Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Anxiety in the Classroom: Implications for Middle School Teachers

Uploaded by

Paulina ValenciaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Anxiety in the Classroom: Implications for Middle School Teachers

Uploaded by

Paulina ValenciaCopyright:

Available Formats

Anxiety in the classroom: Implications for middle school teachers

Author(s): Kristen Moran

Source: Middle School Journal , October 2015, Vol. 47, No. 1 (October 2015), pp. 27-32

Published by: Association for Middle Level Education (AMLE)

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43958586

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/43958586?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Association for Middle Level Education (AMLE) is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve

and extend access to Middle School Journal

This content downloaded from

181.55.131.99 on Tue, 29 Sep 2020 20:16:01 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Anxiety in the classroom: Implications for

middle school teachers

Krísten Moran

Abstract: Anxiety is a prevalent mental health concern in chil- affect a child's overall ability to concentrate and to learn

dren and adolescents that can have a negative effect on their (Packer 8c Pruitt, 2010), and can impair overall academic

personal relationships as well as their academics. Teachers are performance (Muris 8c Meesters, 2002) . Anxiety disorders

in a position to assist in recognizing the signs of anxiety and may be associated with an overall negative effect on a child's

supporting students in the classroom. Practical suggestions on thinking and ability to make decisions. In addition, anxiety

how teachers can support middle school students with anxiety can disturb an adolescent's ability to build effective rela-

are provided.

tionships with their peers (Packer & Pruitt, 2010).

Most teachers will have at least one student in their

Keywords: anxiety , middle school , teachers ; interventions

classroom with an anxiety disorder (Children's Mental

This We Believe characteristics:

Health Matters, 2009). "Because school plays such a signif-

icant role in adolescents' identity development, teachers

• Educators value young adolescents and are prepared to teach

them are in a unique position to recognize and provide essential

• Comprehensive guidance and support services meet the supports for students. . ." (Johnson, Eva, Johnson, 8c Walker,

needs of young adolescents 2011, p. 10). According to Reinke, Stormont, Herman,

Puri, and Goel (201 1) , in their study involving 292 teachers

• Health and wellness are supported in curricula, school-wide

programs, and related policies from five school districts, "89% of teachers agreed that

schools should be involved in addressing the mental health

According to Cohen (2013), "Schools are more competi-

needs of children" (p. 9). The teachers in their study stated

tive and stressful, children are more overscheduled, par-

they needed additional knowledge, including recognizing

ents are worried about finances and safety, and society is

signs of mental health concerns, and strategies for working

based on a win-lose model..." (p. 2). It is no wonder that

with students exhibiting problems.

anxiety disorders are the most common mental health

disorder in children and adolescents (Children's Mental The purpose of this article is to educate middle level

teachers about anxiety, including the various types of anxiety

Health Matters, 2009; Mychailyszyn, Mendez, 8c Kendall,

disorders that arise in adolescents. In addition, implications

2010; Packer & Pruitt, 2010). The median age of onset for

for middle school teachers' professional practice are shared

anxiety disorders is 11 years old (Kessler et al., 2005),

to increase support for these students in the classroom.

usually developing sometime during adolescence (Packer

8c Pruitt, 2010). Oftentimes, children and adolescents do

not have the life experiences to effectively handle anxiety

experienced with change (Mader, 2012).

Understanding anxiety disorders

According to the Anxiety and Depression Association of Anxiety can be described by using "a simple formula: Add up

America (ADAA; n.d.), research has shown that children all the things that cause us stress, and then subtract all of our

with untreated anxiety disorders have a higher risk of nega- abilities to cope. The net result is our anxiety level" (Cohen,

tive outcomes, such as increased substance use. Anxiety can 2013, p. 2). Although anxiety can be considered a normal

This content downloaded from

181.55.131.99 on Tue, 29 Sep 2020 20:16:01 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

part of childhood and adolescence, anxiety becomes a dis- with peers (ADAA, n.d.). A student's level of worry is often

order when it interferes with functioning in various aspects made worse if others notice or recognize their anxiety

of one's life, such as school and social relationships in chil- (Packer 8c Pruitt, 2010).

dren (ADAA, n.d.). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of

Mental Disorders (DSM-V) categorizes anxiety disorders by, Panic disorder

"the types of objects or situations that induce fear, anxiety, or

In order for a student to be diagnosed with panic disorder,

avoidance behavior, and the associated cognitive ideation"

he/ she must experience at least two unanticipated panic

(American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013, p. 189).

attacks without cause (ADAA, n.d.). A panic attack is "an

Mental health professionals use the DSM-V and the criteria

abrupt surge of intense fear or intense discomfort that

included to diagnose specific anxiety disorders. Although

anxiety in youth does not often present itself as one specific

reaches a peak within minutes" (APA, 2013, p. 208),

accompanied by a variety of symptoms (i.e., sweating,

type of disorder (Kendall et al., 2010), it is important for

dizzy, nausea, chest pain, palpitations) . Because a student

educators to understand potential signs of the disorders. It is

cannot predict a panic attack (Ollendick, 1998), this can

also necessary to recognize there are many characteristics

lead to anxiety about when they might experience the

shared between the different anxiety disorders (APA, 2013).

