Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Trouble With Moral Rights

Uploaded by

rudra8pandey.8shivamOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Trouble With Moral Rights

Uploaded by

rudra8pandey.8shivamCopyright:

Available Formats

The Trouble with Moral Rights

Author(s): Patrick Masiyakurima

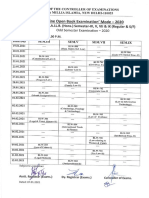

Source: The Modern Law Review , May, 2005, Vol. 68, No. 3 (May, 2005), pp. 411-434

Published by: Wiley on behalf of the Modern Law Review

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3699169

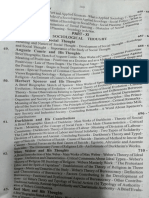

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/3699169?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Modern Law Review and Wiley are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to The Modern Law Review

This content downloaded from

14.139.214.181 on Mon, 21 Dec 2020 17:20:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Trouble with Moral Rights

Patrick Masiyakurima*

It is usually argued that moral rights are severely handicapped by their inconsistent entrenchment

in common law and civilian legal systems. This article argues that the main trouble with moral

rights protection is that the justifications for the existence of these rights are riddled with internal

inconsistencies generated by the vagaries of copyright exploitation. Harmonising moral rights

protection or using moral rights justifications cumulatively may not resolve the theoretical

inconsistencies. Copyright protection must therefore be seriously overhauled if moral rights are

to be widely perceived as vehicles for protecting authors' rights.

INTRODUCTION

The idea that Anglo-American copyright jurisdictions sacrific

the altar of economic expediency while their civilian counte

spiritual interests of authors is of antiquated pedigree.' True,

gence of copyright systems through international harmonisat

cies of modern copyright exploitation diminish the currenc

significantly2 but it still reverberates strongly in discussions on

tection.3 For instance, the patchwork nature of European Un

monisation is often partly ascribed to the difficulties surroun

the different moral rights provisions of various Member St

argues that philosophical divergences between copyright syst

ing, the trouble with moral rights chiefly emanates from acu

tencies in moral rights theories. The genesis of the inconsistencie

part to pervasive commodification of information and the r

* University of Aberdeen. I am grateful to David Vaver, Robin Evans-Jones

ver Masakure for their comments on earlier drafts of this article. All errors and o

statutes cited here were obtained from http://www.wipo.int/clea/en/ and all

checked on 4 February 2005.

1 Eg R. Sarraute,'Current Theory on the Moral Right of Authors and Ar

(1968) 16 AmericanJournal of Comparative Law 465. See also P. E. Geller,'Mus

Caught Between Marketplace and Authorship Norms? in B. Sherman and

Authors and Origins (Oxford: OUP, 1994) 159 and G. Davies,'The Converg

Authors' Rights: Reality or Chimera?' (1995) 26 IIC 964.

2 A. Frangon,'Authors' Rights Beyond Frontiers: A Comparison of Civil L

Conceptions' (1991) 149 Revue Internationale du Droit d'auteur (RIDA) 2, 16-2

3 Eg Theberge v Galerie dArt du Petit Champlain Inc (2002) SCC 34 (BinnieJ).

4 Eg L. Bently, Between A Rock and A Hard Place (London: Institute of Emplo

and G. Lea,'Moral Rights: Moving From Rhetoric To Reality In Pursui

nisation' in E. Barendt and A. Firth (eds), Yearbook of Copyright and Media L

OUP, 2002) 61, 78. See also M. Slokannel, A. Strowel and E. Derclaye,'Mor

text of the Exploitation of Works through Digital Technology' http://e

internalmarket/copyright/docs/studies/etd1999b53000e28_en.pdf for diffe

moral rights harmonisation.

? The Modem Law Review Limited 2005 (2005) 68(3) MLR 411-434

Published by Blackwell Publishing, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, US

This content downloaded from

14.139.214.181 on Mon, 21 Dec 2020 17:20:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Trouble with Moral Rights

among copyright stakeholders. It is hoped that the article will contribute to the

growing literature on the intractable conflicts among copyright stakeholders.

In terms of structure, the first part of the article provides a brief description of

moral rights while the remainder of the essay delineates the inherent weaknesses

of moral rights theories and proposes modest reforms in this area. The term

'author' is used throughout the article to describe the various'creators' of copyright

materials while the word 'work' is used as an umbrella term covering different

copyright subject matter. Despite the different theoretical underpinnings of civi-

lian and common law copyright systems, cases and materials from both legal tra-

ditions are used in the article to demonstrate the existence of common moral

rights principles. Additionally, given that different jurisdictions have different

moral rights provisions, a comparative analysis of moral rights yields a complete

theoretical picture.

Moral rights

Gradual international recognition of moral rights as instruments for preserving

authors' non-pecuniary interests does not mask the serious controversies sur-

rounding the boundaries of these rights. Dualists treat economic and moral rights

separately while monists integrate the two rights. Additionally, economics and

respect for the sanctity of contracts force common law jurisdictions to adopt the

lowest international common denominator of moral rights protection5 and to

harbour the doubtful view that other remedies adequately protect authors' rights.6

Despite these doctrinal and practical differences, some common moral rights can

be gleaned from different copyright laws.' The right of divulgation allows

authors to control initial publication of their work8 while the paternity right

requires identification of authors, protects pseudonymous authors and prevents

false attribution of authorship.9 The right of integrity is usually predicated on

minimising harm to authors' honour or reputation arising from unauthorised

interferences with copyright works after their creation.10 Authors may also rely

on their right of repentance to withdraw their views from circulation provided

they indemnify copyright owners for losses generated by the withdrawal and

resell the work to its previous owner on the old terms if they change their mind.1

Lastly, authors may access their alienated works for limited purposes including

copying the work or collecting evidence.12 A review of the relevant authorities

5 See Berne Convention (Paris Act 1971 828 UNTS 221) Art 6bis.

6 W R. Cornish,'Moral Rights under the 1988 Act' (1989) 11 EIPR 449.

7 Other pseudo 'moral rights' including the UK's right of privacy enshrined in the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act 1988 (CDPA), s 85 will not be discussed in this article.

8 Eg French IP Code Art L 121-2.

9 Z. Radojkovic,'The right to the paternity' (1965) 47 RIDA 168.

10 Eg Spanish Copyright Act Art 14(iv); cf French IP Code Art L121-1.

11 M. A. Roeder,'The Doctrine of Moral Right: A Study in the Law of Artists, Authors and Crea-

tors' (1940) 53 HarvLR 554.

12 S. Str6mholm, 'Droit Moral-The International and Comparative Scene from a Scandinavian

Viewpoint' (1983) 14 IIC 1, 26.

412 0 The Modem Law Review Limited 2005

This content downloaded from

14.139.214.181 on Mon, 21 Dec 2020 17:20:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Patrick Masiyakurima

yields four cardinal theories which underpin the existence of moral rights and it is

to these that we now turn.

Personality

The Romantic idea that copyright works are imbued with their authors' person-

ality"3 and must therefore be protected from unauthorised interferences is largely

derived from Hegel's theory of property ownership which predicates self-actuali-

sation on control of external objects.14 Personality rights inhere in individuals

irrespective of compliance with formalities"5 and they encompass various digni-

tary interests including honour and reputation, privacy, physical integrity and

freedom of belief and expression."6 In the moral rights context, the right of pater-

nity preserves the privacy of pseudonymous authors while the right of divulga-

tion prevents widespread dissemination of unpublished private information. In

most jurisdictions, the right of integrity is designed to minimise harm to authors'

honour or reputation arising from prejudicial changes to finished works."7 By

affording authors an opportunity to veto publishing decisions, the right of divul-

gation indirectly protects authors' reputational interests while the right of pater-

nity prevents injury to reputation arising from misattribution of authorship.18

The right of integrity prevents adulteration of authors' expressions while acts of

repentance may amount to an exercise of freedom of belief and expression. In rare

circumstances, misusing a work to propagate a message which is diametrically

opposed to its author's views may cause the author irreparable harm if it severely

disturbs her interaction with the public.

