Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Content Downloaded From 3.6.73.78 On Fri, 05 Mar 2021 10:27:12 UTC

This Content Downloaded From 3.6.73.78 On Fri, 05 Mar 2021 10:27:12 UTC

Uploaded by

Anusha Rao ThotaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Content Downloaded From 3.6.73.78 On Fri, 05 Mar 2021 10:27:12 UTC

This Content Downloaded From 3.6.73.78 On Fri, 05 Mar 2021 10:27:12 UTC

Uploaded by

Anusha Rao ThotaCopyright:

Available Formats

PRIVATE INTERNATIONAL LAW - JURISDICTION

Author(s): Pippa Rogerson

Source: The Cambridge Law Journal , November 2010, Vol. 69, No. 3 (November 2010),

pp. 452-455

Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of Editorial Committee of the

Cambridge Law Journal

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40962706

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

and Cambridge University Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to The Cambridge Law Journal

This content downloaded from

3.6.73.78 on Fri, 05 Mar 2021 10:27:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

452 The Cambridge Law Journal [20 1 0]

Cromwell J. himself repeatedly emphasised that "the f

undertaking may be implied in the particular circumst

parties' relationship" (at [79]; see also [66], [71], [75] and [7

siderations that inform the implication of terms in this cont

similar to those that are relevant when deciding whethe

a reasonable or legitimate expectation that fiduciary duti

would be complied with. But a lack of substantive differe

the two approaches does not mean that Cromwell J.'s u

criterion is of no use. To the contrary, it usefully focuses a

what the fiduciary has done to justify the expectation

comply with duties of loyalty, thereby giving some structu

dence that ought to be considered when determining whe

pectation of loyalty is appropriate in all the circumstances o

Matthew Conaglen

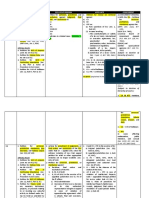

PRIVATE INTERNATIONAL LAW - JURISDICTION

The landscape of Article 5(1) of the Brussels I Regulation conc

the allocation of jurisdiction within the EU has fundame

changed. In a matter relating to a contract the courts of "the

performance of the obligation in question" can take jurisdicti

original wording of Article 5 of the Brussels Convention led

number of cases which sought to identify the obligation in q

and its place of performance. The English courts were parti

adept in locating the obligation in question in England in or

obtain jurisdiction. A more strict rule was subsequently inser

Article 5(l)(b). The first indent gives the courts of the place of de

in a sale of goods contract jurisdiction. In a contract for the p

of services the second indent similarly gives jurisdiction to the c

the place where the services were provided. In Peter Rehder v. Ai

Corporation (Case C-204/08 [2009] E.C.R. 1-6073) the Court of

of the EU emphasized that both indents of Article 5(1 )(b) are

interpreted similarly. Whatever the issue, from non-delivery

payment via breach of warranty and whether the claim is in dam

for a negative declaration, all matters are referred to the courts

place of delivery or provision of services. In Color Drack Gm

Lexx International Vertriebs GmbH (Case C-386/05 [2007]

1-3699) the Court of Justice held that this place is an auton

linking factor providing a close link to the contract. It is referab

ther to national law nor conflict of laws rules. One justification i

those courts are particularly well placed to determine any claim a

out of the contract. Alternatively, the rule is certain and pred

This content downloaded from

3.6.73.78 on Fri, 05 Mar 2021 10:27:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

C.L.J. Case and Comment 453

That attempts to answer the com

courts are not well placed to deal

relating to non-payment, or that

this Article is more complicated th

decision of the Court of Justice illustrate.