next attack, making it very difficult to concentrate. Panic

According to Packer and Pruitt (2010), the two most fre-

attacks can cause sheer terror in students, often producing

quent anxiety disorders in middle childhood and adoles-

physical symptoms such as feeling weak, faint, dizzy,

cence are generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and social

chilled, and having a pounding heart. The automatic

anxiety disorder. Other anxiety disorders associated with this

reaction for those that experience panic attacks is the

age are panic disorder and specific phobia (ADAA, n.d.).

need to escape (Packer 8c Pruitt, 2010).

GAD

Specific phobia

GAD manifests itself as a hard-to-control, excessive worry,

about many different aspects in students' lives. According Although children and adolescents may have certain fears

to the DSM-5 (APA, 2013), the type of worries associated as part of normal development, it can become a specific

with GAD can change over time. These students tend to be phobia when they experience this fear for at least 6

perfectionists, doubt their abilities, and seek outside months and do not recognize that this fear is irrational

approval (ADAA, n.d.; Packer & Pruitt, 2010). Although (APA, 2013). A specific phobia is a fear of a specific object

some students with GAD can internalize symptoms of this or a specific situation in which the person will avoid the

anxiety disorder, making it hard to identify (Naparstek, object or situation. For example, a student refusing to

2009), some physical signs that a student is struggling enter a dark room because of a fear of spiders is a specific

include fatigue, headache, muscle tension, lightheaded- phobia. It can be common for a person to have multiple

ness, nausea, and trembling (Packer & Pruitt, 2010). objects or situations that cause fear or anxiety (APA,

Teachers may also note an inability to relax, a lack of 2013). Specific phobias can result in a child or adolescent

concentration (Naparstek, 2009; Packer 8c Pruitt, 2010), experiencing behavioral issues, an inability to follow

and avoidant behaviors (Keeley 8c Storch, 2009). directions, and/or possible social embarrassment from

their peers (Packer 8c Pruitt, 2010).

In his multiple-systems theory of emotion, Lang

Social anxiety disorder

(1968) indicated that symptoms of anxiety can be cate-

This type of anxiety disorder can best be described as a gorized as cognitive, physiological, or behavioral. Table 1

"Marked fear or anxiety about one or more social situa- provides an overview of the type of symptoms typically

tions in which the individual is exposed to possible scru- seen in each of these three areas, despite the type of

tiny by others" (APA, 2013, p. 202). Students with social anxiety disorder.

anxiety tend to appear shy, withdrawn, and avoid eye

contact (Keeley 8c Storch, 2009). Physically they may

experience heart palpitations, sweating, blushing, and Implications for teachers

tremors (Packer 8c Pruitt, 2010). They also have fewer Although it is not the responsibility of teachers to diag-

friendships and relationships due to trouble socializing nose students with anxiety, many roles are appropriate

This content downloaded from

181.55.131.99 on Tue, 29 Sep 2020 20:16:01 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

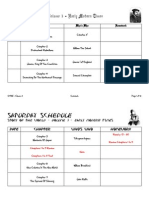

Table 1 Symptoms of Anxiety in the classrooms providing lessons to assist students with

effective skill development in a variety of areas. It would

make sense to provide classroom lessons on anxiety,

■ Cognitive Physiological Behavioral I

H Symptoms Symptoms Symptoms H including education about anxiety, relaxation skills, and

positive self-talk. Mindfulness programs can also assist

H Lack of focus Headaches Avoidance H

H Lack of Stomachaches School refusal H students in managing their symptoms (Wright 8c

H concentration Nausea Classroom disruption H

Sulkowski, 2013).

H Inability to make Heart Trouble developing H

H decisions palpitations relationships H

H Catastrophic Sweatiness Trouble maintaining H

H thinking Dizziness relationships H Intervention

H Fainting Inability to relax H

■ ■ It is known that not all students will respond to the

H Muscle tension H universal prevention efforts of a MTSS within the school

H Insomnia H

(Wright 8c Sulkowski, 2013) and may need additional

H Fatigue H

H Weakness H targeted services. Teacher can more easily observe and

H Trembling H identify potential mental health symptoms because they

H Blushing H interact with students on almost a daily basis (Johnson

et al, 2011). It is important to note that internalizing

symptoms, such as anxiety, can be difficult to detect

(Tomb 8c Hunter, 2004). Teachers should take note of

for teachers in

relation to

the signs and symptoms, students

including which signs they see an

dle school. Many school systems are

in the student, when are they noticing these signs (i.e., u

systems of support (MTSS) to address

specific time of day or particular situation) and where

demic, behavioral, and emotional needs of students

(i.e., classroom, hallway, lunchroom). It is also impor-

(Sulkowski, Wingfield, Jones, & Coulter, 2011). The tant to estimate the length of time the signs are present.

