Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Celtic Calendar and The Anglo Saxon

The Celtic Calendar and The Anglo Saxon

Uploaded by

stefanobalestra75Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Celtic Calendar and The Anglo Saxon

The Celtic Calendar and The Anglo Saxon

Uploaded by

stefanobalestra75Copyright:

Available Formats

The Celtic Calendar

and the Anglo-Saxon Year

In recent years the origins of the English traditional year have been widely

debated. If the festivals were not derived from Celtic or Roman traditions, what

was their source? Richard Sermon argues the Anglo-Saxon case.

E

NGLAND HAS A RICH TRADITION OF CALENDAR subject (Sermon, 2000, 401-420), this essay seeks

customs and festivals, which include Yule, to review the linguistic evidence, and use the

Lent, Easter, May Day, Midsummer, results to suggest an alternative basis for the

Harvest and Halloween, as well as a host of local English traditional year.

minor festivals. The majority of published refer-

ences on English folk tradition tend to attribute The Celtic Calendar

either Roman or Celtic origins to these annual The native languages of Britain and Ireland

events. For example, Yule is often identified with descend from two branches of the Indo-European

the Roman Saturnalia, and May Day with family, Celtic and Germanic. The Celts (Kåëôïé)

Floralia. However, it is the Celtic calendar that is are first recorded in the 5th century BC by the

most often used to explain the origins of the Greek historian Herodotus, who locates them in

English traditional year. A study of the ritual year the area of the upper Danube (Selincourt, 1954,

by Ronald Hutton of Bristol University (Hutton, 142). Later Roman historians referred to a number

1996), has involved a thorough re-examination of of peoples within their empire as being either Celts

the historical records, and has largely discredited or Gauls. In the 19th century archaeologists

the concept of the Celtic calendar. However, attempted to find evidence of these early Celts in

Hutton does not fully explore the Anglo-Saxon central Europe, and identified two possible

evidence. Following an earlier paper on the same cultures named after the locations in which they

Table 1. Old Irish Festivals

Old Irish Manx Gaelic Scots Gaelic Irish Interpretation

Imbolc - - - Ewes milking

Beltane Boaldyn Bealltainn Bealtaine Bright fire

Lúgnasad Luanistyn Lùnasdal Lúnasa Lug's festival

Samain Sauin Samhainn Samhna Summer end

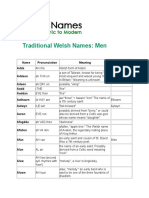

Table 2. Modern Celtic Month Names

Welsh Cornish Scots Gaelic Irish Equivalent

Ionawr Genver Faoilteach Eanáir January

Chwefror Whever Gearran Feabhra February

Mawrth Merth Màrt Márta March

Ebrill Ebrel Giblean Aibreán April

Mai Me Céitean Bealtaine May

Mehefin Metheven Òg-mhios Meitheamh June

Gorffennaf Gortheren Iuchar Iúil July

Awst Est Lùnasdal Lúnasa August

Medi Gwyngala Sultainn Meám Fhómhair September

Hydref Hedra Damhar Deireadh Fhómhair October

Tachwedd Du Samhainn Samhna November

Rhagfyr Kevardhu Dùdlachd Nollag December

page 32 3rd Stone 43

Table 3: Coligny Calendar Months

Coligny Reconstruction Equivalent? Interpretation

SAMON Samonios Oct / Nov Summer end / Seed time

DVMAN Dumannios Nov / Dec Dark time

RIVROS Riuros Dec / Jan Frost time

ANAGAN Anagantios Jan / Feb Home time

OGRON Ogronios Feb / Mar Cold time

CVTIOS Cutios Mar / Apr Wind time

GIAMON Giamonios Apr / May Winter end / Shoots time

SIMIVIS Simivisonnos May / Jun Light time

EQVOS Equos Jun / Jul Horse time

ELEMBIV Elembiuios Jul / Aug Harvest time

AEDRINI Aedrinios Aug / Sep Hot time

CANTLOS Cantlos Sep / Oct Song time

were first discovered, Hallstatt and La Tène In 1897 an important discovery was made

(Renfrew, 1987, 211-249). However, the Celtic at Coligny near Lyons in France, when numerous

language group was only defined by that name at fragments of a bronze Gaulish calendar were

the beginning of the 18th century by Edward found, dating to the 2nd century AD. The calendar

Lhuyd, then curator of the Ashmolean Museum in consisted of 12 lunar months and two intercalary

Oxford (Lhuyd, 1707), and its relationship to these or leap months, however, the month names were

archaeological cultures is still a subject of much very different to those recorded in the other Celtic

debate (James, 1999). Nevertheless, at their languages, apart from Samonios which appears to

greatest extent, what we now call Celtic languages be cognate with the Old Irish festival Samain (see

were spoken throughout northern Italy, France, table 3).

Spain, Britain and Ireland. In the 19th century during the ‘Celtic

Revival’ these early Irish festivals were rediscov-

‘No man will travel this country,’ she said, ‘who ered by folklorists and academics such as Sir

hasn’t gone sleepless from Samain, when the James Frazer, who between 1890 and 1915

summer goes to its rest, until Imbolc, when the ewes published a twelve volume study of magic and

are milked at spring’s beginning; from Imbolc to religion entitled The Golden Bough (Frazer, 1922).