First, what if there are several places of delivery or provision of

services? Where these are all in one Member State Color Drack held

that the court at the "place of the principal delivery" determined by

"economic criteria" has sole jurisdiction. There identical goods were

delivered in differing quantities at the same price so the principal de-

livery was merely the one with the largest number of units. Different

facts make it more difficult. Where there is no one principal place, the

CJEU held that the claimant can choose one of the places of delivery in

which to sue for all the claims arising. Previous Brussels Convention

caselaw was different. In Case C-420/97 Leathertex v. Bodetex [1999]

E.C.R. 1-6747 the claimant also had a choice in these circumstances,

but could only sue for the part of the obligation which was performed

in that place. Leathertex lead to a dépeçage of the proceedings, and the

possibility of irreconcilable judgments: neither is appealing. The sol-

ution in Leathertex does not survive for Article 5(1 )(b) contracts

(Rehder, [37]). In Wood Floor Solutions Andreas Doomberger GmbH v.

Silva Trade SA (Case C- 19/09, Judgment of 11 March 2010, not yet

reported) Color Drack and Rehder were developed to cover the case

where the places of delivery or provision of services are in several

Member States. The claimant sought damages for termination of a

commercial agency contract. It had provided the agency services

(negotiating and concluding contracts, communicating with the prin-

cipal and complying with instructions) in a number of states, but its

business activity was largely conducted in Austria. The CJEU ident-

ified the place of provision of services as "the place of the main pro-

vision of services by the agent". This place must be deduced from the

provisions of the contract itself, or if that is not possible, by the actual

performance of the contract. That is a question of fact for the national

court (para. [40]). If it cannot be decided, then the place where the

agent is domiciled is the place of performance.

Secondly, how is the place of delivery or provision of services to be

identified? Where the contract expresses where performance is to be

achieved, that is decisive. In Car Trim GmbH v. Key Safety Systems Sri

(Case C-381/09, Judgment of 25 February 2010, not yet reported) Car

Trim claimed damages from KeySafety for wrongful termination of a

contract under which Car Trim was to manufacture, supply and deliver

airbags to KeySafety's specification. The CJEU held that the place of

delivery can be chosen by the parties because Article 5(1 )(b) provides

"unless otherwise agreed... the place in a Member State where, under the

This content downloaded from

3.6.73.78 on Fri, 05 Mar 2021 10:27:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

454 The Cambridge Law Journal [2010]

contract, the goods were delivered". Linking the two p

does not seem to permit the parties to choose another obl

the contract to locate jurisdiction, such as the place o

Additionally, the previous caselaw did not permit a fi

delivery (Case C-105/95 MSG v. Les Gravières Rhénane

1-911). Nevertheless, what if there is no express place of d

Brussels Convention caselaw referred to the private in

rules of the forum in order to identify the applicable law

whose rules of domestic contract law would fill the gap w

term as to the place of delivery (Case C- 12/76 Tessili v

E.C.R. 1473). The Court of Justice in Car Trim rejected th

noted that the autonomous definition of the place of deliv

after Color Brack precluded an application of the private

law rules of the forum. The place of delivery was to

purely factual criterion", ([52]). In this case where th

carriage of the goods that is where they "were physically

should have been physically transferred to the purchaser

destination", ([60]). This is consistent with a finding in W

factual performance of the contract can be relied on, but

that is consistent with the parties' intentions, ([40]).

Those conclusions do not resolve the problems wher

performance of the delivery obligation. If the contract is

place of delivery or if performance is at the option of one

how is the place of delivery or provision of services to be i

possible that in such a case Article 5(1 )(b) does not ap

right, either Article 5(1 )(a) fills the gap (including the ru

Article 5 is altogether inapplicable: see Besix SA v. Kre

C-256/00 [2002] E.C.R. 1-1699).

Where the contract can be described as having on

obligation, such as a contract to fly a passenger from

another, then neither place is principal (Rehder). The c

ger suing for compensation for a cancelled flight can cho

sue in the place of take-off or of landing. A provider of f

passenger for non-payment can presumably likewise ch

it is doubtful that the passenger defendant would have

sued in those places.