three tiers of MTSS allow for schools to address both

This is not always easy as many students may try to hide

prevention and intervention efforts with students. their anxiety. Lastly, it is important to take note of the

Therefore, implications for teachers will be discussed

intensity of the symptoms (Sink 8c Igleman, 2004).

within this context. Potential classroom accommoda-

Teachers who notice many of the cognitive, physiologi-

tions are shared.

cal, and behavioral symptoms of anxiety should share

concerns with the school counselor (Sink 8c Igleman,

2004).

Prevention School counselors are educated in mental health

issues and are aware of resources available to students who

Teachers can assist in developing prevention efforts in the

schools to minimize the development of anxiety disordersare having symptoms of anxiety. Although school counse-

in students. It makes sense to implement universal pre- lors do not provide long-term therapy to students, they are

able to talk to the student in more depth to find out just

vention programs in the schools since the onset of anxiety

disorders are typically in childhood and adolescence how debilitating their anxiety symptoms are and how it is

(Greenberg, Domitrovich, & Bumbarger, 2001). Theseaffecting their lives. School counselors can work closely

efforts can focus on key areas of "academics, peer rela- with the student and parents to get the appropriate ser-

vices inside and outside of school. Services inside of the

tionships, and social-emotional development" (Tomb &

Hunter, 2004, p. 88) , allowing for the reduction of riskschool may include counseling services or referral to the

student support team. If the services inside the school will

factors that can provide for the manifestation of the dis-

order (Tomb 8c Hunter, 2004). Collaboration with school not meet all of the needs of the student, the school

counselors will allow for the development of these efforts counselor can provide access to outside resources, such as

as they are focused on a comprehensive program that private practitioners and support groups, which can work

addresses prevention for the entire student body. They are with the family and child.

This content downloaded from

181.55.131.99 on Tue, 29 Sep 2020 20:16:01 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Classroom accommodations This pass allows for the student to access a safe person

or safe place for approximately 5-10 minutes in order

According to Dubois, Feiner, Brand, Adan, and Evans

to work through their symptoms. This place and/or

(1992), support by school personnel can have a positive

person must be decided on ahead of time and could

effect on a child's development. Teachers can provide include the school counselor, the nurse's office, a

numerous accommodations within the classroom that will

coach, or an administrator. It can also allow a student

assist and support the student with anxiety. Some strate-

to take a quick bathroom break or get a drink of water.

gies could be part of a formal 504 plan or IEP (indivi-

It is important for the teacher to provide limits if

dualized education plan) if a student has met the criteria.

being misused by the student.

It is also important to note that many of these are inclusive

5. Classroom seating: Where a student with anxiety sits in

strategies that may be beneficial for all students (Mader,

the classroom can provide a reduction in their anxiety

2012), not just those with anxiety. Strategies include the

symptoms. It may be helpful to allow the student to sit

following:

close to the door so if they need to leave the classroom

1. Consistent daily routine: Most students with anxiety they can do so without distracting the class or drawing

will perform best in a classroom that is well organized attention to themselves (WorryWiseKids, n.d.).

with a consistent schedule and clear expectations 6. Test accommodations: A study by Ramirez and Beilock

(Johnson et al., 2011). It is helpful to post the routine (2011) found that students who were able to write

in the classroom and to let students know changes about their fears for approximately 10 minutes prior

ahead of time (Brown, 2010). to taking a high-stakes test were able to reduce their

2. Task-focused environment: Instead of focusing on the worry. In addition, extra time on tests and a quiet

ability of the students within the classroom, which can environment can allow for reduction in overall anxiety

be anxiety producing for some, it can be helpful to (WorryWiseKids.org, n.d.).

have a task-focused environment (Roeser 8c Midgley, 7. Alternative assignments: There may be particular

1997). This type of environment provides for variety in assignments that cause students to feel anxious

learning, challenges students, and assists in determin- depending on the type of anxiety the student is

ing personal goals, ultimately allowing for less compe- experiencing. For example, a student with social

tition between students and an overall more anxiety would have a severe fear of oral presentations.

conducive, respectful environment in the classroom. Providing an alternative assignment would make sense

An example may include allowing students to work in to reduce the anxiety the student may experience.

groups to determine the solution to a problem ratherAlternatives may include providing the presentation to

than working individually, where students are less the teacher individually or allowing the student to

willing to volunteer their answers (Ames, 1992). videotape the presentation and provide to the teacher

3. Group activities: Initiating positive peer interactions for grading. Another example of tasks that could be

can be very beneficial for students with anxiety, espe- anxiety producing may be answering questions out

cially those with social anxiety. By working with care- loud in class or answering questions at the board or

fully selected students for small group activities, the smart board. Letting the student know ahead of time

student feels a connection to others (Emmer & that the teacher may call on them can allow for a

