Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Optional Offenheimer - Holcombe - Challenges of Implementing ZRBA 2003

Uploaded by

Eleana BaskoutaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Optional Offenheimer - Holcombe - Challenges of Implementing ZRBA 2003

Uploaded by

Eleana BaskoutaCopyright:

Available Formats

Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly

http://nvs.sagepub.com/

Challenges and Opportunities in Implementing a Rights-Based Approach to Development: An Oxfam

America Perspective

Raymond C. Offenheiser and Susan H. Holcombe

Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 2003 32: 268

DOI: 10.1177/0899764003032002006

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://nvs.sagepub.com/content/32/2/268

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

Association for Research on Nonprofit Organizations and Voluntary Action

Additional services and information for Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://nvs.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://nvs.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Citations: http://nvs.sagepub.com/content/32/2/268.refs.html

Downloaded from nvs.sagepub.com at TUFTS UNIV on October 12, 2010

Challenges and Opportunities

10.1177/0899764003251739

Offenheiser,

in Implementing

Holcombe

a Rights-Based Approach FORUM

FORUM

Challenges and Opportunities in Implementing

a Rights-Based Approach to Development:

An Oxfam America Perspective

Raymond C. Offenheiser

Oxfam America

Susan H. Holcombe

Brandeis University

Two practitioners/thinkers take old ideas about human rights and make a new case for an

economic and social rights-based approach to development. Our mid-20th century prede-

cessors recognized—in Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms and in the Universal

Declaration of Human Rights—that a secure world requires a social contract that assures

everyone access to basic economic and social rights. In today’s globalized world, the pri-

vate sector and civil society join the state in influencing the ability of the marginalized to

enjoy basic rights. Pursuing a rights-based approach is an end to business as usual for

international development nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). NGOs will need to

move beyond supporting delivery of services to building the capacity of civil society to be

an organized and effective balance to the power of governments and of the private sector.

This transformation will have profound effects on the basic business plans, evaluation

systems, and staff competencies of international development NGOs.

Keywords: rights-based approach; human rights; economic and social rights; right to

development; civil society organizations; Oxfam; implementing rights;

social contract; the state and rights; justice; equity; globalization and

rights; legitimacy; rights

In the late 1990s, the members of the Oxfam International community under-

took a serious reexamination of their development programming, searching

for the common philosophical threads that united their development practice.

Our goal was to reach deep into our organizational cores and ask what we

believed was most important in the way development programs were being

Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, vol. 32, no. 2, June 2003 268-306

DOI: 10.1177/0899764003251739

© 2003 Association for Research on Nonprofit Organizations and Voluntary Action

268

Downloaded from nvs.sagepub.com at TUFTS UNIV on October 12, 2010

Challenges and Opportunities in Implementing a Rights-Based Approach 269

conceived and implemented. Our hope was to find the essential elements for

forging a common project and building the trust and understanding among

our organizations, staff, and partners to carry it out.

This process of reflection and planning led us to conclude that the Oxfam

approach to development and humanitarian response was fundamentally

anchored in a rights-based perspective, with a particular focus on social, eco-

nomic, and cultural rights. At first glance, that was hardly surprising. Most

Oxfam staffs think that they have always supported human rights, and indeed

a cursory review of past programming would show a strong presence of

grants to partners representing the interests of marginal groups or arguing for

greater civil and political rights. Concern for rights has woven its way through

partner relations, probably throughout the history of most Oxfam affiliates.

Yet rights had never been articulated as the overarching framework for our

development practice. The funding portfolio of Oxfam field offices contained

a wide range of programs, from social service delivery to hard-edged human

rights work, but the concept that people have basic rights to livelihoods, social

services, security, voice, and protection from exclusion had not been fully

thought through and developed.

The conscious choice to center all programming on a rights-based approach

and to emphasize economic, social, and cultural rights represents a major shift

for all Oxfam affiliates (Oxfam International, 2000). It forces each organization

to reexamine its funding portfolio and to ask some tough questions about the

relevance of particular partner relations to a rights-based agenda within each

country. It compels a deeper examination of the state’s role as the guarantor of

rights, and of the means that individuals require to exercise those rights. It

requires us to look at civil society as an essential vehicle for citizens to amplify

their voice and counterbalance governmental and private-sector power in

shaping the social contract. It reframes the discussion about effect, evaluation,

and development practice. It suggests the need to examine the core of the

Oxfam business model and see if it really supports a rights-based approach. It

raises serious questions about staff competencies and the ability to envision

and support programs that are rooted in a rights perspective.

This article explores some of the rationales that have led Oxfam Amer-

ica—as a member of Oxfam International—to embrace a rights perspective, as

well as the conceptual constructs that support the new paradigm and the chal-

lenges to implementation it poses. The first section probes the historical cir-

cumstances that have marginalized economic and social rights and focused

international dialogue on political and civil rights. The second section ana-

lyzes the philosophical and conceptual foundation that supports implementa-

tion of a rights-based approach in development practice and humanitarian

response. The final sections explore the organizational and management chal-

lenges that flow from the use of the rights-based model as an organizing prin-

ciple for development practice.

Downloaded from nvs.sagepub.com at TUFTS UNIV on October 12, 2010

270 Offenheiser, Holcombe

DEVELOPMENT MODELS AND

THE HISTORY OF HUMAN RIGHTS

Why has Oxfam America embraced a rights-based approach? What does it

offer that is essentially new and different? Why has it taken so long to decide

that this approach makes sense and can be incorporated into development

practice? Why does it appear to be so relevant now? Answering these ques-

tions begins with an understanding of the shortcomings of previous strategies

and their relationship to an evolving definition of human rights.

DISILLUSIONMENT WITH THE WELFARE MODEL

Most development programming is rooted in Western European and

American notions of the welfare state that emerged in the early years of the

20th century. This model defines poverty as the absence of some particular set

of public goods or body of technical knowledge. If the state or another mecha-

nism can deliver these public goods or services or introduce the missing tech-

nical know-how, it is assumed that poverty can be reduced and development

will occur.

Over the decades, dialogue within the development community has been

largely confined to the narrow orbit of welfarism, seldom questioning its core

precepts. Instead, debate has focused on three issues:

1. How are the public goods or technical knowledge delivered to the poor?

2. What is the missing input or catalyst—seeds, nutrition, or family planning

strategy—that will power development?

3. Which crucible—state-led infrastructure expansion and industrialization,

or the market—can most efficiently reduce poverty and spur development?

For 50 years, we tinkered with a welfarist approach. Development institutions

were created to manage the effort, and billions of dollars were poured into the

struggle. Despite some real achievements, the gap between rich and poor is

widening, the numbers of people in poverty are increasing in many parts of

the world, and hundreds of millions are trapped in conditions that pose

long-term dangers to the welfare of everyone. The World Development Report

2000/2001 (World Bank, 2000) notes the seriousness of deepening poverty and

widening inequity. Nearly one half the world’s people live on less than $2 per

day, and one fifth live on less than $1. Income disparities have widened within

countries—North and South—and the gap between the world’s 20 richest and

20 poorest countries has more than doubled from 1960 to 1995.

