Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Role of Tilt-Table Test in Differential Diagnosis of Unexplained Syncope

Uploaded by

Yusrina Njoes SaragihOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Role of Tilt-Table Test in Differential Diagnosis of Unexplained Syncope

Uploaded by

Yusrina Njoes SaragihCopyright:

Available Formats

Acta Clin Croat 2015; 54:417-423

Original Scientific Paper

THE ROLE OF TILT-TABLE TEST IN DIFFERENTIAL

DIAGNOSIS OF UNEXPLAINED SYNCOPE

Marko Mornar Jelavić1, Zdravko Babić 2, Hrvoje Hećimović 3, Vesna Erceg4 and Hrvoje Pintarić 5

Center for Internal Medicine and Dialysis, Zagreb-East Health Center; 2Coronary Care Unit, Department of

1

Cardiology, 3Clinical Department of Neurology, 4Department of Cardiology, 5Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory,

Department of Cardiology, Sestre milosrdnice University Hospital Center, Zagreb, Croatia

SUMMARY – The aim of this retrospective study (February 2012 – September 2014) was to

assess the role of head-up tilt-table test in patients with unexplained syncope. It was performed on

235 patients at Clinical Department of Cardiology, Sestre milosrdnice University Hospital Center.

Patients were classified according to test indications: group A (convulsive syncope, n=30), group B

(suspected vasovagal syncope, n=180), and group C (paroxysmal vertigo, n=25). The groups were

analyzed and compared according to demographic data (age and gender), referral specialist (cardi-

ologist, neurologist, and others), and test results (positive/negative) with specific response (cardio-

inhibitory, vasodepressor, or mixed). Groups A and B were referred most frequently by neurologists

and cardiologists (p<0.05). The test was positive in 34 (14.5%) of all evaluated patients (5 in group

A and 29 in group B), of which 13 (38.2%) had cardioinhibitory, 11 (32.4%) mixed and 10 (29.4%)

vasodepressor response. In the cardioinhibitory subgroup, three patients (23.1%, 2 males/1 female,

mean age 28.5 years) with normal electroencephalography were on antiepileptics. During head-

up tilt-table testing, they had bradycardia (heart rate 30.0±5.0 beats/min) and prolonged asystole

(13.7±11.0 seconds) with development of typical convulsions. These three subjects got a permanent

pacemaker (atrial/ventricular stimulation, heart rate control) and anticonvulsive therapy was slowly

withdrawn with no syncope recurrence during 24-month follow up. In conclusion, head-up tilt-table

test has an important role in the evaluation of patients with unexplained syncope and in differential

diagnosis of vasovagal syncope. The indication for pacemaker implantation, strictly following the

European Society of Cardiology guidelines, proved to be effective in preventing syncope relapses in

patients with cardioinhibitory convulsive syncope.

Key words: Syncope – diagnosis; Syncope – prevention and control; Syncope, vasovagal – diagnosis;

Seizures; Tilt-table test; Pacemaker, artificial; Epilepsy

Introduction commonly nausea, dizziness, profound sweating, par-

esthesia, blurred vision and tinnitus. Previous studies

Syncope is defined as a brief and transient loss have shown that about 30% of adult population have

of consciousness and postural tone with spontane- ≥1 syncope during lifetime; some studies indicate that

ous and complete recovery. During syncope, there is this ratio is 2:1 in favor of young women1-7. The most

global cerebral hypoperfusion and loss of conscious- frequent form of syncope is vasovagal syncope. It is

ness is often preceded by prodromal symptoms, most mediated by excessive vagal stimulation, or disbalance

between sympathetic and parasympathetic autonomic

Correspondence to: Marko Mornar Jelavić, MD, Center for Inter- activity. Vasovagal syncope is classified into cardio-

nal Medicine and Dialysis, Zagreb-East Health Center, Ninska

10, HR-10000 Zagreb, Croatia inhibitory, vasodepressor, and mixed syncope. It oc-

E-mail: mjelavic@yahoo.com curs repeatedly in predisposed individuals with pre-

Received March 15, 2015, accepted October 1, 2015 cipitating factors such as emotional stress (especially

Acta Clin Croat, Vol. 54, No. 3, 2015 417

M. Mornar Jelavić et al. Head-up tilt-table testing in unexplained syncope

in warm, stifling spaces), fear, extreme fatigue, pain, ovagal syncope; and 3) group C: 25 patients with par-

prolonged standing, etc. Other causes of syncope oxysmal vertigo.

include cardiac problems (arrhythmias and struc- The groups were analyzed and compared according

tural heart diseases), orthostatic hypotension and to their baseline demographic data (age and gender),

orthostatic intolerance syndromes, and neurologic specialists who referred them, HUTT results (posi-

(transient ischemic attack, carotid vascular disease, tive/negative), and responses defined and classified by

migraine, epilepsy, Parkinson’s disease), metabolic the Vasovagal Syncope International Study (VASIS)

(hypoglycemia, shock, alcoholism) and psychogenic criteria16, as follows: 1) mixed (VASIS-1): heart rate

symptoms1-5,8. Convulsive syncope may be accom- (HR) decreases by >10% but does not decrease to <40

panied by neurologic symptoms (convulsions, eye beats/min for >10 seconds. Blood pressure (BP) falls

deviation and/or urinary incontinence). Clinical before HR; 2) cardioinhibition (VASIS-2A): mini-

semiology can often resemble epileptic seizures. This mum HR >40 beats/min for >10 seconds, or asystole

can lead to misdiagnosis, and according to some occurs for <3 seconds. BP falls before HR; 3) severe

studies, up to 30% of patients taking antiepileptics cardioinhibition/asystole (VASIS-2B): minimum HR

have syncope and not epileptic seizures9-13. Head-up <40 beats/min for >10 seconds, or asystole occurs for

tilt-testing (HUTT) is accepted as the gold standard >3 seconds. BP falls before or coincident with HR;

for diagnostic procedure of vasovagal syncope14,15. In and 4) pure vasodepression (VASIS-3): HR does not

this study, we investigated the following: 1) the role fall >10% from maximum rate during HUTT.

of HUTT in patients with unexplained syncope; 2) Additionally, in patients with positive HUTT we

the importance of HUTT in differential diagnosis analyzed symptoms developed during its conduction

of vasovagal syncope, especially in patients with (weakness, loss of consciousness, jerks, tongue bite,

convulsive syncope; and 3) the importance of prop- incontinence, eyeballs and head movement).

