Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Guideline For The Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of ADHD 2019

Guideline For The Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of ADHD 2019

Uploaded by

Humberto Cabañas VelaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Guideline For The Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of ADHD 2019

Guideline For The Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of ADHD 2019

Uploaded by

Humberto Cabañas VelaCopyright:

Available Formats

CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE

Clinical Practice Guideline for the

Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity

Disorder in Children and Adolescents

Mark L. Wolraich, MD, FAAP,a Joseph F. Hagan, Jr, MD, FAAP,b,c Carla Allan, PhD,d,e Eugenia Chan, MD, MPH, FAAP,f,g

Dale Davison, MSpEd, PCC,h,i Marian Earls, MD, MTS, FAAP,j,k Steven W. Evans, PhD,l,m Susan K. Flinn, MA,n

Tanya Froehlich, MD, MS, FAAP,o,p Jennifer Frost, MD, FAAFP,q,r Joseph R. Holbrook, PhD, MPH,s

Christoph Ulrich Lehmann, MD, FAAP,t Herschel Robert Lessin, MD, FAAP,u Kymika Okechukwu, MPA,v

Karen L. Pierce, MD, DFAACAP,w,x Jonathan D. Winner, MD, FAAP,y William Zurhellen, MD, FAAP,z SUBCOMMITTEE ON CHILDREN AND

ADOLESCENTS WITH ATTENTION-DEFICIT/HYPERACTIVE DISORDER

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is 1 of the most common abstract

neurobehavioral disorders of childhood and can profoundly affect children’s a

Section of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, University of

academic achievement, well-being, and social interactions. The American Academy Oklahoma, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma; bDepartment of Pediatrics, The

of Pediatrics first published clinical recommendations for evaluation and Robert Larner, MD, College of Medicine, The University of Vermont,

Burlington, Vermont; cHagan, Rinehart, and Connolly Pediatricians,

diagnosis of pediatric ADHD in 2000; recommendations for treatment followed PLLC, Burlington, Vermont; dDivision of Developmental and Behavioral

in 2001. The guidelines were revised in 2011 and published with an accompanying Health, Department of Pediatrics, Children’s Mercy Kansas City, Kansas

City, Missouri; eSchool of Medicine, University of Missouri-Kansas City,

process of care algorithm (PoCA) providing discrete and manageable steps by Kansas City, Missouri; fDivision of Developmental Medicine, Boston

which clinicians could fulfill the clinical guideline’s recommendations. Since the Children’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts; gHarvard Medical School,

Harvard University, Boston, Massachusetts; hChildren and Adults with

release of the 2011 guideline, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Lanham, Maryland; iDale

Disorders has been revised to the fifth edition, and new ADHD-related research Davison, LLC, Skokie, Illinois; jCommunity Care of North Carolina,

has been published. These publications do not support dramatic changes to Raleigh, North Carolina; kSchool of Medicine, University of North

Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina; lDepartment of Psychology, Ohio

the previous recommendations. Therefore, only incremental updates have been University, Athens, Ohio; mCenter for Intervention Research in Schools,

made in this guideline revision, including the addition of a key action statement Ohio University, Athens, Ohio; nAmerican Academy of Pediatrics,

Alexandria, Virginia; oDepartment of Pediatrics, University of

related to diagnosis and treatment of comorbid conditions in children and Cincinnati, Cincinnati, Ohio; pCincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical

adolescents with ADHD. The accompanying process of care algorithm has also Center, Cincinnati, Ohio; qSwope Health Services, Kansas City, Kansas;

r

American Academy of Family Physicians, Leawood, Kansas; sNational

been updated to assist in implementing the guideline recommendations. Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, Centers for

Throughout the process of revising the guideline and algorithm, numerous Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia; tDepartments of

Biomedical Informatics and Pediatrics, Vanderbilt University, Nashville,

systemic barriers were identified that restrict and/or hamper pediatric clinicians’ Tennessee; uThe Children’s Medical Group, Poughkeepsie, New York;

ability to adopt their recommendations. Therefore, the subcommittee created

a companion article (available in the Supplemental Information) on systemic

To cite: Wolraich ML, Hagan JF, Allan C, et al. AAP

barriers to the care of children and adolescents with ADHD, which identifies the

SUBCOMMITTEE ON CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS WITH

major systemic-level barriers and presents recommendations to address those ATTENTION-DEFICIT/HYPERACTIVE DISORDER. Clinical Practice

barriers; in this article, we support the recommendations of the clinical practice Guideline for the Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of

guideline and accompanying process of care algorithm. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Children and

Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2019;144(4):e20192528

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news by guest on October 17, 2019

PEDIATRICS Volume 144, number 4, October 2019:e20192528 FROM THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS

INTRODUCTION implementation of such a resource. In care to the patient and his or her

This article updates and replaces the response, this guideline is supported family. There is some evidence that

2011 clinical practice guideline by 2 accompanying documents, African American and Latino children

revision published by the American available in the Supplemental are less likely to have ADHD

Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), “Clinical Information: (1) a process of care diagnosed and are less likely to be

Practice Guideline: Diagnosis and algorithm (PoCA) for the diagnosis treated for ADHD. Special attention

Evaluation of the Child with and treatment of children and should be given to these populations

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity adolescents with ADHD and (2) an when assessing comorbidities as they

Disorder.”1 This guideline, like the article on systemic barriers to the relate to ADHD and when treating for

previous document, addresses the care of children and adolescents with ADHD symptoms.3 Given the

evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment ADHD. These supplemental nationwide problem of limited access

of attention-deficit/hyperactivity documents are designed to aid PCCs to mental health clinicians,4

disorder (ADHD) in children from age in implementing the formal pediatricians and other PCCs are

4 years to their 18th birthday, with recommendations for the evaluation, increasingly called on to provide

special guidance provided for ADHD diagnosis, and treatment of children services to patients with ADHD and to

care for preschool-aged children and and adolescents with ADHD. Although their families. In addition, the AAP

adolescents. (Note that for the this document is specific to children holds that primary care pediatricians

purposes of this document, and adolescents in the United States should be prepared to diagnose and

“preschool-aged” refers to children in some of its recommendations, manage mild-to-moderate ADHD,

from age 4 years to the sixth international stakeholders can modify anxiety, depression, and problematic

birthday.) Pediatricians and other specific content (ie, educational laws substance use, as well as co-manage

primary care clinicians (PCCs) may about accommodations, etc) as patients who have more severe

continue to provide care after needed. (Prevention is addressed in conditions with mental health

18 years of age, but care beyond this the Mental Health Task Force professionals. Unfortunately, third-

age was not studied for this guideline. recommendations.2) party payers seldom pay

appropriately for these time-

Since 2011, much research has PoCA for the Diagnosis and consuming services.5,6

Treatment of Children and

occurred, and the Diagnostic and

Adolescents With ADHD To assist pediatricians and other

Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders,

In this revised guideline and PCCs in overcoming such obstacles,

Fifth Edition (DSM-5), has been

accompanying PoCA, we recognize the companion article on systemic

released. The new research and DSM-

that evaluation, diagnosis, and barriers to the care of children and

5 do not, however, support dramatic

treatment are a continuous process. adolescents with ADHD reviews the

changes to the previous

The PoCA provides recommendations barriers and makes recommendations

recommendations. Hence, this new

for implementing the guideline steps, to address them to enhance care for

guideline includes only incremental

although there is less evidence for the children and adolescents with ADHD.

updates to the previous guideline.