Thirdly, how are contracts classified within Article 5(1)

tract of sale which contains some continuing obligation on

(for example, to maintain the goods sold) fall within Arti

so, into which indent? Or does it fall in Article 5(1 )(a)? C

do not come within Article 5(l)(b) are dealt with by A

(Article 5(l)(c)). These include contracts the performa

takes place outside the EU. Also, contracts which cann

as falling within a particular indent of Article 5(1 )(b) are

This content downloaded from

3.6.73.78 on Fri, 05 Mar 2021 10:27:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

C.L.J. Case and Comment 455

to Article 5(l)(a) following Falco P

E.C.R. 1-3327). There a claim unde

tual property was neither a sale of

Car Trim the CJEU noted that ea

the characteristic obligation of the

or provision of services). Therefore

a contract falls, the court held t

teristic obligation of the contra

include matters of EU and intern

of Directive 1999/44 on the sale

guarantees (O.J. [1999] L 171/12) wh

supply of consumer goods to be c

ferred to Article 3(1) of the Vien

International Sale of Goods and A

Convention on the Limitation Period in the International Sale of

Goods, both of which consider certain contracts ones for the supply of

goods. As neither Convention has been adopted into English law, these

factors are more difficult for an English court to apply. Additionally,

where the purchaser has supplied materials the contract is more likely

to be a contract for the provision of services. Finally, if the seller

bears the responsibility for the quality of the goods then it is more likely

to be one for the sale of goods. These factors only help classify

straightforward contracts. The last factor in particular appears to need

reference to some domestic system of law to determine on whom re-

sponsibility lies. This is inconsistent with its conclusion that the place of

delivery or provision of services is an autonomous concept.

It does not seem from these cases that the insertion of Article 5(1 )(b)

has achieved greater simplicity or clarification.

Pippa Rogerson

KEEPING UP APPEARANCES: THE COURT OF JUSTICE AND THE EFFECTS

OF EU DIRECTIVES

On 19 January 2010, the Court of Justice of the EU delivered its ju

ment in Case C-555/07, Seda Kücükdeveci v. Swedex, (not yet repor

which provides the latest twist in the saga of cases concerning the

effects of EU directives which have not been implemented or have

incorrectly implemented by national law in actions involving p

parties. In Marshall I (Case 152/84, [1986] E.C.R. 723), the Court

lying exclusively on a textual interpretation of the (then) Artic

EC - later Article 249 EC and now Article 288 TFEU- set out the

principle that, given that directives are addressed to Member States,

This content downloaded from

3.6.73.78 on Fri, 05 Mar 2021 10:27:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Causation in Construction Law: The Demise of The Dominant Cause' Test?Document23 pagesCausation in Construction Law: The Demise of The Dominant Cause' Test?StevenNo ratings yet

- Case Digest in Administrative Law and Law On Public OfficersDocument24 pagesCase Digest in Administrative Law and Law On Public OfficersJay Mark EscondeNo ratings yet

- Liquidated DamagesDocument25 pagesLiquidated DamagesFrank Victor MushiNo ratings yet

- Ascertainment of Loss and ExpenseDocument14 pagesAscertainment of Loss and ExpenseHC TanNo ratings yet

- A2014 Keating Causation in LawDocument18 pagesA2014 Keating Causation in LawPameswaraNo ratings yet

- Arbitration in JoinderDocument5 pagesArbitration in JoinderTuputamadreNo ratings yet

- Case Law On NEC3Document7 pagesCase Law On NEC3Dan CooperNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 158.143.233.108 On Thu, 11 Aug 2022 13:42:11 UTCDocument18 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 158.143.233.108 On Thu, 11 Aug 2022 13:42:11 UTCMohasri SanggaranNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 196.249.92.78 On Wed, 29 Mar 2023 17:18:16 UTCDocument5 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 196.249.92.78 On Wed, 29 Mar 2023 17:18:16 UTCAhmed SaidNo ratings yet

- Editorial Committee of The Cambridge Law Journal, Cambridge University Press The Cambridge Law JournalDocument6 pagesEditorial Committee of The Cambridge Law Journal, Cambridge University Press The Cambridge Law JournalAnanthi NarayananNo ratings yet

