Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Hollywood Star System

Uploaded by

Gianluca SchettinoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Hollywood Star System

Uploaded by

Gianluca SchettinoCopyright:

Available Formats

The Hollywood Star System and the Regulation of Actors' Labour, 1916-1934

Author(s): Sean P. Holmes

Source: Film History , 2000, Vol. 12, No. 1, Oral History (2000), pp. 97-114

Published by: Indiana University Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3815272

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Indiana University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Film History

This content downloaded from

137.204.24.180 on Sun, 27 Sep 2020 18:05:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Film History, Volume 12, pp. 97-1 14, 2000. Copyright © John Libbey & Company

ISSN: 0892-2160. Printed in Malaysia

The Hollywood star

labour, 1916-1934

Sean P. Holmes

O v er the last fifteen years or so, the field through which the social relations of power in the

of star studies, a sub-discipline of filmfilm industry during the studio era were estab-

studies, has undergone an important lished and maintained.

reorientation. Scholars like Barry King At the purely theoretical level, this body of

and, more recently, Danae Clark have rejected literature works very well, shifting the emphasis of

the overtly textual and psychoanalytical ap-

star studies from the process of consumption to the

proaches to the study of movie stars which char-process of production and sharpening our under-

acterised the scholarship of the 1 970s and early

standing of how the star system has structured la-

1980s, arguing that in focusing attention uponbour-management relations in the motion picture

star images and the spectator-image relationship

industry. What it lacks is any real sense of the star

they render the actor as worker invisible1. Movingsystem in Hollywood as a lived experience. King

beyond the consumption-exchange side of the sets out to 'set the limits of a Marxist account of the

cinematic process, they have tried to relocate star system in the popular cinema'3. Yet his discus-

movie actors in the sphere of production by exam-sion of the nature of performance as a labour proc-

ining the material conditions of labour in Holly-ess and the system of production in which that

wood. King, for example, has looked at stardomprocess takes place rarely moves beyond the level

of ahistorical abstraction and includes little or

as part of an occupation of screen acting, concen-

trating upon what he terms 'the particularities ofnothing on the material conditions of actors' la-

performance as a labour process and the rela- bour at specific historical moments. Clark pro-

tions of production in which such a process oc- fesses to embrace an approach to the study of

curs'2. Rather than situating his analysis at theactors that 'is motivated by a political agenda that

level of the individual star, he has looked at the

operation of the larger 'star system', exploring the

ways in which economic practices in the film in-

Sean Holmes has a Ph.D in American History

dustry have combined with film as a technology to

from New York University. He teaches in the

transform actors' labour into its commodity form. American Studies programme at Brunel Univer-

Clark has attempted to rearticulate the basic sity and is currently working on a book on the

premises of star studies in order to carve out a unionisation of stage actors entitled Weavers of

Dreams, Unite!: Constructing an Occupational

space for actors as 'subjects of production', work-

Identity in the Actors' Equity Association,

ers engaged in an ongoing struggle to control the 1913-1934. Correspondence should be ad-

terms of their commodification. Writing from a dressed to: Dr. Sean P. Holmes, Department of

cultural studies perspective, she has examined the American Studies and History, Brunel University,

processes, both economic and discursive, Uxbridge, Middlesex UB8 3PH, England. e-mail:

Sean.Holmes@brunel.ac.uk

This content downloaded from

137.204.24.180 on Sun, 27 Sep 2020 18:05:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

98 98 Sean P. Sean P. Holmes

Holmes

... privileges

shift, they had gradually embraced a mode of pro- th

jects who duction that rested upon a detailed

histo division of la-

institutionalised relations of dominance under bour and a rigorous application of the principles of

capitalism'4. In her analysis of stardom as a site ofscientific management. At the urging of Taylorite

ideological and discursive struggle, however, theefficiency experts, studio heads had inserted into

men and women who worked in the motion picturethe organisational hierarchy a class of managerial

studios during the 1920s and early 1930s areworkers whose task it was to direct operations on

given no voice and their day-to-day experiences onthe part of capital. By the mid- 1 91 Os, the so-called

the cinematic shop floor are left largely unex-'central producer' system had emerged as the in-

plored. dustry norm. Reflecting broader changes in busi-

Film scholars, no less than the historians that ness practice in the United States, this highly

Clark takes to task in her dissertation for their fail- centralised system of production placed overall re-

ure to interrogate an image of Eddie Cantor that sponsibility for the running of the studio in the

they used on the cover of their study of the Ameri- hands of a general manager or producer. Al-

can film industry, 'should be held accountable for though the director retained control over shooting

the histories they (do not) tell'5. For Clark to claim activities, the producer was the key decision maker

that investigating the historical circumstances of at the operational level, planning and budgeting

screen actors, and especially the thousands of per- films and coordinating the work of the various de-

formers who laboured in relative obscurity, is made partments involved in the manufacturing process

difficult by the absence of adequate primary source in order to ensure regularity of production and

materials is to do her putative subjects an enor- adherence to uniform standards of excellence8.

mous disservice6. Actors at every level of the Holly- Standardisation was not the only economic prac-

wood star system have left vivid accounts of their tice at work in Hollywood, however. In the film

struggles at the point of production. They are not industry, as in other mass-production industries,

to be found, however, in the institutionally oriented individual firms had to differentiate their products

and rather old-fashioned labour histories upon from those of their competitors in order to maxi-

which Clark bases her account of labour-manage- mise their market share, an economic imperative

ment relations in the motion picture studios7. If we that fostered high levels of innovation within the

are to integrate the actor as labourer into the his- parameters determined by the classical stylistic

tory of the film industry in the United States we must standard9. Advertising played a key role both in the

look beyond such sources and seek out the sites in process of standardisation and in the process of

which screen performers, both collectively and as differentiation. On the one hand, it helped to rein-

individuals, have articulated their concerns as force industry-wide benchmarks of quality. On the

workers. This paper, which focuses upon Holly- other, it directed the attention of consumers to the

wood's 'non-union' era and draws heavily upon unique qualities of a given product- its authentic-

hitherto unused materials in the Actors' Equity As- ity, its 'realism', its cost, its technical excellence,

sociation Collection at the Wagner LaborArchives and, above all, its stars0.

in New York and the Academy Collection at the The star system was central to the economics

Margaret Herrick Library in Los Angeles, is con- of moviemaking in the United States during the

ceived as a first step in that process. studio era. Its adoption in Hollywood had not been

By the late 1910s, the movie industry in the a straightforward process, though. To the apostles

United States was operating on a mass-production of scientific management, the institution of star-

basis. Eager to maximise profits, filmmakers had dom was an outmoded relic of the legitimate thea-

seized upon the concept of standardisation as the tre, a pre-industrial anomaly in a system of

key to industrial efficiency. As early as 1906, they production that was increasingly geared towards

had begun to concentrate their energies upon the maximising efficiency and minimising unnecessary

production of fictional narratives chiefly because expenditure and they had continued to rail against

they could be made at a predictable cost and re- it even after it had emerged as a key weapon in the

leased on a regular schedule. In the wake of this struggle for market dominance. When efficiency

This content downloaded from

137.204.24.180 on Sun, 27 Sep 2020 18:05:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Hollywood star system and the regulation of actors' labour 99

experts audited Vitagraph in 1917, for example, work and the grim realities of its factory condi-

they were highly critical of the company for paying tions'14.

what they saw as excessive salaries to its leading At the base of the occupational hierarchy that

performers. In their report, they claimed that 'the underpinned the operation of the Hollywood star

tendency in the business is towards making the play system during the studio era were the unknown

and not the actor the attraction' and advised man- actors and actresses competing for work as extras

agement to encourage this trend, insisting that 'the and bit players. Inspired by a discourse of stardom

cost of good plays by popular writers is much less which identified 'personality' and a natural affinity

than the cost of salaries to advertised 'stars"'1. with the camera as the keys to screen success,

