Professional Documents

Culture Documents

International Journal of Anesthetics and Anesthesiology Ijaa 7 112

Uploaded by

mikoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

International Journal of Anesthetics and Anesthesiology Ijaa 7 112

Uploaded by

mikoCopyright:

Available Formats

ISSN: 2377-4630

Altshuler and Ibekwe. Int J Anesthetic Anesthesiol 2020, 7:112

DOI: 10.23937/2377-4630/1410112

Volume 7 | Issue 4

International Journal of Open Access

Anesthetics and Anesthesiology

Case Report

Multimodal Technique to Maximize Perioperative Pain

Control and Minimize Opioid Use in a Patient Undergoing

Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy: A Case Report

Jaclyn R. Altshuler, MD* and Stephanie Ibekwe, MD

Check for

updates

Department of Anesthesiology, Baylor College of Medicine, USA

*Corresponding author: Jaclyn R Altshuler, MD, Department of Anesthesiology, Baylor College of Medicine, 1 Baylor

Plaza, Houston, TX 77030, USA, Tel: 713-798-7356

Abstract tion, sleep disturbances, and respiratory depression are

among many of opioid-related adverse effects, and may

Perioperative opioid sparing techniques are paramount

contribute to increased in-hospital morbidity and costs

given the current opioid epidemic. A 54-year-old woman

presented with medical history of acute cholecystitis for la- [2]. As such, opioid-sparing modalities have been em-

paroscopic cholecystectomy. Our goal was adequate pain ployed to improve pain control and recovery, and mini-

control while limiting opioid administration and opioid-rela- mize opioid related adverse effects.

ted adverse effects. Pain was managed with preoperative

acetaminophen, tramadol, and gabapentin, and intraopera- In a systematic review of randomized controlled

tively with lidocaine, ketamine, and esmolol. Post-operative trials, findings showed perioperative intravenous lido-

Visual Analog Score (VAS) was 0/10 immediately following

caine infusion resulted in significant reductions in po-

surgery. Although her pain score peaked to 10/10 30 minu-

tes post-operatively and she received 0.4 milligrams intra- stoperative pain intensity and opioid consumption com-

venous hydromorphone, her VAS then declined to 0 and pared to controls for open and laparoscopic abdominal

remained so throughout her hospitalization without additio- surgery [3]. A randomized controlled trial examining

nal analgesics.

perioperative intravenous lidocaine infusion during la-

Abbreviations paroscopic cholecystectomy found that those who re-

VAS: Visual Analog Score; MAC: Minimum Alveolar Con- ceived the lidocaine infusion had significant reduction

centration; PACU: Post-Anesthesia Care Unit; NMDA: in time for bowel recovery, and less cytokine release,

N-methyl-D-aspartate; n: Number of subjects; TAP: Tran- compared to controls [4].

sversus Abdominis Plane; LA: Local Anesthetic; LAI: Local

Anesthetic Infiltration Studies demonstrating the effect of lidocaine in

conjunction with other opioid sparing modalities such

Introduction as esmolol and ketamine are needed. We present a case

in which we achieved an opioid free anesthetic for lapa-

Perioperative opioid sparing techniques are requi-

roscopic cholecystectomy utilizing a combination of li-

site given the current opioid epidemic. Post-operative

docaine infusion, esmolol, ketamine, and perioperative

pain control remains a significant issue for laparoscopic

multimodal medications. Our goal was adequate pain

cholecystectomy. Inadequate pain control is frequent-

control while limiting opioid-related adverse effects.

ly the main complaint postoperatively, the reason for

prolonged hospital stay, prolonged recovery, and po- This manuscript adheres to the applicable EQUATOR

tentially the development of chronic pain [1]. Posto- guideline. HIPAA authorization has been obtained from

perative nausea and vomiting, sedation, urinary reten- this patient.

Citation: Altshuler JR, Ibekwe S (2020) Multimodal Technique to Maximize Perioperative Pain Control

and Minimize Opioid Use in a Patient Undergoing Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy: A Case Report. Int J

Anesthetic Anesthesiol 7:112. doi.org/10.23937/2377-4630/1410112

Accepted: October 31, 2020: Published: November 02, 2020

Copyright: © 2020 Altshuler JR, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the

Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction

in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Altshuler and Ibekwe. Int J Anesthetic Anesthesiol 2020, 7:112 • Page 1 of 4 •

