Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Supreme Court Rules Domestic Contract Law Can Be Applied in International Cases

Uploaded by

Cury AsociadosCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Supreme Court Rules Domestic Contract Law Can Be Applied in International Cases

Uploaded by

Cury AsociadosCopyright:

Available Formats

October 09, 2020 DISPUTE RESOLUTION MAGAZINE

Supreme Court Rules

Domestic Contract

Law Can Be Applied in

International Cases

Lionel M. Schooler

Share this:

In Dispute involving New York Convention, US Supreme Court

Considers whether Domestic Contract Law Rules can be Applied in

International Cases

The US Supreme Court issued a major international construction

arbitration ruling this term in its much-anticipated decision in GE Energy

Power Conversion France SAS, Corp. v. Outokumpu Stainless

USA, LLC. Focusing its attention on the Convention on the Recognition

and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards of 1958 (the New

York Convention) for the first time since 2014, the Court decided an

unresolved procedural question pertaining to international arbitration

disputes: may a domestic court applying the Convention approve a non-

signatory’s motion to compel a signatory to arbitrate a dispute of

international scope arising under the applicable agreement? The Court

evaluated the terms of the Convention and decided that the answer was

yes.

Underlying agreement

In 2007, a predecessor to Outokumpu Stainless Steel, a US subsidiary of a

Finnish stainless-steel producer, signed an agreement with an

engineering company that, among other things, called for fabrication and

installation of cold rolling mill units to be used to manufacture stainless

steel at the steel-producer’s Alabama plant. The agreement contained a

list of mandatory subcontractors to be used, including GE Power

Conversion France SAS, a French subsidiary of General Electric (GE

Energy). It also required arbitration of any disputes pertaining to contract

performance to be conducted in Dusseldorf, Germany, under German

law, utilizing the Arbitration Rules of the International Chamber of

Commerce. The plant owner and the engineering firm were the only

signatories to the agreement.

Not a member of the ABA's Section of Dispute

Resolution? Join now to view premium content.

Subcontractor agreement

The engineering firm then entered into a subcontract agreement with the

designated subcontractors, one of whom was GE Energy. This

subcontract called for GE Energy to manufacture and install nine electric

motors to be used in the cold rolling units, which GE Energy delivered in a

timely manner. The subcontract did not contain an arbitration clause, and

GE Energy was not a signatory of any agreement between Outokumpu

Stainless or its predecessor and the engineer.

The rolling mills manufactured by GE Energy allegedly failed. Outokumpu

Stainless sued GE Energy in an Alabama state court over this failure,

alleging negligence and breach of warranty. GE Energy removed the case

to federal court, pursuant to the removal clause of the New York

Convention. Even though GE Energy had not been a party to and had not

signed any agreement containing an arbitration clause, it sought to

compel Outokumpu Stainless to arbitrate the dispute in the underlying

lawsuit on the basis of the common-law doctrine of equitable estoppel,

that is, on the theory that Outokumpu Stainless, as a signatory to a written

agreement containing an arbitration clause, was “equitably estopped”

from blocking an effort by a non-signatory to compel arbitration when

the signatory’s claim against the non-signatory relied upon the terms of

that agreement. GE Energy contended that this doctrine had long been

recognized as viably used in domestic arbitrations.

Ruling by the lower courts

Based upon the landmark Supreme Court decision in Mitsubishi Motors

Corp. v. Soler Chrysler-Plymouth, 1 courts of the United States are

authorized pursuant to the New York Convention to require arbitration in

disputes involving foreign parties. Since GE Energy was a foreign party, its

motion to compel was governed by the New York Convention rather than

by the “domestically focused” provisions of Chapter 1 of the Federal

Arbitration Act (FAA).

The United States District Court for the Southern District of Alabama

granted the motion to compel and dismissed the lawsuit, 2 finding that

there was an “agreement in writing” within the meaning of the

Convention’s Article II 3 based on the existence of the requisite written

agreement between Outokumpu Stainless and the engineer that specified

GE Energy as an approved/required subcontractor and the

corresponding status of GE Energy as suitably identified within the

arbitration contract’s definitions of “Buyer” and “Seller.”

