been made to fit some

MacKay is full of defects.” On the con- musical—is foreign to pibroch. Such three-line tunes to this “four quarters” pat-

trary, phrase elongation is an important editorial “improvements” are degrad- tern, but although the exercise is attractive

technique, used by Gaelic composers ing, and show a lack of respect to the to a numerologist it is musically unsound.

with great success in works like “The original composers. Angus MacKay wrote piobaireachd in three

The Voice • Spring 2005 47

MUSIC

lines, and for the piper there is no other EXAMPLE 5. Progressive design—“The Young Laird of Dungallon’s Lament.”

way to play them. (Piobaireachd, 1968,

p.66)

Angus MacKay was not alone in

dividing Interlaced and Woven designs

into uneven lines, starting and/or end-

ing with the same phrase: so did Colin

Campbell in 1797, and John Mac-

Gregor in 1820. It is an obvious thing

to do. Whether it is more musical, or

whether it corresponds with seven-

teenth-century MacCrimmon thinking,

is wide open to question.

Try it yourself with “War or

Peace” and “Hihorodo hao.” Do you

prefer the uneven arrangement (marked

in Examples 3d and 4 by the sign //

above the bar line)? In Example 3, the

uneven sections start with phrase A:

Ex. 3: A B, A bbbb B, A B aaaa

whereas in Example 4, they end with Example 5a. From Colin Campbell’s Instrumental Book, (1797), Vol. II, No.52 (and No.86).

phrase A:

Ex. 4: A1 B A2, B C A3, B A4

Or do you prefer the even arrange-

ment?

Ex. 3: A B A bbbb, B A B aaaa

Ex. 4: A1 B A2 B, C A3 B A4

Do you agree with Seumas MacNeill

that there only one way for the piper to

arrange these phrases?

We must choose whether to follow

the evidence of Joseph MacDonald on

this point, or that of Colin Campbell,

John MacGregor, and Angus MacKay.

It affects how we compose, memorize,

and appreciate this music. How it is

written down is not a reliable guide to

Example 5b. My edition of Campbell’s score in Example 5a. The “lifted” sections of melody

the mind of the composer. The writing

are highlighted in red.

down happened, on average, about 150

years after the composition. How we

internalize and teach pibroch is what open minded to realize that the tunes aren’t cult ritual that we’re somehow all initiated

matters. necessarily the way our teachers taught into. (Proceedings of the Piobaireachd Soci-

As Malcolm McRae said at the them to us. There’s far more even than our ety Conference, College of Piping, www.

1991 Piobaireachd Society Conference, teachers ever dreamt of and I think that piobaireachd.co.uk, 1991)

following a talk by Dr. Roderick Can- this sort of research and perhaps experi- Part III of this series, completing the survey of

non on “The Gesto Canntaireachd”: mentation is to be encouraged. It broadens the pibroch rainbow, will be published in the

There’s a lot we’ll never know, obvi- our minds and makes us approach our Summer issue of The Voice.

ously, but I think we’ve got to be sufficiently music as music, as distinct from some sort of

48 The Voice • Spring 2005

MUSIC

A1 A2 B1

B2 B1 A2

EXAMPLE 6. Rounded Lyrical design—“Struan Robertson’s Salute.” From Angus MacKay

A Collection of Ancient Piobaireachd, (1838) p. 79.

A1 A2

B1

B2

B1

A2

EXAMPLE 7. Phrase elongation—“The Piper’s Warning to His Master.” In this otherwise regular

Rounded Lyrical design, the A phrases have 4 beats, and the B phrases are elongated to last 6 beats.

(Peter Reid’s MS, 1825, folio 3r.).

A B A B’

development B’ conclusion

EXAMPLE 8. Phrase elongation—”Sir Ewin Cameron of Locheil’s Salute.” In this tune, the A phrases in

the .rst half have 3 beats (marked in red), and all the other phrases are elongated to 4 beats. Flexibility of metre

is common in Gaelic music, but, owing to a clash of cultures, most examples have been expurgated from the

pibroch tradition. Although the construction of this Ùrlar is almost the same as Example 4, here Angus MacKay

uses the sign // to arrange the eighths in even quarters. (A Collection of Ancient Piobaireachd, 1838, p.49).