DOI: 10.23937/2377-4630/1410112 ISSN: 2377-4630

Case Description In contrast, ketamine exerts its effects by antagoni-

zing the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor at the

A 54-year-old woman with no past medical history

level of the spinal cord to modulate nociceptive pro-

presented with right-upper-quadrant and epi-gastric

cessing and hyperexcitability [1]. NMDA receptors have

pain, nausea and vomiting. Evaluation showed 1.2 cm

been shown to play a role in inflammatory pain, secon-

dilation of the common bile duct on ultrasound, and in-

dary hyperalgesia, neuropathic pain, and chronic pain

creasing liver profile studies. After a thorough work up

as a result of sensitization via spinal neural plasticity

by the general surgery and gastrointestinal services, the

occurring secondary to persistent pain [5]. In the setting

patient underwent an elective laparoscopic cholecystec-

of surgery, noxious stimuli activate C-fiber nociceptors,

tomy for gallstone pancreatitis and acute cholecystitis.

which triggers glutamate release and NMDA receptor

Prior to the procedure, the patient reported a Visual activation [6]. Ketamine blocks this pathway thereby

Analog Score (VAS) of 0/10 pain. She had not taken any decreasing neuroexcitation, with the added benefit of

pain medication within 2 days of surgery. The risks and reducing the development of chronic pain by inhibiting

benefits of general anesthesia were discussed with the neuronal sensitization. At low doses such as that used

patient, and she agreed to proceed with surgery under for our patient (0.5 milligram/kilogram), ketamine has

general anesthesia. Multimodal PO medications inclu- been shown to reduce postoperative pain with minimal

ding 1 gram Tylenol, 50 milligrams tramadol, and 100 to no adverse effects [6].

milligrams gabapentin were given preoperatively.

Lidocaine has a multifactorial approach to pain mo-

Intraoperative Management dulation. Due to a low blood concentration achieved

with a dose of 1-2 milligrams/hour, it is unlikely related

Prior to induction of anesthesia, the patient received

to sodium channel blockade (as it could not block all so-

2 milligrams of midazolam. Anesthesia was induced with

dium channels at such a low dose) but rather provides

60 milligrams lidocaine, 30 milligrams ketamine, 100

analgesia through mediation of inflammatory signaling

milligrams propofol, 60 milligrams succinylcholine, and

pathways. The proposed mechanism involves local ane-

40 milligrams esmolol. After intubation the patient was

sthetic blockade of polymorphonuclear granulocytes

maintained with 1.0 Minimum Alveolar Concentration

(which do not express sodium channels) from producing

(MAC) Sevoflurane. A lidocaine infusion was started im-

reactive oxygen species and cytokines that leads to in-

mediately after induction and run at 2 milligrams/minu-

flammation and subsequent pain [7].

te until extubation (total 80 minutes, ~158 milligrams).

Prior to incision, the surgeon injected each of the 4 port Esmolol is a short acting β-1 receptor antagonist used

sites with 0.25% bupivacaine and no drains were placed perioperatively to manage tachycardia and hyperten-

for postoperative drainage. The patient received10 mil- sion. It is posited that esmolol may play a role in central

ligrams ketamine and 20 milligrams Esmolol each hour analgesia, via either stimulation of G-protein coupled

and 30 milligrams of ketorolac at the end of the case. receptors controlling the release of neurotransmitters,

She remained hemodynamically stable throughout the or by blocking hippocampal activation of N-methyl-D-a-

procedure and emergence. She was extubated and ta- spartate subtype glutamate receptors, via adrenergic

ken to the Post-Anesthesia Care Unit (PACU) for moni- pathways, which may attenuate the perception of pain

toring. [8,9]. Esmolol has shown opioid sparing benefit in doses

ranging from 1.0 microgram/kilogram up to 2 milligram/

Post-Operative Pain kilogram bolus, followed by infusion ranging from 5-500

The patient reported a VAS of 0/10 on admission micrograms/kilogram/minute. In our patient, esmolol

to the PACU. At 30 minutes postop, her VAS peaked at was given as a bolus of 40 mg (equivalent to roughly

10/10. The patient received a total of 0.4 milligrams hy- 0.7 milligram/kilogram) at induction, then 20 milligram

dromorphone in the first 45 minutes after her surgery. each hour thereafter throughout the surgery, which to-

VAS were 6/10, 4/10 and 0/10 by 45 minutes, 1 hour taled to an additional 40 milligram.

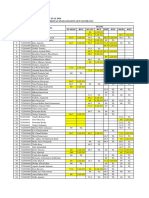

and 2 hours respectively. VAS thereafter remained 0/10 To evaluate the efficacy of our pain management

until discharge the following day. The patient did not re- regiment, we compared our patient’s post-operative

quire any additional opioid or multimodal pain medica- pain scores to those published by other studies investi-

tions during her hospitalization. gating multimodal pain regimens in patients specifically

Discussion undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomies (Figure 1).