The relationship between moral rights and personality hinges on singular indi-

vidual creativity. However, three arguments cloud this lofty vision of authorship.

First, since copyright works usually evolve from existing ideas, a pedantic enfor-

cement of moral rights disproportionately benefits current authors, impedes

transformative uses of copyright works and potentially creates the spectre of irre-

concilable personality rights especially where adapters such as parodists rely on

extensive and unsympathetic uses of earlier texts for their own self-actualisation.

In Zorine and VAAP v Le Lucernaire, the court enforced the author's moral rights

despite accepting that adapters may infuse their own personality in transformed

works." In that case, despite acknowledging that an adaptation of a Russian play

into a French theatrical performance was highly original, the court held that the

political nature of the adaptation infringed the playwright's moral rights. Argu-

ably, the idea/expression dichotomy resolves some of these problems by sifting an

13 M.Woodmansee,'The Genius and the Copyright: Economic and Legal Conditions of the Emer-

gence of the Author' (1984) 17 Eighteenth-Century Studies 425.

14 M. J. Radin,'Property and Personhood' (1982) 34 StanLR 957 and J. Hughes,'The Philosophy of

Intellectual Property' (1988) 77 Georgetown LJ 287, 330.

15 H. Desbois,'The Moral Right' (1959) 19 RIDA 120 125.

16 R. Pound,'Interests of Personality' (1914) 28 HarvLR 343, 445.

17 Snow v The Eaton Centre (1982) 70 CPR (2d) 105 (Canada); Belgian Copyright Act Art 1(2).

18 Clark v Associated Newspapers Ltd [1998] 1 All ER 959.

19 [1987] ECC 54 and Danmarks National Bank v F [1995] ECC 147 cf Regine Deforges v Trust Company

Bank [1992] ECC 338 and SA Les Editions Salabert v Thierry Le Luron et al [1987] ECC 48.

? The Modem Law Review Limited 2005 413

This content downloaded from

14.139.214.181 on Mon, 21 Dec 2020 17:20:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Trouble with Moral Rights

author's individual contribution from other cultural ideas but its nucleus is a

recognition of the omnipresence of 'foreign' personalities in copyright works.20

Similarly, the safe harbours offered by fair dealing to transformative users are

diminished by judicial reticence to condone 'misappropriation' of copyright

works.21 Secondly, collaborative and derivative works such as films may not reflect

the individual personality of any one author.22 Thirdly, ascertaining the dominant

personality expressed in copyright works is fraught with difficulties. In Christo v

Agence Sygma,23 the court prohibited users from taking photographs of a draped

cultural landmark despite acknowledging the centrality of the landmark to the

author's work. Similar problems confront works based on human subjects. Focus-

ing on authors' moral rights exclusively raises proportionality issues while grant-

ing moral rights to subjects24 would negate the author-based foundations of

moral rights protection. All these conflicts emanate from commodification of

information which forces copyright owners to rely on various cosmetic facades

including individual authorship to reduce the harmful effects of competing

claims on copyright ownership and exploitation.

At first blush,'originality' arouses powerful visions of superlatively unique crea-

tions but this concept is usually confined to identifying the source of copyright

works rather than artistic merit.25 Even in civilian jurisdictions with their broad

ranging rules governing unfair competition and strong emphasis on protecting

outstanding works there is a wide chasm between theory and practice. For

instance, in Societe Microfor v Sal Le Monde,26 the Court of Cassation ruled that

newspaper titles were original copyright works. The genesis of this state of affairs

can be traced to judicial reticence to make controversial aesthetic decisions,27 pre-

serving a space for authors of differing abilities to express themselves, and to fears

that a strict test of originality would be a charter for misappropriation of banal

works.28 Although there are international moves to harmonise the standard of

originality upwards,29 protecting esoteric works including examination papers,

telephone directories, football coupons, case headnotes and banknotes30 detracts

from the singularity of individual self-expression normally associated with per-

20 Eg Designers Guild Ltd v Russell Williams (Textiles) Ltd [2001] 1 All ER 700 (HL).

21 Ashdown v Telegraph Group Ltd [2001] 3 WLR 1368 (CA) cf CCH Canadian Ltd v Law Society of Upper

Canada (2004) 236 DLR (4th) 395.

22 P. Kamina, Film Copyright in the European Union (Cambridge: CUP, 2002) 291-292.

23 [1987] ECC 228.

24 See CDPA 1988, s 85.

25 Eg Ladbroke v William Hill [1964] 1 All ER 465; Hay v Sloan (1957) 2 DLR (2d) 397.

26 [1988] ECC 297; also Babolat Maillot Witt SA v Pachot [1987] ECC 218, SA Harrap France and Harrap

Ltd v SA Masson Editeur and Ors [1991] ECC 322 and Sadrl Media and Others v Gerard Scher and Anor

[1998] ECC 101 cf Schweizerische Interpreten-Gesellschaft and Others v X and Z [1986] ECC 384 and Re

Copyright in Scientific Works [1989] ECC 232.

27 Eg Bleisten v Donaldson Lithographing Co 1888 US 239 (1903).

28 W R. Cornish, Intellectual Property Omnipresent, Distracting, Irrelevant? (Oxford: Clarendon Press,

2004) 45.

29 Eg Software Directive Art 1(3), Duration Directive Art 6 and Database Directive Art 3(1).

30 See University ofLondon Press Ltd v University Tutorial Press [1916] 2 Ch 601; Desktop Marketing Systems

Pty Ltd v Telstra Corp Ltd [2002] FCA 112 (Australia); Football League v Littlewoods [1959] Ch 637;

CCH Canadian Ltd v Law Society of Upper Canada (2004) 236 DLR (4th) 395 and Danmarks National

Bank v F [1995] ECC 147 respectively; though cf Feist Publications Inc v Rural Telephone Service Co 111

US 1282 (1989).

414 0 The Modem Law Review Limited 2005

This content downloaded from

14.139.214.181 on Mon, 21 Dec 2020 17:20:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Patrick Masiyakurima

sonality rights, privatises large quanta of information, proscribes transformative

uses of existing works and exposes the clever use of authors to disguise the injus-

tices of strengthening copyright owners' rights.31

Modern copyright exploitation often requires collaboration by teams of salar-

ied authors and necessitates deployment of vast financial resources. Given that

companies invest in and control the creative process, these artificial legal persons

are regarded by some jurisdictions as 'authors' of works created in the course of

employment.32 Ascribing authorship to companies with little discernible person-

ality interests is designed to minimise impediments to copyright exploitation but

it severs the symbiotic links between moral rights and individual creativity. Instead

of denying employees their authorship and moral rights, the best solution would

have been to limit spurious moral rights claims by requiring authors of collabora-

tive works to enforce their moral rights jointly.33 This approach would limit

moral rights litigation to cases involving genuine interferences with copyright

works. On the other hand, since employers are deeply ensconced in the creative

process, any resulting works are a manifestation of their instructions rather than

an embodiment of authors' personality and should therefore not benefit from

moral rights protection.34 However, some employed authors have a high degree

of latitude in complying with their employers' instructions to warrant the infu-

sion of their own personality in the final product.35 All these tensions highlight

the inevitable conclusion that apart from advancing their personality, authors also

create copyright works for economic reasons.36

Reproduction facilitates economic exploitation of copyright works,37 opti-

mises avenues for widespread dissemination of authors' personality and mitigates

the effects of destruction by providing exact replicas of artefacts. However, it is

difficult to approximate the personality interests contained in exact copies of a

work. Arguably, given that reproduction does not normally involve any addi-

tional creativity on the author's part, it is unnecessary to confer moral rights pro-

tection on exact copies of an original work. However, if the author intended to

disseminate his personality to a wide audience then exact copies of the work must

be protected if the author's expressions are to reach their target in pristine form.