Contrary to such predictions, however, efforts to thousands of would-be motion picture performers

sell individual movies on the strength of an engag- made their way to Hollywood in the 1910s and

ing storyline and a good script proved unsuccessful 1920s, the majority with no acting experience

and by the late 1 91 Os, actors had become not onlywhatsoever. By film historian Kevin Brownlow's es-

the most important means of differentiating onetimate, their chances of finding jobs in the studios

film from another but also the key to attractingwere no better than one in a hundred15. As many

outside capital12. Through their unique personae, were to find to their cost, even a promise of paid

star performers invested movies with an element ofemployment could not always be taken at face

distinctiveness that gave their employers a com- value. Throughout the 1 920s and 1 930s, it was

petitive edge in the cinematic marketplace and common for performers to receive informal job

thereby justified the vast salaries that they were offers from studio representatives only for them to

able to commandl3. be withdrawn at a later date. Often this was simply

The star system was more than simply a means the consequence of a directorial whim. In 1934,

of marketing motion pictures, however. It was also for instance, dancers Don El Mere and Dorothy El

the basis for a hierarchical division of labour in the Mere gave up a secure job in Lake Tahoe on the

Hollywood film industry that shaped the working strength of a promise of work in a musical from

lives of all motion picture performers, regardless of Dave Gould, a choreographer at RKO. When they

their individual status. Straddling the contradictiondemonstrated their talents for the film's director

between standardisation and differentiation, it al- Mark Sandrich, however, he decided that they

lowed film companies to reconcile the competingwere not what he was looking for and they found

imperatives of economy and originality. Under its themselves stranded in Los Angeles without any

aegis, they could pay high salaries to the privileged means of supporting themselves16. On otherocca-

elite in Hollywood whilst simultaneously control-sions, it happened because the star around whom

ling costs by placing strict limits on the earnings of a cast was being built had become incapacitated.

the character actors, supporting players, and ex- In early 1 932, for example, Ralph Ince accepted a

tras who occupied the lower strata of the occupa-verbal offer from the RKO casting department of a

tional hierarchy. Just as importantly, though, the small part in a John Barrymore vehicle. Owing to

star system worked to reinforce managerial controlan injury to Barrymore, however, the studio put the

over the production process and made it easier for production on hold and eventually told Ince that

studio heads to dictate the terms of actors' com- his services were no longer required17. Nor was a

modification. By elevating a small minority of per-written contract necessarily a guarantee of paid

formers at the expense of the struggling majority, itemployment. In 1932, actress Zena Bear signed

fragmented the acting community and forestalled up with the Radio Transcription Company, a small

the emergence of a sense of shared oppression studio operating on the margins of the industry, to

amongst the men and women of the silver screen. play a role in a series of twenty-six shorts provision-

By prioritising the image over the image-making ally entitled Our Neighbors at a salary of $10 a

process, moreover, it stripped actors of their iden- film. When the studio subsequently decided not to

tity as workers and, as Danae Clark puts it, '[di- put the series into production it cancelled Bear's

verted] public attention away from the problem of contract and refused to pay her anything'8.

This content downloaded from

137.204.24.180 on Sun, 27 Sep 2020 18:05:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

100100 Sean P. Sean P. Holmes

Holmes

Fig. 1. Extras

benefit which

Even I had

when n

the

the men

toand

getw

wood lunchb

acting co

their kind

labours. o

Griffith's

erty,Intt

ceived $1.25,

he'd si

lunch inwhat

returnw

tions ofI Griff

stroll

abery sides

demons of

was

significance his

fo

line his

that lunc

far o

cially if they h

Thoug

When 1920s,

the tru

for it, yellin

remaine

couldn't con

workin

lunchesinto

and th

th

happy encount

with th

This content downloaded from

137.204.24.180 on Sun, 27 Sep 2020 18:05:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Hollywood star system and the regulation of actors' labour 101

ford to eat regular meals. In an article recounting of pay and he responded angrily, accusing his em-

her experiences, she described what had hap- ployers of resorting to subterfuge to cut their wage

pened when a male actor walked into the casting bills23. On the face of it, the distinctions between

office where she was waiting with other screen as- one type of work and another were small and so

pirants and offered round a handful of mints. 'I had too were the differences in the rates of pay that

noticed a gaunt woman next to me', she recalled. attached to them. But for performers struggling to

find regular employment they were enormously im-

Now she rushed forward and clutched at the

portant.

man's hands, grabbing the little packages.

Cost-conscious producers also resorted to

'No you don't', he cried. 'Give those back.

paring down minor roles after shooting had started

You can only have one'. She paid no attention

in order to cut their wage bills. During the filming

to him. She was already stuffing those little

of MGM's prison melodrama The Big House in

candies into her mouth. To her, plainly, they

1930, for example, actor Matthew Betz took part

were food20.

in a scene in which he overheard a conversation

Statistics relating to standards of health within which the script required him to repeat to another

the acting community in Hollywood in the 1910s character in a later scene. To his dismay, the studio

and 1 920s do not exist. Impressionistic evidence, subsequently closed the film and terminated his

however, lends support to Joseph Henabery's engagement without shooting the scene in which

claim that malnutrition and other related diseases he repeated the conversation, claiming that it was

were not uncommon21. not necessary as the repeated conversation was

Members of a perennially overcrowded pro- not a vital part of the story24. As long as it did not

fession, the unknown performers who scraped out compromise continuity within the narrative, the

a living in cinematic obscurity had little alternative omission of a small scene of this type had little or

but to accept work on whatever terms it was offered no effect upon how a film turned out. To the per-

to them. Secure in this knowledge, studio person- formerwhose lines had been cut, however, it could

nel devised a range of tactics to keep their labour be the source of considerable resentment. On the

costs to a minimum. Producers often signed up one hand, it meant a shortened engagement and,

performers at an extra's rate of pay but expected therefore, a loss of wages. On the other, it meant

them to do more than an extra's work. In 1 933, for less time on screen, a key consideration for actors

example, the William Fox Company engaged a and actresses who had their sights set upon profes-

performer named General Savitsky as a so-called sional advancement.

'atmosphere player' on one of its productions at a Like many other groups of workers in industrial

salary of $10 a day. When filming began, the di- America, the men and women who plied theirtrade

rector ordered Savitsky to play the role of 'a police- in the motion picture studios encountered a work-

man speaking French' but refused to pay him the ing environment that was fraught with dangers. Bit

$25 a day he was accustomed to receiving for roles players and extras, performers whose collective

which required him to deliver lines22. In another welfare was not a major priority for the studio

incident involving the William Fox Company, actor heads, frequently fell victim to what might, in other

Jack Kenny accepted a position as a 'bit and fight' lines of work, have been defined as industrial acci-

player for a series of scenes in a production of The dents. During the shooting of a scene in a Pathe

Oregon Trail which were to be shot on location in Studios production in 1930, for example, actress

Arizona at a salary of $90 a week. As soon as Florence Oberle received severe bites to the face

shooting was completed, the producer asked from a dog that her role had required her to carry

Kenny if he would like to continue working on the around in her arms. She later reported that as a

film as an extra in the company's Los Angeles stu- consequence of her injuries she was 'out of com-

dio at the reduced rate of $60 a week, an offerthat mission for work for some time [and] spent ten days

he accepted without hesitation. When he began under the care of a doctor'25. On another occa-

working, however, he discovered that he was ex- sion, bit player Rose Plumer lost two teeth when she

pected to do a bit player's work at an extra's rate was struck in the face with a club by a fellow per-

This content downloaded from

137.204.24.180 on Sun, 27 Sep 2020 18:05:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