- Case Law Update: Steven Walker QC Society of Construction Law, 19 November 2020Document18 pagesCase Law Update: Steven Walker QC Society of Construction Law, 19 November 2020Jonathan WallaceNo ratings yet

- Morgan BATTLEFORMSRESTATING 2010Document4 pagesMorgan BATTLEFORMSRESTATING 2010Terence ConradNo ratings yet

- Costain Limited (Claimant) V Tarmac Holdings Limited (Defendant) Case LawDocument7 pagesCostain Limited (Claimant) V Tarmac Holdings Limited (Defendant) Case LawchrisNo ratings yet

- Common Issues Judgment: Skeleton Argument For Permission To AppealDocument52 pagesCommon Issues Judgment: Skeleton Argument For Permission To AppealNick Wallis0% (1)

- Completion' Is The Key To Liquidated Damages: But What Is Completion?Document14 pagesCompletion' Is The Key To Liquidated Damages: But What Is Completion?Ahmed AbdulShafiNo ratings yet

- Concurrent Delay - Law and Regulation in England - CMS Expert GuidesDocument5 pagesConcurrent Delay - Law and Regulation in England - CMS Expert GuidesTerenceTohNo ratings yet

- 233 Skelton Robertson BashforthDocument50 pages233 Skelton Robertson BashforthMichael McDaidNo ratings yet

- Construction Newsletter Issue 20Document8 pagesConstruction Newsletter Issue 20Sanjeev34No ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 14.139.214.181 On Fri, 03 Jul 2020 02:10:08 UTCDocument4 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 14.139.214.181 On Fri, 03 Jul 2020 02:10:08 UTCAyush PandeyNo ratings yet

- MPDF Password RemovedDocument5 pagesMPDF Password RemovedEmadNo ratings yet

- The Law Governing Letters of Credit: V Bank (MarconiDocument26 pagesThe Law Governing Letters of Credit: V Bank (Marconialihossain armanNo ratings yet

- Arbitration - Parol Evidence RuleDocument19 pagesArbitration - Parol Evidence RulezuominNo ratings yet

- Periodic Tenancies. Certainty of Term. RepugnancyDocument5 pagesPeriodic Tenancies. Certainty of Term. Repugnancy李雅文No ratings yet

- Fidic Part 12Document5 pagesFidic Part 12venki_2k2inNo ratings yet

- International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, Local 1228, Afl-Cio v. Wnev-Tv, New England Television Corp., 778 F.2d 46, 1st Cir. (1985)Document6 pagesInternational Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, Local 1228, Afl-Cio v. Wnev-Tv, New England Television Corp., 778 F.2d 46, 1st Cir. (1985)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- MichaelDunn TheJCTStandardBuildingContract05Document14 pagesMichaelDunn TheJCTStandardBuildingContract05Mohammed SyeedNo ratings yet

- 39 Multi Tiered Clauses-Wolrich02Document7 pages39 Multi Tiered Clauses-Wolrich02Ashish VijaywargiNo ratings yet

- Navigant ConcurrentDelays in Contracts Part1Document7 pagesNavigant ConcurrentDelays in Contracts Part1PameswaraNo ratings yet

- Problems of Breach of ContractDocument18 pagesProblems of Breach of Contractlcj0509No ratings yet

- Concurrent Delays, Global Claims and Particulars of Claim: BackgroundDocument3 pagesConcurrent Delays, Global Claims and Particulars of Claim: BackgroundYi JieNo ratings yet

- Battle of FormsDocument4 pagesBattle of FormsRishi SehgalNo ratings yet

- FIDIC Construction Contracts and Arbitration - The Role of Dispute Adjudication Boards and The Importance of Governing Law - Kluwer Arbitration BlogDocument4 pagesFIDIC Construction Contracts and Arbitration - The Role of Dispute Adjudication Boards and The Importance of Governing Law - Kluwer Arbitration BlogpieremicheleNo ratings yet

- The MFN Clause in Investment Arbitration: Treaty Interpretation Off The RailsDocument18 pagesThe MFN Clause in Investment Arbitration: Treaty Interpretation Off The RailsYubraj KhatriNo ratings yet