These concerns notwithstanding, private interferences with exact and authorised

copies of a mass-produced work do not attract serious opprobrium because the

primary work remains a vessel of its author's personality. On the other hand, exact

and unauthorised copies implicate paternity rights if authorship of the work is

unacknowledged, disrupt the authenticity of the personality interests relayed to

the public if the work is altered and infringe the author's privacy if the original

work was unpublished. Serious problems are also generated by works that are

31 B. Kaplan, An Unhurried View of Copyright (New York: Columbia University Press, 1967) 6, 8.

32 See USA Copyright Act 1976, s 101.

33 Champard v SA des Editions Legislatives et Administratives [1981] ECC 521; Ponty v Chamberland [1992]

ECC 59.

34 H. Hansmann and M. Santilli, Authors' and Artists' Moral Rights: A Comparative Legal an

Economic Analysis' (1997) 26Journal of Legal Studies 95, 134; cfJ. Barta,'Copyright and Employee

Creativity' (1984) 121 RIDA 68.

35 Jean-Marc Vincent v SA Cuc Software International and Others [2001] ECC 21.

36 E. Hettinger,'Justifying Intellectual Property' (1989) 18 Philosophy and Public Affairs 31.

37 H. C. Jehoram, Copies in Copyright (The Hague: Sijthoff& Noordhof 1980) 6.

? The Modern Law Review Limited 2005 415

This content downloaded from

14.139.214.181 on Mon, 21 Dec 2020 17:20:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Trouble with Moral Rights

transposed from their original medium onto a different surface. In Thdberge v Gal-

erie dA2rt du Petit Champlain Inc,38 the Canadian Supreme Court confined reproduc-

tion to 'multiplication' when it held that defendants who transferred posters onto

canvasses did not reproduce the original work. However, these reproductions can

infringe authors' moral rights if they do not identify the author and harm artistic

reputation if the public believes that the author's creativity is governed by com-

mercial imperatives or if botched copies create the impression that the author

poorly executed his work."39 The problem of botched copies may be addressed

by authors mounting a defamation claim against copiers40 who tarnish their artis-

tic reputation but defamation claims are predicated on publication which may not

have taken place in some cases. It is also unwise to use moral rights in cases where

copies of a work are used to make similar artefacts because to do so would pro-

scribe imitation, which is the lifeblood of creativity and competition.

Personality's interstitial links with physical objects may promote obsessive

interactions between authors and their works. This 'object-fetishism'41 may pre-

vent authors from developing other aspects of their personality and lead to private

censorship. In 1950, Giorgio de Chirico unsuccessfully attempted to use moral

rights to prevent an exhibition of his earlier works at the Venice Biennale42 while

the artist in Snow v The Eaton Centre Ltd successfully objected to anodyne and fleet-

ing interpretations of his sculpture.43 In Salinger v Random House,44 a reclusive

author successfully prevented an unauthorised biographer from accessing his pri-

vate correspondence while Stanley Kubrik, a film director, failed to prevent

balanced criticism of A Clockwork Orange by a terrestrial television channel.45 In

all four cases, the authors were minded to censor unauthorised exploitation of

their work. There is no litmus test for separating fetishism from genuine expres-

sions of personality. To avoid this difficulty, various jurisdictions generally use an

objective test when enforcing the right of integrity.46 Compulsory licensing may

also be used to prise copyright works from their authors' control but courts and

legislators use this remedy sparingly because it may reduce the royalties paid to

copyright owners, force individuals to speak to unfamiliar or unwanted audiences

and may infringe an author's privacy if the work is unpublished. The public inter-

est and fair dealing defences may also be used to disclose controlled information

but their practical application is redolent with inconsistencies.47

38 [2002] SCC 34

39 Dubuffett v Regie Nationale des Usines Renault [1980] ECC 417.

40 Eg Archbold v Sweet [1832] 172 ER 947.

41 SeeJ.W. Harris, Property andJustice (Oxford: OUP, 1996) 256-258 for a general discussion of fetish-

ism.

42 See J. H. Merryman and A. E. Elsen, Law, Ethics and the Visual Arts (The Hague: Kluwer,

2002) 316.

43 (1982) 70 CPR (2d) 105.

44 Salinger v Random House Inc and Anor 811 F 2d 90 (2d 1990).

45 Time Warner Entertainments Company LP v Channel FourTV Corporation plc and Anor [1994] EMLR 1.

46 Spanish Copyright Act Art 14(iv); German Copyright Act s 39(2); Morrison Leahy Music Ltd v

Lightbond and others [1993] EMLR 144 cf Snow v The Eaton Centre Ltd above; French IP Code Art

L121-1; but see C. McColley,'Limitations on Moral Rights in French Droit d'auteur' (1998) Copy-

right Law Symposium 423.

47 Hyde Park v Yelland [2001] 3 WLR 1172 (CA); Ashdown v Telegraph Group Ltd [2001] 3 WLR 1368

(CA).

416 t The Modem Law Review Limited 2005

This content downloaded from

14.139.214.181 on Mon, 21 Dec 2020 17:20:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Patrick Masiyakurima

Destruction of artefacts may be wilful, accidental, incremental or be a conse-

quence of war, unsympathetic conservation or legitimate uses of copyright

works.48 Various forms of partial destruction including deletion, mutilation or

distortion are usually outlawed but complete destruction is countenanced because

it may not harm authors' reputation and its prohibition may interfere with vested

property rights.49 At first glance, all forms of complete destruction are equally

deleterious to authors' personality interests but on closer inspection, the identity

of the destroyer is crucial to any assessment of complete destruction's effects on

personality rights. Destruction of copyright works by their authors may represent

a desire to project their personality through other means and may protect artistic

reputation if the destroyed works are of an unsatisfactory quality. However, this

destruction affects users because it leaves a significant lacuna in the references

available for measuring an author's overall career. On the other hand, wilful

destruction by buyers of copyright works eradicates the very objects that perso-

nify authors and diminishes opportunities for generating future commissionss5

especially where the destroyed work is not widely reproduced. This type of

destruction deserves the strongest opprobrium because it may be possible to safe-

guard the author's personality interests by obliging the copyright owner to offer

the work to its author before destroying it or to reproduce or photograph the

work if it cannot be returned to its author.51 Similarly, state-sponsored destruction

such as the destruction of the Stari Most Bridge in Bosnia attracts serious criticism

because it is a censorship tool and it can be prevented by securing the work ade-

quately. Destruction of copyright works by an author's heirs raises nettlesome

conflicts between preserving an author's vision of himself and respecting the priv-

acy interests of those who must live in the shadow of that vision.Where the public

destroys copyright works, it is intuitive to protect authors because they may lose

the physical embodiment of their personality but it is equally important to ensure

that users have sufficient latitude to reject works that confront their own person-

ality. For instance, the decapitation of Lady Thatcher's statue symbolised an indi-

vidual's deep-seated contempt of the political values she espoused.52 Although the

statue's destruction may have exceeded the boundaries of free speech, it neverthe-

less generated conflicts between personality and free speech rights. All these

imponderables make the task of formulating an appropriate legislative framework

for regulating destruction of copyright works almost Herculean.

