Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Peer Training To Facilitate Social Interaction For

Uploaded by

Gloria AGOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Peer Training To Facilitate Social Interaction For

Uploaded by

Gloria AGCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/279594533

Peer Training to Facilitate Social Interaction for Elementary Students With

Autism and Their Peers

Article in Exceptional Children · December 2002

DOI: 10.1177/001440290206800202

CITATIONS READS

117 3,010

9 authors, including:

Debra Kamps

University of Kansas

78 PUBLICATIONS 3,273 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Teacher-as-coach to increase paraprofessionals fidelity of implementation of EBP View project

Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports (PBIS) View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Debra Kamps on 14 January 2015.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Exceptional Children

Vol. 68, No. 2, pp. 173-187.

©2002 Council for Exceptional Children.

Peer Training to Facilitate

Social Interaction for

Elementary Students With

Autism and Their Peers

Debra Kamps

Juniper Gardens Children’s Project

JESSICA ROYER

Partners in Behavioral Milestones, Inc.

ERIN DUGAN

Olathe Public Schools

TAMMY KRAVITS

Partners in Behavioral Milestones, Inc.

ADRIANA GONZALEZ-LOPEZ

Melmark School

JORGE GARCIA

Quality Improvement Center

for Disabilities

KATIE CARNAZZO

Kentucky Autism Training Centre

LESLIE MORRISON

Behavioral Analyst

LINDA GARRISON KANE

Southwest Missouri State

University

ABSTRACT:There is increasing evidence that peer-mediated interventions for students with autism are

effective in increasing participation in natural settings. Still unknown are the contributions peers make

to the generalization of social behaviors. Results from two investigations of this issue are reported. In

Study 1, social interaction with peers increased during interventions compared to controls; however, stu-

dents in cooperative learning control groups showed higher levels of generalization than those in social

groups. In Study 2, videotaped probes of 34 students indicated greater generalization of skills from

groups with trained peers, and less from groups with untrained and stranger peers. Implications are dis-

cussed regarding the value of ongoing peer training and structured groups to establish relationships and

generalization of skills over time.

Exceptional Children 173

ational trends indicate an in- These studies employed strategies targeting pri-

N crease in the number of chil-

dren identified as having

autism spectrum disorders

(Autism Society of America,

1999). Diagnostic criteria for Autistic Disorder

include qualitative impairment in social interac-

tion and communication, a failure to develop

peer relationships, and use of nonfunctional ritu-

marily the behavior of children with autism par-

ticipating with peers. Yet to be examined,

however, is the role of peers when trained in ex-

plicit interaction strategies with children with

autism during and after specific treatment, and

generalization of skills for target and peer partici-

pants to nontraining settings and with novel

students.

als and routines (DSM-IV, 1994). The challenges The current studies investigated the role of

of this growing population have promoted an in- peer training embedded within interventions to

creased focus by educators and families on issues maximize participation for students with autism

related to effective instruction and appropriate and the social benefits for all participants. Study

social and behavioral supports for students with 1 was an initial investigation of peer training

autism within school and community settings. within the contexts of social skills and coopera-

Research-validated, effective educational pro- tive learning groups in one school setting with a

gramming has been forthcoming with a consen- small number of students with autism. Study 2

sus for (a) early and intensive one-to-one replicated and refined these procedures with 34

language intervention (e.g., Lovaas, 1987); (b) students with autism and their peer groups across

the use of small groups, peers, and individualized multiple school districts and multiple school

instruction in functional and academic skills years. Maintenance and skill generalization across

(e.g., Gessler Werts, Caldwell, & Wolery, 1996; participants (Stokes & Osnes, 1988) in both

Kamps et al., 1995, 1997); and (c) inclusive edu- studies were measured via videotaped social be-

cation with accommodations and supports for havior probes (Haring, Breen, Pitts-Conway, Lee,

students progressing in the academic curriculum & Gaylord-Ross, 1987).

(e.g., Koegel, Harrower, & Koegel, 1999).

A key to accommodating students with

autism in public school settings is the provision STUDY 1

of social and behavioral programming to develop

This study examined the effects and generaliza-

meaningful participation with nondisabled peers

tion of three conditions: (a) social skills, (b) coop-

(e.g., Koegel, Koegel, & Dunlap, 1996). The pre-

erative learning, and (c) control groups in which

sent investigations are part of a series of studies

forms of peer training were embedded within the

by the authors designed to investigate the benefits

intervention. The overall design was a single sub-

of peer mediation and social skills interventions

ject reversal design (Barlow & Herson, 1984) in-

for students with autism and other developmental

cluding a no treatment baseline and social skills

disabilities. Prior reports provided empirical evi-

or cooperative learning groups intervention. Fall

dence supporting (a) peer tutoring and coopera- and spring social interaction behavior probes

tive groups (Kamps, Barbetta, Leonard, & (videotaped sessions) were used to monitor main-

Delquadri, 1994); (b) social skills groups (Kamps tenance and generalization effects to nontraining

et al., 1992); and (c) peer networks with acade- settings. The primary analysis of dependent vari-

mic and social components (Kamps et al., 1997). ables (frequency, mean length, and duration of

interactions) indicated that students changed

A key to accommodating students with with increased interaction levels during interven-

tion conditions (see Dugan et al., 1995). In a sec-

autism in public school settings is the pro-

ondary analysis, generalization effects were

vision of social and behavioral program- examined beyond the intervention settings. Three

ming to develop meaningful participation peer groups were available for this analysis of gen-

with nondisabled peers. eralization: (a) those who participated in coopera-

tive learning groups with students with autism,

174 Winter 2002

(b) those who participated in social skills groups was frequently echolalic when verbalizing. Her

with students with autism, and (c) a group of score was 71 on the ABC rating scale. Tony, a 9-

peers who were familiar with the students with year-old male, was described as having lower

autism but had not received training. After estab- functioning abilities. Language consisted of slowly

lishing the initial effects of training, research spoken, single-word utterances, with frequent

questions addressing generalization were echolalia and difficulty with receptive language.

identified: He appeared shy and withdrawn in social situa-

tions with few initiations. Ann and Matt partici-

• Are differences observed between time en-

pated in cooperative learning; Roberto and Carla

gaged in social interaction for peers versus stu-

participated in social skills; and Tony participated

dents with autism during intervention versus

in mainstream art. Ann, Roberto, and Tony were

generalization situation probes?

included in the social behavior generalization

• Are differences noted during generalization

probe component of the study.

probes between time engaged in social interac-

All students attended an elementary school

tion by students without autism across peer

located in a low to middle socioeconomic status

group conditions?

(SES) urban neighborhood (80% free or reduced

• Are differences noted during generalization

lunches), and 70% of the students were from mi-

probes between time engaged in social interac-

nority groups. Seven males and 8 females in

tion for students with autism across peer group

fourth grade (9 to 10 years old) participated in

conditions?

cooperative learning groups with Ann and Matt.

• Are differences noted related to contextual ef-

Seventeen third grade peers (11 males and 5 fe-

fects (peer selection of activities) from pre- to

males), aged 8 to 9 years old, participated in so-

postgeneralization probes?

cial skills groups with Roberto and Carla. Ten

males and 9 females in fourth grade participated

P A R T I C I PA N T S AND SETTINGS

as the control group. These 9- to 10-year-olds

Participants included 5 students with autism and were familiar with students with autism, with 6

51 general education peers. Ann, a 10-year- old students having participated in prior social

female with autism, was identified by her teachers groups with Roberto. During the school year in

as functioning in the moderate level. Ann used which the study was conducted, this control

short sentences to communicate needs to adults, group did not participate in training or scheduled

but had problems with echolalia and pronoun re- social groups; however, Tony was mainstreamed

versals. Initiations to peers in integrated settings in their weekly art classes.