One such update is the addition of PoCA than for the guidelines. The

a key action statement (KAS) about section on evaluating and treating

comorbidities has also been expanded ADHD EPIDEMIOLOGY AND SCOPE

the diagnosis and treatment of

coexisting or comorbid conditions in in the PoCA document. Prevalence estimates of ADHD vary

children and adolescents with ADHD. on the basis of differences in research

Systems Barriers to the Care of methodologies, the various age

The subcommittee uses the term

Children and Adolescents With ADHD

“comorbid,” to be consistent with the groups being described, and changes

DSM-5. There are many system-level barriers in diagnostic criteria over time.7

that hamper the adoption of the best- Authors of a recent meta-analysis

Since 2011, the release of new practice recommendations contained calculated a pooled worldwide ADHD

research reflects an increased in the clinical practice guideline and prevalence of 7.2% among children8;

understanding and recognition of the PoCA. The procedures estimates from some community-

ADHD’s prevalence and recommended in this guideline based samples are somewhat higher,

epidemiology; the challenges it raises necessitate spending more time with at 8.7% to 15.5%.9,10 National survey

for children and families; the need for patients and their families, data from 2016 indicate that 9.4% of

a comprehensive clinical resource for developing a care management children in the United States 2 to

the evaluation, diagnosis, and system of contacts with school and 17 years of age have ever had an

treatment of pediatric ADHD; and the other community stakeholders, and ADHD diagnosis, including 2.4% of

barriers that impede the providing continuous, coordinated children 2 to 5 years of age.11 In that

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news by guest on October 17, 2019

2 FROM THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS

national survey, 8.4% of children 2 to developmentally capable of Centers of the US Agency for

17 years of age currently had ADHD, compensating for their weaknesses), Healthcare Research and Quality

representing 5.4 million children.11 for most children, retention is not (AHRQ).23 These questions assessed

Among children and adolescents with beneficial.22 4 diagnostic areas and 3 treatment

current ADHD, almost two-thirds areas on the basis of research

were taking medication, and published in 2011 through 2016.

METHODOLOGY

approximately half had received The AHRQ’s framework was guided

behavioral treatment of ADHD in the As with the original 2000 clinical

by key clinical questions addressing

past year. Nearly one quarter had practice guideline and the 2011

diagnosis as well as treatment

received neither type of treatment of revision, the AAP collaborated with

interventions for children and

ADHD.11 several organizations to form

adolescents 4 to 18 years of age.

a subcommittee on ADHD (the

Symptoms of ADHD occur in subcommittee) under the oversight of The first clinical questions pertaining

childhood, and most children with the AAP Council on Quality to ADHD diagnosis were as follows:

ADHD will continue to have Improvement and Patient Safety. 1. What is the comparative

symptoms and impairment through

The subcommittee’s membership diagnostic accuracy of approaches

adolescence and into adulthood.

included representation of a wide that can be used in the primary

According to a 2014 national survey,

range of primary care and care practice setting or by

the median age of diagnosis was

subspecialty groups, including specialists to diagnose ADHD

7 years; approximately one-third of

primary care pediatricians, among children younger than

children were diagnosed before

developmental-behavioral 7 years of age?

6 years of age.12 More than half of

these children were first diagnosed pediatricians, an epidemiologist from 2. What is the comparative

by a PCC, often a pediatrician.12 As the Centers for Disease Control and diagnostic accuracy of EEG,

individuals with ADHD enter Prevention; and representatives from imaging, or executive function

adolescence, their overt hyperactive the American Academy of Child and approaches that can be used in the

and impulsive symptoms tend to Adolescent Psychiatry, the Society for primary care practice setting or by

decline, whereas their inattentive Pediatric Psychology, the National specialists to diagnose ADHD

symptoms tend to persist.13,14 Association of School Psychologists, among individuals aged 7 to their

Learning and language problems are the Society for Developmental and 18th birthday?

common comorbid conditions with Behavioral Pediatrics (SDBP), the 3. What are the adverse effects

ADHD.15 American Academy of Family associated with being labeled

Physicians, and Children and Adults correctly or incorrectly as having

Boys are more than twice as likely as with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity ADHD?

girls to receive a diagnosis of Disorder (CHADD) to provide

4. Are there more formal

ADHD,9,11,16 possibly because feedback on the patient/parent

neuropsychological, imaging, or

hyperactive behaviors, which are perspective.

genetic tests that improve the

easily observable and potentially

This subcommittee met over a 3.5- diagnostic process?

disruptive, are seen more frequently

year period from 2015 to 2018 to The treatment questions were as

in boys. The majority of both boys

review practice changes and newly follows:

and girls with ADHD also meet

identified issues that have arisen

diagnostic criteria for another mental 1. What are the comparative safety

since the publication of the 2011

disorder.17,18 Boys are more likely to and effectiveness of pharmacologic

guidelines. The subcommittee

exhibit externalizing conditions like and/or nonpharmacologic

members’ potential conflicts were

oppositional defiant disorder or treatments of ADHD in improving

identified and taken into

conduct disorder.17,19,20 Recent outcomes associated with ADHD?

consideration in the group’s

research has established that girls

deliberations. No conflicts prevented 2. What is the risk of diversion of

with ADHD are more likely than boys

subcommittee member participation pharmacologic treatment?

to have a comorbid internalizing

on the guidelines. 3. What are the comparative safety

condition like anxiety or

depression.21 and effectiveness of different

Research Questions monitoring strategies to evaluate

Although there is a greater risk of The subcommittee developed a series the effectiveness of treatment or

receiving a diagnosis of ADHD for of research questions to direct an changes in ADHD status (eg,

children who are the youngest in evidence-based review sponsored by worsening or resolving

their class (who are therefore less 1 of the Evidence-based Practice symptoms)?

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news by guest on October 17, 2019

PEDIATRICS Volume 144, number 4, October 2019 3

In addition to this review of the

research questions, the subcommittee

considered information from a review

of evidence-based psychosocial

treatments for children and

adolescents with ADHD24 (which, in

some cases, affected the evidence

grade) as well as updated information

on prevalence from the Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention.

Evidence Review

This article followed the latest

version of the evidence base update

format used to develop the previous 3

clinical practice guidelines.24–26

Under this format, studies were only

included in the review when they met

a variety of criteria designed to

ensure the research was based on

a strong methodology that yielded

confidence in its conclusions.

The level of efficacy for each

treatment was defined on the basis of

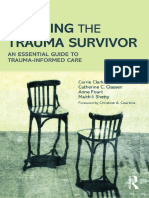

child-focused outcomes related to FIGURE 1

AAP rating of evidence and recommendations.

both symptoms and impairment.

Hence, improvements in behaviors on

the part of parents or teachers, such

sites/default/files/pdf/cer-203-adhd- demonstrated a preponderance of

as the use of communication or

final_0.pdf. benefits over harms, the KAS provides

praise, were not considered in the

a “strong recommendation” or

review. Although these outcomes are The evidence is discussed in more

“recommendation.”27 Clinicians

important, they address how detail in published reports and

should follow a “strong

treatment reaches the child or articles.25

recommendation” unless a clear and

adolescent with ADHD and are,

Guideline Recommendations and Key compelling rationale for an

therefore, secondary to changes in the

Action Statements alternative approach is present;

child’s behavior. Focusing on

clinicians are prudent to follow

improvements in the child or The AAP policy statement, a “recommendation” but are advised

adolescent’s symptoms and “Classifying Recommendations for to remain alert to new information

impairment emphasizes the Clinical Practice Guidelines,” was and be sensitive to patient

disorder’s characteristics and followed in designating aggregate preferences27 (see Fig 1).

manifestations that affect children evidence quality levels for the

and their families. available evidence (see Fig 1).27 The When the scientific evidence

