Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Locality and Essence in Arabic Science

Uploaded by

Fidel AndreettaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Locality and Essence in Arabic Science

Uploaded by

Fidel AndreettaCopyright:

Available Formats

Situating Arabic Science: Locality versus Essence

Author(s): A. I. Sabra

Source: Isis, Vol. 87, No. 4 (Dec., 1996), pp. 654-670

Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of The History of Science Society

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/235197 .

Accessed: 07/04/2014 05:08

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The University of Chicago Press and The History of Science Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize,

preserve and extend access to Isis.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 87.161.248.86 on Mon, 7 Apr 2014 05:08:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

HISTORYOF SCIENCE SOCIETY

DISTINGUISHED LECTURE

Situating Arabic Science

Locality versus Essence

By A. I. Sabra*

LOCALITY AS A FOCUS OF HISTORIOGRAPHY

I trustthat no one would wish to contest the propositionthat all history is local history-

whetherthe locality is that of a short episode or of a long story. All history is local, and

the history of science is no exception. There can be no history of science that is not

concernedwith a localized episode or a sequenceof such episodes. Philosophersof science,

or some of them, may restrictthemselves to analyzing the formal or logical and timeless

structureof a piece of scientific thought;or they may substitutean emphasison growthas

a basic featureof scientific inquirythat requiresfor its logical elucidationthe additionof

a temporaldimension that retains an abstractcharacter.But historiansof science have a

differenttask. For while they can ignore the cognitive core of scientific practice only at

the cost of forfeiting their claim to a distinctive problematicand a distinctive discipline,

they are especially concernedwith science as a process that takes place in actual time or

science as a series of phenomenathat, owing to their special characterof chronological

and geographicallocality, we call "historical"-this "special character"being due to the

fact thatthe phenomenain questionare not merely in space and time but events associated

with, and indeed producedby, individuals acting in what we broadly call "culturalset-

tings."The thesis outlinedin these few abstractsentences is but a generalizationof a weak

version of the familiarcontextualistthesis in scientific historiography;or, to put it another

* Departmentof the History of Science, HarvardUniversity, Science Center235, Cambridge,Massachusetts

02138.

This lecture was delivered at the annualmeeting of the History of Science Society, Minneapolis,Minnesota,

28 October 1995. I am greatly honoredto have been invited to give this talk. I have since made a few additions

and changes, some of them in response to comments, questions, or criticisms by the anonymous referees, to

whom my thanksare due.

Isis, 1996, 87: 654-670

C) 1996 by The History of Science Society. All rights reserved.

0021-1753/96/8401-0001$01.00

654

This content downloaded from 87.161.248.86 on Mon, 7 Apr 2014 05:08:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A. I. SABRA 655

way, contextualismis but an obvious consequence of the simple, undeniablefact of the

local characterof all events, includinghistoricalevents. Since a historicalevent is where

and when and how it is, inseparablytied to all the circumstancesthat combine to define

it for us as historians, then, to be genuinely historical, all history of science must be

contextual,because all historicalevents are local.

I said "weak version" because I do not wish to subscribe to a stronger,reductionist

version that seems to me to misinterpretthe local characterof cognitive expression and

behaviorby appearingto deprivethem of objective import.At the risk of being much too

brief, let me indicatewhat I mean with just a sentence or two before I get on to my subject

proper. I am persuaded,as I hope you are, that locality is not a propertyof a piece of

scientific thought-say, the Pythagoreantheorem. In other words, the Pythagoreantheo-

rem, not being an event in the spatiotemporalworld, has no space-time coordinates.But

recognizing it as a theoremin a given geometricalsystem with certaindefinablefeatures

was the achievementof someone or other who certainlyhad such coordinates.From this

it would seem to follow that the historicalstudy of scientific thoughtis, strictlyspeaking,

not concerned with the thought content of science as such (that would be to engage in

science, logic, or philosophical analysis), but with the historical occurrence of the rec-

ognition of thought.I am aware that all of this has been said before and in various ways

by philosophersand historiansto serve ratherdifferent agendas. So, to avoid misunder-

standing,I will just addthe observationthatrecognitionof thoughtalways involves, among

other things, a cognitive context that itself is location-bound,in the sense of being partof

a problem situationthat depends on the existing state of knowledge at a given time and

place. And this means that engaging in science, logic, and philosophicalanalysis may all

be involved in the historical study of scientific thought.'

My purposehere is to try to illustratethe advantagesof a strict adherenceto the axiom

of locality in situatingthe traditionof Arabic science with referenceboth to the place that

this traditionoccupies in the general history of science and to its place in the civilization

where it emerged and developed. My discussion will thus be concernedwith two contexts

that, though distinct from one another,are, as I shall suggest, intimatelyconnected with

each other. Obviously what I shall present to you can only be the bare sketch of what

might be described as a frameworkfor research, but, I hope, a frameworkthat is not

irrelevantto other scientific traditionsand that may even propose a correctionto other

historiographiesthat seem to pay little or no attentionto the interculturaltransmissionof

scientific knowledge.

Let us begin with an apparentlyneutraland innocent definitionof Arabic, or what may

also be called Islamic, science in terms of location in space and time: the termArabic (or

Islamic) science denotes the scientific activities of individualswho lived in a region that

roughly extended chronologically from the eighth century A.D. to the beginning of the

modernera, and geographicallyfrom the IberianPeninsulaand North Africa to the Indus

valley and from southernArabiato the CaspianSea-that is, the region covered for most

of thatperiodby what we call Islamic civilization, and in which the resultsof the activities

referredto were for the most part expressed in the Arabic language. We need not be

concernedover the refinementsthat obviously need to be introducedeven into this seem-

ingly neutraldefinition.But what about the term scientific in it? What does it mean, and

I For ideas underlyingthe theoreticalstructureof this essay I am indebted to the writings of Gottlob Frege

(on the distinctionbetween thoughtand recognitionof thought),KarlPopper(on methodologicalindividualism,

situationallogic, interactionof Worlds 1, 2, and 3), and Alfred North Whitehead(all about events).

This content downloaded from 87.161.248.86 on Mon, 7 Apr 2014 05:08:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

656 SITUATINGARABIC SCIENCE

can it be regardedas in any way "innocent"?To me it seems clear that the only correct

answerto this last question must be an unequivocalNo. Science and scientificare our own

terms and they express our own concepts (which, by the way, does not mean thatthey are

sharplydefinedor unproblematic);and,therefore,the studyof any past intellectualactivity

can be relevantto what we call "historyof science" only to the extent that such an activity

can be shown to help us understandthe modes of thought and expression and behavior

thatwe have come to associatewith the word science. This is not anachronism,presentism,

whiggism, or any of the other objectionableisms, but a consequence of the fact that we

who are writing the history also have a location of our own that defines our perspective

and, hence, the questions we pose from our vantage point and the terms in which these

questions are framed.Nor should this admissionto a definitepoint of view discourageor

detractfrom investigatingpast modes of thoughtand expression and behaviorunderother

categoriesdeemed suitablefor elucidatingthese modes "in their own terms,"as the phrase

goes. But, without aiming to replace other approachesthat put the emphasis on certain

concerns of sociology or anthropologyor culturalhistory, our historiographyof science

will always change as a function of our changingposition, being ourselvesforeverlocated

at the end point of the process that is continually shaping and reshaping what we call

"science."And so I am led to combine a self-evident propositionwith anotherthat seems

no more, and no less, than a corollary of it: that all history of science is local, and no

history of science can ever be neutral.

The characterof Arabic science, its strengthsandfailings, the course of its development,

and its ultimatefate have all been variouslyexplained in terms of language as a matrixof

thoughtand expression, of religion as an inexorableshapingforce, of naturalaptitudesor

inclinations of a certain race or inherentmentality, or as one inevitable expression of a

world cultureof which Islamic civilization was a late embodiment.A perceivedemphasis

on algebra in the Arabic traditionhas been attributedto certain features of Semitic lan-

guages that make these languages or their native users prone to "algebraization,"as op-

posed to Greek "geometrization."The persistentattemptsof Islamic astronomersto con-

struct kinematic models primarily designed to save the principles and the logical

consistency of Ptolemaic astronomyhave been seen as a sign of poverty of imagination

or of the tendencyof the "Semiticmind"towardthings it can easily perceiveby the senses.

Islamic religion has been cited both as the origin and source of vigor of medieval Islamic

science and as the majorcause of its final demise. And the "spiritof culture,"in this case

a Magianculturealreadyat work in "so-called"late antiquity,has been invoked to account

for every aspect of Islamic civilization, including its scientific products.2

It is not difficult to expose the weaknesses from which such explanationssuffer. One

2 Roger Arnaldezand Louis Massignon, "ArabicScience," in History of Science: Ancient and Medieval Sci-

ence, from the Beginnings to 1450, ed. Ren6 Taton, trans.A. J. Pomerans(New York: Basic, 1963), Vol. 3, Ch.