A related point involves forced removals of context-specific works from their

intended environment and exhibitions of copyright works in inappropriate con-

texts. At face value, this treatment may not harm the personality of authors

because the works are not destroyed or physically transformed and they can be

redisplayed elsewhere."3 However, forced removals and prejudicial exhibitions

48 D. Gamboni, The Destruction ofArt (London: Reaktion Books, 1997).

49 J. H. Merryman,'The Refrigerator of Bernard Buffet' (1976) 27 Hastings LJ 1023,1047.

50 A. Dietz,'The Artist's Right of Integrity Under Copyright Law-A Comparative Approach' (1994)

25 IIC 177, 191.

51 Swiss Copyright Act, Art 15.

52 L. Smith and D. Alberge,'HowThatcher lost her head for crimes of state' The Times 5 July 2002.

53 A. Dietz,'The Artist's Right of Integrity Under Copyright Law-A Comparative Approach' (1994)

25 IIC 177,192.

? The Modem Law Review Limited 2005 417

This content downloaded from

14.139.214.181 on Mon, 21 Dec 2020 17:20:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Trouble with Moral Rights

may alter the work's intended meanings. Arguably, the uprooting of Richard

Sierra's Tilted Arc54 from its prime location diluted the artist's meaning even if the

work was capable of being displayed elsewhere. The main drawback of this argu-

ment is that since context-specific works are often displayed in public places, the

public should not be forced to appreciate works which seriously offend its aes-

thetic judgment."ss Given that context-specific works may heavily rely on works

created by other authors for their overall success, the spectre of conflicting moral

rights would arise if the various authors were to argue that the integrity of their

work is compromised by the inclusion of a context-specific work. Additionally,

despite seriously annihilating the author's personality, removal of context specific

works may offer the best compromise between author and user rights because the

work is preserved and may be redisplayed in its intended environment if public

opinion changes.

Commercial pressures may force authors to forgo their rights in advance espe-

cially where a work is produced collectively or where it must be adapted to suit

different media. Waivers relating to future works can be justified because they do

not assault authors' reputation since a work approximating the author's personal-

ity does not exist at the conclusion of the contract.56 Waivers may also enable

authors to project their personality to new audiences through future adaptations

of their work. Additionally, the proceeds from waivers may be used to develop

other aspects of authors' personality57 In the event that copyright owners engage

in sharp practices, various remedies including undue influence and unconscion-

ability are at authors' disposal.58 Conversely, systematic waivers imply that authors

have no control over their personality. A more troubling question is whether a

person can consent to serious assaults on her personality. True, some authors

may be prohibited from exercising their rights of freedom of expression in the

interest of national security59 but superimposing commercial interests over per-

sonality rights exposes budding authors to rampant commercial exploitation.60

Additionally, impecunious budding authors may not have access to the courts

and if they do, the application of common law doctrines would yield uncertain

results.61

One of the lowest common denominators of personality interests is that they

terminate at their holder's death. Moral rights protection departs from this usual

scheme by exceeding the natural life of authors. Although this disparity is usually

ascribed to the immortality of art and the perpetuation of the spiritual interests of

authors through their work,62 this approach does not explain why these interests

54 Serra v US General Services Admin 847 F 2d 1045 (1988); Phillips v Pembroke Real Estate Inc 288 F Supp

2d 89 (2003).

55 J. L. Sax, Playing Darts with a Rembrandt (Michigan: Michigan University Press, 1999) 27.

56 Gabon v Societe Nationale De7eJlevision En Couleurs Antenne 2 [1988] ECC 316.

57 J. Hughes,'The Philosophy of Intellectual Property' (1988) 77 Georgetown LR 287, 344.

58 Eg Schroeder Music Publishing Co Ltd v Macaulay [1974] 3 All ER 616 and Clifford Davis Management

Ltd v WEA Records Ltd and Anor [1975] 1 All ER 237.

59 Att Gen v Guardian Newspapers [1990] AC 109.

60 Cornish, n 28 above, 49-50.

61 D. Vaver, "'Authors' Moral Rights-Reform Proposals in Canada: Charter or Barter of Rights for

Creators?' (1987) 25 Osgoode Hall LJ 749, 777.

62 W Strauss,'The Moral Right of the Author' (1955) 4 Americanjournal of Comparative Law 506, 517.

418 C The Modern Law Review Limited 2005

This content downloaded from

14.139.214.181 on Mon, 21 Dec 2020 17:20:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Patrick Masiyakurima

should be preserved for a specific period after an author's death. Arguably, perpe-

tual moral rights address this shortcoming but they may strangle adaptations of

famous works indefinitely. Another vexing issue raised by post mortem moral

rights protection is identifying the guardian of the author's personality after her

death. Although heirs are the natural candidates for preserving their illustrious

ancestor's personality, they may fail to act, use moral rights abusively,63 permit

prejudicial changes to copyright works or destroy the works for various reasons

including enhancing the economic value of the remaining works64 or securing

their own privacy. Given that moral rights are designed to ensure that the public

is acquainted with an author's personality as its author intended it,65 it may be

competent for public interest organisations to enjoin heirs' abuses of copyright

works. Although public bodies rarely enforce moral rights66 due to financial con-

straints and inertia, in Foujita v Sarl ACR and others,67 the French Minister of Cul-

ture successfully intervened in a case where an heir abused her moral rights by

failing to allow publication of a book on her distinguished husband's life and

career. However, this decision may cause difficulties if heirs further their own eco-

nomic interests by permitting serious and prejudicial changes to copyright

works.68 Where that is the case, it may be inappropriate for a court to deprive heirs

of an opportunity to benefit from the economic advantages attached to their fore-

bear's works. These discussions mask the inescapable conclusion that copyright

duration is largely designed to confer limited monopolies on enterprises that

invest in cultural products.

Freedom of expression

Some authors express their views solely for circulating information necessary for

exercising democratic choices,69 fostering truth70 or promoting self-actualisa-

tion.7' Generally, copyright is congruent with freedom of expression because it

may provide the economic incentives required for creating socially useful expres-

sion.72 Where appropriate, various copyright internal balancing measures includ-

ing originality, the idea/expression dichotomy, compulsory licensing, the public

interest defence and fair dealing preserve access to these cultural expressions.73 For

instance, in Fabris v SA Nationale de Television France 2,74 the court subordinated an

63 Eg Widmaier v SPADEM and Others [1993] ECC 38.

64 Sax, n 55 above, 146.

65 Of course, the author's intentions must be interpreted objectively to minimise moral rights

abuses.

66 E Pollaud-Dulian,'Moral Rights in France,Through Recent Case Law' (1990) 145 RIDA 126, 244.

67 [1988] ECC 309.

68 Sax, n 55 above, 146.

69 A. Meiklejohn,'The First Amendment is an Absolute' [1961] Supreme Court Review 245.

70 E. Barendt, Freedom of Speech (Oxford: OUP, 1985).

71 E Schauer, Free Speech: A Philosophical Enquiry (Cambridge: CUP, 1982) chs 4-5.

72 W M. Landes and R. A. Posner, An Economic Analysis of Copyright Law' (1989) 18 Journal of

Legal Studies 325, cf S. Breyer,'The Uneasy Case for Copyright: A Study of Copyright in Books,

Photocopies, and Computer Programs' (1970) 84 HarvLR 281.

73 N.W. Netanel,'Copyright and a Democratic Civil Society' (1996) 106 Yale LJ 283.

74 [2000] ECC 258.

? The Modern Law Review Limited 2005 419

This content downloaded from

14.139.214.181 on Mon, 21 Dec 2020 17:20:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Trouble with Moral Rights

author's copyright to the vital importance of disseminating news to the public.

The free speech benefits of moral rights protection are pronounced in cases invol-

ving expressions created by burgeoning authors who may lack the opportunity to

ventilate their ideas in widely disseminated media. For instance, the paternity

right prevents misattribution of expressions and associates or dissociates authors

with their expressions while the right of integrity preserves an author's message

from unauthorised interferences. Generally, the self-actualisation basis of freedom

of expression is a component of personality rights75 but the free speech justifica-

tion for moral rights protection advanced here largely focuses on the public ben-

efit of widespread dissemination of authentic cultural information. Additionally,

it is conceivable that expressions created by some authors may promote vital pub-

lic interests without reflecting their authors' personality.