The Voice • Spring 2005 49

You might also like

- A Summary Guide To Solfeggiare The Eighteenth Century WayDocument25 pagesA Summary Guide To Solfeggiare The Eighteenth Century Waymanuel1971No ratings yet

- Level Three Bagpipe MusicDocument46 pagesLevel Three Bagpipe Musicpassioncadet100% (1)

- Deep River - BurleighDocument3 pagesDeep River - BurleighmauricioNo ratings yet

- Quartal and Quintal Harmony PDFDocument12 pagesQuartal and Quintal Harmony PDFRosa victoria paredes wong100% (2)

- Albrecht, Beethoven - Beethoven's Conversation Books Volume 1 Nos 1-8 February 1818 To March 1820Document426 pagesAlbrecht, Beethoven - Beethoven's Conversation Books Volume 1 Nos 1-8 February 1818 To March 1820Jingsi Lu100% (2)

- Chant Manual FR Columba KellyDocument115 pagesChant Manual FR Columba KellyCôro Gregoriano100% (1)

- Beatles AnalysisDocument751 pagesBeatles Analysislparrap100% (8)

- Henry IV Part1 Teacher's GuideDocument24 pagesHenry IV Part1 Teacher's GuideShirley Samuel100% (1)

- Chorus - Test #2Document7 pagesChorus - Test #2Brie WestNo ratings yet

- Bach - The Goldberg Variations - Glen Gould, PianoDocument7 pagesBach - The Goldberg Variations - Glen Gould, PianoGamal AsaadNo ratings yet

- Cadet Snare Drum Instruction Chapter 1Document19 pagesCadet Snare Drum Instruction Chapter 1HD PNo ratings yet

- Cadet Snare Drum Instruction Chapter 1Document19 pagesCadet Snare Drum Instruction Chapter 1HD PNo ratings yet

- Shifted Downbeats in Classic and Romantic MusicDocument15 pagesShifted Downbeats in Classic and Romantic MusicpeacefullstreetNo ratings yet

- The Adagio Mesto of Brahms's Horn Trio, Op. 40: Romantic Distance, Longing, and DeathDocument23 pagesThe Adagio Mesto of Brahms's Horn Trio, Op. 40: Romantic Distance, Longing, and DeathImani Mosley100% (1)

- 1 1a 1 PDFDocument160 pages1 1a 1 PDFwladimir hurtadoNo ratings yet

- Filmfare MagazineDocument91 pagesFilmfare MagazineKrunal JaniNo ratings yet

- CoPipers HighlandDanceTunesDocument29 pagesCoPipers HighlandDanceTunesHD PNo ratings yet

- 16-Port Antenna Frequency Range Dual Polarization HPBW Gain Adjust. Electr. DTDocument7 pages16-Port Antenna Frequency Range Dual Polarization HPBW Gain Adjust. Electr. DTestebanarcaNo ratings yet

- Yi-Fu Tuan Space and PlaceDocument246 pagesYi-Fu Tuan Space and PlaceKalil Sarraff100% (15)

- Graphic Notation (2007)Document35 pagesGraphic Notation (2007)jorgesadII100% (2)

- Brahms - SchicksalsliedDocument12 pagesBrahms - SchicksalsliedYu Hang TanNo ratings yet

- Murgatroyd Tutor Vol 1Document70 pagesMurgatroyd Tutor Vol 1HD PNo ratings yet

- Hugo Leichtentritt Musical Form The Contrapuntal FormsDocument18 pagesHugo Leichtentritt Musical Form The Contrapuntal FormsmaandozaNo ratings yet

- Music Theory Spectr 2003 Hanninen 59 97Document39 pagesMusic Theory Spectr 2003 Hanninen 59 97John Petrucelli100% (1)

- Early Twentieth Century MusicDocument33 pagesEarly Twentieth Century MusicBen Mandoza100% (1)

- Composing Intonations After FeldmanDocument12 pagesComposing Intonations After Feldman000masa000No ratings yet

- Steckler Britten Paper PDFDocument12 pagesSteckler Britten Paper PDFjoefreak9000No ratings yet

- Temperament A Beginner's GuideDocument4 pagesTemperament A Beginner's GuideeanicolasNo ratings yet

- Anakreons GrabDocument19 pagesAnakreons GrabEugene Salvador100% (1)

- Mus 642 PDFDocument17 pagesMus 642 PDFOrleansmusicen Ensembles100% (2)

- Codes and Conventions of Musical FilmsDocument5 pagesCodes and Conventions of Musical Filmsapi-295273247No ratings yet