The United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit reversed this

decision and rejected GE Energy’s effort to invoke arbitration. The

Eleventh Circuit acknowledged the propriety of invoking the equitable

estoppel doctrine in domestic arbitrations, citing Arthur Andersen LLP v.

Carlisle. 4 However, it construed that decision as endorsing equitable

estoppel in a domestic arbitration only because Chapter 1 of the FAA 5

does not expressly restrict arbitration to the signatories to an agreement.

It accordingly ruled that such a restriction existed in the New York

Convention, with the result that only a party to an arbitration agreement

could invoke the arbitral process. Since GE Energy lacked this status as a

non-signatory, the Eleventh Circuit concluded that GE Energy could not

rely upon Alabama equitable estoppel principles to override the New

York Convention’s signatory requirement. 6

Supreme Court review

The Supreme Court granted certiorari and unanimously reversed the

Eleventh Circuit’s ruling. The Court held that the New York Convention

does not conflict with or bar a non-signatory’s invocation of domestic

equitable estoppel doctrines to compel arbitration by a signatory.

Equitable estoppel in domestic arbitrations

Referring to its earlier decision in Arthur Andersen, 7 the Court noted

that in domestic arbitrations, the FAA does not bar the application of

underlying state contract law principles that include doctrines, such as

equitable estoppel, authorizing contract enforcement by a non-signatory.

It then characterized the scope of equitable estoppel in the arbitration

context as “allow[ing] a nonsignatory to a written agreement containing

an arbitration clause to compel arbitration where a signatory to the

written agreement must rely on the terms of that agreement in asserting

its claims against the nonsignatory.” 8

Equitable estoppel under the New York

Convention

Turning to a consideration of the New York Convention, which the Court

characterized as a “multilateral treaty addressing international

arbitration” that focuses “almost entirely on arbitral awards,” the Court

noted that ordinary tools of treaty interpretation governed analysis of the

impact of the Convention on the question presented.

Applying such tools, the Court held that only one Article in the

Convention, Article II, even addresses arbitration agreements and, further,

that the Convention does not address at all the potential role of a non-

signatory in attempting to enforce an arbitration agreement. It construed

this “silence” to support dispositively the use of the “domestic” doctrine of

equitable estoppel in an international arbitration case. It held that nothing

in the Convention’s text excludes application of such a doctrine or

displaces application of domestic doctrines. It accordingly ruled that a

state law equitable estoppel doctrine does not conflict with §208 of the

Convention. 9

To bolster its decision, the Court took into consideration the drafting

history of the Convention. It found little guidance from the treaty’s choice

of language in Article II, noting only that “the drafters sought to impose

baseline requirements on contracting states.” 10 It specifically stated

that “nothing in the drafting history suggests that the Convention sought

to prevent contracting states from applying domestic law that permits

non-signatories to enforce arbitration agreements in additional

circumstances.” 11

Result of the decision: remand to court of

appeals

The Court concluded by noting that the Eleventh Circuit had not

determined whether GE Energy could compel arbitration using the

equitable estoppel doctrine, and that as a result, the Court of Appeals

could address this issue on remand. The case therefore returns to that

court for a consideration of Alabama’s doctrinal law.

Concurrence

In a concurring opinion, Justice Sonia Sotomayor focused upon what she

characterized as the “foundational” principle of “consent to arbitrate.” 12

She invoked the Court’s 2010 decision in Stolt Nielsen SA v. AnimalFeeds

International Corp. 13 as support for the basic precept that arbitration

is a matter of consent, not coercion. She utilized this precept as a

springboard to the broader point that there is no one version of

“equitable estoppel” and accordingly no explicit demonstration that the

use of the doctrine automatically reflects consent to arbitrate. She thus

forecast that lower courts would have to determine whether application

of a domestic non-signatory doctrine would comport with the FAA’s

consent restriction. 14

Aftermath

As with many US Supreme Court decisions, the ruling in GE Energy does

not conclude this particular battle over arbitrability. The parties return to

Atlanta to have the Eleventh Circuit (or the District Court in Alabama)

determine the proper application of Alabama’s equitable estoppel

doctrine.