(e.g., recess) were limited. Her teachers gave her a

E X P E R I M E N TA L P R O C E D U R E S

score of 41 on the Autism Behavior Checklist

(ABC; Krug, Arick, & Almond, 1980). Matt, a Peer training was embedded in the intervention

10-year-old male, was described as high function- and consisted of skills necessary for successful

ing. He used sentences to communicate but was participation in the specified setting. For coopera-

observed to be quiet in peer groups with few ini- tive learning groups, peers were trained to tutor

tiations. Roberto, a 9-year-old male, was de- partners in vocabulary and facts from their social

scribed by teachers as lower functioning, with studies curriculum and to complete a team activ-

limited, two- to three-word communication ity. Procedures were adapted from those outlined

skills, echolalia, and pronoun reversals. He in a tutoring manual (i.e., Greenwood,

showed few initiations to peers and appeared Delquadri, & Carta, 1997). In addition, students

withdrawn and quiet in social settings and with were taught responsibilities for group roles (John-

novel adults. His score was 48 on the ABC. son & Johnson, 1986) and social skills for work-

Carla, 9 years old, was described as lower func- ing in groups based on a published curriculum

tioning with challenging behaviors (e.g., repeated (Vernon, Schumaker, & Deshler, 1993). Ann and

noises, difficulties with changes in routines, non- Matt participated in training and cooperative

compliance). Carla could use two- to three-word learning groups three to four times per week in

phrases to communicate needs and choices, but the fourth-grade classroom. Experimental condi-

Exceptional Children 175

tions included (a) 2 weeks of baseline, (b) 4 weeks spring (n = 153) to measure maintenance and

of cooperative groups, (c) 2 weeks of baseline, and generalization of skills. This procedure was mod-

(d) 4 weeks of cooperative groups (see Dugan et eled after the social behavior probes in Haring et

al., 1995, for details). al. (1987). In that study, probes were collected to

Peer training for the social skills groups fo- note generalization of social behaviors for stu-

cused on initiating and responding to peers, co- dents with disabilities and peers who had partici-

operating, and engaging in positive interactions pated in special friends or tutoring experiences, as

during play activities as outlined by the curricu- well as with nonparticipants. Procedures in the

lum (Walker, Hops, & Greenwood, 1988). The current study were similar in that the probes were

10-min teaching format consisted of introduction in a nontraining setting and standardized across

and modeling of a skill by the experimenter, indi- probes and participants. One target student with

vidual and choral responding, student-to-student autism and three nondisabled peers participated

practice of the skill, and review. Students then in each probe. All peers participated in three

participated in 10 to 15 min of play/free time probes each, one with each student, Ann,

during which they received points for appropriate Roberto, and Tony. Sessions were conducted in

use of social skills. Roberto, Carla, and 17 peers the special education classroom. Students were

participated in training and social skills groups told they had 15 min of free time and they could

three to four times per week in the third-grade use any of the materials, academic (sorting ob-

classroom. Experimental conditions included (a) jects, pictures, flash cards) or social (balls, books,

2 weeks of baseline, (b) 4 weeks of social skills music cassettes, magazines). Observers sat to the

groups, (c) 2 weeks of baseline, and (d) 4 weeks of side to collect interaction data and to note the ac-

social skills groups. Pre-and postsocial behavior tivity (tutorial, social, or noninteractive).

probes to note generalization for both groups Reliability. Reliability for generalization

were conducted in the fall and spring. See Figure probes data was collected for 21% of pre- and

1 for descriptions of procedures. 27% of postsessions. The average percentage

MEASUREMENT agreement for frequency of interactions was 90%

(R = 50%-100%), and 95% (R = 33%-100%), re-

Dependent measures included (a) the frequency spectively for pre and post; 87% (R = 45%-

of interactions, mean length of interactions, and 100%) and 92% (R = 38%-100%) for mean

total duration of social interaction time during 5- length; and 90% (R = 76%-100%) and 96% (R =

min probes; and (b) the frequency of initiations 62%-100%) for duration. Low agreements, a lim-

to the target students by the peers. During inter- itation, occurred during sessions with minimal in-

vention sessions and during the generalization teractions and lesser duration; however, means

probes, the Social Interaction Code (SIC; show acceptable overall agreement.

Niemeyer & McEvoy, 1989) was used to collect

the data. This is a computerized system that

records initiations, responses, and total duration R E S U LT S A N D D I S C U S S I O N

time for each interaction during the observation.

Initiations were defined as motor or vocal behav- As depicted in Table 1, both cooperative learning

ior (assisting, sharing materials, conversing), and social skills groups, each with embedded peer

clearly directed to a peer/target to evoke a re- training in critical skills, increased the amount of

sponse. Responses were defined as a reply within time engaged in social interaction for the students

3 sec, thus reflecting reciprocity (initiation-re- with autism and their peers over baseline condi-

sponse sequences). This code has been previously tions. During cooperative learning groups (upper

reported (e.g., Dugan et al., 1995; Kamps et al., panel), the students’ time engaged in interaction

1992), and updated (Tapp, Wehby, & Ellis, increased from less than 30 to 191 or more sec-

1992). onds during 5-min probes, similar to peer levels.

Social Behavior Generalization Probe Proce- These changes were also reflected in increases for

dures. A total of 306 social behavior generalization the frequency and mean length of interaction.

probes were collected in the fall (n = 153) and During social skills training (see lower panel,

176 Winter 2002

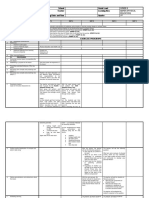

figure 1

Overview of Experimental Procedures

Social Skills Groups (Walker, et al., 1988)

Structure: 10-min scripted lessons with modeling, role-plays, and feedback

10- to 15- min free play with stickers and praise for skill use

5-min team bonus for stickers/points during free play

Starting Initiating interactions: find someone to play, use names, ask to play

Responding Looking at, turning to, and answering friends when spoken to

Keeping It Going Keeping play going, talking and asking questions, changing what you are doing

Saying Something

Nice–Praising Saying what you like, saying what is good, saying what you see

Cooperating–

Getting Along Helping people, sharing materials, taking turns, problem-solving

Cooperative Learning Groups (Dugan et al., 1995)

Structure: 10-min teacher introduction of new material

10-min peer tutoring in vocabulary words

8-min peer tutoring in social studies facts

5-min team activity

5-min team bonus for SCORE points

Peer tutoring using States and Regions Students in groups of four, tutoring in dyads within

(Bacon, 1991) groups (5 min each person) for vocabulary

words/comprehension facts with definitions and

sample facts on flash cards

Team activity Students worked together (four) to complete work-

sheet, answer board questions, etc.

Student roles Materials manager, recorder (write answers),

checker (complete checklist on group’s coopera-

tion), and organizer (leader)

SCORE skills Cooperation skills taught during first week of

(Vernon et al., 1993) groups and reviewed each session with desk charts

for points for skill use. Skills included sharing

ideas, correcting others’ work, offering praise, re-

acting calmly, encouraging and helping others.

Table 1), the students with autism increased their time in interaction from pre to post. The control

time engaged in interaction with peers from a group peers increased their interaction time by

range of 7–56 to 152–262, also similar to peers in about 50% in comparison. They were somewhat

this group who improved over baseline. Changes higher than either intervention group on the

in frequency of interactions also occurred. preintervention probes. Repeated measures analy-

Generalization effects (social behavior sis of variance tests indicated significance for the

probes) showed that the cooperative learning group x time interaction for frequency and dura-

group peers increased their interactions to more tion of time engaged in interaction. Planned con-

than three times the level of baseline (see Figure trasts indicated a significance between the peer

2). Peers in the social skills program doubled their groups (Wilks’ lambda, F = 4.958, p = .000). Dif-

Exceptional Children 177

Ta b l e 1

Social Interaction Behaviors During Cooperative Learning and Social Skills Groups Intervention