er selection of patients for pacemaker implantation The exclusion criteria were cerebrovascular dis-

and its impact on the quality of life improvement by eases (chronic cerebrovascular disease, cerebrovascu-

stopping syncope recurrences in patients with car- lar malformations), cerebral tumor or bleeding of any

dioinhibitory convulsive syncope. date, migraine and Parkinson’s disease or dementia,

confirmed by extensive prior neurological evaluation

(clinical examination, Doppler ultrasound of carotid

Patients and Methods

and vertebrobasilar arteries, computed tomography

This retrospective study was performed in 235 and magnetic resonance imaging brain scan). We also

consecutive patients undergoing HUTT between excluded patients with previously confirmed psycho-

February 2012 and September 2014. The investigation genic or metabolic disorders.

was indicated by cardiologists, neurologists, or other The HUTT was performed in accordance with the

specialists and performed at Department of Cardiol- European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines17,18.

ogy, Sestre milosrdnice University Hospital Center. The procedure started with the patient in supine posi-

The investigation was performed in accordance with tion on a special table during 20 minutes. During this

ethical standards laid down in the Declaration of time, the patient received 0.9% NaCl infusion. Elec-

Helsinki and approved by the appropriate institution- trocardiographic (ECG) recording and monitoring of

al committee. Patients were included independently BP and HR was done every 5 minutes. After that, the

and classified in three groups according to HUTT patient was lifted to vertical position for 60 minutes (or

indications, as follows: 1) group A: 30 patients with until typical symptoms occurred) with ECG record-

convulsive syncope, 12 of them were currently taking ing and measurement of BP and HR every 5 minutes.

antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) because of suspected epi- Finally, they were positioned back horizontally and the

lepsy. They all underwent prior thorough electroen- test was finished.

cephalographic (EEG) evaluation that classified them In accordance with the ESC guidelines17,18, some

with normal interictal, irritative and epileptic EEG patients fulfilled the criteria for implantation of a

findings; 2) group B: 180 patients with suspected vas- dual-chamber, rate modulated (DDDR) permanent

418 Acta Clin Croat, Vol. 54, No. 4, 2015

M. Mornar Jelavić et al. Head-up tilt-table testing in unexplained syncope

pacemaker. It was programmed to DDD pacing mode results (Table 1). Subjects in groups A and B were

and also received rate drop response pacing, a feature referred most frequently to the HUTT by neurologists

of the pacemaker that instituted rapid DDD pacing and cardiologists (p<0.05), and those in group C by

if the device detected a rapid decrease in heart rate. other specialists (such as general practitioners) (Fig. 1);

The programmed option specified that the initial rate 2) characteristics of patients with positive HUTT

drop response parameters should be a drop size of 20 are presented in Table 2. Most had VASIS-2A/2B,

beats, a drop rate of 70/min, and an intervention rate and not VASIS-1 or VASIS-3 responses, without sig-

of 100/min for 2 minutes. In addition, all pacemakers nificant age and gender differences. The test was posi-

were programmed with a lower rate at 50 bpm and a tive in five group A patients and 29 group B patients.

minimum atrioventricular delay of 200 ms to avoid There were significant differences in symptoms during

inappropriate pacing and to favor spontaneous cardiac HUTT between them, i.e. tonic-clonic jerks and eye

rhythm. After implantation, patients were scheduled deviation (p<0.05); and

for regular check-up at 3 months and then at every 6 3) group B subjects (patients with suspected vas-

months for the next 2 years. ovagal syncope) and group C subjects (patients with

paroxysmal vertigo) had their diagnosis affirmed with

Statistical analysis HUTT testing.

We further analyzed group A patients with con-

Qualitative data are presented as absolute numbers

vulsive clinical semiology. Among 30 group A sub-

and percentages. We used χ2-test with Yates correction

jects, there were 12 patients taking AEDs. Out of

for its analysis. Quantitative data are presented with

these 12 patients taking AEDs, three (two males/

median and interquartile ranges. Differences between

one female, mean age 28.5 years) patients had posi-

two groups were tested by Mann-Whitney U test and

tive HUTT (25%). They had a mean of 2.3±0.6 con-

Student’s t-test. Differences among three groups were

vulsive syncopes per year, repeatedly normal interictal

tested by nonparametric analysis of variance (Kruskal-

EEG and no prior cardiac problem. During HUTT,

Wallis ANOVA). The level of statistical significance

they developed cardioinhibitory VASIS-2B vasovagal

was set at p<0.05. Processing was done using the STA-

response with bradycardia (HR 30.0±5.0 beats/min)

TISTICA 6.0 software (StatSoft Inc., USA).

followed by prolonged asystole (13.7±11.0 seconds).

Clinically, they all had loss of consciousness with

Results

tonic-clonic jerks and eyeball deviation with upward

The HUTT was positive in 34 (14.5%) of all study gaze that lasted until restoration of the normal cardiac

subjects (N=235), 14 (41.2%) males and 20 (58.8%) rhythm.

females. The following test findings were recorded: In accordance with ESC guidelines17,18, in these

1) there were no significant differences among three three patients we implanted a DDDR pacemaker

groups according to demographic data and HUTT (Medtronic Kappa, Medtronic Inc., Minneapolis,

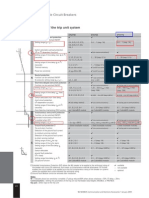

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients undergoing HUTT (N=235)

Group B

Findings Parameter Group A (n=30) Group C (n=25) Total p value

(n=180)

Age† 33.5 (27.0-59.0) 44.5 (29.0-63.5) 45.0 (30.5-52.5) 44.0 (29.0-61.0) 0.490

Demographic

data Male, n (%)‡ 12 (40.0) 64 (35.6) 9 (36.0) 85 (36.2) 0.896

Female, n (%)‡ 18 (60.0) 116 (64.4) 16 (64.0) 150 (63.8) 0.896

Positive, n (%)‡ 5 (16.7) 29 (16.1) 0 (0) 34 (14.5) 0.094

HUTT results

Negative, n (%)‡ 25 (83.3) 151 (83.9) 25 (100) 201 (85.5) 0.094

Group A = patients with convulsive syncope; group B = patients with suspected vasovagal syncope; group C = patients with paroxysmal

vertigo; HUTT = head-up tilt-table test; †data are presented as median and range, compared with Kruskal-Wallis (ANOVA) test; ‡data

are presented as absolute number and percentage, compared with χ2-test.