Evertson, 2009; Johnson et al., 2011). Groups assist inreduction in anxiety (WorryWiseKids.org, n.d.).

building their confidence and allow students to 8. Copies of notes: Although copies of notes do not need to

develop relationships (Packer 8c Pruitt, 2010) in a be provided at all times for students that have anxiety, it

more comfortable environment. is comforting to these students to know they will not miss

4. Classroom pass: A permanent pass for a student with material if they do need to leave class because they are

anxiety allows him/her to leave class when they are experiencing symptoms. Notes are also helpful if a stu-

dent is absent from school. Assigning a class buddy (or

having symptoms without drawing attention to them-

friend) to make sure the student receives all of the

selves. According to Packer and Pruitt (2010), "The

ability to make a graceful exit is important to the material can be helpful for the student (WorryWiseKids.

student's self-esteem and peer relationships" (p. 45). org, n.d.). It will be important for the teacher to be

This content downloaded from

181.55.131.99 on Tue, 29 Sep 2020 20:16:01 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

intentional about the student they choose, potentially predicted incidence of adult anxiety (Kendall et al., 2010;

asking the student with anxiety for input. Van Ameringen, Mancini, 8c Farvolden, 2003). As middle

9. Creative activities: These activities allow students to level educators committed to the development and health

of the whole adolescent, this article highlights important

express themselves freely, through writing, art, music,

pathways for professional practice.

and journaling. This provides an opportunity for stu-

dents to individualize their work and for teachers to

connect to their students (Johnson et al., 2011).

References

Creative activities can easily be incorporated into the

curriculum through classroom assignments. American Psychiatric Association (APA). (2013). Diagnostic and statis-

tical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American

10. Positive coping skills: Provide for time in class for Psychiatric Publishing.

students to relax and practice positive coping skills,

Ames, C. (1992). Classrooms: Goals, structures, and student motiva-

tion. Journal of Educational Psychology, 84(3), 261-271.

including using stress balls, listening to soothing music

Anxiety and Depression Association of America (ADAA). (n.d.).

in the background (Gasparovich, 2008), or reading a

Anxiety disorders in children. Retrieved from https://www.adaa.org/

book. Teaching students relaxation activities can be

Brown, S. A. (2010, November 11). Inclusive strategies that benefit the whole

beneficial for their overall stress level. Positive self-talk class (Web log post). Retrieved from http://anxietyclass.blogspot.

com/201 0/ 1 1 /inclusive-strategies-that-benefit-whole.html

can be powerful in relation to anxiety. Helping stu-

Children's Mental Health Matters. (2009). Facts for educators: Anxiety

dents be mindful of how they talk about themselves disorders in children and adolescents. Retrieved from www.children

and their abilities can be influential in reducing smentalhealthmatters.org

anxiety. Cohen, L. J. (2013, September 26). The drama of the anxious child.

11. Accommodate tardies to school and class: Students with Retrieved from http://ideas.time.com/2013/09/26/the-drama-

of-the-anxious-child/

anxiety may arrive late to school for a variety of reasons

Dubois, D. L., Feiner, R. D., Brand, S., Adan, A. M., & Evans, E. G.

but it is important to allow students leeway, especially if(1992). A prospective study of life stress, social support, and

adaptation in early adolescence. Child Development , 63, 542-557.

students are having trouble with overall attendance at

Emmer, E., & Evertson, C. (2009). Classroom management for middle and

school. The act of coming to school can be a huge feat high schools (8th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

for students with anxiety. It is important not to punish

Gasparovich, L. (2008) . Positive behavior support: Learning to prevent or

the student for their actions (Packer & Pruitt, 2010) butmanage anxiety in the school setting (Newsletter). Retrieved from

www.sbbh.pitt.edu/files/other/Anxiety_LNG_newsletter.pdf

to reinforce their ability to make it to school.

Greenberg, M. T., Domitrovich, C., 8c Bumbarger, B. (2001). The

It is important for teachers to communicate regularly withprevention of mental disorders in school-aged children: Current

state of the field. Prevention and Treatment, 4, 1-62.

the school counselor and the parents and/ or guardians,

Johnson, C., Eva, A. L., Johnson, L., 8c Walker, B. (2011). Don't turn

providing updates as to how the accommodations are away: Empowering teachers to support students' mental health.

working and how their child is progressing (Children's The Clearing House, 84, 9-14.

Mental Health Matters, 2009). Keeley, M. L., 8c Storch, E. A. (2009). Anxiety disorders in youth.

Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 24{ 1), 26-40.