Sessions: 5-min Samples–Study 1

Cooperative Learning Group Means

Social Ann Matt a Peers

Interaction B I B I B I B I B I B I

Frequency 0.3 2.1 0 1.6 1 3 2 3 1 4 1 3

Duration 1 191 0 273 28 219 17 210 16 197 42 185

M Length 1 93 0 216 10 84 13 76 6 81 21 110

Social Skills Groups

Social Roberto Carla a Peers

Interaction

B I B I B I B I B I B I

Frequency 1 2 0.3 2 0.2 4 2 3 3 4 3 3

Duration 7 173 32 262 12 152 56 197 140 216 137 217

M Length 6 79 16 162 5 56 21 74 94 85 66 142

Note: Frequency = total number of interactions; duration is in number of seconds with 300 possible in 5-minute probes; M

length = duration divided by frequency; B = Baseline; I= Intervention.

a Students who participated in intervention, but not in generalization probes.

ferences also were noted favoring the cooperative probe sessions. During the presessions, 29% were

learning over the social skill group and control tutorial in nature with students selecting acade-

peers at posttest for frequency (p < .05), duration mic materials, 27% were social, and no materials

(p < .05), and initiations of social interaction (p < were selected for 43%. During the postsessions,

.05). tutorial and social contexts both increased to

All three target students improved their 39%, and sessions with no materials decreased to

time engaged in social interaction from the fall to 21%. The data also indicated that durations

spring (see Figure 2, pre/post means by peer matched to contextual variables increased for

groups). Ann’s means increased from 86.2 to both groups from pre- to postsessions (121 to 220

199.5; Roberto’s from 64.5 to 148.4; and Tony’s for sessions reflecting tutorial choices, 140 to 178

from 76.4 to 126.9. Ann’s time engaged in inter- for social choices, less than 5 seconds of interac-

action during generalization probes was similar to tions when no materials were chosen). These data

her interaction levels during intervention, but support the validity of peer training within tutor-

slightly lowered levels were noted for Roberto (see ial and social contexts.

Table 1). These data reflect stronger changes (i.e.,

S U M M A RY OF STUDY 1 FINDINGS

more generalization) for target students in the in-

tervention programs than for Tony who did not Key findings were: (a) intervention components,

receive intervention in that school year. Further including peer training, increased social interac-

generalization based on peer groups was evident tion between students with autism and their peers

(see Figure 3), that is, Ann demonstrated more across academic and social contexts, and (b) peer

generalization during the probe with her inter- mediation programs facilitated generalization of

vention peers (cooperative groups), and Roberto interaction skills to nontraining settings as evi-

during the probe with his social skills peers. denced in the social behavior probes in the spring.

Contextual generalization effects were also The fact that the control group peers also in-

noted when looking at student choices during creased interaction skills may have occurred be-

178 Winter 2002

Figure 2

Duration in Seconds of Interaction Time for Peers by Intervention Groups–Study 1

cause the classes for students with autism had a single intervention would show increased bene-

been in the school for 4 years, and thus increases fits. Thus, an important goal in this study was to

were a function of familiarity. Several hypotheses examine the effects of multiple peer groups for

also exist as to why the cooperative learning group each participant, sustained over time. Peer groups

participants evidenced more generalization: (a) included social skills groups, tutoring/cooperative

social skills training may not be as robust, (b) co- learning groups, and lunch and recess buddy pro-

operative learning groups in this study included grams. As in Study 1, videotaped social behavior

social skills instruction, and thus were a multi- probes to note generalization, were conducted in

component intervention (academic and social in the fall and spring, and again 2 years later. Video-

nature), and (c) the tutoring nature of the cooper- taped probes included peers from three groups:

ative groups may have provided more momentum (a) students trained in interaction skills (i.e., in-

because of its repeated, consistent interactions, tervention similar to those in Study 1); (b) peers

whereas social skills groups were “free time,” al- familiar with the target students but untrained

lowing members to exhibit more variance in in- (similar to the control group in Study 1); and (c)

teractions. Two limitations to the study may have students who were strangers to the participants

also contributed: The cooperative learning peers with autism. Research questions identified were:

were a year older (fourth-graders vs. third-

• Is there maintenance over time (school years)

graders), and 6 peers had participated in a prior

and generalization of social interaction time

social skills intervention, perhaps indicating an

from natural settings to generalization probes?

additive effect of more training with students

• Are there differences across peer group condi-

with autism.

tions?

• How do videotape probe data compare to data

collected in intervention settings?

STUDY 2

Based on Study 1 results, Study 2 examined the

maintenance and generalization effects of peer-in-

clusive social groups for 34 students with autism.

Results from Study 1 suggested that both acade- Intervention components, including peer

mic (cooperative learning) and social groups with training, increased social interaction be-

peers showed better generalization effects than did

familiar peers with no intervention. It was further tween students with autism and their

hypothesized that students with autism who par- peers across academic and social contexts.

ticipated in both types of peer groups rather than

Exceptional Children 179

Figure 3

Seconds of Interaction Time for Students with Autism by Peer Group–Study 1

• Are there differences in interaction time be- final years. Peer programs averaged 2.1 in Year 1

tween students with autism and peers follow- (total of 62) and 2.3 in Year 3 (total of 79).

ing intervention?

Peer Groups. Approximately 130 peers par-

ticipated in videotaped probes in the initial year

P A R T I C I PA N T S AND SETTINGS

and 120 during the final probe year. About 60%

Thirty-four students with autism participated in were female and 40% were male. Peers were the

the study, 24 males and 10 females (see Table 2). same age or within a 1-year difference of the stu-

Students ranged in age from 7 to 14 years old dents with autism. Trained peers were defined as

across the 3-year period, and all attended public (a) having participated in at least one peer media-

school programs in six school districts in the Mid- tion program with the target student, (b) having

west. Twenty-six (76%) of the students had at received training in prompting and reinforcing

least minimal verbal skills (2- to 3- word requests) social interaction via the program, and (c) cur-

and 8 were nonverbal (i.e., mute, single-word ap- rently in the target student’s participating general

proximations, gestural/augmentative communica- education classroom when possible. Familiar peers

tion). Mean Childhood Autism Rating Scale were also in the same general education class, but

scores were 32 (R = 17-46) in Year 1 and 36 in had not participated in a peer mediation pro-

Year 3. ABC scores averaged 50, indicating a gram, were typically not assigned as a class buddy,

range of autistic behaviors (R = 8 to 113 in Year and did not have a negative history with the stu-

3). Over half of the students were served in gen- dent with autism according to the teacher.

eral education settings 70% of the time, with Stranger peers were not enrolled in the target stu-

paraprofessional support, during the initial and dent’s general education class, nor were they ob-

180 Winter 2002

served to be in groups with the student during and all were enrolled in peer mediation programs

common times (e.g., recess) or considered to be a including 20 games/play groups, 18 peer net-

neighborhood friend. works, and 25 peer-tutoring groups (N = 63 pro-

grams). Twenty-two (68%) were in multiple

P E E R M E D I AT I O N P R O G R A M

programs; 56% were in both academic and social

CHARACTERISTICS

groups. A summary of effects for 20 programs

Students received a variety of peer mediation pro- (Kamps et al., 1998) noted that the time engaged

grams during the 2 school years in which general- in interaction during social skills play groups ses-

ization data were collected. Peer mediation sions averaged 140 to 190 during 300 s probes (5-

programs consisted of the following: (a) social min), with reciprocal interaction occurring

skills/games/play groups that included three to five 34–63% of session intervals. Time engaged in in-

peers and the target child with age appropriate teraction during academic/tutoring intervention

toys and activities (cars, puzzles, Trouble®, Con- sessions average 190 to 200+ s during 5-min

nect 4®, card games); (b) lunch buddy groups dur- probes.

ing which three to five peers and the target

G E N E R A L I Z AT I O N M E A S U R E M E N T

student took turns commenting on pictures/top-

ics, and asking/answering questions of each other; Four behaviors (dependent measures) were as-