Acta Clin Croat, Vol. 54, No. 4, 2015 419

M. Mornar Jelavić et al. Head-up tilt-table testing in unexplained syncope

Fig. 2. Electroencephalographic findings in patients with

Fig. 1. Comparison of specialist referral to tilt-table convulsive syncope: 12 patients on antiepileptic drugs (A)

testing in patients with convulsive syncope (A), suspected and 18 patients with no medication (B).

vasovagal syncope (B) and paroxysmal vertigo (C).

Table 2. Characteristics of patients with positive HUTT (N=34)

Group A

Findings Parameter Group B (n=29) Total p value

(n=5)

Age† 34.0 (28.0-46.3) 35.0 (24.8-65.0) 34.5 (28.0-65.0) 0.789

Demographic

Male, n (%)‡ 2 (40.0) 12 (41.4) 14 (41.2) 0.664

data

Female, n (%)‡ 3 (60.0) 17 (58.6) 20 (58.8) 0.664

VASIS-1, n (%)‡ 1 (20.0) 10 (34.5) 11 (32.4) 0.903

VASIS-2A, n (%) ‡

0 (0) 2 (6.9) 2 (5.9) 0.672

HUTT VASIS-2B, n (%)‡ 3 (60.0) 8 (27.6) 11 (32.4) 0.361

response VASIS-3, n (%)‡ 1 (20.0) 9 (31.0) 10 (29.4) 0.975

Pause, n (%) ‡

3 (60.0) 8 (27.6) 11 (32.4) 0.361

Pause duration (sec)§ 13.7±11.0 8.8±6.0 10.0±7.3 0.338

Weakness, n (%)‡ 5 (100) 29 (100) 34 (100) 1.000

Loss of consciousness, n

3 (60.0) 7 (24.1) 10 (29.4) 0.274

(%)‡

Tonic-clonic jerks, n (%)‡ 3 (60.0) 0 (0) 3 (8.8) 0.0001

Symptoms

during Tongue bite, n (%) ‡

0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) -

HUTT

Incontinence, n (%)‡ 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) -

Eye deviation, n (%)‡ 2 (40.0) 0 (0) 2 (5.9) 0.013

Head movement, n (%)‡ 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) -

Group A = patients with convulsive syncope; group B = patients with suspected vasovagal syncope; HUTT = head-up tilt-table test; VASIS

= Vasovagal Syncope International Study; VASIS-1 = mixed vasovagal response; VASIS-2A = cardioinhibition/asystole <3.0 sec; VASIS-

2B = severe cardioinhibition/asystole ≥3.0 sec; VASIS-3 = pure vasodepression; †data are presented as median and range, compared with

Mann-Whitney U test; ‡data are presented as absolute number and percentage, compared with χ2-test; §data are presented as mean ±

standard deviation, compared with Student’s t-test.

420 Acta Clin Croat, Vol. 54, No. 4, 2015

M. Mornar Jelavić et al. Head-up tilt-table testing in unexplained syncope

MN, USA). During 6-month follow up, in two pa- found no gender differences in the type of vasovagal

tients we detected a drop rate 50/min, drop size 50/ response to HUTT22.

min, and a total of 10 pacemaker interventions. In We found a slightly lower prevalence of patients

one patient, we recorded a drop rate of 55/min, drop with positive HUTT testing (14.5%). More fre-

size of 25/min, and a total of 80 pacemaker interven- quently we found VASIS-2A/2B than VASIS-3 and

tions, and several episodes of non-sustained ventricle VASIS-1 response, with no significant age or gender

tachycardia. After 24-month follow up, none of the differences.

subjects had any syncope and AEDs were slowly Current ESC guidelines recommend HUTT for

withdrawn. Another nine patients taking AEDs had differential diagnosis of convulsive syncopes1. Ac-

negative HUTT. Five (41.7%) patients had normal in- cording to literature data, up to 25% of patients with

terictal, one (8.3%) patient epileptic and three patients recurrent loss of consciousness and nonspecific EEG

(25.0%) irritative EEG findings (Fig. 2). findings are taking anticonvulsants because of sus-

Among 18 patients with no specific therapy, there pected but not diagnosed epilepsy. A significant mi-

were two patients (females, mean age 50.5 years) with nority of these patients have vasovagal syncope9-13.

positive HUTT. They had normal interictal EEG, no Among our 12 patients that were on AEDs, only

cardiac disease and no medications. They had VASIS-1 one (8.3%) patient had prior epileptic EEG findings.

and VASIS-3 vasovagal response. We suggested them a In three (25.0%) patients with normal EEG we de-

conservative approach (hygienic-dietetic measures and tected VASIS-2B response with severe bradycardia

avoidance of provoking factors), which was effective and asystolic pauses >3.0 seconds. During syncope,

and they had no syncope recurrence. Another 16 pa- they had typical symptoms described to epileptolo-

tients had negative HUTT. Thirteen (72.2%) patients gists. In accordance with diagnostic test responses

had normal interictal and three (16.7%) patients had (VASIS-2B) and not responding to hygienic-dietetic

irritative EEG findings (Fig. 2). measures, these patients got indication for implanta-

tion of a permanent DDDR pacemaker. Implanta-

tion of permanent pacemakers in patients with asys-

Discussion

tole and younger than 40 years is recommended17,18.

In this study, we confirmed the role of HUTT in Studies have shown effectiveness of the permanent

the evaluation of patients with unexplained syncope. pacemaker implantation, especially a new contrac-

We demonstrated its importance in differential diag- tility-driven DDDR pacing and closed-loop stimu-

nosis of vasovagal syncope, especially in patients with lation compared with conventional DDI pacing, in

convulsive syncope. We also demonstrated the signif- these patients1,23-25. This is in accordance with our

icance of permanent pacemaker implantation for the results.

quality of life by reducing the number of syncopes in Ruiter and Barrett have reported good results in

patients with cardioinhibitory convulsive syncope and preventing syncope in VASIS-1 and VASIS-3 patients

subsequent withdrawal of AEDs. by increasing fluid intake and with physical counter-

Sandhu et al. found that most patients (72.0%) pressure23. In our two patients with suspected epilepsy

were referred to HUTT by cardiologists19. Several au- but normal EEG findings, VASIS-1 and VASIS-3

thors report that HUTT may be useful in the evalua- vasovagal response, conservative approach was suc-

tion of patients with unexplained syncope20,21. Galeta cessful in preventing syncope recurrence during the

et al. report on 139 (36.6%) patients with VASIS-1, 57 24-month follow up period.

patients (15.0%) with VASIS-2A/2B and 130 (34.2%) Two major mechanisms of transient loss of con-

patients with VASIS-3 response to HUTT. VASIS-3 sciousness are global cerebral hypoperfusion that re-

and VASIS-1 responses were the most frequent causes sults in syncope and asynchronous discharge of cere-

of syncope in older and younger subjects, respectively. bral neurons that leads to seizure26. In some studies,

It could be explained with physiological aging, asso- simultaneous EEG monitoring was performed during

ciated with reduction of the sympathetic-parasym- the HUTT and most authors showed diffuse brain

pathetic control of cardiac rhythm. Pietrucha et al. wave slowing down during a syncopal episode27-31.