AAP policy statement is consistent comprised lower-quality or limited

The treatment-related evidence relied

with the grading recommendations data and expert consensus or high-

on a recent review of literature from

advanced by the University of quality evidence with a balance

2011 through 2016 by the AHRQ of

Oxford Centre for Evidence Based between benefits and harms, the KAS

citations from Medline, Embase,

Medicine. provides an “option” level of

PsycINFO, and the Cochrane Database

recommendation. Options are clinical

of Systematic Reviews. The subcommittee reached consensus

interventions that a reasonable

on the evidence, which was then used

The original methodology and report, health care provider might or might

to develop the clinical practice

including the evidence search and not wish to implement in the

guideline’s KASs.

review, are available in their entirety practice.27 Where the evidence

and as an executive summary at When the scientific evidence was at was lacking, a combination of

https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ least “good” in quality and evidence and expert consensus

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news by guest on October 17, 2019

4 FROM THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS

would be used, although this These KASs provide for consistent (Table 2). (Grade B: strong

did not occur in these and high-quality care for children and recommendation.)

guidelines, and all KASs adolescents who may have symptoms

achieved a “strong suggesting attention disorders or The basis for this recommendation is

recommendation” level except problems as well as for their families. essentially unchanged from the

for KAS 7, on comorbidities, In developing the 7 KASs, the previous guideline. As noted, ADHD is

which received a recommendation subcommittee considered the the most common neurobehavioral

level (see Fig 1). requirements for establishing the disorder of childhood, occurring in

diagnosis; the prevalence of ADHD; approximately 7% to 8% of children

As shown in Fig 1, integrating the effect of untreated ADHD; the and youth.8,18,28,29 Hence, the number

evidence quality appraisal with an efficacy and adverse effects of of children with this condition is far

assessment of the anticipated balance treatment; various long-term greater than can be managed by the

between benefits and harms leads to outcomes; the importance of mental health system.4 There is

a designation of a strong coordination between pediatric and evidence that appropriate diagnosis

recommendation, recommendation, mental health service providers; the can be accomplished in the primary

option, or no recommendation. value of the medical home; and the care setting for children and

common occurrence of comorbid adolescents.30,31 Note that there is

Once the evidence level was conditions, the importance of insufficient evidence to recommend

determined, an evidence grade was addressing them, and the effects of diagnosis or treatment for children

assigned. AAP policy stipulates that not treating them. younger than 4 years (other than

the evidence supporting each KAS be parent training in behavior

prospectively identified, appraised, The subcommittee members with the management [PTBM], which does not

and summarized, and an explicit link most epidemiological experience require a diagnosis to be applied); in

between quality levels and the grade assessed the strength of each instances in which ADHD-like

of recommendation must be defined. recommendation and the quality of symptoms in children younger than

Possible grades of recommendations evidence supporting each draft KAS. 4 years bring substantial impairment,

range from “A” to “D,” with “A” being PCCs can consider making a referral

the highest: Peer Review for PTBM.

• grade A: consistent level A studies; The guidelines and PoCA underwent

• grade B: consistent level B or extensive peer review by more than KAS 2

extrapolations from level A studies; 30 internal stakeholders (eg, AAP

To make a diagnosis of ADHD, the

• grade C: level C studies or committees, sections, councils, and

PCC should determine that DSM-5

extrapolations from level B or level task forces) and external stakeholder

criteria have been met, including

C studies; groups identified by the

documentation of symptoms and

subcommittee. The resulting

• grade D: level D evidence or impairment in more than 1 major

comments were compiled and

troublingly inconsistent or setting (ie, social, academic, or

reviewed by the chair and vice chair;

inconclusive studies of any level; occupational), with information

relevant changes were incorporated

and obtained primarily from reports from

into the draft, which was then

• level X: not an explicit level of reviewed by the full subcommittee.

parents or guardians, teachers, other

evidence as outlined by the Centre school personnel, and mental health

for Evidence-Based Medicine. This clinicians who are involved in the

level is reserved for interventions KASS FOR THE EVALUATION, child or adolescent’s care. The PCC

that are unethical or impossible to DIAGNOSIS, TREATMENT, AND should also rule out any alternative

test in a controlled or scientific MONITORING OF CHILDREN AND cause (Table 3). (Grade B: strong

fashion and for which the ADOLESCENTS WITH ADHD recommendation.)

preponderance of benefit or harm

KAS 1 The American Psychiatric Association

is overwhelming, precluding

rigorous investigation. The pediatrician or other PCC should developed the DSM-5 using expert

initiate an evaluation for ADHD for consensus and an expanding research

Guided by the evidence quality and any child or adolescent age 4 years to foundation.32 The DSM-5 system is

grade, the subcommittee developed 7 the 18th birthday who presents with used by professionals in psychiatry,

KASs for the evaluation, diagnosis, academic or behavioral problems and psychology, health care systems, and

and treatment of ADHD in children symptoms of inattention, primary care; it is also well

and adolescents (see Table 1). hyperactivity, or impulsivity established with third-party payers.

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news by guest on October 17, 2019

PEDIATRICS Volume 144, number 4, October 2019 5

TABLE 1 Summary of KASs for Diagnosing, Evaluating, and Treating ADHD in Children and Adolescents

KASs Evidence Quality, Strength of Recommendation

KAS 1: The pediatrician or other PCC should initiate an evaluation for ADHD for any child or Grade B, strong recommendation

adolescent age 4 years to the 18th birthday who presents with academic or behavioral

problems and symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, or impulsivity.

KAS 2: To make a diagnosis of ADHD, the PCC should determine that DSM-5 criteria have been Grade B, strong recommendation

met, including documentation of symptoms and impairment in more than 1 major setting

(ie, social, academic, or occupational), with information obtained primarily from reports

from parents or guardians, teachers, other school personnel, and mental health

clinicians who are involved in the child or adolescent’s care. The PCC should also rule out

any alternative cause.

KAS 3: In the evaluation of a child or adolescent for ADHD, the PCC should include a process Grade B, strong recommendation

to at least screen for comorbid conditions, including emotional or behavioral conditions

(eg, anxiety, depression, oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorders, substance use),

developmental conditions (eg, learning and language disorders, autism spectrum

disorders), and physical conditions (eg, tics, sleep apnea).

KAS 4: ADHD is a chronic condition; therefore, the PCC should manage children and Grade B, strong recommendation

adolescents with ADHD in the same manner that they would children and youth with

special health care needs, following the principles of the chronic care model and the

medical home.

KAS 5a: For preschool-aged children (age 4 years to the sixth birthday) with ADHD, the PCC Grade A, strong recommendation for PTBM

should prescribe evidence-based PTBM and/or behavioral classroom interventions as the

first line of treatment, if available.

Methylphenidate may be considered if these behavioral interventions do not provide Grade B, strong recommendation for methylphenidate

significant improvement and there is moderate-to-severe continued disturbance in the

4- through 5-year-old child’s functioning. In areas in which evidence-based behavioral

treatments are not available, the clinician needs to weigh the risks of starting

medication before the age of 6 years against the harm of delaying treatment.

KAS 5b. For elementary and middle school-aged children (age 6 years to the 12th birthday) Grade A, strong recommendation for medications

with ADHD, the PCC should prescribe FDA-approved medications for ADHD, along with Grade A, strong recommendation for training and behavioral

PTBM and/or behavioral classroom intervention (preferably both PTBM and behavioral treatments for ADHD with family and school

classroom interventions). Educational interventions and individualized instructional

supports, including school environment, class placement, instructional placement, and

behavioral supports, are a necessary part of any treatment plan and often include an IEP

or a rehabilitation plan (504 plan).

KAS 5c. For adolescents (age 12 years to the 18th birthday) with ADHD, the PCC should Grade A, strong recommendation for medications

prescribe FDA-approved medications for ADHD with the adolescent’s assent. The PCC is Grade A, strong recommendation for training and behavioral

encouraged to prescribe evidence-based training interventions and/or behavioral treatments for ADHD with the family and school

interventions as treatment of ADHD, if available. Educational interventions and

individualized instructional supports, including school environment, class placement,

instructional placement, and behavioral supports, are a necessary part of any treatment

plan and often include an IEP or a rehabilitation plan (504 plan).

