Professional Documents

Culture Documents

JM Nov2012 Art07

Uploaded by

Alexandra ManeaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

JM Nov2012 Art07

Uploaded by

Alexandra ManeaCopyright:

Available Formats

Rebecca Walker Naylor, Cait Poynor Lamberton, & Patricia M.

West

Beyond the “Like” Button: The

Impact of Mere Virtual Presence on

Brand Evaluations and Purchase

Intentions in Social Media Settings

By 2011, approximately 83% of Fortune 500 companies were using some form of social media to connect with

consumers. Furthermore, surveys suggest that consumers are increasingly relying on social media to learn about

unfamiliar brands. However, best practices regarding the use of social media to bolster brand evaluations in such

situations remain undefined. This research focuses on one practice in this domain: the decision to hide or reveal

the demographic characteristics of a brand’s online supporters. The results from four studies indicate that even

when the presence of these supporters is only passively experienced and virtual (a situation the authors term “mere

virtual presence”), their demographic characteristics can influence a target consumer’s brand evaluations and

purchase intentions. The findings suggest a framework for brand managers to use when deciding whether to reveal

the identities of their online supporters or to retain ambiguity according to (1) the composition of existing supporters

relative to targeted new supporters and (2) whether the brand is likely to be evaluated singly or in combination with

competing brands.

W

Keywords: social influence, mere presence, social media, social networks, ambiguity

hile a decade and a half of work building on Hoff- who have voluntarily affiliated with the brand. We refer to

man and Novak’s (1996) analysis of computer- the passive exposure to a brand’s supporters experienced in

mediated environments has informed management such social media contexts as “mere virtual presence”

of online media, much of this work suggests that consumers (MVP). Little is known about if, or how, MVP affects con-

interact with brands online in ways similar to what they do sumers or how it can best be managed.

offline. That is, consumers join online brand communities Note that MVP takes many forms. For example, some

for many of the same reasons they join offline brand com- Facebook brand pages display profile pictures of the

munities (e.g., Algesheimer, Dholakia, and Herrmann 2005; brand’s supporters. Companies may also use Facebook

Muñiz and O’Guinn 2001; Schau, Muñiz, and Arnold 2009; Connect, so that a user’s Facebook profile picture is dis-

Thompson and Sinha 2008). played to other prospective users on their site (see, e.g.,

However, social media practitioners now seek best prac- www.Groupon.com and www.Connect.Redbullusa.com).

tices for contexts in which brick-and-mortar research is Other companies encourage consumers to post pictures of

largely inapplicable. Specifically, social media can make themselves using a brand either to their Facebook brand

the identity of a brand’s supporters transparent to prospec- page (e.g., Talbots) or to a company-run social network

tive consumers in ways that have no offline analog. Before (e.g., Burberry’s Art of the Trench website and the “How We

the advent of social networking, consumers could only Wear Them” section of Tom’s Shoes’ website). Although a

guess at the identities of other brand supporters on the basis 2011 study shows that more than 80% of Fortune 500 com-

of advertising or the identity of spokespeople. In contrast, panies use some form of social media (Hameed 2011), prac-

in the social media world, consumers viewing a brand page titioners recognize that a large number of “likes” does not

are likely to see pictorial information about other people necessarily translate into meaningful outcomes (Lake 2011).

Given that consumers increasingly look to social media to

form opinions about unfamiliar brands (Baird and Parasnis

naylor_53@fisher.osu.edu), and Patricia M. West is Associate Professor

2011; Newman 2011), how can managers use MVP to gen-

erate substantive differences in brand evaluations and pur-

Rebecca Walker Naylor is Assistant Professor of Marketing (e-mail:

of Marketing (e-mail: west_284@fisher.osu.edu), Fisher College of Busi-

chase intentions?

We answer this question by exploring the effects of four

ness, The Ohio State University. Cait Poynor Lamberton is Assistant Pro-

Pittsburgh (e-mail: cpoynor@katz.pitt.edu). Order of authorship is arbi- distinct types of MVP on brand evaluations and purchase

fessor of Marketing, Katz Graduate School of Business, University of

intentions. Note that in the pre-social-media world, the

identity of a brand’s supporters was largely unknown. The

trary; all authors contributed equally to this article. The authors thank Dar-

analog to this position in the social media world would be

ren Dahl, Jeff Inman, Greg Allenby, and Andrew Hayes for their comments

on various aspects of this research.

© 2012, American Marketing Association Journal of Marketing

ISSN: 0022-2429 (print), 1547-7185 (electronic) 105 Volume 76 (November 2012), 105–120

choosing not to reveal the identity of a brand’s online sup- contrasts with the social influence a consumer might

porters, a case we call “ambiguous MVP.” If a brand dis- encounter in an offline setting, where, for example, in a

plays the identity of its supporters, in social media settings, retail outlet, interpersonal comparison is more immediate,

this information is typically conveyed through profile pho- spatial crowding may occur, or future interaction is possible

tographs that display brand supporters’ demographic char- (e.g., Argo, Dahl, and Manchanda 2005).

acteristics.1 Relative to a target consumer, displayed MVP Notably, classic theory suggests that MVP may have lit-

may be demographically similar or demographically dis- tle effect on a consumer evaluating a new brand. Social

similar, or it may present a heterogeneous mix of similar impact theory (SIT; Latane 1981) contends that for social

and dissimilar consumers. We compare the effects of main- influence to be manifest, individuals must be present in

taining ambiguous MVP with that created by each of these large numbers and be in close proximity to the target and

types of identified MVP. In doing so, we show when it is that the influence must be provided by an important or pow-

more beneficial to reveal the identity of current brand sup- erful source. In MVP, these conditions are not met. Rather,

porters to prospective customers and when to retain ambi- brand supporters are generally displayed in small groups

guity about the brand’s support base. (making them relatively few in number), are not in physical

From a practical perspective, this research contributes proximity to the consumer, and, given that they are

to the limited academic research investigating how firms strangers to the target consumer, are low in “source

can best configure their social networks to meet strategic strength.”

objectives. For example, Tucker and Zhang (2010) demon- However, we question whether the conditions of SIT are

strate that displaying the number of sellers and buyers in necessary for MVP to exert influence. The reference group

online exchanges can change business-to-business listing literature acknowledges that knowing who the other users

and buying behavior. However, such findings provide lim- of a brand are may affect a consumer’s reaction to that

ited managerial guidance because they do not compare the brand (e.g., Bearden and Etzel 1982; Bearden, Netemeyer,

effects of displaying the number of members on a particular and Teel 1989; Berger and Heath 2007; Burnkrant and

site with the range of other actions a manager may consider Cousineau 1975; Childers and Rao 1992; Escalas and

when deciding how or whether to display online supporters. Bettman 2003). Although this literature has not explored

From a theoretical perspective, our work challenges social virtual presence of other users, it raises the possibility that

influence theory (SIT; Latane 1981), which suggests that information about a brand’s supporters may change brand

virtual exposure to unknown others should exert little social evaluations even if it does not meet SIT’s requirements. We

influence. Furthermore, we provide novel insights into first use the reference group literature to discuss the likely

social influence effects created by heterogeneous groups effects of similar and dissimilar MVP. We then make pre-

and ambiguous others, for which the traditional reference dictions about the impact of maintaining ambiguity as

group literature (e.g., Bearden and Etzel 1982; Bearden, opposed to displaying different types of MVP. We also pre-

Netemeyer, and Teel 1989; Berger and Heath 2007; dict consumers’ responses to a heterogeneous group of

Burnkrant and Cousineau 1975; Childers and Rao 1992; similar and dissimilar individuals, a topic that, while not

Escalas and Bettman 2003) is largely silent. In addition, we addressed in the reference group literature, becomes impor-

show the importance of joint versus separate evaluation tant when firms use social media platforms with potentially

mode (Hsee et al. 1999; Hsee and Leclerc 1998) as a mod- highly diverse users.

erator of the influence of ambiguous MVP. Finally, our

findings yield a road map for brand managers to use when Peas in a Pod: Similar Versus Dissimilar MVP

deciding whether to reveal the identities of their online sup-

People tend to express affinity for those to whom they are

porters or to retain ambiguity according to (1) the demo-

similar (Lydon, Jamieson, and Zanna 1988; Morry 2007;

graphic composition of existing supporters relative to tar-

Shachar and Emerson 2000). Furthermore, seeing similar

geted new supporters and (2) whether the brand is likely to

others supporting a brand will lead to greater affinity for the

be evaluated singly or in combination with competing

brand (Berger and Heath 2007; Escalas and Bettman 2003;

brands.