2, pp. 385-421, esp. pp. 402-405; Massignon, "R6flexionssur la structureprimitive de l'analyse grammaticale

en arabe,"Arabica, 1954, 1:3-16; Pierre Duhem, Le systeme du monde, Vol. 2 (Paris: Vrin, 1954), pp. 117-

179, esp. pp. 117-119 (on "le r6alismedes arabes");Duhem, To Save the Phenomena:An Essay on the Idea of

Physical Theoryfrom Plato to Galileo, trans.EdmundDolan and ChaninahMaschler (Chicago/London:Univ.

Chicago Press, 1969), pp. 25-35, esp. p. 26; BernardCarrade Vaux, "Les spheres c6lestes selon Nasir-Eddln

Attfisi," in Paul Tannery,Recherches sur 1'histoirede l'astronomie ancienne (Paris: Gauthier-Villars,1983),

App. 6, pp. 337-361; G. E. von Grunebaum,"MuslimWorld View and Muslim Science," in Islam: Essays in

the Nature and Growth of a Cultural Tradition(London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1964), pp. 111-126; von

Grunebaum,"Islamand Hellenism,"in Islam and Medieval Hellenism: Social and CulturalPerspectives (Lon-

don: Variorum, 1976), Ch. 1; J. J. Saunders,"The Problem of Islamic Decadence,"Journal of WorldHistory,

1963, 7:701-720; and Oswald Spengler, The Decline of the West, trans. Charles Francis Atkinson, 2 vols.

(London:Allen & Unwin, 1959), esp. Vol. 1, pp. 71-73, 207-216 (and see the index under"ArabianCulture").

This content downloaded from 87.161.248.86 on Mon, 7 Apr 2014 05:08:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A. I. SABRA 657

can refer, for example, to the considerableand highly successful efforts of Islamic math-

ematiciansin the fields of geometry and trigonometry.One can relate the theoreticalpro-

gramof Islamic astronomersto the work of Ptolemy himself and to earlierideals of Greek

astronomy. One can point out the great complexity of the relationshipbetween science

and religion throughoutIslamic history and in variouspartsof the Islamic world. And one

can easily show the vacuousness of theories born of the spirit-of-cultureapproach.And,

in fairness to those who have advanced explanationsof these sorts, it must be said that

they tend to be poorly informed(or worse) aboutArabic science and, in many cases, about

Islamic civilization-a fact that, unfortunately,does not seem to have discouragedtheir

influence on minds that seek ready-madeand perhapscomfortingexplanations.

What is wrong with these explanations,and others like them, is not their consideration

of language, religion, and cultureas factors in the formationof a scientific enterprisethat

consciously adoptedearliertraditionswith markedlydifferentlanguagesand religious and

cultural values but, rather,their essentialist character,which has tended to prejudiceor

obstruct historical research. Now locality-that is, the characterof being local-is an

ineradicableor, if you like, an essential propertyof all historical events, but the actual

where and when and how of any such events are happeningscreated by human effort.

With the sure perceptiveness of a true historian, Richard Southern once described the

process of acquisitionand adaptationof Greek learningin Islam as "the most astonishing

event in the history of thought."3The event is astonishingbecause it strikes us as unex-

pected, and the best way I know to explain the unexpectedin history, insofar as it can be

explainedat all, is to try to understandit, not in termsof essences or spiritsor inevitabilities,

but as the outcome of choices by individualsand groups respondingto their situationsas

they perceived and experiencedthem. Let me illustrate.

THE INTERSECTION OF ISLAMISM, ARABISM, AND HELLENISM IN

NINTH-CENTURY BAGHDAD

The powerful drive that eventually led to the transferof the bulk of Greek science and

philosophy (as well as elements of the scientific thoughtof Indiaand Persia)to Islam was

launchedas a massive translationeffort thattook place in the context of empire and under

the patronageof the confident Abbasid court in Baghdad. Translationsinto Arabic had

been made earlier, and these had been preceded in the Middle East by translationsfrom

the Greek into Syriac and Persian,but it was the Abbasids who mounted a concentrated

translationeffort soon after they came to power in the middle of the eighth century and

who furtherorganizedand intensifiedtheir supportduringthe ninth century.Under their

predecessors, the Umayyads who ruled from Damascus (661-750), the Islamic empire

alreadyencompassedlarge areas-including Egypt, Syria, and Persia-that had come un-

der the influence of Hellenism from the time of Alexander;and before the ninth century

was over Islamic rule had reachedKashmirin the east and Khwarazmto the north.In the

early Abbasid period the higher administrationof the court itself was in the hands of

cultivatedPersianswho had gained much favor and influencewith the Abbasidrulersand

whose intellectual interests inclined them to various forms of secular learning and to a

rationalizingapproachfor understandingmattersof religious belief. Some of these Persian

officials acted as translators,especially from Persian, and in general they constitutedan

I R. W. Southern, Western Views of Islam in the Middle Ages (1962; Cambridge,Mass./London:Harvard

Univ. Press, 1978), pp. 8-9. These lectures were delivered at Harvardin April 1961.

This content downloaded from 87.161.248.86 on Mon, 7 Apr 2014 05:08:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

658 SITUATINGARABIC SCIENCE

important,politically influentialpart of Baghdad's intellectual elites. Two other groups

within the empire (and concentratedmainly in Syria, Iraq, and Persia) had maintaineda

long-establishedtraditionof Hellenized Syriac learning.One consisted of Christianphy-

sicians and Christiantheologians, who continuedto pursue their interests in Greek logic

and philosophy in scatteredmonastic schools; the otherwas the pagan Sbians of Harran,

in northernMesopotamia,an ancient Semitic group whose astralreligion connectedthem

to Hellenistic astrology and astronomyand to Hermeticism. It was from these two last

groupsthat the Abbasids were able to recruitthe scholarswho carriedout the translations

of Greek medical, philosophical, and mathematicalworks into Arabic, either from pre-

existing Syriac versions or directly from the Greek.

The survival of these pockets of Hellenic learningduringthe first centuriesof Islamic

rule in the Middle East andAsia, althoughscatteredand limited at firstin scope andappeal,

ensured a certain continuity with the classical tradition-a continuity that was largely

lacking, for example, in the case of the "Renaissanceof the Twelfth Century,"when

Europeanscholars first had to journey to the edges of Western Christendomto acquire

Arabicand Greeklearningfrom acrossthe borderswith Islam andByzantium.In the earlier

Middle Easternepisode, this continuitymeantthe immediateavailabilityof texts, in Greek

or Syriac versions, and of translatorsalready conversantwith these languages and with

Greekthoughtitself in a numberof scientific,medical, and philosophicaldisciplines.And

although much additionalGreek materialwas later to be brought over the borderswith

Byzantium,the continuitywith the Greco-Syriactraditionhelps to explain the high level

of competence, even sophistication,that characterizedscientific writings in Arabic from

an early period that overlappedthe translationmovement.

One might then say, and with muchjustification,thatthe stage was set, at a certainplace

and time, for the translationmovementthatquickly acquiredunprecedentedproportions-

unprecedentednot only in the Middle East but in the world at large. But in orderto explain

the momentum,scope, and multiple dimensions of that movement, it is necessary to go

beyond the availabilityof favorableconditions, and even beyond the importantconsider-

ation of practicalexpectations that must have loomed large at least in the minds of the

Muslim patrons.Islamic religion had introduceda new ideology with sweeping and uni-

versalist claims. Already during the swift expansion of Islamic conquests, that ideology

had come into directcontactwith a large varietyof creeds (Jewish, Christian,Zoroastrian,

Mazdian,Manichaean,etc.) with which it inevitablycollided and againstwhich it had not

merely to defend but-much more importantly-to define itself, often in terms borrowed

from its opponents. The result was a huge intellectual ferment, centered especially in

multiculturalIraq,to which the movements of Islamic theology, philosophy, and science

owed their birth.

Or, should we not rathersay, more accurately,thatthe creationof these fields of thought

representedthe responses of so many groups of individualsto aspects of what was, in the

context of religion and politics and power and the variety of competingways to salvation,

a very complex andlive intellectualatmosphere?Withregardto the creationof the tradition

of science and philosophy in Islam, I am temptedto borrow an obsolete term, aspecting,

in orderto refer to the way in which individualsin a given cultureaspect anotherculture

as they direct their gaze to the other from their own location. Aspecting in this sense is

conditioned both by the interests, aspirations,and aptitudesof the aspecting individuals

and by the accessible aspects of the viewed culture,that is to say, the aspects thathappen

to be disclosed to them by the accidents of history or by their further,determinedeffort.

Thus, for example, through the Sabians of Harran,Muslim thinkers were able to view

This content downloaded from 87.161.248.86 on Mon, 7 Apr 2014 05:08:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A. I. SABRA 659

facets of Hellenistic thought that might not have been available to them by way of the

Christiantheologians,who had alreadymadetheirown choices fromtheirown standpoints.