For 50 years we assumed that governments first, and then the market,

would provide for basic needs, but each has failed to address the deeper prob-

lems of social justice and transform the embedded systems that reproduce

poverty. It is not enough to assume that a rising tide will lift all ships because

evidence shows that for a given rate of growth, poverty falls faster in countries

Downloaded from nvs.sagepub.com at TUFTS UNIV on October 12, 2010

Challenges and Opportunities in Implementing a Rights-Based Approach 271

where income distribution has grown more equal (World Bank, 2000). Despite

what seems to be a deliberate character to the sustained impoverishment in

some societies, we lack systems to hold governments and economic institu-

tions accountable for their actions or inaction. Government efforts to address

problems are half-hearted or underfunded, or promised funds are diverted

into the pockets of urban-based actors who make a profitable career as gate-

keepers of foreign-aid programs. The poor are treated as objects of charity

who must be satisfied with whatever crumbs drop their way.

RIGHTS-BASED DEVELOPMENT AS AN ALTERNATIVE MODEL

The rights-based approach envisions the poor as actors with the potential

to shape their own destiny and defines poverty as social exclusion that pre-

vents such action. Instead of focusing on creating an inventory of public goods

or services for distribution and then seeking to fill any deficit via foreign aid,

the rights-based approach seeks to identify the key systemic obstacles that

keep people from accessing opportunity and improving their own lives (Cen-

ter for Economic and Social Rights, 1995). From the very outset, the focus is on

structural barriers that impede communities from exercising rights, building

capabilities, and having the capacity to choose.

Viewed in this fashion, development is about assisting poor communities

to overcome obstacles rather than about never-ending pursuit of grants for

social goods. It assumes that poor people have dignity, aspirations, and ambi-

tion and that their initiative is being blocked and frustrated by persistent sys-

temic challenges, such as apartheid, biased lending policies, and

nonfunctioning state social service delivery systems. It assumes that those

who are most directly affected know firsthand what institutional obstacles

thwart their aspirations and who are essential actors in deciding what to do

about it. Rather than imposing cookie-cutter solutions, this strategy is

anchored in the reality of local context. A primary problem, indeed, has been

the inability of outside actors to imagine adequately the situation confronting

the poor. Some of that blindness, ironically enough, is a byproduct of the emer-

gence of a rights-based culture in the late 20th century whose progress in civil

and political rights came at the cost of ignoring economic and social rights

(Lauren, 1998). The opportunity for change today depends on understanding

how the definition of human rights narrowed and must now be broadened.

A UNIFIED VISION OF HUMAN RIGHTS

The 1940s were a golden age for defining human rights, and economic and

social rights were integral to the dialogue. Franklin D. Roosevelt included

freedom from want as the third of the Four Freedoms established as an Ameri-

can objective in World War II. In 1944, Roosevelt called on Congress to find the

means to implement an “economic bill of rights” that focused on the right to a

livelihood and to social services. In 1948, the Universal Declaration of Human

Downloaded from nvs.sagepub.com at TUFTS UNIV on October 12, 2010

272 Offenheiser, Holcombe

Rights gave global recognition to economic and social rights. The framers of

the declaration, led by the first chairperson of the UN Commission on Human

Rights Eleanor Roosevelt (Glendon, 2001), were not fuzzyheaded idealists;

they understood how a failed social contract had contributed to the Great

Depression and two world wars. They saw the need for a new social contract

to prevent future war in an age of mass destruction.

Although the Covenant on Economic and Social Rights amplified the

meaning of these rights in 1966, the politics of the Cold War exerted constant

pressure that eventually focused the global human rights movement on politi-

cal and civil rights, relegating economic and social rights to the care of the mar-

ket.1 Generations of Americans have grown up believing that human rights

refer exclusively to civil and political rights. In the United States, the Cold War

increasingly was seen as a competition between economic systems—between

capitalism and markets on one hand, and socialism and state planning on the

other. In addition, from the perspective of the ultimate winners, this incorpo-

rated the struggle for human rights, which was depicted as a zero-sum battle

between freedom and the tyranny of an “evil empire,” between individual lib-

erty and the power of the state.

Attempts, chiefly from the South, to raise concerns about economic rights

(e.g., the New International Economic Order) were isolated by the

dichotomized mind-set of the Cold War. The end of the Cold War certified the

failure of the totalitarian socialist model, and accelerating globalization put

severe pressures on Western social democracies as well. Trade-led models of

economic growth combined with the internationalization of capital flows to

create a world economy modeled on an unregulated market economy

(McMurtry, 1998). The paradox is that economic globalization began leapfrog-

ging the frameworks of laws, norms, and civil societies that restricted excesses

and created domestic social stability within the very national economies

whose private-sector firms were now leading the way in world markets

(Korten, 2001). The absence of any clearly defined short-term threat to the

social order undermined the rationale for urgent assistance to reduce inequi-

ties during the 1990s, leaving globalization as the default development para-

digm. Globalization, to the world’s financial leaders, is about the integration

of markets. The solution to poverty was for third world countries to join the

bandwagon and reinvent themselves as emerging markets, dropping barriers

to imports and capital, cutting public budgets, and privatizing state assets to

create the conditions for optimal economic growth and profits. The assump-

tion is, as it has been for decades, that development is economic growth and

nothing more. If GNP is high, all is well with the world. This leaves political

and civil rights dominant in the human rights dialogue and in the discourse of

international affairs, giving free reign to imposition of market-based prescrip-

tions by multilateral financial institutions.

Meanwhile, civil society actors were left to confront not only the legacy of

failed social policies by the state but deep cuts in state spending. Globalization

offered no Midas touch for the problems of failed education systems,

Downloaded from nvs.sagepub.com at TUFTS UNIV on October 12, 2010

Challenges and Opportunities in Implementing a Rights-Based Approach 273

collapsing health systems, inadequate water supplies, privatized commons,

and ethnic discrimination that defined the world of the poor. Serious

responses by the international community to these problems are few. Foreign

aid is dwindling. Sectarian conflicts proliferate, driving poverty. G-7 nations

must be dragged, guilt tripped by the Pope himself, to the altar to sign on to

debt relief. Understandably, civil society leaders are seeking a new language

and new approaches to deal with these harsh realities.

During the 1990s, the dialogue on rights began to shift. The UN sponsored a

major series of summits on economic and social rights that drew their legiti-

macy from the UN’s earlier work on the Human Rights Charter (Korey, 2001).

As a result of these meetings and exposure to the language of the Charter and

its endorsement of economic, social, and cultural rights, civil society organiza-

tions (CSOs)—like the women’s and the environmental movements before

them—began to see rights as a lever for change (Lauren, 1998; Eade, 1998).

Growing unease about the merits of globalization has fueled the drive to

reconnect civil and political with social, economic, and cultural rights. Many

of the disparate actors who gathered in Seattle to protest against the World

Trade Organization (WTO) found that the discourse on social and economic

rights was the glue that bound them together. Old adversaries, like U.S. labor

organizations and developing-world nongovernmental organizations

(NGOs), realized that they actually shared many core values and could work

together on a range of issues within the framework of economic and social

rights.