KAS 6. The PCC should titrate doses of medication for ADHD to achieve maximum benefit with Grade B, strong recommendation

tolerable side effects.

KAS 7. The PCC, if trained or experienced in diagnosing comorbid conditions, may initiate Grade C, recommendation

treatment of such conditions or make a referral to an appropriate subspecialist for

treatment. After detecting possible comorbid conditions, if the PCC is not trained or

experienced in making the diagnosis or initiating treatment, the patient should be

referred to an appropriate subspecialist to make the diagnosis and initiate treatment.

The DSM-5 criteria define 4 3. attention-deficit/hyperactivity standard most frequently used by

dimensions of ADHD: disorder combined presentation clinicians and researchers to render

1. attention-deficit/hyperactivity (ADHD/C) (314.01 [F90.2]); and the diagnosis and document its

disorder primarily of the 4. ADHD other specified and appropriateness for a given child.

inattentive presentation (ADHD/I) unspecified ADHD (314.01 The use of neuropsychological

(314.00 [F90.0]); [F90.8]). testing has not been found to

2. attention-deficit/hyperactivity As with the previous guideline improve diagnostic accuracy in

disorder primarily of the recommendations, the DSM-5 most cases, although it may have

hyperactive-impulsive classification criteria are based on benefit in clarifying the child

presentation (ADHD/HI) (314.01 the best available evidence for or adolescent’s learning

[F90.1]); ADHD diagnosis and are the strengths and weaknesses. (See the

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news by guest on October 17, 2019

6 FROM THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS

TABLE 2 KAS 1: The pediatrician or other PCC should initiate an evaluation for ADHD for any child or adolescent age 4 years to the 18th birthday who

presents with academic or behavioral problems and symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, or impulsivity. (Grade B: strong recommendation.)

Aggregate evidence Grade B

quality

Benefits ADHD goes undiagnosed in a considerable number of children and adolescents. Primary care clinicians’ more-rigorous identification

of children with these problems is likely to decrease the rate of undiagnosed and untreated ADHD in children and adolescents.

Risks, harm, cost Children and adolescents in whom ADHD is inappropriately diagnosed may be labeled inappropriately, or another condition may be

missed, and they may receive treatments that will not benefit them.

Benefit-harm The high prevalence of ADHD and limited mental health resources require primary care pediatricians and other PCCs to play

assessment a significant role in the care of patients with ADHD and assist them to receive appropriate diagnosis and treatment. Treatments

available have good evidence of efficacy, and a lack of treatment has the risk of impaired outcomes.

Intentional vagueness There are limits between what a PCC can address and what should be referred to a subspecialist because of varying degrees of skills

and comfort levels present among the former.

Role of patient Success with treatment is dependent on patient and family preference, which need to be taken into account.

preferences

Exclusions None.

Strength Strong recommendation.

Key references Wolraich et al31; Visser et al28; Thomas et al8; Egger et al30

PoCA for more information on should conduct a clinical interview children younger than 18 years (ie,

implementing this KAS.) with parents, examine and observe preschool-aged children, elementary

the child, and obtain information and middle school–aged children, and

Special Circumstances: Preschool-Aged from parents and teachers through adolescents) and are only minimally

Children (Age 4 Years to the Sixth DSM-based ADHD rating scales.40 different from the DSM-IV. Hence, if

Birthday) Normative data are available for the clinicians do not have the ADHD

DSM-5–based rating scales for ages Rating Scale-5 or the ADHD Rating

There is evidence that the diagnostic

criteria for ADHD can be applied to 5 years to the 18th birthday.41 There Scale-IV Preschool Version,42 any

preschool-aged children.33–39 A are, however, minimal changes in the other DSM-based scale can be used to

review of the literature, including the specific behaviors from the DSM-IV, provide a systematic method for

multisite study of the efficacy of on which all the other DSM-based collecting information from parents

methylphenidate in preschool-aged ADHD rating scales obtained and teachers, even in the absence of

children, found that the DSM-5 normative data. Both the ADHD normative data.

criteria could appropriately identify Rating Scale-IV and the Conners

children with ADHD.25 Rating Scale have preschool-age Pediatricians and other PCCs should

normative data based on the DSM-IV. be aware that determining the

To make a diagnosis of ADHD in The specific behaviors in the DSM-5 presence of key symptoms in this age

preschool-aged children, clinicians criteria for ADHD are the same for all group has its challenges, such as

TABLE 3 KAS 2: To make a diagnosis of ADHD, the PCC should determine that DSM-5 criteria have been met, including documentation of symptoms and

impairment in more than 1 major setting (ie, social, academic, or occupational), with information obtained primarily from reports from parents

or guardians, teachers, other school personnel, and mental health clinicians who are involved in the child or adolescent’s care. The PCC should

also rule out any alternative cause. (Grade B: strong recommendation.)

Aggregate evidence Grade B

quality

Benefits Use of the DSM-5 criteria has led to more uniform categorization of the condition across professional disciplines. The criteria are

essentially unchanged from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV), for children up to

their 18th birthday, except that DSM-IV required onset prior to age 7 for a diagnosis, while DSM-5 requires onset prior to age 12.

Risks, harm, cost The DSM-5 does not specifically state that symptoms must be beyond expected levels for developmental (rather than chronologic) age

to qualify for an ADHD diagnosis, which may lead to some misdiagnoses in children with developmental disorders.

Benefit-harm The benefits far outweigh the harm.

assessment

Intentional vagueness None.

Role of patient Although there is some stigma associated with mental disorder diagnoses, resulting in some families preferring other diagnoses, the

preferences need for better clarity in diagnoses outweighs this preference.

Exclusions None.

Strength Strong recommendation.

Key references Evans et al25; McGoey et al42; Young43; Sibley et al46

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news by guest on October 17, 2019

PEDIATRICS Volume 144, number 4, October 2019 7

observing symptoms across multiple many adolescents have multiple be aware that adolescents are at

settings as required by the DSM-5, teachers. Likewise, an adolescent’s greater risk for substance use than

particularly among children who do parents may have less opportunity to are younger children.44,45,47 Certain

not attend a preschool or child care observe their child’s behaviors than substances, such as marijuana, can

program. Here, too, focused checklists they did when the child was younger. have effects that mimic ADHD;

can be used to aid in the diagnostic Furthermore, some problems adolescent patients may also attempt

evaluation. experienced by children with ADHD to obtain stimulant medication to

are less obvious in adolescents than enhance performance (ie, academic,

PTBM is the recommended primary

in younger children because athletic, etc) by feigning symptoms.48

intervention for preschool-aged

adolescents are less likely to exhibit

children with ADHD as well as Trauma experiences, posttraumatic

overt hyperactive behavior. Of note,

children with ADHD-like behaviors stress disorder, and toxic stress are

adolescents’ reports of their own

whose diagnosis is not yet verified. additional comorbidities and risk

behaviors often differ from other

This type of training helps parents factors of concern.

observers because they tend to

learn age-appropriate developmental

minimize their own problematic

expectations, behaviors that

behaviors.43–45 Special Circumstances: Inattention or

strengthen the parent-child

Hyperactivity/Impulsivity (Problem

relationship, and specific Despite these difficulties, clinicians Level)

management skills for problem need to try to obtain information

behaviors. Clinicians do not need to from at least 2 teachers or other Teachers, parents, and child health

have made an ADHD diagnosis before sources, such as coaches, school professionals typically encounter

recommending PTBM because PTBM guidance counselors, or leaders of children who demonstrate behaviors

has documented effectiveness with community activities in which the relating to activity level, impulsivity,

a wide variety of problem behaviors, adolescent participates.46 For the and inattention but who do not fully

regardless of etiology. In addition, the evaluation to be successful, it is meet DSM-5 criteria. When assessing

intervention’s results may inform the essential that adolescents agree with these children, diagnostic criteria

subsequent diagnostic evaluation. and participate in the evaluation. should be closely reviewed, which

Clinicians are encouraged to Variability in ratings is to be may require obtaining more

recommend that parents complete expected because adolescents’ information from other settings and

PTBM, if available, before assigning behavior often varies between sources. Also consider that these

an ADHD diagnosis. different classrooms and with symptoms may suggest other

different teachers. Identifying problems that mimic ADHD.