And, as has been plausibly suggested, the absence of Greek literatureand Greek histori-

ographyfrom the translatedcorpusmay be attributableto a lack of acquaintanceor serious

intereston the partof the Christiantranslators.4In a similarway, the twelfth-andthirteenth-

century Arabo-Latintranslationsin northernSpain were understandablylimited to the

types and the levels of the learning that was currentlyavailable in Al-Andalus, with all

the features of that learning that had undoubtedlybeen shaped by a combinationof cir-

cumstancespeculiarto Al-Andalus.5

The scholarsof eighth- and ninth-centuryIraqlooked east to Persia and Indiaand west

to Greece and especially to Alexandria.Both looks deeply affected the characterof Arabic

science, especially in mathematicsand astronomy,in both of which we find combinations

of identifiableelements from the East and the West. But it was the westward gaze that

proved most enticing and, as it turnedout, most consequential.Some years ago I used the

term appropriationto characterizethe attitudeof Muslim scholarsand patronswho made

it their business to get hold of and make their own what they called "the sciences of the

ancients,"an expression that clearly revealed a sense of distance in time between them-

selves, as "the modems" (al-muta'akhkhirun),and the appropriatedlegacy of "the an-

cients" (al-mutaqaddimun),even as the appropriatorsset about gaining possession of the

ancientlegacies with greatenergy.6Withoutaiming here to unfold the full meaningof that

sense of distance(which has frequentlybeen misinterpretedand misused in modem schol-

arship),let me indicatebrieflyhow it was understoodand evaluatedby some of those who

promotedor participatedin the appropriationdrive of the ninth century.

I will not expand,not even briefly, on the role of the Abbasidcaliph al-Ma'miin,whose

contributionsas a patronof astronomicalresearchand as the one who turnedthe library

of Greekphilosophicalsciences collected by his immediatepredecessorsinto an organized

center of translationare well known. But I must emphasize the significance of his deep

involvementin a theological disputethatpromptedhim to initiatethe "inquisition"against

the conservative opponents of the Mu'tazilite school of kalam (or "theology")that he

favored. It is naturalto think of a connection between al-Ma'miin's supportof the Mu'-

tazilite emphasison the role of reasonin elucidatingreligious dogma and his championing

4Paul Kunitzsch, "The Two Movements of Translationinto and from Arabic and Their Importancein the

History of Thought"(in Arabic), Zeitschriftfur Geschichte der Arabisch-IslamischenWissenschaften,1987/

1988, 4:93-105.

5Guy Beaujouan, "The Transformationof the Quadrivium,"in Renaissance and Renewal in the Twelfth

Century,ed. Robert L. Benson and Giles Constable (Cambridge,Mass.: HarvardUniv. Press, 1982), pp. 463-

487, on p. 465: "Having found its principal Arabic sources in Spain, medieval Western science obviously

reflected, at the start,the choices of the Hispano-Moslemculture.The lack of interestin abstractmathematics,

the predominanceof astronomyand astrologyin the early translations,the relativelylate date of the Arabo-Latin

versions of Aristotle's naturalphilosophy, the failure to use importantworks by easternArabic scholars:all are

explained by the evolution of Arabic science in the Iberian peninsula, with its peculiarities of history and

geography,its particularistpride within the Islamic world, its conditioningby the oppressive dominationof the

Malikitefakihs."In additionto the referencescited by Beaujouansee A. I. Sabra,"TheAndalusianRevolt against

Ptolemaic Astronomy: Averroes and al-Bitriujl,"in Transformationand Tradition in the Sciences: Essays in

Honor of L Bernard Cohen, ed. EverettMendelsohn(Cambridge:CambridgeUniv. Press, 1984), pp. 133-153,

rpt. in Sabra,Optics,Astronomy,and Logic (Aldershot:Variorum,1994); Julio Sams6, Islamic Astronomyand

Medieval Spain (Aldershot:Variorum,1994), esp. Chs. 1 and 12; and R. S. Avi-Yonah, "Ptolemyvs. al-Biit4iji:

A Study of Scientific Decision-Makingin the Middle Ages," Archives Internationalesd'Histoire des Sciences,

1985, 35:124-147.

6A. I. Sabra,"TheAppropriationand SubsequentNaturalizationof GreekScience in Medieval Islam,"History

of Science, 1987, 25:223-243, rpt. in Sabra,Optics,Astronomy,and Logic.

This content downloaded from 87.161.248.86 on Mon, 7 Apr 2014 05:08:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

660 SITUATINGARABIC SCIENCE

of Greekscience andphilosophy.We areeven given a hintof a contemporaryinterpretation

of such a connection in a story thatcirculatedin tenth-centuryBaghdad,if not earlier.The

story reporteda dreamthat the caliph was alleged to have had, in which none other than

the pagan Aristotle appearedas an instructorto the "overawed"Commanderof the Be-

lievers. In answerto al-Ma'miin'squestion aboutthe natureof "thegood" (al-hasan), the

Greekphilosopheridentifiesits authoritativesource in the firstplace with reason(al- 'aql),

in the second place with "the (religious) law," and in the thirdplace with what is accepted

by "the majority of people" (i.e., the majority of legal scholars). In one version of the

dreamAristotle ends by urging his Muslim studentto upholdthe unity of God (wa'alayka

bi l-tawhid) !7 Affirmationof the unity of God (tawhrd)was the first article in the Mu'ta-

zilite credo, and it was in the name of divine unity, as interpretedby reason ('aql), that

the Mu'tazilamaintainedthe doctrine,which al-Ma'miinandhis two immediatesuccessors

sought to impose on the conservativelegists, thatthe Qur'an-as the speech of God-had

not existed from all eternity but was created. The suggested connection between Greek

rationalismand Islamic Mu'tazilismis impossible to overlook.

Turningnow from the patronal-Ma'miinto leading Muslim intellectualsof the period,

one quickly detects an attitude of openness and gratefulness to the recently imported

wisdom, mingled with a feeling of high optimism and a certain trust in humanismthat

was quite pronounced.The majorArabic prose writer of the period, and one of the most

influentialfigures in the history of Arabic literature,al-Jahiz(d. 869), was also the leader

of a prominentbranch of Mu'tazilism named after him (al-Jahiziyya) and a reader of

Aristotle. In one of his most importantworks, the monumentalBook of Animals, which

owed much to Aristotle and which he dedicatedto the famous wazjr Ibn al-Zayyat(who

served the Abbasid court in the reigns of al-Ma'miin's successors, al-Mu'tasim and al-

Wathiq [833-842, 842-847]), he thanks "the ancients"(i.e., the Greeks) for their consid-

erableintellectualcontributionto the scantypossessions of the people of his time andplace

and culture.He wrote, in a passage that is characteristicfor its utter lack of inhibitionor

ambiguity: "Our share of wisdom would have been much reduced, and our means of

acquiring knowledge weakened, had the ancients not preserved for us their wonderful

wisdom, and their various ways of life, in writings which have revealed what was hidden

from us and opened what was closed to us, therebyallowing us to add their plenty to the

little we have, and to attainwhat we could not reach without them."8

An exact contemporaryof al-Jahiz, and arguablythe single most importantfigure in

this phase of appropriation,the celebratedMuslim philosopher,scientist, and mathemati-

cian al-Kindli(d. ca. 870), was a member of the Arab nobility (his grandfather,we are

told, was amrrof al-Kulfain southernIraq).As a tutorto a son of Caliph al-Mu'tasim,he

was much closer to the Abbasid court than al-Jdhiz. In his work On First Philosophy,

dedicated to al-Mu'tasim, we find strong acknowledgmentof the accomplishmentsof

ancientGreece that is combinedwith the assertionof truthas the universalgood thatmust

be sought out wherever it may be found, in additionto a clear concept of the growth of

knowledge as a process of accumulationthat requiresthe cooperative effort of different

peoples and successive generations.9These were the deep convictions of a true devotee,

I Ibn al-Nadlim,al-Fihrist, ed. Gustav Fliigel (Leipzig, 1871-1872), Vol. 1, p. 243 (also in an edition by Rid.I

Tajaddud[Tehran,1971], pp. 303-304).

Al-Jahiz, Kitab al-Hayawan, ed. 'Abd al-Salam Hariin, 2nd ed., Vol. 1 (Cairo: MaktabatM. al-Babi al-

Halabl, 1965), p. 85.

9 Alfred Ivry, Al-Kindr'sMetaphysics:A Translationof Yaqiib ibn Ishaq al-KindT'sTreatise "On First Phi-

losophy" (Albany: State Univ. New York Press, 1974); Al-Kindl, FTal-sina'a al-'u;ma, ed. 'Azrir Taha al-

Sayyid Ahmad (Cyprus:Dar al-Shabab, 1987); and Al-Kindli,"FThudiudal-ashya wa rusiimiha,"in Rasa'il al-

KindTal-falsafiyya,ed. M. AbiuRida, Vol. 1 (Cairo:Dar al-Fikral- Arabl, 1950), pp. 163-180.