These new sociopolitical realities made it possible to rekindle the kind of

rights perspective that Franklin and then Eleanor Roosevelt brought to the

founding discussions of the Charter, without fear of being labeled a socialist or

communist. Yet traditional rights organizations did not rush to fill the space

that was opening to readdress economic and social rights. Before the 50th

anniversary celebration of the UN Charter in 1998, a number of people

approached the major human rights organizations (including Amnesty Inter-

national and Human Rights Watch) to sound out their willingness during the

ceremonies to call for social, economic, and cultural rights. It became clear that

these organizations feared that their supporters and donors might miscon-

strue such a call as a dilution of their core mission and vision. They also cited

the great work yet to be done in addressing critical challenges to civil and

political liberties in Asia and the former Soviet Union—consolidating work

that had built their reputations and given them a clearly identified institu-

tional niche. The unspoken irony in this understandable strategic choice was

how it perpetuated the Cold War dichotomy between civil and political and

social and economic rights in the public consciousness.

Oxfam leadership was surprised to find that the human rights organiza-

tions were leaving the area of social, economic, and cultural rights unat-

tended. Recognizing the need for a prominent global organization to cham-

pion social and economic rights, Oxfam decided to focus on implementing a

rights-based approach in the field and to become more active in their home

Downloaded from nvs.sagepub.com at TUFTS UNIV on October 12, 2010

274 Offenheiser, Holcombe

countries in putting these issues on the public policy agenda. With this in

mind, Oxfam leadership moved to reposition its brand in the public mind as

centered on social and economic justice and implemented through a

rights-based approach (Oxfam International, 2000).

A RIGHTS-BASED FOUNDATION

FOR DEVELOPMENT PRACTICE

Mainstreaming a rights-based approach into our organizations is a com-

plex transition. It cannot simply be decreed and implemented. If sound blue-

prints are to be drawn from this vision, an organization needs to deepen its

understanding of the philosophical principles involved and how they apply

on the ground in local development contexts. The underlying justifications for

new relationships and a rethinking of old ones must be aired if the public is to

understand the reasons for transformation and staff members are to follow the

lead and flesh out the shift in organizational culture with workable develop-

ment programs. This section outlines the Oxfam America perspective on the

soundness of a rights-based approach to development.

BROADENING OUR VISION OF HUMAN RIGHTS

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights served as the Magna Carta for

human rights activism over the past 50 years. Without question, the human

rights movement, using the Declaration as an international norm, has made

significant contributions to promoting civil and political liberties. Unfortu-

nately, it has failed to address issues of poverty and social injustice.

In his paper, “The Human Rights Challenge to Global Poverty,” Chris

Jochnick (1999) presented a major challenge to narrow traditional approaches

to human rights. He argued that we have entered a new era and that human

rights activists and development theorists need to think outside the box and

devise new and more compelling ways of utilizing the Human Rights Charter.

One reason the vision has remained narrow, Jochnick argued, particularly

in the United States and to a lesser degree in Western Europe, is the predomi-

nance of a state-centered view of human rights. Continuing this practice in an

era of globalization renders one powerless to prevent or remedy violations of

social and economic rights by nonstate actors from beyond national borders.

Moving human rights beyond its state-centric paradigm serves two pur-

poses. First, it challenges the reigning neo-liberal extremism that trivializes

much public discourse about development and poverty, providing a rhetoric

and a vision to emphasize that entrenched poverty is neither inevitable nor

acceptable. Second, it provides a legal framework with which to begin holding

the most influential nonstate actors—corporations, financial institutions, and

third-party states—more accountable for their role in creating and sustaining

poverty.

Downloaded from nvs.sagepub.com at TUFTS UNIV on October 12, 2010

Challenges and Opportunities in Implementing a Rights-Based Approach 275

Jochnick (1999) reminded us that “the distinction between individuals as

the holders of rights and states as the holder of duties was premised on the

notion of the state as the ultimate guardian of the public’s welfare” (p. 3). In

essence, the state derives this authority and responsibility from the social con-

tract agreed to by its citizens. The Commission on Global Governance sug-

gested that we live in different times. When the UN system was created, the

nation-state was dominant and had few rivals, and there was strong faith in

the protective ability of governments. The world economy was not so inte-

grated. “The vast array of global firms and corporate alliances that has

emerged was just beginning to develop. The huge global capital market,

which today dwarfs even the largest national capital markets, was not fore-

seen” (p. 3).

Jochnick argued that the “narrow focus of human rights law on state

responsibility is not only out of step with current power relations but tends to

obscure them” (p. 3). It neglects the decreasing power of the nation-state and

perpetuates the belief that states are only accountable to their populations and

vice versa. Focusing on the state in a globalizing world may shield other actors

(the private sector and international institutions) from responsibility and

leave the poor and the human rights movement fighting for justice with both

hands tied behind their backs.

In encouraging the human rights movement to revisualize their work,

Jochnick said that “the real potential of human rights lies in its ability to

change the way people perceive themselves vis-à-vis the government and

other actors” (p. 3). By using the rhetoric of rights, “problems” can be exam-

ined as possible “violations,” that is, as discrimination or structures that block

people from exercising rights. Violations are not inevitable; therefore, they

need not be tolerated: “By demanding explanations and accountability,

human rights expose the hidden priorities and structures behind violations”

(p. 4). This broader view, providing both economic and social content and

applying accountability to nonstate actors, is a vital step toward addressing

the root causes of poverty and development.

The keystone of Jochnick’s presentation is his contention that the broader

view of human rights is closely connected to their original foundation in

human dignity. Noting that under international law, states either consent to

treaties or acquiesce to customary norms, he underlined a significant excep-

tion. “Human rights law,” he added, “has in large measure defied these nar-

row categories by suggesting an additional foundation—human dignity.

Human dignity makes certain claims on all actors, state and non-state, regard-

less of custom or consent” (p. 4). As supporting evidence, Jochnick empha-

sized that the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the twin covenants

of 1966 not only recognize customary or agreed-to rights, but also those

derived “from the inherent dignity of the human person.”2 By extending

human rights beyond the narrowness of consent or custom, this allows for rec-

ognition of a variety of nonstate actors as human rights violators.

Downloaded from nvs.sagepub.com at TUFTS UNIV on October 12, 2010

276 Offenheiser, Holcombe

There are important lessons for development organizations like Oxfam to

take from Jochnick’s presentation.

• He challenged the traditional cleavage between development and rights

work, calling for a reexamination based on the philosophical underpin-

nings of international law and the stress globalization is placing on his-

toric conceptions of the state.

• He reintroduced the concept of human dignity as the foundation for

rights and showed us how human dignity is imbedded in human rights

concepts, providing development professionals with new ways of think-

ing about how to link their concerns. 3

• He showed us how a human rights framework can provide a more mor-

ally and ethically forceful tool for development professionals to use in

naming the inequalities in power relations, along with the structures

that sustain social inequity and injustice.

• He offered an approach that can begin with a concern for people and

their needs, one that acknowledges the role of the state but also recog-

nizes that violations of human dignity may have their origins with

nonstate actors.

• He demonstrated how a rights-based approach can challenge the fatal-

ism embedded in the very logic of the welfarist approach to poverty alle-

viation.