McCracken 1988). Target marketing relies on this idea, such

that individuals are assumed to be more persuaded by adver-

Predicting Consumer Response to tising featuring those who are similar to the self (Aaker,

MVP Brumbaugh, and Grier 2000; Deshpandé and Stayman 1994).

More recent work shows parallel effects in the context of

Building on past work in mere presence effects (e.g., Argo,

online reviews, in which consumers infer shared tastes and

Dahl, and Manchanda 2005), we use the MVP term to

preferences from verbally provided descriptive information

describe the photographic presence of brand supporters in

(vs. photos) about a reviewer, which in turn determine how

online settings. This virtual exposure to other consumers

persuasive they find the reviewer’s recommendation (Nay-

lor, Lamberton, and Norton 2011). We refer to this infer-

1Although consumers may use pictures of things other than

ence of shared preferences as “inferred commonality.”

themselves as their profile picture on social networking sites, in an

Note, however, that inferred commonality has primarily

online survey we conducted of 307 Internet users (Mage = 28.7

years), 97% of participants who reported having a Facebook pro- been considered in cases in which such inferences are ratio-

file (n = 274) indicated that they use a photograph of themselves nally based on provided information. For example, informa-

as their profile picture. tion provided in reviewer posts could rationally inform

106 / Journal of Marketing, November 2012

inferred commonality; writing style, expression of priori- person’s in-group will be subject to any stereotypes com-

ties, or shared interest could prompt reasonable consumers mon to out-groups. However, recent research on ambiguity

to generalize to other facets of preference. In contrast, the adopts an information-processing perspective and comes to

present study considers the effect of the pictorial MVP of a different conclusion. This work suggests that in the

consumers. In this case, consumers have affiliated with the absence of externally provided information about others,

brand but have done so without any persuasive intent. consumers anchor on the self to infer that ambiguous others

Moreover, they have not provided written product informa- are like them. Because of these inferences, Naylor, Lamber-

tion or recommendations to try the brand that would ground ton, and Norton (2011) demonstrate that an ambiguous

inferences of commonality. online reviewer is more persuasive than a dissimilar

Despite these differences, we expect that similar MVP reviewer and equally as persuasive as a similar reviewer.

will generate high levels of inferred commonality with a How does this research translate to the present context?

brand’s user base. We base this expectation in management Note that MVP does not involve extended formation of in-

research suggesting that demographic similarity (which we and out-groups or interaction among members. Rather, it

refer to simply as “similarity” and can be observed from involves only incidental, passive exposure to other con-

photographs) leads to inferences of deeper-level commonal- sumers. Given the nature of MVP exposure, we propose

ity. That is, even in the absence of any other information, that the information-processing explanation, rather than the

demographically similar individuals are presumed to share social categorization perspective, is likely to hold. In other

personality traits, values, and attitudes (Cunningham 2007). words, when MVP is ambiguous, consumers will project

This inferred commonality prompts the individual to raise their own characteristics onto the brand’s user base (thus

his or her evaluation of the brand. inferring commonality), emerging with a level of affinity

In contrast, previous literature has suggested that con- like that generated by similar MVP but greater than that cre-

sumers exposed to dissimilar MVP will infer little common- ated by dissimilar MVP.

ality with the brand’s users and will express lower evalua-

tions for the brand than for a brand with similar MVP. Heterogeneous MVP

Importantly, the reference group literature suggests that Although the difference between similar and dissimilar

even if the dissimilar brand supporters are not explicitly MVP can be predicted according to prior literature, existing

dissociative (i.e., members of groups with whom consumers theory fails to explain responses to heterogeneous MVP.

do not want to be associated) (White and Dahl 2006, 2007), Understanding reactions to heterogeneous groups is impor-

consumers may avoid similar purchase patterns simply due tant, because it is possible that a brand will not present sup-

to demographic dissimilarity (Berger and Heath 2008). porters that are uniformly similar or dissimilar to the target,

Work on non–target market effects also suggests that seeing either because doing so is out of their control or because

dissimilar individuals can lead consumers to infer low lev- their objectives include extension into previously unrepre-

els of commonality (Aaker et al. 2000). Thus, if MVP indi- sented market segments. Diverse groups do not form a

cates that the brand is liked by people whom target con- cohesive “reference group” in the traditional sense, and thus

sumers perceive as dissimilar, target consumers should infer the reference group literature has little to say on this point.

less commonality between themselves and the brand’s user Some prior research has suggested that diverse groups may

base and adjust their liking for the brand downward com- be interpreted in the same manner as a group perceived to

pared with when MVP is similar. be uniformly dissimilar (i.e., that the group’s preferences do

not match the target’s). For example, Jehn, Northcraft, and

Is Ignorance Bliss? Ambiguous MVP Neale (1999) argue that diversity in a workgroup cues indi-

Given that displaying MVP dissimilar to a target consumer viduals to expect opinions and behaviors that diverge from

may lower brand evaluations in comparison with similar their own. Similarly, Chatman and Flynn (2001) show that

MVP, perhaps displaying ambiguous MVP is the firm’s demographic heterogeneity within a workgroup initially

safest decision. Ambiguous MVP involves the display of leads to low levels of cooperation. However, some

others about whom no or very limited identifying demo- researchers advise broad inclusion of a wide range of con-

graphic information is provided. Thus, ambiguity may be sumers as members of social networking sites (Dholakia

manifest by not showing any pictures of brand supporters, and Vianello 2009), arguing that heterogeneity could indi-

showing only supporters who have not provided a picture, cate a brand’s wide range of features or suggest broad

or showing photos of brand supporters whose identity has appeal.

been obscured. Consistent with these recommendations, we predict that

Prior research offers little guidance regarding the use of the MVP of a heterogeneous mix of supporters can be a

ambiguous MVP. Some literature suggests that when people strength rather than a weakness for firms, albeit for differ-

encounter unidentified others, they infer little commonality ent reasons than those Dholakia and Vianello (2009) pro-

with them. Sassenberg and Postmes (2002), for example, pose. We base our prediction in the idea that individuals

show that when people know nothing about other group tend to be particularly sensitive to incidental similarities

members, they report low levels of liking and low percep- between themselves and others, showing more positive atti-

tions of group cohesiveness. These authors ground their tudes toward a product in the presence of even superficial

findings in social categorization theory (Turner et al. 1987), similarities (e.g., Jiang et al. 2010). Furthermore, work on

which argues that individuals who cannot be placed in a the self-referencing effect shows the positive effect of self-

Beyond the “Like” Button / 107

relatedness for information processing (e.g., Perkins, Fore- hypothesis). Study 3 introduces our theorizing regarding the

hand, and Greenwald 2005), such that individuals show moderating effect of joint and single evaluation contexts

enhanced attention and cognitive fluency for information and replicates results related to H1a and H1c.

perceived as self-congruent. If such effects hold in a social

media context, individuals will be more influenced by the

presence of even a small number of individuals in an MVP

Study 1a

array who are similar to themselves (i.e., who are directly Study 1a compares participants’ liking for an unfamiliar

self-relevant) than a small number who are dissimilar (and brand when they observe different types of MVP. We use

thus are less self-relevant). Therefore, we anticipate that a age to manipulate similarity given previous work by practi-

consumer viewing a social media site with heterogeneous tioners and academics highlighting the influence of age