This content downloaded from 87.161.248.86 on Mon, 7 Apr 2014 05:08:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A. I. SABRA 661

and they carriedwith them an entireHellenic or Hellenistic world view, a distinctconcept

of wisdom in both the theoreticaland practicalsenses (also borrowedfrom the Greeks),

and a sense of mission on the partof the authorto do his utmostto disseminatethe ancient

and especially Greek heritage in his milieu. Both this world view and this concept of

wisdom, as well as the universalistcharacterof al-Kindli'smission, are recognizableHel-

lenistic themes. But we all know betterthan to push the continuitythesis too far-espe-

cially not in the directionof blatantessentialism:to look on al-Kindlias a latter-dayHellene

or Hellenist would be as helpful as the affirmation,found in Spengler's Decline of the

West,that the Pantheonbuilt by Hadrianin the second centurywas the first mosque ever.

Such a view of al-Kindi and other Muslims who sharedhis outlook in the ninth century

would tear them away from their unique position in history and from the role they con-

sciously andfreely chose to assumein the context of theirown culture.Al-Kind7i'smission,

as he understoodit, clearly reveals his adoptionof the humanistictheme, his avowed intent

being, as he said, "the perfecting of our [human]species."10But as one who lived in an

Arabicculture,his immediaterole, as he also conceived it, was to introduceand,he hoped,

to convert his Arabic-readingcontemporaries(ahl lisanina: the people who speak in our

tongue) to the Greek wisdom that had captivatedhim-a task that he actuallyundertook

to achieve by producinga huge numberof Arabic epitomes and adaptations,with supple-

mentary clarificationsand additions when necessary, of a very large number of Greek

disciplines of science and philosophy. This was a preposterouslyoptimistic project for

anyone to envisage; but not only was al-Kindliable to carryit out, whethersinglehandedly

or with the help of others, it proved to be remarkablysuccessful-so successful, in fact,

as to make him truly worthy of the reputationhe quickly gained as one of the foundersof

the Arabic traditionin philosophy and science.

With these three pivotal figures in mind (and there are others that can be broughtinto

considerationalong with them), I am inclined to portraythat crucial phase in the appro-

priation process as the accomplishmentof individualswho experiencedthe intersection,

at a certainplace andtime, of threemajormovementsat work-namely those of Hellenism,

Arabism, and Islamism. By viewing ninth-centuryBaghdad as a point of intersectionin

the mannerI have tried to outline, I hope to renderuseless such questions as whetherthe

scientific traditionthen being establishedwas essentially Arabic, Islamic, or Greek" and

to open the way for empiricalresearchaimed at identifying the actual workings of these

movements as revealed in the writings and recordsof those individualswho experienced

and respondedto them. No doubt there is reason here to celebratethe creative genius of

a moment in the history of civilization, but my overridingaim is to direct attentionto the

complexity and richness of that extraordinarymoment and away from the misleading

"essences."9

THREE LOCI OF SCIENTIFIC ACTIVITY IN ISLAM: THE COURT, THE COLLEGE,

AND THE MOSQUE

Abundantrichness also awaits the empirical investigatorinto the subsequentcourse of

scientificactivityin Islamiccivilization.WhatI havejust describedis the attitudeof certain

10"idh kunnahirasan 'ala tatmiminaw'ina":al-Falsafa al-dla, in Rasitil, ed. AbiuR7da,Vol. 1, p. 103. For

the translationsee Ivry, Al-KindT'sMetaphysics,p. 58. See also Spengler, Decline of the West (cit. n. 2), Vol.

1, p. 211.

" ErnestRenan,L'islamismeet la science, 2nd ed. (Paris:CalmannLdvy, 1883).

This content downloaded from 87.161.248.86 on Mon, 7 Apr 2014 05:08:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

662 SITUATINGARABIC SCIENCE

individualswho were favorably disposed to the importedknowledge and who played an

active partin bringingaboutwhat laterprovedto be a long-lastingtradition.But, of course,

a few first steps, even significantones, might not have been followed by othersin the same

direction or with the same determinationand vigor. And, indeed, there were other, con-

temporaryindividualsand groups whose markedlydifferentor contraryattitudesand in-

tellectual commitments,then and in laterperiods, did much to shape the course of Arabic

science. As I turn now to later developments,our story acquiresa degree of complexity

that I cannot hope to convey in a lecture. But I shall try to give you a sense of it. It is a

complexity thatfurtherillustratesthe usefulness of the methodologicalconcept of locality,

and it will lead me at the end of my talk to pose the general question of whether,and in

what sense, Arabic science should be investigatedas a single enterprise.The storyunfolds

in at least threedistinctbut by no means isolated loci whose differentstructuresandmodes

of operationand interactionhave yet to be explored from the standpointof our subject.

These loci are the college or institutionof higher learning,the royal or princelycourt,and

the mosque. I shall arbitrarilyignore the hospital as a result of excluding medicine from

my presentaccount.'2

I will begin with the college, and in orderto bring you closer to an unfamiliarsituation

I will startwith two general observationsby way of comparisonwith more familiarepi-

sodes. The first is this: as far as science and philosophy are concerned, the European

Renaissance of the sixteenth century was in part a reaction, which became more pro-

nounced in the seventeenthcentury, against patternsof thought and argumentassociated

with medieval "scholasticism."In Islamic history, events followed the reverse order:the

"renaissance"(if that is the right word) came first, in the ninth and tenth centuries,and a

form of scholasticismfollowed, though not immediatelyand not uniformlyin all partsof

the Muslim world. My second observationpoints to anothercontrastbetween Islam and

medieval Europethat is cruciallyimportantbut more difficultto describebriefly.In Islam,

whether in ninth- and tenth-centuryBaghdad, eleventh-centuryEgypt and central Asia,

twelfth-centurySpain, thirteenth-centuryMaraghain northwesternIran, or fifteenth-cen-

tury Samarkand,the major scientific work associated with the names of those who were

active at those times and places was carried out under the patronage of rulers whose

primaryinterests lay in the practicalbenefits promised by the practitionersof medicine

and astronomyand astrology and applied mathematics.Many of these practitionerswere

also prolific writers on "philosophy,"a mode of thinkingknown by the Arabicizedterm

falsafa and characterizedto a large extent by a mixture of Aristotelianand Neoplatonic

doctrinesand forms of argument-the kind of mixturewe find, for example, in the works

of al-Kindli,al-Fdrdbl,and Avicenna. In those circumstancesscience and "philosophy,"or

falsafa, were secular activities that were practiced,developed, and propagatedas rational

inquiries completely independentof any religious authority-which, of course, did not

prevent the proponentsof this autonomous,self-legitimizing mode of thinking from of-

fering their own rationalistic(i.e., Hellenic) interpretationsof religious doctrinessuch as

revelation or prophecy or providence and of religious institutionssuch as law. After all,

falsafa was an all-embracingworld view that claimed the right to scrutinizeand account

for everythingwithin the sphere of humanexperience, including religious experience. In

12 The only "excuse"for this exclusion is to avoid further

complicatingan alreadycomplex picture.No story

of Arabic/Islamicscience or philosophyis complete withouttakinginto accounttheirrelationto medicalthought,

the effect of medical patronage,the place of science and naturalphilosophy and logic in the institutionsof

medical educationand practice, and the role of Galenic writings as a source of ideas and doctrinesthat shaped

the minds and attitudesof Islamic philosophersand scientists, as well as physicians.

This content downloaded from 87.161.248.86 on Mon, 7 Apr 2014 05:08:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A. I. SABRA 663

one case among the prominentdevotees offalsafa, that of al-Kindli,a seriouscompromise

was made by renouncingthe Greekdoctrineof the eternityof the world in favor of creatio

ex nihilo. But unlike most of their Christiancounterpartsin medieval Europe, Islamic

philosophers(the self-styledfalasifa) and philosopher-scientistsin that Greek sense were

not "theologians"or members of religious orders. The one major exception, of sorts, is

the twelfth-centuryAndalusianAverroes, who came from a celebratedtraditionalfamily

of Malikitejurists and practicedthe Malikite version of Muslim law as a judge, but who

neverthelessbelieved himself to have inheritedthe mantle of Aristotle. I shall come back

to him later.

Now, Islamic "theology,"or what has come to be known in Westernscholarshipby this

name, followed a differentcourse-with important,indeed far-reachingconsequencesfor

the developmentof both science andfalsafa. It began to make a conspicuous appearance

in the eighth century (the second Islamic century),well before the patronizedtranslation

movement got under way, as the activity of spontaneouslysproutinggroups of Muslim

intellectuals in the urban centers of Basra and Baghdad who immersed themselves in

probingdiscussions (kalam: speech, discussion, argument),obviously driven by their in-

terestin currentreligious and political controversies.They graduallydeveloped somewhat

varied and sometimes seemingly indecisive but sophisticatedand sophisticatedlyargued

doctrinesconcerninga comprehensivearrayof subjectsthatrangedall the way from God

and his relation to man and the world, to questions of epistemology and morality and

political leadership,to subtle and difficult speculationsabout the ultimateconstitutionof

all createdbeing, which they characteristicallyproposedto understandin atomisticterms.