- Fundamental Breach and The CISG - A Unique Treatment or Failed Experiment? Bruno ZellerDocument12 pagesFundamental Breach and The CISG - A Unique Treatment or Failed Experiment? Bruno ZellerGuillermo C. DurelliNo ratings yet

- Cooke AdministrativeLawNatural 1954Document7 pagesCooke AdministrativeLawNatural 1954ADITI AVINASHNo ratings yet

- Address For Correspondence: Trinity College, Cambridge, CB2 1TQ, UK. Email: Lm324@cam - Ac.ukDocument4 pagesAddress For Correspondence: Trinity College, Cambridge, CB2 1TQ, UK. Email: Lm324@cam - Ac.ukAsadbek IbragimovNo ratings yet

- Local 369, Utility Workers Union of America, Afl-Cio and Utility Workers Union of America Afl-Cio v. Boston Edison Company, 752 F.2d 1, 1st Cir. (1984)Document7 pagesLocal 369, Utility Workers Union of America, Afl-Cio and Utility Workers Union of America Afl-Cio v. Boston Edison Company, 752 F.2d 1, 1st Cir. (1984)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Humphrey Lloyd FinalDocument11 pagesHumphrey Lloyd FinalSandra L HugoNo ratings yet

- John Strauss, as President, or Robert J. Sullivan, as Secretary-Treasurer of Bakery Drivers Union Local 802, International Brotherhood of Teamsters v. Silvercup Bakers, Inc., 353 F.2d 555, 2d Cir. (1965)Document5 pagesJohn Strauss, as President, or Robert J. Sullivan, as Secretary-Treasurer of Bakery Drivers Union Local 802, International Brotherhood of Teamsters v. Silvercup Bakers, Inc., 353 F.2d 555, 2d Cir. (1965)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Would A Common Law Right To Apportion Liability in Contract Facilitate Justice in Concurrent Delay Disputes?Document72 pagesWould A Common Law Right To Apportion Liability in Contract Facilitate Justice in Concurrent Delay Disputes?Ginger WigshopNo ratings yet

- Publications & Events: Construction Contracts: Liquidated Damages Recoverable For Period Prior To TerminationDocument3 pagesPublications & Events: Construction Contracts: Liquidated Damages Recoverable For Period Prior To TerminationRizriyasNo ratings yet

- Onc 2023 05 25Document24 pagesOnc 2023 05 25Work OfficeNo ratings yet

- Camp John Hay Development Corporation v. Charter Chemical and Coating Corporation G.R. No. 198849Document5 pagesCamp John Hay Development Corporation v. Charter Chemical and Coating Corporation G.R. No. 198849Jeanne DumaualNo ratings yet

- Chen Wei A Paper Tiger Credit Hire NewsletterDocument8 pagesChen Wei A Paper Tiger Credit Hire NewsletterHogiwanNo ratings yet

- English Court of Appeal Considers - Practical Completion - For The First Time in Fifty YearsDocument4 pagesEnglish Court of Appeal Considers - Practical Completion - For The First Time in Fifty YearsWork OfficeNo ratings yet

- Digest & Scra - LM Power Engineering Corporation vs. Capitol Industrial Construction Groups, Inc. G.R. No. 141833 March 26, 2003)Document4 pagesDigest & Scra - LM Power Engineering Corporation vs. Capitol Industrial Construction Groups, Inc. G.R. No. 141833 March 26, 2003)Jean UcolNo ratings yet

- Reid Burton Construction, Inc., A Colorado Corporation v. Carpenters District Council of Southern Colorado, 535 F.2d 598, 10th Cir. (1976)Document10 pagesReid Burton Construction, Inc., A Colorado Corporation v. Carpenters District Council of Southern Colorado, 535 F.2d 598, 10th Cir. (1976)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Nova (Jersey) Knit LTD V Kammgarn Spinnerei GMBH, (1977) 2 All Er 463Document7 pagesNova (Jersey) Knit LTD V Kammgarn Spinnerei GMBH, (1977) 2 All Er 463mehalNo ratings yet