(c) recess buddy programs during which peers and sessed from the videotape probes to monitor stu-

the target students selected an activity, practiced dents’ social performance. The time engaged in

interactions in advance of recess and then played social interaction (duration) was recorded using an

together during at least 10 min of recess; and (d) update of the Social Interaction Code from Study

tutoring activities during which a peer would tutor 1, the MOOSES (Multiple Option Observation

the student in language, reading, or math (higher System for Experimental Studies; Tapp et al.,

functioning students served in reciprocal tutoring 1992). Prior reports describe the use of the

arrangements within small tutoring groups or MOOSES code in various forms (e.g., Kamps et

classwide applications). Using social skills curric- al., 1997). Duration of interactions was recorded

ula (Hops, Greenwood, and Walker, 1997; Odom for 10 min from the videotaped probes (total time

& McConnell, 1997) and tutoring manuals = 600 s), with the same start time noted as for the

(Greenwood et al., 1997), peers and target stu- interval coding. In order to note additional stu-

dents received direct instruction in the use of dent behaviors in Study 2, a 10-s whole interval

skills within the context of the activity. Skill areas coding system was used to code reciprocal interac-

focused on interaction behaviors including look- tion, appropriate toy use, and on topic/off topic

ing, using names, play organizers, asking/answer- verbalizations. Reciprocal interactions were defined

ing questions (academic or social), commenting, as the target student taking a turn, giving or re-

sharing materials, taking turns, demonstrating ceiving materials, initiating an interaction, or re-

(imitating) play behaviors, and helping. Prior re- sponding to a peer (verbal, physical responses).

ports describe interventions in more detail and Toy play included manipulating materials and

experimental analysis of effects on student out- pieces appropriately, and holding materials while

comes (e.g., Kamps et al., 1992; Kamps et al., waiting for a turn. On topic verbalizations in-

1994; Kamps et al., 1997). cluded comments, questions, and phrases used

Implementation Levels and Effects. Thirty of appropriately to initiate or respond to peers or to

the students during the initial year were enrolled describe activity (e.g., “I have 4.” “It’s your turn.”

in peer mediation programs including 22 “Okay.”). Interval code observations from video-

games/play groups, 18 peer networks (i.e., lunch tapes were recorded for 10-min probes, and sum-

or recess programs, special activities), and 8 peer- marized by percentage of intervals for occurrence.

tutoring groups (N = 48 programs). Seventeen of Reliability. Reliability for MOOSES files

the students (50%) were involved in multiple was collected for 5% of the files and for approxi-

groups with 9 (28%) participating in both acade- mately 30% of the interval data probes. Average

mic and social peer programs. During the subse- percentage agreement across social behaviors was

quent probe year, 34 students were monitored, 92% for the duration of interactions, 90% for

Exceptional Children 181

Ta b l e 2

Student Characteristics–Study 2

Students Mean Age Mean CARS Mean ABC Peer Programs Integration

Initial year Initial year Initial year Initial year Time %

21 males 110 months 32 50 2.1 60%

9 females 75-148 17-46 5-127 total = 62 0-100%

Students Mean Age Mean CARS Mean ABC Peer Programs Integration

Final year Final year Final year Final year Time %

24 males 138 months 36 51 2.3 55%

10 females 94-172 19-52 8-113 total = 79 10-100%

Note: CARS = Childhood Autism Rating Scale; ABC = Autism Behavior Checklist

reciprocal interaction, 83% for on topic language, 1987); and (b) generalization of skills for peers or

and 93% for toy play. Reliability for peer data was students with disabilities to novel persons (e.g.,

collected for 10% of the interval and MOOSES Pierce & Schreibman, 1997; Taylor & Harris,

files, with mean percentage agreements at 90% 1995).

for the duration of interaction, 83% for reciprocal The schedule for videotape probes con-

interaction, 79% for on topic language, and 96% sisted of fall and spring sessions in the initial year

for toy play. with familiar and stranger peers observed with 30

Social Behavior Generalization Procedures. students with autism for both probes, and trained

Social behavior generalization probes consisted of students observed only for the spring probes (N =

approximately 15-min sessions in which a student 134 probes). Videotape probes were again con-

with autism and four peers were seated at a table ducted in the spring 2 years later (N = 65) with

with toys and games. Only play materials were trained and familiar peers and 34 students with

used in Study 2 in order to determine generaliza- autism. The total number of probes by peer group

tion of social skills and interaction. Academic or was 61 with trained, 88 with familiar, and 50

tutorial type materials were eliminated to reduce with stranger peers. Probes were also collected for

the possibility of inflated interaction levels due to 30 peers in the initial year (fall and spring, N = 60

tutoring structures. Kindergarten through second- probes), to provide a normative comparison for

grade level materials included memory games, the social behaviors.

Floam®, Trouble® or Don’t Break the Ice®; cars, Data Analysis. Visual inspection of the

blocks, and puppets. Materials for third through means across behaviors and time were conducted

seventh grades included Uno®, cards, Gak®, for a subset of the students who were available

Connect 4®, Pogs®, Jenga®, and magazines. In- across repeated probes/years with each peer group.

structions to groups were: “Here are some toys Twenty students were available for both probes

and games you can play with for about 10 min- with the trained peers; 24 were available for all

utes. Please stay at the table when you play.” No three probes with the familiar peers. Twenty-three

prompts or reinforcement were provided. Similar were available for both probes with stranger peers.

to Study 1, and as reported in other investigations An analysis of variance was conducted with the

with generalization probes, these assessments were entire sample (N = 34 students with autism, 199

designed to measure the following conditions: (a) videotape probes) by condition (familiar, trained,

maintenance and generalization of social commu- stranger peer groups).

nication skills with the trained peers and teaching

adult to nontraining settings (e.g., Haring et al.,

182 Winter 2002

R E S U LT S A N D D I S C U S S I O N

Generalization data are presented in Table 3 for Differences over time confirmed the hy-

the students with autism over time and across pothesis that students who received inter-

groups (probes with trained, familiar, and stranger vention over multiple years (i.e.,

peer groups). Three social behaviors showed in- increased opportunities to participate in

creases over time for students with trained peers:

The duration of interaction (time engaged) and peer mediation programs) would also

reciprocal interaction showed notable differences, show more generalization.

with smaller changes for on topic language. In the

three probes with familiar peers, the duration of

slightly higher for target students with the trained

interactions and reciprocal interaction again

peers (26%) than with familiar and stranger peers

showed noteworthy increases over time, but no

(21%, 19%) and less than verbalizations by peers,

changes were noted for language. All behaviors

which averaged 51%-52% of intervals. These

occurred with less frequency with stranger peers,

data, however, included nonverbal students with

with decreases in the duration of time engaged in

only minimal ability to make word approxima-

social interaction, and slight increases in recipro-

tions. When analyzing data for the verbal stu-

cal interaction. Differences over time confirmed

dents (n = 24), on topic language occurred during

the hypothesis that students who received inter-

36% of the intervals with trained peers during the

vention over multiple years (i.e., increased oppor-

final probe. Toy play was high (66% to 74%) for

tunities to participate in peer mediation

target students with all peer groups and slightly

programs) would also show more generalization.

less than peers (85%).

Appropriate use and play with toys (see Table 3)

remained stable and appropriate regardless of the

peer groups (means ranged from 58% to 78%).