An exercise of the right of disclosure may significantly impede freedom of

expression especially in cases involving important unpublished information. Sev-

eral factors influence judicial and legislative policies in this area. First, the right of

disclosure may safeguard a private space where authors may distil their ideas

before publication. During this creative period, user access to the work is pro-

scribed. This temporary censorship is usually countenanced because it contem-

plates eventual authorised disclosure of the information76 and prevents

misappropriation of valuable unpublished information by subordinating users'

freedom of expression to protection of copyright owners' commercial interests.77

Apart from safeguarding the creative environment, the right of disclosure may be

congruent with the self-actualisation basis of freedom of expression because it

entitles authors to express ideas which best encapsulate their personality when

they are ready to do so. However, there is a danger that publishers may refuse to

publish commercially risky expressions7" or the author may decide against pub-

lishing the information. Even if the copyright work is eventually published,

delayed publication may rob the work of its relevance to current debates. In the

hands of overzealous heirs, the right of disclosure may also be a useful tool for

censoring disclosures of embarrassing family secrets. For example, in Cohen and

Champigny v Chain and Others,79 a deceased author's heirs successfully relied on

the right of disclosure to curtail widespread dissemination of details of their pre-

decessor's scandalous sexual life. Secondly, judges' are reluctant to condone inva-

sion of authors' privacy by sanctioning unauthorised disclosures of unpublished

works.8o However, using copyright to prevent widespread dissemination of pri-

vate information is antithetical to copyright policy because it may protect the

ideas or facts in a copyright work. Thirdly, courts may use copyright to minimise

disclosures of confidential information."8 The anti-dissemination effects of the

75 Pound, n 16 above, 445.

76 Harper & Row, Publishers Inc v Nation Enterprises 471 US 539 (1985), 555.

77 Ashdown v Telegraph Group Ltd [2001] 3 WLR 1368 (CA); Hyde Park Residence Ltd v Yelland [2000] 3

WLR 215 (CA).

78 Morang & Co v Le Sueur (1911) 45 SCR 95 (Canada); Malcolm v Oxford University Press [1994] EMLR

17.

79 [1983] ECC 318.

80 T. DeTurris,'Copyright Protection of Privacy Interests in Unpublished Works' [1994] Annual Sur-

vey of American Law 277, 288.

81 Beloff v Pressdram Ltd [1973] 1 All ER 241, Hyde Park Residence Ltd v Yelland, n 77 above.

420 ? The Modem Law Review Limited 2005

This content downloaded from

14.139.214.181 on Mon, 21 Dec 2020 17:20:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Patrick Masiyakurima

right of disclosure are exacerbated by courts' reluctance to condone non-transfor-

mative uses of copyright works.82 Thus, mere disclosure of important informa-

tion may not ground a fair dealing or public interest defence in some

jurisdictions.83

At face value,'originality' fosters dissemination of high quality information to

the public. Coupled with a proper application of the idea/expression dichotomy

and other copyright exceptions it also ensures that unprotected expressions are

available for subsequent speakers. However, save for a few exceptions,84 commer-

cial necessities often mean that 'originality' generally focuses on the effort and skill

invested in creating a copyright work rather than creativity.85 There is something

to be said for this approach. Individuals of varying ability must be afforded

opportunities to express themselves freely. A low test of 'originality' addresses this

concern by extending copyright protection to expressions created by less able

authors. Nevertheless, a low test of 'originality' lends itself to serious criticism

because it fences off large quanta of information thereby overprotecting earlier

speakers at the expense of subsequent users. This shortcoming is exacerbated by

the expansive interpretation of substantial infringement,86 the weaknesses of the

idea/expression dichotomy, and the constriction of copyright exceptions such as

fair dealing which limit public access to popular expression.87

Copies present the free speech basis of moral rights protection with an identical

dilemma. First, given the ease of distribution of cultural expressions on the inter-

net and in other cultural media, authorised reproductions of copyright works

optimise the avenues for widespread dissemination of an author's authentic

expressions. The availability of copies of a work may also ameliorate the negative

effects of destruction because authors may ventilate their opinions in the remain-

ing copies. Secondly, a rigid treatment of unauthorised copies of a work impedes

adaptations of popular expressions and may cause an artificial scarcity of informa-

tion. Most jurisdictions balance these conflicting ideals through copyright excep-

tions sanctioning unauthorised uses of copyright works.88 However, this

accommodation creates its own problems because it largely depends on a factual

analysis of individual cases. Consequently, the uncertainties surrounding the var-

ious exceptions may chill free speech because users may not have advance knowl-

edge of what constitutes legitimate copying.

'Complete destruction' censors an author's views especially where the work is

not mass-produced. In the 1950s or 1960s, Lady Churchill effectively censored an

unflattering portrait of her distinguished husband by secretly destroying it. Simi-

larly, the Rockefellers censored Diego Rivera's mural denouncing the excesses of

capitalism by ordering its destructive removal from one of their flagship offices.

82 Rv]ames Lorimer & Co Ltd (1984) 1 FC 1065.

83 Ibid.

84 Eg Art 3(1) of the Database Directive, Metix (UK) Ltd and Anor v G. H. Maughan (Plastics) Ltd and

Anor [1997] FSR 718 and Lambretta Clothing Co Ltd v Teddy Smith (UK) Ltd [2005] RPC 6.

85 A. Birrell, Copyright in Books (London: Cassell, 1899) 144.

86 Designers Guild Ltd v Russell Williams (Textiles) Ltd, n 20 above.

87 Eg Art 6 Directive 2001/29/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 May 2001 on

the Harmonisation of Certain Aspects of Copyright and Related Rights in the Information

Society, OJ L 167, 22.6.2001.

88 Eg UK CDPA 1988, s 29 et seq.

? The Modern Law Review Limited 2005 421

This content downloaded from

14.139.214.181 on Mon, 21 Dec 2020 17:20:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Trouble with Moral Rights

This form of censorship must be reconciled with the possibility that individuals

may express themselves by destroying copyright works expressing polarising

views.89 For instance, the stage-managed destruction of Saddam Hussein's statue

by an Iraqi crowd and the American army in central Baghdad expressed the end of

a much-maligned dictatorship. Arguably, these notorious destructions have the

paradoxical effect of disseminating the views expressed by the work widely but

they remove the means of verifying the expressions. A potentially irresistible

argument which can be mounted against political destruction is that it is a dispro-

portionate and wasteful response to the messages conveyed by copyright works.

Political destruction diminishes a nation's cultural patrimony and ignores the pos-

sibility that time may purge the political connotations of the work.90 Serious pro-

blems also arise if authors destroy their original works. On the one hand, it may

be argued that authors who withdraw their expressions from the public are exer-

cising their personality rights but users who are familiar with the destroyed

expressions may lack a ready reference for the views that affected them. However,

the potency of this argument is seriously weakened if the work in question was

produced en masse.

Various factors including encryption technologies91 and the weakness of copy-

right's internal balancing processes limit access to authors' expressions thereby

diminishing the free speech benefits of moral rights protection.92 Authors and

copyright owners are animated by several considerations when they proscribe

access to copyright works. For instance, some authors and their heirs may wish

to preserve their privacy by withholding publication of personal information and

users who trespass this zone of personal autonomy may breach the right of dis-

closure. In a French case, the disaffected heirs successfully relied on their moral

rights to limit the dissemination of excoriating criticisms of their predecessor's

intellectual rigour and moral turpitude.93 Other authors may rely on their moral

rights to limit access to their less important works or maximise their economic

returns. For instance, Giorgio De Chirico relied on his moral rights to censor an

exhibition of his earlier works at the Viennese Biennale. However, a German

court recognised the benefits of freedom of expression when it allowed an anti-

smoking lobby group to use the claimant's work to propagate an anti-smoking

message.94 Apart from these considerations, an exercise of the right of repentance

may enhance authors' personality but it prevents access to works that are not mass-

produced. These deficiencies explain why numerous jurisdictions protect users'

freedom of expression by requiring proof of harm to honour or reputation when

authors enforce the right of integrity.95

89 J. L. Sax, n 55 above, 17.

90 D. Gamboni, The Destruction of Art (London: Reaktion Books, 1997) 22.

91 S. Dusollier, 'Exceptions and Technological Measures in the European Copyright Directive of

2001-An Empty Promise' (2003) 34 IIC 62.