Beltane at the summer’s beginning and from Beltane This and similar works attempted to reconstruct a

to Brón Trogain, earth's sorrowing autumn.’ pan-Celtic year, that was said to have existed not

only in Ireland and Scotland, but throughout

The above passage comes from the 10th to 11th Britain and the former Celtic speaking parts of

century collection of Irish heroic tales known as the Europe. This ‘Celtic Calendar’ was believed to

Ulster Cycle (Kinsella, 1970, 27). During the have included the winter and summer solstices,

wooing of Emer (Tochmarc Emire) by the hero and the spring and autumn equinoxes, as well as

Cúchulainn, he is required to sleep for a year before the four recorded festivals that marked the

she will agree to marry him. In describing the year changing seasons. In addition, it was thought that

Emer also provides the earliest reference to all four bonfires had been a central part of all these festi-

of the Irish pagan festivals that marked the changing vals, giving rise to the idea of the Fire Festivals

of the seasons. Three of these festival names have (Frazer, 1922, 609-641). The resulting calendar

survived in Irish, Manx and Scots Gaelic, as the (see figure 1 and table 4) has been used exten-

month names for May, August and November. sively since the 19th century to explain the origins

However, in later sources Brón Trogain is known by of various English folk customs and festivals

the name Lúgnasad (see tables 1 and 2). (MacNeill, 1960).

Table 4. Celtic Revival Calendar

Celtic Year Date Assumed Equivalent

Winter Solstice 21st December Yule

Imbolc 1st February Lent

Spring Equinox 21st March Easter

Beltane 1st May May Day

Summer Solstice 21st June Midsummer

Lúgnasad 1st August Lammas

Autumn Equinox 22nd September Harvest

Samain 1st November Halloween

3rd Stone 43 page 33

However, there a number of significant Alfred (871-899 AD) the Anglo-Saxons were

problems with this reconstructed calendar. Firstly, referring to themselves collectively as Englisc,

as pointed out by Ronald Hutton (1996, 408-411), after the Angles. However, the Celtic Britons and

while Imbolc, Beltane, Lúgnasad and Samain are Irish referred to them as Saxons, giving rise to the

found in the Goidelic branch of the Celtic Welsh Saeson and the Scots Gaelic Sasunnach.

language group (Irish, Manx and Scots Gaelic) While the nature of the Anglo-Saxon settlement is

they are not found in the Brithonic branch (Welsh, still hotly debated (folk migration versus dominant

Cornish and Breton), and are only assumed to have élite), they were the first to identify themselves as

been pan-Celtic festivals. Secondly, the early Irish being English.

texts do not mention festivals on the solstices or The earliest description of the English

equinoxes, hence the lack of Old Irish names for year is given by Bede in 725 AD, who in a text on

these. Thirdly, these festivals, which were not the church calendar, De Temporum Ratione, also

necessarily observed by the Celtic Britons, are described the Anglo-Saxon pagan year (Jones,

then assumed to have passed into English folk 1976, chapter 15). The year started at Yule (Giuli)

tradition. Still, the concept of the ‘Celtic Calendar’ in the middle of winter, and was preceded by a

is now so deeply imbedded in both popular and festival known as Mothers Night (Modra Nect).

academic belief, that it is repeated throughout the Half way through the year was the festival Litha

literature on Celtic culture, history and archae- (Li∂a) in the middle of summer. The year

ology, but with no reference back to original consisted of 12 lunar months which approximated

source material. So much so, that many eminent to those of the Julian calendar (see table 5). Bede

archaeologists and historians have reproduced the also described what he thought to be the origins of

calendar in their various works, in particular Nora the month names. Yule was not only the name for

Chadwick, Lloyd Laing and Graham Webster, and the middle of winter but also the months before

more recently Barry Cunlifffe at Oxford and after the festival. Next came the month of mud

University (Cunliffe, 1997, 188-190). (sol) when cakes were offered to the gods. The

Nevertheless, in Hutton’s final conclusions (1996, following two months were named after the

408-411) he clearly demonstrates that the ‘Celtic Anglo-Saxon goddesses Hretha and Eostre, the

Year’ is in reality a modern scholastic construc- spring goddess. Then came the month when cattle

tion. had to be milked three times a day. The summer

festival Litha, like Yule, was flanked by two

The Anglo-Saxon Year months bearing the same name. Weed-month was

The Angles or Angli are first recorded in 98 AD, simply the time when weeds grew most, and Holy-

when the Roman historian Tacitus describes them month when offerings were made to the gods.

in his study of the Germanic peoples the Germania Finally came the month of the first winter full

(Mattingly, 1970, 134-5). Tacitus locates the Angli moon, and the month of blood when animals were

in what is now the border area between Germany slaughtered or sacrificed.

and Denmark, part of which still bears the name Bede goes on to explain that the pagan

Angeln. In the 5th century AD the Anglo-Saxons English year was divided into just two seasons,

(Angles, Saxons and Jutes) began to leave their winter and summer. The earliest references to Lent

homelands in north Germany and Denmark, and and Harvest occur in 9th century texts, Lent being

settle in lowland Britain following the collapse of the season when the days began to lengthen and

Roman rule. Their arrival and settlement in Britain Harvest when the crops were gathered in (see table

is described by the Northumbrian cleric Bede in 6). In Byrhtfer∂’s Handboc (Kluge, 1885, 298-

731 AD (King, 1930, 68-74). By the reign of King 337), a scientific manual written in 1011 AD, all

Table 5. Anglo-Saxon Months

Bede Anglo-Saxon Translation Equivalent

Giuli Æfterra Geola Later Yule January

Solmona∂ Solmona∂ Sol-month February

Hre∂mona∂ Hre∂mona∂ Hreth-month March

Eosturmona∂ Eastermona∂ Easter-month April

Îrimilchi Îrimilce Three-milkings May

Li∂a Ærra Li∂a Earlier Litha June

Li∂a Æfterra Li∂a Later Litha July

Weodmona∂ Weodmona∂ Weed-month August

Halegmona∂ Haligmona∂ Holy-month September

Winterfille∂ Winterfylle∂ Winter-full October

Blodmona∂ Blotmona∂ Blood-month November

Giuli Ærra Geola Earlier Yule December

page 34 3rd Stone 43

Table 6. Anglo-Saxon Seasons, Solstices and Equinoxes

Anglo-Saxon Translation Equivalent

Lencten Lent Spring

Sumor Summer Summer

Hærfest Harvest Autumn

Winter Winter Winter

Lenctenlice Emnihte Lenten Even-night Spring Equinox

Middansumor Midsummer Summer Solstice

Hærfestlice Emnihte Harvest Even-night Autumn Equinox

Middanwinter Midwinter Winter Solstice

four seasons are described as †a fower timan... From this brief survey of the original

lengten, sumor, hærfest & winter. The earliest sources we have been able to establish the Anglo-

references to Midwinter and Midsummer also Saxon (Old English) names for the months,

occur in 9th century texts, while the autumn seasons, solstices and equinoxes (see figure 2).