- An Analysis Johann Christian Bach's Piano Sonata in Eb Major, Op. 5/4Document5 pagesAn Analysis Johann Christian Bach's Piano Sonata in Eb Major, Op. 5/4EleanorBartonNo ratings yet

- Frescobaldi, Froberger and The Art of FantasyDocument2 pagesFrescobaldi, Froberger and The Art of Fantasy方科惠100% (1)

- King CrimsonDocument13 pagesKing CrimsonCarouacNo ratings yet

- Appendix Rondo and Ritornello Forms in Tonal Music: by William RenwickDocument8 pagesAppendix Rondo and Ritornello Forms in Tonal Music: by William RenwickApostolos MantzouranisNo ratings yet

- Artigo Peter WilliamsDocument4 pagesArtigo Peter WilliamsRegina CELIANo ratings yet

- Reviving CPE Bach - Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, The Complete Works (Los Altos, CA - Packard Humanities Institute) Vol. I 3Document3 pagesReviving CPE Bach - Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, The Complete Works (Los Altos, CA - Packard Humanities Institute) Vol. I 3annaNo ratings yet

- Haniel's MHS122Test1SubmitDocument5 pagesHaniel's MHS122Test1SubmitHaniel AnugerahNo ratings yet

- ML 83.1.166Document2 pagesML 83.1.166Mattia FogatoNo ratings yet

- G1CS2 Example EssayDocument7 pagesG1CS2 Example Essayhmavro17No ratings yet

- Stephen Dombeck - A Study of Harmonic Interrelationships and Sonority Types in Carl Ruggles' AngelsDocument18 pagesStephen Dombeck - A Study of Harmonic Interrelationships and Sonority Types in Carl Ruggles' AngelsSotiris BetsosNo ratings yet

- AriasDocument2 pagesAriasapi-331053430No ratings yet

- hw11 DallasonnekommtDocument2 pageshw11 DallasonnekommtDan Yapp0% (1)

- Brown JournalAmericanMusicological 1965Document8 pagesBrown JournalAmericanMusicological 1965Thijs ReeNo ratings yet

- Group Performance NotesDocument8 pagesGroup Performance NotesCHRISTIAN HALFPENNYNo ratings yet

- Classical AnalysisDocument52 pagesClassical AnalysisfaniNo ratings yet

- "The Structure, Function, and Genesis of The Prechorus. Music Theory Online 17, No. 3 (2011) .Document13 pages"The Structure, Function, and Genesis of The Prechorus. Music Theory Online 17, No. 3 (2011) .trishNo ratings yet

- Authentic Finalis Plagal ScalesDocument16 pagesAuthentic Finalis Plagal ScalesJulio C. Ortiz Mesias100% (1)

- Encounters With The Chromatic Fourth... Or, More On Figurenlehre, 1Document4 pagesEncounters With The Chromatic Fourth... Or, More On Figurenlehre, 1sercast99No ratings yet

- Tracto Grove OnlineDocument10 pagesTracto Grove OnlineEd CotaNo ratings yet

- Musical Times Publications Ltd. Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To The Musical TimesDocument3 pagesMusical Times Publications Ltd. Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To The Musical Timesbotmy banmeNo ratings yet

- Mendelssohn Piano Trio Op49 Analysis and CommentaryDocument3 pagesMendelssohn Piano Trio Op49 Analysis and CommentaryAudrey100% (1)

- Culture Clash - James Hepokoski Revisits Dvořák's New World Symphony - J. Hepokoski (1993)Document5 pagesCulture Clash - James Hepokoski Revisits Dvořák's New World Symphony - J. Hepokoski (1993)vladvaideanNo ratings yet

- Bach Vs HandelDocument3 pagesBach Vs Handelmartinscribd7No ratings yet

- Session2-3. Fuhrmann Renaissance of Phrygian ModeDocument9 pagesSession2-3. Fuhrmann Renaissance of Phrygian Modeherman_j_tanNo ratings yet

- Early Twentieth Century MusicDocument14 pagesEarly Twentieth Century MusicBen Mandoza100% (1)

- Repertoire 1 TubaDocument2 pagesRepertoire 1 Tubaapi-425535066No ratings yet

- Draft Programme Notes For RecitalDocument2 pagesDraft Programme Notes For RecitalRowena DulayNo ratings yet