THE SOCIAL CONTRACT AND THE RIGHT TO DEVELOPMENT

We next need to examine the implications Jochnick’s broader, integrated

definition of human rights has on development thinking. Approaching

human rights as inherent and indivisible and centering our development

work on the pursuit of social, economic, and cultural rights, we are in effect

arguing for development itself as a human right, and one, moreover, that is

integral to the social contract.

Arjun Sengupta’s (2000) excellent paper, “The Right to Development as a

Human Right,” provided insight on the implications of this argument.

Sengupta first reminded us of the intimate connection between human rights

and social contract theory. Social contract theory was, in effect, a secular ren-

dering of the ancient biblical concept of a contract between God and Abraham,

with the people choosing their governors rather than God. Natural rights the-

orists in the Western tradition—Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau—were propo-

nents of the contract concept (Barker, 1969). Locke claimed that certain rights,

such as life, liberty, and property, belonged to individuals and not to society as

a whole because these rights existed before entering civil society. Entering civil

society meant agreeing to a social contract, but this contract only surrendered

to the state the right to enforce these natural rights, not the rights themselves.

The French Revolution of 1789 was supported by natural rights theorists

under the premise that the sovereign had broken the terms of the social

Downloaded from nvs.sagepub.com at TUFTS UNIV on October 12, 2010

Challenges and Opportunities in Implementing a Rights-Based Approach 277

contract by not securing these rights for his people. The French Declaration of

the Right of Man and Citizen stated that the rights of life, liberty, property,

security, and resistance to oppression were “natural, inalienable and sacred.”

Sengupta acknowledged that there are very few contemporary proponents

of natural rights but suggested a powerful argument for deriving economic,

social, and cultural rights from emerging global norms. The basic ideas behind

the social contract still exist and are codified within national constitutions

around the world. These legal documents provide the procedures and rules,

which national governments are expected to uphold, for protecting and pro-

moting individual and collective rights. The very existence of a regime of

rights is linked to the willingness of citizens to cede power and authority to the

state in exchange for certain protections of their human dignity under the

terms of a social contract.

For such social contracts, what is important is the acceptance by all parties

of a set of human rights that the state parties are obliged to fulfill. In the ulti-

mate analysis, human rights are those rights that are given by people to them-

selves. They are not granted by any authority, nor are they derived from some

overriding natural or divine principles. They are human rights because they

are recognized as such by a community of peoples, flowing from their own

conception of human dignity, in which these rights are supposed to be inher-

ent. Once they are accepted, through a process of consensus building, they

become binding at least on those who are party to that process of acceptance.

Taking this argument a step further, Sengupta reminded us that the interna-

tional community undertook just such a process of consensus building at the

Vienna Conference of 1993, which agreed that the right to development was a

human right. The Declaration of the Vienna Conference, as established in the

Declaration on the Right to Development, reaffirmed the right as universal,

inalienable, and an integral part of fundamental human rights.4 This declara-

tion, which was supported by the United States, stated that, “Human rights

and fundamental freedoms are the birthright of all human beings; their pro-

tection and promotion is the first responsibility of government” (Sengupta,

2000, pp. 1-2). It also committed the international community to the obligation

of cooperation in actualizing these rights. In the final analysis, development

emerged as a human right that reintegrated economic, social, and cultural

with civil and political rights in the manner envisaged at the beginning of the

post–World War II human rights movement. The world was returning to the

mainstream of human rights activism from which it had been deflected for so

many years by Cold War international politics.

Although the international community may have endorsed the right to

development through the Vienna declaration, debate and controversy still

surround the approval of this bold initiative (Katrougalos, N.D.). Moreover,

on a more practical level, one might note that because of the declaration’s

approval, the foreign aid budgets for most of the G-7 nations have seen a pre-

cipitous decline. The evidence suggests that the political leaderships of these

countries have invested little in selling this concept to their electorates and

Downloaded from nvs.sagepub.com at TUFTS UNIV on October 12, 2010

278 Offenheiser, Holcombe

instead have concentrated on managing their nations’ participation in global

markets.5

Sengupta (2000) identified three major challenges to the notion of develop-

ment as a human right. The first objection is that human rights adhere only to

individuals and therefore are based only on negative freedoms, such as the

freedom to life, liberty, and free speech, which the state must merely guaran-

tee. In contrast, economic and social rights are associated with positive free-

doms that the state must secure, protect, and finance through active promo-

tion. As such, they are not seen as natural rights, and they have budget

implications. A second objection posits that economic and social rights must

be coherent, that is, each right-holder must have some corresponding

duty-holder responsible for delivering the right. Finally, some argue that a

right exists only if it is enforceable through law and adjudication. Because eco-

nomic and social rights are not legally adjudicative, the argument continues,

they cannot be human rights. The next section responds by examining the role

civil society plays in negotiating terms of the social contract with government.

The third section amplifies that response in its discussion of rights-based pro-

gram implementation.

LINKING RIGHTS WITH FIELD-BASED REALITIES

Development professionals need a practical conceptual base to orient their

work in making the major shift to a rights-based approach. To translate the

essence of this new vision into a guide for practice, Oxfam America has devel-

oped a series of simple models to capture the most strategically critical dimen-

sions of the rights-based approach. These diagrams grossly oversimplify

many social and political complexities, but they have proved useful in assist-

ing staff to comprehend the core dynamics of this new approach.

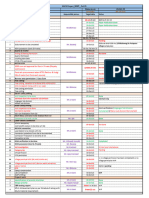

Figure 1 illustrates the rights-based model at the national level. Its founda-

tion is civil society. The model presumes that in every nation, civil society is

the primordial soup that shapes social affairs, the state, and the economy. The

exact nature of civil society, its density and diversity, its inclusiveness, its

racial profile, its political cleavages, and its internal culture and dynamics, are

presumed to vary widely across national boundaries.

The next prominent feature of the model is the state’s relationship to the

economy, which can range across a gradient from central planning to an unfet-

tered private market. The diagram presumes that the particular shape and

scale of the relationship is determined based on a social contract established

between the citizens and civil society leaders of a country and its political lead-

ership. The social contract is not a written document, but rather the conferral

of public trust to those leaders who demonstrate their willingness to govern

under the rule of law. The social contract assumes rights and obligations on the

part of the ruler and the governed. The social contract is grounded in the

notion of legitimacy, the belief that government power ultimately rests not on

Downloaded from nvs.sagepub.com at TUFTS UNIV on October 12, 2010

Challenges and Opportunities in Implementing a Rights-Based Approach 279

Social contract

Constitution

Debate on

rights and

how state

manages State Economy Exclusion of

public goods segments of

society

Civil/Political Environmental Social/Econ

Civil Society

Civil society actors

Figure 1. Rights-Based Development Model (National Level)

force but on the consent of the governed. This unwritten understanding is the

glue that holds a society and a nation together.

Our diagram presumes that the social contract defines the relationship

between the state and the economy. Figure 1 shows a somewhat limited inter-

section, depicting a state that retains regulatory control over some important

functions of the market and its various actors. One can also imagine other pat-

terns, for example, a socialist state in which the overlap or intersection

between state and economy would be almost complete (see Figure 1A). At the

other extreme, the free market model might push the economy apart from

state control toward minimal or no regulation. It might also shrink the power

of the state, so one could imagine a diagram in which the economy dwarfs the

state in terms of resources, power, and extraterritorial relationships.