We also compared opioid consumption over 24 hours

In an attempt to limit opioid use, multiple medica- post-op in our patient and the mean of those receiving

tions with different effects on pain pathways were em- the other pain regimens (Figure 2).

ployed. Opioids primarily act through the inhibitory de-

scending pathway to decrease neuronal excitability and As listed in Figure 1, the pain management regimens

nociceptive neurotransmitter release in the central and investigated in other studies included various combi-

peripheral nervous systems. nations of ibuprofen, acetaminophen, and meperidine;

Altshuler and Ibekwe. Int J Anesthetic Anesthesiol 2020, 7:112 • Page 2 of 4 •

DOI: 10.23937/2377-4630/1410112 ISSN: 2377-4630

12.0

10.0

10.0

8.0

VAS Pain Score

6.0

4.0

4.0

2.0

0.0 0.0 0.0

0.0

Immediate 30 Minutes 60 Minutes 120 Minutes 24 hours

Post-Op Time Interval

Our Patient 800 mg ibuprofen + meperidine 0.5 mg/kg (n = 30) 1000 mg acetaminophen + meperidine 0.5 mg/kg (n = 30)

No multimodal + meperidine 0.58 mg/kg (n = 30) TAP block + LA infiltration (n = 60) LAI alone (n = 60)

Preemtive ketamine 0.5 mg/kg (n = 20)

Figure 1: Postoperative VAS in patients receiving different analgesic regimens periopertively. Bar graph reflects mean VAS

for each pain regiment per study.

n = number of subjects.

Table 1: Postoperative VAS stratified by time interval and analgesic regimen. Mean pain scores were higher compared to those

reported by the study subject at the two hour and twenty-four-hour timepoints. A higher score was reported in the first hour after

surgery.

Early Postoperative Pain Measurements

Immediate 30 minutes 60 minutes 120 minutes 24 hours

Our Patient 0.0 10.0 4.0 0.0 0.0

Other Regimens 2.9 2.7 3.8 3.5 1.5

Difference 2.9 -7.4 -0.2 3.5 1.5

VAS = Visual analog scale.

another compared local anesthetic infiltration (LAI) and the lowest. Our patient had a 4-fold lower opioid consu-

transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block; and a third mption compared to the LAI alone.

looked at how the addition of ketamine affected VAS

Despite a low overall opioid consumption, and ab-

[6,10,11]. Taking a look at our patient’s post-operative

sence of adverse opioid related side effects, our patient

pain scores (depicted in dark blue) on this first graph,

did still require some opioid in the postoperative pe-

we can see that immediately postop, our patient repor-

riod. While the use of lidocaine infusions, esmolol, and

ted no pain. Her pain score did peak to 10/10 at 30 mi-

ketamine may not completely prevent the use of opio-

nutes, but then declined thereafter, remaining at 0 at 2

ids, acceptable pain control postoperatively can still be

hours and through discharge the following day.

achieved and sustained without any of the opioid-rela-

Table 1 illustrates post-op scores of our patient com- ted adverse effects. Therefore, it is reasonable to fur-

pared to the mean of the other pain regimens. The other ther study the use of lidocaine, esmolol, and ketamine

studies did not have the same intervals as our patient to as part of a multimodal, opioid sparing analgesic regi-

compare pain scores at every time interval. However we men in the perioperative period for patients undergoing

can see that at 60 minutes, our scores were not much laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

different (3.8 and 4.0). And, our patient’s pain scores at

the immediate postop period, and from 2 hours post-op

Financial Disclosures

and onward remained below the mean score expressed None.

by patients receiving other pain regimens.

Conflicts of Interest

With regard to postoperative opioid use (Figure 2),

None.

the specific opioid medications administered varied per

study. In order to compare opioid use postoperatively, Authors and Contribution

as depicted in Figure 2, all opioids were converted to

Jaclyn Altshuler helped contribute to the content

intravenous morphine equivalents [12,13]. The average

and design of this manuscript.

opioid consumption for the other studies is depicted by

the dotted line. Notably, Meperidine alone had the hi- Stephanie Ibekwe helped contribute to the content

ghest 24-hour opioid consumption, and LAI alone had and design of this manuscript.

Altshuler and Ibekwe. Int J Anesthetic Anesthesiol 2020, 7:112 • Page 3 of 4 •

DOI: 10.23937/2377-4630/1410112 ISSN: 2377-4630

60.0

56.6

50.0

IV Morphine Equivalent (mg)

40.0

34.2 Average Opioid Consump2on:

27.4mg IV Morphine

30.0 Equivalent

21.5

20.0

20.0 17.0

15.0

10.0

2.0

-

Our patient No multimodal + 1000 mg acetaminophen + 800 mg ibuprofen + TAP block + rectus sheath TAP block + LA LAI alone (n=60)

meperidine 0.5 mg/kg meperidine 0.5 mg/kg meperidine 0.5 mg/kg block (n=60) infiltration (n=60)

(n=30) (n=30) (n=30)

Figure 2: 24-hour opioid consumption. Bar graph reflects mean opioid consumption in 24 hours for each pain regimen per

study. Opioids used per study converted to intravenous morphine equivalent.

n = number of subjects.