92 C. B. Graber and G. Teubner, Art and Money: Constitutional Rights in the Private Sphere?'

(1998) 18 OJLS 61, 68.

93 Editions Gallimar~ Jean Camus and Catherine Camus v Hamish Hamilton [1985] ECC 574.

94 Re the Parodying of CigaretteAdvertising [1986] ECC 1.

95 Eg Belgian Copyright Act, Art 1(2); German Copyright Act, s 39(2) and Spanish Copyright Act,

Art 14(iv).

422 ? The Modern Law Review Limited 2005

This content downloaded from

14.139.214.181 on Mon, 21 Dec 2020 17:20:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Patrick Masiyakurima

Jurisdictions which exclude moral rights protection from works created by

employees in the course of their employment96 potentially allow corporate greed

to stifle weak voices.97 However, it may be posited that employees who enter into

employment contracts vesting future copyright works in their employers may be

deemed to have waived their right to control future uses of their expressions. The

unanswerable objection to this argument is that generally, assignment of copy-

right does not affect moral rights.98 A more persuasive argument is that authors

who create in pursuance of an employment contract may not rely on their right to

speak freely because their employers demarcate the parameters and exploitation of

the speech. Additionally, given the amount of collaboration that takes place in

most workplaces, granting moral rights to individual employees would also

impede future adaptations of copyright works if any one of the authors objects

to the adaptation. Although authors of commissioned works who create under

nearly similar circumstances retain their moral rights, the degree of supervision

required for commissioned works is sufficiently low to allow the inference that

the author largely expresses her own views in the finished product. In any event,

the author of a commissioned work retains her copyright in the work. Even if

works created by employees were to benefit from moral rights protection, serious

problems may surface after the employment contract is terminated. On balance,

since the work would have been created for a specific employer, employees must

not use the work as they please. These shortcomings demonstrate the problems

caused by trying to justify the allocation of what are essentially individual rights

to artificial legal persons who are mainly motivated by the profitability of their

various undertakings. Apart from posing problems to copyright theory, the par-

ticipation of companies in the distribution of artistic discourse is usually coloured

by financial considerations which may exclude important but financially unat-

tractive expressions from public circulation.99 This danger is largely ignored

because courts may not see any urgency in resolving human rights disputes

between publishers and users even if the disputes implicate issues of cardinal pub-

lic importance.100

Interferences with freedom of expression through waiver of moral rights do

not chart new territory. Individuals may enter into contracts compromising their

right to speak freely for various purposes including protecting national security.

Nevertheless, there is a vast gap between protecting vital public interests and pro-

moting the economic interests of copyright owners. A relentless pursuit of copy-

right owners' rights may force powerful financial interests to override or distort an

author's message through botched or unsympathetic adaptations. Additionally, it

may be argued that routine waivers may permit destruction of copyright works

thereby expunging authors' expressions. These risks are usually associated with

burgeoning authors who may lack the muscle to force copyright owners to treat

their expressions with consideration. However, these arguments must be recon-

96 Eg USA Copyright Act, s 101.

97 Y. Gendreau, 'Copyright and Freedom of Expression in Canada' in P. Torremans (ed), Copyright

and Human Rights (The Hague: Kluwer, 2004) 21, 24.

98 Eg UK CDPA 1988, s94.

99 Malcolm v Oxford University Press [1994] EMLR 17.

100 R. Abel, Speech and Respect (London: Sweet & Maxwell, 1994) 48-58.

? The Modern Law Review Limited 2005 423

This content downloaded from

14.139.214.181 on Mon, 21 Dec 2020 17:20:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Trouble with Moral Rights

ciled with the possibility that waivers may also bolster freedom of expression

especially if they allow sympathetic adaptations of copyright works. Where such

authorised adaptations occur, waivers allow authors to propagate their expressions

to potentially new audiences.

Sometimes, copyright's limited duration may guarantee the authenticity of

expressions until they withstand the test of time. However, there is little empirical

evidence to buttress this claim. In fact, some famous expressions have survived in

the absence of copyright protection. In any event, heirs may allow significant

interferences with their predecessor's expressions during the subsistence of copy-

right. Coupled with the low test of originality and the imprecision of other copy-

right tools, an unduly long copyright term impedes access to contemporary

information. In some instances, the end of the copyright term does not enhance

public access to copyright works because authors and their heirs may refuse to sell

or disclose unpublished information. Even where the information is published

and the copyright term has ended, users do not normally have unbridled access

to private collections of copyright works. Once again, commercial necessities take

precedence over the public interest.

Cultural heritage

Various measures including repatriations of looted artefacts, publicly funded

acquisitions of art, export restrictions on iconic works and conservation of treas-

ures reflect the public interest in preserving cultural property for historical, aes-

thetic or socio-economic reasons. Copyright may augment our cultural

patrimony by granting authors significant incentives for creativity. Once created,

various copyright exceptions such as fair dealing, compulsory licensing and the

public interest defence may facilitate public access to important cultural works.101

At a different level, moral rights complement national heritage laws by allowing

individuals to vindicate the public interest in cultural heritage preservation. For

instance, the right of integrity outlaws prejudicial changes to cultural treasures

while the right of access may be a useful tool for conserving copyright works in

another's possession. Similarly, the right of attribution identifies authors of

important cultural icons thereby facilitating informed and sympathetic conserva-

tion of these works. However, the right of repentance may be inconsistent with

cultural heritage preservation because it subordinates the public interest to the

self-interest of individual authors. The major difference between the personality

and cultural heritage bases of moral rights protection is that instead of advancing

the interests of authors, the cultural heritage argument is principally concerned

with enhancing the public interest. Of course, public institutions may police

national heritage violations but their activities may be crippled by budgetary con-

straints or inertia.

Discussions on moral rights and cultural heritage protection imply compre

hensive public access to important literary and artistic works. Public access t

101 A. Frangon, 'Authors' Rights Beyond Frontiers: A Comparison of Civil Law and Common Law

Conceptions' (1991) 149 RIDA 2, 4.

424 0 The Modem Law Review Limited 2005

This content downloaded from

14.139.214.181 on Mon, 21 Dec 2020 17:20:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Patrick Masiyakurima

national cultural patrimony is necessitated by the aesthetic and educational value

of the artefacts. True, access to some works must be restricted in the interest of

conservation, security and privacy. However, the exclusive property rights stem-

ming from copyright ownership coupled with the right to privacy conspire to

reduce meaningful public access to culturally significant works stored in private

residences. Although this problem is ameliorated by granting tax incentives to

collectors who allow public access to their collections,102 the access granted by

private owners may be limited and some wealthy collectors may ignore these

tax breaks. In any event, some private collectors reside in tax havens thereby ren-

dering the benefits of inheritance tax breaks remotely attractive. Anonymous auc-

tion sales compound the problem of public access to private collections by

making it nearly impossible to locate the location of important works. For

instance, despite offering useful research insights into their authors' life and artistic

techniques, both Maria Callas' private correspondence and Pablo Picasso's Nu au

collier were sold to anonymous collectors in 2002.103 These anonymous sales also

paralyse the value of moral rights as a measure for preserving our cultural heritage

because authors may not know the fate of their works once they have been spir-

ited away to their secret owners. Even where limited access is possible, fragmented

location of an author's principal works at various private residences impedes the

ability of researchers to study the works together.