Thefalasifa laterdubbedthese kalampractitionersas religious apologists,therebyseeking

to downgradetheir rivals or, if possible, to circumscribetheir role by subsuming their

enterpriseunderthe authorityof falsafa. I3

There can be no doubt that the early practitionersof kalam, the mutakalliman,were

influencedby a multiplicityof pre-Islamictraditionsin ways thatstill remainmostly veiled

in obscurity.But whateverthe remote sourcesof theirideas, and despitetheirfundamental

concern with the elucidationand critiqueof religious tenets, it is my conviction (which I

share with a few others) that the discourse of the early "school"of the Mu'tazila,the one

favored by al-Ma'mtin,and of the later and subsequentlydominantAsh'arites,represents

an importantturnin the historyof philosophicalthought-one that gave rise to new styles

of thinkingthat seriously challenged the Aristotelianismand Neoplatonism of falsafa by

proposing a thoroughgoingatomism that viewed the world as a creative process. It was

this new philosophy, the "philosophyof the kalam,"as HarryWolfson called it,'4 that, in

the Ash'arite version, later found its way into the colleges of higher education, the so-

called madrasas that ultimately spreadwide and far over the Islamic world as endowed

or charitableinstitutions, having been first introducedon a large scale in the eleventh

century by the Sunnite Saljiiqs in Iraq and Persia as part of a political agenda and in

response to the Ism'Tll-propagandaemanatingfrom FatimidEgypt and Syria.

The madrasas, it should be noted, were first conceived of as primarilyschools of law,

13 A. I. Sabra,"Science and Philosophy in Medieval Islamic Theology: The Evidence of the FourteenthCen-

tury,"Z. Gesch. Arab. Islam. Wiss., 1994, 9:1-42.

14 HarryAustryn Wolfson, The Philosophy of the Kalam (Cambridge,Mass/London: HarvardUniv. Press,

1976). The view of kalam as religious apologetics has been prevalentin modem literaturebut is currentlybeing

revised. See RichardM. Frank,"The Science of Kalam,"Arabic Sciences and Philosophy, 1992, 2:7-37; and

Sabra,"Science and Philosophy in Medieval Islamic Theology."

This content downloaded from 87.161.248.86 on Mon, 7 Apr 2014 05:08:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

664 SITUATINGARABIC SCIENCE

an emphasis that they retainedthroughouttheir history.'5But, as creationsof privateen-

dowments,they generallyenjoyed a degree of informalitythatallowed for a variablerange

of intellectual pursuits that depended on local circumstancesand the interests of their

professors and their sponsors. Many, perhapsa large number,of the madrasas included

some teachingin arithmetic,algebra,astronomy,and logic as partof the intellectualequip-

ment of the practicingjurist, along with the indispensable disciplines of language and

rhetoric.Kalam,as a study of the "fundamentaltenets of religion"(usul al-dTn),performed

the dual function of supplying a superstructureof theory for the rest of the "religious

sciences" as well as a substitutefor Greek metaphysicsand naturalphilosophy.

Combiningthese two generalobservationsshould now help us to appreciatethe follow-

ing result. The sciences of the Greeks, which were first welcomed in Islam along with

Greek theories of cosmology and epistemology and metaphysics (be they Hellenic or

Hellenistic), eventually came to be confrontedin the madrasasby a homegrownreligious

philosophy thatclaimed to develop viable alternativesto the Greekparadigms.Thatmuch

we can say in light of what we already know. But there is no end to the questions that

have yet to be examined.When and where and in what circumstancesdid thatprocesstake

place? Was it one process or many? How did kalam manage to subduefalsafa, given the

tentative beginnings of the former and the originally strong and full-grown natureof the

latter?How much, if anything,of falsafa doctrinesand forms of argumentwas absorbed

into kalam? How didfalsafa react to the assault of the mutakallimdn,given thatfalsafa

continuedto pursue its activities long after the advent of the madrasas, at least in some

parts of the Muslim world? And-the question of special importancefor the historianof

science-what was the effect of the kalam point of view on the disseminationand devel-

opment of scientific disciplines such as cosmology and astronomy,about which the mu-

takallimtinhad a lot to say as an integralpartof their own world view?

None of these questions can be answereda priori.They are all empiricalquestionsthat

requireempiricalresearch.Some of my colleagues, I am happyto say, are now beginning

to tackle them in earnest.Othersare reluctantto embracethem, being afraidof the possible

danger of diverting too much attention from the vast quantities of scientific texts that

remain to be edited and analyzed. The skeptics have a point, and I share their concern.

But this is not an either/ormatter.As for the argumentthat "we do not yet know enough

to ask the big questions,"my answer is this: it is only by attemptingto formulateappro-

priate questions that can be fruitfully examined in light of what we now know that we

make it possible for others to come up with deeper and more probing questions in the

future.We do not know much (that is for certain),but the day when we know "enough"

will never come. On the otherhand,by altogetherabandoningall programsof full-fledged

historicalresearch,we only tempt others to fill the vacuum with easy and useless essen-

tialist generalizations.

The madrasas were not, therefore, in general a locus where scientific research was

promoted for its own sake, but one in which science was interpretedand judged and

15 The

literatureon the madrasa is growing rapidly, but see especially the wide-rangingstudies of George

Makdisi: "Muslim Institutionsof Learningin Eleventh-CenturyBaghdad,"Bulletin of the School of Oriental

and African Studies, 1961, 24:1-56 (rev. by A. L. Tibawi, ibid., 1962, 25:225-238), and The Rise of Colleges:

Institutionsof Learning in Islam and the West (Edinburgh:EdinburghUniv. Press, 1981). Most of the recent

publicationsare concerned with the Mamlik period (for which there is abundantmaterial),but they have not

yet directed special attentionto the question of the place of science and philosophy in the madrasas. This must

be due in partto the long-held assumptionthat science and philosophy had no place in the madrasas, which is

not quite true, as is now being realized.

This content downloaded from 87.161.248.86 on Mon, 7 Apr 2014 05:08:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A. I. SABRA 665

presentedto a large group, indeed the vast majority,of educatedMuslims. When we talk

of scientificadvancein Islam,whetherin mathematics,astronomy,or experimentalscience,

we usually have in mind the contributionsof men who carriedout their work outside of

the madrasas with the supportof kingly patrons-men like al-KhwTrizml,al-Khayyami,

Ibn Yulnus,Ibn al-Haytham,al-Blrtinl,al-Tilsi, and al-Shirazl.As always, there were ex-

ceptions-sometimes importantones, especially in the later period-and in some cases

the systems of patronageand madrasa even seem to merge, eitherpartially,or even com-

pletely, as for example underUlugh Beg's initiativein fifteenth-centurySamarkand.Such

exceptions should direct our attentionto the significant overlap among all three loci of

courtpatronage,college, and mosque. But the generalpictureof scientificadvancein Islam

as a patronizedactivity holds.

What we are still far from understandingis how patronageworked in contexts that

obviously differed from one center of activity to another.Let me give an example with

referenceto two or three situationsaboutwhich we know a little more than aboutthe rest.

Consideragainthe pagan sage, Aristotle,who was said to have inspiredCaliphal-Ma'mun

and with whom the Malikite Muslim jurist Averroes identifiedhimself. In both cases we

encounteracceptanceof the authorityof an alien thinkerand of the intellectualvalues he

represented.In both cases a Muslim theological context was involved: Mu'tazilitekalam

in the earlier episode, and the religious ideology of the Almohad dynasty in the later

Andalusianepisode. But the theological commitmentswere differentin the two cases, with

ratherdifferentimplicationsfor the place and authorityof the law, and so were the patterns

of patronage.The differences were, moreover, enhanced by an emphatic self-conscious

Andalusianidentityvis-a-vis the rest of the Islamicworld.It is not surprisingthatAverroes,

as the intellectual who responded most powerfully to this Andalusian situation, should

develop a new theory of religious authority,a totally negative attitudeto kalam,and a new

valuationof his adoptedAristotelianismthat set him against his Peripateticpredecessors

and earlier mathematiciansin the easternpart of the Islamic world. It is, therefore,with

referenceto this special context in all its geographical,political, and intellectualparticu-

laritiesthat we should try to gain a historicalunderstandingnot only of Averroes'rebuttal

to the attack launched by the Easternal-Ghazali against the falasifa, but also of his im-

portantand explicit divergencesfrom fellow-faylasufslike Avicenna or from a recognized

mathematicalauthoritylike Ibn al-Haythamand of his ultimaterejectionof the hitherto-

dominantPtolemaic astronomy.16

Similar,or greater,contrastswith regardto attitudes,patternsof relationsbetweenpatron

and client, and implicationsfor the practiceof science are what we should expect to find

as we turn our attentionto laterperiods. For example, soon afterthe Mongol Ilkhanshad

capturedBaghdad in 1258, thus bringing the Abbasid caliphate to an end, their leader

Hiilagulwas persuadedto establish an observatoryat Maraghain northwesternIran, an

event that markedthe beginningof one of the longer-lastingand importantepisodes in the

history of Arabic science. Most of the scholarswho were soon to be gatheredat Maragha

were Muslims (thereare reportsof one or more Chinese scholars).The man put in charge

of organizingthe new enterprisewas Nasir al-Din al-Tilsi, a Persianfrom Tus with serious

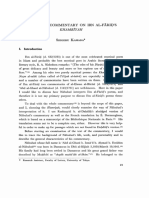

interestsin Shl'ite theology and Avicennan philosophy. (See Figure 1.) At age fifty-five

when he surrenderedhimself to the Mongols upon their captureof the Isma'Ili stronghold

of Alamut, he was alreadyfamous as a scholarand known to the Mongols as a competent

astronomerand astrologer.Two other scholars, both of them Sunnis, were broughtover

16 Sabra,"AndalusianRevolt against Ptolemaic Astronomy"(cit. n. 5).

This content downloaded from 87.161.248.86 on Mon, 7 Apr 2014 05:08:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

666 SITUATINGARABIC SCIENCE

....F,' ^" .... '.'........I l. .. ;. . f

*. si. .