MVP will be particularly sensitive to the presence of the similarity on product preferences. For example, the

similar individual(s) in the array. In turn, brand evaluations Yankelovich report on generational marketing argues that

will be equivalent to those formed when consumers are determinants of product value are strongly influenced by

exposed to similar MVP. Notably, given that we hypothe- age cohort, shared experiences, media icons, and life stage

(Smith and Clurman 2009). Previous academic studies have

size that ambiguous MVP will create brand evaluations like

argued that other demographic characteristics drive attrac-

those created by similar MVP, heterogeneous and ambigu-

tion between consumers, but note that age is likely to be

ous MVP should also produce equivalent brand evaluations.

correlated with many of these characteristics. For example,

A question that remains, however, is how much similar-

Byrne (1971) finds that shared job classification and marital

ity must be present in a heterogeneous MVP array for it to

status make television media attractive to consumers. Simi-

generate inferences and evaluations like homogenous simi-

larly, Shachar and Emerson (2000) find that individuals

lar MVP. Note that in Asch’s classic work on conformity

who have families prefer watching shows about families.

(Asch 1955, 1956), social influence effects can be gener-

These characteristics are likely to be shared within at least

ated by even a small number of individuals in a larger broad age ranges, such that college students will differ from

group. That is, homogeneity among confederates was not people 30–40 years of age, who will again differ from

necessary to prompt study participants to alter their judg- people older than 65 years. Thus, perceived age of the indi-

ments of stimuli. Thus, while there is no theory to directly viduals in an MVP array may act as a proxy for numerous

guide predictions about heterogeneity in the social media other demographic characteristics that have been shown to

context, we propose that even a small proportion of similar influence similarity-based attraction.

individuals in a heterogeneous MVP array may produce

evaluations like those produced by homogeneous similar Stimuli and Procedure

MVP. To test this, we empirically manipulate number of A total of 128 undergraduate students participating in this

similar individuals in an MVP array to range from zero (dis- study in exchange for extra credit were told that they would

similar MVP) to 100% (similar MVP). be viewing an excerpt from the Facebook fan page created

Thus, we suggest that MVP will influence brand evalua- by Roots, a Canadian clothing company. Participants read

tions as follows: the following information:

H1: Ambiguous MVP produces (a) equivalent brand evalua- In this section of today’s study, we’d like to you to look at

tions to homogeneous similar MVP, (b) equivalent brand excerpts from an actual Facebook page for a real brand.

evaluations to heterogeneous MVP, and (c) significantly This is the type of page where you can “become a fan” of

more positive brand evaluations than homogeneous dis- a company or brand.3 You will see excerpts from a page

similar MVP. maintained by Roots, a real Canadian company interested

H2: The relationship proposed between MVP composition and in expanding to the United States. Please look at the infor-

brand evaluations in H1c is mediated by inferences of mation featured on their Facebook page and respond to

commonality with the brand’s user base.2 the questions as honestly as possible.

We first test these hypotheses across three studies Participants then viewed an excerpt from a simulated

employing different operationalizations of ambiguous MVP Roots Facebook page (see the Web Appendix at www.

and similarity. Study 1a tests all parts of H1 using age to marketingpower.com/jm_webappendix) and answered ques-

manipulate similarity. Study 1b tests the parts of H1 pertain- tions about Roots clothing. As discussed previously, we

ing to ambiguity, similarity, and dissimilarity using gender operationalized similarity using perceived age, holding gen-

to manipulate similarity. Then, given that Study 1 leaves der constant. Participants indicated their gender before the

unanswered questions about heterogeneity, Study 2 focuses study began so that all participants viewed fans matched to

primarily on heterogeneity, providing a direct test of H1b. their gender. All participants were told that there were the

Studies 1b and 2 both include tests of H2 (the mediation same number of total fans regardless of MVP condition.

Depending on condition, participants saw one of the follow-

ing: (1) total number of fans and pictures of six fans that

2Note that because H and H predict equivalence, a media-

1a 1b

tion test would not be able to explain variance in the dependent

measure for these hypotheses. Thus, H2 predicts that ambiguous 3At the time we began this research, Facebook called brand sup-

MVP leads to a higher level of inferred commonality than does porters “fans” and brand pages “fan pages.” The term “fan” has

dissimilar MVP, which explains the difference in brand evalua- since been replaced by the “like” button; consumers who were

tions between these types of MVP predicted in H1c. fans of a brand are now those that like the brand.

108 / Journal of Marketing, November 2012

were the same age and gender as the participant4 (homoge- erogeneous MVP [H1b], and [3] ambiguous MVP vs. dis-

neous similar MVP condition), (2) total number of fans and similar MVP [H1c]). This analysis thus indicates the effect

pictures of six fans that were the same gender but a different of the managerial decision to reveal consumers’ similar or

age than the participant (homogeneous dissimilar MVP con- different demographic information to one another or to

dition), (3) total number of fans and three pictures of fans obscure it, maintaining ambiguity. Note that these contrast

that were the same gender and age and three pictures of fans codes partition the multivariate analysis of variance sums of

that were the same gender but a different age (heterogeneous squares into interpretable subsets, obviating the need for

MVP condition) as the participant, or (4) no fan pictures, special alpha levels (Rosenthal, Rosnow, and Rubin 2000).

only the total number of fans (ambiguous MVP condition). Consistent with our hypotheses, only the contrast code

No specific direction was given to attend to the fans, and comparing the ambiguous MVP condition with the dissimi-

participants viewed the page as long as they liked. Other lar MVP condition was significant. There was no significant

information on the page was held constant across conditions. difference in liking between the similar (M = 4.74) and

We captured brand liking by asking, “Based on the ambiguous (M = 4.48) MVP conditions (F(1, 107) = .86, p =

information you just saw from their Facebook page, how .36) or between the heterogeneous (M = 4.89) and ambigu-

much do you like Roots brand clothing?” on a nine-point ous MVP conditions (F(1, 107) = 1.91, p = .17), in support

scale ranging from “do not like at all” to “like very much.” of H1a and H1b, respectively. We also note that there were

As manipulation checks, we asked participants in the simi- no differences in brand liking in the similar, heterogeneous,

lar, dissimilar, and heterogeneous MVP conditions to indi- and ambiguous conditions when these conditions were con-

cate how much they agreed that “Roots ‘fans’ are the same sidered together in a separate analysis (F(2, 82) = .38, p =

age I am” and “Roots ‘fans’ are the same gender I am.” .68). As H1c predicts, the only one of the three contrast

Finally, we asked all participants whether they had heard of codes that was significant was the one comparing ambigu-

Roots before the study and, if so, how familiar they were ous MVP with dissimilar MVP: Participants liked Roots

with the brand on a nine-point scale (1 = “not at all famil- significantly less in the dissimilar (M = 3.81) than the

iar,” and 9 = “very familiar”). ambiguous (F(1, 107) = 5.04, p < .05) MVP condition.5

Results Discussion

Sample and manipulation check. We first examined par- The result of Study 1a suggest that fans on a social net-

ticipants’ familiarity with Roots. Of the 128 participants, 27 working site do not need to directly interact with a target

had heard of Roots before the study. Of these participants, consumer or post comments about a brand to influence the

15 indicated a familiarity score of five or above on the nine- brand evaluations of a consumer new to the brand. Specifi-

point familiarity scale, and therefore we removed them cally, MVP evokes equivalent levels of liking when it is

from the data set. Of the remaining participants, two indi- composed of a homogeneous group of similar individuals,

cated that Roots fans were not the same gender they were when it is composed of a heterogeneous group of dissimilar