Acta Clin Croat, Vol. 54, No. 4, 2015 421

M. Mornar Jelavić et al. Head-up tilt-table testing in unexplained syncope

In vasodepressor response, there is an appearance 5. Benditt DG, Goldstein M. Cardiology patient page. Faint-

of theta waves at the onset of syncope, followed by ing. Circulation. 2002;106(9):1048-50.

increase in the EEG amplitude with reduction of fre- 6. Vanbrabant P, Gillet JB, Buntinx F, Bartholomeeusen S,

quency in delta range. Return to supine position is as- Aertgeerts B. Incidence and outcome of first syncope in pri-

mary care: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Fam Pract.

sociated with restoration of a normal EEG pattern. 2011;12(1):102.

In cardioinhibitory response, there is generalized 7. Wieling W, Ganzeboom KS, Saul JP. Reflex syncope in chil-

slowing and occurrence of delta activity. A sudden re- dren and adolescents. Heart. 2004;90(9):1094-100.

duction of brain activity leads to disappearance of ce- 8. Škerk V, Pintarić H, Brkljačić DD, Popović Z, Hećimović H.

rebral EEG activity (a ‘flat’ EEG). Upon returning the Orthostatic intolerance: postural orthostatic tachycardia syn-

patient to supine position, the EEG slowly returned drome with overlapping vasovagal syncope. Acta Clin Croat.

to normal during full recovery of consciousness. 2012;51(1):93-5.

The main limitation of this study was that we did 9. Zaidi A, Clough P, Cooper P, Scheepers B, Fitzpatrick AP.

Misdiagnosis of epilepsy: many seizure-like attacks have a

not perform prolonged simultaneous EEG/ECG

cardiovascular cause. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:181-4.

monitoring in patients with convulsive syncope. Ac-

10. Sheldon R, Rose S, Ritchie D, Connolly SJ, Koshman ML,

cording to other authors, it is important in the di- Lee MA, et al. Historical criteria that distinguish syncope

agnosis of arrhythmogenic epilepsy in which partial from seizures. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40(1):142-8.

epileptic discharges profoundly disrupt normal car- 11. Scheepers B, Clough P, Pickles C. The misdiagnosis of epilep-

diac rhythm, including bradyarrhythmias and cardiac sy: findings of a population study. Seizure. 1998;7(5):403-6.

asystole. The appropriate treatment is double-headed, 12. Smith D, Defalla BA, Chadwick DW. The misdiagnosis of

including an antiepileptic drug and implantation of a epilepsy and the management of refractory epilepsy in a spe-

cialist clinic. Q JM. 1999;92(1):15-23.

permanent pacemaker32,33. Also, we had a short follow

up period. 13. Sander JW, O’Donoghue MF. Epilepsy: getting the diagno-

sis right. BMJ. 1997;314(7075):158-9.

In conclusion, syncope requires a multidisciplinary

14. Benditt DG, Sutton R. Tilt-table testing in the evaluation of

team and individualized approach. HUTT has an im-

syncope. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2005;16(3):356-8.

portant role in diagnostic evaluation of patients with

15. Guaraldi P, Calandra-Buonaura G, Terlizzi R, Cecere A,

recurrent unexplained syncope. It is indicated in the Solieri L, Barletta G, et al. Tilt-induced cardioinhibitory

differential diagnosis of vasovagal syncope, especially syncope: a follow-up study in 16 patients. Clin Auton Res.

in patients with syncope accompanied by convulsive 2012;22(3):155-60.

elements. These subjects will benefit from specific 16. Sutton R, Bloomfield D. Indications, methodology, and

therapy, thus improving their quality of life. classification of results of tilt table testing. Am J Cardiol.

1999;84:10-9.

17. Krediet CT, van Dijk N, Linzer M, van Lieshout JJ, Wiel-

References ing W. Management of vasovagal syncope: controlling or

aborting faints by leg crossing and muscle tensing. Circula-

1. Moya A, Sutton R, Ammirati F, Blanc JJ, Brignole M, Dahm tion. 2002;106(13):1684-9.

JB, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of

18. Brignole M, Auricchio A, Baron-Esquivias G, Bordachar P,

syncope (version 2009). Task Force for the Diagnosis and

Boriani G, Breithardt OA, et al. Guidelines for cardiac pac-

Management of Syncope. Eur Heart J. 2009;30(21):2631-71.

ing and cardiac resynchronization therapy: the Task Force for

2. Carlson MD. Syncope. In: Fauci AS, Kasper DL, editors. Cardiac Pacing and Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy of

Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 17th ed. New the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in Collabo-

York: McGraw-Hill; 2008. p. 139-43. ration with the European Heart Rhythm Association. Eur

3. Calkins H, Zipes DP. Hypotension and syncope. In: Libby P, Heart J. 2013;34(29):2281-329.

Bonow RO, editors. Braunwald’s Heart Disease: A Textbook 19. Sandhu KS, Khan P, Panting J, Nadar S. Tilt-table test: its

of Cardiovascular Medicine. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; role in modern practice. Clin Med. 2013;13(3):227-32.

2008. p. 975-83. 20. Fitzpatrick AP, Theodorakis G, Vardas P, Sutton R. Meth-

4. Bashore TM, Granger CB, Hranitzky P, Patel MR. Syncope. odology of head-up tilt testing in patients with unexplained

In: McPhee SJ, Papadakis MA, editors. Current Medical syncope. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17(1):125-30.