This dispute’s international nature is important. Although GE Energy

performed its contractual obligations in Alabama and Outokumpu

Stainless filed suit over such performance in Alabama, the underlying

contracts do not mention Alabama as the appropriate site for resolution

of this dispute, and they do not designate Alabama law as the substantive

law governing resolution of the dispute. Rather, the agreement in

question calls for arbitration that is governed by the procedural and

substantive law of Germany, with an arbitration to be conducted in

Dusseldorf.

On remand, therefore, a domestic court will assess whether GE Energy

can legitimately invoke Alabama’s equitable estoppel doctrine to compel

Outokumpu Stainless to arbitrate. If Outokumpu Stainless is compelled to

arbitrate its dispute with GE Energy, the terms of the applicable

agreement will present to an arbitral tribunal in Germany the need to

consider the extent to which GE Energy can present its claims and

defenses through invocation of the doctrine of equitable estoppel. 15

The GE Energy v. Outokumpu Stainless decision marks the first foray of

the Supreme Court into a consideration of whether domestic contractual

law principles frequently invoked in domestic arbitrations can

correspondingly be applied in international cases. The Court

unanimously supports such an application in this case, empowering non-

signatories in appropriate circumstances to take advantage of the arbitral

process to resolve complex international construction and business

disputes.

Going forward, courts confronted with motions to compel arbitration

similar to the one submitted by GE Energy in this case will probably have

to scrutinize the extent to which there is an appropriate equitable

estoppel doctrine to apply and, if so, the breadth of that doctrine’s scope.

The GE Energy decision also highlights the challenges confronting

construction law practitioners seeking to devise an efficient and effective

system of dispute resolution essential to maintaining the orderly process

of construction in large international projects.

On one hand, a party to such a dispute may want to avoid massive

arbitration proceedings involving multiple project participants. Taking

such an approach may require creative ways to restrict participation in

dispute resolution proceedings. On the other hand, considering all the

many potential participants in a project – such as subcontractors,

distributors, vendors, guarantors and customers – a client might prefer to

control venue and applicable law of a dispute through an all-

encompassing arbitration clause, even if this results in numerous parties

being compelled to join the proceeding.

Download the PDF

Want more personalized content? Tell us your

interests.

ENTIT Y:

SECTION OF DISPUTE RESOLUTION

TOPIC:

ALTERNATIVE DISPUTE RESOLUTION, CONSTRUCTION

Endnotes

Authors

American Bar Association |

/content/aba-cms-dotorg/en/groups/dispute_resolution/publications/dispute_resolution_magazine/2020/dr-magazine-construction-conflicts/supreme-court-rules-domestic-contract-law-can-

be-applied-in-international-cases

You might also like

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Development and Nation-BuildingDocument8 pagesDevelopment and Nation-BuildingCury AsociadosNo ratings yet

- Pac Rim v. El Salvador - Investment Dispute Settlement Navigator - UNCTAD Investment Policy HubDocument1 pagePac Rim v. El Salvador - Investment Dispute Settlement Navigator - UNCTAD Investment Policy HubCury AsociadosNo ratings yet

- Quadrant Pacific v. Costa Rica - Investment Dispute Settlement Navigator - UNCTAD Investment PolicyDocument1 pageQuadrant Pacific v. Costa Rica - Investment Dispute Settlement Navigator - UNCTAD Investment PolicyCury AsociadosNo ratings yet

- TFM 2020 Schroff JasminaDocument94 pagesTFM 2020 Schroff JasminaCury AsociadosNo ratings yet