102102 Sean P. Holmes Sean P. Holmes

highly

former durin

1933 productried t

were hope

hardly o

l

tended they to pr c

marketable comeb c

tablished directo star

actress who had been cast in the role of a home-

gagement be

caused steader, to unbutton

by her dress and, in her words,

'g

wreck 'to immodestly

careerexpose her breast'. When she re-

female fused to do soperfo

an argument ensued which culmi-

findingnated in her being ordered wor off the set29. A

the studio,

performer's sexuality could enter into the process t

the of exchange in other ways as well. Aspiring ac-

industry

As tresses were sometimes faced with a choice

Danae be-

Cl

screen actors

tween trading sexual favours for paid employment

or not working at all. In early

1930, for instance, Isabel

Cotton, a young singer who

had already appeared in

several early screen musi-

cals, successfully auditioned

for a part in an MGM pro-

duction provisionally entitled

Silk and Cotton. When she

arrived at the lot to begin

shooting she was greeted by

a studio executive who said

that he wished to speak to

her privately. 'He led the way

along a building being dis-

mantled and to a rehearsal

room in the rear and there

made it clear that he ex-

pected me to accept his ad-

vances then and there', she

claimed later. 'I was so

shocked and amazed at his

insulting behaviour that I did

not know what to do ...', she

went on. 'I was not desirous

of making a scene and left

after expressing my indigna-

tion.' Several weeks later the

studio executive telephoned

her and asked herto visit him

at his office. Still anxious to

Fig. 2. 'I am entirely content to live out here in Hollywood in this

profusion of beauty', wrote transplanted New York stage actor Louis secure a job, she agreed to

Wolheim (left), seen here with Lew Ayres in All Quiet on the Westerndo so but no sooner had she

Front (Universal, 1930). arrived in his office than he

This content downloaded from

137.204.24.180 on Sun, 27 Sep 2020 18:05:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Hollywood star system and the regulation of actors' labour 103

renewed his advances. 'He immediately threw his the primitive as to require radical adjustment

arms around me and again implored me to do as to fit into it32.

he wished', she reported.

Even for performers who were employed on a

I was thus placed in an awful embarrassing regular basis at good rates of pay, however, the

predicament: dependent on my own efforts to Hollywood 'dream factories' were a far from per-

make a living, not wishing to lose the oppor- fect working environment.

tunity of singing at a studio I was at a loss how Amongst the men and women who occupied

to handle the situation. His insistence was very the broad middle strata of the Hollywood acting

distressing and during this time several people community, there was considerable resentment of

came back [to the office] and he would have the way in which the star system prioritised the in-

to step out to the waiting room to dismiss terests of a privileged elite. One-time stage actor

them. Wedgewood Nowell, for example, was highly criti-

cal of the practice of setting salaries in relation to

Eventually Cotton's harasser relented and al-

box-office drawing power and allowing a small

lowed her to leave his office, assuring her that he

minority of actors and actresses to monopolise the

still wanted herto work forthe studio. However, she

most lucrative work, insisting that it rested upon an

received no further job offers from him and sub-

entirely false set of assumptions. 'What the public

sequently heard that he had fired another woman

desires primarily is entertainment [emphasis in the

on the MGM payroll for letting her know that he

original]', he asserted in a letter to the Actors'

was sending out calls for replacement singers30.

Equity Association, the New York-based stage ac-

Not all the actors and actresses who earned

tors' union, in 1 924. 'If the show is good, the public

their living in the movie industry experienced such

don't care much who is in it.' Adding to Nowell's

overtly exploitative employment practices. Though

sense of injustice was his conviction, seemingly

the system of production in Hollywood tended to

shared by many of his fellow performers, that the

prioritise the ability to cultivate a marketable per-

motion picture studios were colluding to limit the

sona over more traditional skills, studios relied

salaries of middle-ranking performers who were

heavily upon performers who, by virtue of their

not tied in to long-term contracts. 'It is reasonably

acting talent ortheir ability to conform to a physical

certain' he claimed, 'that a salary list" is being kept

type, could slip easily into supporting parts and

on file [by the producers] with a view to preventing

character roles. Often employed on a freelance

actors from raising their salaries between pictures

basis rather than under contract to a single studio,

when freelancing'33. Like the less successful per-

the most successful supporting players were well

formers labouring at the base of the occupational

compensated for their labour and, though their

hierarchy, Hollywood's supporting players and

salaries never matched the sums paid to the Holly-

character actors frequently fell victim to cost-cut-

wood elite, their working lives were potentially

ting initiatives at the point of production. During

much longer than those of the stars31. Assured of a

the early 1 920s, for example, cost-conscious stu-

steady flow of screen roles, they enjoyed a stand-

dio managers tried to trim their wage bills by intro-

ard of living that far outstripped that of their coun-

ducing 'rotation shooting', a practice which

terparts in other branches of the performing arts. 'I

Wedgewood Nowell described as follows:

am entirely content to live out here in Hollywood in

this profusion of beauty where we work and play, Here's the way it works. The various 'sets' in

eat and play, sleep and play', wrote character ac- the picture are erected in such order as to

tor Louis Wolheim in a 1 926 article explaining why permit the studio to absolutely 'clean up' all

he preferred the movies to the stage. scenes with a given actor or actress who re-

ceives, say, $2,900 weekly. This player is 'rail-

It's so beautiful that the very air breathes roaded' right through those sets which are

warmth and love. The sunshine and flowers, ready and waiting - and as night is turned into

the slow tempo of life is nearer to the natural day and the player simply rushed from one set

state, and none of us is so far removed from to another from eight-thirty or nine a.m. until

This content downloaded from

137.204.24.180 on Sun, 27 Sep 2020 18:05:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

104104 Sean P. Sean P. Holmes

Holmes

eight, scene or to shoot additional scenes which were

nine, or not

player a part

willof the original script. On occasion, studios

stan

took advantage of such clauses to cut performers

Now then - her

from the pay roll temporarily without dispensing

into it. Just as

with their services. Towards the end of shooting on

with the $2,900

a Fox production in 1 931, for example, studio ex-

they start the n

ecutives told George Andre Beranger, a support-

have scenes tog

ing player earning $750 a week, that his services

played by the fir

were no longer required but warned him not to

the second play

shave off the beard he had grown forthe part. Four

'railroaded' do

days later they called Beranger back to shoot what

first one was. T

they claimed was an 'added scene', offering him

Now sometimes

an additional day's salary but refusing to pay him

that it is

for the period imp

after they had ended his original

engagement even

services in though they had known full well

just

the picture an

that they would need him again35. Willy Fung, an

Asian-American actor who had

scheduled to taken advantagela

player of the limited opportunities available to non-white

instead o

salary)performers

is during the early 1 930s to carve out a

told t

ture' and that

niche for himself playing waiters, cooks, and ship's

added scenes

stewards, experienced a variation on this ployor at

the the hands of MGM. In 1934, the

studio studio demanded

will

three that he return for retakes of Sequoia, a film

days, orhe had

worked on almost a year

gleefully earlier, at his original

receiv

port salary of $300 a week,

the nexteven though the standard d

truth fee for his services

of thehad increased during thema

interim

them to $350 a week36.laying

by

point According to Wedgewood Nowell, unscrupu-

where th

ture34 lous producers were not above using flattery to

dupe unwary performers into playing two parts for

Conceived as a practical application of the

the price of one. 'An actor engaged in a good part

principles of the assembly line to the process of

for ONE [sic] picture', he explained,

making motion pictures, 'rotation shooting'

aroused considerable anger among freelancers is approached and told that some other direc-

like Nowell who figured out that it worked entirely tor on the same lot is stuck for a 'good' actor

to the advantage of their employers. Not only did to play such and such a part in his picture. The

it increase the length of their working day while part isn't very long but it needs a GOOD MAN

reducing the total number of days they worked. It [sic] .... Now as he isn't being used tomorrow

also placed them at the studio's disposal without by the director, he is supposed to be working

requiring the studio to employ them continuously forwhen he was originally engaged 'would he

for the duration of a shoot. mind' shipping over to so-and-so set tomor-

The issue of retakes and added scenes re- row and play that part. ... Thus, they get a

mained a perennial source of tension between ac- good man in two pictures for one salary37.

tors and their employers throughout the 1 920s and

Where flattery failed, studio representatives

early 1930s. Most freelance contracts contained

sometimes resorted to outright coercion. In 1932,

clauses which bound performers to make them-

for example, the William Fox Company hired Stan-

selves available after their initial engagement had

ley Fields, a middle-ranking actor who worked

ended if the producer of the movie on which they

regularly throughout the 1930s as a screen

had been working wanted to retake a particular

'heavy', on a fixed weekly salary to play supporting

This content downloaded from

137.204.24.180 on Sun, 27 Sep 2020 18:05:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Hollywood star system and the regulation of actors' labour 105