GENERAL DISCUSSION

Analysis of variance of data aggregated

across all probes (column 4, Table 3) showed sig- In general, findings for students with autism

nificantly different effects by peer group condi- tracked over a 3-year period with participation in

tion for the durations of social interaction time multiple peer mediation interventions indicated

(Wilks’ lambda, F = 7.718, p = .001). Pairwise improved social interaction skills with nondis-

comparisons showed higher duration times for abled elementary school students. The level of in-

the students with autism and trained peers (393 teraction also matched those of peers sampled.

s), than with the familiar peers (301 s; p < .05) Similar to other reports (e.g., Ostrosky & Kaiser,

and with stranger peers (246 s; p < .05). The du- 1995), significantly more social behaviors oc-

ration of interactions was also equal to peer levels curred with peers who were trained via participa-

(373 to 419 s). Probe data with trained peers were tion in social/play groups, peer networks during

similar or slightly lower than durations during in- lunch and recess, and tutoring programs, than for

tervention sessions (range of 60% to 80% social control group peers. Peer training formats that

engagement during 5-min samples, a comparable have included the use of modeling, prompting,

range for 10-min probes of 360 to 480 s; e.g., and reinforcement strategies within the context of

Kamps et al., 1992, 1998), again clearly indicat- activities, and those that included multiple peers

ing generalization of interaction skills for students over time, have shown notable changes in interac-

with and without autism. Significantly more reci- tion skills for students with autism (e.g., Kamps

procal interaction (Wilks’ lambda, F = 9.888, p < et al., 1997; Pierce & Schreibman, 1997; Sasso,

.000) also occurred with students with autism and Hughes, Swanson, & Novak, 1987). These out-

the trained peers (64% of intervals) than with the comes suggest generalization of social skills by

familiar peers (39% of intervals; p < .05) or with both students with autism and peers—a trend

the stranger peers (29%; p < .05). These levels where social situations become more naturally re-

were equal to peers who averaged interactions in inforcing for students with autism, with an im-

55%-60% of intervals. On topic language was only provement in general responsiveness on the part

Exceptional Children 183

Ta b l e 3

Means for Social Interaction Behaviors for Students with Autism and Trained, Familiar, and Stranger Peers

in Study 2

Duration of Social Interaction Time–Seconds in 10-min Probes

Time 1 Time 2 Time 3 All Data

With Trained Peers --- 355 440 393

With Familiar Peers 271 267 378 301

With Stranger Peers 261 232 --- 246

Typical Peers 373 419 --- ---

Reciprocal Interaction –% of Intervals

Time 1 Time 2 Time 3 All Data

With Trained Peers --- 48 69 64

With Familiar Peers 28 37 53 39

With Stranger Peers 25 33 --- 29

Typical Peers 55 60 --- ---

On Topic Language–% of Intervals

Time 1 Time 2 Time 3 All Data

With Trained Peers --- 25 35 26

With Familiar Peers 23 19 23 21

With Stranger Peers 23 20 --- 19

Typical Peers 51 52 --- ---

Note: Times 1-3 data = means with trained peers and 20 students with autism; means with familiar peers and 24 students

with autism; means with stranger peers and 23 students with autism. All data column includes means for 34 students with

autism with data across 3 years (N = 199 probes).

of peers to students with disabilities. Interview less frequently than with trained or familiar peers.

data from over 100 peers also noted a strong fa- These findings suggest generalization of skills by

vorable impression by peers of their participation

(Kamps et al., 1998). Over 90% indicated an in-

terest in continued programs with their classmates These outcomes suggest generalization of

with autism. social skills by both students with autism

A second positive outcome was that consis-

and peers—a trend where social situations

tent contact with peers, or familiarity via inclusive

classes in the absence of peer training also general- become more naturally reinforcing for stu-

izes to social behaviors, though less interaction dents with autism, with an improvement

occurs than with structured peer mediation. So- in general responsiveness on the part of

cial interaction also occurred among the students

peers to students with disabilities.

with autism and stranger peers, although again

184 Winter 2002

grams that include academic and social media-

Consistent contact with peers, or famil- tion, peer groups across multiple settings, and re-

iarity via inclusive classes in the absence cruitment of novel peers to generalize effects.

of peer training, also generalizes to social Second, peer mediation needs to incorporate the

behaviors. use of effective instructional strategies such as

modeling and reinforcement (Gonzalez-Lopez &

students with autism, trained peers modeling in- Kamps, 1997), visual cuing and scripts (Krantz &

teraction in natural settings for novel peers, or an McClannahan, 1998), and self-management

interest by many elementary-aged children to en- techniques (Koegel, Harrower, & Koegel, 1999)

gage with students with disabilities in social situa- to enhance student acquisition of social skills. It is

tions when the expectation to do so is stated and especially important to encourage and reinforce

reinforced by teachers and peers (Sasso et al., peers for interactions with peers with disabilities.

1987). A third recommendation for the success of social

A limitation to the study is that social interventions is incorporation of generalization

probes were not also conducted in other settings tactics including (a) functional mediators (i.e.,

such as recess and lunch. In many cases, however, peers); (b) natural settings for intervention (re-

the social settings served as the intervention time cess, play groups); (c) natural communities of re-

with peers, in other cases time constraints prohib- inforcement for peers and target students (play,

ited additional data collection. A second limita- preferred toys, games); (d) diverse and loose train-

tion is that generalized language use for verbal ing allowing for variability as occurs in applied

students with autism with trained peers was lower settings; and (e) stimuli common to multiple set-

than for typical peers (36% compared to 51%). tings (classmates, activities; Stokes & Osnes,

Several factors could have accounted for this dif- 1988). Final recommendations include continued

ference, including the size of the groups (3 to 4 research incorporating (a) additional attention

peers and 1 student with autism), and the limited and monitoring of communication expansions

language skills for many participants. Additional within peer contexts (Pierce & Schreibman,

research is needed in this area. Recommendations 1997) and (b) intervention for longer time spans

include (a) training for students with autism in and with consistent implementation across school

the use of language in social settings, perhaps in

and family contexts to improve generalization and

dyads with one peer initially, and (b) training

durability of effects (Strain & Schwartz, 2001).

peers to prompt and reinforce language, and to

use specific strategies such as time delay and inci-

dental teaching.

REFERENCES

Autism Society of America. (1999). Advocate, The

I M P L I C AT I O N S F O R P R A C T I C E Newsletter of the Autism Society of America, 32, 3-4.

Findings from these and related studies (e.g., Bacon, P. (1991). States and Regions, Orlando, FL: Har-

Kamps et al., 1997; Pierce & Schreibman, 1997) court Brace Company.

suggest the viability of peer mediation programs Barlow, D., & Hersen, M. (1984). Single case experi-

to support elementary school programs for stu- mental designs: Strategies for studying behavior change.

dents with autism. Recommendations for practi- New York: Pergamon Press. *

tioners that appear to be most beneficial for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

improved social outcomes include the use of pro- (4th Ed.) (1994). Washington, DC: American Psychi-

atric Association.

Dugan, E., Kamps, D., Leonard, B., Watkins, N.,

It is especially important to encourage

Rheinberger, A., & Stackhaus, J. (1995). Effects of co-

and reinforce peers for interactions with operative learning groups to facilitate integration of

peers with disabilities. students with autism in a fourth grade social studies

class. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 28, 175-188.

Exceptional Children 185

Gessler Werts, M., Caldwell, N., & Wolery, M. (1996). Koegel, L. K., Harrower, J. K., & Koegel, R. L. (1999).

Peer modeling of response chains: Observational learn- Support for children with developmental disabilities in

ing by students with disabilities. Journal of Applied Be- full inclusion classrooms through self-management.

havior Analysis, 29, 53-66. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 1(1), 26-34.

Gonzalez-Lopez, A., & Kamps, D. (1997). Social skills Krantz, P., & McClannahan, L. (1998). Social interac-

training to increase social interaction between children tion skills for children with autism: A script-fading pro-

with autism and their peers. Focus on Autism and Other cedure for beginning readers. Journal of Applied

Developmental Disabilities, 12, 2-14. Behavior Analysis, 31, 191-202.

Greenwood, C. R., Delquadri, J., & Carta, J. (1997). Krug, D., Arick, J., & Almond, P. (1980). Autism

Together we can! ClassWide peer tutoring to improve basic screening instrument for education planning. Portland,

academic skills. Longmont, CO: Sopris West. * OR: ASIEP Education. *

Haring, T., Breen, C., Pitts-Conway, V., Lee, M., & Lovaas, I. (1987). Behavioral treatment and normal ed-

Gaylord-Ross, R. (1987). Adolescent peer tutoring and ucational and intellectual functioning in young autistic

special friend experiences. Journal of the Association for children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology,

Persons with Severe Handicaps, 12, 280-286. 55, 3-9.