Each nation is theoretically capable of setting the terms of this state/economy

relationship based on the nature of its political process and the substance of its

social contract. In reality, there are both external and internal constraints. Pres-

sures to abandon traditional social-service functions to reduce budget deficits

can come externally from multilateral financial institutions and capital mar-

kets or internally from export promotion or privatization policies. Even basic

public services like health and education may be affected. A national

Downloaded from nvs.sagepub.com at TUFTS UNIV on October 12, 2010

280 Offenheiser, Holcombe

Economy

State

State Economy

1. Socialist model 2. Free market model

Economy

State

3. Economy dwarfs state power model

Figure 1A. Relationships Between the State and the National Economy

government may also feel constrained by the wishes of other states or by

nonstate actors with their own agendas and the power to challenge the state’s

authority and even its sovereignty. Internally, a state may lack the capacity to

deliver on its social contract obligations to citizens, or its ability may be com-

promised by corruption. Although some reorganization of state functions is

often needed for greater efficiency, the elimination of social investments in

education and health has had dire consequences for millions of children in

Africa and Asia. Several generations of young people have grown up lacking a

basic education. In addition, their governments have been powerless to

deliver on a social contract for basic social rights.

Ideally, the voice of citizens and civil society actors finds expression in a

nation’s constitution. The constitution can be a living document that spells out

the basic terms of an evolving social contract, capturing the social aspirations

of a society as well as the terms for the relations between citizens and the state.

Most important, the constitution establishes the rights of citizens. Citizens

and the civil society institutions that represent their interests negotiate with

the state on the exact nature and quality of rights. For explanatory purposes in

Figure 1, we single out distinct bodies of rights. Although the UN Charter of

Human Rights treats civil, political, social, economic, and cultural rights as

Downloaded from nvs.sagepub.com at TUFTS UNIV on October 12, 2010

Challenges and Opportunities in Implementing a Rights-Based Approach 281

indivisible, in practice civil and political rights are usually enshrined in a

national constitution and highlighted in a bill of rights—as is the case with the

U.S. Constitution. Meanwhile, social, economic, and cultural rights must be

fought for politically and either added to a bill of rights or legitimated through

legislation, administrative law, judicial action, or changes in the informal con-

sensus underlying the social contract.

It is precisely at the interface between the state and economy where civil

society plays its most crucial role. This interface occurs in the legislative pro-

cess where laws are passed and budgets approved and where the state’s man-

agement of public goods should be debated. It is also found in the executive

process where policies are formulated and leadership can be exercised. In this

crucible, civil society organizations hold the state accountable for delivering

on the promised social contract. Viewed in this fashion, development might be

seen as a process of deal making between a government and its citizenry over

how state resources, revenues, and services are shared among citizens and

how the national economy will or will not be required to serve the public

good.

The final element of the national model shows the barrier or barriers that

exclude certain people or civil society organizations from full participation in

the negotiating process to allocate state resources and set criteria for economic

performance. These barriers may exclude based on race, ethnicity, religion,

caste, gender, or class. They may be obvious and harsh like apartheid, or sub-

tle like voter registration procedures or standards of creditworthiness. They

might curtail the simple exercise of one’s civil and political rights or be arcane

protocols in assembling certain public-sector budgets. An ostensibly demo-

cratic nation should show high degrees of inclusion. The United States has

made significant progress in advancing civil rights for all citizens at the

national level. However, at the local and regional levels, institutional, eco-

nomic, and social racism still maintains a strong hold. The key to advancing a

rights-based agenda is identifying the precise nature of local as well as

national barriers.

In thinking about its role within this universe, Oxfam America intends to

focus its scarce resources on programs that support partners in negotiating

this interface with the state on social and economic rights. It is conceding that

the mainstream human rights organizations should lead the way in the pur-

suit of civil and political rights and environmental groups should continue to

provide leadership in the pursuit of environmental rights. Oxfam America

aspires to play the kind of leadership role for economic and social rights in the

United States and in its overseas relations with partners that these other rights

organizations have played in their arenas of concern.

The model in Figure 1 has proved flexible enough for staff to adapt it to

national contexts and manipulate its internal elements to fit a particular social

and political reality. The model can also be adapted to analyze a regional, or

even the global, level.

Downloaded from nvs.sagepub.com at TUFTS UNIV on October 12, 2010

282 Offenheiser, Holcombe

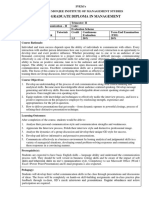

Figure 2 offers a rudimentary diagram for the emerging system of global

governance. In this configuration, we see three institutional actors with inter-

locking mandates: the UN, international financial institutions (IFIs), and the

World Trade Organization (WTO). Beyond this triad is a fourth element—the

global economy—which is relatively loosely linked to the governing agents, is

still evolving, and is gathering force that makes it critical to future global secu-

rity. In theory, a state negotiates the interests (rights) of its citizens in the global

institutions. In practice, states that represent powerful actors in the global

economy tend to have the largest voice, whereas those that do not are rela-

tively powerless.

Nonetheless, a countervailing force has begun to emerge. The model por-

trays a small, but growing number of transnational civil society actors who

seek to shape and influence these global institutions. Not surprising, barriers

limit the access of transnational civil society actors to the process of agenda

setting and decision making by global institutions. Representatives of private

capital generally enjoy unfettered access to the decision-making table, for

example in WTO deliberations on the terms of global trade. Few mechanisms

allow the voices of civil society to be heard.

This diagram seeks to capture the essential problem of global governance,

which the Seattle protests spotlighted by calling into question the authority of

the WTO, the IFIs, and their patrons. Because there is no clear social contract

giving them a mandate, these global institutions lack the legitimacy of

national governments. This sense of disparity has been growing. Although

national governments participate in the governance of these institutions, their

representation reflects GDP more than population; and because globalization

has extended the reach and mission of these institutions, their decisions

increasingly affect citizens around the world. There are differences in vision

and ideology among leaders within these institutions, but by and large, the

globalized market model of development is shared and shapes the way devel-

opment goals are framed and policies implemented. This obviously has enor-

mous effect on the developing world, but it affects everyone. Decisions taken

by these global institutions are seen increasingly as undermining, if not abro-

gating, the social contracts between citizens and states. The perceptible shift in

power from the national to the global is experienced as disenfranchisement

because at the global level citizens have little direct voice and reliable repre-

sentation. Meanwhile, private capital, which has been the big winner in the

globalization sweepstakes, is well represented through a variety of institu-

tional connections, corporate-sponsored events, consultancies, policy analy-

sis, and lobbying.6

This gives rise to the kind of challenges to the legitimacy and accountability

of private capital suggested in Figure 3. With no social contract to guide global

governance, diverse sectors compete for voice and influence in shaping the

global agenda. States represented in these institutions express their national

interests. Corporations and business alliances promote their interests directly

Downloaded from nvs.sagepub.com at TUFTS UNIV on October 12, 2010

Challenges and Opportunities in Implementing a Rights-Based Approach 283

Social Contract?