References 7. Dunn LK, Durieux ME (2017) Perioperative use of intrave-

nous lidocaine. Anesthesiology 126: 729-737.

1. Bisgaard T (2006) Analgesic treatment after laparoscopic

cholecystectomy: A critical assessment of the evidence. 8. Hagelüken A, Grünbaum L, Nürnberg B, Harhammer R,

Anesthesiology 104: 835-846. Schunack W, et al. (1994) Lipophilic beta-adrenoceptor

antagonists and local anesthetics are effective direct acti-

2. Kehlet H (2005) Postoperative opioid sparing to hasten re- vators of G-proteins. Biochem Pharmacol 47: 1789-1795.

covery: What are the issues?. Anesthesiology 102: 1083-

1085. 9. Sarvey JM, Burgard EC, Decker G (1989) Long-term po-

tentiation: Studies in the hippocampal slide. J Neurosci

3. McCarthy GC, Megally SA, Habib AS (2010) Impact of in- Methods 28: 109-124.

travenous lidocaine infusion on postoperative analgesia

and recovery from surgery: A systematic review of rando- 10. Ekinci M, Ciftci B, Celik EC, Kose EA, Karakaya MA, et

mized controlled trials. Drugs 70: 1149-1163. al. (2020) A randominzed, placebo-controlled, double-blind

study that evaluates efficacy of intravenous ibuprofen and

4. Song X, Sun Y, Zhang X, Li T, Yang B (2017) Effect of pe- acetaminophen for postoperative pain treatment following

rioperative intravenous lidocaine infusion on postoperative laparoscopic cholecystectomy surgery. J Gastrointest Surg

recovery following laparoscopic Cholecystectomy-A rando- 24: 780-785.

mized controlled trial. International Journal of Surgery 45:

8-13. 11. Wu L, Wu L, Sun H, Dong C, Yu J (2019) Effect of ultra-

sound-guided peripheral nerve blocks of the abdominal wall

5. Voscopoulos C, Lema M (2010) When does acute pain be- on pain relief after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Pain

come chronic? Br J Anaesth 105: i69-i85. Res 12: 1433-1439.

6. Singh H, Kundra S, Singh RM, Grewal A, Kaul TK, et al. 12. (2009) Opiate equianalgesic dosing chart. Published.

(2013) Preemptive analgesia with ketamine for laparosco-

pic cholecystectomy. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol 29: 13. http://www3.us.elsevierhealth.com/pain/pdf/Chart1b.pdf

478-484.

Altshuler and Ibekwe. Int J Anesthetic Anesthesiol 2020, 7:112 • Page 4 of 4 •

You might also like

- EVALUATION OF THE INFLUENCE OF TWO DIFFERENT SYSTEMS OF ANALGESIA AND THE NASOGASTRIC TUBE ON THE INCIDENCE OF POSTOPERATIVE NAUSEA AND VOMITING IN CARDIAC SURGERYFrom EverandEVALUATION OF THE INFLUENCE OF TWO DIFFERENT SYSTEMS OF ANALGESIA AND THE NASOGASTRIC TUBE ON THE INCIDENCE OF POSTOPERATIVE NAUSEA AND VOMITING IN CARDIAC SURGERYNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Anesthetics and Anesthesiology Ijaa 7 118Document7 pagesInternational Journal of Anesthetics and Anesthesiology Ijaa 7 118Ferdy RahadiyanNo ratings yet

- KetamineDocument7 pagesKetamineAshiyan IrfanNo ratings yet

- Journal of Clinical AnesthesiaDocument2 pagesJournal of Clinical AnesthesiatsalasaNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Clonidine and Fentanyl As An Adjuvant To Bupivacaine in Unilateral Spinal AnaesthesiaDocument11 pagesComparison of Clonidine and Fentanyl As An Adjuvant To Bupivacaine in Unilateral Spinal AnaesthesiaYadin SabudiNo ratings yet

- Initial Experience Using Incisional Anesthetic Catheter in Abdominal Wall Ambulatory SurgeryDocument6 pagesInitial Experience Using Incisional Anesthetic Catheter in Abdominal Wall Ambulatory SurgeryilhamNo ratings yet

- Efficacy Lidocaine Endoscopic Submucosal DissectionDocument7 pagesEfficacy Lidocaine Endoscopic Submucosal DissectionAnonymous lSWQIQNo ratings yet