After behavioral parent training is

implemented, the clinician can reasons for any variability can Behavioral interventions, such

obtain information from parents and provide valuable clinical insight into as PTBM, are often beneficial for

teachers through DSM-5–based the adolescent’s problems. children with hyperactive/impulsive

ADHD rating scales. The clinician behaviors who do not meet full

Note that, unless they previously

may obtain reports about the diagnostic criteria for ADHD.

received a diagnosis, to meet DSM-5

parents’ ability to manage their As noted previously, these programs

criteria for ADHD, adolescents must

children and about the child’s core do not require a specific diagnosis

have some reported or documented

symptoms and impairments. to be beneficial to the family. The

manifestations of inattention or

Referral to an early intervention previous guideline discussed

hyperactivity/impulsivity before age

program or enrolling in a PTBM the diagnosis of problem-level

12. Therefore, clinicians must

program can help provide concerns on the basis of the

establish that an adolescent had

information about the child’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for

manifestations of ADHD before age

behavior in other settings or with Primary Care (DSM-PC), Child and

12 and strongly consider whether

other observers. The evaluators for

a mimicking or comorbid condition, Adolescent Version,49 and made

these programs and/or early suggestions for treatment and care.

such as substance use, depression,

childhood special education teachers The DSM-PC was published in 1995,

and/or anxiety, is present.46

may be useful observers, as well. however, and it has not been revised

In addition, the risks of mood and to be compatible with the DSM-5.

Special Circumstances: Adolescents anxiety disorders and risky sexual Therefore, the DSM-PC cannot be

(Age 12 Years to the 18th Birthday) behaviors increase during used as a definitive source for

Obtaining teacher reports for adolescence, as do the risks of diagnostic codes related to ADHD and

adolescents is often more challenging intentional self-harm and suicidal comorbid conditions, although it can

than for younger children because behaviors.31 Clinicians should also be used conceptually as a resource for

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news by guest on October 17, 2019

8 FROM THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS

enriching the understanding of condition will alter the treatment and the medical home (Table 5).

problem-level manifestations. of ADHD. (Grade B: strong recommendation.)

The SDBP is developing a clinical As in the 2 previous guidelines, this

KAS 3 practice guideline to support recommendation is based on the

clinicians in the diagnosis of evidence that for many individuals,

In the evaluation of a child or

treatment of “complex ADHD,” which ADHD causes symptoms and

adolescent for ADHD, the PCC should

includes ADHD with comorbid dysfunction over long periods of time,

include a process to at least screen

developmental and/or mental health even into adulthood. Available

for comorbid conditions, including

conditions.67 treatments address symptoms and

emotional or behavioral conditions

(eg, anxiety, depression, oppositional function but are usually not curative.

Special Circumstances: Adolescents Although the chronic illness model

defiant disorder, conduct disorders, (Age 12 Years to the 18th Birthday)

substance use), developmental has not been specifically studied in

conditions (eg, learning and language At a minimum, clinicians should children and adolescents with ADHD,

assess adolescent patients with newly it has been effective for other chronic

disorders, autism spectrum

diagnosed ADHD for symptoms and conditions, such as asthma.68 In

disorders), and physical conditions

signs of substance use, anxiety, addition, the medical home model has

(eg, tics, sleep apnea) (Table 4).

depression, and learning disabilities. been accepted as the preferred

(Grade B: strong recommendation.)

As noted, all 4 are common comorbid standard of care for children with

The majority of both boys and girls conditions that affect the treatment chronic conditions.69

with ADHD also meet diagnostic approach. These comorbidities make

it important for the clinician to The medical home and chronic illness

criteria for another mental approach may be particularly

disorder.17,18 A variety of other consider sequencing psychosocial and

medication treatments to maximize beneficial for parents who also have

behavioral, developmental, and ADHD themselves. These parents can

physical conditions can be comorbid the impact on areas of greatest risk

and impairment while monitoring for benefit from extra support to help

in children and adolescents who are them follow a consistent schedule for

evaluated for ADHD, including possible risks such as stimulant abuse

or suicidal ideation. medication and behavioral programs.

emotional or behavioral conditions or

a history of these problems. These Authors of longitudinal studies have

include but are not limited to learning KAS 4 found that ADHD treatments are

disabilities, language disorder, ADHD is a chronic condition; frequently not maintained over

disruptive behavior, anxiety, mood therefore, the PCC should manage time13 and impairments persist into

disorders, tic disorders, seizures, children and adolescents with ADHD adulthood.70 It is indicated in

autism spectrum disorder, in the same manner that they would prospective studies that patients with

developmental coordination disorder, children and youth with special ADHD, whether treated or not, are at

and sleep disorders.50–66 In some health care needs, following the increased risk for early death, suicide,

cases, the presence of a comorbid principles of the chronic care model and increased psychiatric

TABLE 4 KAS 3: In the evaluation of a child or adolescent for ADHD, the PCC should include a process to at least screen for comorbid conditions, including

emotional or behavioral conditions (eg, anxiety, depression, oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorders, substance use), developmental

conditions (eg, learning and language disorders, autism spectrum disorders), and physical conditions (eg, tics, sleep apnea). (Grade B: strong

recommendation.)

Aggregate evidence Grade B

quality

Benefits Identifying comorbid conditions is important in developing the most appropriate treatment plan for the child or adolescent with

ADHD.

Risks, harm, cost The major risk is misdiagnosing the comorbid condition(s) and providing inappropriate care.

Benefit-harm There is a preponderance of benefits over harm.

assessment

Intentional vagueness None.

Role of patient None.

preferences

Exclusions None.

Strength Strong recommendation.

Key references Cuffe et al51; Pastor and Reuben52; Bieiderman et al53; Bieiderman et al54; Bieiderman et al72; Crabtree et al57; LeBourgeois et al58;

Chan115; Newcorn et al60; Sung et al61; Larson et al66; Mahajan et al65; Antshel et al64; Rothenberger and Roessner63; Froehlich et al62

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news by guest on October 17, 2019

PEDIATRICS Volume 144, number 4, October 2019 9

TABLE 5 KAS 4: ADHD is a chronic condition; therefore, the PCC should manage children and adolescents with ADHD in the same manner that they would

children and youth with special health care needs, following the principles of the chronic care model and the medical home. (Grade B: strong

recommendation.)

Aggregate evidence quality Grade B

Benefits The recommendation describes the coordinated services that are most appropriate to manage the condition.

Risks, harm, cost Providing these services may be more costly.

Benefit-harm assessment There is a preponderance of benefits over harm.

Intentional vagueness None.

Role of patient Family preference in how these services are provided is an important consideration, because it can increase adherence.

preferences

Exclusions None

Strength Strong recommendation.