- Exclusion EssayDocument3 pagesExclusion Essayq9z9bkn5wzNo ratings yet

- VMoran - HK Causation Presentation Draft FinalDocument26 pagesVMoran - HK Causation Presentation Draft FinalMohamed Talaat ElsheikhNo ratings yet

- Write UpDocument4 pagesWrite Upkavishvyas999No ratings yet

- Charlotte Sothern Railroad OpinionDocument7 pagesCharlotte Sothern Railroad OpinionJustin HinkleyNo ratings yet

- Implied Obligations (Notes) - Aidan Steensma, CMS Cameron McKennaDocument4 pagesImplied Obligations (Notes) - Aidan Steensma, CMS Cameron McKennaAlan WhaleyNo ratings yet

- Dispatch Issue 151Document2 pagesDispatch Issue 151PameswaraNo ratings yet

- Terms - Case LawsDocument9 pagesTerms - Case LawsDivya BharthiNo ratings yet

- Regalian Properties PLC v. London Docklands Development Corporation (199Document6 pagesRegalian Properties PLC v. London Docklands Development Corporation (199Reda HaqNo ratings yet

- Seminário 2 - Good Faith EnglandDocument11 pagesSeminário 2 - Good Faith EnglandNeryNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id3960007Document3 pagesSSRN Id3960007Duyên NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Comments on the SEC's Proposed Rules for Regulation CrowdfundingFrom EverandComments on the SEC's Proposed Rules for Regulation CrowdfundingNo ratings yet

- Military Laws X SemDocument37 pagesMilitary Laws X SemAnusha Rao ThotaNo ratings yet

- Topic: Bareboat and Demise Charter: PartiesDocument17 pagesTopic: Bareboat and Demise Charter: PartiesAnusha Rao ThotaNo ratings yet

- Air and Space Law - 7TH SemDocument24 pagesAir and Space Law - 7TH SemAnusha Rao ThotaNo ratings yet

- Topic: Prospectus and Doctrine Of: Disclosure-Regulations Vs Self Regulations: A Critical StudyDocument18 pagesTopic: Prospectus and Doctrine Of: Disclosure-Regulations Vs Self Regulations: A Critical StudyAnusha Rao ThotaNo ratings yet

- Topic: Drafting of Withdrawal: Application in Criminal CasesDocument17 pagesTopic: Drafting of Withdrawal: Application in Criminal CasesAnusha Rao ThotaNo ratings yet

- Air and Space - 7th SemDocument18 pagesAir and Space - 7th SemAnusha Rao ThotaNo ratings yet

- Topic: Energy Disputes in India: R E L - P S BDocument13 pagesTopic: Energy Disputes in India: R E L - P S BAnusha Rao ThotaNo ratings yet

- Topic: Nidhi Companies: L - D M C.PDocument15 pagesTopic: Nidhi Companies: L - D M C.PAnusha Rao ThotaNo ratings yet

- DPC Edited FinalDocument13 pagesDPC Edited FinalAnusha Rao ThotaNo ratings yet

- Maritime Law - 7TH Sem PDFDocument29 pagesMaritime Law - 7TH Sem PDFAnusha Rao ThotaNo ratings yet

- Adr Reasearch PaperDocument15 pagesAdr Reasearch PaperAnusha Rao ThotaNo ratings yet

- Topic:: Payment of GratituityDocument20 pagesTopic:: Payment of GratituityAnusha Rao ThotaNo ratings yet

- G.R. 119190-Chi Ming Tsoi Vs CA, Gina Lao-TsoiDocument4 pagesG.R. 119190-Chi Ming Tsoi Vs CA, Gina Lao-Tsoiariesha1985No ratings yet

- Philippine Bank Vs GoDocument21 pagesPhilippine Bank Vs GolanderNo ratings yet

- Ambank (M) BHD V Malaysian Coal & Minerals Corp SDN BHDDocument58 pagesAmbank (M) BHD V Malaysian Coal & Minerals Corp SDN BHDpremkumar danapalNo ratings yet