Kendall, P. C., Compton, S. N., Walkup, J. T., Birmaher, B., Albano,

A. M., Sherrill,J., Ginsburg, G., Rynn, M., McCracken, J., Gosch,

Summary E., Keeton, C., Bergman, L., Sakolsky, D., Suveg, C., Iyengar, S.,

March, J., 8c Piacentini, J. (2010). Clinical characteristics of anxi-

Although teachers are not responsible for diagnosing a ety disordered youth. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 24, 360-365.

student with anxiety, they are in very important positions Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P., Dernier, O., Jim, R., Merikangas, K R., 8c

Walters, E. E. (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset dis-

to help identify students who are showing signs of anxiety tributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey

and to support these students in the classroom (Sink & replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 593-602.

Igleman, 2004) . By intervening as soon as they have con- Lang, P. J. (1968). Fear reduction and fear behavior: Problems in

treating a construct. Inj. M. Schiein (Ed.), Research in psychother-

cerns and by using the systems they have in place within

apy, vol. 3. (pp. 90-103). Washington, DC: American

their schools, such as MTSS, teachers have increased the Psychological Association.

probability that students will have successful outcomes Mader, B. (2012, August 21). Easing middle school anxiety (Web log

(Children's Mental Health Matters, 2009). If left post). Retrieved from http:www.examiner.com/article/easing-

middle-school-anxiety

untreated, these students have an increased low levels of

Muris, P., 8c Meesters, C. (2002). Symptoms of anxiety disorders and

academic success, substance use, missed peer activities teacher-reported school functioning of normal children.

(ADAA, n.d.), potential school dropout and higher Psychological Reports, 91(2), 588-590.

This content downloaded from

181.55.131.99 on Tue, 29 Sep 2020 20:16:01 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Mychailyszyn, M. P., Mendez, J. L., 8c Kendall, P. C. (2010). School Retrieved from http://www.nasponline.org/publications/cq/

functioning in youth with and without anxiety disorders: 41 /8/anxiety.aspx

Comparisons by diagnosis and comorbidity. School Psychology

Review, , 39(1), 106-121.

Naparstek, N. (2009). Successful educators: A practical guide for under-

standing children's learning problems and mental health issues.

Appendix: Anxiety resources for

Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers. middle school teachers

Ollendick, T. H. (1998). Panic disorder in children and adolescents:

New developments, new directions. Journal of Clinical Child Articles and books

Psychology, 27, 234-245. doi:10.1207/sl5374424jccp2703_l.

Auger, R. (2011). The school counselor's mental health sourcebook:

Packer, L. E., 8c Pruitt, S. K. (2010). Challenging kids, challenged teachers: Strategies to help students succeed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Teaching students with Tourette's, Bipolar disorders , Executive dysfunction ,

Dacey, J. S., 8c Fiore, L. B. (2001). Your anxious child: How parents

OCD, ADHD, and more. Bethesda, MD: Woodbine House.

and teachers can relieve anxiety in children. San Francisco, CA:

Ramirez, G., 8c Beilock, S. L. (2011). Writing about testing worries Jossey-Bass.

boosts exam performance in the classroom. Science , 331 , 211-213.

Kline, F., & Silver, L. (2004). The educator's guide to mental health

doi: 10.11 26/science. 1 1 99427

issues in the classroom. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing.

Reinke, W. M., Stormont, M., Herman, K C., Puri, R., & Goel, N.

Packer, L. E., 8c Pruitt, S. K (2010). Challenging kids, challenged tea-

(2011). Supporting children's mental health in schools: Teacher

chers: Teaching students with Tourette's, Bipolar disorders, Executive

perceptions of needs, roles, and barriers. School Psychology

dysfunction, OCD, ADHD, and more. Bethesda, MD: Woodbine

Quarterly , 26(1), 1-13. House.

Roeser, R. W., 8c Midgley, C. (1997). Teachers' views of issues invol-

Schab, L. M. (2008). The anxiety workbook for teens: Activities to help you

ving students' mental health. The Elementary School Journal, 98(2),

115-133.

deal with anxiety and worry. Oakland, CA: Instant Help.

Tomb, M., 8c Hunter, L. (2004). Prevention of anxiety in children

Sink, C., 8c Igelman, C. N. (2004). Anxiety disorders. In F. Kline 8c L.

and adolescents in a school setting: The role of school-based

Silver (Eds.), The educator's guide to mental health issues in the class-

practitioners. Children àf Schools, 26(2), 87-101.

room (pp. 171-191). Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing.

Waller, R. J. (2006). Fostering child and adolescent mental health in the

Sulkowski, M. L., Wingfield, R. J., Jones, D., 8c Coulter, W. A. (2011).

classroom. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Response to intervention and interdisciplinary collaboration:

Joining hands to support children and families. Journal of Applied

School Psychology, 27, 1-16. doi: 10. 1080/ 15377903.201 1.565264

Websites

Tomb, M., 8c Hunter, L. (2004). Prevention of anxiety in children

and adolescents in a school setting: The role of school-based

ADAA: www.adaa.org

practitioners. Children àf Schools, 26(2), 87-101.