equinox is first recorded in a charter of Bishop Many of these names have survived into modern

Denewulf in 902 AD (Kemble, 1839-48, 151) English as Yule, Lent, Easter, Summer,

where it appears as hæfestes emnihte. Byrhtfer∂’s Midsummer, Harvest, Winter and Midwinter, and

Handboc also describes the relationship between are found throughout the Germanic language

the seasons, solstices and equinoxes, and clearly group (see table 7). Such broad agreement among

interprets the Latin word solstice as Midsummer; the Germanic languages, when compared with the

†æt ys on lyden solstitium & on englisc midsumor. Celtic languages, would suggest that a common

In about the 3rd century AD when year is more likely to have existed in the Germanic

Germanic soldiers are known to have been rather than Celtic speaking parts of Europe. It

recruited by the Roman Legions, various would also suggest that these Germanic season

Germanic tribes began to adopt the Roman seven and festival names, like the days of the week,

day week (Turville-Petre, 1964, 101) with its days arrived in Britain with the Anglo-Saxon settlers in

named after the planets. Saturday, Sunday and the 5th century AD.

Monday were named after the same planets as

their Latin equivalents, while Tuesday, Yule and Easter

Wednesday, Thursday and Friday were named In his chapter on the origins of Christmas, Ronald

after the Germanic gods Tiw, Woden, Thunor and Hutton relies on the work of Alexander Tille

Frig. When the Anglo-Saxons began to settle in (1889, Yule and Christmas, 147-149) and suggests

lowland Britain during the 5th century AD, they that Bede had only sketchy knowledge of the prac-

brought their week with them. These names have tices which he described. He argues that ‘Mothers

survived down through the centuries and are found Night’ could in fact refer to the Virgin Mary and

throughout the Germanic language group. the Nativity, and that it was not until the 11th

Table 7. Common Germanic Season and Festival Names

English Low Saxon Dutch German Swedish

Yule - Joelfeest Julfest Jul

Lent - Lente Lenz Vår

Easter Oostern - Ostern -

Summer Sommer Zomer Sommer Sommar

Midsummer Midsommer Midzomer Mittsommer Midsommar

Harvest Harvst Herfst Herbst Höst

Winter Winter Winter Winter Vinter

Midwinter Midwinter Midwinter Mittwinter Midvinter

Old English Old Frisian Middle Dutch Old High German Old Norse

Geola - - - Jól

Lencten - Lentin Lengizin Vár

Eastron Asteron - Ostarun -

Sumor Sumur Somer Sumar Sumar

Middansumor Middesumur Midsomer Mittesumar Mi∂rsumar

Hærfest Herfst Herfst Herbist Haust

Winter Winter Winter Wintar Vetr

Middanwinter Middewinter Midwinter Mittewintar Mi∂rvetr

3rd Stone 43 page 35

century that "Danish rule over England resulted in names Giuli and Eosturmonath... The first piece of

the introduction of the colloquial Scandinavian evidence comes from a church calendar fragment

term for Christmas, Yule" (Hutton, 1996, 6). written in Gothic, an extinct East Germanic

Hutton also doubts Bede’s interpretation of Eostre language. The Gothic Calendar Fragment (Snæ∂al,

as the spring goddess, and suggests that it may be 1999) comprises only one page of an estimated

the opening or beginning month, as the name is original nine, and is generally dated to the begin-

cognate with the East and the dawn sky (Hutton, ning of the 6th century AD. The surviving page

1996, 180). However, it is important to note that records a number of saint’s days and covers the

although Yule is cognate with the Old Norse end of October and the whole of November

festival Jól and winter month filir, Bede was (Naubaimbair), which is given Gothic name fruma

writing about the Anglo-Saxon pagan year in the Jiuleis meaning ‘earlier’ Jiuleis. This would

early 8th century AD, well before any Danish suggest the existence of a ‘later’ Jiuleis, and there-

settlement began in England. While Bede may fore appears to be cognate with Bede’s two months

have been speculating about the origins of the named Giuli. The second piece of evidence comes

pagan months and festivals, he was primarily from the reign of Charlemagne (742 to 814 AD)

concerned with religious matters, in particular the king of the Franks and founder of the Holy Roman

history of the English conversion to Christianity. It Empire. In Einhard’s Vita Caroli Magni (Turner,

therefore seems inconceivable that Bede would 1880, 29) he describes how Charlemagne defeated

have invented an origin for the name the continental Saxons and converted them to

Eosturmonath based on a pagan goddess called Christianity, and how as part of his reforms

Eostre, if he were not fairly convinced of this. In Charlemagne gave new Germanic names to the

any event, Bede was in no doubt as to the actual Latin months of the year, many of which survived

month names, and provides our earliest record of into early modern German (see table 8). How far

Yule and Easter (Jones, 1976 and Wallis 1999, these month names were completely new, or based

chapter 15): on earlier pre-Christian names is difficult to say.