- Shell v. Nigeria - Investment Dispute Settlement Navigator - UNCTAD Investment Policy HubDocument1 pageShell v. Nigeria - Investment Dispute Settlement Navigator - UNCTAD Investment Policy HubCury AsociadosNo ratings yet

- Perenco v. Ecuador - Investment Dispute Settlement Navigator - UNCTAD Investment Policy HubDocument9 pagesPerenco v. Ecuador - Investment Dispute Settlement Navigator - UNCTAD Investment Policy HubCury AsociadosNo ratings yet

- Panel - Rio Doce Panel - IUCNDocument3 pagesPanel - Rio Doce Panel - IUCNCury AsociadosNo ratings yet

- US Court Cancels Most of Class Action Against Samarco Over Deadly Dam BurstDocument7 pagesUS Court Cancels Most of Class Action Against Samarco Over Deadly Dam BurstCury AsociadosNo ratings yet

- Chevron and TexPet v. Ecuador (I) - Investment Dispute Settlement Navigator - UNCTAD Investment PoliDocument1 pageChevron and TexPet v. Ecuador (I) - Investment Dispute Settlement Navigator - UNCTAD Investment PoliCury AsociadosNo ratings yet

- Hybrid PeaceLab SolutionsDocument2 pagesHybrid PeaceLab SolutionsCury AsociadosNo ratings yet

- Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Petroleum - A Practitioner's ViewpointDocument15 pagesKiobel v. Royal Dutch Petroleum - A Practitioner's ViewpointCury AsociadosNo ratings yet

- UK: BHP Faces 5bn Lawsuit Over Samarco Dam Collapse - Business & Human Rights Resource CentreDocument4 pagesUK: BHP Faces 5bn Lawsuit Over Samarco Dam Collapse - Business & Human Rights Resource CentreCury AsociadosNo ratings yet

- Wai The Global Elite in Press PDFDocument57 pagesWai The Global Elite in Press PDFNicolás GoldmanNo ratings yet

- Kerr-McGee - Tronox, Inc - PHA - Final - 06-12-2014Document174 pagesKerr-McGee - Tronox, Inc - PHA - Final - 06-12-2014Cury AsociadosNo ratings yet

- Uranium Resources in New MexicoDocument13 pagesUranium Resources in New MexicoCury AsociadosNo ratings yet

- Muir Watt (2011) Private International Law As Global Governance - Beyond The Schize, From Closet To PlanetDocument55 pagesMuir Watt (2011) Private International Law As Global Governance - Beyond The Schize, From Closet To PlanetCury AsociadosNo ratings yet

- Adair - Nezhyvenko - 2017 - Ethics&Economics - The Market For Prostitution in The EUDocument22 pagesAdair - Nezhyvenko - 2017 - Ethics&Economics - The Market For Prostitution in The EUCury AsociadosNo ratings yet

- 150710summaryDocument11 pages150710summaryCury AsociadosNo ratings yet

- WWW - Remep.mpg - de Files Events 201310121 Final ProgrammeDocument3 pagesWWW - Remep.mpg - de Files Events 201310121 Final ProgrammeCury AsociadosNo ratings yet

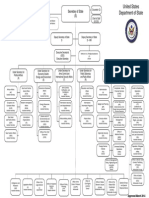

- Chart United States Department of States (USDOS)Document1 pageChart United States Department of States (USDOS)Cury AsociadosNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- DFA v. FalconDocument4 pagesDFA v. FalconLeia VeracruzNo ratings yet

- Code of Civil Procedure Important Orders and Sectons With CasesDocument22 pagesCode of Civil Procedure Important Orders and Sectons With CasesAlina RizviNo ratings yet

- ADR Mechanisms for Beauty Salon Partnership DisputeDocument3 pagesADR Mechanisms for Beauty Salon Partnership DisputeEkemini JonahNo ratings yet

- ABS-CBN v. World Interactive Network Systems (WINS) : G .R. NO - 169332 FEBRU A RY 11, 2008Document9 pagesABS-CBN v. World Interactive Network Systems (WINS) : G .R. NO - 169332 FEBRU A RY 11, 2008Jerahmeel CuevasNo ratings yet