Fig. 3. Lois Wilson (right, with Alan Hale), felt that the 'uncomfortable and ... unexpected'

production circumstances of The Covered Wagon (Paramount, 1923) improved the quality of the

film.

roles in two films which were scheduled to be made sum which together with the same share of the

one after the other. When shooting overran on the profits that she had enjoyed at Famous Players-

first film, the studio tried to force Fields to begin Lasky gave her a net income in excess of $1 million

working on the second for no extra salary, an ar- a year. Pickford was exceptional in that her per-

rangement that the actor, not surprisingly, found ceived exchange value allowed her to negotiate

totally unacceptable38. unusually lucrative percentage deals. Stars who

For the relatively small number of performers were employed on a straight salary, however, were

who won a place in the cinematic firmament, con- also very highly paid. In 1923, for example, Fa-

ditions of employment were, on the face of it at mous Players-Lasky had seven performers under

least, far from onerous. Signed up to long-term contract who were earning in excess of $250,000

contracts, the stars of the silver screen were extra- a year. Norma Talmadge topped the list with a

ordinarily well rewarded for their labour. As early weekly salary of $1 0,00039.

as 1916, Mary Pickford was receiving $1 0,000 a By comparison with the vast majority of actors

week from Famous Players-Lasky plus 50 per cent and actresses in the United States, the elite of the

of the profits on the ten films she made each year. Hollywood acting community enjoyed a very cos-

In 1918, she moved to First National in return for seted professional existence. On occasion,

an annual salary of $675,000 for three films, a though, even they had to labour under very harsh

This content downloaded from

137.204.24.180 on Sun, 27 Sep 2020 18:05:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

106106 Sean P. Sean P. Holmes

Holmes

conditions, part

majority

cation. In a

only 196

lim

Lois has

Wilson obse

reca

having produce

to live

suppliesply

rannot

ou

ered With

Wagon, un

a

which she co-st

dustry l

When such

Colleena Mw

the Highworkers

Sierra

housedtions

in a u

ca

running1 water

91 Os,a

for in the

heating. 'ItU

1962. world m

'Every o

in and sively

build a in

f

water on it. sim

'You W

cold. We had

truth to

ab

so it would

the unfr

fanz

to find ception

themsel

1923, whilst sho

through

Flash the Won

Rome. Y

northern

whoIdaho

com

rector ment or

husband

the rest their

of thesc

c

ing. Vanterised

Tuyle h

to drag sional

him id

on

miles across a

operatio

safety experien

but Shipm

husband had

strates, t

tated42. ployers

Such in

and left stacked

no lastin

of Goudal

performers

pursuitwhen

of sh

wha

mount

excellence' thanP

'Oh we early

were sc

co

ence oftale, Pa

workin

don't that the

think rep

hadn't been unc

perform

'They

unexpected w

circ

tured t

Nevertheless,

stars said

and that

the m

means free of

displease

wood into

was my

punct

lic had

power ser

strugg

star identity

performer

control discover

over th

Barry tle

King weigh

has a

dom ever

allows wr

the

out a 'manoeuv

early 1

ship when

with theI o

s

This content downloaded from

137.204.24.180 on Sun, 27 Sep 2020 18:05:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Hollywood star system and the regulation of actors' labour 107

was a swell stunt and would be continued, no mat- To her evident frustration, however, she was

ter what my feelings on the subject might be.'48. In unable to cast off the Goudal persona and reinvent

the context of the system of production that pre- herself as a dedicated cultural worker with legiti-

vailed in Hollywood in the 1920s, Paramount's mate concerns about how she was represented on

reluctance to give ground on this issue was entirely the screen. In the eyes of most commentators, she

understandable. As Goudal was to discover to her was nothing more than a pampered prima donna

cost, her persona was more than simply a market- whose career was on the skids because, to quote

able commodity. It was also an instrument of con- one article, 'her highly Latin soul refused to bend

trol, a weapon that managers and producers at before either directors or producers'53. When Cecil

Paramount and elsewhere could use against herto B. De Mille terminated her contract with three years

reinforce their authority at the point of production still to run on it, asserting that he could not work

and beyond. with an actress whom he characterised as 'a little

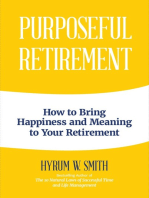

In 1925, after a brief spell with the Distinctive cocktail of temperament', his actions went entirely

Pictures Corporation, Goudal signed a five-year unchallenged in the newspapers54.

contract with the newly created Cecil B. De Mille Goudal had not yet exhausted all her options,

Pictures Corporation. Increasingly unhappy with however. In an effort to resurrect her professional

the terms of her commodification, she soon began reputation, she took out a lawsuit against De Mille,

to demand a greater degree of control over the demanding compensation of $101,000 from her

production of her image. Within a matter of erstwhile employer on the grounds of breach of

months, her relationship with her new employers contract55. The ensuing court case was very acri-

had broken down irrevocably. Newspapers were monious and did nothing to enhance her value in

quick to reproduce the ensuing power struggle as the cinematic employment market. In February

an extra-filmic narrative for the consumption of a 1929, three Hollywood directors testified on be-

moviegoing public that was as interested in the half of De Mille, claiming that Goudal's 'artistic

details of the off-screen lives of the stars as it was temperament' together with her 'insubordination

in their appearances on screen49. According to and willfulness' made her impossible to work

one contemporary report, the problem stemmed with56. Even in the witness stand, Goudal was un-

from Goudal's insistence upon a minimum able to divorce herself from her persona. Her ef-

number of close-ups in each of her movies50. Ac- forts to justify her position to the court were

cording to another, its origins lay in Goudal's re- represented in the press as the emotional outpour-

fusal to allow a cameraman to photograph her ings of 'a temperamental and artistic actress

from her left side 'because she thought that par- caught between picture directors and producers

ticular camera angle did not do her profile jus- who had their own ideas about how she should do

tice'5 . Unwilling to allow her employers to dictate her work'57. In the end, the court ruled in favour of

the parameters of the debate over her professional Goudal upon the grounds that that she had a legal

conduct, Goudal tried to put her case to the press. right to 'so-called fits of temperament' and or-

'Miss Goudal is frank in admitting her disagree- dered De Mille to pay damages of $31,00058.

ments and is willing to talk of them', reported one Goudal's victory was a hollow one, though. Ac-

Oklahoma City newspaper in 1925. cording to press reports, the studios responded by

placing heron an unofficial blacklistand she found

She maintains that she knows something it impossible to find work.

about pictures and is entitled to some say in A little over a year later, MGM relented and

the direction of her own. She bases her right offered Goudal a featured part in one of its early

upon the fact that a poor picture hurts her French language releases at the much-reduced

standing more than it hurts anyone else con- salary of $1000 a week. Eager to relaunch her

nected with it. Therefore, she states, she re- career, Goudal accepted the offer but refused to

fuses to do anything in any scene which she cash her salary checks. 'I was willing to do it for

feels is not good52. nothing but could not jeopardize my position and

career by doing it for the salary offered', she ex-

This content downloaded from

137.204.24.180 on Sun, 27 Sep 2020 18:05:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

108 Sean P. Holmes

plained later. 'I did not want anyone to say She did

the constraints of the identity that the studios had

it for MGM for $1 000 so she can do it for us"'59.

imposed upon her, she turned hertalents to interior

design and disappeared into obscurity62.