Exclusion of

segments of

IFI’s UN WTO society

System

Civil Society

Transnational Civil Society actors

Figure 2. The Emerging System of Global Governance

at the global level, and indirectly through their influence on state representa-

tives. The media aggressively promote their agendas. Finally, global networks

of national and international NGOs struggle even to get a seat at the table.

To translate many of the underlying assumptions of this model into a sim-

ple planning tool for staff, the Oxfams agreed to adopt a set of five basic pro-

gram aims (Oxfam International, 2000):

• the right to a sustainable livelihood

• the right to basic social services

• the right to life and security

• the right to be heard (social and political citizenship)

• the right to an identity (gender and diversity)

Each Oxfam has taken these core aims, which reflect the core elements of the

UN Human Rights Charter, and attempted to incorporate them into its institu-

tional strategy. In essence, the idea is to turn the right to development into a set

of succinct planning goals.

Downloaded from nvs.sagepub.com at TUFTS UNIV on October 12, 2010

284 Offenheiser, Holcombe

Global Governance

system

Civil

States Society

Non-state Media

actors Other civil

Elected society groups

officials

Private Sector Public monitor

Figure 3. Legitimacy, Accountability, and the Challenge of Global Governance

Staff are asked to work with colleagues from their sister Oxfams to develop

regional and country plans that benefit one, two, perhaps even three of these

aims. For each aim, staff is expected to develop context-specific strategic

change objectives and outcome indicators to guide programming. Effective-

ness is to be measured by the effect of programs on specific policy and practice

changes that address critical barriers to opportunity.

Meanwhile, on a global level, staff working on policy and public education

is expected to use these same aims to plan global advocacy that aligns their

strategic choices with critical priorities of partners at the regional level. For

instance, concerns about the effect of the growing HIV/AIDS epidemic on

grassroots communities in and the health budgets of many African nations in

which we work has led Oxfam to the forefront of the global campaign for fairly

pricing pharmaceuticals to treat the disease. During the last 4 years, the

Oxfams have also carried out a campaign focusing on basic education. A

major strategic feature of this campaign has been its success at linking local

realities to global debates. The foundation for this campaign has been the

assertion that education is a basic human right, intrinsically linked to the UN

Charter, the provisions on social and economic rights, and a variety of subse-

quent UN summit documents. Now, broad concerns about the effect of trade

Downloaded from nvs.sagepub.com at TUFTS UNIV on October 12, 2010

Challenges and Opportunities in Implementing a Rights-Based Approach 285

rules on the livelihoods of low-income farmers has convinced Oxfam to align

program efforts of staff from 12 affiliates, working in over 100 countries, and

launch a major campaign in 2003 to reform the rules.

The campaigns on HIV/AIDS pharmaceuticals and education have taught

us how useful the social and economic rights construct can be in putting local

faces on global issues to inform the media, the public, and their representa-

tives of what is at stake. It has also proved to be a powerful tool to help us align

our work across multiple program levels and across regions. It has proved

equally powerful in providing an ethical basis for challenging the overly sim-

plistic logic of the champions of the globalization paradigm. It enables Oxfam

to provide powerfully incisive normative critiques that cut through the turgid

language and technocratic rationales of the major global power brokers and

their minions, and show the human costs. This has proved to be surprisingly

appealing to the global media who often report on the downsides of globaliza-

tion from the field but find little in the way of persuasive counterarguments to

link the evidence to the big picture highlighting who is responsible and how

the damage can be repaired and further damage avoided.

Previously, development work was most often seen as disconnected inter-

ventions in very specific local and national contexts. The human rights focus

of our work today is unifying these diverse experiences, enabling us to see

from multiple perspectives much more clearly the kinds of power relations

that drive and the systemic impediments that perpetuate poverty. Our early

experience has shown the power of this conceptual framework. Now we face

the challenges of implementing it as an operational reality.

CONFRONTING THE CHALLENGES OF IMPLEMENTATION

In addition to Oxfam, many Northern NGOs—Save the Children, World

Vision, and CARE, for example—are moving toward a rights-based frame-

work for building a global movement for development and change. This

framework reunites economic and social with political and civil rights, pre-

paring the way for a comprehensive vision of a new, just, and viable social con-

tract. Yet few Northern development NGOs have deep experience with the

new paradigm, making implementation of it a learning challenge.

Effective implementation answers Sengupta’s (2000) three critiques of the

notion of development as a human right. As noted earlier, Sengupta argued

first that human rights adhere only to individuals and therefore are based only

on negative freedoms, such as freedom to life, liberty, and free speech. The

state has the role of guarantor. Because economic rights are positive freedoms

that the state must promote and finance, they are not considered natural

rights. Second, to be coherent, economic and social rights require that some

duty-holder be responsible for delivering those rights to individual

rights-holders. Third, if rights exist only when they are enforceable through

law, economic and social rights cannot be human rights because they are not

Downloaded from nvs.sagepub.com at TUFTS UNIV on October 12, 2010

286 Offenheiser, Holcombe

legally adjudicative. As the next paragraphs suggest, these objections rein-

force a welfarist perspective. By drawing narrow boundaries where only

states grant rights, they imply a paternalistic, top-down perspective. We take a

broader view of the actors and visualize the enjoyment of rights as a spiraling

rather than a linear process. People give meaning to rights by exercising them.

The exercise of rights—economic, social, and political and civil—is synergis-

tic. It creates capacity to protect and extend rights.

Jochnick (1999) addressed the question of boundary drawing and trans-

gression, suggesting that one must look beyond the duties and prerogatives of

the state to resolve systemic violations of human rights, particularly in the eco-

nomic and social spheres. States, as we have seen, have been woefully inade-

quate in redressing inequalities. This is not just a question of resources but of

responsibility. Nonstate entities—corporations, financial institutions, and

global institutions—may act in ways that help create or sustain poverty. They

may impinge on rights (cash out the commons, if you will) without taking

responsibility for assuring rights (investing to sustain the commons).

A broader view of human rights looks beyond state responsibilities and a

legalistic approach and grounds itself in the concept of human dignity. Indi-

viduals are seen as actors with knowledge, skills, and the capacity to organize.

Citizens and their civil society organizations, operating at the interface

between the state and the economy, become key to making the rights-based

model work.

A rights-based approach to development bridges theoretical gaps between

political, civil, social, and economic rights by understanding how they are

interconnected in practice. During the past half-century, specialized civil soci-

ety organizations like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have

effectively spotlighted violations of political and civil rights, using the “stick”

of adverse publicity to halt violations, case by case. Civil society has yet to

focus on the “carrots” needed to build social, cultural, and institutional capac-

ity and to create a positive environment that makes honoring rights our new

norm. To take a preventive rather than a corrective approach to violations of

political and civil rights, development organizations also need to focus on

building the economic and social rights that enable people to effectively exer-

cise and defend their citizenship.

NGOs taking on this challenge must create their own road maps. More than

20 international agreements on universal human rights were reached during

the 20th century. Establishment of fundamental principles and standards was

a necessary first step, but these conventions provided no guidelines for navi-

gating local realities and few provisions for reporting compliance, much less

enforcing it. Furthermore, this approach has been essentially top-down, based

on an unstated assumption that rights can be “given” to individuals and

groups. This unidirectional focus is fundamentally flawed because it fails to

recognize that rights originate with the people who exercise them.