Nevertheless, Charlemagne’s Ostarmanoth is

Menses Giuli a conversione solis in auctum diei, clearly cognate with Bede’s Eosturmonath.

quia unus eorum præcedit, alius subsequitur, In 601 AD Pope Gregory the Great

nomina accipiunt... Eosturmonath, qui nunc advised Augustine, his missionary in England, to

pascalis mensis interpretur, quondam a dea rededicate pagan temples to Christian saints and

illorum quae Eostre vocabatur et cui in illo festa martyrs, and to adopt a step by step approach in

celebrabant nomen habuit. the conversion of the English (King 1930, 160-

165). This may explain why in England the church

‘The months of Giuli derive their name from the borrowed the name for Easter from the native

day when the Sun turns back and begins to language, rather than using the Latin name Pascha

increase, because one of these months precedes as in the Welsh Pasg.

this day and the other follows... Eosturmonath has

a name which is now translated “Paschal month”, Ostern and Ostara

and which was once called after a goddess of The origin of the word Easter has also been the

theirs named Eostre, in whose honour feasts were subject of much debate in Germany, ever since the

celebrated in that month.’ mid 19th century when Jacob Grimm (Stallybrass,

1882, 10-11) first proposed that the German equiv-

Furthermore, we have continental alents Ostern and Ostermonat must have derived

evidence that appears to corroborate Bede’s month from the same goddess as Bede’s Eostre. Grimm

Table 8: Charlemagne’s Month Names

Frankish Interpretation Modern German Equivalent

Wintarmanoth Winter-month Eismonat January

Hornung Bastard-month? Hornung February

Lenzinmanoth Spring-month Lenzemonat March

Ostarmanoth Easter-month Ostermonat April

Winnemanoth Pasture-month Wonnemonat May

Brachmanoth Plough-month Brachmonat June

Hewimanoth Hay-month Heumonat July

Aranmanoth Harvest-month Erntemonat August

Witumanoth Wood-month Herbstmonat September

Windumemanoth Wine-month Weinmonat October

Herbistmanoth Autumn-month Wintermonat November

Heilagmanoth Holy-month Julmonat December

page 36 3rd Stone 43

reconstructed the goddess’ name in German as out that baptism was the central event of the Paschal

‘Ostara’ and pointed out that the name is cognate celebration in the first centuries AD, and argues that

with the East and the dawn sky; he therefore Ostern occurs in the plural form because it reflects

concluded that Eostre/Ostara must have been the the threefold baptism of the Holy Trinity. However,

goddess of the radiant dawn (göttin der morgen- if this were the case why is a version of Ostern not

röte). While many now dismiss this as 19th century found among the North Germanic languages

romanticism, we should perhaps bear in mind that (Danish/Norwegian Påske and Swedish Påsk)?

similar goddesses are recorded in other Indo- Alternatively, there may be more direct

European cultures. For example, the classical route by which Ostern could have entered the

goddess of the dawn (Greek Eos and Roman German language. Much of Frisia and Germany

Aurora) arose each morning in the East on her was converted to Christianity by Anglo-Saxon

chariot to announce the arrival of her brother the clerics such as St Clement (Willibrord, 658-739

Sun God (Greek Helios and Roman Sol). AD) and St Boniface (Wynfrith, c. 673-754 AD).

The first serious challenge to Grimm’s These clerics spoke a broadly the same language as

interpretation proposed that the origin of the word those they were seeking to convert, and given the

was all the result of a mistranslation (Knoblech, date of Bede’s De Temporum Ratione (725 AD)

1959, 27-45). In the early church the week may have been celebrating Easter by that name

following Easter was known in Latin as hebdomada during the course of their missionary work. This

in albis (white week) and sometimes simply as would explain why the name Easter is found in Old

albae, because the newly baptised Christians would English, Old Frisian and Old High German (see

wear their white baptismal robes during that week. table 7), but not in any of the North Germanic

Knoblech suggests that when albae was first inter- languages where versions of the Latin name Pascha

preted by German clerics it was mistaken for the are used. Furthermore, Willibrord and Wynfrith

Latin plural of alba meaning dawn, and therefore were later followed Alcuin (c. 735-804 AD) who

translated into the Old High German plural for was a leading figure in the court of Charlemagne.

dawn eostarun. However, given that Dominica in Alcuin was born in Northumbria and educated at

albis (white Sunday) which referred to the first York where he became well acquainted with the

Sunday after Easter was successfully translated into books in the cathedral library, in particular the

Middle Low German as Witsondach and Middle works of Bede. In 781 AD he met Charlemagne at

Dutch as Wittensondaugh. Why should there have Parma and was appointed master of the palace

been a problem translating hebdomada in albis school in Aachen. Here Alcuin is known to have

(white week) into German? built up a considerable library, which is likely to

More recently, Jürgen Udolph (1999) a have included a copy of Bede’s De Temporum

linguist at the University of Göttingen, has Ratione with its reference to Eosturmonath. It was

suggested that Ostern may be related to the North also under Alcuin that the Frankish historian

Germanic word ausa/austr meaning to draw or Einhard (770-840 AD) was to study, and later write

pour. A pagan form of baptism for naming newborn the Vita Caroli Magni with its reference to

children was known in Old Norse as vatni ausa Ostarmanoth. Therefore, when Charlemagne gave

(sprinkling with water). On this basis, Udolph this ‘new’ Germanic name to the month April he

suggests that name Ostern derives from a common could have been influenced by both his teacher

Germanic word for draw or pour, which was then Alcuin and Bede’s earlier work on time (Turner,

applied to the Christian act of baptism. He points 1880, 25):

Figure 1: The Celtic Revival Year Figure 2: The Anglo-Saxon Year

3rd Stone 43 page 37

Table 9: Latin Inscriptions from Morken-Harff

98 [M]atronis [...]cifnis [a]uvacsis [...]lia v(otum) s(olvit) l(ibens) m(erito)