........

Figure 1. NasTral Din al-Tujs,andcolleagues at the Maraghaobservatory.(MSF1418, early

sixteenthcentury IstanbulUniversityLibrary.)

from Syria.One of them Mu ayyadat Din al-'Urdl,had a reputationas a buildingengineer

and instrument-maker.The other, the mathematicianMuhyi al Di-nal Maghribiat Anda-

lUS17,was captured by the Mongols during their campaign in Synia in 1259 1260. He

managed to save his life only by presentinghimself to his captors as an astrologerwho

could be of use to "the lord of thieearthi,"thiegreat Mongol Khan.17 The Mongol patron

of the astronomicalenterpniseat Maraghawas not Muslim, and his interestin the work of

the observatorywas undoubtedlyastrological.The immediategoal was to producea new

"7The story of al-Maghribi'scaptureis told by Barhebraeus(in Ta nr-kh mukhtasaral-duwal), who heard it

from al-Maghribiin Maragha;see A. I. Sabra, "Simplicius's Proof of Euclid's ParallelsPostulate,"Joumal of

the Warburgand CourtauldInstitutes, 1969, 32:1-24, esp. pp. 13-14, rpt.-in Sabra, Optics, Astronomy,and

Logic (cit. n. 5). On al-'Urdi see George Saliba, ed., TheAstronomicalWorkof Mu 'ayyadal-Dmnal- 'Urdl.:Kitib

al-Hay a (Beirut:Centerfor Arab Unity Studies, 1990), pp. 27-30.

This content downloaded from 87.161.248.86 on Mon, 7 Apr 2014 05:08:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A. I. SABRA 667

.}..X o~~~ ... .....1

\i~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

/t

.............

.XtS,*|

.{{.

Figure 2. Giant armiillaryset up in the open air at the sixteenth-century Istanbul observatory. (MS

1404, late sixteenthcentury,IstanbulUniversityLibrary.)

set of astronomicaltables, based on new observations,of the type that had been used by

Arabic astronomers and astrologers for planetary predictions since the time of al-Ma'miin.

The Zj-i Il-Khani, as the new Persian handbook came to be known, was not completed

until 1272, after Hulagu's death. But in the meantime,and for several decades afterward,

the scholars at Maraghaand nearby Tabriz were able to pursue their individualinterests

in theoretical astronomy and in various branches of mathematics. It was in this singular

situation that the aporetic research in planetary theory, which was initiated by Ibn al-

Haythambefore the middle of the eleventh century and had attractedthe attentionof a

few individualscholarsin Asia and Syria, first found a sustainingatmosphere;and it was

from here that ffiis type of research later spread further east, south, and west, where it was

cafried on in different terms or with different emphases as scholars with different com-

mitmentsrespondedto changing contexts. (See Figure 2.)

This content downloaded from 87.161.248.86 on Mon, 7 Apr 2014 05:08:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

668 SITUATINGARABIC SCIENCE

The phenomenonof the mosque as a significant locus of scientific activity came into

being at about the same time as the establishmentof the Ilkhanidrule in Iran and Iraq,

being associatedwith the ascension to power of the Mamluiksin Egypt and Syria in 1250.

Most of what is now known aboutthis importantphenomenonis due to David King, whose

work over the last twenty years has been responsiblefor puttingthis phenomenonon the

map of Arabic science.18 It was the longest-lastingepisode within the traditionof Arabic/

Islamic science, having continuouslyenduredin some of the major mosques all the way

up to the nineteenth century, and it possessed interestingfeatures that distinguish it in

several ways from courtpatronageand the madrasas, the two otherloci of consequence.19

Though primarilya place of worship, the mosque, from its inception, and as distin-

guished from the madrasa that was sometimes attachedto it, often served as a forum for

propagationand discussion of subjectsrelatedto Arabiclanguage,grammar,and rhetoric,

as well as the vital issues of law, religion, andpolitics. Throughthe introduction,apparently

for the first time underthe Mamluiks,of the office of muwaqqit,the timekeeperin charge

of regulatingthe times of the five daily prayers,a place was createdfor the utilizationof

one form of scientific knowledge in a permanentreligious institution.

Strictly speaking,it would be wrong to consider the muwaqqita "professional"astron-

omer. His institutionalrole in the mosque was not to pursue the goals of astronomyas

these had been defined and elaboratedby Arabic astronomerssince the ninth centurybut,

as is clearly indicated by his status title, to offer reliable guidance to his local Islamic

communitywith regardto definitereligious observances(mainlyprayertimes) as specified

by religious law. This function the muwaqqitnonetheless performedin his capacity as an

expert in what was called "the science of reckoning time" ('jim al-mTqdt)by means of

exact astronomicalcomputations,and this distinguishedhim from the traditionalmu'ezzin

(the man who called for prayer),who relied on traditionalprescriptions.The main task of

the muwaqqitwas thereforeto use the methodsof sphericalastronomyin orderto construct

tables, usually computedfor a certainlocality or latitude,that would enable anyone who

could operate a simple observation instrument(such as an astrolabe or a quadrant)to

determinethe time of day or night from the altitudeof the sun or a star.A muwaqqitmight

also possess the skill to constructsuch instruments.And some distinguishedmuwaqqitsin

the thirteenthand fourteenthcenturiesaccomplishedthe impressivefeat of providinguni-

versal solutions of timekeeping problems (indeed, all problems of spherical astronomy)

for all latitudes. One muwaqqit,the fourteenth-centuryIbn al-Shatir(d. ca. 1375), who

was attachedto the Umayyad mosque in Damascus, venturedinto the area of theoretical

astronomyto produce the most complete solution to the equant problem, which Ibn al-

Haythamhad forcefully pointed out as a threatto the principles of Ptolemaic astronomy

and which was diligently pursuedby mathematicalastronomersin the thirteenthcentury.

These were all accomplishmentsthat must be regardedas accomplishmentsin astronomy

proper,regardlessof their institutionalsetting. And the same can be said of other equally

impressive investigationsaimed at determiningthe directionof Muslim prayer.As in the

case of timekeeping, these investigations also culminated in universal solutions for all

latitudes.

And yet it is noticeable, as King has pointed out, that the legal scholarsand interpreters

18 David King, "TheAstronomyof the Mamluks,"Isis, 1983, 74:531-555; and King, Astronomyin the Service

of Islam (Aldershot:Variorum,1993).

'9 The distinction has to be maintaineddespite occasional or even frequent overlappings, as, for example,

when a local rulerwas responsiblefor the appointmentof a favored professorin a madrasa.

This content downloaded from 87.161.248.86 on Mon, 7 Apr 2014 05:08:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A. I. SABRA 669

of the religious law continuedto apply the simpler considerations,based on observations

of twilight and horizonphenomena(rising and setting)or of shadowlengths, leaving alone

the sophisticatedmathematicaltreatises,which they "generallyconsideredto be too com-

plicated or even completely irrelevant."20 This is not really surprising(mathematicalpre-

cision need not be considered a prerequisiteof religious piety!), but it does renderprob-

lematic the concept of the muwaqqit'smathematicalwork as "serviceto religion."On the

other hand, the theoreticaltriumphof Ibn al-Shatirin planetarytheory does not seem to

have elicited serious attentionfrom othercontemporarymuwaqqits,and this appearsto be

the resultof the fact thattheirinstitutionalposition did not demandor encouragetheoretical

ventures for their own sake. Such paradoxesmay simply reflect our present, inadequate

knowledge of the circumstancesin which a new institutionalstructurebroughttogether

mathematicaland religious interests.But whateverthe correctunderstandingof these par-

adoxes might be, it would be gratuitousto regard the work of the muwaqqitin aiding

religious ritualas constituting"the essence of Islamic science" (as King puts it)21 or even

as the most revealing aspect of scientific activity in Islam. To propose such a view may

have the advantage of highlighting the uniqueness to Islamic civilization of a certain

emphasis on some programsof astronomicalresearch.But the disadvantagesof this pro-

posal are also glaringly conspicuous. It disregardsthe full extent of scientific researchin

Islam, and it ignores the characteristiccomplexity of Islamic civilization itself by neglect-

ing the variety of religious attitudeswith regardto the status, the function, and the value

of scientific knowledge. And it might appearto equate "Islamic science" with narrowly

circumscribedprogramsthat largely developed within the confines of an institutionwith

no commitmentto "science" as such, and this alone would tend to obstructor prejudice

vital questions about scientific practice in Islam by identifying a single locus of activity

with a widespreadand extremely complex phenomenon.And, of course, it would again

open the way into the trapof essentialism.