Her comeback ended prematurely, however, when

her new employers allegedly reneged on a promiseThough actors at every level of the star system

had ample reason to resent the conditions under

to give her star billing when the film was exhibited

at MGM's Madeleine Theatre in Paris60. Exhausted

which they laboured, the obstacles to collective

by her ordeal at the hands of her various employ-

action in Hollywood were formidable. The star sys-

ers, Goudal suffered a nervous breakdown tem

(evi-divided the acting community both hierarchi-

dence, for those who sought it, that she was indeed

cally and by type, a process of fragmentation that

placed barriers between actors and, in Danae

psychologically unstable) and was unable to actfor

several months61. She returned to the screen in Clark's words, 'gave studio heads the power to

1931 in Business and Pleasure, a Will Rogers bind [them] into a passive community of work-

vehicle, playing a role that parodied her earlier ers'63. Among the stars, few were willing to jeop-

screen incarnation as a femme fatale but her ca- ardise their privileged position by challenging

reer as a star was effectively over. Unable to escape exploitative labour practices. Among the lesser

players, most were more

than happy to trade coop-

eration in the workplace for

regular employment and a

shot at the big time. For

their part, the studio heads

2222V'.ft ::0- . .5and, just as importantly,

:I i i their representatives on the

cinematic shop floor, felt a

deep-rooted antipathy to-

wards organised labour

: and they worked tirelessly

to prevent the trade union

movement from estab-

lishing a foothold in Holly-

wood. As Joseph

_.. Henabery's account of how

he dealt with a group of ex-

tras who belonged to the

Industrial Workers of the

World (IWW) during the

shooting of Intolerance

::. Ni0 demonstrates, they we

notabove using violence or

:1:::~ : the threat of violence to

force those whom they

wl^1f ^ identified as troublemak

into line.

i 1^eWe were shooting th

%sc ^crucifixion and we

waited to do it at dusk

actress Jetta when we didn't have

Fig. 4. Typed as exotic and temperamental, French

Goudal fought the Hollywood studios and found herself on an s , strong sunlight, and

unofficial blacklist.

This content downloaded from

137.204.24.180 on Sun, 27 Sep 2020 18:05:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Hollywood star system and the regulation of actors' labour 109

could get certain effects with lights and flares. of each of the five groups involved in the creative

These guys started to insist on another day's process and entrusted with the task of promoting

pay if they were going to stay on. ... The ha- harmonious employment relations in the film in-

ranguing wenton forquite a time. Finally I told dustry66.

them they would get seventy-five cents - take Almost as soon as the Academy was in place,

it or leave it. the studio heads set about testing its efficacy. In

June 1 927, sixteen of Hollywood's biggest studios

'We leave it.'

implemented pay cuts of ten percentforall workers

They started up the hill to the gate, which earning over fifty dollars a week in what they

would be two hundred yards away through claimed was an attempt to reduce excessive pro-

sets. I beat them to it. I ran around another duction costs. Incensed at what they interpreted as

way, and as I went past a carpenter I saw that high-handedness on the part of their employers,

he had a hammer in his overalls. I grabbed it workers at every level of the studio system - direc-

and got to the gate just before the Wobblies. tors, writers and technicians, as well as actors -

turned to the Actors' Equity Association for leader-

There was a box there. I climbed on it and

ship. For a brief moment, it seemed that the film

yelled; 'The first son of a bitch who tries to get

bosses had finally turned the keys of the motion

out of this gate is going to get a hammer right

picture studios over to the stage actors' union67.

in the head'.

However, the Academy, having been presented

You've always got ringleaders you watch for.with an opportunity to prove its worth to the film-

That's how you lick these mobs64. making community, acted promptly to defuse the

situation. Ten days after the new pay scales were

By the mid-1 920s, however, union bashing inannounced, members of its executive board

a literal sense was the exception rather than thepassed a resolution sympathising with the studio

rule and employers in the film industry had begunheads in their desire to reduce costs but condemn-

to experiment with other, less overtly confronta- ing the blanket reduction in salaries and suggest-

tional, methods of defusing the threat which or-ing an alternative strategy based around the twin

ganised labour posed to their collective interests. ideals of harmony and co-operation. 'We feel',

In November 1 926, the International Alliance they concluded,

of Theatrical Stage Employees and Motion Picture

that by the concentrated efforts of all the mem-

Machine Operators (IATSE), an AFL affiliate with

bers of all the branches of the industry, ways

jurisdiction over the studio craft workers, used the

and means can be devised of effecting re-

threat of a walkout to persuade the major produc-

forms in production which will result in great

ers to recognise its right to bargain collectively on

economies, as a result of which it may be un-

behalf of its members65. With the industry's open

necessary to impose any uniform reduction68.

shop on the verge of collapse, the studio heads,

who had already pooled their collective resources Responding with an alacrity that suggests that

in the Motion Picture Producers Association, Inc.,the entire controversy had been engineered in or-

moved quickly to ensure that the 'talent' in Holly-der to demonstrate that trade unions had nothing

wood did not cast its lot with organised labour.to offer Hollywood's cultural workers, the studio

Within weeks of the signing of the so-called Studioheads agreed first to postpone the proposed salary

Basic Agreement, they opened talks with groups ofreductions and eventually to scrap them alto-

actors, screenwriters, directors and techniciansgether69. A few months later, they sat down with

with a view to devising a mechanism for resolvingrepresentatives of the Academy and thrashed out

disagreements between management and labourthe terms of a contract for freelance players which

without the interference of outside agencies. Thethey promised would standardise conditions of

negotiations bore fruit in early 1927 with the employment across the industry and eradicate any

founding of the Academy of Motion Picture Artsabuses that had crept into the relationship between

and Sciences, a body made up of representativesactors and their employers70.

This content downloaded from

137.204.24.180 on Sun, 27 Sep 2020 18:05:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

110110 Sean P. Sean P. Holmes

Holmes

Fig. 5. Actor C

one of the foun

founders were

[Marc Wanama

Like other em

less interest in improving working conditions than

duringin keeping

the the Actors' Equity Association,

1a union9

controlled by the old theatrical elite, out of the

anti-unionism7

studios73.

dividuals who

To be sure, the Academy

standing in did provide actors

or

production bra

and other groups of cultural workers in Hollywood

try, with a measure of protection against

either the worst ex-

indir

set of cesses of the studio heads and their repre-

criteria r

community

sentatives. All performers, regardless of whetherin

or

most successful

not they were Academy members, were entitled to

permanent we

use the services of the Academy Conciliation Com-

whom the studios defined as 'creative artists' - mittee, a body made up of one representative from

directors, cinematographers and screenwriters, aseach branch of the Academy and entrusted with the

well as actors - and the studio craft workers who task of resolving disputes between labour and

had cast their lot with organised labour. Encour-management. During the period between January

aged to think of themselves as equal partners in the 1928 and July 1929, the Conciliation Committee

productive process, the stars who became the offi- handled somewhere in the region of 111 com-

cial voice of the screen acting community showedplaints from actors, the vast majority relating to

This content downloaded from

137.204.24.180 on Sun, 27 Sep 2020 18:05:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Hollywood star system and the regulation of actors' labour 111

contractual issues. In about one hundred of the the scandals in the press, whereas one of the

cases that came to its attention, the Committee main purposes of the Academy is to reduce the

managed to mediate between actor and studio harmful publicity about such problems within

without putting its formal arbitration procedures the industry76.

into operation. In a further eleven cases, it held

hearings at which both parties were able to put Though the Academy's arbitration and con-

their case and in all eleven it found in favour of the ciliation service undoubtedly gave individual per-

actor74. Nor did the Committee's involvement in a formers the opportunity to let off steam, its primary

case end when it had made its judgement. Anxious function was to bolster the position of the studio

to dispel rumours that the studios maintained an heads. By keeping contractual disputes firmly un-

unofficial blacklist of troublemakers, its members der wraps, it reinforced a discourse of popular en-

worked hard to ensure that successful complain- tertainment that diverted public attention away

ants did not suffer as a consequence of challeng- from the sphere of production and denied screen

ing their employers. In the case of Rita LaRoy, the actors a collective identity as industrial workers

actress dismissed from the set of Call Her Savage locked in an unequal relationship with their em-

for refusing to unbutton her dress, for instance, ployers.

they wrote to the actress's erstwhile employer, theIn its original incarnation as a champion of