The low test of originality in most jurisdictions104 sits uneasily with accepted

definitions of cultural heritage which focus on extraordinary and rare artefacts.105

A weak originality test also generates serious arguments about who should deter-

mine the cultural status of copyright works. The dimension of self-interest ensures

that even modestly skilled authors may inflate the cultural status of their creations.

The available evidence also suggests that judges do not have the requisite skills to

make aesthetic judgments106 while expert evidence is often tainted by the con-

straints of parochial training and adversarial litigation.107 In any event, it is unde-

mocratic to bestow the function of determining the cultural status of objects on

unelected individuals who may disregard avant-garde works.108 Arguably, public

surveys are the best tool for approximating the public interest in preserving our

cultural heritage'09 but they are expensive to commission and the public may

exhibit its philistinism by disregarding new works. The solution to this old chest-

nut is to use a partly subjective and partly objective test which accommodates the

best available evidence from authors, the public and experts. In the final analysis, a

low test of originality is an arbitrary line which is drawn to accommodate busi-

ness and aesthetic interests but it leaves copyright systems with no sieve to separate

culturally significant from ordinary works.

102 Eg Inheritance Tax Act 1984 (UK), s 31.

103 http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/arts/2064625.stm and http://news.bbc.co.uk/l/hi/enter

tainment/arts/2520071.stm.

104 Eg Ladbroke v William Hill [1964] 1 All ER 465; Hay v Sloan (1957) 2 DLR (2d) 397.

105 Eg UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export

and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property, November 14,1970, 823 UNTS, 234, 236.

106 George Hensher v Restawile Upholstery (Lancs) Ltd [1976] AC 64.

107 Eg Thomson v Christie Manson & Woods Ltd and others [2004] EWHC 1101 (QB).

108 D. Gamboni The Destruction of Art (London: Reaktion Books, 1997) 167.

109 Eg Tidy v Trustees of the Natural History Museum (1997) 39 IPR 501.

? The Modem Law Review Limited 2005 425

This content downloaded from

14.139.214.181 on Mon, 21 Dec 2020 17:20:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Trouble with Moral Rights

Complete destruction of original works generally reduces the corpus of cul-

tural artefacts especially where the work concerned is not mass-produced but it

takes a controversial twist if authors destroy their own works. Given that a fin-

ished work may be culturally significant, allowing authors to destroy their fin-

ished work concentrates the power to determine the fate of cultural objects in

one self-interested individual. This issue reflects the difficulties existing at the

interface of the personality and cultural heritage justifications for moral rights

protection. While authors may discard their earlier personality by destroying their

work, cultural heritage preservation would disapprove destruction of existing

treasures irrespective of its source. These arguments apply with equal force to pre-

judicial alterations of copyright works by their authors. However, unfinished

works are in a different league because their very nature envisages failure or sub-

sequent change. Destruction also pits the cultural heritage and freedom of expres-

sion rationales of copyright protection against each other. For example, the

destruction of Saddam Hussein's statue in Baghdad was a stage-managed exercise

of freedom of expression but it depleted Iraq's cultural treasures. Similarly,

destruction of a dead author's unpublished works creates tensions between main-

taining culturally significant information and heirs' privacy interests. Arguably,

freedom of expression and privacy conflicts may be resolved in favour of cultural

heritage preservation because time may neutralise the work's political and privacy

connotations. Lastly, it must be noted that in exceptional circumstances, destruc-

tion of treasures may yield unintended positive outcomes.Very few events under-

line the serious dangers of religious extremism more than the state-sponsored

dynamiting of the Bamyan Buddhas in Afghanistan.

Generally, decisions to interfere with cultural landmarks are usually made after

extensive public consultation.Waivers strike at the heart of this democratic process

by granting authors the sole discretion to permit changes to culturally significant

works. Apart from being undemocratic, routine waivers may also harm cultural

works created by budding authors who usually lack the muscle to prevent unwar-

ranted changes to their works. Waivers relating to future copyright works raise

different considerations because society may not know the cultural value of the

work at the time the waiver is made. However, waivers relating to future works

expose culturally significant works to commercial vagaries once they have been

created. Nevertheless, blanket bans on waivers are inappropriate because they stifle

widespread appreciation of cultural works arising from sympathetic adaptations

of important works. That argument apart, creators of valuable works must have

the opportunity to maximise their financial interests through waivers and must

not be forced to contribute disproportionately to the public interest. Permissions

may offer the best solution to the conflicts between waivers and cultural heritage

preservation because they force copyright owners to consider the full ramifica-

tions of any proposed changes to important works before making an application

to the appropriate authorities. Although these permissions are used regularly

when modifications are proposed to the built heritage, unless there are strong

legislative provisions that combat abuse of moral rights, seeking permission to

change collaborative works is fraught with difficulties.

The end of the copyright term may leave some valuable cultural treasures dan-

gerously exposed in the hands of private collectors. Of course, owners of impor-

426 ? The Modern Law Review Limited 2005

This content downloaded from

14.139.214.181 on Mon, 21 Dec 2020 17:20:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Patrick Masiyakurima

tant works may be reluctant to implement changes that devalue their investments

but the absence of moral rights protection may tempt some copyright owners to

implement unwarranted changes to their works. Despite this gloomy picture,

copyright's limited duration may have some hidden benefits. During the subsis-

tence of copyright, the public and experts may form a rough consensus on the

cultural status of some copyright works. Works of insufficient merit are left to

the vagaries of the public domain while culturally significant works would ben-

efit from public heritage laws including export restrictions. The end of the copy-

right term therefore sifts banal works from cultural treasures. Another argument

in favour of a limited copyright term is that it frees the raw materials needed for

creating works of cultural importance. That possibility notwithstanding, public

access to the most outstanding treasures may be limited by various factors includ-

ing conservation, security and ownership of the works by private collectors.

Extending moral rights protection to copies of original works anticipates the

problems arising from loss or destruction of cultural treasures but it may over-

protect our cultural heritage and diminish transformative uses of copyright

works. Another vexing question is generated by the production of identical but

unauthorised copies of an original work. Apart from being potential instruments

of fraud, these fakes poison the wells of cultural authenticity and waste scarce con-

servation resources and museum space.110 Even if the public knows that a work is

faked, time may blur the distinctions between copies and originals thereby intro-

ducing high authentication costs."' Strictly speaking, the right against misattribu-

tion of authorship is not a moral right because it can be claimed by non-authors.112

Instead, it shares common features with a passing off claim because it is aimed at

preventing misappropriation of the goodwill in another's name. However,

viewed through the prism of cultural heritage preservation, the right against mis-

attribution of authorship minimises some of the negative consequences of fakes

on our cultural heritage by granting authors the right to deny authorship of the

work if fakes are attributed to them. Arguably, an unauthorised but aesthetically

superior copy of an original work may deserve copyright or moral rights protec-

tion because it develops the ideas in the original work. Additionally, outlawing

these copies fails to recognise the incremental nature of modern creativity.

It may be important to recognise the creativity of employed authors as a mea-

sure of social reward and historical accuracy but that generosity is not extended to

employed authors in the United Kingdom."113 Presumably, the UK treats

employed authors differently because copyright works are capable of numerous

adaptations and abusive exercises of moral rights by individual employees may

impede wholesale exploitation of cultural products. Additionally, employees are

generally mobile and it may be administratively inefficient for companies to

apportion the creation of finished products. Nevertheless, excluding works cre-

ated by employed authors from moral rights protection severs the links between

cultural works and their 'creators'. To prevent employers from abusing this loop-

110 J. H. Merryman,'Counterfeit Art' (1992) 1 InternationalJournal of Cultural Property 27.

111 Thomson v Christie Manson & Woods Ltd and others [2004] EWHC 1624 (QB).

112 Clark vAssociated Newspapers Ltd [1998] 1 All ER 959.

113 Eg UK CDPA 1988, s 79(3).

? The Modern Law Review Limited 2005 427

This content downloaded from

14.139.214.181 on Mon, 21 Dec 2020 17:20:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Trouble with Moral Rights

hole, public heritage laws must be used to preserve outstanding works once their

cultural relevance has been ascertained by independent bodies.