99 Matronis Austriahenis M(arcus) Antonius Sentius p(ro) s(e) et s(uis) l(ibens) m(erito)

100 Matronis Austriahenabus Q(uintus) Atilius Gemellus v(otum) s(olvit) l(ibens) m(erito)

101 Austriahenis Juli(us) Jus[ti]nus Verinus Paterna ex imp(erio) ips(arum) l(ibens) m(erito)

102 M(arcus) Julius Vassileni f(ilius) Leubo Matr[o]nis Austriatium v(otum) s(olvit) m(erito)

103 Matronis Austriahenabus Q(uintus) Lucretius Patro(n) pro se v(otum) s(olvit) l(ibens) m(erito)

104 Matronis Austriahenis M(arcus) M(arius) Celsus ex imperio ipsarum s(olvit) l(ibens) m(erito)

105 Matronis Austriahen[a]bus T(itus) Quartio pro se et suis v(otum) s(olvit) l(ibens) m(erito)

106 Matronis [Au]striahenabus [...

‘Another deacon, Albin of Britain, surnamed Germanic would be cognate with Bede’s Eostre.

Alcuin, a man of Saxon extraction, who was the However, we must exercise caution. Just because

greatest scholar of the day, was his the two names appear be cognate does not prove

[Charlemagne’s] teacher in other branches of that the goddesses derived from a common origin,

learning. The King spent much time and labour it is equally possible for the two cults to have

with him studying rhetoric, dialectics, and espe- developed independently. Notwithstanding this,

cially astronomy; he learned to reckon, and used to the Morken-Harff inscriptions do provide impor-

investigate the motions of the heavenly bodies tant comparative evidence that should at least be

most curiously, with an intelligent scrutiny.’ mentioned in any discussion of Bede’s Eostre.

The Matronae Austriahenae Why the Celtic Calendar ?

One of the main criticisms levelled against Bede’s So far we have observed that a common year is

account of the goddess Eostre is that he provides more likely to have existed in the Germanic rather

our only reference to her. Nevertheless, a similar than Celtic speaking parts of Europe.

goddess name has been found on a group of Nevertheless, the ‘Celtic Calendar’ is still used to

Roman altar stones from the Lower Rhine area of explain the origins of many English calendar

north-west Germany, in what was the Roman customs. Moreover, two of the three festivals

province of Germania Inferior. These altars are which are most often claimed to be of Celtic origin

dedicated to native mother goddesses (Matrae or (May Day, Lammas and Halloween) are first

Matronae) who often occur as triple deities, and recorded in England. May games are first recorded

were thought to bestow fertility and protection on in 1244 when the Bishop of Lincoln, Robert

the people or region after which they were named. Grosseteste, complained of ludos quos vocant

Similar altars have been found throughout Inductionem Maii or ‘games which they call the

northern Italy, France, Spain and Britain, where Bringing in of May’ (Powicke and Cheney, 1964,

the goddesses often have Celtic names. However, 480). Lammas, literally meaning the ‘loaf-mass’,

in the Lower Rhine many of the goddesses appear is first recorded in King Alfred’s translation of

to have Germanic names, such as the Matribus Orosius in the 9th century AD; †æt on †ære tide

Suebi (Swabian Mothers) found on altar stones calendas Agustus & on †æm dæge †e we hata∂

from Cologne, and the Matronae Vacallinehae hlafmæsse (Early English Text Society, 1883, 8).

(Mothers of the Vacalli) who were worshipped at One of the earliest references to Halloween

the temple site of Pesch in the northern Eifel. mischief, as opposed to Hallowmas fires, is

In 1959 a number of Roman altar stones recorded in 1598 in John Stow’s The Survey of

dating to about 200 AD were discovered at London which describes These lords [of misrule]

Morken-Harff near Bedburg (Kolbe, 1960, 55ff beginning their rule on Alhollon eve (Wheatley,

and L’Année Epigraphique, 1962, 98-106), at least 1987, 89). So why do these claims of Celtic

eight of which were dedicated to native mother origins continue? The reason may have more to do

goddesses known as the Matronae Austriahenae with modern politics rather than ancient history, as

(see table 9). The Latin inscriptions are formulaic summarised by Jacqueline Simpson, Secretary of

with the goddesses’ name being followed by the the Folklore Society (Thorpe, 2001, XI):

name of the person making the dedication, and

then a series of standard phrases; pro se et suis (for ‘...in the twentieth century, the balance has been

himself and his family), ex imperio ipsarum (by upset by excessive reverence for a glamorised,

their command) and votum solvit libens merito idealised ‘Celtic tradition’, and a corresponding

(my vow fulfilled willingly and deservedly). widespread neglect of Germanic and Nordic lore.

Unfortunately none of the altar stones bear any There is, of course, a socio-political explanation

images of the goddesses, nevertheless their name for this: after two World Wars, and especially after

clearly contains from the root ‘Austri’ which if the gross exploitation of myth and heroic imagery

page 38 3rd Stone 43

by the Nazis, Germanic folklore carries a good Kinsella T, trans. 1970, The Tain, Oxford University

many unwelcome associations. But the time is ripe Press

now for a reassessment...’

Knoblech J, 1959, Der Ursprung von Neuhochdeutsch

Conclusions Ostern, Englisch Easter, Die Sprache, 5

The so called ‘Celtic Calendar’ has been used

extensively since the 19th century to explain the Kluge F, ed. 1885, Byrhtfer∂’s Handboc, Anglia, VIII

origins of various English folk customs and festi-

vals. However, recent research (Hutton, 1996, Kolbe H, 1960, Die neuen Matroneninschriften von

408-411) has concluded that this calendar is in Morken-Harff, Bonner Jahrbücher, 160

reality a modern scholastic construction.