Hops, H., Greenwood, C. R., & Walker, H. (1997). Niemeyer, J., & McEvoy, M. (1989). Observational as-

Social skills tutoring and games: A program to teach social sessment of reciprocal social interactions: Social interaction

skills to primary grade students. Delray Beach, FL: Edu- code. Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, and the

cational Achievement Systems. * University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

Johnson, D., & Johnson, R. (1986). Learning together Odom, S., & McConnell, S. (1997). Play time/Social

and alone (2nd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-

time: Organizing your classroom to build interaction

Hall.

skills. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota.*

Kamps, D., Barbetta, P., Leonard, B. R., & Delquadri,

Ostrosky, M., & Kaiser, A. (1995). The effects of a

J. (1994). Classwide peer tutoring: An integration strat-

peer-mediated intervention on the social communica-

egy to improve reading skills and promote interactions

tive interactions between children with and without

among students with autism and regular education

special needs. Journal of Behavioral Education, 5, 151-

peers. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 27, 49-60.

171.

Kamps, D., Kravits, T., Gonzalez-Lopez, A., Kem-

Pierce, K., & Schreibman, L. (1997). Multiple peer use

merer, K., Potucek, J., & Garrison-Harrell, L. (1998).

of pivotal response training to increase social behaviors

What do the peers think? Social validity of peer-medi-

of classmates with autism: Result from trained and un-

ated programs. Education and Treatment of Children,

21(2), 107-134. trained peers. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 30,

157-160.

Kamps, D., Leonard, B., Potucek, J., & Garrison-Har-

rell, L. (1995). Cooperative learning groups: An inte- Sasso, G., Hughes, G. G., Swanson, H. L., & Novak,

gration strategy to improve academic and social C. G. (1987). A comparison of peer initiation interven-

performance for students with autism and regular class- tions in promoting multiple peer initiators. Education

room peers. Behavioral Disorders, 21, 88-108. and Training in Mental Retardation, 22, 150-155.

Kamps, D., Leonard, B., Vernon, S., Dugan, E., Stokes, T. F., & Osnes, P. G. (1988). The developing

Delquadri, J., Gershon, B., Wade, L., & Folk, L. applied technology of generalization and maintenance.

(1992). Teaching social skills to students with autism to In R. Horner, G. Dunlap, & Koegel, R. (Eds.), Gener-

increase peer interactions in an integrated first-grade alization and maintenance: Life-style changes in applied

classroom. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 25, settings. Baltimore, MD: Brookes.

281-288. Strain, P., & Schwartz, I. (2001). ABA and the develop-

Kamps, D., Potucek, J., Gonzalez-Lopez, A., Kravits, ment of meaningful social relations for young children

T., & Kemmerer, K. (1997). The use of peer networks with autism. Focus on Autism and Developmental Dis-

across multiple settings to improve interaction for stu- abilities, 16, 120-128.

dents with autism. Journal of Behavioral Education, 7, Tapp, J., Wehby, J., & Ellis, D. (1992). A multiple op-

335-357. tion observation system for experimental studies—

Koegel, L., Koegel, R., & Dunlap, G. (1996). Positive MOOSES. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University.

behavioral support: Including people with difficult behav- (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 361

ior in the community. Baltimore, MD: Brookes. 372)

186 Winter 2002

Taylor, B., & Harris, S. (1995). Teaching children with

autism to seek information: Acquisition of novel infor-

mation and generalization of responding. Journal of Ap-

plied Behavior Analysis, 28, 3-14.

Vernon, S., Schumaker, J., & Deshler, D. (1993). The

SCORE Skills: Social skills for cooperative groups.

Lawrence, KS: Edge Enterprises.

Walker, H., Hops, H., & Greenwood, C. (1988). Social

skills tutoring and games: A program to teach social skills

to primary grade students. Delray Beach, FL: Educa-

tional Achievement Systems.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

DEBRA KAMPS (CEC #93), Senior Scientist, Ju-

niper Gardens Children’s Project, University of

Kansas, Kansas City. JESSICA ROYER, Senior

Behavior Analyst, Partners in Behavioral Mile-

stones, Inc., Kansas City, Missouri. ERIN

DUGAN, Assistant Director of Special Education,

Olathe Public Schools, Olathe, Kansas. TAMMY

KRAVITS, Senior Behavior Analyst, Partners in

Behavioral Milestones, Inc., Kansas City, Mis-

souri. ADRIANA GONZALEZ-LOPEZ, Assistant

Director of Education, Melmark School, Berwyn,

Pennsylvania. JORGE GARCIA, Senior Special-

ist, Quality Improvement Center for Disabilities,

University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas

City. KATIE CARNAZZO, Autism Training Co-

ordinator, Kentucky Autism Training Center,

University of Louisville. LESLIE MORRISON,

Behavioral Analyst, Columbia, Missouri. LINDA

GARRISON KANE, Associate Professor, South-

west Missouri State University, Springfield.

Manuscript received July 2000; accepted July

2001.

* To order books referenced in this journal, please

call 24 hrs/365 days: 1-800-BOOKS-NOW

(266-5766); or 1-732-728-1040; or visit them on

the Web at http://www.BooksNow.com/Excep-

tional Children.htm. Use Visa, M/C, AMEX,

Discover, or send check or money order + $4.95

S&H ($2.50 each add’l item) to: Clicksmart, 400

Morris Avenue, Long Branch, NJ 07740; 1-732-

728-1040 or FAX 1-732-728-7080.

Exceptional Children 187

View publication stats

You might also like

- Tab 19 - Visitation Observation ChecklistDocument2 pagesTab 19 - Visitation Observation ChecklistMFNo ratings yet

- Social and Behavioural Change Interventions To Strengthen Disability Inclusive Programming SummaryDocument5 pagesSocial and Behavioural Change Interventions To Strengthen Disability Inclusive Programming Summaryyhanna dima0% (1)

- Rephrasing Conditionals WishDocument3 pagesRephrasing Conditionals WishCristina CozAlv25% (4)

- Teaching Social Skills to Students with Autism to Increase Peer InteractionsDocument9 pagesTeaching Social Skills to Students with Autism to Increase Peer InteractionsAndreia SilvaNo ratings yet

- Banda Et Al. - 2010 - Impact of Training Peers and Children With Autism PDFDocument7 pagesBanda Et Al. - 2010 - Impact of Training Peers and Children With Autism PDFMuhammad Bilal ArshadNo ratings yet

- Definition,: UniversityDocument8 pagesDefinition,: UniversityAndré Luíz FerreiraNo ratings yet

- Embedded Video and Computer Based Instruction To Improvepdf HABILIDADES SOCIAISDocument14 pagesEmbedded Video and Computer Based Instruction To Improvepdf HABILIDADES SOCIAISsuwillowNo ratings yet

- Research 1 AutismDocument2 pagesResearch 1 AutismNorAzminaNadiaNo ratings yet

- Increasing The Social BehaviorDocument9 pagesIncreasing The Social BehaviorMichaella Ryan QuinnNo ratings yet

- Delano 2006Document15 pagesDelano 2006Luana TeixeiraNo ratings yet

- Social skills training increases interactions between children with autism and peersDocument13 pagesSocial skills training increases interactions between children with autism and peersSarahNo ratings yet

- Bock 2007Document8 pagesBock 2007Luana TeixeiraNo ratings yet

- IN WJTH Autism: Effects of Peer-Implemented Pivotal Response Training Karen Pierce Laura SchreibmanDocument11 pagesIN WJTH Autism: Effects of Peer-Implemented Pivotal Response Training Karen Pierce Laura SchreibmanAlexandra AddaNo ratings yet

- Ps 12104Document12 pagesPs 12104Zvonimir LiteraturaNo ratings yet

- Parent-Assisted Social Skills Training Improves Friendships in Teens with AutismDocument12 pagesParent-Assisted Social Skills Training Improves Friendships in Teens with AutismroosendyannisaNo ratings yet

- s10803 005 0014 920161018 6512 Etkigb With Cover Page v2Document13 pagess10803 005 0014 920161018 6512 Etkigb With Cover Page v2D.S.M.No ratings yet