Diagnosis & Treatment 2011. 14th ed. New York: McGraw- 21. Galetta F, Franzoni F, Femia FR, Prattichizzo F, Bartolo-

Hill; 2011. p. 383-4. mucci F, Santoro G, et al. Responses to tilt test in young and

422 Acta Clin Croat, Vol. 54, No. 4, 2015

M. Mornar Jelavić et al. Head-up tilt-table testing in unexplained syncope

elderly patients with syncope of unknown origin. Biomed 28. Eiris-Punal J, Rodriguez-Nunez A, Fernandez-Martinez N,

Pharmacother. 2004;58(8):443-6. Fuster M, Castro-Gago M, Martinon JM. Usefulness of the

22. Pietrucha A, Wojewódka-Zak E, Wnuk M, Wegrzynowska head-upright tilt test for distinguishing syncope and epilepsy

M, Bzukała I, Nessler J, et al. The effects of gender and test in children. Epilepsia. 2001;42:709-13.

protocol on the results of head-up tilt test in patients with 29. Ammirati F, Colivicchi F, Di Battista G, Garelli FF, Santini

vasovagal syncope. Kardiol Pol. 2009;67(8A):1029-34. M. Electroencephalographic correlates of vasovagal syncope

23. Ruiter JH, Barrett M. Permanent cardiac pacing for neuro- induced by head-up tilt testing. Stroke. 1998;29:2347-51.

cardiogenic syncope. Neth Heart J. 2008;16(Suppl 1):S15-9. 30. Duplyakov D, Gavrilova E, Golovina G, Lyukshina N, Sy-

24. Deharo JC, Brunetto AB, Bellocci F, Barbonaglia L, Oc- suenkova E, Shagrova E, et al. Prevalence of epileptiform

chetta E, Fasciolo L, et al. DDDR pacing driven by contrac- findings on routine EEG and its influence on the result of

tility versus DDI pacing in vasovagal syncope: a multicenter, head-up tilt test in patients with neurocardiogenic syncope.

randomized study. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2003;26(1 Pt Eur Heart J. 2007;28(Suppl):640. (abstract)

2):447-50. 31. Mercader MA, Varghese PJ, Potolicchio SJ, Venkatraman

25. Occhetta E, Bortnik M, Audoglio R, Vassanelli C. Closed GK, Lee SW. New insights into the mechanism of neurally

loop stimulation in prevention of vasovagal syncope. Inotropy mediated syncope. Heart. 2002;88:217-21.

Controlled Pacing in Vasovagal Syncope (INVASY): a multi- 32. Novy J, Carruzzo A, Pascale P, Maeder-Ingvar M, Genné D,

centre randomized, single blind, controlled study. Europace. Pruvot E, et al. Ictal bradycardia and asystole: an uncommon

2004;6(6):538-47. cause of syncope. Int J Cardiol. 2009;133(3):e90-3.

26. Duplyakov D, Golovina G, Garkina S, Lyukshina N. Is it 33. Kouakam C, Daems C, Guédon-Moreau L, Delval A, Lacro-

possible to accurately differentiate neurocardiogenic syncope ix D, Derambure P, et al. Recurrent unexplained syncope may

from epilepsy? Cardiol J. 2010;17(4):420-7. have a cerebral origin: report of 10 cases of arrhythmogenic

27. Grossi D, Buonomo C, Mirizzi F, Santostasi R, Simone F. epilepsy. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2009;102(5):397-407.

Electroencephalographic and electrocardiographic features

of vasovagal syncope induced by head-up tilt. Funct Neurol.

1990;5:257-60.

Sažetak

ULOGA tilt TESTA u dIFERENCIJALNOJ DIJAGNOSTICI neobjašnjenE sinkopE

M. Mornar Jelavić, Z. Babić, H. Hećimović, V. Erceg i H. Pintarić

Cilj ovoga retrospektivnog istraživanja (veljača 2012. – rujan 2014. godine) bio je ispitati ulogu tilt testa u bolesnika s

neobjašnjenom sinkopom. Provedeno je na 235 bolesnika u Zavodu za kardiologiju KBC-a “Sestre milosrdnice”. Bolesnici

su klasificirani prema indikaciji za izvođenje testa: skupina A (konvulzivna sinkopa, n=30), skupina B (suspektna vazova-

galna sinkopa, n=180) i skupina C (paroksizmalni vertigo, n=25). Skupine su analizirane i uspoređivane prema njihovim

demografskim podacima (dob, spol), specijalistima koji su ih uputili na pretragu (kardiolozi, neurolozi, ostali) te rezulta-

tima (pozitivan/negativan) i specifičnim odgovorima (kardionhibicija, vazodepresija ili mješoviti) tilt testa. Skupine A i B

najčešće je na testiranje uputio neurolog i kardiolog (p<0,05). Test je bio pozitivan u 34 (14,5%) bolesnika (5 u skupini A i

29 u skupini B), od kojih je 13 (38,2%) imalo kardioinhibicijski, 11 (32,4%) mješoviti i 10 (29,4%) vazodepresivni odgovor.

U kardioinhibicijskoj podskupini troje bolesnika (23,1%, 2 muškarca/1 žena, srednje dobi 28,5 godina) je imalo normalan

nalaz elektroencefalografije i uzimali su antiepileptike. Tijekom izvođenja testa zabilježili smo bradikardiju (30,0±5,0 ot-

kucaja/min) i produženu asistoliju (13,7±11,0 sekunda) uz pojavu tipičnih konvulzija. U sve troje bolesnika ugrađen je traj-

ni elektrostimulator (atrijska/ventrikulska stimulacija, kontrola frekvencije) i ukinuta je antikonvulzivna terapija, nakon

čega su tijekom 24 mjeseca praćenja bili bez recidiva sinkope. U zaključku, tilt test ima važnu ulogu u procjeni bolesnika s

neobjašnjenom sinkopom i u diferencijalnoj dijagnostici vazovagalne sinkope. Indikacija za ugradnju elektrostimulatora,

strogo slijedeći smjernice Europskoga kardiološkog društva, pokazala se učinkovitom u sprječavanju recidiva sinkopa u

bolesnika s kardioinhbicijskom konvulzivnom sinkopom.