- Effect Observation of Electro Acupunctute AnesthesiaDocument7 pagesEffect Observation of Electro Acupunctute Anesthesiaadink mochammadNo ratings yet

- Amalia 163216 - Journal ReadingDocument26 pagesAmalia 163216 - Journal ReadingGhifari FarandiNo ratings yet

- 11 LdpopDocument5 pages11 LdpopBaru Chandrasekhar RaoNo ratings yet

- PracticeJournal1 PutriMaharaniAndes 19-0010Document8 pagesPracticeJournal1 PutriMaharaniAndes 19-0010putri maharani andesNo ratings yet

- Randomized Controlled Trial of The Effect of Depth of Anaesthesia On Postoperative PainDocument6 pagesRandomized Controlled Trial of The Effect of Depth of Anaesthesia On Postoperative PainIntan PurnamasariNo ratings yet

- 2264-Article Text-5024-4-10-20151024Document6 pages2264-Article Text-5024-4-10-20151024shivamNo ratings yet

- 3 PBDocument7 pages3 PBDinda ArmeliaNo ratings yet

- Research ArticleDocument10 pagesResearch ArticlethiaNo ratings yet

- Profopol Vs KTMDocument7 pagesProfopol Vs KTMAuliaRusdiAllmuttaqienNo ratings yet

- Acup Utk TonsiltektomiDocument7 pagesAcup Utk Tonsiltektominewanda1112No ratings yet

- Right Open Nephrectomy Under Combined Spinal and Peridural Operative Anesthesia and Analgesia (CSE) : A New Anesthetic Approach in Abdominal SurgeryDocument2 pagesRight Open Nephrectomy Under Combined Spinal and Peridural Operative Anesthesia and Analgesia (CSE) : A New Anesthetic Approach in Abdominal SurgeryPablo Segales BautistaNo ratings yet

- Effects of Intraoperative Epidural Anesthesia During Hepatectomy On Intraoperative and Post-Operative Patient OutcomesDocument8 pagesEffects of Intraoperative Epidural Anesthesia During Hepatectomy On Intraoperative and Post-Operative Patient OutcomesAfniNo ratings yet

- Dolor Postop, Ligamentos Cruzados, AmbulatorioDocument7 pagesDolor Postop, Ligamentos Cruzados, AmbulatorioChurrunchaNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Analgesic Effects of Intravenous Nalbuphine and Pentazocine in Patients Posted For Short-Duration Surgeries A Prospective Randomized Double-Blinded StudyDocument4 pagesComparison of Analgesic Effects of Intravenous Nalbuphine and Pentazocine in Patients Posted For Short-Duration Surgeries A Prospective Randomized Double-Blinded StudyMuhammad AtifNo ratings yet

- Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting in OpioidFree Anesthesia Versus Opioid Based Anesthesia in Laparoscopic CholecystectomyDocument8 pagesPostoperative Nausea and Vomiting in OpioidFree Anesthesia Versus Opioid Based Anesthesia in Laparoscopic Cholecystectomypepe4dwinNo ratings yet

- Calvillo 2009Document2 pagesCalvillo 2009Anto RadošNo ratings yet

- Gusti Muhammad Edy Muttaqin I4A012067 Pembimbing: Dr. Andri L. Tobing, SP - AnDocument25 pagesGusti Muhammad Edy Muttaqin I4A012067 Pembimbing: Dr. Andri L. Tobing, SP - AnBellato MauNo ratings yet

- Perioperative Anesthetic Management of Intestinal Pseudo-Obstruction As A Complication of PheochromocytomaDocument4 pagesPerioperative Anesthetic Management of Intestinal Pseudo-Obstruction As A Complication of Pheochromocytomaceneh5695weizixu.com xNo ratings yet

- Analgesic Effects and Adverse Reactions of LidocaiDocument6 pagesAnalgesic Effects and Adverse Reactions of Lidocaibrendastevany23No ratings yet

- Efficacy of Dexamethasone For Reducing Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting and Analgesic Requirements After ThyroidectomyDocument4 pagesEfficacy of Dexamethasone For Reducing Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting and Analgesic Requirements After ThyroidectomyDr shehwarNo ratings yet

- Aroma 1Document8 pagesAroma 1bazediNo ratings yet

- DwefgnmjDocument8 pagesDwefgnmjfabian arassiNo ratings yet

- JAnaesthClinPharmacol37163-254754 000414Document4 pagesJAnaesthClinPharmacol37163-254754 000414Ferdy RahadiyanNo ratings yet