- Romulo v. SamahanDocument7 pagesRomulo v. SamahanBea HidalgoNo ratings yet

- Satilila Charitable Society and Ors Vs Skyline Edud041415COM74061Document10 pagesSatilila Charitable Society and Ors Vs Skyline Edud041415COM74061RATHLOGICNo ratings yet

- 207 in Re LauretaDocument5 pages207 in Re LauretatishyuNo ratings yet

- Benchbook For Trial Court Judges: (Evidence)Document19 pagesBenchbook For Trial Court Judges: (Evidence)jerushabrainerdNo ratings yet

- Aquino vs. Court of Appeals, November 21, 1991Document13 pagesAquino vs. Court of Appeals, November 21, 1991bentley CobyNo ratings yet

- Consti 2 Eminent Domain Case DigestsDocument16 pagesConsti 2 Eminent Domain Case DigestsVanessa VelascoNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 205004 Sps Ernesto Sr. and Gonigonda Ibias v. Benita Perez Macabeo 08.17.16 (Reconstitution of Title)Document4 pagesG.R. No. 205004 Sps Ernesto Sr. and Gonigonda Ibias v. Benita Perez Macabeo 08.17.16 (Reconstitution of Title)Jose Rodel ParacuellesNo ratings yet

- Islamic Da'wah Council of The Philippines v. Court of AppealsDocument3 pagesIslamic Da'wah Council of The Philippines v. Court of AppealsMiko TrinidadNo ratings yet

- ADR - Detailed BriefsDocument24 pagesADR - Detailed BriefsAyush BakshiNo ratings yet

- Module 1 CasesDocument11 pagesModule 1 CasesJennifer OceñaNo ratings yet

- JDR AM No. 04 1 12 SCDocument14 pagesJDR AM No. 04 1 12 SCDyannah Alexa Marie RamachoNo ratings yet

- Sandefur v. Pugh, 10th Cir. (1999)Document4 pagesSandefur v. Pugh, 10th Cir. (1999)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court 2008 4Document27 pagesSupreme Court 2008 4Peaches sparkNo ratings yet

- CRPC - S 211Document24 pagesCRPC - S 211MSSLLB1922 SuryaNo ratings yet

- The Eden Club Rules & RegulationsDocument16 pagesThe Eden Club Rules & RegulationsRodney AtkinsNo ratings yet

- 002 Mijares V Ranada (Dinsay)Document2 pages002 Mijares V Ranada (Dinsay)Julius ManaloNo ratings yet

- Imperial vs. ArmesDocument17 pagesImperial vs. ArmesWorstWitch Tala0% (1)

- Serrano vs. GutierrezDocument9 pagesSerrano vs. GutierrezPearl Regalado MansayonNo ratings yet

- 5 10 13 0204 CR12-2025 Motion For Extension of Time To File Brief and To Strike RJC's ROA and Quasi Transcripts and Exceed Page Limitations A9 - Part5Document95 pages5 10 13 0204 CR12-2025 Motion For Extension of Time To File Brief and To Strike RJC's ROA and Quasi Transcripts and Exceed Page Limitations A9 - Part5ZachCoughlinNo ratings yet

- Jurisdiction of CourtsDocument15 pagesJurisdiction of CourtsLorie Jean UdarbeNo ratings yet

- People V Pagal, G.R No. 241257, September 29, 2020Document37 pagesPeople V Pagal, G.R No. 241257, September 29, 2020Mara ClaraNo ratings yet

- MERALCO v. La Campana Food Products, Inc.Document9 pagesMERALCO v. La Campana Food Products, Inc.AnjNo ratings yet

- Resurreccion V SaysonDocument6 pagesResurreccion V SaysonJohnNo ratings yet

- MDocument129 pagesMPrincess Janine SyNo ratings yet

- Preliminary Considerations Political LawDocument117 pagesPreliminary Considerations Political LawCarmel LouiseNo ratings yet