Ključne riječi: Sinkopa – dijagnostika; Sinkopa – prevencija i kontrola; Sinkopa, vazovagalna – dijagnostika; Napadaji; Test

tilt-table; Srčani elektrostimulator; Epilepsija

Acta Clin Croat, Vol. 54, No. 4, 2015 423

You might also like

- Causes of Syncope in Patients With AlzheDocument8 pagesCauses of Syncope in Patients With AlzheMichael VavosaNo ratings yet

- Idiopathic Pre-Capillary Pulmonary Hypertension in Patients With End-Stage Kidney Disease - Effect of Endothelin Receptor AntagonistsDocument9 pagesIdiopathic Pre-Capillary Pulmonary Hypertension in Patients With End-Stage Kidney Disease - Effect of Endothelin Receptor AntagonistsyuliaNo ratings yet

- Main 51 ???Document5 pagesMain 51 ???pokharelriwaj82No ratings yet

- Assessment of Palpitation Complaints Benign Paroxysmal Positional VertigoDocument6 pagesAssessment of Palpitation Complaints Benign Paroxysmal Positional VertigoHappy PramandaNo ratings yet

- In-Hospital Arrhythmia Development and Outcomes in Pediatric Patients With Acute MyocarditisDocument15 pagesIn-Hospital Arrhythmia Development and Outcomes in Pediatric Patients With Acute MyocarditisAnonymous OU6w8lX9No ratings yet

- Ijmps - The Value of Holter Monitoring PDFDocument6 pagesIjmps - The Value of Holter Monitoring PDFAnonymous Y0wU6InINo ratings yet

- 384.full With Cover Page v2Document14 pages384.full With Cover Page v2Tinh NguyenNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Scientific Research: General MedicineDocument4 pagesInternational Journal of Scientific Research: General MedicineTriple ANo ratings yet

- Early Prediction of Severity StrokeDocument11 pagesEarly Prediction of Severity StrokeainihanifiahNo ratings yet

- Eco Doppler Trascraneal 1Document12 pagesEco Doppler Trascraneal 1David Sebastian Boada PeñaNo ratings yet

- Does ThrombolysisDocument7 pagesDoes ThrombolysisNovendi RizkaNo ratings yet

- Electrocardiograph Changes in Acute Ischemic Cerebral StrokeDocument6 pagesElectrocardiograph Changes in Acute Ischemic Cerebral StrokeFebniNo ratings yet

- Accepted Manuscript: SeizureDocument21 pagesAccepted Manuscript: SeizureAhmad Harissul IbadNo ratings yet

- CSF Measurement Differences in Hydrocephalus, Atrophy and Healthy BrainsDocument4 pagesCSF Measurement Differences in Hydrocephalus, Atrophy and Healthy BrainsAffan AdibNo ratings yet

- Syncope 3Document19 pagesSyncope 3Pratyush PrateekNo ratings yet

- Effect of Right Ventricular Function and Pulmonary Pressures On Heart Failure PrognosisDocument7 pagesEffect of Right Ventricular Function and Pulmonary Pressures On Heart Failure PrognosisMatthew MckenzieNo ratings yet

- Missed Ischemic Stroke Diagnosis in The Emergency Department by Emergency Medicine and Neurology ServicesDocument7 pagesMissed Ischemic Stroke Diagnosis in The Emergency Department by Emergency Medicine and Neurology ServicesReyhansyah RachmadhyanNo ratings yet

- Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome Secondary To Acute Post-Streptococcal Glomerulonephritis in A 12-Year-Old GirlDocument2 pagesPosterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome Secondary To Acute Post-Streptococcal Glomerulonephritis in A 12-Year-Old GirlwawaningNo ratings yet

- The Heart Rate Response Pattern To Dialysis Hypotension in Haemodialysis PatientsDocument5 pagesThe Heart Rate Response Pattern To Dialysis Hypotension in Haemodialysis PatientsAnton SampNo ratings yet

- Cambios en El EKG Predictores de Edema Pulmonar Neurogénico en Hemorragia SubaracnoideaDocument4 pagesCambios en El EKG Predictores de Edema Pulmonar Neurogénico en Hemorragia SubaracnoideaCristina Duran GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Clinical Cases in Heart FailureFrom EverandClinical Cases in Heart FailureRavi V. ShahNo ratings yet

- Syncope Update 2004Document4 pagesSyncope Update 2004jkriengNo ratings yet

- PE and CHFDocument9 pagesPE and CHFKu Li ChengNo ratings yet

- Motor and Cognitive Impairment After StrokeDocument6 pagesMotor and Cognitive Impairment After StrokeFitri Amelia RizkiNo ratings yet

- Status Epilepticus in Patients With Cirrhosis 2016Document6 pagesStatus Epilepticus in Patients With Cirrhosis 2016Pablo Sebastián SaezNo ratings yet

- Carvedilol and Nebivolol Improve Left Ventricular Systolic Functions in Patients With Non-Ischemic Heart FailureDocument6 pagesCarvedilol and Nebivolol Improve Left Ventricular Systolic Functions in Patients With Non-Ischemic Heart FailureBramantyo DwiputraNo ratings yet

- Cardiac ArrhythmiasDocument5 pagesCardiac Arrhythmiastere glezNo ratings yet

- Stroke GuidelineDocument15 pagesStroke GuidelinePetrik Aqrasvawinata FsNo ratings yet

- Musictherapy DementiaDocument16 pagesMusictherapy DementiaConsuelo VelandiaNo ratings yet

- Jnen 080 Sherifa Ahmad HamedDocument8 pagesJnen 080 Sherifa Ahmad Hamedannisa edwarNo ratings yet

- Euro J of Neurology - 2023 - Kincl - Parkinson S Disease Cardiovascular Symptoms A New Complex Functional and StructuralDocument9 pagesEuro J of Neurology - 2023 - Kincl - Parkinson S Disease Cardiovascular Symptoms A New Complex Functional and StructuralIvan MihailovicNo ratings yet

- Corazon y SojenDocument7 pagesCorazon y Sojenmaria cristina aravenaNo ratings yet

- EHB 2015 Paper 157Document4 pagesEHB 2015 Paper 157Cringuta ParaschivNo ratings yet

- Ene 12372Document7 pagesEne 12372Andres Rojas JerezNo ratings yet

- 55421-Gagal JantungDocument21 pages55421-Gagal JantungAngie CouthalooNo ratings yet

- Syncope E:Manag Afp (Dragged) 2Document1 pageSyncope E:Manag Afp (Dragged) 2M.DalaniNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Value of History in Patients With Syncope With or Without Heart DiseaseDocument8 pagesDiagnostic Value of History in Patients With Syncope With or Without Heart DiseaseDaniela N AnghelNo ratings yet

- Etm 14 4 3563 PDFDocument6 pagesEtm 14 4 3563 PDFUlfahNo ratings yet

- Noc110069 346 351Document6 pagesNoc110069 346 351Carlos AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- Arteritis TakayasuDocument7 pagesArteritis TakayasuGina ButronNo ratings yet

- Guideline Stroke Perdossi 2007Document32 pagesGuideline Stroke Perdossi 2007l_hakim87No ratings yet