Key references Brito et al69; Biederman et al72; Scheffler et al74; Barbaresi et al75; Chang et al71; Chang et al78; Lichtenstein et al77; Harstad and

Levy80

comorbidity, particularly substance Recommendations for the Treatment 6 years against the harm of delaying

use disorders.71,72 They also have of Children and Adolescents With treatment (Table 6). (Grade B: strong

lower educational achievement than ADHD: KAS 5a, 5b, and 5c recommendation.)

those without ADHD73,74 and Recommendations vary depending on

increased rates of incarceration.75–77 the patient’s age and are presented A number of special circumstances

Treatment discontinuation also for the following age ranges: support the recommendation to

places individuals with ADHD at initiate PTBM as the first treatment

a. preschool-aged children: age of preschool-aged children (age

higher risk for catastrophic

4 years to the sixth birthday; 4 years to the sixth birthday) with

outcomes, such as motor vehicle

crashes78,79; criminality, including b. elementary and middle ADHD.25,83 Although it was limited to

drug-related crimes77 and violent school–aged children: age 6 years children who had moderate-to-

reoffending76; depression71; to the 12th birthday; and severe dysfunction, the largest

interpersonal issues80; and other c. adolescents: age 12 years to the multisite study of methylphenidate

injuries.81,82 18th birthday. use in preschool-aged children

revealed symptom improvements

The KASs are presented, followed by after PTBM alone.83 The overall

To continue providing the best care, it

information on medication, evidence for PTBM among

is important for a treating

psychosocial treatments, and special preschoolers is strong.

pediatrician or other PCC to engage in

circumstances.

bidirectional communication with

teachers and other school personnel PTBM programs for preschool-aged

as well as mental health clinicians KAS 5a children are typically group programs

involved in the child or adolescent’s For preschool-aged children (age and, although they are not always

care. This communication can be 4 years to the sixth birthday) with paid for by health insurance, they

difficult to achieve and is discussed in ADHD, the PCC should prescribe may be relatively low cost. One

both the PoCA and the section on evidence-based behavioral PTBM evidence-based PTBM, parent-child

systemic barriers to the care of and/or behavioral classroom interaction therapy, is a dyadic

children and adolescents with ADHD interventions as the first line of therapy for parent and child. The

in the Supplemental Information, as is treatment, if available (grade A: PoCA contains criteria for the

the medical home model.69 strong recommendation). clinician’s use to assess the quality of

Methylphenidate may be considered PTBM programs. If the child attends

if these behavioral interventions do preschool, behavioral classroom

Special Circumstances: Inattention not provide significant improvement interventions are also recommended.

or Hyperactivity/Impulsivity and there is moderate-to-severe In addition, preschool programs (such

(Problem Level) continued disturbance in the 4- as Head Start) and ADHD-focused

Children with inattention or through 5-year-old child’s organizations (such as CHADD84) can

hyperactivity/impulsivity at the functioning. In areas in which also provide behavioral supports. The

problem level, as well as their evidence-based behavioral issues related to referral, payment,

families, may also benefit from the treatments are not available, the and communication are discussed in

chronic illness and medical home clinician needs to weigh the risks of the section on systemic barriers in

principles. starting medication before the age of the Supplemental Information.

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news by guest on October 17, 2019

10 FROM THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS

TABLE 6 KAS 5a: For preschool-aged children (age 4 years to the sixth birthday) with ADHD, the PCC should prescribe evidence-based behavioral PTBM

and/or behavioral classroom interventions as the first line of treatment, if available (grade A: strong recommendation). Methylphenidate may be

considered if these behavioral interventions do not provide significant improvement and there is moderate-to-severe continued disturbance in

the 4- through 5-year-old child’s functioning. In areas in which evidence-based behavioral treatments are not available, the clinician needs to

weigh the risks of starting medication before the age of 6 years against the harm of delaying treatment (grade B: strong recommendation).

Aggregate evidence Grade A for PTBM; Grade B for methylphenidate

quality

Benefits Given the risks of untreated ADHD, the benefits outweigh the risks.

Risks, harm, cost Both therapies increase the cost of care; PTBM requires a high level of family involvement, whereas methylphenidate has some

potential adverse effects.

Benefit-harm Both PTBM and methylphenidate have relatively low risks; initiating treatment at an early age, before children experience repeated

assessment failure, has additional benefits. Thus, the benefits outweigh the risks.

Intentional vagueness None.

Role of patient Family preference is essential in determining the treatment plan.

preferences

Exclusions None.

Strength Strong recommendation.

Key references Greenhill et al83; Evans et al25

In areas in which evidence-based The evidence is particularly strong for it is best to introduce components at

behavioral treatments are not stimulant medications; it is sufficient, the start of high school, at about

available, the clinician needs to but not as strong, for atomoxetine, 14 years of age, and specifically focus

weigh the risks of starting extended-release guanfacine, and during the 2 years preceding high

methylphenidate before the age extended-release clonidine, in that school completion.

of 6 years against the harm of order (see the Treatment section, and

delaying diagnosis and treatment. see the PoCA for more information on Psychosocial Treatments

Other stimulant or nonstimulant implementation). Some psychosocial treatments for

medications have not been children and adolescents with ADHD

adequately studied in children in KAS 5c have been demonstrated to be

this age group with ADHD. For adolescents (age 12 years to the effective for the treatment of ADHD,

18th birthday) with ADHD, the PCC including behavioral therapy and

KAS 5b should prescribe FDA-approved training interventions.24–26,85 The

For elementary and middle medications for ADHD with the diversity of interventions and

school–aged children (age 6 years to adolescent’s assent (grade A: strong outcome measures makes it

the 12th birthday) with ADHD, the recommendation). The PCC is challenging to assess a meta-analysis

PCC should prescribe US Food and encouraged to prescribe evidence- of psychosocial treatment’s effects

Drug Administration (FDA)–approved based training interventions and/or alone or in association with

medications for ADHD, along with behavioral interventions as treatment medication treatment. As with

PTBM and/or behavioral classroom of ADHD, if available. Educational medication treatment, the long-term

intervention (preferably both PTBM interventions and individualized positive effects of psychosocial

and behavioral classroom interven- instructional supports, including treatments have yet to be determined.

tions). Educational interventions school environment, class Nonetheless, ongoing adherence

and individualized instructional placement, instructional placement, to psychosocial treatment is

supports, including school environment, and behavioral supports, are a key contributor to its beneficial

class placement, instructional a necessary part of any treatment effects, making implementation of

placement, and behavioral supports, plan and often include an IEP or a chronic care model for child health

are a necessary part of any a rehabilitation plan (504 plan) important to ensure sustained

treatment plan and often include an (Table 8). (Grade A: strong adherence.86

Individualized Education Program recommendation.) Behavioral therapy involves training

(IEP) or a rehabilitation plan (504 Transition to adult care is an adults to influence the contingencies

plan) (Table 7). (Grade A: strong important component of the chronic in an environment to improve the

recommendation for medications; care model for ADHD. Planning for behavior of a child or adolescent in

grade A: strong recommendation for the transition to adult care is an that setting. It can help parents and

PTBM training and behavioral ongoing process that may culminate school personnel learn how to

treatments for ADHD implemented after high school or, perhaps, after effectively prevent and respond to

with the family and school.) college. To foster a smooth transition, adolescent behaviors such as

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news by guest on October 17, 2019

PEDIATRICS Volume 144, number 4, October 2019 11

TABLE 7 KAS 5b: For elementary and middle school–aged children (age 6 years to the 12th birthday) with ADHD, the PCC should prescribe US Food and

Drug Administration (FDA)–approved medications for ADHD, along with PTBM and/or behavioral classroom intervention (preferably both PTBM

and behavioral classroom interventions). Educational interventions and individualized instructional supports, including school environment,

class placement, instructional placement, and behavioral supports, are a necessary part of any treatment plan and often include an

Individualized Education Program (IEP) or a rehabilitation plan (504 plan). (Grade A: strong recommendation for medications; grade A: strong

recommendation for PTBM training and behavioral treatments for ADHD implemented with the family and school.)