- Chang 2013Document4 pagesChang 2013Fernando Vílchez SánchezNo ratings yet

- Scattone2006 PDFDocument13 pagesScattone2006 PDFWanessa AndradeNo ratings yet

- Improve Social Skills of Kids with Autism Using LEGODocument15 pagesImprove Social Skills of Kids with Autism Using LEGOjhebetaNo ratings yet

- SocialtalkDocument14 pagesSocialtalkIuli AnaNo ratings yet

- Radley 2014Document12 pagesRadley 2014iftene ancutaNo ratings yet

- JPSP - 2023 - 64Document14 pagesJPSP - 2023 - 64badasahirpesaj0906No ratings yet

- Bellini 2007Document11 pagesBellini 2007Wanessa AndradeNo ratings yet

- Luczynski Hanley 2013 Preventing Problem BehaviorDocument15 pagesLuczynski Hanley 2013 Preventing Problem BehaviorAlexandra AddaNo ratings yet

- Promoting Peer Interaction For Preschool Children With Complex Communication Needs and Autism Spectrum DisorderDocument17 pagesPromoting Peer Interaction For Preschool Children With Complex Communication Needs and Autism Spectrum Disorderm amirNo ratings yet

- Lessons For Teaching Social and Emotional CompetenceDocument9 pagesLessons For Teaching Social and Emotional CompetenceAdomnicăi AlinaNo ratings yet

- ED619622Document31 pagesED619622John RambooNo ratings yet

- Social Stories, Written Text Cues, and Video Feedback: Effects On Social Communication of Children With AutismDocument22 pagesSocial Stories, Written Text Cues, and Video Feedback: Effects On Social Communication of Children With AutismMaria Elisa Granchi FonsecaNo ratings yet

- Classroom Peer Relationships and Behavioral Engagement..Document13 pagesClassroom Peer Relationships and Behavioral Engagement..reniNo ratings yet

- Promoting The Social and Communicative Behavior of Young Children With Autism Spectrum DisordersDocument16 pagesPromoting The Social and Communicative Behavior of Young Children With Autism Spectrum DisordersHaziq AlfatehNo ratings yet

- Bower 2015Document15 pagesBower 2015Anonymous 7YP3VYNo ratings yet

- Review of Naturalistic Interventions for Prelinguistic Communication in Children with AutismDocument17 pagesReview of Naturalistic Interventions for Prelinguistic Communication in Children with AutismLaura BeatrizNo ratings yet

- A Meta-Analytic Review of Social, Self-Concept, and Behavioral Outcomes of Peer-Assisted LearningDocument18 pagesA Meta-Analytic Review of Social, Self-Concept, and Behavioral Outcomes of Peer-Assisted LearningShahid KhanNo ratings yet

- LCCS I 002 FTDocument6 pagesLCCS I 002 FTMettia100% (1)

- Son Rise PDFDocument12 pagesSon Rise PDFMaximMadalinaIulianaNo ratings yet

- The School As Social Context: Social Interaction Patterns of Children With Physical DisabilitiesDocument9 pagesThe School As Social Context: Social Interaction Patterns of Children With Physical DisabilitiesGeorgiana OghinciucNo ratings yet

- Mcgee 1992Document10 pagesMcgee 1992Ana VillaresNo ratings yet

- 4 - Scoping Review - Gibson 2021Document30 pages4 - Scoping Review - Gibson 2021KATERINE OCAMPO RIOSNo ratings yet

- Social Story Effectiveness On Social Interaction For Students With Autism - A Review of The Literature (2018)Document16 pagesSocial Story Effectiveness On Social Interaction For Students With Autism - A Review of The Literature (2018)SarahNo ratings yet

- Teaching Children With Autism To Initiate and Respond To Peer Mands Using Picture Exchange Communication SystemDocument10 pagesTeaching Children With Autism To Initiate and Respond To Peer Mands Using Picture Exchange Communication SystemGrethell UrcielNo ratings yet

- Kasey Cook Assessment One Literature ReviewDocument8 pagesKasey Cook Assessment One Literature ReviewKelly FrazerNo ratings yet

- Week 5 Ebp For Communication Social Behavior Skills 1Document6 pagesWeek 5 Ebp For Communication Social Behavior Skills 1api-609548053No ratings yet

- Social_Integration_of_Students_with_Autism_in_InclDocument11 pagesSocial_Integration_of_Students_with_Autism_in_Incldemi.wilkie17No ratings yet

- Brief Report Predictors of Outcomes in The Early Start Denver Model Delivered in A Group SettingDocument8 pagesBrief Report Predictors of Outcomes in The Early Start Denver Model Delivered in A Group SettingLuis SeixasNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 1 DinzDocument10 pagesCHAPTER 1 DinzDinz Guanzon TayactacNo ratings yet

- Assist Parents To Facilitate Social Skills in Young Children With Disabilities Through PlayDocument11 pagesAssist Parents To Facilitate Social Skills in Young Children With Disabilities Through PlayLandoi VuittonNo ratings yet

- Research Supporting DIRDocument6 pagesResearch Supporting DIRsegurryNo ratings yet

- The Use of Group Therapy As A Means of Facilitating Cognitive-Behavioural Instruction For Adolescents With Disruptive BehaviourDocument17 pagesThe Use of Group Therapy As A Means of Facilitating Cognitive-Behavioural Instruction For Adolescents With Disruptive BehaviourNourhanNo ratings yet

- ERIC2Document10 pagesERIC2Fanni SzemereNo ratings yet

- Peer-mediated social skills program improves communication in children with autismDocument14 pagesPeer-mediated social skills program improves communication in children with autismPsicoterapia InfantilNo ratings yet

- Autism Partnership Foundation Comparing Social Stories To Cool Versus Not CoolDocument14 pagesAutism Partnership Foundation Comparing Social Stories To Cool Versus Not CoolSteven TanNo ratings yet

- Conroy Asmus Sellers Ladwig2005Document10 pagesConroy Asmus Sellers Ladwig2005suwillowNo ratings yet

- Evidence Base For The DIR2-2011D CullinaneDocument11 pagesEvidence Base For The DIR2-2011D CullinanecirclestretchNo ratings yet

- Social Competence and Social Skills Training and Intervention For Children With Autism Spectrum DisordersDocument11 pagesSocial Competence and Social Skills Training and Intervention For Children With Autism Spectrum DisordersbmwardNo ratings yet

- Level of Pro-Social Behavior Impacts Verbal CommunicationDocument29 pagesLevel of Pro-Social Behavior Impacts Verbal CommunicationYvonne YuntingNo ratings yet

- Tse2007 Article SocialSkillsTrainingForAdolescDocument9 pagesTse2007 Article SocialSkillsTrainingForAdolescGabriel BrantNo ratings yet

- Video modeling teaches complex social sequences to children with autismDocument16 pagesVideo modeling teaches complex social sequences to children with autismAlexandra DragomirNo ratings yet

- Promoting Childrens and Adolescents Social and Emotional DevelopmentDocument16 pagesPromoting Childrens and Adolescents Social and Emotional DevelopmentViviana MuñozNo ratings yet

- Developmental Social Pragmatic Interventions For Preschoolers With Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic ReviewDocument18 pagesDevelopmental Social Pragmatic Interventions For Preschoolers With Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic ReviewFrida PandoNo ratings yet

- Incorporating: Thematic Ritualistic Behaviors Children With Autism IntoDocument19 pagesIncorporating: Thematic Ritualistic Behaviors Children With Autism IntoAnonymous 75M6uB3OwNo ratings yet

- Tennessee Technological UniversityDocument11 pagesTennessee Technological UniversityNurjannah ZainalNo ratings yet

- Effects of an Inclusion Professional Development Model on Inclusion Knowledge and Perceptions of Regular Middle School EducatorsFrom EverandEffects of an Inclusion Professional Development Model on Inclusion Knowledge and Perceptions of Regular Middle School EducatorsNo ratings yet

- OptometristDramaticPlay 1Document9 pagesOptometristDramaticPlay 1Gloria AGNo ratings yet

- Grammar1 FutureDocument2 pagesGrammar1 FutureLauren DavisNo ratings yet

- Sentences and Choose The Correct Form of The VerbDocument1 pageSentences and Choose The Correct Form of The VerbGloria AGNo ratings yet