- TENS em LipoDocument8 pagesTENS em LipoKamylla Caroline SantosNo ratings yet

- 7 Early Clinical Experience Using High Intensity Focused Ultrasound For Palliation of Inoperable Pancreatic CancerDocument7 pages7 Early Clinical Experience Using High Intensity Focused Ultrasound For Palliation of Inoperable Pancreatic CancerEvelynLisettVargasNo ratings yet

- Intrapleural CatheterDocument2 pagesIntrapleural CatheterDr.Sandeep Kumar KarNo ratings yet

- JPM 13 00586 v2Document14 pagesJPM 13 00586 v2Çağdaş BaytarNo ratings yet

- Is Granisetron-Dexamethasone Combination Better ThanDocument8 pagesIs Granisetron-Dexamethasone Combination Better ThanGustomo PanantroNo ratings yet

- Anesthesia & ClinicalDocument4 pagesAnesthesia & Clinicalreinhard fourayNo ratings yet

- Anes 10 3 9Document7 pagesAnes 10 3 9ema moralesNo ratings yet

- Small-Dose Ketamine Infusion Improves Postoperative Analgesia and Rehabilitation After Total Knee ArthroplastyDocument6 pagesSmall-Dose Ketamine Infusion Improves Postoperative Analgesia and Rehabilitation After Total Knee ArthroplastyArturo AlcantaraNo ratings yet

- DR Surekha S Chavan, DR Stephan Jebaraj & DR Priya ChavreDocument10 pagesDR Surekha S Chavan, DR Stephan Jebaraj & DR Priya ChavreTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- 9829 CE (Ra) F (SH) PF1 (SNAK) PFA (P)Document4 pages9829 CE (Ra) F (SH) PF1 (SNAK) PFA (P)razaqhussain00No ratings yet

- Microdosis de KetaminaDocument8 pagesMicrodosis de Ketaminasilvia XNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2468824X17300517 MainDocument5 pages1 s2.0 S2468824X17300517 MainFirah Triple'sNo ratings yet

- JAnaesthClinPharmacol293394-8554992 234549 PDFDocument3 pagesJAnaesthClinPharmacol293394-8554992 234549 PDFAle ZuveNo ratings yet

- K Etorolac Tormethamine PDFDocument19 pagesK Etorolac Tormethamine PDFMuhammad Khairun NNo ratings yet

- Management of Postoperative Pain: Anaesthesia SupplementDocument4 pagesManagement of Postoperative Pain: Anaesthesia SupplementBani ZakiyahNo ratings yet

- Pain Management & MedicineDocument6 pagesPain Management & MedicinelinggaNo ratings yet

- Lee 2017Document6 pagesLee 2017Heine MüllerNo ratings yet

- Post CraniotomyDocument10 pagesPost CraniotomyTika HandayaniNo ratings yet

- 709 1357 1 PBDocument13 pages709 1357 1 PBTri NoviantyNo ratings yet

- 3. Bài Báo Tiếng Anh Khác Tên Tác GiảDocument5 pages3. Bài Báo Tiếng Anh Khác Tên Tác GiảnamanesthesiaNo ratings yet

- 10.1007@s00405 020 05801 6Document6 pages10.1007@s00405 020 05801 6Leonardo GuimelNo ratings yet

- Opioid-Free Anaesthesia - Atow-461-00 - BDocument6 pagesOpioid-Free Anaesthesia - Atow-461-00 - BEugenio Martinez HurtadoNo ratings yet

- Rba 70 6 682Document4 pagesRba 70 6 682Marco Antonio Rosales GuerreroNo ratings yet

- DOR - FENOL - Chemical Ablation of Genicular Nerve With Phenol For Pain Relief in Patients With Knee Osteoarthritis A Prospective Study - CompressedDocument7 pagesDOR - FENOL - Chemical Ablation of Genicular Nerve With Phenol For Pain Relief in Patients With Knee Osteoarthritis A Prospective Study - CompressedGustavo FredericoNo ratings yet

- Section: Surgery: Category: B - Clinical SciencesDocument6 pagesSection: Surgery: Category: B - Clinical SciencesAbu TauhidNo ratings yet

- Erdem 2018Document9 pagesErdem 2018SFS GAMEX546No ratings yet

- KaratepeDocument5 pagesKaratepeJennifer GNo ratings yet

- Effect of Ketofol On Pain and Complication After Caesarean Delivery Under Spinal Anaesthesia: A Randomized Double-Blind Clinical TrialDocument4 pagesEffect of Ketofol On Pain and Complication After Caesarean Delivery Under Spinal Anaesthesia: A Randomized Double-Blind Clinical TrialHaryoko AnandaputraNo ratings yet

- PIIS109471592400031XDocument9 pagesPIIS109471592400031XperruchoudNo ratings yet