Aggregate evidence Grade A for Treatment with FDA-Approved Medications; Grade A for Training and Behavioral Treatments for ADHD With the Family and

quality School.

Benefits Both behavioral therapy and FDA-approved medications have been shown to reduce behaviors associated with ADHD and to improve

function.

Risks, harm, cost Both therapies increase the cost of care. Psychosocial therapy requires a high level of family and/or school involvement and may lead

to increased family conflict, especially if treatment is not successfully completed. FDA-approved medications may have some

adverse effects and discontinuation of medication is common among adolescents.

Benefit-harm Given the risks of untreated ADHD, the benefits outweigh the risks.

assessment

Intentional vagueness None.

Role of patient Family preference, including patient preference, is essential in determining the treatment plan and enhancing adherence.

preferences

Exclusions None.

Strength Strong recommendation.

Key references Evans et al25; Barbaresi et al73; Jain et al103; Brown and Bishop104; Kambeitz et al105; Bruxel et al106; Kieling et al107; Froehlich et al108;

Joensen et al109

interrupting, aggression, not symptoms. The positive effects of setting. Less research has been

completing tasks, and not complying behavioral therapies tend to persist, conducted on training interventions

with requests. Behavioral parent and but the positive effects of medication compared to behavioral treatments;

classroom training are well- cease when medication stops. nonetheless, training interventions

established treatments with Optimal care is likely to occur when are well-established treatments to

preadolescent children.25,87,88 Most both therapies are used, but the target disorganization of materials

studies comparing behavior therapy decision about therapies is heavily and time that are exhibited by

to stimulants indicate that stimulants dependent on acceptability by, and most youth with ADHD; it is likely

have a stronger immediate effect on feasibility for, the family. that they will benefit younger

the 18 core symptoms of ADHD. Training interventions target skill children, as well.25,89 Some training

Parents, however, were more satisfied development and involve repeated interventions, including social

with the effect of behavioral therapy, practice with performance feedback skills training, have not been shown

which addresses symptoms and over time, rather than modifying to be effective for children with

functions in addition to ADHD’s core behavioral contingencies in a specific ADHD.25

TABLE 8 KAS 5c: For adolescents (age 12 years to the 18th birthday) with ADHD, the PCC should prescribe FDA-approved medications for ADHD with the

adolescent’s assent (grade A: strong recommendation). The PCC is encouraged to prescribe evidence-based training interventions and/or

behavioral interventions as treatment of ADHD, if available. Educational interventions and individualized instructional supports, including school

environment, class placement, instructional placement, and behavioral supports, are a necessary part of any treatment plan and often include

an IEP or a rehabilitation plan (504 plan). (Grade A: strong recommendation.)

Aggregate evidence Grade A for Medications; Grade A for Training and Behavioral Therapy

quality

Benefits Training interventions, behavioral therapy, and FDA-approved medications have been demonstrated to reduce behaviors associated

with ADHD and to improve function.

Risks, harm, cost Both therapies increase the cost of care. Psychosocial therapy requires a high level of family and/or school involvement and may lead

to unintended increased family conflict, especially if treatment is not successfully completed. FDA-approved medications may have

some adverse effects, and discontinuation of medication is common among adolescents.

Benefit-harm Given the risks of untreated ADHD, the benefits outweigh the risks.

assessment

Intentional vagueness None.

Role of patient Family preference, including patient preference, is likely to predict engagement and persistence with a treatment.

preferences

Exclusions None.

Strength Strong recommendation.

Key references Evans et al25; Webster-Stratton et al87; Evans et al95; Fabiano et al93; Sibley and Graziano et al94; Langberg et al96; Schultz et al97; Brown

and Bishop104; Kambeitz et al105; Bruxel et al106; Froehlich et al108; Joensen et al109

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news by guest on October 17, 2019

12 FROM THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS

Some nonmedication treatments for adolescents.95–97 The greatest reducing core symptoms among

ADHD-related problems have either benefits from training interventions school-aged children and adolescents,

too little evidence to recommend them occur when treatment is continued although their effect sizes, —around

or have been found to have little or no over an extended period of time, 0.7 for all 3, are less robust than that

benefit. These include mindfulness, performance feedback is constructive of stimulant medications.

cognitive training, diet modification, and frequent, and the target Norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors

EEG biofeedback, and supportive behaviors are directly applicable to and a-2 adrenergic agonists are

counseling. The suggestion that the adolescent’s daily functioning. newer medications, so, in general, the

cannabidiol oil has any effect on ADHD evidence base supporting them is

Overall, behavioral family approaches

is anecdotal and has not been considerably less than that for

may be helpful to some adolescents

subjected to rigorous study. Although stimulants, although it was adequate

and their families, and school-based

it is FDA approved, the efficacy for for FDA approval.

training interventions are well

external trigeminal nerve stimulation

established.25,94 Meaningful A free list of the currently available,

(eTNS) is documented by one 5-week

improvements in functioning have FDA-approved medications for ADHD

randomized controlled trial with just

not been reported from cognitive is available online at www.

30 participants receiving eTNS.90 To

behavioral approaches. ADHDMedicationGuide.com. Each

date, there is no long-term safety and

medication’s characteristics are

efficacy evidence for eTNS. Overall, the Medication for ADHD provided to help guide the clinician’s

current evidence supporting

Preschool-aged children may prescription choice. With the

treatment of ADHD with eTNS is

experience increased mood lability expanded list of medications, it is less

sparse and in no way approaches the

and dysphoria with stimulant likely that PCCs need to consider the

robust strength of evidence

medications.83 None of the off-label use of other medications.

documented for established

nonstimulants have FDA approval for The section on systemic barriers in

medication and behavioral treatments

use in preschool-aged children. For the Supplemental Information

for ADHD; therefore, it cannot be

elementary school–aged students, the provides suggestions for fostering

recommended as a treatment of ADHD

evidence is particularly strong for more realistic and effective payment

without considerably more extensive

stimulant medications and is and communication systems.

study on its efficacy and safety.

sufficient, but less strong, for

Because of the large variability in

atomoxetine, extended-release

Special Circumstances: Adolescents patients’ response to ADHD

guanfacine, and extended-release

medication, there is great interest in

Much less research has been clonidine (in that order). The effect

pharmacogenetic tools that can help

published on psychosocial treatments size for stimulants is 1.0 and for

clinicians predict the best medication

with adolescents than with younger nonstimulants is 0.7. An individual’s

and dose for each child or adolescent.

children. PTBM has been modified to response to methylphenidate verses

At this time, however, the available

include the parents and adolescents amphetamine is idiosyncratic, with

scientific literature does not provide

in sessions together to develop approximately 40% responding to

sufficient evidence to support their

a behavioral contract and improve both and about 40% responding to

clinical utility given that the genetic

parent-adolescent communication only 1. The subtype of ADHD does not

variants assayed by these tools have

and problem-solving (see above).91 appear to be a predictor of response

generally not been fully studied with

Some training programs also include to a specific agent. For most

respect to medication effects on

motivational interviewing adolescents, stimulant medications

ADHD-related symptoms and/or

approaches. The evidence for this are highly effective in reducing

impairment, study findings are

behavioral family approach is mixed ADHD’s core symptoms.73

inconsistent, or effect sizes are not of

and less strong than PTBM with pre-

Stimulant medications have an effect sufficient size to ensure clinical

adolescent children.92–94 Adolescents’

size of around 1.0 (effect size = utility.104–109 For that reason, these

responses to behavioral contingencies

[treatment M 2 control M)/control pharmacogenetics tools are not

are more varied than those of

SD]) for the treatment of ADHD.98 recommended. In addition, these tests

younger children because they can

Among nonstimulant medications, 1 may cost thousands of dollars and are

often effectively obstruct behavioral

selective norepinephrine reuptake typically not covered by insurance.