Downloaded from nvs.sagepub.com at TUFTS UNIV on October 12, 2010

Challenges and Opportunities in Implementing a Rights-Based Approach 287

Working to empower marginalized citizens within states and to build a

global civil society to rein in transnational institutions, Northern NGOs are

positioned to play a pivotal role, but the new opportunities are fraught with

hazards. Becoming an active CSO in a rights-based framework exposes poten-

tial contradictions in legitimacy and accountability. Symptoms of this can be

seen in the tensions that arise with Southern partners as a result of economic

and other inequalities. This problem is not new, but it was easier to ignore

when welfarism was the dominant ethos. Another problem, however, is new.

How does one achieve conceptual clarity to heighten public perception of a

new social contract whose terms are not prewritten but must evolve through

ongoing civic engagement?

THE ROLE OF NORTHERN NGOS IN AN AGE OF GLOBALIZATION

Conceptual clarity requires moving beyond abstract declarations to gain an

operational understanding of the circumstances under which rights can be

freely exercised. If international conventions have set benchmarks for the

state’s role in human rights, there is no consensus yet about the responsibili-

ties of nonstate actors. Citizens and the groups they form need to be able to

hold states and nonstate actors accountable for respecting rights.

Rights-based Northern CSOs thus face a dual task. They seek to play a

bottom-up role supporting marginalized groups in their efforts to attain and

exercise their rights within nations, while also fostering nascent global move-

ments to promote accountability across national borders. Operating at multi-

ple levels to link local with national and global concerns requires nimbleness

and a fundamental change in traditional operating assumptions. If

marginalized groups are to have the capability to exercise rights, they must

have independence and agency. They can no longer be viewed as passive

recipients of welfarist support from Northern NGOs but must be seen as

actors in their own destinies and partners in our common destiny. Most

Northern NGOs (and even government and multilateral aid agencies) now

routinely talk of partnership with organizations and people in the South.

Northern CSOs need to be honest and recognize that funding inequities have

too often reduced partnership to a patron-client relationship. A rights-based

partnership assumes that actors in the South bring irreplaceable assets to the

effort to secure economic and social justice. The funding, information, and

links that Northern agencies bring are essential but not sufficient. Putting

these assumptions about real partnership into action challenges Northern

agencies to rethink their agenda setting, funding, and accountability pro-

cesses. Previously the donor set the agenda and sometimes changed it fre-

quently without consulting beneficiaries about the effect. Donors measured

project and program effectiveness by quantifiable short-term outcomes. The

new model requires negotiating a shared agenda. It may mean providing

funding for the longer term and asking the Southern partner to be accountable

Downloaded from nvs.sagepub.com at TUFTS UNIV on October 12, 2010

288 Offenheiser, Holcombe

for process-oriented as well as concrete results. Because lasting success

depends on organization building, Northern NGOs need the courage to stick

with Southern partners who show the ability to learn from failure and cope

with reverses. Because Northern CSOs do not operate in a vacuum, they have

to engage their own donors in a dialogue about the changing priorities and

demands of these new relationships.

Rights-based CSOs in the North and South need to rethink the meaning of

program and implementation to encompass activities once thought of as

peripheral or overhead. The new model requires more activities like research,

advocacy, evaluation, public education, and organizational development.

Because resources are limited, some funding will likely be shifted from direct

services to the poor toward efforts that target the underlying causes of pov-

erty. This shift complicates accountability and relationships with key stake-

holders, raising questions of legitimacy.

BUILDING LEGITIMACY THROUGH A CHAIN OF VALUE

As Northern rights-based agencies seek genuinely new partnerships to

develop new models of implementing change, questions of legitimacy arise.

Playing a service delivery role gives clarity to what an agency does, and legiti-

macy is derived from the competence of the work. Agencies negotiating for

economic and social change or pressing for policy change have long-term

agendas that are not easy to quantify. They are accountable to multiple constit-

uencies, including donors, boards, and partner organizations in the South and

the excluded groups with whom they work.

Legitimacy in this model is dynamic and is created when a Northern CSO

connects a range of stakeholders—North and South—seeking to expand the

opportunity and ability to exercise economic and social rights. Legitimacy

comes from the value chain linking donors, publics, the board, and staff with

Southern CSOs and excluded people in a common agenda.

Connecting the stakeholders in Tambogrande, Peru. Around the world, the eco-

nomic and social rights of poor people are often overridden where wealth is

found in their natural resources. The only lasting remedy is to empower local

communities to assert their rights and acquire influence over important deci-

sions affecting their lives.

In Tambogrande, Peru, a Canadian mining company acquired a license

from the Peruvian government to establish a massive surface mine that would

displace one half the town’s population. It would probably severely damage

the water and air quality essential to their health and traditional farming

culture.

For years, Oxfam America has supported an indigenous rights group in

Peru called Coordinara Nacional de Comunidades Afectadas por la Mineria

(CONACAMI). This group helps communities to organize, conduct research

on environmental effects, and inform and mobilize local citizens about the

Downloaded from nvs.sagepub.com at TUFTS UNIV on October 12, 2010

Challenges and Opportunities in Implementing a Rights-Based Approach 289

dangerous and negative effects of mining. In Tambogrande, CONACAMI

helped local leaders organize a referendum that rejected establishing the

mine. Oxfam America brought further pressure to bear on the mining com-

pany through an online alert that brought 5,000 emails to the president of the

company urging him to honor the results of this referendum. The government

is now for the first time negotiating with Oxfam and community leaders.

From the local to international levels, Oxfam has supported the efforts of

this small rural community to strengthen their voices in demanding their

rights to control the environment in which they live. With scientific informa-

tion, community organization, media effect, and the use of technology to

enlist public support, Oxfam has helped this community finally command the

attention of the government.

In helping to forge this chain, a Northern CSO’s accountability begins with

the need for clarity in adding value. Its area of comparative advantage may

rest in advocacy for policy and practice changes in Northern-based institu-

tions. It may, for example, be more valuable and more legitimate to pressure

the World Bank or IMF to change structural adjustment policies that exacer-

bate poverty and starve domestic education budgets than to fund a sprinkling

of new village schools. As a shift to advocacy and policy work grows, the real-

ity and perception of what the Northern CSO is and does may blur. To main-

tain legitimacy in its value chain, Northern CSOs will need to find better ways

of explaining to donors and publics why advocacy may have greater effect

than traditional contributions of “pigs and shovels.”

Northern CSOs will also need to respect boundaries and not engage in

advocacy in the primary political space of Southern partners. This is practical

and an issue of principle. Just as Northern CSOs have a comparative advan-

tage in advocacy with their own governments, so their partners are better

placed to exploit the opportunities and avoid the dangers of advocacy in their

own arenas. More fundamental, a rights-based agenda will be meaningless if

Southern partners and marginalized communities cannot speak in their own

voice and act in their own behalf.

Amplifying and respecting partners’ voices in Zimbabwe. The legitimacy chal-

lenge is constant and requires skilled political analysis, sensitivity, and judg-

ment. For example, Oxfam America funded women’s organizations in Zimba-

bwe to conduct a national education campaign on how proposed

constitutional changes would give primacy to traditional law that awards a

dead husband’s property to his brother, not his wife. It also supported

women’s organizations in educating women voters, particularly in rural

areas, on the issues at stake in a parliamentary election. In doing so, Oxfam

had to carefully analyze the environment and tactfully avoid moving into

Zimbabwean political space so as not to endanger its partners and its staff.