- SMW 10163 PDFDocument9 pagesSMW 10163 PDFAngela PagliusoNo ratings yet

- Hasil CBT Minor Periode Juli 2020Document3 pagesHasil CBT Minor Periode Juli 2020mikoNo ratings yet

- Why Socioeconomic Status Affects The Health of ChildrenDocument4 pagesWhy Socioeconomic Status Affects The Health of ChildrenmikoNo ratings yet

- The Open Anesthesia JournalDocument11 pagesThe Open Anesthesia JournalmikoNo ratings yet

- Delayed Antibiotic Prescription For Children With Respiratory Infections: A Randomized TrialDocument13 pagesDelayed Antibiotic Prescription For Children With Respiratory Infections: A Randomized TrialmikoNo ratings yet

- Factors Associated With Severe Sars-Cov-2 Infection: BackgroundDocument14 pagesFactors Associated With Severe Sars-Cov-2 Infection: BackgroundmikoNo ratings yet

- The Growth and Development Status of Homeless Children Entering Shelters in BostonDocument4 pagesThe Growth and Development Status of Homeless Children Entering Shelters in BostonmikoNo ratings yet

- Toatj 14 80 PDFDocument10 pagesToatj 14 80 PDFmikoNo ratings yet

- Drug Induced Anaphylaxis During General Anesthesia in 14 Tertiary Hospitals in Japan: A Retrospective, Multicenter, Observational StudyDocument7 pagesDrug Induced Anaphylaxis During General Anesthesia in 14 Tertiary Hospitals in Japan: A Retrospective, Multicenter, Observational StudymikoNo ratings yet

- The Open Anesthesia JournalDocument11 pagesThe Open Anesthesia JournalmikoNo ratings yet

- The Open Anesthesia JournalDocument7 pagesThe Open Anesthesia JournalmikoNo ratings yet

- Anesthetics and AnesthesiologyDocument8 pagesAnesthetics and AnesthesiologymikoNo ratings yet

- Anaesthetic Approach For Patient With Hereditary AngioedemaDocument3 pagesAnaesthetic Approach For Patient With Hereditary AngioedemamikoNo ratings yet

- PRM2017 1721460 PDFDocument6 pagesPRM2017 1721460 PDFmikoNo ratings yet

- Pulmonary HypertensionDocument36 pagesPulmonary HypertensionDiana_anca6100% (2)

- MeclizineDocument2 pagesMeclizineGwyn Rosales100% (1)

- Dwnload Full Introduction To Clinical Pharmacology 9th Edition Visovsky Test Bank PDFDocument35 pagesDwnload Full Introduction To Clinical Pharmacology 9th Edition Visovsky Test Bank PDFlisadavispaezjwkcbg100% (9)

- Antifungal Potential of Aqueous Extract of Mondia Whitei Root Bark Phytochemical Analysis and Inhibition StudiesDocument7 pagesAntifungal Potential of Aqueous Extract of Mondia Whitei Root Bark Phytochemical Analysis and Inhibition StudiesKIU PUBLICATION AND EXTENSIONNo ratings yet

- Bokal Farmasi 9thDocument13 pagesBokal Farmasi 9thIndah KomalasariNo ratings yet

- ICABST 2022 Conf - Program and Abstract BookDocument16 pagesICABST 2022 Conf - Program and Abstract BookDr.Vijayan Gurumurthy IyerNo ratings yet

- Hypertension in Pregnancy Pih BjaDocument5 pagesHypertension in Pregnancy Pih BjaUpasana SinghNo ratings yet

- Medical Management (Vehicular Accident) Revised Final For PrintingDocument4 pagesMedical Management (Vehicular Accident) Revised Final For PrintingJemalyn M. SaludarNo ratings yet

- Bawalan, Hewlett Pearl L. February 11, 2021 Module 4: AsthmaDocument5 pagesBawalan, Hewlett Pearl L. February 11, 2021 Module 4: AsthmaHewlett Pearl BawalanNo ratings yet

- Index: Sr. No. Topic NoDocument53 pagesIndex: Sr. No. Topic NoChetana JadhavNo ratings yet

- Dha SCFHS Pharmacy Exam 1Document52 pagesDha SCFHS Pharmacy Exam 1SEIYADU IBRAHIM KNo ratings yet

- Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy XXX (2017) 1 E2Document2 pagesResearch in Social and Administrative Pharmacy XXX (2017) 1 E2bimuNo ratings yet

- Hema I Chapter 4 - AnticoagDocument15 pagesHema I Chapter 4 - Anticoagmulugeta fentaNo ratings yet

- 4 RJPT 14-2-2021 Akshata ResearchDocument5 pages4 RJPT 14-2-2021 Akshata ResearchNutan Desai RaoNo ratings yet