- Musicology 2 CullenDocument29 pagesMusicology 2 CullenLuis Carlo LoeraNo ratings yet

- Repertoire 2 TromboneDocument3 pagesRepertoire 2 Tromboneapi-425535066No ratings yet

- 18th Century Thourough BassDocument9 pages18th Century Thourough BassAlessandra RossiNo ratings yet

- Blodget From Manuscript...Document5 pagesBlodget From Manuscript...SilvestreBoulezNo ratings yet

- Schachter (1994) Chopin's Prelude in D Major, Op. 28, No. 5 Analysis and PerformanceDocument19 pagesSchachter (1994) Chopin's Prelude in D Major, Op. 28, No. 5 Analysis and PerformanceAlineGabay100% (1)

- Bailey 03Document7 pagesBailey 03SebastianNo ratings yet

- Mahler 4 PDFDocument7 pagesMahler 4 PDFFrancisco VarelaNo ratings yet

- Schoenberg Meets Slonimsky The SymmetricDocument6 pagesSchoenberg Meets Slonimsky The SymmetricGianluca Salcuni100% (1)

- (Notes Vol. 22 Iss. 2) Review by - Darius L. Thieme - Sounds and Scoresby Henry Mancini (1965) (10.2307 - 894971)Document3 pages(Notes Vol. 22 Iss. 2) Review by - Darius L. Thieme - Sounds and Scoresby Henry Mancini (1965) (10.2307 - 894971)EvaNo ratings yet

- Partimenti Nicola Sala 4Document1 pagePartimenti Nicola Sala 4MatteoMatroneNo ratings yet

- Mahler 10 Study On Different VersionsDocument4 pagesMahler 10 Study On Different VersionsLeonard BogaNo ratings yet

- Powers From Psalmody To TonalityDocument66 pagesPowers From Psalmody To Tonalityn.lloydlamNo ratings yet

- English Verse: Specimens Illustrating its Principles and HistoryFrom EverandEnglish Verse: Specimens Illustrating its Principles and HistoryNo ratings yet

- Hymn - Kilmarock & Harmonies - CummingsDocument1 pageHymn - Kilmarock & Harmonies - CummingsHD PNo ratings yet

- RCAF EO 05-25A-4 Lancaster Parts 1954&58Document1,062 pagesRCAF EO 05-25A-4 Lancaster Parts 1954&58HD PNo ratings yet

- Avro Lancaster Manual 1943 Book - Canadian Warplane Museum Online Gift ShopDocument3 pagesAvro Lancaster Manual 1943 Book - Canadian Warplane Museum Online Gift ShopHD PNo ratings yet

- Avro Lancaster - WikipediaDocument34 pagesAvro Lancaster - WikipediaHD PNo ratings yet

- Lancaster Iiiiii and XDocument27 pagesLancaster Iiiiii and XHD PNo ratings yet

- RAF AP 2062A&C Section 7 - 11 Structure Engines Etc v1 b2 ww2.Document148 pagesRAF AP 2062A&C Section 7 - 11 Structure Engines Etc v1 b2 ww2.HD PNo ratings yet

- Technical StandardsDocument127 pagesTechnical StandardsRomeo ManaNo ratings yet

- Essential Tunes For The PiperDocument12 pagesEssential Tunes For The PiperHD PNo ratings yet

- A CR CCP 907pf 001 Piping Instructional GuideDocument131 pagesA CR CCP 907pf 001 Piping Instructional GuideHD PNo ratings yet

- Andrew Macneill of ColonsayDocument1 pageAndrew Macneill of ColonsayHD PNo ratings yet

- Technical StandardsDocument127 pagesTechnical StandardsRomeo ManaNo ratings yet

- ### RSPBA Language of MusicDocument73 pages### RSPBA Language of MusicHD P100% (1)

- A CR CCP 907pf 001 Piping Instructional GuideDocument131 pagesA CR CCP 907pf 001 Piping Instructional GuideHD PNo ratings yet

- Advanced PDFDocument179 pagesAdvanced PDFSome oneNo ratings yet

- A Practical Introduction To Music TheoryDocument1 pageA Practical Introduction To Music TheoryHD PNo ratings yet

- Cave of Gold: Mcintosh PiobaireachdDocument2 pagesCave of Gold: Mcintosh PiobaireachdHD PNo ratings yet