(presumably because they did not follow instructions and and similar individuals, and when brand supporters are left

indicated a different gender than their own before the begin- demographically ambiguous. In contrast, a homogenous

ning of the study); they were also removed from the data group of dissimilar others produced significantly less brand

set. This left a final usable sample of 111 participants (59 liking. Thus, H1 is supported in this context.

men and 52 women) with an average age of 21 years. The

manipulation check revealed that participants in the similar

condition rated the fans as more similar to themselves in

Study 1b

age (M = 7.81) than did participants in the heterogeneous It is possible that part of the reason that ambiguity was

(M = 5.11) and dissimilar conditions (M = 1.12; F(2, 81) = treated like similarity in Study 1a was because the numeric

147.76, p < .0001). We also note that there were no differ- representation of fans in the ambiguous condition made it

ences in amount of time spent viewing the page across con- difficult for consumers to consider the possibility that these

ditions (M = 26.7 seconds; F(3, 107) = 1.13, p = .34). fans are different from themselves. It is also possible that

the results we obtained could be unique to using age to

Liking for Roots clothing. We next examined partici- manipulate similarity. Therefore, in Study 1b, we tested

pants’ liking for Roots clothing. Because MVP composition whether our results hold using a different type of ambiguity

was a four-level variable, we used three orthogonal contrast (i.e., generic Facebook profile picture silhouettes) and when

codes to compare the ambiguous condition with the other manipulating (dis)similarity using participants’ gender

three conditions (i.e., these codes compared [1] ambiguous

MVP vs. similar MVP [H1a], [2] ambiguous MVP vs. het- 5We also analyzed these data using an alternate set of contrast

codes comparing (1) the similar, ambiguous, and heterogeneous

4Because all participants in the subject pool at the university MVP conditions with the dissimilar MVP condition; (2) the simi-

where the studies were conducted were in their late teens to early lar and ambiguous MVP conditions with the heterogeneous MVP

20s, the fans used in the similar condition were also in this age condition; and (3) the ambiguous and similar MVP conditions

range. All fans in the dissimilar age condition were older, ranging with each other. Consistent with our hypotheses, only the first of

from their 30s to their 60s. All pictures used were actual Facebook these alternate contrast codes had a significant effect on brand lik-

profile pictures selected from the Facebook pages of individuals ing: Roots was liked significantly less in the dissimilar than in the

whose profile picture was public. We note that these pictures other conditions (F(1, 107) = 5.04, p < .05); the other two contrast

manipulate perceived age, not objective age. codes had a nonsignificant effect on liking (both ps >.40).

Beyond the “Like” Button / 109

(holding age constant). We also test our findings by altering answered the same questions about their familiarity with

MVP through “fans of the day,” an approach currently used Roots used in Study 1a.

both on Facebook and on the social portions of some

brands’ own websites (e.g., the “Fan of the Month” featured Results

on Blackberry’s blog). Sample and manipulation check. Of the 116 undergrad-

uate students who participated in this study, 25 had heard of

Stimuli and Procedure

Roots before the study. Of these participants, we removed 4

Study 1b once again asked participants about Roots brand from the data set because they reported being highly famil-

clothing. All participants therefore first read the following: iar with the brand. This left a final usable sample of 112

As part of its social networking strategy, in addition to a participants (53 men, 59 women) with an average age of 21

Facebook page, a Twitter account, and a blog, Roots also years. All participants in the similar MVP condition indi-

invites consumers to post photos of themselves to the cated that the fans of the day were the same gender they

main Roots website where they can be featured as “fans of were, and all participants in the dissimilar MVP condition

the day.” indicated that the fans of the day were the opposite gender.

Participants then saw a screenshot of what was purportedly We also note that there were no differences in amount of

the “Community” section of the Roots website, which fea- time spent viewing the page across conditions (M = 35.6

tured six fans of the day (see the Web Appendix at www. seconds; F(2, 107) = 1.01, p = .37).

marketingpower.com/jm_webappendix). We held all ele- Brand liking and willingness to interact with the brand

ments constant except the photos of the fans of the day.6 This through social media. Given that the independent variable in

study included three between-subjects conditions. Partici- this study had three levels, we used two orthogonal contrast

pants in the ambiguous MVP condition saw six photos of the codes (no special alpha levels required) to analyze the data

anonymous Facebook silhouettes shown when someone does comparing (1) the ambiguous and similar MVP conditions

not provide or make public a profile picture. Participants in with each other (H1a) and (2) the ambiguous with the dis-

the similar MVP condition saw six photos of individuals similar MVP condition (H1c). We analyzed brand liking and

who were the same age and gender that they were, while willingness to interact with the brand through social media

participants in the dissimilar MVP condition saw six photos separately. Again, consistent with H1a, participants in the

of individuals who were the same age but opposite gender. ambiguous (M = 4.16) and similar (M = 3.91) MVP condi-

After participants viewed the Roots website informa- tions expressed equivalent liking for Roots (F(1, 109) = .14,

tion, they indicated their level of agreement with the fol- p = .71). Furthermore, consistent with H1c, participants in the

lowing statement on a seven-point scale: “Roots is a brand dissimilar MVP condition (M = 3.46) liked Roots marginally

for me.” Next, they answered the question “How likely are less than participants in the ambiguous MVP condition (F(1,

you to join the Roots community so that you can have a 109) = 3.75, p = .06). The results for willingness to interact

chance to be featured as one of the ‘fans of the day’?” To with Roots through social media are similar. Participants

capture inferred commonality to test our mediation hypoth- reported that they were equally likely to interact with the

esis, we also asked all participants how much they agreed brand in the ambiguous (M = 2.63) and similar (M = 2.57)

that “I have a lot in common with the typical Roots shop- MVP conditions (F(1, 108) = .90, p = .35) and more likely to

per.” As a manipulation check, participants in the similar join the Roots community in the ambiguous than the dissim-

and dissimilar MVP conditions also indicated (yes/no) ilar (M = 1.97) MVP condition (F(1, 108) = 4.50, p < .05).7

whether the fans of the day were the same gender they Mediation. Using the same contrast codes, we examined

were. Given that it could be argued that by manipulating whether consumers’ inferences that they had “a lot in com-

age in Study 1a, we also inadvertently manipulated attrac- mon with the typical Roots shopper” followed the same pat-

tiveness, we also measured perceived attractiveness to rule tern, as H2 predicted. As we expected, participants reported

out this alternative explanation using the question, “Com- that they had the same amount of commonality with the

pared to the average person of their age and gender, how typical Roots shopper in the ambiguous and similar MVP

attractive were the Roots ‘fans of the day’?” (1 = “signifi- conditions (Mambiguous = 4.29, Msimilar = 3.85; F(1, 109) =

cantly less attractive than average,” and 7 = “significantly

more attractive than average”). Finally, all participants 7We also conducted an alternate analysis of these data using two

contrast codes that compare (1) the similar and ambiguous MVP

6The stimuli for this study were adapted from the Roots web- conditions with the dissimilar condition and (2) the similar and

site, which does feature a “Community” section (though this sec- ambiguous MVP conditions with each other. The results revealed

tion does not actually include fans of the day). We note that the that the brand was liked marginally more in the similar and

fans of the day are not actual Roots users, however, and that Roots ambiguous MVP conditions than in the dissimilar MVP condition

does currently sell clothing in the United States. We found the (F(1, 109) = 3.75, p = .06) and was liked equally well in the simi-

photos of purported Roots fans by searching various websites on lar and ambiguous MVP conditions (F(1, 109) = 2.37, p = .13).

which consumers had posted public photos of themselves (e.g., Participants were also more likely to want to connect with the

Facebook, HotorNot.com). Because all participants in the subject brand through social media in the similar and ambiguous MVP

pool at the university where the studies were conducted are in their conditions than in the dissimilar MVP condition (F(1, 109) = 4.50,

late teens to early 20s and we held age constant in this study, all p < .05) and were equally likely to want to connect with the brand in

photos used depicted people who would be perceived to be in this the similar and ambiguous MVP conditions (F(1, 109) = 1.40, p =

age range. .24).