- February 8, 2021: BioNTech's NONCLINICAL OVERVIEW Submission To FDA For ComirnatyDocument36 pagesFebruary 8, 2021: BioNTech's NONCLINICAL OVERVIEW Submission To FDA For ComirnatyBrian O'SheaNo ratings yet

- Evidence B (I) Ased Medicine - Selective Reporting From Studies Sponsored by Pharmaceutical Industry: Review of Studies in New Drug ApplicationsDocument5 pagesEvidence B (I) Ased Medicine - Selective Reporting From Studies Sponsored by Pharmaceutical Industry: Review of Studies in New Drug ApplicationsAndre LanzerNo ratings yet

- Daftar Dosis MaksimumDocument7 pagesDaftar Dosis MaksimumAldi AryantoNo ratings yet

- Sipoc and Process ImprovementDocument6 pagesSipoc and Process ImprovementUsman Shafi ArainNo ratings yet

- Chemotherapy Question 1Document6 pagesChemotherapy Question 1Vaishali PrasharNo ratings yet

- Neurotransmitters - 2016Document183 pagesNeurotransmitters - 2016AdminNo ratings yet

- Pharmacology - Git DrugsDocument123 pagesPharmacology - Git DrugsBenjamin Joel Breboneria75% (4)

- Bun PT Introducere - Removal of Cytostatic Drugs From Aquatic Environment A ReviewDocument18 pagesBun PT Introducere - Removal of Cytostatic Drugs From Aquatic Environment A ReviewsorinamotocNo ratings yet

- Pain 1585622753Document284 pagesPain 1585622753eva pravitasari nefertitiNo ratings yet

- Buy Tadarise Pro 40mg - AllDayGenericDocument9 pagesBuy Tadarise Pro 40mg - AllDayGenericrubarath100% (1)

- Antiarrhythmic DrugsDocument20 pagesAntiarrhythmic DrugsMd FcpsNo ratings yet

- Who Managemen AdrDocument28 pagesWho Managemen AdrkuronohanaNo ratings yet

- Aaha Selected Endocrinopathies of Dogs and Cats GuidelinesDocument23 pagesAaha Selected Endocrinopathies of Dogs and Cats GuidelinesErick Ramos100% (1)

- Camphor - Benefits, Precautions and Dosage - 1mgDocument12 pagesCamphor - Benefits, Precautions and Dosage - 1mgManish DandekarNo ratings yet

- Deep Vein Thrombosis & Its ProphylaxisDocument90 pagesDeep Vein Thrombosis & Its ProphylaxisPratik KumarNo ratings yet

- Dapsone Lyme DiseaseDocument53 pagesDapsone Lyme DiseasecemalsagmenNo ratings yet

- ADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDFrom EverandADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (5)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityFrom EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (39)

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsFrom EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsFrom EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsNo ratings yet

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (84)

- Love Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)From EverandLove Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)Rating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionFrom EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (404)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeFrom EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsFrom EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Twentysomething Treatment: A Revolutionary Remedy for an Uncertain AgeFrom EverandThe Twentysomething Treatment: A Revolutionary Remedy for an Uncertain AgeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- The Storyteller: Expanded: ...Because There's More to the StoryFrom EverandThe Storyteller: Expanded: ...Because There's More to the StoryRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (13)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.From EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (110)

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsFrom EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (170)

- Summary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (44)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaFrom EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (267)

- The Fun Habit: How the Pursuit of Joy and Wonder Can Change Your LifeFrom EverandThe Fun Habit: How the Pursuit of Joy and Wonder Can Change Your LifeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (19)

- Manipulation: The Ultimate Guide To Influence People with Persuasion, Mind Control and NLP With Highly Effective Manipulation TechniquesFrom EverandManipulation: The Ultimate Guide To Influence People with Persuasion, Mind Control and NLP With Highly Effective Manipulation TechniquesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1412)

- Critical Thinking: How to Effectively Reason, Understand Irrationality, and Make Better DecisionsFrom EverandCritical Thinking: How to Effectively Reason, Understand Irrationality, and Make Better DecisionsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (39)

- I Shouldn't Feel This Way: Name What’s Hard, Tame Your Guilt, and Transform Self-Sabotage into Brave ActionFrom EverandI Shouldn't Feel This Way: Name What’s Hard, Tame Your Guilt, and Transform Self-Sabotage into Brave ActionNo ratings yet

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossFrom EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- Summary: It Didn't Start with You: How Inherited Family Trauma Shapes Who We Are and How to End the Cycle By Mark Wolynn: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: It Didn't Start with You: How Inherited Family Trauma Shapes Who We Are and How to End the Cycle By Mark Wolynn: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- The Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeFrom EverandThe Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (256)