- BB - Scottish - Traditional - Grounds - Part - 2 - Maol PDFDocument5 pagesBB - Scottish - Traditional - Grounds - Part - 2 - Maol PDFHD PNo ratings yet

- Essay DronesDocument14 pagesEssay DronesHD PNo ratings yet

- Donaldson Set Tunes - Pipes - Drums PDFDocument16 pagesDonaldson Set Tunes - Pipes - Drums PDFHD PNo ratings yet

- BB Binary MeasuresDocument2 pagesBB Binary MeasuresHD PNo ratings yet

- BB Binary MeasuresDocument2 pagesBB Binary MeasuresHD PNo ratings yet

- Musical Traditions: Programme 1 The Pipe Band "All For One"Document6 pagesMusical Traditions: Programme 1 The Pipe Band "All For One"HD PNo ratings yet

- BB Binary MeasuresDocument2 pagesBB Binary MeasuresHD PNo ratings yet

- Musical Traditions: Programme 1 The Pipe Band "All For One"Document6 pagesMusical Traditions: Programme 1 The Pipe Band "All For One"HD PNo ratings yet

- Early Development: Edit EditDocument2 pagesEarly Development: Edit EditKishor RaiNo ratings yet

- Assignment Cover Sheet: Electrical and Computer EngineeringDocument4 pagesAssignment Cover Sheet: Electrical and Computer EngineeringSyahril AmirNo ratings yet

- Saunders - Stigma of PrintDocument54 pagesSaunders - Stigma of PrintkavezicNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3: Magnetron: P.Swetha Microwave Charger PageDocument5 pagesChapter 3: Magnetron: P.Swetha Microwave Charger PageSwetha PvNo ratings yet

- Tosca-RAST-Review-Pieter Verstraete PDFDocument4 pagesTosca-RAST-Review-Pieter Verstraete PDFPieter Verstraete, Dr100% (1)

- November 2016 Editorial Full - FINALDocument201 pagesNovember 2016 Editorial Full - FINALRohitKumarNo ratings yet

- DescargaDocument5 pagesDescargaasoinco olarteNo ratings yet

- CCX-17 / CCX-19 Rugged 1U Military Grade Rackmount LCD Keyboard DrawerDocument4 pagesCCX-17 / CCX-19 Rugged 1U Military Grade Rackmount LCD Keyboard DrawerDavid LippincottNo ratings yet

- Qwo-Li Driskill, PHD: Academic AppointmentsDocument20 pagesQwo-Li Driskill, PHD: Academic Appointmentsvladimirkulf2142No ratings yet

- Dunsby, Schoenberg's Op. 22 No. 4 Premonition (JASI 1-3, 1977)Document7 pagesDunsby, Schoenberg's Op. 22 No. 4 Premonition (JASI 1-3, 1977)Victoria ChangNo ratings yet

- Cat Acc PassatDocument36 pagesCat Acc PassatOvidiuNo ratings yet

- Studies of Flatness of Lifi Channel For Ieee 802.11BbDocument6 pagesStudies of Flatness of Lifi Channel For Ieee 802.11BbedgarNo ratings yet

- Preludio BWV 998Document4 pagesPreludio BWV 998Santiago DunneNo ratings yet

- Kit Focal 165 v30 User ManualDocument16 pagesKit Focal 165 v30 User ManualFelipe BonoraNo ratings yet

- WAP HS LectureDocument33 pagesWAP HS LectureEdison C. TiczonNo ratings yet

- Cath Penales Power PointDocument12 pagesCath Penales Power PointjhokenNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 - Web, Nonstore-Based, and Other Forms of Nontraditional RetailingDocument7 pagesChapter 6 - Web, Nonstore-Based, and Other Forms of Nontraditional RetailingAbdul BasitNo ratings yet

- Time Change SongDocument1 pageTime Change SongChristian CosasNo ratings yet

- Trư NG THPT Đ I Cư NGDocument5 pagesTrư NG THPT Đ I Cư NGQuynh TrangNo ratings yet

- Everything We Have Been Afraid To Ask About Amfiteater PDFDocument10 pagesEverything We Have Been Afraid To Ask About Amfiteater PDFtomqzNo ratings yet

- PLAGIARISMDocument18 pagesPLAGIARISMjg.mariane102No ratings yet

- Sweden Top 20: List Your Movie, TV & Celebrity PicksDocument10 pagesSweden Top 20: List Your Movie, TV & Celebrity PicksSilviuSerbanNo ratings yet