110 / Journal of Marketing, November 2012

.05, p = .82) and more in common with the typical Roots ity in this format would be driven by consumers who have

shopper in the ambiguous than in the dissimilar MVP con- chosen not to upload pictures to their social media profile.

dition (Mdissimilar = 3.29; F(1, 109) = 7.45, p < .01). Thus, this study suggests that if firms choose to select fans

To explore whether inferred commonality mediated the of the day, they can strategically choose to select or avoid

relationship between the ambiguous versus dissimilar MVP individuals who have opted to maintain their privacy.

contrast code and liking for Roots clothing, we used a boot- Studies 1a and 1b provide support for H1 using two dif-

strapping method (Preacher and Hayes 2008; Zhao, Lynch, ferent manipulations of similarity (age and gender, respec-

and Chen 2010). A confidence interval (CI) that excludes tively). These findings suggest that our results will be

zero for the indirect effect reveals that inferred commonal- usable by a marketer who may only have access to either

ity with the typical Roots shopper mediates the relationship age or gender information based on consumers’ past search-

between the ambiguous versus dissimilar MVP contrast ing behavior or information provided by a social media

code and liking (95% CI [–.72, –.12]), consistent with H2. platform. We would anticipate that in some product cate-

Given that we used photographs to manipulate MVP, it gories, the similarity-enhancing effect of gender and age

is possible that our results could be driven by the perceived could be additive. That is, participants might infer greater

attractiveness of the specific fans shown, not perceptions of commonality if they saw the similar MVP of brand support-

how similar the fans are to the participant (attractiveness ers who were both the same age and same gender as them-

and inferred commonality were moderately correlated; r = selves than if they saw brand supporters who match only in

.38, p < .0001). To test whether this was the case, we exam- terms of age or gender. Whether age, gender, or both

ined whether perceived attractiveness mediated the relation- together are most effective at raising inferred commonality

ship between the focal contrast and liking. When attractive- is likely dependent on the type of brands or products con-

ness is the only mediator in the model, it is a significant sumers consider. Clothing is a category in which both fac-

mediator (95% CI [–.38, –.004]). However, when we included tors are clearly important, as shown in these two studies.

both inferred commonality and perceived attractiveness in Further work could identify specific categories for which

the model as mediators, only inferred commonality mediates one demographic factor or another is more central in deter-

the relationship (95% CI [–.74, –.12]). The lower bound of mining inferred commonality.

the CI for perceived attractiveness is negative in this model,

and the upper bound is positive (95% CI [–.05, .17]), indi- Study 2

cating that attractiveness is not a significant mediator. The Although the numbers-only presentation used in Study 1a

results for willingness to interact with the brand through and the fans-of-the-day format used in Study 1b are both

social media are substantively identical. Inferred common- common ways to display MVP, firms also increasingly

ality mediates the relationship between the focal contrast allow consumers to upload pictures of themselves using or

and the dependent variable both when alone in the model wearing a product to social media sites. If such pictures are

(95% CI [–.37, –.05]) and when attractiveness is included in displayed in ways that do not provide complete demo-

the model (95% CI [–.36, –.04]). Attractiveness is a signifi- graphic information, they would also present the consumer

cant mediator when it is the only mediator in the model with a type of ambiguous MVP. Therefore, Study 2

(95% CI [–.37, –.03]) but not when the model also includes explores whether photos that do not reveal all of a sup-

inferred commonality as a mediator (95% CI [–.26, .05]). porter’s demographic characteristics create identical effects

Discussion to those created by revealing only the total number of fans

or showing profile pictures that reveal no demographic

The results of Study 1b provide additional support for H1, information. Study 2 also explores the effect of heteroge-

demonstrating that the results hold across a different opera- neous MVP in greater depth, testing the level of hetero-

tionalization of ambiguity. In support of H2, consumers geneity required to create effects equivalent to those seen

express greater liking for a brand and greater willingness to with similar MVP. A secondary goal of this study was to

interact with that brand through social media when the test whether effects observed in prior studies extend to other

brand displays ambiguous or similar MVP than when the downstream consequences of interest to managers beyond

brand displays dissimilar MVP because of greater inferred brand liking and interacting with a brand through social

commonality with the brand’s user base.8 Note that ambigu- media.

8Although not reported in the interests of brevity, we collected Stimuli and Procedure

additional data in which we measured inferred commonality before Study 2 asked participants to react to an online clothing

brand evaluations. The results suggest that the effect of dissimilar retailer called asos:

MVP does not change regardless of whether it is made salient

before brand evaluation questions are asked (F(1, 210) = 6.95, p < In this survey, we are interested in your opinions about a

.01). As such, it appears that the effects of dissimilar and ambigu- real brand’s social networking presence. This brand, asos,

ous MVP on brand evaluations are likely to be obtained either is an online clothing retailer that sells both men’s and

below or above the radar. However, when individuals are cued to women’s clothing mostly in the U.K. As part of its social

notice similar MVP, they appear to discount it when forming networking strategy, in addition to a Facebook page and a

brand evaluations (F(1, 210) = 4.50, p < .05). We would attribute Twitter account, asos also hosts “asos marketplace” on its

this to the possibility that drawing attention to homogeneous simi- company-owned website. Visitors to the website are

lar MVP activates persuasion knowledge, such that consumers try invited to join asos marketplace and to post photos of

to avoid being manipulated by the individuals presented. themselves wearing asos brand clothing.

Beyond the “Like” Button / 111

Participants then saw a screen shot of what was purportedly Finally, all participants were asked whether they had heard

the splash page Internet users would find if they went to of asos before the study and, if yes, how familiar they were

www.asos.com. They then viewed the “Marketplace” sec- with the brand on a seven-point scale (1 = “not at all famil-

tion of the asos website, which featured user-posted photos iar,” and 7 = “very familiar”).

of brand users wearing asos clothing (see the Web Appen-

dix at www.marketingpower.com/jm_webappendix). We Results

manipulated photos to create the different types of MVP, Sample and manipulation check. Of the 289 undergrad-

such that everything on the website was held constant uate students who participated in this study for extra credit,

except the user-posted photos.9 Participants indicated their 17 had heard of asos before the study. All 17 indicated a

gender before the main study began so that all participants familiarity score of four or greater on the seven-point famil-

viewed members of the asos marketplace who were iarity scale, and therefore we removed them from the data

matched to their own gender. We manipulated similarity set. Of the remaining participants, 12 indicated that the asos

using perceived age, as in Study 1a. marketplace users were not the same gender they were (pre-

Study 2 had eight between-subjects conditions in which sumably because they did not follow instructions and indi-

participants saw six photos of brand users. The number of cated a different gender than their own before the beginning

similar brand users ranged from zero of six (homogeneous of the study) and were also removed from the data set. This

dissimilar MVP) to six of six (homogeneous similar MVP) left a final usable sample of 260 participants (151 men, 109

in seven of the conditions. The eighth condition displayed women) with an average age of 21 years. The age similarity

six photos of brand users that showed only their clothing, manipulation check revealed that participants in the similar

not their faces (ambiguous MVP condition). MVP condition rated the asos marketplace members as more

After participants viewed the asos website information, similar to themselves in age (M6 similar, 0 dissimilar = 5.18) than

they responded to the following three questions on seven- did participants in the heterogeneous (M5 similar, 1 dissimilar =

point scales (1 = “very unlikely,” and 7 = “very likely”): 4.07, M4 similar, 2 dissimilar = 3.74, M3 similar, 3 dissimilar = 3.75,

“How likely would you be to buy asos clothing if it were M2 similar, 4 dissimilar = 2.74, M1 similar, 5 dissimilar = 2.38) and

available in the U.S.?” “Recently, asos has been considering dissimilar MVP conditions (M0 similar, 6 dissimilar = 1.88; F(6,

opening retail stores in addition to selling clothes online…. 233) = 23.71, p < .0001).