- Artigo Base SimoneDocument5 pagesArtigo Base SimoneWolfgang ThyerreNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Spasticity After Aneurysmal Subarachnoid HaemorrhageDocument5 pagesPrevalence of Spasticity After Aneurysmal Subarachnoid HaemorrhageJorgie Drew MonroeNo ratings yet

- Stroke PreventionDocument8 pagesStroke PreventionjaanhoneyNo ratings yet

- In-Hospital Stroke Recurrence and Stroke After Transient Ischemic AttackDocument15 pagesIn-Hospital Stroke Recurrence and Stroke After Transient Ischemic AttackferrevNo ratings yet

- Catatonia PDFDocument9 pagesCatatonia PDFDanilo RibeiroNo ratings yet

- FocusDocument9 pagesFocusAdéline NolinNo ratings yet

- Eur J Echocardiogr 2007 Scardovi 30 6Document7 pagesEur J Echocardiogr 2007 Scardovi 30 6Eman SadikNo ratings yet

- Leukoaraiosis Is Associated With Poor Outcomes After Successful Recanalization For Large Vessel Occlusion StrokeDocument7 pagesLeukoaraiosis Is Associated With Poor Outcomes After Successful Recanalization For Large Vessel Occlusion StrokeLaura Valentina Huertas SaavedraNo ratings yet

- Association of Low-Grade Albuminuria With Adverse Cardiac MechanicsDocument14 pagesAssociation of Low-Grade Albuminuria With Adverse Cardiac MechanicsM. Ryan RamadhanNo ratings yet

- Evolution of Neurological, Neuropsychological and Sleep-Wake Disturbances After Paramedian Thalamic StrokeDocument8 pagesEvolution of Neurological, Neuropsychological and Sleep-Wake Disturbances After Paramedian Thalamic Strokepokharelriwaj82No ratings yet

- Abstrak INAECHODocument21 pagesAbstrak INAECHOAgung Angga KesumaNo ratings yet

- Cardiac Troponin-I As A Marker of Myocardial Dysfunction in Children With Septic ShockDocument5 pagesCardiac Troponin-I As A Marker of Myocardial Dysfunction in Children With Septic ShockjessicaesmrldaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0167527302000311 MainDocument10 pages1 s2.0 S0167527302000311 MainMerve Sibel GungorenNo ratings yet

- Bezold JarischDocument6 pagesBezold Jarischbecky_meloniNo ratings yet

- Care of Client with CVA and Hypertension (Less than 40 charsDocument75 pagesCare of Client with CVA and Hypertension (Less than 40 charsVhince Norben PiscoNo ratings yet

- Epilepsia - 2005 - Paolucci - Poststroke Late Seizures and Their Role in Rehabilitation of InpatientsDocument5 pagesEpilepsia - 2005 - Paolucci - Poststroke Late Seizures and Their Role in Rehabilitation of InpatientsKookie YerimNo ratings yet

- Subclinical Hypertensive Heart Disease in Black Patients With Elevated Blood Pressure in An Inner-City Emergency DepartmentDocument9 pagesSubclinical Hypertensive Heart Disease in Black Patients With Elevated Blood Pressure in An Inner-City Emergency DepartmentDianNo ratings yet

- Levy2012 PDFDocument9 pagesLevy2012 PDFDianNo ratings yet

- 10.1007@s10554 020 01913 6Document10 pages10.1007@s10554 020 01913 6Bosman AriestaNo ratings yet

- Alterations in Ventricular Pumping in Patients With Atrial Septal Defect at Rest, During Dobutamine Stress and After Defect ClosureDocument10 pagesAlterations in Ventricular Pumping in Patients With Atrial Septal Defect at Rest, During Dobutamine Stress and After Defect ClosureYusrina Njoes SaragihNo ratings yet

- Transcatheter Closure of Atrial Septal Defects Improves Cardiac Remodeling and Function of Adult Patients With Permanent Atrial FibrillationDocument4 pagesTranscatheter Closure of Atrial Septal Defects Improves Cardiac Remodeling and Function of Adult Patients With Permanent Atrial FibrillationYusrina Njoes SaragihNo ratings yet

- Predictive Factors For Patients Undergoing ASD Device Occlusion Who Crossover'' To SurgeryDocument5 pagesPredictive Factors For Patients Undergoing ASD Device Occlusion Who Crossover'' To SurgeryYusrina Njoes SaragihNo ratings yet

- Journal of CardiologyDocument7 pagesJournal of CardiologyYusrina Njoes SaragihNo ratings yet

- Trans-Catheter Closure of Atrial Septal Defect: Balloon Sizing or No Balloon Sizing - Single Centre ExperienceDocument6 pagesTrans-Catheter Closure of Atrial Septal Defect: Balloon Sizing or No Balloon Sizing - Single Centre ExperienceYusrina Njoes SaragihNo ratings yet

- Alterations in Ventricular Pumping in Patients With Atrial Septal Defect at Rest, During Dobutamine Stress and After Defect ClosureDocument10 pagesAlterations in Ventricular Pumping in Patients With Atrial Septal Defect at Rest, During Dobutamine Stress and After Defect ClosureYusrina Njoes SaragihNo ratings yet

- Predictive Factors For Patients Undergoing ASD Device Occlusion Who Crossover'' To SurgeryDocument5 pagesPredictive Factors For Patients Undergoing ASD Device Occlusion Who Crossover'' To SurgeryYusrina Njoes SaragihNo ratings yet

- Journal of CardiologyDocument7 pagesJournal of CardiologyYusrina Njoes SaragihNo ratings yet

- Transcatheter Closure of Atrial Septal Defects Improves Cardiac Remodeling and Function of Adult Patients With Permanent Atrial FibrillationDocument4 pagesTranscatheter Closure of Atrial Septal Defects Improves Cardiac Remodeling and Function of Adult Patients With Permanent Atrial FibrillationYusrina Njoes SaragihNo ratings yet

- Arterial Stiffness and The Development of HypertensionDocument7 pagesArterial Stiffness and The Development of HypertensionYusrina Njoes SaragihNo ratings yet

- Pdflib Plop: PDF Linearization, Optimization, Protection Page Inserted by Evaluation VersionDocument13 pagesPdflib Plop: PDF Linearization, Optimization, Protection Page Inserted by Evaluation VersionYusrina Njoes SaragihNo ratings yet

- Trans-Catheter Closure of Atrial Septal Defect: Balloon Sizing or No Balloon Sizing - Single Centre ExperienceDocument6 pagesTrans-Catheter Closure of Atrial Septal Defect: Balloon Sizing or No Balloon Sizing - Single Centre ExperienceYusrina Njoes SaragihNo ratings yet