FoxFilm Corporation, recommending that she be industrial peace, the Academy of Motion Picture

offered another part as soon as possible. '[E]very Arts and Sciences lasted only a few years. By early

opportunity for the establishment of confidence, 1933, the movie industry was in serious financial

cooperation, and trust should be taken advantage trouble, gross box-office receipts having fallen by

of by both sides', they advised. a third since the onset of the Depression. The major

studios responded to the crisis by implementing

[We must avoid] any possible charge that one

wage cuts of up to 50 per cent to last for a period

can be discriminated against because of com-

of eight weeks, a move which antagonised actors

plaints brought to the Academy for adjust-

both inside and outside the Academy. When two of

ment. This case, if handled as per our

the industry's biggest players, Warner Bros. and

recommendation, we feel will go a long way

Goldwyn, failed to restore salary levels at the end

to establishing that such discrimination does

not exist75.

of the eight weeks, several Academy members re-

signed and joined with a group of anti-Academy

In truth, though, the Academy as it operated actors to form the Screen Actors Guild. Initially, at

in the late 1 920s and early 1 930s was not so much least, the new organisation attracted little interest

a mechanism for protecting the rights of workers as in Hollywood. Its efforts to organise the screen ac-

a means of keeping Hollywood's labour troubles tors received a boost, however, when the National

out of the public gaze. A letter from Donald Gled- Recovery Administration, a body created by the

hill, Executive Secretary of the Academy, to B.F. federal government to oversee the implementation

Zeidman at Universal in which he took the studio of the National Industrial Recovery Act, convened

to task for leaking to the newspapers the details of in August 1 933 to formulate a code of practice for

a 1934 case involving character actor Warren the movie industry. Though the Academy was sup-

Hymer makes explicit the collective agenda of its posed to represent the screen acting community in

architects. 'The story in the trade press about thethe negotiations, its officials allowed the studio

Warren Hymer Adjustment Committee hearing heads to insert into the initial draft of the NRA Code

seems to have been given out by the studio', Gled- a series of clauses which were utterly unacceptable

hill wrote. to the majority of screen actors, stars and non-stars

alike. When the document was made public,

While it probably did no harm in this instance, twenty-one of Hollywood's biggest names re-

you can see that if each side released its own signed from the Academy in protest at what they

version of each controversy, the result would saw as a betrayal of their collective interests and

be to keep the disputes and, in some cases, cast their lot with the nascent Screen Actors Guild.

This content downloaded from

137.204.24.180 on Sun, 27 Sep 2020 18:05:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

112112 Sean P. Holmes Sean P. Holmes

tors' Labor (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota,

Stripped o

1995).

play an ac

2. King, 'The Star and the Commodity', 1 45.

troubles. T

3. King, 'The Star and the Commodity', 145.

fectively o

In an arti

4. Clark, Negotiating Hollywood, p. x.

sen issued a call for what he termed 'a workers' 5. Clark, 'Actors Labor and the Politics of Subjectivity',

history of the film industry in the United States' - a 38-39. The book at which Clark's criticsm is di-

rected is Robert C. Allen and Douglas Gomery, Film

history, that is, that rests upon the central premise

History: Theory and Practice (New York: Knopf,

that film is the product of human labour78. 'A full 1985).

critical review [of the operation of the industry]', he 6. Clark, 'Actors' Labor and the Politics of Subjectivity',

insisted, 'must merge dispassionate analysis of 22-23.

structures with the real-life stories of those most 7. The narrative portion of Clark's work is based largely

affected by the workings of the industry - the work- upon Louis B. Perry and Richard S. Perry, A History

of the Los Angeles Labor Movement, 1911-1941

ers themselves'79. By rescuing screen actors from

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1963) and

the sphere of consumption and focusing attention Murray Ross, Stars and Strikes: The Unionization of

upon the social relations of production that have Hollywood (New York: Columbia University Press,

1941).

determined the terms of their commodification,

scholars like Barry King and Danae Clark have 8. On mass production and the managerial revolution

in the Hollywood-film industry, see Janet Staiger,

taken us halfway towards that goal. What we do 'Mass Produced Photoplays: Economic and Signify-

not find in their carefully theorised analyses of the ing Practices in the First Years of Hollywood', in Paul

star system, however, are the voices of the men and Kerr, ed., The Hollywood Film Industry (London and

New York: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1986), pp.

women who have sold their labour in the Holly- 100-1 03; Janet Staiger, 'Dividing Labor for Produc-

wood 'dream factory'. As Clark has made clear, tion Control: Thomas Ince and the Rise of the Studio

the struggle between actors and their employers System', in Gorham Kindem, ed., The American

Movie Industry: The Business of Motion Pictures

over the terms of their representation and self-rep- (Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois

resentation has been an unequal one. Yet to sug- University Press, 1982), pp. 94-102; David Bord-

well, Janet Staiger and Kristin Thompson, The Clas-

gest that producers in the 1920s and 1 930s were

sical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Production

entirely successful in their efforts to silence actors to 1960 (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1985),

as workers is misleading. As this paper demon- pp.88-95, 128-153.

strates, screen actors in the studio era, like other 9. On differentiation as an economic imperative, see

groups of workers in industrial America, were Staiger, 'Mass-Produced Photoplays', pp.

107-108; Bordwell, Staiger, and Thompson, The

neversilent. If, as historians, we wish to make sense

Classical Hollywood Cinema, pp. 96-102.

of their collective experiences in the cinematic

10. On the role of advertising in directing consumers to

workplace, we have a responsibility to listen to sources of exchange value, see Bordwell, Staiger,

what they had to say.f and Thompson, The Classical Hollywood Cinema,

pp.99-100.

Notes 11. Report on the Affairs of the Vitagraph Company of

America, The Examinations Corporation, March

1. See Barry King, 'Stardom As An Occupation', in Paul

191 7, Albert E. Smith Papers, Box 10, Special Col-

Kerr, ed., The Hollywood Film Industry (London and

lections Department, University of California, Los

New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1984), pp.

Angeles.

154-184; King, 'Articulating Stardom', Screen 26

(September-October 1985): 27-50; King, 'The12.Star

On the film industry's increasing reliance on outside

and the Commodity: Notes Towards A Performancecapital, see Janet Wasko, Movies and Money: Fi-

Theory of Stardom', Cultural Studies 1:2 (1987): nancing the American Film Industry (Norwood, New

145-161; Danae Clark, 'Actors' Labor and the Jersey: Ablex Publishing Company, 1982), pp.

Politics of Subjectivity: Hollywood in the 1930s' 17-45.

(Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of

13. Richard de Cordova, Picture Personalities: The

Iowa, 1989); Clark, 'Acting in Hollywood's Best

Emergence of the Star System in America (Urbana

Interests: Representations of Actors' Labor During

and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1990), p.

the National Recovery Administration, Journal of 112.

Film and Video 42.4 (Winter 1990): 3-19; Clark,

Negotiating Hollywood: The Cultural Politics of

14.Ac-

Clark, 'Actors' Labor and the Politics of Subjectivity',

7-8.

This content downloaded from

137.204.24.180 on Sun, 27 Sep 2020 18:05:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Hollywood star system and the regulation of actors' labour 113

15. Kevin Brownlow, The Parade's Gone By (London: 35. George Andre Beranger vs. William Fox Company,

Martin, Secker & Warburg, Ltd., 1968; reprint edi- 3 October 1 931, Actors Adjustment Committee, File

tion, London: Columbus Books, Ltd., 1989), p. 39. B.

16. Don El Mere and Audrey El Mere v. RKO, 28 July 36. Willie Fung vs. MGM, 7 July 1934, Academy Col-

1934, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences lection, Actors Adjustment Committee, File F.

Collection, Margaret Herrick Library (hereafter 37. Nowell to Gillmore, 30 July 1924.

Academy Collection), Actors Adjustment Commit-

tee, File E. 38. Stanley Fields vs. William Fox Company, 12 Septem-

ber 1932, Academy Collection, Actors Adjustment

17. Ralph Ince v. RKO, 29 February 1932, Academy Committee, File F.

Collection, Actors Adjustment Committee, File I.

39. Salary figures are from Richard Koszarski, An Eve-

18. Zena Bear v. Radio Transcription Company, 12 ning's Entertainment: The Age of the Silent Feature

September 1932, Academy Collection, Actors Ad- Picture, 1915-1928 (Berkeley and London: Univer-

justment Committee, File B. sity of California Press, 1990), pp. 114-116,

266-268.