Nevertheless, it is unfortunate that this research Lhuyd E, 1707, Archæologia Britannica, I

has not fully explored the Anglo-Saxon evidence.

These sources clearly demonstrate that Yule, Lent, MacNeill M, 1962, The Festival of Lughnasa, Oxford

Easter, Summer, Midsummer, Harvest, Winter and University Press

Midwinter, all derive from the language of the

Anglo-Saxons. Furthermore, these names are Mattingly H, trans. 1970, Tacitus, The Agricola and The

found throughout the Germanic language group, Germania, Penguin

including countries that have never been inhabited

by Celtic language speakers. This would suggest Powicke F and Cheney C, ed. 1964, Councils and

that the major divisions of the English traditional Synods, II, 1205-1313, Oxford

year are of Anglo-Saxon rather than Celtic origin.

While these survivals from the Anglo-Saxon year Renfrew C, 1987, Archaeology and Language, London

are not necessarily evidence of individual festivals

they do offer a more plausible basis for the English Selincourt A, trans. 1954, Herodotus, The Histories,

traditional year, and provide the fabric into which Penguin

later traditions, such as May Day, Lammas and

Halloween could have been woven. Future Sermon R, 2000, The Celtic Calendar and the English

research could usefully continue to re-examine Year, The Mankind Quarterly, XL, 4

received wisdom about the origins of English folk

customs and festivals, many of which are assumed Snæ∂al, M, 1999, A Concordance to Biblical Gothic, I,

to have Celtic origins but are not found in the University of Iceland Press

Celtic regions of Britain or Ireland. However, this

re-examination must be extended to include the Stallybrass J, trans. 1882, Jacob Grimm’s Teutonic

Anglo-Saxon and wider Germanic evidence. Mythology, London, I, 13

References Thorpe B, 2001, Northern Mythology, Wordsworth

Ed.itions

Cunliffe B, 1997, The Ancient Celts, Oxford University

Press Turner S, trans. 1880, Einhard, The Life of Charlemagne,

New York

Early English Text Society, ed. 1883, Ælfred., Orosius, V

Turville-Petre E, 1964, Myth and Religion of the North,

Frazer J, 1922, The Golden Bough, Wordsworth New York

Reference

Udolph J, 1999, Ostern, Geschichte eines Wortes,

Hutton R, 1996, The Stations of the Sun, Oxford Universitätsverlag C Winter, Heidelberg

University Press

Wallis F, trans. 1999, Bed.e, The Reckoning of Time,

James S, 1999, The Atlantic Celts, British Museum Press Liverpool University Press

Jones C, ed. 1976, Bed.e, De Temporum Ratione, XV Wheatley H, ed. 1987, John Stow, The Survey of London,

London

Kemble J, ed. 1839-48, Codex diplomaticus aevi

Saxonici, V Richard Sermon is Gloucester City Archaeologist,

and has a long standing interest in both historical

King J, ed. 1930, Bed.e, Historical Works, I, Leob linguistics and English folklore.

Classical Library

3rd Stone 43 page 39

You might also like

- Evidence Bible NT - Comfort, RayDocument2,733 pagesEvidence Bible NT - Comfort, RayDouglas Allen Hughes Sr96% (26)

- Dolmens of Ireland by William Borlase 1897 Vol IDocument366 pagesDolmens of Ireland by William Borlase 1897 Vol IuiscecatNo ratings yet

- The Welsh TriadsDocument36 pagesThe Welsh TriadsMarcelo WillianNo ratings yet

- Celtic Empire Peter Berresford EllisDocument183 pagesCeltic Empire Peter Berresford EllisSeamairTrébol100% (3)

- DruiddDocument151 pagesDruiddRodney Mackay100% (3)

- The Fairy Bride Legend in WalesDocument18 pagesThe Fairy Bride Legend in Walesavallonia9100% (3)

- Protogermanic Lexicon PDFDocument382 pagesProtogermanic Lexicon PDFPablo MartínezNo ratings yet

- Folkright Journal 1-Compressed PDFDocument87 pagesFolkright Journal 1-Compressed PDFaustin orme100% (1)

- Annual Festivals of Pagan ScandinaviaDocument32 pagesAnnual Festivals of Pagan ScandinaviaAndres MarianoNo ratings yet

- Burial Evidence About Early Saxon SocietyDocument10 pagesBurial Evidence About Early Saxon SocietyCanaffleNo ratings yet

- Sources For Myths: Lebor Na Huidre Book of LeinsterDocument9 pagesSources For Myths: Lebor Na Huidre Book of LeinsterG BikerNo ratings yet

- Donnchadh Ó Corráin - Viking Ireland - AfterthoughtsDocument26 pagesDonnchadh Ó Corráin - Viking Ireland - AfterthoughtssifracNo ratings yet

- Ogham Inscription 00 Fergu of TDocument186 pagesOgham Inscription 00 Fergu of TJose MarcioNo ratings yet

- DruidnDocument36 pagesDruidnRodney Mackay100% (2)

- The Anglo-Saxon Peace Weaving WarriorDocument64 pagesThe Anglo-Saxon Peace Weaving WarriorBarbara CernadasNo ratings yet

- The Religion of The Ancient CeltsDocument279 pagesThe Religion of The Ancient CeltsAlina Ghe100% (3)

- The First Charm of MakingDocument8 pagesThe First Charm of Makingapi-26210871100% (1)

- Fate of Children of Tuireann (1901)Document276 pagesFate of Children of Tuireann (1901)AaronJohnMayNo ratings yet