How likely would you be to shop at an asos store if one

opened in your area?” and “If asos sent you a coupon to use Purchase intentions. Because the three purchase inten-

in-store (for 20% off your total in-store purchase) to your tion measures were highly correlated ( = .90), we aver-

home mailing address, how likely would you be to use that aged them to form an overall purchase intention index. Our

coupon?” We captured inferred commonality through analysis uses seven contrast codes that compare purchase

agreement (on a seven-point scale) with the statement, “I intentions in the ambiguous MVP condition with every

have a lot in common with the typical asos shopper.” other condition (with no need for special alpha levels

As a manipulation check, participants in the similar and because the codes are orthogonal). Consistent with H1a and

dissimilar MVP conditions rated how much they agreed that H1b, none of the contrasts comparing ambiguous MVP with

“The asos marketplace users are the same age I am” and the homogeneous similar MVP condition or any of the het-

indicated (yes/no) whether the users were the same gender erogeneous conditions were significant (all ps > .24). The

they were. Participants in all conditions responded to the only significant contrast (of the seven contrast codes com-

question “Compared to other people in their age group, how paring the ambiguous MVP condition with every other con-

attractive were the asos marketplace users?” on a seven- dition) was the contrast code comparing the ambiguous

point scale anchored by “significantly less attractive than MVP condition directly with the homogeneous dissimilar

average” and “significantly more attractive than average.” MVP condition. Consistent with H1c, participants in the dis-

similar MVP condition were less likely to buy asos clothing

9We adapted the stimuli for this study from the asos website. We (M = 3.60) than participants in the ambiguous MVP condi-

note that the users shown are not actual asos users, however, and tion (M = 4.60; F(1, 249) = 6.84, p < .01).10

that asos does currently sell clothing in the United States. We To learn more about the effect of different levels of

selected asos for this study because of its user-posted marketplace heterogeneity, we conducted follow-up analyses comparing

photo section and because it was unfamiliar to the majority of the the heterogeneous MVP arrays that contained the fewest

subject pool at the university where the study was conducted. We

found the photos of purported asos users through a Google image number of dissimilar individuals with the homogeneous dis-

search (thus, photos came from a variety of different websites similar MVP array. We found that one similar individual in

where people had posted public photos of themselves, including the MVP array was not enough to create purchase intentions

Burberry’s Art of the Trench website) and Facebook brand pages significantly different from those generated by a homoge-

where users had posted photos of themselves wearing a particular neous dissimilar MVP array (F(1, 65) = 1.29, p = .26).

clothing brand (e.g., Talbots), so the clothing used was not actu- However, when two of the six displayed individuals were

ally asos clothing. As in Study 1a, because all participants in the

subject pool at the university where the studies were conducted

were in their late teens to early 20s, the photos used in the similar 10In a separate analysis (excluding the dissimilar MVP condi-

condition depicted people who would also be perceived to be in tion), we also tested for differences across the homogeneous simi-

this age range. The purported asos users in the dissimilar age con- lar and all heterogeneous MVP conditions. This omnibus analysis

dition were older, with perceived ages ranging from their 40s to revealed that there were no differences in purchase likelihood

their 70s. across these seven conditions (F(6, 228) = .77, p = .60).

112 / Journal of Marketing, November 2012

similar to the participant, purchase intentions were greater Study 2’s results also indicate that consumers may

than for a dissimilar only MVP array (F(1, 64) = 3.75, p = respond to heterogeneous MVP in the same way they do to

.06). Further analysis demonstrates the incremental impact ambiguous and homogeneous similar MVP. Exposure to

of adding an additional similar individual to the mix using two or more similar individuals in a set leads to purchase

regression. This analysis revealed a significant linear (b = intention levels not significantly different from ambiguous

.13, t = 2.75, p < .01), not curvilinear (b = –.03, t = –1.18, p = or homogenous similar MVP. We suspect, however, that the

.24), relationship between the degree of similarity in the raw number of similar individuals in a heterogeneous MVP

MVP array and purchase intentions (see Table 1). array is likely not as important as the proportion of similar

Mediation. Using the same seven contrast codes com- individuals. Would two similar individuals in a heteroge-

paring each condition with the ambiguous MVP condition, neous MVP array of 100 individuals produce equivalent

we next examined whether consumers’ inferences that they levels of brand liking as an ambiguous or homogeneous

had “a lot in common with the typical asos shopper” fol- similar MVP array? We leave identification of the absolute

lowed the same pattern of results found for purchase inten- tipping point to further study but expect that two would

tions. As we expected, the only significant difference was likely not be enough in this context.

again that participants in the dissimilar MVP condition (i.e., Across the three studies reported thus far, we show that

six dissimilar users and zero similar users) perceived lower leaving a brand’s online supporters ambiguous has only

commonality with the typical asos shopper (M = 3.03) than positive consequences. However, Studies 1 and 2’s effects

participants in the ambiguous MVP condition (M = 3.50; were viewed in the context of only one brand’s presence—

F(1, 252) = 3.85, p = .05) (for means, see Table 1). that is, in a separate evaluation context. In many cases, con-

As in Study 1b, we tested both inferred commonality sumers will not evaluate a brand in isolation. Thus, the pre-

and perceived attractiveness (r = .34, p < .0001) of the asos scription to maintain ambiguity may need to be tempered

marketplace users as potential mediators of purchase inten- for firms that face a more rather than less competitive

tions using a bootstrapping method (Preacher and Hayes space.

2008; Zhao, Lynch, and Chen 2010). The results reveal that Therefore, Study 3 examines whether our effects hold in

inferred commonality with the typical asos shopper mediates a joint evaluation context more similar to the experience a

the relationship between the contrast code comparing the consumer is likely to actually have on a social networking

dissimilar MVP condition with the ambiguous MVP condition site. In previous research on interpretation of ambiguous

(95% CI [.09, .72]). In contrast, when we tested attractive- others, Naylor, Lamberton, and Norton (2011) showed par-

ness as a mediator, the lower bound of the CI is negative, and ticipants a set of different, verbally described reviewers

the upper bound is positive (95% CI [–.07, .34]), indicating (varying in identification and similarity) providing input

that perceived attractiveness is not a significant mediator. about different products. In this setup, they found that an

When we included both potential mediators in the model, ambiguous reviewer was slightly less persuasive than a

inferred commonality remains a significant mediator (95% similar reviewer. This result diverged somewhat from find-

CI [.10, .69]), and perceived attractiveness does not (95% ings in their other studies, in which participants viewed

CI [–.03, .15]). only one reviewer, leaving an explanation for this “cost of

ambiguity” for further research. We propose that whether

Discussion ambiguous MVP creates liking equivalent to or less than

Study 2 demonstrates that the brand liking effects in Studies that created by similar MVP will depend on whether a

1a and 1b extend to purchase intentions and are consistently brand is evaluated alone (i.e., no competing brands or their

mediated by inferred commonality with the brand’s users. supporters are viewed) or evaluated at the same time as

These results hold when manipulating ambiguity by showing other competing brands. From a practical standpoint, con-

photos that concealed key demographic characteristics. We sumers may view only one brand’s Facebook page (or the

note that this is a more conservative test of our hypotheses social component of only one brand’s website) in a category

than that in Study 1a or 1b, given that the photos used in Study with little direct competition or may view many brands’

2 conceal some, but not all, demographic characteristics. pages in a densely populated space.