19. Brownlow, The Parade's Gone By, pp. 59-60.

40. Brownlow, The Parade's Gone By, p. 334.

20. Brownlow, The Parade's Gone By, p. 40.

41. Brownlow, The Parade's Gone By, pp. 333-334.

21. For Henabery's claims about health problems

amongst extras and bit players in Hollywood, see 42. Brownlow, The Parade's Gone By, pp. 330-331.

Brownlow, The Parade's Gone By, p. 60. 43. Brownlow, The Parade's Gone By, p. 334.

22. General Savitsky vs. William Fox Company, 1 March 44. King, 'Stardom As An Occupation', pp. 167-168.

1933, Academy Collection, Actors Adjustment

Committee, File S. 45. Clark, 'Acting In Hollywood's Best Interest', 6.

46. Gladys Hall, 'Diamond-Studded Whims', Motion

23. Jack Kenny vs. William Fox Company, 25 July 1 930,

Academy Collection, Actors Adjustment Committee, Picture (July 1929), 34.

File K.

47. Untitled clipping, Los Angeles Times, 22 June 192

24. Report of the Adjustment Committee, 12 June 1930, n.p. in Goudal, Jetta, microfilmed clippings file,

Margaret Herrick Library, Los Angeles (hereafter

Academy Collection, Actors Adjustment Committee,

File 'Matthew Betz vs. MGM'. Herrick Library).

48. 'Long Arm of Coincidence Replaces Goudal on

25. Florence Oberle to E. B. Derr, Path6 Studios, 9

High', unsourced clipping, 21 June 1931 in

August 1930, Florence Oberle vs. Path6 Studios,

Goudal, Jetta, microfilmed clippings file, Herrick

Academy Collection, Actors Adjustment Committee,

Library.

File O.

49. On the reproduction of such power struggles as

26. Rose Plumer vs. Twentieth Century, 30 August 1933, 'gripping narratives', see Jane M. Gaines, Con-

Academy Collection, Actors Adjustment Committee,

tested Culture: The Image, The Voice, and The Law

File P.

(Chapel Hill and London: University of North Caro-

27. On Evalyn Knapp and the 'grease paint poisoning' lina Press, 1991), p. 146.

incident, see Evelyn [sic] Knapp vs. Universal Produc- 50. Untitled clipping from unidentified Oklahoma City

tions, 18 October 1933, Academy Collection, Ac- newspaper, September 1925, n.p. in Goudal, Jetta,

tors Adjustment Committee, File K. microfilmed clippings file, Herrick Library.

28. Clark, Negotiating Hollywood, p. 19. 51. Untitled clipping, Los Angeles Examiner, 1 February

1929, n.p. in Goudal, Jetta, microfilmed clippings

29. Report sheet, Academy Collection, Actors Adjust-

file, Herrick Library.

ment Committee, File 'LaRoy, Rita vs. William Fox

Company #209, 25 October 1932'. 52. Untitled clipping from unidentified Oklahoma City

newspaper, September 1925, n.p. in Goudal, Jetta,

30. Isabel Cotton to William Conklin, 26 May 1930,

microfilmed clippings file, Herrick Library.

Academy Collection, Actors Adjustment Committee,

File C. 53. Untitled clipping, Brooklyn Standard, 1 August

1927, n.p. in Goudal, Jetta, microfilmed clippings

31. Barry King, 'Articulating Stardom', 47. file, Herrick Library.

32. Louis Wolheim, 'I Prefer the Movies to the Stage' 54. Unsourced clipping, 7 January 1927, n.p. in

Theatre Magazine 46 (September 1927), 41. Goudal, Jetta, microfilmed clippings file, Herrick

Library.

33. Wedgewood Nowell to Frank Gillmore, 30 July

1924, Actors' Equity Association Collection, Robert 55. Untitled clipping, Los Angeles Examiner, 1 February

Wagner Labor Archives, New York University (here- 1929, n.p. in Goudal, Jetta, microfilmed clippings

after AEA Collection), Box MX1, Folder 'Motion file, Herrick Library.

Pictures - Hays Negotiations, 1924'.

56. Unsourced clipping, 2 February 1929 in Goudal,

34. Nowell to Gillmore, 30 July 1924. Jetta, microfilmed clippings file, Herrick Library.

This content downloaded from

137.204.24.180 on Sun, 27 Sep 2020 18:05:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

114 Sean P. Holmes

57. Unsourced clipping, 5 February 1929 in Goudal,

70. For a digest of the Academy contract, see Academ

Jetta, microfilmed clippings file, Herrick Library. of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Bulletin, No. 6

(1 January 1928), p. 2, Academy Collection, Herrick

58. Unsourced clipping, 18 March 1929 in Goudal,

Library.

Jetta, microfilmed clippings file, Herrick Library.

71. On employee representation schemes in the 1920s,

59. Statement of Jetta Goudal before the Actors Adjust-

see Howell John Harris, 'Industrial Democracy and

ment Committee, 26 June 1930, 'Goudal, Jetta vs.

Liberal Capitalism, 1890-1925' in Nelson Lichten-

MGM Case #58', Academy Collection, Concili-

stein and Howell John Harris, eds. Industrial Democ-

ation Committee Files.

racy in America: The Ambiguous Promise

60. Decision of Actors' Branch Executive Committee, 8 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), pp.

August 1930, 'Goudal, Jetta vs. MGM Case #58', 60-65; Lizabeth Cohen, Making A New Deal: Indus-

Academy Collection, Conciliation Committee Files. trial Workers in Chicago (New York and Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 1990), pp. 171-1 73.

61. On Goudal's health problems, see unsourced clip-

72. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Bulle-

pings, 23 May 1930 and 21 June 1930 in Goudal,

Jetta, microfilmed clippings file, Herrick library. tin, No. 1, 1 June 1927, p. 1, Academy Collection,

Herrick Library.

62. 'Long Arm of Coincidence Replaces Goudal on

73. On the Actors' Equity Association in Hollywood, see

High', unsourced clipping, 21 June 1931 in

Goudal, Jetta, microfilmed clippings file, Herrick Sean P. Holmes 'Organizing the Dream Factory: The

Library. Actors' Equity Association in Hollywood,

1919-1929', unpublished paper.

63. Clark, Negotiating Hollywood, p. 20. For more on

the process of fragmentation, see Clark, Negotiating 74. Statistics relating to the activities of the Academy

Hollywood, pp. 18-23; Clark, 'Actors' Labor and Conciliation Committee are from 'The Academy and

the Politics of Subjectivity', 85-90. the Actor', Academy of Motion Picture Arts and

Sciences Bulletin, No. 22, 9 July 1929, pp. 1-2,

64. Brownlow, The Parade's Gone By, pp. 60-61. Academy Collection, Herrick Library.

65. On IATSE and the signing of the Studio Basic Agree- 75. Actors Adjustment Committee to Winfield Sheehan,

ment, see Ross, Stars and Strikes, 13-18. Fox Film Corporation, 13 May 1933, Academy

66. On the formation of the Academy of Motion Picture Collection, Actors Adjustment Committee, File

Arts and Sciences, see Hugh Lovell and Tasile Car- 'LaRoy, Rita vs. William Fox Company #209, 25

October 1932'.

ter, Collective Bargaining in the Motion Picture In-

dustry (Berkeley, California: Institute of Industrial 76. Donald Gledhill, Executive Secretary of the Academy

Relations, 1955), p. 35; Ross, Stars and Strikes, p. of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences to B. F. Zeidman,

27; Harding, 'The Motion Pictures Need A Strong Universal Studio, 10 December 1934, Academy

Actors' Union', 286-287; Harding, The Revolt of the Collection, Actors Adjustment Committee, File

Actors, p. 536. 'Hymer Warren vs. Universal Studio, 19 November

1934'.