To come finally and very briefly to the generalquestionformulatedearlier:Was Arabic

science one or many? A similar question has sometimes been asked with reference to

Islamic art, where manifest varieties of styles and functions are displayed in the artifacts

and architecturalmonumentsof the vast Islamic world. As far as science is concerned,it

seems to me that importantconsiderationslead us to say that we have to do with a single,

unitarytradition.These are considerationsof language, which-for science and philoso-

phy-was for the most part one language (Arabic), and of Islamic religion as an ever-

present point of reference though not always a point of departure,in additionto consid-

erationsof the dominanceof dynasticrules over large regions for extendedperiodsof time

and the remarkableease of movetnientand communicationall throughthe Muslimworld-

a featureitself connected to religion and law and language. And, with regardto commu-

nication of learning, we must also keep in mind that crucial Chinese invention, paper,

which took the whole Islamic world by stormfrom the momentof its appropriationin the

middle of the eighth century.

One example will have to suffice as an illustrationof what I mean by these remarks.

Writing in fourteenth-centuryDamascus, Ibn al-Shatir linked his studies in theoretical

astronomyto those of earlier mathematicians,four of whom had worked in thirteenth-

century Maragha,one in eleventh-centuryEgypt, two in twelfth-centurySpain, and two

20

David King, "Science in the Service of Religion: The Case of Islam,"in Astronomyin the Service of Islam

(cit. n. 18), Ch. 1, p. 246.

21

Ibid., p. 245.

This content downloaded from 87.161.248.86 on Mon, 7 Apr 2014 05:08:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

670 SITUATINGARABIC SCIENCE

who originatedin thirteenth-centurySyria and North Africa. All had written in Arabic,

the languagein which Ibn al-Shatiralso wrote. The example is representativeof situations

that existed before and after Ibn al-Shatir,though there were cases in which Persianand

Turkishwere the languages of composition, especially in later times. But once we direct

our attentionto situations,as distinguishedfrom tradition,ourpictureand ourproblematic

will change with every case, as we turnfrom one set of circumstancesto anotherin which

individualchoices are made with referenceto specific problemsproposedby specific con-

texts. Not, of course, that traditionand individualresponse are separable:on the contrary,

the formerprovides an inseparablepartof the intellectualcontext in which the othermust

take place. When I startedto write this talk I hoped to be able to illustrateand perhaps

also to characterizein some generaltermsthe interplayof traditionandindividualresponse

with referenceto one or two episodes of Arabic science. In the end I am forced to leave

that subjectfor anothertime and place.

This content downloaded from 87.161.248.86 on Mon, 7 Apr 2014 05:08:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- L. D. Reynolds, N. G. Wilson Scribes and Scholars A Guide To The Transmission of Greek and Latin Literature PDFDocument347 pagesL. D. Reynolds, N. G. Wilson Scribes and Scholars A Guide To The Transmission of Greek and Latin Literature PDFFidel Andreetta100% (3)

- Everyday Gourmet - Rediscovering The Lost Art of Cooking PDFDocument208 pagesEveryday Gourmet - Rediscovering The Lost Art of Cooking PDFFidel Andreetta100% (5)

- Kamali Cosmological ViewDocument20 pagesKamali Cosmological ViewSam HashmiNo ratings yet

- Karamat Sidi Ahmad Ibn Idris p59cDocument2 pagesKaramat Sidi Ahmad Ibn Idris p59cibnbadawiNo ratings yet

- Historiography & The Sirah WritingDocument4 pagesHistoriography & The Sirah WritingSyed M. Waqas100% (1)

- Jahiz - Sobriety and Mirth PDFDocument14 pagesJahiz - Sobriety and Mirth PDFeksen100% (1)

- Banat Suad: Translation and Interpretive IntroductionDocument17 pagesBanat Suad: Translation and Interpretive IntroductionMaryam Farah Cruz AguilarNo ratings yet

- Students Guide To Aqida Al-Awaam 2nd Edition by Ramzy AjemDocument28 pagesStudents Guide To Aqida Al-Awaam 2nd Edition by Ramzy AjemRamzy AjemNo ratings yet

- Big Picture InvestingDocument80 pagesBig Picture InvestingFidel AndreettaNo ratings yet

- Reason Faith Philosophy in The Middle AgesDocument133 pagesReason Faith Philosophy in The Middle AgesFidel Andreetta100% (2)

- Alive Program-R XiDocument25 pagesAlive Program-R XiTimoy Cajes83% (6)

- TOPIC 3 Development of Education in Malaysia Pre - IndependenceDocument49 pagesTOPIC 3 Development of Education in Malaysia Pre - IndependenceBI20921 Kiroshini A/P MadavanNo ratings yet

- Whose Science IsDocument26 pagesWhose Science Ismybooks12345678No ratings yet

- Causality As A Veil The Ash Arites Ibn Arab 1165 1240 and Said Nurs 1877 1960Document17 pagesCausality As A Veil The Ash Arites Ibn Arab 1165 1240 and Said Nurs 1877 1960handynastyNo ratings yet

- Aristotelian Cosmology and Arabic Astron PDFDocument19 pagesAristotelian Cosmology and Arabic Astron PDFanie bragaNo ratings yet

- Jurjani Form Content ArchitechtureDocument71 pagesJurjani Form Content ArchitechtureimreadingNo ratings yet

- Muslim Mathematicians and Astronomers by F S QaziDocument20 pagesMuslim Mathematicians and Astronomers by F S QaziRizwan Kadir0% (1)

- Abdul Sheriff - The Swahili in The African and Indian Ocean WorldsDocument31 pagesAbdul Sheriff - The Swahili in The African and Indian Ocean WorldsFelipe PaivaNo ratings yet

- Conception of A Sign in The Philosophy of Hurufism by Nasimi and Naimi in The Context of Turkic-Azerbaijani TraditionDocument7 pagesConception of A Sign in The Philosophy of Hurufism by Nasimi and Naimi in The Context of Turkic-Azerbaijani TraditionInforma.azNo ratings yet

- Kitāb Al-Qānūn Al-Ma Sudī Vol3Document722 pagesKitāb Al-Qānūn Al-Ma Sudī Vol3Shaiful BahariNo ratings yet

- Ideas of Tolerance and Humanism in Imadeddin Nasimi's HeritageDocument7 pagesIdeas of Tolerance and Humanism in Imadeddin Nasimi's HeritageInforma.azNo ratings yet

- Do Women Need Feminism? MDI TranscriptDocument6 pagesDo Women Need Feminism? MDI TranscriptniazmhannanNo ratings yet

- Kant's Second Thoughts On RaceDocument21 pagesKant's Second Thoughts On RaceJason DaleyNo ratings yet

- Murabit Ahmad Faal Eulogy2Document8 pagesMurabit Ahmad Faal Eulogy2HelmiHassanNo ratings yet

- Causes of the Jihad of Usman Ɗan FodioDocument42 pagesCauses of the Jihad of Usman Ɗan FodioMuhammad mubaraqNo ratings yet

- Atu - English - BookDocument28 pagesAtu - English - BookAdebayo YemiNo ratings yet

- ,!7IA4B5-ficbig!: Ibn Al-Haytham and Analytical MathematicsDocument465 pages,!7IA4B5-ficbig!: Ibn Al-Haytham and Analytical MathematicsHasanul RizqaNo ratings yet

- A Hundred and One Rules of Arabic GrammarDocument80 pagesA Hundred and One Rules of Arabic Grammarparb33No ratings yet

- Was Al-Harith Bin Kaladah The Source of The Prophet Muhammad's Medical KnowledgeDocument12 pagesWas Al-Harith Bin Kaladah The Source of The Prophet Muhammad's Medical KnowledgeTheIslamPapersNo ratings yet

- Timeline of Muslim Scientists and EngineersDocument22 pagesTimeline of Muslim Scientists and EngineerswaseemqNo ratings yet

- NABULUSI'S COMMENTARY ON IBN AL-FARID'S KhamriyahDocument22 pagesNABULUSI'S COMMENTARY ON IBN AL-FARID'S KhamriyahscholarlypurposeNo ratings yet

- The Light of Sight PDFDocument129 pagesThe Light of Sight PDFMuhammid Zahid Attari100% (1)

- Uthman Dan FodioDocument18 pagesUthman Dan FodiotiflNo ratings yet

- 2 George Saliba - The Development of Astronomy in Medieval IslamicDocument16 pages2 George Saliba - The Development of Astronomy in Medieval IslamicemoizedNo ratings yet