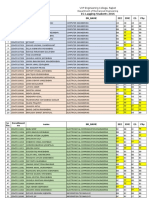

TABLE 1

Study 2: Means by MVP Composition

Mean Rating of How Much

Mean Purchase Intention in Common Participant Has

Condition MVP Composition (Indexed Variable) with Typical asos Shopper

1 6 ambiguous users 4.61 3.63

2 6 similar, 0 dissimilar users 4.38 3.94

3 5 similar, 1 dissimilar user 4.48 3.75

4 4 similar, 2 dissimilar users 4.25 3.49

5 3 similar, 3 similar users 4.21 3.35

6 2 similar, 4 dissimilar users 4.23 3.45

7 1 similar, 5 dissimilar users 3.96 3.21

8 0 similar, 6 dissimilar users 3.54 3.00

Beyond the “Like” Button / 113

Viewing multiple competing brands at the same time tioned in the separate evaluation condition]. You will see

can be characterized as a case of joint evaluation, whereas some of the material that appears on the first page of each

single brand viewing can be characterized as separate restaurant’s social networking site. After potential users

see this information, they can create an account to join a

evaluation (Hsee et al. 1999; Hsee and Leclerc 1998). Pre- restaurant’s site, which lets them post information that

vious research has shown that people evaluate options dif- other users can see, including comments and photographs.

ferently in these two decision contexts, such that products

that are evaluated highly under separate evaluation may be Participants in the joint evaluation condition were told that

evaluated less positively under joint evaluation (Hsee and the first pages of all three social networking sites that they

Leclerc 1998). This is because when an objectively attrac- would observe featured a “welcome” to the site, pho-

tive product is evaluated singly, consumers rely on an inter- tographs of the restaurant, and photographs of members of

nal reference point to evaluate it. In contrast, when that tar- the restaurant’s site. Participants in this condition were then

get product is evaluated alongside another objectively shown the first page of the three restaurants’ sites with the

attractive product, consumers shift away from their internal pictures of five website members varying such that one

reference point. Instead, consumers focus more on the other restaurant featured members similar to the subject pool,11

product, rather than an internal source, as a reference point one featured dissimilar members, and one featured ambigu-

(Hsee and Leclerc 1998). ous members (using the same anonymous Facebook silhou-

In the present context, consider separate evaluation of a ettes used in Study 1b). We rotated the order of type of

brand with ambiguous MVP. We have argued that this brand member featured for each restaurant such that there were

will be evaluated positively because consumers infer that actually three joint evaluation conditions that differed only

ambiguous others are like themselves. Now imagine that by order. (In all conditions, participants saw three restau-

the same brand is viewed alongside a brand with similar rants, one with similar, one with ambiguous, and one with

MVP. Rather than focusing exclusively on egocentric dissimilar members.) Participants in the joint evaluation

anchor-driven inferences of similarity, the consumer com- conditions rated the restaurants sequentially.

pares the ambiguous MVP directly with the similar MVP of In contrast, participants in the separate evaluation con-

the other brand. When ambiguity is directly compared with dition saw information about only one restaurant, which

similarity, the consumer will still infer commonality with the was manipulated between subjects to display similar, dis-

ambiguous MVP brand’s user base, but this inferred infor- similar, or ambiguous MVP. Participants in all conditions

mation is likely to be weaker than the information observed were asked, “How much do you think you’d like the bar

when demographic similarity is displayed. Thus, in joint area at [restaurant name]?” (for each restaurant they saw)

evaluation contexts, we predict that consumers will have on a nine-point scale (1 = “would not like at all,” and 9 =

higher evaluations of a brand about which commonality is “would like very much”).

more strongly indicated by the similar MVP displayed than

Results

a brand about which they have to make an inference (i.e., a

brand whose supporters constitute ambiguous MVP), even Separate evaluation. We first assessed whether our pre-

if the egocentric-anchoring-driven inference would have, dictions held in the separate evaluation conditions using

under separate evaluation, led to equivalent levels of liking two contrast codes that compare (1) the ambiguous and

for the brands with ambiguous and similar MVP. Formally, similar MVP conditions with each other and (2) the

ambiguous with the dissimilar MVP condition. When we

H3: In a joint evaluation context, ambiguous MVP creates

brand evaluations that are less positive than those gener- regressed the liking variable on the two contrast codes, we

ated by homogeneous, similar MVP but more positive again observed support for H1a, as the bar area was liked

than those generated by homogeneous, dissimilar MVP. equally well in the similar (M = 5.78) and ambiguous MVP

conditions (M = 5.92; F(1, 144) = .55, p = .46). That is, as

in Studies 1 and 2, there is no cost to ambiguity relative to

Study 3 similarity in a separate evaluation context. Consistent with

Study 3 tests our hypothesis that the effect of ambiguity H1c and the results of the prior studies, participants liked the

depends on the evaluation context in which a brand is bar area more in the ambiguous MVP condition than in the

viewed. In addition, Study 3 shows that the results from dissimilar (M = 5.18) MVP condition (F(1, 144) = 4.77, p <

Studies 1 and 2 replicate in a different product category and .05).12

in an additional social networking context.

11Member pictures used were the same used in Study 1a. Par-

Stimuli and Procedure

ticipants were again asked their gender before the study began so

A total of 312 undergraduate students (178 men, 134 that the fans shown matched their gender. We manipulated similar-

women) with a mean age of 21 years participated in this ity using perceived age.

study for course credit. All participants read the following 12We also conducted an alternate analysis using two contrast

introduction: codes that compare (1) the similar and ambiguous MVP conditions

with the dissimilar condition and (2) the similar and ambiguous

Now we’d like to you to look at some social networking MVP conditions with each other. The results revealed that partici-

websites developed by restaurants with locations nation- pants liked the bar area more in the similar and ambiguous MVP

wide. To protect confidentiality, the names of the restau- conditions than in the dissimilar MVP condition (F(1, 109) = 5.24,

rants have been changed to Restaurants X, Y, and Z [in the p < .05) and equally well in the similar and ambiguous MVP con-

joint evaluation condition; only Restaurant X was men- ditions (F(1, 109) = .06, p = .81).

114 / Journal of Marketing, November 2012

Joint evaluation. An omnibus repeated measures analy- Galak 2012). The present work shows how mini-connections

sis of all three conditions revealed that there was not a sig- with consumers created through social networking can

nificant between-subjects effect of order (in which the indeed yield positive effects on brand evaluations and pur-

restaurants were viewed) on brand liking, so we dropped chase intentions. A central proposition of our research is

order from further analysis (F(1, 163) = .65, p = .42).13 We that the decision to reveal a brand’s fan base or to leave

then used within-subject contrast codes analogous to the supporters’ identities ambiguous is important because the

ones used in the separate evaluation analysis to analyze par- demographic composition of the MVP presented affects

ticipants’ liking for the three restaurants. Consistent with H3 consumers’ reactions to the brand.

and diverging from H1a, participants liked the bar area in the Importantly, the effects of revealing the identities of a

restaurant with similar MVP (M = 5.97) significantly more brands’ fan base vary depending on the demographic com-

than the bar area in the restaurant with ambiguous MVP (M = position of the individuals presented. In Study 1a, we

5.34; F(1, 164) = 13.22, p < .001), showing a cost of ambi- demonstrate that consumers respond as positively to a

guity relative to known similarity. However, even under brand when the brand’s supporters remain ambiguous

joint evaluation, ambiguity is still preferable to dissimilarity: (because no photos of supporters are displayed) as they do

Participants anticipated liking the bar area in the restaurant when the brand reveals the identity of supporters that the

with ambiguous MVP more than the bar area in the restau- consumer perceives to be similar to the self. Consumers

rant with dissimilar MVP (M = 4.39; F(1, 164) = 30.01, p < also respond as positively to the display of a heterogeneous

.0001).14 group of similar and dissimilar brand supporters as they do

to an ambiguously presented group. Importantly, ambigu-

Discussion ous MVP produces significantly greater brand liking than

Study 3 examines participants’ response to similar versus homogeneous dissimilar MVP. Study 1b replicates these

ambiguous MVP in joint versus separate evaluation con- effects using a different type of ambiguity (i.e., the generic

texts. In separate evaluation, ambiguous MVP leads to an Facebook silhouette profile picture) and a different manipu-

almost identical response to that generated by similar MVP, lation of similarity (gender instead of age).