- Leabhar Nan Gleann: The Book of The Glens With Zimmer On Pictish MatriarchyDocument324 pagesLeabhar Nan Gleann: The Book of The Glens With Zimmer On Pictish Matriarchyoldenglishblog100% (1)

- Everything Means Something in Viking 2Document4 pagesEverything Means Something in Viking 2mark_schwartz_41No ratings yet

- Celtic Iron Age Sword Deposits and Arth PDFDocument7 pagesCeltic Iron Age Sword Deposits and Arth PDFAryaNo ratings yet

- Younger Edda 3 Old NorseDocument199 pagesYounger Edda 3 Old NorseOl Reb100% (1)

- Daithi O Hogain The Sacred IsleDocument5 pagesDaithi O Hogain The Sacred IsleScottNo ratings yet

- DruidxDocument11 pagesDruidxRodney Mackay100% (2)

- Crankitol LLPDocument10 pagesCrankitol LLPSushar MandalNo ratings yet

- Women As Peace WeaversDocument47 pagesWomen As Peace WeaversDumitru Ioan100% (1)

- Saga-Book, Vol. 33, 2009Document140 pagesSaga-Book, Vol. 33, 2009oldenglishblog100% (2)

- Charles Riseley - Ceremonial Drinking in The Viking AgeDocument47 pagesCharles Riseley - Ceremonial Drinking in The Viking AgeGabriel GomesNo ratings yet

- An Eye For Odin Divine Role-Playing in T PDFDocument22 pagesAn Eye For Odin Divine Role-Playing in T PDFBoppo GrimmsmaNo ratings yet

- Religious Practices of The Pre-Christian and Viking AgeDocument60 pagesReligious Practices of The Pre-Christian and Viking AgeAitziber Conesa MadinabeitiaNo ratings yet

- "The Celtic Kingdoms": Universitas Nasional Fakultas Bahasa Dan Sastra Prodi Sastra Inggris Jakarta 2019Document7 pages"The Celtic Kingdoms": Universitas Nasional Fakultas Bahasa Dan Sastra Prodi Sastra Inggris Jakarta 2019Gilang RafliNo ratings yet

- Lughnasadh Research PDFDocument2 pagesLughnasadh Research PDFLiving StoneNo ratings yet

- The Werewolf in Medieval Icelandic LiteratureDocument27 pagesThe Werewolf in Medieval Icelandic LiteratureMetasepiaNo ratings yet

- Vikings - Beverages & Drinking CustomsDocument16 pagesVikings - Beverages & Drinking CustomsJohnStitelyNo ratings yet

- Following A Fork in The Text: The Dagda As Briugu in Cath Maige TuiredDocument7 pagesFollowing A Fork in The Text: The Dagda As Briugu in Cath Maige TuiredincoldhellinthicketNo ratings yet

- Human Sacrifice in Viking Age Britain AnDocument18 pagesHuman Sacrifice in Viking Age Britain AncelalNo ratings yet

- Celtic Female NamesDocument6 pagesCeltic Female NamesBeki LokaNo ratings yet

- An Homage To The Ancestors: Institutionen För Arkeologi Och Antik HistoriaDocument55 pagesAn Homage To The Ancestors: Institutionen För Arkeologi Och Antik HistoriaStellaNo ratings yet

- Colquhoun GenealogyDocument14 pagesColquhoun GenealogyJeff MartinNo ratings yet

- Celtic Dialects - Gaelic, Brythonic. Pictish, and Some Stirlingshire Place-NamesDocument56 pagesCeltic Dialects - Gaelic, Brythonic. Pictish, and Some Stirlingshire Place-NamesGrant MacDonald100% (1)

- Traditional Welsh NamesDocument29 pagesTraditional Welsh NamesВук ДражићNo ratings yet

- Answer Key Old Norse Old Icelandic Concise Introduction Byock Gordon 210304Document40 pagesAnswer Key Old Norse Old Icelandic Concise Introduction Byock Gordon 210304abigarxes100% (1)

- Auraicept Na NÉncesDocument446 pagesAuraicept Na NÉncesAna Bantel (Slakkos Abonos)No ratings yet

- Gaelic Songs of Mary MacleodDocument189 pagesGaelic Songs of Mary MacleodAngeloNo ratings yet

- Leborgablare 00 MacauoftDocument600 pagesLeborgablare 00 MacauoftMilovan Filimonović100% (1)

- The Celtic Elements in The Lays of PDFDocument61 pagesThe Celtic Elements in The Lays of PDFVictor informatico100% (1)

- Conversion of The Vikings in IrelandDocument260 pagesConversion of The Vikings in IrelandPia Catalina Pedreros Yañez100% (1)

- Celtic Gods and GoddessessDocument42 pagesCeltic Gods and GoddessessGaly Valero100% (3)

- The Celtic Element in Irish IdentityDocument12 pagesThe Celtic Element in Irish IdentityNadezhda GeshanovaNo ratings yet

- DruidcDocument216 pagesDruidcRodney Mackay100% (3)

- The Annals of IrelandDocument257 pagesThe Annals of IrelandJody M McNamara100% (1)

- The Vikings in Orkney (Graham Campbell - Orkney, 2003, Pp. 128-137)Document10 pagesThe Vikings in Orkney (Graham Campbell - Orkney, 2003, Pp. 128-137)Vlad Alexandru100% (1)

- Welsh Tribal Law 01Document236 pagesWelsh Tribal Law 01Haruhi Suzumiya100% (1)

- Ancient Irish PoetryDocument140 pagesAncient Irish PoetryAndy100% (1)

- Thomas Rowsell - Woden and His Roles in Anglo-Saxon Royal GenealogyDocument24 pagesThomas Rowsell - Woden and His Roles in Anglo-Saxon Royal GenealogyVarious TingsNo ratings yet