MentalHealth.gov: http:// www.mentalhealth.gov/

Van Ameringen, M., Mancini, C., 8c Farvolden, P. (2003). The impact

National Alliance on Mental Illness: http://www.nami.org

of anxiety disorders on educational achievement. Journal of anxiety

disorders, 17 ( 5), 561-571. National Institute of Mental Health: http://www.nimh.nih.gov

SchoolPsychiatry.org:

WorryWiseKids.org. (n.d.). Sample accommodations for anxious kids. http://www2.massgeneral.org/schoolpsychia

Retrieved from http://www.worrywisekids.org/node/ 40 try/index.asp

Wright, S., 8c Sulkowski, M. L. (2013). Assessing and treatingU.S. Department of Health and Human Services: http://www.mental

child-

hood anxiety in school settings. NASP Communique , 41(8). health.gov/

Kristen Moran is an assistant professor in the School of Education at Campbell University in Buies Creek, North Carolina. Email: kmoran@

campbell.edu.

This content downloaded from

181.55.131.99 on Tue, 29 Sep 2020 20:16:01 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Supporting and Responding To BehaviorDocument30 pagesSupporting and Responding To Behaviorapi-393967087No ratings yet

- Connie’s Gifts- Interactive Books and Collectibles. Got Parenting Challenges? Book 1From EverandConnie’s Gifts- Interactive Books and Collectibles. Got Parenting Challenges? Book 1No ratings yet

- Positive Behaviour SupportDocument14 pagesPositive Behaviour Supportapi-290018716No ratings yet

- Conflict Resolution Lesson Plan 03Document4 pagesConflict Resolution Lesson Plan 03api-396219108No ratings yet

- 26 Keys To Student EngagementDocument6 pages26 Keys To Student EngagementAngela MaiersNo ratings yet

- Brain Breaks: Activity SticksDocument7 pagesBrain Breaks: Activity SticksHayleyNo ratings yet

- Review of Best Parent EngagementDocument223 pagesReview of Best Parent EngagementDr. Afny AndryaniNo ratings yet

- 2nd Grade Bullying LessonDocument2 pages2nd Grade Bullying LessonLaura Witt100% (1)

- Staying Connected With Troubled StudentsDocument5 pagesStaying Connected With Troubled Studentsapi-123492799No ratings yet

- School Counseling Lesson Plan TemplateDocument2 pagesSchool Counseling Lesson Plan Templateapi-253009486No ratings yet

- What Is Health and WellbeingDocument16 pagesWhat Is Health and Wellbeingapi-269180388No ratings yet

- Alternatives To Out of School SuspensionDocument58 pagesAlternatives To Out of School Suspensionapi-202351147No ratings yet

- Research Into Practice: in A NutshellDocument6 pagesResearch Into Practice: in A Nutshellnabanita buragohainNo ratings yet

- Community EngagementDocument10 pagesCommunity Engagementapi-319564503No ratings yet

- Classroom Management ProfileDocument41 pagesClassroom Management Profileapi-503464923No ratings yet

- Letter To ParentsDocument2 pagesLetter To Parentsapi-395537786No ratings yet

- "All About Me" / ReproducibleDocument4 pages"All About Me" / ReproducibleThe Psycho-Educational TeacherNo ratings yet

- Week 5 - 6 - Social Emotional LiteracyDocument8 pagesWeek 5 - 6 - Social Emotional LiteracyCantos FlorenceNo ratings yet

- Diversity Activities For Youth and AdultsDocument12 pagesDiversity Activities For Youth and AdultsRadomir NikolicNo ratings yet

- The Empty PotDocument6 pagesThe Empty PotPremah BalasundramNo ratings yet

- 4 Goals of Misbehavior in Kids (Updated!) : Facebook 0Document3 pages4 Goals of Misbehavior in Kids (Updated!) : Facebook 0Radu LilianaNo ratings yet

- Cbs StudentvoiceDocument8 pagesCbs Studentvoiceapi-282945737No ratings yet

- Garden Based Learning Research Articles ListDocument4 pagesGarden Based Learning Research Articles ListBotanical Garden University of California BerkeleyNo ratings yet

- Forest Family Friendships UK - Big Life JournalDocument12 pagesForest Family Friendships UK - Big Life JournalEdl ZsuzsiNo ratings yet

- Teaching PhilosophyDocument3 pagesTeaching Philosophyapi-356514016No ratings yet

- Ositive Arenting: A Y C LDocument4 pagesOsitive Arenting: A Y C LDaniel A. Brown, PhDNo ratings yet

- Free Lesson Plan: How Do I Feel?Document6 pagesFree Lesson Plan: How Do I Feel?The Psycho-Educational Teacher100% (1)