as in Studies 1 and 2. However, in joint evaluation, ambigu- Perhaps surprisingly for many who assume that trans-

ous MVP leads to a significantly less positive response than parency is key in developing a brand’s social networking

does similar MVP. Still, ambiguous MVP generates liking presence, the results of both Studies 1a and 1b suggest that

greater than that evoked by dissimilar MVP. revealing the identities of a brand’s online supporters may

These findings shed light on the decision managers actually have negative consequences if the brand’s support-

must make about whether to reveal the identity of their ers are homogeneous and dissimilar to the target consumer.

brand’s supporters: The decision must be determined not This may be the case when a brand initially extends into a

just by whether the brand supporters shown are likely to be new target market. In these cases, leaving a brand’s fan base

perceived as similar or dissimilar to a target consumer but ambiguous may be a safer strategy because consumers will

also by whether the consumer is likely to encounter the sup- like the brand as much when supporters are ambiguous as

porters in a joint or separate evaluation context, an issue we when at least some similar supporters are revealed.

return to in the “General Discussion” section. Notwithstanding expectations about the “social” nature of

such platforms, Studies 1a and 1b show no negative conse-

quences of choosing not to reveal the identity of a brand’s

General Discussion supporters.

At the end of 2011, iMedia Connection published an article Study 2 uses a third type of ambiguity (photos of brand

titled “Why Facebook Fans Are Useless” (Lake 2011). In the supporters with key demographic characteristics obscured)

article, the author notes that “on their own, Facebook ‘likes’ and further explicates the impact of heterogeneous MVP,

don’t add any value.” Yet research has shown that social showing that a small proportion of similar supporters can

media can translate into increases in sales (Stephen and create effects like that of ambiguous MVP. This finding

suggests that brands need not fear diversity on social net-

13We also analyzed the joint evaluation data using only each working sites as long as they can anticipate that a target

participant’s rating of the first restaurant they saw. Because par- audience will make up a nontrivial proportion of the group

ticipants viewed the restaurants sequentially, we expected these of supporters shown. Both Studies 1b and 2 also document

results to be consistent with the separate evaluation results. As we that the effects of MVP on brand liking are driven by con-

expected, participants liked the bar area equally well in the similar

sumers’ inferences about how much they have in common

(M = 5.57) and ambiguous MVP conditions (M = 5.88; F(1, 162) =

.90, p = .34) but more in the ambiguous MVP condition than in the with the brand’s supporters.

dissimilar (M = 4.66) MVP condition (F(1, 162) = 10.69, p < .01). While Studies 1 and 2 suggest that ambiguity is the pre-

14The results using the same alternate contrast codes used in the ferred strategy in separate evaluation contexts, Study 3

separate evaluation analysis reveal that participants anticipated shows that in joint evaluation contexts, ambiguity is not as

liking the bar area in the restaurants with similar and ambiguous powerful as similarity in generating brand liking. These

MVP more so than the bar area in the restaurant with dissimilar findings suggest that if the consumer is likely to evaluate a

MVP (F(1, 164) = 63.47, p < .0001). However, in contrast to the

separate evaluation results, they liked the bar area in the restaurant

brand in isolation, ambiguity may be the safest strategy. In

with similar MVP significantly more so than they did the bar area contrast, if the brand is likely to be encountered in a context

in the restaurant with ambiguous MVP (F(1, 164) = 13.22, p < in which it is being compared with multiple other brands,

.001). managers may need to display information about online

Beyond the “Like” Button / 115

supporters, despite the potential risks, to compete with information more positively than those that lack identifying

brands with supporters whose demographic characteristics information. In the same way, our work suggests that some

are displayed. identification information may be better than none, particu-

larly in joint evaluation contexts.

Theoretical Contributions

This work provides several novel theoretical insights. First, How Can This Research Inform Practice?

the concept of MVP offers a new framework for under- To determine how our findings can be used, we should first

standing social influence. Although spatial proximity is note the breadth of applicability for our studies. Note that

absent, exposure is only passive, typically just a handful of we have removed consumers who are extremely familiar

individuals are shown, and no future relationship is likely to with a brand from our analysis and that we focus on brand

exist among the consumers, we show that MVP still has perceptions and purchase intentions as our outcomes of

substantial effects on consumers’ brand evaluations and interest. This makes our findings most applicable to con-

purchase intentions. As such, the concept of MVP high- sumers who are relatively new to a brand and who, at least

lights the ways that online social influence may have an passively, have the goal of forming an opinion about the

effect despite its difference from the offline presence of oth- brands to which they are exposed. This is a substantial seg-

ers and despite its failure to conform to the parameters of ment: Approximately 23.1 million consumers between 13

SIT (Latane 1981). and 80 years of age use social media to discover new brands

Importantly, in contrast to traditional advertising or or products, and 22.5 million people use social media to

spokesperson contexts, we also note that MVP created by learn about unfamiliar brands or products (Knowledge Net-

social media exposure is provided by individuals who vol- works 2011). Thus, our results will be relevant to marketers

untarily affiliate with a brand, making it less likely that seeking to reach this large segment of consumers but may

their action will be discounted by consumers due to reac- not be applicable for marketers of universally known

tance against marketer-driven recommendations (Fitzsi- brands.

mons and Lehmann 2004) or persuasion knowledge (Fries- Our research will also be easiest to use when marketers

tad and Wright 1994). Further research could explore can manipulate their displayed MVP in response to target

whether the effects of MVP hold if consumers do not trust consumer demographics. Emerging tracking and targeting

that the brand supporters presented are truly other con- tools can be used to do this. For example, Facebook ads are

sumers (as opposed to, e.g., employees of the brand “pos- often targeted only to certain demographic groups. In such

ing” as supporters). cases, marketers know that individuals who click on a link

Furthermore, our investigation into consumers’ responses to their social media sites will fit a certain demographic

to ambiguous others may prompt deeper explorations of profile and can adjust MVP accordingly. In other cases,

interpretations of interpersonal ambiguity. In the present consumers who remain logged in to social media sites while

research, we show the equivalence of three types of ambi- browsing other Internet sites may inadvertently provide

guity: that created when (1) MVP is represented only access to age or gender information to the other sites they

numerically, (2) MVP is displayed using silhouette pictures visit. Alternately, forms that have been filled out in one

that suggest real individuals but obscure all their demo- online location can provide information to other sites

graphic characteristics, and (3) MVP is displayed using pic- through stored cookies. Using this information, companies

tures of real supporters that obscure some of their demo- can tailor the MVP that a given consumer encounters when

graphic characteristics. Although these operationalizations he or she visits a brand’s social media page.

of ambiguity appear to have similar effects, further research However, we recognize that this may not always be pos-

may find additional nuances in the concept of ambiguity sible. To help brand managers manage MVP both when

and may actually find that different types of ambiguity have they have granular demographic information about the spe-

variant impacts on consumers. cific consumers visiting their site and when they do not, we

Finally, by directly comparing consumer response to developed a decision framework based on two key factors:

ambiguous others in separate and joint evaluation, we (1) the demographic composition of existing brand support-

explain Naylor, Lamberton, and Norton’s (2011) findings. ers relative to targeted new supporters and (2) whether the

We suggest that the difference in ambiguity’s effects across brand is likely to be evaluated singly or in combination with

evaluation modes stems from the finding that the internally competing brands. This framework (presented in Figure 1)

derived egocentric anchor is the determinant of similarity shows when brands should reveal the identity of their

when ambiguity is encountered in a separate evaluation online supporters and when ambiguity is preferable, and it

mode but that the importance of this internal anchor is highlights cases in which managerial control over MVP