- Past Simple-Exercises-For-RevisionDocument1 pagePast Simple-Exercises-For-RevisionMilica Petrović100% (1)

- RestaurantDramaticPlayMenuFreebie 1Document6 pagesRestaurantDramaticPlayMenuFreebie 1Gloria AGNo ratings yet

- OptometristDramaticPlay 1Document9 pagesOptometristDramaticPlay 1Gloria AGNo ratings yet

- Rephrasings of Modal VerbsDocument1 pageRephrasings of Modal VerbsGloria AGNo ratings yet

- Preliminary English Test: Writing Part 1Document1 pagePreliminary English Test: Writing Part 1Gloria AGNo ratings yet

- Peer Training To Facilitate Social Interaction ForDocument16 pagesPeer Training To Facilitate Social Interaction ForGloria AGNo ratings yet

- The Causative - To Have Something DoneDocument1 pageThe Causative - To Have Something DoneGloria AGNo ratings yet

- The Passive: Mixed Tenses: Change These Sentences From Active To PassiveDocument1 pageThe Passive: Mixed Tenses: Change These Sentences From Active To PassiveGloria AGNo ratings yet

- Has mighty Everest been reduced to a playgroundDocument2 pagesHas mighty Everest been reduced to a playgroundGloria AGNo ratings yet

- Selectividad Junio 2017 Madrid Inglés Opción A ExamenDocument2 pagesSelectividad Junio 2017 Madrid Inglés Opción A ExamenGloria AGNo ratings yet

- Pasivas BachilleratoDocument3 pagesPasivas BachilleratoGloria AGNo ratings yet

- Christmas: Creative Thinking TasksDocument8 pagesChristmas: Creative Thinking TasksGloria AGNo ratings yet

- Grammar PastSimple3 18844 PDFDocument2 pagesGrammar PastSimple3 18844 PDFminoro2583No ratings yet

- PET Writing Part 1 Transformation Exercises PDFDocument7 pagesPET Writing Part 1 Transformation Exercises PDFJavier TiradoNo ratings yet

- Just, Already or Yet? Learn the differencesDocument1 pageJust, Already or Yet? Learn the differencesDennis Villalobos Alegre0% (1)

- Monkey Puzzle Crossword AnimalsDocument2 pagesMonkey Puzzle Crossword AnimalsGloria AGNo ratings yet

- Examen Ingles Selectividad Junio 2017 SolucionDocument5 pagesExamen Ingles Selectividad Junio 2017 SolucionMontserrat Sanchez CarrascosaNo ratings yet

- Grammar-PresentSimplePresentCont 2663 PDFDocument2 pagesGrammar-PresentSimplePresentCont 2663 PDFMari Cruz Vega RojoNo ratings yet

- CONDITIONAL and WISH Rephrasing and KeyDocument3 pagesCONDITIONAL and WISH Rephrasing and KeyAlbaVozmedianoRodillaNo ratings yet

- Grammar PresentSimple2 18854Document2 pagesGrammar PresentSimple2 18854MaamCRNo ratings yet

- StoryCubeTales6Cubes 1Document1 pageStoryCubeTales6Cubes 1Gloria AGNo ratings yet

- Grammar PastSimplePastContinuous1 18845Document2 pagesGrammar PastSimplePastContinuous1 18845Lourdes GLNo ratings yet

- Grammar PastSimple3 18844Document2 pagesGrammar PastSimple3 18844minoro2583No ratings yet

- Grammar PresentPerfect2 2esoDocument2 pagesGrammar PresentPerfect2 2esoDomingoNo ratings yet

- Parts of The Body AnimalsDocument1 pageParts of The Body AnimalsGloria AGNo ratings yet

- 21 ST Century Skill "Problem Solving": Defining The Concept: April 2019Document12 pages21 ST Century Skill "Problem Solving": Defining The Concept: April 2019Ashley JoyceNo ratings yet

- Chapter Three: Theoretical Overview of TraumaDocument25 pagesChapter Three: Theoretical Overview of TraumaSahrish AliNo ratings yet

- Department of Education: Epublic of The PhilippineDocument2 pagesDepartment of Education: Epublic of The PhilippineChriztine Marie AsinjoNo ratings yet

- Components of A Lesson PlanDocument43 pagesComponents of A Lesson PlanMyrnaArlandoNo ratings yet

- The Social BrainDocument8 pagesThe Social BrainZeljko LekovicNo ratings yet

- References: Prepared By: Sherry Lene S. GonzagaDocument3 pagesReferences: Prepared By: Sherry Lene S. GonzagaSherry GonzagaNo ratings yet

- Persuasion TechniquesDocument42 pagesPersuasion Techniquesvindaloo2967No ratings yet

- Grade 8 DLL PE Quarter 1Document3 pagesGrade 8 DLL PE Quarter 1Gil Anne Marie TamayoNo ratings yet

- Module 3.1.Understanding&Motivating - StudentsDocument40 pagesModule 3.1.Understanding&Motivating - StudentsHo Nguyen Phuoc DuyenNo ratings yet

- Stage 1 Stage 2 Stage 3Document3 pagesStage 1 Stage 2 Stage 3Matt Julius CorpuzNo ratings yet

- The Enduring Principles of LearningDocument1 pageThe Enduring Principles of LearningSharmaneJosephNo ratings yet

- Organizational BehaviorDocument65 pagesOrganizational BehaviorphanhoangthihienNo ratings yet

- Understanding Behavioural CommunicationDocument8 pagesUnderstanding Behavioural Communicationjitendra7779858No ratings yet

- Teachers' Pedagogical Systems and Grammar Teaching: A Qualitative StudyDocument30 pagesTeachers' Pedagogical Systems and Grammar Teaching: A Qualitative StudyMehmet Emin MadranNo ratings yet

- Easy 4-step guide to summarize essaysDocument3 pagesEasy 4-step guide to summarize essaysGunjan PNo ratings yet

- Attention and Consciousness Chapter OutlineDocument32 pagesAttention and Consciousness Chapter OutlineJainne Ann BetchaidaNo ratings yet

- Self-Reflection: Forum: Retreat Exercise GuideDocument14 pagesSelf-Reflection: Forum: Retreat Exercise GuideRavi ShahNo ratings yet

- Lexical Chunks ExplanationDocument2 pagesLexical Chunks ExplanationVeronica OguilveNo ratings yet

- Culture': Shared Basic Assumptions Solved Its Problems Passed On Perceive, Think, and FeelDocument25 pagesCulture': Shared Basic Assumptions Solved Its Problems Passed On Perceive, Think, and FeelRumaNo ratings yet

- Jennifer Fukuwa - ResumeDocument2 pagesJennifer Fukuwa - Resumeapi-610881907No ratings yet

- Step 2. The Nature of Linguistics and Language PDFDocument7 pagesStep 2. The Nature of Linguistics and Language PDFYenifer Quiroga HerreraNo ratings yet

- Overview of Social Sciences FinalDocument19 pagesOverview of Social Sciences FinalDhaf DadullaNo ratings yet

- BSBLDR501 Short Answer Questions File 2 CompleteDocument5 pagesBSBLDR501 Short Answer Questions File 2 CompleteJackson KasakuNo ratings yet

- Marissa J Corbett ResumeDocument2 pagesMarissa J Corbett Resumeapi-428448687No ratings yet

- Organization BehaviorDocument7 pagesOrganization Behaviorbefox87318No ratings yet

- Teaching AssessmentDocument26 pagesTeaching AssessmentLance DomingoNo ratings yet

- Contoh LESSON NOTEDocument1 pageContoh LESSON NOTEFae Ra Lee-DeaNo ratings yet

- Data Science Interview Questions (#Day27)Document18 pagesData Science Interview Questions (#Day27)ARPAN MAITYNo ratings yet

- Unleashing The Power of Compassionate LeadershipDocument33 pagesUnleashing The Power of Compassionate LeadershipRamanathan MNo ratings yet