67. On the pay-cut controversy, see Ross, Stars and

Strikes, p. 27; Perry and Perry, History of the Los 77. On the founding of SAG and the demise of the

Angeles Labor Movement, pp. 338-339; Harding, Academy, see David F. Prindle, The Politics of Glam-

'The Motion Pictures Need A Strong Actors' Union', our: Ideology and Democracy in the Screen Actors

287-88; Harding, The Revolt of the Actors, pp. Guild (Madison: University of Wisconsin, 1988), pp.

536-537. 16-25.

68. For the full text of the resolution, see Academy of

78. Michael Nielsen, 'Towards A Workers' History of the

Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Bulletin, No. 3, 2US Film Industry', in Vincent Mosco and Janet

July 1927, Academy Collection, Herrick Library. Wasko, eds., The Critical Communications Review,

Volume 1, Labor, The Working Class, and the Media

69. See the letter from the film bosses to the Academy

(Norwood, New Jersey: Ablex Publishing Corp,

reproduced in Academy of Motion Picture Arts and

1983), pp. 47-83.

Sciences Bulletin, No. 3, 2 July 1927, Academy

Collection, Herrick Library. 79. Nielsen, 'Towards A Workers' History,' p. 48.

This content downloaded from

137.204.24.180 on Sun, 27 Sep 2020 18:05:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- The Star System: Hollywood's Production of Popular IdentitiesFrom EverandThe Star System: Hollywood's Production of Popular IdentitiesNo ratings yet

- Operation Cyclone How The United States Defeated The Soviet Union PDFDocument17 pagesOperation Cyclone How The United States Defeated The Soviet Union PDFMaoNo ratings yet

- Vladimir Putin's Remarkable Life Story Revealed in His Own WordsDocument4 pagesVladimir Putin's Remarkable Life Story Revealed in His Own WordsKaragiozis KaragiozidisNo ratings yet

- Playing the Percentages: How Film Distribution Made the Hollywood Studio SystemFrom EverandPlaying the Percentages: How Film Distribution Made the Hollywood Studio SystemNo ratings yet

- 1 A-2 Contemporary Political - Robert E. Godin PDFDocument26 pages1 A-2 Contemporary Political - Robert E. Godin PDFNaThy GarciaNo ratings yet

- The Institutionalization of Educational Cinema: North America and Europe in the 1910s and 1920sFrom EverandThe Institutionalization of Educational Cinema: North America and Europe in the 1910s and 1920sNo ratings yet

- Filmhistory 30 1 01 PDFDocument20 pagesFilmhistory 30 1 01 PDFPablo GonçaloNo ratings yet

- Materializing Adaptation TheoryDocument18 pagesMaterializing Adaptation TheoryErika Aranza Flores BlancasNo ratings yet

- The Cinema of Isolation A History of Physical Disability in The Movies (Norden, Martin F.) (Z-Library)Document405 pagesThe Cinema of Isolation A History of Physical Disability in The Movies (Norden, Martin F.) (Z-Library)claudialinharessanzNo ratings yet

- Architecture FilmmakingFrom EverandArchitecture FilmmakingIgea TroianiNo ratings yet

- Useful CinemaDocument8 pagesUseful CinemaPintor PerezaNo ratings yet

- A Transactional Geography of The Image EventDocument15 pagesA Transactional Geography of The Image EventSantiago Moreno CastañedaNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Auteur Metteur en SceneDocument8 pagesDissertation Auteur Metteur en SceneCanYouWriteMyPaperForMeSiouxFalls100% (1)

- Hollywood Genres PDFDocument24 pagesHollywood Genres PDFte_verde_con_miel88% (8)

- OppenheimerDocument265 pagesOppenheimerjeanzetaNo ratings yet

- Collective BargainingDocument65 pagesCollective BargainingapplexuyapingNo ratings yet

- The Hollywood Mode of ProductionDocument233 pagesThe Hollywood Mode of ProductionAndres AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Historical Journal of Film, Radio and TelevisionDocument4 pagesHistorical Journal of Film, Radio and TelevisionJorge SotoNo ratings yet

- 14 From Primitive To ClassicalDocument19 pages14 From Primitive To ClassicalΣταυρούλα ΝουβάκηNo ratings yet

- Scholarship@Western Scholarship@Western: Western University Western UniversityDocument33 pagesScholarship@Western Scholarship@Western: Western University Western UniversityPaola Susana Mendoza ChampiNo ratings yet

- Screen 2014 Uricchio 119 27Document9 pagesScreen 2014 Uricchio 119 27NazishTazeemNo ratings yet

- Authorship in Classic Hollywood Cinema L PDFDocument18 pagesAuthorship in Classic Hollywood Cinema L PDFCarlos GonzalezNo ratings yet

- On Beauty and Cinema: What Analytical Philosophy SaysDocument33 pagesOn Beauty and Cinema: What Analytical Philosophy SaysFidel NamisiNo ratings yet

- 6-Reenacting RyanDocument16 pages6-Reenacting RyanGülçin ÇaktuğNo ratings yet

- Screen Volume 25 Issue 6Document104 pagesScreen Volume 25 Issue 6znajarian_najafiNo ratings yet

- Dressing The Part and Taking PartDocument7 pagesDressing The Part and Taking Partamytribe82No ratings yet

- Patrick Phillips - English and Media Mag 35 Autumn 1996Document4 pagesPatrick Phillips - English and Media Mag 35 Autumn 1996Steve BennisonNo ratings yet

- Military Modes of RepresentationDocument22 pagesMilitary Modes of RepresentationMasha ShpolbergNo ratings yet

- Dudley Andrew - Core and Flow of Film Studies PDFDocument40 pagesDudley Andrew - Core and Flow of Film Studies PDFleretsantuNo ratings yet

- Circulación y uso del cine útil en la primera mitad del siglo XXDocument19 pagesCirculación y uso del cine útil en la primera mitad del siglo XXMartín FernándezNo ratings yet

- Reagan - Rambo - and The Red Dawn - Ohiou1180975486Document112 pagesReagan - Rambo - and The Red Dawn - Ohiou1180975486AeosphorusNo ratings yet

- Thomas Elsaesser - James Cameron S Avatar Access For AllDocument19 pagesThomas Elsaesser - James Cameron S Avatar Access For AllB CerezoNo ratings yet

- Introducing Transnational Cinemas - Shaw y de La GarzaDocument4 pagesIntroducing Transnational Cinemas - Shaw y de La GarzarigobertigoNo ratings yet

- Heroic Imagery in Vadakkan Pattu Films and Kerala Varma Pazhasi Raja (Binu Raj)Document11 pagesHeroic Imagery in Vadakkan Pattu Films and Kerala Varma Pazhasi Raja (Binu Raj)9072474412No ratings yet

- '" Comfortably Assimilated AsDocument33 pages'" Comfortably Assimilated Aspierre CaoNo ratings yet

- Future of Adaptation TheoryDocument19 pagesFuture of Adaptation Theorybenjaminarticle100% (1)

- Six Approaches To Writing About Film: StreetDocument8 pagesSix Approaches To Writing About Film: StreetmaipleNo ratings yet

- From Book To FilmDocument17 pagesFrom Book To FilmAmnaNo ratings yet

- Josef Chytry - Walt DisneyDocument21 pagesJosef Chytry - Walt DisneyJose Luis FernandezNo ratings yet

- Society For Cinema & Media Studies, University of Texas Press Cinema JournalDocument21 pagesSociety For Cinema & Media Studies, University of Texas Press Cinema JournalAymen TarhouniNo ratings yet

- CDA-Cultural Consecration of American Filmes - Patrick - LincolnDocument24 pagesCDA-Cultural Consecration of American Filmes - Patrick - LincolnMaritza Colmenares TamayoNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 118.71.190.165 On Tue, 16 Aug 2022 15:28:38 UTCDocument20 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 118.71.190.165 On Tue, 16 Aug 2022 15:28:38 UTCseconbbNo ratings yet

- Adaptation Theory Simone MurrayDocument18 pagesAdaptation Theory Simone MurrayElle MêmeNo ratings yet

- Theories of Film Andrew Tudorpdf - CompressDocument170 pagesTheories of Film Andrew Tudorpdf - CompressDebanjan BandyopadhyayNo ratings yet