Authenticity

Moral rights protect authors and copyright owners' pecuniary interests by safe-

guarding the authenticity of copyright works. The authenticity basis of moral

rights protection is largely similar to the cultural heritage argument in that it pro-

motes truth in artistic and literary discourse. The only difference between the two

justifications is that authenticity is a hybrid interest designed to preserve the eco-

nomic benefits of copyright transfers, the rights of consumers and the public

interest in maintaining accurate artistic records. Moral rights are especially rele-

vant to old works because their authentication becomes increasingly difficult with

time.114 Authenticity also matters because fakes may be used to defraud consumers

and may result in a wasteful allocation of scarce museum resources."5 Moral rights

promote authenticity in several ways. The right of attribution markets an author's

works by identifying their provenance and prevents misattribution of inferior

works to successful authors thereby reducing consumer search costs.16 Correct

attribution of copyright works may also substantially affect the price commanded

by copyright works.17 In 2002, Rubens' The Massacre of the Innocents was sold for

nearly ?50 million largely because it was attributed to the old master rather than

one of his followers.18 Similarly, in Thomson v Christie Manson & Woods and

Others,119 an attribution of rare French urns to a later artist rather than Enne-

mond-Alexandre Petitot significantly altered the value of the urns. Of course, in

both instances, the work remained the same but its selling qualities derived from

its association with a specific author. Similarly, the right of integrity preserves the

resale value of copyright works and minimises loss of future commissions or sales

by prohibiting unauthorised interferences with copyright works.120

Apart from diminishing economic returns to authors, fakes introduce signifi-

cant search costs into the art market, defraud consumers and may prevent buyers

from entering into repeat transactions if they doubt the authenticity of their pur-

chases.121 Outlawing unauthorised copies of copyright works is therefore neces-

sary especially where significant time has lapsed since the creation of the original

work. This consumer protection function of moral rights also assumes great

importance to buyers who cannot afford independent expert advice. However,

serious theoretical problems arise if forgers make better copies of original works

because in these circumstances it may well be argued that the better copy repre-

114 Thomson v Christie Manson & Woods and Others [2004] EWHC 1101 (QB).

115 Merryman, n 110 above.

116 Hansmann and Santilli, n 34 above, 130-131; D.Vaver,'Moral RightsYesterday, Today and Tomor-

row' (1999) 7 InternationalJournal of Law and Information Technology 270, 276.

117 J. C. Ginsburg,'The Right to Claim Authorship in U.S. Copyright and Trademarks Law' (2004) 41

Houston LR 263, 265.

118 See http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/main.jhtml?xml=/news/2002/07/11/nrubell.xml.

119 [2004] EWHC 1101 (QB).

120 J. Ginsburg,'Moral Rights in a Common Law System' [1990] EntLR 121,122.

121 Thomson v Christie Manson & Woods and Others [2004] EWHC 1101 (QB).

428 ? The Modern Law Review Limited 2005

This content downloaded from

14.139.214.181 on Mon, 21 Dec 2020 17:20:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Patrick Masiyakurima

sents a new commodity deserving independent copyright and moral rights pro-

tection. However, given that authenticity is not confined to aesthetic merit,

buyers who purchase the better copy believing it to be an original work by

another author must be protected from this misrepresentation. Conversely, pro-

scribing similar copies of original works ignores the derivative nature of modern

creativity. For that reason, a French decision sanctioning reproduction of an artist's

signature without creating consumer confusion122 recognised the proper limits of

the authenticity argument. For authenticity purposes, if a copy of a work does not

cause consumer confusion, it must be immunised from copyright infringement

suits if future creativity is to be freed from economic shackles. However, this rea-

soning clashes with the cultural heritage rationale of moral rights protection

because with the passage of time these similar or identical copies may cause diffi-

culties when authenticating the original work.

Theoretically, waivers may be perceived as a statement of an author's wishes

regarding the consumption of her work. For instance, voluntary waivers may

indicate that authors view their work as being capable of significant changes and

various interpretations to meet the needs of different consumers over time. Where

that is the case, authenticity is not seriously affected if the buyer's attention is

drawn to the fact that alterations to a work are a result of properly obtained waiv-

ers. However, a different picture emerges if one prods beneath the surface of this

argument. The usual position is that apart from cases involving singularly original

works created by well-known authors, decisions on commercial exploitation of

copyright works are usually reserved for copyright owners. At a different level, if

authenticity is a consumer protection device then undisclosed waivers subtract

from that interest because consumers may unwittingly buy altered works without

knowing that authors and copyright owners agreed on serious changes to the ori-

ginal work. Moreover, consumers bent on acquiring significant works would

incur significant search costs when establishing the authenticity of the work con-

cerned. At another level, whether or not authors object to prejudicial adaptations

arising from authorised waivers may be irrelevant if consumers know that they

are buying altered works. Nevertheless, prejudicial alterations may constitute a

serious assault on an author's personality and imperil our cultural heritage. Argu-

ably, absolute prohibitions on waivers cure this defect but they may diminish the

resale value of the work if it needs subsequent adaptations. All these problems are

ameliorated by the likelihood that authors who have confidence in their creative

powers may sell their works for a higher price if the public knows that they do not

compromise their principles.123 However, this argument presupposes that consu-

mers are acutely familiar with the convictions of individual authors.Where copy-

right owners improperly interpret waivers, authors whose honour or reputation is

harmed by authorised alterations must be given the opportunity to enforce their

moral rights.124 This solution provides a proper balance between the commercial

interests of authors and copyright owners.

122 A. Lucas and P. Kamina,'France' in P. E. Geller and M. B. Nimmer (eds), International Copyright

Law and Practice (NewYork: Matthew Bender, 2003) 98.

123 Hansmann and Santilli, n 34 above, 128.

124 Belgian Copyright Act, Art 1(2).

? The Modem Law Review Limited 2005 429

This content downloaded from

14.139.214.181 on Mon, 21 Dec 2020 17:20:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Trouble with Moral Rights

Altered or destroyed works add further wrinkles to the problems surrounding

the authenticity basis of moral rights protection. Arguably, consumers who buy

copyright works knowing that they were altered cannot complain about the

work's authenticity125 but if authenticity extends to artistic truth then

unauthorised alterations misrepresent an author's views. Additionally, unacknow-

ledged and prejudicial transformations of copyright works may harm an author's

financial interests if the public erroneously believe that they reflect poor aesthetic

judgment on the author's part.126 This fear prompted NewYork to prohibit exhi-

bitions of altered works which harm authors' reputations.127 Complete destruc-

tion raises different considerations because destroyed works cease to exist and do

not mislead consumers into buying the work. Nevertheless, consumers and

authors alike may lack other examples which demonstrate the financial attractive-

ness of a particular author's expressions.128 In jurisdictions where the droit de suite is

recognised, authors of destroyed works are also deprived of resale royalties.129

Other problems also arise if the author himself makes serious alterations to his

earlier work and fails to inform the public about the changes. If the misrepresen-

tation is not exposed, the public may buy an adulterated work thereby harming

the consumer protection function of moral rights protection. This issue exposes

the dangers of allowing a self-interested individual to vindicate the public interest

in maintaining authentic cultural products. All these arguments must be recon-

ciled with the possibility that copyright owners may be reluctant to reduce the