- DR Ghali Translation For The Holy QuranDocument310 pagesDR Ghali Translation For The Holy Quranestacado1100% (1)

- The Muqarnas Dome: Its Origin and MeaningDocument15 pagesThe Muqarnas Dome: Its Origin and MeaningneyzenapoNo ratings yet

- Quranic Manuscripts Epigraphic EvidenceDocument5 pagesQuranic Manuscripts Epigraphic EvidenceadilNo ratings yet

- The Golden Rule in Islam FINALDocument102 pagesThe Golden Rule in Islam FINALAliyah DiponegoroNo ratings yet

- Huzoor Badre MillatDocument5 pagesHuzoor Badre MillatMohammad Junaid SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- Bayaan Al Wujuub Al HijrahDocument350 pagesBayaan Al Wujuub Al HijrahMAliyu2005No ratings yet

- Islam and Science Relation Facets - IqbalDocument37 pagesIslam and Science Relation Facets - Iqbalhaninah az-zahra'No ratings yet

- Ragep 2007 - Copernicus Islamic PredecessorsDocument17 pagesRagep 2007 - Copernicus Islamic PredecessorsAlexandre MazetNo ratings yet

- Kwame Gyekye, The Term Istithna' in Arabic LogicDocument6 pagesKwame Gyekye, The Term Istithna' in Arabic LogicYea YipNo ratings yet

- Ancient Theories of Vision, Light and Color in the Works of Al-KindiDocument30 pagesAncient Theories of Vision, Light and Color in the Works of Al-KindilamiabaNo ratings yet

- Al Ajurumiyyah EnglishDocument64 pagesAl Ajurumiyyah EnglishTanveer HussainNo ratings yet

- The Interaction of Medicine, Philosophy and ReligionDocument289 pagesThe Interaction of Medicine, Philosophy and ReligionFeyzettin EkşiNo ratings yet

- Cultivation of Science by The MuslimsDocument23 pagesCultivation of Science by The MuslimsDynamic Sunni Orthodoxy100% (2)

- Astronomy in Medieval Jerusalem - DAVID A. KING - Islamic AstronomyDocument54 pagesAstronomy in Medieval Jerusalem - DAVID A. KING - Islamic AstronomyyunusNo ratings yet

- Arslan - 2011 - Qur'an's Tajwid in Qutb Al-Din Al-Shirazis Music NotationDocument8 pagesArslan - 2011 - Qur'an's Tajwid in Qutb Al-Din Al-Shirazis Music NotationNicholas RaghebNo ratings yet

- Architects of Scientific Thought in Islamic CivilizationDocument114 pagesArchitects of Scientific Thought in Islamic CivilizationKashmirSpeaks100% (2)

- Nuzūl of The Qur Ān and The Question of Nuzūl Order: Çukurova University, Adana-TurkeyDocument38 pagesNuzūl of The Qur Ān and The Question of Nuzūl Order: Çukurova University, Adana-TurkeyTonny OtnielNo ratings yet

- Land of The OliveDocument22 pagesLand of The OliveSalman Malik100% (1)

- Edward William Lane's Lexicon V7Document277 pagesEdward William Lane's Lexicon V7ELibraryPKNo ratings yet

- Were Islamic Records Precursors To Accounting Book Based On The Italian MethodDocument35 pagesWere Islamic Records Precursors To Accounting Book Based On The Italian MethodIntan MunirahNo ratings yet

- Orientalism in Aeschylus' Persians?Document5 pagesOrientalism in Aeschylus' Persians?Triss GrayNo ratings yet

- Fatimid WritingsignsDocument126 pagesFatimid Writingsignsmusic2850No ratings yet

- Juliane Hammer The Cambridge Companion To American IslamDocument384 pagesJuliane Hammer The Cambridge Companion To American IslamMohmadNo ratings yet

- Al Jallad Pre Print Draft The Religion ADocument112 pagesAl Jallad Pre Print Draft The Religion ARizwan AhmedNo ratings yet

- Science and Islam-HSci 209-SyllabusDocument10 pagesScience and Islam-HSci 209-SyllabusChristopher TaylorNo ratings yet

- Nəsiminin Estetik Fəlsəfəsində Gözəllik VƏ EşqDocument10 pagesNəsiminin Estetik Fəlsəfəsində Gözəllik VƏ EşqAladdin Malikov (Ələddin Məlikov)No ratings yet

- The Distortions of Al-ṢadūqDocument45 pagesThe Distortions of Al-ṢadūqmeltNo ratings yet

- Philosophy and Science in Islamic Golden AgeDocument63 pagesPhilosophy and Science in Islamic Golden AgeMuhammad HareesNo ratings yet

- The Islamic School of Law Evolution, Devolution, and Progress. Edited by Peri Bearman, Rudolph Peters, Frank Vogel - Muhammad Qasim Zaman PDFDocument7 pagesThe Islamic School of Law Evolution, Devolution, and Progress. Edited by Peri Bearman, Rudolph Peters, Frank Vogel - Muhammad Qasim Zaman PDFAhmed Abdul GhaniNo ratings yet

- Preaching Islamic Renewal: Religious Authority and Media in Contemporary EgyptFrom EverandPreaching Islamic Renewal: Religious Authority and Media in Contemporary EgyptNo ratings yet

- Avicenna's Theory of Science: Logic, Metaphysics, EpistemologyFrom EverandAvicenna's Theory of Science: Logic, Metaphysics, EpistemologyNo ratings yet

- Sabra, A. I. - The Appropriation and Subsequent Naturalization of Greek Science in Medieval Islam - A Preliminary StatementDocument21 pagesSabra, A. I. - The Appropriation and Subsequent Naturalization of Greek Science in Medieval Islam - A Preliminary StatementFidel AndreettaNo ratings yet

- Joan Cadden - Science and Rhetoric in The Middle Ages - The Natural Philosophy of William of ConchesDocument25 pagesJoan Cadden - Science and Rhetoric in The Middle Ages - The Natural Philosophy of William of ConchesFidel AndreettaNo ratings yet

- William Newman - Technology and Alchemical Debate in The Late Middle AgesDocument24 pagesWilliam Newman - Technology and Alchemical Debate in The Late Middle AgesFidel AndreettaNo ratings yet

- How Occult Qualities Shaped Scientific RevolutionDocument22 pagesHow Occult Qualities Shaped Scientific RevolutionFidel AndreettaNo ratings yet

- Alexander of Macedonia - The World Conquered (By Robin Lane Fox)Document97 pagesAlexander of Macedonia - The World Conquered (By Robin Lane Fox)Macedonia - The Authentic TruthNo ratings yet

- Inner Sense, Body Sense, Kant's Refutation of IdealismDocument17 pagesInner Sense, Body Sense, Kant's Refutation of IdealismFidel AndreettaNo ratings yet

- M. S. Silk - Heracles and Greek TragedyDocument23 pagesM. S. Silk - Heracles and Greek TragedyFidel AndreettaNo ratings yet

- Chemistry IIDocument13 pagesChemistry IIFidel AndreettaNo ratings yet

- An Article About Khan Bahadur AhsanullahDocument10 pagesAn Article About Khan Bahadur Ahsanullahtaimaabdullahtisha28No ratings yet

- 8604 2aDocument25 pages8604 2aIlyas OrakzaiNo ratings yet

- Indenture of Madrasah Suffatus SahaabahDocument9 pagesIndenture of Madrasah Suffatus SahaabahmusarhadNo ratings yet

- Civilising The "Native", Educating The NationDocument13 pagesCivilising The "Native", Educating The NationaayamNo ratings yet

- How US and Saudi policies fueled radicalization in Pakistani madrasasDocument26 pagesHow US and Saudi policies fueled radicalization in Pakistani madrasassvendwhite100% (1)

- Analysis of Difficulties of PPL FKIP UIR Students in Implementing The Independent CurriculumDocument4 pagesAnalysis of Difficulties of PPL FKIP UIR Students in Implementing The Independent CurriculumInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Madras ADocument50 pagesMadras Ahaussah.brNo ratings yet

- Development of Edu in Pak OutlineDocument2 pagesDevelopment of Edu in Pak OutlineEDU203Z F21No ratings yet

- 6 AqwalDocument594 pages6 AqwalIbrahim BadatNo ratings yet

- Sustainability Concerns of the Madrasah Education Program in the PhilippinesDocument44 pagesSustainability Concerns of the Madrasah Education Program in the PhilippinesRowie DomingoNo ratings yet

- The Uses of Brochures and Pamphlets in Teaching SpeakingDocument24 pagesThe Uses of Brochures and Pamphlets in Teaching SpeakingTirta WahyudiNo ratings yet

- EL 10 Module 4Document15 pagesEL 10 Module 4April Joy YecyecNo ratings yet

- Zahra (S.a.) Academy's Annual Report 2015Document19 pagesZahra (S.a.) Academy's Annual Report 2015busmlahNo ratings yet

- HabiganjDocument28 pagesHabiganjDulalNo ratings yet