- Asatru As A Religion PDFDocument17 pagesAsatru As A Religion PDFzelwiidNo ratings yet

- The Arrangement of the Class I Pictish Stones North of the River TayFrom EverandThe Arrangement of the Class I Pictish Stones North of the River TayNo ratings yet

- Modello FerriDocument4 pagesModello FerriOlga D'Andrea100% (1)

- IMSLP447196-PMLP727144-w F Bach Adagio e Fuga Re Minore Falk 65 Score 0 PDFDocument19 pagesIMSLP447196-PMLP727144-w F Bach Adagio e Fuga Re Minore Falk 65 Score 0 PDFOlga D'AndreaNo ratings yet

- Latin For Bird Lovers - Over 3,000 Bird Names Explored and Explained PDFDocument226 pagesLatin For Bird Lovers - Over 3,000 Bird Names Explored and Explained PDFOlga D'Andrea100% (1)

- Latin For Bird Lovers - Over 3,000 Bird Names Explored and Explained PDFDocument226 pagesLatin For Bird Lovers - Over 3,000 Bird Names Explored and Explained PDFOlga D'Andrea100% (1)

- What Is SalvationDocument3 pagesWhat Is SalvationZoro 2000No ratings yet

- Vajrapani Mahachakra Daily PracticeDocument12 pagesVajrapani Mahachakra Daily PracticeNilsonMarianoFilho100% (3)

- 6th Get To Know Me ActivityDocument11 pages6th Get To Know Me Activityadama61160No ratings yet

- Kanaga Mask: Symbolism Gallery References BibliographyDocument2 pagesKanaga Mask: Symbolism Gallery References BibliographyAlison_VicarNo ratings yet

- Liturgy of The Hours SFCDocument18 pagesLiturgy of The Hours SFCJose RizalNo ratings yet

- GMRCDocument79 pagesGMRCMarivelNo ratings yet

- CP December 2021Document70 pagesCP December 2021RFC MascarenhasNo ratings yet

- Tribal Leaders of Odisha (Odisha Review)Document8 pagesTribal Leaders of Odisha (Odisha Review)avengersthe708No ratings yet

- Diversity in IndiaDocument27 pagesDiversity in IndiaParzival2076No ratings yet

- Chapter 1 The Philosophical Perspective of The Self e ModuleDocument13 pagesChapter 1 The Philosophical Perspective of The Self e ModuleLois Alzette Rivera AlbaoNo ratings yet

- Unit Descriptive Prose-3: 4.0 ObjectivesDocument11 pagesUnit Descriptive Prose-3: 4.0 ObjectivesShilpa ShuklaNo ratings yet

- Yeyeye MagazineDocument24 pagesYeyeye MagazineYamikani Jamali HassanNo ratings yet

- "A Fair Skinned Kashmiri Brahmana": Annie Besant and The Portraits of The MastersDocument37 pages"A Fair Skinned Kashmiri Brahmana": Annie Besant and The Portraits of The MastersGustavo Prudente Salerno Corrêa100% (1)

- The Book of Gold: A 17th Century Magical Grimoire of Amulets, Charms, Prayers, Sigils and Spells Using The Biblical Psalms of King David by David Rankine & Paul Harry BarronDocument1 pageThe Book of Gold: A 17th Century Magical Grimoire of Amulets, Charms, Prayers, Sigils and Spells Using The Biblical Psalms of King David by David Rankine & Paul Harry BarronMogg Morgan20% (10)

- Islam and ScienceDocument3 pagesIslam and Sciencenoelbaba71No ratings yet

- Supreme Court: Republic of The PhilippinesDocument2 pagesSupreme Court: Republic of The PhilippinesJimi SolomonNo ratings yet

- Lighting The Right Fire WithinDocument7 pagesLighting The Right Fire WithinSuhas PatilNo ratings yet

- Read The Bible in 90 Days Reading ScheduleDocument1 pageRead The Bible in 90 Days Reading ScheduleRaine CarrawayNo ratings yet

- Pintu CVDocument2 pagesPintu CVpkuila605No ratings yet

- Module 2 - Philippine LiteratureDocument29 pagesModule 2 - Philippine Literaturejeanson remarcaNo ratings yet

- Critique of Comte's Law of Three StagesDocument13 pagesCritique of Comte's Law of Three StagesPaul Horrigan80% (5)

- Vaish FedrationDocument86 pagesVaish FedrationJayCharleys50% (2)

- The Holy Spirit in The QuranDocument3 pagesThe Holy Spirit in The Qurancatam2009No ratings yet

- Ask of God, That Giveth To All Men LiberallyDocument4 pagesAsk of God, That Giveth To All Men LiberallySeeker6801No ratings yet

- HEALING SCHOOL MANUAL-Eng PDFDocument52 pagesHEALING SCHOOL MANUAL-Eng PDFnoxa100% (1)

- Chapter 1 - Southeast Asia, An OverviewDocument52 pagesChapter 1 - Southeast Asia, An OverviewFaiz FahmiNo ratings yet

- SB 7.6 - Prahlāda Instructs His Demoniac Schoolmates - Bhaktivedanta Vedabase OnlineDocument12 pagesSB 7.6 - Prahlāda Instructs His Demoniac Schoolmates - Bhaktivedanta Vedabase OnlinedhanNo ratings yet

- Norms of MoralityDocument28 pagesNorms of Moralitykristine_joanneNo ratings yet

- Panitia Kegiatan Ospektren Orientasi Pengenalan Kampus Dan Pesantren (Ospektren) Universitas Nurul Jadid Paiton Probolinggo 2021Document3 pagesPanitia Kegiatan Ospektren Orientasi Pengenalan Kampus Dan Pesantren (Ospektren) Universitas Nurul Jadid Paiton Probolinggo 2021ainul hasanNo ratings yet