- Epr Fellow ArbitrationDocument5 pagesEpr Fellow ArbitrationPost Your FeedbackNo ratings yet

- BA5015-Industrial Relations and Labor WelfareDocument19 pagesBA5015-Industrial Relations and Labor WelfareYamini AshleyNo ratings yet

- Labor Relations Final Exam 2020Document6 pagesLabor Relations Final Exam 2020Vanessa May GaNo ratings yet

- Construction of affordable housing units in MaldivesDocument12 pagesConstruction of affordable housing units in Maldivesabhishek pathakNo ratings yet

- IBT Local 391 and Johnson Controls 5-2-03Document23 pagesIBT Local 391 and Johnson Controls 5-2-03E Frank CorneliusNo ratings yet

- SyllabusDocument4 pagesSyllabusEiron AlmeronNo ratings yet

- Conciliation Proceedings Under The Arbitration Conciliation ActDocument5 pagesConciliation Proceedings Under The Arbitration Conciliation ActGarima AgrawalNo ratings yet

- KpjohnyDocument135 pagesKpjohnyVikash KumarNo ratings yet

- Please Read Carefully, Sign and Return To NIKEDocument3 pagesPlease Read Carefully, Sign and Return To NIKEChirag RokadeNo ratings yet

- Private Car Insurance Policy Wording - Liberty VideoconDocument11 pagesPrivate Car Insurance Policy Wording - Liberty VideoconLiberty General InsuranceNo ratings yet

- RetainershipDocument2 pagesRetainershipCoy Resurreccion Camarse100% (1)

- Project On Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 - Arbitral AwardDocument17 pagesProject On Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 - Arbitral AwardRvi MahayNo ratings yet

- Extra Space Storage LeAseDocument13 pagesExtra Space Storage LeAsemeganlabri100% (1)

- Techno Commercial Offer NDPL ETC HT PANELS 33kVDocument7 pagesTechno Commercial Offer NDPL ETC HT PANELS 33kVNavjot DhillonNo ratings yet

- Intercopac v. Lear 25 - Reply in Support of Motion To Compel ArbitrationDocument122 pagesIntercopac v. Lear 25 - Reply in Support of Motion To Compel ArbitrationLuke GilmanNo ratings yet

- Willow Creek Stables Boarding AgreementDocument8 pagesWillow Creek Stables Boarding Agreementapi-294938091No ratings yet

- Real Vs Sangu Philippines, IncDocument8 pagesReal Vs Sangu Philippines, IncRomy IanNo ratings yet

- Case Sonza V Abs-Cbn DigestDocument3 pagesCase Sonza V Abs-Cbn DigestKym AlgarmeNo ratings yet

- ADR in Business: Med-Arb and Arb-Med IssuesDocument19 pagesADR in Business: Med-Arb and Arb-Med IssuesLan LinhNo ratings yet

- Continental Micronesia, Inc. vs. Basso PDFDocument4 pagesContinental Micronesia, Inc. vs. Basso PDFJona CalibusoNo ratings yet

- UDA Land V Bisraya Construction (2015) 5 CLJ 527Document75 pagesUDA Land V Bisraya Construction (2015) 5 CLJ 527Kai JunNo ratings yet

- Labour LawDocument29 pagesLabour LawTanu PriyaNo ratings yet

- Mediation Training ManualDocument164 pagesMediation Training Manualmithun7100% (4)

- Synopsis On Memoradum of UnderstandingDocument2 pagesSynopsis On Memoradum of UnderstandingAarush ChaturvediNo ratings yet

- Kanlaon Vs NLRCDocument3 pagesKanlaon Vs NLRCJade Belen Zaragoza0% (2)

- Ltia Form 01-Performance Evaluation FormDocument30 pagesLtia Form 01-Performance Evaluation FormBarangay PangilNo ratings yet