- Arterial StiffDocument7 pagesArterial StiffYusrina Njoes SaragihNo ratings yet

- 1761 FullDocument8 pages1761 FullYusrina Njoes SaragihNo ratings yet

- 7.20.09 Stewart Venous InsufficiencyDocument25 pages7.20.09 Stewart Venous InsufficiencyYusrina Njoes SaragihNo ratings yet

- 1761 FullDocument8 pages1761 FullYusrina Njoes SaragihNo ratings yet

- s12933 014 0128 5 PDFDocument11 pagess12933 014 0128 5 PDFYusrina Njoes SaragihNo ratings yet

- Novel Methods For Pulse Wave Velocity MeasurementDocument11 pagesNovel Methods For Pulse Wave Velocity MeasurementYusrina Njoes SaragihNo ratings yet

- J Interven Cardiol. 2017 1-7.: Presented By: Dr. Yusrina BR Saragih Supervisor: DR - Dr. Zulfikri Mukhtar, Sp. JP (K)Document24 pagesJ Interven Cardiol. 2017 1-7.: Presented By: Dr. Yusrina BR Saragih Supervisor: DR - Dr. Zulfikri Mukhtar, Sp. JP (K)Yusrina Njoes SaragihNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0019483216303200 MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S0019483216303200 MainYusrina Njoes SaragihNo ratings yet

- Arterial Stiffness and The Development of HypertensionDocument7 pagesArterial Stiffness and The Development of HypertensionYusrina Njoes SaragihNo ratings yet

- Removal of A Pinned Spiral by Generating Target Waves With A Localized StimulusDocument5 pagesRemoval of A Pinned Spiral by Generating Target Waves With A Localized StimulusGretymjNo ratings yet

- Can You Distinguish Neutral, Formal and Informal Among The Following Groups of WordsDocument3 pagesCan You Distinguish Neutral, Formal and Informal Among The Following Groups of WordsВікторія РудаNo ratings yet

- Customer Role in Service DeliveryDocument13 pagesCustomer Role in Service DeliveryDevinder ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- Multiple Reactions Assignment Problems 2 To 5Document2 pagesMultiple Reactions Assignment Problems 2 To 5DechenPemaNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument10 pagesUntitledVeneta GizdakovaNo ratings yet

- Oil Keeper Job at PacrimDocument2 pagesOil Keeper Job at Pacrimwinda chairunissaNo ratings yet

- Steps in Balancing Redox ReactionsDocument28 pagesSteps in Balancing Redox ReactionsRUZCHEMISTRYNo ratings yet

- Food Hydrocolloids: Long Chen, Yaoqi Tian, Yuxiang Bai, Jinpeng Wang, Aiquan Jiao, Zhengyu JinDocument11 pagesFood Hydrocolloids: Long Chen, Yaoqi Tian, Yuxiang Bai, Jinpeng Wang, Aiquan Jiao, Zhengyu JinManoel Divino Matta Jr.No ratings yet

- Text CDocument1,100 pagesText CAli NofalNo ratings yet

- Instructional Materials: For K12Document17 pagesInstructional Materials: For K12Ram Jacob LevitaNo ratings yet

- Jesus Uplifts The PoorDocument10 pagesJesus Uplifts The Poor명연우No ratings yet

- Ijpcr 22 309Document6 pagesIjpcr 22 309Sriram NagarajanNo ratings yet

- DAVAO DOCTORS COLLEGE NURSING DRUG STUDYDocument3 pagesDAVAO DOCTORS COLLEGE NURSING DRUG STUDYJerremy LuqueNo ratings yet

- ETU 776 TripDocument1 pageETU 776 TripbhaskarinvuNo ratings yet

- Quality Operating Process: Manual of Operations Care of PatientsDocument4 pagesQuality Operating Process: Manual of Operations Care of PatientsPrabhat KumarNo ratings yet

- Aprinnova Simply Solid One Page SummaryDocument2 pagesAprinnova Simply Solid One Page SummaryPatrick FlowerdayNo ratings yet

- AISC Design Guide 27 - Structural Stainless SteelDocument159 pagesAISC Design Guide 27 - Structural Stainless SteelCarlos Eduardo Rodriguez100% (1)

- PDFDocument218 pagesPDFRague MiueiNo ratings yet

- Solid Phase ExtractionDocument16 pagesSolid Phase ExtractionDAVID VELEZNo ratings yet

- AMERICAN FARM SHEPHERDS ILLUSTRATED 2021 June Volume 1, Issue 2Document8 pagesAMERICAN FARM SHEPHERDS ILLUSTRATED 2021 June Volume 1, Issue 2Old-fashioned Black and Tan English Shepherd AssocNo ratings yet

- Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma and Its Variants: Pearls and PerilsDocument20 pagesPancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma and Its Variants: Pearls and PerilsGeorge MogaNo ratings yet

- Manitowoc Cff-90 PartsDocument13 pagesManitowoc Cff-90 PartsDaren FerreiraNo ratings yet

- Nanostrength Block Copolymers For Epoxy TougheningDocument5 pagesNanostrength Block Copolymers For Epoxy TougheningRonald GeorgeNo ratings yet

- EOA 2023 VISIOMER Portfolio Brochure en Digital RZ InteraktivDocument13 pagesEOA 2023 VISIOMER Portfolio Brochure en Digital RZ Interaktivichsan hakimNo ratings yet

- BG 370 Operation & Maintenance ManualDocument32 pagesBG 370 Operation & Maintenance ManualRamasubramanian SankaranarayananNo ratings yet

- Properties of Bituminous Binder Modified With Waste Polyethylene TerephthalateDocument12 pagesProperties of Bituminous Binder Modified With Waste Polyethylene Terephthalatezeidan111No ratings yet

- 17EEX01-FUNDAMENTALS OF FIBRE OPTICS AND LASER INSTRUMENTATION SyllabusDocument2 pages17EEX01-FUNDAMENTALS OF FIBRE OPTICS AND LASER INSTRUMENTATION SyllabusJayakumar ThangavelNo ratings yet

- Axell Wireless Cellular Coverage Solutions BrochureDocument8 pagesAxell Wireless Cellular Coverage Solutions BrochureBikash ShakyaNo ratings yet

- Bengal PresentationDocument37 pagesBengal PresentationManish KumarNo ratings yet

- How to Give a Woman the Most Powerful OrgasmDocument10 pagesHow to Give a Woman the Most Powerful OrgasmFederico Ceferino BrizuelaNo ratings yet