This kind of judgment requires investment by Oxfam in sensitive leadership

on the ground.

Downloaded from nvs.sagepub.com at TUFTS UNIV on October 12, 2010

290 Offenheiser, Holcombe

STRENGTHENING LEGITIMACY

THROUGH TRANSPARENCY

Public transparency to hold powerbrokers accountable for their actions has

been a rallying cry for CSOs. The outcry has forced public officials and

nonstate institutions to be more accountable to citizens, but these successes

have led governments and others to turn the spotlight around and scrutinize

the operations of CSOs. Some governments and publics once assumed that

CSOs were efficient because they worked close to the problems being tackled.

Now the honeymoon is over.

More than ever, CSOs are being challenged to be more transparent about

their own operations, and be accountable to performance standards measur-

ing their effectiveness. Some challenges come from donor governments

demanding better evidence of the value of their diminishing foreign aid; oth-

ers come from recipient governments eager to undermine donor support to

Northern CSOs; and still others come from an increasingly skeptical citizenry

that wants to know more about how their donations will directly benefit poor

people.

The challenge faces all NGOs but is greatest for rights-based CSOs because

their efforts to change structures and systems by redistributing power to allow

greater equity in accessing a decent livelihood, basic social services, security,

and other economic and social rights is much harder to measure. The outputs

of service delivery agencies are concrete; it is easier to quantify the efficiency

of their work. Indeed much of the international language for measuring per-

formance, including development assistance committee (DAC) indicators or

those of the International Standards Organization (ISO), is designed to cap-

ture tangible results (such as numerical increases in schools or children’s vac-

cinations) within specific intervals.7 The critical work of economic and social

rights-based organizations is often missed by using these short-term indica-

tors. Is an advocacy effort a failure because it did not transform a policy over-

night? How does one measure the pay-offs from capacity building? That is,

when and how do advocacy and investments in organizational capacity make

a difference in the lives of poor people?

Donor pressures for evaluation systems based on narrow indicators of

accountability can be counterproductive. They may force CSOs back into the

role of being state subcontractors for service delivery, leading them to aban-

don their core missions of advocating and instituting economic and social

change. Short-term quantitative indicators devalue the long-term contribu-

tion CSOs make in policy formulation and program development. This does

not mean that rights-based Northern NGOs should not be held accountable. It

means that more accurate standards need to be developed.

CSOs can contribute by investing resources in defining their work and set-

ting benchmarks of progress toward systemic changes that can be communi-

cated to stakeholders. This is easier said than done. First, the mission is

Downloaded from nvs.sagepub.com at TUFTS UNIV on October 12, 2010

Challenges and Opportunities in Implementing a Rights-Based Approach 291

political and therefore likely to spark controversy. By asserting rights for live-

lihoods, basic services, security, and participation, a commitment is made to

changing the rules of the game, thus creating a new balance of power or social

contract. This process is Burkian rather than revolutionary. It seeks to trans-

form rather than overturn the system, to support incremental reforms that

may yield mixed results over the short and medium terms, but create an irre-

sistible momentum for long-term democratic change.

Keeping a steady course will not be easy because rights-based CSOs have

multiple stakeholders with overlapping, but not always convergent, interests.

Unlike private-sector firms accountable to boards and stockholders for return

on investment, or welfare/service delivery organizations accountable to

donors and recipients for efficient provision of services, economic and social

rights CSOs are accountable to donors, partner organizations, and allies for

results that may be differently perceived in the short run and that are not easily

described much less quantified. Donors understandably want to see concrete

results in the lives of poor people now. Investing to change the rules of the

game may appear quixotic or even radical to citizens and governments in the

North that view the struggle for economic and social rights through the Cold

War prism of the New International Economic Order or the now defunct

socialist model. Engaging private and public donors in the dialogue about a

new social contract is therefore essential to the transformative mission and

vision of an economic and social rights organization.

Dealing with tensions among diverse stakeholders requires careful listen-

ing to identify within the noise the area where interests converge and bringing

that to the fore. There is an essential synergy between the ability to communi-

cate the common purpose and the ability of strategic leadership to build

cross-functional focus on specific outcomes that fit into a rights-based vision.

Specific changes in rules, structures, and systems must be linked to an evolv-

ing social contract and demonstrably generate sustainable improvements in

people’s lives. One must also show that such changes are not a zero-sum

game, but cumulatively beneficial for all segments of global society. For exam-

ple, tariff protections for fledgling industries, real land reform, or protections

and living wages for workers in Mexico and Central America might be a better

long-term investment for North Americans than fortifying the Mexico-U.S.

border.

Communicating complexities requires more than the nanoseconds of

sound bites available in today’s world. Expanding the audience and its atten-

tion span starts with an investment in staff who combine communication

skills with a sophisticated understanding of the issues and players. Accessible

digests must be developed to show how long-term structural changes or

adjustments to the social contract result in win-win benefits. Benchmark indi-

cators and stories that make them personal must be captured at the local,

national, and global levels to show how changes have affected or failed to

affect the lives of individuals and communities. Will donors be willing to

Downloaded from nvs.sagepub.com at TUFTS UNIV on October 12, 2010

292 Offenheiser, Holcombe

support the shift in budget allocations required to pay for improved advo-

cacy? They will if they understand how the new priorities are not designed to

replace good fieldwork but extend it.

BUILDING CREDIBILITY TO SPEAK TRUTH TO POWER

Rights-based Northern CSOs may be small compared to the task before

them and relatively powerless compared to government and the private sec-

tor in defining terms of the social contract, but when they are able to articulate

their message skillfully their voice can resonate powerfully. This power stems

from their credibility. The recent, effective campaign for World Bank debt for-

giveness demonstrates its effectiveness.

The credibility of Northern CSOs is grounded in their connections to

marginalized peoples and communities, giving them a front-row view of

what causes poverty and what sustains it. Northern CSOs documenting how

debt repayment burdens constrict government funding of basic education in

Mozambique or Uganda have persuaded members and committees of the U.S.

Congress and other legislative bodies to sit up and take notice. By bringing

representatives of Southern CSOs to talk to World Bank governors, Northern

CSOs shrink the distance between statistics and conscience, providing a face

and a story and bearing witness to the human costs of heavy indebtedness that

are missing from official reports. The credibility of the Northern CSO derives

from its relationship with Southern partners. The need for a new global policy

agenda was not dreamed up in an office building in Europe or the United

States. It arose in response to the very real damage being done to the people

with whom Oxfam works in the field. This agenda is not intended to replace

the economic development efforts of our partners but to remove institutional

barriers blocking their way. Inputs from leaders of partner organizations

around the world not only help us identify the barriers but also help us keep

our work in perspective. Although debt forgiveness and rules changes that

further economic and social rights are important, they say, development work

in the field begins with sound small enterprise, credit, or training programs

that help the poor keep their heads above water. Once they begin to do that,

the structural issues holding them down become apparent.

Credibility with the World Bank and those who make the rules, however,