- Gcu-Sec 510-Philosophy of Classroom Management-GiftDocument6 pagesGcu-Sec 510-Philosophy of Classroom Management-Giftapi-254305896No ratings yet

- Anisa Branch 703Document6 pagesAnisa Branch 703api-535374046No ratings yet

- Free Lesson Plan: Observation or Evaluation?Document4 pagesFree Lesson Plan: Observation or Evaluation?The Psycho-Educational Teacher67% (3)

- 12 Ways To Improve Concentration - Psychology TodayDocument5 pages12 Ways To Improve Concentration - Psychology Todayrfa940No ratings yet

- Grade 6 ArgumentationdocDocument51 pagesGrade 6 ArgumentationdocHeidi SwensonNo ratings yet

- Active Play-Active Learning: Brain Breaks GuideDocument23 pagesActive Play-Active Learning: Brain Breaks GuideSreejith SurendranNo ratings yet

- Boost Kindness in the ClassroomDocument10 pagesBoost Kindness in the ClassroomagusNo ratings yet

- Daily Program For CyrusDocument19 pagesDaily Program For Cyrusapi-342566134No ratings yet

- Co-Regulation From Birth Through Young Adulthood: A Practice BriefDocument10 pagesCo-Regulation From Birth Through Young Adulthood: A Practice BriefJulian BecerraNo ratings yet

- 6 UDL Best Practices for Online LearningDocument6 pages6 UDL Best Practices for Online LearningJomar Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- The K-12 Educator's Guide To Social Emotial Learning PDFDocument25 pagesThe K-12 Educator's Guide To Social Emotial Learning PDFNatividad Irala100% (1)

- Negative Effects of The Reward System ResponseDocument5 pagesNegative Effects of The Reward System Responseapi-420688546No ratings yet

- 5th Grade Lesson Plans SELDocument27 pages5th Grade Lesson Plans SELmariacojoc100% (2)

- Bucket FillersDocument63 pagesBucket FillersAnnetta WoolfolkNo ratings yet

- Superhero Week PlanDocument20 pagesSuperhero Week Planapi-446566858No ratings yet

- Strategies for Helping Disorganized StudentsDocument24 pagesStrategies for Helping Disorganized StudentsJia Xuan100% (2)

- Zones of RegulationsDocument8 pagesZones of Regulationsapi-287300063100% (1)

- Social Skills LessonDocument5 pagesSocial Skills LessonAshley DavidsonNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10 Curriculum Standards and TestingDocument26 pagesChapter 10 Curriculum Standards and Testingapi-523876090No ratings yet

- Enhanced Milieu Teaching BrochureDocument3 pagesEnhanced Milieu Teaching Brochureapi-458332874No ratings yet

- Interventions For Classroom DisruptionDocument54 pagesInterventions For Classroom DisruptionnosunarNo ratings yet

- Pbis Flow ChartDocument1 pagePbis Flow Chartapi-360475098No ratings yet

- 1 Plan B Cheat Sheet 020419 PDFDocument1 page1 Plan B Cheat Sheet 020419 PDFhd380No ratings yet

- Brain Breaks 2015Document7 pagesBrain Breaks 2015Jennifer BNo ratings yet

- Teacher Behavioral Strategies A MenuDocument6 pagesTeacher Behavioral Strategies A Menuapi-309686430No ratings yet

- Student Voice PamphletDocument2 pagesStudent Voice PamphletKen WhytockNo ratings yet

- Antibullying InterventionsDocument22 pagesAntibullying InterventionsAliArSaNo ratings yet

- Reading ManualDocument105 pagesReading Manualapi-202351147No ratings yet

- 2015-2016 123 Magic 2Document2 pages2015-2016 123 Magic 2api-240617339No ratings yet

- Coping Competencies What To Teach and WhenDocument10 pagesCoping Competencies What To Teach and WhenjuancaviaNo ratings yet

- Empathy Classroom Guidance LessonsDocument14 pagesEmpathy Classroom Guidance Lessonsapi-247143732No ratings yet

- Philosophy of Classroom ManagementDocument6 pagesPhilosophy of Classroom ManagementKate Klassen0% (1)

- 2 BIOLOGY CLASS Genetics Introduction 3.2 CHROMOSOMESDocument9 pages2 BIOLOGY CLASS Genetics Introduction 3.2 CHROMOSOMESPaulina ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Example Outline Section BDocument3 pagesExample Outline Section BPaulina ValenciaNo ratings yet

- IA General Format For DevelopmentDocument5 pagesIA General Format For DevelopmentPaulina ValenciaNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 152.200.151.201 On Tue, 08 Nov 2022 16:54:36 UTCDocument16 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 152.200.151.201 On Tue, 08 Nov 2022 16:54:36 UTCPaulina ValenciaNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 152.200.151.201 On Mon, 12 Sep 2022 15:50:23 UTCDocument14 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 152.200.151.201 On Mon, 12 Sep 2022 15:50:23 UTCPaulina ValenciaNo ratings yet