contracts, increasing parent-

inhibitor, atomoxetine,99,100 and 2 For a pharmacogenetics tool to be

adolescent conflict.

selective a-2 adrenergic agonists, recommended for clinical use, studies

Training approaches that are focused extended-release guanfacine101,102 would need to reveal (1) the genetic

on school functioning skills have and extended-release clonidine,103 variants assayed have consistent,

consistently revealed benefits for have also demonstrated efficacy in replicated associations with

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news by guest on October 17, 2019

PEDIATRICS Volume 144, number 4, October 2019 13

medication response; (2) knowledge beyond that observed in children who after 2 to 3 years of treatment, on

about a patient’s genetic profile are not receiving stimulants.114–118 average. Decreases were observed

would change clinical decision- Nevertheless, before initiating therapy among those who were taller or

making, improve outcomes and/or with stimulant medications, it is heavier than average before

reduce costs or burden; and (3) the important to obtain the child or treatment.123

acceptability of the test’s operating adolescent’s history of specific cardiac

For extended-release guanfacine and

characteristics has been symptoms in addition to the family

extended-release clonidine, adverse

demonstrated (eg, sensitivity, history of sudden death,

effects include somnolence, dry

specificity, and reliability). cardiovascular symptoms, Wolff-

mouth, dizziness, irritability,

Parkinson-White syndrome,

headache, bradycardia, hypotension,

Side Effects hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and

and abdominal pain.30,124,125 Because

long QT syndrome. If any of these risk

Stimulants’ most common short-term rebound hypertension after abrupt

factors are present, clinicians should

adverse effects are appetite loss, guanfacine and clonidine

obtain additional evaluation to

abdominal pain, headaches, and discontinuation has been

ascertain and address potential safety

sleep disturbance. The Multimodal observed,126 these medications

concerns of stimulant medication use

Treatment of Attention Deficit should be tapered off rather than

by the child or adolescent.112,114

Hyperactivity Disorder (MTA) study suddenly discontinued.

results identified stimulants as having Among nonstimulants, the risk of

a more persistent effect on decreasing serious cardiovascular events is Adjunctive Therapy

growth velocity compared to most extremely low, as it is for stimulants. Adjunctive therapies may be

previous studies.110 Diminished The 3 nonstimulant medications that considered if stimulant therapy is not

growth was in the range of 1 to 2 cm are FDA approved to treat ADHD (ie, fully effective or limited by side

from predicted adult height. The atomoxetine, guanfacine, and effects. Only extended-release

results of the MTA study were clonidine) may be associated with guanfacine and extended-release

particularly noted among children changes in cardiovascular parameters clonidine have evidence supporting

who were on higher and more or other serious cardiovascular events. their use as adjunctive therapy with

consistently administered doses of These events could include increased stimulant medications sufficient to

stimulants.110 The effects diminished HR and BP for atomoxetine and have achieved FDA approval.127 Other

by the third year of treatment, but no decreased HR and BP for guanfacine medications have been used in

compensatory rebound growth was and clonidine. Clinicians are combination on an off-label basis,

observed.110 An uncommon significant recommended to not only obtain the with some limited evidence available

adverse effect of stimulants is the personal and family cardiac history, as to support the efficacy and safety of

occurrence of hallucinations and other detailed above, but also to perform using atomoxetine in combination

psychotic symptoms.111 additional evaluation if risk factors are with stimulant medications to

present before starting nonstimulant augment treatment of ADHD.128

Stimulant medications, on average,

medications (ie, perform an

increase patient heart rate (HR) and

electrocardiogram [ECG] and possibly Special Circumstances: Preschool-Aged

blood pressure (BP) to a mild and

refer to a pediatric cardiologist if the Children (Age 4 Years to the Sixth

clinically insignificant degree (average

ECG is not normal).112 Birthday)

increases: 1–2 beats per minute for HR

and 1–4 mm Hg for systolic and Additional adverse effects of If children do not experience

diastolic BP).112 However, because atomoxetine include initial adequate symptom improvement

stimulants have been linked to more somnolence and gastrointestinal tract with PTBM, medication can be

substantial increases in HR and BP in symptoms, particularly if the dosage is prescribed for those with moderate-

a subset of individuals (5%–15%), increased too rapidly, and decreased to-severe ADHD. Many young children

clinicians are encouraged to monitor appetite.119–122 Less commonly, an with ADHD may require medication

these vital signs in patients receiving increase in suicidal thoughts has been to achieve maximum improvement;

stimulant treatment.112 Although found; this is noted by an FDA black methylphenidate is the recommended

concerns have been raised about box warning. Extremely rarely, first-line pharmacologic treatment of

sudden cardiac death among children hepatitis has been associated with preschool children because of the lack

and adolescents using stimulant and atomoxetine. Atomoxetine has also of sufficient rigorous study in the

medications,113 it is an extremely rare been linked to growth delays preschool-aged population for

occurrence. In fact, stimulant compared to expected trajectories in nonstimulant ADHD medications and

medications have not been shown to the first 1 to 2 years of treatment, with dextroamphetamine. Although

increase the risk of sudden death a return to expected measurements amphetamine is the only medication

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news by guest on October 17, 2019

14 FROM THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS

with FDA approval for use in children consequences if medications are not Given the risks of driving for

younger than 6 years, this authorization initiated. Other considerations affecting adolescents with ADHD, including

was issued at a time when approval the treatment of preschool-aged crashes and motor vehicle violations,

criteria were less stringent than current children with stimulant medications special concern should be taken to

requirements. Hence, the available include the lack of information and provide medication coverage for

evidence regarding dextroampheta- experience about their longer-term symptom control while

mine’s use in preschool-aged children effects on growth and brain driving.79,136,137 Longer-acting or late-

with ADHD is not adequate to development, as well as the potential afternoon, short-acting medications

recommend it as an initial ADHD for other adverse effects in this may be helpful in this regard.138

medication treatment at this time.80 population. It may be helpful to obtain

consultation from a mental health Special Circumstances: Inattention

No nonstimulant medication has

specialist with specific experience with or Hyperactivity/Impulsivity (Problem

received sufficient rigorous study in Level)

preschool-aged children, if possible.

the preschool-aged population to be

recommended for treatment of ADHD Medication is not appropriate for

Evidence suggests that the rate of

of children 4 through 5 years of age. children whose symptoms do not

metabolizing methylphenidate is

meet DSM-5 criteria for ADHD.

Although methylphenidate is the slower in children 4 through 5 years of

Psychosocial treatments may be

ADHD medication with the strongest age, so they should be given a low dose

appropriate for these children and

evidence for safety and efficacy in to start; the dose can be increased in

adolescents. As noted, psychosocial

preschool-aged children, it should be smaller increments. Maximum doses

treatments do not require a specific

noted that the evidence has not yet have not been adequately studied in

diagnosis of ADHD, and many of the

met the level needed for FDA preschool-aged children.83

studies on the efficacy of PTBM

approval. Evidence for the use of included children who did not have

methylphenidate consists of 1 Special Circumstances: Adolescents a specific psychiatric or ADHD

multisite study of 165 children83 and (Age 12 Years to the 18th Birthday) diagnosis.

10 other smaller, single-site studies As noted, before beginning

ranging from 11 to 59 children, for medication treatment of adolescents Combination Treatments

a total of 269 children.129 Seven of the with newly diagnosed ADHD, Studies indicate that behavioral

10 single-site studies revealed efficacy clinicians should assess the patient therapy has positive effects when it is

for methylphenidate in preschoolers. for symptoms of substance use. If combined with medication for pre-

Therefore, although there is moderate active substance use is identified, the adolescent children.139 (The