- As24.2 01milliganDocument26 pagesAs24.2 01milliganPaulina ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Visual Culture ArticleDocument13 pagesVisual Culture ArticlePaulina ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Visual Culture ArticleDocument13 pagesVisual Culture ArticlePaulina ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Oxford JournalsDocument11 pagesOxford JournalsPaulina ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Oxford JournalsDocument11 pagesOxford JournalsPaulina ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Asma G.SDocument5 pagesAsma G.SAfia FaheemNo ratings yet

- The American Colonial and Contemporary ArchitectureDocument2 pagesThe American Colonial and Contemporary ArchitectureHaha HahaNo ratings yet

- Cause and Effects of Social MediaDocument54 pagesCause and Effects of Social MediaAidan Leonard SeminianoNo ratings yet

- Multiple Linear RegressionDocument30 pagesMultiple Linear RegressionJonesius Eden ManoppoNo ratings yet

- Bcom MADocument21 pagesBcom MAAbl SasankNo ratings yet

- Chanakya National Law University, Patna: Project of Public International LawDocument22 pagesChanakya National Law University, Patna: Project of Public International LawAditya Singh100% (1)

- Hematology: AnemiaDocument46 pagesHematology: AnemiaCyrus100% (1)

- Ashtadhyayi of PaniniDocument19 pagesAshtadhyayi of Paniniall4downloads50% (2)

- Test Bank For Behavior Modification Principles and Procedures 6th EditionDocument36 pagesTest Bank For Behavior Modification Principles and Procedures 6th Editionempericetagragyj6f8100% (31)

- Maintenance and Service GuideDocument185 pagesMaintenance and Service GuidenstomarNo ratings yet

- HR Generalist SyllabusDocument4 pagesHR Generalist Syllabusdugdugdugdugi100% (1)

- Beauty Paulor Management SystemDocument2 pagesBeauty Paulor Management SystemTheint Theint AungNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To The Study of Medieval Latin VersificationDocument246 pagesAn Introduction To The Study of Medieval Latin VersificationGregorio Gonzalez Moreda100% (1)

- Scheme Samsung NT p29Document71 pagesScheme Samsung NT p29Ricardo Avidano100% (1)

- SMCDocument37 pagesSMCAmalina ZainalNo ratings yet

- CRIMINAL LAW DIGESTS 2014-2016: CONSPIRACY AND PROPOSALDocument519 pagesCRIMINAL LAW DIGESTS 2014-2016: CONSPIRACY AND PROPOSALRhic Ryanlhee Vergara Fabs100% (2)

- Here The Whole Time ExcerptDocument18 pagesHere The Whole Time ExcerptI Read YA100% (1)

- JVC Mini DV and S-VHS Deck Instruction Sheet: I. Capturing FootageDocument3 pagesJVC Mini DV and S-VHS Deck Instruction Sheet: I. Capturing Footagecabonedu0340No ratings yet

- Activity 3: Case Study Johnson & Johnson'S Stakeholder ApproachDocument3 pagesActivity 3: Case Study Johnson & Johnson'S Stakeholder ApproachNika CruzNo ratings yet

- ?PMA 138,39,40,41LC Past Initials-1Document53 pages?PMA 138,39,40,41LC Past Initials-1Saqlain Ali Shah100% (1)

- Corporate LendingDocument2 pagesCorporate LendingrubaNo ratings yet

- Amazon - in - Order 402-9638723-6823558 PDFDocument1 pageAmazon - in - Order 402-9638723-6823558 PDFanurag kumarNo ratings yet

- STOW - Vol. 3 - ScheduleDocument12 pagesSTOW - Vol. 3 - ScheduleDavid A. Malin Jr.100% (2)

- Levis Vs VogueDocument12 pagesLevis Vs VoguedayneblazeNo ratings yet

- Shadow On The Mountain Reading GuideDocument2 pagesShadow On The Mountain Reading GuideAbrams BooksNo ratings yet

- Reigeluth 1983Document14 pagesReigeluth 1983agssuga100% (1)

- Front Office Cover Letter No ExperienceDocument5 pagesFront Office Cover Letter No Experiencec2r7z0x9100% (1)

- Vasitars PVT Limited - Pipeline RepairsDocument12 pagesVasitars PVT Limited - Pipeline RepairsPavan_yoyo100% (1)

- FPSC@FPSC - Gove.pk: Sector F-5/1, Aga Khan Road, Islamabad Email: UAN:-051-111-000-248Document9 pagesFPSC@FPSC - Gove.pk: Sector F-5/1, Aga Khan Road, Islamabad Email: UAN:-051-111-000-248Ayaz AliNo ratings yet

- State of Employee Engagement: Global Survey 2010Document16 pagesState of Employee Engagement: Global Survey 2010aptmbaNo ratings yet